Abstract

In the face of escalating global energy crises and pressing challenges of environmental pollution, the imperative for sustainable energy solutions has never been more pronounced. Photovoltaic (PV) power generation is recognized as a cornerstone in transition towards a clean energy paradigm. This study introduces a groundbreaking short-term PV power forecasting methodology based on teacher forcing (TF) integrated with bi-directional gated recurrent unit (BiGRU). Firstly, the chaotic feature extraction is synergistically employed in conjunction with the C-C method to meticulously discern the pivotal factors that shape the dynamics of PV power, complemented by the inclusion for solar radiation data as an additional element. Besides, a potent fusion of gradient boosting decision trees (GBDT) and BiGRU is leveraged to adeptly process time series data. Moreover, teacher forcing is seamlessly integrated into the model to bolster forecasting accuracy and stability. Experimental validations demonstrate the remarkable performance of the proposed method under complex and diverse weather conditions, offering a pioneering technical approach and theoretical framework for PV power forecasting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The escalating global energy crisis, coupled with the deteriorating environmental pollution, has underscored the imperative for sustainable and eco-friendly energy alternatives1,2. Photovoltaic (PV) power generation, lauded for its efficiency and environmental benignity, is experiencing rapid growth, and is poised to become a cornerstone in the evolution of the global energy landscape3,4. A distinctive feature of PV power generation lies in the pronounced volatility and unpredictability, which poses significant challenges to safety, stability, and economic viability, especially in the context of large-scale integration5. Effective forecasting of PV power fluctuations is crucial for optimizing grid operation and management, as well as enhancing the integration of renewable energy sources, ultimately fostering more cost-effective and efficient power system operation6.

Recent progress in the field of photovoltaic (PV) power forecasting has been delineated into two principal methodologies: the physical and the statistical7. The physical methodology predominantly harnesses solar radiation and meteorological data in the vicinity of the PV installation. Moreover, PV power output forecasting is concentrated by utilizing solar irradiance data8,9. However, these studies tend to focus predominantly on solar irradiance, often neglecting a comprehensive examination of the interplay between other meteorological factors and PV performance. To bolster the precision of forecasting and mitigate reliance on specific weather metrics, an array of meteorological parameters is amalgamated, including wind velocity, wind direction, and ambient temperature10. Besides, the impact of cloud cover on solar irradiance levels is delved11. The employment of satellite technology for the procurement of meteorological data provides a more encompassing meteorological profile compared to relying on local weather station data alone. Nonetheless, the sheer quantity of data, coupled with the intricate interdependencies between diverse meteorological phenomena and PV output, escalates the computational demands. Statistical approaches, encompassing models such as Markov chains, Bayesian statistics, and ARIMA, leverage historical data to project future PV power generation. Despite their utility, these statistical techniques encounter challenges when confronted with the intricacies of fluctuating weather patterns.

Furthermore, the burgeoning advancements in machine learning have profoundly influenced the domain of photovoltaic (PV) power forecasting, with machine learning-based models exhibiting substantial promise. Prominent examples encompass support vector machines12,13,14, long short-term memory (LSTM) networks15,16,17,18, K-nearest neighbors (KNN)12,19,20, and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost)21,22. These sophisticated models have demonstrated an impressive capacity to manage extensive datasets and discern complex patterns. They are endowed with the ability to glean insights from historical data, thereby enabling the anticipation of future PV power outputs. Despite the prowess, these models encounter challenges, particularly when dealing with smaller datasets, where the performance may not be as robust. A pivotal concern, especially amidst the dynamic and fluctuating nature of weather conditions, is the imperative to refine the robustness and accuracy of forecasting models. Thus, it is of great significant for enhancing the forecasting reliability and efficacy under a spectrum of environmental scenarios.

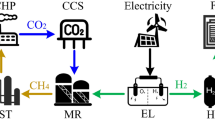

Considering the preceding researches, a pioneering approach to the short-term forecasting of photovoltaic power is designated as the CC-TF-BiGRU forecasting strategy. The methodological framework commences with the identification of pivotal factors influencing PV power generation, achieved through the synergy of chaotic feature extraction and the C-C method (CC), utilizing a modified C-C method for phase space reconstruction to determine parameters, thereby enhancing the fidelity of the phase space reconstruction, with the inclusion of solar radiation data as a critical additional variable. This is followed by the application of an integrated model to process time series data, consisting of gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT) and bi-directional gated recurrent unit (BiGRU). The ingenuity of the developed method is manifested in fusion of adeptness for GBDT in processing structured data with the robust handling of time series by BiGRU, ensuring a holistic examination of the temporal dynamics inherent in PV power generation. A novel integration method is introduced, incorporating GBDT-extracted features into the BiGRU model through a teacher forcing mechanism. Specifically, the GBDT outputs are weighted and combined with the previous hidden layer data within the BiGRU before being fed into the next hidden layer. The convergence speed of the BiGRU model is accelerated significantly by the innovative approach while enhancing its forecasting accuracy. Experimental validations demonstrate exceptional performance in short-term PV power forecasting, even under the duress of complex and mutable weather conditions, maintaining high predictive accuracy and contributing a novel technical and theoretical framework for PV power forecasting.

The structure is delineated as follows: Sect. 2 delves into the determinants affecting photovoltaic power generation and executes the extraction of pertinent features. Section 3 introduces the teacher forcing-enhanced bi-directional gated recurrent unit (TF-BiGRU) model, elucidating its theoretical underpinnings and architectural components. In Sect. 4, a case study is applied, which is complemented by an in-depth analysis and comprehensive discussion of the experimental outcomes. Finally, the findings are encapsulated, the implications of the study are underscored, and avenues for subsequent research endeavors are proposed in Sect. 5.

Multifactorial information mining and chaotic feature extraction

Information mining of multiple influencing factors

The generation of photovoltaic power is significantly influenced by a multitude of external factors23. Within the framework of solar energy’s transformation from radiant light energy to electrical power, the pivotal factors that shape the conversion process are illustrated in Fig. 1. As depicted in Fig. 1, the variability and instability of photovoltaic power output are subject to a multitude of external influences. These influences can be categorized into two primary groups: non-meteorological factors and meteorological factors. Each of these categories has the potential to exert either direct or indirect impacts on the efficiency and stability of PV power generation.

Non-weather factors: These factors are predominantly related to the intrinsic properties of the photovoltaic module. Besides, the efficiency of the inverter, the conversion efficiency of the array, and the tilt angle of the PV panels are encompassed. Collectively, the elements significantly shape the photovoltaic conversion efficiency within PV power plants. Nevertheless, due to the diversity and complexity, quantifying the factors into precise numerical values are often challenging, which can complicate the integration of the variables into accurate PV power forecasting models.

In addition, weather factors, in contrast to non-meteorological influences, exert a more immediate and pronounced effect on PV power generation. The category encompasses a spectrum of variables, including but not limited to, wind speed and direction, humidity, ambient temperature, and solar radiation. To mitigate the impact of the weather-related factors on PV power output, the Pearson correlation coefficient (R) is obtained and scrutinized based on principal weather factors and PV power. Data from various seasons and a range of weather conditions are considered to ensure that the experimental outcomes are both representative and precise. The methodology for computing R is delineated in Eq. (1).

The outcomes pertaining to the R across various seasons and under diverse weather conditions are presented in Table 1. As evidenced by Table 1, during the spring and summer months, photovoltaic power exhibits a robust correlation with solar radiation and temperature, while demonstrating a more tenuous association with humidity, barometric pressure, and wind speed. In autumn, PV power output is still markedly affected by variations in solar radiation and temperature, with humidity and wind speed exerting a minor influence, and barometric pressure having a negligible effect. Conversely, in the winter season, solar radiation and temperature continue to be pivotal factors influencing PV power, whereas barometric pressure, humidity, and wind speed have a markedly diminished impact.

To delve deeper into the interplay between each influencing factor and PV generation, an analysis is conducted across weather conditions: sunny, rainy, and cloudy days, which are graphically represented in Fig. 2. As depicted in Fig. 2, irrespective of the weather type, solar radiation exhibits a pronounced transient nature, which predominantly mirrors the short-term trends in photovoltaic power generation. In contrast, temperature and humidity exhibit more gradual changes, characterized by inertial properties that do not readily capture the instantaneous fluctuations in power output. Nonetheless, these factors indirectly influence the performance and efficiency of PV cells.

Drawing from the analysis, a selection of five climatic factors is chosen as input features for the spring and summer seasons: wind speed, humidity, temperature, and solar radiation. For the autumn season, a more refined selection is made, comprising solar radiation, temperature, and humidity. In the winter, the input features are narrowed down to solar radiation and temperature alone. PV data are inherently characterized by chaos, evidenced by high autocorrelation and intricate dynamic fluctuations24. Consequently, the extraction of chaotic features is paramount for comprehending and forecasting short-term deviations in PV power. To circumvent the complexities associated with directly analyzing the influencing factors, a focal emphasis on solar radiation as the primary transient indicator is placed. By leveraging chaotic feature extraction techniques on PV power data, solar radiation is introduced as an additional input variable. Thus, the developed integration with the objective of enhancing the precision of the forecasting model is strategic.

C-C method-based chaotic feature extraction

In the process of phase space reconstruction for photovoltaic power, the appropriate selection of embedding dimension and delay time is crucial for the accuracy of attractor reconstruction. The key parameters directly influence the fidelity of the phase space reconstruction, thereby determining the precision of subsequent forecasting. The C-C method is widely recognized and employed for the determination of phase space reconstruction parameters, largely due to its robustness against noise and its minimal computational requirements25. The conventional C-C method has three main drawbacks when applied to photovoltaic power data: (1) interference from high-frequency fluctuations, (2) zero-crossing misjudgment in determining the optimal time delay, and (3) unstable embedding-window estimation26.

To overcome these issues, the C-C approach based on the characteristics of PV data is optimized as follows:

-

(1)

Improving the calculation of key statistics by introducing new metrics, \({S_1}\left( t \right)\) and \({S_2}\left( t \right)\), which mitigate the impact of high-frequency fluctuations. The specific formulas for \({S_1}\left( t \right)\) and

$${S_1}(m,N,r,\tau )=C(m,N,r,\tau ) - {C^m}(1,N,r,\tau )$$(2)$${S_2}(m,r,\tau )=\frac{1}{\tau }\sum\limits_{{s=1}}^{\tau } {\left[ {C(m,r,\tau ) - C_{s}^{m}(m,r,\tau )} \right]}$$(3)where m is the embedding dimension, \(\tau\) is delay time, N represents the total number of data points; in the reconstructed phase space, r is the defined spatial distance.

-

(2)

New decision rule: The first local minimum of \({S_1}\left( t \right)\) is used as the optimal time delay \({\tau _d}\).

-

(3)

Embedding window estimation optimization: The reliability of embedding window selection is enhanced through periodic point analysis.

After determining the embedding dimension and penalty factor, the chaotic quotient trajectories, which contain information on each influencing factor, are recovered as presented in Eq. (4).

Photovoltaic power forecasting based on TF-GBDT-BiGRU

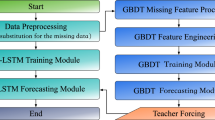

A primary challenge in photovoltaic power forecasting lies in the precise processing and analysis of extensive time series data, which frequently exhibit intricate patterns influenced by a multitude of factors, including weather conditions and seasonal variations. Thus, a novel forecasting model with TF-GBDT-BiGRU is introduced to address this challenge. The detailed forecasting process of the proposed CC-TF-BiGRU model is displayed in Fig. 3.

The TF-GBDT-BiGRU model is developed for forecasting on the synergistic integration of the strengths of GBDT and BiGRU. GBDT is renowned for its proficiency in processing structured data, efficiently discerning complex patterns and capturing nonlinear relationships with remarkable accuracy. Simultaneously, BiGRU, as a sophisticated variant of recurrent neural networks (RNN), demonstrates an exceptional ability to capture long-term dependencies and dynamic features inherent in time series data. During the BiGRU training process, the features extracted by GBDT are integrated through a teacher forcing (TF) mechanism. Specifically, during the BiGRU training phase, the forecasting results derived from GBDT are dynamically weighted and fused with the network outputs from the previous time step. The combined features are then fed into the hidden layer of next time step, enabling the model to effectively integrate structured data insights from GBDT with temporal dependencies captured by BiGRU. Such a strategy not only accelerates the learning process but also mitigates the accumulation of error, thereby enhancing the overall forecasting accuracy.

GBDT model construction

Gradient boosting decision trees (GBDT) are esteemed within the machine learning community for the efficacy in both regression and classification tasks, particularly within the domain of supervised learning27,28,29. A visual representation of the GBDT model is presented in Fig. 4. A robust forecasting model is constructed through the aggregation of multiple decision trees, leveraging several key features and advantages:

-

(1)

Iterative learning: GBDT progressively refines model performance by incrementally adding decision trees to the ensemble.

-

(2)

Gradient descent optimization: With each iteration, GBDT employs a gradient descent algorithm to meticulously minimize the loss function. It ensures that each subsequent tree is crafted to specifically target and reduce the aggregate forecasting error.

-

(3)

Overfitting mitigation: By meticulously tuning parameters such as the number and depth of trees, as well as the learning rate, GBDT adeptly circumvents the pitfalls of overfitting. The nuanced approach allows it to maintain robust performance across a diverse array of datasets.

Within the TF-BiGRU framework, GBDT plays a pivotal role in the initial phase of processing and analyzing structured data. It is essential for identifying key features and discerning underlying patterns, thereby laying a solid foundation for subsequent time series forecasting endeavors. Specifically, the GBDT model inputs temperature, pressure, humidity, solar irradiance, and the power generation from the previous time step. These features are processed by GBDT to extract critical features and identify underlying patterns that influence PV power variations. The optimization objective of the GBDT model is to predict the PV power at the next time step. During the training phase, GBDT builds a series of decision trees where each tree learns the relationships between input features and the PV power by minimizing the residual errors of previous predictions. In each decision tree, the model learns which features contribute the most to reducing prediction error and adjusts their weights accordingly. The output of the trees is combined to generate an optimal prediction for the PV power at the next time step. The output of GBDT is then weighted and integrated with the output from the previous hidden layer of BiGRU, and the combined result is fed into the subsequent hidden layer. The integration of GBDT with BiGRU significantly enhances its forecasting accuracy, particularly in handling fluctuations in PV power. The improvement is attributable to the synergy between proficiency in structured data analysis of GBDT and adeptness in time series analysis of BiGRU. Furthermore, GBDT has been extensively applied in the domain of emulating numerical weather prediction (NWP) models, utilizing a wealth of meteorological data. However, it is important to note that GBDT may encounter limitations when it comes to capturing the intricacies of time-dependent phenomena, such as the evolution of weather patterns, from sequential data.

BiGRU structure determination

The Bi-directional gated recurrent unit (BiGRU) represents a sophisticated architecture within the realm of RNN, meticulously engineered for the purpose of processing and analyzing time series data30,31. It harnesses the strengths of the gated recurrent unit (GRU) and further enhances the analytical prowess of time series data through its innovative bidirectional processing paradigm. The BiGRU architecture is characterized by the presence of two distinct yet complementary GRU layers: one adeptly processes the time series data in a forward chronological sequence, from past observations to future projections, while its counterpart adeptly navigates the data in the reverse direction, from future projections back to past observations. The dual-directional processing mechanism endows the BiGRU with the unique capability of conducting a comprehensive time series analysis. The intricate structural design of the BiGRU, which underpins its analytical capabilities, is graphically depicted in Fig. 5.

The application of BiGRU plays a vital role in forecasting PV power31. BiGRU is adept at processing and analyzing time series characteristics in PV power generation data, such as sunlight intensity and temperature variations, which are pivotal in affecting the PV power generation efficiency. The computational formula for the original GRU hidden layer unit is detailed in Eq. (5).

Here, \({x_t}\) is the input at t ; tanh is a hyperbolic tangent function; \(\sigma\) is a Sigmoid function; \({w_u}\), \({w_r}\), \({w_h}\), \({w_x}\) are parameter matrices; \({z_t}\) and \({r_t}\) are update and reset gates, respectively.

TF-BiGRU-based integrated forecasting model

The TF-BiGRU model represents an innovative convergence of two formidable machine learning techniques: gradient boosting decision trees (GBDT) integrated with bi-directional gated recurrent units (BiGRU). Moreover, the strategic integration is forecasted on the understanding that a nuanced synthesis of structured data analysis and time series data interpretation is required by the accurate PV power forecasting. GBDT has proven its mettle in managing intricate structured data, identifying and extracting adeptly pivotal features. In contrast, BiGRU excels in handling time series data, showcasing acumen in discerning and comprehending long-term dependencies inherent within such datasets.

During the training phase of the TF-BiGRU model, the incorporation of the teacher forcing (TF) mechanism stands as a pivotal element. The crux of the mechanism is the utilization of actual output data as input for the subsequent step in the training process, rather than relying exclusively on the forecasting. Besides, the approach significantly bolsters the learning efficiency of the model during the initial training phase and is instrumental in mitigating the accumulation of errors throughout the training regimen. A flowchart delineating the proposed TF-BiGRU model is presented in Fig. 6.

Unlike the original BiGRU, the proposed forecasting model incorporates the GBDT forecasting results and the weighted output from the previous stage as its input. The specific formulas for the input at the final forecasting stage and the GRU hidden layer units are shown in Eqs. (6), (7), respectively.

where \({y_{t - 1}}\) represents the output result of the previous hidden layer; \({g_{t - 1}}\) represents the forecasting result of the GBDT model; \(\alpha\) represents the weight, which is subsequently optimized by the Adam optimizer.

The computational steps encapsulated within the TF-BiGRU model are as follows:

-

(1)

Input feature data: Weather characteristics and light radiation intensity extracted by the C-C method are used as input features. The features of PV panel temperature, pressure, humidity, irradiance, and power generation information for each time point are integrated into a matrix X.

-

(2)

Tree splits and feature transformation: For processing by the GBDT model, the data is refined to render it suitable.

-

(3)

GBDT model forecasting: The transformed features are fed into the GBDT model to prognosticate PV output power, thereby producing a PV sequence data \(G\left( x \right)\).

-

(4)

BiGRU model forecasting with TF: The sequence data \(G\left( x \right)\) is then funneled into section \({X_t}\) of the BiGRU model through TF, where it is processed through the T4-T9 neural units, being leveraging both the backward and forward hidden layers for comprehensive analysis.

-

(5)

Output fusion: The culminated forecasting from the hybrid model is consolidated and presented at the output layer \({y_t}\).

To optimize model parameters and accelerate the training process, the TF-BiGRU prediction model utilizes the Adam optimizer, enabling faster convergence without compromising prediction accuracy32,33. The mathematical formulation of the Adam optimizer is articulated in Eq. (8).

where \(\varepsilon\) is a very small number preventing the denominator from being equal to 0; \(\alpha\) is the learning rate; \({m_{hat}}\) is the gradient mean; \({v_{hat}}\) is the gradient variance value; \(\theta\) is the updated value of the model parameters.

The TF-BiGRU model emerges as a formidable and versatile tool, adeptly addressing the complexities inherent in PV power forecasting. Moreover, the efficacy is derived from the innovative fusion of GBDT and BiGRU, further augmented by the strategic incorporation of the teacher forcing mechanism. The developed model not only demonstrates remarkable proficiency in the accurate forecasting of power output but also distinguishes itself through its ability to adapt to a myriad of environmental fluctuations. Such adaptability is instrumental in bolstering the efficiency and effectiveness of PV power system management.

Case study

Performance evaluation metrics

To ascertain the validity of the model, three accuracy estimators were employed for objective evaluation: mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and coefficient of determination (\({R^2}\)). The evaluation metrics are shown in Eqs. (9) – (11):

wherey is true value; \(\hat {y}\) is forecasted value; \(\bar {y}\) is mean value.

Forecasting results and analysis of case 1

For calculation and simulation analysis, PV data and corresponding meteorological information from the Xinjiang PV power system are leveraged in this study, collected from 2021 to 2022. The data collection is meticulously scheduled from 4:00 to 20:00 h daily, employing a sampling resolution of 15 min, which yielded a daily aggregate of 64 data points. To rigorously assess the efficacy of the proposed forecasting methodology and to ensure the robustness of the time-series forecasting, the training set is constructed strictly in time sequence using data from 2021 to 2022, which include all weather conditions. The objective of the comparative analysis includes: firstly, the present forecasting model is validated in this study, and secondly, the PV power forecasting accuracy under a diverse array of weather conditions is appraised.

Feature selection parameterization

For PV power forecasting, the judicious selection of feature extraction parameters is of paramount importance. The complexity of factors influencing PV power generation is multifaceted, spanning a wide array of considerations including the geographical orientation of the power plant, the tilt angle of the solar panels, and the array conversion efficiency. Moreover, given the impracticality and redundancy of accounting for every conceivable factor in the forecasting process, the C-C method is adeptly utilized to distill and extract features. Thus, the targeted approach ensures a focused and pertinent analysis of the most influential parameters.

Furthermore, the determination of an embedding dimension m and appropriate delay time \(\tau\) is crucial within the phase space reconstruction process. The C-C method is also strategically employed for ascertaining the parameters pertinent to the reconstruction of chaotic phase space. The statistical analyses are graphically represented in Fig. 7.

As seen in Fig. 6, the first local minima of the \(\Delta {S_1}(\tau )\) occurs at moment \(x=26\). The period of \(\left| {{S_1}\left( \tau \right) - {S_2}\left( \tau \right)} \right|\) is 168. Thus, the study sample delay time is 26, the average trajectory period is optimally estimated to be 168, and by \(m=INT(l/\tau )+1\) the embedding dimension is 7.

Comparative of feature extraction

An extensive comparative analysis is conducted to evaluate the efficacy of the proposed feature extraction methodology, with a particular emphasis on the incorporation of solar radiation as a pivotal feature input. The experimental framework is structured around data extracted from the final day of the first quarter in 2022 and encompassed a series of 30 independent simulations. Meanwhile, the simulations are performed using three distinct methodologies: NWP-TF-BiGRU, Chaos-TF-BiGRU, and the CC-TF-BiGRU approach as delineated in this study. A comprehensive error analysis, which scrutinizes the forecasting outcomes yielded by the various feature extraction techniques, is articulated in detail within Table 2. Furthermore, Fig. 8 presents a visual comparison of the forecasted power outputs for PV power generation, as derived from these diverse feature extraction methods.

Upon a meticulous analysis of Fig. 7 and the data presented in Table 2, it becomes evident that the CC-TF-BiGRU method, as articulated in this study, achieves superior performance for PV power forecasting when juxtaposed with the traditional NWP-TF-BiGRU and Chaos-TF-BiGRU approaches. The NWP-TF-BiGRU method falls short in its capacity to fully encompass the myriad factors that impinge upon PV power generation, while the Chaos-TF-BiGRU method grapples with the challenge of accurately tracking the dynamics of the system due to the phase space delay effect. In stark contrast, the CC-TF-BiGRU method takes a more holistic approach by meticulously considering the spectrum of factors that influence PV power. It effectively mitigates forecasting error by integrating solar radiation as an additional input variable, thereby enhancing the forecasting accuracy of the model. Moreover, the proposed method is characterized by a relatively narrow range of error fluctuation, which underscores its robustness and reliability for PV power forecasting.

Forecasting results and error analysis

A comprehensive evaluation is conducted to substantiate the utility and efficacy of the present model. It involves the construction and rigorous testing of 9 comparative models across a spectrum of 13 distinct test scenarios. The scenarios encompassed three diverse weather conditions prevalent across the four seasons over two years, with additional tests conducted under the unique challenges presented by sandstorm weather conditions. Consistency in the evaluation process is ensured by utilizing the identical training and forecasting datasets for each model, under the same specified weather conditions. The specific parameter configurations for each model, tailored to optimize performance under these varied conditions, are elaborated upon in Table 3.

Sunny day

The forecasting performance of each model under sunny conditions across different seasons is illustrated in Fig. 9. A key observation from Fig. 9 is that model #10 consistently achieves the highest forecasting accuracy on sunny days. The comparative analysis of forecasting errors under sunny conditions, as shown in Fig. 10; Table 4, further reinforces this observation.

Model #10 demonstrates significantly improved forecasting accuracy throughout the annual cycle, maintaining consistently high performance. This can be attributed to its effective integration of strategic feature selection and advanced data extraction techniques, which enhance generalization capability while mitigating the risk of overfitting. Specifically, compared to single neural network models (#1–#8), model #10 achieves lower mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE), along with a higher coefficient of determination (R²). Similarly, when compared to the hybrid model #9, model #10 demonstrates superior experimental results, further emphasizing the advantages of the connection method proposed in this study. These findings demonstrate that the proposed model not only achieves superior performance under sunny conditions but also ensures reliable forecasting accuracy across different seasons.

Cloudy day

The comparison of PV power forecasting across different season under cloudy days is illustrated in Fig. 11. In addition, under cloudy weather conditions, the comparison of forecasting errors is demonstrated in Fig. 12; Table 5. Under cloudy weather conditions, significant fluctuations in solar irradiance lead to rapidly changing photovoltaic (PV) power data. These fluctuations place higher demands on the adaptability and accuracy of forecasting models. Therefore, a comparative experiment is conducted during a cloudy autumn noon. Between 11:00 AM and 1:00 PM, the actual power exhibited noticeable fluctuations. Model #1 and model #2 are almost unable to effectively fit the rapidly changing PV power trends, especially during the power decline phase, where the forecasting results remained nearly flat, resulting in substantial prediction errors. Although model #6 and model #8 demonstrate a strong ability to capture the dynamic fluctuations in PV power, accurately reflecting rapid transient changes, short-term dips, and surges. However, they still fall short in overall forecasting accuracy. Novel time series models, including model #3, model #4, and model #5, demonstrate improved forecasting accuracy and excel at capturing contextual relationships within data. However, these models still exhibited a certain degree of lag when dealing with power fluctuations caused by rapid changes in solar irradiance. In contrast, the proposed CC-TF-BiGRU model incorporates a teacher forcing (TF) mechanism to weight and integrate the features extracted by GBDT with the output from previous hidden layer of BiGRU. Specifically, the GBDT model takes inputs comprising temperature, pressure, humidity, solar irradiance, and the power generation from the previous time step. The data are processed by GBDT for feature extraction and preliminary analysis, identifying key factors and underlying patterns that influence PV power variations. By using the TF mechanism, the power data output by GBDT effectively guides the BiGRU model, ensuring fast convergence during training and maintaining high accuracy during forecasting. The method fully utilizes strengths in handling structured data of GBDT to extract critical features and patterns, while BiGRU effectively models the temporal dependencies in the data. As a result, the CC-TF-BiGRU model not only swiftly tracks actual power fluctuations but also delivers highly accurate forecasting results, significantly outperforming the other comparison models.

Under four seasons of cloudy weather conditions, analysis of Fig. 12; Table 5 show the highest forecasting accuracy for the developed model. Moreover, the average MAE is reduced by at least 51.34% compared to single neural network models #1-#8. The average RMSE is at least 54.68% lower and the average R2 is at least 8.65% higher. Average MAE is 33.97% lower compared to hybrid model #9. The RMSE average is improved by 37.05% and the average R2 is reduced by 3.79%. The experiments verify that the proposed forecasting model has the best forecasting effect under cloudy weather conditions across different seasons.

Rainy day

Additionally, under rainy conditions characterized by significant weather fluctuations, ablation experiments are conducted to further validate the applicability of the model. To ensure reliability and validity, each experiment maintains consistent operating environments and data sets. Initially, the model #7 is employed independently for forecasting. The results reveal that model #7 fails to effectively capture the rapid slight decline in power at 11:00 AM, as it continued to follow the preceding upward trend, leading to substantial discrepancies between the forecasted and actual power values. Subsequently, the model #8 is utilized alone for forecasting. Although model #8 successfully identifying and capturing the declining power features, it significantly overestimates the peak power, resulting in considerable errors between the forecasted and actual values. Model #9 has somewhat enhanced the ability to capture power variation patterns. However, the forecasting accuracy remained insufficient, and the model did not fully align with the actual power variations. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed CC-TF-BiGRU model accurately fits the actual power variation trends. It successfully captures the slight decline and rapid rebound in power at 11:00 AM, with forecasting results closely aligning with the actual measurements. The performance is markedly superior to that of using GBDT or BiGRU models individually. The forecasting results of each model under rainy weather across different seasons are illustrated in Fig. 13. As shown in Fig. 13, the proposed model exhibits minimal error and demonstrates a strong ability to resist interference.

Moreover, under rainy weather conditions, the comparison of forecasting errors for further model verification is presented in Fig. 14; Table 6. Under highly fluctuating weather conditions, the analysis of Fig. 14; Table 6 illustrates that the proposed model maintains high forecasting accuracy. The forecasting errors remain low without overfitting, and the average MAE is reduced by at least 46.04% compared to single neural network models #1-#8. The average RMSE is reduced by at least 37.04%, and the average R² is increased by at least 8.55%. Compared to the hybrid model #9, the average MAE is 25.46% lower, the average RMSE is reduced by 25.46%, and the average R² is improved by 3.33%. The results demonstrate that the proposed forecasting model achieves the highest forecasting accuracy in all seasons, regardless of rainy weather.

Sandstorm weather

Sandstorm weather presents unique and significant challenges to photovoltaic (PV) power generation. During sandstorms, the concentration of suspended particulates in the air increases substantially. These particulates accumulate on the surface of PV panels, leading to a reduction in solar irradiance reaching the photovoltaic cells. Consequently, PV power output exhibits significant fluctuations and overall performance degradation. Power data collected during sandstorm events typically show rapid and unpredictable declines in PV power generation. Furthermore, sandstorms often occur simultaneously with other weather phenomena such as high wind speeds and drastic temperature changes. The interactions among these factors complicate the modeling process, posing substantial challenges to forecasting efforts.

The forecasting results under sandstorm weather conditions are illustrated in Fig. 15. As shown in the figure, model #10 demonstrates the lowest forecasting error and exhibits strong robustness against external interference. Compared to other models, the proposed model excels at capturing and accurately reflecting the rapid power fluctuations caused by sandstorm conditions. When significant power variations occur, model #10 closely follows the actual trends, ensuring that the predicted power trajectories align well with the real data.

Further comparison of forecasting errors, shown in Table 7, confirms that the proposed model significantly outperforms the other models across all metrics. These results highlight the superior adaptability and accuracy of the developed forecasting model under the challenging conditions of sandstorm weather, making it the most reliable approach for such scenarios.

Forecasting results and analysis of case 2

Currently, mainstream combined forecasting models often employ a sequential approach, where feature extraction and forecasting are treated as separate stages or embedded in deep learning architectures through specialized modules. However, the traditional approach has notable limitations. When features are transferred from extraction to forecasting, vital temporal relationships may be lost, particularly under complex weather conditions that make it difficult to capture dynamic interactions among key features, potentially skewing forecasting results. Furthermore, since the forecasting model relies solely on extracted features for optimization, it cannot fully leverage the multi-layered information of the original data during training. As a result, training times are prolonged, convergence is slowed, and overall performance is reduced.

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed forecasting method in enhancing model performance, simulations using dataset from a photovoltaic power generation system in the Sun Mountain is conducted, where rainy days are particularly frequent. The experimental data, collected between 2022 and 2024, include photovoltaic power output and related meteorological information. Data are gathered daily between 4:00 and 20:00 at 15-minute intervals, resulting in 64 data points per day. To ensure the preservation of temporal dependencies and to prevent information leakage, the dataset is partitioned based on time sequence. Specifically, to forecast PV power on a particular rainy day in 2024, all available historical data from 2022 to 2023 are exclusively used as the training set, while the data corresponding to that single rainy day in 2024 are reserved for testing. The dataset comprehensively captures the operational characteristics of the PV system as well as the dynamic shifts in weather conditions.

To highlight how feature extraction improves forecasting performance, the focus is placed on rainy days, as the model typically performs the worst under such conditions. Therefore, a rainy day in 2023 is selected as the target for forecasting. The proposed method demonstrates a clear comparison of how different feature extraction connection methods enhance forecasting accuracy. Four different models are used as benchmarks in the comparative study. Consistency in the evaluation process is ensured by utilizing the identical training and forecasting datasets for each model, under the same specified weather conditions. The specific parameter configurations for each model, tailored to optimize performance under these varied conditions, are elaborated upon in Table 8.

On rainy days, moving cloud cover, raindrops, and humidity alter the optical properties of photovoltaic panels, causing solar radiation fluctuations and leading to erratic PV power output. Figure 16 compares the performance of several models under rainy conditions. As shown, actual PV power data between 12:00 and 15:00 exhibits significant oscillations. Model #1, a popular approach in recent years, produces an almost straight line, failing to capture these variations. Model #2 supplements model #1 with a CNN feature-extraction module in a traditional serial manner, resulting in some recognition of power fluctuations, yet it overestimates values and shows delayed response due to model #1. Model #3 behaves similarly to model #1, overlooking fluctuations and overestimating power. Building on model #3, model #4 integrates CNN-based feature extraction, which partly mitigates the previous shortcomings but shows an abnormal result between 9:00 and 10:00, and still deviates from the real values during the oscillatory phase. Model #5 implements the connection method proposed here, dynamically feeding extracted features into model #3 during training via a teacher forcing mechanism. Consequently, its forecasting results align closely with actual data overall and effectively capture midday fluctuation patterns, demonstrating high consistency with observed PV power. In addition, forecasting performance comparison under rainy is present in Table 9. Three forecasting performance evaluation indexes, such as RMSE, MAE, R2, are used to evaluate the forecasting effect of different models. This strategy not only enhances adaptability to sudden changes but also reduces the lag and bias seen in traditional approaches, resulting in more stable and precise forecasting results.

Experimental results show that the proposed model excels across all metrics, particularly in forecasting under complex weather conditions. The method integrates features extracted by GBDT into the input of the BiGRU model during training through a teacher forcing mechanism. It allows the model to effectively capture key features under challenging weather conditions and prevent distortion in forecasting. Additionally, the developed approach accelerates convergence and improves generalization, providing a clear advantage over traditional connection methods.

To further validate the robustness and generalizability of the model, a cloudy day from 2024 is selected for forecasting using the same training set. Figure 17 compares the performance of several models under rainy conditions. As shown in the figure, between 14:00 and 16:00, the photovoltaic power significantly decreases due to cloud cover blocking sunlight. However, due to the cloud thickness, the actual photovoltaic power remains fluctuating. Models #1 and #3, which are mainstream time-series models, fail to effectively track the fluctuation trends during the midday and afternoon periods. On the other hand, models #2 and #4, which extract features before performing time-series forecasting, capture the volatility more accurately than single time-series models, but still exhibit some error. Based on the results shown in Fig. 17; Table 10, model #5 emerges as the optimal model in terms of tracking power fluctuations and forecasting errors. The results, consistent across different years and weather conditions, demonstrate that the model has strong robustness and generalizability.

To quantitatively evaluate the impact of each meteorological feature on the PV power forecasting, SHAP (Shapley additive explanations) values is used for analysis. SHAP is a model-agnostic method derived from cooperative game theory that attributes a “marginal contribution” to each feature, thereby providing a transparent, quantitative measure of its impact on the output of the model. The method ensures that the contributions of all features are fairly allocated according to the ability to change the forecasting results. Then, the Sun Mountain dataset is selected for the SHAP analysis, which includes more diverse weather variations. It provides a better understanding of the contribution of each meteorological feature to the forecasting results under different weather conditions. Specifically, the SHAP analysis quantifies the contribution of each feature, showing that higher SHAP values correspond to a greater impact on the forecasting. The SHAP results indicate that humidity is the most important feature influencing PV power forecasting. Irradiance, as the primary transient indicator, is included as an input variable in the model but was excluded from the SHAP calculation to more accurately quantify the contributions of other meteorological features. Additionally, PV panel temperature and atmospheric pressure influence PV power forecasting under certain conditions. When the temperature is too high or the air pressure is too low, the efficiency of the PV system is affected, thereby influencing the forecasting accuracy. Figure 18 clearly shows the extent to which these features impact the forecasting results.

Specifically, under sunny conditions, the weather is typically characterized by high irradiance, low humidity, high panel temperature, and high atmospheric pressure. In this case, irradiance is the primary influencing factor, while the contribution of humidity is only 0.2 and is negatively correlated with PV power. Higher panel temperature is also negatively correlated with power, with a contribution of about 0.2, while high atmospheric pressure has almost no effect on power. Under rainy conditions, the weather is typically characterized by low irradiance, high humidity, low panel temperature, and low atmospheric pressure. In this case, humidity contributes nearly 0.6 and is positively correlated with PV power. Lower panel temperature has almost no contribution to power, while lower atmospheric pressure is negatively correlated with power, and the contribution of low pressure may reach 0.6.

Conclusion

For the problem that PV generation is random and fluctuating, and considering the various environmental factors, the forecasting accuracy is easily influenced, a PV power forecasting model combining multifactorial chaotic feature extraction and CC-TF-BiGRU. Under various conditions, the comparison experiments are conducted with different models.

-

(1)

Considering the influence of surface solar radiation and the chaotic nature for PV power, the forecasting method presented in the research successfully extracts characteristic data that impact PV power generation.

-

(2)

Under complex weather conditions, the forecasting accuracy for the TF-BiGRU model is effectively improved. Compared with single model, the average RMSE are reduced by 65.84%, 51.34% and 46.04%, the average MAE are reduced by 62.7%, 54.68% and 47.04%, and the R2 is improved by about 4.38%, 8.65%, 8.55%.

-

(3)

To further validate the effectiveness of the model presented in this paper, the average RMSE was reduced by 34.98%, 33.97%, and 25.46%, the average MAE was reduced by 52.03%, 37.05%, and 25.46%, and the R² was improved by approximately 2.12%, 3.79%, and 3.33%, respectively, compared to other hybrid models under different weather conditions.

A key innovation of this work lies in the training mechanism of the BiGRU model. Unlike traditional methods that rely on feature extraction via CNN and subsequent forecasting, the proposed method integrates the output of the GBDT model and the output of the previous hidden layer through a weighted fusion approach. It not only accelerates convergence but also avoids the errors typically associated with multi-step rolling predictions. This enhanced ability to track real-world fluctuations and maintain low errors highlights the superiority of the proposed method in addressing the challenges of PV power forecasting.

This study provides valuable insights for future research and practical applications, especially in dealing with complex weather changes and large-scale data sets. The future will focus on expanding the applicability of the model by incorporating a wider range of environmental factors and extending the time horizon of the data to improve forecasting robustness under diverse conditions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, H. et al. Short-term photovoltaic power forecasting based on a feature rise-Dimensional two-layer ensemble learning model. Sustainability 15, 15594 (2023).

Guo, X., Mo, Y. & Yan, K. Short-term photovoltaic power forecasting based on historical information and deep learning methods. Sensors 22, 9630 (2022).

Iheanetu, K. J. Solar photovoltaic power forecasting: A review. Sustainability 14, 17005 (2022).

Mirza, A. F., Shu, Z., Usman, M., Mansoor, M. & Ling, Q. Quantile-transformed multi-attention residual framework (QT-MARF) for medium-term PV and wind power prediction. Renew. Energy. 220, 119604 (2024).

Yu, S., Han, R., Zheng, Y. & Gong, C. An integrated AMPSO-CLSTM model for photovoltaic power generation prediction. Front. Energy Res. 10, 815256 (2022).

Akhter, M. N. et al. An hour-ahead PV power forecasting method based on an RNN-LSTM model for three different PV plants. Energies 15, 2243 (2022).

Wang, Y., Fu, Y. & Xue, H. DMCS-WNN prediction method for photovoltaic power generation taking into account solar radiation and chaotic feature extraction. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 39, 190081 (2019).

Gu, B. et al. Forecasting and uncertainty analysis of day-ahead photovoltaic power based on WT-CNN-BiLSTM-AM-GMM. Sustainability 15, 6538 (2023).

Roy, A. et al. Development of a day-ahead solar power forecasting model chain for a 250 MW PV park in India. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 14, 973–989 (2023).

Macaire, J., Zermani, S. & Linguet, L. New feature selection approach for photovoltaic power forecasting using KCDE. Energies 16, 6842 (2023).

Park, S. et al. Prediction of solar irradiance and photovoltaic solar energy product based on cloud coverage Estimation using machine learning methods. Atmosphere 12, 395 (2021).

Liu, W. et al. Machine learning applications for photovoltaic system optimization in zero green energy buildings. Energy Rep. 9, 2787–2796 (2023).

Mo, H., Zhang, Y., Xian, Z. & Wang, H. Photovoltaic (PV) power prediction based on ABC-SVM. IOP Conf. Ser. : Earth Environ. Sci. 199, 052031 (2018).

Kang, Z. et al. Vision Transformer-based photovoltaic prediction model. Energies 16, 4737 (2023).

Rahman, N. H. A., Hussin, M. Z., Sulaiman, S. I., Hairuddin, M. A. & Saat, E. H. M. Univariate and multivariate short-term solar power forecasting of 25MWac Pasir Gudang utility-scale photovoltaic system using LSTM approach. Energy Rep. 9, 387–393 (2023).

Tian, C. et al. Photovoltaic power prediction based on dilated causal convolutional network and stacked LSTM. MBE 21, 1167–1185 (2023).

Wang, K., Qi, X. & Liu, H. Photovoltaic power forecasting based LSTM-Convolutional network. Energy 189, 116225 (2019).

Wang, S., Liu, S. & Guan, X. Ultra-short-term power prediction of a photovoltaic power station based on the VMD-CEEMDAN-LSTM model. Front. Energy Res. 10, 945327 (2022).

Ramu, P. & Gangatharan, S. An ensemble machine learning-based solar power prediction of meteorological variability conditions to improve accuracy in forecasting. J. Chin. Inst. Eng. 46, 737–753 (2023).

Wang, F., Zhen, Z., Wang, B. & Mi, Z. Comparative study on KNN and SVM based weather classification models for day ahead short term solar PV power forecasting. Appl. Sci. 8, 28 (2017).

Ledmaoui, Y. et al. Forecasting solar energy production: A comparative study of machine learning algorithms. Energy Rep. 10, 1004–1012 (2023).

Zhang, L., Guo, Z., Tao, Q., Xiong, Z. & Ye, J. XGBoost-based short-term prediction method for power system inertia and its interpretability. Energy Rep. 9, 1458–1469 (2023).

Tian, J., Ooka, R. & Lee, D. Multi-scale solar radiation and photovoltaic power forecasting with machine learning algorithms in urban environment: A state-of-the-art review. J. Clean. Prod. 426, 139040 (2023).

Tang, P., Chen, D. & Hou, Y. Entropy method combined with extreme learning machine method for the short-term photovoltaic power generation forecasting. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 89, 243–248 (2016).

Liu, R., Peng, M. & Xiao, X. Ultra-short-term wind power prediction based on multivariate phase space reconstruction and multivariate linear regression. Energies 11, 2763 (2018).

Lu & Cai Jiang. Parameter selection of phase space reconstruction based on improved C-C method. J. Syst. Simul. 19, 2527 (2007).

Wang, J., Li, P., Ran, R., Che, Y. & Zhou, Y. A short-term photovoltaic power prediction model based on the gradient boost decision tree. Appl. Sci. 8, 689 (2018).

Zhang, H. & Zhu, T. Stacking model for photovoltaic-power-generation prediction. Sustainability 14, 5669 (2022).

Wang, S. & Ma, J. A novel GBDT-BiLSTM hybrid model on improving day-ahead photovoltaic prediction. Sci. Rep. 13, 15113 (2023).

Zhang, C., Peng, T. & Nazir, M. S. A novel integrated photovoltaic power forecasting model based on variational mode decomposition and CNN-BiGRU considering meteorological variables. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 213, 108796 (2022).

Shi, Y., Zhang, L., Wang, S., Li, W. & Tong, R. A short-term photovoltaic power interval forecasting method based on fuzzy granular computing and CNN-BiGRU. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 19, 306–314 (2024).

Li, J., Li, R., Jia, Y. & Zhang, Z. Prediction of short-term photovoltaic power via codec neural network and mode decomposition based deep learning approach. Energy Sci. Eng. 10, 1794–1811 (2022).

Kothona, D., Panapakidis, I. P. & Christoforidis, G. C. Day-ahead photovoltaic power prediction based on a hybrid gradient descent and metaheuristic optimizer. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 57, 103309 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (51974151), Key Laboratory Foundation of Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (LJZS003), Research Projects of Department of Education of Guangdong Province (2024ZDZX1053), and Shenzhen Polytechnic University Research Fund (6025310056 K).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.X.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing-review & editing. Z.Z.: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Validation. Z.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing-original draft. S.X.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing-review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, G., Zhang, Z., Lin, Z. et al. The development of CC-TF-BiGRU model for enhancing accuracy in photovoltaic power forecasting. Sci Rep 15, 13790 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99109-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99109-2