Abstract

Cement has a substantial environmental impact, particularly carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, which occur mostly during the production stage, as it is anticipated that nearly 4–5% of the world’s total CO2 emissions result from cement production. To address these environmental concerns, future scenarios will require alternative raw materials for clinker production and the usage of supplemental cementitious materials (SCMs). Hence, the current study correspondingly sought to assess the applicability of Laterite soil powder (LSP) for manufacturing High performance Mortar (HPM) and its influence on fresh, hard, and microstructure qualities with varied replacement levels. A series of experiments—including slump flow, compressive strength, chemical resistance, water absorption, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and differential thermal analysis (DTA) were conducted. The results indicate that while a superplasticizer maintained adequate flow, the addition of LSP reduced mortar flowability; for example, a 20% replacement resulted in a 23% decrease in flowability. In contrast, a 10% replacement level did not significantly affect the mechanical or durability properties over all curing periods. A one-way ANOVA (p = 0.62) confirmed that there was no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) in compressive strength between the control mix LSP-0 and the LSP-10 mix. Furthermore, FTIR analysis indicated that a 10% LSP content exerted only a modest influence on the hydration products, as the wavenumbers, curves, peaks, and valleys observed in the spectra of the LSP-0 and LSP-10 mortar samples were nearly identical. In general, analysis of various properties indicates that a 10% LSP replacement is optimal, as it maintains performance without significant adverse effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introductions

One of the main causes of climate change and global warming resulting from carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions is cement production1, which has grown to be the third-largest source of anthropogenic CO2 emissions after land use changes and the burning of fossil fuels1,2,3. As estimated by Baldusco et al.4, 13% of global anthropogenic CO2 emissions are attributable to the cement sector, and 90% of these emissions are connected to the manufacturing of clinker, with the decarbonization of calcium carbonate accounting for half of these emissions4. Sousa and Bogas2 asserted that since 1950, its output has increased thirty times, and since 1990, it has increased almost four times. High temperatures (1450–1550 °C) are necessary for this energy-intensive material3,5. Therefore, in the future, scenarios will require the usage of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), other new types of low CO2 emission binders, and alternative raw materials to produce clinker due to environmental issues related to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change4,6.

Over the past several decades, numerous studies have investigated the use of alternative materials in concrete production. Many of these novel materials have been selected for their ready availability7,8 while others, particularly waste-derived materials, offer an opportunity to repurpose otherwise discarded resources9,10. In addition, the integration of recycled and solid waste materials in concrete aligns with efforts to address environmental challenges and reduce energy consumption11,12. Motivated by these primary factors, the current study seeks to further explore sustainable and resource-efficient alternatives for concrete production. According to Santha Kumar et al.13, laterite soil is extensively spread and may be found on all continents. It is also common in Sub-Saharan African nations14. Buchanan first used the term ‘laterite’ in academic literature to characterize the soil type of the hilly area of Malabar, India13,15. It is the leached remnant of the natural process of laterization in tropical and subtropical areas13.

A number of investigation were conducted on laterite soil for the production of bricks16,17, as an alternate aggregate for the production of mortar and concrete18,19, as an alternate material for geopolymer production20,21, and for road construction purposes22.

As per Santha Kumar et al.13, because of their advantages on both a social and ecological level, laterite soil-based bricks are widely utilized as walling components. The manufacturing procedures have an impact on these bricks’ performance17. Higher strength bricks made with laterite soil and burnt at 550 °C are produced than those stabilized with cement and lime23. But compared to utilizing cement alone as a stabilizer, mixing laterite soil with natural pozzolana and cement improves the hardened performance of the bricks.

In certain cases where achieving a high level of performance is not essential, laterite soil can be utilized as a replacement for sand in the manufacturing of mortar and concrete, thereby conserving natural sand resources13. The effects of using laterite soil on concrete properties were investigated by Yaragal et al.19. They discovered that the gradation of laterite soil significantly influenced the fresh and mechanical properties of concrete. Using laterite soil of a finer grade in mortar increased the strength characteristics of the mortar. When Udoeyo et al.24 looked at how laterite sand affected the characteristics of concrete, they discovered that because laterite soil has bigger particle sizes, the workability of concrete rose as the percentage of laterite soil increased. As more laterite soil was added, the strength of the concrete declined; but, as the concrete aged, it showed an increase in strength.

Although laterite soil has been widely investigated for various applications—including as an alternative aggregate, in road construction, and as a raw material in brick production—the exploration of laterite soil powder (LSP) as a substitute for ordinary cement remains notably limited. Most existing studies have concentrated on its use as an alternative aggregate in mortar and concrete, leaving a significant gap regarding its potential to function as a cement replacement. Given the environmental and economic incentives to develop sustainable construction materials, a thorough investigation into the mechanical properties, durability, and microstructural behavior of LSP as a cement substitute is both timely and necessary. This study aims to fill that gap by evaluating the feasibility of incorporating LSP into high-performance mortar (HPM), thereby providing critical insights into its practical applications and contributing to the advancement of sustainable construction practices.

In light of this, this study examined how LSP affected the microstructure, fresh, and hard characteristics of HPM at different replacement amounts. A total of four mortar mixes were prepared using water-binder (OPC + LSP) in a ratio of 0.32. To ensure proper flowability for all the mixtures, a superplasticizer had to be utilized because a very low water-binder ratio was being used. Numerous tests were performed including slump flow, compressive strength, chemical resistance, water absorption, Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA), and Differential thermal analysis (DTA).

Materials and methods

LSP Production

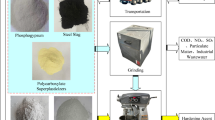

Several production steps were followed throughout the manufacture of LSP. The initial phase was acquiring a typical raw material from Bahirdar, Amhara, Ethiopia. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the dried material was manually ground using a hammer until it reached a fineness that allowed it to pass through a 75 µm sieve. The ground material was subsequently sieved, separating the fine particles (those passing through the 75 µm sieve) from the coarser fractions. Only the fine powder was used as LSP to partially replace OPC in the production of HPM.

Materials used

The materials used for the production of HPM in this investigation were Ordinary Portland cement (OPC), fine aggregates, Laterite soil powder (LSP), Water reducing admixture (Superplasticizer), and water.

Binders

The binding mediums used in this study were OPC strength class of 42.5N ‘Dangotie’ and LSP (Fig. 2). The OPC cement corresponds to ASTM Type I general-purpose. Before a detailed investigation, the LSP underwent a number of physical and chemical analyses.

The physical and chemical properties of Laterite soil powder (LSP) are presented in Table 1. The LSP had a density of 2.56 g/cm3 and a surface area of 506.8 m2/g. Even though it has a lower density compared to the OPC, it has quite a higher surface area or better fineness. The primary oxides present in LSP included SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3, CaO, MgO, Na2O, and K2O, with SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3 constituting over 80% of the total mass. The chemical analysis indicated that the total oxide composition of Iron oxide (Fe2O3 = 15.48%), aluminum oxide (Al2O3 = 18.28%), and silicon dioxide (SiO2 = 50.54%) accounted for 84.8% of the total composition. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the major compounds found in laterite soil consist of these compounds, comprising predominantly over 70% of the total composition of oxide compounds. In certain cases, the percentage can even reach approximately 92 ± 5%25,26,27,28,29. This can satisfy the minimum requirements for class N natural pozzolana based on ASTM C61830. As a result, LSP has the potential to be employed as SCM for partial cement substitution. In addition, some minor components, such as K2O, MgO, Na2O, and CaO, were also present in LSP as inferred from Table 1.

Fine aggregate

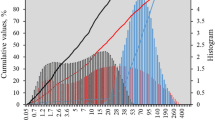

The fine aggregate used in all mortar mixes was natural/river sand sourced from Lalibela town, Amhara, Ethiopia. Multiple investigations were conducted to verify the suitability of the sand. As shown in Fig. 3, the sieve analysis indicates that the fine aggregate used in the study is within the recommended upper and lower ASTM limit32. Table 2 also presents all the physical properties of fine aggregate are within their corresponding limit as specified in ASTM standards.

Superplasticizer

Superplasticizers can help to modify the mortar matrix. Therefore, to produce HPM, adding chemical admixtures during mixing is endorsed. It can lower the amount of water used and improve the workability of mortar without compromising strength. Therefore, a chemical admixture (Muraplast SP1: high range water-reduction superplasticizer) that meets ASTM C494 standards was employed.

Experimental setup

Fresh properties

In determining the consistency and setting time, ASTM C18733, and ASTM C19134 standard procedures were followed respectively. The workability of the LSP mortar was studied using the slump flow test following ASTM C143735. Mortar flow values were tested while altering the LSP replacement level to the volume of OPC (0, 10, 20, and 25%).

Hardened properties

ASTM C109 provides a standard for compression tests to determine the compressive strength of hydraulic cement and mortars36. The test was performed using a standard testing machine with a capacity of 2000 kN, at a loading rate of 6 N/mm2 per second for all the mortar samples. The evaluation of chemical resistance was also conducted by measuring the reduction in compressive strength. During this test, the specimens underwent initial curing for 28 and 56 days in solutions of 5% hydrochloric acid (HCl) and 20% sodium sulfate (Na2SO4). This was done to examine the impact of chloride and sulfate on the mortar. All the specimens were cleaned using a brush, to remove any loose material before testing. The strength activity index (SAI) of the LSP mortar was determined following the guidelines outlined in ASTM C61830. For measuring the water absorption, apparent density, and the Volume of permeable voids (VPV) of the hardened mortar samples ASTM C642 standard test method was adopted37.

Microstructure

Fourier transformed infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) FTIR studies were done to find the functional groups in the mortar mass and their significant impact on the properties and its internal behavior. To conduct FTIR analysis, specimens were taken from the middle of the mortar following the compressive strength test and immersed in ethanol for three days to stop the hydration process. They were then oven dried for 24 h before grinding and sieving through a 75 µm sieve. FTIR investigation was done for 0%, 10%, 20%, and 25% samples at 28 days of curing age.

Thermogravimetric (TGA) and Deferential thermal analysis (DTA) For this assessment, prior to recording, the ground LSP mortar sample weighing 10 mg was placed in a platinum pan, while an empty platinum pan served as the reference. The powdered sample was dried for a duration of 40 min to remove any residual moisture. Then the mass of powder was recorded and the furnace chamber was stabilized for another 30 min to reach an isothermal and stable condition at 25 °C. The tests started with temperature increased at a rate of 10 °C per minute up to 900 °C.

Mix design and specimen preparations

Table 3 shows the respective mix proportion results for the control and LSP mortars. There are currently no established standard operating procedures for HPM mix design that are precisely appropriate for HPM manufacturing. In this study, a streamlined mix design process was developed by integrating American Concrete Institute (ACI) methodologies with current HPM literature. To fulfill the criterion for the flowability of high-strength mortar, the control mix was designed using the absolute volume approach recommended by the ACI38. Four (0%, 10%, 20%, and 25%) mixes were prepared in order to study the application of LSP in HPM. In order to acquire the desired strength, the overall ratio of water to binder (W/B) was set at 0.32.

A mechanical mixer was used to uniformly mix the ingredients of each mix. To get a homogeneous dry mix, the components were first put into the mixer, which was then turned on at a low speed for two minutes. After achieving a homogenous dry mixture, the material was progressively dispersed by adding mixing water and superplasticizer, and mixing was carried out at a moderate pace for five minutes. Then specimens were made in cubic molds (50 × 50 × 50 mm) for mechanical and durability testing. Finally, the specimens were de-molded and allowed to cure at room temperature after a 24-h period.

Results and discussion

Fresh mortar properties

Setting time

The graph in Fig. 4 illustrates the setting time of the LSP mixtures at various replacement levels. The data clearly indicates that the inclusion of LSP in the mix had minimal impact on the initial setting time. According to ASTM C15039, the initial setting time should be at least 45 min, and all the results obtained in this study comply with this standard. Specifically, at 10%, 20%, and 25% replacement levels, the initial setting time increased by only 2, 5, and 7 min, respectively, compared to the reference. Given these small variations, it can be concluded that LSP replacement does not cause a significant difference in the initial setting time. However, a slight linear increase in both the initial and final setting times was observed as the LSP replacement level increased. Despite this trend, all mixtures remained within the acceptable limits of ASTM C15039, which requires an initial setting time of at least 45 min and a final setting time not exceeding 375 min. These findings suggest that LSP-modified mixtures can maintain setting time characteristics, ensuring compliance with standard requirements.

Consistency

The consistency of LSP blended cement paste test were carried out in order to examine the relative mobility of a freshly mixed cement paste and its capacity to flow when the water requirements of pastes alter owing to LSP replacements. As demonstrated in Fig. 5, higher levels of LSP replacement result in an increased water requirement to maintain a standard consistency, suggesting, the LSP requires more water content than OPC. This is mostly owing to the increased surface area of LSP (506.8 m2/g) over OPC (340 m2/g). Despite using more water than the reference mortar, the results are within the acceptable range. The normal consistency of OPC based on ASTM C187 falls between 26 to 33%33.

Workability

Figure 5 also illustrates the effect of LSP on the flowability of mortar with a variety of combinations. LSP has a substantial impact on the flow of mortar mixtures. Figure 5 makes it evident that adding LSP to the HPM mixes decreases flowability. The flow results decreased from 145 to 111 mm in the control mortar (LSP-0) and the mortar with 20% LSP replacement (LSP-20), which is almost a 24% reduction in flow. A linear reduction was noted as the replacement amount increased. It is also worth mentioning that an R2 of 0.978 is strongly associated with the flow result and replacement level. Nonetheless, in spite of the lower water-to-binder ratio used, the flow result for all the mixture were found to be acceptable. This is mainly attributed to the effect of high range water reducing superplasticizer used in the mix to compensate for the lower water-to-cement ratio40,41. Several researchers also have used these types of admixtures to achieve an anticipated flowability42,43.

Hardened mortar properties

Apparent density

Figure 6 displays the density evolution of LSP mortars at different curing periods. As the curing period prolonged, the mortar mixtures’ density increased, as expected. For example, the apparent density of the 25% LSP-replaced mortar mixture rose from 2038 kg/m3 to 3000 kg/m3 when the curing period extended from 7th to 28 days. Moreover, the decrease in density is minimal when the LSP replacement level is up to 10%. This is mostly because materials with higher specific surface area values have a tendency to fill pores in concrete, which causes it to densify and compact31. However, it is clear that a higher replacement level of LSP brutally affects the density of mortar. This slight decrease in density can be attributed to the lower density of LSP, which is approximately 2.56 g/cm3, about 18.7% lower than that of OPC44. The other explanations might be the porous morphology and voids present in this material13,45. According to Marto et al.28, the discontinuous structure of laterite soil made voids and porosity 325 more noticeable in the absence of hydration products.

Compressive strength

Figure 7 depicts the influence of LSP on the compressive strength development of mortar. It was determined that the LSP concentration had little impact on the compressive strength of mortar up to 20%. However, the compressive strength development reduced linearly (R2 = 0.999) with the increase in LSP content. The specimens with a 25% LSP content exhibited the most significant decrease in compressive strength throughout all curing periods. This reduction in strength aligns with expectations, as it correlates with the decrease in density resulting from the higher LSP content.

Despite this trend, the LSP mortar has a typical propensity for compressive strength to gain strength over time. Notably, among LSP mortar, the 10% LSP mix achieved the highest compressive strength of 70.93 MPa after 56 days of curing, while the 25% LSP mix recorded the lowest value of 19.6 MPa on the first day. A one-way ANOVA (p = 0.62) confirmed that there was no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) in compressive strength between the control (0% LSP) and the 10% LSP mix. These findings support the conclusion that a 10% replacement level does not substantially reduce the mechanical performance of the mortar, which indicates that it is the optimal replacement level. Furthermore, even at a 20% LSP replacement, the reduction in compressive strength remained modest, particularly at later curing ages, highlighting the potential viability of moderate LSP incorporation in cementitious systems.

Strength activity index (SAI)

The pozzolanic properties of LSP were evaluated to assess its effectiveness as an active addition, and this was done by calculating the SAI. The SAI represents the ratio between the strength of the LSP mortar and the strength of the reference mortar46. In this investigation, the SAI index was determined in accordance with ASTM C61830. To meet the desired performance criteria, it is expected that the SAI of the tested material should be equal to or greater than 0.75 after 28 days of curing when compared to the OPC mix30,47.

Figure 8 displayed the compressive strength test results for the mixtures combining different amounts of LSP after 28 days of curing. The performance of these composites (LSP) was compared to that of a control mortar made solely of OPC. Notably, LSP-10 exhibited the highest compressive strength, with only a minimal reduction of 7.3% compared to the control mix. Besides, all the tested mixes displayed a significant SAI value, surpassing the requirements outlined in ASTM C61830. Despite a decreasing trend in the SAI values as the replacement level of LSP increases, the fact that all the tested mixes still exceed the specified requirements suggests that even at higher replacement levels, the composites (LSP mixture) remain effective and meet the desired performance criteria.

Chemical resistance

Cubes were submerged in 5% hydrochloric acid (HCl) and 20% sodium sulphate (Na2SO4) for 28 and 56 days to evaluate the effect of chloride and sulfate in the mortar. After removing the cubes from the acid solution and sodium sulphate immersion, a trivial change in color is noted as the immersion period increases, as illustrated in Fig. 9. For HCl and Na2SO4 solutions, the surface of the mortar was reddish (rusty) and white, respectively. Rust-like staining can occur in the HCl environment when iron compounds in raw materials react with the acidic medium. Meanwhile, in the Na₂SO₄ environment, white efflorescence is typically attributed to sulfate-based reaction products forming on the surface. These color changes align with findings from references48 and49, which observed similar phenomena under comparable chemical exposures. Liu et al.48 investigated the effect of acidic sulfate solutions on concrete performance and observed a whitish precipitate marking the penetration depth of chloride ions. This precipitate was visible on the surface, mirroring the whitish discoloration noted in this investigation. Additionally, Amin et al.49 examined the impact of sulphate solution on various concrete properties and reported reddish discoloration as well as physical deterioration (e.g., peeling, cracks) on the specimen surfaces. Although this study attributed the reddish coloration primarily to HCl exposure, the underlying principle is consistent that chemical interactions between aggressive ions and cement paste can induce noticeable color changes.

No visible signs of cracking or spalling were observed on any of the specimens until they were cured for 28 days in both solutions. However, after the 56th day, noticeable spalling became evident, particularly in the specimens exposed to HCl solution. In the case of sulfate-cured LSP mortar specimens, a thin layer of white efflorescence began forming. As the curing period progressed, this layer got somewhat thicker and more noticeable. These observations suggest that the HCl solution may have a negative impact on the long-term durability of the LSP mortar, as it appears to be more susceptible to spalling. The white efflorescence observed on the sulfate-cured specimens may also be an indication of degradation (Fig. 9c, d).

In a study conducted by Aye et al.50, the resistance of Portland and high alumina cement mortars to sulfate attack was assessed. The evaluation involved visual inspection and the measurement of changes in surface hardness and weight of the specimens. Their investigation also showed the sulfate solution has a similar effect on the surface of mortar50. Chemical sulfate attack on concrete or mortar primarily occurs due to the presence of C–H, which acts as a precursor for gypsum formation51,52. Sulfate ions interact with C–H, resulting in the formation of gypsum. Additionally, in line with the findings of Aye et al.50, it has been observed that gypsum, formed as a result of sulfate attack on concrete or mortar, can further contribute to the formation of ettringite. This occurs through reactions with monosulfate and other alumina-bearing phases such as C4AH13 and unhydrated C3A. Numerous studies53,54,55 have concurred that chemical sulfate attack leads to significant consequences, including expansion, cracking, softening, and loss of adhesion within the cement paste. These negative impacts are mostly due to the formation of gypsum and ettringite50,56.

Figure 10 depicted the compressive strength less due to sulphate and acid attack. In all the percentage replacement levels the acid solution has an extreme effect on the compressive strength development. All the mixture has higher compressive strength loss. At 25% of replacement, there is a maximum strength loss that reaches 5.07 MPa after 56 days. Studies showed acid aggression in mortar results in the dissolution of calcium hydroxide (C–H) and calcium-hydrated silica gel (C–S–H)57. Whereas, for the sulfate solution the maximum loss occurred at these replacement level (25%) on the corresponding curing ages with a value of 4.18 MPa. Furthermore, it was observed that the chemical resistance of the mortar deteriorated with higher percentages of LSP substitution. In any case, compared to LSP-0, the two solutions’ effects were shown to be non-significant for LSP-10.

Water absorption and voids

Figure 11 portrays the association between different LSP replacement amounts and water absorption and VPV. The findings indicate that an increase in the LSP content corresponded to an increase in water absorption of the mortar specimens. This can be attributed to the porous characteristics of LSP particles, which have a high capacity for water absorption58,59. The more LSP there is in the mixture, the more noticeable this impact gets. The results showed a significant linear association (R2 = 0.945). The same pattern was also noted for the VPV. Higher LSP replacement dramatically increases the overall volume of voids in the mortar, affecting its durability and mechanical qualities. The increase in voids with higher LSP content can be explained by two primary factors. First, LSP particles often exhibit an inherently porous structure, meaning they can introduce additional microvoids into the cement matrix when used in larger quantities. Second, replacing OPC with LSP reduces the amount of clinker available for hydration, potentially leading to fewer or thinner hydration products that fill pore spaces. Consequently, there is less dense packing and a higher volume of interconnected pores. As LSP content rises, these effects become more pronounced, thereby elevating water absorption and VPV. The maximum water absorption (6.4%) result is obtained with 25% LSP replacement, representing an increase of approximately 38% compared to the reference mix with a water absorption value of 3.8%. At a 10% LSP concentration, the water absorption reached its lowest point at 4.3%, experiencing only a modest increase of 13% compared to the reference mix without LSP. Overall, the LSP mortar samples’ water absorption is below the 10% permitted threshold. An increased water absorption is related to lower porosity and higher compressive strength60.

Microstructure characteristics

The microstructure of concrete/mortar is characterized by its heterogeneous nature, comprising three essential components: the pore structure, cement paste, and the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) flanked by the paste and aggregates (both fine and coarse)61,62. By focusing on enhancing these three components, we can attain significant enhancements in the mechanical strength and durability of mortar62. Microstructural investigation of LSP mortar was done based on thermal analysis method including, TGA and DTA, and FTIR.

Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR investigations aided in understanding the development of internal mass, the contribution of internal atoms, the identification of functional groups and their bond strength, on top of the polarity of the bond and its effect on mechanical characteristics63. Figure 12 depicts the outcomes of an FTIR analysis conducted on mortar samples with varying concentrations of LSP (0%, 10%, 20%, and 25%) following a 28-day curing period.

The major peaks observed around 3750, 3400, 2950, 1380, 600–1250, 1100, and 980 cm−1 are highly associated with O–H stretching of Ca(OH)2, Symmetric and asymmetric stretching of water molecules, asymmetric stretching of the C–H bond, stretching of CO3, formation of C–S–H band, ettringite or mono-sulfate, stretching of Si–O bond of C–S–H, respectively. Unreacted LSP particles are traced between 406 and 512 cm−1. The wavenumbers, curves, peaks, and valleys observed in the FTIR spectra of the LSP-0 and LSP-10 mortar samples were almost identical. The FTIR spectra of the LSP-0 and LSP-10 mortar samples displayed striking similarities in terms of wavenumbers, curves, peaks, and valleys. This observation indicates that, although there were minor variations, the presence of a 10% LSP concentration did not significantly affect the formation of hydration products during the development of the hydration process.

The minimal differences at 10% LSP suggest that the key hydration phases—such as C–S–H, Ca(OH)₂, and ettringite—remain largely intact, preserving overall strength and durability. By contrast, at higher replacement levels (20% and 25%), the increased presence of unreacted LSP or shifts in the intensity of peaks (e.g., those associated with Si–O or Al–OH vibrations) can indicate reduced formation or altered structure of hydration products. This partially explains the slight decrease in compressive strength at higher LSP contents.

Numerous researchers looked at LSP’s FTIR properties. Maiti et al.64 it was demonstrated that specific infrared bands corresponded to different molecular vibrations in the laterite soil sample. The authors assigned the following IR bands to respective molecular vibrations; (1) the IR bands observed at 1034, 1008, 911, and 795 cm–1 were associated with the vibrations of Si–O–Fe, Si–O, Al–OH, and Fe–OH, respectively; and (2) the IR bands detected at 642 cm−1 and 465 cm−1 were attributed to the bending of Si–O–Si. Similarly, Eisazadeh et al.65 ascribed the bands at 1105 and 1032 cm−1 to perpendicular and in-plane Si–O stretching, respectively. Oladoja et al.66 also reported the Si–O and Si–O (perpendicular) bands at 787 and 750 cm−1 respectively. The stretching vibrations at approximately 3445 cm−1 and a H–O–H bending band at around 1635 ± 10 cm−1 were ascribed to the adsorbed water65,66,67.

Overall, these FTIR findings imply that moderate LSP replacement (up to 10%) does not adversely affect the essential hydration phases or bond structures in the mortar. At the microstructural level, the presence of LSP can offer a filler effect without substantially affecting C–S–H formation or other crucial hydrates. Hence, FTIR analysis confirms that using 10% LSP can maintain comparable mechanical performance while potentially reducing cement usage, which is beneficial for sustainability and cost-effectiveness in construction applications.

Thermal analyses

To understand the physical and chemical behavior of LSP during decomposition, a thermal analysis was conducted. TGA provided quantitative measurements of the mass changes in the materials associated with thermal degradation. The experiment involved subjecting mortars with varying levels of LSP replacement to a temperature range of 25 °C to 900 °C for analysis, to clearly determine the mass change through a major thermal event. Figure 13 illustrates the weight losses of the materials when exposed up to a temperature of 900 °C for different LSP replacement levels, namely 0%, 10%, and 20%. Through analyzing the weight loss of each sample, we can gain insights into the impact of LSP on the content of C-H and CaCO3 in HPM.

As can be seen in Fig. 13a, the entirely sampled mortar exhibited multi-stage decompositions during the analysis. The first peak which takes place between 50 and 300 °C is associated with the evaporation of free absorbed water, loss from the C–S–H, ettringite, and other hydration products13. Santha Kumar et al.13 in their review confirm that the first TGA peak reflects a combination of moisture release and initial breakdown of hydrates which are the evaporation of free water, partial C–S–H decomposition, and ettringite breakdown that occur predominantly below 300 °C.

The peak observed at approximately 500 °C in the thermogravimetry and differential thermal analysis corresponds to the decomposition of portlandite (C–H), as studies confirm that a C-H decomposition are takes place between 400 and 500 °C45,68. This decomposition process is responsible for the second major thermal event observed in this investigation. Bodian et al.69 observed decomposition of calcium hydroxide in LSP takes place around 522 °C. The other significant peak occurred after 750 °C corresponding to the decarbonation of CO2 from calcium carbonate. Goel and Kalamdhad70 studied the thermal properties of LSP and they observed that CO2 was released due to the breakdown of carbonates, representing an endothermic peak in a range between 750 and 850 OC in their DTG curve.

Corresponding to the C-H decomposition, the highest mass loss was detected for the LSP-20 with a value of 1.2%, indicating that the 20% LSP mixture contains more free calcium hydroxide than either the control (0.78%) or the 10% (0.9%) replacement level, implying that further incorporation of LSP results in increased CH content. On the other hand, the higher mass loss associated with the decomposition of CaCO3 is 4.7% at 10% LSP replacement. In practical terms, this means that in the 10% LSP mix, a greater proportion of the free calcium hydroxide (CH) has reacted with atmospheric CO₂ to form calcium carbonate.

Conclusions

This research involved an experimental investigation of HPM by partially substituting OPC with LSP. The aim was to assess the effects and feasibility of incorporating LSP as a replacement material in the production of HPM. Several fresh, mechanical, durability, and microstructure tests were performed. Based on the result obtained, the following conclusions may be drawn.

-

A key takeaway from the fresh properties is that, although LSP requires more water than OPC to achieve normal consistency, its incorporation does not significantly affect the initial setting time. However, despite maintaining an adequate flow rate, the inclusion of LSP markedly reduces mortar flowability; for instance, a 20% replacement results in a 23% decrease in flowability.

-

Incorporating up to 10% LSP resulted in only a modest reduction in mechanical properties, with the compressive strength of the 10% LSP mix remaining nearly consistent with that of the control—only a difference of less than 5 MPa was observed.

-

Increasing the LSP replacement ratio generally weakens the mortar’s chemical resistance. However, at a 10% replacement level, the impact on chemical resistance is minimal compared to the control mix (0% LSP), suggesting that modest LSP incorporation does not significantly compromise durability against chemical attack.

-

Although water absorption slightly increases with higher LSP content due to the inherent porosity of LSP particles, both the control (LSP-0) and the 10% LSP mixes remain well within the acceptable range. This indicates that even with increases in LSP, the mortar’s ability to limit water absorption is maintained.

-

The FTIR spectra of LSP-0 and LSP-10 mortar samples showed minimal differences in hydration products, indicating that a 10% LSP replacement had little impact on the overall hydration process. This suggests that key hydration phases remain largely intact, thereby preserving the strength and durability of the mortar.

-

Thermal analysis revealed multi-stage decomposition in LSP mortar, particularly in the decomposition of calcium hydroxide (CH). The highest mass loss was observed in the LSP-20 sample (1.2%), compared to the control (0.78%) and the LSP-10 sample (0.9%). This indicates that increasing the LSP replacement level to 20% leads to higher CH content, which can influence both the mechanical properties and durability of the mortar.

Overall, the study demonstrates that producing HPM using LSP as a cementing agent is both feasible and effective. Analysis of various properties indicates that a 10% LSP replacement is optimal, as it maintains performance without significant adverse effects. Increasing the use of these SCMs in concrete and mortar manufacturing not only fosters sustainable, long-term development within the construction industry but also contributes to reducing CO₂ emissions associated with cement production.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Vo, D. H. et al. Effect of water-to-solid ratio on the strength development and cracking performance of alkali-activated fine slag under water curing condition. In Proceedings of 2020 5th International Conference on Green Technology and Sustainable Development, GTSD 2020 268–271 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/GTSD50082.2020.9303136

Sousa, V. & Bogas, J. A. Comparison of energy consumption and carbon emissions from clinker and recycled cement production. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127277 (2021).

Vo, D.-H., Hwang, C.-L., Tran Thi, K.-D., Liao, M.-C. & Yehualaw, M. D. Engineering performance of high-content MgO-alkali-activated slag mortar incorporating fine recycled concrete aggregate and fly ash. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 23(2), 778–789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-020-01171-7 (2021).

Baldusco, R., Nobre, T. R. S., Angulo, S. C., Quarcioni, V. A. & Cincotto, M. A. Dehydration and rehydration of blast furnace slag cement. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 31(8), 04019132. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)mt.1943-5533.0002725 (2019).

Yehualaw, M. D., Hwang, C.-L., Vo, D.-H. & Koyenga, A. Effect of alkali activator concentration on waste brick powder-based ecofriendly mortar cured at ambient temperature. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 23(2), 727–740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-020-01164-6 (2021).

Getachew, E. M., Yifru, B. W., Habtegebreal, B. T. & Yehualaw, M. D. Performance evaluation of mortar with ground and thermo-activated recycled concrete cement. Cogent Eng. 11(1), 2357726. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311916.2024.2357726 (2024).

Danbala, G. K., Quezon, E. T., Science, A. A. & Kebede, G. Calcined termite hill clay powder: As partial cement replacement in calcined termite hill clay powder—As partial cement replacement in production of C-25 grade concrete (2019). https://doi.org/10.12691/ajcea-7-3-2

Vo, D.-H. et al. Mechanical and durability properties of recycled aggregate concrete produced from recycled and natural aggregate blended based on the densified mixture design algorithm method. J. Build. Eng. 35(July (2020)), 102067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.102067 (2021).

Hwang, C. L., Yehualaw, M. D. & Vo, D. H. Utilization of recycled concrete aggregate for high performance alkali activated concrete: Towards a sustainable building solution. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering vol. 690, no. 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/690/1/012001

Yao, S. W. & Wang, C. R. The research on producing recycling cement using waste concrete. 881–883, 1195-1198. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.881-883.1195 (2014).

Qaidi, S. M. A., Dinkha, Y. Z., Haido, J. H., Ali, M. H. & Tayeh, B. A. Engineering properties of sustainable green concrete incorporating eco-friendly aggregate of crumb rubber: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 324, 129251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129251 (2021).

Qaidi, S. M. A. et al. Recycling of mine tailings for the geopolymers production: A systematic review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16, e00933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e00933 (2022).

Santha Kumar, G., Saini, P. K., Deoliya, R., Mishra, A. K. & Negi, S. K. Characterization of laterite soil and its use in construction applications: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 16, 200120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcradv.2022.200120 (2022).

Awoyera, P. O., Dawson, A. R., Thom, N. H. & Akinmusuru, J. O. Suitability of mortars produced using laterite and ceramic wastes: Mechanical and microscale analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 148, 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.05.031 (2017).

Basavana Gowda, S. N., Rajasekaran, C. & Yaragal, S. C. Strength characteristics of laterized mortars using processed laterite. In Sutainable Construction and Building Materials (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3317-0_50

Billong, N., Melo, U. C., Louvet, F. & Njopwouo, D. Properties of compressed lateritic soil stabilized with a burnt clay–lime binder: Effect of mixture components. Constr. Build. Mater. 23(6), 2457–2460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2008.09.017 (2009).

Meukam, P., Jannot, Y., Noumowe, A. & Kofane, T. C. Thermo physical characteristics of economical building materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 18(6), 437–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2004.03.010 (2004).

Akpokodje, E. G. & Hudec, P. P. The influence of petrology and fabric on the engineering properties of concretionary laterite gravel aggregates. Q. J. Eng. Geol. 27(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1144/gsl.Qjegh.1994.027.P1.06 (2022).

Yaragal, S. C., Basavana Gowda, S. N. & Rajasekaran, C. Characterization and performance of processed lateritic fine aggregates in cement mortars and concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 200, 10–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.12.072 (2019).

Lassinantti Gualtieri, M., Romagnoli, M., Pollastri, S. & Gualtieri, A. F. Inorganic polymers from laterite using activation with phosphoric acid and alkaline sodium silicate solution: Mechanical and microstructural properties. Cem. Concr. Res. 67, 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2014.08.010 (2015).

Kaze, C. R. et al. Mechanical and physical properties of inorganic polymer cement made of iron-rich laterite and lateritic clay: A comparative study. Cem. Concr. Res. 140, 106320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106320 (2021).

Li, Y., Tan, Y. Z., Jiang, J. & Xia, C. F. Experimental study on the compressibility of cement improved laterite soil. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012(170), 371–374 (2012).

Mbumbia, L. & de Wilmars, A. M. Behaviour of low-temperature fired laterite bricks under uniaxial compressive loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 16(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0950-0618(01)00035-6 (2002).

Udoeyo, F. F., Iron, U. H. & Odim, O. O. Strength performance of laterized concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 20(10), 1057–1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2005.03.002 (2006).

Abdullah, A. H. et al. Comparison of strength between laterite soil and clay compressed stabilized earth bricks (CSEBs). In MATEC Web of Conferences Vol. 103 01029 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201710301029.

Abdullah, A. H., Nagapan, S., Antonyova, A., Rasiah, K., Yunus, R. & Sohu, S. Strength and absorption rate of compressed stabilized earth bricks (CSEBs) due to different mixture ratios and degree of compaction. In MATEC Web of Conferences vol. 103 01028 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201710301028

Lau, Y.-Y. et al. Degradation of cationic and anionic dyes in coagulation—flocculation process using bi-functionalized silica hybrid with aluminum-ferric as auxiliary agent. RSC Adv. 5(43), 34206–34215. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA01346A (2015).

Marto, A., Latifi, N. & Eisazadeh, A. Effect of non-traditional additives on engineering and microstructural characteristics of laterite soil. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 39(10), 6949–6958. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-014-1286-1 (2014).

Jan, Y.-L. et al. Coupled mechanics, hydraulics and sorption properties of mixtures to evaluate buffer/backfill materials. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 32(8), 789–794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2005.11.002 (2007).

ASTM. ASTM C618-standard specification for coal fly ash and raw or calcined natural pozzolan for use. In Annual Book of ASTM Standards 1–5 (ASTM International, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1520/C0618

Getachew, E. M., Yifru, B. W., Taffese, W. Z. & Yehualaw, M. D. Enhancing mortar properties through thermoactivated recycled concrete cement. Buildings 13(9), 2209. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13092209 (2023).

ASTM. ASTM C136-standard test method for sieve analysis of fine and coarse aggregates. In Annual Book of ASTM Standards 3–7 (ASTM International; 2006) (2006).

ASTM. ASTM C187-Standard test method for normal consistency of hydraulic cement. In Annual Book of ASTM Standards 3 (ASTM International, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1520/C0187-16.

ASTM. ASTM C191-Standard test methods for time of setting of hydraulic cement by vicat needle. In Annual Book of ASTM Standards (ASTM International, 2013).

ASTM. ASTM C1437-standard test method for flow of hydraulic cement mortar. In Annual Book of ASTM Standards 7–8 (ASTM International, 2007) (2007). http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:Standard+Test+Method+for+Flow+of+Hydraulic+Cement+Mortar#0

ASTM. ASTM C109-standard test method for compressive strength of hydraulic cement mortars (Using 2-in. or cube specimens). In Annual Book of ASTM Standards 12 (ASTM International, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1520/C0109_C0109M-21.

ASTM. ASTM C642-standard test method for density, absorption , and voids in hardened concrete. In Annual Book of ASTM Standards 7–9 (ASTM International, 2013).

ACI. ACI-211.1-91 Standard practice for selecting proportions for normal, heavyweight, and mass concrete. ACI manual of concrete practice, part 1: materials and general properties of concrete (The American Concrete Institute, 2009). https://www.concrete.org/store/productdetail.aspx?ItemID=211191&Format=DOWNLOAD&Language=English&Units=US_Units

ASTM. ASTM C150-standard specification for portland cement. annual book of ASTM standards 8 (ASTM International, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1520/C0150-07

Eethar Thanon Dawood, M. R. High strength characteristics of cement mortar reinforced with hybrid fibres. Constr. Build. Mater. 25, 2240–2247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.11.008 (2010).

Fatema, K., Alam, M. & Habib, A. Effect of high range water reducing (superplasticizer) along with early strength admixture on mechanical performance of sand cement block (2023).

Teara, A. & Shu, I. D. Mechanical properties of high strength concrete that replace cement partly by using fly ash and eggshell powder. Phys. Chem. Earth 120, 102942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2020.102942 (2020).

Williamson, R. B. & Rashed, A. I. High strength concrete and mortars in high temperature environments. MRS Proc. 42(1), 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1557/proc-42-295 (2011).

Ohemeng, E. A., Ekolu, S. O., Quainoo, H. & Naghizadeh, A. Economical and eco-friendly masonry mortar containing waste concrete powder as a supplementary cementitious material. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 17(July), e01527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01527 (2022).

Tebabal, M. G., Yifru, B. W., Getachew, E. M. & Yehualaw, M. D. Influence of termite hill soil as a partial cement replacement in mortar production. J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resil. 6(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43065-025-00120-8 (2025).

Altwair, N. M., Johari, M. A. M. & Hashim, S. F. S. Strength activity index and microstructural characteristics of treated palm oil fuel ash. Structure 5(5), 6 (2011).

Kalinowska-Wichrowska, K., Kosior-Kazberuk, M. & Pawluczuk, E. The properties of composites with recycled cement mortar used as a supplementary cementitious material. Materials 13(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13010064 (2019).

Liu, F., You, Z., Xiong, R. & Yang, X. Effects of sodium sulfate attack on concrete incorporated with drying-wetting cycles. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 5393504. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5393504 (2021).

Amin, M. & Bassuoni, M. T. Performance of concrete with blended binders in ammonium-sulphate solution. J. Sustain. Cem.-Based Mater. 7(1), 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650373.2017.1334601 (2018).

Aye, T., Oguchi, C. T. & Takaya, Y. Evaluation of sulfate resistance of Portland and high alumina cement mortars using hardness test. Constr. Build. Mater. 24(6), 1020–1026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2009.11.016 (2010).

Bensted, J., Brough, A. & Page, M. Chemical degradation of concrete. In Durability of Concrete and Cement Composites (2007).

Rahman, M. & Bassuoni, M. Thaumasite sulfate attack on concrete: Mechanisms, influential factors and mitigation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014(73), 652–662 (2014).

Kanaan, D., Soliman, A. M. & Suleiman, A. R. Zero-cement concrete resistance to external sulfate attack: a critical review and future needs. Sustainability. 14(4), 2078 (2022).

Schmidt, T., Lothenbach, B., Romer, M., Neuenschwander, J. & Scrivener, K. Physical and microstructural aspects of sulfate attack on ordinary and limestone blended Portland cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 39(12), 1111–1121 (2009).

Tian, B. & Cohen, M. D. Does gypsum formation during sulfate attack on concrete lead to expansion?. Cem. Concr. Res. 30(1), 117–123 (2000).

Al-Amoudi, O. S. Attack on plain and blended cements exposed to aggressive sulfate environments. Cem. Concr. Compos. 24(3–4), 305–316 (2002).

Umale, S. & Joshi, G. V. Study of effect of chemicals (acid) attack on strength and durability of hardened concrete. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 6(4), 548–552 (2019).

Fadele, O. & Ata, O. Water absorption properties of sawdust lignin stabilised compressed laterite bricks. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 9(e00187), 2018 (2018).

Ismail, S. & Yaacob, Z. Properties of laterite brick reinforced with oil palm empty fruit bunch fibres. Pertan. J. Sci. Technol. 19(1), 33–43 (2011).

Worku, M. A., Taffese, W. Z., Hailemariam, B. Z. & Yehualaw, M. D. Cow dung ash in mortar: An experimental study. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13106218 (2023).

Cristian, D. Concrete microstructure characterization and performance. In Compressive Strength of Concrete (ed. Pavlo, K.) Ch. 2 (IntechOpen, 2020).

Ameer, A. H. Microstructure of concrete. In High Performance Concrete Technology and Applications (eds Salih, Y. & Hayri Baytan, O.) Ch. 1 (IntechOpen, Rijeka, 2016).

Prasad, D. D. & Ravande, K. Fourier transformed—infrared spectroscopy (Ftir) studies on the concrete cement mortar mass made of cent percentage recycled coarse and fine aggregates. Int. J. Adv. Res. Eng. Technol. 12(1), 387–400 (2021).

Maiti, A., Thakur, B. K., Basu, J. K. & De, S. Comparison of treated laterite as arsenic adsorbent from different locations and performance of best filter under field conditions. J. Hazard. Mater. 262, 1176–1186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.06.036 (2013).

Eisazadeh, A., Kassim, K. A. & Nur, H. Characterization of phosphoric acid- and lime-stabilized tropical lateritic clay. Environ. Earth Sci. 63(5), 1057–1066. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-010-0781-2 (2011).

Oladoja, N. A. et al. Insight into the defluoridation efficiency of lateritic soil. Environ. Progress Sustain. Energy 38(4), 13107. https://doi.org/10.1002/ep.13107 (2019).

Goel, G. & Kalamdhad, A. S. Degraded municipal solid waste as partial substitute for manufacturing fired bricks. Constr. Build. Mater. 155, 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.08.067 (2017).

Getachew, E. M., Yifru, B. W. & Yehualaw, M. D. The use of ground recycled concrete cement as an eco-friendly alternative cement material in mortar production. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40996-024-01606-3 (2024).

Bodian, S. et al. Thermo-mechanical behavior of unfired bricks and fired bricks made from a mixture of clay soil and laterite. J. Build. Eng. 18, 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2018.03.014 (2018).

Goel, G. & Kalamdhad, A. S. An investigation on use of paper mill sludge in brick manufacturing. Constr. Build. Mater. 148, 334–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.05.087 (2017).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.N. and M.D.Y.; methodology, M.D.Y.; H.N.; S.A.E.; and E.M.G software, M.D.Y.; H.N and E.M.G.; validation, M.D.Y., and E.M.G.; formal analysis, M.D.Y.; H.N.; S.A.E.; and E.M.G.; investigation, M.D.Y.; H.N., and E.M.G..; data curation, M.D.Y.; H.N., and E.M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D.Y.; S.A.E.; and E.M.G.; writing—review and editing, M.D.Y.; H.N.; S.A.E.; and E.M.G.; visualization, M.D.Y.; H.N.; S.A.E.; and E.M.G.; supervision, M.D.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yehualaw, M.D., Nibret, H., Getachew, E.M. et al. Laterite soil powder as cementing material for the production of high-performance mortar. Sci Rep 15, 15322 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99390-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99390-1