Abstract

Cypripedium macranthos Swartz, C. × ventricosum Swartz, and C. shanxiense S. C. Chen were highly promising ornamental plants. In this study, the latest complete chloroplast genome sequence of C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense were reported using correct sample material from their native range, and their phylogenetic relationships with other related species were investigated preliminarily. The whole chloroplast genome lengths of C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense were 181,030 bp, 175,385 bp, and 177,627 bp, respectively, with total GC contents of 34.56%, 34.48%, and 34.42%, respectively. Based on the maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree from the chloroplast genome sequences and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences, it was confirmed that C. × ventricosum is most closely related to C. calceolus, and the idea that C. × ventricosum is an interspecific hybrid between C. calceolus and C. macranthos is supported. By integrating the results of phylogenetic analysis, genomic structural comparison, and considerations of sampling locations, it is evident that the former chloroplast genome of C. macranthos is inaccurate. This study provides crucial information for research on the phylogeny, genetics, and conservation of C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The genus Cypripedium, a subdivision within the Orchidaceae family, is renowned for its species that feature a labellum evolved into a slipper-like structure, commonly known as slipper orchids or lady’s slippers1,2. Cypripedium macranthos Swartz (1800) (Fig. 1a) and C. × ventricosum Swartz (1800) (Fig. 1b) are two such species that thrive in cooler climates and are not tolerant of high temperatures. They are among the few orchids that inhabit temperate, high-latitude regions and have a global distribution limited to Russia, China, Japan, and the Korean Peninsula2,3,4,5. Their distinctive petal shapes and vivid bloom colors endow C. macranthos and C. × ventricosum with significant ornamental value, ranking them among the most favored orchids4. C. shanxiense S. C. Chen (1983) (Fig. 1c) is mainly found in northern and western China, northern Japan, southeastern Russia, and across Mongolia5,6. Distinct from most Cypripedium species, C. shanxiense boasts small, delicate flowers with unique colors that are neither purely greenish-yellow nor yellow, nor bright crimson or purplish-red, yet it retains a high ornamental value and shows promise for garden landscape applications.

Successful hybridization between genera and species of Orchidaceae plants often exists6. C. × ventricosum often grows in association with C. calceolus and C. macranthos, and it is therefore considered to be a natural hybrid of these two species5,6,7. However, there is still insufficient molecular evidence to confirm their relationship. In the past decade, habitat loss, biological factors (such as regeneration challenges) and over-collection of these beautiful wildflowers for horticultural and medicinal purposes have brought these wild species dangerously close to extinction3,4,8. To date, few studies have been conducted on these beautiful and endangered orchids.

The chloroplast genome is a valuable source of information for studying plant phylogeny and evolution, which is attributed to its predominantly maternal inheritance9,10,11,12. With the advancement of sequencing technologies, an increasing number of plant chloroplast genomes are being discovered, which contributes to our understanding of plant phylogeny13,14. While Luo et al. have published the chloroplast genome of C. macranthos, the sample collection site in Yunnan, China, characterized by a tropical or subtropical monsoon climate, does not align with the cool-temperate habitat preferences of C. macranthos15. Consequently, we have sampled from the native distributions of C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense, and in this paper, we report the most up-to-date chloroplast genomes for these species, along with phylogenetic analyses. Our findings are poised to contribute valuable insights for future research, development, and application related to C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense.

Reference image of C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense flowering plant. (a) Reference image of C. macranthos; (b) Reference image of C. × ventricosum; (c) Reference image of C. shanxiense. All of the above images were taken by Mr. Baoqiang Zheng. Images a and b were photographed in Sandawan Township, Yanji County, Jilin Province, China (43.2°N, 129.1°E), and image c was taken in the Beijing Songshan Nature Reserve (40.3°N, 115.4°E). All images are unpublished (used with permission).

Results

Assembly and annotation of the Chloroplast genome

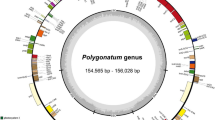

The entire chloroplast genome of C. macranthos was a circular molecule composed of 181,030 bp, comprising four contiguous segments: a large single-copy region (LSC) of 103,242 bp, a short single-copy region (SSC) of 22,268 bp, and two inverted repeat regions (IRA and IRB) of 27,760 bp each, with a total GC content of 34.56% (Fig. 2). The average sequencing depth was 543 × (Figure S7). The genome contained 131 genes, including 85 protein-coding genes, 38 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, and 8 ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes. Among these, 8 protein-coding genes (atpF, rpoC1, petB, petD, rpl16, rpl2, ndhB, ndhA) and 6 tRNA genes (trnK-UUU, trnG-UCC, trnL-UAA, trnV-UAC, trnI-GAU, trnA-UGC) contained one intron, 2 protein-coding genes (ycf3, clpP) contained two introns (Figure S1), and 1 gene contained a trans-splicing gene (rps12) (Figure S2).

Chloroplast genome map of C. macranthos. Genes belonging to different functional groups are shown in different colors. Genes within the circle undergo clockwise transcription, while those outside the circle undergo counterclockwise transcription. The functional classification of the genes is shown in the bottom left corner. The light green inner circle indicates the GC content of the chloroplast genome.

The chloroplast genome of C. × ventricosum was a circular molecule totaling 175,385 bp, with a GC content of 34.48%. It consisted of four contiguous segments: two inverted repeat regions (IRA and IRB) of 27,760 bp each, a large single-copy region (LSC) of 97,520 bp, and a short single-copy region (SSC) of 22,345 bp (Fig. 3). The average sequencing depth was 282 × (Figure S8). The genome contained a total of 131 genes, including 85 protein-coding genes, 38 tRNA genes, and 8 rRNA genes. Among these, 8 protein-coding genes (atpF, rpoC1, petB, petD, rpl16, rpl2, ndhB, ndhA) and 6 tRNA genes (trnK-UUU, trnG-UCC, trnL-UAA, trnV-UAC, trnI-GAU, trnA-UGC) contained one intron, 2 protein-coding genes (ycf3, clpP) contained two introns (Figure S3), and 1 gene contained a trans-spliced gene (rps12) (Figure S4).

Chloroplast genome map of C. × ventricosum. Genes belonging to different functional groups are shown in different colors. Genes within the circle undergo clockwise transcription, while those outside the circle undergo counterclockwise transcription. The functional classification of the genes is shown in the bottom left corner. The light green inner circle indicates the GC content of the chloroplast genome.

The chloroplast genome of C. shanxiense was a circular molecule of 177,627 bp, composed of four continuous segments: two inverted repeat regions (IRA and IRB), each 27,691 bp; a large single-copy region (LSC), 99,779 bp; and a short single-copy region (SSC), 22,466 bp, with a total GC content of 34.42% (Fig. 4). The average sequence depth was 420 × (Figure S9). A total of 133 genes were identified, including 87 protein-coding genes, 38 tRNA genes, and 8 rRNA genes. Among these, 9 protein-coding genes (rps16, atpF, rpoC1, petB, petD, rpl16, rpl2, ndhB, ndhA) and 6 tRNA genes (trnK-UUU, trnG-UCC, trnL-UAA, trnV-UAC, trnI-GAU, trnA-UGC) contained one intron, 2 protein-coding genes (ycf3, clpP) contained two introns (Figure S5), and 1 gene (rps12) contained a trans-spliced intron (Figure S6).

Chloroplast genome map of C. shanxiense. Genes belonging to different functional groups are shown in different colors. Genes within the circle undergo clockwise transcription, while those outside the circle undergo counterclockwise transcription. The functional classification of the genes is shown in the bottom left corner. The light green inner circle indicates the GC content of the chloroplast genome.

Phylogenetic analysis

A phylogenetic tree can be represented by a branching diagram that illustrates the relationships between similar organisms in a tree-like structure16. The chloroplast genome sequences of 34 Lythraceae species and 3 Amaryllidaceae species were selected from NCBI to investigate the phylogeny of C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense (Fig. 5a). According to the phylogenetic tree, species from the same genus were grouped together in one branch, while species from different genera diverged. Each node had excellent support (BS ≥ 95.6). However, the former C. macranthos (submitted by Luo et al.15) was not placed in the same branch as the other Cypripedium species. The latest chloroplast genome of C. macranthos (submitted by us) was most closely related to C. calceolus and C. × ventricosum, and C. × ventricosum was positioned between the branches of C. calceolus and C. macranthos.

To further assess the relationship between C. × ventricosum and C. macranthos as well as C. calceolus, a phylogenetic analysis was conducted on the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences of 31 Cypripedium species and 2 Paphiopedilum species. Based on the branching pattern of the tree, C. × ventricosum was most closely related to C. calceolus, and it is positioned between the branches of C. calculous and C. macranthos, which also suggests that it might be a hybrid descendant of these two species (Fig. 5b).

Chloroplast genome and ITS phylogenetic trees. ML tree based on the whole chloroplast genome of C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, C. shanxiense, and 34 Orchidaceae species, with 3 Amaryllidaceae species as outgroups (a). ML tree based on ITS sequences from 31 Cypripedium species, with 2 Paphiopedilum species as outgroups (b). The numbers at each node represent the bootstrap values from 1000 repetitions. “*” indicates that the bootstrap value is below 70. On the left side of each tree, a ML tree that preserves genetic distances is displayed, with branch colors corresponding to the genus-specific background colors indicated in the figure on the right.

Genome structure analysis

Based on the chloroplast genome sequence alignment results, it can be observed that the latest C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense exhibit high conservation, with variations in the non-coding regions being higher than those in the coding regions. Most of the high mutation areas are also located within the conserved non-coding sequences (CNS). In contrast, the former C. macranthos also exhibits significant variation in the exon regions (Fig. 6a). The comparison of the IR boundaries among C. calceolus, the former C. macranthos, the latest C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense reveals that C. calceolus, the latest C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense are relatively conservative at the IR boundaries. The main difference of the former C. macranthos from the other four is the absence of ycf1 at the IRb-SSC boundary, and ndhF does not span the SSC-IRb boundary (Fig. 6b). Based on the collinearity analysis of the chloroplast genomes, it was found that C. calceolus, the former C. macranthos, the latest C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense did not undergo rearrangements or inversions (Fig. 6c).

Comparison of chloroplast genome structures in five Cypripedium species. Visualization of chloroplast genome sequence alignment for four Cypripedium species using C. calceolus as a reference (a). The vertical scale shows the percent of identity, ranging from 50 to 100%. The horizontal axis shows the coordinates within the chloroplast genome. Comparison of the LSC, SSC, and IR boundaries among five Cypripedium chloroplast genomes (b). The LSC, SSC, and IR regions are shown in different colors. JLB, JSB, JSA, and JLA represent the junction sites between the corresponding regions of the genome, respectively. Genes are depicted as boxes. Collinearity analysis of the chloroplast genomes from five Cypripedium species (c).

Discussion

Chloroplast genomics is a research hotspot for the study of plant evolutionary relationships because the plant chloroplast genome has a comparatively stable and conservative structure and includes extensive genetic information, which is an important basis for the study of plant evolutionary relationships17,18. In this study, the latest complete chloroplast genome of C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense were assembled and phylogenetically analyzed with the published chloroplast genomes of 34 species of Orchidaceae and 3 of Amaryllidaceae. The phylogenetic analysis revealed that distinct genera diverged from one another and that species belonging to the same genus were clustered into a single branch, indicating the presence of distinct boundaries between various genera. Interestingly, species of Cypripedium can be clearly distinguished into two groups within a single branch, suggesting a clear differentiation event in Cypripedium.

Previously, Li et al. cloned six genes and conducted a phylogenetic analysis of the Cypripedium genus, which did not include C. × ventricosum, but found that C. calceolus is most closely related to C. shanxiense, rather than C. macranthos19. In contrast, the phylogenetic analysis of the entire chloroplast genome in this study indicates a close relationship between C. × ventricosum and both C. calceolus and C. macranthos, with C. × ventricosum positioned between the branches of C. calceolus and C. macranthos. Meanwhile, C. shanxiense is most closely related to C. henryi. In addition, this study conducted a phylogenetic analysis based on the known ITS sequences of 31 Cypripedium species, and the results indicate that C. × ventricosum is most closely related to C. calceolus, and it is also positioned between the branches of C. calceolus and C. macranthos. These results indicate that the findings of this study support the view proposed by earlier scholars that C. × ventricosum is an inter-specific hybrid between C. calceolus and C. macranthos5,6,7. Additionally, the former C. macranthos did not cluster with other Cypripedium species in the same branch. Through structural comparative analysis of the genome, we found that the former C. macranthos chloroplast genome did not undergo rearrangements or inversions within the genome. This may suggest that the material from Luo et al. was not a pure strain of C. macranthos15. Given the natural hybridization of Orchidaceae species and the sampling location of Luo et al., it is speculated that this is likely a hybrid species that was mistakenly identified as C. macranthos due to its striking similarity to C. macranthos6,15.

In conclusion, this study supports the idea that C. × ventricosum is an interspecific hybrid between C. calceolus and C. macranthos from a molecular biology perspective. The reliable complete chloroplast genome of C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense in this study will provide important theoretical support for the accurate and rapid identification of C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense species, the scientific delineation of relatives, and the mechanism of genetic evolution, and will also be of great significance to the cultivation of high-quality germplasm resources and the conservation of wild resources of C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Fresh leaves of C. macranthos and C. × ventricosum were collected from Sandaowan Town, Yanji County, Jilin Province, China (43.2°N; 129.1°E), and fresh leaves of C. shanxiense were collected from Songshan Nature Reserve, Beijing, China (40.3°N, 115.4°E). The specimens of C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense were stored in the flower herbarium of the Research Institute of Forestry, Chinese Academy of Forestry, and can be accessed through the contact person Baoqiang Zheng (zhengbaoqiang@aliyun.com) under the registration number CM0008, CV0004 and CS0014, respectively.

Genome sequencing, assembly, and annotation

Using the Fast Plant Genomic DNA Isolation Kit (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), total DNA was recovered. Hieff NGS®MaxUp II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (YEASEN, Shanghai, China) was used for sequencing library construction. The Illumina Novaseq 6000 sequencing platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA) was used to generate paired-ended raw reads.

Fastp v0.36 was used as a tool for quality control of the sequencing data20. Sequencing depth and coverage were calculated using BEDTools v2.31.1 and mapping was performed using R-ggplot221. Bowtie2 v2.1.0 was used to splice the sequenced segments22. The chloroplast genome was assembled using GetOrganelle v1.7.5.3 with C. calceolus (NC045400) as a reference23,24.

CPGAVAS2 (http://47.96.249.172:16019/analyzer/home) was used to annotate the chloroplast genome25. tRNAs were identified using tRNAscan-SE v2.026. BLAST and DOGMA (http://dogma.ccbb.utexas.edu/) were used to verify the annotations27,28. The annotation of the chloroplast genome of C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense were uploaded to GenBank (accession number: PP356909, PP448181, PP503063).

Circos (http://circos.ca/) was used to map circular genes29. CPGview (http://www.1kmpg.cn/cpgview/) was used to map cis- and trans-splicing genes30.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic trees were constructed using chloroplast genome sequences and ITS sequences, respectively. Sequence alignment was performed using MAFFT v7 (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/)31. The Gblocks module in PhyloSuite v1.2.2 was used for trimming, and the ModelFinder module was used to determine the best models for the chloroplast genome sequence phylogenetic tree and the ITS sequence phylogenetic tree, which were GTR + F + R4 and SYM + G4, respectively. The IQ-TREE module was used to perform maximum likelihood (ML) analysis32. The phylogenetic tree was visualized using iTOL v6 (https://itol.embl.de/)33. The chloroplast genome sequences and ITS sequences used for phylogenetic analysis were detailed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Comparative analysis of genome structure

Using C. calceolus (NC045400) as the reference genome, a visual comparison of the chloroplast genomes of the former C. macranthos (KF925434), the latest C. macranthos (PP356909), C. × ventricosum (PP448181), and C. shanxiense (PP503063) was conducted with mVISTA (https://genome.lbl.gov/vista/index.shtml), selecting the Shuffle-LAGAN mode55.

Using CPJSdraw (V1.0.0) to generate a visual map of the IR boundaries for the chloroplast genomes of C. calceolus (NC045400), the former C. macranthos (KF925434), the latest C. macranthos (PP356909), C. × ventricosum (PP448181), and C. shanxiense (PP503063)56.

Conducting a collinear analysis of the chloroplast genomes of C. calceolus (NC045400), the former C. macranthos (KF925434), the latest C. macranthos (PP356909), C. × ventricosum (PP448181), and C. shanxiense (PP503063) using Mauve (https://darlinglab.org/mauve/mauve.html).

Data availability

The NCBI database in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) has the C. macranthos, C. × ventricosum, and C. shanxiense genome sequence data supporting the findings of this study available to the public under the accession number PP356909, PP448181, and PP503063, respectively. The associated BioProject, BioSample and Sequence Read Archive numbers with C. macranthos are PRJNA1078557, SAMN40005752 and SRR28025806, respectively. The associated BioProject, BioSample and Sequence Read Archive numbers with C. × ventricosum are PRJNA1084227, SAMN40275977 and SRR28236982, respectively. The associated BioProject, BioSample and Sequence Read Archive numbers with C. shanxiense are PRJNA1088625, SAMN40479335, and SRR28362302, respectively.

References

Frosch, W. et al. Hardy Cypripedium: Species, Hybrids and Cultivation. (kew Publishing, 2012).

Sugiura, N. et al. Comparative pollination biology in two sympatric varieties of Cypripedium Macranthos (Orchidaceae) on Rebun Island, Hokkaido, Japan. Plant. Species. Biol. 30, 225–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/1442-1984.12055 (2014).

Chung, J. M. et al. Contrasting levels of genetic diversity between the historically rare Orchid Cypripedium Japonicum and the historically common Orchid Cypripedium Macranthos in South Korea. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 160, 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00965.x (2010).

Wu, Q. et al. Genetic diversity, population genetic structure and gene flow in the rare and endangered wild plant Cypripedium Macranthos revealed by genotyping-by-sequencing. BMC Plant Biol. 23, 254. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-023-04212-z (2023).

Chen, X. Q. et al. Flora of China: Orchidaceae. Vol. 25 (Science, 2009).

Chen, X. Q. et al. The Genus Cypripedium in China. (Science, 2013).

Efimov, P. G. et al. Remnant populations of Cypripedium Macranthos (Orchidaceae) in Eastern Europe: evidence of almost complete extinction and widespread introgression with Cypripedium calceolus. Nat. Conserv. Res. 7, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.24189/ncr.2022.014 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Asymbiotic germination of immature seeds and the seedling development of Cypripedium Macranthos Sw., an endangered Lady’s slipper Orchid. Sci. Hort. 164, 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2013.08.006 (2013).

Shen, J. S. et al. The complete Chloroplast genome sequence of Rhododendron Farrerae Tate ex sweet (Ericaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 9, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2023.2294897 (2024).

Daniell, H. et al. Chloroplast genomes: diversity, evolution, and applications in genetic engineering. Genome Biol. 17, 134. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-1004-2 (2016).

Daniell, H. et al. Green giant-a tiny Chloroplast genome with mighty power to produce high-value proteins: history and phylogeny. Plant Biotechnol. J. 19, 430–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13556 (2021).

Yang, T. et al. Chloroplast genomes and phylogenetic analysis of three Carthamus (Asteraceae) species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 15634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242115634 (2023).

Yang, J. B. et al. Highly effective sequencing whole Chloroplast genomes of angiosperms by nine novel universal primer pairs. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 14, 1024–1031. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12251 (2014).

Shi, C. et al. An improved Chloroplast DNA extraction procedure for whole plastid genome sequencing. Plos One. 7, e31468. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031468 (2012).

Luo, J. et al. Comparative Chloroplast genomes of photosynthetic orchids: insights into evolution of the Orchidaceae and development of molecular markers for phylogenetic applications. Plos One. 9, e99016. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0099016 (2014).

Bian, C. et al. The complete Chloroplast genome of Pulsatilla chinensis F. alba D. K. Zang (Ranunculaceae, Pulsatilla Miller). Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 9, 233–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2023.2294894 (2024).

Xiong, A. S. et al. Gene duplication, transfer, and evolution in the Chloroplast genome. Biotechnol. Adv. 27, 340–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.01.012 (2009).

Olejniczak, S. A. et al. Chloroplasts: state of research and practical applications of plastome sequencing. Planta 244, 517–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-016-2551-1 (2016).

Li, J. H. et al. Molecular phylogeny of Cypripedium (Orchidaceae: Cypripedioideae) inferred from multiple nuclear and Chloroplast regions. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 61, 308–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2011.06.006 (2011).

Chen, S. F. et al. Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560 (2018).

Quinlan, A. R. et al. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033 (2010).

Langmead, B. et al. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 9, 357–359. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1923 (2012).

Zhang, L. J. et al. The complete Chloroplast genome sequence of the threatened Cypripedium calceolus (Orchidaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 4, 4220–4222. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2019.1693933 (2019).

Jin, J. J. et al. GetOrganelle: a fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de Novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 21, 241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-02154-5 (2019).

Shi, L. C. et al. CPGAVAS2, an integrated plastome sequence annotator and analyzer. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W65–W73. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz345 (2019).

Chan, P. P. et al. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 9077–9096. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab688 (2021).

Wyman, S. K. et al. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics 20, 3252–3255. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352 (2004).

Benson, D. A. et al. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D36–D42. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1195 (2013).

Krzywinski, M. et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19, 1639–1645. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.092759.109 (2009).

Liu, S. Y. et al. CPGView: a package for visualizing detailed Chloroplast genome structures. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 23, 694–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13729 (2023).

Katoh, K. et al. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Brief. Bioinform. 30, 772–780. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst010 (2013).

Zhang, D. et al. PhyloSuite: an integrated and scalable desktop platform for streamlined molecular sequence data management and evolutionary phylogenetics studies. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 20, 348–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13096 (2020).

Letunic, I. et al. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W293–W296. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab301 (2021).

Xue, Q. Q. et al. The climate changes promoted the Chloroplast genomic evolution of Dendrobium orchids among multiple photosynthetic pathways. BMC Plant Biol. 23, 189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-023-04186-y (2023).

Kim, Y. K. et al. Plastome evolution and phylogeny of orchidaceae, with 24 new sequences. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00022 (2020).

Yang, Y. B. et al. The complete Chloroplast genome of Dendrobium moschatum (Buch.-Ham.) Sw. 1805 (Orchidaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 7, 2027–2030. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2022.2149249 (2022).

Zhu, B. et al. The complete Chloroplast genome sequence of Dendrobium thyrsiflorum (Orchidaceae) and its phylogenetic analysis. Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 4, 4085–4086. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2019.1691947 (2019).

Shao, L. et al. The complete Chloroplast genome of Cymbidium serratum (Orchidaceae): a rare and endangered species endemic to Southwest China. Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 5, 2429–2431. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2020.1775514 (2020).

Du, Z. H. et al. The complete Chloroplast genome of Cymbidium Dayanum (Orchidaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 6, 1897–1898. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2021.1934173 (2021).

Li, J. F. et al. The complete Chloroplast genome sequence of Cypripedium Tibeticum King ex Rolfe (Orchidaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 5, 150–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2019.1698357 (2019).

Guo, Y. Y. et al. Chloroplast genomes of two species of Cypripedium: expanded genome size and proliferation of AT-biased repeat sequences. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 609729. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.609729 (2021).

Yang, J. B. et al. Complete Chloroplast genome of the genus Cymbidium: lights into the species identification, phylogenetic implications and population genetic analyses. BMC Evol. Biol. 13, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-13-84 (2013).

Zhang, J. Y. et al. Comparative Chloroplast genomics of seven endangered Cypripedium species and phylogenetic relationships of Orchidaceae. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 911702. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.911702 (2022).

Wang, X. T. et al. The complete Chloroplast genome of an ornamental Orchid, Vanda coerulescens (Orchidaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 5, 465–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2019.1704195 (2020).

Kim, J. S. et al. The largest plastid genome of monocots: a novel genome type containing AT residue repeats in the slipper Orchid Cypripedium Japonicum. Plant. Mol. Biology Report. 33, 1210–1220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11105-014-0833-y (2015).

Liu, D. K. et al. The complete plastid genome of Vanda subconcolor (Orchidaceae, Aeridinae). Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 5, 1712–1713. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2020.1749169 (2020).

Lin, C. S. et al. The location and translocation of Ndh genes of Chloroplast origin in the Orchidaceae family. Sci. Rep. 5, 9040. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09040 (2015).

Chen, J. L. et al. Complete plastid genome of Vanda concolor (Orchidaceae, Aeridinae). Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 4, 3687–3688. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2019.1679049 (2019).

Li, Z. H. et al. Evolution of plastid genomes of Holcoglossum (Orchidaceae) with recent radiation. BMC Evol. Biol. 19, 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-019-1384-5 (2019).

Jiang, M. et al. Complete Chloroplast genome of a rare and endangered plant species Phalaenopsis zhejiangensis: genomic features and phylogenetic relationship within Orchidaceae. Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 6, 2872–2879. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2021.1972049 (2021).

Liu, K. et al. Comparative genomics and phylogenetic perspectives of six fertile Lycoris species endemic to East Asia based on plastome characterization. Nord. J. Bot. 2022, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/njb.03412 (2022).

Zhang, Y. P. et al. Characterization of the complete Chloroplast genome of Phalaenopsis lobbii (Orchidaceae), an important horticultural plant in China. Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 5, 3468–3469. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2020.1823902 (2020).

Szlachetko, D. et al. First Guatemalan record of natural hybridisation between Neotropical species of the Lady’s slipper Orchid (Orchidaceae, Cypripedioideae). Peerj 5, e4162. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4162 (2017).

Gorniak, M. et al. Taxonomic placement of Paphiopedilum canhii (Cypripedioideae; Orchidaceae) based on cytological, molecular and micromorphological evidence. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 70, 429–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2013.08.016 (2014).

Frazer, K. A. et al. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W273–W279. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkh458 (2004).

Li, H. E. et al. CPJSdraw: analysis and visualization of junction sites of Chloroplast genomes. PeerJ 11, e15326. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.15326 (2023).

Funding

The work was supported by grants from Beijing Landscaping and Greening Young Innovative Talents Support Project [Grant No. KJCX202319].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B. Z. and Y. W. were involved in the conception and design, drafting of the paper, revising it critically for intellectual content; Q. W., J. (A) and (B) Z. were involved in the material preparation, data collection and analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Q. W. and J. A., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., An, J., Wang, Y. et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequences of three Cypripedium species and their phylogenetic analysis. Sci Rep 15, 13461 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98287-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98287-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Integrative taxonomic revision of three Camellia species from section Tuberculata (Camellia, Theaceae) by morphological, anatomical, palynological, and molecular evidence

Botanical Studies (2026)

-

Demographic history and identification of threats under climate and anthropogenic activity provide insights into conservation for Cypripedium palangshanense

BMC Plant Biology (2026)