Abstract

Fecal calprotectin (FC) is a biomarker of gut inflammation but its association with sepsis associated liver dysfunction (SALD) is unclear. This single-center, prospective cohort study investigated the relationship between FC and SALD in adults with sepsis. FC concentrations were measured on days 1 (FC1) and 3 (FC3). The difference between FC3 and FC1 (∆FC) was calculated. The relationship between FC and SALD was assessed using multivariate analysis. Receiver operating characteristic curves were used to assess the predictive value of SALD biomarkers. Ninety-five patients with sepsis (33 with SALD and 62 without SALD) were enrolled between January 2023 and March 2024. The median FC3 level and ∆FC were significantly higher in the SALD group than in the non-SALD group (both p < 0.001), whereas the median FC1 level did not differ significantly between groups. FC3 level and ∆FC were positively associated with SALD in the adjusted analysis (both p < 0.001) with areas under the curve of 0.784 and 0.848, respectively, and cut-off values of 930.88 μg/g and − 8.80 μg/g, respectively. In adults with sepsis, SALD occurrence was more strongly associated with elevated FC3 levels and ∆FC than with FC1 levels; therefore, monitoring FC3 levels and ∆FC could help detect SALD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the Sepsis 3.0 definition, sepsis is a clinical syndrome resulting from a disordered host response to severe infections, often leading to multiple organ dysfunction.1 Among the various complications of sepsis, sepsis associated liver dysfunction (SALD) is one of the most frequent, posing significant morbidity and mortality risks.2

The gut and the liver have a close relationship, known as the gut-liver axis, with bidirectional interactions.3 In the case of sepsis, systemic inflammation and hypoperfusion play a crucial role in the pathophysiological processes of acute gastrointestinal injury (AGI).4 AGI-associated gut barrier injury can lead to the translocation of bacteria and toxins into the liver through the portal circulation and the lymphatic system, leading to SALD. Our previous study found a higher incidence of AGI in patients with SALD than in those without SALD.5

Fecal calprotectin (FC) is a convenient, non-invasive biomarker that exhibits a strong correlation with gut inflammation.6 Its concentration is proportional to neutrophil migration to the gut and correlates well with fecal leukocyte excretion.7 A study observed significantly higher FC concentrations in patients with sepsis complicated by AGI than in those without sepsis, suggesting its potential as an early diagnostic indicator for AGI.8 However, the relationship between FC and SALD remains unclear. Therefore, we conducted this prospective study to explore the potential association between FC concentration and SALD in adults with sepsis. Furthermore, the dynamic changes of FC from days 1 to 3 after enrollment were also investigated in our cohort prior to the onset of SALD.

Results

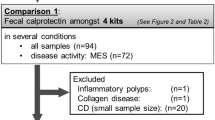

Clinical characteristics of study participants

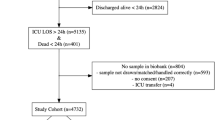

A total of 152 patients with sepsis were screened for inclusion. After exclusions, 95 patients were included in the final analysis, with 33 and 62 in the SALD and non-SALD groups, respectively (Fig. 1).

Patients in the SALD group had significantly higher Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores and intensive care unit (ICU) mortality rates than those in the non-SALD group (Table 1). Other characteristics, including age, sex, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, comorbidities, medications used, complications, infection sites, and ICU length of stay (LOS), did not differ significantly between the two groups.

FC and laboratory indicators on days 1 and 3

The white blood cell (WBC) and neutrophil counts were significantly higher in the SALD group than in the non-SALD group on days 1 and 3. The platelet count was significantly lower on day 1, and procalcitonin and interleukin (IL)-6 levels were significantly higher on day 3 in the SALD group than in the non-SALD group. No significant differences were observed between the non-SALD and SALD groups in the lymphocyte count, or procalcitonin, C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-6, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-8, IL-10, IL-17, interferon (IFN)-α, IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, D-dimer, B-type natriuretic peptide(BNP), platelet, albumin, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR levels on day 1; or the lymphocyte count and CRP level on day 3 (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

The median FC1 in the SALD and non-SALD groups was 520.00 μg/g and 342.00 μg/g, respectively, with no significant differences between the two groups (p > 0.05). However, the median FC3 was significantly higher in the SALD group (967.21 μg/g) than in the non-SALD group (252.35 μg/g; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2a). Both the median ∆FC and ∆FC percentage were significantly higher in the SALD group (200.42 μg/g and 56.00%) than those in the non-SALD group ( − 137.93 μg/g and − 36.40%; p < 0.001) (Table 2). From day 1 to day 3, the FC increased by a mean of 212.75 μg/g (95% confidence interval [CI]: 13.46–412.04 μg/g) more in the SALD group than in the non-SALD group (p = 0.029) (Table 3). Additionally, the FC3 was significantly higher in patients with septic shock and AGI than in those without (Fig. 2b, c). However, no significant differences in FC3 were observed between patients with and without respiratory failure, or with and without acute kidney injury (AKI) (Fig. 2d, e).

FC concentration in patients with sepsis. (a) comparison of FC concentrations according to SALD status groups on days 1 and 3; (b) comparison of FC concentrations between patients with and without septic shock; (c) comparison of FC concentrations between patients with and without AGI; (d) comparison of FC concentrations between patients with and without respiratory failure; (e) comparison of FC concentrations between patients with and without AKI. AGI, acute gastrointestinal injury; AKI, acute kidney injury; FC, fecal calprotectin; SALD, sepsis associated liver dysfunction. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The APACHE II (r = 0.620; p < 0.001) and SOFA (r = 0.612; p < 0.001) scores were positively correlated with the FC1 level (Figs. 3a, b). The WBC count, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count and procalcitonin level on day 1 were not significantly correlated with FC1 (Fig. 3c–f). The CRP (r = 0.686; p < 0.001) and IL-6 (r = 0.530; p < 0.001) levels on day 1 were positively correlated with the FC1 level (Fig. 3g, h). The FC3 level was not correlated with the WBC, neutrophil, or lymphocyte counts on day 3 (Fig. 3i–k), but were weakly correlated with the procalcitonin (r = 0.370; p < 0.001), CRP (r = 0.333; p < 0.001), and IL-6 (r = 0.425; p < 0.001) levels (Fig. 3l–n).

Correlation between FC concentration and clinical parameters. (a) scatter plot of FC1 concentration and APACHE II score; (b) scatter plot of FC1 concentration and SOFA score; (c) scatter plot of FC1 concentration and WBC count on day 1; (d) scatter plot of FC1 concentration and neutrophil count on day 1; (e) scatter plot of FC1 concentration and lymphocyte count on day 1; (f) scatter plot of FC1 concentration and procalcitonin on day 1; (g) scatter plot of FC1 concentration and C-reactive protein on day 1; (h) scatter plot of FC1 concentration and IL-6 on day 1; (i) scatter plot of FC3 concentration and WBC count on day 3; (j) scatter plot of FC3 concentration and neutrophil count on day 3; (k) scatter plot of FC3 concentration and lymphocyte count on day 3; (l) scatter plot of FC3 concentration and procalcitonin on day 3; (m) scatter plot of FC3 concentration and C-reactive protein on day 3; (n) scatter plot of FC3 concentration and IL-6 on day 3. FC, fecal calprotectin; APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; WBC, white blood cell; IL-6, interleukin 6.

In the non-SALD group, the FC concentration decreased significantly from day 1 to day 3 (p < 0.001; Fig. 4a), with a median ∆FC of − 137.93 μg/g. In contrast, the FC concentration increased significantly from day 1 to day 3 in the SALD group (p < 0.001; Fig. 4b), with a median ∆FC of 200.42 μg/g. The ∆FC differed significantly between the non-SALD and SALD groups (p < 0.001). Patients with ∆FC > 0 had a significantly higher incidence of SALD and ICU mortality than those with ∆FC ≤ 0 (Fig. 4c, 4d).

∆FC concentration in patients with sepsis. (a) ∆FC concentration in patients without SALD; (b) ∆FC concentration in patients with SALD; (c) the incidence of SALD in patients with ∆FC ≤ 0 and > 0; (d) the mortality in patients with ∆FC ≤ 0 and > 0. ∆FC, change in fecal calprotectin between days 1 and 3; SALD, sepsis associated liver dysfunction. ***p < 0.001.

Association between FC3, ∆FC, and SALD occurrence

Three logistic regression models were constructed to assess the independent association between FC3, ∆FC, and SALD occurrence. When FC3 level was analyzed as a continuous variable, a higher FC3 level was associated with an increased incidence of SALD in all three models (Model 1: odds ratio [OR] 1.00, 95% CI 1.00–1.01, p < 0.001; Model 2: OR 1.00, 95% CI 1.00–1.01, p < 0.001; and Model 3: OR 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.01, p < 0.001). When FC3 was categorized as tertiles, compared with the first tertile of FC3, the adjusted ORs for SALD incidence were 5.23 (95% CI 1.04–26.27) for the second tertile and 9.07 (95% CI 1.81–45.41) for the third tertile. The p-value for the trend of FC3 with categorical variables in the fully adjusted model was consistent with the results reported when FC3 was treated as a continuous variable.

Furthermore, a higher ∆FC value was associated with an increased incidence of SALD in all three models when ∆FC was treated as a continuous variable (Model 1: OR 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.01, p < 0.001; Model 2: OR 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.01, p < 0.001; and Model 3: OR 1.01, 95% CI 1.01–1.01, p < 0.001). Compared with ∆FC ≤ 0, the adjusted OR for SALD occurrence was 22.37 (95% CI 4.31–116.01) for ∆FC > 0 (Table 4).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of FC3 and ∆FC for SALD occurrence

The effectiveness of FC3 and ∆FC in predicting SALD occurrence was analyzed using the ROC curve. The cut-off value for FC3 was 930.88 μg/g and − 8.80 μg/g for ∆FC. The sensitivity was 51.52% and 90.91% for FC3 and ∆FC, respectively. The specificity was 98.39% and 72.58% for FC3 and ∆FC, respectively. The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.784 (95% CI 0.687–0.881) for the FC3 level and 0.848 (95% CI 0.770–0.927) for ∆FC. The positive predictive values were 94.44% for the FC3 level and 63.83% for ∆FC, with negative predictive values of 79.22% and 93.75%, respectively (Fig. 5).

Discussion

This study is the first to investigate the relationship between FC concentration and SALD in adult patients with sepsis. The results revealed that dynamic changes in FC concentration from days 1 to 3 were associated with SALD occurrence. This suggests that monitoring FC concentration dynamically is more effective than single FC measurements for the early detection of SALD occurrence in sepsis. Moreover, only the APACHE II score, SOFA score, and CRP and IL-6 levels were correlated with FC1.

Calprotectin, a calcium- and zinc-binding protein derived from neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages, is an important biomarker of acute inflammatory cell activation.9,10 The protein is a heterodimer composed of S100A8 and S100A9, and widely distributed throughout the human body, including in cells, tissues, and body fluids, with varying concentrations at different locations.11 Once inflammatory injury to the gut mucosa occurs, FC begins to rise and can persist for about 7 days at room temperature. FC concentration, more accurate and sensitive than serum calprotectin, reflects gut mucosa inflammation and exudation owing to the direct contact of stool with the gut mucosa. Clinically, FC aids in differentiating organic intestinal diseases from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and in assessing IBD activity index.6,12.

However, relevant studies on patients with sepsis are limited and yield inconsistent results. Li et al.8 performed a prospective analysis of 54 adult patients with sepsis and 15 healthy volunteers. They observed significantly higher FC concentration in sepsis patients with AGI than those without AGI and healthy volunteers. FC concentration had a significant positive correlation with serum D-lactic acid, serum IL-6 levels, and APACHE II and SOFA scores. ROC analysis indicated a moderate predictive power of FC for AGI, with an AUC of 0.74, a sensitivity of 62.80%, and a specificity of 76%. An earlier study by Effenberger et al.13 found significantly higher FC concentrations in both patients with COVID-19 and resolved diarrhea (symptom disappearance > 48 h at inclusion) and those with acute diarrhea (symptom onset < 48 h at inclusion) than in patients without diarrhea. Additionally, a significant positive correlation was observed between FC concentration and serum IL-6 levels but no significant correlation with CRP or ferritin levels. Another study observed significantly elevated FC concentrations in patients with COVID-19 compared with healthy controls, with notable differences among patients with COVID-19 according to disease severity.14 However, FC concentrations did not differ significantly between COVID-19 patients with and without gastrointestinal symptoms, nor among those with different gastrointestinal symptoms. Among patients with COVID-19 with and without diarrhea, FC concentration also showed no significant difference. The authors attributed this finding to the non-inflammatory nature of diarrhea in COVID-19, primarily caused by viral etiology rather than inflammatory mechanisms, supported by the absence of fecal leukocytes in samples from patients with diarrhea.

It is widely recognized that the gut and liver engage in intricate bidirectional communication known as the “gut-liver” axis.3 Under septic conditions, hypoperfusion and inflammation are the two primary causes of AGI, characterized by gut barrier dysfunction, gut flora disorder, and bacterial translocation.15 Bacterial pathogens and toxins translocate from the gut lumen into the blood circulation and subsequently enter the liver through the portal vein, resulting in hepatic impairment.16 Among these pathogenic factors, lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which is produced by approximately 100 trillion microorganisms in the gut, amounting to > 1 g/d, plays a specific role. In cases of sepsis, inflammation adversely affects the components of the gut barrier, as evidenced by the dysregulation of intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis. This leads to the gradual failure of luminal defense mechanisms that typically prevent excessive transfer of LPS into the systemic circulation. Consequently, the transmigration of LPS to various organs, including the liver, increases leading to uncontrolled immunoinflammatory responses. Gut-derived pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) are two other factors that enter the liver via the portal vein or biliary tract. PAMPs are identified by effector cells located within the hepatic vasculature, thereby establishing a network of immune surveillance. DAMPs engage and activate Toll-like receptors on hepatic macrophages and other cell types. Together, these pathogenic factors serve as critical triggers that can precipitate maladaptive immune responses or excessive inflammation, leading to compromised elimination of pathogenic hepatic bacteria, contributing to metabolic disturbances. The imbalance of gut microbiota significantly contributes to the activation of immune responses and enhances the permeability of the intestinal barrier. Short-chain fatty acids, which serve as important metabolic products of bacterial activity, play a vital role in maintaining immune homeostasis, enhancing the structural integrity of the intestinal barrier, and promoting the maturation of regulatory T cells.3,17 However, the mechanisms by which the intestine affects liver function during sepsis require further investigation.

Kuang et al.18 designed a mouse model of gut-origin sepsis using the cecal ligation and perforation method and observed pronounced bacterial translocation, elevated serum pro-inflammatory factors, and decreased serum anti-inflammatory factors in the model group than in the sham group. This model group also exhibited significant liver injury, as evidenced by serum liver function indicators and hematoxylin and eosin staining of the liver tissue. Liang et al.19 investigated the effects of metformin on the liver in a SALD model of aged rats. They reported that metformin alleviated colonic inflammation, decreased gut barrier dysfunction, normalized intestinal flora, and ameliorated liver injury. Another study examined the effect of terlipressin on the gut-vascular barrier in a mouse model of sepsis.20 The results demonstrated that terlipressin attenuated gut-vascular barrier damage, as observed by decreased expression of intestinal plasmalemma vesicle-associated protein-1 and vascular endothelial-cadherin. Furthermore, terlipressin decreased the translocation of gut macromolecules and bacteria, along with the downregulation of inflammatory factors in liver tissue. Despite these findings, clinical studies on the gut and SALD are limited.

Our previous study revealed a higher incidence of AGI among patients with abdominal infections and SALD than in those without SALD, showing a severity-dependent relationship between AGI grade and SALD occurrence.5 Additionally, patients with SALD exhibit persistent gut flora disorders during the first week. In the current study, we excluded patients who developed SALD within 72 h of enrollment, which was the time window for FC measurement. This approach aimed to minimize the effects of SALD on the gut, primarily through disrupted immune-inflammatory responses, impaired bacterial clearance, and bile acid secretion, which contribute to gut inflammation and subsequent FC elevation. In addition, medications that directly or indirectly affect FC levels were also considered. Administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is known to be associated with a moderate elevation in FC levels; however, this typically takes several days of treatment to manifest.21 Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are another important class of drugs that influence FC levels. Lundgren et al.22 conducted a cohort study of 1,263 patients undergoing colonoscopy and found that PPI use was significantly associated with increased FC levels. The administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics can potentially suppress the growth of sensitive gut microorganisms, promoting the proliferation of drug-resistant bacteria. This process ultimately contributes to the disruption of the gut microbiota and increases gut bacterial translocation.23 Although this can affect FC concentrations, it typically takes a few days for antibiotic administration to have an effect.24.

The results showed no significant difference in FC1 between patients who developed SALD and those who did not. However, both FC3 and ∆FC were significantly higher in patients with SALD than in those without SALD. These results indicate a persistent exacerbation of gut inflammatory injury in patients with SALD during the early stages, whereas patients without SALD experience some degree of relief from gut inflammation. Therefore, persistent gut inflammation might be an important factor contributing to SALD occurrence.

This study has some limitations. First, none of patients had indicators reflecting gut barrier function and microbiota. Second, for economic reasons, we monitored FC concentrations only on days 1 and 3 after inclusion rather than daily or over a longer time frame. This may have resulted in the omission of some important information. Third, the sample size was relatively small, mainly because this was a single-center study. Further multicenter, large-sample prospective cohort studies are required to assess the generalizability of our findings.

Conclusions

Dynamic changes in FC concentration from days 1 to 3 were closely associated with SALD occurrence in adult patients with sepsis. In the future, monitoring these dynamic changes in FC concentrations may be a better way to detect the occurrence of SALD.

Methods

Study participants

This single-center prospective cohort study enrolled consecutive adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) with sepsis, admitted to the Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital between January 2023 and March 2024. The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (number: 2023-396-03). All patients or their immediate family members provided informed consent, and all study procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) Patients with gastrointestinal diseases such as gastrointestinal malignancies and IBD; (2) Patients with severe chronic liver diseases such as Gilbert syndrome, decompensated cirrhosis and advanced liver cancer; (3) Patients hospitalized for primary hepatobiliary disease, such as trauma, hepatitis, and hepatic abscess; (4) Patients already diagnosed with SALD at enrollment; (5) Patients discharged or deceased within 72 h after enrollment; and (6) Pregnant individuals.

All eligible patients were treated according to the Sepsis 3.0 guidelines, including managing the source of infection, early administration of antibiotics, and other supportive therapies to preserve organ function. Patients were followed through the entire ICU stay. The patients were divided into non-SALD and SALD groups according to whether SALD was diagnosed during their ICU stay. Patients were also excluded if the following occurred during the study period: (1) Deviation from the study protocol for any reason; (2) Presence of other causes of liver injury, such as drugs and poisons; (3) Diagnosis of SALD within 72 h after enrollment; or (4) Decisions by the patients or their relatives to withdraw from the study.

Data collection and outcomes

The primary study outcome was the FC concentration (< 50.00 μg/g), which reflects the severity of gut inflammation. Fecal samples (5–10 g) were collected from patients in sterile tubes on days 1 and 3 after enrollment and stored at 4 °C. Approximately 100 mg of fecal matter was homogenized in 5 mL of an extraction buffer (1:49), followed by centrifugation of the suspension at a force of 3000 × g for 5 min. An aliquot of 100 μL of supernatant was extracted with a pipette gun and diluted to 1:50. Using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates (EK-CAL, Bühlmann Laboratories AG, Schönenbuch, Switzerland), procedures were conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with a range spanning from 50 to 1000 µg/g, and each sample was repeated three times. The optical density values were ultimately read at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Inflammatory markers in the serum, including IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17, IFN-α, IFN-γ and TNF-α, were quantified using flow cytometry, according to the manufacturer’s protocols (EasyCell, Hangzhou Biogroup Technology Co., Ltd., Zhejiang, China). Blood cell and platelet counts were performed using a blood analyzer (XN-9000, Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan). Transaminases, bilirubin, albumin and CRP were quantified using a biochemical analyzer (AU 5800, Beckman Corporation, Brea, CA, USA); D-dimer levels were quantified using an automated coagulation analyzer (Sysmex CS-5100, Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan); procalcitonin levels were quantified using an automatic chemiluminescence immunoanalyzer (Cobas C8000; Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland); BNP levels were quantified using a fluorescence immunoassay (Triage MeterPro, Quidel Corporation, San Diego, CA, USA); and HLA-DR expression was quantified using flow cytometry (FACSort, BD Corporation, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and CellQuest software (BD Corporation).

The following information was collected within the first 24 h of enrollment: demographic characteristics (age and sex); comorbidities; source of infection; disease severity scores, including APACHE II score and SOFA score; medications, including NSAIDs, PPIs, antibiotics and corticosteroids; complications such as respiratory failure, septic shock, AKI, and AGI; levels of inflammatory factors; and other indicators including HLA-DR, albumin, BNP, D-dimer levels and platelet count. The following indicators were assessed on days 1 and 3 after enrollment: WBC count, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, CRP, procalcitonin, and IL-6. Additionally, prognostic indicators, including ICU LOS and ICU mortality, were recorded.

Definitions

According to the Sepsis 3.0 guidelines,1 sepsis was diagnosed in individuals who either had verified or suspected sources of infection accompanied by a concurrent SOFA score ≥ 2. Septic shock was defined by the presence of sustained hypotension (such as systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg, mean arterial pressure < 65 mmHg, or blood lactate level ≥ 2 mmol/L), despite sufficient fluid resuscitation and vasopressor administration to maintain the mean arterial pressure ≥ 65 mmHg in individuals diagnosed with sepsis. SALD was diagnosed when patients met either of the following criteria in the context of sepsis after excluding other potential sources of liver injury:25 (1) Serum aminotransaminase levels, including alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase level > 800 IU/L; or (2) Total bilirubin > 2 mg/dL. AKI was diagnosed according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KIDIGO) clinical practice guidelines.26 AGI was diagnosed according to the 2012 European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) recommendations.27 The abbreviation “FC1” represented the FC concentration on day 1; “FC3” represented the concentration on day 3; “ΔFC” represented the difference between FC3 and FC1; and the percentage of ΔFC was calculated by dividing ΔFC by FC1 and multiplying by 100.

Statistical analysis

For all continuous variables, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test for normality of the distribution. Normally distributed continuous variables were reported as the mean ± standard deviation, and non-normally distributed continuous variables were reported as the median (interquartile range [IQR]). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to assess the statistical significance of within-group comparisons, whereas the independent samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test was used for comparisons of normally distributed and non-normally distributed continuous variables between different groups, respectively, as appropriate. Categorical data were expressed as absolute values (ratios) and were compared using the chi-squared test. Comparisons of the FC concentrations between the groups at various timepoints were assessed using generalized estimation equations. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the association between FC3, ΔFC, and SALD occurrence. Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex; Model 2 was adjusted for the variables in Model 1, plus the APACHE II and SOFA scores. Model 3 was adjusted for the variables in Model 2, plus the WBC count on days 1 and 3, neutrophil count on days 1 and 3, platelet count on day 1, procalcitonin level on day 3, and IL-6 level on day 3. ROC curves and AUCs were used to evaluate the ability of FC3 and ΔFC levels to identify SALD. All analyses were performed using the R statistical software package (http://www.R-project.org, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and Free Statistics software version 1.9. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article.

Change history

02 June 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in affiliation 1, which was incorrectly given as ‘Department of Critical Care Medicine, Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University, No. 321 Zhongshan Road, Nanjing 210008, Jiangsu Province, China’. The correct affiliation is ‘Department of Critical Care Medicine, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, Nanjing University, No. 321 Zhongshan Road, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China’.

References

Singer, M. et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315, 801–810 (2016).

Kobashi, H. et al. Sepsis-associated liver injury: Incidence, classification and the clinical significance. Hepatol. Res. 43, 255–266 (2013).

Sun, J. et al. Gut-liver crosstalk in sepsis-induced liver injury. Crit. Care 24, 614 (2020).

Habes, Q. L. M. et al. Norepinephrine contributes to enterocyte damage in septic shock patients: A prospective cohort study. Shock 49, 137–143 (2018).

Zhang, B. et al. Acute gastrointestinal injury and altered gut microbiota are related to sepsis-induced cholestasis in patients with intra-abdominal infection: A retrospective and prospective observational study. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 10, 1144786 (2023).

Dajti, E. et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Diagnostic performance of faecal calprotectin in distinguishing inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome in adults. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 58, 1120–1131 (2023).

Montalto, M. et al. Role of fecal calprotectin in gastrointestinal disorders. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 17, 1569–1582 (2013).

Li, J. et al. Evaluation of fecal calprotectin, D-lactic acid and bedside gastrointestinal ultrasound image data for the prediction of acute gastrointestinal injury in sepsis patients. Front. Med. Technol. 3, 733940 (2021).

Dale, I. et al. Purification and partial characterization of a highly immunogenic human leukocyte protein, the L1 antigen. Eur. J. Biochem. 134, 1–6 (1983).

Kapel, N. et al. Faecal calprotectin in term and preterm neonates. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 51, 542–547 (2010).

Averill, M. M. et al. S100A8 and S100A9 in cardiovascular biology and disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 223–229 (2012).

Lichtenstein, G. R. et al. ACG clinical guideline: Management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 113, 481–517 (2018).

Effenberger, M. et al. Faecal calprotectin indicates intestinal inflammation in COVID-19. Gut 69, 1543–1544 (2020).

Shokri-Afra, H. et al. Elevated fecal and serum calprotectin in COVID-19 are not consistent with gastrointestinal symptoms. Sci. Rep. 11, 22001 (2021).

Magnan, C. et al. Role of gut microbiota and bacterial translocation in acute intestinal injury and mortality in patients admitted in ICU for septic shock. Front Cell Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1330900 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. The gut-liver axis in sepsis: Interaction mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Crit. Care 26, 213 (2022).

Lou, X. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation and short-chain fatty acids reduce sepsis mortality by remodeling antibiotic-induced gut microbiota disturbances. Front Immunol. 13, 1063543 (2023).

Kuang, Z. et al. Lentinan attenuates damage of the small intestinal mucosa, liver, and lung in mice with gut-origin sepsis. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2052757 (2021).

Liang, H. et al. Metformin attenuated sepsis-related liver injury by modulating gut microbiota. Emerg Microbes Infect. 11, 815–828 (2022).

Chang, Z. et al. Improvement of gut-vascular barrier by terlipressin reduces bacterial translocation and remote organ injuries in gut-derived sepsis. Front Pharmacol. 13, 1019109 (2022).

Lężyk-Ciemniak, E. et al. Usefulness of testing for fecal calprotectin in pediatric gastroenterology clinical practice. Med. Princ. Pract. 30, 311–319 (2021).

Lundgren, D. et al. Proton pump inhibitor use is associated with elevated faecal calprotectin levels. A cross-sectional study on subjects referred for colonoscopy. Scand J. Gastroenterol. 54, 152–157 (2019).

Weersma, R. K. et al. Interaction between drugs and the gut microbiome. Gut 69, 1510–1519 (2020).

Tong, G. et al. Intestinal flora imbalance induced by antibiotic use in rats. J. Inflamm. Res. 17, 1789–1804 (2024).

Strnad, P. et al. Liver - Guardian, modifier and target of sepsis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 55–66 (2017).

Khwaja, A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron. Clin. Pract. 120, c179–c184 (2012).

Reintam Blaser, A. et al. Gastrointestinal function in intensive care patients: Terminology, definitions and management. Recommendations of the ESICM working group on abdominal problems. Intens. Care Med. 38, 384–394 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Funding

This work was supported by the China International Medical Foundation (Grant No. N-2021-15-13) and Funding for clinical trials from the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University (Grant No. 2023-LCYJ-PY-30).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Beiyuan Zhang: Study concept and design, methodology, investigation, writing and revising manuscript; Chenzhe He: Investigation, Validation, writing original manuscript; Ting Su and Zimeng Qin: Collection and assembly of data, writing original manuscript; Zhanghua Zhu: English editing; Qi Cheng: Analysis and interpretation of the data; Ming Chen: Verification of data; Wenkui Yu: Study concept and study design, article revision, and article approval. Beiyuan Zhang and Chenzhe He contributed equally to this work. All authors read and approved the final version for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital. Written informed consent for participation in the study has been obtained from the patients or participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, B., He, C., Su, T. et al. Association and dynamic change of fecal calprotectin with sepsis associated liver dysfunction in adults with sepsis. Sci Rep 15, 16192 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98904-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98904-1