Abstract

In this paper, we introduce a miniaturized intracardiac photoacoustic (PA) imaging system based on a phased-array intracardiac echocardiography catheter. This PA imaging system enhances imaging feedback during radiofrequency (RF) ablation for atrial fibrillation (A-fib) by providing ablation-induced lesion mapping. The PA imaging catheter with a 4-mm diameter was designed, featuring flexible tip for bending and navigation through the vessels. The catheter’s imaging resolution was evaluated using a phantom study with 0.2-mm-diameter wires. In an ex vivo study, the catheter was used to detect ablation-induced necrosis in porcine cardiac tissue, evaluating its capability to image through blood layer and differentiate necrotic tissue based on spectral characteristics. The catheter achieved an imaging resolution of 647.35 ± 61.60 µm in the phantom study. In the ex vivo study, it successfully identified necrotic lesions on porcine cardiac tissue, distinguishing these from surrounding tissue based on spectral analysis. The catheter system successfully imaged through an 8-mm blood layer, effectively highlighting necrotic regions. The proposed miniaturized PA imaging catheter demonstrated high-resolution imaging capability and effective detection of ablation-induced tissue boundary. Its flexibility and small diameter allow for maneuverability through cardiac vessels, enhancing its utility for intraoperative feedback during RF ablation procedures. This advancement offers a practical tool for improving the precision and effectiveness of RF ablation in A-fib treatment by integrating high-resolution imaging and maneuverability into a PA imaging catheter, potentially facilitating its adoption in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

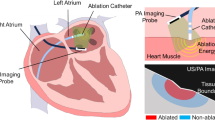

Atrial fibrillation (A-fib) is a common heart arrhythmia affecting millions of people worldwide, which can lead to complications such as stroke and heart failure1,2. The current standard of care for drug-resistant A-fib is to use percutaneous catheter ablation therapy, which includes radiofrequency (RF) ablation. RF ablation aims to create lines of targeted tissue necrosis surrounding the pulmonary veins by creating lesions that block abnormal electrical signals from the pulmonary veins, which are known to trigger A-fib. However, monitoring the ablation-induced lesion boundary during the procedure remains a challenge, which may lead to incomplete or excessive ablation3,4,5. Although computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging are commonly used in ablation guidance, neither modality provides real-time feedback, and their intraoperative use remains limited.

Photoacoustic (PA) imaging has recently emerged as a promising imaging modality for monitoring the ablation process in real time based on tissue spectrum changes during ablation6. PA imaging has several unique advantages over conventional imaging modalities. PA imaging is non-ionizing and relies on either the tissue’s intrinsic contrast or the administration of contrast agents7. PA imaging can provide functional and molecular information based on the tissue’s optical absorption properties making it an attractive option for intraoperative monitoring of ablation therapy8. Moreover, PA imaging can provide real-time feedback during the ablation process, enabling the physician to adjust the ablation parameters based on the tissue response9,10,11.

While PA imaging has demonstrated promising potential for mapping necrotic lesions in preclinical studies, its clinical translation and practical implementation in actual procedures remain unexplored. Most previous studies on PA-based ablation monitoring have employed handheld or laparoscopic ultrasound (US) probes to scan tissues without spacing constraints. The size of these imaging devices limits their use in intracardiac applications6,8,9. Efforts to miniaturize imaging systems for intracardiac use have included the separate insertion of optical fibers to deliver light energy inside the heart, with acoustic signals captured via intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) catheters10,11. However, the dynamic motion of the heart complicates the alignment between the illuminated area and the imaging plane. Alternative approaches, such as inserting optical fibers into the heart while receiving acoustic waves from the body surface, face similar challenges. Graham et al. proposed a robotic solution to compensate for heartbeat-induced motion by aligning the US transducer from the body surface for PA-based catheter tip tracking12,13. This solution was later enhanced with deep learning techniques14. Nevertheless, robotic alignment may not consistently achieve the desired imaging plane. Additionally, the setup has a limited illumination region in the US field of view, resulting in a small monitoring region unsuitable for lesion boundary detection. To address these challenges, an integrated and miniaturized PA imaging device is crucial-one that eliminates optical-acoustic alignment constraints while enabling full-array PA imaging for precise detection of ablation lesion boundaries. Several advancements in integrated PA imaging devices have been reported. PA endoscopes have been demonstrated for intravascular scanning and forward viewing15,16,17. These systems have a small field of view due to the available sensing channels. Basij et al. introduced a miniaturized integrated PA catheter based on ICE catheters. Optical fibers were aligned along the transducer, and a mirror reflection mechanism was used to align light energy with the imaging plane18. The system was later integrated with CW laser for ablation and demonstrated its applicability in detecting ablation-induced lesions in ex vivo settings19. Although previous work made significant advances in miniaturized PA instrumentation, its functionality was not evaluated under more realistic conditions. Specifically, earlier studies did not assess imaging performance within a blood medium similar to that found in the heart. Furthermore, given that typical cardiac catheters have diameters of less than 10 Fr (3.33 mm), the proposed device requires further miniaturization. An integrated catheterized PA imaging device with tip-bending navigation capability is critical for implementing PA monitoring in cardiac ablation procedures. The instrument should allow physicians to maneuver through the vessel and heart chamber to localize the imaging plane to the desired location.

In this study, we introduce a miniaturized intracardiac PA imaging catheter with all components packaged within a 4 mm (12 Fr gauge) diameter along with flexible, tip-bending capability to navigate through vessels, as shown in Fig. 1. The catheter consists of a phased-array ICE transducer and two side-firing diffusing optical fibers that illuminate the target tissue with optical energy. The laser source delivers pulsed light to the tissue, generating PA waves via the thermoelastic effect. The directional side-illumination diffusing fibers focus the light on the target tissue region, while the transducer detects the PA waves and reconstructs the image. Phantom and ex vivo studies were conducted to evaluate the device’s imaging quality and its capability to detect ablation-induced lesions. Additionally, the imaging penetration depth in blood was analyzed to evaluate the PA catheter’s applicability in intracardiac procedures.

The contribution of this paper is twofold: (1) We developed a miniaturized intracardiac PA imaging catheter with a diameter of 4 mm, which allows it to pass through vessels and maneuver inside the heart chamber; the catheter’s bending tip further enables precise navigation for monitoring intracardiac ablation therapy. (2) We conducted a comprehensive analysis to assess the device’s capability to penetrate depths in blood medium for operation within the heart chamber. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. First, we describe the design optimization and fabrication of the proposed intracardiac PA catheter, along with the algorithm for detecting ablation-induced lesions. Next, the setup for phantom and ex vivo studies evaluating the catheter is described, followed by the experimental results. The discussion highlights the advantages and limitations of the work, and the paper concludes with a summary of the findings.

Methods

Device design

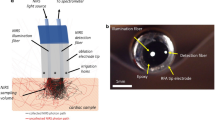

The proposed intracardiac PA imaging catheter, depicted in Fig. 2, integrates components for both light delivery and acoustic sensing to excite the PA signal and receive the generated signal, respectively. Directional diffusing fibers were used to deliver high-intensity light to the imaging plane. This approach ensures alignment between the light illumination field and the imaging plane while maintaining catheter flexibility. The optical fiber was custom-processed for diffused illumination. The fiber (FT600EMT, Thorlabs, USA) is a multimode fiber designed for tip illumination, featuring a pure silica core with a 600-µm diameter and a polymer cladding with a 30-µm thickness. To enable directional side-illumination, the fiber was processed using a specialized method described in established procedures.20. This process involved stripping the fiber buffer to expose the cladding, and selectively removing one side of the cladding to expose the core. Then the exposed core was etched with glass etching cream (Armour Etch, Armour Product, USA) for two hours, and rinsed with water. This process allows for precisely controlled emission of light in the desired direction.

A side-imaging intracardiac US transducer probe (ACUSON AcuNav, Siemens, USA) served as the signal-sensing device. This phased array probe features 64 elements and delivers high-resolution 90-degree sector images at frequencies ranging from 5 to 10 MHz. The probe catheter has a diameter of 2.7 mm (8 Fr Catheter Gauge). Custom 3D-printed housing aligns processed diffusing optical fibers on the probe parallel to the imaging arrays. The housing has a diameter of 3.8 mm and a rigid tip length of 13.9 mm. The proposed intracardiac catheter is connected to a laser system and data acquisition system, as depicted in Fig. 2. Data acquisition is managed by the Verasonics Vantage system (Vantage 128, Verasonics, USA). A Q-switched Nd:YAG laser (Q-smart 450, Quantel, USA) is used with an optical parametric oscillator (OPO) (MagicPRISM, OPOTEK, USA), emitting wavelengths ranging from 690 to 950 nm at a repetition rate of 20 Hz and a pulse duration of 5 ns. The laser beam is split by a beamsplitter (Non-Polarizing Cube Beamsplitter, Edmund Optics, USA) and separately focused by a convex lens (S-SLB-30-100P, OptoSigma, USA) before being coupled into the diffusing fiber. Fig. 2d showcases a photograph of the integrated PA catheter, highlighting its 4-mm diameter.

Design of the proposed catheter. (a) Optical component to split laser beam and couple into fiber. (b) Schematic of the system architecture. (c) Zoomed-in model of diffusing fibers integrated catheter tip to align light illumination field with imaging plane. (d) Photograph of the proposed intracardiac photoacoustic (PA) imaging catheter with under 4-mm diameter. This figure was generated using Solidworks 2023 (https://www.solidworks.com/).

Optic-acoustic alignment optimization based on finite element method simulation

The limited energy emitted from the diffusing fiber necessitates maximizing illumination at the desired depth range to enhance the quality of the resulting PA image. Consequently, we conducted a simulation-based design optimization to investigate the angular alignment between the two diffusing fibers and the US transducer. The light propagation profile of the customized diffusing fiber was obtained from our previous study21. The illumination pattern from the sidewall of a diffusing fiber can be simulated using Valo MC22, based on the finite element method (FEM) and the Monte Carlo method. Two identical light sources were placed in the simulation environment in the axial-elevational plane to replicate the design of the proposed imaging device, as shown in Fig. 3a. The light fluence distribution in a 2D space resulting from two angled light beams was analyzed to determine the optimal angular alignment between light emission and the ultrasound transducer, maximizing PA signal generation at different depths. The K-wave23 was integrated with the optical simulation to compute the PA response.

The simulation was conducted to model light fluence distribution in a saline environment to assess the baseline performance of the PA catheter. An optical absorption coefficient (\(\mu _a\)) of 0.01 cm−1 was used based on the optical property of water near 720 nm24. A minimal scattering coefficient (\(\mu _s\)) was set in the simulation software, considering that saline has negligible scattering in this wavelength range, making the attenuation coefficient approximately equal to the absorption coefficient25. At each target depth, simulations were performed for various angular alignments between the center lines of the two light emissions and the axial direction of the US transducer imaging plane. An angular range of 0-20 degrees with an intermediate step of 1 degree was selected for the simulation study. The distance between the two light sources matched the width of our US transducer sensing array to achieve a miniaturized design. A single-point US detector simulated the transducer element positioned between the two light sources. With PA excitation from two light beams, the point detector captured the PA signal of the point target, recording its signal intensity along with the angular alignment setup and target depth.

The optimized angular alignment between the two light beams to maximize PA response at each depth was studied. Fig. 3b illustrates the relationship between the PA intensity of the target at various depths under different angular alignments between light emission and the US transducer. At a 20-degree fiber rotation, a stronger PA excitation is observed in a shorter depth range (0–4 mm). PA intensity in deeper regions improves as the fibers approach parallel alignment. To optimize the PA signal at our desired depth range near 10 mm from the transducer array, an 8-degree rotation is recommended, based on the simulation study.

Ablation-induced lesion mapping using photoacoustic imaging

The lesion boundary was mapped based on the Necrotic Extent (NE) map through a three-step process. First, NE mapping was computed using the PA spectrum from multispectral PA imaging. This involved spectroscopic decomposition to distinguish the intensity distribution of ablated tissue from non-ablated tissue, using reference PA spectra8. Assuming the acquired PA spectrum is a linear combination of signals from ablated and non-ablated tissues, the contribution from each source is estimated using Eq. (1)26:

here, \(p_w\) is the measured PA intensity at the wavelength w, \(\mu _{a}\) is the absorption spectrum of contrast source at the wavelength w, W is the total number of wavelengths used, and \(m_{Ab}\) and \(m_{N-Ab}\) are the estimated composition of ablated and non-ablated tissue, respectively. This technique is widely used in blood-oxygenation mapping27,28, neurovascular mapping29, and contrast agent-enhanced imaging26,30, and enables the separation of PA signals between ablated and non-ablated tissue. Then, the NE metric quantified the extent of necrosis by calculating the ratio of ablated tissue intensity to the sum of ablated and non-ablated tissue intensities for each pixel, as shown in Eq. (2):

Next, the lesion region was binarized using a threshold value of 0.3 for the NE, and the depth of the thresholded lesion region was adjusted with a linear factor to correct for potential underestimation in lesion depth detection31. Finally, the boundary of the depth-corrected lesion region was visualized by displaying a binary lesion map based on the depth-corrected PA image. This included filtering out non-specific signal noise to enhance tissue contrast and provide a clear lesion boundary. This method enables the visualization of tissue transitions, as well as the formation and expansion of ablation-induced lesions during the procedure.

Experimental implementation

Catheter bending angle evaluation

The catheter maneuverability was tested to evaluate the flexibility of our proposed device. This original ICE catheter features two degrees of freedom for imaging array rotation, controlled by a pair of handle knobs. This design provides sufficient flexibility for imaging at desired positions and orientations within the heart chambers. Our proposed system incorporates optical fibers and their holders onto the catheter. To assess the impact of these attachments on the probe’s tip rotation manipulability, we measured the working range limits of the imaging system on both axes with the optical components attached.

Phantom study setup and procedure

We first validated the imaging capability of the proposed PA catheter through a phantom study. The PA imaging quality as illuminated by the diffusing fiber was evaluated using nylon wire as the imaging target, mounted on a 3D-printed wire holder with known geometry. The wires, with a diameter of 200 \(\mu\)m, were mounted perpendicular to the imaging plane to capture their cross-section as shown in Fig. 4. The targets were aligned at depths of 10 and 20 mm from the imaging arrays, with four targets on the first layer and two on the second. A 700-nm laser wavelength was used for PA excitation, and the acquired PA signal was beamformed using the Delay-and-Sum (DAS) algorithm32. To quantitatively evaluate the imaging quality, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) were measured at each target. The equation for calculating SNR is defined as Eq. (3):

where \(P_{peak}\) represents the PA signal amplitude across the target, and \(\sigma _{noise}\) is the standard deviation of the background noise.

Phantom study setup: (a) Target arrangement design sketch. (b) Wire phantom illuminated by diffusing fiber during PA scanning. This figure was generated using Microsoft PowerPoint (https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/powerpoint).

Ex vivo ablation lesion imaging

In addition to the phantom study, functional imaging to characterize tissue using multispectral PA was demonstrated with an ex vivo tissue sample. The capability of extracting tissue spectra and detecting ablation-induced lesions using this PA catheter was tested. The accuracy of tissue spectrum detection is critical for this catheter to be implemented in surgical guidance. An ex vivo porcine myocardial sample was ablated and then scanned with the proposed PA catheter, as shown in Fig. 5a. The ex vivo sample was acquired from a local grocery store. The ablation procedure used a 4-mm-tip irrigated catheter (Safire BLU Duo Irrigated Ablation Catheter, St. Jude Medical, USA), connected to a cardiac ablation generator (1500TR9-CP, St Jude Medical, USA). RF ablation was conducted at a 35-W setting with a temperature limit of \(40\,^{\circ }\)C. An irrigation rate of 17 mL/min was maintained during ablation. The sample was scanned in the saline bath, as shown in Fig. 5b. A total of 16 wavelengths ranging from 700 to 850 nm were used for PA excitation. This range covers the spectral differences between ablated and non-ablated tissue6,9. The non-ablated tissue spectrum matches the deoxyhemoglobin (HbR) spectrum, exhibiting a local spectral peak around 760 nm that disappears after ablation. The sPA images were beamformed with DAS algorithms, and US imaging was performed at the same location to record the tissue anatomy as a reference.

Ex vivo study setup: (a) Multispectral photoacoustic (PA) imaging sequence for ablation-induced lesion mapping. Tissue sample ablated with radiofrequency (RF) ablation catheter, followed by ultrasound (US) and PA scanning. (b) Scanning setup for ex vivo tissue in saline medium. (c) Scanning setup in blood medium.

The proposed PA catheter was further tested in a blood medium to identify the ablation-induced lesion as illustrated in Fig. 5c, simulating catheter imaging inside the cardiac chamber. Blood is a strong PA contrast source with high optical absorption. It limits the light fluence reaching the tissue surface and degrades the imaging quality. The imaging depth penetration of our imaging catheter in blood was evaluated in this study. The ablated ex vivo porcine sample was scanned in blood. Both the sample and catheter tip were submerged in porcine blood (Innovative Grade US Origin Porcine Whole Blood, Innovative Research, USA). The sample was manually aligned to multiple depths from the imaging array. US and multispectral PA imaging were acquired with wavelengths ranging from 700 to 850 nm. Images were beamformed with the DAS algorithm.

Results

Catheter bending performance

The range of tip bending of the proposed PA catheter was evaluated in this study. The maximum bending angle in each direction is shown in Fig. 6. The coordinates assignment is presented in Fig. 6a. The manipulation handle was turned individually to bend the catheter tip around a single axis, and the maximum bending angle was recorded. The catheter tip bends \(-30\,^{\circ }\) to \(56\,^{\circ }\) around the axial axis and \(-70\,^{\circ }\) to \(78\,^{\circ }\) around the elevational axis.

Maximum bending angle evaluation of the proposed PA catheter. (a) Axes assignment diagram. Maximum bending angle in the (b) X-Y plane and (c) X-Z plane. This figure was generated using Solidworks 2023 (https://www.solidworks.com/) and Microsoft PowerPoint (https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/powerpoint)..

Phantom study: resolution and contrast assessment

The imaging capability of the proposed PA catheter was validated through the phantom study. A wire target phantom was scanned with the PA catheter, and the results are displayed in Fig. 7. The acquired PA image was overlaid onto the US image collected at the same location. All six wires are clearly visible in both PA and US images, demonstrating that the proposed PA catheter is capable of high-contrast, high-resolution scanning.

During the system calibration phase, the fiber output energy was measured at 5.70 ± 0.58 mJ across wavelengths. Quantitative analysis was performed on the acquired PA image of wire targets. The signal lateral profile was extracted, and the FWHM and SNR across the targets were measured to evaluate the image resolution and contrast. The quantitative measurements are listed in Table 1. The FWHM measured across the 200 µm targets was 647.35 ± 61.60 µm, and an SNR of 27.45 ± 5.21 dB was recorded. Additionally, the SNR of the first target layer (10 mm from the transducer array) was 30.15 ± 3.02 dB, with the diffusing light beam designed to focus here.

RF ablation lesion detection in saline

The capability of the proposed PA catheter in detecting ablation-induced lesions was demonstrated. Fig. 8 displays the PA-based lesion mapping scanned by the proposed PA catheter at two different depths. The tissue surfaces were located 8 and 11 mm from the transducer array. The acquired PA image of tissue was overlaid onto the US image collected from the same location. The PA-based ablation lesion indexing indicates that the center area of the sample tissue was ablated, surrounded by non-ablated tissue, matching the morphology of the prepared sample. The lesion maps are similar between the two scans acquired from different depths. We measured the ablation-induced lesion size scanned by PA imaging and compared it with the actual lesion size. The size of the PA-detected lesion was shown in Table 2. Ablated regions were measured as 6.02 \(\times\) 4.30 mm (width \(\times\) depth) at 8-mm depth and 6.89 \(\times\) 4.14 mm at 11 mm.

A gross-pathology comparison was performed between the post-scanning sample and the necrotic region detected in PA imaging to evaluate detection accuracy. The ablated tissue sample was dissected across the line-shaped lesion to measure necrosis at four different locations to mitigate potential discrepancies caused by imaging alignment. The sliced cardiac sample was stained with 2% 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) in 0.9% saline solution for 20 min at \(37\,^{\circ }\)C to enhance the visibility of the ablation lesion. TTC is a metabolic function marker and a reliable indicator of damaged areas in experimental models. It is a colorless water-soluble dye reduced by the mitochondrial enzyme of living cells that succinate dehydrogenase into a water-insoluble light-sensitive compound (formazan) that turns normal (non-ablated) tissue deep red. In contrast, damaged (ablated) tissue remains white, indicating the absence of living cells. The average lesion size of 6.52 \(\times\) 3.88 mm was measured in gross pathology across multiple slices.

Ablation lesion mapping in blood

The proposed PA catheter was tested in a more realistic scenario with a blood medium to simulate the imaging environment inside a heart chamber. Fig. 9 displays the PA-based lesion mapping scanned by the proposed PA catheter at various tissue surface depths. The same ablated tissue sample was scanned from 4 to 12-mm depth. The tissue boundary was distinguished in the PA image, with the locations confirmed by the US image acquired at the same locations. The time gain compensation (TGC) of the US images was manually tuned during the scan to highlight the tissue. The ablated tissue was consistently observed near the center of the image on top of the tissue surface, highlighted in red pixels. The surrounding tissue was detected as non-ablated and labeled in blue. The tissue signal significantly weakened when the tissue surface was located at 12 mm depth. The detected tissue signal was limited, and the labeled lesion area was smaller than at other depths. The shape of the tissue identified in the PA image still matches with US image.

The PA-estimated lesion width and depth from the blood-medium study are presented in Table 2. The tissue sample scanned in a saline medium shows consistent PA-estimated lesion size at two depths. In blood medium scanning results, the lesion width measured between 4 and 8 mm was relatively consistent, whereas the depth varied from 3.48 to 4.64 mm. The lesion size measured at 12 mm is significantly smaller than the pathology measurement, at 3.50 mm in width and 2.32 mm in depth. This matches the qualitative assessment displayed in Fig. 9. Although direct measurement of fiber output energy in the blood is not feasible, we assume it remains consistent with the calibration measurements based on prior system validation.

Discussion

This study successfully developed and validated a miniaturized intracardiac PA imaging catheter. The device is designed to navigate through the vessels and chambers of the heart with a diameter of 4 mm and flexible tip-bending capability to monitor ablation therapy intraoperatively. The maximum bending angles demonstrate the maneuverability and flexibility of the proposed catheter, allowing it to reach the desired imaging poses within the heart chamber. The bending range confirms the catheter’s capability to effectively navigate complex cardiac anatomy, providing comprehensive imaging coverage by enabling access to a larger imaging area due to its maneuverability. Phantom and ex vivo studies validated the catheter’s imaging quality and functionality to detect ablation-induced lesions. The comprehensive analysis conducted in this study demonstrates the capability of the device to image through blood, which is crucial for its operation within the heart chamber. Phantom study results showed the proposed device is capable of acquiring high-contrast, high-resolution imaging with an average FWHM of 647.35 µm and an SNR of 27.45 dB. These results indicate that the optimized design focuses sufficient diffusing light energy to generate strong PA signals.

Ex vivo studies further demonstrated the effectiveness of the catheter in accurately detecting ablation-induced lesions. Sample scanning in the saline bath confirmed the capability of this PA catheter to perform spectral analysis and detect ablated tissue. Lesion size showed consistency in both width and depth axes between the two scanning conditions. The successful detection of ablation-induced lesions in ex vivo samples, particularly in a blood medium, demonstrates the catheter’s effectiveness in a realistic cardiac environment. Lesion sizes detected within the 8-mm range were consistent with gross pathology, validating the accuracy and applicability of the proposed device for cardiac ablation monitoring. While the tissue boundary was detected at a 12-mm depth, the detected size of the ablated region was smaller. This may have been caused by the light attenuation resulting in lower PA excitation at the depth. This result demonstrates that the diffusing fiber can emit sufficient energy to penetrate 8 mm of the blood medium and successfully distinguish spectral differences between blood and non-ablated tissue within this range.

Despite the successful demonstration, there are several challenges to this study that should be addressed in future research. First, although the proposed catheter demonstrates flexibility and maneuverability, its maximum bending angle is smaller than the bending angle of the original ICE catheter without fiber attachment. The fiber’s stiffness counteracts the tendon’s force, resulting in a larger bending radius, which may impact the accessibility of target imaging sites within the heart chamber. Future work should explore alternative fiber models with softer stiffness to enhance catheter flexibility while maintaining sufficient light delivery efficiency. Second, while the phantom and ex vivo studies validated the catheter’s functionality, they do not fully replicate the complexity of in vivo conditions. The dynamic motion of the heart and the variability in patient anatomy pose additional challenges that were not accounted for in this study. We have addressed these limitations by demonstrating PA-based ablation-induced lesion detection with in vivo beating heart conditions8, highlighting its potential applicability in the in vivo settings; however this proposed PA catheter still requires further in vivo evaluation. Finally, the current study focused on the technical feasibility and initial validation of the device. Further research is needed to evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of the catheter in clinical practice, including assessing the potential for any adverse effects from prolonged use and its compatibility with existing ablation equipment and protocols. Additionally, future work will explore the applicability of this imaging device to other clinical applications. Laser ablation has shown similar tissue PA spectral changes19, enabling lesion mapping with the same pipeline. The potential of this PA catheter for broader clinical use will be further investigated.

While the device demonstrated effective lesion detection at various depths, the imaging quality in the blood medium showed a decline at greater depths. The PA signal weakened significantly when the tissue surface was located at 12 mm, indicating a limitation in the light penetration depth. This suggests that the device may have reduced effectiveness in detecting deeper lesions within the heart. Considering a typical left-atrium radius of approximately 15 mm, current 10-mm penetration is capable of reaching most of the area. In addition, there are potential discrepancies in optical properties between in vivo blood and the blood sample used in our study, allowing our imaging setup to penetrate deeper than it would in an in vivo environment. However, during RF ablation, the irrigation at the catheter tip significantly dilutes and displaces local blood33,34. This reduces both optical absorption and scattering from the blood medium, which may work in our favor by allowing more light to penetrate the region and deliver energy to the tissue, improving the overall effectiveness of our imaging method. Future studies should incorporate a larger number of samples in the in vivo models, to further investigate imaging depth penetration. This will help evaluate the impact of physiological factors such as blood flow dynamics, cardiac motion, and tissue perfusion on imaging performance, providing a more comprehensive assessment of imaging depth limitations in real-world conditions. We plan to address blood interference more directly by incorporating a balloon solution around the imaging array in future work35,36. Inflating this balloon within the heart chamber would help displace blood from the imaging path, minimizing its impact on signal quality and further enhancing the ability to detect lesions at greater depths. This design optimization could further improve the imaging accuracy of this system.

Conclusion

In this paper, we present miniaturized intracardiac PA imaging with a diameter of 4 mm and flexible tip-bending capability to guide cardiac ablation therapy. The device demonstrated high-resolution imaging capabilities, which are essential for precise monitoring and guidance during A-fib ablation procedures. Phantom and ex vivo studies validated its effectiveness in detecting ablation-induced lesions, underscoring its potential to provide ablation feedback during procedure. Our findings highlight the potential of PA imaging as a valuable tool for guiding intraoperative clinical cardiac ablation procedures. Future studies will further explore its clinical integration and optimization for broader applicability in electrophysiology interventions.

Data availability

The data that support the findings during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Saleh, K. & Haldar, S. Atrial fibrillation: A contemporary update. Clin. Med. J. Roy. College Phys. Lond. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2023-23.5.Cardio2 (2023).

Morillo, C. A., Banerjee, A., Perel, P., Wood, D. & Jouven, X. The current epidemic, atrial fibrillation. J. Geriatric Cardiol. 14, 195–203 (2017).

Peters, D. C. et al. Recurrence of atrial fibrillation correlates with the extent of post-procedural late gadolinium enhancement. A pilot study. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2, 308–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.10.016 (2009).

Nakagawa, H. & Jackman, W. M. The role of contact force in atrial fibrillation ablation. J. Atrial Fibril. https://doi.org/10.4022/jafib.1027 (2014).

Santoro, A., Romano, A. & Lamberti, F. Steam pop during cavo-tricuspid isthmus ablation shown by intracardiac echocardiography. J. Cardiol. Cases 23, 13–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jccase.2020.08.002 (2021).

Dana, N., Biase, L. D., Natale, A., Emelianov, S. & Bouchard, R. In vitro photoacoustic visualization of myocardial ablation lesions. Heart Rhythm 11, 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.09.071 (2014).

Beard, P. Biomedical photoacoustic imaging review. Interface Focus 1, 602–631. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2011.0028 (2011).

Gao, S. et al. Cardiac-gated spectroscopic photoacoustic imaging for ablation-induced necrotic lesion visualization. J. Biophoton. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbio.202400126 (2024).

Gao, S., Ashikaga, H., Mansi, T., Halperin, H. R. & Zhang, H. K. Photoacoustic necrotic region mapping for radiofrequency ablation guidance. 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1109/IUS52206.2021.9593388 (IEEE, 2021).

Iskander-Rizk, S., Kruizinga, P., van der Steen, A. F. W. & van Soest, G. Spectroscopic photoacoustic imaging of radiofrequency ablation in the left atrium. Biomed. Opt. Express 9, 1309. https://doi.org/10.1364/boe.9.001309 (2018).

Iskander-Rizk, S. et al. Real-time photoacoustic assessment of radiofrequency ablation lesion formation in the left atrium. Photoacoustics 16, 100150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacs.2019.100150 (2019).

Graham, M. et al. In vivo demonstration of photoacoustic image guidance and robotic visual servoing for cardiac catheter-based interventions. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 39, 1015–1029. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2019.2939568 (2020).

Graham, M. et al. Photoacoustic image guidance and robotic visual servoing to mitigate fluoroscopy during cardiac catheter interventions. Proceedings of SPIE 11229, Advanced Biomedical and Clinical Diagnostic and Surgical Guidance Systems XVIII, 112291E (21 February 2020)11229, 80–85, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2546910 (2020).

Gubbi, M. R., Assis, F., Chrispin, J. & Bell, M. A. L. Deep learning in vivo catheter tip locations for photoacoustic-guided cardiac interventions. J. Biomed. Opt. 29, S11505. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.29.S1.S11505 (2023).

Ansari, R., Zhang, E. Z., Desjardins, A. E. & Beard, P. C. All-optical forward-viewing photoacoustic probe for high-resolution 3d endoscopy. Light Sci. Appl. 2018 7:1 7, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-018-0070-5 (2018).

Guo, H., Li, Y., Qi, W. & Xi, L. Photoacoustic endoscopy: A progress review. J. Biophotonics 13, e202000217. https://doi.org/10.1002/JBIO.202000217 (2020).

Yang, J.-M. et al. Photoacoustic endoscopy. Opt. Lett. 34, 1591. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.34.001591 (2009).

Basij, M. et al. Miniaturized phased-array ultrasound and photoacoustic endoscopic imaging system. Photoacoustics 15, 100139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacs.2019.100139 (2019).

Basij, M. et al. Integrated ultrasound and photoacoustic-guided laser ablation theranostic endoscopic system. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2022.3184495 (2022).

Ai, M. et al. Photoacoustic tomography for imaging the prostate: A transurethral illumination probe design and application. Biomed. Opt. Express 10, 2588. https://doi.org/10.1364/boe.10.002588 (2019).

Gao, S. et al. Laparoscopic photoacoustic imaging system based on side-illumination diffusing fibers. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2023.3279772 (2023).

Leino, A. A., Pulkkinen, A. & Tarvainen, T. Valomc: A Monte Carlo software and Matlab toolbox for simulating light transport in biological tissue. OSA Contin. 2, 957. https://doi.org/10.1364/osac.2.000957 (2019).

Treeby, B. E. & Cox, B. T. k-wave: Matlab toolbox for the simulation and reconstruction of photoacoustic wave fields. J. Biomed. Opt. 15, 021314. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.3360308 (2010).

Pope, R. M. & Fry, E. S. Absorption spectrum (380–700 nm) of pure water II. Integrating cavity measurements. Appl. Opt. 36, 8710–8723 (1997).

Pegau, W. S., Gray, D. & Zaneveld, J. R. V. Absorption and attenuation of visible and near-infrared light in water: Dependence on temperature and salinity. Appl. Opt. https://doi.org/10.1364/ao.36.006035 (1997).

Zhang, H. K. et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen-targeted photoacoustic imaging of prostate cancer in vivo. J. Biophotonics 11, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbio.201800021 (2018).

Li, M., Tang, Y. & Yao, J. Photoacoustic tomography of blood oxygenation: A mini review. Photoacoustics 10, 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacs.2018.05.001 (2018).

Gao, S., Ma, X. & Zhang, H. K. Robot-assisted wide-area photoacoustic system. In: 2023 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS) 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1109/IUS51837.2023.10307874 (2023).

Gao, S. et al. Intraoperative laparoscopic photoacoustic image guidance system in the Da Vinci surgical system. Biomed. Opt. Express https://doi.org/10.1364/boe.498052 (2023).

Serebrennikova, L. et al. Feasibility of spectra-based quantification algorithm for non-linear photoacoustic contrast agents.. Photons Plus Ultrasound Imaging Sens. 12379, 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2650607 (2023).

Gao, S. et al. Enhancing boundary detection of radiofrequency ablation lesions through photoacoustic mapping. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68046-x (2024).

Gao, S. et al. Acoustic-resolution photoacoustic microscope based on compact and low-cost delta configuration actuator. Ultrasonics 118, 106549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultras.2021.106549 (2021).

Chopra, N. et al. Clinical impact of saline volume infused through irrigated-tip ablation catheter in low acuity paroxysmal atrial fibrillation ablation patients. J. Atrial Fibril. https://doi.org/10.4022/jafib.2093 (2018).

Winbury, M. M. & Howe, B. B. Changes in intramyocardial oxygen tension and local electrograms produced by coronary occlusion. Recent Adv. Stud. Cardiac Struct. Metab. 12, 233–236 (1976).

Zhu, Y. et al. Prototype endoscopic photoacoustic-ultrasound balloon catheter for characterizing intestinal obstruction. Biomed. Opt. Express https://doi.org/10.1364/boe.456672 (2022).

Huang, Y. et al. A colonoscope-compatible photoacoustic and ultrasonic imaging catheter: Initial clinical study in human subjects. Photons Plus Ultrasound Imaging Sens. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3000638 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Worcester Polytechnic Institute internal fund: the Transformative Research and Innovation, Accelerating Discovery (TRIAD) grant; and the National Institutes of Health funding grant numbers: R01CA134675, DP5OD028162, R01EB022011, R01EB030539, R01DK133717.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G. and H.K.Z. conceptualized the study and established the experimental design. S.G. led the design, conducted the experiments, analyzed the data, and prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. Y.W. contributed to design, prototyping, and manuscript editing. R.M. supported data analysis. H.A. and H.R.H. provided clinical insights and guidance for the project. Y-H.K. and M.M. offered technical guidance throughout the study. H.K.Z. supervised the project, provided financial support, and ensured overall guidance and oversight. All authors actively participated in the critical review of the data and critical review and editing of the manuscript, ensuring its accuracy and quality. All authors have given their approval for the submission of this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Y.-H.K., is a scientist and employee of Siemens Healthineers USA. The other authors have no known conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

Disclaimer

The concepts and information presented in this paper are based on research results that are not commercially available. Future availability cannot be guaranteed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, S., Wang, Y., Murakami, R. et al. Miniaturized side-firing intracardiac photoacoustic imaging catheter for monitoring radiofrequency ablation. Sci Rep 15, 17427 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98970-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98970-5