Abstract

In this work, we propose a negative Poisson’s ratio metamaterial with added mass (NPM). Introducing added mass induces the emergence of new bandgaps, effectively reducing the bandgap frequency and widening its width. Simulation results show that added mass can generate new low-frequency bandgaps. Vibration transmission spectra of the structure are measured through vibration experiments, which closely matched the bandgaps, confirming the vibration reduction function of the structure. In addition, the energy absorption performance of the NPMs under quasi-static compression is experimentally tested. The results show that although the introduction of added mass affects the energy absorption effect to a certain extent, arranging the metamaterial units into a gradient structure based on the mass gradient significantly enhances the vibration isolation and energy absorption effects. This study presents a pioneering methodology for the development of integrated metamaterials capable of accommodating multiple functionalities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metamaterials are engineered materials distinguished by exceptional performance attained through precise arrangement and meticulous design of structural constituents. The remarkable capabilities encompass communication1,2, imaging3,4, energy absorption5,6, sound absorption7,8, load-bearing9,10, vibration reduction11,12, and cloaking13,14. Therefore, metamaterials garner widespread attention and demonstrate versatile applications across various domains, including acoustics, optics, electromagnetics, mechanics, and thermal science. However, in practical engineering scenarios, exceptional combinations of performance are often required to meet specific application demands. In specific submarine components, there is a critical need to simultaneously achieve acoustic cloaking capabilities alongside robust mechanical performance. Indeed, the characteristics of metamaterials are greatly influenced by their structural arrangement. Through careful structural design, a single-unit structure can demonstrate exceptional performance across multiple interdisciplinary domains. For example, Yu et al.15 successfully integrated zero thermal expansion properties and wideband vibration reduction capabilities into multiphase metamaterials. Moreover, Xiao et al.16 introduced a mechanical metamaterial characterized by exceptional vibration reduction capabilities and adjustable Poisson’s ratio. In engineering applications, the escalating need for structures or materials possessing multiple advantageous properties underscores the critical importance of delving deeper into multifunctional metamaterials17,18.

Among the exceptional properties exhibited by metamaterials, their capacity for vibration reduction and energy absorption stands out as particularly well-suited for real-world engineering applications. The efficacy of vibration reduction hinges primarily on the width and position of the bandgap within the structural dispersion curve19. The frequency band in which the bandgap resides corresponds to the highly efficient vibration reduction frequency range of the structure. The predominant mechanisms underlying the formation of bandgaps include Bragg scattering20 and local resonance phenomena21. The interaction of periodic lattices leads to Bragg scattering, resulting in the wavelength of the attenuated waves being only slightly different from the lattice size. Hence, the utilization of the Bragg scattering bandgap is constrained in low-frequency scenarios by the necessity of a large-scale system. On the contrary, the mechanism of the local resonance bandgap arises when the frequency of elastic waves equals the natural frequency of structural units, resulting in local resonance within the structure. This phenomenon enables the utilization of subwavelength-scale unit sizes, notwithstanding the relatively narrow width of the bandgap. Given the pervasive occurrence and adverse impacts of low-frequency vibrations and noise in real-world engineering applications, our research is centered on examining structures with the capability to induce local resonance bandgaps. Meanwhile, the energy absorption capacity under quasi-static compression is an important mechanical property of mechanical metamaterials22,23. The creation of energy-absorbing structures is predominantly accomplished through biomimetic design, empirical design, and topological optimization. The resultant structures primarily categorize into several types: laminated structures24, thin-walled structures25, porous structures26, honeycomb structures27,, and lattice structures28,29. The energy absorption capability of NPMs is primarily influenced by factors such as loading conditions, deformation modes, geometric configurations, and material properties. However, to date, research efforts aimed at integrating these two superior characteristics into a single metamaterial have been constrained.

Attaining optimal structural configurations is imperative for seamlessly integrating vibration reduction and energy absorption capabilities. Negative Poisson’s ratio metamaterials can integrate different mechanical properties. Therefore, utilizing a negative Poisson’s ratio honeycomb to integrate vibration reduction and energy absorption functions is a suitable approach. However, despite the varying degrees of energy absorption capabilities exhibited by negative Poisson’s ratio structures, the task of opening low-frequency bandgaps in such structures is nontrivial. The spring-mass system can be used to open low-frequency band gaps30,31. This refined approach contributes to the generation of local resonance phenomena, thereby creating local resonance bandgaps. Henceforth, we present a design methodology that amalgamates horizontal cell walls with mass blocks, aiming to fabricate structures exhibiting negative Poisson’s ratio properties while simultaneously possessing vibration reduction and energy absorption functionalities. Moreover, the functionally graded strategy is often employed to achieve the integrated design of composition, functionality, and structure in metamaterials. This endows the structure with spatially variable geometric parameters.

In this paper, the vibration reduction and energy absorption capabilities of NPMs are systematically investigated through simulations and experiments. In this paper, we present the structure and material properties of NPM. The material properties are measured through experiments. The dispersion curves are obtained through simulation analysis, while the transmission curves of elastic waves are measured experimentally. The dispersion curves and elastic wave transmission spectra are used to validate the low-frequency broadband vibration reduction characteristics of the NPM. In addition, we investigate the pressure-bearing and energy-absorbing capacity of the structure under quasi-static uniaxial compression through experiments and simulations. Based on the study of NPMs with a single geometric parameter, functionally graded structures with spatially variable geometric parameters are designed. This functionally graded strategy enhances the vibration reduction and quasi-static energy absorption performance of NPM.

Structure and material

In this section, we describe the structure of NPM. The NPM structure is fabricated using thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) through 3D printing techniques. Material parameters are experimentally acquired to improve the precision of simulation analyses.

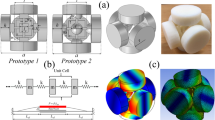

Figure 1a displays the 3D model of the NPM. It is observed that the designed unit cell comprises a concave hexagon and two isosceles triangles, serving as counterweights, connected to the horizontal cell walls. These counterweights are utilized to produce and adjust the local resonance bandgaps, a topic that will be further discussed in subsequent sections. The detailed geometric parameters are presented in Fig. 1b, including the length of the sloped cell walls \(\:b\), the lattice constant \(\:l\), the base angle of the counterweight \(\:{\upalpha\:}\), the length of the horizontal cell walls \(\:a\), the thickness of the cell walls \(\:t\), and the angle between the connected sloped cell walls \(\:\theta\:\). In addition, the out-of-plane width is denoted as \(\:h\), which can be found in Fig. 1a. The structural parameters can be found in Table 1.

Proposed NPM Structure. (a) 3D model of the NPM. (b) Unit cell structure and parameters. (c) First Brillouin zone of the reciprocal lattice of NPM, where the blue highlighted regions represent the irreducible Brillouin zone, and high-symmetry points are labeled with \(\:\varGamma\:\), \(\:X\), \(\:M\), and \(\:R\).

Relative density can be expressed by the geometrical parameters shown in Fig. 1b as

Thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) is selected as the base material due to its exceptional elasticity and resistance to deformation. Using fused deposition modeling (FDM) technology, NPM experimental specimens are 3D printed, while standard tensile specimens are prepared to test the mechanical properties of TPU by tensile testing32. The test results are employed for simulation analysis. The design parameters of the tensile specimens are illustrated in Fig. 2a. Fix the standard tensile specimen in the manner shown in Fig. 2b. Points A and B represent the initial positions of the two ends of the effective portion of the tensile specimen for tensile testing, with a pixel count of \(\:{L}_{0}\) between the two points. Therefore, the nominal strain ε of the tensile specimens can be expressed as

where\(\:\:L\:\)represents the pixel count between points A and B during uniaxial tensile testing. Additionally, the nominal stress σ of the tensile specimens can be expressed as

where \(\:F\) represents the force applied to the tensile specimen during uniaxial tensile testing, and \(\:{A}_{0}\) denotes the cross-sectional area of the effective portion of the standard tensile specimen. Uniaxial tensile tests are performed on tensile specimens using a universal testing machine at a speed of 5 mm/min. The tensile test is depicted in Fig. 2c. During uniaxial stretching, an industrial camera is used to capture clear images for post-production data acquisition. The test results are shown in Fig. 3, where at first the stress–strain curve initially increases linearly and then the slope gradually decreases. The experimentally obtained stress–strain curve shows that the material has a Young’s modulus (\(\:E\)) of 36 MPa, a yield stress (\(\:{\sigma\:}_{ys}\).) of 0.72 MPa, and a yield strain of about 0.02. Simultaneously, the Poisson’s ratio is determined as \(\:\nu\:\:=\:0.47\), and the mass density as \(\:{\rho\:}_{s}=\:477.5\) kg/m3, based on the quality, volume, and deformation characteristics of each specimen. These mechanical parameters are utilized for the finite element method (FEM) simulations in the subsequent sections.

Vibration reduction performance

The vibration reduction performance of NPM is elaborately elucidated in this section through an analysis of the dispersion curves of NPM and the transmission spectra of elastic waves. By analyzing the natural vibration modes of the NPM lattice, the mechanism for the formation of its low-frequency broadband performance is elucidated. The vibration reduction performance of NPM is validated using the experimentally obtained dispersion curve.

The Bravais lattice basis vectors are denoted by \(\:\overrightarrow{{a}_{i}}\left(i=\text{1,2}\right)\). In an orthogonal Cartesian coordinate system, the Bravais lattice basis vectors can be expressed as

where \(\:{L}_{i}\) represents the basis vectors of the orthogonal Cartesian coordinate system. Typically, the reciprocal lattice basis vectors are defined as

where \(\:\overrightarrow{{a}_{i}}\) denotes the Bravais lattice basis vectors, and \(\:{\overrightarrow{{a}_{j}}}^{*}\) denotes the reciprocal lattice basis vectors. The reciprocal lattice vector \(\:G\) is denoted as

where \(\:{n}_{1}\) and \(\:{n}_{2}\) are integers, the reciprocal lattice basis vectors can be expressed as

In two dimensions, by moving the cell along the Bravais lattice basis vectors (\(\:\overrightarrow{{a}_{1}}\), \(\:\overrightarrow{{a}_{2}}\)), periodic structures can be constructed. Therefore, the irreducible Brillouin zone is represented by the shaded area as shown in Fig. 1c.

The eigenwave function \(\:u\left(r\right)\) related to spatial position can be expressed as

In Eq. (10), \(\:r\) denotes the position vector, \(\:i\) denotes the imaginary unit, \(\:k\) represents the wave vector, and \(\:{U}_{k}\left(r\right)\) signifies the characteristic wave amplitude.

According to Bloch’s theorem, the relationship between the real-space position vector of a periodic structure and the wave loss in inverse reciprocal space can be expressed as follows

where\(\:\:R\:\)is a linear combination of Bravais lattice basis vectors.

Subsequently, the stiffness and mass matrices within the single cell are constructed to derive the generalized eigenforms. The resulting eigenvalue equations are represented as

where \(\:M\) denotes the mass matrix, \(\:K\) denotes the stiffness matrix, \(\:u\left(v\right)\) denotes the generalized node displacement, and \(\:F\) is the vector of applied force. where \(\:K\) denotes the stiffness matrix, \(\:M\) denotes the mass matrix, u(v) denotes the generalized node displacement, and F is the vector of applied force.

Employing Eq. (12) for overall calculations enables the structure to be simplified into a series of elements. The periodic condition at the boundary of the periodic cell is expressed as

where \(\:u\) represents the wave function, \(\:k\) represents the wavevector, and \(\:r\) represents the position vector.

The parametric sweep of the irreducible Brillouin zone along \(\:\varGamma\:\to\:X\to\:M\to\:R\to\:\varGamma\:\) is performed. Using Eqs. (12) and (13), the eigenfrequencies corresponding to the wave vector \(\:k\) can be obtained. The frequency range at which the bandgap appears in the dispersion curve signifies the principal vibration reduction frequency range of the structure. Meanwhile, utilizing simulation software allows for obtaining the vibration modes corresponding to different eigenfrequencies.

NPM specimens with varying geometric parameters of α = 10°, 20°, 30°, and 40° are fabricated. Each specimen comprises a \(\:3\times\:3\) array of unit cells, utilized for assessing the transmission of elastic waves through the metamaterial. The specimens with geometric parameters \(\:\alpha\:\) of 10°, 20°, 30°, and 40° are illustrated in Fig. 4a–d respectively.

Figure 5 illustrates the experimental setup used to measure the transmission spectra of NPM specimens with different geometric parameters. The experimental arrangement of the excitation system is shown in Fig. 5a. The lower surface of the thin plate is linked to the shaker, while an accelerometer (Sensitivity = 10.037 mV/(ms− 2)) is positioned on the upper surface to gauge the input signal. On the upper surface of the NPM, an accelerometer with a sensitivity of 10.037 mV/(ms− 2) is installed to gauge the output signal. In Fig. 5b, the dynamic signal acquisition and analysis system is depicted producing a sinusoidal sweep signal covering frequencies from 5 Hz to 3000 Hz. This signal is amplified by a power amplifier and subsequently utilized to actuate the shaker. The transmission function is defined as \(\:T=\:20{\text{log}}_{10}\left(\left|{A}_{out}/{A}_{in}\right|\right)\), where\(\:{A}_{out}\) and \(\:{A}_{in}\) represent the amplitudes of the output and input signals, respectively.

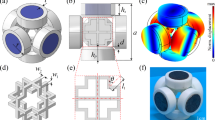

The FEM software COMSOL Multiphysics is utilized to generate dispersion curves and vibration modes of the unit cells. This enables an investigation into the vibration reduction effects of NPMs corresponding to various geometric parameters (α). Additionally, the elastic wave transmission spectrum in the RΓ-direction and XM-direction is experimentally determined for the structure. Figure 6 illustrates the results, where Fig. 6a–d display the outcomes for α = 10°, 20°, 30°, and 40° respectively. In Fig. 6, subfigures (i) to (iii) depict the dispersion curves, cross-section, and transmission spectrum of the NPM, respectively. As depicted in Fig. 6a(i), there is a bandgap in the RΓ-direction and XM-direction emerging at the frequency range of 321 Hz to 983 Hz. Figure 6a(iii) presents the experimental transmission spectrum, demonstrating a notable vibration attenuation valley with a minimum value of − 48.26 dB, spanning from 625 to 1162 Hz. With the increase of the geometric parameter α, an omnidirectional bandgap emerges within the frequency range of 1767–1863 Hz when α = 20°, as depicted in Fig. 6b(i). Figure 6b(iii) illustrates a vibration attenuation valley observed in the experimental transmission spectrum, spanning from 1445 to 2285 Hz, with a minimum value of − 44.68dB. For clarity of visualization, we shade the regions corresponding to the bandgap positions in the dispersion curve and their corresponding areas in the transmission spectra. The bandgap position on the dispersion curve in Fig. 6b corresponds to the location of the valley of vibration attenuation in the transmission spectrum of elastic waves. As the geometric parameter α increases, the bandgap gradually expands. When α = 30°, the position of this bandgap shifts from 1714 to 2551 Hz, as depicted in Fig. 6c(i). Figure 6c(iii) depicts a distinct region within the experimentally acquired transmission spectrum characterized by comparatively reduced transmittance. The minimum value observed in this region reaches − 41.59 dB. Remarkably, the transmission within this frequency range demonstrates minimal variation in the experimentally obtained transmission spectrum. As the value of α continues to increase to 40°, the position of this bandgap shifts to 1557 –3147 Hz, as illustrated in Fig. 6d(i). Figure 6b(iii) illustrates the experimental transmission spectrum, revealing a pronounced vibration attenuation valley ranging from 1557 to 3147 Hz, with a minimum value of − 52.80 dB. The following section delves into the mechanism behind the vibration reduction effect mentioned earlier.

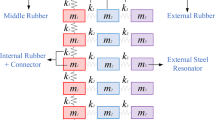

The dispersion curves of the NPM are calculated over a range of geometric parameters α from 17.5° to 40°, as depicted in Fig. 7. This analysis aims to provide additional insights into the mechanism responsible for the omnidirectional band gap. Figure 7a shows the variation of bandgap width and frequency with geometric parameter α. In the frequency range of 0–3000 Hz, there is almost no omnidirectional bandgap when α is less than 17.5°. When α = 20°, omnidirectional bandgaps begin to appear, with a bandgap ranging from 1767 to 1863 Hz, with a width of 96 Hz. As the value of α increases, the upper edge of the bandgap moves upward while the lower edge slowly descends, resulting in a gradual widening of the bandgap. When α achieves 40°, the bandgap ranges from 1557 to 3147 Hz, with a width of 1590 Hz. Furthermore, Fig. 7b,c respectively depict the vibration modes at the lower and upper edges of the bandgap when the geometric parameter α = 30°. From the vibration modes, it can be observed that the mechanism behind the formation of this bandgap is the equivalent of the NPM to a spring-mass system. Wherein the horizontal cell walls are equivalent to mass blocks, and the sloped cell walls are equivalent to springs. When subjected to external excitation, the system undergoes local resonance. An increase in the geometric parameter α increases the stiffness of the junction between the horizontal and sloped cell walls, leading to an upward movement of the upper edge of the bandgap. In addition, it increases the mass of the horizontal cell wall, causing the lower edge of the bandgap to move downward and the bandgap to gradually widen.

As shown in Eq. 1, with an increase in the geometric parameter \(\:\alpha\:\), the relative density (\(\:{\rho\:}_{r}\)) gradually increases. Thus, selecting appropriate geometric parameters effectively reduces vibrations while maintaining structural lightweightness.

Energy absorption performance

This section provides a detailed exposition of the quasi-static compression experiment and simulation of NPM. The deformation modes of NPM during quasi-static compression processes are analyzed. In addition, we evaluate the energy absorption performance of the NPM.

Poisson’s ratio is an essential parameter for describing NPM deformation modes. During the quasi-static compression process, the deformation modes of individual unit cells in NPM are illustrated in Fig. 8. As quasi-static compression proceeds, \(\:\varDelta\:\beta\:\) gradually increases. The strain in the x and y directions can be expressed in terms of \(\:\varDelta\:\beta\:\) as

and

respectively. Thus, the Poisson’s ratio of the NPM lattice is obtained as

After compaction, the geometric parameter relationship \(\:\pi\:/3-\varDelta\:\beta\:=\alpha\:\) holds. Thus, the Poisson’s ratio of the NPM lattice from the beginning of the compressed state to the compacted state can be expressed as

According to Eq. (17), numerical simulations investigated the relationship between the geometric parameter α and the Poisson’s ratio. The simulation results are depicted in Fig. 9. The Poisson’s ratios of NPM unit cells with geometric parameters α = 10°, 20°, 30°, and 40° are − 0.69, − 0.58, − 0.49, and − 0.41, respectively. The larger the geometric parameter α and the larger the Poisson’s ratio, the less pronounced the transverse deformation when the NPM is subjected to a longitudinal impact.

Quasi-static compression simulations are performed using Abaqus/CAE to examine the compressive behavior of NPM. Abaqus/CAE stands out as an exceptional finite element solid mechanics simulation software. In the simulation model, the lower plate is immobilized, while the upper plate is subjected to a downward compression at a velocity of 0.05 m/s. Fit the stress–strain curve illustrated in Fig. 3 to derive material parameters, and subsequently incorporate them into the software to construct a second-order elastic-plastic model. The rigid plate simulation model is partitioned using hexahedral elements (with a grain size of 3 mm), whereas the NPM simulation model is partitioned using tetrahedral elements (with a grain size of 2 mm) to improve computational efficiency.

Quasi-static compression testing of NPM 3D printed specimens is performed using a universal testing machine to validate and refine the finite element model. The experiment setup is illustrated in Fig. 10. The specimens are placed on a fixed steel plate and subjected to compression by the top steel plate at a loading rate of 4 mm/min. The compression direction is aligned with the tension direction in the tensile specimen testing to mitigate any potential anisotropy of the TPU material. Pressure levels are monitored by sensors embedded within the loading plate. At the same time, a high-definition industrial camera captures the deformation process. To ensure the reliability and diversity of results, tests are conducted on NPM specimens of four different sizes (α = 10°, 20°, 30°, 40°).

The uniaxial compression force-displacement response and structural deformation modes of NPMs are obtained through simulations and experiments, aiming to investigate the energy absorption capability of NPMs. Taking Fig. 11a as a reference, subfigures (i) to (iv) illustrate the compressive deformation modes of the NPM specimen under strain values of ε = 0.01, 0.1, 0.2 in the experimental setup, and 0.3, respectively. The corresponding simulation results are depicted in subfigures (v) to (viii) of Fig. 11a. The deformation mode labeled as “v” along the red dashed line during the compression process can be observed in Figs. (iii) and (vii). The cases corresponding to α = 20°, 30°, and 40° are depicted in Fig. 11b–d, respectively. Figure 12a illustrates the experimentally obtained force-displacement curves. The stress–strain curves are plotted based on the force-displacement curves, as depicted in Fig. 12b. The compaction strains \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{0}\) of the NPM specimens with α = 10°, 20°, and 30° are 0.10, 0.31, 0.46, and 0.57, respectively. Hence, as the geometric parameter α increases, the structure is compacted earlier. This is demonstrated in Fig. 11. As the angle α increases, the sloped cell walls are supported by the horizontal cell walls sooner, weakening the “v” deformation mode and resulting in less pronounced plateau stresses. Nevertheless, the structural load capacity gradually increases owing to the heightened bending stiffness of the cell walls and their earlier compaction. As shown in Fig. 13, the experimental results are in good agreement with the simulation results.

Specific Energy Absorption (SEA) is an important metric. The SEA represents the amount of energy absorbed by a structure per unit mass and is defined as

where \(\:F\left(\delta\:\right)\) represents the axial pressure, \(\:\delta\:\) denotes the displacement of the top steel plate during compaction, and \(\:{d}_{max}\) is the compaction displacement of the top steel plate, \(\:M\:\)is the total mass of the structure. With higher SEA values, the energy absorption capacity of the structure is better. Figure 14 illustrates the SEA-strain curves for different geometric parameters (α). When the strain value is 0.3, the specimen with α = 40° is compacted, while the specimens with α = 10°, 20°, and 30° have SEA values of 4.17 J/kg, 3.03 J/kg, and 2.68 J/kg, respectively. Therefore, the lower the geometric parameter \(\:\alpha\:\) is, the higher the SEA. According to experiments and simulations, this phenomenon is attributed to the fact that the smaller the geometric parameter of α, the smaller the stiffness of the horizontal cell wall. The experimental and simulation results indicate that the phenomenon arises from the increased elasticity of the horizontal cell walls as the geometric parameter α decreases. Simultaneously, the “V” deformation mode is more pronounced, resulting in more apparent plateau stresses, which enhances the structure’s energy absorption capacity under the same strain.

Functionally graded structure

In this section, we construct a functionally graded material with variable parameter α. The geometric parameters varying with space are shown in Fig. 15a. Figure 15b displays the 3D model of the gradient NPM structure. Meanwhile, 3D printed samples with non-gradient NPM structures consisting of \(\:3\:\times\:\:6\) unit cells are used for experimental tests.

The findings from Sections Three and Four suggest that the vibration reduction and energy absorption performance of NPM can be controlled by tuning the geometric parameter α of the lattice. Considering the impact of geometric parameters on these properties, we devise a straightforward functionally graded structure. In this structure, the geometric parameter α is adjusted while keeping other geometric parameters constant, thereby ensuring uniform connectivity among the unit cells. The experimental specimen is illustrated in Fig. 15c, with all other geometric parameters held constant. Meanwhile, the corresponding geometric parameters of the six-layer lattice, arranged from top to bottom, are as follows: α = 0°, 5°, 10°, 20°, 30°, 40°. The integration of different geometric parameters into a single structure realizes the low-frequency broadband design of negative Poisson’s ratio metamaterials while ensuring good energy absorption.

The bandgaps related to lattices with distinct geometric parameters α are anticipated to be incorporated into functionally graded structures, thereby achieving low-frequency broadband vibration attenuation. Figure 16 presents an experimental comparison of the elastic wave transmission spectra between the gradient and non-gradient structures, each exhibiting distinct vibration reduction zones. The transmission curve for \(\:\alpha\:=10^\circ\:\) exhibits a vibration attenuation valley with a minimum transmission value of − 60.30 dB between 742 and 2070 Hz, with the minimum value occurring at 1211 Hz. The transmission curve for \(\:\alpha\:=20^\circ\:\) exhibits a vibration attenuation valley with a minimum transmission value of − 59.22 dB between 1005 and 2363 Hz, with the minimum value occurring at 1640 Hz. The transmission curve for α = 30° exhibits a vibration attenuation valley with a minimum transmission value of − 61.24 dB between 1035 and 2402 Hz, with the minimum value occurring at 1836 Hz. The transmission curve for α = 40° exhibits two vibration attenuation valleys with minimum transmission values of − 42.89 dB and − 39.82 dB between 1162 and 3000 Hz. The minimum values occur at 1699 Hz and 2607 Hz respectively. As expected, the vibration attenuation valley of the gradient structure transmission spectrum in Fig. 16 is located between 250 and 3000 Hz, effectively addressing the usual narrowness of local resonance bandgaps at low frequencies.

Furthermore, the NPM specimens with \(\:6\times\:3\) unit cells and geometric parameters \(\:\alpha\:\) = 0°, 5°, 10°, 20°, 30°, and 40° are subjected to compression testing separately. Both experimental and simulation results (as depicted in Fig. 17) demonstrate that the first three layers of the functionally graded structure undergo compression and exhibit a “V” deformation mode, followed by significant deformation in the subsequent three layers. Correspondingly, the compaction process of functionally graded structures can be divided into a plateau stress stage and a compaction shrinkage stage (as depicted in Fig. 18). Simultaneously, the compaction strains of NPM specimens with geometric parameters α = 0°, 5°, 10°, 20°, 30°, and 40°, each containing \(\:3\times\:6\) unit cells, are measured as 0.10, 0.32, 0.46, and 0.62, respectively. The compaction strains exhibited by this set of specimens closely resemble the compaction strain observed in specimens featuring \(\:3\times\:3\) unit cells. The connection between compaction strain and lattice structure is intricately intertwined. The compaction strain of the functionally graded structure is 0.50, which is between the compaction strains of the NPM with α = 30° and α = 40°. In addition, at small deformations, the stress–strain curve of the functionally graded structure is analogous to that of the non-graded structure with α = 10°, as shown in Fig. 19. When the strain value is 0.3, the SEA values of the gradient structure and the non-graded structure with good energy absorption capacity at α = 10° are 3.46 J/kg and 3.44 J/kg, respectively. However, the energy absorption performance of the gradient structure is significantly better than that of the non-gradient structure, especially when the strain exceeds 0.3.

In summary, this functionally graded structure has good vibration reduction and energy absorption properties. The utilization of functionally graded structures incorporating diverse geometric parameters enables enhanced adaptability to a wide spectrum of engineering application contexts.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study designs a Negative Poisson’s Ratio Metamaterial with enhanced low-frequency broadband performance. The vibration reduction adaptability of NPM mainly relies on the phenomenon of local resonance. The exceptional performance of NPM is attributable to its lattice structure’s meticulous design, notably through the strategic incorporation of added mass blocks. This improved method contributes to the promotion of local resonance phenomena, thereby generating local resonance bandgaps. In addition, broadband and low-frequency vibration reduction can be attained through the adjustment of the mass of added mass blocks. In addition, functionally graded structures with spatially variable geometric parameters demonstrate remarkable design flexibility, thereby enhancing the vibration reduction and energy absorption capabilities of NPM structures Currently, there are multiple methodologies available for tailoring and optimizing the vibration reduction and energy absorption characteristics of metamaterials.

In summary, structures featuring a negative Poisson’s ratio demonstrate distinct advantages in seamlessly integrating vibration reduction and energy absorption capabilities. Owing to its extensive structural design freedom, this material exhibits a remarkable level of tunability and applicability in functionality. This research enables metamaterials to better accommodate interdisciplinary engineering applications.

Data availability

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to S. D., F. L., Z. S. and J. Y.

References

Sun, Z. Y. et al. Underwater acoustic multiplexing communication by pentamode metasurface. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 54, 205303 (2021).

Islam, M. T. et al. Analysis and characterization of structural, dielectric and magnetic properties of MgxCo(0.90–x) Zn0.10Fe2O4 nanoparticles based flexible metamaterial absorber for wireless communication. J. Alloy Compd. 959, 170395 (2023).

Zhu, J. et al. A holey-structured metamaterial for acoustic deep-subwavelength imaging. Nat. Phys. 7, 52–55 (2011).

Sun, Z., Zhao, L. & Yang, J. Underwater acoustic self-focusing and bending in conformal Mikaelian lens by pentamode metafluid. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 56, 505304 (2023).

Qi, C. et al. Quasi-static crushing behavior of novel re-entrant circular auxetic honeycombs. Compos. Part. B-Eng. 197, 108117 (2020).

Qin, S., Deng, X., Yang, F. & Lu, Q. Energy absorption characteristics and negative Poisson’s ratio effect of axisymmetric tetrachiral honeycombs under in-plane impact. Compos. Struct. 323, 117493 (2023).

Ma, F., Wang, C., Du, Y., Zhu, Z. & Wu, J. H. Enhancing of broadband sound absorption through soft matter. Mater. Horiz. 9, 653–662 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Laser additive manufacturing of hierarchical multifunctional chiral metamaterial with distinguished damage-resistance and low-frequency broadband sound-absorption capabilities. Mater. Des. 238, 112659 (2024).

Zhai, Z., Wang, Y. & Jiang, H. Origami-inspired, on-demand deployable and collapsible mechanical metamaterials with tunable stiffness. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 115, 2032–2037 (2018).

Clarke, D. J., Imediegwu, C., Moat, R. & Jowers, I. A systematic numerical and experimental study into the mechanical properties of five honeycombs. Compos. Part. B-Eng. 264, 110895 (2023).

Ji, J. C., Luo, Q. & Ye, K. Vibration control based metamaterials and Origami structures: A state-of-the-art review. Mech. Syst. Signal. Process. 161, 107945 (2021).

Li, Y., Zhang, J., Li, J. & Guo, S. Design of a broadband composite noise reduction metamaterial with integrated vibration reduction and sound absorption and insulation. Mater. Des. 238, 112709 (2024).

Schurig, D. et al. Metamaterial electromagnetic cloak at microwave frequencies. Science 314, 977–980 (2006).

Sun, Z., Sun, X., Jia, H., Bi, Y. & Yang, J. Quasi-isotropic underwater acoustic carpet cloak based on latticed pentamode metafluid. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 094101 (2019).

Yu, D., Hu, G., Ding, W., Yang, Y. & Hong, J. Zero-thermal-expansion metamaterial with broadband vibration suppression. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 258, 108590 (2023).

Xiao, B. et al. A bistable honeycomb mechanical metamaterial with transformable Poisson’s ratio and tunable vibration isolation properties. Thin Wall. Struct. 198, 111718 (2024).

Kim, J. & Torquato, S. Multifunctional composites for elastic and electromagnetic wave propagation. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 117 8764–8774 (2020).

Li, W., Pei, R. & Xu, F. Composite metamaterial antenna with super mechanical and electromagnetic performances integrated by three-dimensional weaving technique. Compos. Part. B-Eng. 273, 111265 (2024).

Jiang, W., Yin, G., Xie, L. & Yin, M. Multifunctional 3D lattice metamaterials for vibration mitigation and energy absorption. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 233, 107678 (2022).

Li, F., Chen, Y. & Zhu, D. Revealing the sound transmission loss capacities of sandwich metamaterials with re-entrant negative Poisson’s ratio configuration. Materials 16, 5928 (2023).

Lu, K. et al. Flexural vibration bandgaps of the multiple local resonance elastic metamaterial plates with irregular resonators. Appl. Acoust. 159, 107115 (2020).

Ma, F., Wang, C., Liu, C. & Wu, J. H. Structural designs, principles, and applications of thin-walled membrane and plate-type acoustic/elastic metamaterials. J. Appl. Phys. 129, 231103 (2021).

Chen, S. et al. Elastic architected mechanical metamaterials with negative stiffness effect for high energy dissipation and low frequency vibration suppression. Compos. Part. B-Eng. 267, 111053 (2023).

Fu, T., Hu, X. & Yang, C. Impact response analysis of stiffened sandwich functionally graded porous materials doubly-curved shell with re-entrant honeycomb auxetic core. Appl. Math. Model. 124, 553–575 (2023).

Tao, R. et al. 4D printed Origami metamaterials with tunable compression twist behavior and stress–strain curves. Compos. Part. B-Eng. 201, 108344 (2020).

Ghafouri, M., Ghassabi, M. & Talebitooti, R. Applying a 3D re-entrant auxetic cellular core to a graphene nanoplatelet–reinforced doubly curved structure: A sound transmission loss study. J. Eng. Mech. 149, 04023077 (2023).

Xu, P. et al. Compression behavior of 4D printed metamaterials with various Poisson’s ratios. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 264, 108819 (2024).

Li, T. & Li, Y. Mechanical behaviors of three-dimensional chiral mechanical metamaterials. Compos. Part. B-Eng. 270, 111141 (2024).

Montazeri, A., Saeedi, A., Bahmanpour, E. & Mahnama, M. Auxetic mechanical metamaterials with symmetry-broken re-entrant units. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 266, 108917 (2024).

Matlack, K. H., Bauhofer, A., Krödel, S., Palermo, A. & Daraio, C. Composite 3D-printed metastructures for low-frequency and broadband vibration absorption. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 113, 8386–8390 (2016).

Liu, X. N., Hu, G. K., Sun, C. T. & Huang, G. L. Wave propagation characterization and design of two-dimensional elastic chiral metacomposite. J. Sound Vib. 330, 2536–2553 (2011).

Hu, L. L., Wu, Z. J. & Fu, M. H. Mechanical behavior of anti-trichiral honeycombs under lateral crushing. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 140, 537–546 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors and reviewers for their support and help with this article.

Funding

This work is funded by the Beijing Municipal Education Commission & Beijing Natural Science Foundation Co-financing Project (Grant No. KZ202210015019), Project of Construction and Support for high-level Innovative Teams of Beijing Municipal Institutions (Grant No. BPHR20220107).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: Y.L., Z.S., S.D.; data collection: F.L., R.L., S.Y.; analysis and interpretation of results: Y.L., D.Y., Z.S., J.Y., L.Z.; draft manuscript preparation: Y.L., Z.S., S.D. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Dou, S., Du, Y. et al. Enhanced broadband low-frequency performance of negative Poisson’s ratio metamaterials with added mass. Sci Rep 15, 13838 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98598-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98598-5