Abstract

Ultrasound (US)-mediated delivery is considered relatively safe and achieves tissue-specific targeting by simply adjusting the application site of the physical energy. Moreover, combining US with micro- or nanobubbles (MBs or NBs), which serve as US contrast agents, enhances the delivery of drugs, genes, and nucleic acids which also functioning as a tool for US. The performance of US-responsive MBs and NBs, including their therapeutic outcomes, is influenced by the bubble manufacturing methods. Furthermore, productivity and scalability must also be considered for clinical applications. Among various NBs fabrication techniques, microfluidic technology has emerged as a promising approach. However, the potential of NBs generated by microfluidics for drug delivery remains unexplored. In this study, US-responsive NBs were prepared using a microfluidic device, providing a single step gas-filling operation and rapid production method not only for US imaging but also for gene delivery. The effectiveness of these NBs was subsequently evaluated. The preparation conditions for the microfluidic NBs (MF-NBs) were optimized based on their physical properties, including particle size, number concentration, and their performance as US agents. Gene delivery capability was assessed in various tissues, including muscles, heart, kidney, and brain. The results demonstrated that MF-NBs exhibit high monodispersity, enhance US imaging, achieve widespread distribution following administration (including in brain tissue), and enable gene delivery to irradiated areas. These findings suggest that MF-NBs, with their high productivity and uniformity, are promising candidates for practical applications in US imaging, gene delivery, and nucleic acid delivery systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gene therapy and nucleic acid-based therapeutics have gained significant attention for treating refractory diseases, including central nervous system diseases, cancer, genetic disorders, and ischemic conditions. Recent advancements in therapeutic modalities have led to rapid development and increasing approvals. For instance, in 2018, the RNAi-based drug Onpattro (patisiran), received approval from the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat hereditary amyloidogenic transthyretin amyloidosis. Additionally, messenger RNA (mRNA) encoding the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has been utilized in vaccines against COVID-19. More recently, the FDA approved Beqvez (fidanacogene elaparvovec) for in vivo gene therapy targeting moderately-severe to severe hemophilia B (congenital factor IX deficiency).

For effective and safe clinical applications, a drug delivery system (DDS) capable of localized delivery to target cells and tissues is critical. Ultrasound (US)-mediated delivery is considered a safe approach for achieving target-specific delivery by directing physical energy to a specific site. This modality is adaptable for delivering small molecules, plasmid DNA (pDNA), mRNA, small interfering RNA (siRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and adeno-associated viruses1,2,3,4,5. When used with microbubbles (MBs), a US contrast agent, the oscillation and cavitation effects of the bubbles enhance cell membrane permeability6,7. Stable oscillations of MBs occur under low acoustic pressure, a process known as stable cavitation. At higher acoustic pressures, these oscillations become more vigorous and unstable, eventually leading to bubble collapse and destruction—a phenomenon called inertial cavitation. These cavitation phenomena significantly enhance the permeability of biological barriers, including the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and substantially increase drug and gene uptake, even with low-intensity US. However, MBs face challenges in accessing small vessels. In contrast, nanobubbles (NBs)—submicron bubbles with diameters typically less than 500 nm—are under development and show promise for achieving higher densities in smaller vessels8,9.

Various NBs fabrication techniques cater to applications in medical, environmental, agricultural, and other fields. In the medical and biomedical contexts, NBs often feature a shell of albumin or phospholipids and encapsulate US contrast gas, serving as drug delivery tools and contrast agents. Traditional NBs generation methods include mainly agitation and sonication10,11,12,13. However, these methods have limitations in achieving high productivity and monodispersity key requirements for clinical applications. Microfluidics, an emerging technology, offers a promising solution for NBs generation. It provides cost-effective devices, precise control, and highly automated processes with minimal operator intervention. This technology has already been widely adopted for preparing lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), such as those used in the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. Microfluidic techniques ensure high productivity and uniformity in nanoparticle production. Incorporating gases into lipids using microfluidic technology has also been explored and holds potential as a new standard for producing MBs/NBs14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22.

Despite the use of conventional MBs/NBs for imaging and gene delivery, the application of MBs/NBs prepared using microfluidic technology has been less explored for gene delivery, even though their physical properties and potential as imaging tools have been reported. For these formulations to be practical as theranostic tools for both diagnostics and therapeutics, it is essential to develop a method for preparing MBs/NBs with high particle uniformity and productivity, that can also function as effective delivery tool.

In this study, US-responsive microfluidic NBs (MF-NBs) were prepared using a micromixer with staggered herringbone channels, which is known for their efficient high-speed mixing capabilities. The preparation conditions for MF-NBs were optimized to achieve high uniformity and productivity, and their usability as gene delivery tools was subsequently evaluated. pDNA was used as a model drug because it has a larger molecular size than mRNA, siRNA, and miRNA. While nucleic acids like siRNA and mRNA are delivered to the cytoplasm of target cells, pDNA requires delivery to the cell nucleus. If pDNA can be successfully delivered using this method, it could be more broadly applicable to various therapeutic modalities. Additionally, this study examined the potential of the MF-NBs for gene delivery to the brain across the blood-brain barrier (BBB), a challenging site for gene delivery23,24. Based on these experiments, a novel method for generating NBs with high productivity and monodispersity using microfluidic devices is proposed. Furthermore, MF-NBs have been demonstrated as a theranostic agent using US for applications in various organs, including the brain (Fig. 1).

Results

Preparation of NBs using a micromixer of microfluidics

NBs were prepared in a single step using a micromixer system (Fig. 1). Generally, the size and particle number concentration of LNPs are controlled by flow conditions25. Similarly, the physical properties of NBs were influenced by variations in the gas pressure and lipid solution flow rate. A pulseless pump was used to control the flow of lipid solutions into the micromixer chip, operating at pressures ranging from 0 to 6 bar. The inflow of C3F8 gas was regulated by a pressure regulator attached to a gas cylinder.

Maintaining a balance between the gas and lipid solution pressures was critical. Excessive lipid solution pressure increased flow rates, preventing the gas from being encapsulated in the lipid membranes. Conversely, excessive gas pressure lowered the lipid solution flow rate, causing backflow of the lipid solutions. Under equal gas and lipid pressures, NBs were successfully formed across all tested pressure conditions, ranging from 1 bar/1 bar to 6 bar/6 bar (Fig. 2a, b, c). Higher pressures accelerated the production of MF-NBs, and the pressure ratio had minimal impact on the zeta potential of the MF-NBs.

However, uniformity and productivity of the NBs depended on the preparation conditions. Variations in particle number concentration and particle size were observed between pressure conditions from 1 bar/1 bar to 4 bar/4 bar. Additionally, gas retention and in vivo stability under each condition were evaluated using US imaging of the mouse heart after tail vein injection of MF-NBs (Fig. 2d, e). The heart has a high volume of blood flow and a large influx of administered MF-NBs into the bloodstream, making the mouse heart a suitable organ for evaluating the gas retention capacity of MF-NBs. Although MF-NBs acted as contrast agents under all conditions, the contrast was lower at 1 bar/1 bar, indicating poor gas inclusion efficiency within the lipid membranes.

Based on these findings, MF-NBs prepared at 6 bar/6 bar conditions were selected for subsequent studies due to their ability to be produced quickly (approximately 500 µL/min) and stably with high uniformity.

Influence of mixer chip inflow control pressure on mean particle size (a), particle concentration (b), and zeta potential (c) of MF-NBs (gas pressures/lipid solution flow control pressures: 1 bar/1 bar–6 bar/6 bar) was evaluated. (d) Ultrasound images of the mouse heart at 5 min post-injection under each pressure condition of MF-NBs (5 µg/100 µL). Red circles indicate the region of interest (ROI). (e)The heart was imaged using diagnostic ultrasound (12 MHz) 1–15 min after injection of MF-NBs (5 µg/100 µL), and the mean pixel intensity within the ROI was calculated.

Characterization and stability of MF-NBs

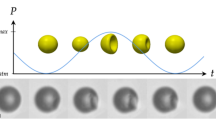

As shown in Fig. 3a, the microfluidic process converted the lipid solution into white, cloudy MF-NBs. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), an increasingly critical tool for visualizing MBs/NBs26,27, was used to observe MF-NBs. Cryo-EM images of MF-NBs confirmed that they were approximately spherical and contained gas-filled monolayers (Fig. 3b).

The size distribution of MF-NBs was measured using laser diffraction, yielding a particle concentration of 2.22 × 1013 ± 2.97 × 1012 particles/mL, and an average size of 158.7 ± 0.58 nm (Fig. 3c). To assess the stability of MF-NBs, their concentration and size were measured one week after preparation. Laser diffraction analysis indicated no changes in particle concentration (Fig. 3d) or size (Fig. 3e), suggesting that MF-NBs were highly stable when stored at 4°C for 1 week.

Characterization and stability of MF-NBs. (a) Visualization of the lipid solution (left) and MF-NBs (right). (b) Cryo-EM image of MF-NBs (scale bars, 100 nm). (c) Particle size distribution measured by laser diffraction. (d) Particle concentration 1 week after preparation (1-week-old) compared to the initial preparation (Fresh). (e) Particle size of Fresh MF-NBs and 1-week-old MF-NBs.

US imaging in vivo

The efficacy of MF-NBs as a US contrast agent was evaluated through in vivo US imaging of the mouse heart. MF-NBs were injected into the tail vein, and contrast intensity was assessed to demonstrate their effectiveness as an imaging tool. As shown in Fig. 4, MF-NBs exhibited effective contrast properties, with similar performance observed one week after preparation compared to immediately post-preparation.

Delivery of pDNA into various organs using a combination of MF-NBs and US exposure

US-mediated gene transfer, known as sonoporation, induces transient membrane permeabilization, significantly enhancing the uptake and expression of pDNA in cells across various organ systems. To improve the efficiency of sonoporation-based gene delivery, MBs are commonly used as US contrast agents. Based on this principle, we evaluated whether MF-NBs combined with US exposure could serve as effective gene delivery tools for various organs.

The in vivo gene transfection efficiency of pDNA encoding a luciferase gene was assessed via systemic administration of MF-NBs, injected into the tail vein of male ICR mice. Immediately following injection, the tibialis muscle of each mouse was exposed to US. Luciferase activity was analyzed five days later. MF-NBs with US exposure exhibited higher luciferase activity compared to other control groups, although the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 5a and b).

To assess the stability of MF-NBs, refrigerated samples stored for one week were used for systemic injection. The tibialis muscle of mice was exposed to US in the same manner, and luciferase activity was measured. The results showed no significant difference in luciferase activity between freshly prepared and one-week-old MF-NBs, indicating high stability.

We further evaluated gene transfer efficiency using pDNA encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP). GFP gene expression was observed in the muscle fibers of the US-exposed region (Fig. 5c), demonstrating the effectiveness of MF-NBs as gene delivery tools when combined with US exposure.

Additionally, we performed gene transfer to tissues, including the heart and kidneys, and analyzed the effects on various organs not exposed to US (Fig. 5d, e, f, and g). MF-NBs and pDNA encoding a luciferase gene were administered intravenously, and specific organs were irradiated with US. The following day, major organs were collected, homogenized, and analyzed for luciferase activity. The results demonstrated that the systemic administration of MF-NBs and pDNA in combination with US significantly increased gene expression, in US-exposed tissues compared to non-exposed organs. Furthermore, these results were not obtained by US irradiation alone, as was the case for gene delivery to the tibialis muscle (see Supplementary Fig. S1 online). These results demonstrate the importance of NBs as a driving force for US-mediated gene delivery.

Systemic gene delivery into the various organs using a combination of MF-NBs and US exposure (Frequency: 1 MHz; Duty: 50%; Intensity: 2 W/cm2) to the tibialis anterior muscle, heart, and kidney. Each sample containing MF-NBs 120 µg and pDNA 50 µg was administered via intravenous injection. Then, the targeted organ was exposed to US. After the treatment, tissue samples of the heart and kidney were collected on day 1, and of the tibialis anterior muscle on day 5. (a, d, e) show in vivo luciferase imaging. The photon counts are indicated by pseudo-color scales. (b) shows luciferase expression at 5 days post-transfection. White column: untreated. (c) expression of GFP (green) on day 5. DAPI, blue. Scale bar, 100 nm. (f, g) represent luciferase expression in each organ (lung, heart, diaphragm, liver, kidney, and spleen) at one day post-transfection. (a, b, c): Tibialis anterior muscle was irradiated with US for 2 min. (d, f): Heart was irradiated with US for 4 min. (e, g): Right kidney was irradiated with US for 2 min. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 3–4). ** indicates p < 0.001 using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

Application of MF-NBs for BBB opening and gene delivery to the brain

Previous studies have demonstrated that the combination of MBs/NBs with transcranial US enhances BBB permeability, enabling drug delivery to brain tissue23,24,28,29,30. To assess the effect of MF-NBs in combination with low-frequency focused US (FUS), on BBB permeability, we conducted Evans blue (EB) uptake analysis. EB binds stably to serum albumin, and its extravasation indicates increased vascular or BBB permeability31. In our previous study, we reported that EB extravasation peaked 3 h after the administration of NBs and high-intensity FUS exposure, gradually decreasing thereafter29.

In this study, mice were intravenously injected with EB and MF-NBs, followed by FUS exposure to the left hemisphere. After 3 h, the mice were perfused intravenously with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing heparin. The brains were sectioned into left and right hemispheres to observe EB extravasation and measure its levels. As shown in Fig. 6a and b, localized BBB disruption was observed at the FUS-exposed site, with no disruption at the non-exposed site. These results suggest that the combination of MF-NBs and FUS enhances BBB permeability. Additionally, the BBB opening facilitated by MF-NBs and FUS allowed fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran to penetrate the brain parenchyma (Fig. 6c). Finally, we evaluated gene transfection efficiency. Luciferase activity in the left hemisphere was significantly higher in subjects treated with MF-NBs and FUS compared to controls (Fig. 6d and e).

Application of MF-NBs in blood-brain barrier (BBB) opening and gene delivery to the brain. Low-frequency focused ultrasound (FUS) conditions: Frequency 470 kHz, Burst rate 2 Hz, Duty 2%, Intensity 0.3 MPa, Time 60 s. Left cerebral hemisphere: FUS-exposed site. (a) Distribution of BBB disruption by extravasation of Evans blue (EB). (b) The amount of EB extravasation in the cerebral hemisphere. Mice were injected in the tail vein with EB (100 mg/kg body weight). After 5 min, they were injected with MF-NBs (120 µg/mouse) and exposed to FUS. On day 1 after the treatment, tissue was collected. (c) Distribution of FITC-dextran 3 h after the US irradiation. FITC-dextran (70 or 150 kDa; 2 mg/mouse) and MF-NBs (120 µg/mouse) were intravenously administered to mice, and the left cerebral hemispheres were exposed to FUS. After 3 h, the brains were collected. The brain sections were sliced at 30 µm. The nuclei were stained with DAPI. FITC-dextran, green; DAPI, blue. (d, e) Delivery of pDNA into the brain using a combination of MF-NBs and FUS exposure. MF-NBs and pDNA encoding the luciferase gene were intravenously administered to mice, and the left cerebral hemispheres were exposed to FUS. Each tissue was collected 24 h after the treatment, and the luciferase gene expression was determined. The activity is expressed in relative light units (RLU) per mg of protein. Each value represents the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). * indicates p < 0.01 using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

Brain imaging by NBs (MF-NBs; combined with US) compared to MBs

We first demonstrated that MF-NBs reached the brain after intravenous administration and were detected using diagnostic US (Fig. 7a). Three seconds after administration, MF-NBs were visualized flowing into the brain, indicating successful brain contrast. Next, MF-NBs and MBs were compared as contrast agents using diagnostic US. The US contrast conditions were optimized separately for MF-NBs and MBs. The contrast images showed that the distribution area of MF-NBs was more extensive and dispersed than that of MBs (Fig. 7b). Quantification of the contrast area using ImageJ software revealed that MF-NBs provided a more stable and broader contrast area compared to MBs (Fig. 7c).

Brain imaging using MF-NBs in combination with US. (a) Microvascular imaging of the brain using MF-NBs (3.75 µL/g body weight) 5 and 10 s after injection. (b) Representative US contrast image of MF-NBs and microbubbles 15 s after injection (c) The area of US contrast (contrast area/ brain area × 100 [%]). Quantitative analysis (measurement of pixel area) was performed using Image J software.

Discussion

In this study, the instantaneous preparation of NBs using microfluidic devices was demonstrated. The production of MBs/NBs with microfluidic technology has been reported previously, and it is clearly possible to produce uniform bubbles. However, the preparation of NBs often requires additional processing steps compared to that of MBs. For example, microfluidic MBs were prepared using a gas mixture of US contrast gas and nitrogen gas, then shrunk down to NBs by releasing nitrogen gas15,21. Methods have also been used to separate and purify NBs from the MBs/NBs solution22. Furthermore, NBs generation often results in inadequate NBs concentrations for clinical or practical applications like gene delivery.

In contrast, the MF-NBs produced in this study eliminate the need for additional work, ensure high uniformity, and achieve a high concentration of NBs. A micromixer chip specifically designed for passive stirring of fluids was utilized to achieve these results. This micromixer chip previously employed for nanoparticle synthesis, comprises 12 mixing stages, although less viscous samples can be expanded to 24 stages32,33. For this study, 12 stages were sufficient for agitating the lipid solution and gas. Passive mixing, which does not require additional energy input, employs a split-and-recombine approach to enable uniform mixing. Chaotic advection was employed to enhance the mixing process at increased flow rates. These features were integrated into the micromixer device, enabling rapid and efficient mixing.

The micromixer chip of microfluidics offers several notable advantages, including simplicity, high production speed, elimination of the need vials to be produced individually, continuous production, a single step gas-filling operation, and avoidance of gas mixing (e.g., nitrogen with US contrast gas). Actually, this method could instantly generate more than 1013 particles/mL MF-NBs, which were approximately 160 nm in diameter. Compared to agitation-based methods and other conventional techniques, MF-NBs exhibited a smaller size range and a higher number concentration34. Furthermore, our study demonstrated that MF-NBs can be continuously produced using a glass-based microchip with a flow rate of approximately 500 µL/min. Since microfluidic systems can be scaled up by increasing the number of channels or by parallelization, this method has the potential for large-scale production35.

The stability of MF-NBs after one week of refrigerated storage confirmed the production of highly stable nanoparticles (Fig. 3). MF-NBs demonstrated consistent stability in both size concentration and functionality for US imaging and gene delivery (Figs. 4 and 5). However, the long-term stability of MF-NBs, including room temperature storage, has not yet been evaluated. Multiple-bubble formulations, such as Sonazoid® (GE Healthcare Pharma, Tokyo, Japan), which was used in this study, have been approved as pharmaceutical products. These are often freeze-dried for improved versatility, stability, and ease of transport36,37,38,39. Future challenges for the clinical application of MF-NBs include the development of freeze-drying techniques to enhance stability and practicality for broader use.

To facilitate effective gene transfection and expression, a delivery system capable of transporting nucleic acids to the target site is essential. While innovative DDSs, such as LNPs for RNA delivery, have been developed, challenges remain in achieving organ- or tissue-specific gene delivery. To enhance targeting, various ligand-modified carriers and external stimuli have been applied to target sites40,41. Stimuli-responsive carrier-based delivery systems have demonstrated effective target-specific delivery, depending on the application site of the physical energy. Our research supports the utility of US-mediated delivery with NBs for specific delivery to various target tissues, including the muscles, heart, kidney, and brain. MF-NBs facilitate gene delivery to a target site at the desired time.

In neuroscience and clinical neurology, magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography are widely employed for brain imaging and disease diagnosis due to their high resolution. However, these techniques require expensive equipment and specialized facilities, in addition, computed tomography poses potential cancer risks. In contrast, US imaging provides real-time, noninvasive, inexpensive, and easy-to-use diagnostic capabilities, making it applicable in clinical scenarios and attracting considerable attention in both research and practice. Methods of US brain imaging include conventional US imaging, US elastography, transcranial Doppler imaging, contrast-enhanced US, and US localization microscopy42. Demeulenaere et al. demonstrated 3D US localization microscopy of the intact mouse brain in vivo using transcranial US and MBs43. Historically, gas-rich MBs were considered easier to detect with US technology compared to NBs. Recent advancements in US technology, however, now allow the detection of NBs. As shown in Fig. 7, NBs can reach a wider area than MBs, suggesting that MF-NBs provide a broader range of US contrast than MBs. Thus, using MF-NBs instead of MBs enables higher US contrast of the brain microvascular environment, potentially improving diagnostic sensitivity for conditions such as stroke, aneurysms, brain tumors, vascular cognitive impairment, and neurodegenerative diseases. Additionally, the increased accessibility of MF-NBs to deeper tissues offers advantages for use as a gene delivery tool. Both cancer and central nervous system tissues contain numerous neovascular and small vessels. MBs, being larger than MF-NBs, are restricted in their ability to penetrate deeper tissues. In contrast, nanosized bubbles exhibit superior access to deeper tissues. Gattegno et al. reported that NBs promote BBB opening in capillaries 2–6 μm in diameter9. Consequently, MF-NBs may demonstrate superior gene delivery capacity to the brain and cancer tissues compared to MBs.

In this experiment, gene delivery was performed in normal mice; however, future experiments will focus on mouse models of diseases. Moreover, the MF-NBs developed in this study hold potential for application to a range of genes and nucleic acids, including mRNA, miRNA, and siRNA. Previously, we developed NBs loaded with genes and nucleic acids and demonstrated their utility in systemic delivery44,45,46,47,48. In future studies, we aim to combine MF-NBs with gene- and nucleic acid-loading technologies. We expect that the combination of MF-NBs and US will be widely adopted as a theranostic system for central nervous system diseases.

Conclusions

The successful rapid and monodisperse generation of gas bubbles with a mean particle size of 200 nm or less was achieved using a microfluidic micromixer. Conventional production methods often vary in terms of gas retention and the size of NBs produced, depending on the gas-filling technique. In contrast, microfluidics ensures a high degree of uniformity, resulting in MF-NBs that are extremely stable in vivo and capable of functioning as US contrast agents. Additionally, the systemic administration of MF-NBs combined with US exposure induced cavitation, enabling selective gene delivery to US-irradiated areas. This method of producing MF-NBs shows promise as a tool for US contrast and gene delivery applications.

Methods

Materials

The lipids 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) and N-(carbonyl-methoxypolyethylene glycol 2000)-1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DSPE-PEG2000), were purchased from NOF Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). Anionic lipid, 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1’-rac-glycerol) (DPPG) was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). Perfluoropropane gas was supplied by Takachiho Chemical Industrial Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

Preparation of lipid solutions

DPPG was dissolved in a methanol: chloroform: HEPES-buffered saline (HBS) in 3:6:0.5 (v/v), while DPPC and DSPE-PEG2000 were dissolved in chloroform. The lipids were mixed at a molar ratio of 50:44:6 in 2 mL of chloroform. The organic solvent was then evaporated and completely removed using a desiccator. To form lipid solutions, lipid films were hydrated in HBS buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 150 mM NaCl) at 52°C with vortexing for 5 min, followed by sonication for 2 h.

The lipid concentration was determined using a phosphorus assay based on the Fiske protocol49. A calibration curve was established with KH2PO4 aqueous solutions ranging from 0 to 4 mM. For ashing, the liposome suspension was mixed with perchloric acid and nitric acid and incubated at 200°C for 1 h. After cooling to room temperature, ammonium molybdate tetrahydrate solution, hydrochloric acid, and freshly prepared ascorbic acid solution were added. The tubes were placed in a 60ºC water bath for 2.5 min before measuring the absorbance at 820 nm. This assay is based on the formation of a complex between inorganic phosphate from phospholipid degradation and ammonium molybdate, which is reduced by ascorbic acid to form a colored compound. A lipid concentration of 1.0 mg/mL was chosen for this study.

Generation of MF-NBs

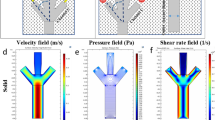

NBs were prepared using a micromixer system comprising a microfluidic device, precision pumping, fluidic elements, and software. The micromixer chip (Part No. 3200401, Dolomite Ltd., UK) is a lamination-based compact glass microfluidic device designed for the rapid mixing of gas and lipid solutions. It includes a central inlet channel for gas and two opposing inlet channels for the liquid phase. The flow was focused through a nozzle leading to a single exit channel.

The chip features a large channel etched into the lower glass piece (125 μm deep, 350 μm wide) and smaller ‘herringbone’ channels etched into the upper piece (50 μm deep, 125 μm wide). The device consists of two fused glass layers. The chip interface was mounted on a Hotplate Adaptor-Chip Holder H (Part No. 3200111, Dolomite Ltd., UK) set to 52°C to prevent ambient temperature fluctuations from impacting the mixing process.

The lipid solution was delivered to the microchip via a Mitos P-pump (Dolomite Ltd., UK), while the gas flow was regulated using a pressure regulator. Particle size and concentration of the MF-NBs were measured using a laser diffraction particle size analyzer (SALD-7500 nano, Shimadzu Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan). Zeta potential was assessed via dynamic light scattering using a Zetasizer Nano ZSP (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK).

US imaging

Male Kwl:ICR mice (5 weeks old) were anesthetized and injected with MF-NBs via the tail vein. The mouse heart was examined using an Aplio80 US diagnostic machine (Toshiba Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 12-MHz wideband transducer. Contrast harmonic imaging was performed with a mechanical index of 0.27. The mean intensities at various time points after injection in the region of interest were quantified using ImageJ.

Cryo-EM grid Preparation and imaging

A 2.5 µL aliquot of MF-NBs was applied to glow-discharged Quantifoil R1.2/1.3 200-mesh Cu grids. The grids were blotted at room temperature for 6 s under 100% humidity using a Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and rapidly frozen in liquid ethane. Cryo-EM images of MF-NBs were acquired on a Krios G4 microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operating at 300 kV and equipped with a K3 BioQuantum (Gatan) with 20 eV slit and a magnification of 81,000 × (pixel size of 1.06 Å). The image acquisition was performed using the DigitalMicrograph software (Gatan). The defocus was − 2.5 μm.

pDNA

The plasmid pcDNA3-Luc (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) is an expression vector encoding the firefly luciferase gene under the control of a CMV promoter.

The enhanced GFP gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from a pEF-GFP (#11154, Addgene) template using KOD One DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Tokyo, Japan) with the following primer pairs: forward primer: 5′-TGTCTCATCATTTTGGCAAAGCCACCATGGTGAGCAAG-3′ (Kozak sequence in bold); reverse primer: 5′-GCAGCCTGCACCTGAGGAGTTACTGTACAGCTCGTCCATG-3′. The pCAGEN vector (#11160, Addgene) was linearized by PCR amplification using KOD One DNA polymerase with the following primers: forward primer: 5′-ACTCCTCAGGTGCAGGCT-3′; reverse primer: 5′-TTTGCCAAAATGATGAGACAGC-3′. The GFP gene fragment was cloned into the linearized pCAGEN vector using the Seamless Ligation Cloning Extract (SLiCE) method50,51. The resulting construct, designated as pCAGEN-GFP, is an expression vector encoding the enhanced green fluorescent protein gene under the control of the CAG promoter. The ligated plasmid sample was transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells (BioDynamics Laboratory Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

In vivo gene delivery into skeletal muscle heart and kidney using MF-NBs and US

MF-NBs (120 µg) and pDNA (50 µg) were intravenously injected into each subject’s tail vein of male Kwl:ICR mice (5 weeks old), and the target tissue was immediately exposed to US. The US settings were as follows: Tibialis anterior muscle and kidney: Frequency: 1 MHz, Duty: 50%, Intensity: 2.0 W/cm2, Time: 2 min. Heart: Frequency: 1 MHz, Duty: 50%, Intensity: 2.0 W/cm2, Time: 4 min. A Sonitron 2000 (NEPA GENE, Co., Ltd., Chiba, Japan) was used as the US generator.

For heart and kidney studies, tissues were collected and homogenized in lysis buffer (0.1 M Tris–HCl, pH 7.8; 0.1% Triton X-100; 2 mM EDTA) 1 day after transfection. For tibialis anterior muscle, tissues were collected 5 days post-transfection. Tissues were collected following euthanasia by cervical dislocation.

Luciferase activity was measured using a luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and a Synergy HTX multimode plate reader (BioTek Japan, Tokyo, Japan) following homogenization in lysis buffer. The activity was reported in relative light units per milligram of protein.

To evaluate GFP gene expression in skeletal muscle, tissues were fixed in a 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution for 20 min at room temperature and dehydrated overnight in 20% sucrose in PBS. Tissue slices were sectioned to a thickness of 6 μm, mounted with VECTASHIELD Mounting Medium (H-1500, VectorLabs, Newark, CA, USA), and imaged using a fluorescence microscope (BZ8100, KEYENCE, Osaka, Japan).

Extravasation of EB dye

Male C57BL/6 Kwl mice (8 weeks old) were intravenously administered EB at 100 mg/kg, which stably binds to albumin in the blood. Five minutes after EB administration, MF-NBs at 120 µg/mouse were injected, and the left hemispheres were exposed to low-frequency US (Frequency: 470 kHz, Duty: 2%, Burst rate: 2.0 Hz, Intensity: 0.3 MPa, Time: 60 s). A Sonopore 3000 (NEPA GENE, Co., Ltd., Chiba, Japan) was used as the US generator. After 3 h, the treated mice were intravenously infused with PBS containing heparin (10 U/mL) as a perfusion medium at a constant rate under deep anesthesia induced using a combination of anesthetics (1.125 mg/kg medetomidine, 6.0 mg/kg midazolam, 7.5 mg/kg butorphanol) to reduce pain. The mice were perfused with PBS via the left ventricle. After perfusion and brain removal, the brains were divided into right and left hemispheres for measuring the amount of extravasated EB. The left hemispheres of untreated mice served as controls. Tissue slices with a thickness of 2 mm were prepared for imaging coronal sections. The samples were weighed, soaked in formamide solution (5 µL/mg tissue), and incubated for 24 h at 55°C. Subsequently, the concentration of the extracted dye was determined by measuring the absorbance at 620 nm using a plate reader.

Delivery of FITC-dextran to the brain

MF-NBs (120 µg/mouse) and FITC-dextran (70 or 150 kDa, 2 mg/mouse) were injected into the tail vein of male C57BL/6 Kwl mice (8 weeks old). The left hemisphere was exposed to US (Frequency: 470 kHz, Duty: 2%, Burst rate: 2.0 Hz, Intensity: 0.3 MPa, Time: 60 s). FITC-dextran was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). After 3 h, the treated mice were perfused with PBS containing heparin (10 U/mL) and 4% PFA via the left ventricle. After perfusion fixation and brain removal, each brain was fixed in 4% PFA at 4°C overnight and then immersed in 30% sucrose/0.1 M PBS at 4°C overnight. The fixed brains were frozen at − 80°C. Each brain section was sliced into 30 μm-thick slices and mounted on FRONTIER-coated slide glass (Matsunami Glass Ind., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). The sections were evaluated under a fluorescence microscope (KEYENCE: BZ8100). Nuclei were stained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole(DAPI).

Delivery of pDNA into the brain

MF-NBs (120 µg) and pDNA (50 µg) were intravenously injected into male C57BL/6 Kwl mice (8 weeks old), and the left hemispheres were exposed to FUS conditions (Frequency: 470 kHz, Duty: 2%, Burst rate: 2.0 Hz, Intensity: 0.3 MPa, Time: 60 s). Ex vivo luciferase imaging was performed 24 h after pDNA delivery. The brain tissues were collected, soaked in d-luciferin solution (0.3 mg/mL), and examined using the in vivo luciferase imaging system (IVIS; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Tissue slices with a thickness of 2 mm were prepared for imaging coronal sections. The brains were divided into left hemispheres, and tissue homogenates were prepared in lysis buffer. Luciferase activity was measured as described previously.

Brain imaging

Male C57BL/6 Kwl mice (8 weeks old) were anesthetized and injected with MF-NBs (3.75 µL/g body weight) via the tail vein. Brain examination was performed using a LOGIQ E10 US diagnostic machine (GE Healthcare) and a 24-MHz transducer (L6-24-D; GE Healthcare) with microvascular imaging at an acoustic power of 36%. Similarly, male C57BL/6 Kwl mice (8 weeks old) were anesthetized and injected with Sonazoid (3.75 µL/g body weight) via the tail vein. Brain examination was conducted using the same US diagnostic machine and transducer with microvascular imaging at an acoustic power of 60%. The area of US contrast (\({\raise0.7ex\hbox{${{\text{contrast area}}}$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{contrast area}}} {{\text{brain area}}}}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${{\text{brain area}}}$}}\, \times \,{\text{1}}00\left[ \% \right]\)) at 15 s was quantified. Quantitative analysis (measurement of pixel area) was performed using ImageJ software.

Animals

Male Kwl:ICR mice (5 weeks old) and male C57BL/6 Kwl mice (8 weeks old) were purchased from Tokyo Laboratory Animals Science Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). All treatments were performed under anesthesia induced using a combination of anesthetics (0.75 mg/kg medetomidine, 4.0 mg/kg midazolam, 5.0 mg/kg butorphanol) to reduce pain. Animal use and all relevant experimental procedures were approved by the Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences Committee on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All experimental protocols for animal studies adhered to the Principle of Laboratory Animal Care at Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences. All experimentation was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Statistical analyses

All data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3–4). Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. One-way analysis of variance was used to calculate statistical significance.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Presset, A. et al. Endothelial cells, first target of drug delivery using Microbubble-Assisted ultrasound. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 46, 1565–1583 (2020).

Kooiman, K. et al. Ultrasound-Responsive cavitation nuclei for therapy and drug delivery. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 46, 1296–1325 (2020).

Wu, J. & Li, R. K. Ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction in gene therapy: A new tool to cure human diseases. Genes Dis. 4, 64–74 (2017).

Sirsi, S. R. & Borden, M. A. Advances in ultrasound mediated gene therapy using microbubble contrast agents. Theranostics 2, 1208–1222 (2012).

Endo-Takahashi, Y. & Negishi, Y. Microbubbles and nanobubbles with ultrasound for systemic gene delivery. Pharmaceutics 12, 964 (2020).

Unger, E. C., Hersh, E., Vannan, M. & McCreery, T. Gene delivery using ultrasound contrast agents. Echocardiography 18, 355–361 (2001).

Hernot, S. & Klibanov, A. L. Microbubbles in ultrasound-triggered drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 60, 1153–1166 (2008).

Nittayacharn, P. et al. Efficient ultrasound-mediated drug delivery to orthotopic liver tumors – Direct comparison of doxorubicin-loaded nanobubbles and microbubbles. J. Controlled Release. 367, 135–147 (2024).

Gattegno, R. et al. Enhanced capillary delivery with nanobubble-mediated blood-brain barrier opening and advanced high resolution vascular segmentation. J. Controlled Release. 369, 506–516 (2024).

Huynh, E. et al. In situ conversion of porphyrin microbubbles to nanoparticles for multimodality imaging. Nat. Nanotechnol 10, (2015).

Suzuki, R. et al. Gene delivery by combination of novel liposomal bubbles with perfluoropropane and ultrasound. J. Controlled Release 117, (2007).

Negishi, Y. et al. Delivery of SiRNA into the cytoplasm by liposomal bubbles and ultrasound. J. Controlled Release 132, (2008).

Lafond, M., Watanabe, A., Yoshizawa, S., Umemura, S. I. & Tachibana, K. Cavitation-threshold determination and Rheological-parameters Estimation of Albumin-stabilized nanobubbles. Sci. Rep. 8, (2018).

Xu, J. et al. Microfluidic Generation of Monodisperse Nanobubbles by Selective Gas Dissolution. Small 17, (2021).

Paknahad, A. A., Zalloum, I. O., Karshafian, R., Kolios, M. C. & Tsai, S. S. H. High throughput microfluidic nanobubble generation by microporous membrane integration and controlled bubble shrinkage. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 653, 277–284 (2024).

Exner, A. A. & Kolios, M. C. Bursting microbubbles: how nanobubble contrast agents can enable the future of medical ultrasound molecular imaging and image-guided therapy. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 54, 101463 (2021).

Peyman, S. A. et al. On-chip Preparation of nanoscale contrast agents towards high-resolution ultrasound imaging. Lab. Chip 16, (2016).

Abou-Saleh, R. H. et al. Horizon: microfluidic platform for the production of therapeutic microbubbles and nanobubbles. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 92, (2021).

Paknahad, A. A., Zalloum, I. O., Karshafian, R., Kolios, M. C. & Tsai, S. S. H. Microfluidic nanobubbles: observations of a sudden contraction of microbubbles into nanobubbles. Soft Matter 19, (2023).

Castro-Hernández, E., Van Hoeve, W., Lohse, D. & Gordillo, J. M. Microbubble generation in a co-flow device operated in a new regime. Lab. Chip 11, (2011).

Xu, J. et al. Microfluidic generation of monodisperse nanobubbles by selective gas dissolution. Small 17, 2100345 (2021).

Batchelor, D. V. B. et al. Nested nanobubbles for Ultrasound-Triggered drug release. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 12, 29085–29093 (2020).

Hynynen, K., McDannold, N., Vykhodtseva, N. & Jolesz, F. A. Noninvasive MR imaging-guided focal opening of the blood-brain barrier in rabbits. Radiology 220, (2001).

Lipsman, N. et al. Blood–brain barrier opening in Alzheimer’s disease using MR-guided focused ultrasound. Nat. Commun. 9, (2018).

Terada, T. et al. Characterization of lipid nanoparticles containing ionizable cationic lipids using Design-of-Experiments approach. Langmuir 37, 1120–1128 (2021).

Li, M., Tonggu, L., Zhan, X., Mega, T. L. & Wang, L. Cryo-EM Visualization of Nanobubbles in Aqueous Solutions. Langmuir 32, (2016).

Hernandez, C., Gulati, S., Fioravanti, G., Stewart, P. L. & Exner, A. A. Cryo-EM visualization of lipid and Polymer-Stabilized perfluorocarbon gas nanobubbles - A step towards nanobubble mediated drug delivery. Sci. Rep. 7, (2017).

López-Aguirre, M., Castillo-Ortiz, M., Viña-González, A., Blesa, J. & Pineda-Pardo, J. A. The road ahead to successful BBB opening and drug-delivery with focused ultrasound. J. Controlled Release. 372, 901–913 (2024).

Negishi, Y. et al. Enhancement of blood–brain barrier permeability and delivery of antisense oligonucleotides or plasmid DNA to the brain by the combination of bubble liposomes and high-intensity focused ultrasound. Pharmaceutics 7, (2015).

Endo-Takahashi, Y. et al. Ternary complexes of Pdna, neuron-binding peptide, and pegylated polyethyleneimine for brain delivery with nano-bubbles and ultrasound. Pharmaceutics 13, (2021).

Yang, F. Y., Lin, Y. S., Kang, K. H. & Chao, T. K. Reversible blood-brain barrier disruption by repeated transcranial focused ultrasound allows enhanced extravasation. J. Controlled Release 150, (2011).

Swetha, K. L., Maravajjala, K. S., Sharma, S., Chowdhury, R. & Roy, A. Development of a tumor extracellular pH-responsive nanocarrier by terminal histidine conjugation in a star shaped poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid). Eur. Polym. J. 147, 110337 (2021).

Gimondi, S. et al. Microfluidic mixing system for precise PLGA-PEG nanoparticles size control. Nanomedicine 40, 102482 (2022).

Paknahad, A. A., Kerr, L., Wong, D. A., Kolios, M. C. & Tsai, S. S. H. Biomedical nanobubbles and opportunities for microfluidics. RSC Adv. 11, 32750–32774 (2021).

Maeki, M. et al. Mass production system for RNA-loaded lipid nanoparticles using piling up microfluidic devices. Appl. Mater. Today. 31, 101754 (2023).

SONTUM, P. C., DYRSTAD, Ø. S. T. E. N. S. E. N. J., HOFF, L. & K. & Acoustic properties of NC100100 and their relation with the microbubble size distribution. Invest. Radiol. 34, 268 (1999).

Sontum, P. C. Physicochemical characteristics of sonazoid™, A new contrast agent for ultrasound imaging. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 34, 824–833 (2008).

Abou-Saleh, R. H. et al. Freeze-Dried therapeutic microbubbles: stability and gas exchange. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 3, 7840–7848 (2020).

Omata, D. et al. Effects of encapsulated gas on stability of lipid-based microbubbles and ultrasound-triggered drug delivery. J. Controlled Release. 311–312, 65–73 (2019).

Zhao, Z., Ukidve, A., Kim, J. & Mitragotri, S. Targeting strategies for Tissue-Specific drug delivery. Cell 181, 151–167 (2020).

Mi, P. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery, tumor imaging, therapy and theranostics. Theranostics 10, 4557–4588 (2020).

Ren, J., Li, J., Chen, S., Liu, Y. & Ta, D. Unveiling the potential of ultrasound in brain imaging: innovations, challenges, and prospects. Ultrasonics 145, 107465 (2025).

Demeulenaere, O. et al. In vivo whole brain microvascular imaging in mice using transcranial 3D ultrasound localization microscopy. EBioMedicine 79, 103995 (2022).

Negishi, Y. et al. Systemic delivery systems of angiogenic gene by novel bubble liposomes containing cationic lipid and ultrasound exposure. Mol. Pharm. 9, 1834–1840 (2012).

Endo-Takahashi, Y. et al. PDNA-loaded bubble liposomes as potential ultrasound imaging and gene delivery agents. Biomaterials 34, 2807–2813 (2013).

Endo-Takahashi, Y. et al. Efficient SiRNA delivery using novel SiRNA-loaded bubble liposomes and ultrasound. Int. J. Pharm. 422, 504–509 (2012).

Endo-Takahashi, Y. et al. Systemic delivery of miR-126 by miRNA-loaded bubble liposomes for the treatment of hindlimb ischemia. Sci. Rep. 4, 3883 (2014).

Endo-Takahashi, Y. et al. Phosphorodiamidate morpholino Oligomers-Loaded nanobubbles for Ultrasound-Mediated delivery to the myocardium in muscular dystrophy. ACS Omega. 10, 9639–9648 (2025).

Fiske, C. H. & Subbarow, Y. The colorimetric determination of phosphorus. J. Biol. Chem. 66, (1925).

Okegawa, Y. & Motohashi, K. Evaluation of seamless ligation cloning extract Preparation methods from an Escherichia coli laboratory strain. Anal. Biochem. 486, (2015).

Okegawa, Y. & Motohashi, K. A simple and ultra-low cost homemade seamless ligation cloning extract (SLiCE) as an alternative to a commercially available seamless DNA cloning kit. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 4, (2015).

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (JP22H03978 and JP24K03314), JST SPRING (JPMJSP2134), a Nagai Memorial Research Scholarship from the Pharmaceutical Society of Japan, and The Naito Foundation in 2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Y.: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. Y.E-T.: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision. K.A., S.N., Y.O., and M.O.: Investigation, Data curation. R.T.: Resources. Y.T.: Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. H.K.: Writing—review & editing, Supervision. Y.N.: Writing—review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamaguchi, T., Endo-Takahashi, Y., Awaji, K. et al. Microfluidic nanobubbles produced using a micromixer for ultrasound imaging and gene delivery. Sci Rep 15, 14871 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99171-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99171-w