Abstract

With the advancement of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology, UAVs, such as multi-rotor drones, have found widespread application in wireless sensor networks. In scenarios where multiple UAVs collaborate to gather sensor data from the field, it is essential to establish a path planning model that incorporates an accurate energy consumption model for these UAVs. The power consumption of a multi-rotor drone varies depending on its flight state. When UAVs traverse various locations, it is not only the power required for steady-level flight that must be considered, but also the power necessary for acceleration, deceleration, climbing, and turning. This paper presents a path planning model for multiple UAVs, termed the Multi-UAV Path Planning Considering Multiple Energy Consumptions (MUAVPP-MEC). The solution derived adheres to the constraint that UAV flight energy consumption should not exceed the maximum stored energy, with the goal of minimizing the total flight time across all UAV paths. To tackle the MUAVPP-MEC, this study proposes an improved Bee Foraging Learning Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm (IBFLPSO), which integrates the bee-foraging algorithm into the particle swarm optimization framework. The IBFLPSO facilitates an efficient real-number encoding and greedy segmenting sequence decoding strategy, translating the solution space of the problem into the search space of the algorithm. To improve the optimization capabilities of the algorithm, IBFLPSO utilizes the energy-constrained 2-opt as a local search operator. In Experiment 1, the proposed model and algorithm are validated through three distinct case studies, demonstrating the stability and efficacy of the methods. It is clearly observed that as the number of collection points increases, both the total cruising time and energy consumption of the model rise significantly, thus confirming the accuracy of the model. In Experiment 2, when compared with four other algorithms, IBFLPSO outperforms them in both the optimal and average solutions. Specifically, the optimal solution of IBFLPSO is 54.64%, 49.45%, 25.78%, and 22.92% better than those of the traditional PSO algorithm, PSO-2OPT algorithm, GA, and BFLPSO, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the advancement of drone technology, aerial devices have become faster, more user-friendly, and cost-effective. This has enabled drones to find widespread application across various fields. When integrated with wireless sensor networks, they can collaborate to offer a solution that is both reliable and resilient. This synergy not only enhances the efficiency and scope of data collection but also strengthens the system’s stability and adaptability, ensuring high performance even in complex or harsh environments. These advantages have resulted in the frequent deployment of UAVs in applications such as long-distance data collection1, route inspection2, and logistics distribution3. However, determining the optimal path for asynchronous UAVs to maximize the acquisition of sensing information while adhering to energy constraints remain a significant challenge4,5,6.

Initially, several scholars focused on optimizing the path of individual UAVs7,8,9. Mignardi et al.7 treated UAVs as mobile base stations, optimizing their paths under the constraints of limited wireless resources. Xie et al.8 addressed the problem of planning an optimal path for a single UAV to efficiently cover multiple, separated convex polygonal regions. Alemayehu et al.9 investigated the impact of sensor failures due to node or link faults, aiming to enhance the fault tolerance and data acquisition efficiency of a single UAV. As UAV applications expanded, the issue of multi-UAV collaboration attracted increasing scholarly attention10,11,12. For example, Ren et al.10 suggested that each UAV could be launched from one node and retrieved at another, employing heuristic dynamic programming to address UAV scheduling on fixed routes. Chen et al.11 explored the use of multiple UAVs or a UAV network for remote sensing applications, focusing on the rapid acquisition of large-scale, ultra-high-resolution data. Jiang et al.12 considered factors such as UAV energy consumption, payload, and distribution center conditions to minimize the total distribution cost, developing a multi-type, multi-distribution UAV model to enhance UAV delivery capabilities. Given the limited battery capacity of UAVs, some researchers shifted their focus to the energy consumption of UAV flights in path planning13,14,15. For instance, Stodola13 addressed the path planning of UAV formations for sustained surveillance of specific areas. Kyriakakis et al.14 proposed a hybrid algorithm variant to tackle UAV path planning for pickup and delivery tasks. Lee et al.15 developed a multi-agent system capable of multi-path planning, incorporating the energy consumption of UAV logistics deliveries. Huang et al.16 established a model for multi-UAV inspection route planning in wind farms, aimed at minimizing total flight energy consumption. Although these studies accounted for energy consumption during steady flight, UAVs, in practice, operate in a variety of flight states, each with distinct energy demands.

To ensure UAVs can return to base smoothly, it is crucial to consider the energy consumption of different flight states and design precise flight energy consumption models. Dong et al.17 derived accurate UAV energy consumption calculations under various conditions of turning angles and flight speeds, and based on this model, designed a path planning model for individual UAVs. Zhu et al.18 considered the maximum curvature constraints of UAV flight, proposing a rapid assessment path model for multiple UAVs post-earthquake. To reduce the total energy consumption of shipborne UAVs collecting sensor data, Huang et al.19 considered factors such as wind-hover, data collection, and wireless communication, proposing a UAV path planning model; Huang et al.20 also developed an automatic inspection system model for UAVs in offshore wind farms assisted by MEC servers and near-Earth orbit satellites, optimizing the total inspection energy consumption. However, previous studies did not consider multiple energy consumption due to steady level flight, acceleration, deceleration, turning and climbing in multiple unmanned aerial vehicles path planning. To construct an accurate flight energy consumption model, this paper considers the energy consumed during steady horizontal flight, acceleration, deceleration, turning, and climbing, aiming to minimize the total cruising time of UAV paths, and proposes a Multiple unmanned aerial vehicles path planning model marked as MUAVPP-MEC.

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is widely employed to solve combinatorial optimization problems, such as the path planning of multiple unmanned aerial vehicles21,22,23. However, traditional PSO faces challenges with slow convergence and low precision when tackling large-scale discrete problems. In response to these limitations, Chen et al.24 introduced a more effective Bee-Foraging Learning Particle Swarm Optimization in 2021. Building upon this, the present paper proposes an improved Bee-Foraging Learning Particle Swarm Optimization for MUAVPP-MEC, incorporating an efficient encoding and decoding strategy to transform problem-solving spaces into algorithmic search spaces, and utilizing an energy-constrained 2-opt local search strategy to enhance the algorithm’s optimization capabilities.

In summary, the contributions of this paper are as follows.

In the context of UAV data collection, this study considers the energy consumption associated with UAVs ascending to various altitudes at different collection points. Additionally, as rotary UAVs alter their flight direction to target different angles, angular energy consumption must also be calculated. Consequently, this paper introduces a model for Multi-UAV Path Planning Considering Multiple Energy Consumptions (MUAVPP-MEC). This model takes into account energy consumption during steady-level flight, acceleration, deceleration, ascent, and turning, all under the constraint of maximum energy storage, with the aim of minimizing the total cruising time of UAVs. The MUAVPP-MEC model is validated through multiple instance sizes in Experiment 1.

Tailored to the characteristics of the MUAVPP-MEC, this paper designs an Improved Bee Foraging Learning Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm (IBFLPSO) to solve the problem. The algorithm builds upon Bee Foraging Learning Particle Swarm Optimization25,26, incorporating an efficient encoding and decoding strategy that translates problem solution spaces into algorithmic search spaces. The integration of an energy-constrained 2-opt local search further enhances the algorithm’s optimization capabilities. In Experiment 2, IBFLPSO was compared with four other algorithms, demonstrating superior performance in both the optimal and average solutions.

The structure of this paper is as follows: “Mathematical models” section introduces the MUAVPP-MEC model. “The proposed algorithm” section details the IBFLPSO algorithm used to solve the MUAVPP-MEC. “Experiment and analysis” section presents multiple cases of varying scales to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed model and solution method. Finally, “Conclusions and future works” section concludes the paper and discusses potential directions for future research.

Mathematical models

In this section, the details of the model are presented, along with the definition of the optimization objectives and associated constraints.

Problem description

The MUAVPP-MEC involves several nodes, with one serving as the central point and the others as data collection points, each positioned at different altitudes. A limited number of UAVs are stationed at the central point, each having a maximum battery capacity. These UAVs are tasked with flying a route through multiple data collection points to complete data acquisition tasks. The cruising process begins with departure from the central point, followed by acceleration to cruising speed and subsequent steady flight. Upon reaching each data collection point, IoT sensor data is gathered via onboard equipment. If energy permits, the UAV maintains its speed and turns toward the next collection point; otherwise, it returns to the central point, decelerating to a stop as it approaches the destination. The schematic diagram, shown in Fig. 1, illustrates the paths of two UAVs traversing nine data collection points. In this process, the varying altitudes of each node are considered, and the ascent and descent of UAV1 are depicted in Fig. 2. In this figure, UAV1 collects data from four collection points before returning to the starting point.

To precisely define the data model for this problem, the following assumptions are made:

-

1.

UAVs start from rest, accelerating at 1 m/s2 to a predetermined speed, after which they transition to steady flight. The distance covered during the acceleration phase (DAcc) and the time required (TAcc) are fixed values. As UAVs approach their targets, they decelerate from the set speed to zero at a rate of 1 m/s2. The distance covered during the deceleration phase (DDec) and the time required (TDec) are also fixed values.

-

2.

The energy consumed during acceleration, steady horizontal flight, and deceleration is determined by polynomial equations17 derived from empirical data. Since both the acceleration and deceleration phases are fixed, the energy consumed during these phases (EAcc and EDec) are set values. The energy consumed during steady flight is the product of the power required and the flight time.

-

3.

In addition to the distance-based energy, the energy consumed during flight also accounts for angular energy and climbing energy. Angular energy is a linear function17 of the flight turn angle. The climbing energy consumed when a UAV ascends from a lower to a higher node depends on the ascent height, UAV mass, and gravitational acceleration. No energy is consumed when descending from a higher to a lower node.

Objective function

The objective of the MUAVPP-MEC model is to minimize the total cruising time of the UAVs, as outlined in Eq. (1), which functions as the optimization criterion.

In Eq. (1), the UAV accelerates to a predetermined speed before transitioning into steady flight and decelerates to zero speed as it approaches the target. The distances flown during the acceleration and deceleration phases are denoted by DAcc and DDec, respectively, with the corresponding times required being TAcc and TDec. The cij represents the distance from node i to node j, and \(x_{ijk}\) are the decision variables, where 1 indicates that UAV k flies from node i to node j, and 0 otherwise. While Eq. (1) serves as the objective function of our Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) problem, in the IBFLPSO algorithm we propose, it forms part of the fitness function. Additional penalty terms, as outlined in Eq. (14) in “Fitness function” section, exist to suppress infeasible solutions during the search process in the solution space of IBFLPSO.

Constraint conditions

Path continuity constraints

A data collection point can be serviced by only one UAV, as specified in Eq. (2). No more than K UAVs may depart from the central point, as defined in Eq. (3). The number of UAVs arriving at and departing from each node must be balanced, as indicated in Eq. (4). Once a UAV reaches a node, it provides services as described in Eq. (5). Equation (6) is employed to prevent the formation of sub-loops.

Energy consumption constraints

Similar to literature27, the total energy consumption for UAV k comprises its distance energy consumption \(EDist_{k}\), angular energy consumption \(EAngl_{k}\), and climbing energy consumption \(EClimb_{k}\). The total energy consumption of a UAV must not exceed the maximum capacity of its battery, as stipulated in Eq. (7).

Distance energy consumption

After accelerating to the designated speed and entering steady flight, the UAV decelerates to zero speed as it approaches the target. The distances covered during the acceleration and deceleration phases are DAcc and DDec, respectively, with the energy required for these phases being EAcc and EDec, respectively. The distance remaining between the acceleration and deceleration phases of the UAV’s journey is covered at a constant cruising speed. SConst represents the constant cruising speed of the UAV, and PConst denotes the power required by the UAV during the steady flight phase. The energy consumption during steady flight is the product of the steady flight time and the required power, as specified in Eq. (8).

Angular energy consumption

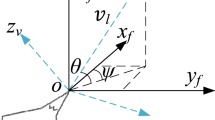

Assume that nodes i, j, and l are not aligned linearly. The UAV flies from node i to node j and then turns towards node l. The angle between the extension line of i and j and the line segment jl is the rotation angle of the ijl flight, denoted as \(\theta _{ijl}\), as illustrated in Fig. 3.

According to literature28, fixed-wing UAVs incur additional energy consumption when changing direction, compared to straight flight at the same speed. To alter its flight direction, a fixed-wing UAV must roll into a banked position to counteract the centrifugal acceleration. The instantaneous power required for a banked level turn is determined by the speed, tangential acceleration, and centrifugal acceleration28. In contrast, rotary-wing UAVs can change direction with a constant angular velocity. According to literature17, when a rotary-wing UAV turns at an angular velocity \({\omega _t}\), the relationship between the energy consumption during the turn and the turning angle can be expressed as Eq. (9):

In Eq. (9), \(E_t\left( \theta \right)\) represents the energy consumption of the UAV at a turning angle \(\theta\), and \(P_t\) denotes the power consumed by the UAV during the turn. In literature17, experimental designs were used to determine the UAV’s power \(P_t\) during turning. The experimental results reveal that the energy consumption during flight is linearly related to the turning angle, with angular acceleration having a minimal effect on the energy consumption. This linear relationship is represented by \(CAng_{1}\theta _{ijl}+CAng_{2}\), where \(CAng_{1}\) and \(CAng_{2}\) are two constants obtained by linear fitting. It is assumed that for UAV k traveling from i to j to l, the energy consumed during the turn at node j is a linear function of the flight’s turning angle \(\theta _{ijl}\)17. The angular energy consumption for UAV k is outlined in Eq. (10).

Climbing energy consumption

When a UAV ascends from a lower to a higher node, it incurs additional energy consumption related to the altitude change. According to literature29,30, climbing energy consumption, i.e., the vertical power consumption, can be modeled as \(E_\textrm{v} = M\times G\times \Delta h\), where \(\Delta h\) represents the upward altitude change. In terms of the drone’s power output, as stated in literature31,32, power transfer efficiency must be considered to represent the ratio between the power output from the battery and the power supplied to the rotors of the drone. The total energy consumption for climbing during the flight is computed as shown in Eq. (11)32.

What needs to be illustrated is that when a UAV carries a payload, such as an edge computing motherboard, the mass of the UAV increases, thereby incurring higher consumption of distance energy, angular energy, and climbing energy. In such cases, the values of PConst, EAcc and EDec in Eq. (8), the values of \(CAng_{1}\) and \(CAng_{2}\) in Eq. (10), and the value of M in Eq. (11) may need to be adjusted to higher corresponding values.

The proposed algorithm

This chapter initially outlines the fundamental concepts and framework of the improved bee foraging learning particle swarm optimization algorithm (IBFLPSO) employed in this study. It then details the encoding and decoding strategies implemented, along with the methodology for calculating the fitness function. Finally, the procedural flow of the IBFLPSO is illustrated through a flowchart.

Bee-foraging learning particle swarm optimization

Traditional particle swarm optimization (PSO)33 is a stochastic, parallel algorithm that leverages both the global best and individual historical bests to update the velocity and position of particles. At the outset, PSO initializes a set of particles, each characterized by its position, velocity, and personal best. These particles iteratively adjust their velocity and position by learning from both their individual best solutions and the global best solutions, progressively moving toward the optimal solution. The position update formula is expressed as follows:

The variables \(pv_{i}(t)\) and \(px_{i}(t)\) denote the velocity and position of the i-th particle at generation t, respectively, while \(pv_{i}(t+1)\) and \(px_{i}(t+1)\) represent the velocity and position in the subsequent generation, \(t+1\). The terms \(pbest_{i}(t)\) and \(gbest_{i}(t)\) refer to the individual best position and global best position, respectively. The parameter w signifies the inertia factor, whereas \(c_{1}\) and \(c_{2}\) are learning coefficients, and \(pr_{1}\) and \(pr_{2}\) are random numbers in the range [0, 1]. It is important to note that the population in PSO tends to exhibit homogeneity, which often results in premature convergence, thereby trapping the algorithm in local optima. To mitigate this issue, Chen et al.24 introduced the Bee-Foraging Learning model (BFL) into PSO, culminating in the creation of the BFL-PSO algorithm. This algorithm executes a three-stage learning and optimization process: the initial learning stage, the dominance reinforcement stage, and the scout stage.

In brief, the initial learning stage resembles the traditional PSO algorithm, where each particle moves according to its velocity and position update rules to find a better solution. This process is primarily optimized based on the particle’s personal best position (\(pbest_{i}\)) and the global best position (\(gbest_{i}\)), and its mathematical formulation aligns with Eq. (12). The dominance reinforcement stage strengthens the search in the regions around particles with higher fitness, meaning that particles with higher fitness are more likely to be selected for further exploration, allowing for a deeper investigation of these promising areas to uncover potential high-quality solutions, thereby improving the solution quality. This step enhances the algorithm’s development capability, with the mathematical formula provided in Eq. (13). First, the fitness value \(fit(px_{i})\) of each particle is calculated, followed by \(f(pbest_{i})\), based on the fitness value of its \(pbest_{i}\). Then, the selection probability of the i-th particle is computed based on the fitness values. The scout stage, on the other hand, targets particles that have failed to improve their \(pbest_{i}\) after multiple iterations and are thus stuck in a stagnation state. These particles enter the scout learning phase, where they are reinitialized, meaning their velocity and position are randomly generated with new values, introducing new diversity into the system. This step provides the algorithm with the ability to escape local optima and ensures that, after prolonged stagnation, the algorithm can explore new solution spaces, thereby enhancing the global search efficiency.

In conclusion, the three stages work together to enable the BFL-PSO algorithm to achieve an effective balance between global and local search in complex optimization problems. The initial learning stage guides the particle search using both individual and global best information. The dominance reinforcement stage improves solution quality by thoroughly exploring high-potential areas. The scout stage introduces new diversity by reinitializing stagnant particles, preventing premature convergence of the algorithm. This multi-stage search strategy significantly enhances the performance of the BFL-PSO algorithm in solving complex optimization problems, making it highly suitable for solving the proposed MUAVPP-MEC model.

Improved bee foraging learning particle swarm optimization

Encoding and decoding strategies

The particle navigates the \(n-1\) dimensional search space in pursuit of the global optimum. This search space is derived from literature34, spanning the range \([-100,100]^{n-1}\). The encoding rule established in this paper specifies that each particle is represented as a real-number vector in \(n-1\) dimensions, corresponding to the number of collection points, with each component confined within the range [− 100, 100]. Figure 4 illustrates this configuration, where each component \(x_{i, 1},x_{i, 2},\ldots ,x_{i, k},\ldots ,x_{i,n-1}\) of particle i lies within the bounds \(-100\le x_{i, k}\le 100, 1\le k\le n-1\), as depicted in Fig. 4.

The decoding procedure is outlined in detail as follows. The process consists of obtaining the sequence, segmenting the sequence, and optimizing the path.

Obtaining the sequence

The particle position vector is a real-number vector. The first step in the decoding process is to convert this real-number sequence into an integer sequence representing the collection points. The components of the real-number vector are sequentially numbered and then sorted according to their values, resulting in a sequence of component indices that correspond to the collection points. The node sequence obtained through this sorting process is shown in Fig. 5.

Segmenting the sequence

The preceding step converts the individual’s real-number encoding into an \(n-1\) dimensional integer node sequence. In the solution space, the route of a single UAV is represented using a path representation method35. The node sequence can be viewed as the interconnected collection point sequence of the cruising paths of multiple UAVs. For instance, the collection point sequence (4, 1, 5, 2, 8, 7, 3, 9, 6) represents the interconnected inspection paths of two UAVs, requiring the algorithm to divide the sequence into two segments, such as \(R_{1}\) = (0, 4, 1, 5, 2, 8, 0) and \(R_{2}\) = (0, 7, 3, 9, 6, 0). To finalize the multi-UAV cruising distance planning, the algorithm employs a greedy sequence segmentation decoding method. This strategy is regulated by the energy consumption required for distance, angle, and altitude changes, which must not exceed the UAV’s total battery capacity. Additionally, the calculation of distance-based energy consumption accounts for the distinct phases of acceleration, steady flight, and deceleration.

To illustrate the segmentation process, a 5-node example is constructed, where node information is as follows: (0,1850, 1750, 0), (1, 1050, 2900, 47), (2, 900, 1650, 105), (3, 500, 350, 8), (4, 2400, 1300, 132). Each node’s four numbers represent the index, x-coordinate, y-coordinate, and node altitude, respectively, with node 0 serving as the central point and the others as collection points. Constants for distance energy consumption are as follows: SConst = 15 m/s, PConst = 429.8705 VA, DAcc = 112.5 m, EAcc = 6096.3 W, DDec = 112.5 m, EDec = 4944.1875 W. Parameters for angular energy consumption are as follows: \(CAng_{1}\) = 5.3316, \(CAng_{2}\) = 104.65. Parameters for climbing energy consumption are as follows: M = 3.8 kg, G = 9.8 \(\text {m/s}^{2}\), \(\mu\) = 0.74, and the UAV battery’s maximum capacity Q = 200,000.0 J. s is defined as the current position index in the node sequence. A path matrix, denoted as Route, is used to store multiple cruising routes, with the number of rows equal to the number of available UAVs and the number of columns equal to \(n+1\).In summary, IBFLPSO achieves the transformation from the problem-solving space to the algorithm’s search space through an effective encoding strategy. This strategy maps the UAV’s route combinations to the particle position vectors in the algorithm’s search space, enabling the algorithm to efficiently handle and optimize these solutions.

The detailed process of the greedy sequence segmentation decoding method is illustrated in Fig. 6.

Given the node sequence 2, 1, 3, 4, the decoding steps are as follows.

STEP 1 The UAV departs from node 0 and proceeds to node 2, calculating the remaining energy consumption. The current node is now node 2.

STEP 2 Node 1 is designated as the target. The energy required from node 2 to node 1 is first calculated, followed by the remaining energy from node 1 to node 0. If the remaining energy is greater than 0, node 1 becomes the current node.

STEP 3 Node 3 is designated as the target. The energy required from node 1 to node 3 is calculated, followed by the remaining energy from node 3 to node 0. If the remaining energy is less than 0, indicating that the UAV cannot reach node 3, it directly returns to the central point from node 1, generating the path Route[0] = 0,2,1,0.

STEP 4 The UAV departs from node 0 with its remaining energy equal to the maximum storage capacity of the battery and proceeds to node 3.

STEP 5 Steps 1 through 4 are repeated, resulting in the generation of the path Route[1] = 0,3,4,0.

Energy-constrain 2-opt path optimization

The results are subjected to energy-constrained 2-opt local optimization36. Each generated path undergoes 2-opt local optimization, taking into account that energy consumption for angle changes and altitude adjustments may increase on a shorter path. If the energy consumption of the optimized path exceeds the UAV’s maximum battery capacity, the new path is discarded, and the original path is retained.

Fitness function

In accordance with the problem definition presented in “Mathematical models” section, the MUPP-AEC algorithm utilizes a corresponding fitness function to evaluate the particle swarm, thereby selecting the most optimal individuals. The fitness function is defined as:

The Penalty in Eq. (14) is a large integer. \(EMgn_{k}\) represents the Energy Margin for UAV k to handle operational challenges, which increases the energy consumption of the drones due to factors such as varying weather conditions or sensor malfunctions. Therefore, the lower the cost of MUPP-AEC, the better the fitness, providing the particle with a higher probability of replacing the existing particle during the algorithm’s iterative process.

Algorithm flow

The flow diagram of the IBFLPSO algorithm is presented in Fig. 7. The first stage, initialization, involves randomly initializing particles, evaluating their fitness, and updating the swarm’s global optimum based on this fitness. Subsequently, BFLPSO is used to optimize the particles. The aforementioned encoding strategy is applied, followed by decoding using the 2-opt algorithm. The algorithm checks whether 500 consecutive iterations have been performed, and if so, it outputs the optimal solution and terminates. The complexity of the approach mainly depends on the complexity of the BFL discussed in “Bee-foraging learning particle swarm optimization” section, the decoding strategies in “Encoding and decoding strategies” section, and the energy-constrained 2-opt path optimization in “Energy-constrain 2-opt path optimization” section, with complexities of O(n), O(\(n^2\)) and O(\(n^2\)), respectively. Therefore, the overall complexity of the IBFLPSO algorithm is O(\(n^2\)).

Experiment and analysis

Experimental cases and simulation environment

For the simulation experiments, this study employed a hexacopter model X4108, outfitted with a battery capacity of 10,000 mAh and a voltage of 11.1 V, yielding an effective energy capacity of 399,600 J. The experimental dataset incorporates case studies from the literature37, with coordinate values scaled by a factor of 50, and altitude values generated via a random strategy, with the range of random numbers set between 0 and 150 m. The model parameters are presented in Table 1, with angular energy consumption data drawn from literature17, and climbing energy consumption referenced from literature38,39. The simulation environment was configured on a Windows 10 platform, supported by an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-10400F CPU @ 2.90GHz, complemented by 16 GB of RAM. To ensure consistency in analysis conditions, the population size for each algorithm was set to 40, with each algorithm undergoing 500 iterations. In pursuit of robustness and dependable results, each algorithm was independently executed 10 times across various case scenarios.

Experimental results and analysis

Experiment 1: model analysis

To assess the efficacy of the MUAVPP-MEC model, this experiment incorporated three case studies, each with 30, 40, and 50 collection points, respectively. The outcomes of these cases, resolved using the IBFLPSO, are presented in Table 2. The data presented in this table indicates that, when solving Case Study 1, the MUAVPP-MEC model exhibited the most consistent total cruising time and energy consumption. As the number of collection points increased to 40, compared to Case Study 1, the average total cruising time rose by 66.47%, while the average total energy consumption increased by 65.87%. In the larger Case Study 3, the average total cruising time amounted to 3831.86 seconds, with a total energy consumption of 1,728,929 Joules. Figures 8 and 9 visually illustrate these findings, providing comparisons of the optimal solution times and total energy consumption across different case studies over ten iterations.

As depicted in Figs. 8 and 9, with the expansion of the collection points, both the total cruising time and energy consumption of the UAVs exhibited a substantial increase. This aligns with real-world UAV flight scenarios, thereby indirectly confirming the accuracy of our model. The optimal solutions for the three cases are presented in Fig. 10.

As shown in Fig. 10, Case Studies 1, 2, and 3 require 2, 3, and 5 UAVs, respectively, to collect data, with each UAV following a distinct, non-intersecting flight path. To evaluate the scheduling effectiveness of the MUAVPP-MEC model, this experiment centers on the optimal solution from Case Study 1, as outlined in Table 3.

As shown in Table 3, UAV1 departs from the starting point, visits 26 distinct collection points, and returns to the origin, while UAV2 follows a similar route, visiting 4 unique points. Both UAVs efficiently manage their distance, angular, and climbing energy consumption, returning before their battery reserves are exhausted, thereby adhering to the model’s constraints. These results affirm that IBFLPSO is capable of effectively solving the MUAVPP-MEC model.

Experiment 2: comparison of algorithms

To evaluate the optimization performance of the proposed algorithm, five algorithms were employed to solve the MUAVPP-MEC model, and the resultant data were compared. The first algorithm is a traditional PSO, the second is a traditional PSO enhanced with the energy-constrained 2-opt modification (denoted as PSO-2OPT), the third is the GA algorithm, the fourth is the BFLPSO algorithm, and the fifth is the proposed method. All five algorithms were tested on a 51-sample point case. The iterative processes for obtaining optimal solutions with these algorithms are shown in Fig. 11.

Figure 11 shows that IBFLPSO outperforms the other four algorithms in terms of convergence speed and effectiveness. Additionally, Figs. 12 and 13 provide a detailed comparison of the results from ten independent experiments involving the five algorithms.

As shown in Figs. 12 and 13, IBFLPSO consistently outperforms PSO-2OPT, PSO, and BFLPSO across ten independent experiments. In comparison with the GA algorithm, IBFLPSO demonstrates clear superiority in seven out of the ten experiments. The specific experimental data are detailed in Table 4.

As detailed in Table 4, in the optimal solution, IBFLPSO saved 1,596,280 joules compared to the PSO (53.21% savings), Cruise time was reduced by 3704.15 s (54.64% superior); IBFLPSO saved total 1,297,972 joules from PSO-2OPT (48.04% savings), cruise time was reduced by 3008.44 s (49.45% superior); IBFLPSO saved 463,062 (24.80% savings) joules compared to GA, Cruise time was reduced by 1068.01 s (25.78% superior); Compared to BFLPSO, IBFLPSO saved 395,642 joules (21.99% savings), Cruise time was reduced by 914.24 s (22.92%superior). In the average solution, IBFLPSO saved 1,440,177 joules and 3332.65 s in cruise time compared to PSO-2OPT, 1,776,046 joules and 4155.02 s compared to PSO, 374,981 joules and 857.62 s in cruise time compared to GA, and 298,444 joules and 683.76 s compared to BFLPSO. Finally, in terms of the running time of the optimal solution, PSO-2OPT increases by 6.07 s compared to PSO, IBFLPSO increases by 85.88 s compared to BFLPSO, IBFLPSO needs longer running time than the other four algorithms, but will get better iterative results. These data confirm the validity of the 2-opt algorithm. Finally, IBFLPSO outperforms the other four algorithms in both optimal and average solutions, showing superior optimization capabilities and stability.

Conclusions and future works

This paper aims to minimize the combined cruising time of UAVs while considering energy expenditures associated with steady level flight, acceleration, deceleration, turning, and climbing maneuvers, by proposing the MUAVPP-MEC model. In IBFLPSO proposed, BFLPSO was integrated with energy-constrained 2-opt and an efficient encoding and decoding strategy was developed. The model and algorithm were validated across three distinct case studies, confirming the stability and efficacy of the proposed methods. Compared to four other algorithms, IBFLPSO achieved superior optimal and average solutions. The optimal solution of IBFLPSO is 54.64%, 49.45%, 25.78%, and 22.92% superior to those of the traditional PSO algorithm, PSO-2OPT algorithm, GA, and BFLPSO, respectively. Future work will further explore factors such as UAV payload to optimize the model and develop new solution algorithms.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- V :

-

Set of all nodes,V = 0,1,...,n-1 ,node \(i,j\in V\)

- E :

-

Set of edges between nodes, \(E = \{(i,j)\mid i,j\in V\}\)

- SetC :

-

Collection point set, SetC = 1,..., n-1

- SetD :

-

Central point set, SetD = 0

- SetU :

-

UAV fleet, all of identical model

- M :

-

Mass of UAV (including battery)

- Q :

-

Maximum battery capacity of UAV

- K :

-

Number of available UAVs

- SConst :

-

Constant cruising speed

- PConst :

-

Power required during constant speed phase

- DAcc :

-

Distance needed to accelerate from 0 to SConst

- TAcc :

-

Time required to accelerate from 0 to SConst

- EAcc :

-

Energy consumed to accelerate from 0 to SConst

- DDec :

-

Distance needed to decelerate from SConst to 0

- TDec :

-

Time required to decelerate from SConst to 0

- EDec :

-

Energy consumed to decelerate from SConst to 0

- \(\mu\) :

-

Efficiency coefficient of UAV battery energy conversion to thrust

- G :

-

Gravitational acceleration

- n :

-

Number of nodes

- \(c_{ij}\) :

-

Distance from node i to node j

- \(\theta _{ijl}\) :

-

The angle of UAV when it turns from the path from point i to point j to the path from point j to point l

- \(h_{i}\) :

-

Altitude of node i

- \(x_{ijk}\) :

-

The UAV k flies from node i to node j, \(x_{ijk}\) = 1;otherwise, \(x_{ijk}\) = 0

- \(y_{ik}\) :

-

The UAV k services node i, \(y_{ik}\) = 1;otherwise, \(y_{ik}\) = 0

References

Li, C. & Sun, X. A novel meteorological sensor data acquisition approach based on unmanned aerial vehicle. Int. J. Sens. Netw. 28, 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSNET.2018.096226 (2018).

Langaker, H.-A. et al. An autonomous drone-based system for inspection of electrical substations. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 18, 73. https://doi.org/10.1177/17298814211002973 (2021).

Wen, X. & Wu, G. Heterogeneous multi-drone routing problem for parcel delivery. Transp. Res. C Emerg. Technol. 141, 63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2022.103763 (2022).

Bahabry, A. et al. Low-altitude navigation for multi-rotor drones in urban areas. IEEE Access 7, 87716–87731. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2925531 (2019).

Lin, Y., Wang, T. & Wang, S. Trajectory planning for multi-UAV assisted wireless networks in post-disaster scenario. In 2019 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM). https://doi.org/10.1109/globecom38437.2019.9014091 (IEEE, 2019).

Zhen, L., Li, M., Laporte, G. & Wang, W. A vehicle routing problem arising in unmanned aerial monitoring. Comput. Oper. Res. 105, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2019.01.001 (2019).

Mignardi, S., Buratti, C., Cacchiani, V. & Verdone, R. Path optimization for unmanned aerial base stations with limited radio resources. In 2018 IEEE 29th Annual International Symposium on Personal, Indoor and Mobile Radio Communications (PIMRC) 328–332 (IEEE, 2018).

Xie, J., Carrillo, L. & Jin, L. Path planning for UAV to cover multiple separated convex polygonal regions. IEEE Access 8, 51770–51785. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2980203 (2020).

Alemayehu, T. S., Kim, J.-H. & Yoon, W. Fault-tolerant UAV data acquisition schemes. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 114, 1669–1685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-020-07445-5 (2020).

Ren, X., Froger, A., Jabali, O. & Liang, G. A competitive heuristic algorithm for vehicle routing problems with drones. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 318, 469–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2024.05.031 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. UAV network path planning and optimization using a vehicle routing model. Remote Sens. 15, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15092227 (2023).

Jiang, H., Wu, T., Ren, X. & Gou, L. Optimisation of multi-type logistics UAV scheduling under high demand. PROMET-Traffic Transp. 36, 115–131. https://doi.org/10.7307/ptt.v36i1.261 (2024).

Stodola, P. Unmanned surveillance problem: Mathematical formulation, solution algorithms, and experiments. Mil. Oper. Res. 25, 31–47. https://doi.org/10.5711/1082598325231 (2020).

Kyriakakis, N. A., Aronis, S., Marinaki, M. & Marinakis, Y. A GRASP/VND algorithm for the energy minimizing drone routing problem with pickups and deliveries. Comput. Ind. Eng. 182, 40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2023.109340 (2023).

Lee, M.-T., Lai, Y.-C., Chuang, M.-L. & Chen, B.-Y. Design and validation of a route planner for logistic UAV swarm. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 28, 227–240. https://doi.org/10.32604/iasc.2021.015339 (2021).

Huang, X. & Wang, G. Saving energy and high-efficient inspection to offshore wind farm by the comprehensive-assisted drone. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 170. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/6209170 (2024).

Dong, F., Wu, M., Zhu, W. & Li, X. Energy-efficient flight planning for UAV in IoT environment. J. S. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 50, 150–157 (2020).

Zhu, M., Zhang, X., Luo, H., Wang, G. & Zhang, B. Optimization Dubins path of multiple UAVs for post-earthquake rapid-assessment. Appl. Sci. 10, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10041388 (2020).

Huang, X. & Wang, G. Total energy cost optimization for data collection with boat-assisted drone: A study on large-scale marine sensor. IEEE Access 11, 134473–134484. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3335932 (2023).

Huang, X. & Wang, G. Optimization for total energy consumption of drone inspection based on distance-constrained capacitated vehicle routing problem: A study in wind farm. Expert Syst. Appl. 255, 80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124880 (2024).

Shen, H., Zhu, Y., Liu, T. & Jin, L. Particle swarm optimization in solving vehicle routing problem. In ICICTA: 2009 Second International Conference on Intelligent Computation Technology and Automation, Vol I, Proceedings 287–291. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICICTA.2009.77 (IEEE, 2009).

Wang, S., Wang, L. & Wang, D. Particle swarm optimization for multi-depots single vehicle routing problem. In 2008 Chinese Control and Decision Conference, Vols 1–11 4659. https://doi.org/10.1109/CCDC.2008.4598213 (2008).

Reong, S., Wee, H.-M. & Hsiao, Y.-L. 20 years of particle swarm optimization strategies for the vehicle routing problem: A bibliometric analysis. Mathematics 10, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10193669 (2022).

Chen, X., Tianfield, H. & Du, W. Bee-foraging learning particle swarm optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 102, 34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107134 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. A novel state transition simulated annealing algorithm for the multiple traveling salesmen problem. J. Supercomput. 77, 11827–11852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-021-03744-1 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. A novel hybrid swarm intelligence algorithm for solving TSP and desired-path-based online obstacle avoidance strategy for AUV. Robot. Auton. Syst. 177, 78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.robot.2024.104678 (2024).

Ahmed, S., Mohamed, A., Harras, K., Kholief, M. & Mesbah, S. Energy efficient path planning techniques for UAV-based systems with space discretization. In 2016 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/WCNC.2016.7565126 (2016).

Zeng, Y. & Zhang, R. Energy-efficient UAV communication with trajectory optimization. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 16, 3747–3760. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2017.2688328 (2017).

Zorbas, D., Razafindralambo, T., Luigi, D. P. P. & Guerriero, F. Energy efficient mobile target tracking using flying drones. Procedia Comput. Sci. 19, 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2013.06.016 (2013).

Meskar, M. & Ahmadi-Javid, A. Optimizing drone delivery paths from shared bases: A location-routing problem with realistic energy constraints. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 110, 142 (2024).

Jimenez, P., Lichota, P., Agudelo, D. & Rogowski, K. Experimental validation of total energy control system for UAVs. Energies 13, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13010014 (2020).

Li, H., Zhan, Z. & Wang, Z. Energy-consumption model for rotary-wing drones. J. Field Robot. 41, 1940–1959 (2024).

De, A., Wang, J. & Tiwari, M. K. Hybridizing basic variable neighborhood search with particle swarm optimization for solving sustainable ship routing and bunker management problem. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 21, 986–997. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2019.2900490 (2020).

Parouha, R. P. & Verma, P. R. State-of-the-art reviews of meta-heuristic algorithms with their novel proposal for unconstrained optimization and applications. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 28, 4049–4115 (2021).

Larrañaga, P., Kuijpers, C., Murga, R., Inza, I. & Dizdarevic, S. Genetic algorithms for the travelling salesman problem: A review of representations and operators. Artif. Intell. Rev. 13, 129–170. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006529012972 (1999).

Oudouar, F. & El Fellahi, A. Solving the location-routing problems using clustering method. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Big Data, Cloud and Applications, BDCA’17. https://doi.org/10.1145/3090354.3090472 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2017).

Augerat, P. Approche polyèdrale du problème de tournées de véhicules. Ph.D. thesis, Institut National Polytechnique de Grenoble-INPG (1995).

Zorbas, D., Razafindralambo, T., Luigi, D. P. P. & Guerriero, F. Energy efficient mobile target tracking using flying drones. In 4th International Conference on Ambient Systems, Networks and Technologies (ANT 2013), The 3rd International Conference on Sustainable Energy Information Technology (SEIT-2013), Vol. 19 of Procedia Computer Science (ed Shakshuki, E.) 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2013.06.016 (2013).

Figliozzi, M. A. Lifecycle modeling and assessment of unmanned aerial vehicles (Drones) CO2e emissions. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 57, 251–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2017.09.011 (2017).

Funding

This work is partially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province under No. 2024A1515012283 and No. 2022A1515010178; Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation under grant No. 2022A1515240058 and No. 2024A1515010222; the Key Project in Higher Education of Guangdong Province, China under No. 2022ZDZX1045, No. 2022ZDZX4049, No. 2023ZDZX3069, No. 2023ZDZX1040 and No.2024ZDZX1046; the Social Public Welfare and Basic Research Project of Zhongshan City under grant No. 2021B2063 and the research project of Jiaying University under No. 2022RC127.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Q., H.J., G.H. and F.W. wrote the original draft preparation and Y.Q., G.H., L.Y. and Y.X. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, Y., Jiang, H., Huang, G. et al. Multi-UAV path planning considering multiple energy consumptions via an improved bee foraging learning particle swarm optimization algorithm. Sci Rep 15, 14755 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99001-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99001-z