Abstract

This study investigates the uplift capacity of circular anchors embedded in frictional-cohesive soils under surcharge. The analysis focuses on three critical stability factors Fc, Fq, and Fγ using Terzaghi’s principle of superposition to evaluate ultimate bearing capacity. These factors are influenced by the soil’s internal friction angle, the geometric ratio of anchor depth to diameter, and the interface roughness between the anchor and soil. Three predictive models for these stability factors are developed using advanced computational methods, including finite element limit analysis (FELA) with adaptive meshing and Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN). This research is the first to apply KAN in anchor behavior studies, demonstrating its enhanced ability to model complex data relationships compared to artificial neural networks (ANN). Additionally, a closed-form solution for stability factors is derived through KAN, providing an efficient method for predicting bearing capacity. The optimized models exhibit high coefficient of determination (R²) values and low root mean square errors (RMSE) for training and testing datasets. Sensitivity analysis validates the robustness of the proposed models. These findings advance the understanding of circular anchors’ bearing capacity in frictional-cohesive soils, offering practical design insights for various soil conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil anchors play a crucial role in modern engineering and come in various shapes, including square, circular, and rectangular designs. These anchors provide uplift resistance to the foundations of critical infrastructure, such as transmission towers and sheet pile walls. They also offer cost-effective mooring solutions for offshore oil and gas platforms1. As the demands on these anchors grow with the support of increasingly large and complex structures, a deeper understanding of their behavior becomes essential. Moreover, the principles of soil uplift resistance can be applied to broader geotechnical challenges. For instance, these principles can be adapted to model submerged pipelines or buried foundations, even in the absence of direct anchoring2. Thus, a comprehensive understanding of anchor behavior and soil interactions is vital for optimizing anchor designs.

Over the past three decades, research into the uplifting capacity of horizontal anchors in clay has predominantly relied on experimental and empirical methods. Early contributions include Vesić3 who provided analytical solutions based on tests of circular anchors. Meyerhof and Adams4 and Meyerhof5 followed with break-out factors derived from similar experimental setups. However, these models were constrained by their simplifying assumptions regarding failure mechanisms and soil behavior6,7,8. While these foundational studies have been crucial, they have often been constrained by their reliance on two-dimensional analyses.

Numerical analyses in soil mechanics often employ plane strain conditions, which may not accurately capture the behavior of anchors with varying shapes and loading conditions9. This limitation has been partly addressed by more recent advancements, such as the work of Yu10, which offers more refined models for cohesive soils. Although laboratory investigations by Das et al.11,12 and Baba et al.13 examined various anchor types and conditions, detailed three-dimensional numerical models are still limited. Additionally, while finite element studies by Rowe and Davis14 and others have provided valuable insights, comprehensive three-dimensional analyses are still lacking.

A significant research gap exists in developing a unified approach that incorporates internal friction angles, soil cohesion, interface roughness, and surcharge loading into stability analyses. This study aims to address this gap by examining the uplift behavior of horizontal anchor plates in frictional-cohesive soil using Terzaghi’s superposition method15. By employing Finite Element Limit Analysis (FELA) with adaptive meshing techniques, this research investigates the uplift capacity of circular anchors in various soil types, taking into account the effects of cohesion, friction, and surcharge. The goal is to provide new insights and enhance practical applications of seismic design principles in geo-structural design.

The upper and lower bound methods, originally developed by Drucker et al.16, are foundational to stability analysis in soil mechanics, especially for perfectly plastic materials. These methods have been applied to various stability problems, including trapdoor stability, slope stability, foundation bearing capacity, and underground tunneling stability17,18,19,20,21. The lower bound theorem ensures that if an equilibrium stress distribution can be found that balances external loads without exceeding the material’s yield limit, it provides a conservative estimate of collapse loads. Traditionally, these methods have been applied to two-dimensional problems using linear programming techniques17,22. However, recent advancements, including Lyamin’s three-dimensional lower bound nonlinear procedure23, extend these techniques to address more complex stability issues in three dimensions.

Recent research highlights the adaptation of Terzaghi’s capacity formula to various stability challenges, as demonstrated by Nguyen and Shiau24, Shiau et al.15. Their work introduces a comprehensive approach using three stability factors (Fc, Fq, and Fγ) to evaluate both static and seismic loads. These factors, consistent with Terzaghi’s framework, provide a unified method for assessing limit loads under seismic conditions. This approach integrates various factors, including soil properties, surcharge loading, seismic impacts, and wall roughness, facilitating a detailed analysis of ground anchor uplift behavior. Unlike other studies25,26,27, Shiau et al.15 present dimensionless factors that enhance practical design applications for plate anchors subjected to seismic loading. However, this approach has not yet been applied to axisymmetric anchors in frictional-cohesive soil with surcharge loading. This study seeks to bridge this gap.

Recent advances in soft computing, particularly in machine learning and artificial neural networks (ANNs), have significantly revitalized geo-structural design. However, traditional ANN architectures, such as Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs), are frequently characterized as “black box” models, making it challenging to interpret how inputs influence the output. Building upon the Kolmogorov-Arnold representation theorem, Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KANs)28,29 address this limitation by providing closed-form representations of complex nonlinear relationships. Whereas MLPs rely on fixed activation functions within each node, KANs employ learnable spline-based activation functions on edges, effectively replacing linear weights with functions that can adapt to underlying data structures. This design reduces the total number of parameters, mitigates overfitting, and enhances interpretability by offering deeper insights into how each input variable interacts within the model. As demonstrated by Liu et al.30, KANs can achieve or surpass the accuracy of MLPs while maintaining a faster neural scaling and providing transparent analytical insights through more intuitive visualizations. Building on these theoretical and practical advantages, this study employs KAN to predict three key stability factors in uplift capacity assessment for frictional-cohesive soils, offering a robust and more interpretable alternative to conventional ANN-based methods.

In summary, this study introduces Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KANs) to assess the uplift capacity of circular anchors in frictional-cohesive soil with surcharge. By applying KANs to model the three stability factors obtained from advanced limit analyses, the research enhances understanding of anchor performance and quantifies the impact of each parameter. This novel approach would greatly support more precise and optimal design solutions. Additionally, the study aims to develop a closed-form mathematical solution, simplifying hand calculations and improving practical design efficiency in engineering applications. The overall methodology follows a structured five-step process: (1) FELA simulations are performed to quantify anchor uplift behavior; (2) a comprehensive dataset is constructed from the simulation outputs; (3) KAN models are trained to capture nonlinear interactions among input variables; (4) closed-form expressions for stability factors are derived; and (5) engineering interpretations are extracted to guide design decisions. This approach not only addresses current research gaps but also advances the field of geo-structure design by integrating innovative modeling techniques with practical design considerations.

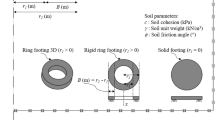

Problem formulation and FELA model

The problem definition of a circular anchor under axial symmetry is presented in Fig. 1. In the stability design context of a rigid anchor, the key design parameters include the diameter (D), the buried depth (H), the width of the anchor (D), and the surcharge pressure (q). The backfill soil is characterized by cohesion (c), internal friction angle (φ), and unit weight (γ), following the Mohr-Coulomb failure criterion. The interaction between the anchor and the soil is represented by a roughness factor , which varies discrete values: 0 (perfectly smooth) to 1/3; ½; 2/3, and 1 (perfectly rough). These values indicate varying degrees of friction between the anchor and the surrounding soil, affecting the anchor’s uplift resistance.

To assess the effects of cohesion, surcharge, and soil weight, respectively, three stability factors (Fc, Fq, and Fγ) are calculated using various input parameters, including the depth-to-width ratio (H/D) and the internal friction angle of the soil (φ). The uplift capacity (Pu) of the circular anchor is determined using a method similar to Terzaghi’s bearing capacity formula. Using the three anchor factors, the uplift capacity (Pu) can be determined through Eq. (1):

where c represents the effective cohesion, denotes the magnitude of potential surcharge loading on the ground surface, is the unit weight of the soil. D is the diameter of the circular anchor, as previously stated. It is important to note that these three factors are functions of the embedment depth-to-width ratio (H/D) and the internal friction angle (φ).

As extensively discussed and validated by Shiau et al.15 using Terzaghi’s principle of superposition, to determine the factor Fc, the analysis begins by setting both the unit weight (γ = 0) and surcharge pressure (q = 0) to zero. Factor Fc is then computed using the simplified form of Eq. (1):

Similarly, for calculating the factor Fq, cohesion (c = 0) and unit weight (γ = 0) are set to zero in Eq. (1). The factor Fq is then derived using the reduced equation :

In parallel, to find the factor Fγ, cohesion (c = 0) and surcharge pressure (q = 0) are both set to zero in Eq. (1), allowing the calculation of Pu. With this value established, Fγ is computed using the simplified equation:

Figure 2 is a typical example of an adaptive mesh for the anchor uplift force problem (H/D = 5). This study employs plastic limit theorems using both upper bound (UB) and lower bound (LB) techniques. The UB method identifies plastic deformation patterns where external work exceeds internal plastic dissipation, indicating collapse, while the LB method seeks an equilibrium stress distribution that satisfies yield criteria. The problem is governed by standard boundary conditions: the two side boundaries are constrained in the normal direction, while the bottom boundary is fixed in both the x and y directions. More details of the adaptive meshing technique of FELA formulations can be found in Ali et al.31, and they will not be repeated here.

Adaptive meshing plays a crucial role in capturing the nonlinear failure mechanisms associated with anchor uplift, especially at deeper embedments where localized shear bands and curved rupture surfaces dominate. By dynamically refining mesh density around zones of high stress gradients, adaptive meshing improves the accuracy of collapse load predictions while maintaining computational efficiency. This refinement process is critical in both upper and lower bound limit analyses, as mesh quality directly affects the convergence and reliability of the computed bounds. In all numerical simulations presented in this study, three iterations of adaptive meshing were performed, yielding a final mesh with approximately 10,000 elements. This exceeds the typical recommendation of 3000 to 5000 elements in OptumG2, thereby enhancing the robustness and resolution of the limit analysis results. The soil was modeled using a Mohr-Coulomb perfectly plastic material model with associated flow rules.

Analyzing the stability factors: F c, F q, and F γ

In this section, the influence of stability factors on the uplift capacity of anchors is examined through various failure mechanisms and embedment ratios (H/D). The analysis considers the failure mechanisms associated with Fc, Fγ, and Fq under different embedment conditions and soil parameters. The numerical results for the cohesion factor (Fc), surcharge factor (Fq), and unit weight factor (Fγ), along with their upper bound (UB) and lower bound (LB) values, are provided in the supplementary material of this article.

The cohesion factors F c

In Fig. 3, the cohesion factor Fc increases as both the height-to-diameter ratio (H/D) and the internal friction angle (φ) grow. Taller anchors (higher H/D) experience greater cohesive forces, and materials with a higher friction angle (φ). also show a larger cohesion factor. For example, when φ is 40 degrees, the cohesion factor is much higher than when φ is 0 degrees.

The cohesion factor Fc remains nearly constant across the entire range of R values, meaning that R does not have a significant impact on Fc (ref. Figure 4).

Overall, the results show that increasing the H/D ratio and the internal friction angle (φ) significantly improves the anchor’s uplift capacity, while the anchor roughness factor R has an insignificant effect. The uplift capacity increase is especially pronounced at larger H/D ratios, highlighting the importance of considering both the internal friction angle and embedment depth in the design of circular anchors. The use of upper and lower-bound methods gives a thorough understanding of the potential uplift capacity under varying conditions, providing valuable insights for practical geotechnical design applications.

The failure mechanism of circular anchors is significantly influenced by the embedment depth, represented by the H/D ratio (ref. Figure 5). For shallow embedment (H/D = 1), the failure mechanism is relatively linear, with the soil directly above the anchor primarily resisting uplift forces. As the H/D ratio increases to 3, the failure zone expands, becoming more nonlinear and involving a larger soil mass, resulting in greater uplift resistance. By H/D = 5, the failure mechanism becomes fully nonlinear, with a deep, curved failure path engaging a substantial portion of the surrounding soil. This progression from linear to nonlinear failure reflects the increasing complexity and soil involvement as embedment depth increases, emphasizing the importance of considering both embedment and roughness in anchor design.

The surcharge factor F q

The surcharge factor Fq is essential for evaluating the resistance of soil anchors subjected to surcharge loading. The analysis reveals that Fq varies significantly with the embedment ratio (H/D) and the internal friction angle (φ) (ref. Figure 6). For an embedment ratio of H/D = 1, where the factor Fq is constant at 1.000 when φ is 0°, indicating no effect of surcharge in purely cohesive soils. As φ increases, Fq rises, reflecting the contribution of soil friction to the uplift capacity. For example, at φ = 20°, Fq increases from about 2.942 (lower bound) to 2.959 (upper bound), showing a steady rise with friction angle. The small difference between the lower and upper bound values at shallow depths suggests less nonlinearity in the solution.

As the embedment ratio increases to H/D = 2, 3, 4, and 5, the surcharge factor continues to grow, showing a more pronounced increase. For instance, at φ = 15° and H/D = 2, Fq ranges from 4.218 (lower bound) to 4.246 (upper bound), reflecting a higher uplift capacity with increased embedment. At H/D = 3 and φ = 30°, Fq reaches 19.395 (lower bound) and 19.560 (upper bound), indicating a substantial uplift capacity. The nonlinearity becomes more evident as the embedment ratio increases, with the gap between lower and upper bound values widening. At H/D = 5, the values are significantly higher, with Fq reaching 85.236 (lower bound) and 86.411 (upper bound) for φ = 40°. This indicates a pronounced nonlinear behavior of the failure surface at greater depths.

Overall, the surcharge factor Fq increases with the internal friction angle, with the trend of nonlinearity becoming more pronounced at deeper embedments and higher friction angles. The differences between lower and upper bound solutions remain manageable, suggesting that the predictive model for Fq is reliable.

On the other hand, the interface roughness between the anchor and soil (R) has an insignificant effect on the surcharge factor Fq, as demonstrated in Fig. 7.

Figure 8 illustrates typical failure mechanisms for varying embedment ratios (H/D) under the influence of the surcharge factor Fq. As depicted in the figure, the failure mechanisms exhibit increasing complexity and nonlinearity with higher embedment ratios. For H/D = 1, the failure mechanism is relatively simple and linear. The uplift resistance is primarily influenced by the immediate area around the anchor, resulting in a straightforward failure surface. As H/D increases to 3, the failure mechanism becomes more complex, with a larger failure zone extending further from the anchor. This indicates that the uplift capacity is affected by a larger volume of soil, leading to a more nonlinear behavior.

The most pronounced nonlinearity is observed at H/D = 5. At this embedment ratio, the failure mechanism displays a significantly larger and complex nonlinear failure surface compared to the lower ratios. The failure zone becomes increasingly curved and complex, reflecting a more significant deviation from linear behavior. This heightened nonlinearity at larger H/D ratios suggests that the uplift resistance is influenced by more complex interactions within a larger soil mass, making the prediction of uplift capacity more challenging, emphasizing the need for detailed analysis in deep anchor applications.

The unit weight factor F γ

Figures 9 and 10 provides lower-bound (LB) and upper-bound (UB) values for Fγ. These figures demonstrate the variation of the unit weight factor (Fγ) with different embedment ratios (H/D), friction angles (ϕ), and roughness coefficients (R) allowing for a discussion of the trends in these parameters.

For H/D = 1, across all friction angles and roughness values, the unit weight factor remains relatively small, showing a linear increase as the friction angle increases. The difference between LB and UB values is negligible, indicating that for shallow embedments, the effect of friction angle on uplift capacity is minimal. As the friction angle increases from ϕ = 0 to ϕ = 40 degrees, Fγ values increase steadily. As the embedment depth increases to H/D = 3 and H/D = 5, the unit weight factor Fγ becomes much more sensitive to changes in the friction angle. At H/D = 3, for ϕ = 10 degrees, Fγ values rise significantly from 7.236 (LB) to 7.296 (UB), while at ϕ = 40 degrees, Fγ reaches up to 43.136 (LB) and 44.156 (UB). This pattern continues at H/D = 5, where the unit weight factor reaches its highest values, particularly at larger friction angles. For example, at H/D = 5, ϕ = 40 degrees, Fγ attains values of 163.138 (LB) and 165.646 (UB), demonstrating a pronounced effect of embedment depth on the uplift capacity. The roughness (R) has negligible effect on the unit weight factor (Fγ) as demonstrated in Fig. 10.

The failure mechanisms in Fig. 11 for different embedment ratios (H/D = 1, 3, and 5) show that as the depth of the anchor increases, the failure zone expands, but the nonlinearity in soil behavior is less pronounced for the unit weight factor Fγ compared to Fc. For H/D = 1, the failure mechanism is shallow and linear, with the soil mobilized directly above the anchor. At H/D = 3, the failure surface expands outward, but the transition from linear to curved behavior remains gradual. By H/D = 5, the failure zone is larger and more curved, yet the nonlinearity is still moderate. In summary, while the failure mechanism transitions from linear to nonlinear with increasing depth, the changes are smoother for Fγ compared to Fc, with uplift resistance strongly influenced by the embedment ratio.

Comparative analysis with existing literature

Table 1 presents a comparison of Fc values with previous studies. For circular anchors, the current values of Fc closely match those reported by Merifield32, Khatri and Kumar33, Bhattacharya and Kumar34, Wang35, and Song et al.36 for the range of H/D = 1 to 5. Although the experimental work of Mehryar et al.37 and Kupferman38 shows slightly lower Fc values at similar H/D ratios, the current analysis compares reasonably well with Merifield32 for numerical three-dimensional lower bound limit analysis.

For the comparison of Fq results, numerical results are presented in Table 2. Notably, recent studies have rarely addressed the effect of surface pressure Fq. Despite this gap, we have included a comparison with Meyerhof and Adams4, revealing significant deviations in Fq for shallow depth ratio such as H/D = 1 and large value of ϕ such as ϕ = 40°. Besides, when ϕ = 20°, Fq shows slight discrepancies across all three H/D ratios. Notably, at H/D = 1, as ϕ increases to 30° and 40°, Meyerhof and Adams’s results are approximately 6 and 16 times higher than the current study. However, the discrepancies decrease as the embedment depth increases. Specifically, when ϕ = 30°, Meyerhof’s theory gives results approximately 2 times higher and nearly equal to the current study at H/D = 3 and H/D = 5, respectively. A similar pattern is observed when ϕ = 40°, with Meyerhof’s theory yielding results approximately 4.5 times and 2.3 times higher than the current study at the same H/D ratios.

As presented in Table 3, the comparison of Fγ values were conducted for H/D = 1, 3, and 5 across internal friction angles of φ = 20, 30, and 40 degrees. These comparisons demonstrate a good agreement between the current study and previous research, reinforcing the reliability of the proposed model. For the lowest ratio of (H/D = 1), the results from previous authors closely align with those of the current study, showing minimal differences across the examined internal friction angles. Similarly, when H/D increases to 3, the Fγ values from Sarac39 and Merifield et al.2 exhibit a slight decrease compared to the current study at φ = 20. However, at φ = 30 and 40 degrees, the Fγ values reported by Sarac39 show a significant decrease. Our results are also compared with those of Balla40, Meyerhof and Adams4, and Murray and Geddes41. The findings indicate that the results of Balla40 and Murray and Geddes41 are higher for φ = 20 and 30, and H/D = 3 and 5, respectively. In contrast, Meyerhof and Adams4 report lower values compared to the current study. It is noticeable that present study results of Fγ values agree well with experimental data of Balla40 and Tucker42. Overall, this analysis highlights the consistency of the proposed model with established literature, particularly at lower ratios and specific internal friction angles.

In summary, even though there is a noticeable difference in Fq values between Meyerhof’s theory and our study, the upper bound (UB) and lower bound (LB) results from our research are very close to each other. This shows that our findings are reliable and thus increases our confidence in the solutions we reported. Furthermore, the comparison of Fc and Fγ values with those from recent authors demonstrates strong agreement. Though there is limited experimental work of three factors due to the facts that Fc and Fq is formulated based on unrealistic soil properties (soil density = 0), the values of Fγ agree well with experimentation. These insights are valuable for practitioners in the field, indicating that our model can be trusted for practical applications.

Soft computing model

The KAN-based models in this study are trained on a comprehensive dataset generated via Finite Element Limit Analysis (FELA), which simulates the uplift behavior of circular anchors under varying soil and geometric conditions. By coupling FELA’s physics-informed output with KAN’s data-driven learning, the proposed approach combines numerical rigor with symbolic interpretability. This hybrid framework enables the derivation of reliable and compact expressions for anchor stability factors, facilitating practical engineering applications.

Dataset and statistical descriptions

Table 4 provides a detailed statistical overview of the input and output variables in this study. The input variables include the anchor’s roughness (R), internal friction angle (ϕ), and the ratio of embedment depth to diameter (H/D). The output variables consist of the cohesion factor (Fc), surcharge factor (Fq), and unit weight factor (Fγ).

The anchor’s roughness (R) ranges from 0 to 1, with a mean of 0.5 and a standard deviation of 0.3340. The distribution of R is symmetrical, as indicated by a skewness of 0. This reflects a balanced spread of values around the mean, suggesting uniformity in the roughness levels of the anchors used. The internal friction angle (ϕ) varies from 0 to 40 degrees, with a mean of 20 degrees and a standard deviation of 12.9099. The skewness value of 0 also indicates a symmetrical distribution around the mean, implying that the angles are evenly distributed without extreme outliers. The ratio of embedment depth to diameter (H/D) ranges from 1 to 5, with a mean of 3 and a standard deviation of 1.4142. The skewness value of 0 reflects a symmetrical distribution, showing that the embedment ratios are evenly spread around the average value.

In contrast, the output variables, Fc, Fq, and Fγ, exhibit considerable variability and positive skewness, indicating the presence of extreme values. The cohesion factor (Fc) has a mean of 17.2960, with a standard deviation of 23.2336 and a skewness of 1.4249. This suggests a wide range of values with a tendency towards higher extremes. The surcharge factor (Fq) has a mean of 6.3590, with a standard deviation of 18.3899 and a skewness of 2.0206. This positive skewness indicates a significant number of high values, leading to a heavy tail in the distribution. Similarly, the unit weight factor (Fγ) has a mean of 10.1490, a standard deviation of 34.2873, and a skewness of 2.2847. The high skewness reflects that while most values are clustered towards the lower end, there are substantial high outliers impacting the distribution.

A histogram visually represents the distribution of a dataset, highlighting the frequency of values within specified intervals (bins). For this dataset, which includes variables such as R, ϕ, H/D, Fc, Fq, and Fγ, the histograms reveal important characteristics. In Figs. 12 and 13, the input variables generally follow normal or uniform distributions, while the output variables (Fc, Fq, and Fγ) show skewed distributions. Specifically in Fig. 13, Fc peaks around 20, Fq near 15, and Fγ around 10, indicating these as the most frequent values. The large widths of the output histograms suggest significant variability, with wider distributions reflecting more variation in the data. Gaps or isolated bars, where Fc exceeds 60, Fq exceeds 40, and Fγ exceeds 50, may indicate potential outliers, representing extreme deviations from the dataset’s central tendency. The asymmetry in the output histograms suggests a bias in the data distribution, with most values clustering toward one side. It further demonstrates the pronounced variability and positive skewness, emphasizing the complexity and diverse nature of the factors influencing the uplift capacity of anchors. These characteristics highlight the need for advanced predictive models to capture the complex relationships of anchors in varying conditions.

In addition to histograms, the Probability Density Function (PDF) offers a detailed understanding of the dataset’s distribution. The PDF peaks indicate the most likely values for each variable, while the width of the PDF reflects variability. A narrow peak suggests low variability, and a broad distribution suggests high variability. The tails of the PDF highlight extreme values or outliers, while the skewness reflects asymmetry. For example, if the PDF of Fc has a sharp peak, it indicates that most values are concentrated around a central point, whereas a broad PDF suggests a more dispersed dataset. By combining histogram interpretations with PDF analysis, it is possible to gain deeper insights into the data’s distribution, allowing for better identification of trends, irregularities, and patterns.

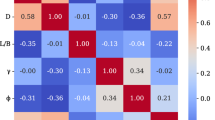

The heatmap of the correlation matrix shown in Fig. 14 reveals that all variables, including Fc, Fq, Fγ, and the input parameters such as R, ϕ, and H/D, are uncorrelated. This means that none of the variables exhibit a linear relationship with one another. Variations in one variable do not predict changes in any other, indicating that simple correlation analysis fails to capture any direct dependencies or interactions.

The absence of correlation suggests that these variables may have more complex or non-linear interactions that are not detected through basic correlation measures. As a result, more advanced analytical methods, such as non-linear regression or machine learning techniques, may be necessary to identify and understand potential relationships between the variables. This finding emphasizes the importance of considering more sophisticated models to explore any underlying patterns or dependencies within the dataset.

Kolmogorov-Arnold networks (KAN)

Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN) are founded on a theoretical framework that enables the decomposition of any continuous multivariate function into simpler univariate components. According to the Kolmogorov-Arnold theorem30, it is possible to represent a multivariable function as a sum of univariate functions, thus simplifying complex computations and optimizations. The theorem asserts that any smooth function defined over a bounded domain can be expressed through nested compositions of univariate functions, with addition serving as the primary multivariate operation. This decomposition significantly reduces the complexity of solving multivariate problems. A smooth function \((f:{{\mathbb{R}}^n} \to {\mathbb{R}}{\text{ }})\) can be written as:

where \({\psi _{q,p}}\) are univariate functions mapping [0, 1] to \({\mathbb{R}}\), and \({\Psi _q}\) are also univariate function.

However, the original formulation had limitations due to the fractal and non-smooth nature of the univariate functions, which made practical applications in machine learning challenging. To overcome this, KANs have evolved by incorporating deeper network architectures, allowing them to model the typical smoothness and sparsity found in real-world data. These extended architectures enhance the network’s ability to capture more complex relationships while still leveraging the simplicity of univariate functions.

KANs typically feature layers consisting of multiple univariate function elements arranged in a matrix-like fashion, with each function parameterized and trained based on input data. A typical KAN architecture consists of two layers: The first layer maps the multi-dimensional inputs into an intermediate space using univariate transformations, while the second layer combines these transformed inputs to produce a final scalar output. Like traditional deep learning models such as multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs), KANs can also adopt multi-layered architectures, enhancing their ability to approximate complex functions. What distinguishes KANs is their use of spline functions to parameterize activation functions, providing precise control over both the smoothness and accuracy of the approximations.

An important feature of KANs is their ability to improve model accuracy incrementally through a process known as spline grid refinement. Starting with a coarse grid, the parameters are initialized and then refined to a finer grid, progressively reducing approximation errors without requiring a full retraining of the model. This refinement is carried out as the following two steps: first, transferring parameters from the coarse grid to the refined grid to maintain continuity in the approximation. Second, fine-tuning the parameters on the refined grid to minimize errors between the coarse and refined representations, thereby enhancing overall accuracy.

The performance of KANs is also influenced by the order of the spline functions, denoted as k. Higher-order splines provide more flexible and smoother approximations, allowing the network to achieve lower approximation errors with fewer parameters. The approximation error ε for a KAN with B-spline activations of order k with the number of parameters N as follows follows the relationship:

This relationship suggests that the approximation error decreases more rapidly with increasing spline order, making KANs particularly effective for smooth function modeling. However, higher-order splines also increase model complexity and the number of parameters, which can affect both training time and computational resource requirements.

In summary, Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks offer a unique and effective approach to modeling complex functions by combining univariate decomposition with modern deep learning architectures43. Their ability to incrementally refine spline-based approximations ensures both high accuracy and computational efficiency, making KANs particularly well-suited for tasks that demand detailed and precise function modeling. This adaptability and refinement process set KANs apart from traditional neural network architectures, making them a valuable tool for advanced applications in fields like geotechnical engineering44.

Results and discussion

Optimizing topology

The performance of Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KANs) can be influenced by several key hyperparameters: the number of grid points, the size of the middle layers, and the spline order. As shown in Fig. 15a, increasing the number of nodes enhances the network’s ability to model intricate functions, resulting in lower training and test errors. However, larger networks are more prone to overfitting and require more computational resources. A width of 6 nodes was chosen as an optimal balance between model expressiveness and overfitting risk.

The grid points used to define spline functions within the KAN are crucial for accuracy. A higher number of grid points allows for a more detailed and flexible representation of the underlying function, enhancing model performance and reducing errors, as shown in Fig. 15b. However, too many grid points may result in overfitting. Thus, a grid configuration of 4 points was chosen to optimize performance while mitigating overfitting concerns.

The spline order influences both the smoothness and computational complexity of the activation functions. Higher-order splines provide smoother approximations but can increase computational load. Figure 15c shows that a spline order of 8 offers a good compromise between accuracy and computational efficiency.

The choice of optimizer plays a crucial role in the effectiveness and convergence of machine learning models. In this research, we compared the performance of the Limited-memory BFGS (L-BFGS) optimizer with the Adam optimizer. As shown in Fig. 16, the training histories of Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks optimized with L-BFGS and Adam demonstrate that L-BFGS outperforms Adam, achieving faster convergence and greater error reduction.

The training procedure is divided into two key phases to enhance model efficiency and minimize overfitting. In first step, training with sparsification (Epochs 0–100) involves applying sparsification techniques to the network, which introduces sparsity into the parameters. Figure 16 demonstrates that both optimizers perform similarly during this initial phase. Next, in step of Training Affine Parameters (Epochs 100–130), it focuses on optimizing the parameters of affine transformations applied to symbolic functions integrated into a KAN, ensuring that these symbolic functions are effectively incorporated into the network and contribute to accurately representing the underlying relationships in the data. The results in Fig. 16 indicate that L-BFGS consistently outperforms Adam in this phase, achieving lower training and validation errors.

Figure 17; Table 5 illustrate the application of Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN) for symbolic regression, specifically predicting the cohesion factor Fc. This approach is designed to capture relationships between key input variables: R; φ; and H/D and their effect on the cohesion factor.

In Fig. 17: The first part shows a fully connected network; the second part shows some connections being faded out, possibly simplifying the network by removing unnecessary connections; the third part highlights the most important connections in red, showing the final, simplified network that is crucial for predicting the cohesion factor.

Table 5 describes the network structure: The input layer has 3 neurons (one for each input variable); there is one hidden layer with 6 neurons; the output layer has 1 neuron, which predicts the cohesion factor.

The training process uses the L-BFGS optimizer (a method for minimizing the error). The model’s performance is evaluated using Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). Additionally, a cubic spline (spline of order 3) is used to help smooth and interpolate the data.

Figure 18; Table 6 show the use of Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN) for predicting the cohesion factor Fq. Similar to the previous network for predicting Fc, the model takes three inputs: R, φ, and H/D.

The network consists of: 3 input neurons; 1 hidden layer with 6 neurons; 1 output neuron for predicting Fq. The process uses the L-BFGS optimizer to minimize the RMSE, ensuring accurate predictions. A cubic spline of order 3 is used to help model smooth relationships between inputs and outputs.

Figure 18 shows the network’s evolution: The first diagram represents a fully connected network; The second diagram shows the important connections; The third diagram highlights critical connections in red, showing that H/D is especially important for predicting Fq.

Figure 19; Table 7 show the use of Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN) for predicting the cohesion factor Fγ. The network has 3 input neurons representing R, φ, and H/D. It features: 1 hidden layer with 4 neurons (smaller than previous networks); 1 output neuron predicting Fγ.

The model is optimized using the L-BFGS optimizer and evaluated with RMSE for accuracy, while a cubic spline (order 3) ensures smooth data representation.

In Fig. 19: The first diagram shows the fully connected network; The second diagram indicates the pruning of unnecessary connections; The third diagram highlights important connections in red, especially focusing on H/D, which plays a key role in predicting Fγ.

Assessing performance

Figure 20 provides a comparative analysis of the regression performance for predicting the cohesion factor (Fc) using Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) across both training and testing datasets. The KAN results show that the R2 values are exceptionally high, with 1.000 for both training and testing datasets, indicating a perfect fit on the training data and an excellent fit on the testing data. This suggests that the KAN model captures the underlying patterns of the data with high accuracy. The Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) values are 0.299 for training and 0.368 for testing, demonstrating relatively low errors and good predictive performance. Similarly, the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values are 0.235 for training and 0.276 for testing, reflecting the KAN’s ability to make accurate predictions with minimal absolute errors. The A10 scores, both 0.978, further emphasize the model’s robustness, indicating that 97.8% of the predictions fall within a 10% error margin.

In contrast, the ANN model shows slightly lower R2 values of 0.999 for training and 0.996 for testing, which are still high but slightly less perfect compared to the KAN model. The RMSE values for ANN are higher, at 0.856 for training and 1.469 for testing, suggesting that the ANN model has larger errors compared to the KAN model. The MAE values for ANN are also higher, with 0.684 for training and 1.039 for testing, indicating less precision in predictions compared to the KAN model. The A10 scores for ANN are 0.85 for training and 0.8 for testing, meaning that 85% and 80% of the predictions fall within a 10% error margin for training and testing, respectively, which is lower than that of the KAN model.

Overall, the KAN model demonstrates superior performance compared to the ANN model, with higher R2 values, lower RMSE and MAE values, and better A10 scores. This indicates that KAN is more effective in accurately predicting the cohesion factor (Fc) and generalizes better on unseen data compared to the ANN model.

In Fig. 21, the regression plots for predicting the surcharge factor (Fq) using Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) across both training and testing datasets are presented. For the KAN model, the R2 values are perfect at 1.000 for both training and testing datasets, indicating a flawless fit on the training data and an excellent fit on the testing data. This suggests that the KAN model effectively captures the underlying relationships in the data. The Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) values are 0.253 for training and 0.260 for testing, reflecting low error levels and strong predictive performance. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values are 0.204 for training and 0.223 for testing, further highlighting the accuracy of the KAN model with minimal absolute errors. The A10 scores are 0.8 for both training and testing, meaning that 80% of the predictions fall within a 10% error margin, demonstrating good predictive reliability.

In comparison, the ANN model shows very high R2 values of 0.998 for training and 0.994 for testing, indicating strong performance, though slightly less perfect than the KAN model. The RMSE values for ANN are higher, at 0.717 for training and 1.528 for testing, suggesting that the ANN model has greater prediction errors compared to the KAN model. The MAE values for ANN are also higher, with 0.546 for training and 0.951 for testing, indicating less precision in predictions relative to the KAN model. The A10 scores for ANN are lower, at 0.65 for training and 0.556 for testing, meaning that 65% and 55.6% of the predictions fall within a 10% error margin for training and testing, respectively.

Overall, the KAN model demonstrates better performance compared to the ANN model in predicting the surcharge factor (Fq), with higher R2 values, lower RMSE and MAE values, and higher A10 scores. This indicates that KAN provides more accurate and reliable predictions and performs better in generalizing to new data compared to the ANN model.

Finally, in Fig. 22, the regression plots for predicting the unit weight factor (Fγ) are presented using Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) across both training and testing datasets. For the KAN model, the R2 values are perfect at 1.000 for training and 0.999 for testing, indicating an excellent fit on both datasets. This high R2 value suggests that the KAN model accurately captures the underlying relationships in the data. The Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) values are 0.723 for training and 1.055 for testing, demonstrating relatively low prediction errors. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values are 0.541 for training and 0.722 for testing, indicating that the KAN model has a high degree of precision in its predictions. The A10 scores are 0.767 for training and 0.778 for testing, meaning that 76.7% and 77.8% of the predictions fall within a 10% error margin, respectively, highlighting the model’s robust predictive performance.

In comparison, the ANN model has R2 values of 0.996 for training and 0.986 for testing. While still high, these values are lower than those of the KAN model, indicating slightly less optimal fit. The RMSE values for ANN are higher, at 2.225 for training and 4.372 for testing, suggesting that the ANN model has larger prediction errors compared to the KAN model. The MAE values for ANN are also higher, with 1.438 for training and 2.385 for testing, reflecting reduced precision in predictions. The A10 scores for ANN are 0.578 for training and 0.533 for testing, showing that only 57.8% and 53.3% of the predictions fall within a 10% error margin, respectively, which is lower compared to the KAN model.

Overall, the KAN model outperforms the ANN model in predicting the unit weight factor (Fγ), with higher R2 values, lower RMSE and MAE values, and better A10 scores. This indicates that KAN provides more accurate and reliable predictions and demonstrates superior generalization to new data compared to the ANN model.

In summary, the regression analyses presented in Figs. 20, 21 and 22 highlight the robustness and precision of the Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN) model in predicting the three anchor stability factors (Fc, Fq, and Fγ). Across all three factors, the KAN model consistently demonstrates superior performance compared to the Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model.

Sensitivity analysis

The SHAP (SHapley additive exPlanations) values

As shown in Fig. 23, the SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations)45 values provide valuable insights into the relative importance of the stability factors Fc, Fq, and Fγ.

For the height-to-diameter ratio (H/D), the SHAP values are 18.8 for Fc, 13.9 for Fq, and 8.2 for Fγ. These values indicate that H/D is most influential in predicting Fc, but its impact decreases as we move to Fq and Fγ. This suggests that while H/D remains an important factor, its role diminishes when predicting Fγ, contrary to the earlier interpretation where it was thought to increase in importance. In comparison, the soil friction angle (φ) plays a steady and essential role across all stability factors, with SHAP values of 16.3 for Fc, 10.7 for Fq, and 10.9 for Fγ. These nearly consistent values show that φ is a crucial factor in predicting anchor stability, particularly for Fγ, where its impact is more pronounced relative to H/D.

On the other hand, the impact of anchor roughness is minimal, as evidenced by its SHAP values, which are almost zero for Fc, Fq, and Fγ. This indicates that anchor roughness has a negligible effect on the predictions of these anchor stability factors, suggesting that other factors, such as H/D and φ, are more critical in determining the anchor stability.

Overall, the SHAP analysis reveals that H/D is most critical for Fc but less so for Fγ, while ϕ has a consistent and significant impact across all stability factors, particularly influencing Fγ. The anchor roughness (R) remains largely irrelevant, highlighting its limited contribution within the modeled range (R = 0 to 1).

This result is particularly meaningful for real-world applications, where variability in interface roughness may arise due to construction tolerances, manufacturing inconsistencies, or field installation techniques. The negligible SHAP values for R suggest that such variability has little influence on uplift capacity in frictional-cohesive soils. Consequently, engineers can focus design efforts on optimizing key parameters like embedment ratio (H/D) and friction angle (ϕ), which have much stronger influence on performance, rather than investing in enhancing surface roughness unless project-specific data suggest a significant deviation.

Partial dependence plots (PDPs)

Partial dependence plots (PDPs) are a useful visualization tool in machine learning that can be used to demonstrate the relationship between a target variable and one or more features. By isolating the effects of individual features, PDPs help provide a clearer understanding of how each feature influences the model’s predictions, making them particularly useful for interpretability46,47,48. The effects of each input variable on the cohesion factor Fc are illustrated in Fig. 24. Anchor roughness (R) has a negligible impact on Fc, as the factor only increases slightly from 26.265 to 26.290 when transitioning from smooth to rough conditions. In contrast, both the soil friction angle (φ) and the height-to-diameter ratio (H/D) exhibit significant effects on Fc. As φ increases from 0 to 40 degrees, Fc rises dramatically from 10 to over 45, demonstrating a pronounced sensitivity to changes in soil friction. Similarly, Fc increases from 2 to more than 50 as H/D varies from 1 to 5.

Figure 25 shows the impact of each input variable on the surcharge factor Fq. As with Fc, anchor roughness (R) has a minimal effect on Fq, with the value changing only slightly from 14.586 to 14.592 from smooth to rough condition. Both φ and H/D, however, have significant effects on Fq. The factor Fq increases dramatically from 1 to over 40 as φ increases from 0 to 40 degrees, reflecting a strong non-linear relationship. Similarly, Fq rises from 1 to more than 28 as H/D increases from 1 to 5, further illustrating the pronounced sensitivity of Fq to changes in these variables.

Figure 26 presents the effects of each input variable on the surcharge factor factor Fγ. Anchor roughness (R) again shows negligible influence, with Fγ increasing only slightly from 24.475 to 24.625 from smooth to rough condition. In contrast, φ and H/D both have a substantial effect on Fγ. As φ increases from 0 to 40 degrees, Fγ rises from 1 to over 60, demonstrating a strong non-linear relationship. Similarly, Fγ increases from 1 to more than 60 as H/D varies from 1 to 5. Both φ and H/D exhibit a pronounced non-linear relationship with Fγ, highlighting their critical role in determining the anchor stability.

Mathematical modeling for hand calculation

In this section, we provide mathematical equations for evaluating the anchor stability factors Fc, Fq, and Fγ for the circular anchor on frictional-cohesive soils. These models are formulated to facilitate hand/spreadsheet calculations, making them accessible for practical engineering applications. The variables used in the models include the height-to-diameter ratio (H/D) and the internal friction angle φ.

The cohesion factor Fc - see Eq. (7):

The surcharge factor Fq - see Eq. (8):

The unit weight factor Fγ - see Eq. (9):

These mathematical models provide an efficient and accurate approach for estimating the three anchor stability factors: Fc, Fq, and Fγ. The model parameters are carefully derived to account for the complex interactions between the height-to-diameter ratio (H/D) and the internal friction angle (ϕ). While the closed-form solutions from these optimal models are comprehensive, they may be too lengthy and cumbersome for hand calculations. Nonetheless, implementing these solutions in spreadsheets offers a practical alternative. The detailed formulations of these three models are expressed as follows:

The complex form of Fc.

\(\begin{gathered} {F_c}= - 158.54333 \cdot {\left( \begin{gathered} - 0.06311 \cdot {\text{sigmoid}}(0.25596 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}} - 2.45015) - 0.26471 \hfill \\ \cdot \sin (6.02558 \cdot R - 9.92327)+1.0 \cdot {10^{ - 5}} \cdot \sin (6.23958 \cdot \phi - 3.00692)+1 \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right)^2} \hfill \\ - 37.20929 \cdot {\text{sigmoid}}( - 0.00468 \cdot {( - 0.46414 \cdot \phi - 1)^2} - 2.92665 \cdot \sin (9.99227 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}} - 1.97847) \hfill \\ - 3.08076 \cdot \sin (0.70978 \cdot R - 8.73413)+3.64498) - 16.76983 \cdot \sin ( - 0.00422 \cdot {(0.20261 - \phi )^2} \hfill \\ +2.69098 \cdot {\text{sigmoid}}(2.08764 - 0.84682 \cdot R)+39.11408 \cdot \sin (8.80021095275879 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}} - 8.23062)+37.26608) \hfill \\ - 0.09612 \cdot \sin (7.27767 \cdot {( - \phi - 0.73989)^2}+2.29388 \cdot \sin (2.64017 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}} - 2.14579) \hfill \\ +0.05576 \cdot \left| {7.9999 \cdot R - 10.00005} \right| - 14.4597) - 0.49393 \cdot \sin (0.04209 \cdot \sin (3.66679000854492 \cdot \phi +6.9663) \hfill \\ +18.01896 \cdot \tanh (0.39228 \cdot R+1.33353) - 0.03737 \cdot \left| {10.00115 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}}+9.99881} \right| - 16.04791) \hfill \\ +10.8289 \cdot \tanh (14.19757 \cdot \sin (10.03946 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}} - 8.22589)+20.56399 \cdot \sin (0.77282 \cdot R - 2.64762) \hfill \\ +0.00627 \cdot \tanh (3.2582 \cdot \phi - 2.20795) - 9.82714)+160.48258 \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

The complex form of Fq

\(\begin{gathered} {F_q}= - 0.62175 \cdot {\left(\begin{gathered}0.07446 \cdot {{(0.56 - \phi )}^3}+0.01014 \cdot {{( - 0.02447 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}} - 1)}^4}\hfill \\ - 0.00867 \cdot \sin (4.82656 \cdot R+0.912) - 1\end{gathered} \right)^4} \hfill \\ - 0.20329 \cdot {\left(\begin{gathered}- 0.15248 \cdot {{(1 - 0.0387 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}})}^3}+\sin (6.64319 \cdot R+9.42)\hfill \\ +0.01246 \cdot \sin (6.7291202545166 \cdot \phi - 0.56663990020752)+0.42728\hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right)^2} \hfill \\ - 14.12074 \cdot {\left(\begin{gathered} - 0.53237 \cdot {{(1 - 0.02392 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}})}^2} - 0.7162 \cdot {{( - 0.03151 \cdot R - 1)}^4}\hfill \\ +0.00125 \cdot \sin (5.93912 \cdot \phi +3.41256)+1\hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right)^2} \hfill \\ - 1.60775 \cdot {\left( \begin{gathered} 0.81448 \cdot {{(1 - 0.24 \cdot R)}^4} - 0.03168 \cdot \sin (5.20706 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}}+8.50013)\hfill \\ - 8.0 \cdot {{10}^{ - 5}} \cdot \left| {9.96 \cdot \phi - 8.204} \right| - 1\hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right)^3} \hfill \\ - 8251.23242 \cdot {\text{sigmoid}}( - 0.00396 \cdot {(0.512 - \phi )^2}+1.31874 \cdot \sin (7.6067 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}}+1.45939) \hfill \\ - 45.43742 \cdot \tanh (0.17482 \cdot R+1.38987)+50.17584) - 0.41537 \cdot \tanh (1.96513 \cdot {(0.5076 - \phi )^4} \hfill \\ +2.64996 \cdot {(1 - 0.36 \cdot R)^4} - 53.53826 \cdot \sin (8.80806922912598 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}}+5.98377) - 6.37116)+8253.11528. \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

The complex form of Fγ

\(\begin{gathered} {F_\gamma }=1573629.542 \cdot {\left( \begin{gathered} - 0.00498 \cdot {(0.41927 - \phi )^4}+0.13747 \cdot {\text{sigmoid}}(6.64154 - 0.13943 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}}) \hfill \\ - 0.92291 \cdot \tanh (0.31996 \cdot R - 3.12084) - 1 \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right)^4} \hfill \\ +66.85674 \cdot {\left( \begin{gathered} - \sin (7.56303 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}} - 6.3111)+0.34861 \cdot \sin (0.97603 \cdot R+5.97284) \hfill \\ +0.00239 \cdot \sin (4.00282 \cdot \phi - 5.9831)+0.02951 \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right)^4} \hfill \\ - 153.87439 \cdot {\text{sigmoid}}( - 1.18303 \cdot \sin (3.80265 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}} - 0.64466) - 1.21377 \cdot \tanh (0.71057 \cdot R - 1.2582) \hfill \\ - 0.00807 \cdot \tanh (9.78330993652344 \cdot \phi - 7.94905)+2.32101)+1.16218 \cdot \tanh (1.0895 \cdot {( - 0.23839 \cdot \phi - 1)^2} \hfill \\ +178.50594 \cdot \sin (8.80467 \cdot {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$H$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {H D}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}}+0.41231)+30.72585 \cdot \tanh (0.5543 \cdot R - 2.88755) - 94.34771)+139.03192. \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

An important advantage of the derived closed-form solutions is their compatibility with widely used spreadsheet software (e.g., Microsoft Excel). These formulas consist solely of basic arithmetic operations—addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and exponentiation—which makes them easy to implement without requiring any programming expertise. In contrast to conventional ANN-based models, which often rely on specialized software or numerical libraries, the KAN-based expressions can be directly embedded into spreadsheet cells. This enables engineers to input project-specific parameters—such as soil friction angle, embedment ratio, and interface roughness—and instantly compute the corresponding stability factors (Fc, Fq, and Fγ). The ease of integration not only supports rapid and transparent design iterations but also lowers the technical barrier to adoption, making the proposed methodology especially suitable for routine geotechnical engineering practice.

Furthermore, these closed-form KAN-based expressions empower engineers to perform rapid, spreadsheet-driven estimations of anchor uplift capacity, which is particularly valuable during preliminary or conceptual design stages. Owing to their high predictive accuracy, these models can serve as effective alternatives to computationally intensive simulations in early-phase assessments. In addition, interpretability tools such as SHAP and PDP analyses offer meaningful insights into parameter influence—revealing, for instance, that increasing the embedment ratio (H/D) or selecting soils with higher internal friction angles yields more substantial gains in capacity than modifying interface roughness. These practical insights align well with common geotechnical workflows, where time-efficient, data-informed tools are essential for both optimization and risk mitigation.

Conclusions

This study developed a novel framework combining Finite Element Limit Analysis (FELA) with Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN) to predict the uplift capacity of circular anchors in frictional-cohesive soils under surcharge loading. The three Terzaghi-based stability factors i.e., Fc, Fq, and Fγ, were modeled using KAN, offering closed-form predictive expressions validated against benchmark data.

KAN models significantly outperformed conventional Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) across all regression metrics, achieving R² values above 0.998 and substantially lower RMSE and MAE values, demonstrating excellent accuracy and generalization. The resulting closed-form equations are easily integrated into spreadsheet tools, enabling fast and practical estimation of uplift capacity in routine design.

Sensitivity analysis revealed that embedment ratio (H/D) and soil friction angle (ϕ) are the dominant contributors to uplift capacity, while anchor roughness had negligible influence—an insight that supports targeted design optimization.

The current study is limited to circular plate anchors in homogeneous frictional-cohesive soils under axisymmetric conditions, using a Mohr-Coulomb material model without accounting for layering, anisotropy, or time-dependent effects. As such, direct applicability to other anchor types (e.g., helical, drag embedment49, group anchors) or complex soil profiles is limited. However, the flexible FELA–KAN framework can be extended by retraining on more diverse datasets. Future research should explore incorporating spatial variability50, probabilistic failure modeling, and additional geometric or installation-related factors to broaden applicability.

This study bridges theoretical modeling with practical application, offering interpretable, reliable, and engineer-friendly tools for the design of anchor systems in complex geotechnical settings.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

References

Merifield, R. S. & Sloan, S. W. The ultimate pullout capacity of anchors in frictional soils. Can. Geotech. J. 43, 852–868. https://doi.org/10.1139/t06-052 (2006).

Merifield, R. S., Lyamin, A. V. & Sloan, S. W. Three-dimensional lower-bound solutions for the stability of plate anchors in sand. Géotechnique 56, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.2006.56.2.123 (2006).

Vesić, A. S. Breakout resistance of objects embedded in ocean bottom. J. Soil. Mech. Found. Div. 97, 1183–1205 (1971).

Meyerhof, G. G. & Adams, J. I. The ultimate uplift capacity of foundations. Can. Geotech. J. 5, 225–244. https://doi.org/10.1139/t68-024 (1968).

Meyerhof, G. Proc. 8th ICSMFE. 167–172.

Ali, M. S. Pullout Resistance of Anchor Plates and Anchor Piles in Soft Bentonite Clay (Duke University, 1969).

Das, B. M. A procedure for Estimation of ultimate uplift capacity of foundations in clay. Soils Found. 20, 77–82. https://doi.org/10.3208/sandf1972.20.77 (1980).

Das, B. M. Model tests for uplift capacity of foundations in clay. Soils Found. 18, 17–24. https://doi.org/10.3208/sandf1972.18.2_17 (1978).

Das, B. M. & Shukla, S. K. Earth Anchors (J. Ross Publishing, 2013).

Yu, H. S. Finite element analysis. Plast. Geotech., 456–516 (2006).

Das, B. M., Moreno, R. & Dallo, K. F. Ultimate pullout capacity of shallow vertical anchors in clay. Soils Found. 25, 148–152. https://doi.org/10.3208/sandf1972.25.2_148 (1985).

Das, B., Tarquin, A. & Moreno, R. Model tests for pullout resistance of vertical anchors in clay. Civil Eng. Practicing Des. Eng. 4, 191–209 (1985).

Baba, H., Gulhati, S. & Datta, M. Congrès international de mécanique des sols et des travaux de fondations. 12. 409–412.

Rowe, R. K. & Davis, E. H. The behaviour of anchor plates in clay. Géotechnique 32, 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1982.32.1.9 (1982).

Shiau, J., Nguyen, T. & Ly-Khuong, D. Unraveling seismic uplift behavior of plate anchors in frictional-cohesive soils: A comprehensive analysis through stability factors and machine learning. Ocean Eng. 297, 116987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.116987 (2024).

Drucker, D. C., Prager, W. & Greenberg, H. J. Extended limit design theorems for continuous media. Q. Appl. Math. 9, 381–389 (1952).

Sloan, S. W. Lower bound limit analysis using finite elements and linear programming. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Meth. Geomech. 12, 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/nag.1610120105 (1988).

Sloan, S. W. Upper bound limit analysis using finite elements and linear programming. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Meth. Geomech. 13, 263–282. https://doi.org/10.1002/nag.1610130304 (1989).

Merifield, R. S., Sloan, S. W. & Yu, H. S. Rigorous plasticity solutions for the bearing capacity of two-layered clays. Géotechnique 49, 471–490. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1999.49.4.471 (1999).

Nguyen-Minh, T., Bui-Ngoc, T., Shiau, J., Nguyen, T. & Nguyen-Thoi, T. Undrained sinkhole stability of circular cavity: a comprehensive approach based on isogeometric analysis coupled with machine learning. Acta Geotech. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-024-02266-3 (2024).

Nguyen-Minh, T., Bui-Ngoc, T., Shiau, J., Nguyen, T. & Nguyen-Thoi, T. Coupling isogeometric analysis with deep learning for stability evaluation of rectangular tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 140, 105330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2023.105330 (2023).

Bottero, A., Negre, R., Pastor, J. & Turgeman, S. Finite element method and limit analysis theory for soil mechanics problems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 22, 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/0045-7825(80)90055-9 (1980).

Lyamin, A. V. (University of Newcastle, 1999).

Nguyen, T. & Shiau, J. Revisiting active and passive Earth pressure problems using three stability factors. Comput. Geotech. 163, 105759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2023.105759 (2023).

Choudhary, A. K., Pandit, B. & Babu, G. L. S. Three-Dimensional analysis of uplift behaviour of square horizontal anchor plate in frictional soil. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 4 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40891-018-0130-1 (2018).

Sakai, T. & Tanaka, T. Scale effect of a shallow circular anchor in dense sand. Soils Found. 38, 93–99. https://doi.org/10.3208/sandf.38.2_93 (1998).

Yünkül, K., Usluoğulları, Ö. F. & Gürbüz, A. Numerical analysis of geocell reinforced square shallow horizontal plate anchor. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 39, 3081–3099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-021-01679-1 (2021).

Kolmogorov, A. N. On the Representation of Continuous Functions of Several Variables by Superpositions of Continuous Functions of a Smaller Number of Variables (American Mathematical Society, 1961).

Kolmogorov, A. N. On the representation of continuous functions of many variables by superposition of continuous functions of one variable and addition. Translations Am. Math. Soc. 2, 55–59 (1963).

Liu, Z. et al. Kan: Kolmogorov-arnold networks. arXiv (2024).

Ali, A. et al. Probabilistic stability assessment using adaptive limit analysis and random fields. Acta Geotech. 12, 937–948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-016-0505-1 (2016).

Merifield, R. S., Lyamin, A. V., Sloan, S. W. & Yu, H. S. Three-Dimensional lower bound solutions for stability of plate anchors in clay. J. Geotech. GeoEnviron. Eng. 129, 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)1090- (2003). 0241(2003)129:3(243).

Khatri, V. N. & Kumar, J. Vertical uplift resistance of circular plate anchors in clays under undrained condition. Comput. Geotech. 36, 1352–1359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2009.06.008 (2009).

Bhattacharya, P. & Kumar, J. Uplift capacity of strip and circular anchors in soft clay with an overlay of sand layer. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 33, 1475–1488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-015-9913-5 (2015).

Wang, D., Hu, Y. & Randolph, M. F. Three-Dimensional large deformation Finite-Element analysis of plate anchors in uniform clay. J. Geotech. GeoEnviron. Eng. 136, 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)gt.1943-5606.0000210 (2010).

Song, Z., Hu, Y. & Randolph, M. F Numerical simulation of vertical pullout of plate anchors in clay. J. Geotech. GeoEnviron. Eng. 134, 866–875. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)1090-0241(2008)134:6(866) (2008).

Mehryar, Z., Hu, Y. & Randolph, M. Numerical models in geomechanics. NUMOG VIII. 507–513.

Kupferman, M. The Vertical Holding Capacity of Marine Anchors in Clay Subjected To Static and Cyclic Loading (University of Massachusetts, 1971).

Sarac, D. Congrès international de mécanique des sols et des travaux de fondations. 12 1213–1216.

Balla, A. The resistance to breaking out of mushroom foundation. Budapest: Hung. (1961).

Murray, E. J. & Geddes, J. D. Uplift of anchor plates in sand. J. Geotech. Eng. 113, 202–215. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)0733-9410 (1987).

Tucker, K. D. Foundations for transmission line towers. 142–159 (ASCE).

Schmidt-Hieber, J. The Kolmogorov-Arnold representation theorem revisited. Neural Netw. 137, 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2021.01.020 (2021).

Sulaiman, M. H., Mustaffa, Z., Saealal, M. S., Saari, M. M. & Ahmad, A. Z. Utilizing the Kolmogorov-Arnold networks for chiller energy consumption prediction in commercial Building. J. Building Eng. 96, 110475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.110475 (2024).

Lundberg, S. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. arXiv (2017).

Bui-Ngoc, T., Nguyen, T., Nguyen-Quang, M. T. & Shiau, J. Predicting load-displacement of driven PHC pipe piles using stacking ensemble with Pareto optimization. Eng. Struct. 316 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.118574 (2024).

Nguyen, T., Ly, D. K., Shiau, J. & Nguyen-Dinh, P. Optimizing load-displacement prediction for bored piles with the 3mSOS algorithm and neural networks. Ocean Eng. 304, 117758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.117758 (2024).

Van Tran, M., Ly, D. K., Nguyen, T. & Tran, N. Robust prediction of workability properties for 3D printing with steel slag aggregate using bayesian regularization and evolution algorithm. Constr. Build. Mater. 431, 136470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136470 (2024).

Cheng, P., Guo, J., Yao, K. & Chen, X. Numerical investigation on pullout capacity of helical piles under combined loading in spatially random clay. Mar. Georesources Geotechnology. 41, 1118–1131. https://doi.org/10.1080/1064119x.2022.2120843 (2022).

Cheng, P., Liu, F., Chen, X., Zhang, Y. & Yao, K. Estimation of the installation torque–capacity correlation of helical pile considering spatially variable clays. Can. Geotech. J. 61, 2064–2074. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2023-0331 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by Viet Solution Construction Consultants Co., Ltd. (https://www.giaiphapviet.com.vn/), a renowned contractor in Vietnam’s construction industry, whose contribution was instrumental in facilitating this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tran Vu-Hoang: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing; Tan Nguyen: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision; Jim Shiau: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing, Validation; Hung-Thinh Pham-Tran: Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization; Trung Nguyen-Thoi: Writing - Review & Editing, Methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vu-Hoang, T., Nguyen, T., Shiau, J. et al. Predicting the uplift capacity of circular anchors in frictional-cohesive soils using Kolmogorov-Arnold networks. Sci Rep 15, 14549 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98945-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98945-6