Abstract

The design parameters of the dynamic vibration absorber notably affect the motion space of the main system. A complete new universal method of attaining the explicit exact solution to the optimum damping was proposed to enhance the accuracy of calculating the dynamic vibration absorber’s parameters. The interaction between the main system and dynamic vibration absorber taken into account, many exact analytic solutions, for example displacement amplitude amplification factor, stiffness ratio, fixed point coordinate, optimum damping ratio, and phase angle difference, were investigated with the real number form of differential equation of load motion and using L’Hospital first rule in minute detail. Some characteristic parameters of both the main system and dynamic vibration absorber were gotten. The mechanism of the dynamic vibration absorber was analyzed by comparing the displacement amplitude amplification factor between the dynamic vibration absorber and main system. Generally speaking, the dynamic vibration absorber lags behind the main system by certain degrees. The fixed point theory essentially achieves the extreme large value, but not the maximum value, which is a natural shortcoming required to be overcome. The maximum value of the displacement amplitude amplification factor was acquired adopting MATLAB® Version 7.9.0.529 (R2009b). The relative error between the extreme large value and maximum value increases with the increase in the mass ratio. The relative error between the extreme large value and maximum value is 1.3018–10.397% for the optimum damping ratio. The present solutions would be useful to realize and control the precise dynamic characteristics of the main system and dynamic vibration absorber in practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction and motivation

A machine or machine component, on which a steady alternating force with variable frequency is acting, can take up obnoxious vibration, particularly when the machine or machine component approaches to the resonance. In order to improve the above-mentioned vibration condition, one can first attempt to eliminate the force. However, quite often this method also is inapplicable, impractical or even impossible. Therefore one might change the mass or spring stiffness of the main system in an attempt to get away from such the resonance situation, but in many cases this method also is inappropriate.

The past 116 years have witnessed an intense international research from theory and experiment in the field of the dynamic vibration absorber, invented by Frahm in 1909. Den Hartog1 deduced the tuning ratio of the dynamic vibration absorber with respect to the main system. Timoshenko2 found a simple formula giving the proper way of tuning the dynamic vibration absorber. In 1928, Ormondroyd and Den Hartog proposed the optimization principle of the dynamic vibration absorber in terms of minimizing the maximum amplitude response of the main system. Five years later in 1933, following this principle, Hahnkamm3 deduced the relationship for the optimum tuning ratio of the dynamic vibration absorber for the first time. Thirteen years later in 1946, Brock4 is prejudiced against note and only one page paper which are not self-contained and self-explanatory, and directly presented formulas for the optimum damping ratio for three cases of the dynamic vibration absorber with damping. One year later, Brock5 corrected the equation for the square of the damping ratio. Shen and Peng et al.6 analytically studied the optimal parameters of a dynamic vibration absorber with negative stiffness by Laplace transform method when the primary system is subjected to harmonic excitation. Shen and Xing et al.7 presented a novel dynamic vibration absorber with grounded stiffness element and amplifying mechanism, and the optimal parameters were studied in detail. Combining the two factors weighted by the dynamic-static proportion, Su and Bian et al.8 defined and optimized the control performance factor on the peak response. Based on analytical H∞ and H2 optimization, Su and Bian et al.9 derived the formulas of the optimal parameters for the lever-type inerter-based vibration absorber. Using a translational 1-DOF vibration system and a continuous body as the host structure, Yamada and Asami10 theoretically derived the governing equations to accurately estimate the mass ratio of the beam-type dynamic vibration absorber and the equivalent stiffness ratio of the piezoelectric elements. Mahé and Renault et al.11 assessed the dynamic stability of this centrifugal pendulum vibration absorber and the shifting of its operating point using an analytic dynamical model based on a perturbation method. Tian and Gao12 suspended the in-wheel-drive motor as a mass block, thereby mounted a dynamic vibration absorber on the unsprung mass to absorb the vibration. Harouni and Attari et al.13 solved the governing equations by the multiple scale method, and examined, discussed and compared the answers and their stability. Alvis and Abdelkefi14 developed the nonlinear reduced-order model through modifying trilinear spring models to represent the impact forces, a modified van der Pol oscillator to represent the forcing due to the vortex-induced vibrations and using the Euler–Lagrange principle to express the equations of motion. Roozen and Urbán et al.15 tested a number of different dynamic vibration absorber designs on a silicate cement brick wall in a transmission loss facility. Park and Kwak et al.16 used theoretical and experimental methods to realize an ultrahigh-density acoustic metasurface consisting of thin membranes decorated with a coiled ring. Love and Taylor17 presented a method employing principal component analysis to transform the dynamic vibration absorber loading time series into M orthogonal principal components. By conducting a theoretical analysis and a numerical simulation based on a simplified analytical model, Maegawa and Itoigawa18 established a design standard that presents the appropriate design conditions for dynamic vibration absorbers to achieve smooth sliding without stick–slip. Rasid and Mizuno et al.19 gave information about the low-frequency acceleration of active dynamic vibration absorber as an accelerometer. Hua and Wong et al.20 proposed and optimized a beam-based dynamic vibration absorber for minimizing the resonant vibration of a general structure. Zhou and Jean-Mistral et al.21 investigated two configurations of dynamic vibration absorber in conjunction with negative stiffness and conducted their parameter optimization according to two tuning methodologies: the fixed points theory and the stability maximization criterion. In order to validate the closed solutions, Barredo and Blanco et al.22 formulated an optimization problem for minimizing the standard deviation of difference among vibration amplitudes under an excitation frequencies range. Barredo and Larios et al.23 studied two different excitation sources of random loads which are random ground motion and force excitation. Kiran and Al-Osta et al.24 considered a damped system with a single degree of freedom (SDOF) and supplementary dampers, including negative stiffness and inerter-based damper, to control the response based on H2 optimum control strategies. Kiran and Al-Osta et al.25 considered the nonlinear force–deformation behavior of the tuned mass damper-clutching inerter (TMDCI) under non-stationary earthquake excitation for obtaining the stochastic response of isolated structures using a time-dependent equivalent linearization technique. Kiran and Ahmad et al.26 presented a study on optimizing the combination of a tuned mass damper inerter and a negative stiffness damper (TMDI-NSD) for better performance of structures against seismic actions. In order to increase the efficiency of the structures to resist seismic excitation, Kiran and Al-Osta et al.27 used combinations of inerter, negative stiffness, and tuned mass damper. Kiran and Farsangi et al.28 used an innovative combination of negative stiffness and an inerter control mechanism to protect a structure under severe seismic loadings.

Up to now, the mechanics and exact parameter optimization method of the dynamic vibration absorber are not completely researched. Several detailed shortcomings of research results on the dynamic vibration absorber are as follows: (1) the real number force \(F\sin \omega t\) and complex number force \(F{\text{e}}^{i\omega t}\) are not discriminated, and the complex number response displacement and real number response displacement amplitude are not distinguished, too; (2) all amplitude-frequency response characteristic curves pass through several fixed points independent of the damping ratio, but these fixed points are the extreme large value points not the maximum value points at all; and (3) to the author’s knowledge and to my regret, there is not a universal method attaining the exact solution to the optimum damping ratio of the dynamic vibration absorber.

A complete new universal method of attaining the explicit exact solution to the optimum damping of the dynamic vibration absorber was put forward. A lot of exact analytic solutions, such as displacement amplitude amplification factor, stiffness ratio, fixed point coordinate, and phase angle difference, were deduced in detail. The optimum damping ratio of the dynamic vibration absorber was attained using L’Hospital first rule. Some characteristic parameters of both the main system and dynamic vibration absorber were calculated. The mechanism of the dynamic vibration absorber was analyzed through comparing the displacement amplitude amplification factor between the dynamic vibration absorber and main system.

Displacement amplitude amplification factors of main mass and attached mass

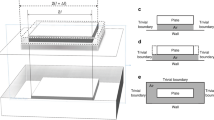

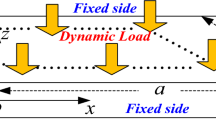

In Fig. 1 let the combination m1, k1 be the schematic representation of the main system under consideration, with the alternating force \(F\sin \omega t\) acting on it, where m1 is named the main mass, and k1 the main stiffness. The dynamic vibration absorber consists of a comparatively small vibration system m2, k2, K, c, where m2 is named the attached mass, k2 the attached stiffness, K the connection stiffness, and c the connection damping.

There is an oil or air dashpot mechanism arranged parallel connection to the damper spring K, between two masses m1 and m2. The coefficient c is a constant depending on the kind of the damping device and numerically is equal to the magnitude of the damping force when the velocity is equal to unity. In deriving the differential equation of motion we will use Newton’s second law stating that the product of the mass of a particle and its acceleration is equal to the force acting in the direction of acceleration. The differential equation of load motion is in the matrix form

where x1 and x2 present the displacement of masses m1 and m2, F the amplitude of sine harmonic oscillating force, ω the forced angular frequency, and t the time. The acceleration of the body m is given by the second derivative of the displacement x with respect to time and will be denoted by \(\ddot{x} = \frac{{{\text{d}}^{2} x}}{{{\text{d}} t^{2} }}\). The velocity of the body m is given by the first derivative of the displacement x with respect to time and will be denoted by \(\dot{x} = \frac{{{\text{d}} x}}{{{\text{d}} t}}\). Assume that the vibrating body m encounters in its motion a resistance proportional to the velocity.

In terms of Euler’s formula \({\text{e}}^{ix} = \cos x + {\text{i}} \sin x\), Eq. (1) is viewed as the imaginary part of the following expression

where the lower case letter e denotes the natural constant invented by Euler in the first instance, the Roman type \({\text{i}} = \sqrt { - 1}\) often named the imaginary (or imkginaire in French) unit introduced by Euler at the beginning. Consequently choose the imaginary part of X, \(x_{1} = {\text{Im}} X_{1}\), \(x_{2} = {\text{Im}} X_{2}\).

One particular solution of Eq. (2) will be of the form

Substituting Eq. (3) into Eq. (2) yields

After performing some algebra Eq. (5) is transformed into

To simplify our further discussion we bring these expressions into dimensionless form. For this purpose we introduce the following notations.

Where \(\mu = \frac{{m_{2} }}{{m_{1} }}\) stands for the mass ratio; \(f = \frac{{\omega_{2} }}{{\omega_{1} }}\) is the tuning ratio, thereof \(\omega_{2} = \sqrt {\frac{{k_{2} }}{{m_{2} }}}\) the natural angular frequency of dynamic vibration absorber, and \(\omega_{1} = \sqrt {\frac{{k_{1} }}{{m_{1} }}}\) the natural angular frequency of main system; \(k = \frac{K}{{k_{1} }}\) is the stiffness ratio; \(\zeta = \frac{{c\omega_{1} }}{{2k_{1} }}\) represents the damping ratio; and \(g = \frac{\omega }{{\omega_{1} }}\) is the forced angular frequency ratio. Five dimensionless variables of μ (determining m2), f (m2 having been determined, thus determining k2), k (determining K), ζ (determining c), and g (determining ω) are mutually independent.

By Eq. (6), we have

So that

Hence \(X_{1} = \left| {\hat{X}_{1} } \right|{\text{e}}^{{i\varphi_{1} }} {\text{e}}^{i\omega t} = \left| {\hat{X}_{1} } \right|{\text{e}}^{{i(\omega t + \varphi_{1} )}} = \left| {X_{1} } \right|{\text{e}}^{{i(\omega t + \varphi_{1} )}}\), \(x_{1} = \left| {X_{1} } \right|\sin (\omega t + \varphi_{1} )\); \(X_{2} = \left| {X_{2} } \right|{\text{e}}^{{i(\omega t + \varphi_{2} )}}\), \(x_{2} = \left| {X_{2} } \right|\sin (\omega t + \varphi_{2} )\).

Five-parameter universal displacement amplitude amplification factors for the steady state response of the main mass and dynamic vibration absorber can be expressed as two important expressions, respectively

Using Eqs. (10) and (11), for the given four dimensionless variables of μ, f, k, ζ, the (g, A) diagram can be obtained, where g is the abscissa, and A is the ordinate.

Conditions for equal ordinates of two fixed points of main system

Three fixed points of main system independent of damping ratio

Now return to Eq. (10) to see whether there are any values of g for which A1 becomes irrelevant to ζ. The formula is expressed as

We can obliterate the square sign on both sides but then have to add a ± in front of the right-hand side, or written out fully, if

With the plus sign, Eq. (13) gives

After cross-multiplication, whence the abscissa of only one fixed point N of the (g, A1) diagram is

Substituting Eq. (15) into the right-hand side of Eq. (12) or (14) reads the ordinate of fixed point N of the (g, A1) diagram

The other alternative is the minus sign before the right-hand side of Eq. (13)

After a short calculation the equation then becomes

This is a quadratic equation in one unknown g2, giving two roots, the fixed points S and T we are seeking. Let two roots of this equation be \(g_{S}^{2}\) and \(g_{T}^{2}\). It is seen that gS and gT (i.e., the horizontal coordinates of the fixed points S and T) are still functions of μ, f, and k. The root discriminant of the quadratic equation in one unknown (18) is

Equation (19) can be spread out to the form

Again Eq. (20) can be spread out to the form

At last Eq. (21) can be reduced to the form

According to the extracting root formula of quadratic equation in one unknown, the abscissas of fixed points S and T of the (g, A1) diagram are, respectively

According to Eq. (18), we construct the following auxiliary function

Through Eqs. (25), (18), (23) and (24), we get

Equation (27) can be reduced to the form

Equation (28) can be spread out to the form

Finally Eq. (29) can be reduced to the form

Through Eqs. (18), (26), (30) and the open upward property of parabola, we have

Substituting Eqs. (23) and (24) into the right-hand side of Eq. (12) or (17) reads the ordinates of fixed points S and T of the (g, A1) diagram, respectively

Four fixed points of dynamic vibration absorber independent of damping ratio

Now return to Eq. (11) to see whether there are any values of g for which A2 becomes independent of ζ. The formula is of the form

We can obliterate the square sign on both sides but then have to add a ± in front of the right-hand side, or written out fully

With the plus sign, Eq. (35) gives

After cross-multiplication, whence the abscissas of two fixed points N and W of the (g, A2) diagram are, respectively

Substituting Eq. (37) into the right-hand side of Eq. (34) or (36) reads the ordinates of two fixed points N and W of the (g, A2) diagram, respectively

According to Eqs. (15) and (37), as well as Eqs. (16) and (38), the coordinates of the fixed point N in the dynamic vibration absorber are the same as those in the main system. The other alternative is the minus sign before the right-hand side of Eq. (35)

After a short calculation the equation then becomes

The discriminant of the quadratic Eq. (40) is

Equation (41) can be spread out to the form

Equation (42) can be reduced to the form

To the last Eq. (43) can be reduced to the form

The abscissas of fixed points V and M of the (g, A2) diagram are, respectively

According to Eq. (40), we constitute the following auxiliary function

Through Eqs. (47), (40), (45) and (46), we get

Equation (49) can be reduced to the form

Finally Eq. (50) can be reduced to the form

Through Eqs. (40), (48), (51) and the open upward property of parabola, we have

Substituting Eqs. (45) and (46) into the right-hand side of Eq. (34) or (39) reads the ordinates of fixed points V and M of the (g, A2) diagram, respectively

Equal ordinates of two fixed points S and T of main system

Through Eqs. (23) and (24), we have (or the sum of two roots of quadratic equation in one unknown (18))

By changing the stiffness ratio k, two fixed points S and T can be shifted up and down the curve for ζ = 0. By changing k, one point goes up and the other down. Clearly the most favorable case is such that first by a proper choice of k two fixed points are adjusted to equal heights. The next objective is to adjust the stiffness ratio k so that the ordinates of two fixed points S and T are equal, viz.

Substitute this condition (56) in Eqs. (32) and (33) with the result that

Equation (57) is equal to Eq. (55) with the optimum stiffness ratio

Inserting Eq. (58) into Eqs. (23) and (24), respectively, produces

Inserting Eq. (59) into Eq. (32) and inserting Eq. (60) into Eq. (33) produce the extreme large value

According to Eqs. (16) and (61) we can obtain this inequality \(A_{1N} < A_{1S} = A_{1T}\). Figure 2 represents displacement amplitude amplification factors for the steady state response of the main system at two fixed points S and T for μ = 0.25 and the arbitrary k. In Fig. 2a, there exists an optimum operating point Q whose abscissa is 0.096 (in terms of Eq. (58)) and whose ordinate is 5 (in terms of Eq. (61)). In Fig. 2b, there exists an inequality \(A_{1S} > A_{1T}\).

Coordinates of two fixed points V and M of dynamic vibration absorber for optimum stiffness ratio

Inserting Eq. (58) into Eq. (45) produces

Equation (62) can be spread out to the form

In the end, we attain the following results

Inserting Eq. (64) into Eq. (53) produces

Inserting Eq. (65) into Eq. (54) produces

According to Eqs. (67), (38) and (66) we can obtain this inequality \(A_{2M} < A_{2N} < A_{2W} < A_{2V}\).

Optimum damping ratio of dynamic vibration absorber

Figure 3 represents the amplitude-frequency response characteristic curve of main mass for μ = 0.25, \(f = \frac{{\sqrt {10} }}{5}\) and some different damping ratios. The maximum displacement amplitude amplification factor of main mass A1max(ζ) decreases at first and then increases with the increase of the damping ratio ζ. In Fig. 3a, the maximum value becomes A1max(ζ = 0) = + ∞. In Fig. 3b, the maximum value becomes A1max(ζ = 0.01) = 12.37. In Fig. 3c, the maximum value becomes A1max(ζ = 0.0267) = 5.504. In Fig. 3d, when the maximum displacement amplitude amplification factor becomes the minimum value min{A1max(ζ)}, the optimum damping ratio is ζ = 0.0351. If ζ = 0, the damping force is zero, no work is done, and hence the resonant amplitude is infinite. But when ζ = + ∞, two masses are locked to each other so that their relative displacement is zero and again no work is done. Somewhere in between 0 and + ∞ there is a damping for which the product of damping force and displacement becomes a maximum, and then the resonant amplitude will be small. In Fig. 3e, the maximum value becomes A1max(ζ = 0.05) = 6.828. In Fig. 3f, the maximum value becomes A1max(ζ = + ∞) = + ∞.

Figure 4 represents the maximum displacement amplitude amplification factor of the main mass as a function of the damping ratio for μ = 0.25 and \(f = \frac{{\sqrt {10} }}{5}\). It is interesting to follow that a V-shaped curve happens for increasing damping. When the damping becomes infinite, two masses m1 and m2 are virtually clamped together and we have a single-degree-of-freedom system with a mass m1 + m2. In adding the dynamic vibration absorber to the main system, the object is to bring the resonant peak of the amplitude down to its lowest possible value. With ζ = 0 the peak is infinite; with ζ = + ∞ it is again infinite. Somewhere in between there must be a value of ζ for which the peak becomes a minimum. Firstly according to Eq. (10), A1max can be attained for 0 ≤ g < + ∞. Secondly in Fig. 4 the maximum displacement amplitude amplification factor reaches minimum value for corresponding damping ratio 0.025.

Start from Eq. (10)

On the basis of the formula for the difference of squares, Eq. (68) can be written as

Optimum damping ratio at fixed point S

Introducing Eq. (32) into Eq. (17) leads to

From Eq. (32) we find

Introducing Eqs. (70) and (71) into Eq. (69) leads to

The conventional method such as H∞ took a slightly different quantity only instead of gS, that is to say \(g = g_{S} + 10^{ - 6}\), etc. The conventional method such as H∞ is approximate. L’Hospital rule (or L’Hôpital in French) is divided into L’Hospital first rule and L’Hospital second rule. L’Hospital rule is exact. According to Eqs. (70) and (71), as \(g \to g_{S}\), both the numerator and denominator of the right-hand side of Eq. (72) approach zero, and this indeterminant expression must be evaluated by using L’Hospital first rule. The limiting form of Eq. (72) can be rewritten as

According to L’Hospital first rule, the numerator and denominator of the right-hand side of Eq. (73) should be separately differentiated with respect to g to yield the limiting form of this equation as

Introduce Eqs. (58), (59) and (61) into Eq. (74). This is a long and tedious job, which leads to the result

Introducing Eq. (59) into Eq. (75), we obtain

Rationalizing the result, we obtain the optimum damping ratio at fixed point S arranged in the ascending form of μ

Because of \(\zeta = \frac{{c\omega_{1} }}{{2k_{1} }} = \frac{{c\omega_{1} }}{{2m_{1} \omega_{1}^{2} }} = \frac{c}{{2m_{1} \omega_{1} }} = \mu \frac{c}{{2m_{2} \omega_{1} }} = \mu \zeta_{{\text{Den}}}\). When f = 0, we obtain the conventional result1 \(\zeta_{S} = \mu \sqrt {\frac{\mu }{{8(1 + \mu )^{3} }}\left( {3 - \sqrt {\frac{\mu }{2 + \mu }} } \right)} = \mu \zeta_{{\text{Den}}}\).

Optimum damping ratio at fixed point T

Introducing Eq. (33) into Eq. (17) leads to

From Eq. (33) we find

Introducing Eqs. (78) and (79) into Eq. (69) leads to

With the aid of L’Hospital first rule, the limiting form of Eq. (80) can be rewritten as

Separately differentiating the numerator and denominator with respect to g attains

Introducing Eqs. (60), (58) and (61) into Eq. (82) leads to

Introducing Eq. (60) into Eq. (83), we obtain

Rationalizing the result, we deduce the optimum damping ratio at fixed point T

The real-world scenarios include the main system having damping force and nonlinear superstructures studied in the future research.

Characteristics of main system and dynamic vibration absorber

Figure 5 represents the amplitude-frequency response characteristic curve of the main mass for μ = 0.25, \(f = \frac{{\sqrt {10} }}{5}\) and two optimum damping ratios. The curve of Fig. 5a shows that there is a horizontal tangent line at point S whose extreme large value is 5 smaller than the maximum value 5.504. Point S has the extreme large value but not the maximum value. The curve of Fig. 5b shows that there is a horizontal tangent line at point T whose extreme large value is 5 also smaller than the maximum value 5.273. Point T also has the extreme large value but not the maximum value. Both the fixed point S and point T have the extreme large value but not the maximum value. In Fig. 5 large difference is absorbed, for example 5 and 5,504, or 5 and 5.273.

The quantity A1S of Eq. (61) denotes an extreme large value at fixed point S. In Fig. 3c we obtain a maximum value A1max(ζS) for the optimum damping ratio ζS. The relative error between the extreme large value at fixed point S and maximum value is denoted by

The quantity A1T of Eq. (61) denotes an extreme large value at fixed point T. In Fig. 3d we obtain a maximum value A1max(ζT) for the optimum damping ratio ζT. The relative error between the extreme large value at fixed point T and maximum value is denoted by

The relative error between the extreme large value and maximum value is shown in Fig. 6 and the corresponding data are given in Table 1 for \(f = \frac{{\sqrt {10} }}{5}\). It is seen that the relative error between the extreme large value and maximum value increases with the increase in the mass ratio. The relative error between the extreme large value at fixed point S and maximum value is 1.6983–24.650%. The relative error between the extreme large value at fixed point T and maximum value is 1.3018–10.397%. The relative error at the fixed point T is smaller than one at the fixed point S. The optimum damping ratio is chosen as the form of Eq. (85) at the fixed point T.

Figure 7 represents the amplitude-frequency response characteristic curve of the main mass for μ = 0.25 for different damping ratios. We observe a remarkable peculiarity, viz., that all four curves intersect at three fixed points N, S, and T. This, we shall presently prove, is no accident; all curves pass through these three fixed points independent of the damping ratio. By a proper choice of ζ the curve is adjusted to pass with a horizontal tangent line through one of them. Two curves are drawn. One curve at the optimum damping ratio ζS passes horizontally through the fixed point S and then is not horizontal at the fixed point T; the other curve at the optimum damping ratio ζT is horizontal at the fixed point T and not at the fixed point S. The main system has three fixed points just mentioned independent of the damping ratio.

Figure 8 represents the amplitude-frequency response characteristic curve of the attached mass for μ = 0.25 and four various degrees of damping ratios. The dynamic vibration absorber has four fixed points N, V, W, and M independent of the damping ratio. From Figs. 7 and 8, the amplitude-frequency response characteristic curve is continuous for 0 < ζ < + ∞. The amplitude-frequency response characteristic curve has two open upward peaks for zero damping ratio, where the amplitudes become infinitely large. The amplitude-frequency response characteristic curve has only one open upward peak for infinite damping ratio. In Figs. 7a and 8a, the three vertical asymptotic line equations from left to right are g = 0.8322, g = 0.9381, and g = 1.0897, respectively. In Figs. 7b and 8b, the three vertical asymptotic line equations from left to right are g = 0.6983, g = 0.8944, and g = 1.1456, respectively.

According to Eqs. (61) and (66) we can obtain an important inequality \(A_{1S} = A_{1T} < A_{2V}\). Figure 9 represents the amplitude-frequency response characteristic curves of the main mass and attached mass for \(f = \frac{{\sqrt {10} }}{5}\). It is seen that the displacement amplitude amplification factor of the attached mass is quite large, three or four times as large as that of the main mass, therefore large difference is absorbed. The small amplitudes of the main mass are obtained at the expense of large deflections and stresses in the dynamic vibration absorber.

Equation (9) divided by Eq. (8) equals

in which the quantity \(\varphi = \arg \frac{{\hat{X}_{2} }}{{\hat{X}_{1} }} = \omega t + \varphi_{2} - (\omega t + \varphi_{1} ) = \varphi_{2} - \varphi_{1}\) is known as the phase angle difference between the displacements x2 and x1. The argument φ is the principal value as defined by \(- {\uppi } < \varphi \le {\uppi }\). As \(g \to 0\), so \(\varphi \to 0\), or as ζ = + ∞, the dynamic vibration absorber and main system are in phase. As \(g \to + \infty\), so \(\varphi \to - \frac{{\uppi }}{2}\) rad, the dynamic vibration absorber lags behind the main system by 90°. At the fixed point N, we obtain that the dynamic vibration absorber and main system are in phase, namely

Figure 10 represents the phase angle difference between the dynamic vibration absorber and main system for μ = 0.25 and six amounts of damping ratios. When ζ = 0, the phase angle difference mutates from 0° to − 180°, namely from in phase to in reverse phase. Basically, the dynamic vibration absorber lags behind the main system by some degrees.

Conclusions

(1) A complete new universal method of attaining the explicit exact solution to the optimum damping was proposed to enhance the accuracy of calculating the dynamic vibration absorber’s parameters. The attached mass was also suggested in coincidence with the main mass. The interaction between the main system and dynamic vibration absorber taken into account, a series of exact analytic solutions of displacement amplitude amplification factor, stiffness ratio, fixed point coordinate, and phase angle difference were deduced from the real number form of differential equation of load motion. The most important work in this paper is to attain the optimum damping ratio of the dynamic vibration absorber using L’Hospital first rule.

(2) Some characteristic parameters of both the main system and dynamic vibration absorber were calculated simultaneously. The mechanism of the dynamic vibration absorber was analyzed through comparing the displacement amplitude amplification factor between the dynamic vibration absorber and main system. The dynamic vibration absorber is out of phase with the main system. Basically, the dynamic vibration absorber lags behind the main system by some degrees.

(3) To one’s disappointment, some current references thought that the maximum value of the fixed point of the main system was obtained. In fact, the fixed point theory can obtain the extreme large value, but not the maximum value, which is a natural shortcoming not to be overcome. The maximum value of the displacement amplitude amplification factor could be attained in this paper using MATLAB® Version 7.9.0.529 (R2009b). The relative error between the extreme large value and maximum value increases with the increase in the mass ratio. The relative error between the extreme large value and maximum value is 1.3018–10.397% for the optimum damping ratio.

(4) The establishment of solving method using L’Hospital first rule will provide a theoretical foundation for attaining the precise optimum parameter of the dynamic vibration absorber. The solving method in this paper is applicable to other complex dynamic vibration absorbers.

At all events the findings presented here constitute another step toward the goal of establishing a sound basis for precisely predicting the dynamic characteristics of the main system and dynamic vibration absorber to be expected from some given known parameters of the main system, and for “designing” the desired efficient dynamic vibration absorber, completely without being bound to empiricism and any experimental measurement.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Den Hartog, J. P. Mechanical Vibrations 4th edn, 87–106 (Dover Publications, 2016).

Timoshenko, S. Vibration Problems in Engineering 2nd edn—fifth printing, 240–252 (D. Van Nostrand, 1946).

Hahnkamm, E. Die dämpfung von fundamentschwingungen bei veränderlicher erregerfrequenz. Ingenieur-Archiv. 4(2), 192–201 (1933) (in German).

Brock, J. E. A note on the damped vibration absorber. J. Appl. Mech. 13(4), A-284 (1946).

Brock, J. E. Author’s correction. J. Appl. Mech. 14(1), A-80 (1947).

Shen, Y. J., Peng, H. B., Li, X. H. & Yang, S. P. Analytically optimal parameters of dynamic vibration absorber with negative stiffness. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 85, 193–203 (2017).

Shen, Y. J., Xing, Z. Y., Yang, S. P. & Sun, J. Q. Parameters optimization for a novel dynamic vibration absorber. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 133, 106282 (2019).

Su, N., Bian, J., Peng, S. T., Chen, Z. Q. & Xia, Y. Analytical optimal design of inerter-based vibration absorbers with negative stiffness balancing static amplification and dynamic reduction effects. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 192, 110235 (2023).

Su, N., Bian, J., Chen, Z. Q. & Xia, Y. A novel lever-type inerter-based vibration absorber. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 254, 108440 (2023).

Yamada, K. & Asami, T. Passive vibration suppression using 2-degree-of-freedom vibration absorber consisting of a beam and piezoelectric elements. J. Sound Vib. 532, 116997 (2022).

Mahé, V., Renault, A., Grolet, A., Mahé, H. & Thomas, O. On the dynamic stability and efficiency of centrifugal pendulum vibration absorbers with rotating pendulums. J. Sound Vib. 536, 117157 (2022).

Tian, M. J. & Gao, B. Z. Dynamics analysis of a novel in-wheel powertrain system combined with dynamic vibration absorber. Mech. Mach. Theory 156, 104148 (2021).

Harouni, P., Attari, N. K. A. & Rofooei, F. R. Evaluation of a robust dynamic vibration absorber based on negative stiffness and internal resonance against seismic excitation. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 146, 104130 (2022).

Alvis, T. & Abdelkefi, A. Efficacy of vibro-impact energy harvesting absorbers on controlling dynamical systems under vortex-induced vibrations and base excitation. Ocean Eng. 272, 113816 (2023).

Roozen, N. B., Urbán, D., Piana, E. A. & Glorieux, C. On the use of dynamic vibration absorbers to counteract the loss of sound insulation due to mass-spring-mass resonance effects in external thermal insulation composite systems. Appl. Acoust. 178, 107999 (2021).

Park, J. J., Kwak, J. H. & Song, K. Ultraslow medium with an acoustic membrane-like undamped dynamic vibration absorber for low-frequency isolation. Extreme Mech. Lett. 43, 101203 (2021).

Love, J. S. & Taylor, Z. J. A method to generate dynamic vibration absorber load combinations. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 194, 103977 (2019).

Maegawa, S. & Itoigawa, F. Design method for suppressing stick-slip using dynamic vibration absorber. Tribol. Int. 140, 105866 (2019).

Rasid, S. M. R. et al. Design and control of active vibration isolation system with an active dynamic vibration absorber operating as accelerometer. J. Sound Vib. 438, 175–190 (2019).

Hua, Y. Y., Wong, W. & Cheng, L. Optimal design of a beam-based dynamic vibration absorber using fixed-points theory. J. Sound Vib. 421, 111–131 (2018).

Zhou, S. Y., Jean-Mistral, C. & Chesne, S. Closed-form solutions to optimal parameters of dynamic vibration absorbers with negative stiffness under harmonic and transient excitation. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 157–158, 528–541 (2019).

Barredo, E. et al. Closed-form solutions for the optimal design of inerter-based dynamic vibration absorbers. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 144, 41–53 (2018).

Barredo, E. et al. Optimal design for high-performance passive dynamic vibration absorbers under random vibration. Eng. Struct. 195, 469–489 (2019).

Kiran, K. K., Al-Osta, M. A., Ahmad, S. & Bahraq, A. A. Optimal design of tuned mass and negative stiffness amplifier dampers with inerter by H2 optimal control under bidirectional seismic load. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 50(3), 1753–1783. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-024-08960-4 (2025).

Kiran, K. K., Al-Osta, M. A., Ahmad, S. & Bahraq, A. A. A novel approach for vibration control of base-isolated structures under seismic load using a tuned mass damper-clutching inerter. J. Vib. Eng.Technol. 12(7), 8737–8757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42417-024-01387-z (2024).

Kiran, K. K., Ahmad, S., Al-Osta, M. A. & Bahraq, A. A. Enhancing the seismic resilience of structures by using optimum combination of tuned mass damper inerter and negative stiffness damper. Structures. 57, 105253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.105253 (2023).

Kiran, K. K., Al-Osta, M. A. & Ahmad, S. Optimum design and performance of a base-isolated structure with tuned mass negative stiffness inerter damper. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 4980. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31482-2 (2023).

Kiran, K. K., Farsangi, E. N. & Gharehbaghi, V. An innovative negative stiffness-inerter hybrid control device toward seismic-resilient structures. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 7, 310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41062-022-00904-x (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I myself have written the main manuscript text, reviewed the manuscript, analyzed the data and edited the revised version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

I declare that I have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence my work, there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service or company that could be construed as influencing the position presented in, or the review of, the manuscript entitled, “The damping of the dynamic vibration absorber”.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, Q. The damping of the dynamic vibration absorber. Sci Rep 15, 13917 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98320-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98320-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Validated design of a low-cost passive inerter system for multi-hazard structural resilience in tropical infrastructure

Innovative Infrastructure Solutions (2026)