Abstract

While the efficacy and safety of drug-coated balloons (DCBs) for treating short femoropopliteal lesions are well-established, evidence on long-term outcomes for long lesions remains limited. This study aims to compare the 2-year clinical outcomes of DCB angioplasty between long and short femoropopliteal lesions and identify risk factors for patency loss. This real-world and single-center cohort study included 234 patients with de novo stenosis or restenosis or occlusion of the femoropopliteal arteries (115 long lesions > 15 cm, 141 short lesions ≤ 15 cm) who underwent successful DCB treatment from January 2019 to December 2021 at Peking Union Medical College Hospital. The primary safety endpoint was defined as freedom from major adverse events (death, target limb amputation or thrombosis). The primary effectiveness endpoint was defined as 2-year primary patency, defined as freedom from both clinically driven target lesion revascularization (CD-TLR) and restenosis. Primary patency was significantly lower in long lesions (48.3% vs. 62.5%, p = 0.005), while freedom from CD-TLR rate showed no difference (83.6% vs. 87.4%, p = 0.25). Long lesions exhibited higher rates of occlusions (p < 0.001), in-stent restenosis (p = 0.025), and advanced ischemia (Rutherford Clinical Category (RCC) 4–6, p = 0.038). Multivariate analysis identified lesion length > 15 cm (p = 0.017) and RCC 4–6 (p = 0.026) as independent predictors of patency loss. Within the long lesion subgroup, only RCC 4–6 maintained prognostic significance (p = 0.027), and no significant predictors emerged in the short lesion group. Major adverse events occurred in 12.4% of patients, predominantly in long lesions with severe comorbidities. While DCB angioplasty achieved acceptable 2-year safety outcomes, long femoropopliteal lesions (> 15 cm) demonstrated significantly inferior primary patency compared to short lesions (48.3% vs. 62.5%, p = 0.005). Advanced ischemia (RCC 4–6) is a risk factor for patency loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lower extremity peripheral arterial disease (PAD) affects over 200 million individuals globally and is associated with significant morbidity, including coronary heart disease, stroke, and limb amputation1. Drug-coated balloons (DCBs) have emerged as a first-line endovascular therapy for femoropopliteal lesions due to their ability to reduce restenosis through localized antiproliferative drug delivery (e.g., paclitaxel)2,3. Extensive research has demonstrated that DCBs are both safe and effective in treating femoropopliteal lesions4,5,6,7,8,9,10. However, evidence for their use in long lesions (> 15 cm) remains limited. This study aims to evaluate 2-year outcomes of DCB angioplasty in femoropopliteal lesions, comparing long and short lesions and identifying prognostic factors.

Methods

Study population

This single-center retrospective study included patients with femoropopliteal lesions treated with Orchid DCB (Acotec Scientific, Beijing, China) angioplasty at Peking Union Medical College Hospital from Jan 2019 to Dec 2021. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013) and was approved by the institutional review boards. The inclusion criteria were Rutherford Clinical Category (RCC) ≥ 3 and DCB use for femoropopliteal occlusive disease. The exclusion criteria were non - DCB interventions, unsuccessfully guidewire crossing, acute limb ischemia, or non-atherosclerotic pathologies (e.g., aneurysms, vasculitis, bypass restenosis)7,11. Baseline demographics, comorbidities, and imaging data (Ankle-brachial index (ABI) value, computed tomography angiography (CTA), and ultrasound) were collected.

Procedures and devices

Pre-procedural antiplatelet therapy (aspirin 100 mg/day) was standardized. During the procedure, the ipsilateral or contralateral femoral artery was punctured and 75 IU/kg heparin was administered after the sheath insertion. After venous heparinization, a guidewire and catheter were advanced across the lesion, and vascular preparation techniques were tailored to lesion characteristics. Lesion characteristics were visually estimated with Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA) during the procedure. Common methods of vessel preparation include uncoated balloon pre-dilation, thrombus aspiration, and atherectomy. If the residual stenosis exceeded 50% after pre-dilation, sequential dilation with a larger balloon was performed. For flow-limiting dissections, balloon angioplasty matching the native vessel diameter was prioritized to optimize apposition. Persistent dissections necessitated bailout stenting, bypassing DCB use. Orchid DCBs (2–6 mm in diameter, 40–300 mm in length, excipient: magnesium stearate, paclitaxel dose: 3.3 µg/mm2) were selected to exceed the pre-dilatation balloon diameter by 1.0 mm and inflated at 6–12 atm for 3 min. Post-DCB angioplasty, adjunctive balloon dilation was performed if residual stenosis > 30% or flow-limiting dissection was present. A bailout stent was deployed if the residual stenosis > 30% or flow-limiting dissection persisted. Bailout stents used include Protégé Everflex (Covidien, Plymouth, Minn), LifeStent (Bard, Tempe, AZ), and Innovjie (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA). Procedural success required ≤ 30% residual stenosis, absence of flow-limiting dissection on final angiography.

Postoperatively, dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin 100 mg/day of + clopidogrel 75 mg/day) was prescribed for ≥ 12 weeks, followed by indefinite monotherapy.

Follow-up protocol

Follow-up was routinely performed by telephone and outpatient service at 6, 12, and 24 months after DCB surgery. Symptoms, adverse events, duplex ultrasound, and CTA report (not mandatory) were collected at follow-up visits. The recommended time for imaging reexamination is every six months after the operation. All collected data regarding symptoms and adverse events were adjudicated through an independent assessment. A panel of at least two experienced clinicians who were not involved in the patients’ preoperative care and treatment were selected.

Study endpoints and definitions

The primary safety endpoint was defined as freedom from major adverse events (MAEs) at 2 years, with MAEs encompassing all-cause mortality, target limb amputation or thrombosis. The primary effectiveness endpoint was defined as 2-year primary patency, defined as freedom from both clinically driven target lesion revascularization (CD-TLR) and restenosis (< 50% residual lumen diameters in the target lesion under CTA, or peak systolic velocity ratio ≤ 2.4 under Doppler ultrasound examination)12,13.

Target vessels specifically refer to femoropopliteal arteries (including the common femoral, deep femoral, superficial femoral, and popliteal arteries) undergoing revascularization during a single procedure. For example, endovascular revascularization of a diffusely diseased superficial femoral artery (SFA) is counted as 1 target vessel. Concurrent treatment of SFA and popliteal artery lesions in the same procedure is counted as 2 target vessels. Other peripheral vascular lesions (PVLs) were defined as > 50% stenosis in non-femoropopliteal arteries (renal, carotid, vertebral, or subclavian arteries). Severe calcification was defined as continuous calcific deposits ≥ 5 cm in length along the affected arterial segment. On ultrasound, this manifested as a hyperechoic linear region ≥ 5 cm, while CTA revealed a continuous high-density arterial wall shadow ≥ 5 cm14,15. Calcification assessments were conducted using standardized measurement protocols with semi-automated length quantification. A blinded dual-reader validation subset (20% of cases) demonstrated substantial inter-observer agreement (κ = 0.78). Periodic calibration using a reference image bank was performed to maintain interpretive consistency. Femoropopliteal lesions were stratified as long (> 15 cm) or short (≤ 15 cm) based on lesion length.

Statistical analysis

Baseline data were presented as mean ± SD for normally distributed continuous variables and as counts (percentages) for categorical variables. Normality was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk tests. Between-group comparisons employed independent t-tests for normally distributed variables and Mann-Whitney U tests for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Time-to-event outcomes (primary patency and CD-TLR-free survival) were estimated via Kaplan-Meier curves, with subgroup comparisons conducted using log-rank tests. For patients lost to follow-up (< 5% of the cohort), the Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) method was applied to survival analyses, assuming data were missing completely at random. Subgroup analyses incorporated Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple comparisons. Cox proportional hazards regression models identified predictors of primary patency loss. Variables with significant univariate associations (p < 0.05) and clinically validated risk factors were included in multivariate models. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed). Analyses were performed using SPSS version 26 (IBM, Chicago, Illinois) and Prism version 9.3.0 (GraphPad Software, Boston) for Windows.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 256 target lesions among 234 patients were included in this study. Procedural success was achieved in all included patients. Demographic characteristics were presented in Table 1. The cohort comprised 103 patients (44.0%) with lesion lengths > 15 cm (mean age 67.3 ± 9.3 years) and 131 patients (56.0%) with lesions ≤ 15 cm (mean age 65.8 ± 10.0 years). Patients with longer lesions demonstrated significantly higher prevalence rates of comorbid hypertension (p = 0.013) and other PVLs (p < 0.001) compared to the shorter lesion group.

Limb and lesion characteristics

Limb and lesion characteristics were given in Table 2. The long lesion group exhibited significantly lower ABI values (p = 0.002), higher incidence of total occlusions (p < 0.001), and greater prevalence of in-stent restenosis (p < 0.001). No significant intergroup differences were observed in calcification severity or below-the-knee disease distribution. Bilateral arterial stenosis/restenosis predominated in both cohorts. Bailout stents were implanted in 15.7% of patients in long lesion group and 9.9% of patients in short lesion group for reasons including dissection and residual stenosis > 30%.

Follow-up outcomes

Effectiveness outcomes

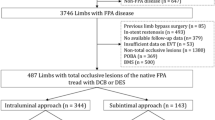

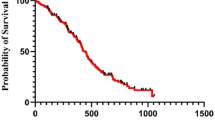

Postprocedural follow-up averaged 726 ± 15 days (median 725 days), with 22 non-perioperative deaths and 6 lost-to-follow-up cases (Fig. 1). Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed 2-year primary patency of 56.10 ± 3.28% and freedom from CD-TLR of 85.71 ± 2.32% (Fig. 2). Comparative analysis showed superior primary patency in the short lesion group (62.51% vs. 48.28%, p = 0.005), while freedom from CD-TLR rate showed no statistical difference (87.42% vs. 83.60%, p = 0.250) (Fig. 3).

Post hoc subgroup analyses identified predictors of primary patency loss in entire cohort: Lesion length > 15 cm (p = 0.005), target vessels = 2 (p = 0.018), presence of total occlusion (p = 0.020), RCC 4–6 vs. RCC 3 (p = 0.025), and ≥ 2 PVLs vs. < 2 PVLs (p = 0.043) (Table 3). Multivariate Cox regression analysis of the entire cohort identified RCC 4–6 (p = 0.026) and lesion length > 15 cm (p = 0.017) as independent predictors of primary patency loss (Fig. 4a). Within the long lesion subgroup, only RCC 4–6 maintained prognostic significance (p = 0.027) (Fig. 4b). No significant predictors emerged in the short lesion group (Fig. 4c).

Safety outcomes

MAEs occurred in 12.4% (29/234). All-cause mortality occurred in 9.4% (22/234) of patients (mean age 67.8 ± 9.3 years, excluding perioperative deaths), with causes including myocardial infarction and heart failure (n = 5), malignancy (n = 5), diabetic complications (n = 4), COVID-19 (n = 3), cerebral infarction (n = 1), and unspecified etiologies (n = 4). Major target limb amputation (excluding intraoperative amputation) occurred in 7 patients (5 within first year, 2 subsequently). Of these 29 patients, 9 patients (31.0%) presented with tissue damage (RCC 5–6), 24 patients (82.8%) had complete occlusion of the target vessels, and 15 patients (51.7%) had lesions accompanied by calcification, 16 patients (55.2%) presented with lesions in ≥ 2 below-the-knee arteries, 14 patients (48.3%) had long lesions.

Discussion

This real-world comparative study evaluated the 2-year clinical outcomes of DCB therapy for long (> 15 cm) versus short (≤ 15 cm) femoropopliteal lesions. The results confirm lesion length as an independent predictor of therapeutic efficacy. Key findings revealed significantly diminished primary patency rates in the long lesion cohort (48.28% vs. 62.51%, p = 0.005), while comparable freedom from CD-TLR rates were observed (83.60% vs. 87.42%, p = 0.250). The latter discrepancy may reflect clinical inertia in treating asymptomatic restenosis16. These results are consistent with the results of previous cohort studies on complex lesions7, suggesting the challenges faced in the treatment of long lesions.

Notably, the long lesion group exhibited distinct pathoanatomical challenges: 90.4% presented with chronic total occlusions versus 53.9% in controls (p < 0.001), coupled with higher calcification prevalence (55.7% vs. 48.9%). While severe calcification is mechanistically linked to vascular stiffness and impaired paclitaxel transfer, thus leading to a higher rate of postoperative restenosis17,18. However, our analysis demonstrated no direct association between calcification presence and patency loss (p = 0.761). This null finding likely reflects methodological limitations in our approach to calcification assessment, particularly the reliance on a binary classification (present/absent), which oversimplifies the complex interplay between calcification characteristics and DCB efficacy. Current evidence underscores the need for more sophisticated classifications to capture the prognostic implications of PAD. Studies have demonstrated that calcification exceeding 270° of the vessel circumference is associated with significantly worse patency rates and higher restenosis following DCB therapy19. Similarly, the pattern of calcification—whether medial or intimal—appears to exert differential impacts on vessel behavior and treatment response20. Medial calcification, known as Mönckeberg’s sclerosis, is prevalent in patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease. It increases arterial stiffness and reduces vessel compliance, potentially hindering drug penetration and efficacy. Intimal calcification, conversely, is typically linked to atherosclerotic plaque burden and may pose distinct challenges to DCB performance20,21. The broader literature consistently supports the notion that calcified lesions reduce DCB efficacy. For example, a multicenter, prospective cohort by Soga et al. identified calcification as a predictor of worse outcomes22. These findings contrast with our results, further highlighting the limitations of our crude assessment method. Beyond binary classification, even simplistic quantitative metrics—such as the proportion of calcified area to the region of interest—lack the discriminative power to fully elucidate calcification’s impact23. The absence of standardized scoring systems for PAD calcification remains a critical barrier to progress. In coronary artery disease, tools like the Agatston score provide a robust framework for quantifying calcium burden24. However, no similar consensus exists for PAD, which complicates cross-study comparisons and prognostic stratification.

The femoropopliteal segment presents unique biomechanical challenges due to dynamic forces (bending, torsion, compression), exacerbating device failure risks in long lesions16. Historically, open surgery was the preferred approach for complex femoropopliteal cases25. However, recent retrospective studies have demonstrated that endovascular treatments offer higher long-term patency rates, shorter hospital stays, and lower treatment costs compared to open surgery26,27. Modern endovascular strategies combine staged vessel preparation (e.g., angioplasty, atherectomy, lithotripsy) with definitive therapies such as DCB or stents. This integration provides clinicians with versatile options to address these challenging lesions. DCBs deliver localized antiproliferative agents to suppress intimal hyperplasia while maintaining vessel architecture through a “leave nothing behind” approach12. This characteristic makes them theoretically advantageous for mitigating stent-related long-term complications such as in-stent restenosis and thrombosis. However, stents - especially drug-eluting stents (DES) - provide essential mechanical scaffolding that proves critical in the biomechanically challenging FPA environment characterized by compressive forces and dynamic movement17. Multiple prospective multicenter randomized controlled trials have shown that, for long femoropopliteal lesions, the 1-year patency rates of DES and DCB are comparable, but DES demonstrate superior long-term patency28,29. Our institutional data corroborates these findings, demonstrating a suboptimal 48.3% 2-year primary patency rate for DCB in lesions exceeding 15 cm. This modest efficacy suggests inherent limitations of standalone DCB therapy for complex long-segment disease. A key consideration in the debate between DCB and DES is the role of bailout stenting in DCB-treated lesions. The longer the lesion, the higher the likelihood of complications such as vessel recoil or dissection, necessitating bailout stenting to maintain vessel patency. Zenunaj et al. found that the bailout stenting rate in the DCB arm was significantly higher (14.8–25.1%), particularly in longer lesions, yet this did not translate into a significant benefit in terms of primary patency or TLR compared to primary DES use30. Bailout stenting is frequently required in DCB-treated cases. This may negate DCB’s key advantage of avoiding permanent implants, creating a stent-like outcome with increased procedural complexity but no long-term benefit. This suggest that primary DES use may be a more effective and straightforward strategy for these complex cases. Clinical application patterns show DCBs are primarily utilized in mid-length (< 15 cm) lesions with light calcification, whereas DESs demonstrate preference for extended segments (≥ 15 mm) and severe calcification26. In a randomized controlled trial of femoropopliteal artery interventions with mean lesion length of 14 cm, systematic DES strategy demonstrated significantly larger postoperative minimum lumen diameter and lower incidence of residual dissection compared to DCB. Notably, nitinol stents were deployed in 21% of DCB-treated lesions28. In our study, DCB showed a 48.3% 2-year patency rate for long lesions, consistent with previous findings. For complex long lesions, primary stent implantation or bypass surgery may be preferable as first-line options, while DCB could be reserved for shorter lesions or specific anatomical scenarios (e.g., younger patients, anatomical constraints favoring future revascularization). Clinically, this suggests the importance of lesion-specific treatment planning, where factors such as lesion length, calcification, and anticipated need for scaffolding should guide the choice between DCB and DES.

Advanced chronic limb ischemia (RCC 4–6) was disproportionately prevalent in long lesions (28.5% vs. 15.8%, p = 0.038), with multivariate Cox regression identifying RCC 4–6 as an independent risk factor for patency loss (HR 1.85, p = 0.027). This aligns with the pathophysiological paradigm of progressive microvascular dysfunction in advanced PAD, where chronic hypoxia induces capillary remodeling and hemodynamic compromise31. Such microcirculatory deterioration may explain the limited efficacy of macrovascular revascularization alone in this subgroup. The incidence of MAEs in our study was relatively high (12.4%). During the study period, SARS-CoV-2 pandemic-related factors may have contributed through multiple pathways. Hypercoagulability is part of the potential pathogenesis of atherosclerotic diseases such as PAD, which is consistent with the characteristics related to SARS-CoV-232. Among patients hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2 infection, the mortality rate and the odds of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with PAD increased by more than 40%33. However, absent granular virological data (infection rates, severity, treatments), causal inferences remain speculative.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations inherent to its retrospective single-center design. First, the absence of comparative treatment arms precludes direct evaluation of DCB performance against alternative therapies (e.g., DES, atherectomy). Second, potential selection bias exists in DCB allocation. The treatment choice is a dynamic intraoperative decision subjectively made by surgeons, which may limit generalizability to broader PAD populations. Third, calcification assessments relied on qualitative imaging criteria without standardized quantitative scoring, introducing interobserver variability. Fourth, 2.6% of patients were lost to follow-up, and although the Last Observation Carried Forward method was employed, missing longitudinal imaging data (23% of cases) may compromise outcome validity. Fifth, the exclusion of non-DCB interventions and reliance on operator-dependent bailout stenting (15.7% in long lesions) may confound patency outcomes. Finally, the exclusive use of a single DCB device (Orchid DCB) precludes conclusions about generalizability to other DCB products, given known inter-device variations in drug formulation and coating technologies34.

Conclusions

While DCB angioplasty achieved acceptable 2-year safety outcomes, long femoropopliteal lesions (> 15 cm) demonstrated significantly inferior primary patency compared to short lesions (48.3% vs. 62.5%, p = 0.005). Advanced ischemia (RCC 4–6) is a risk factor for patency loss. These results question DCB’s efficacy in complex long-segment disease and highlight the need for alternative strategies, such as lesion-specific device selection or hybrid therapies, to optimize durability.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PAD:

-

Peripheral arterial disease

- DCB:

-

Drug-coated balloon

- PVL:

-

Peripheral vascular lesion

- RCC:

-

Rutherford Clinical Category

- ABI:

-

Ankle-brachial index

- CTA:

-

Computed Tomography Angiography

- DSA:

-

Digital Subtraction Angiography

- CD-TLR:

-

Clinically driven target lesion revascularization

- PPA:

-

Popliteal artery

- DES:

-

Drug eluting stent

References

Criqui, M. H. et al. Lower extremity peripheral artery disease: contemporary epidemiology, management gaps, and future directions: A scientific statement. Am. Heart Association. 144 (9), e171–e91. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001005 (2021).

Byrne, R. A., Joner, M., Alfonso, F. & Kastrati, A. Drug-coated balloon therapy in coronary and peripheral artery disease. Nat. Reviews Cardiol. 11 (1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2013.165 (2014).

Mehrotra, S., Paramasivam, G. & Mishra, S. Paclitaxel-Coated balloon for femoropopliteal artery disease. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 19 (2), 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-017-0823-4 (2017).

Soga, Y. et al. Vessel patency and associated factors of Drug-Coated balloon for femoropopliteal lesion. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12 (1), e025677. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.122.025677 (2023).

Banerjee, S. & Khalili, H. Drug-Coated balloon for long femoropopliteal lesions. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 11 (10), e007084. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.007084 (2018).

Micari, A. et al. Drug-Coated balloon treatment of femoropopliteal lesions for patients with intermittent claudication and ischemic rest pain: 2-Year results from the IN.PACT global study. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 11 (10), 945–953. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2018.02.019 (2018).

Schmidt, A. et al. Drug-Coated balloons for complex femoropopliteal lesions: 2-Year results of a Real-World registry. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 9 (7), 715–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2015.12.267 (2016).

Tepe, G. et al. Drug-coated balloon versus standard percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for the treatment of superficial femoral and popliteal peripheral artery disease: 12-month results from the IN.PACT SFA randomized trial. Circulation 131 (5), 495–502. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011004 (2015).

Tepe, G. et al. Drug-Coated balloon treatment for femoropopliteal artery disease: the chronic total occlusion cohort in the IN.PACT global study. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 12 (5), 484–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2018.12.004 (2019).

Zeller, T. et al. Drug-Coated balloon treatment of femoropopliteal lesions for patients with intermittent claudication and ischemic rest pain. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 12 (1), e007730. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.007730 (2019).

Shishehbor Mehdi, H. et al. Comparison of Drug-Coated balloons vs Bare-Metal stents in patients with femoropopliteal arterial disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 81 (3), 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.10.016 (2023).

Yu, X. et al. One-year outcomes of drug-coated balloon treatment for long femoropopliteal lesions: a multicentre cohort and real-world study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 21 (1), 326. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02127-x (2021).

Scheinert, D. et al. Drug-Coated balloon treatment for femoropopliteal artery disease. Circulation: Cardiovasc. Interventions. 11 (10). https://doi.org/10.1161/circinterventions.117.005654 (2018).

Pan, J. et al. Protocol of the evolution study: A prospective, multicenter, observational study evaluating the effect and health economics of endovascular treatment in patients with moderate and severe calcification of femoropopliteal artery. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 1039313 (2022).

Rocha-Singh, K. J., Zeller, T. & Jaff, M. R. Peripheral arterial calcification: Prevalence, mechanism, detection, and clinical implications. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv.: Off. J. Soc. Card. Angiogr. Interv. 83, E212–220 (2014).

Beckman, J. A., Schneider, P. A. & Conte, M. S. Advances in revascularization for peripheral artery disease: revascularization in PAD. Circul. Res. 128 (12), 1885–1912. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318261 (2021).

Angel de Gregorio, M. et al. Drug-Coated balloon for the treatment of long-Segment femoropopliteal artery disease: pooled analysis from the BIOLUX P-III SPAIN and BIOLUX P-III All-Comers registry long lesion subgroup. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 34 (10), 1707–1715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2023.06.041 (2023).

Stavroulakis, K. et al. Intravascular lithotripsy and Drug-Coated balloon angioplasty for severely calcified femoropopliteal arterial disease. J. Endovasc. Ther. 30 (1), 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/15266028221075563 (2022).

Fanelli, F. et al. Calcium burden assessment and impact on Drug-Eluting balloons in peripheral arterial disease. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 37 (4), 898–907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-014-0904-3 (2014).

Hou, B. et al. Clinical implications of diverse calcification patterns in endovascular therapy for femoral-popliteal arterial occlusive disease. J. Vasc. Surg. 80 (1), 188–98e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2024.01.205 (2024).

Rocha-Singh, K. J., Zeller, T. & Jaff, M. R. Peripheral arterial calcification: prevalence, mechanism, detection, and clinical implications. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 83 (6), E212–E20. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccd.25387 (2014).

Soga, Y. et al. Vessel patency and associated factors of Drug-Coated balloon for femoropopliteal lesion. J. Am. Heart Association. 12 (1), e025677. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.122.025677 (2023).

Kaladji, A. et al. Impact of vascular calcifications on long femoropopliteal stenting outcomes. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 47, 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avsg.2017.08.043 (2018).

Berman Daniel, S., Arnson, Y. & Rozanski, A. Coronary artery calcium scanning. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging. 9 (12), 1417–1419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.05.020 (2016).

Aboyans, V. et al. 2017 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases, in collaboration with the European society for vascular surgery (ESVS): document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteriesendorsed by: the European stroke organization (ESO)The task force for the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases of the European society of cardiology (ESC) and of the European society for vascular surgery (ESVS). Eur. Heart J. 39 (9), 763–816. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx095 (2018).

Mohapatra, A. et al. Nationwide trends in drug-coated balloon and drug-eluting stent utilization in the femoropopliteal arteries. J. Vasc. Surg. 71 (2), 560–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2019.05.034 (2020).

Zenunaj, G. et al. Endovascular revascularisation versus open surgery with prosthetic bypass for Femoro-Popliteal lesions in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J. Clin. Med. 12 (18). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12185978 (2023).

Liistro, F. et al. Drug-Eluting balloon versus Drug-Eluting stent for complex femoropopliteal arterial lesions: the DRASTICO study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 74 (2), 205–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.04.057 (2019).

Bausback, Y. et al. Drug-Eluting stent versus Drug-Coated balloon revascularization in patients with femoropopliteal arterial disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73 (6), 667–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.039 (2019).

Zenunaj, G. et al. Primary Drug-Coated balloon versus Drug-Eluting stent for native atherosclerotic femoropopliteal lesions: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 92, 294–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avsg.2023.01.043 (2023).

Tarvainen, S. et al. Critical limb-threatening ischaemia and microvascular transformation: clinical implications. Eur. Heart J. 45 (4), 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad562 (2024).

Goswami, J. et al. A review of pathophysiology, clinical features, and management options of COVID-19 associated coagulopathy. Shock (augusta Ga,) 55, 700–716 (2021).

Smolderen, K. G., Lee, M., Arora, T., Simonov, M. & Mena-Hurtado, C. Peripheral artery disease and COVID-19 outcomes: insights from the Yale DOM-CovX registry. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 47 (12), 101007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2021.101007 (2022).

Jeger Raban, V. et al. Drug-Coated balloons for coronary artery disease. JACC: Cardiovasc. Interventions. 13 (12), 1391–1402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2020.02.043 (2020).

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (No, 2022-PUMCH-B-125), Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Science (No. 2022-I2M-C&T-A-002), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 82070498).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation were performed by Bao Liu and Jiang Shao, data collection and analysis were performed by Yuru Wang, Deqiang Kong and Kang Li. The first draft of the manuscript was written and revised by Yuru Wang, Yiyun Xie, and Zhichao Lai. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and approved the final revised manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The institutional review boards of Peking Union Medical College Hospital approved this study.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Li, K., Shao, J. et al. Two year comparative outcomes of drug coated balloons in long versus short femoropopliteal lesions. Sci Rep 15, 14165 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98773-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98773-8