Abstract

In the last 25 years, there have been significant advances in the diagnosis and treatment of thyroid disorders. The aim of this study was to analyze 25 years of experience in thyroid surgery in high volume endocrine center in terms of demographic changes, indications for surgical treatment, the type of thyroid surgery and complications. Clinical material (3748 patients) from the years 1996–2020 was analyzed by compering two Periods: I (1996–2003) vs. II (2011–2015/2018–2020). The percentage of patients operated on for thyroid cancer increased (p < 0.00001) and the extent of thyroid surgery changing from partial to total excision was statistically significant (p < 0.00001). The increase in the extent of thyroidectomy did not affect the overall recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy (p = 0.1785), but resulted in an increase of postoperative clinical hypoparathyroidism (p < 0.00001). The introduction of new technologies, such as intraoperative nerve monitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerves had a significant impact on the changes in thyroid surgery over 25 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For years, thyroid surgery has been one of the most performed elective general surgery procedures. Every year, there are more than 30,000 thyroid surgeries performed in Poland, of which 12–15% are due to thyroid cancer1. In comparison, annually there are 45,000 in France, 60,000 in Germany and over 4000 in Austria2.

Up until the late 19th century, the mortality risk following thyroid surgery was up to 40%. This resulted in such procedures being banned by the French Academy of Medicine as well as other institutions. Prominent American surgeon—David Gross—warned against performing them3,4,5. Nowadays, the procedure is considered safe with its mortality rate approaching 0%. The most significant progress was made at the turn of the 20th century thanks to the achievements of the magnificent seven of thyroid surgery—Billorth, Kocher, Halsted, Mayo, Chile, Danhill and Lahey. The introduction of modern anesthesia, new surgical instruments, the principles of antiseptics as well as the safe excision of the thyroid gland, reduced the mortality rate after thyroid surgery to 0.5%6. This in turn increased the number of thyroid surgeries being performed. Despite all the progress that has been made, these surgeries still pose a risk of complications such as hemorrhage which requires re-operation, vocal cord paralysis and hypoparathyroidism, which can have a significant impact on the quality of life of a patient. This is why most efforts in recent decades have focused minimizing these risks. Will the so-called “myth of the 1% in thyroid surgery”7, regarding the number of complications after thyroid surgery, be achieved in the twenty-first century? The introduction of new techniques in the last 25 years in thyroid surgery seem to have been groundbreaking. The implementation and standardization of laryngeal nerve monitoring techniques8,9,10, methods to facilitate intraoperative identification of the parathyroid glands11,12 and minimally invasive techniques13 such as robotic surgery14 or transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach—TOETVA—thyroid surgery performed without leaving a surgical scar15 have all been undoubted milestones.

The indications for a patient to undergo thyroid surgery remain a separate issue. The number of thyroid surgeries for thyroid cancer has tripled16 in the past three decades with further projections indicating that the number will continue to rise.

Are we facing an epidemic of thyroid cancer, or is the increase in thyroidectomies due to the widespread availability of thyroid ultrasound and the ease of fine needle aspiration biopsy17,18?

In addition, modern treatment options for Graves’ disease and other inflammatory and non-neoplastic thyroid diseases are changing the indications for surgery. The demonstration of the safety of radioiodine therapy in benign thyroid conditions and the possibility of thyrostatic treatment provides an alternative to surgical management19,20. The last two decades in thyroid surgery have seen a rapid development of ablative techniques, especially for benign thyroid lesions, which also have the potential to change the indications for thyroid surgery to be necessary21.

What has changed in thyroid surgery in the last quarter of a century? What are the trends that can be noticed in this procedure? Have new technologies minimized the complication rate? In which direction is endocrine surgery heading for at the beginning of the twenty-first century?

The purpose of this study was to analyze 25 years of experience in thyroid surgery at a center specializing in the surgical treatment of thyroid disorders in terms of patient demographics, indications for surgical treatment, the type of thyroid surgery performed, and postoperative complications. The impact of the introduction of neuromonitoring on changes in endocrine surgery was evaluated.

Materials and methods

On February 28, 2019 and on May 13, 2020, the consent of the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Wroclaw was obtained (KB-156/2019; KB-280/2020).

This study aimed to investigate the changes and advancements in thyroid surgery over the past 25 years at the Medical University of Wroclaw, with a focus on clinical diagnosis, indications for surgical treatment, types of surgeries performed, postoperative complications, and secondary operations on the thyroid gland.

A total of 25 years of experience in endocrine surgery at the Department of General, Gastroenterological, and Endocrine Surgery, later renamed the Department of General, Minimally Invasive, and Endocrine Surgery in 2018. The observation period spanned from 1996 to 2020, with a total of 3748 patients and 7285 recurrent laryngeal nerves (RLNs) at risk of injury.

Data were collected in two distinct periods:

-

Period I (1996–2003): Medical records of 2707 patients undergoing thyroid surgery (5414 RLNs at risk).

-

Period II (2011–2015 and 2018–2020): Medical records of 1041 patients (1871 RLNs at risk).

Demographics of the patients treated in both groups are shown in Table 1.

Prior to December 2010, RLN identification was done only by means of visualization; in January 2011, intraoperative nerve monitoring (IONM) was utilized in thyroid surgery for the first time. The neuromonitoring was implemented and carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the International Study Group for Neuromonitoring (ISGN)9. All thyroid procedures were performed with a Medtronic neuromonitoring device (NIM-3 Medtronic, Jacksonville, Florida, USA). Electromyographic signal acquisition (EMG) was performed using surface electrodes integrated into the endotracheal tube (Flex Medtronic). A monopolar stimulating probe was used for nerve stimulation with a current amplitude of 1 mA (range 0.5–1.5 mA) and 3 Hz pulses of 200 ms each for 1–2 s. This change in RLN identification was the primary methodological difference that could influence outcomes.

The research study aimed to compare Period I (1996–2003) vs. Period II (2011–2015, 2018–2020) to answer the question: how has thyroid surgery changed over the past 25 years, with special attention paid to:

-

I

Demographic data and clinical characteristics of patients.

-

II

Clinical diagnosis and indications for surgical treatment.

-

III

Type of thyroid surgeries performed.

-

IV

Postoperative complications: vocal fold paralysis, postoperative hypoparathyroidism, bleeding after thyroid surgery.

-

V

Secondary operations on the thyroid gland.

All patients qualified for thyroid surgery were euthyroid; TSH and fT4 were determined preoperatively. Thyroid ultrasound and biopsy were performed in patients with nodular disease. In addition, standard preoperative tests were performed in preparation for surgery: blood morphology, biochemical blood tests, blood type, chest X-ray and electrocardiograms.

Surgical treatment: all thyroid surgeries were performed at a single endocrine surgery center, involving two generations of surgeons, the so-called junior and senior surgeons; all surgeries were performed in a classical manner with a typical Kocher collar incision neck opening; no minimally invasive-laparoscopic surgeries were performed.

The number of vocal fold paralysis was calculated both per patient and per number of RLNs at risk of injury. Transient vocal fold palsy was defined as resolving up to 12 months after thyroid surgery. Permanent paralysis was defined as paralysis persisting more than 12 months after surgery. The total number of cases of paralysis was defined as the sum of all paralysis: transient and permanent, assessed in the immediate period after thyroid surgery. Patients with preoperative vocal fold paralysis were excluded from the study.

Postoperative hypoparathyroidism: in Period I: PTH, calcium and phosphorus testing were determined only in patients with symptomatic tetany, while in the second period all patients had PTH, calcium and phosphorus levels determined before as well as after thyroid surgery. Hypoparathyroidism in the immediate postoperative period was evaluated; the collected material did not allow for hypoparathyroidism differentiation into temporary and permanent.

Postoperative bleeding: patients who required reoperation due to a hematoma in the surgical site during the immediate postoperative period.

Demographic and clinical data, surgical details, and complications were recorded in an Excel database for analysis.

Statistical analysis was based on data collected from N = 3748 patients, which constituted the study sample from the general population. The variables analyzed included nominal (categorical), dichotomous (binary) and quantitative (continuous) data. The choice of statistical techniques used was dictated by the nature of the random variables being compared with each other.

To characterize the quantitative variables, basic descriptive statistics were calculated for them: mean value, standard deviation, and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for mean value and standard deviation. The normality of quantitative variables was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk W-test, and homogeneity of variance was assessed with the Levene and Brown-Forsythe tests, assuming a significance level of α = 0.05. For nominal variables, including dichotomous ones, tables of counts were created containing absolute raw counts and the percentage and cumulative contribution of each category to the nominal variable.

Pearson’s Chi-squared (χ2) test was used to assess the statistical significance of correlations between nominal variables.

In assessing the statistical correlation between dichotomous and quotient variables, two types of statistical analyses were used, depending on the result of the Shapiro–Wilk W-test: the Student’s t-test for independent samples in the case of variables with a normal distribution, or the Mann–Whitney U-test in situations where the variables being compared did not meet this assumption.

A significance level of α = 0.05 was used for all statistical analyses performed. Statistical analyses were carried out using the computer program STATISTICA PL® version 13.3 with the Set Plus version 3.0 add-on.

Results

-

(I)

Demographic data and clinical characteristics of patients.

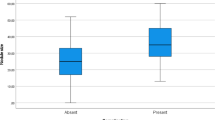

Table 1 shows demographic data and clinical characteristics of patients treated surgically for thyroid diseases in 1996–2003 (Period I) vs. 2011–2015 and 2018–2020 (Period II).

-

(II)

Clinical diagnoses, indications for surgical treatment.

Table 2 shows the clinical diagnoses of patients who underwent surgery due to thyroid disorders in Period I and Period II. Indications for thyroid surgery included nodular goiter, toxic nodular goiter, Graves’ disease (GD), inflammatory goiter and thyroid cancer changed significantly over time (p < 0.0001). In 1996–2003, operations due to inflammatory goiter accounted for 2.51%. However, in 2011–2015 and 2018–2020, they were completely eliminated. A statistically significant decrease in indications for thyroid surgery due to other non-cancerous diseases was also observed - specifically in the proportion of surgeries for toxic nodular goiter (23.64–13.93%, p < 0.00001) and Graves’ disease (10.08–4.8%, p < 0.00001). The percentage of patients treated for thyroid cancer nearly tripled (3.73% vs. 10.9%, p < 0.00001). The percentage of patients with papillary carcinoma increased nearly fourfold (2.25% vs. 8.84%, p < 0.00001).

Of the 101 patients operated on for thyroid cancer in Period I, 97 (96%) had thyroid cancer in a primary goiter, and 4 (4%) in a recurrent goiter. In contrast, in Period II, out of 105 patients with thyroid cancer: 87 (82.86%) have cancer in a primary goiter and 18 (17.14%) in a recurrent goiter.

The mean volume of goiter in Period I was greater, at 51.26 ml vs. 43.35 ml in Period II, although the differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Retrosternal goiter was significantly more common (p = 0.0068) in Period I than Period II, although tracheal constriction or displacement was more frequently observed in the later years (29.66% vs. 38.42%, p < 0.00001).

Table 3 shows the clinical diagnoses by year. The largest number of thyroid surgeries was performed in 1999–2003. Figure 1 shows the percentage distribution of diagnoses in subsequent years, noting the increasing trend among thyroid cancers and recurrent goiter and the decreasing trend among hyperactive goiter and the relatively constant trend in the levels of nodular goiter.

Therefore, over three decades, there were decreases in numbers of thyroid surgery performed for non-malignant thyroid disorders while thyroid cancer operations were performed more often. Easier access to ultrasound examination and fine needle aspiration biopsy seems to be responsible for the increas in the number of patients operated on due to thyroid carcinoma.

-

(III)

Type of thyroid surgery

Table 4 shows the types of thyroid surgeries performed between Period I vs. Period II. A statistically significant change was observed (p < 0.00001) in the extent of thyroid resection, shifting from a predominance of partial thyroid resection (87.73%) in 1996–2003 to a predominance of total thyroid resection (70.8%) or total thyroid lobe resection with isthmus (20.27%) in 2011–2015 and 2018–2020. In Period II, wedge thyroid resections and cytoreductive surgeries were no longer performed. Lobectomies were not performed in Period I, but accounted for 20.27% of the operations performed in Period II. Between 1996 and 2003, total thyroid resection was performed in 0.62% of patients with nodular goiter and in of patients with recurrent goiter, 1.42% with toxic goiter, 1.47% with inflammatory goiter and 21.78% with thyroid cancer. In contrast, during Period II, the percentage of total thyroid resections performed are: 91.23% in nodular goiter; 90.77% toxic goiter and 97.14% thyroid cancer (including lymph node dissection). Of the 101 patients operated on for thyroid cancer in Period I, 55 (54.46%) underwent re-operations of the thyroid gland due to thyroid cancer, 22 (21.78%)patients underwent the “early surgery” where re-operation is performed up to 3 days after the primary surgery and 33 (34.02%) patients underwent the “late surgery” where reoperation is performed approximately 6 weeks after the primary treatment. Reoperation of the thyroid gland due to thyroid cancer was not performed in patients with thyroid cancer in the second group.

Consequently, the introduction of neuromonitoring in 2011 had significantly increased the scope of thyroid surgery, shifting from subtotal thyroidectomy in Period I to total thyroidectomy in Period II. Utilizing IONM has explored the possibility of mapping the RLN and EBSLN (external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve), and allowed for the intraoperative prediction of nerve function with a better understanding of anatomical variants of the recurrent laryngeal nerves. This has influenced the change of surgical techniques, increasing the radicality of both primary and secondary operations.

-

(IV)

Postoperative complications

Table 5 shows complications after thyroid surgery in Period I vs. Period II.

The percentage of bleeding requiring reoperation after thyroidectomy remained below 1% in both periods (0.92% vs. 0.86%, p > 0.05)—this difference was not statistically significant. Clinical hypoparathyroidism, confirmed by reduced PTH levels and hypocalcemia, was significantly more common among patients operated on in Period II (4.84% vs. 8.93%, p < 0.00001). In both follow-up periods, it was twice as common in secondary than primary surgeries, Period I (4.66% vs. 8.33%) and Period II (8.42% vs. 15.19%) respectively. Biochemical hypoparathyroidism without clinical signs of hypocalcemia was monitored only in Period II and was more common than symptomatic hypocalcemia (8.93% vs. 12.78%).

During Period I, only 771 (28.48%) of patients had an ENT (ear, nose and throat) examination before thyroid surgery using indirect videoscopy; in Period II, all patients underwent an ENT examination preoperatively, including both indirect videoscopy and videolaryngoscopy. ENT examination after thyroid surgery was performed only among patients in Period I who presented phonation disorders in the immediate period after thyroid surgery as ENT examination after thyroid surgery was not a standard procedure at the time. In period II, all patients who qualified for the study had an ENT examination before 7 days after thyroid surgery.

Unilateral vocal fold paralysis in the immediate postoperative period was slightly more frequent in Period I than in Period II (8.27% vs. 6.53%, p = 0.0746). However, neither of these differences were statistically significant (p > 0.05). The percentage of unilateral transient paresis was Period II (0.78% vs. 2.11%; p = 0.0006), while the percentage of permanent paralysis was lower in Period II (7.5% vs. 4.42%; p = 0.0007). No statistically significant differences were observed in the incidence of bilateral paralysis in the immediate postoperative period, nor in transient or permanent paralysis in either observation period (p > 0.05). These results are consistent when paralysis is calculated per number of recurrent laryngeal nerves at risk of damage, showing that the total rate of paralysis in Period I was 5.17% vs. 4.38% Period II with no statistically significant difference (p = 0.1785). The significantly higher incidence of transient paralysis in group I (p < 0.00001) and the significantly lower incidence of permanent paralysis in group II (p = 0.0016) were again confirmed.

Other complications observed in group I included: wound infection − 4 (0.15%), urinary tract infection − 8 (0.3%), circulatory failure – 13 (0.48), respiratory failure − 24 (0.89%) and death − 11 (0.41%). Subsequently, in Period II, 3 patients developed wound infection (0.3%), and no deaths occurred in the immediate postoperative period.

In conclusion, the implementation of recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring in daily practice reduced the overall rate of vocal fold paralysis despite an expansion in the scope of thyroid surgery. At the same time, the increase in the extent of surgery in Period II resulted in an increased rate of postoperative hypoparathyroidism. Neither the implementation of nerve monitoring nor the increased extent of surgery affected the incidence of bleeding requiring reoperation in the last 3 decades.

-

(V)

Secondary surgeries on the thyroid gland

Table 6 shows the clinical diagnoses and type of thyroid surgery among patients with recurrent goiter across the study periods. Recurrent goiter was significantly more frequent in Period II (4.88% vs. 7.59%, p = 0.0013). Over the study periods, surgery for thyroid cancer was significantly more frequent in recurrent goiter (3.03% vs. 22.78%, p < 0.00001), while the number of surgeries for toxic goiter was lower in Period II (24.24% vs. 8.86%, p = 0.0053). A statistically significant change was observed in the extent of secondary thyroid surgery over the 25-year period, with a significant shift toward total rather than partial thyroid surgery in Period II (p < 0.00001).

Overall, the increase in secondary thyroid surgeries in Period II was a consequence of the predominance of partial thyroid resections in Period I.

Discussion

Although thyroid surgery is one of the most commonly performed operations in general surgery, it is mainly the domain of centers specializing in endocrine surgery due to the risk of specific surgical complications, such as loss of voice due to recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, severe post-operative hypoparathyroidism, or directly life-threatening hemorrhage22.

Performing a large number of thyroidectomies annually allows surgeons to develop expertise in thyroid surgery and allows such centers to become specialized in the treatment of thyroid disorders23,24,25,26,27.

The Department of General, Minimally Invasive and Endocrine Surgery at the Wroclaw Medical University has been involved in endocrine surgery for more than 70 years, being the reference center for the treatment of benign thyroid disorders and thyroid cancer in the Lower Silesia region. Over the last 25 years, thyroid surgery has undergone changes in surgical indications, the type of thyroid procedures performed, and the rates of postoperative complications.

The authors of this paper, a “young generation” who have been associated with the activities of the Department of General, Minimally Invasive and Endocrine Surgery for over 20 years conducted a retrospective evaluation of the activities of the Department over the last 25 years aimed to determine the current direction of thyroid surgery at the beginning of the 21st century. To isolate differences, the 25-year observation interval was divided into two time periods: early (Period I), which covered 1996–2003, and late (Period II), which covered 2011–2015 and 2018–2020. The two periods were compared in terms of changes in demographics, indications for surgery, extent of surgery, complications, and the incidence of recurrent goiter.

An important factor during this period was the introduction of IONM in 2011. Until then, the recurrent laryngeal nerve was either monitored visually or not monitored at all. This change had a significant impact on surgical techniques, the extent of surgery performed, and complication rates.

During the 25-year period, the percentage of patients with nodular goiter, toxic goiter and thyroid cancer referred for surgery changed significantly (p < 0.00001). A decrease in thyroid surgery for non-malignant indications has been observed. This reduction in surgical indications for inflammatory goiter, nodular goiter, toxic nodular goiter and Graves’ disease has led to a higher frequency of thyroid surgeries. The percentage of patients operated on for thyroid cancer more than tripled after 2011 compared to patients treated between 1996 and 2003. The increase was especially notable in cases of papillary thyroid cancer (2.25 vs. 8.84%, p < 0.00001). The incidence of other malignant neoplasms and metastatic thyroid lesions did not change (p > 0.05). This is consistent with the described trend both in Poland16,28 and worldwide17,25,29. This is undoubtedly influenced by improved access to ultrasound, and the widespread use of fine-needle aspiration biopsy30,31,32. It is difficult to determine whether the incidence of thyroid cancer is truly increasing or whether the rise is due to overdiagnosis. We found that nearly 13% of the thyroid nodules with AUS/FLUS diagnosis were malignant (34/262). There was no statistically significant difference between the two periods. However, Greek researchers investigating a similar observation period reported a slightly higher risk of malignancy in the Bethesda III category (18.42% for multinodular goiter and 20.13% for a single nodule of the thyroid, p = 0.1772)33. Therefore, the suggestion of Mulita et al. seems correct ; patients with an FNA categorized as AUS/FLUS may have a higher risk of malignancy than traditionally believed33.

On the other hand, the percentage of patients operated on for toxic goiter, especially Graves’ disease, has statistically significantly decreased, which is likely due to the increasing preference of radioiodine therapy as the primary treatment for Graves’ disease and toxic adenoma34,35. In 1996–2003, one of the indications for surgery was inflammatory goiter - Hashimoto’s disease. After 2011, Hashimoto’s disease was no longer an indication for surgery. Perhaps this is related to the proper substitutive conservative treatment of Hashimoto’s disease as there is no fibrosis of the thyroid gland to cause pressure symptoms. A significant percentage of surgical patients still have concomitant autoimmune disease, but this disease itself is no longer an indication for surgical treatment36. The goiter volume at which patients are referred for thyroid surgery decreased in later years, averaging 43.35 ml, than in the 1990s, where the average volume was 51.26 ml, although this difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). On the other hand, the percentage of patients with retrosternal goiter has decreased significantly. The average age of patients undergoing surgery has remained stable at approximately 54 years, while the percentage of patients over 65 years of age increased significantly after 2011.This supports that age is currently not a contraindication to thyroid surgery and that its safety is comparable to younger patient groups. In addition, life expectancy is increasing and the proportion of elderly patients can be expected37. Over the course of 25 years, the proportion of men operated on increased from 9:1 to 5:1, with this increase being statistically significant.An increase in BMI was also observed among surgical patients after 2011, which is in line with the worldwide problem of obesity in recent years38.

In the future, the trend of decreasing thyroid surgery for benign diseases is expected to continue due to the emergence of ablation techniques for thyroid nodules.

Aspect analyzed was the extent of thyroid gland surgery performed, and over the past quarter century, a shift has been observed from partial thyroid surgery to total resection. Between 1996 and 2003, subtotal surgeries were performed in more than 90% of patients vs. 1.7% of total thyroid gland surgeries; between 2011 and 2015 and 2018–2020, more than 94% of thyroid resection surgeries were total vs. 4% that were subtotal surgeries the results were highly statistically significant (p < 0.00001). Subtotal thyroid resection was not an optimal approach, as postoperatively diagnosed thyroid cancer required radicalization which carried nearly a 50% risk of surgical complications. The ability to identify the recurrent laryngeal nerve remains a separate issue. Admittedly, as early as 1994, Jatzko et al.39 demonstrated that identification of the RLN decreases rather than increases the risk of RLN damage and is considered the gold standard in thyroid surgery. Nevertheless, in many centers, including the authors’ institution, the RLN was not routinely identified during thyroid surgeries between 1996 and 2003. An extensive discussion of the appropriate scope of thyroid surgery occurred at the beginning of the 21st century. Between 2000 and 2005, the largest number of medical articles on the subject appear40,41,42, definitively demonstrating the superiority of total thyroid or thyroid lobe surgery over partial resection surgery. Intraoperative nerve monitoring improved knowledge of recurrent laryngeal nerve anatomy and enabled surgeons to assess nerve function during the operation. Since then, increasingly radical thyroid operations were performed not only for thyroid cancer, but also for benign goiter. Total thyroid resection has become the standard of care in most cases43,44,45.

Complications after thyroid surgery were another topic of the 25-year study. Before comparing complications between the two study periods, some limitations and weaknesses of the study should be mentioned. Over such a long period, the standard of perioperative care has evolved. Between 1996 and 2003, preoperative ENT examinations were performed in only 30% of patients, while postoperative ENT examinations were performed mainly in patients who reported phonation disorders after surgery. Therefore, the objective assessment of vocal fold paralysis is undoubtedly underestimated. The percentage of ENT examinations both before and after thyroid surgery at our center after 2011 is close to 90% of patients. Over the past 25 years, the techniques of laryngological examinations before and after thyroid surgery have changed from indirect videoscopy to videolaryngoscopy. More importantly, the awareness of performing these examinations as a standard of care in perioperative care has increased.

It should be noted that after 2011, some thyroid surgeries were performed with neuromonitoring. Objective assessment of postoperative hypoparathyroidism is hindered by the lack of routinely performed determination of PTH, calcium, and phosphorus in all patients in the immediate postoperative period, hence in 1996–2003—when PTH and calcium levels were determined only in patients with clinical signs of hypocalcemia—the incidence of this complication may have also been underestimated. Nevertheless, the accumulated material includes a large patient cohort (3748) which allows us to identify key trends in thyroid surgery. This change in surgical strategy - transitioning from partial removal of the thyroid gland to total surgery did not significantly affect the incidence of vocal fold paralysis in the immediate postoperative period. Between 1996 and 2003, the total number of RLN injuries was 5.17% vs. 4.38% in 2011–2015 and 2018–2020. These differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.1785). Admittedly, a greater extent of thyroid surgery was associated with a higher incidence of transient paralysis in Period II (0.41% vs. 1.34%, p < 0.00001), but this may reflect the greater exposure of the RLN during total resections. Interestingly and encouragingly, the rate of permanent paralysis was statistically significantly lower in the later years (4.77% vs. 3.05%, p = 0.0016), which supports the continued use of total surgeries, given the fact that there was an undoubted underestimation of RLN injuries in the earlier years. Without a doubt, the incidence of vocal fold paralysis has remained stable in recent years (despite the expanded scope of surgery) thanks to the use of neuromonitoring, which today is considered a milestone in thyroid surgery. The expansion of surgical extent increased the incidence of postoperative hypoparathyroidism after 2011 (4.84% vs. 8.93%, p < 0.00001), but here we have no objective data as to the nature of this complication, specifically whether it was temporary or permanent. Such results prompt us to look for new techniques to identify parathyroid glands during thyroid resection.

The rate of bleeding requiring reoperation has remained unchanged over 25 years, and is consistently low, below 1% (0.92% vs. 0.86%, p = 0.8646). These results are consistent with published data46. Notably, no special hemostatic devices, such as a LigaSure or Harmonic scalpel, were used during thyroid resection.

The final aspect analyzed in our 25-year study of thyroid surgery at our center was recurrent goiter. The nearly twofold increase in the number of patients with recurrent goiter in later years (4.88% vs. 7.59%, p = 0.00013) was a consequence of non-radical surgeries performed in earlier years. The malignant lesion rate exceeding 20% in recurrent goiter in recent years supports primary total thyroid resection as the optimal approach47,48,49, which should be the treatment of choice in the era of neuromonitoring.

In summary, thyroid surgery has undergone significant advancements over the past century, with the last 25 years bringing notable progress in the diagnosis of thyroid disorders and the implementation of new technologies. In the future, it seems inevitable that the number of patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer will increase, in an era when ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration biopsy are so widely available, although the possibility of active surveillance of thyroid cancer for small lesions50, and the possibility of using ablative techniques to treat them may also reduce the number of patients treated surgically for thyroid cancer51. Total excision of the thyroid gland appears to be the optimal surgical approach that does not significantly increase the rate of postoperative complications, and the implementation of neuromonitoring has a beneficial effect on the quality of surgical treatment, minimizing the risk of phonatory disorders after thyroid surgery. It is necessary to research new methods for protecting the parathyroid glands during thyroid surgery.

Finally, it is necessary to mention the limitations of the current manuscript. The lack of data from the years 2004–2010 and 2016–2017 is a weak point of this manuscript. Nevertheless, the collected data made it possible to identify trends in the surgical treatment of thyroid diseases in the period of 25 years. There is no information on the length of stay during the study period over time, which could have changed, because advances in energy devices, anesthesia and surgical techniques have influenced surgical duration, safety and the feasibility of short stay procedures. This aspect should be the subject of research in further analyses.

Conclusions

Over 25 years (1996–2020), the number of patients undergoing surgery more than tripled for thyroid cancer and doubled for recurrent goiter. A noticeable decreasing trend in operations due to Graves’ disease has also been observed. The scope of thyroid resection has shifted, from predominantly partial bilateral thyroid resection in the 1990s, to practically exclusively performing total resection surgeries for both benign and malignant thyroid conditions in recent years. The increase in the scope of surgery has not increased the rate of total RLN paralysis; however, it has increased the rate of postoperative hypoparathyroidism. Neuromonitoring played a key role in the transition from partial thyroidectomy to total thyroidectomy surgery, while minimizing the rate of vocal fold paralysis. The myth of the 1% complication rate in thyroid surgery still remains and requires the implementation of new technologies to lower the risk of complications further.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request”.

References

Choroby tarczycy u Polaków. Statystyki, objawy, leczenie. http://zdrowie.wprost.pl/medycyna/choroby/10398657/choroby-tarczycy-u-polakow-statystyki-objawy-leczenie.html (accessed 15 Oct 2022).

Fortuny, J. V., Guigard, S., Karenovics, W. & Triponez, F. Surgery of the thyroid: recent developments and perspective. Swiss. Med. Wkly. 145, 14144. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2015.14144 (2015).

Terris, D. J. et al. Incisions in thyroid and parathyroid surgery. In Surgery and Parathyroid Surgery, 2nd ed. 403–406 (SAUNDERS, 2013).

Halsted, W. S. The operative story of goitre. The Author’s operation. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 74, 693–694 (1920).

Mitrecic, M. Z. et al. History of thyroid and parathyroid surgery. In Surgery of the Thyroid and Parathyroid Glands, 3–14 (SAUNDERS, 2003).

Hannan, S. A. The magnificent seven: a history of modern thyroid surgery. Int. J. Surg. 4, 187–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2006.03.002 (2006).

Patel, N. & Scott-Coombes, D. Impact of surgical volume and surgical outcome assessing registers on the quality of thyroid surgery. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2019.101317 (2019).

Shedd, D. P. & Burget, G. C. Identification of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Arch. Surg. 92, 861–864. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1966.01320240049010 (1966).

Randolph, G. W. et al. Electrophysiologic recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring during thyroid and parathyroid surgery: international standards guideline statement. Laryngoscope 121. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.21119 (2011).

Barczyński, M. et al. External branch of the superior laryngeal nerve monitoring during thyroid and parathyroid surgery: International Neural Monitoring Study Group Standards Guideline Statement. Laryngoscope. 123. (2013).

Orloff, L. A. at al. American thyroid association statement on postoperative hypoparathyroidism: diagnosis, prevention, and management in adults. Thyroid. 28, 830–841. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2017.0309 (2018).

Barbieri, D. at al. The impact of near-infrared autofluorescence on postoperative hypoparathyroidism during total thyroidectomy: a case-control study. Endocrine. 79, 392–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-022-03222-5 (2023).

de Vries, L. H. et al. Outcomes of minimally invasive thyroid Surgery—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 12, 719397. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.719397 (2021).

Lee, C. R. & Chung, W. Y. Robotic surgery for thyroid disease. Minerva Chir. 70, 331–339 (2015).

Anuwong, A., Ketwong, K., Jitpratoom, P., Sasanakietkul, T. & Duh, Q. Y. Safety and outcomes of the transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach. JAMA Surg. 153, 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3366 (2018).

Wojciechowska, U. & Didkowska, J. Zachorowania i zgony na nowotwory złośliwe w Polsce. Krajowy Rejestr Nowotworów, Narodowy Instytut Onkologii im. Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy. http://onkologia.org.pl/raporty (accessed 23 Dec 2021).

Li, M., Dal Maso, L. & Vaccarella, S. Global trends in thyroid cancer incidence and the impact of overdiagnosis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 8, 468–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30115-7 (2020).

Vaccarella, S., Franceschi, S., Bray, F., Wild, C. P. & Plummer, M. Dal Maso, L. Worldwide Thyroid-Cancer epidemic?? The increasing impact of overdiagnosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 614–617 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1604412.

Kahaly, G. J. Management of graves thyroidal and extrathyroidal disease: an update. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105, 3704–3720. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa646 (2020).

Patel, K. N. at al 3rd; et al. The American association of endocrine surgeons guidelines for the definitive surgical management of thyroid disease in adults. Ann. Surg. 271, e21–e93. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003580 (2020).

Papini, E., Monpeyssen, H., Frasoldati, A. & Hegedüs, L. European thyroid association clinical practice guideline for the use of image-guided ablation in benign thyroid nodules. Eur. Thyroid J. 9, 72–185. https://doi.org/10.1159/000508484 (2020).

Cherenfant, J. at al. Trends in thyroid surgery in Illinois. Surgery. 154, 1016–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2013.04.055 (2013).

Al-Qurayshi, Z., Robins, R., Hauch, A., Randolph, G. W. & Kandil, E. Association of surgeon volume with outcomes and cost savings following thyroidectomy: A National forecast. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 142, 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2015.2503 (2016).

Gourin, C. G. et al. Volume-based trends in thyroid surgery. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 136, 1191–1198 (2010).

van Gerwen, M., Alsen, M., Alpert, N., Sinclair, C. & Taioli, E. Trends for in- and outpatient thyroid cancer surgery in older adults in New York State, 2007–2017. J. Surg. Res. 273, 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2021.12.008 (2022).

Chandrasekhar, S. S. et al. Clinical practice guideline: improving voice outcomes after thyroid surgery. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 148, 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599813487301 (2013).

Jeannon, J. P., Orabi, A. A., Bruch, G. A., Abdalsalam, H. A. & Simo, R. Diagnosis of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy after thyroidectomy: A systematic review. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 63, 624–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01875.x (2009).

Główny Urząd Statystyczny. Stan zdrowia ludności Polski w 2019 r. http://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/zdrowie/zdrowie/stan-zdrowia-ludnosci-polski-w-2019-r-,26,1.html (accessed 12 Dec 2021).

Miranda-Filho; at al. Thyroid cancer incidence trends by histology in 25 countries: a population-based study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 9, 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00027-9 (2021).

Roman, B. R., Morris, L. G. & Davies, L. The thyroid cancer epidemic, 2017 perspective. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 24, 332–336. https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0000000000000359 (2017).

Seib, C. D. & Sosa, J. A. Evolving understanding of the epidemiology of thyroid cancer. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 48, 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2018.10.002 (2019).

Zaridze, D., Maximovitch, D., Smans, M. & Stilidi, I. Thyroid cancer overdiagnosis revisited. Cancer Epidemiol. 74, 102014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2021.102014 (2021).

Mulita, F. et al. Patient outcomes following surgical management of thyroid nodules classified as Bethesda category III (AUS/FLUS). Endokrynol. Pol. 72 (2), 143–144. https://doi.org/10.5603/EP.a2021.0018 (2021).

Subekti, I. & Pramono, L. A. Current diagnosis and management of graves’ disease. Acta Med. Indones. 50, 177–182 (2018).

Wiersinga, W. M., Poppe, K. G. & Effraimidis, G. Hyperthyroidism: aetiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, management, complications, and prognosis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 11, 282–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(23)00005-0 (2023).

Gan, T. & Randle, R. W. The role of surgery in autoimmune conditions of the thyroid. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 99, 633–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2019.04.005 (2019).

Inversini, D. at al. Thyroidectomy in elderly patients aged ≥ 70 years. Gland Surg. 6, 587–590. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs.2017.10.01 (2017).

Canu, G. L. at al. Can thyroidectomy be considered safe in obese patients? A retrospective cohort study. BMC Surg. 20, 275. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-00939-w (2020).

Jatzko, G. R., Lisborg, P. H., Muller, M. G. & Vette, V. M. Recurrent nerve palsy after thyroid operations-principal nerve identification and a literature review. Surgery. 115, 139–144 (1994).

Colak, T., Akca, T., Kanik, A., Yapici, D. & Aydin, S. Total versus subtotal thyroidectomy for the management of benign multinodular goiter in an endemic region. ANZ J. Surg. 74, 974–978. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.03139.x (2004).

Robert, J. et.al. Short- and long-term results of total vs subtotal thyroidectomies in the surgical treatment of graves’ disease. Swiss Surg. 7, 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1024/1023-9332.7.1.20 (2001).

Tezelman, S., Borucu, I., Senyurek Giles, Y., Tunca, F. & Terzioglu, T. The change in surgical practice from subtotal to near-total or total thyroidectomy in the treatment of patients with benign multinodular goiter. World J. Surg. 33, 400–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-008-9808-1 (2009).

Wojtczak, B., Kaliszewski, K., Sutkowski, K., Głód, M. & Barczyński, M. The learning curve for intraoperative neuromonitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerve in thyroid surgery. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 402, 701–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-016-1438-8 (2017).

Wojtczak, B., Kaliszewski, K., Sutkowski, K., Głód, M. & Barczyński, M. Evaluating the introduction of intraoperative neuromonitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerve in thyroid and parathyroid surgery. Arch. Med. Sci. 14, 321–328. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2016.63003 (2018).

Wojtczak, B., Kaliszewski, K., Sutkowski, K., Bolanowski, M. & Barczyński, M. A functional assessment of anatomical variants of the recurrent laryngeal nerve during thyroidectomies using neuromonitoring. Endocrine. 59, 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-017-1466-3 (2018).

Edafe, O., Cochrane, E. & Balasubramanian, S. P. Reoperation for bleeding after thyroid and parathyroid surgery: incidence, risk factors, prevention, and management. World J. Surg. 44, 1156–1162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-019-05322-2 (2020).

Miccoli, P., Frustaci, G., Fosso, A., Miccoli, M. & Materazzi, G. Surgery for recurrent goiter: complication rate and role of the thyroid-stimulating hormone-suppressive therapy after the first operation. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 400, 253–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-014-1258-7 (2015).

Wojtczak, B. & Barczyński, M. Intermittent neural monitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerve in surgery for recurrent goiter. Gland Surg. 5, 481–489. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs.2016.09.07 (2016).

Głód, M. at al. Analysis of risk factors for phonation disorders after thyroid surgery. Biomedicines. 10, 2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10092280 (2022).

Chou, R. at al. Active surveillance versus thyroid surgery for differentiated thyroid cancer: a systematic review. Thyroid. 32, 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2021.0539 (2022).

Tufano, R. P. et al. Update of radiofrequency ablation for treating benign and malignant thyroid nodules. The future is now. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 12, 698689. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.698689 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.W. wrote the main text and made conception, design, M.S. data acquisition; B.W. interpretation of data; B.W., K.S., D.M., K.K. analysis, data acquisition. All authors (B.W., M.S., K.S., D.M., K.K.) took part in drafting the article and revising it for important intellectual content. We agreed to submit it to the current journal. We also gave final approval of the version to be published and decided to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Bioethics Committee of Wroclaw Medical University, Wroclaw, Poland (Signature number: KB-280/2020; May 13, 2020).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Data Availability Statement: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wojtczak, B., Sępek, M., Sutkowski, K. et al. Changes in thyroid surgery over last 25 years. Sci Rep 15, 14432 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99191-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99191-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Is hemithyroidectomy enough? Low risk of occult contralateral disease in sporadic medullary thyroid cancer

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology (2025)