Abstract

Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is mainly caused by enteroviruses (EVs) and represents an important public health problem in China. The aim of this study was to investigate the epidemiological and genetic characteristics of EVs associated with HFMD in Jiaxing City in 2019–2022. In total, 1807 clinical specimens collected from patients with HFMD were evaluated by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, and 1553 EV-positive specimens were detected, including 1018 coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6), 301 coxsackievirus A16 (CVA16), 94 coxsackievirus A10 (CVA10), 7 enterovirus A71 (EV-A71), and 133 other EVs. A phylogenetic analysis revealed that the subgenogroups CVA6 D3a, CVA10 F, and CVA16 B1a B1b were predominant in Jiaxing. Compared with VP1 of the prototype strains of CVA6, CVA10, and CVA16, 34, 36, and 31 amino acid substitutions were detected, respectively. Children aged 1–5 years accounted for the majority of cases, and the infection rate was higher in males than in females. EV infection cases were clearly affected by the COVID-19 epidemic, with decreases in 2020 corresponding to the implementation of protective measures. These findings add to the global genetic resources for EVs and demonstrate the epidemiological characteristics and genetic features of HFMD in Jiaxing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is a common, highly contagious pediatric viral infection, predominantly affecting infants and children under 5 years of age1,2. More than 20 types of enteroviruses (EVs) cause HFMD, including coxsackievirus (CV) A2–A8, CVA10, CVA16, and enterovirus A71 (EV-A71)3,4,5. EVs can be divided into four species (A–D). Most HFMD cases are caused by EV-A6. HFMD is usually a benign, self-limiting disease; however, a small number of patients develop serious neurological, respiratory, or circulatory complications, which can lead to death7,8. HFMD is transmitted by the fecal-oral route or through direct or indirect contact with secretions from the nose and throat. The main pathogen causing HFMD in the past was EV-A719. However, recent national surveillance has revealed changes in the pathogens causing HFMD. The incidences of HFMD caused by CVA6, CVA10, and CVA16 have been increasing in China and worldwide.

Human EV is a nonenveloped single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus with a total genome length of approximately 7.4 kb, which encodes four structural proteins (VP1–VP4)10. The VP1 protein is an important target site for the main viral capsid protein and neutralizing antibodies, which can directly influence the antigenicity of the virus11. The VP1 genotype corresponds to the virus serotype; the gene is highly evolutionarily conserved and is an important marker for genotyping and genetic evolutionary analyses of viruses3,12,13.

Jiaxing City consists of two districts (Nanhu and Xiuzhou) and five counties (Haining, Tongxiang, Pinghu, Jiashan, and Haiyan). The population was 5.5 million in year. It is located in the core urban agglomeration of Yangtze River Delta within 100 km of Shanghai, Hangzhou, and Suzhou, with very convenient transportation and substantial personnel exchange. Surveillance of the epidemiological characteristics of HFMD in this region is of great significance for disease control and prevention.

In this study, samples from children with HFMD in Jiaxing in 2019–2022 were analyzed based on VP1 gene sequences to evaluate the causal pathogens and to clarify the epidemiological and genetic characteristics of HFMD in the region.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Samples were obtained from suspected HFMD cases in five counties and two districts under the jurisdiction of Jiaxing City. A total of 1807 samples from patients were collected between 2019 and 2022, including 1002 fecal samples and 805 throat swab samples. Among these, 406 samples were collected in 2019, 391 samples in 2020, 585 samples in 2021, and 425 samples in 2022. In most cases, the symptoms were mild, including fever, rash, stomatitis, oral herpes, oral ulcer, nausea, vomiting, cough, and runny nose. A small proportion of patients had body temperatures as high as 40 °C, lasting up to 3 days. Samples were collected in special virus sampling tubes and delivered to the laboratory for storage in a -70 °C refrigerator. Informed consent was obtained for sample collection.

Viral RNA extraction and identification of EVs

RNA extraction was performed using the Beijing Tiangen Nucleic Acid Extractor. Each sample was tested for nucleic acids using the EV/EV-A71/CVA16(cat. No SKY-8305) and CVA6/CVA10(cat. No SKY-8318 F) kits from Mabsky (Shenzhen, China) and CFX96™ Real-time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, USA). A 25 µL reaction system including 1 µL of enzyme mixture, 19 µL of reaction solution, and 5 µL of viral nucleic acids was used. PCR cycling parameters were set up according to the manufacturer’s instructions as follows: 50 °C for 30 min and 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 55 °C for 40 s. A positive result was defined as a cycle threshold (Ct) value ≤ 37, and the positive control was defined as a Ct ≤ 35.

Selection of PCR-positive samples for complete VP1 sequencing

Sixty CVA6, 20 CVA10, and 20 CVA16 specimens were randomly selected according to years, and primers were synthesized for amplification of the VP1 gene. Primers were shown in Table 1, experimental system, and procedure were described in the study process performed by Nix WA and Oberste MS14. The PCR products were identified by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, and those with positive results were sent to BioGerm Medical Technology Co., Ltd. for sequencing. Results were compared with sequences in the GenBank database for EV typing. Sequences were searched using BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Bioinformatics analysis

The VP1 gene sequences obtained in this study were analyzed together with sequences of reference strains. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method with the Kimura 2-parameter model implemented in MEGA 6.0. Bootstrap analysis (1000 replicates) was used to evaluate branch support. The nucleotide and amino acid sequence identity were analyzed using DNASTAR 7.1 software. Amino acid substitutions were analyzed using MEGA 6.0.

Ethics statement

This study did not involve human participants or human experimentation. Only specimen (fecal samples and throat swab samples) collected from HFMD patients for public health purposes. Written informed consent for the use of their clinical samples was obtained from the parents of the children whose samples were analyzed. This study was approved by Jiaxing Center for Disease Control and Prevention, all experimental protocols were approved by Jiaxing Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and the methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Results

Epidemiological features of EVs in HFMD in Jiaxing from 2019 to 2022

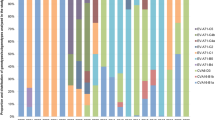

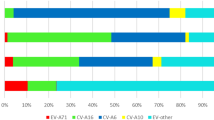

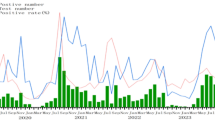

The number of hand, foot, and mouth disease cases remained relatively stable across each month in 2019. However, a notable decline was observed from February to June in 2020, followed by a sharp surge from August to October. The peak was detected in June 2021. HFMD cases declined from January to September 2022, but rebounded from October to December. EV-A71 was only detected in 2019. CVA6 was the most frequent subtype in each year. There was a noticeable increase in CVA10 from 2019 to 2021 but was not detected in 2022. CVA16 was detected each year, but decreased substantially in 2020. In 2019, the predominant types were mainly CVA16 (141/406, 34.7%) and CVA6 (165/406, 40.6%), with a small number of CVA10 (5/406, 1.2%), EV-A71 (7/406, 1.7%) types, and PE (positive for other enteroviruses except EV-A71, CVA16, CVA10, CVA6) (15/406, 3.6%) strains coexisting. By 2020, CVA6 (275/391, 70.3%) had become the most dominant type, with a small number of PE (30/391, 7.6%), CVA10 (18/391, 4.6%), and CVA16 (8/391, 2.0%) types also present. Entering 2021, CVA6 (302/585, 51.6%), CVA16 (91/585, 15.5%), CVA10 (71/585, 12.1%), and PE (78/585, 13.3%) all exhibited a certain degree of prevalence, indicating a relatively wide distribution of HFMD types that year. And by 2022, CVA6 (276/425, 64.9%) once again emerged as the most dominant type, followed by CVA16 (61/425, 14.3%), with a small number of PE (10/425, 2.3%) still present (Figs. 1 and 2).

During surveillance, we found no serious cases of HFMD in 2019, four hospitalizations in 2020, three hospitalizations in 2021, two hospitalizations in 2022, and no fatal cases. The incidence of HFMD was higher in males than in females for 4 consecutive years, with male-to-female ratios of 1.40:1 in 2019, 1.16:1 in 2020, 1.60:1 in 2021, and 1.43:1 in 2022. Of all cases, 75.4% were children aged 1–5 years, 18.1% were children aged 6–8 years, and 6.5% were children over 9 years old, Table 2.

Samples from 1807 suspected HFMD cases in 2019–2022 were obtained, revealing 1018 CVA6-positive cases (56.3%), 301 CVA16-positive cases (16.7%), 94 CVA10-positive cases (5.2%), 7 EV-A71-positive cases (0.4%), 133 positive for other enteroviruses (7.4%), and 254 negative samples (14.1%).

Nucleotide and amino acid similarity of VP1 of CVA6, CVA16, and CVA10

Full-length VP1 sequences of CVA6 (n = 53/60), CVA10 (n = 14/20), and CVA16 (n = 16/20) were obtained. After removing identical sequences for the same month of the same year, 67 strains were included in the analysis, including 45 CVA6, 9 CVA10, and 13 CVA16.

Nucleotide and amino acid sequence identity were analyzed using 45 CVA6 VP1 gene sequences obtained in this study and CVA6 prototype strain Gdula(AY421764.1, 2004). The VP1 gene was 915 bp and encoded 305 amino acids. The nucleotide and amino acid sequence identities of 45 CVA6 VP1 sequences were 92.79–100.0% and 97.38–100.0%, respectively. Compared with the prototype strain, the nucleotide and amino acid sequence identities were 81.97–83.61% and 94.43–96.39%, respectively. The nucleotide and amino acid similarities of samples across different years were also presented in Table 3. The VP1 gene of 13 CVA16 was 891 bp, encoding 297 amino acids, with 87.21–99.89% nucleotide similarity and 97.98–100% amino acid similarity. Compared with the prototype strain G-10 (U05876.1, 1994), the nucleotide and amino acid sequence identities were 74.75–76.09% and 91.25–92.26%, respectively, Table 4. The VP1 gene of nine CVA10 was 894 bp, encoding 298 amino acids. The nucleotide sequences of CVA10 strains shared 94.41–100% nucleotide identity and 95.3–100% amino acid identity. Comparisons with the prototype strain Kowalik(AF081300.1, 1999) showed 76.06–77.52% nucleotide identity, corresponding to 88.93–92.28% amino acid identity, Table 5.

Phylogenetic analysis of CVA6, CVA16, and CVA10 based on complete VP1 sequences

The 45 CVA6 strains obtained in our study and CVA6 reference strains available from GenBank were used for a phylogenetic analysis based on the complete VP1 gene sequences. The cladogram indicated that all CVA6 strains were divided into four genotypes, which were designated as A, B, C, and D. The D genotype was further divided into D1–3 sub-genotypes. Sub-genotype D3 was further subdivided into two lineages, designated as D3a and D3b. All 45 Jiaxing CVA6 strains in this study (collected in 2019–2022) belonged to D3a. CVA6 strains obtained in this study were closely related to the CVA6 stains isolated from other provinces and cities of China, such as Beijing(OL830029.1, 2019) and Yunnan(LC413180.1, 2017), which were assigned to the D3a lineage but formed distinct clusters (Fig. 3). These findings indicated that D3a was the predominant genotype in Jiaxing from 2019 to 2022 and co-circulated with other CVA6 of China, which belonged to different transmission chains.

A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on VP1 of 13 CVA-16 strains and CVA16 obtained from the GenBank database. All CVA16 strains found in Jiaxing belonged to the B1 subgenotype (Fig. 4). The 13 CVA16 strains were divided into two clades, B1a (six strains) and B1b (seven strains). CVA16 strains obtained in this study were closely related to stains isolated from other provinces and cities of China, such as Nanjing(KP751580.1, 2011), Guangzhou(KJ865506.1, 2012), and Henan(KM260130.1, 2014). All CVA10 strains obtained in this study belonged to the F genotype based on the phylogenetic analyses and were closely related to the CVA10 stains isolated fromYunnan(MK814854.1, 2018; LC481439.1, 2018; LC556010.1, 2019) (Fig. 5).

VP1 deduced amino acid sequence analysis of CVA6, CVA16, and CVA10

For the CVA6 sequences, when compared with the prototype strain Gdula(AY421764.1, 2004), 34 amino acid substitutions were found, among which 11 substitutions were shared among all newly obtained strains. For the CVA10 sequences, when compared with the prototype strain Kowalik(AF081300.1, 1999), 36 amino acid substitutions were found, including 20 residues with substitutions in all newly obtained strains. For CVA16, when compared with the prototype strain G-10 (U05876.1, 1994), 31 amino acid substitutions were found, including 22 residues with substitutions in all newly obtained strains. See Tables in Supplementary material.

Discussion

HFMD is caused by a variety of EVs. Although specific immunity can be acquired after infection with certain EVs, there is a lack of cross-protection among different EV types12,15,16. Continuous molecular monitoring provides valuable data for understanding the circulation and evolutionary patterns of viruses. CVA6, CVA10, and CVA16 have been the leading causes of HFMD in Jiaxing, China in recent years; however, information on these strains is limited. In this study, we analyzed the epidemiological and genetic characteristics of HFMD in Jiaxing from 2019 to 2022 to provide a theoretical basis for disease prevention and control.

The CVA6 strain accounted for the largest proportion of HFMD cases, followed by CVA16 and CVA10. In 2020, cases decreased substantially from February to June. This could be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic; additional protective measures during this period (e.g., wearing masks, and reducing movement and aggregation) were effective for preventing HFMD infection. Cases increased dramatically from August to December, corresponding with the relaxation of epidemic prevention and control measures, including the reopening of schools. In 2021, cases were sporadic, with increases in May and June, similar to the pattern in 2019. The incidence of COVID-19 was low in 2021; therefore, the spread of HFMD was not influenced by prevention and control measures. Most cases were detected in June, probably because of seasonal factors, as children are more sensitive to the virus under extreme temperatures and wet conditions17,18. Strict control measures against COVID-19 in 2022 could explain the low number of HFMD cases February to September.

In this study, the prevalence of HFMD among children aged 1–5 years was above 75% in Jiaxing, indicating that children in this age range are at high risk of HFMD. The prevalence is higher in boys than in girls, probably because boys are more active and more frequently exposed to infectious agents (e.g., via more frequent touching of unclean toys and facilities).

The EV-A71 vaccine plays a crucial role in reducing the number of HFMD cases and the severity and mortality rates of EV-A71 infections9,18,19. Consistent with previous observations, we found a substantial decrease in the number of HFMD cases caused by EV-A71, with the virus disappearing during the COVID-19 pandemic. EV-A71 may have a lower mutation rate than those of CVA6, CVA16, and CVA1013,20. Low diversity in EV-A71 might reduce its fitness and transmissibility, explaining the decrease in the EV-A71 prevalence10,21.

HFMD-associated CVA6 subgenogroup D3 was first described following an outbreak in Finland in 2008, and was subsequent detected in other countries across Europe22,23,24,25. In this study, we found that the D3a lineage was the predominant virus in Jiaxing from 2019 to 2022. There was no evidence for other emerging subgenotypes. A phylogenetic tree based on full-length VP1 sequences revealed that the prevalent CVA6 strains in Jiaxing co-circulated and evolved with CVA6 strains isolated from other regions in China, and the strains in this study might have multiple transmission chains. China exhibits substantial variation in terrain and climate. Therefore, the transmission and duplication abilities of CVA6 differ across regions. The subgenotype D3a of CVA6 probably has stronger transmissibility, infectivity, and virulence, explaining its persistent widespread circulation.

CVA16 could be divided into two genotypes: A and B. Genotype B is divided into subgenotypes B1 and B2. The B1 subtype is further divided into two evolutionary branches: B1a and B1b11,21,26,27. In the past decade, B1a and B1b subtypes were the main CVA16 types involved in HFMD cases in mainland China, especially in the eastern region. In this study, the two subtypes B1a and B1b were both prevalent from 2019 to 2022. A phylogenetic analysis indicated that the B1a subtype is closely related to endemic strains in Guangzhou and Beijing. The B1b subtype was closely related to endemic strains in Nanjing, Guangzhou, and Henan. Therefore, CVA16 strains causing HFMD in Jiaxing were closely related to strains in other provinces and cities in China.

HFMD associated with CVA10 is more severe than that associated with other strains and more likely to cause serious nervous system diseases28, such as aseptic meningitis and viral meningitis, especially in younger children12,20,29; CVA10 is now the main cause of severe HFMD, in addition to EV-A714,19,28. Currently, preventive vaccines and specific therapeutic drugs are not available for CVA1030. Thus, more research on the genetic characteristics and evolution of CVA10 is required. The full-length VP1 sequences of nine CVA10 in this study revealed that they belonged to the F genotype. In mainland China, cocirculating genotype F strains have been the predominant CV-A10 strains, indicating that the nine CVA10 isolates are epidemic strains.

CVA6 is often associated with mild cases and outbreaks of HFMD10,15,24. Here, we detected nine novel amino acid substitutions in the VP1 region, not detected by Zhou et al.13 : R68H (n = 1/45, 2.2%), V71I (n = 2/45, 4.4%), V89I (n = 3/45, 6.7%), G95S (n = 1/45, 2.2%), L145M (n = 1/45, 2.2%), N241D (n = 1/45, 2.2%), V244I (n = 1/45, 2.2%), M267I (n = 2/45, 4.4%), and I278V (n = 1/45, 2.2%). Although the frequencies of these variants were low, continued monitoring is needed. Additionally, CVA6 samples from our study demonstrated higher rates of the amino acid substitution S97N in the VP1 region than those in previous reports. Zhou et al.13 found that 6.2% (n = 4/65) of samples contained the S97N substitution, compared with 33.3% (n = 15/45) of our CVA6 samples, and this could potentially be associated with major neutralizing/antigenicity epitopes.

Among 13 CVA16 samples, we detected five novel variants in the VP1 region compared with those reported by Zhou et al.13, A30S (n = 1/13, 7.7%), A50G (n = 1/13, 7.7%), T103A (n = 1/13, 7.7%), T164K (n = 6/13, 46.2%), and V251I (n = 6/13, 46.2%). In total, 46.2% of sequences contained the T164K and V251I mutations, requiring further attention.

Twenty-one high-frequency amino acid substitutions in CVA-10 strains in China were reported by Yao et al.30, including mutations at residues 13, 14, 16, 21, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 31, 33, 70, 78, 81, 107, 148, 153, 240, 261, 285, and 291 in the VP1 region. In this study, mutations were detected at 20 of these previously described variable sites, in addition to 16 novel variants in the VP1 region of CVA10: S22N (n = 1/9, 11.1%), R72K (n = 4/9, 44.4%), Q223L (n = 9/9, 100%), R239K (n = 1/9, 11.1%), R263S (n = 1/9, 11.1%), R266S (n = 1/9, 11.1%), Q268H (n = 1/9, 11.1%), N274I (n = 1/9, 11.1%), N277K (n = 1/9, 11.1%), D279V (n = 1/9, 11.1%), S280R (n = 1/9, 11.1%), K282T (n = 1/9, 11.1%), I283V (n = 9/9, 100%), T284V/A (n = 9/9, 100%), S286N (n = 1/9, 11.1%), and D289Y (n = 1/9, 11.1%). Four amino acid residues showed high mutation frequencies, sites 72, 223, 283, and 284. The above variants in the VP1 region of CVA6, CVA16, and CVA10 may contribute to future changes in virulence, antigenic properties, or genotype switches in circulating EVs in China.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides genetic data for multiple HFMD-associated EVs. CVA6 subgenogroup D3a, CVA16 subgenogroups B1a and B1b, and CVA10 subgenogroup F were the predominant EV lineages in Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province, China. Our phylogenetic analysis of the main serotypes of EVs causing HFMD adds to our knowledge about enteroviral evolution and circulation. However, further research on amino acid variation and its effects on virulence, antigenic shifts, and genotype switches in EVs is required.

Data availability

The nucleotide sequences generated in this study were submitted to GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) under accession numbers PP482040-PP482052 for CVA16, PP797300-PP797308 for CVA10, PQ082971-PQ083015 for CVA6.

References

Shi, C. et al. Epidemiological characteristics and influential factors of hand, foot, and mouth disease reinfection in Wuxi, China, 2008–2016. BMC Infect. Dis. 18, 472. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3385-1 (2018).

Tao, J. et al. Epidemiology of 45,616 suspect cases of hand, foot and mouth disease in Chongqing, China, 2011–2015. Sci. Rep. 7, 45630. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45630 (2017).

Liu, L. et al. Epidemiological characteristics and spatiotemporal analysis of hand-foot-mouth diseases from 2010 to 2019 in Zibo City, Shandong, China. BMC Public. Health. 21, 1640. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11665-0 (2021).

Lizasoain, A., Mir, D., Martinez, N. & Colina, R. Coxsackievirus A10 causing hand-foot-and-mouth disease in Uruguay. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 94, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.012 (2020).

Guo, W. P. et al. Fourteen types of co-circulating recombinant enterovirus were associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease in children from Wenzhou, China. J. Clin. Virol. 70, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2015.06.093 (2015).

Li, Y. et al. Emerging enteroviruses causing hand, foot and mouth disease, China, 2010–2016. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 24, 1902–1906. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2410.171953 (2018).

Wang, M. et al. Rapid detection of hand, foot and mouth disease enterovirus genotypes by multiplex PCR. J. Virol. Methods. 258, 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2018.05.005 (2018).

Jiao, K., Hu, W., Ren, C., Xu, Z. & Ma, W. Impacts of tropical cyclones and accompanying precipitation and wind velocity on childhood hand, foot and mouth disease in Guangdong Province, China. Environ. Res. 173, 262–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2019.03.041 (2019).

Niu, P. et al. Development of a highly sensitive real-time nested RT-PCR assay in a single closed tube for detection of enterovirus 71 in hand, foot, and mouth disease. Arch. Virol. 161, 3003–3010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-016-2985-6 (2016).

Xu, L. et al. Atomic structures of coxsackievirus A6 and its complex with a neutralizing antibody. Nat. Commun. 8, 505. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00477-9 (2017).

Xu, L. et al. Genetic characteristics of the P1 coding region of coxsackievirus A16 associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease in China. Mol. Biol. Rep. 45, 1947–1955. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-018-4345-y (2018).

Duan, S. et al. Pathogenic analysis of coxsackievirus A10 in rhesus macaques. Virol. Sin. 37, 610–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virs.2022.06.007 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. Genetic variation of multiple serotypes of enteroviruses associated with hand, foot and mouth disease in Southern China. Virol. Sin. 36, 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12250-020-00266-7 (2021).

Nix, W. A., Oberste, M. S. & Pallansch, M. A. Sensitive, seminested PCR amplification of VP1 sequences for direct identification of all enterovirus serotypes from original clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 2698–2704. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00542-06 (2006).

Anh, N. T. et al. Emerging coxsackievirus A6 causing hand, foot and mouth disease, Vietnam. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 24, 654–662. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2404.171298 (2018).

Gui, J. et al. Epidemiological characteristics and spatial-temporal clusters of hand, foot, and mouth disease in Zhejiang Province, China, 2008–2012. PLoS One. 10, e0139109. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139109 (2015).

Nguyen, H. X. et al. Temporal and Spatial analysis of hand, foot, and mouth disease in relation to climate factors: A study in the Mekong Delta region, Vietnam. Sci. Total Environ. 581–582, 766–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.006 (2017).

Liu, C. C., Chow, Y. H., Chong, P. & Klein, M. Prospect and challenges for the development of multivalent vaccines against hand, foot and mouth diseases. Vaccine 32, 6177–6182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.08.064 (2014).

Chen, M. et al. Severe hand, foot and mouth disease associated with coxsackievirus A10 infections in Xiamen, China in 2015. J. Clin. Virol. 93, 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2017.05.011 (2017).

Zhang, J. et al. Characterization of coxsackievirus A10 strains isolated from children with hand, foot, and mouth disease. J. Med. Virol. 94, 601–609. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27268 (2022).

Weng, Y. et al. Serotyping and genetic characterization of hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD)-Associated enteroviruses of No-EV71 and Non-CVA16 Circulating in Fujian, China, 2011–2015. Med. Sci. Monit. 23, 2508–2518. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.901364 (2017).

Zhang, M., Chen, X., Wang, W., Li, Q. & Xie, Z. Genetic characteristics of coxsackievirus A6 from children with hand, foot and mouth disease in Beijing, China, 2017–2019. Infect. Genet. Evol. 106, 105378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2022.105378 (2022).

Puenpa, J. et al. Evolutionary and genetic recombination analyses of coxsackievirus A6 variants associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreaks in Thailand between 2019 and 2022. Viruses. 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15010073 (2022).

Chen, M. et al. Six amino acids of VP1 switch along with pandemic of CVA6-associated HFMD in Guangxi, Southern China, 2010–2017. J. Infect. 78, 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2019.02.002 (2019).

Bian, L. et al. Coxsackievirus A6: a new emerging pathogen causing hand, foot and mouth disease outbreaks worldwide. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 13, 1061–1071. https://doi.org/10.1586/14787210.2015.1058156 (2015).

Sun, Z. et al. Epidemiology and genetic characteristics of coxsackievirus A16 associated with hand-foot-and-mouth disease in Yantai City, China in 2018–2021. Biosaf. Health. 5, 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bsheal.2023.05.001 (2023).

Guo, J. et al. Epidemiology of hand, foot, and mouth disease and the genetic characteristics of coxsackievirus A16 in Taiyuan, Shanxi, China from 2010 to 2021. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 1040414. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.1040414 (2022).

Bian, L. et al. Hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with coxsackievirus A10: more serious than it seems. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 17, 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/14787210.2019.1585242 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Epidemiology of hand, foot, and mouth disease and genetic evolutionary characteristics of coxsackievirus A10 in Taiyuan City, Shanxi Province from 2016 to 2020. Viruses. 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15030694 (2023).

Yao, X., Guan, S., Liu, X. & Jiang, R. Molecular epidemiological analysis of coxsackievirus A10 strains isolated in Mainland China from 2004 to 2016. Chin. J. Disease Control Prev. 21, 1111–1127 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by all colleagues of Jiaxing Center for Disease Control and Prevention. We thank Liwen Bianji (Edanz) (http://www.liwenbianji.cn) for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

Jiaxing Science and Technology Bureau project “Epidemiology and Genetic Characteristics of hand-foot-mouth disease in Jiaxing City in 2019–2022” (2023AD11049). Jiaxing Science and Technology Bureau project “Genetic characterization of hand-foot-mouth disease in Jiaxing city based on high-throughput sequencing technology” (2022AY30024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LV and ZHU conceived and designed the experiments. JI and ZHOU collected the experimental data. LV analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. YAN and ZHU contributed reagents, materials, and analytical tools. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lv, S., Zhou, Y., Ji, J. et al. Epidemiological and genetic characteristics of enteroviruses associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease in Jiaxing, China from 2019 to 2022. Sci Rep 15, 14546 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99251-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99251-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Temporal phylodynamics of Coxsackievirus A6 VP1 in Shenzhen (2022–2024)

BMC Infectious Diseases (2025)