Abstract

Metformin, a typical pharmaceutical and personal care product (PPCPs), has a significant role in protecting brain cognitive function and delaying multiple organs aging, as well as causes seriously endocrine and reproductive interference to aquatic organisms due to drug abuse. Graphene that is of stable structure, flexible connection between carbon atoms, and the conjugated large pi bonds has been used to wastewater treatment, while Graphene-based materials used to remove PPCPs are rarely reported. Therefore, two graphene oxide (GO) based materials, including silane coupling agent modified product (CTOS-mGO) and Pyracantha fortuneana proanthocyanidin extract reduced product (PFPA-rGO), were used for metformin removal from aqueous solution as well as revealed the mechanism in this adsorption process. The results showed that metformin could be quickly and effectively removed by GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO, of which the best material of adsorption effects was CTOS-mGO. The pseudo-second-order kinetic could effectively describe their adsorption process, and they achieved more than 80% removal rate within 15 to 20 min. Metformin adsorption by GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO were all spontaneous and exothermic. CTOS-mGO was of the largest adsorption capacity and recycling utilization for metformin removal in comparison with GO and PFPA-rGO. The optimal adsorption temperature and pH for the GO and CTOS-mGO, PFPA-rGO adsorbents were 293 K and pH 6.0, 293 K and pH 7.0, 303 K and pH 6.0, respectively. Our results suggested that the aromatic rings and the abundant oxygen-containing functional groups distributed on the surface of the sheets endowed them with the characteristics of π-electron acceptors or donors, and metformin with dissociative properties could serve as a stabilizer for this π–π interaction. In addition, the electrostatic interaction between the positively charged metformin and the negatively charged GO and CTOS-mGO were also important contributors to the adsorption reaction. Our results emphasized that the GO based materials might be an effective method for alleviating metformin and other PPCPs pollution, which also provided a reference for environmental remediation of similar pollutants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products (PPCPs), including various types of compounds such as pharmaceuticals and care products, can directly or indirectly enter the aqueous environment and pose a potential safety hazard to water resources through multiple pathways, such as the discharge of production wastewater and the excretion of humans and animals1. The sharp rise in the prevalence of type II diabetes, which is closely related to the sedentary lifestyle and high-fat and high-sugar diet in modern society has made metformin once again come into the public view, and because of its high efficiency and low cost characteristics, metformin plays a dominant role in regulating blood sugar levels and treating diabetes2. In addition, as a drug for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, the new physiological effects of metformin are also constantly being studied and developed, for example, the latest research has shown that metformin has obvious effects in protecting brain cognitive function and delaying multiple organ aging3. The harm of large-scale use, non-degradability in vivo, environmental release, biotransformation and bioaccumulation of metformin to the aquatic environment cannot be ignored, and the existing researches have confirmed that metformin and its transformation products have obvious endocrine and reproductive interference effects on aquatic organisms4,5. Thus, as one of the typical PPCP emerging pollutants with the highest abundance in sewage treatment plant effluent and surface water1, how metformin can be effectively removed from the aquatic environment needs to be solved urgently.

Compared with the methods of biodegradation, photodegradation, phytoremediation, oxidation and chlorination process, etc., the advantages of low cost, high recycling efficiency, green environmental protection, excellent adsorption performance and simple operation make the adsorption method become the first choice of water treatment technology2,5. Adsorbents such as biochar, exchange resin and nanotubes have been widely used in the removal of various types of pollutants6. As a graphene-based carbon material, graphene oxide (GO) has excellent specific surface area, outstanding adsorption performance, great biocompatibility, plentiful oxygen-containing groups, special structural characteristics and functional modification characteristics, which makes it show good application prospects in the field of adsorption7. For example, GO can effectively remove heavy metals, organic pollutants, drugs and other types of pollutants in aquatic environment under complex background interference1. Although Zhu et al.‘s research has pointed out that GO has an excellent removal effect on the emerging pollutant metformin1, and graphene-based materials have been proved to be the best adsorbent for metformin removal except for activated carbons prepared by Moringa oleifera seeds and chichá-do-cerrado in existing studies2, there are still few studies and data on how to reduce or eliminate metformin residues in water, and the application of graphene-based adsorbents to remove metformin from aquatic environment also needs to be further explored.

Based on the effective adsorption of metformin by GO, how to develop new graphene-based adsorbents to improve the removal efficiency of metformin in water and achieve the purpose of cost reduction and green environmental protection has become the focus of our attention. Among them, the modification effect of silane coupling agents and the reduction effect of natural extracts in the development of graphene-based adsorbents have aroused our strong interest. As a kind of organosilicon compound with special structure, low molecular weight and capping effect, silane coupling agents are often used in the surface modification of inorganic materials to improve the high temperature resistance, oxidation resistance, particle dispersion ability and mechanical properties of materials8. The existing researches have shown that the graphene oxide modified by silane coupling agent has better recovery and removal effect on phenolic compounds in water environment8,9. The structure of graphene is very stable, the connection between carbon atoms is extremely flexible, and the characteristics of conjugated large pi bonds, environmental friendliness, chemical and thermal stability, and excellent adsorption performance make it have good application prospects in removing water pollutants10. Existing studies have pointed out that reduced graphene oxide (rGO) has efficient removal effects on organic pollutants such as bisphenol A and inorganic pollutants such as lead in aquatic environments10,11,12. Compared with micromechanical exfoliation method and chemical vapor deposition method, the preparation of rGO by chemical reduction method using GO as raw material has obvious advantages in terms of cost and yield, but the reducing agent hydrazine or hydrazine hydrate commonly used in the reduction process is toxic and explosive10,11. Therefore, it is vital to explore a mild and effective method to achieve green preparation of rGO. Currently, plant extracts rich in polyphenols, polysaccharides, vitamins and other functional components that can act as reducing agents and capping agents have been successfully applied in the green preparation of rGO using GO as raw material, and these green prepared rGO have been proved to be effective adsorbents for removing various types of pollutants from aqueous solution11. However, the removal effect of GO modified by silane coupling agent and GO reduced by natural extract on metformin in water, as well as how experimental factors such as pH and temperature affect the removal of metformin by the two types of GO modified products and the possible mechanism have not been reported.

It has been proved that (3-chloropropyl)-trimethoxysilane can efficaciously ameliorate the physical and chemical properties of GO9. Plant proanthocyanidin extracts have also been proved to be able to effectively reduce GO13, and our previous studies have shown that the content of proanthocyanidins in mature Pyracantha fortuneana fruit is most abundant14. Therefore, in this study, GO was modified and reduced by (3-chloropropyl)-trimethoxysilane and Pyracantha fortuneana proanthocyanidin extract, respectively, and GO and its two forms of modified products were characterized accordingly. The effects of concentration, time, pH and temperature on the removal of metformin by GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO were investigated by batch adsorption experiments. The kinetics and thermodynamics of metformin adsorption on GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO were evaluated and compared, and the possible adsorption mechanism was proposed.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Metformin (> 98%) was provided by Wuhan Jingbiao Technology Co., Ltd., China. Graphite powder, potassium persulfate (K2S2O8), phosphorus pentoxide (P2O5), sodium nitrate (NaNO3), potassium permanganate (KMnO4) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were supplied by Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. Concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydrochloric acid (HCl) and ethanol absolute were purchased from Xinyang Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China. All the chemical reagents used in this study were of analytical grade and could be used without further purification. The fruits of Pyracantha fortuneana were harvested in Baiyun District, Guizhou Province, China, and the collected fruits were certified by literature and experts14. The preparation of the solutions and the construction of the systems all used Milli-Q water (Millipore, Bradford, USA).

Preparation of Pyracantha fortuneana extract

The proanthocyanidin extract of Pyracantha fortuneana was prepared by enzymatic hydrolysis coupled with organic solvent extraction, which referred to the researchs of Yang and Wu et al.15,16, and made appropriate modifications. Specifically, the initial extraction was carried out under the conditions of cellulase: pectinase of 2:5, enzyme addition of 1.5%, pH of 5.5, enzymolysis time of 80 min, enzymolysis temperature of 55 °C, and solid-liquid ratio of 1:19, and then the initial extraction product was vacuum freeze-dried. Then, the dried crude extract was used as raw material, and the organic solvent extraction was conducted under the conditions of solid-liquid ratio of 1:12, ethanol concentration of 73%, pH of 3.6, extraction temperature of 80 °C and extraction time of 60 min. After extraction, the extraction system was naturally cooled to room temperature, and the supernatant obtained by centrifugation at 12,000 r/min was filtered through a 0.45 μm filter to remove small particles. The filtrate, that was, the proanthocyanidin extract of Pyracantha fortuneana, was transferred to a clean reagent bottle and sealed and stored at 4 °C.

Preparation of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO

Referring to the research of Zhu et al., GO was prepared and obtained from graphite powder using an improved Hummers method1. The preparation of silane coupling agent modified graphene oxide referred to the researches of Kong and Wang et al.17,18, and made appropriate modifications. Specifically, an appropriate amount of (3-chloropropyl)-trimethoxysilane and GO were ultrasonically dispersed in 50 mL toluene, and then the above reaction system was stirred at 80 °C for 12 h. After the reaction completed, the suspension was cooled to room temperature, and the crude product was obtained after centrifugation at 12,000 r/min for 15 min. Subsequently, the crude product was washed sequentially with toluene, acetone and distilled water to remove the unreacted coupling agent. After freeze-drying for 42 h, the silane coupling agent modified adsorbent material (CTOS-mGO) was obtained and placed in a dry dark reagent bottle for later use. The preparation of green reduced graphene oxide referred to the researchs of Guo et al. and Lin et al.11,13, and made some modifications. 1.2 mg of GO was suspended in 30 mL deionized water and ultrasonically treated for 30 min to disperse evenly. Subsequently, 300 mL of proanthocyanidin extract of Pyracantha fortuneana was added to the dispersion, and in order to maintain the stability of proanthocyanidins, 3 mL of concentrated hydrochloric acid was added to the above system to construct an acidic environment. The reaction system was ultrasonically dispersed for 30 min and then stirred at 80 °C water bath for 3 h. The system cooled to room temperature was centrifuged at 12,000 r/min for 15 min to obtain the crude product. The crude product was washed three times with absolute alcohol and deionized water, respectively, and then freeze-dried for 48 h. Finally, the obtained adsorption material reduced by the proanthocyanidin extract of Pyracantha fortuneana was named PFPA-rGO and stored in a dry dark container for subsequent use.

Characterization of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO

The surface morphology and structure of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO were recorded by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, GeminiSEM 300, ZEISS, Germany), and the acceleration voltage during morphology shooting was 3 kV. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO in the wavelength range of 4000–400 cm− 1 was mediated by the Nicolet 6700 spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). The crystalline phase structures of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO were obtained by X-ray diffractometer (D8 Advance, Bruker, Germany) equipped with Cu target, and the test conditions included tube current and voltage of 40 mA and 40 KV, respectively. The application of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (K-Alpha, Thermo Scientific, USA) completed the analysis of the surface element composition of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO, and under the premise of locking the excitation source (Al Kα ray, hv = 1486.6 eV), the spot size, operating voltage and filament current were required to be 400 μm, 12 kV and 6 mA, respectively. The structural composition analysis of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO was mediated by Raman spectroscopy (LabRam HR Evolution, Horiba Scientific, USA).

Batch adsorption experiments

To compare the adsorption capacity and characteristics of these three adsorption materials for metformin, the batch adsorption experiments of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO were carried out under the conditions of constant temperature and stirring (120 rpm, 303 K). The adsorption system consisted of 25 mL of metformin solution and 5 mg of adsorption material, and the adsorption time was 120 min. The adsorption system was adjusted to the required pH by HCl or 0.5 M NaOH solution. After adsorption, the solid phase and liquid phase were separated by 0.45 μm filter membrane to obtain the supernatant1,11. The effects of adsorption conditions on the adsorption capacity of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO for metformin were studied. The isotherm adsorption experiments were completed under the conditions of linear temperature gradients (283, 293, 303, 313 K), different initial concentrations (10, 20, 30, 40, 50 mg/L), pH 6, and reaction time 120 min, and other parameter settings remained unchanged. The kinetic experiments were completed at 293 K (for GO and CTOS-mGO) or 303 K (for PFPA-rGO), pH 6.0 and 120 min in a reaction system consisting of 5 mg adsorbent and 25 mL of 20 mg/mL metformin solution, and on the premise of ensuring other parameters unchanged, the supernatant was collected at every pre-set time point to estimate the uptake of metformin. The effects of pH on the adsorption properties of the three adsorbents were studied under the linear pH gradient of 4–9, and the setting of other parameters was consistent with the above experiments.

The determination of metformin residue in the adsorption system was completed by an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (UV-3600Plus, SHIMADZU, Japan), and the determination wavelength was selected as 232 nm1,19. The adsorption capacity of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO for metformin at the specific time was calculated according to the following formula, among which, qe, C0, Ce, V and m referred to the adsorption quantity (mg/g), the initial and equilibrium concentrations of metformin in the solution (mg/L), the volume of the solution (L) and the amount of adsorbent (mg), respectively.

Desorption experiment

To evaluate the comprehensive performance of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO from the perspective of adsorbent reusability, 0.2 M NaOH was used as desorption medium to mediate desorption in this study. GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO adsorbed with metformin were repeatedly washed with ultrapure water after being desorbed by NaOH solution, and then recycled after freeze-drying for reuse.

Results and discussion

Characterization

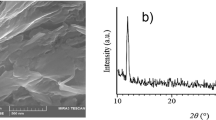

SEM

The SEM images of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO at different magnifications were shown in Fig. 1A–C, respectively. Obviously, there are significant differences in the appearance and morphology of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO. For GO, the occurrence form of lamellar structure and the presence of many wrinkles on the surface were helpful to increase its specific surface area and improve its adsorption capacity. After functionalized by silane coupling agent, the morphology of CTOS-mGO sheets changed subtly, and the increase of roughness and wrinkles showed that (3-chloropropyl)-trimethoxysilane had a good effect on GO modification. The crepe-like surface wrinkle was the characteristic microstructure of PFPA-rGO, a product modified by proanthocyanidin extract of Pyracantha fortuneana. In addition, GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO had different degrees of stacking, which might be attributed to the role of van der Waals force in the material preparation process11,20.

FTIR

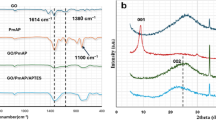

Figure 2 presented the FTIR spectras of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO. The wide and strong peaks at 3430 cm− 1 represented the stretching vibration of O–H, the small and narrow peaks at 2812 cm− 1 and 2727 cm− 1 represented the stretching vibration of aldehyde C–H, the strong and broad peaks at 1594 cm− 1 represented the antisymmetric stretching vibration of carboxylate COO- or the stretching vibration of aldehyde C = O11,21. The peaks at 1384 cm− 1 and 1350 cm− 1 represented the in-plane bending vibration of aldehyde C-H bonds and the symmetric stretching vibration of carboxylate (COO–) groups, respectively22. The peaks at 1117 cm− 1, 765 cm− 1 and 618 cm− 1 referred to the stretching vibration of hydroxyl C–OH, the angular vibration of carboxylate COO- and the out-of-plane bending vibration of hydroxyl C–O–H, respectively23,24. The above information indicates that there were many oxygen-containing groups in GO sheets, such as hydroxyl, carboxyl, epoxy, etc. The Si–O stretching vibration peak of organosilicon compound or the hydroxyl C-OH stretching vibration peak was at the wavelength of 1110 cm− 1, and the Si–C stretching vibration peak of organosilicon compounds was at the wavelength of 697 cm− 1 (a newly emerged peak)25,26. This proved that silane coupling agent (3-chloropropyl)-trimethoxysilane was grafted with GO, but due to the different structures of different silane coupling agents, the positions of the characteristic peaks measured were also slightly different18. The decrease in relative intensity of COO- related vibration peaks and the increase in relative intensity of C = C related peak (1631 cm− 1) were the key features of PFPA-rGO, which proved that GO has been successfully reduced by the proanthocyanidin extract of Pyracantha fortuneana27.

XRD

As shown in Fig. 3, the internal structures of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO were also analyzed by XRD. The strong and sharp diffraction peak of GO at 2θ = 10.02° was consist with the typical diffraction peak of GO (Fig. 3A), and indicated that the GO sample prepared in this study had a highly ordered structure18. There was no obvious sharp diffraction peak on the XRD pattern of silane coupling agent modified graphene oxide (CTOS-mGO) (Fig. 3B), which indicated that the GO sheets were exfoliated and the functionalized GO sheets were loosely stacked18. In fact, the silane part has destroyed the periodic structure of GO and effectively reduced the aggregation of graphene layers. For CTOS-mGO, the low-intensity broad peak at 2θ ≈ 20.63° might be the result of the interaction between some silanes and oxygen-containing functional groups28,29. The increase in the interlayer spacing indicated that the silane molecules and alkyl chains have been successfully grafted onto the surface of the GO sheets. However, the silane coupling agent could not always be inserted between the graphite oxide sheets, because the alkoxy groups in the molecules could also be hydrolyzed and condensed, which would make GO connected from different directions to form a messy structure, resulting in a wider diffraction peak of CTOS-mGO, but disordered30. The broad characteristic diffraction peak of PFPA-rGO was located at 2θ = 22.50° (Fig. 3C), which was consistent with the diffraction characteristics of rGO that restored the conjugated structure, and the relevant informations proved again that GO was successfully reduced by the proanthocyanidin extract of Pyracantha fortuneana11,31,32. The decrease of the peak value could be explained by the increase of the distance between atoms, which indicated that the distance between adjacent layers of PFPA-rGO was also farther than that of GO1,33,34.

XPS

The elemental composition and characteristic functional groups of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO were obtained by XPS analysis, as shown in Fig. 4. The characteristic peaks at 285 eV and 533 eV in the XPS full spectrum referred to the C and O elements in GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO, respectively (Fig. 4A)35. The C 1s and O 1s XPS spectra of GO were presented in Fig. 4B, C. Specifically, the four different peaks at 284.8 eV, 286.8 eV, 287.8 eV and 288.8 eV in the C 1s spectrum corresponded to C–C, C–O, C = O and O-C = O, respectively, and the three peaks at 529.1 eV, 533.0 eV and 533.9 eV in the O 1s spectrum corresponded to C–O, C = O and O-C = O, respectively, indicating that GO has been successfully oxidized by oxidation reaction36. Obviously, C-O and C = O accounted for the largest proportion of oxygen-containing functional groups in GO, and these functional groups were expected to form a strong binding with metformin on the surface of GO sheets during the adsorption process1. Compared with GO, the intensity of C 1s peak in the XPS spectrum of CTOS-mGO was significantly enhanced, while the intensity of O 1s peak was significantly weakened, which might be due to the partial reduction of oxygen-containing functional groups caused by the grafting of silane coupling agents17. In the XRD characterization result of CTOS-mGO, the disappearance of the diffraction peak at 2θ = 10.02° and the appearance of the diffraction peak with a relatively wide diffraction range but relatively weak diffraction intensity at 2θ ≈ 20.63° after modification with silane coupling agent confirmed the same conclusion (Figs. 3 and 4). In addition, after modification with silane coupling agent, new absorption peaks appeared in the C 1s and O 1s spectra of the obtained adsorbent CTOS-mGO (Fig. 4D, E), including C-O–Si (286.58 eV), C–Cl (285.98 eV), C–Si (283.38 eV) and C–O–Si (531.58 eV), which also indicated that the silane coupling agent had been successfully grafted onto GO. As shown in Fig. 4F, based on Gaussian simulation, the C 1s spectrum of PFPA-rGO had five characteristic peaks at 290.08 eV, 288.38 eV, 285.98 eV, 284.78 and 284.18, corresponding to O–C = O, C = O, C–O, C–C and C = C of rGO, respectively11,37. The O 1s spectrum of PFPA-rGO contained three peaks that located at 533.88 eV, 532.98 eV and 532.08 eV, respectively, which was attributed to the O of O–C = O, C = O and C–O in rGO37,38. In addition, the characteristic peaks of C = O and C-O bonds might also be related to the biomolecules of Pyracantha fortuneana extract wrapped on the surface of reduced graphene oxide11,39.

Raman spectroscopy

The Raman spectra reflected the defect and disorder level of the three graphene-based materials (GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO). As shown in Fig. 5, the vibration at 1342 cm− 1 (D peak) was attributed to the structural defects of graphene, while the vibration at 1566 cm− 1 (G peak) was related to the sp2 carbon hybrid structure of graphene-based materials37. The intensity ratios of D peak to G peak (ID/IG) of CTOS-mGO and GO were 1.26 and 1.16, respectively. The increase of ID/IG ratio implied a decrease in the proportion of sp2 hybrid carbon atoms and an increase in defect degree in the CTOS-mGO structure modified with silane coupling agent17. Compared with GO, the ID/IG ratio of PFPA-rGO increased to 1.40, which was enough to indicate that the treatment of Pyracantha fortuneana proanthocyanidin extract reduced the oxygen-containing functional groups during the transformation of GO to PFPA-rGO11,39.

Adsorption kinetics

It was known that the reaction time was a key parameter in the adsorption experiment, which determined the contact time of the solid-liquid interface during adsorption11. Therefore, the adsorption reaction kinetics was carried out in this study to evaluate and compare the optimal reaction time of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO for the adsorption of metformin. Figure 6 showed the time-dependent characteristics of the adsorption of metformin on GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO. When the removal rate of metformin in water by the three adsorbents reached about 80%, the time required was 15, 20 and 15 min, respectively. Due to the sufficient functional groups and adsorption sites on the surface of the adsorbents and the lack of internal diffusion resistance during this period, this period was a rapid adsorption process40. Obviously, in this rapid adsorption stage, the removal rate of metformin by GO prepared in this study was better than that of Zhu et al.1, and the adsorption rate of metformin by CTOS-mGO was significantly slower than that of GO and PFPA-rGO. In addition, when the reaction time reached 120 min, the adsorption of metformin by the three adsorbents all basically reached dynamic equilibrium.

To gain insight into the adsorption mechanism of metformin on GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO, the relevant datas were substituted into the pseudo-first-order kinetic model (formula 2) and the pseudo-second-order kinetic model (formula 3) for fitting1, and the fitting results were displayed in Fig. 6 and Table 1.

Among them, k1 and k2 referred to pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order rate constant, respectively; qt and qe referred to the adsorption amount (mg/g) of metformin by GO, CTOS-mGO or PFPA-rGO at t time and equilibrium time, respectively; the correlation coefficient (R2) was used to evaluate the consistency of experimental data in the kinetic model.

As shown in Fig. 6, for the three adsorbents of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO, the curves of the two kinetic models coincided with the kinetic adsorption data of metformin, and the obtained fitting parameters were presented in Table 1 in detail. The R2 of the pseudo-first-order model of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO were 0.866, 0.870 and 0.968, respectively, while the R2 of the pseudo-second-order model were 0.998, 0.997 and 0.995, respectively. Obviously, the pseudo-second-order models of the three adsorbents all presented better correlation coefficients than that of the pseudo-first-order models. Based on this information, it could be concluded that chemical adsorption was the rate-controlling step for the adsorption of metformin by these three adsorbents11,41. Moreover, compared with the qe value of the pseudo-first-order model, the qe value obtained by the pseudo-second-order model (69.444 mg/g for GO, 84.034 mg/g for CTOS-mGO, 64.516 mg/g for PFPA-rGO) was more consistent with the experimental data42. This result once again proved that GO had excellent adsorption performance for metformin1, and the adsorption capacity of CTOS-mGO modified by silane coupling agent for metformin was significantly improved, but the adsorption capacity of PFPA-rGO reduced by proanthocyanidin extract of Pyracantha fortuneana for metformin was not effectively improved. Furthermore, the smaller the k2, the lower the reaction rate, and the lower the removal efficiency11. Therefore, the k2 values of GO (0.004), CTOS-mGO (0.002) and PFPA-rGO (0.003) could not only confirm that the adsorption of metformin by the three adsorbents was a rate-controlled process, but also confirm that the adsorption rate of CTOS-mGO was slower than that of GO and PFPA-rGO.

Adsorption isotherms

In this study, batch adsorption isotherm experiments were performed on the adsorption behavior of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO at different temperatures (283 K, 293 K, 303 K, 313 K) at the solid-liquid interface when the adsorbate metformin reached adsorption equilibrium, and the relevant results were shown in Fig. 7; Table 2. Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models were often used to describe the isothermal properties of adsorption at the solid-liquid interface, thus, these two typical isotherm models were taken to study the adsorption characteristics of the three adsorbents GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO43. The Langmuir isotherm model depended on several basic assumptions, including uniform solid surface, monolayer adsorption, no interaction between adsorption sites and dynamic adsorption equilibrium, while the basic assumptions of Freundlich isotherm model included non-uniform heat distribution, uneven surface adsorption and multi-layer adsorption43,44. The Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm model Eqs. (4) and (5) used in this study were presented as follows1,11,45:

Among them, Ce and qe referred to the concentration of metformin in the solution (mg/L) and the adsorption capacity of metformin per unit mass of adsorbent (mg/g) at the time of adsorption equilibrium, respectively; qmax and KL referred to the theoretical saturated adsorption capacity of monolayer adsorption (mg/g) and the Langmuir constant (L/mg) related to the affinity of adsorption sites, respectively; KF and n referred to the Freundlich constant (L/mg) related to the adsorption capacity and the Freundlich constant related to the adsorption strength, respectively. When n was between 1 and 10, the adsorption process was favorable and the adsorption capacity increased11,46.

Table 2 showed the relevant parameters obtained from the above two typical isothermal models. Obviously, the larger R2 value indicated that the adsorption behavior of metformin on GO was more consistent with the Freundlich model, which was consistent with the research of Zhu et al.1. For CTOS-mGO, the correlation coefficient R2 at four temperatures fitted by Freundlich isotherm model was also higher than that of the Langmuir model, indicating that the Freundlich isotherm model had a higher fitting degree for the experimental data of CFOS-mGO group, that was, the adsorption behavior of metformin on CFOS-mGO was also conformed to the Freundlich isotherm model47. The relevant informations also confirmed that the surface of the two adsorbents GO and CFOS-mGO was uneven, the adsorption process was a multi-molecular layer adsorption that occurred on the heterogeneous surface, and the adsorbent binding sites was unsaturated1,47. The high KF values of GO and CFOS-mGO represented a strong adsorption capacity and high affinity for metformin, and CFOS-mGO was superior in comparison with GO48, which corresponded to the kinetic data. Contrary to GO and CTOS-mGO, the experimental data of PFPA-rGO group were more consistent with the Langmuir isotherm model, suggesting that the adsorption of metformin by PFPA-rGO seemed to be a uniform monolayer adsorption on the surface of PFPA-rGO, and all adsorption sites were the same, which might be attributed to the interaction of π-π bonds on PFPA-rGO49. In addition, the constants n of the Freundlich model of GO group and CTOS-mGO group at four temperatures were 5.444, 6.414, 5.325, 4.985 and 5.559, 6.645, 5.447, 5.128, respectively, which meant that under the selected four temperature conditions, GO and CTOS-mGO had a good adsorption effect on metformin, and CTOS-mGO was superior to GO11,46. Based on the fitting results of the two isothermal models, GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO all showed excellent adsorption performance for metformin, especially CTOS-mGO, and the effect of temperature on the adsorption performance of the three adsorbents was obvious, higher or lower temperature was not conducive to the occurrence of adsorption reaction at the solid-liquid Interface.

Adsorption thermodynamics

The thermodynamic parameters including ΔG0, ΔS0 and ΔH0 were analyzed according to the adsorption of metformin on GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO at different temperatures (Table 3), and the formulas (6, 7 and 8) used were presented as follows50,51:

Among them, ΔS0, ΔH0 and ΔG0 referred to the standard entropy change (kJ/mol·K), standard enthalpy change (kJ/mol·K) and standard free energy change (kJ/mol), respectively; ΔS0 and ΔH0 could be acquired from the intercept and slope of the diagram of the relationship between lnK0 and 1/T; T and R referred to temperature (K) and gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K), respectively.

The negative values of the standard free energy change (ΔG0) and standard enthalpy change (ΔH0) at all temperatures represented that the adsorption of metformin on GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO was all spontaneous and exothermic1. This result corresponded to the Freundlich and Langmuir isotherm fitting results, that was, higher temperature was not conducive to the occurrence of adsorption reaction, especially for GO and CTOS-mGO. At the same temperature, the ΔG0 and ΔH0 values of PFPA-rGO were higher than those of GO and CTOS-mGO, which made the optimal adsorption temperature of metformin on PFPA-rGO higher than that of GO and CTOS-mGO11. This result was also reflected in the Langmuir isotherm fitting results. Additionally, the positive standard entropy changes (ΔS0) implied that the randomness at the metformin-CTOS-mGO or metformin-PFPA-rGO interface increased during the adsorption process52. In contrast, the ΔS0 of GO existed in the form of a negative number, which indicated that the disorder degree of GO surface decreased during the adsorption process52.

Effect of initial solution pH

The pH value of adsorption system is an important index affecting the adsorption process of the adsorbate11. Figure 8A showed the sensitivity of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO to pH value in the adsorption process of metformin. It was observed that in the pH range of 4.0 to 9.0, the uptake of metformin by the three adsorbents showed a trend of increasing first and then decreasing. Among them, the adsorption amount of GO and PFPA-rGO reached the maximum at pH = 6, while CTOS-mGO had the highest adsorption amount at pH = 7. The change of the surface charge of the three adsorbents and the speciation of the adsorbate under different pH conditions might be used to explain this phenomenon1,11. For adsorbates, the monoprotonated form of metformin might increase with the increase of pH in the acidic range and decrease with the increase of pH in the alkaline range1. Thus, the amount of the monoprotonated form determined by the dissociation state of the adsorbate at different pH values led to a decrease in electron acceptability of metformin at higher pH. In addition, lower pH increased the content of H+ in the adsorption system, which led to electrostatic repulsion between metformin and positively charged functional groups on the surface of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO, and inhibited the binding of metformin on the three adsorbents, while the opposite was true at higher pH53. Overall, GO and its two forms of modified products, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO, showed high pH-sensitivity in the uptake of metformin, and under different pH conditions, the adsorption ability of CTOS-mGO for metformin showed obvious advantages.

Recyclability and stability studies

Reusability is one of the important factors to evaluate the comprehensive performance of adsorbents, which is of great significance for reducing the treatment cost and reducing the generation of waste residue54. The existing researches emphasizes that the stronger regeneration ability of dilute NaOH solution compared with hot water, dilute HCl solution and acetone is attributed to the substitution of metformin ions on the surface of the adsorbent by the hydroxide ion, which makes the adsorbent reusable in multiple cycles1,2. To further analyze and compare the applicability of the three adsorbents, desorption experiments were conducted to evaluate their stability and recyclability. With 0.2 M NaOH as eluent, the recyclability and stability experiments were completed under the conditions of 5 mg adsorbent, 25 mL 20 mg/mL metformin solution, 293 K (for GO and CTOS-mGO) or 303 K (for PFPA-rGO), pH 6.0 (for GO and PFPA-rGO) or pH 7.0 (for CTOS-mGO) and 120 min. As presented in Fig. 8B, the adsorption capacities of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO decreased with the increase of recycling times. The adsorption amount of the three freshly prepared adsorbents were 66.75, 79.02 and 60.96 mg/g, respectively, and their adsorption capacities were significantly higher than those of activated carbon prepared by Moringa oleifera seeds (65.01 mg/g) and chichá-do-cerrado (45.5 mg/g), which had great adsorption performance for metformin in existing studies2. After four times of regeneration treatment, their adsorption amount could still reach 42.97, 57.83, 40.47 mg/g. Obviously, compared with GO, its two forms of modified products CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO also exhibited excellent recycling performance for metformin removal, especially CTOS-mGO. In addition, the two modified products obtained in this study, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO, showed significantly higher adsorption capacity for metformin after five cycles compared to Zhu et al.‘s study1, indicating the importance of appropriate modification on the adsorption characteristics of GO.

Proposed removal mechanism of Metformin by GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO

For GO and CTOS-mGO, the presence of aromatic rings and the abundant oxygen-containing functional groups distributed on the surface of the sheets endowed them with the characteristics of π-electron acceptors or donors, and metformin with dissociative properties could serve as a stabilizer for this π–π interaction55. The hydrogen bonding interaction between the oxygen-containing functional groups of GO and CTOS-mGO and the amines of metformin, as well as the electrostatic interaction between the positively charged metformin and the negatively charged GO and CTOS-mGO were also important contributors to the adsorption reaction1. For PFPA-rGO, the oxygen-containing functional groups still existed and could form electrostatic interaction with metformin11,56. In addition, for the reduction product PFPA-rGO, the effectively restored delocalized electron cloud related to the graphene layer and the down-regulated abundance of oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface of the sheets made it have greater Lewis alkalinity and stronger electrostatic attraction, thereby improving its adsorption performance for metformin57. The shifting of the characteristic peaks in the FTIR spectra after adsorption of metformin confirmed the formation of the new intermolecular forces (Fig. 9). Furthermore, both types of functional modifications based on GO improved the dispersibility of the adsorbents and increased the interlayer spacing, providing more active sites for the adsorption of metformin, thereby increasing their adsorption capacity for metformin, which was particularly significant on CTOS-mGO11,18. The inferred adsorption mechanism might be briefly described as Fig. 10.

Conclusions

This study analyzed and compared the feasibility and efficiency of GO and its two forms of modified products CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO as adsorbents to remove metformin from aquatic environment under different adsorption conditions. GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO could also exhibit excellent adsorption performance when the reaction conditions such as pH and temperature of the adsorption system were changed, and compared with GO and PFPA-rGO, the silane coupling agent modified product CTOS-mGO occupied an absolute advantage in adsorption capacity. The conditions under which GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO could achieve maximum adsorption capacity (qm) within the investigated range were 293 K and pH 6.0, 293 K and pH 7.0, 303 K and pH 6.0, respectively. The kinetics of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO could be well fitted by the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, while the models suitable for the isotherm parameters of the three adsorbents were different, among which, the Freundlich isotherm was suitable for GO and CTOS-mGO, and the Langmuir isotherm was suitable for PFPA-rGO. The adsorption of metformin on GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO was all spontaneous exothermic reactions, which has been verified by thermodynamic datas. The implementation of desorption experiments confirmed the excellent adsorption performance and recyclability of GO, CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO, and the recycling degree of CTOS-mGO was still the highest after multiple regeneration treatments, while PFPA-rGO was comparable to GO. π-π interaction, as well as hydrogen bonding interaction, could be used to explain the outstanding adsorption performance and adsorption difference of GO and its two modified products CTOS-mGO and PFPA-rGO for metformin. Therefore, for GO, both silane coupling agent modification and natural extract reduction were alternative methods to improve its adsorption characteristics and adsorption capacity. Among them, silane coupling agent modification had a significant advantage in the adsorption of metformin.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Zhu, S. et al. Adsorption of emerging contaminant Metformin using graphene oxide. Chemosphere 179, 20–28 (2017).

Vieira, Y. et al. A critical review of the current environmental risks posed by the antidiabetic Metformin and the status, advances, and trends in adsorption technologies for its remediation. J. Water Process. Eng. 54, 103943 (2023).

Chen, C., Wen, M. Y. & Cheng, T. Accessible active sites activated by nano Cobalt antimony oxide @ carbon nanotube composite electrocatalyst for highly enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 48, 7719–7736 (2023).

Cheng, T., Wen, M. Y. & Cheng, C. Constructing heterojunctions of CoAl2O4 and Ni3S2 anchored on carbon cloth to acquire multiple active sites for efficient overall water splitting. J. Electroanal. Chem. 956, 118109 (2024).

Chen, C., Zhang, X. & Cheng, T. Construction of highly efficient Zn0.4Cd0.6S and Cobalt antimony oxide heterojunction composites for visible-light-driven photocatalytic hydrogen evolution and pollutant degradation. Water 14, 3827 (2022).

Spessato, L. et al. Optimization of Sibipiruna activated carbon Preparation by simplex-centroid mixture design for simultaneous adsorption of Rhodamine B and Metformin. J. Hazard. Mater. 411, 125166 (2021).

He, S. et al. Graphene oxide-template gold nanosheets as highly efficient near-infrared hyperthermia agents for cancer therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 15, 8451–8463 (2020).

Wang, Q. et al. In-situ formed Cyclodextrin-functionalized graphene oxide/poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) nanocomposite hydrogel as an recovery adsorbent for phenol and microfluidic valve. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 607 (Pt 1), 253–268 (2022).

Lv, Y. & Zhu, T. Polyethyleneimine-modified porous aromatic framework and silane coupling agent grafted graphene oxide composite materials for determination of phenolic acids in Chinese wolfberry drink by HPLC. J. Sep. Sci. 43 (4), 774–781 (2020).

Li, B., Jin, X., Lin, J. & Chen, Z. Green reduction of graphene oxide by sugarcane Bagasse extract and its application for the removal of cadmium in aqueous solution. J. Clean. Prod. 189, 128–134 (2018).

Chen, C., Wen, M. & Cheng, T. Photocatalytic degradation of Tetracycline wastewater through heterojunction based on 2D rhombic ZrMo2O8 nanosheet and nano-TiO2. J. Nanopart. Res. 24, 172 (2022).

Chen, C., Wang, L. & Cheng, T. Sliver doped sodium antimonate with greatly reduced the band gap for efficiently enhanced photocatalytic activities under visible light (experiment and DFT calculation). Mater. Res. 24, e20210100 (2021).

Guo, H. et al. A Method for Preparing Graphene by Reducing Graphene Oxide Based on Camellia Shell Extract (2015).

Liu, H., Cheng, Z., Li, J. & Xie, J. The dynamic changes in pigment metabolites provide a new Understanding of the colouration of Pyracantha fortuneana at maturity. Food Res. Int. 175, 113720 (2024).

Yang, B. Study on Extraction Process of Proanthocyanidins from Wild Pyracantha and Anti-aging Effect of Proanthocyanidins 54–55. Master thesis, Wuhan Polytechnic University (2011).

Wu, W., Zeng, Q. & Xiang, F. Optimization of extraction process of procyanidins in Pyracantha fortuneana fruit by response surface methodology. China Brew. 34, 116–120 (2015).

Kong, Q. Enhancement Principle of Graphene Oxide Functional Modification for the Removal of Heavy Metal Ions and Their Compound Pollutants 47–53. Doctoral thesis, South China University of Technology (2020).

Wang, H., Wang, X. & Zhao, X. Preparation and characterization of graphene oxide modified by silane coupling agent. Appl. Chem. Ind. 48, 97–99 (2019).

Sharma, D. et al. Spectroscopic and molecular modelling studies of binding mechanism of Metformin with bovine serum albumin. J. Mol. Struct. 1118, 267–274 (2016).

Yang, X. et al. Removal of Sb(III) by 3D-reduced graphene oxide/sodium alginate double-network composites from an aqueous batch and fixed-bed system. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 22374 (2021).

Gao, Y. et al. Graphene oxide interactions with co-existing heavy metal cations: adsorption, colloidal properties and joint toxicity. Environ. Sci. -Nano. 5 (2), 362–371 (2018).

Al-Kassawneh, M., Sadiq, Z. & Jahanshahi-Anbuhi, S. User-friendly and ultra-stable all-inclusive gold tablets for cysteamine detection. RSC Adv. 13 (28), 19638–19650 (2023).

Balashanmugam, P. & Kalaichelvan, P. T. Biosynthesis characterization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia roxburghii DC. aqueous extract, and coated on cotton cloth for effective antibacterial activity. Int. J. Nanomed. 10 (Suppl 1), 87–97 (2015).

Chen, C., Cheng, T. & Wang, W. Surface functionalization of Linde F (K) nanozeolite and its application for photocatalytic wastewater treatment and hydrogen production. Appl. Phys. A. 128, 468 (2022).

Panploo, K., Chalermsinsuwan, B. & Poompradub, S. Natural rubber latex foam with particulate fillers for carbon dioxide adsorption and regeneration. RSC Adv. 9 (50), 28916–28923 (2019).

Sierra-Padilla, A. et al. Incorporation of carbon black into a sonogel matrix: improving antifouling properties of a conducting polymer ceramic nanocomposite. Mikrochim Acta. 190 (5), 168 (2023).

Liu, S. & Tang, W. Photodecomposition of ibuprofen over g-C3N4/Bi2WO6/rGO heterostructured composites under visible/solar light. Sci. Total Environ. 731, 139172 (2020).

Abdelkhalek, A., El-Latif, M. A., Ibrahim, H., Hamad, H. & Showman, M. Controlled synthesis of graphene oxide/silica hybrid nanocomposites for removal of aromatic pollutants in water. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 7060 (2022).

Khan, M., Muhammad, M., AlOthman, Z. A., Cheong, W. J. & Ali, F. Synthesis of monolith silica anchored graphene oxide composite with enhanced adsorption capacities for Carbofuran and Imidacloprid. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 21027 (2022).

Jiang, L. et al. Design of a double-layered material as a long-acting moisturizing hydrogel-elastomer and its application in the field protection of elephant ivories excavated from the Sanxingdui ruins. RSC Adv. 14 (34), 24845–24855 (2024).

Upadhyay, R. K. et al. Grape extract assisted green synthesis of reduced graphene oxide for water treatment application. Mater. Letter. 160, 355–358 (2015).

Zhao, D. L. et al. Facile Preparation of amino functionalized graphene oxide decorated with Fe3O4 nanoparticles for the adsorption of cr (VI). Appl. Surf. Sci. 384, 1–9 (2016).

Eom, W. et al. Carbon nanotube-reduced graphene oxide fiber with high torsional strength from rheological hierarchy control. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 396 (2021).

Otsuka, H. et al. Transient chemical and structural changes in graphene oxide during ripening. Nat. Commun. 15 (1), 1708 (2024).

Gomez-Blanco, N. & Prato, M. Microwave-assisted one-step synthesis of water-soluble manganese-carbon nanodot clusters. Commun. Chem. 6, 174 (2023).

Zhao, G., Li, J., Ren, X., Chen, C. & Wang, X. Few-layered graphene oxide nanosheets as superior sorbents for heavy metal ion pollution management. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45 (24), 10454–10462 (2011).

Bai, S. et al. rGO modified nanoplate-assembled ZnO/CdO junction for detection of NO2. J. Hazard. Mater. 394, 121832 (2020).

Chen, C., Cheng, T. & Wang, W. Synthesis of fly Ash magnetic glass microsphere@BiVO4 and its hybrid action of visible-light photocatalysis and adsorption process. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 30, 1–14 (2021).

Li, C., Zhuang, Z., Jin, X. & Chen, Z. A facile and green Preparation of reduced graphene oxide using Eucalyptus leaf extract. Appl. Surf. Sci. 422, 469–474 (2017).

Wang, S. et al. Characterization and interpretation of cd (II) adsorption by different modified rice straws under contrasting conditions. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 17868 (2019).

Jiao, F. et al. Capacity and kinetics of Zearalenone adsorption by Geotrichum candidum LG-8 and its dried fragments in solution. Front. Nutr. 10, 1338454 (2024).

Jin, Z., Wang, X., Sun, Y., Ai, Y. & Wang, X. Adsorption of 4-n-nonylphenol and bisphenol-a on magnetic reduced graphene oxides: a combined experimental and theoretical studies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49 (15), 9168–9175 (2015).

Belhaj, A. F. et al. Experimental investigation, binary modelling and artificial neural network prediction of surfactant adsorption for enhanced oil recovery application. Chem. Eng. J. 406, 127081 (2021).

Gao, W. et al. Effects of biochar-based materials on nickel adsorption and bioavailability in soil. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 5880 (2023).

Gong, J. et al. Removal of cationic dyes from aqueous solution using magnetic multi-wall carbon nanotube nanocomposite as adsorbent. J. Hazard. Mater. 164 (2–3), 1517–1522 (2009).

Yang, J., Luo, Z. & Wang, M. Novel fluorescent nanocellulose hydrogel based on nanocellulose and carbon Dots for detection and removal of heavy metal ions in water. Foods 11 (11), 1619 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Investigation of the adsorption behavior of Pb(II) onto natural-aged microplastics as affected by salt ions. J. Hazard. Mater. 431, 128643 (2022).

Cantoni, B., Turolla, A., Wellmitz, J., Ruhl, A. S. & Antonelli, M. Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) adsorption in drinking water by granular activated carbon: influence of activated carbon and PFAS characteristics. Sci. Total Environ. 795, 148821 (2021).

Akpotu, S. O. & Moodley, B. Application of as-synthesised MCM-41 and MCM-41 wrapped with reduced graphene oxide/graphene oxide in the remediation of acetaminophen and aspirin from aqueous system. J. Environ. Manag. 209, 205–215 (2018).

Chen, C., Hou, B. X. & Cheng, T. The integration of both advantages of cobalt-incorporated cancrinite-structure nanozeolite and carbon nanotubes for achieving excellent electrochemical oxygen evolution efficiency. Catal Commun. 180, 106708 (2023).

Chen, C., Xin, X. & Cheng, T. The synergistic benefits of hydrate CoMoO4 and carbon nanotubes culminate in the creation of highly efficient electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution. Alexandria Eng. J. 87, 93–106 (2024).

Meng, F., Huang, Q., Larson, S. L. & Han, F. X. The adsorption characteristics of uranium(VI) from aqueous solution on Leonardite and Leonardite-derived humic acid: a comparative study. Langmuir 37 (43), 12557–12567 (2021).

Zhang, M. et al. Temperature and pH responsive cellulose filament/poly (NIPAM-co-AAc) hybrids as novel adsorbent towards Pb(II) removal. Carbohydr. Polym. 195, 495–504 (2018).

Kumar, P. S. et al. Understanding and improving the reusability of phosphate adsorbents for wastewater effluent Polishing. Water Res. 145, 365–374 (2018).

Hernández, B., Pflüger, F., Kruglik, S. G., Cohen, R. & Ghomi, M. Protonation–deprotonation and structural dynamics of antidiabetic drug Metformin. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 114, 42–48 (2015).

Zhou, S. et al. Montmorillonite-reduced graphene oxide composite aerogel (M-rGO): A green adsorbent for the dynamic removal of cadmium and methylene blue from wastewater. Sep. Purif. Technol. 296, 121416 (2022).

Huang, Z. et al. Adsorption of lead(II) ions from aqueous solution on low-temperature exfoliated graphene nanosheets. Langmuir 27 (12), 7558–7562 (2011).

Funding

This work was supported by Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects (ZK [2022] 365 and ZK [2022] 391); High-level talents start-up fund project of Guizhou Medical University ([2021] 007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L.: Literature collection, Manuscript written-review, Editing and supervision; H.L., X.W., J.X., Z.C.: Sample collection and carried out the experiment; X.W. and J.X.: Language check and manuscript supervision; H.L., X.W. and J.X.: Had fund acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Cheng, Z., Wu, X. et al. Preparation of graphene based composites using silane and Pyracantha fortuneana and their application in Metformin adsorption from aqueous solution. Sci Rep 15, 14395 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99307-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99307-y