Abstract

Electroencephalography (EEG) is one of the most used techniques to perform diagnosis of epilepsy. However, manual annotation of seizures in EEG data is a major time-consuming step in the analysis process of EEGs. Different machine learning models have been developed to perform automated detection of seizures from EEGs. However, a large gap is observed between initial accuracies and those observed in clinical practice. In this work, we reproduced and assessed the accuracy of a large number of models, including deep learning networks, for detection of seizures from EEGs. Benchmarking included three different datasets for training and initial testing, and a manually annotated EEG from a local patient for further testing. Random forest and a convolutional neural network achieved the best results on public data, but a large reduction of accuracy was observed testing with the local data, especially for the neural network. We expect that the retrained models and the data available in this work will contribute to the integration of machine learning techniques as tools to improve the accuracy of diagnosis in clinical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the World Health organization (WHO) epilepsy is defined as a chronic neurological, non-transmissible, disease usually characterized by recurring seizures, consisting of episodes of involuntary movement of the whole body or specific parts1. These seizures occur in the brain when there are neuronal networks irregularly formed or perturbed by different conditions, mainly causing an abnormal synchronization in signaling processes2. Excessive electrical discharges can materialize in different regions of the brain causing a great variety of other symptoms. The development of a seizure is determined by the localization of the first perturbation and by the way it spreads through the brain. Depending on this behavior it can be classified as focal or generalized seizure or of unknown onset when there is not enough data to classify in any category3. Focal epilepsy originates in one hemisphere, while generalized epilepsy can begin throughout both hemispheres of the brain4. Some of the most common symptoms are loss of awareness or consciousness, erratic movement, disturbances in sensation (vision, hearing and taste), mood and different cognitive functionalities5. Approximately 50 million people worldwide live with epilepsy1. Therefore, it is essential to advance the diagnosis and management of this condition. This involves investigating methods to improve the accuracy and efficiency of epilepsy diagnosis.

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a non-invasive neuroimaging technique widely used in the diagnosis and management of epilepsy6. EEG recordings capture electrical activity in the brain, providing information on brain function. An efficient diagnosis using this methodology depends on factors related to the different guidelines for signal extraction and processing, considering the great variety of devices and methodologies used with this purpose7. In particular, seizures are characterized by abnormal electrical discharges in the brain, which manifest as distinct patterns in EEG traces8. By analyzing EEG data, physicians can identify seizure activity, localize epileptic foci, and plan treatment strategies accordingly. Different studies of EEG properties have identified elements to characterize several epilepsy syndromes. EEG examinations usually consist of recordings longer than 5 h, which implies that they are of a large magnitude and that their manual analysis can take long periods of time.

Methods for automatic detection of seizures in EEG exams have been widely studied with a trend in recent years towards deep learning algorithms. By training on manually labeled EEG datasets, machine learning models can learn to differentiate between seizure and non-seizure EEG segments9. The application of machine learning in EEG exams offers the potential to enhance the efficiency and objectivity of seizure detection, facilitating the diagnosis of patients. Machine learning models are characterized by the prior calculation of different features associated with EEGs that can be representative for each type of segment. Several studies have used different approaches based on biomedical signal processing like statistics, time and frequency domain elements and their combination9. After feature calculation, models are trained using classical machine learning algorithms like Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), K-nearest neighbors (KNN) and Naive-Bayes classifier. Following this strategy several models have been reported with good results. To mention a few, the combination of time-domain frequency features combined with an RF classifier obtained an accuracy of 93.8% on the EPILEPSIAE database10. In another case, using the discrete wavelet transform and an SVM classifier, a value of 94.8% was achieved using the CHB-MIT database11. A large variety of models have been published with reported accuracy above 90%9. However, most of them are trained and tested on a single database.

Strategies based on deep learning have become increasingly popular in recent years. With the implementation of neural network architectures with multiple layers, deep learning models can automatically learn relevant features from raw EEG data, without the need for feature calculation12. Models such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), or hybrid architectures may be trained on labeled EEG data to learn discriminative features associated with seizure events12. These models are then fine-tuned and evaluated to assess their performance in detecting seizures. In the literature, CNN models can be found with reported accuracies between 90% and 100%12. The same is true for models with RNNs and Autoencoder architectures. The supplementary Table 1 shows different articles presenting these results.

This manuscript presents the main results of a collaborative work with the epilepsy department of Fundacion Hospital Pediatrico de la Misericordia (HOMI), to investigate if current models for automated detection of seizures can be integrated in the analysis of EEGs generated by the hospital. To this end, different public EEG databases were used to train machine learning models using features and classification algorithms reported in the literature. Additionally, these databases were used to retrain previously reported DL models. The models showing best classification performance on public datasets were tested on an EEG manually annotated at the hospital for diagnosis of an epilepsy patient.

Methods

Data for evaluation of machine learning models

Three public databases were used for model training. CHB-MIT, a joint work between the Boston Children’s Hospital and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the epilepsy monitoring unit of the medical center at the American University of Beirut (AUB), and data from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of the Helsinki University Hospital. One manually annotated sample from a patient at HOMI was used to perform testing of the developed models. Table 1, shows a general description of each database. Sample specific information is available in the Supplementary Table 2.

The HOMI sample was obtained from a pediatric (13 year old) male patient at HOMI, through a collaborative project among the institutions involved in this manuscript. The project was approved by the research ethics committee at HOMI, as evidenced by the minute 49 − 21 of the meeting held on June 1st of 2021. The EEG was obtained as part of the prescribed examination procedure for the patient and following all applicable guidelines and regulations. Legal representatives of the patient signed an informed consent for research purposes and data were anonymized to avoid identification of the patient from the EEG data.

The four databases have specific annotations for epileptic seizures, marking the beginning and end of each event. These annotations have been made independently by medical experts from the centers that released each database. The annotations are intended for use in seizure detection studies. While the NICU and AUB databases have monopolar montages, the CHB-MIT has a bipolar montage. Despite this and the difference in the number of channels, for all data it is possible to obtain the information to represent a 10–20 montage of 18 channels (details below). The additional channels correspond to electrocardiography and additional study elements that were not taken into account in the development of the machine learning models.

Initial data processing

Data preprocessing was conducted to ensure comparability between heterogeneous datasets. An extensive description of this process is available in the Supplementary file 1. The first step was filtering for each data file, enforcing a 0.5 Hz high-pass filter and a 70 Hz low-pass filter. To take into account the possible noise caused by the electronic system, a 50 Hz notch filter was applied for AUC and NICU databases and 60 Hz for CHB-MIT and HOMI files. Additionally, the information of the channels was arranged to obtain bipolar assemblies and a subsampling was performed to have all the EEG exams at a sampling frequency of 256 Hz. To generate individual units for binary classification, the scans were divided into 5 s fragments. These values were chosen because epileptic seizures can be found in the range 4 s17. The 5 s fragments were classified as Seizure and No Seizure according to the available annotation for each dataset. After EEG preprocessing, data sets were obtained from the information of all exams. Due to the nature of the EEG exam, the amount of data for the seizure-free class was larger than the amount for the seizure class. Hence, we randomly sampled a subset of seizure free elements to have a balanced dataset. This resulted in 19,044 five second elements, half with seizure and the other half seizure-free.

Feature calculation

A set of 8 common feature categories, adding to a total of 1998 single features, were calculated over the dataset obtained after preprocessing in order to be used as data for training and testing different classic machine learning models. The selection of these features was performed taking into account EEG signal properties and features used for previous models reported in the literature. The calculated features are grouped in eight different sets, listed below. These are summary statistics (Stats), which include mean, median, standard deviation, variance, kurtosis, skewness, Time domain (TimeD) conformed by energy, entropy, activity, mobility and complexity, energy after fourier transform (FouTE), energy of power bands after fourier transform (PBand), wavelets transform, coherence, comparison of amplitudes (CompA) and comparison of frequencies (CompF). The features were concatenated to obtain a global set of features denominated All in the results.

Experimental design, training and testing

In this case, we tried to classify five-second regions of the EEG between seizure and seizure-free categories. This represents a binary classification problem. The balanced dataset obtained after the initial data processing stage was divided using 90% for training of the different models and 10% left out for testing with data not observed during the training processes. A 10% of the training subset was used for early validation and parameter tuning. The classification models were evaluated by calculating the F-score and by building receiving operator characteristic (ROC) curves from the results of the classification of the unobserved 10% subset used for testing.

Six classical machine learning algorithms were trained on the subset including 90% of the AUB, NICU and CHB-MIT datasets: Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest Classifier (RFC), Stochastic Gradient Descent Classifier (SGD), Decision Tree Classifier (DTC), K-Nearest Neighbors Classifier (KNN) and Naïve Bayes Classifier (NBC). Each of these models, with their default values, was trained with the all features subsets individually and the combined features of the training data using 5-fold cross-correlation and evaluated over validation dataset with the accuracy metric. For the algorithm with the best result for each experiment, gridsearch was applied to find the combination of hyperparameters to get the best result.

Six different neural network architectures found in literature were used to perform a featureless image-based classification task: A full convolution neural network (FCN)18, two different convolutional neural networks (CNN1 and CNN3)19,20, an Autoencoder-Recurrent neural network (2D-DCAE + Bi-LSTM)21, a neural network with convolutional and recurrent layers (ConvLSTM)22, and a Deep Convolutional neural network (DCNN)23. The input for these models was the dataset obtained after preprocessing. Additionally, for training, the number of layers and hyperparameters values were taken from the best model reported in the original publication. Dimensional values were changed to match our data.

From all these experiments, the models having the best performance in the test dataset including the remaining 10% of the AUB, NICU and CHB-MIT datasets were chosen for independing testing using the HOMI data which consist of an approximately 325-minute examination, representing 3788 five second fragments.

Results

Evaluation of classical machine learning models built from public EEG datasets

We built ML models using the eight different subsets of features individually, and the combination of all features, to train detection models for epileptic seizures using different classical machine learning approaches. Figure 1A shows a ROC curve comparing the sensitivity and false positive rate of the different algorithms trained using the combination of all features and default parameters. Using the AUROC as the metric, the best performing model was Random Forest Classifier (RFC) with a value of 0.972, followed by Support Vector Machine (SVM) with 0.934 and K Nearest Neighbours (KNN) with 0.924. The other algorithms obtained values below 0.9, being Naive-Bayes Classifier (NBC) the lowest with 0.729.

(A) ROC curve for models trained with different algorithms and the union of all features (All). SGD: stochastic gradient descent. SVM: support vector machine. RFC: random forest classifier. DTC: decision tree classifier. KNN: k-nearest neighbors. NBC: naive-bayes classifier. (B) F-Score for each algorithm trained using only one particular group of features, compared to the F-Score using the union of all features (last group of bars). C-D) ROC Curve and F-Score values for the Random Forest Classifier trained using only one particular group of features and performing gridsearch to optimize parameters.

Figure 1B shows the best F1-score metric for each detection on the test data of each model. The results of the models combining all the features (All) are consistent with those obtained in the ROC curve. Additionally, it can be observed that for all groups of features the models trained with RFC are the best performing, with values for F-score above 0.83, with the only exception of the Coherence feature. For the latter the best performing model was trained with SVM having an F-score of 0.846 when tested. In general, the other machine learning algorithms have different results depending on the feature used. However, NBC was consistently found to be the worst performer, with an F-score varying between 0.517 and 0.657. Overall the best models trained with default parameters were the combination of RFC with the ‘All’ feature obtaining an F-score value of 0.917 on the test data, followed by RFC with the Wavelets feature with a value of 0.916 and RFC with the PBand feature with an F-score of 0.913.

A grid search was executed on the RFC models to identify parameters that improve the performance of these models. Figure 1C shows the ROC curves after gridsearch was implemented and used on the test data. As expected the AUROC values improved for all models obtaining values above 0.91 for all calculated features. The best models obtained under this metric were those trained with all features (All), on the Wavelets feature and PBand, all with very similar values of 0.975, 0.972 and 0.971 respectively. The next best was TimeD with 0.957. The other models also performed well but with an AUROC of less than 0.93. Figure 1D shows the corresponding F1-score values, all of them higher than 0.82. Consistent with the ROC analysis, the models that exceeded the value of 0.9 for F-Score were those built from a combination of all features (0.918), using only Wavelets (0.917) and using only power bands (0.916). For all models, the best parameter values were 1 for min_samples_leaf, 2 for min_samples_split and 300 for n_estimators. As for the criterion parameter, for the All and PBand features it was entropy, while for Wavelets it was gini. These were the three best performing models from the machine learning section and chosen for further use on the clinical data from HOMI.

Evaluation of retrained deep learning models with public EEG datasets

We reproduced and retrained different neural network architectures from literature to build deep learning models for seizure classification using the raw signals from public databases. Figure 2A shows the ROC curve for each model, comparing the annotated windows with the gold standard annotations in the test dataset. All models obtained an AUROC higher than 0.94 except for FCN and ConvLSTM which had a lower performance with a value of 0.845 and 0.881 respectively. The best performing models were CNN1 with an AUROC value of 0.977, DCNN with 0.959, and CNN3 with 0.943. The model with the AE + biLSTM architecture obtained 0.917. Additionally, the graph includes the ROC curve for the best machine learning model obtained in the previous section. In this case, this ranks as the second best model with AUROC of 0.975. Figure 2B shows the best F-score obtained for each method. The ranking of models based on this metric was consistent with that inferred from the ROC analysis. The CNN1 and DCNN models are the only ones that exceed 0.9 F-Score, having 0.923 and 0.903 respectively. The RFC model with the combination of all features also ranked as the second best for this metric.

(A) ROC curve comparing the performance of neural network models. The performance of the random forest model with all features (RFC-All) is shown as a reference. (B) F-Score achieved by the models in the test dataset. DCNN: deep convolutional neural network. CNN1: convolutional neural network 1. CNN3: convolutional neural network 3. FCN: full convolutional neural network. AE + BiLSTM: auto encoder with LSTM layers. convLSTM: convolutional neural network with LSTM layers. RFC: random forest classifier with the combination of all calculated features (all). (C) Loss vs. Epoch for the CNN1 neural network model. D). Architecture of the CNN1 neural network model.

Figure 2C shows the loss value for the different training epochs for the CNN1 model. In this case, it is observed that the model reached its minimum loss at epoch 94 with a value of 0.041. Over this epoch the validation accuracy was 0.917. For the other models, the epoch with the lowest loss was 107 for FCN, 47 for CNN3, 78 for DCNN and 119 for AE + biLSTM. The validation accuracy values were 0.732, 0.883, 0.894 and 0.822 respectively. The architecture of the best performing model (CNN1) is shown in Fig. 2D. CNN1 starts with 5 blocks of convolutional layers and max pooling, followed by 2 dense layers for classification based on the space transformed by the convolutional layers. From these results, it was concluded that the best deep learning models were those that used the CNN1, CNN3 and DCNN architectures. These models will be subsequently evaluated on EEG exams from HOMI.

Evaluation of best trained models in HOMI clinical data

Our main goal for the evaluation experiments presented in this work was to select the most promising models for automated detection of peaks in EEG exams taken at HOMI. Hence, we further assessed the performance of the best models according to the previous evaluations on an EEG generated and manually annotated by experts at HOMI. Figure 3A shows the ROC curve of the chosen models tested on HOMI data. A large reduction of the performance of all models was revealed when tested on the new data set. Moreover, the model with the best metrics on the test data from public databases (CNN1) ranked last in this case with an AUROC of 0.495. The models achieving the best performance on these new data were the RFC with all the features and the RFC only with the Wavelets feature, which obtained AUROC of 0.656 and 0.602 respectively. The RFC model using only power band features obtained a value of 0.574. The best neural network model in this case was CNN3 (AUROC = 0.553) followed by DCNN (AUROC = 0.510). Figure 3B shows the best F1 score obtained for each model. The RFC with all features was also the best model according to this metric, but followed in this case by the CNN3 and the DCNN neural networks. The other models showed F1 scores below 0.6 (Supplementary Table 3).

(A) ROC curve for prediction of seizures by the selected models in the HOMI EEG. (B) F-Score achieved by each model. DCNN: deep convolutional neural network. CNN1: convolutional neural network 1. CNN3: convolutional neural network 3. RFC: random forest classifier. The RFC was trained with the combination of all calculated features (all), with the powerband feature calculation (Pband) and with the wavelets transform calculation. (C) Sum of distances from seizures manually annotated to seizures automatically detected by each model.

Trying to identify reasons explaining the accuracy gap between the two experiments, we investigated if lack of accuracy on the boundaries of manually annotated seizures could produce inflated numbers of detection errors (either false positives or false negatives). Hence, we developed alternative measures, calculating for each automated annotation the distance to the closest manual annotation, and for each manual annotation the distance to the closest automated annotation. These measures should give a smaller penalty to detection errors around the boundaries of the annotated events, compared to other error types. Figure 3C shows the results obtained calculating these measures. The RFC with all features and the CNN3 model are the most balanced, having the smallest distances in general. Random forest models trained on Power Bands or Wavelets, and CNN1 models have a similar behavior with automated annotations having a large distance to the closest manually annotated fragment, evidencing a large number of false positives not related to accuracy in boundaries of annotations. On the other hand, DCNN has the opposite behavior, showing a large distance between the manually annotated fragments to the closest automatically annotated fragment. This may be due to a large number of false negative fragments.

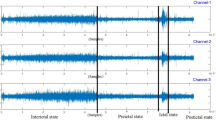

We confirmed the hypotheses drawn by the analysis of the distance measures by visualization and comparison of the seizure annotations. Figure 4 shows the result of the annotation performed by the models (colored tacks), compared to the manual annotation made by experts at the hospital (black track). The 5 s fragments of this examination are presented chronologically along the tracks. The manual annotation track shows 243 fragments marked with crises by experts. Regarding the neural networks, only 107 fragments are annotated by the DCNN model, confirming a low sensitivity. Conversely, the CNN1 model annotates seizures in 1275 fragments, which represents 33.6% of the total number of fragments (3788) and more than five times the number of fragments annotated with crises. Although the CNN3 model annotates 298 fragments, they do not have a good coincidence with the manually annotated fragments. The random forest models trained solely on power bands or on Wavelets appear to perform well in the first 70% of the test, annotating areas with seizure fragments similar to those in the manual annotation. However, they have a large number of false positives towards the end of the exam, obtaining a final number of fragments annotated as crisis of 1077 for Wavelets and 1038 for PBand, which translates into a poor specificity. Using all proposed features seems to alleviate this issue towards the end of the exam, without sacrificing accuracy in the first 70% of the exam. In total, this model classified 441 fragments with seizure, having the best performance across all metrics.

Results of the seizure detection process for the HOMI EEG across the 5.3 h of the exam. The track colored black represents the manual annotation performed by experts at the hospital, which was used as gold standard for benchmark purposes. The remaining tracks display the results of the models for automated detection. Lines on each track represent 5-second fragments labeled as part of a seizure event. DCNN: deep convolutional neural network. CNN1: convolutional neural network 1. CNN3: convolutional neural network 3. RFC: random forest classifier. The RFC was trained with the combination of all calculated features (all), with the powerband feature calculation (Pband) and with the wavelets transform calculation.

Computational efficiency of the detection models

Another aspect of interest of the trained models was the computational efficiency in both the training and the test process. Figure 5A shows training time for each of the algorithms used on clinical data using a server with 64 Gb of memory. Random forest with all features was the model taking the longest training time (over 50 h), mainly due to the time needed to calculate the features. This was followed by DCNN with 38.5 h. The remaining models took between 8 and 16 h to train.

(A) Total training duration in hours of each model used in the HOMI EEG. (B) Total duration of model classification on HOMI EEG. DCNN: deep convolutional neural network. CNN1: convolutional neural network 1. CNN3: convolutional neural network 3. RFC: random forest classifier. The RFC was trained with the combination of all calculated features (all), with the powerband feature calculation (Pband) and with the wavelets transform calculation.

Given the possible clinical utility of these models, we also calculated the time taken to analyze an exam. Figure 5B shows time for each of the models. Model of RFC + All is the model that takes the longest time and is far superior to the others. In total for an exam of approximately 6 h it took a little over 12 h to complete the classification task. This is due to the fact that it needs to calculate all features. The PBand and Wavelets models have a duration of 1.37 and 1.30 h respectively, which implies that they take a quarter of the test duration to perform the analysis. Finally, the neural network models were the fastest in the classification task, all lasting approximately one hour.

Discussion

A large number of methods and analysis techniques based on machine learning and deep learning models have been proposed for automated detection of seizures in EEGs, reporting high accuracies on controlled testing datasets9,12. Unfortunately, we observed in an initial attempt to use some of these methods on data taken from HOMI patients that the reported accuracy could not be replicated for our samples. Considering this scenario, the present manuscript summarizes the results of a systematic evaluation of several machine learning methods to detect seizures from EEG exams, first using publicly available datasets, and then using a manually annotated EEG taken from an HOMI patient. One possible reason for the gap between expected and observed accuracy could be related to limitations on the variability of the benchmark datasets. Hence, this work improves over previous benchmark experiments on the amount and variability of datasets used for training and testing, integrating data from three different sources and considering data from 109 different patients (Table 1). A wide variability of training data is very important to reduce bias and over fitting in machine learning models24.

Among the classical methods, the random forest models achieved the best accuracy even though all features were numeric. Looking for possible causes explaining the poor performance of other methods, we hypothesize that the amount of characteristics taken from the data could generate numerical stability problems for Naive Bayes, and inter correlation among features could reduce accuracy for SVM models. In contrast, the random forest approach was able to handle the heterogeneity among the different types of features extracted from the signals. Regarding feature importance, experiments using wavelet transformations showed an accuracy very close to that obtained combining all features. Experiments using only power band features also achieved good accuracy. This trend was consistently observed in the benchmark experiments using HOMI sample data, although both the F-score and the AUROC values were much lower than those obtained with public data.

Most recent works on automated seizure detection propose interpreting the EEG signal as an image or matrix, in order to adapt neural network architectures initially designed for image processing25,26. Unfortunately, previously developed models were not available to perform direct testing with our data. Hence, we tried to reproduce the proposed architectures and retrained the models using the combined public data. The AUROC and F1-score values obtained after testing with public data suggests that this reproduction attempt was successful. Differences between the exact values in this experiment and the values obtained in the initial experiments can be explained by the increased variability of datasets used for training and testing in this work. A convolutional neural network (CNN1) achieved the best accuracy, being slightly better than that achieved by the random forest model trained on the complete set of features. Unfortunately, also in this case it was not possible to transfer the high accuracy values to the detection of seizures for the HOMI EEG. Moreover, the ranking among architectures were not preserved in this case. The CNN1 architecture ranked last, having values close to those obtained by random guesses. All architectures ranked below the random forest model using all features. Detailed investigation of the results obtained in this EEG revealed a large number of false positives for the CNN1 and CNN3 networks and a large number of false negatives for the DCNN network. The random forest model also has a large number of false positives, especially if only a subset of features is used for training and testing. Deep learning models tend to be sensitive to the quality and characteristics of the data27. Although we performed a careful preprocessing of the raw signals to reduce possible sources of bias, this was not enough to transfer good accuracies to the HOMI EEG. Consistent preprocessing is critical to minimize performance degradation in cross-dataset testing due to variations between datasets.

The large accuracy gap observed between the experiments shown in this study is a major obstacle to transfer the models described in previous literature to the clinical practice in HOMI. Unlike the other data, this experiment only included data for one patient. Hence, we acknowledge that the results should not be used to draw general conclusions about the tested methodologies. However, we believe that this situation is also experienced by several other hospitals, especially those not closely connected with major research centers28. Possible causes explaining this outcome include issues with matching of clinical variables and different technical reasons. Regarding the clinical variables, the public datasets used for training cover a wide range of ages, but over two thirds of the patients are neonatal (Supplementary Table 2). Although we tried some further experiments with subsets of patients matching sex and with ages closer to the HOMI patient, the results were not better than those obtained with the models built from the complete datasets. Unfortunately, the seizure type was only available for the six patients of the AUB dataset. We acknowledge that a closer matching between training and testing datasets on variables such as age, sex, seizure type and even ethnicity can be an important precondition to develop an accurate and automated model for seizure detection. As future work, we plan to build a larger training data consisting of manually annotated exams from HOMI patients, in order to validate this hypothesis in our population.

Considering technical reasons, this outcome could be attributed to issues with the manual annotations used as gold standard. Differences among the judgment by different experts could be a factor contributing to the difference in the results of the testing with public datasets compared to the HOMI data. However, we could not observe a systematic trend in the results of the models suggesting a major region missed by the manual annotation of the HOMI EEG. The accuracy of the boundaries of manual annotations could also generate an inflated number of errors. Hence, we developed alternative metrics based on the distance between detected and annotated seizures, aiming to assign a smaller penalty to false positives in the boundaries of true regions, compared to those in regions far from an annotated region. Rankings based on the new measures were consistent with those obtained with F1-score and AUROC, suggesting that accuracy in the annotation boundaries is not a major determinant for the results of the benchmark experiments. Another technical aspect to consider is the natural imbalance between positive and negative windows in real datasets. This can be an issue taking into account that it is usually recommended to handle a good balance between positive and negative instances during the training and testing stages29. Finally, the accuracy gap could be produced by fundamental differences in data formats or other attributes between the public data used for training and the HOMI data. Although we could not identify any of such differences, if this would be the case, input formats and data preprocessing must be improved to transfer to real scenarios the accuracies reported by different models on public data.

The second major obstacle that we faced, trying to implement previously designed models at HOMI was the lack of availability of these models. Hence, we made available the models trained in this work and the code needed to use the models, facilitating independent evaluation of these models by other research groups. In general, we expect that this work contributes to the implementation of machine learning techniques as tools to improve the accuracy and opportunity of EEG exams for diagnosis of epilepsy patients.

Data availability

Scripts for preprocessing and to generate the models trained in this work and the trained models are available as part of the distribution of AIEpilepsy (manuscript in preparation) which is publicly available on github (https://github.com/SELF-Software-Evolution-Lab/AI-Epilepsy/tree/main/mlAIEp/EEGPaper). The EEG obtained from the HOMI patient is available at zenodo (https://zenodo.org/records/12587827). The public databases are available at https://zenodo.org/records/1280684#.ZDgf6NLMJGp for NICU, https://physionet.org/content/chbmit/1.0.0/ for CHB-MIT and https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/5pc2j46cbc/1 for AUB.

References

WHO. Epilepsy. (2024). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy

Falco-Walter, J. Epilepsy—definition, classification, pathophysiology, and epidemiology. Semin. Neurol. 40, 617–623. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1718719 (2020).

Devinsky, O. et al. Nat. Reviews Disease Primers 4, 18024 https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2018.24 (2018).

Fisher, R. S. The new classification of seizures by the international league against epilepsy 2017. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 17, 48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-017-0758-6 (2017).

Johnson, E. L. Seizures and epilepsy. Med. Clin. North Am. 103 (2), 309–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2018.10.002 (2019).

Miltiadous, A. et al. Machine learning algorithms for epilepsy detection based on published EEG databases: A systematic review. IEEE Access. 11, 564–594. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3232563 (2023).

Subha, D. P., Joseph, P. K., Acharya, U., Lim, C. M. & R. & EEG signal analysis: A survey. J. Med. Syst. 34 (2), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-008-9231-z (2010).

Noachtar, S. & Rémi, J. The role of EEG in epilepsy: A critical review. Epilepsy Behav. 15 (1), 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.02.035 (2009).

Siddiqui, M. K., Morales-Menendez, R., Huang, X. & Hussain, N. A review of epileptic seizure detection using machine learning classifiers. Brain Inf. 7 (1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40708-020-00105-1 (2020).

Donos, C., Dümpelmann, M. & Schulze-Bonhage, A. Early seizure detection algorithm based on intracranial EEG and random forest classification. Int. J. Neural Syst. 25 (05), 1550023. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0129065715500239 (2015).

Ahmad, M. A., Khan, N. A. & Majeed, W. Computer assisted analysis system of electroencephalogram for diagnosing epilepsy. 22nd International Conference on Pattern Recognition, 3386–3391 (2014). (2014). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPR.2014.583

Shoeibi, A. et al. Epileptic seizures detection using deep learning techniques: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18 (11), 5780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115780 (2021).

Nasreddine, W. Epileptic EEG dataset. Mendeley Data. https://doi.org/10.17632/5PC2J46CBC.1 (2021).

Stevenson, N., Tapani, K., Lauronen, L. & Vanhatalo, S. A dataset of neonatal Eeg recordings with seizures annotations. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.1280684 (2018).

Shoeb, A. CHB-MIT scalp EEG database. Physionet Org. https://doi.org/10.13026/C2K01R (2010).

Goldberger, A. L. et al. PhysioBank, physiotoolkit, and physionet: components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. Circulation 101 (23), e215–e220. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.101.23.e215 (2000).

Dlugos, D. et al. Pretreatment EEG in childhood absence epilepsy: associations with attention and treatment outcome. Neurology 81 (2), 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829a3373 (2013).

Gómez, C. et al. Automatic seizure detection based on imaged-EEG signals through fully convolutional networks. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 21833. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78784-3 (2020).

Wei, Z., Zou, J., Zhang, J. & Xu, J. Automatic epileptic EEG detection using convolutional neural network with improvements in time-domain. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 53, 101551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2019.04.028 (2019).

Xu, Y., Yang, J., Zhao, S., Wu, H. & Sawan, M. An end-to-end deep learning approach for epileptic seizure prediction. 2nd IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Circuits and Systems (AICAS) 266–270 (2020). (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/AICAS48895.2020.9073988

Abdelhameed, A. & Bayoumi, M. A deep learning approach for automatic seizure detection in children with epilepsy. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 15, 650050. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncom.2021.650050 (2021).

Yang, Y., Truong, N. D., Maher, C., Nikpour, A. & Kavehei, O. Continental generalization of a human-in-the-loop AI system for clinical seizure recognition. Expert Syst. Appl. 207, 118083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118083 (2022).

Cimr, D., Fujita, H., Tomaskova, H., Cimler, R. & Selamat, A. Automatic seizure detection by convolutional neural networks with computational complexity analysis. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 229, 107277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2022.107277 (2023).

Sevetlidis, V., Pavlidis, G., Mouroutsos, S. & Gasteratos, A. Tackling dataset bias with an automated collection of real-world samples. IEEE Access. 10, 126832–126844. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3226517 (2022).

Ryu, S. & Joe, I. A hybrid denseNet-LSTM model for epileptic seizure prediction. Appl. Sci. 11 (16), 7661. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11167661 (2021).

Qiu, X., Yan, F. & Liu, H. A difference attention ResNet-LSTM network for epileptic seizure detection using EEG signal. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 83, 104652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2023.104652 (2023).

Roy, Y. et al. Deep learning-based electroencephalography analysis: A systematic review. J. Neural Eng. 16 (5), 051001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/ab260c (2019).

Vanabelle, P., De Handschutter, P., El Tahry, R., Benjelloun, M. & Boukhebouze, M. Epileptic seizure detection using EEG signals and extreme gradient boosting. J. Biomedical Res. 34 (3), 228–239. https://doi.org/10.7555/JBR.33.20190016 (2020).

Ahsan, M. M., Ali, M. S. & Siddique, Z. Enhancing and improving the performance of imbalanced class data using novel GBO and SSG: A comparative analysis. Neural Netw. 173, 106157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2024.106157 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the Colombian Ministry of Science through the project with contract number 760-2021, awarded to JD. We also acknowledge the high-performance computing unit of Universidad de Los Andes for their technical support to conduct the benchmark experiments presented in this manuscript, and the financial support provided by the Vice Presidency of Research & Creation publication fund at the Universidad de los Andes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JD, SJMA and AN conceived the study and coordinated the project. JPCD, DGA and JJGP collected the samples and provided technical guidance. LG, JJGP and AN performed manual annotations of the EEGs and provided medical interpretation of the results. JPCD, KG and JD performed data analysis. JPCD and JD drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the latest version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carvajal-Dossman¹, J.P., Guio, L., García-Orjuela, D. et al. Retraining and evaluation of machine learning and deep learning models for seizure classification from EEG data. Sci Rep 15, 15345 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98389-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98389-y