Abstract

Compacted soil dams are critical structures for mining, water supply and power generation, particularly in tropical regions. Monitoring these dams is essential throughout their lifetime, as variations in reservoir water levels due to drought, rainfall or operational changes can significantly affect soil saturation and stability. This study developed a laboratory-scale geoelectrical monitoring system to investigate the dynamics of water percolation and variations in soil saturation in compacted soil dams. Time-lapse electrical resistivity tomography was used to analyze the effects of soil moisture and temperature on electrical resistivity. The results of the electrical resistivity tomography were consistent with the advance of the saturation front, which was observed through photographic records. However, after the saturation front had fully advanced, the direct correlation between surface soil moisture values and electrical resistivity variations was not trivial. This may have been due to the fact that this is a dynamic geotechnical structure, with fluctuations in the dam’s internal water level, variations in soil compaction, granulometric distribution and differences in acquisition time between the investigation methodologies. These results underline the importance of continuous monitoring for the early detection of failures and for effective dam management strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent history of dam failures and the importance of monitoring water saturation levels

Identifying and understanding the different levels of water saturation in dams is an extremely important procedure, not only for structural safety, but also for preventing catastrophic failures1. This analysis not only makes it possible to anticipate overflow risks and correct disparity in pressures along the dam, but it is also crucial for preventing structural failures due to loss of stability2. On the world stage, the study of dam safety has received increasing attention, driven by the alarming increase in cases of catastrophic failure of mining tailings dams, as highlighted in recent studies3,4. These events have resulted in a reassessment of safety protocols and the search for more effective methods of preventing structural failures5. In Brazil, one of South America’s main suppliers of mineral inputs to the whole world, attention to dam safety is even more relevant. The country has recently experienced mining dam failures that have resulted in environmental devastation and loss of human life6,7. These events have stimulated a significant increase in geophysical and geotechnical studies related to dam stability8,9,10. In addition to its importance in the mining industry, dam safety is even more relevant due to the significant role that hydroelectric dams play in the country’s energy matrix. With one of the cleanest energy matrices in the world, largely due to the extensive use of hydroelectric plants, Brazil stands out as an example of how hydroelectric power can contribute to reducing dependence on hydrocarbons and promoting more sustainable energy. Other countries are currently looking for ways to diversify their energy matrices and reduce their dependence on fossil fuels11. In this sense, hydroelectric plants of different sizes have become an attractive option, offering a renewable source of energy with a low environmental impact12. Given this scenario, attention to dam safety is becoming even more important, not only in Brazil, but also on a global scale13.

Recent studies have shown important results in understanding the hydrogeological and geotechnical processes involved in dam stability based on geophysical evaluations14,15. Several factors can compromise the stability of earth dams, including dead weight, water pressure, water flow, wave action, climatic effects and other natural phenomena16,17,18. In dams built with mining tailings, stability is affected by factors such as the segregation of materials during their disposal, variability in granulometry, and the potential generation of excessive pore pressures, especially under saturated conditions19,20. To ensure the safe operation of these structures, it is essential to carry out monitoring and evaluation of their geotechnical condition and hydromechanical behavior. Monitoring objectives include detecting fractures, pore pressure growth in the dam body due to uneven settlement and water infiltration, and fluctuations in the water level in the reservoir21. Comprehensive monitoring is required before, during and after filling, focusing on changes in the water regime, pore pressures, deformations, subsidence and stress in the body and base of the dam22. In addition, the impact of climate change, with an increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation and flood events, highlights the need for new methodologies for assessing the hydrological safety of dams23. The consideration of the state of saturation and the suction effect, as highlighted by24, is an example of these advances, allowing for a better understanding of the complex phenomena that can lead to structural failures in dams. In order to improve dam monitoring and the interpretation of data obtained by geotechnical instruments, it is essential to develop more comprehensive and accurate monitoring methodologies25,26,27. In this context, time-lapse electrical resistivity tomography can play an important role by providing variations in soil electrical resistivity over time, which can be associated with changes in the distribution of moisture and saturation of the soil in the dam body. The systematic acquisition of electrical data makes it possible not only to monitor the behavior of water inside the dam, but also to increase safety and efficiency in dam management, especially when integrated with other geotechnical monitoring tools given the direct coupling between flow and mechanical aspects in the behavior observed in the dam. This tool can help with the early detection of possible instability risks before they become visible on the surface, such as piping or areas of anomalous water flow through cracks or faults in the dam, allowing for proactive intervention and more informed decision-making by dam managers.

Dam monitoring studies using time-lapse electrical resistivity tomography: a review of recent years

The monitoring of the physical environment using Time-Lapse Electrical Resistivity Tomography has grown in recent decades with various applications in hydrogeological and geoenvironmental studies28,29. One of the first studies was conducted by30 and investigated the dynamics of soil moisture on a railway embankment using 2D and 3D geoelectrical monitoring, demonstrating the effectiveness of these techniques for monitoring earth infrastructures and preventing failures in high-risk areas. Particularly in the context of dams, the uncontrolled variation in water saturation levels, as well as the emergence of unmonitored water flow zones in the body of the soil dam, are one of the main factors responsible for reducing the stability of these structures and, consequently, possible failures4,31,32. In this way, the construction of semi-automatic geoelectric monitoring systems capable of injecting electric current into the soil by inserting metal rods and taking readings of subsoil potential differences at different depths is intended to help improve understanding of the relationship between variations in soil electrical resistivity and moisture content3334. carried out a dam model experiment in a sandbox, simulating exposure to water and monitoring variations in electrical resistivity. The authors used the inversion of electrical resistivity models to analyze the data collected and generate maps of electrical resistivity change. The methodology made it possible to visualize anomalies and understand changes in water saturation over time, contributing to the understanding of dam failure processes35. investigated internal erosion processes using electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) on a laboratory scale. To this end, a high-resolution resistivity probe system was developed and integrated into an apparatus for studying internal erosion phenomena such as suffusion. The ERT method was used to produce three-dimensional electrical resistivity profiles of the soil material, allowing changes in the porous matrix to be visualized and quantified36,3738. jointly used ERT measurements and fiber optic sensors to monitor river dikes. The results showed that the combination of methodologies can provide an effective and non-invasive solution for monitoring the integrity of earthen dikes, offering complementary data that improves the interpretation of the internal conditions of the structures39. demonstrated that ERT, when integrated with inversion models that take into account the 3D complexity of earth dams, is an interesting tool for the early detection of internal erosion.

The fact is that although34 carried out a detailed experiment on a laboratory-scale dam model to simulate exposure to water and monitor electrical resistivity, to date dam monitoring studies using time-lapse electrical resistivity tomography developed in controlled studies from the construction of laboratory-scale dams have not correlated soil moisture, temperature and electrical resistivity values. In this study, through the construction of a test box with materials and dimensions dedicated to carrying out geoelectric tests and a compacted soil dam with known geotechnical properties, we investigated the water saturation behavior of the compacted soil that makes up the dam body through the use of soil moisture and temperature sensors associated with electrical resistivity data collected from a dedicated geoelectric monitoring system for laboratory studies developed in the project. The study monitored the variations in temperature and moisture content of the most superficial layers of the downstream slope during the first filling of the upstream water reservoir, and evaluated how the changes imposed on the soil affected the variations in the soil’s electrical resistivity. During the process of filling a reservoir there are large variations in the saturation and percolation of water through the dam body, factors that can directly influence the physical integrity of the dam. The quick variation in pressure and the redistribution of water during this process can cause instabilities that affect the safety of the structure. The integrated approach between moisture sensors and geoelectric monitoring was supported by the photographic recording of the advance of the saturation front through the compacted soil until the appearance of water at the base of the downstream slope. This is the first study to use this combined approach of geoelectric monitoring, soil moisture and temperature sensors during the filling of a reservoir. The results and discussions allowed an analysis of how physical properties interact with each other and how changes in these conditions can influence the safety and stability of dams.

Materials and methods

Construction of the laboratory-scale dam

The use of laboratory-scale models in geophysical studies provides a controlled and replicable approach to investigating complex phenomena related to the subsurface. These models, often known as physical models or scale models, are built in laboratories and aim to reproduce properties and geometries of the subsurface under specific experimental conditions. In this study, a dedicated test box was built with specific dimensions and construction materials. Since the geophysical technique used is based on injecting an electric current into the ground, it was decided to use plastic materials, such as polypropylene and polycarbonate, to make up the side walls and foundation of the test box. These materials have less influence on the propagation of the electric current when compared to the metallic materials commonly used in the construction of reduced model boxes. Geophysical factors were also taken into account when designing the test box. In order to obtain coherent investigation levels for the study, it was decided that the box should have dimensions of 2 m (length) x 1.6 m (width) and 0.6 m (height). This made it possible to install electrical acquisition lines at the depths desired for the study and also allowed the lines to be moved away from the edges of the box, reducing the edge effect commonly observed in this type of study40,41,42.

The reduced model of the dam was built using a soil artificially produced in the laboratory from a mixture of four natural soils, the proportions of which were defined in order to meet specific granulometric characteristics and hydraulic conductivity coefficients in relation to the experiment, in the order of 10− 6 cm/s. The materials used to obtain the prepared soil were cream kaolin and three types of normal sand produced by the Technological Research Institute of the State of São Paulo. The color of the kaolin was chosen to better identify the saturation of the soil in the photographic records. These soils were mixed in the laboratory in order to obtain three different samples, varying only the percentages of each of the four natural materials mentioned above (Fig. 1). Tests were then carried out to characterize the samples, following the recommendations of43 for sample preparation, and compaction, according to44. Figure 1 below shows the particle size distribution curves obtained for each of the three prepared samples and Fig. 2a shows the compaction curves obtained with normal energy and without soil reuse.

Grain size distribution curves of the three laboratory-prepared samples, each formulated by varying the proportions of natural materials: kaolin and three standardized sand types. These curves illustrate the granulometric composition of each sample, providing insight into the distribution of particle sizes that define the textural characteristics of the materials used in the study.

After analyzing the results, Sample 2 was selected for the construction of the reduced physical model due to its granulometric characteristics, better workability and the behavior of the compaction curve, which showed an optimum moisture content of 19% and the highest value of maximum dry apparent density among the three samples, at 1665 kg/m³. Based on this result, the soil compaction conditions were defined for both the variable load permeability tests and the compaction of the material in the test box. The criteria defined were a degree of compaction of 95% of Normal Proctor (NP), leading to a dry bulk density of 1582 kg/m³, and a corresponding moisture content in the compaction curve of 13.9% (Fig. 2a). After analyzing the results, Sample 2 was selected for the construction of the reduced physical model due to its granulometric characteristics, better workability and the behavior of the compaction curve, which showed an optimum moisture content of 19% and the highest value of maximum dry apparent density among the three samples, at 1665 kg/m³. Based on this result, the soil compaction conditions were defined for both the variable load permeability tests and the compaction of the material in the test box. The criteria defined were a degree of compaction of 95% of Normal Proctor (NP), leading to a dry bulk density of 1582 kg/m³, and a corresponding moisture content in the compaction curve of 13.9%. Once the compaction conditions had been defined, a variable load permeability test was carried out on a statically compacted specimen in the laboratory. To carry out the test and due to the considerable presence of fines in the composition of the sample, a flexible wall permeameter was used, in accordance with45. The specimen was initially saturated, densified under low tensions (30 kPa) and finally subjected to water flow. The hydraulic conductivity coefficient (K) obtained in the test was 5.8 × 10−6 cm/s, which was in line with the criteria established for the experiment. The data from the permeability coefficient measurements obtained in the test are shown in Fig. 2b.

Once the criteria defined for the experiment had been met by means of the three main geotechnical requirements specified (granulometry, compaction and permeability), and the geometric characteristics of the reduced model of the dam had been defined, sample 2 was then reproduced in the laboratory in sufficient quantity to build the dam inside the test box. The natural soils were homogenized by quartering in known proportions, moistened and stored in individual containers with lids to prevent moisture loss. Each container contained the amount of homogenized material needed to prepare each of the seven compaction layers making up the body of the dam. Subsequently, the moisture content of the previously moistened materials was determined and corrected to bring them into line with the desired compaction moisture for compacting the embankment. Before compacting each of the layers, the amount of water needed to reach the design moisture content (13.9%) was added, and then the material was homogenized. A period of around 4 h was waited for the moisture content to stabilize, and then the material was compacted inside the box. To compact the material in the box, a compaction hammer was developed to reproduce the same compaction energy applied in the Normal Proctor test. To this end, the weight and drop height of the hammer needed to meet this criterion were defined. Figure 2c show the hammer being developed and the material being compacted inside the test box. At the end of compacting each layer, the degree of compaction and moisture content were measured.

Soil moisture and temperature sensors: technical characteristics and calibrations

The moisture and temperature data were acquired using low-cost microsensors commonly used in geotechnical, hydrogeological and geoenvironmental studies on a laboratory scale. The sensors were integrated into the Arduino platform using Arduino UNO R3 boards. The integrated programming environment uses a programming language based on C++, but with some additional functions and methods. Three soil moisture sensors were installed on the downstream slope, all in the same central section and transversal to the dam crest, at different heights: the first sensor was installed close to the edge of the test box, to avoid the influence of the electric current circulating in the dam body during the geoelectric readings, thus checking for possible interference in the moisture measurements; the second was positioned between the first and second geoelectric lines, on the crest of the dam, the third was installed in the same longitudinal section as the second sensor, between the fourth and fifth geoelectric investigation lines and, finally, the fourth moisture sensor was installed near the base of the downstream slope of the dam, between the sixth and seventh geoelectric investigation lines (Fig. 3a). In addition, a temperature sensor was installed next to the third moisture sensor to monitor the thermal variations of the soil in the body of the dam and make corrections to the electrical resistivity data. The cross-section of the dam with the height of the crest and the position of the lines on the downstream slope is shown in Fig. 3d.

The soil moisture measurement component is a resistive moisture sensor consisting of two elements: an electronic module equipped with an LM393 IC comparator and a probe with two pads, where each prong acts as an electrode. The sensor operates based on the well-known relationship between water content and soil moisture: in dry soil, the sensor measures higher resistance to the flow of electrical current; however, in soil with higher moisture content, it measures proportionally lower resistance (Fig. 3b). The sensor determines soil moisture content by measuring the potential difference between the two electrodes, which are fully embedded in the soil, allowing a low-intensity current to flow between them. Subsequently, the sensor measures the medium’s resistance and provides a response depending on the type of signal output used, i.e., the output pin of the electronic module. If the digital pin (D0) is used, the measured resistance is compared to a predefined threshold value, with the response being HIGH if above the threshold and LOW if below it. If the analog pin (A0) is used, as in this study, the output is a value ranging from 0 to 1023, directly proportional to the resistance measured.

The temperature sensor used, a DS18B20S probe type, consists of an electronic module encapsulated in a metal casing that is resistant to oxidation and provides excellent thermal conductivity, equipped with a thermistor element (Fig. 3c). The sensor operates based on the principle of the variation in electrical resistance of conductive materials as a function of temperature: the material’s resistance increases with rising temperature and decreases with lowering temperature. Using this relationship, the sensor measures the variation in electrical resistance of the bulb comprising the thermistor element and utilizes this measurement to calculate changes in temperature. The updated temperature value is output in degrees Celsius and transmitted as a digital signal, ensuring more accurate and reliable readings, as this format is less prone to noise and interference. The sensor operates within a range of − 55 °C to 125 °C, with a stated accuracy of ± 0.5 °C between − 10 ºC and 85 ºC, and an adjustable resolution of up to 0.0625 °C, as specified by the manufacturer. No calibration adjustments were made to the sensor beyond the initial factory calibration. As documented in the performance analysis study conducted by46, the sensor demonstrated excellent performance, with an uncertainty of 0.17 °C and an accuracy of 99.05% compared to a calibrated thermometer.

Studies such as those by47 highlight the importance of correcting electrical resistivity data with respect to temperature changes. In our study, the correction of electrical resistivity values for temperature variations was conducted following the same approach as48, who emphasized that temperature fluctuations and the evolution of pore water electrical conductivity have a significant impact on the accuracy of in-field volumetric moisture predictions, potentially reducing precision by up to tenfold. Therefore, it was crucial to correct the electrical resistivity data for temperature variations during the processing of time-lapse electrical resistivity data, using complementary soil moisture and temperature sensors. During the ten-day experiment on a scaled model of a compacted soil dam, the obtained electrical resistivity values were corrected for temperature using the relationship proposed by49. After the geophysical inversion process, the apparent electrical resistivity values extracted from 3D or 2D models were adjusted to a standard temperature of 25 °C. The correction was performed according to the following equation (Eq. 1).

where σ is the apparent electrical conductivity at temperature T, measured by the temperature sensor every minute, and tc is the temperature correction factor, which corresponds to the fractional change in σ per degree Celsius. In this study, a value of tc = 0.02 °C−1 was used, indicating that the apparent electrical conductivity increases by 2% for every 1 °C increase in temperature. The equation originally used to correct electrical conductivity data can also be applied to electrical resistivity, as electrical resistivity is the inverse physical parameter of electrical conductivity.

Instrumentation setup for soil moisture and temperature monitoring on the downstream slope of the experimental dam. (a) Schematic of the soil moisture sensors installed at different heights along the central cross-section of the downstream slope: Sensor 1 near the upper edge, Sensor 2 at the crest, Sensor 3 at mid-slope, and Sensor 4 near the base. (b) Schematic of the resistive soil moisture sensor, detailing its measurement principle based on the variation in electrical resistance relative to soil moisture content. (c) Schematic of the DS18B20S temperature sensor, illustrating its operating principle based on the change in electrical resistance with temperature. (d) Cross-sectional view of the dam body showing the reservoir water level, crest height, and electrode positioning on the downstream slope.

The moisture sensors were calibrated using test specimens made from the same material as the dam, with a compaction degree consistent with that achieved in the dam body but with varying moisture contents. Each specimen was compacted inside a Proctor cylinder with a volume of 1000 cm³, in accordance with the NBR 7182 standard. All specimens reached a compaction degree of 95% of the Standard Proctor (SP) with the optimal moisture content from the SP compaction curve. Subsequently, each specimen was either moistened by spraying or dried by air exposure until the desired moisture content was achieved, with volumetric variation allowed in both procedures. Finally, the sensors were inserted into each of the specimens, and moisture content readings were taken over time in an alternating manner, ensuring that each sensor recorded measurements in all the specimens. To minimize the variation in moisture content of each sample over time due to air exposure, the samples were sealed in bags during the measurements.

The results revealed that the moisture sensors have a sensitivity limit for samples with moisture content above 25%, as observed by50. In other words, soil samples with moisture levels exceeding this threshold generate inconsistent sensor responses, deviating from the curve that represents the relationship between the analog signal output and the moisture content, indicating that these sensors are only suitable for moisture measurements within the range where their responses are consistent. Therefore, for the calibration curve of the sensors, responses obtained from specimens with moisture content above 25% were excluded, as these values do not adequately reflect the true moisture levels of each sample. The graph in Fig. 4 shows the linear relationship established for each of the sensors. The overall linear relationship, considering all measurements from the sensors, had a correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.83 and was defined by the formula: y = -0.03x + 33.25.

Calibration curves for each soil moisture sensor (Sensors 1, 2, and 3) illustrating the linear relationship between the sensor output values and the corresponding soil moisture content. The ‘All’ sensor represents combined data from all sensors, showing both scatter points and its respective calibration curve. These regression lines are used to evaluate the accuracy and consistency of each sensor in measuring soil moisture across different conditions.

Geoelectric monitoring system

The electrical resistivity method is based on the resistance that a given material presents to the flow of electric current through it. The electrical resistance in soils can be influenced by various factors, such as mineralogical composition, degree of saturation, material compaction, concentration of dissolved salts, and temperature, among others51,52,53. The wide range of electrical resistivity values in geological materials is one of the reasons this method is widely used in various geotechnical and geoenvironmental studies54,55,56. This study employed the electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) technique, which involves obtaining soil resistivity values through the continuous injection of electric current (IAB) using a pair of metallic current electrodes. The variation in electric potential (ΔVMN) in the soil, generated in response to the current injection, is measured using another pair of metallic electrodes. The spacing between the electrodes, i.e., the type of array used during the survey (referred to as the geometric factor K), also influences the measurement of the apparent resistivity parameter. The apparent electrical resistivity (ρa) of the investigated volume can be calculated using Eq. (1) (Eq. 2).

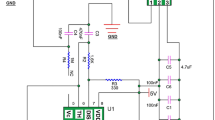

In this study, a semi-automated geoelectrical monitoring system was developed, capable of acquiring data from 7 Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT) lines within 40 min (Fig. 5a). This acquisition time is suitable for identifying the advancement of the water saturation front within the body of the dam in the proposed reduced-scale model, as the choice of the dam’s granulometric composition—and therefore the hydraulic conductivity of the material—was determined based on this timeframe. Additionally, this same 40-minute duration is feasible for replication at the field scale, i.e., in a real dam, representing a significant advancement in the monitoring of geotechnical structures. Currently, geoelectrical acquisitions in dams, hydroelectric plants, or mining tailings dams do not typically follow this frequency, with longer acquisition intervals. The implementation of a system that allows data acquisition at 40-minute intervals not only improves the temporal resolution of measurements but also enables the capture of dynamic variations in soil moisture and electrical resistivity in real-time (Fig. 5b).

The ERT lines were installed at intervals of 10 cm, with the first line positioned at the crest and the others along the downstream slope of the dam. The electrodes, with a diameter of 4 cm and a 10 cm spacing between them, were driven approximately 3 cm into the soil. The electrode diameter is below the threshold established by57, who demonstrated that the impact of diameter is negligible in the range of 6 to 12 mm, and that electrode immersion has a minimal effect on the geometric factor, depending on the spacing between the electrodes. Another factor considered in the study was the material used for the electrodes. The electrodes were made from phosphor bronze sheets to reduce the effect of corrosion, which is important both in laboratory studies and for the replicability of the study at the field scale. This metal alloy, primarily composed of copper, tin, and phosphorus, is known for its excellent corrosion resistance, particularly in marine environments or areas exposed to moisture, making it a common choice in industries that require durability and longevity of components. Additionally, phosphor bronze is widely used in electrical components due to its good conductivity58.

(a) Schematic representation of the semi-automated geo-electrical monitoring system, including ERT data acquisition lines installed on the dam, as well as soil moisture and temperature monitoring using Arduino-integrated sensors. The ERT lines are spaced 10 cm apart, starting from the dam crest and extending down the downstream slope. (b) Detailed view of the geo-electrical monitoring system, highlighting the electronic acquisition boards and the data recording and transmission system.

The electrode array provided a line of acquisition with sufficient length to reach an adequate investigation depth for the study, and the electrode spacing was adequate to obtain a substantial number of readings even in the more superficial layers. The system was built from electronic boards programmed to acquire data every 4 h using the dipole-dipole electrical array. This array is widely used in geoelectrical investigations, particularly for mapping and monitoring dams, due to its high sensitivity to lateral heterogeneities in the electrical properties of the soil10. This makes it effective for detecting variations and electrical contrasts in the subsurface, such as those that occur between different materials used in dam construction and the surrounding soil59,60,61. In this configuration, the distance between the pairs of electrodes is a fixed multiple of the electrode spacing within each dipole, typically denoted as , where is the distance between the electrodes within each dipole and is an integer factor.

The data were processed using the open-source software ResIPy. Unlike a data library, the P

ython-based software is a graphical user interface that integrates several libraries and algorithms, providing a comprehensive platform for geoelectrical analysis62,63. The initial processing step begins with the data import into the software and the application of preprocessing tools aimed at analyzing the quality of the readings. During this phase, erroneous apparent electrical resistivity values were removed, as laboratory studies can be affected by electromagnetic interference from nearby sources, such as high-voltage power lines or electrical equipment. After removing inconsistent data, the positions of the electrodes were entered, and a finite element mesh was generated for data inversion. ResIPy allows the construction of different types of meshes, such as quadrilateral and tetrahedral. In this study, the tetrahedral mesh was chosen due to its specific advantages in mapping electrical resistivity in environments with complex geometries, such as dams. The tetrahedral mesh offers greater flexibility in modeling irregular surfaces and better adapts to topographic variations, such as those observed along the downstream slope, where the electrode lines were positioned64. The use of tetrahedral meshes is particularly advantageous in dam and slope studies, as it allows a more detailed representation of resistivity variations in structures with non-planar geometry, providing greater precision in identifying conductive and resistive anomalies. Studies such as65,66 show that choosing a tetrahedral mesh is effective in modeling complex geophysical scenarios, yielding better results compared to quadrilateral meshes in irregular topography.

The inversion process of the geoelectrical data in the software is based on finite element methods, which solve the differential equations describing the propagation of electrical current in the subsurface. These algorithms convert surface measurements into three-dimensional electrical resistivity models67. The inversion of the geoelectrical data is an iterative process, in which the finite element model is adjusted to minimize the differences between the measured and calculated data. This adjustment is made through a cost function, expressed by Eq. (3):

where \(\:{\chi\:}^{2}\) represents the cost function, \(\:{V}_{measured}^{i}\) are the measured data, \(\:{V}_{predicted}^{i}\) are the data predicted by the model, \(\:{\sigma\:}_{i}\) is the uncertainty associated with each measurement, and N is the total number of measurements. The quality of the fit is measured by a statistic called the Root Mean Square (RMS), which quantifies the average difference between the observed values and the values predicted by the model68. All RMS values obtained during the processing of the geoelectrical data were below 2%, indicating that the model fit the observed data well and that the inversion results are highly reliable.

Results

Beginning of reservoir filling and progression of compacted soil saturation

The filling of the reservoir of the dam began on 04/09 at noon and was carried out in a controlled manner to prevent the removal of soil particles from the upstream slope, which could lead to the formation of preferential water percolation zones. The reservoir level was gradually raised to a height of 30 cm, minimizing the risk of structural damage to the slope. After the experiment began, the monitoring system was programmed to perform geoelectrical tests every 4 h and soil temperature and moisture readings every minute. Figure 6 presents the soil moisture readings from the four sensors installed on the dam and the variations in temperature values throughout the experiment. The plotted points are spaced every 120 min to facilitate visualization.

Soil moisture content from the four sensors installed on the dam, along with temperature variations throughout the experiment. Data points are shown at 120-minute intervals for clarity. Sensor 2, located near the crest, was the first to detect increased moisture, followed by sensors 1 and 3. Sensor 4, near the downstream toe, recorded moisture increase last. After nine days, sensors 1, 3, and 4 showed decreased moisture, while sensor 2 maintained higher levels due to its proximity to the reservoir.

The first moisture sensor to record an increase in moisture values was sensor 2, located in the central region of the dam crest. Subsequently, sensors 1 and 3 showed an increase in moisture values. Although located at the same topographic elevation on the downstream slope, the laboratory floor had a slight slope to direct water runoff as part of the building maintenance system. This slope directed the water flow inside the dam towards the right shoulder, which explains the difference in the arrival time of water at these sensors. Furthermore, the difference in the advance of the saturation front can also be attributed to variations in soil compaction along the dam. More compacted soils tend to hinder the movement of water, while less compacted zones facilitate its infiltration, thus influencing the saturation rate detected by each sensor. The last moisture sensor to register the presence of water was sensor 4, located near the base of the downstream slope.

After six days of the experiment, with the reservoir level maintained at the 30 cm mark, all moisture sensors recorded moisture values above 20%, and starting on the ninth day (04/18), sensor 3 showed a decrease in moisture values. This decrease was not observed by sensor 2, which was installed near the reservoir and within the influence area of the capillary fringe of the dam’s constituent material. This likely occurred because the sensor was located near the water reservoir and in the capillary fringe zone. The increase in moisture values observed by sensors 1, 3, and 4 is related to the advance of the saturation front during filling, while the decrease in these values after the ninth day (04/18) is related to the reduction in moisture content in the more superficial layers and the stabilization of the water level in deeper layers. The decrease of the saturation front in the superficial layers was observed on the side of the test box during the experiment and was consistent with the records from the sensors.

Progression of compacted soil saturation and variations in electrical resistivity

In addition to the monitoring carried out by the soil moisture sensors, the advance of the saturation front was mapped through photographic records and geoelectrical monitoring. This allowed the delimitation of the boundary line between the soil with higher saturation rates and the soil with lower saturation rates, as well as a comparison with the variations in the electrical anomalies observed on the downstream slope throughout the experiment. Photographic records from different days showed the progress of the saturation front in various parts of the compacted soil slope of the dam (Fig. 7). On 04/12, the saturation front was observed in the central region of the slope, between geoelectrical acquisition lines 3 and 4. On 04/15, the front advanced to lower areas of the slope, between acquisition lines 6 and 7, and on 04/17, the saturation front crossed the last installed electrode line. Thus, the photographic records visually documented the progress of the saturation front, providing a clear reference of where water was present in larger quantities. When compared to the resistivity data, a direct correlation was observed: in areas where the photographic records showed higher saturation, the geoelectrical measurements indicated conductive anomalies (Fig. 7).

Photographic documentation of the advancing saturation front on the downstream slope of the dam, captured on 4/12 and 4/15. The images highlight the progression of the saturated zone, starting between geoelectrical lines 3 and 4, moving to lines 6 and 7, and eventually passing the final electrode line. These visual observations were consistent with the conductive anomalies detected by geoelectrical measurements, confirming the correlation between moisture increase and resistivity changes.

The sensitivity of the geoelectrical monitoring system in detecting and accurately mapping the saturation front can be better visualized in ERT line 7. Although the electrodes in this line were located at the same topographic level on the downstream slope, the laboratory floor had a slope designed to facilitate the flow of water used for building maintenance. This slope caused the water flow within the dam to be directed toward the right abutment. This redirection of the water flow explains the difference in the time it took for water to reach the electrodes located in this area, resulting in variable moisture readings and, consequently, different patterns of electrical resistivity (Fig. 8). Identifying the location and movement of the saturation front has direct implications for dam stability. The advance of saturation generally tends to increase water pressure in the soil pores, which in turn reduces shear strength in cohesive soils. However, it is important to note that, in some types of unsaturated soils, the presence of a certain amount of moisture can increase cohesion and shear strength due to capillary forces, resulting in a higher friction coefficient compared to fully saturated soil. This phenomenon can lead to sliding or structural failures in the dam. The combination of soil moisture sensor and geoelectrical data with visual documentation provides a comprehensive view of the internal condition of the soil.

Photographic documentation of the saturation front on the downstream slope of the dam on 4/17, focusing on ERT line 7. The images highlight the water flow directed towards the right abutment due to the laboratory floor’s slope. This caused variations in moisture levels and resistivity readings along the electrode line. These observations emphasize the role of saturation in affecting dam stability by increasing pore water pressure and potentially reducing soil shear strength.

The behavior of water flow within the crest and downstream slope was monitored through variations in electrical resistivity in the dam, and the results were presented in three-dimensional models of the electrical resistivity variations at 8 a.m. every 2 days, with a monitoring period from 04/11 to 04/21 (Fig. 6). The distribution of electrical anomalies showed some superficial conductive electrical anomalies (ESA), which could be associated with variations in air humidity in the laboratory (Fig. 9). During the testing period, a temperature variation of 7.5 °C was observed, with higher average temperatures between 04/11 and 04/18, followed by a decrease in average temperatures after 04/18 until the end of the experiment. The superficial variations in soil electrical resistivity observed during the experiment reflect changes in environmental conditions, as the conductive electrical anomalies were more present and larger after 04/18, coinciding with the period of lower temperatures (around 19 °C). In general, electrical resistivity tends to increase as temperature decreases because the movement of ions in the soil water becomes slower, reducing electrical conductivity. However, in the case of this experiment, the decrease in temperature after 04/18 may have led to a redistribution of moisture in the soil. With the decrease in temperature, evapotranspiration decreased, resulting in greater water retention in the surface layers. This water retention increased surface electrical conductivity, manifesting as conductive anomalies in the electrical resistivity data (Fig. 9).

The first conductive electrical anomalies (CEA) related to the advancement of soil saturation were observed in the crest region, near the maximum water level of the reservoir, on 04/11. After two days, the development of these anomalies was identified in depth and towards the base of the downstream slope. The behavior of the anomalies indicates the establishment of a water flow from upstream to downstream. This behavior was also observed in the variations of electrical resistivity on 04/15, 04/17, 04/19, and 04/21. This behavior is consistent with the advancement of the water saturation front recorded by photographic records and moisture sensors. As water moves through the soil, regions with higher moisture content exhibit higher electrical conductivity, while dry areas show higher electrical resistivity.

Regarding the resistive electrical anomalies (HRZ), the highest electrical resistivity values can be observed in the region furthest from the crest. Throughout the experiment, there is a reduction in these areas. When the saturation front reaches the base region of the downstream slope, the resistive electrical anomalies become quite localized, as can be seen on 04/21. Another resistive electrical anomaly observed from 04/13 is related to the establishment of the water level inside the dam. This occurred due to the saturation front reaching the more superficial layers thanks to the capillarity of the material used in the dam construction. After that, the surface region exhibited a higher moisture content than the initial level of the experiment, as shown in the graph with variations in soil moisture content (Fig. 6). However, the deeper layers, below the water level established inside the dam, showed higher electrical conductivity than the superficial layers. This process of establishing the water level in the reservoir, due to the hydrostatic equilibrium between the upstream and downstream hydraulic head, was also identified by the time-lapse electrical resistivity tomography.

Three-dimensional models depicting variations in electrical resistivity within the dam, monitored daily at 8 AM from 04/11 to 04/21. The models illustrate the progression of conductive electrical anomalies (CEA) associated with the saturation front, first observed near the crest on 04/11, and subsequently developing in depth towards the downstream base. Increased surface conductivity coincided with lower air temperatures, reflecting a redistribution of soil moisture and demonstrating the correlation between water flow, resistivity changes, and the stability of the dam structure. Resistive anomalies (HRZ) decreased in extent over the monitoring period, highlighting the impact of saturation on subsurface conditions.

Discussion

Relationship between variations in electrical resistivity, soil moisture content and temperature

The relationship between variations in electrical resistivity, soil moisture, and temperature was investigated through 60 three-dimensional resistivity models, generated based on 6 daily readings over the 10-day experiment period. During the preprocessing data control process for these models, checks were conducted to identify and remove inconsistent electrical resistivity readings. This process focused on eliminating spurious apparent resistivity readings that could compromise the accuracy of the results. As mentioned, in a laboratory environment, incorrect readings may occur due to nearby electromagnetic interference sources, such as high-voltage lines or electrical equipment, which affect sensor accuracy. After removing these spurious readings, the final dataset consisted of 52 resistivity readings below sensor 2, 58 resistivity readings below sensor 3, and 53 resistivity readings below sensor 4 (Fig. 10). Quality control was necessary to ensure that the three-dimensional models accurately reflected the actual conditions of the experiment, providing a solid foundation for the detailed analysis of how the presence of water in the dam body, combined with variations in moisture and temperature, influences the electrical resistivity of the soil. The objective of this analysis was to better understand how the presence of water in the dam body, along with moisture and temperature variations, influences the electrical resistivity of the soil. This analysis is of particular interest in dam studies, as the behavior of water within the soil structure is a crucial factor for its stability and safety. During the initial filling, soil saturation characteristics can change rapidly, impacting both moisture distribution and electrical resistivity.

The graph in Fig. 10 presented the inverted values of electrical resistivity on the x-axis and the soil moisture content on the y-axis, revealing a significant concentration of low electrical resistivity values at higher soil moisture levels, particularly for Sensor 2. This sensor is located at the crest of the dam, near the reservoir, where the proximity to the water source and the capillarity of the soil used in the study (silt and sand) make the sensor sensitive to moisture variations. As the reservoir water level decreased, a corresponding decrease in soil moisture content in the upper layers was observed, as well as variations in electrical resistivity values in this region, highlighting the relationship between soil saturation and its electrical conductivity. Although this relationship seems evident, the first filling of a dam reservoir, whether the structure is responsible for storing water, radioisotopes, or mining tailings, is a critical moment where the interaction between water and soil can reveal potential zones of weakness or instability. Therefore, the ability to detect these electrical resistivity variations even before they are fully reflected in the measured moisture levels, as observed in Sensor 2, offers a promising tool for predicting and mitigating risks associated with the structural safety of the dam.

For Sensor 3, located in the intermediate region of the downstream slope, a concentration of low electrical resistivity values was observed at higher soil moisture levels, similar to the behavior recorded by Sensor 2. However, an anomalous behavior was noted before the saturation front reached the sensor’s location (recorded on 04/12 at 7:50 PM, as illustrated in the graph of Fig. 6). During this interval of days, especially close to the arrival of the saturation front, some readings of low electrical resistivity values were observed even before a significant increase in soil moisture. This anticipation of reduced resistivity values can be explained by the three-dimensional processing of the electrical data using the finite element mesh. In this process, the electrical data recorded in the upstream lines, farther from Sensor 3 and already with high soil moisture content, influence the data inversion, resulting in an apparent decrease in electrical resistivity values before the moisture is actually detected by the sensor. This phenomenon occurs due to the propagation of saturation effects in the adjacent soil layers, which, although not directly in contact with the sensor, affect the recorded electrical conductivity.

Sensor 4, located in the region closest to the base of the downstream slope, exhibited behavior similar to Sensors 2 and 3 in terms of the concentration of low electrical resistivity values at higher soil moisture levels after the saturation front reached its position (on 04/15 at 8:00 PM, as shown in the graph in Fig. 6). However, one notable aspect is that, after the soil saturation at the sensor’s location and the subsequent decrease in electrical resistivity values, these values remained low even after the soil moisture levels decreased. This behavior is contrary to what is typically expected, where an increase in electrical resistivity would normally be observed as soil moisture decreases. This discrepancy can be explained by the fact that, after the saturation front progresses and the water level inside the embankment stabilizes, the sensor’s investigation depth becomes a relevant factor. Due to the lower investigation depth at this point and the depth reach of the electrical tomography technique, the electrical resistivity values decrease because, although the moisture content at the sensor location is lower (around 9%), the influence of the deeper water level persists. This ongoing influence causes small variations in the embankment’s water level to directly affect the measured resistivity values, keeping them low.

Final dataset for three-dimensional resistivity models, comprising 52 readings from sensor 2, 58 from sensor 3, and 53 from sensor 4. A quality control process removed spurious readings affected by electromagnetic interference, ensuring data accuracy. This analysis aims to understand the influence of soil moisture content and temperature on the electrical resistivity of the dam, which is crucial for assessing its stability and safety during initial filling.

The internal dynamics of the embankment were also analyzed based on the interactions between soil moisture, electrical resistivity, and temperature. The graph in Fig. 11 below illustrates these relationships for Sensor 2, highlighting variations over time that are essential for monitoring and ensuring the structural safety of the dam. Firstly, upon analyzing the variations in moisture throughout the days of the experiment, it was observed that the proximity to the water reservoir and the capillarity of the embankment material directly influenced the readings. Soil moisture showed predictable variations, increasing and decreasing according to these conditions. In parallel, the inverted electrical resistivity values exhibited an inverse behavior to the moisture content, as expected: as moisture increased, electrical resistivity tended to decrease. Between 04/11 at 04:00 AM and 04/14 at 00:00 AM, there was an increase in the soil moisture content recorded by Sensor 2, which stabilized at 22.5%. During this same period, the electrical resistivity decreased and stabilized at values consistent with the embankment material when filled with water. However, at another point in the experiment (04/17 at 16:00 PM), even with an increase in moisture content to values between 23% and 27.5%, a different decrease in electrical resistivity was observed compared to the previous one. This discrepancy emphasizes the complexity of directly correlating electrical resistivity with moisture content in a dynamic geotechnical structure. Factors such as soil compaction, particle size distribution and variations in the water table introduce additional complexities into the electrical resistivity response. Furthermore, the temporal resolution of electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), which requires approximately 40 min for data acquisition in the developed system, contrasts with the higher frequency measurements of soil moisture sensors.

The observed resistivity variation can be attributed to the temperature differences recorded between the two study intervals. In lower temperatures, evaporation of water from the soil surface is reduced, allowing more water to fill the soil pores, which increases electrical conductivity and results in lower electrical resistivity values. Additionally, the temperature variation, although relatively small (around 7 °C), may have influenced the viscosity of the water, impacting the hydraulic conductivity of the material. This change in hydraulic conductivity may, in turn, affect water flow through the pores and, consequently, the distribution of electrical resistivity in the soil. These observations reinforce that, although the general trend of increasing humidity leading to decreasing electrical resistivity is true, localized variations and measurement restrictions must be taken into account when interpreting the results.

The direct relationship between temperature, moisture, and electrical resistivity highlighted the importance of monitoring the thermal conditions of the soil over time. Furthermore, it was important to note that moisture sensors, being more sensitive to localized changes and taking measurements every minute, captured rapid variations in moisture. In contrast, geoelectrical monitoring, which required about 40 min to complete a cycle of readings across all 7 acquisition lines, reflected a more generalized trend in the physical property behavior of the soil over time. This difference in measurement scales indicates that ERT is more effective in capturing long-term variations rather than rapid changes in moisture. Thus, while moisture sensors provided point-based data, the analysis of electrical resistivity variations offered a more comprehensive view of the soil conditions, which was crucial for understanding the embankment’s behavior in a long-term context (Fig. 11).

Correlation between soil moisture, inverted resistivity, and temperature for Sensor 2. Increased soil moisture led to decreased resistivity, particularly between 04/11 and 04/14. On 04/17, despite higher moisture levels, lower temperatures resulted in reduced resistivity due to decreased evaporation, highlighting the significance of temperature monitoring for dam stability.

In the graph for Sensor 3 presented in Fig. 12, the soil moisture values gradually increased starting from 04/12 at 20:00, due to the approach of the saturation front. However, soil saturation is not homogeneous throughout the compacted embankment, with some areas being more saturated than others. This variation is due to differences in the compaction levels of the material, as identified in the compaction tests conducted in the soil laboratory. More compacted soils have lower porosity, making it harder for water to infiltrate, while less compacted soils allow greater water movement. Geoelectrical monitoring was able to capture these compaction variations, reflected in changes in electrical resistivity, providing a broader view of the soil behavior. On the other hand, the moisture sensor provided localized information, limited to the installation point. This distinction between localized measurements and measurements on a larger scale is fundamental to explaining the discrepancies between direct and indirect investigation techniques. The variations in electrical resistivity observed are not just a function of moisture content, but also reflect heterogeneities in soil properties and the dynamics of water movement within the embankment. After 04/18 at 00:00, a decrease in moisture content occurred. This likely happened because the initially dry soil underwent an intense saturation process via capillarity until the water level in the embankment stabilized. Although the surface layers maintained higher moisture levels compared to the beginning of the study, these values decreased after the groundwater level stabilized. Additionally, a drop in soil temperature was observed after this date, which influenced the increase in electrical resistivity, as resistivity tends to increase with lower temperatures, in addition to the decrease in soil moisture. Another important aspect was the variation in electrical resistivity observed at the beginning of the experiment, when the soil had low moisture content. The soil temperature, influenced by daily and nightly cycles, also impacted these values. During the day, the rise in temperature reduced resistivity, while at night, the opposite effect occurred (Fig. 12).

Relationship between soil moisture, inverted resistivity, and temperature for Sensor 3. Soil moisture content began to rise on 04/12/2024 due to the advancing saturation front, with variations caused by differing compaction levels. A decrease in moisture was noted after 04/18/2024, as the soil stabilized, leading to increased resistivity due to lower temperatures. Daily temperature fluctuations also influenced resistivity, with higher daytime temperatures correlating with lower resistivity.

The graph for Sensor 4, presented in Fig. 13 and located near the base of the downstream slope, showed an initial behavior of soil moisture content values with little variation, oscillating between 7.8% and 8%, similar to what was observed for the same parameter in Sensor 3. This behavior was consistent with the nature of the embankment material, where moisture content remained relatively stable. The variations in the inverted electrical resistivity values, which oscillated between 136.9 ohm.m and 831.4 ohm.m, are consistent with the composition of the soil and the distribution of moisture throughout the embankment. This reinforces that electrical resistivity measurements provide information on moisture distribution on a broader scale, rather than exact point correlations with localized moisture sensors.

Relationship between soil moisture and inverted resistivity for Sensor 4 at the base of the downstream slope. Initially, soil moisture was stable (7.8-8%), while resistivity varied (136.9 to 831.4 ohm·m). After 04/13 20:00 PM, moisture increased due to the saturation front, leading to decreased resistivity as saturation stabilized above 25%. By 04/19 8:00 AM, moisture dropped to about 9.5%, indicating stabilized groundwater levels and further reduced resistivity.

This happens because, while the moisture sensor collects point data, the geoelectrical monitoring system is influenced by soil characteristics at different depths and laterality levels, as well as variations in material compaction. Discrepancies in electrical resistivity reflect these complex soil variations and the heterogeneous distribution of moisture. From 04/13 at 20:00, an increase in soil moisture content occurred due to the proximity of the saturation front. During this period, the electrical resistivity values showed greater variation, which is consistent with the non-homogeneous nature of the saturation front’s advance, as evidenced in Figs. 7 and 8. After the saturation level stabilized above 25%, the electrical resistivity values decreased and showed less variation. This behavior is consistent with the more complete saturation of the soil, where water filling the pores significantly reduces electrical resistivity. However, it is important to emphasize that while the overall trend of increased saturation leading to decreased resistivity is observed, variations in soil structure and measurement limitations may result in specific areas where this correlation is not as evident. After 04/19 at 08:00, soil moisture content decreased to around 9.5%, still higher than the initial levels before the saturation front arrived. This suggests that the groundwater level was established within the embankment after saturation. The electrical resistivity tomography, which collects information at different depths, reflects this change in soil conditions, showing lower resistivity values and less variation than at the beginning of the study. The decrease in temperature during this period also contributed to reducing evaporation from the soil surface, retaining more water in the pores and consequently decreasing electrical resistivity values.

Conclusions

In this study, a laboratory-scale geoelectrical monitoring system was developed to investigate the dynamics of soil saturation in compacted soil embankments during initial filling. The results showed that the increase in electrical conductivity observed in electrical resistivity tomography was consistent with photographic records of the advance of the saturation front along the dam body. However, after the saturation front had fully advanced, the ability to detect subsequent variations in the water level inside the embankment was more evident in the soil moisture sensor data than in the resistivity tomography results. This emphasizes the complexity of directly correlating geoelectric data with moisture distribution in such a dynamic geotechnical structure, where variations in soil compaction, particle size distribution and fluctuating water levels influence measurements.

Despite these issues, the results reinforce the relevance of geoelectrical monitoring for analyzing moisture distribution patterns in compacted soil embankments. The ability to monitor the dynamics of the saturation front and its impact on electrical resistivity is essential for assessing the embankment’s behavior over time. In tropical countries, where compacted soil embankments are widely used due to the abundant availability of weathered soils and high precipitation rates, it is essential to ensure the physical integrity of the structure through continuous monitoring. The results of this study demonstrate the importance of integrating geotechnical and geoelectrical monitoring methods for improving embankment management. Although electrical resistivity variations do not allow direct quantification of soil moisture variations in all phases, the method remains a valuable tool for identifying broader trends in soil saturation. By combining various monitoring techniques, it is possible to develop a more comprehensive understanding of embankment stability, contributing to the early detection of potential risks and the implementation of effective dam safety strategies.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Guireli Netto, L.

References

Asthana, B. N. & Khare, D. Dam Safety. In Recent Advances in Dam Engineering(eds. Asthana, B. N. & Khare, D.) 355–362 (Springer International Publishing, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32278-6_16

Islam, K. & Murakami, S. Global-scale impact analysis of mine tailings dam failures: 1915–2020. Glob Environ. Chang. 70, 102361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102361 (2021).

Owen, J. R., Kemp, D., Lèbre, É., Svobodova, K. & Murillo, G. P. Catastrophic tailings dam failures and disaster risk disclosure. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101361 (2020).

Clarkson, L. & Williams, D. An overview of conventional tailings dam geotechnical failure mechanisms. Min. Metall. Explor. 38, 1305–1328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42461-021-00381-3 (2021).

Piciullo, L., Storrøsten, E., Zhongqiang, L., Farrokh, N. & Lacasse, S. A new look at the statistics of tailings dam failures. Eng. Geol. 303, 106657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2022.106657 (2022).

Rotta, L. H. S. et al. The 2019 Brumadinho tailings dam collapse: possible cause and impacts of the worst human and environmental disaster in Brazil. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 90, 102119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2020.102119 (2020).

Zhu, F., Zhang, W. & & Puzrin, A. M. The slip surface mechanism of delayed failure of the Brumadinho tailings dam in 2019. Commun. Earth Environ. 5 https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-01086-9 (2024).

Guireli Netto, L., Gandolfo, O. C. B., Malagutti Filho, W. & Dourado, J. C. Non-Destructive investigation on small Earth dams using geophysical methods: seismic surface wave multichannel analysis (MASW) and S-Wave refraction seismic methods. Braz J. Geophys. 5–19. https://doi.org/10.22564/rbgf.v38i1.2031 (2020).

Koppe, J. C. Lessons learned from the two major tailings dam accidents in Brazil. Mine Water Environ. 40, 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10230-020-00722-6 (2021).

Moreira, C. A. et al. Application of electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) in uranium mining Earth dam. J. Geophys. Eng. 6, 1265–1279. https://doi.org/10.1093/jge/gxac082 (2022).

Hassan, Q. et al. The renewable energy role in the global energy transformations. Renew. Energy Focus 48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ref.2024.100545 (2024).

Donchyts, G. et al. 2022 High-resolution surface water dynamics in Earth’s small and medium-sized reservoirs. Sci. Rep. 12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17074-6

Şen, Z. Reservoirs for water supply under climate change Impact—A review. Water Resour. Manage. 35, 3827–3843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-021-02925-0 (2021).

Guireli Netto, L., Singha, K., Moreira, C. A., Gandolfo, O. C. B. & Albarelli, D. S. N. A. Investigation of fractured rock beneath a uranium-tailing storage dam through UAV digital photogrammetry and seismic refraction tomography. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1281076. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2023.1281076 (2023).

Franco, L. M., La Terra, E. F., Panetto, L. P. & Fontes, S. L. Integrated application of geophysical methods in Earth dam monitoring. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 83, 62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-024-03551-x (2024).

Richards, K. S. & Reddy, K. R. Critical appraisal of piping phenomena in Earth dams. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 66, 381–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-007-0095-0 (2007).

Guedes, V. J. C. B., Borges, W. R., da Cunha, L. S. & Maciel, S. T. R. Characterization of an Earth dam in Brazil from seismic refraction tomography and multichannel analysis of surface waves. J. Appl. Geophys. 208, 104893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jappgeo.2022.104893 (2023).

Siacara, A. T., Napa-García, G. F., Beck, A. T. & Futai, M. M. Reliability analysis of an Earth dam under rainfall effects. Int. J. Geosynth Ground Eng. 10, 59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40891-024-00571-1 (2024).

Ouellet, S. M. et al. Advanced monitoring of tailings dam performance using seismic noise and stress models. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 301. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00629-w (2022).

Oliveira, L. et al. Improving tailings dam risk management by 3D characterization from resistivity tomography technique: case study in São Paulo – Brazil. J. Appl. Geophys. 210, 104924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jappgeo.2023.104924 (2023).

Misgana, K. & Meten, M. Seepage modeling approaches in the dam site and through the dam body: a review. Arab. J. Geosci. 17, 33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-023-11822-2 (2024).

Nan, S. et al. Geotechnical, geoelectric and tracing methods for Earth/Rock-Fill dam and embankment leakage investigation. Surv. Geophys. 45, 525–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-023-09806-8 (2024).

Lompi, M., Mediero, L., Soriano, E. & & Caporali, E. Climate change and hydrological dam safety: a stochastic methodology based on climate projections. Hydrolog Sci. J. 68(6), 745–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2023.2192873 (2023).

Lachgueur, K., Abou-Bekr, N., Taibi, S. & Fleureau, J. M. Effects of compaction and Suction on the hydromechanical properties of a dam core clay. Transp. Geotech. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2020.100498 (2021).

Li, B., Yang, J. & Hu, D. Dam monitoring data analysis methods: A literature review. Struct. Control Health Monit. https://doi.org/10.1002/stc.2501 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. A critical review of statistical model of dam monitoring data. J. Build. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.108106 (2023).

Rana, S. & Mishra, V. N. Dam health check and monitoring using advanced tools of geophysics. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Dam Safety Management and Engineering. ICDSME2023 2023. Water Resources Development and Management (Mohd Sidek, L. et al.) (Springer, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-3708-0_22

Dimech, A. et al. A review on applications of Time-Lapse electrical resistivity tomography over the last 30 years: perspectives for mining waste monitoring. Surv. Geophys. 43, 1699–1759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-022-09731-2 (2022).

Whiteley, J. et al. Assessing the risk of slope failure to highway infrastructure using automated time-lapse electrical resistivity tomography monitoring. Transp. Geotech. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2023.101129 (2023).

Chambers, J. E. et al. 4D electrical resistivity tomography monitoring of soil moisture dynamics in an operational railway embankment. Near Surf. Geophys. 12, 61–72. https://doi.org/10.3997/1873-0604.2013002 (2014).

Talukdar, P. & Dey, A. Hydraulic failures of earthen dams and embankments. Innov Infrastruct Solut. 4, 42 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41062-019-0229-9

Rodríguez, R. et al. How to prevent flow failures in tailings dams. Mine Water Environ. 40, 83–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10230-021-00752-8 (2021).

Binley, A. et al. The emergence of hydrogeophysics for improved Understanding of subsurface processes over multiple scales. Water Resour. Res. 51, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015WR017016 (2015).

Shin, S., Park, S. & Kim, J. H. Time-lapse electrical resistivity tomography characterization for piping detection in earthen dam model of a sandbox. J. Appl. Geophys. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jappgeo.2019.103834 (2019).

Masi, M., Ferdos, F., Losito, G. & Solari, L. Monitoring of internal erosion processes by time-lapse electrical resistivity tomography. J. Hydrol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125340 (2020).

Singha, K., Day-Lewis, F. D., Johnson, T. & Slater, L. D. Advances in interpretation of subsurface processes with time-lapse electrical imaging. Hydrol. Process. 29, 1549–1576. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.10280 (2015).

Netto, L. G. et al. Characterization of excavated radionuclide retention ponds in a uranium mine in the process of decommissioning using geophysical methods. Pure Appl. Geophys. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-024-03602-0 (2024).

Hojat, A. et al. Laboratory studies using electrical resistivity tomography and Fiber optic techniques to detect seepage zones in river embankments. Geosciences 11(2), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences11020069 (2021).

Norooz, R. et al. Monitoring of Älvkarleby test embankment dam using 3D electrical resistivity tomography for detection of internal defects. J. Civil Struct. Health Monit. 14, 1275–1294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13349-024-00785-x (2024).

Singha, K., Day-Lewis, F. D. & Moysey, S. Accounting for tomographic resolution in estimating hydrologic properties from geophysical data. In Subsurface Hydrology: Data Integration for Properties and Processes (eds Hyndman, D. W., Day-Lewis, F. D. & Singha, K.) https://doi.org/10.1029/171GM16 (2007).

Ronczka, M., Hellman, K., Günther, T., Wisén, R. & Dahlin, T. Electric resistivity and seismic refraction tomography: a challenging joint underwater survey at Äspö hard rock laboratory. Solid Earth. 8, 671–682. https://doi.org/10.5194/se-8-671-2017 (2016).

Hung, Y. C., Chou, H. S. & Lin, C. P. Appraisal of the Spatial resolution of 2D electrical resistivity tomography for geotechnical investigation. Appl. Sci. 10(12), 4394. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10124394 (2020).

ASTM International. Standard Test Methods for Laboratory Determination of Water (Moisture) Content of Soil and Rock by Mass. ASTM D2216-19, West Conshohocken (ASTM International, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1520/D2216-19

ASTM International. Standard test methods for laboratory compaction characteristics of soil using modified effort (56,000 ft-lbf/ft3 (2,700 kN-m/m3)). ASTM D1557-12. https://doi.org/10.1520/D1557-12R20 (2012). West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International.

ASTM International. Standard Test Method for Resistance To Degradation of Small-Size Coarse Aggregate by Abrasion and Impact in the Los Angeles Machine. ASTM C131/C131M-20 (ASTM International, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1520/C0131_C0131M-20

Yulizar, D. et al. Performance analysis comparison of DHT11, DHT22 and DS18B20 as temperature measurement. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-94-6463-232-3_5 (2023).

Corwin, D. L. & Scudiero, E. Review of soil salinity assessment for agriculture across multiple scales using proximal and/or remote sensors. Adv. Agron. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.agron.2019.07.001 (2019).

Dimech, A. et al. A multiscale accuracy assessment of moisture content predictions using time-lapse electrical resistivity tomography in mine tailings. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48100-w (2023).

Ma, R. et al. Comparing temperature correction models for soil electrical conductivity measurement. Precision Agric. 12, 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-009-9156-7 (2011).

Adla, S. et al. Laboratory calibration and performance evaluation of Low-Cost capacitive and very Low-Cost resistive soil moisture sensors. Sensors 20(2), 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20020363 (2020).

Bazin, S. & Pfaffhuber, A. A. Mapping of quick clay by electrical resistivity tomography under structural constraint. J. Appl. Geophys. 98, 280–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jappgeo.2013.09.002 (2013).

Chen, H. Exploring subsurface hydrology with electrical resistivity tomography. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 813. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00350-4 (2022).

Mohammed, N. H., Gülen, L., Gürbüz, E. & Pekşen, E. Time-lapse electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) monitoring of used engine oil contamination in laboratory setting. J. Appl. Geophys. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jappgeo.2022.104531 (2022).

Lowrie, W. Fundamentals of Geophysics. Second Edition 375 (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Balasco, M., Lapenna, V., Rizzo, E. & Telesca, L. Deep electrical resistivity tomography for geophysical investigations: the state of the Art and future directions. Geosciences 12(12), 438. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences12120438 (2022).

Moreira, C. A. et al. Using electrical resistivity tomography to understand the hydrogeological behavior of acid drainage percolation in a fractured aquifer at a uranium mining site. Mine Water Environ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10230-024-00998-y (2024).

Clément, R. & Moreau, S. How should an electrical resistivity tomography laboratory test cell be designed? Numerical investigation of error on electrical resistivity measurement. J. Appl. Geophys. 127, 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jappgeo.2016.02.008 (2016).

Cardarelli, E. & Donno, G. D. Advances in electric resistivity tomography: theory and case studies. Innov. Near-Surface Geophys. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812429-1.00002-7 (2019).

Martorana, R., Fiandaca, G., Ponsati, A. C. & Cosentino, P. Comparative tests on different multi-electrode arrays using models in near-surface geophysics. J. Geophys. Eng. 6, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-2132/6/1/001 (2009).

Neyamadpour, A., Abdullah, W. A. T. W., Taib, S. & Neyamadpour, B. Comparison of Wenner and dipole–dipole arrays in the study of an underground three-dimensional cavity. J. Geophys. Eng. 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-2132/7/1/003 (2010).

Moreira, C. A., Lapola, M. M. & Carrara, A. Comparative analyzes among electrical resistivity tomography arrangements in the characterization of flow structure in free aquifer. Geofís Int. 55(2), 119–129 (2016).

Boyd, J., Blanchy, G., Saneiyan, S., McLachlan, P. & Binley, A. 3D geoelectrical problems with ResIPy, an open source graphical user interface for geoelectrical data processing. Fast Times. 24 https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.35381.63205 (2019).

Doyoro, Y. G. et al. A review of open software resources in python for electrical resistivity modelling. Geosci. Lett. 9, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40562-022-00214-1 (2022).

Xiao, Z. et al. Numerical simulations of the acoustic and electrical properties of digital rocks based on tetrahedral unstructured mesh. J. Geophys. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1093/jge/gxae077 (2024).

Furman, A., Ferré, T. P. A. & Warrick, A. W. A sensitivity analysis of electrical resistivity tomography array types using analytical element modeling. Vadose Zone J. 2, 416–423. https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2003.4160 (2003).

Rücker, C., Günther, T. & Spitzer, K. Three-dimensional modelling and inversion of dc resistivity data incorporating topography — I. Modelling, Geophys. J. Int. 166(2), 495–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2006.03010.x (2006).