Abstract

In this work, we investigate the stochastic traveling wave solutions for the generalized nonlinear Schrödinger equation under the influence of the Wiener process. It encompasses weak nonlocality related parameters and higher order dispersion with higher order nonlinearity. In order to solve this problem, the improved modified extended tanh function approach is used in conjunction with an appropriate traveling wave transformation to produce new, various, and effective soliton solutions for the proposed model using the computational tool Wolfram Mathematica. We used MATLAB packages to create both 2D and 3D visual representations of the equation in order to better understand its physical meaning. The graphical representations provide useful insights into several aspects of the dynamics of the problem. Our range of solutions includes dark, bright, singular solitons, Jacobi elliptic functions, exponential, periodic, and singular periodic solutions, all of which may be obtained by varying the values of our parameters. This paper represents the first time insertion of stochastic influences into a specified nonlinear wave equation, including impact analysis. Our computer study validates the efficacy and adaptability of our approach in solving a broad range of nonlinear phenomena in the field of mathematical science and many other fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The nonlinear evolution equations (NLEEs) provide accurate descriptions and simulations for nonlinear processes that appear in domains including engineering, physics, computational mathematics, chemistry, and biological sciences1,2,3,4. In the field of nonlinear sciences, nonlinearity plays a vital role in the dynamics of waves. A concentrated research effort has been underway in recent years to solve analytical problems for NLEEs, specifically single-wave solutions. Researchers have created a number of methods, including computer algorithms and analytical and numerical methodologies, to effectively answer NLEEs and offer insights into complex processes. Numerous techniques, including the Hirota bilinear method5, the modified generalized Riccati equation mapping approach6, the IME tanh-function method7,8,9, the modified extended direct algebraic method10,11,12, the Lie symmetry analysis approach13, the extended F- expansion method14, Khater’s algorithm15, Hirota’s method16, the \(\left( \frac{G'}{G},\frac{1}{G}\right) -\)expansion method17, and numerous more, have been developed for analyzing this data (see18,19).

Solitons, which are stable, nondispersive wave phenomena that maintain their structure and speed during propagation, are sometimes referred to as solitary wave solutions20,21. These solutions are unique in that they can maintain their original shape even in the face of specific alterations. They may be found in a wide range of physical systems, such as nonlinear optics22 and water waves23. Solitons are particularly significant for understanding and modeling wave behavior since they often do not exhibit singularities24.

The Schrödinger equation was developed by Erwin Schrödinger in 1925 and formally published in 192625. This equation served as the foundation for his further scientific endeavors. Among the extraordinary nonlinear situations that arise from mathematical modeling, the non-linear Schrödinger equation (NLSE) has a prominent place. Differential equations with deterministic models were widely used in the physical sciences to explore natural processes up to the 1950s. It is apparent, however, that the phenomena of the modern world are not deterministic. However, the evolution of nonlinear dispersive waves is significantly influenced by random fluctuations in the NLSE. They can cause departures from the deterministic predictions of the equation because they are caused by noise or errors in the original circumstances or by outside causes. Recent developments in soliton solutions and techniques relevant to stochastic optical communication systems are not covered in the current literature survey. A more thorough context would be provided by including research like Secer et al.’s study on stochastic pure-cubic optical solitons26, Kamel et al.’s analysis of soliton solutions in nonlinear optical media27, and Alkhidhr’s investigation of stochastic solutions for nonlinear Schrödinger equations in optical fiber communications28. Furthermore, the study by Alzahrani et al. on soliton solutions of the stochastic perturbed Schrödinger-Hirota equation29 and recent work in30 on stochastic optical solutions for the (2+1)-dimensional NLSE provide important insights into contemporary approaches. Wavelet-based techniques have shown promise in capturing the dynamics of complex systems with higher-order dispersion and nonlocal interactions. To illustrate its resilience to such complexity, Zhang et al. (2017) created a high-order wavelet integral collocation approach for nonlinear boundary value problems31. Similarly, Gunzburger et al. (2014) highlighted the accuracy and versatility of an adaptive wavelet stochastic collocation approach designed for irregular solutions of stochastic partial differential equations32. These works would highlight the originality of the suggested solutions in the context of stochastic nonlinear Schrödinger equations and offer a more thorough knowledge of wavelet-based techniques if they were included in the literature review31,33,34.

Existing research has looked extensively at deterministic wave equations and their solutions, such as solitons, periodic waves, and localized structures in nonlinear systems. However, most research focuses on idealized systems and ignores the influence of noise. Researchers have investigated how random perturbations impact wave dynamics using stochastic partial differential equations (SPDEs), but extensive analytical and numerical investigations on the equation in this study are lacking. Theoretical and practical benefits of studying these fluctuations include improved prediction and control of wave dynamics in real-world applications, as well as a deeper knowledge of wave statistical behavior in complex systems. Numerous methods have been developed to examine and predict these fluctuations, including numerical simulations and stochastic analysis, which offer important insights into how these fluctuations affect wave propagation35,36. While previous research has focused on deterministic solutions, the impact of stochastic noise on wave propagation for the nonlinear system under consideration in this study is not well known. There is a paucity of systematic research into how varied noise levels affect wave stability, form, and evolution. Furthermore, present numerical models do not give enough information on the transition from deterministic to stochastic wave behaviors under different noise levels.

Motivation and novelty of this study

The need to account for random effects in the analysis, prediction, modeling, and simulation of physical systems is now widely accepted. Random variations throughout time are incorporated into stochastic models37. Thermal fluctuations and spontaneous emissions may be simulated using stochastic NLSE. Many authors examined the existence and uniqueness of stochastic nonlinear stochastic exponential smoothing with additive or multiplicative noise. Stochastic NLSE is also analyzed by numerical methods38,39. SPDEs are expansions of classical partial differential equations that include randomness, generally via stochastic processes such as Wiener noise, to characterize uncertain systems. They are commonly used in physics, finance, and engineering to describe phenomena such as turbulent fluid flow, quantum field fluctuations, and financial market dynamics40,41. To close the gap in the literature, this work incorporates a stochastic factor into the governing wave equation and thoroughly investigates its implications. The paper investigates how varying noise levels affect wave stability, localization, and energy distribution using both analytical and numerical modeling approaches. The process entails solving the SPDE under various noise settings and displaying the results with 3D and 2D charts to identify significant patterns and trends.

Stochastic generalized NLSE description

This research represents a novel search for the exact solutions for the stochastic generalized NLSE. According to42, an overall NLSE affects how light waves propagate by including both fourth-order dispersion effects and Kerr nonlinearity which can be read as:

As explained in42, the model indicated above has to be improved by adding a new element to take into consideration the impact of weak nonlocality.

and adding the noise effect, Eq. (2) becomes:

where the time and spatial dimensions are represented, respectively, by the variables t and x in this configuration. \(\mathcal {R}(x,t)\) is used to represent the complicated amplitude of the electric field. The 4th-order dispersion is described by the coefficient \(\eta _1\), while the cubic non-linearity coefficient is shown by \(\eta _2\). The consideration of nonlocal effects becomes more crucial when addressing the propagation of tiny wavelengths in various optical transmission sub-materials. In this case, the Kerr nonlinearity is encapsulated by the phrase \(\left| \mathcal {R}\right| ^2 \mathcal {R}\), whereas the influence of 4th-order dispersion is described by the term \(\mathcal {R}_{xxxx}\). Additionally, the presence of weak nonlinearity is indicated by the phrase \(\mathcal {R} \left( \left| \mathcal {R}\right| ^2\right) _{xx}\). In recent times, the aforementioned model has been used to study the localization of optical pulses within guided wave structures, especially when a quasiperiodic linear component is present43. Where W(t) denotes the Wiener process function and \(\frac{ dW}{dt}\) denotes the white noise but \(\varrho\) denotes the white noise intensity. The Wiener process function has the following properties44,45:

-

i.

For \(t \ge 0,\ W(t)\) has continuous trajectories.

-

ii.

For \(s < t,\ W(t)-W(s)\) has independent increments.

-

iii.

\(W(t)-W(s)\) has a normal distribution with variance\(\ = t-s\) and mean\(\ = 0\).

Adding noise to Eq. (2) results in a SPDE with a Wiener process (dW). This adjustment adjusts for random variations in physical systems caused by external disturbances, measurement noise, or inherent system variability. The inclusion of the parameter \(\varrho \mathcal {R}\ dW/dt\) improves the equation’s ability to predict real-world occurrences when perfect deterministic behavior is insufficient. This method is critical for studying the stability and resilience of wave propagation, soliton dynamics, and other nonlinear systems in the presence of randomness. In addition, the updated Eq. () has a wide range of practical applications, including optical fiber communications, where noise represents the effect of amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) on signal integrity. In Bose-Einstein condensates, it represents quantum fluctuations that impact particle interactions. Similarly, in fluid and plasma physics, stochastic concepts assist in understanding wave turbulence and instabilities. By adding noise, researchers may investigate how randomness impacts system evolution, forecast long-term behavior, and devise ways for reducing noise-induced distortions in practical applications.

Thus, the search for soliton solutions in the aforementioned models serves as our primary source of inspiration. We want to do this by utilizing the improved modified extended (IME) tanh function approach, a freshly developed and trustworthy technology. The approach has the potential to resolve unresolved issues from earlier research7,8,46. Finding analytical solutions for a particular generalized nonlinear Schrödinger problem is the primary goal of the improved modified extended tanh-function approach. Simplifying the equation while maintaining its essential features is its main goal. The process of standardization facilitates the identification of precise solutions, providing important information about the behavior of the system that the nonlinear partial differential equation (NLPDE) describes36,47. For the purpose of regulating atmospheric gravity waves, preserving wave stability, and avoiding dispersion, the found solitons are vital to atmospheric study. Understanding the patterns of global air circulation and how they impact weather events requires the preservation of long-range coherent wave structures8.

The success of the suggested approach in solving particular problems and their capacity to yield precise answers define how successful they are compared to existing methods; computing efficiency, generality, and ease of implementation are all significant considerations in this assessment.

The outline of the paper goes like this: The soliton theory and NLSEs history are introduced in general and given a theoretical foundation in “Introduction” section; the suggested model to be studied and its practical applications are briefly described in “Stochastic generalized NLSE description” section; and the main characteristics of the IME tanh function approach are presented in “The IME tanh function approach” section. In “Novel stochastic soliton solutions extraction” section, we will do a thorough symbolic computation using Wolfram Mathematica®, beginning with the non-linear equation itself, to arrive at a few families of exact stochastic solutions. One should establish some constraint conditions in order to prove the existence of some approved solutions. Understanding the physical importance of this non-linear system can be aided by the obtained data. Various of the retrieved solutions are illustrated using 2D, 3D, and contour representations in “Graphical and physical interpretation for the influence of noise onthe extracted solutions” section. A few findings are presented at the end of “Conclusions” section.

The IME tanh function approach

In this section, we present the salient features of the IME tanh function approach, which will be used in this manuscript as well as a comparative analysis with alternative approaches.

Mathematical procedures of the IME tanh function approach

By beginning to think about the subsequent NLPDE9,48:

here \(\mathcal {K}\) denotes a polynomial of its argument \(\Psi (x,t)\) in addition to their corresponding partial differentiation.

Algorithm (1): The upcoming transformation shall be applied to convert the NLPDE in Eq. (4) to a non-linear ordinary differential equation (NLODE):

where \(\mathcal {Z}\) represents the solution, while \(\alpha\) and \(\nu\) are unknown constants which shall be evaluated later on in the work’s procedures. Next, we insert Eq. (5) into Eq. (4). Thus, we are able to construct the required NLODE as described below:

Algorithm (2): The scheme defines the solution’s form of Eq. (6) to be:

where \(\mathfrak {A}_i\) and \(\mathfrak {B}_i~ (i= 1, 2,...,{\mathbb {N}})\) represent some constant parameters of the solution equation which will be calculated, supplying the requirement that \(\mathfrak {A}_{\mathbb {N}}\) and \(\mathfrak {B}_{\mathbb {N}}\) cannot both be zero at the same time.

Algorithm (3): The homogeneous balancing principle (HBP) is implemented in Eq. (6) to estimate the positive integer \(\mathbb {N}\). In addition the function \(\mathcal {G}(\zeta )\) fulfils the subsequent requirement:

while \(\tau _l~ ( l=0,1,2,3,4)\) are real-valued constants which will help us in finding possible cases of solutions.

The parameters in the supplied differential equation in (8) are determined based on the wave system’s physical properties, ensuring that the generated solutions match the intended wave patterns. \(\tau _0,\tau _1,\tau _2,\tau _3,\) and \(\tau _4\) determine the kind of wave solution (e.g., solitary waves, periodic waves, or localized structures). Their selection is often influenced by system restrictions, dispersion relations, and stability parameters, which help decide whether the wave retains its shape over time or evolves into a different shape.

Eq. (8) has the following general solutions with different possible values of \(\tau _0,\tau _1,\tau _2,\tau _3\) and \(\tau _4\):

Family 1: When \(\tau _0=~\tau _1=~\tau _3=0\), the following solutions are raised:

These solutions are localized and describe soliton-like structures. The sech function corresponds to bright solitons, while the sec function represents singular periodic structures. Family 2: When \(\tau _1=\tau _3=0\), the following solutions are raised:

where \(\mu\) is the modulus of the Jacobi elliptic functions, \(0 \le \mu \le 1\) and \(\epsilon =\pm 1\). These solutions describe periodic and quasi-periodic wave structures, in addition to the dark solitons.

Family 3: When \(\tau _0=\tau _1 = \tau _4 = 0\) the following solution is raised:

These solutions represent double-hyperbolic solitons or bistable states, often found in nonlinear wave equations with external forcing.

Family 4: When \(\tau _3=~\tau _4=0\), the following solution is raised:

These solutions describe exponentially growing and oscillatory modes.

By extending these solutions to stochastic optical models, we gain valuable insights into noise-driven instabilities, soliton interactions, and optical signal processing in nonlinear optical media. Algorithm (4): We can raise a polynomial in \(\mathcal {G}(\zeta )\) by inserting a solution that appears to be stated in Eq. (7) and Eq. (8) into Eq. (6). The process of equalizing the coefficients of \(\mathcal {G}^i(\zeta )\), (\(i=0,\pm 1,\pm 2,...\)), to zero produces a family of non-linear algebraic equations (NLAEs) that may be tackled and solved using Wolfram Mathematica®. Consequently, there are several precise solutions for the traveling wave in Eq. (4) that we may acquire.

A comparative analysis with alternative approaches

In comparison to Hirota’s technique49 and the variational iteration method (VIM)50, the IME tanh-function approach has significant benefits in terms of accuracy, computing efficiency, and wider applicability. The IME tanh-function technique offers a more straightforward and methodical means of obtaining accurate answers with less algebraic complexity than Hirota’s method, which mostly depends on bilinear transformations and necessitates costly symbolic calculations. Similarly, VIM is computationally costly and frequently requires numerous correction functionals and convergence monitoring, even though it iteratively improves approximations and might be useful for nonlinear situations. On the other hand, the IME tanh-function method improves efficiency by achieving faster convergence with fewer repetitions. Furthermore, numerical comparisons show that it retains excellent accuracy, as evidenced by a more stable solution structure and smaller residual errors. Additionally, its versatility encompasses a wider range of nonlinear partial differential equations, such as integrable and non-integrable systems, where conventional approaches could encounter difficulties with singularities or divergence. As a strong substitute for current techniques, the IME tanh-function approach offers a balance between accuracy, efficiency, and broad application.

Novel stochastic soliton solutions extraction

This section makes use of the IME tanh function approach to build every potential solution for Eq. (3). For this aim, we suppose the following wave transformation:

where \(\mathcal {H}(\zeta )\) is the amplitude of the complex-enveloped solution, \(\beta\) denotes the wave number, \(\omega\) is the frequency shift, while \(\varrho\) represents the intensity of the white noise W(t).

Using the aforementioned transformation in Eq. (9) and its corresponding derivatives into Eq. (3) and by separating the real and imaginary components, one can find the real part as:

and the imaginary part as

By integrating Eq. (11) with respect to \(\zeta\) with considering the integration constant to be zero, then plugging what we obtained into Eq. (10), one can find the following ODE:

Thus, by applying the HBP presented in Section 3 between \(\mathcal {H}^{(4)}\) and \(\mathcal {H} \left( \mathcal {H}'\right) ^2\), one can find that \(\mathbb {N}=1\). After that, one can build up the form of the exact solution for Eq. (3) as read below:

Eq. (12) yields a polynomial in \(\mathcal {G}(\zeta )\) when the restriction in Eq. (8) is substituted with the solution form in Eq. (13). We have a system of NLAEs when we set the sum of all terms with the same powers to zero. We can solve these equations using Wolfram Mathematica® to create the following situations. The requirement is provided that neither \(\mathfrak {A}_1\) nor \(\mathfrak {B}_1\) be zero simultaneously.

Family (1) : If \(\tau _0=\tau _1 =\tau _3 = 0\), then

Set (1.1) : \(\displaystyle \mathfrak {A}_0= \mathfrak {A}_1= 0,\tau _2= -\frac{2 \alpha \beta ^2+\frac{\alpha \eta _2}{\eta _3}+\frac{12 \nu }{\beta \eta _1}}{2 \alpha ^3},\)

\(\displaystyle \mathfrak {B}_1= \pm \frac{\sqrt{\alpha ^2 \beta ^2 \eta _1^2 \left( 16 \beta ^4 \eta _3^2-4 \beta ^2 \eta _2 \eta _3-\eta _2^2\right) -24 \alpha \beta \eta _3 \eta _1 \left( 4 \beta \eta _3 \left( \alpha \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) -\beta \nu \right) +\eta _2 \nu \right) -144 \eta _3^2 \nu ^2}}{8 \alpha ^2 \beta \sqrt{3 \eta _1 \eta _3^3 \tau _4}}.\)

Set (1.2) : \(\displaystyle \mathfrak {A}_0=\mathfrak {B}_1= 0,\ \mathfrak {A}_1= \pm \sqrt{\frac{3 \tau _4 \left( \vartheta +\alpha \beta \eta _3 \left( \beta \eta _3 \left( 2 \alpha \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) +33 \beta \nu \right) +18 \eta _2 \nu \right) \right) }{\eta _3 \left( 31 \beta ^6 \eta _3^2+36 \beta ^4 \eta _2 \eta _3+9 \beta ^2 \eta _2^2\right) }},\ \)

\(\displaystyle \eta _1= -\frac{216 \eta _3^2 \nu ^2}{\alpha \beta \eta _3 \left( \beta \eta _3 \left( 2 \alpha \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) +33 \beta \nu \right) +18 \eta _2 \nu \right) -\vartheta },\ \tau _2= \frac{\alpha \beta ^2 \eta _3^2 \left( 2 \alpha \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) -3 \beta \nu \right) -\vartheta }{6 \alpha ^3 \beta \eta _3^2 \nu },\)

where \(\vartheta =\sqrt{\alpha ^2 \beta ^3 \eta _3^3 \left( \beta \eta _3 \left( 4 \alpha ^2 \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) ^2+132 \alpha \beta \nu \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) -27 \beta ^2 \nu ^2\right) +36 \eta _2 \nu \left( 2 \alpha \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) -3 \beta \nu \right) \right) }\).

By considering solution set (1.1), the exact solutions can be obtained as follows:

(1.1,1)If \(\tau _2 >0,\ \tau _4<0\), so:

which represents a hyperbolic solution such that

\(\eta _1 \eta _3^3 (\frac{1}{3} \alpha ^2 \beta ^2 \eta _1^2 \left( 16 \beta ^4 \eta _3^2-4 \beta ^2 \eta _2 \eta _3-\eta _2^2\right) -8 \alpha \beta \eta _3 \eta _1 \left( 4 \beta \eta _3 \left( \alpha \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) -\beta \nu \right) +\eta _2 \nu \right) -48 \eta _3^2 \nu ^2)<0.\)

(1.1,2) If \(\tau _2 <0,\ \tau _4>0\), so:

which represents a periodic solution such that

\(\eta _1 \eta _3^3 (\frac{1}{3} \alpha ^2 \beta ^2 \eta _1^2 \left( 16 \beta ^4 \eta _3^2-4 \beta ^2 \eta _2 \eta _3-\eta _2^2\right) -8 \alpha \beta \eta _3 \eta _1 \left( 4 \beta \eta _3 \left( \alpha \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) -\beta \nu \right) +\eta _2 \nu \right) -48 \eta _3^2 \nu ^2)>0.\)

When we consider the solutions set (1.2), we are able to establish the following exact solutions for Eq. (3):

(1.2,1) If \(\tau _2 >0\) and\(\ \tau _4<0\), then:

which represents a bright soliton solution such that \(\left( \vartheta +\alpha \beta \eta _3 \left( \beta \eta _3 \left( 2 \alpha \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) +33 \beta \nu \right) +18 \eta _2 \nu \right) \right) >0\) and \(\eta _3 \left( 31 \beta ^6 \eta _3^2+36 \beta ^4 \eta _2 \eta _3+9 \beta ^2 \eta _2^2\right) <0\). The sech-type solution is a well-known soliton solution in nonlinear optics, appearing in self-focusing optical media such as fiber optics and photonic crystals.

(1.2,2) If \(\tau _2 <0\) and\(\ \tau _4>0\), so:

which denotes a singular periodic solution such that \(\left( \vartheta +\alpha \beta \eta _3 \left( \beta \eta _3 \left( 2 \alpha \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) +33 \beta \nu \right) +18 \eta _2 \nu \right) \right) >0\) and \(\eta _3 \left( 31 \beta ^6 \eta _3^2+36 \beta ^4 \eta _2 \eta _3+9 \beta ^2 \eta _2^2\right) >0\). The sec-type solution suggests periodic wave behavior, possibly modeling nonlinear wave patterns in optical lattices.

In the presence of stochastic perturbations, these solutions can describe stable pulses that resist dispersion, which is crucial for optical communication systems.

Family (2) : If \(\tau _1 = \tau _3 = \mathfrak {A}_0=0\), then we construct different solutions’ sets as:

Set (2.1) : \(\mathfrak {A}_1= \pm \alpha \sqrt{-\frac{\eta _1 \tau _4}{2 \eta _3}},\ \mathfrak {B}_1= 0,\tau _2= \frac{-\alpha ^2 \beta ^2 \eta _1 \eta _3\mp \sqrt{3 \left( \alpha ^4 \eta _1 \eta _3 \left( -\eta _1 \left( \eta _3 \left( \beta ^4-16 \alpha ^4 \tau _0 \tau _4\right) +4 \beta ^2 \eta _2\right) -32 \eta _3 \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) \right) \right) }}{2 \alpha ^4 \eta _1 \eta _3},\)

\(\nu = \pm \frac{\beta \left( \sqrt{3 \left( \alpha ^4 \eta _1 \eta _3 \left( -\eta _1 \left( \eta _3 \left( \beta ^4-16 \alpha ^4 \tau _0 \tau _4\right) +4 \beta ^2 \eta _2\right) -32 \eta _3 \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) \right) \right) }-\alpha ^2 \eta _1 \left( 11 \beta ^2 \eta _3+6 \eta _2\right) \right) }{72 \alpha \eta _3}.\)

Set (2.2) : \(\mathfrak {A}_1= 0,\ \mathfrak {B}_1= \pm \alpha \sqrt{-\frac{\eta _1 \tau _0}{2 \eta _3}},\ \tau _2= \frac{-\alpha ^2 \beta ^2 \eta _1 \eta _3\mp \sqrt{3 \left( \alpha ^4 \eta _1 \eta _3 \left( -\eta _1 \left( \eta _3 \left( \beta ^4-16 \alpha ^4 \tau _0 \tau _4\right) +4 \beta ^2 \eta _2\right) -32 \eta _3 \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) \right) \right) }}{2 \alpha ^4 \eta _1 \eta _3},\)

\(\nu = \pm \frac{\beta \left( \sqrt{3 \left( \alpha ^4 \eta _1 \eta _3 \left( -\eta _1 \left( \eta _3 \left( \beta ^4-16 \alpha ^4 \tau _0 \tau _4\right) +4 \beta ^2 \eta _2\right) -32 \eta _3 \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) \right) \right) }-\alpha ^2 \eta _1 \left( 11 \beta ^2 \eta _3+6 \eta _2\right) \right) }{72 \alpha \eta _3}.\)

Set (2.3) : \(\mathfrak {A}_1= \pm \alpha \sqrt{-\frac{\eta _1 \tau _4}{2 \eta _3}},\ \mathfrak {B}_1= \pm \alpha \sqrt{-\frac{\eta _1 \tau _0}{2 \eta _3}},\)

\(\tau _2= \frac{-\alpha ^2 \eta _1 \eta _3 \left( 36 \alpha ^2 \sqrt{\tau _4 \tau _0}+\beta ^2\right) \mp \sqrt{3 \left( \alpha ^4 \eta _1 \eta _3 \left( \eta _1 \left( \eta _3 \left( 512 \alpha ^4 \tau _0 \tau _4+32 \alpha ^2 \beta ^2 \sqrt{\tau _4 \tau _0}-\beta ^4\right) -4 \beta ^2 \eta _2\right) -32 \eta _3 \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) \right) \right) }}{2 \alpha ^4 \eta _1 \eta _3},\)

\(\nu = \pm \frac{\beta \left( \alpha ^2 \eta _1 \left( \eta _3 \left( 48 \alpha ^2 \sqrt{\tau _4 \tau _0}-11 \beta ^2\right) -6 \eta _2\right) +\sqrt{3 \left( \alpha ^4 \eta _1 \eta _3 \left( \eta _1 \left( \eta _3 \left( 512 \alpha ^4 \tau _0 \tau _4+32 \alpha ^2 \beta ^2 \sqrt{\tau _4 \tau _0}-\beta ^4\right) -4 \beta ^2 \eta _2\right) -32 \eta _3 \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) \right) \right) }\right) }{72 \alpha \eta _3}\).

When selecting the solutions’ set (2.1), the corresponding exact solutions will be:

(2.1,1) If \(\tau _2 <0,\ \tau _4>0\) and\(\ \tau _0=\frac{\tau _2^2}{4 \tau _4}\), then:

which is a dark soliton solution provided that \(\eta _1 \eta _3<0\).

(2.1,2) If \(\tau _2>0,\ \tau _4>0\) and\(\ \tau _0=\frac{\tau _2^2}{4 \tau _4}\), then:

which is a singular periodic solution by providing that \(\eta _1 \eta _3<0\).

(2.1,3) If \(\tau _2 >0,\ \tau _4<0,\ \tau _0=\frac{\mu ^2 \left( 1-\mu ^2\right) \tau _2^2}{\left( 2 \mu ^2-1\right) ^2 \tau _4}\), and \(0< \mu \le 1\), then the solution will be a JEF such that \(\eta _1 \eta _3>0\) as:

The cn function corresponds to periodic wave trains, appearing in nonlinear optical fibers and waveguides. When setting \(\mu =1\), one could find the following bright soliton solution:

(2.1,4) If \(\tau _2 >0,\ \tau _4<0,\ \tau _0=\frac{\left( 1-\mu ^2\right) \tau _2^2}{\left( 2-\mu ^2\right) ^2 \tau _4}\), and \(0<m\le 1\), then a JEF solution is found providing that \(\eta _1 \eta _3>0\):

The dn function corresponds to periodic wave trains, appearing in nonlinear optical fibers and waveguides. As a particular case, when \(\mu = 1\), a bright soliton solution can be evaluated as:

(2.1,5) If \(\tau _2 <0,\ \tau _4>0,\ \tau _0=\frac{\mu ^2 \tau _2^2}{\left( \mu ^2+1\right) ^2 \tau _4}\), and \(0<\mu \le 1\), then a JEF solution is found providing that \(\eta _1 \eta _3<0\):

The sn-type solution describes breather modes, which arise in stochastic optical solitons where noise influences pulse evolution. A particular case, when \(\mu = 1\), a dark soliton solution is raised:

In stochastic optics, these solutions are essential for modeling modulated wave packets, where noise-driven instabilities can induce chaotic wave structures.

Through Set (2.2), the solutions are obtained as follows:

(2.2,1) If \(\tau _2 <0,\ \tau _4>0\) and\(\ \tau _0=\frac{\tau _2^2}{4\tau _4}\), one can obtain a singular soliton solution provided that \(\eta _1 \eta _3<0\):

(2.2,2) If \(\tau _2>0,\ \tau _4>0\) and\(\ \tau _0=\frac{\tau _2^2}{4\tau _4}\), one can construct a singular periodic solution provided that \(\eta _1 \eta _3<0\):

(2.2,3) If \(\tau _2 >0,\ \tau _4<0,\ \tau _0=\frac{\mu ^2 \left( 1-\mu ^2\right) \tau _2^2}{\left( 2 \mu ^2-1\right) ^2 \tau _4},\ \eta _1 \eta _3<0\) and \(0\le \mu < 1\), we construct a JEF solution which reads as:

As a particular case, when \(\mu = 0\), a singular periodic solution is raised below:

(2.2,4) If \(\tau _2 >0,\ \tau _4<0,\ \tau _0=\frac{\left( 1-\mu ^2\right) \tau _2^2}{\left( 2-\mu ^2\right) ^2 \tau _4}\), and \(0<\mu < 1\), then a JEF solution is found providing that \(\eta _1 \eta _3>0\):

(2.2,5) If \(\tau _2 <0,\ \tau _4>0,\ \tau _0=\frac{\mu ^2 \tau _2^2}{\left( \mu ^2+1\right) ^2 \tau _4},\ 0\le \mu \le 1\) and \(\eta _1 \eta _3<0\), then a JEF solution shall be acquired as:

By setting either \(\mu =0\) or \(\mu =1\), one can build up either a singular periodic solution or a singular soliton solution, respectively as follows:

Through Set (2.3), the solutions are obtained as below:

(2.3,1) If \(\tau _2 <0,\ \tau _4>0\) and\(\ \tau _0=\frac{\tau _2^2}{4\tau _4}\), one can establish a singular soliton solution by providing that \(\eta _1 \eta _3<0\):

(2.3,2) If \(\tau _2>0,\ \tau _4>0,\) and \(\ \tau _0=\frac{\tau _2^2}{4\tau _4}\), one can evaluate a singular periodic solution under the condition that \(\eta _1 \eta _3<0\):

Family (3) : If \(\tau _0=\tau _1 = \tau _4 = 0\), then, in this case, we construct a set of solutions as:

By denoting \(\delta _1=-\alpha \beta \eta _3^2 \left( \alpha \beta \eta _1 \left( 2 \beta ^2 \eta _3+\eta _2\right) +12 \eta _3 \nu \right)\),

\(\delta _2=4 \beta \eta _3 \left( \alpha \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) -\beta \nu \right) +\eta _2 \nu\), \(\delta _3=-16 \beta ^4 \eta _3^2+4 \beta ^2 \eta _2 \eta _3+\eta _2^2,\)

and \(\delta _4=\frac{1}{6} \alpha ^2 \beta ^2 \delta _3 \eta _1^2+4 \alpha \beta \delta _2 \eta _3 \eta _1+24 \eta _3^2 \nu ^2\), one could find the following solutions:

(3.1)

which denotes a hyperbolic solution such that \(\delta _1 \delta _4>0\).

(3.2)

which denotes a periodic wave solution such that \(\delta _1 \delta _4>0\).

Family (4) : If \(\tau _3 = \tau _4 = 0\), then, in this case, we construct multiple sets of solutions as:

Set (4.1) : \(\displaystyle \mathfrak {A}_0= \mathfrak {A}_1= \tau _1=0,\ \mathfrak {B}_1= \pm \frac{\alpha \sqrt{\tau _0 \left( \eta _1 \left( \alpha ^2 \tau _2 \left( \alpha ^2 \tau _2+\beta ^2\right) +\beta ^4\right) +24 \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) \right) }}{\beta \sqrt{6 \eta _2}},\)

\(\displaystyle \eta _3= -\frac{3 \beta ^2 \eta _1 \eta _2}{\eta _1 \left( \alpha ^2 \tau _2 \left( \alpha ^2 \tau _2+\beta ^2\right) +\beta ^4\right) +24 \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) },\ \nu = \frac{\alpha \left( \eta _1 \left( \alpha ^4 \tau _2^2-5 \beta ^4\right) +24 \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) \right) }{36 \beta }.\)

Set (4.2) : \(\displaystyle \mathfrak {A}_0= \pm \frac{\alpha \sqrt{-\tau _2} \sqrt{\eta _1 \left( \alpha ^2 \tau _2 \left( \alpha ^2 \tau _2+\beta ^2\right) -2 \beta ^4\right) -48 \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) }}{4 \beta \sqrt{3 \eta _2}},\ \mathfrak {A}_1= 0,\)

\(\displaystyle \mathfrak {B}_1= \pm \frac{\alpha \sqrt{-\tau _0} \sqrt{\eta _1 \left( \alpha ^2 \tau _2 \left( \alpha ^2 \tau _2+\beta ^2\right) -2 \beta ^4\right) -48 \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) }}{2 \beta \sqrt{3 \eta _2}},\ \tau _1=\pm 2 \sqrt{\tau _2 \tau _0},\)

\(\displaystyle \eta _3= \frac{6 \beta ^2 \eta _1 \eta _2}{\eta _1 \left( \alpha ^2 \tau _2 \left( \alpha ^2 \tau _2+\beta ^2\right) -2 \beta ^4\right) -48 \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) },\ \nu = \frac{\alpha \left( 48 \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) -\eta _1 \left( \alpha ^4 \tau _2^2+10 \beta ^4\right) \right) }{72 \beta }.\)

From Set (4.1), one can able to construct the upcoming solutions such that \(\eta _2 (\eta _1 \left( \alpha ^4 \tau _2^2+\alpha ^2 \beta ^2 \tau _2+\beta ^4\right) +\left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) )>0\):

(4.1,1) If \(\tau _0>0\) and \(\tau _2<0\), then one can find a singular periodic solution, which shall be read as:

(4.1,2) If \(\tau _0>0\) and \(\tau _2>0\), then one can build up a singular soliton solution as follows:

From Set (4.2),

which represents an exponential solution under the conditions that \(e^{\sqrt{\tau _2} (\alpha x-\nu t)}-\frac{\tau _1}{2 \tau _2}\ne 0\) and

\(\eta _2 \left( \eta _1 \left( \alpha ^2 \tau _2 \left( \alpha ^2 \tau _2+\beta ^2\right) -2 \beta ^4\right) -48 \left( \omega +\varrho ^2\right) \right) <0\).

Graphical and physical interpretation for the influence of noise on the extracted solutions

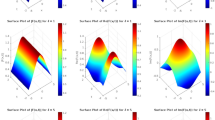

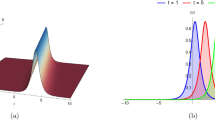

In this part of the article, one can see an explanation of the impact of applying the white noise on some of the resulting solutions. Using MATLAB software, we investigate the effect of adding this noise with different intensities using 3D and 2D graphical representations of the obtained solutions. These graphical representations will show the robustness of the obtained solutions by considering the noise. Figure 1 represents the 3D representations of Eq. (18) with \(\eta _1=2,~\eta _2=2,~\eta _3=-2,~\omega =0,~\beta =0,~\alpha =-2,~\tau _0=-2,~\tau _4=-2\). These plots demonstrate how rising noise intensity (\(\varrho\)) imparts greater unpredictability into wave dynamics. For small values of \(\varrho\), the solution stays smooth, similar to a deterministic wave. As \(\varrho\) grows, the solution becomes more volatile, indicating the impact of random disturbances on the wave’s stability and structure. This phenomenon is important in physical systems such as optical fibers, Bose-Einstein condensates, and fluid turbulence, where noise affects wave propagation. The surface flattens and the signal level drops as the noise intensity rises, according to observations. Utilizing different noise intensities, a 2D graph of Eq. (18) is depicted in Fig. 2. These plots show how the wave solution changes over time with varied noise strengths. The deterministic solution (\(\varrho =0\)) has a smooth transition, but raising \(\varrho\) adds deviations, generating variations around the mean solution. This represents how external disturbances or intrinsic system noise impact wave stability, which can result in diffusion-like spreading, instability, or disruption of the wave profile depending on the noise intensity. With \(\eta _1=-2,~\eta _3=-2,~\omega =0,~\beta =0\), 3D plots of Eq. (21) are displayed in Fig. 3. These visuals demonstrate how increasing noise intensity (\(\varrho\)) affects the wave profile. For smaller \(\varrho\), the wave is reasonably smooth and steady. As \(\varrho\) increases, the wave shows abnormalities and variations, reflecting the impact of random disturbances. Such noise effects in physical systems might reflect external disturbances in fluid dynamics, optical wave propagation, or quantum systems, where random fluctuations affect wave behavior and stability. Higher noise levels result in localized energy concentration or dissipation, which drastically alters the initial wave shape. By applying different noise intensities, a 2D graph of Eq. (21) is depicted in Fig. 4. This graph plots wave amplitude over time for various noise levels. When increasing \(\varrho\), it causes random fluctuations and broadens the wave profile. This illustrates noise-induced dispersion and diffusion effects, which may be observed in real-world applications such as signal transmission in noisy channels, fluid turbulence, and stochastic resonance in nonlinear systems.

3D visualizations of stochastic solution of Eq. (18).

2D plots of stochastic solution of Eq. (18) with different intensities.

3D graphical plots of stochastic solution of Eq. (21).

2D plots of stochastic solution of Eq. (21) with different intensities.

Conclusions

The generalized stochastic nonlinear Schrödinger equation’s exact, soliton solutions are the main topic of this article. Many parameters of the nonlinearity and a parameter linked to weak nonlocality were the characteristics of the equation in addition to the influence of Brownian motion. To solve this difficult problem, we used the tried-and-true method known as the improved modified extended tanh-function methodology. Through the use of this technique along with the proper traveling wave transformations, we were able to develop novel and very effective solitary-wave solutions for this model. We used MATLAB to create both 2D and 3D graphical representations in order to obtain an understanding of the equation’s physical consequences. Deep insights into a variety of facets of the behavior of the equation are provided by these visualizations. By adjusting the parameter values, we were able to reveal several other solutions, such as {dark, bright, singular} solitons, Jacobi elliptic functions, exponential, periodic, and singular periodic solutions. This work incorporates stochastic effects into a nonlinear wave equation, revealing new details on how noise affects wave stability, localization, and energy distribution. Unlike prior deterministic investigations, our results show that increasing noise levels cause major changes in wave dynamics, such as diffusion, instability, and pattern development. In the fields of mathematical science and engineering, our computational research highlights the method’s efficacy and adaptability in handling a broad spectrum of nonlinear issues. The restricted applicability of this approach to a wide range of equations and potential convergence issues may occasionally make it less dependable in yielding accurate solutions. This study’s findings are relevant to stochastic optical communication systems, where understanding noise-induced wave dynamics can improve fiber optic transmission, soliton-based communication, and nonlinear signal processing. The insights also apply to laser dynamics, quantum optics, and nonlinear photonics, aiding in the development of robust communication protocols and enhanced noise management techniques.

Data availibility

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Rafiq, M. H., Raza, N. & Jhangeer, A. Nonlinear dynamics of the generalized unstable nonlinear Schrödinger equation: A graphical perspective. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55(7), 628 (2023).

Oluwasegun, K., Ajibola, S., Akpan, U., Akinyemi, L. & şenol, M. M. Investigation of oceanic wave solutions to a modified (2+ 1)-dimensional coupled nonlinear Schrödinger system. Mod. Phys. Lett. B. 2550036 (2024).

Akinyemi, L., Erebholo, F., Palamara, V. & Oluwasegun, K. A study of nonlinear Riccati equation and its applications to multi-dimensional nonlinear evolution equations. Qual. Theory Dyn. Syst. 23(1), 1–43 (2024).

Akpan, U., Akinyemi, L., Ntiamoah, D., Houwe, A. & Abbagari, S. Generalized stochastic Korteweg-de Vries equations, their Painlevé integrability, \(N-\)soliton and other solutions. Int. J. Geometric Methods Mod. Phys. 21(7), 2450128–21021 (2024).

Alhami, R. & Alquran, M. Extracted different types of optical lumps and breathers to the new generalized stochastic potential-KdV equation via using the Cole-Hopf transformation and Hirota bilinear method. Opt. Quant. Electron. 54, 553 (2022).

Kumar, S., Hamid, I. & Abdou, M. A. Dynamic frameworks of optical soliton solutions and soliton-like formations to Schrödinger-Hirota equation with parabolic law non-linearity using a highly efficient approach. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55(14), 1261 (2023).

Ahmed, K. K., Badra, N. M., Ahmed, H. M. & Rabie, W. B. Soliton solutions and other solutions for Kundu-Eckhaus equation with quintic non-linearity and Raman effect using the improved modified extended tanh-function method. Mathematics 10, 1–11 (2022).

Khalifa, A. S. et al. Discovering novel optical solitons of two CNLSEs with coherent and incoherent nonlinear coupling in birefringent optical fibers. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(8), 1340 (2024).

Ahmed, K. K., Badra, N. M., Ahmed, H. M. & Rabie, W. B. Soliton solutions of generalized Kundu-Eckhaus equation with an extra-dispersion via improved modified extended tanh-function technique. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55(299), 1–17 (2023).

Ghayad, M. S., Badra, N. M., Ahmed, H. M. & Rabie, W. B. Analytic soliton solutions for RKL equation with quadrupled power-law of self-phase modulation using modified extended direct algebraic method. J. Opt. 1–13 (2024).

Ahmed, K. K., Badra, N. M., Ahmed, H. M. & Rabie, W. B. Unveiling optical solitons and other solutions for fourth-order (2+1)-dimensional nonlinear Schrödinger equation by modified extended direct algebraic method. J. Opt. (2024).

Khalifa, A. S., Ahmed, H. M., Badra, N. M. & Rabie, W. B. Exploring solitons in optical twin-core couplers with Kerr law of nonlinear refractive index using the modified extended direct algebraic method. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(6), 1060 (2024).

Kumar, S. & Rani, S. Lie symmetry reductions and dynamics of soliton solutions of (2 + 1)-dimensional Pavlov equation. Pramana 94(1), 116 (2020).

Khalifa, A. S., Badra, N. M., Ahmed, H. M. & Rabie, W. B. Retrieval of optical solitons in fiber Bragg gratings for high-order coupled system with arbitrary refractive index. Optik. 171116 (2023).

Ali, A., Ahmad, J. & Javed, S. Solitary wave solutions for the originating waves that propagate of the fractional Wazwaz-Benjamin-Bona-Mahony system. Alex. Eng. J. 69, 121–133 (2023).

Kaplan, M. & Ozer, M. N. Multiple-soliton solutions and analytical solutions to a nonlinear evolution equation. Opt. Quant. Electron. 50, 1–10 (2018).

Akbar, M. A., Abdullah, F. A. & Khatun, M. M. Optical soliton solutions to the time-fractional Kundu-Eckhaus equation through the \((\frac{G^{\prime }}{G},\frac{1}{G})-\)expansion technique. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55(4), 291 (2023).

Rabie, W. B. et al. New solitons and other exact wave solutions for coupled system of perturbed highly dispersive CGLE in birefringent fibers with polynomial nonlinearity law. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(5), 1–22 (2024).

Ahmed, K. K. et al. Investigation of solitons in magneto-optic wave guides with Kudryashov’s law nonlinear refractive index for coupled system of generalized nonlinear Schrödinger’s equations using modified extended mapping method. Nonlinear Anal. Model. Control 29(2), 1–19 (2024).

Suret, P. et al. Soliton gas: Theory, numerics, and experiments. Phys. Rev. E 109(6), 061001 (2024).

Ahmed, K. K., Ahmed, H. M., Badra, N. M., Mirzazadeh, M., Rabie, W. B. & Eslami, M. Diverse exact solutions to Davey-Stewartson model using modified extended mapping method. Nonlinear Anal. Model. Control 1-20 (2024).

Maimistov, A. I. Solitons in nonlinear optics. Quant. Electron. 40(9), 756 (2010).

Wang, K. J., Li, S., Shi, F. & Xu, P. Novel soliton molecules, periodic wave and other diverse wave solutions to the new (2+ 1)-dimensional shallow water wave equation. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 63(2), 53 (2024).

Fokas, A. S. & Zakharov, V. E. Important Developments in Soliton Theory (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Murad, M. A. S. Formation of optical soliton wave profiles of nonlinear conformable Schrödinger equation in weakly non-local media: Kudryashov auxiliary equation method. J. Opt. (2024).

Secer, A. et al. On stochastic pure-cubic optical soliton solutions of nonlinear Schrödinger equation having power law of self-phase modulation. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 63(9), 217 (2024).

Kamel, A. et al. Stochastic analysis and soliton solutions of the Chaffee-Infante equation in nonlinear optical media. Bound. Value Probl. 2024(1), 119 (2024).

Alkhidhr, H. A. The new stochastic solutions for three models of non-linear Schrödinger’s equations in optical fiber communications via Itô sense. Front. Phys. 11, 1144704 (2023).

Ozisik, M., Secer, A. & Bayram, M. Retrieval of optical soliton solutions of stochastic perturbed Schrödinger-Hirota equation with Kerr law in the presence of spatio-temporal dispersion. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(1), 101 (2024).

Alharbi, Y. F., Ammar, S. I. & Abdelrahman, M. A. Characteristics of new stochastic solutions to the (2+ 1)-dimensional nonlinear Schrödinger model via Wiener process. Opt. Quant. Electron. 57(1), 116 (2025).

Zhang, L., Wang, J., Liu, X. & Zhou, Y. A wavelet integral collocation method for nonlinear boundary value problems in physics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 215, 91–102 (2017).

Gunzburger, M., Webster, C. G. & Zhang, G. An adaptive wavelet stochastic collocation method for irregular solutions of partial differential equations with random input data. In Sparse Grids and Applications-Munich, 137-170 (2014).

Mohammad, M. & Trounev, A. Computational precision in time fractional PDEs: Euler wavelets and novel numerical techniques. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 12, 100918 (2024).

Zhang, Q., Feng, Z., Tang, Q. & Zhang, Y. An adaptive wavelet collocation method for solving optimal control problem. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 229(9), 1640–1649 (2015).

Mohammed, W. W., Al-Askar, F. M. & Cesarano, C. The analytical solutions of the stochastic mKdV equation via the mapping method. Mathematics 10, 4212 (2022).

Ahmed, K. K., Ahmed, H. M., Rabie, W. B. & Shehab, M. F. Effect of noise on wave solitons for (3+ 1)-dimensional nonlinear Schrödinger equation in optical fiber. Indian J. Phys. 1–20 (2024).

Alhojilan, Y. & Ahmed, H. M. Novel analytical solutions of stochastic Ginzburg-Landau equation driven by Wiener process via the improved modified extended tanh function method. Alex. Eng. J. 72, 269–274 (2023).

Cui, J., Hong, J., Liu, Z. & Zhou, W. Strong convergence rate of splitting schemes for stochastic nonlinear Schrödinger equations. J. Differ. Equ. 266(9), 5625–5663 (2019).

Cheung, K. & Mosincat, R. Stochastic nonlinear Schrödinger equations on tori. Stoch. Partial Differ. Equ. Anal. Comput. 7(2), 169–208 (2019).

Ahmed, K. K., Ahmed, H. M., Shehab, M. F., Khalil, T. A., Emadifar, H. & Rabie, W. B. Characterizing stochastic solitons behavior in (3+ 1)-dimensional Schrödinger equation with Cubic-Quintic nonlinearity using improved modified extended tanh function scheme. Phys. Open. 100233 (2024).

Samir, I., Ahmed, K. K., Ahmed, H. M., Emadifar, H. & Rabie, W. B. Extraction of newly soliton wave structure of generalized stochastic NLSE with standard Brownian motion, quintuple power law of nonlinearity and nonlinear chromatic dispersion. Phys. Open. 100232 (2024).

Hosseini, K., Sadri, K., Hinçal, E., Sirisubtawee, S. & Mirzazadeh, M. A generalized nonlinear Schrödinger involving the weak nonlocality: Its Jacobi elliptic function solutions and modulational instability. Optik 288, 171176 (2023).

Cardoso, W. B. Localization of optical pulses in guided wave structures with only fourth order dispersion. Phys. Lett. A 383(28), 125898 (2019).

Zulfiqar, H. et al. On the solitonic wave structures and stability analysis of the stochastic nonlinear Schrödinger equation with the impact of multiplicative noise. Optik 289, 171250 (2023).

Rehman, H. U., Awan, A. U., Eldin, S. M. & Iqbal, I. Study of optical stochastic solitons of Biswas-Arshed equation with multiplicative noise. AIMS Math. 8(9), 21606–21621 (2023).

Mathanaranjan, T., Kumar, D., Rezazadeh, H. & Akinyemi, L. Optical solitons in metamaterials with third and fourth order dispersions. Opt. Quant. Electron. 54(5), 271 (2022).

Raza, N., Rafiq, M. H., Alrebdi, T. A. & Abdel-Aty, A. H. New solitary waves, bifurcation and chaotic patterns of Coupled Nonlinear Schrödinger System arising in fibre optics. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55(10), 1–19 (2023).

Yang, Z. & Hon, B. Y. An improved modified extended tanh-function method. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung A. 61(3–4), 103–115 (2006).

Behera, S. Optical solitons for the Hirota-Ramani equation via improved \(G^{\prime }/G-\)expansion method. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 39(01), 2450403 (2025).

Khlaif, A. I., Mohammed, O. H. & Feki, M. Conformable variational iteration method for solving fuzzy variable-order fractional partial differential equations with proportional delay. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 101064 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.K. : Formal analysis, Software, Methodology; H.A. : Validation, Methodology; A.A. : Investigation, Writing–review & editing, Supervision; M.K. : Formal analysis, Writing–review & editing; A.S. : Resources, Writing-review & editing; I.S. : Resources, Writing-review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, K.K., Ahmed, H.M., Akgül, A. et al. Identification of stochastic optical solitons in a generalized NLSE characterized by fourth order dispersion and weak nonlocality. Sci Rep 15, 33805 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99415-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99415-9