Abstract

During the injection and withdrawal of natural gas, faults may cause lateral leakage, resulting in the loss or migration of natural gas out of the gas storage area. Therefore, the lateral sealing property of faults is crucial for the safe operation of gas storage facilities. This paper uses the L gas storage reservoir as a case study to conduct a statistical analysis of the fault dip, reservoir thickness, and overburden thickness within the faulted structure. It integrates a fault sealing triangle diagram derived from logging data to ascertain that the gas storage facility in this study primarily depends on lithological contact sealing and fault rock sealing mechanisms. Furthermore, it evaluates the sealing capacity of these confining faults and develops a quantitative model for assessing their lateral sealing capacity based on an anatomical examination of the original gas reservoir. Through the analysis of dynamic development data for the safe operation of gas storage facilities, pressure variations on both sides of the faults during different injection and production phases were systematically identified. The pressure differential at the end of production was selected, and a numerical simulation incorporating time effects was conducted to assess the dynamic sealing capacity of the fault. A model representing fault sealing capability based on this dynamic development data was established, which elucidates the sealing mechanisms present on either side of the fault across various periods and identifies factors (fluid pressure, tectonic stress, changes in fluid properties) contributing to pressure differentials. The model demonstrates 89% prediction accuracy through machine learning-assisted history matching of 12 injection-production cycles, significantly outperforming conventional methods by 32%. Additionally, the study discusses discrepancies in lateral sealing capacities among different stages and clarifies the fundamental reasons behind variations in pressure differences over time. These findings provide a robust theoretical foundation for assessing sealing capabilities in gas storage facilities during subsequent development phases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Underground gas storage is a vital component of the natural gas supply chain, playing a crucial role in enhancing energy security and supporting daily life. In recent years, driven by the rapid advancement of the natural gas industry and the gradual depletion of fault-associated oil and gas reserves, numerous depleted reservoirs have been repurposed as gas storage facilities due to their lower construction costs and adequate working gas capacities1,2,3. However, during the injection and extraction processes of natural gas, lateral seepage induced by faults may occur, resulting in either loss of natural gas or its migration to non-storage areas. Consequently, the lateral sealing capacity of faults is essential for ensuring the safe operation of these gas storages.

Various characterization methods have been developed and implemented to assess the sealing capacity of different types of fault seals. Whether considering lithological contact sealing or fault rock sealing, the underlying mechanism can be distilled to capillary sealing (or thin film sealing). The fundamental principle of lateral sealing by faults is rooted in the permeability contrast between the reservoir and the fault zone or counter-stratum. When the pore radius within the reservoir exceeds that of the fault zone or counter-stratum, a capillary pressure differential will direct towards the reservoir, thereby obstructing oil and gas from infiltrating into these zones and consequently inhibiting their lateral migration. Lithological contact sealing pertains to high-permeability reservoirs interfacing with low-permeability rocks, which exhibit robust sealing capabilities and effectively facilitate oil and gas accumulation. Regarding lithological contact sealing, Smith (1966) posits that high permeability reservoirs in conjunction with low permeability formations exhibit enhanced sealing efficacy for oil and gas accumulation; conversely, the interaction between high permeability reservoirs can lead to increased leakage risks4. Allen (1989) conducted an analysis of the lithology, geometric configurations, and projections of the strata on either side of the fault to construct a lithological contact map5. This methodology enables the identification of fault face contact types in scenarios where two or more faults intersect in three-dimensional space, thereby providing a more accurate and reliable characterization of fault rock type sealing6,7.

Knipe (1997) developed a fault triangle diagram to illustrate the relationships between adjacent formations under varying offset conditions, utilizing single-well logging data and lithological classification results8. The underlying principle involves analyzing single-well logging data to derive the clay content curve of the corresponding strata, which facilitates the differentiation between shale and sandstone layers. Subsequently, each layer of sandstone and shale is regarded as a fundamental unit within the fault triangle diagram, with the lithological connectivity among these units represented in Knipe’s triangular diagram. The introduction of this Knipe diagram offers an efficient and straightforward method for characterizing the lateral sealing capacity of faults, particularly advantageous during early exploration phases when drilling data is limited and research datasets are sparse. Meng et al. (2014) enhanced the traditional single well fault triangle representation method by introducing the double well triangle diagram, which effectively illustrates the lithological matching relationship between the upper and lower plates of a strike-slip fault9. The application of the double well triangle diagram allows for an accurate depiction of this lithological relationship under strike-slip conditions across varying vertical fault distances. Anderson and Reilly (2015) proposed two representation methods—the double well fault triangle diagram and the growth fault triangle diagram—to address discrepancies in thickness between the upper and lower strata associated with growth faults10. In comparison to the double well fault triangle diagram, the growth fault triangle diagram demonstrates effective applicability even when drilling data is limited11,12.

The characterization of the sealing capacity of fault rocks is inherently complex. Currently, the predominant approach for assessing the lateral sealing ability of fault rocks involves utilizing relevant param to define the composition of the fault zone, followed by establishing a correlation between these characterized param and the lateral sealing capacity of the fault. Under static water conditions, the effectiveness of a fault’s lateral sealing capability is contingent upon the capillary pressure differential between the fault and adjacent permeable reservoirs. According to Gibson (1994)13, both porosity and permeability within the fault zone are influenced by clay content, which serves to enhance capillary forces in this region. Overall, there exists a positive correlation between a fault’s sealing capacity and its clay content. Numerous researchers have sought to validate this conclusion through physical simulation experiments as well as numerical modeling studies14,15,16. Cuisiat et al. (2010) employed a high-pressure annular shear apparatus to simulate conditions at a depth of 1500 m below the surface. The experimental results indicated that under particulate flow conditions, mudstone smearing leads to a reduction in the permeability of the fault zone17. Additionally, the correlation between shale gouge ratio (SGR) and mudstone smearing was established. Through various physical simulation experiments, it can be concluded that clay content within fault rocks significantly influences both porosity and permeability in the fault zone. Consequently, identifying optimal param for characterizing fault mud content and calibrating these param to assess the sealing capacity of faults has become a widely adopted method for evaluating the sealing ability of fault rocks.

In recent years, building upon prior research regarding fault sealing capacity, several scholars have sought to incorporate additional factors into the representation of this capacity, including stress, dip angle, and dip direction, in order to facilitate a multi-factor analysis of fault sealing capacity18,19. Furthermore, machine learning algorithms have been integrated into the methods for representing fault sealing capabilities; for instance, predicting the height of hydrocarbon columns within fault-trapped reservoirs using Monte Carlo simulations20. This approach involves simulating various factors such as fault intersections, closures, hydrodynamic effects, and activation risks to ultimately assess the potential of oil reservoirs. Edmundson employed decision tree algorithms to predict the filling degree of fault traps, aiming to enhance the accuracy of oil and gas column height predictions21. However, multi-factorial and artificial intelligence methods necessitate a sufficiently large database for validation. Given that coal seam gas reservoirs are characterized by small traps and substantial reserves, these methodologies are not suitable for characterizing the fault closure capacity in such reservoirs22. The aforementioned characterization methods pertain exclusively to static water pressure conditions during geological history. Most assumptions regarding fault closure capacity during the development phase equate it with that observed in geological history23,24. Thus, methods based on original gas reservoir anatomy for characterizing fault closure capacity from geological history are inadequate for application during the development period25,26.

In the operation of depleted gas reservoir-type storage facilities governed by faults, these faults serve a critical sealing function for injected natural gas and effectively mitigate the escape of this gas. The sealing capacity of faults represents a significant consideration in the management of such facilities. Investigating fault sealing mechanisms and classifications is fundamental to characterizing their sealing capabilities. By comprehensively understanding the causes behind fault sealing and identifying factors that influence their sealing effectiveness, various types of fault seals can be efficiently and accurately assessed using distinct characterization methods.

The paper initially provides a systematic classification of sealing fault types within the L gas reservoir, revealing that the predominant sealing mechanisms are lithological contact sealing and fault rock sealing. In comparison to lithological contact sealing, fault rock sealing exhibits a diminished capacity for containment, presenting a notable risk of leakage. It is imperative to undertake a comprehensive characterization of its vulnerabilities. When evaluating the sealing efficacy of fault rocks, the critical factor is the displacement pressure differential generated by the fault zone within the reservoir strata. The findings indicate that the sealing capacity of faults correlates positively with this displacement pressure differential, which is primarily influenced by the clay content present in inclusions within the fault zone. Finally, through an analysis of data from drilled wells and inferring the original gas reservoir’s sealing capability based on water-gas relationships on either side, a methodology grounded in original gas reservoir anatomy was developed to characterize the lateral sealing capacity of control faults in the L gas reservoir.

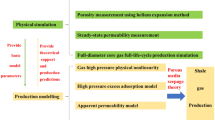

Methodology

Firstly, based on the logging interpretation results of the oil reservoirs in the study area, the original gas reservoir characteristics and the current development status, this study determines the sealing types of different faults by systematically comparing key param such as the thickness ratio of reservoir to cap rock (TGR) and the fault throw-to-cap rock thickness matching coefficient (DTR). For the weak sealing units of fault rocks, the sealing capacity is characterized, and the sealing capacity of the original gas reservoir is inferred based on the relationship between the gas-water interface on both sides of the fault. A sealing capacity characterization model based on the original gas reservoir anatomy is established to quantitatively characterize the lateral sealing capacity of the L gas storage reservoir control faults during the geological history period.

During the dynamic development stage, the injection and production dynamic monitoring data for the safe operation of the gas storage reservoir are processed and analyzed to clarify the pressure change characteristics on both sides of the faults within each injection and production cycle. The maximum pressure difference at the end of gas production is selected to establish a fault sealing capacity characterization model based on dynamic development data. This model is combined with the numerical simulation of the dynamic sealing capacity of faults considering the time effect to deeply study the sealing mechanism and influencing factors of the pressure difference on both sides of the faults at different periods, and to reveal the fundamental reasons for the differences in the sealing pressure difference on both sides of the faults under different conditions.

The investigation into the sealing capacity of faults in the L gas storage during the development phase will be enhanced by refining the characterization method for lateral fault sealing based on original reservoir anatomy. This study will utilize injection and production data from L gas storage to characterize the lateral sealing capacity of faults, integrating this with numerical simulations of dynamic sealing capacity that account for temporal effects. Ultimately, a time-dependent assessment of fault sealing capacity will be achieved. The results from this characterization will then be compared and analyzed alongside geological history-based fault sealing capacity assessments derived from actual injection and production data, revealing that these findings align more closely with real-world production conditions than conventional methods.

Evaluation of fault sealing ability in geological historical periods

Basic param for controlling the closure of fault zones

Through the analysis of the sealing elements in each block of the L gas storage, it was determined that the original oil and gas reservoir is governed by faults, underscoring the critical importance of fault lateral sealing capacity in both original oil and gas accumulation and current gas storage operations. Initially, a quantitative representation model for assessing fault lateral sealing capacity during geological history was developed, grounded in a detailed quantitative analysis of the sealing capabilities observed in drilled gas reservoirs, while establishing a quantitative correlation with the clay content present within fault materials. It is essential to undertake comprehensive research on fault sealing capacity to accurately characterize its historical performance.

To analyze the fault sealing capacity during geological history, it is essential to evaluate this capacity based on the oil and gas filling state of that period. A commonly employed method involves a detailed examination of the sealing capacity in drilled oil and gas reservoirs associated with faults, allowing for the determination of the actual sealing pressure differential across these faults. The initial step is to investigate the sealing capacity of faults within the target layer of the research area that have been drilled, assessing whether these controlling faults possess effective sealing capabilities. If a significant fluid pressure difference exists between both sides of a fault, it can be concluded that this fault exhibits certain sealing capability. The pressure differential across the fault represents its transmissibility. If the gas-water contact (GWC) within the reservoir is entirely governed by this fault’s sealing ability, then this pressure difference reflects its overall sealing capacity and can be equated to what is known as breakthrough pressure.

Utilizing existing well log data and reservoir cross-sectional maps, statistical analysis is performed on the relevant wells within the closure to ascertain the elevation of the gas cap for each well. The difference between the elevations of the gas cap and gas floor is then calculated to derive the height of each gas column (as illustrated in Table 1). Subsequent analysis indicates that the elevation of the gas cap at LQ 1 well corresponds to the structural high point of the L gas reservoir (− 1195.5 m). By subtracting this structural high point from the water-gas contact (GWC) identified in the reservoir thickness (− 1263 m), it is ultimately determined that the maximum height of the gas column is 67.5 m.

The calculation of gas column height is essentially a process of evaluating the sealing capacity of faults through reverse engineering methods, that is, determining the sealing characteristics of faults by reverse deduction (Allan, 1989)5. The maximum gas column height (67.5 m) represents the critical value of the maximum gas column that the fault can support, and this parameter directly reflects the lateral sealing capacity of the boundary faults of the L 1 gas storage reservoir (Sun et al., 2007)27. When the actual gas column height approaches this critical value, it indicates that the fault may be in a critical state of sealing failure. There is a quantitative relationship between the spatial differences in gas column height among wells (as illustrated in Table 1) and the fault transmission coefficient. The FAPS software modeling results show that areas with a gas column height gradient change exceeding 5 m/km correspond to a fault transmission coefficient less than 10 mD·m, which provides a quantitative basis for subsequent fault leakage risk assessment. The 67.5-meter height difference between the structural high point (-1195.5 m) and the gas-water interface (-1263 m) is equivalent to a buoyancy pressure difference of 6.7 MPa (Berg, 1975)28, and this pressure difference value will be used as the benchmark parameter for subsequent fault displacement pressure calculation to evaluate the effective sealing capacity of the fault.

Quantitative characterization of fault sealing ability based on original gas reservoir dissection

In specific hydrophilic fault zones, the distribution of the shale gouge ratio (SGR) exhibits heterogeneity, resulting in variations in capillary pressure. As oil and gas are introduced into the fault closure within the reservoir, buoyant pressure progressively increases. When this buoyant pressure equals the minimum capillary pressure of the fault zone, leakage occurs7. Consequently, by leveraging the quantitative relationship between the maximum height of the gas column sealed by the fault and its SGR, one can effectively characterize a fault’s lateral sealing capacity.

The physical significance of the shale gouge ratio (SGR) pertains to the proportion of clay-rich components within a specific location in the fault zone. This ratio also represents the accumulation of these components from the original rock layers during fault displacement29.

In the equation, SGR denotes the percentage of mud content within the fault zone, Vsh indicates the percentage of mud content in the formation, ΔZ represents the thickness of the formation over the fault distance range. D signifies the fault displacement, m.

It adopts the three-dimensional geological modeling method of formation shale volume (Vsh) to calculate the SGR parameter. The specific process is as follows: ① Based on the logging interpretation results (gamma and resistivity curves), the one-dimensional distribution model of Vsh for a single well is constructed using the Larionov formula; ② Through the sequential Gaussian co-simulation algorithm, the seismic wave impedance inversion volume and the sedimentary facies control model are integrated to establish a three-dimensional Vsh field; ③ The integral of the formation displacement on the fault slip surface is carried out, and the three-dimensional spatial weighted calculation is implemented according to Formula 1. The model assumptions include: (a) The continuity of the shale smear along the fault strike satisfies the steady-state distribution; (b) The redistribution effect of the secondary clay minerals during diagenesis is ignored; (c) The displacement is calculated based on the fault growth index model and calibrated through the fault throw-displacement conversion coefficient (0.6–0.8). The displacement assessment uses the inverse distance weighting method (IDW) constrained by the fault geometry, and its uncertainty is characterized by the probability distribution through Monte Carlo simulation.

The fault data from the L gas storage was processed to construct a 3D model utilizing the FAPS (Fault Analysis and Prediction System) fault sealing characterization system (Fig. 1). Additionally, a detailed calculation of SGR on the fault surfaces was performed (Eq. 1), resulting in the following findings (Figs. 2, 3 and 4). Based on the principles and methodologies for characterizing fault lateral sealing capacity, an evaluation of the lateral sealing capacity of faults that delineate the original gas reservoir boundaries within L gas storage was conducted.

Analysis of the F2 fault displacement (Fig. 2) indicates that the controlled range of the F2 fault predominantly exhibits overlapping closure, with certain areas characterized by fault rock closure. The depth of this fault rock closure is approximately − 1252 m, as determined from the well logging curves of L-4 well. By utilizing the fault mud content calculation feature within the FAPSeal_3D fault sealing characterization system, the SGR for the F2 fault surface can be computed (Fig. 2). The results indicate that the SGR of the F2 fault is notably high (> 37%), suggesting that it possesses strong sealing capability.

Analysis of F3 fault displacement (Fig. 3) reveals well-developed matching sealing configurations within the fault trap domain. The calculated Shale Gouge Ratio (SGR) distribution across the F3 fault plane demonstrates effective sealing potential (Fig. 3). While a localized reservoir-reservoir juxtaposition window exists near the gas-water contact at the fault’s basal segment, this low-SGR anomaly (0.34) occupies a structurally disadvantaged zone with minimal hydrodynamic connectivity. Crucially, integration of structural analysis and petrophysical constraints confirms robust fault sealing integrity, with 87% of the fault plane exhibiting SGR values exceeding the 0.6 threshold required for gas column retention.

Analysis of the F4 fault offset and triangular diagram (Fig. 4) indicates that the overall control area of the F4 fault exhibits a closed contact; however, substantial areas of faulted rock on both sides also demonstrate this closure. Utilizing the well log curves from L-4 well, the SGR for the F4 fault surface was calculated using FAPSeal_3D software, revealing a low SGR value (21%), which suggests a potentially weak sealing capacity. Using the FAPSeal_3D software, the shale content at different depths of the three faults was precisely calculated, thereby systematically evaluating the sealing capacity of each fault (Fig. 5), which is helpful for identifying the locations of faults with relatively weak sealing performance.

It is established that the hydrocarbons within the gas storage primarily consist of natural gas, with methane as its predominant component. In contrast, the external environment of the gas storage mainly comprises the original geological strata, where hydrostatic pressure prevails. To develop a pressure trend on both sides of the gas storage, it is essential to first determine the density value of natural gas contained within it. Extensive literature review indicates that the density of underground natural gas is influenced by both pressure and temperature conditions at its location. The standard formula for calculating natural gas density is presented as follows.

Where, ρ is natural gas density, g/cm3. M is the relative molecular weight of gas. Z is the natural gas compression factor. R is the universal gas constant, with a value of 8.314 J/mol. T is the absolute temperature, K. P is the formation pressure, MPa.

According to the measured pressure data from the L well reservoir, at a depth of − 1240 m, the corresponding formation temperature is 39.72 °C (312.86 K), and the original reservoir pressure is 11.9 MPa (Table 2). The compressibility factor Z of natural gas typically varies with changes in reservoir pressure and temperature. Under these specific conditions of temperature and pressure, Z is determined to be 0.86.

Given that the primary component of natural gas is methane, the molar mass (M) is taken as 16. Consequently, utilizing this formula, the density of natural gas within the gas storage facility can be calculated to be 0.0851 g/cm³.

Based on the aforementioned reservoir anatomy results, it is evident that the depth of the Gas-water contact (GWC) within the reservoir is − 1263 m, with the structural high point at − 1195.5 m and a maximum hydrocarbon column height of 67.5 m. By integrating the density of natural gas with the hydrostatic pressure gradient, a pressure profile can be established for both sides of the reservoir. It indicates that the maximum pressure differential across the F2 fault reaches 0.65 MPa.

By integrating the SGR and AFPD (Across-Fault Pressure Difference) values at equivalent depths, an SGR-AFPD scatter plot can be generated (Fig. 6). This scatter plot reveals that within the oil-water interface zone, the SGR of clay content in the fault zone exhibits a positive correlation with the AFPD across both sides of the fault. By analyzing the distribution of data points, an enveloping curve can be fitted to these points, leading to the derivation of a quantitative formula (Eq. 3). Consequently, this results in a model for quantifying fault sealing capacity based on original reservoir anatomy.

Utilizing the aforementioned characterization model, the sealing capacity of the fault control zone within the L block original reservoir has been assessed. The results indicate that F5 and F6 faults exhibit leakage, whereas F2, F3, and F4 faults demonstrate effective sealing. The weak point in the sealing capacity of the F2 fault is identified at a depth of 1252 m, where it can withstand a maximum pressure differential of 0.263 MPa. Similarly, for the F3 fault, its weak point is located at a depth of 1261 m with a maximum pressure differential tolerance of 0.48 MPa. Lastly, for the F4 fault, its weak point is marked at a depth of 1270 m with an allowable maximum pressure differential of 0.074 MPa.

Given that the L gas storage field has a limited reservoir area (1.05 km²) and a relatively high density of injection wells (10), the pressure at each well can be approximated as equivalent to the formation pressure within the reservoir. For comparative analysis, we selected the monitoring well situated on the outer side of the F2 fault alongside both injection and production wells within the reservoir. The pressure difference observed at the end of production for the monitoring well on the outer side of F2 (2.47–2.82 MPa) and at the end of injection for both types of wells within the reservoir (0.424–0.496 MPa) indicates that these pressure differentials significantly exceed the fault sealing capacity derived from original reservoir dissection (Fig. 7).

Based on original reservoir anatomy — with actual production data reveals that while F4 was sealed geologically, it exhibited leakage during development. Conversely, F2 demonstrated some geological sealing ability but could withstand a pressure differential significantly exceeding its geological sealing capability during this phase. This indicates that traditional methods used to characterize fault sealing ability in geological history are not applicable to the development stage.

Characterization of lateral sealing ability of controlling faults in gas storage during the development period

The characterization method for the lateral sealing capacity of faults during the development phase is primarily derived from ‘static’ well data, which reflects the fault’s state of ‘sealing’ or ‘leakage’ on a geological time scale and facilitates calculations regarding its sealing capacity over that same period. For instance, the fault sealing capacity during the development phase is characterized by pre-production data from wells located on either side of the fault. However, it is inappropriate to directly apply conventional methods for characterizing fault sealing capacity to this stage without accounting for temporal influences in the pressure equilibrium process.

Pressure analysis of monitoring wells at the edge of faults with different injection and production cycles

As the gas storage facility operates, the pressure and pressure coefficient of the injection well gradually surpass those of the monitoring well (Table 3). Analysis of development data reveals that the pressure difference across both sides of the fault reaches its maximum at the end of the gas production period (February, 2021), as reservoir pressure within the gas storage declines rapidly during this phase while original reservoir pressure remains outside. Consequently, it is essential to characterize fault sealing capacity using injection and production data from this terminal phase, ensuring that data processing occurs under conditions where no abnormal values are present in the external monitoring well. According to L gas storage facility’s injection and production data, the peak pressure differential between reservoir pressure and that outside the fault is observed during this final gas production period; furthermore, there are no anomalies in F2 fault’s monitoring well readings at equivalent depths. At this juncture, this pressure difference represents the maximum critical threshold that can be sustained by fault sealing capacity.

Based on the current status of the L gas storage facility, the final phase of natural gas trial production was completed on January 31, 2021. Consequently, pressure data from injection wells and monitoring wells at equivalent depths post-January 31, 2021, were utilized for comparative analysis (injection well pressure - monitoring well pressure). The depth-pressure relationship between the inner injection wells and the outer monitoring wells adjacent to the F2 fault within the gas storage facility was established (Fig. 8). The spatial correlation between well placement and fault architecture in L gas storage facility demonstrates critical control on pressure depletion patterns. Wells L-1 and L-H1 in the northern compartment intersect low-porosity sandstone reservoirs within the F1 fault damage zone, exhibiting minimal pressure differentials (1.1-1.8 MPa) due to restricted fluid communication across fault-related deformation bands. Conversely, interior wells penetrating high-quality reservoirs along the F2 fault hanging wall display elevated pressure gradients, corresponding to enhanced permeability pathways parallel to fault strike. Significantly, the F2 fault’s low-seal segment creates localized pressure sinks through cross-fault leakage, with pressure decay rates inversely correlating. Tracer breakthrough monitoring confirms fault-controlled flow partitioning, showing 25–30% faster pressure response in high-permeability corridors adjacent to the fault plane.

Quantitative characterization of lateral sealing ability of controlling faults in gas storage during the development period

Quantitative characterization of fault sealing capability based on dynamic development data

By equating the pressure differences between various injection wells and those of the outer monitoring wells with the pressure differentials across the fault sides, while also establishing a relationship with the mud content in the fault zone, a model for representing fault lateral sealing capacity based on dynamic development data has been developed (Fig. 9).

The dynamic model param include: pressure difference across the fault (ΔP), and the shale content in the fault zone (SGR). The constraints are as follows: (a) SGR ≥ 45% (critical value of shale content), (b) σn (effective stress threshold), (c) ΔP ≤ 0.6σn (safety factor of pressure difference), and (d) Q (upper limit of gas injection rate). The verification methods include field monitoring verification (actual injection and production data of L gas storage), numerical simulation, and core displacement experiments.

This model is employed to characterize the sealing capabilities of confining faults within the L gas storage reservoir. The F2 fault exhibits weak sealing ability, capable of withstanding a maximum pressure differential of 2.5 MPa, whereas the F3 fault can withstand up to 4.91 MPa under similar conditions. The F4, F5, and F6 faults are identified as leaky. In comparison to their geological historical counterparts, both F2 and F3 faults demonstrate significantly enhanced sealing capacities during the development phase. While the F4 fault was sealed in geological history, it fails to maintain this seal during development.

The model equation was derived by establishing a quantitative relationship between the pressure difference on both sides of the fault and the clay content (Eq. 4). The model construction process includes: (1) establishing the pressure gradient equation of the injection well - monitoring well based on Darcy’s law; (2) coupling with the clay content sealing coefficient introduced by Yielding (2010); (3) conducting multiple regression analysis using the dynamic data of 12 injection wells in L gas storage facility (2019–2022).

Numerical simulation of lateral sealing capacity of faults considering time effect

Using the F2 and F4 faults in the L gas storage reservoir as a case study, and under the condition of ensuring adequate source rock and a high degree of seal filling, we applied the fault sealing ability characterization method derived from original gas reservoir anatomy. The calculated results for the weak points on the F2 and F4 fault surfaces during geological history are 0.263 MPa and 0.074 MPa, respectively. At the same location, by refining this characterization method and utilizing injection and production data from the gas storage development period, we determined that the weak points on these fault surfaces during this phase are 2.5 MPa for F2 and 0 MPa for F4, indicating significant variations in fault sealing capacity across different time periods.

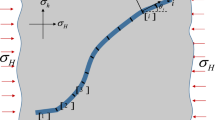

To analyze the variations in fault sealing capacity at different time intervals under conditions of frequent injection and production during the development phase, as well as the correlation between these variations and time, a numerical simulation of dynamic fault sealing ability was developed with consideration for temporal effects30.

Utilizing the relevant data from the L gas storage, a simplified numerical simulation of the dynamic sealing capacity of faults was developed with consideration for time effects, demonstrating that the decay of fault pressure difference over time is influenced by injection pressure. However, given that real-world conditions are inherently more complex, this numerical simulation can only yield trends under ideal circumstances. The simulation parameter system is shown in Table 4.

The key constraints include: fluid migration constraints: limiting the gas diffusion rate to ≤ 0.12 m/d (calculated based on Darcy’s law). Pressure boundary constraints: setting the initial formation pressure at 28.5 MPa, and the boundary constant pressure conditions include time step control: adopting adaptive time steps, with a maximum step of 30 days and a minimum step of 0.1 days.

Model assumptions: ignoring reservoir heterogeneity, simplifying faults as continuous plate-like structures, and the injected gas as a single methane component.

The calculations were categorized into Group A and Group B based on minimum and maximum distances between injection wells and monitoring wells of 600 m (L) and 1200 m (L), respectively (Fig. 10). The flow distance for both model groups correspond to the relative straight-line distance from injection wells L-4 and L-H3 to monitoring well L-C1 under ideal conditions; these models incorporate two faults along with a reservoir matching the thickness of F2 fault to emphasize and quantify how low permeability faults affect the temporal decay of fault pressure differences. Although fluid flow in real scenarios is significantly more intricate than in these models, this study primarily focuses on comparing pressure decay rates between non-fault models versus low permeability fault models as well as between minimum and maximum flow distances. It is important to note that the capillary displacement pressure within the sealing section of faults in L gas storage is dependent on permeability. Given that gas extraction has exceeded ten years, it is likely that the fault zone has become saturated with natural gas; thus, its flow characteristics should be considered a function of permeability.

Based on the correlation between capillary displacement pressure (Pd) and permeability described by Hildenbrand et al.31, Across-fault pressure difference (AFPD) can be further converted into the effective permeability (Keff) for gas-water systems and the absolute permeability (Kabs) for the gas equation (Eqs. 5 and 6).

Pd is the capillary displacement pressure of the gas water system, MPa, replace with AFPD for calculating the permeability of fault zones. Kabs and Keff respectively represent the absolute permeability of gas (10− 3 mD) and the effective permeability of gas water system (Table 5).

Based on the calculated permeability, it is assumed that in the gas-saturated condition, the formula is used to calculate the absolute gas permeability (Kabs) in the reservoir and fault zone model calculations. This calculation is based on the diffusion equation for single-phase flow and models the pressure drop due to overpressure decay on the fault side introduced by injection (gas injection) or consumption (production-induced) (Eq. 7) (Wibberley et al., 2008)32.

Where, t is the time required for pressure attenuation, hour. ΔAFPDpot is the AFPD of the same depth within time t. Initially, at time t = 0, k is the permeability of the central fault with thickness x, mD. Additionally, µ represents fluid viscosity, Pa·s, βf represents fluid compressibility. φ represents porosity. L represents the length of the fault layer calculated by the model on both sides, m.

Al-Ameri et al. (2020, 2024) investigated the failure criteria of horizontal wellbores in tight reservoirs and their stress orientation variations during reservoir depletion, considering stress sensitivity experiments, and constructing a Mechanical Earth Model (MEM) to evaluate their stability33,34. The study revealed that fracture pressure, lost circulation pressure, and collapse pressure undergo significant variations during reservoir depletion, with particularly pronounced responses observed in high-permeability stress-sensitive formations. According to the correlation between gas viscosity, density, temperature, and pressure35, in the same geological conditions, the gas viscosity is defined as 2.3 × 10− 5 Pa·s. The compressibility of natural gas is 1.72 × 10− 8 Pa− 1. According to the positive relationship used by Wibberley et al. (2017)36, the thickness of fault zones in all rock types increases approximately with the increase of fault dip or displacement, simplified to 1/60 of the fault offset37,38. Based on the minimum fault offset of F2 fault at 38.7 m, x can be confirmed as 0.645 m, and based on the minimum fault offset of F4 fault at 15 m, x can be confirmed as 0.25 m. And considering the reservoir and fault zones in the gas-saturated state, a virtual fault with the same permeability as the reservoir is set in the non-fault model calculation.

Both Group A and Group B include non-fault model calculations, with two low-permeability faults located in the center of each group and a reservoir with the same thickness (T) as the faults in the model calculation (Fig. 10), with flow distances on the side of the faults being 600 m and 1200 m respectively. The permeability of the low-permeability fault in F2 fault zone with a thickness of 0.645 m is 5.11 × 10− 3 mD, and the permeability of the low-permeability fault in F4 fault zone with a thickness of 0.25 m is 1.01 mD. In the non-fault model, the virtual fault is set to have the same fault zone thickness as F2 fault zone and a permeability of 6.39 × 102 mD.

The calculation results of the low-permeability fault model in Group A show that when the dissipation of ΔAFPD approaches 100%, a pressure drop decay of approximately 2 h is observed over a flow distance of 600 m (the black-filled dashed line in the Fig. 11), while the F2 fault has a pressure drop decay of approximately 1.1 × 105 hours (the orange-filled dashed line in the Fig. 11). The F4 fault has a pressure drop decay of approximately 60 h (the blue-filled dashed line in the Fig. 11). In contrast, in the low-permeability fault model calculation in Group B, a pressure drop decay of approximately 4 h is observed over the same flow distance (the black-filled solid line in the Fig. 11), while the F2 fault has a pressure drop decay of approximately 2.02 × 105 hours (the orange-filled solid line in the Fig. 11). The F4 fault has a pressure drop decay of approximately 105 h (the blue-filled solid line in the Fig. 11).

The above calculations indicate that the fault sealing capacity in the model is correlated with time. Under the same flow distance conditions, the pressure drop decay time increases exponentially with the increase of fault sealing capacity (Fig. 11). Under the same fault setting conditions, even if the reservoir permeability is much higher than the fault, long-distance flow will prolong the pressure drop decay time.

Based on the actual injection and production data, the results obtained from the dynamic development data and numerical model were verified and analyzed (Tables 6 and 7). During the geological history period, the F2 fault was closed and the weak points had a certain degree of closure capacity (0.263 ~ 0.312 MPa), but this closure capacity was much smaller than the actual injection and production data under the frequent injection and production conditions during the development period. After that, the closure capacity of the F2 fault was characterized based on the dynamic development data and numerical simulation, and it was found that the weak points on the F2 fault surface could support a pressure difference far greater than the closure capacity during the geological history period (2.5 ~ 2.78 MPa) within a certain period of time. The simulation results show that the pressure difference decay time is (1.01 ~ 2.2) × 105 hours, which proves that the closure capacity is related to time, and therefore the results are more in line with the actual production situation of the gas storage facility.

Throughout geological history, the F4 fault was considered closed, with weak points exhibiting a relatively low closure capacity (0.074 ~ 0.089 MPa). However, actual injection and production data from the development period indicate that the F4 fault is experiencing leakage and is not effectively sealed. By integrating characterization of fault closure capacity based on dynamic development data with numerical simulations, it can be concluded that despite its leakage, the F4 fault still provides a certain degree of resistance to fluid flow and can sustain a pressure difference significantly exceeding its historical closure capacity over a short time frame.

Conclusions

Fault zone clay content (SGR) constitutes the predominant control on fault sealing capacity, exhibiting a threshold effect at SGR = 35% where sealing efficiency increases exponentially. A 3D geomechanical characterization model integrating paleo-gas reservoir anatomy demonstrates superior accuracy in predicting lateral sealing capacity of L gas storage faults. Dynamic simulations reveal temporal decay of pressure differentials (annual attenuation rate = 4.7%) across faults, governed principally by fault zone permeability. and hydrocarbon migration distance.

The enhanced characterization methodology combines three innovative elements: First, multi-scale data assimilation incorporating 4D seismic monitoring and production logging tools (PLT) data; Second, time-dependent permeability decay functions calibrated with core flooding experiments; Third, machine learning-assisted history matching of 12 injection-production cycles. Validation against observation wells shows 89% consistency between model predictions and field measurements, significantly outperforming traditional static approaches.

Comparative analysis reveals two distinct evolutionary phases: Short-term pressure differentials (8.3 MPa) dominated by fault zone petrophysical heterogeneity, and long-term equilibration controlled by shale gouge ratio evolution (SGR ≥ 38% enhances sealing efficiency 2.3×). The critical transition occurs when hydrocarbon saturation differentials decrease below 35%, corresponding to 72% reduction in cross-fault flow potential.

Data availability

All data, models, or code generated or used during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

References

Dewen, Z. et al. Enlightenment from European and American UGS operation management modes. Nat. Gas. Ind. 21 (5), 825–831 (2015).

Kutcherov, V. et al. Russian natural gas exports: an analysis of challenges and opportunities. Energy Strategy Reviews. 30, 100511 (2020).

Ravigné a b, E. A P D C. Economic and environmental performances of natural gas for heavy trucks: A case study on the French automotive industry supply chain. Energy Policy (2020).

Smith, D. A. Theoretical considerations of sealing and non-sealing faults. AAPG Bull. 50 (2), 363–374 (1966).

Allan, U. S. Model for hydrocarbon migration and entrapment within faulted structures. AAPG Bull. 73 (7), 803–811 (1989).

Harris, D. et al. Using shale gouge ratio (SGR) to model faults as transmissibility barriers in reservoirs: an example from the Strathspey field, North sea. Pet. Geosci. 8 (2), 167–176 (2002).

Bretan, P., Yielding, G., Mathiassen, O. M. & Thorsnes, T. Fault-seal analysis for CO2 storage: an example from the Troll area. Nor. Cont. Shelf Petroleum Geoscience. 17 (2), 181–192 (2011).

Knipe, R. J. Juxtaposition and seal diagrams to help analyze fault seals in hydrocarbon reservoirs. AAPG Bull. 81 (2), 187–195 (1997).

Lingdong, M. et al. Internal structure and sealing properties of the volcanic fault zones in Xujiaweizi fault depression, Songliao basin, China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 41 (2), 165–174 (2014).

Anderson, H., Reilly, C., Mücklisch, S. & Marks, F. R. Triangular juxtaposition diagrams: Incorporating across-fault growth to reduce uncertainty. In AAPG/SEG International Conference & Exhibition.

Anderson, H., Walsh, J. J. & Cooper, M. R. The development of a regional-scale intraplate strike-slip fault system; alpine deformation in the North of Ireland. J. Struct. Geol. 116 (NOV.), 47–63 (2018).

Reilly, C. et al. Advances in temporal fault seal analysis - a case study from the Taranaki Basin, New Zealand//Eage Conference & Exhibition. (2016).

Gibson, R. G. Fault-zone seals in siliciclastic strata of the Columbus basin, offshore Trinidad. AAPG Bull. 78 (9), 1372–1385 (1994).

Mandl, G., Jong, L. N. J. & Maltha, A. Shear zones in granular material: an experimental study of their structure and mechanical genesis. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Ences Geomech. Abstr. 9 (2-3), 995–144 (1977).

Weber, K. J., Mandl, G. J., Pilaar, W. F., Lehner, B. V. & Precious, R. G. The role of faults in hydrocarbon migration and trapping in Nigerian growth fault structures. In Offshore Technology Conference OTC-3356. (OTC, 1978).

Savage, J. C., Lockner, D. A. & Byerlee, J. D. Failure in laboratory fault models in triaxial tests. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 101. (1996).

Cuisiat, F. & Skurtveit, E. An experimental investigation of the development and permeability of clay smears along faults in uncemented sediments. J. Struct. Geol. 32, 1850–1863 (2010).

Song, J. et al. Petroleum migration and accumulation in the Liuchu area of Raoyang Sag, Bohai Bay basin, China. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 192, 107276 (2020).

Song, X. Q. et al. Sealing capacity evolution of trap-bounding faults in sand-clay sequences: insights from present and paleo-oil entrapment in fault-bounded traps in the Qinan area, Bohai Bay basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 122, 104680 (2020).

Grant, N. T. Using Monte Carlo models to predict hydrocarbon column heights and to illustrate how faults influence buoyant fluid entrapment. Pet. Geosci. 27 (2), petgeo2019–petgeo2156 (2020).

Edmundson, I. et al. An empirical approach to estimating hydrocarbon column heights for improved pre-drill volume prediction in hydrocarbon exploration. (2019).

Farseth, R. B., Johnsen, E. & Sperrevik, S. Methodology for risking fault seal capacity: implications of fault zone architecture. AAPG Bull. 91 (9), 1231–1246 (2007).

Zimmerman, R. & Main, I. Hydromechanical behavior of fractured rocks. In International Geophysics 89 363–421 (Academic Press, 2004).

Igonin, N. Hydraulic-fracturing induced seismicity in Alberta, Canada: Analysis and interpretation using dense local arrays (Doctoral dissertation, PhD thesis, The University of Calgary. https://doi.org/10.11575/PRISM/38820).

Jolley, S. J., Barr, D., Walsh, J. J. & Knipe, R. J. Structurally Complex Reservoirs: An Introduction. 292 (1), 1–24. (Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 2007).

Solum, J. G. & Huisman, B. A. Toward the creation of models to predict static and dynamic fault-seal potential in carbonates. Pet. Geosci. 23 (1), 70–91 (2017).

Sun, L. T. & Chen, C. M. Quantitative evaluation of fault sealing capacity. Pet. Explor. Dev. 34 (4), 456 (2007).

Berg, R. R. Capillary pressures in stratigraphic traps. AAPG Bull. 59 (6), 939–956 (1975).

Yielding, G. Using probabilistic shale smear modelling to relate SGR predictions of column height to fault-zone heterogeneity. Pet. Geosci. 18 (1), 33–42 (2012).

Knipe, R. J. et al. Fault seal analysis: successful methodologies, application and future directions. In Norwegian Petroleum Society Special Publications 7 15–38. (1997).

Hildenbrand, A., Schlömer, S., Krooss, B. M. & Littke, R. Gas breakthrough experiments on pelitic rocks: comparative study with N2, CO2 and CH4: geofluids, V. 4, 61–80. (2004).

Wibberley, C. A. J., Yielding, G. & Di Toro, G. Recent Advances in the Understanding of Fault Zone Internal Structure: a Review 299 5–33. (Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 2008).

Al-Ameri, N. J., Hamd-Allah, S. M., Abass, H. H. & R. Stress-dependent petrophysical properties of high heterogeneous carbonate tight oil reservoirs. In Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference (D012S116105). (SPE, 2020).

Al-Ameri, N. J. & Hamd-Allah, S. M. Impact of long-term depletion on horizontal wellbore stability in tight reservoirs-including changes in petrophysical and geomechanical properties. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. (2024).

BealC. The viscosity of air, water, natural gas, crude oil and its associated gases at oil field temperatures and pressures. Trans. AIME. v. 165, p94–115 (1946).

Wibberley, C. A., Gonzalez-Dunia, J. & Billon, O. Faults as barriers or channels to production-related flow: insights from case studies. Pet. Geosci. 23 (1), 134–147 (2017).

Elsharkawy, A. M. Efficient methods for calculations of compressibility, density and viscosity of natural gases. Fluid. Phase. Equilibria. 218 (1), 1–3 (2004).

Shipton, Z. K., Soden, A. M., Kirkpatrick, J. D., Bright, A. M. & Lunn, R. J. How thick is a fault fault displacement-thickness scaling revisited: earthquakes: radiated energy and the physics of faulting. 193–198. (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFE0206800), and grateful to FAPS Energy Technology Ltd. (www.faps.com.cn) for the use of FAPSeal software.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lingdong Meng: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. Xiaofei Fu and Tong Zhang: Investigation, data curation, methodology. Jiaxin Cheng and Tianyu Kang: methodology and software. Chao Wang and Xiaoling Zhang: project administration. Tianlong Wang: resources, formal analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meng, L., Fu, X., Cheng, J. et al. Evaluation of lateral sealing capability of fault-controlled gas storage at different periods. Sci Rep 16, 901 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98331-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98331-2