Abstract

Nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), accounts for approximately 90% of skin cancers. Global incidence is rising, with projections showing a significant increase in cases and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). However, research on NMSC in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is limited. This study aims to assess the epidemiology and burden of NMSC in the MENA region from 1990 to 2021, by sex, age, and socio-demographic index (SDI). The analysis used data from the Global Burden of Disease 2021 on age-standardized rates and cases of incidence, prevalence, deaths, and DALYs. Estimation of NMSCs death was performed by the Cause of Death Ensemble model, while DisMod-MR 2.1 was used for non-fatal outcomes. Counts and rates were presented with 95% uncertainty intervals. In 2021, the MENA region reported an age-standardized incidence rate of 6.7 per 100,000 population for NMSC, a 14% decrease from 1990. However, the age-standardized death rate increased by 10.5% to 0.3, and the DALY rate increased by 8.2% to 4.9 per 100,000. Among the countries, Turkey had the highest age-standardized DALY rate of 13.5 and the Syrian Arab Republic had the lowest with 0.1 per 100,000. Most cases of the disease were observed in older age groups, especially men aged 65–69 and women aged 60–64. Men had higher incidence, mortality, and DALYs than women in all age groups. From 1990 to 2021, the burden of NMSC increased with increasing SDI. There is variations in the NMSC burden in the MENA region. Interdisciplinary education, policy changes, and healthcare improvements are essential to reduce the burden and incidence of NMSCs in the coming years, particularly in the elderly and high SDI countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Skin cancer is among the most diagnosed forms of cancer, classified into melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) with NMSC being the most common neoplasm in the white population. About 90% of total skin cancers are NMSCs. The two most frequent forms of NMSC, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and basal cell carcinoma (BCC), together account for approximately 99% of all NMSC cases1,2,3. SCC predominantly originates from actinic keratosis, a precursor lesion characterized by dysplastic epidermal keratinocytes4. In contrast, BCC mainly manifests as slow-growing, dome-shaped papules with raised, telangiectatic borders. More than 80% of NMSCs occur in sun-exposed areas, primarily the head and neck3, with ultraviolet (UV) radiation as the leading risk factor. Other contributing factors include age, sex, skin type, genetics, immunosuppression, certain therapies, and family history5.

Although the overall mortality rate of NMSC is quite low, SCC-specific deaths are rising, with a tumor-specific mortality rate of 1.1–3.2%. The prognosis worsens with metastasis, tumor thickness, desmoplastic growth, and immunosuppression. Mortality remains stable in younger groups but increases with age, especially in those aged 80 years and older, reaching 20–34 per 100,0006,7,8.

Early detection besides the prompt treatment, greatly increases the likelihood of successful outcomes for these locally invasive cancers. Surgical excision remains the most commonly employed treatment for NMSC. More recent developments in radiotherapy and immunotherapy also have favorable results in the management of NMSC9,10.

The global age-standardized incidence rate of NMSC rose from 54.1 in 1990 to 79.10 per 100,000 in 201911. Other indicators, such as mortality and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) showed increasing trends. Projections indicate that deaths and DALYs related to NMSC will increase at least 1.5 times higher in 2044 compared to 2020, underscoring its growing impact on public health12. The general prevalence of NMSC coupled with the large number of affected individuals can be characterized as a significant disease burden; thus, resulting in substantial economic costs and overwhelming healthcare systems. It is, therefore, necessary to assess the burden of NMSC to recommend public health strategies for its prevention and management.

Some studies have investigated the incidence and death of NMSC at both regional and global levels13,14,15,16. However, none have focused on the attributable burden of NMSCs in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. The MENA region, comprising 21 countries and approximately 436 million people, has significant variations in socioeconomic status, healthcare coverage, infrastructure, cancer registries, and public health programs. The region shares important geographical, cultural, and economic characteristics. Because of the shared traits from a geopolitical perspective, they have been categorized under the MENA region12,17,18,19.

In the MENA region, health outcomes have improved, as reflected in increased life expectancy and reduced neonatal mortality20,21,22. In the MENA region, high exposure to UV radiation, variations in skin phototypes, cultural practices, and genetic predispositions, elevate the region’s vulnerability to NMSC23,24,25. In addition, healthcare disparities, including limited access to screening, delayed diagnoses, and unequal treatment availability, further exacerbate the NMSC burden in this region24,26,27. These factors underscore the need for focused research to better understand and address the unique challenges of NMSC in the MENA region.

Although some studies have examined the incidence of NMSC in individual MENA countries15,25, comprehensive regional analyses remain limited.. Therefore, we aimed to report the epidemiology and burden of NMSC within the MENA region from 1990 to 2021, stratifying by sex, age, and location. Furthermore, the relasionship with the socio-demographic index (SDI) was assessed.

Methods

Overview

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, developed by the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation, evaluates the impact of diseases and injuries across 204 countries and territories in 2021. The GBD framework evaluates mortality and morbidity using metrics such as incidence, prevalence, and DALYs, classified by cause, age, sex, year, and location.

This study used GBD 2021 data to evaluate the burden of NMSC from 1990 to 2021 across all countries in MENA. The MENA region comprises 21 countries: Afghanistan, Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. A detailed explanation of the methods to model disease burden has been previously explained elsewhere28,29. GBD 2021 estimates, spanning the years 1990 to 2021, can be accessed through the following links: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool and https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/.

Data source and definitions

The case definition for NMSC in this study is based on the criteria established by the GBD 2021. Estimates for NMSC encompass both SCC (covering incidence and mortality) and BCC (covering incidence only). For NMSC, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 codes of C44-C44.9, D04-D04.9, and D49.2, as well as ICD-9 codes of 173–173.9, 222.4, 232–232.9, and 238.2 were used28. Due to the infrequent recording of SCC in cancer registries, only vital registration system data were used for SCC mortality modeling28.

Modelling strategy

In the GBD 2021, estimates of mortality from NMSC were made using the Cause of Death Ensemble model (CODEm), a modeling tool that integrates several models to improve predictive performance. For non-fatal outcomes, the Bayesian meta-regression tool DisMod-MR 2.1 was used, integrating epidemiological data and accounting for heterogeneity in study design and population characteristics. By modeling for known biases, accounting for such covariates as demographic factors, health access, and availability of care, the estimates using the models are more dependable on the NMSC burden28.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis included age-standardized cases and rates of incidence, prevalence, and DALYs of NMSCs in the MENA region. Also, the total age-standardized death cases and rates are reported, which only refers to SCC death cases due to a lack of information on number of deaths of BCC. Additionally, the pattern of change of these four indicators was analyzed. Age standardization was performed by using the GBD World Population to enable comparisons across various time periods and regions28. Uncertainty intervals (UIs) for all metrics were computed by averaging estimates from 500 draws and 95% UIs were considered as the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the distribution28.

DALYs measure disease burden by combining years of life lost (YLLs) and years lived with disability (YLDs)30. YLLs are estimated based on premature mortality using age-specific mortality rates. YLL is calculated as the product of deaths and life expectancy predicted, giving more weight to deaths at younger ages28. YLD measures the impact of an illness on quality of life before it resolves or leads to death. YLD considers the severity of disability, with higher weights assigned to young adults compared to infants or the elderly. The age-standardized rate is the standard tool used for the estimation of disease burden and is measured per 100,000 individuals28.

Smoothing spline models were used to analyze the relationship between the SDI and the burden of NMSC31. The SDI is a composite measure incorporating per capita income, average years of schooling for individuals aged 15 and older, and the fertility rate for women aged 25 and under. It ranges from zero to one, indicating levels of development from the lowest to the highest. The analytical sample was processed using R software (version 4.2.1).

Results

The Middle East and North Africa region

In 2021, the disease burden of NMSC varied significantly across countries in the MENA region. The age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) of the disease was reported to be 6.7 (95% UI: 5.4–8.0) per 100,000 population, representing a 14% decrease from 1990. The age-standardized point prevalence of NMSC was also 1.9 (95% UI: 1.6–2.2) per 100,000 people in 2021, which has decreased by 9.4% (95% UI: − 13.2 to − 5.4) compared to 1990. In contrast, the age-standardized DALY rate increased by 8.2% (95% UI: − 12.9–38.3) to 4.9 (95% UI: 4.1–6.4) per 100,000 persons, but this increase was not statistically significant. Also, the age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR) increased by 10.5% (95% UI: − 13.6–49.8) to 0.3 (95% UI: 0.2–0.4) per 100,000 people, but this change was also not statistically significant (Table 1).

National levels

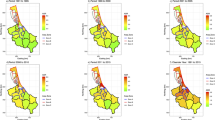

Age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) and percentage changes

The ASIR showed considerable variation among countries and sexes in the MENA region. At the national level, Turkey had the highest ASIR at 10.8 (95% UI: 8.7–12.8) per 100,000 population and also recorded the highest absolute number of new cases at 10,097. In contrast, Morocco had the lowest ASIR of 3.0 (95% UI: 2.2–3.7) per 100,000 population (Table 1 and Figure S1).

Sex analyses indicated that ASIR of males was consistently higher than females in all countries, and this difference was particularly pronounced in Turkey. In the period from 1990 to 2021, countries such as Iran − 26.4% (95% UI: − 28.4 to − 24.3), Turkey − 22.7% (95% UI: − 33.9 to − 12.9), and Jordan − 13.8% (95% UI: − 21.3 to − 7.2) reported a decrease in ASIR, while the United Arab Emirates, Iraq, and Yemen reported an increase in the ASIR (Figure S2). These patterns indicated regional rather than sex-specific effects and remained the same for both sexes.

Age-standardized prevalence rate (ASPR) and percentage changes

The results showed that all countries in the MENA region reported an age-standardized prevalence rate (ASPR) of less than four cases per 100,000 population. Turkey 3.3 (95% UI: 2.8–3.8) had the highest ASPR among the countries in MENA, followed by Lebanon 2.9 (95% UI: 2.3–3.4), Jordan 2.5 (95% UI: 2.0, 2.9), and Iran 2.3 (95% UI: 2.0–2.8). In contrast, countries such as Libya 0.6 (95% UI: 0.4–0.7), Bahrain 0.6 (95% UI: 0.4–0.8), and Morocco 0.6 (95% UI: 0.5–0.7) had the lowest ASPR. Males had higher ASPR than females in most countries. This difference was especially evident in Turkey. On the other hand, in countries such as Libya and Bahrain, despite lower overall ASPR, sex differences were also smaller (Figure S3).

The largest increase in ASPR was reported in the United Arab Emirates 18.9% (95% UI: 10.2–28.7) over 1990–2021. On the other hand, Iran had the largest decrease with a decrease of 22.4% (95% UI: − 27.1 to − 18.1). A significant decrease was also observed in other countries such as Jordan 15.9% (95% UI: − 21.9 to − 8.6) and Turkey 15.1% (95% UI: − 23.1 to − 6.6) (Figure S4).

Age-standardized disability-adjusted life year rates and percentage changes

There were significant differences between countries and sex in terms of age-standardized DALY rates. This disease had important impacts on public health, especially in Turkey 13.5 (95% UI: 10.6–18.2), which had the highest DALY rate among countries in MENA. Following Turkey, Palestine 10.5 (95% UI: 6.2, 12.9), the United Arab Emirates 9.9 (95% UI: 7.4–13.1), and Iraq 9.0 (95% UI: 6.3, 12.6) had the highest age-standardized DALY rates. In contrast, countries such as the Syrian Arab Republic 0.1 (95% UI: 0.1–0.1), Sudan 0.2 (95% UI: 0.1–1.6), and Morocco 0.2 (95% UI: 0.1, 1.6) reported the lowest age-standardized DALY rates. In almost every country, sex-specific investigation showed a similar pattern of males having higher age-standardized DALY rates than females (Figure S5).

Between 1990 and 2021, percentage changes in age-standardized DALY rates varied considerably among MENA countries. Countries such as Egypt 549.0% (95% UI: 27.6–968.3), Libya 257.9% (95% UI: 133.2–1132.8), and Morocco 148.0% (95% UI: 82.6–504.8) had the largest increases. In contrast, Turkey with -17.2% (95% UI: − 37.5–9.9) decrease reported the greatest decline in the age-standardized DALY rates (Figure S6).

Age-standardized death rate (ASDR) and percentage changes

Figure S7 shows the significant variation in age-standardized death rate (ASDR) of NMSC among countries in the MENA region. Turkey 0.8 (95% UI: 0.6–1.0) and the United Arab Emirates 0.6 (95% UI: 0.4–0.8) reported the highest ASDR, followed by Palestine 0.6 (95% UI: 0.3–0.7) and Iraq 0.4 (95% UI: 0.3–0.6). In contrast, countries such as the Syrian Arab Republic 0.0 (95% UI: 0.0–0.0), Sudan 0.0 (95% UI: 0.0–0.1), and Yemen 0.0 (95% UI: 0.0–0.1) recorded the lowest ASDR. The sex pattern across the region showed that males consistently had higher ASDR than females.

Between 1990 and 2021, Egypt 557.9% (95% UI: 30.8–1036.3), Libya 261.0% (95% UI: 142.9–1523.5), and Morocco 176.1% (95% UI: 90.3–1087.8) had the greatest increases in ASDR. In contrast, Turkey − 12.2% (95% UI: − 34.9–22.2) had the largest decrease in ASDR (Figure S8).

Age and sex patterns

In 2021, the incident cases of NMSC increased with age, peaking in the 65–69 age group, and then declined in older age groups. The incidence rates increased with age and it was highest in the 95 + age group for both males and females. Moreover, in almost all age groups, particularly among those aged 70–74 and 75–79, men exhibit higher incidence rates than women (Fig. 1A). The trend of prevalence was similar so the number of prevalent cases increased in men up to the age group of 65–69 years for both males and females then decreased in older age groups. The regional point prevalence of NMSC in both sexes had an upward trend with increasing age (Fig. 1B).

Total incident cases and incidence rate (A), total prevalent cases and point prevalence (B), total DALYs and DALY rate (C), and total death cases and death rates (D) of nonmelanoma skin cancer (per 100,000 population) in the Middle East and North Africa region, by age and sex in 2021. DALY = disability-adjusted-life-year.

The DALY rate also increased with age, peaking in the 65–69 age group for men and 75–79 for women, reflecting the increasing disease burden associated with aging populations. In age groups after 40 years, males consistently had higher DALYs than females. In age groups less than 40 years old, except for the age group of 25–29 years old, females had higher DALYs than males. The regional DALYs for both sexes showed an upward trend up, especially after 80 years old (Fig. 1C). In terms of death, the number of deaths increased until the age range of 85–89 years for both males and females, followed by a decrease. However, the regional death rate for both sexes showed an upward trend up to the 90–94 age range (Fig. 1D).

Association with socio-demographic index (SDI)

Our analysis revealed a positive association between SDI and NMSC burden, with higher SDI countries experiencing greater age-standardized DALY rates than lower SDI countries. Countries like Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia experienced a lower-than-expected based on SDI, while the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, and Jordan reported higher-than-expected burdens (Fig. 2).

Age-standardized DALY rates of nonmelanoma skin cancer for the 21 countries, by SDI; The black line represents expected DALY rates based on the relationship between SDI and disease burden. Each point on the plot indicates the observed age-standardized DALY rate for a specific country in a given year from 1990 to 2021, resulting in 32 points per country. DALY = disability-adjusted-life-year. SDI = Socio-demographic Index.

Discussion

Our findings showed that the overall incidence and prevalence rates decreased compared to 1990, the burden measured by DALYs and mortality rates showed slight increases, though these were not statistically significant. Turkey consistently reported the highest incidence and prevalence rates, while Morocco had the lowest. Males had higher rates of incidence, prevalence, DALYs, and mortality than females. The disease burden increased with age, peaking in older age groups for incidence, DALYs, and mortality. Higher SDI countries tended to have a greater disease burden.

Our results indicated that the age-standardized incidence rates of NMSCs in the MENA region have decreased, while the study of Hu et al. showed that NMSC is rapidly becoming more common worldwide; their predictions indicated that the number of incident cases, deaths, and DALYs related to NMSCs will increase by at least 1.5 times from 2020 to 2044 globally11. This global increase is primarily attributed to aging populations and population growth. However, the MENA region has a younger population, which may explain the lower incidence of NMSC16,32,33. Increased scrutiny may lead to higher cancer detection rates, potentially leading to overdiagnosis. A study found that routine health screenings raised the likelihood of detecting skin cancers like NMSC regardless of risk factors34. This information could justify the upward trend of NMSC globally, but the decreasing incidence of NMSC can be attributed to the fact that in the MENA region, where routine screening and healthcare access may be limited and lead to lower reported incidence of NMSC, despite the possibility of similar or even higher actual rates which can affect comparability across regions.

This study demonstrated a decline in age-standardized incidence and prevalence rates, but an increase in age-standardized death and DALY rates of NMSC from 1990 to 2021. These findings showed significant regional variations. Some countries, such as Turkey, experienced notable improvements across all metrics, likely due to enhanced detection and reporting of NMSCs that may be related to the efforts under the Turkey National Cancer Programme, which focuses on cancer prevention and control, including increasing public awareness national cancer screening programs, protection and public health policies, and the role of healthcare providers35,36. In contrast, countries like Egypt and Libya, while showing declines in age-standardized incidence and prevalence rates, saw increasing trends in death and DALY rates. This discrepancy may be explained by disparities in healthcare access. Despite earlier detection, regions with limited resources or access to specialized care may struggle to provide effective treatment, leading to worse outcomes and higher mortality and DALY rates. Increased UV exposure and urbanization can also result in more aggressive NMSC forms, contributing to higher death and DALY rates, even as incidence decreases. In addition, while early detection may reduce the number of severe cases reported, inadequate treatment and healthcare limitations can worsen outcomes, driving up mortality and disability despite a decline in incidence.

Recent GBD 2019 research on the global burden of NMSC demonstrated that ASIR, together with the metrics of new cases, deaths, DALYs, and mortality rates, have all shown an upward trend11. This does not align with our findings in the MENA region. Although the incidence of NMSCs cancer is generally decreasing in the MENA region, the rates vary greatly among different countries. It could depend on variations in exposure to the relevant risk factors such as individual characteristics and environmental conditions, including skin type, latitude, and sun exposure. However, none of these changes were statistically significant, so they should be interpreted with caution when considering future planning and policy development.

Iran had the greatest decrease in age-standardized incidence and prevalence rates among MENA countries, which may be attributed to behavioral education programs, such as sun protection awareness and early-stage skin cancer screening which can facilitate early treatment and help prevent deaths37,38. The upward trend seems more prominent for Turkey, and might be explained by the heavy engagement of its young population in industrial and agricultural works, necessitating long exposure to sunlight. There is also a high recurrence of NMSC in this country, thus contributing to an increasing trend39,40. The incidence and prevalence of NMSC generally showed a decline for both sexes in most countries from 1990 to 2021. However, exceptions such as the United Arab Emirates and Iraq, which presented opposite trends, probably due to high exposure to UV radiation, especially during summer. In the United Arab Emirates, rapid urbanization has fostered a lifestyle involving increased outdoor activities, sunbathing, and tanning practices, along with high exposure to the sun, contributing to the rise in skin cancer.

The peak incident cases of NMSC in the 65–69 year age group declines with age, while the greatest value for incidence rates in the 95 + age group may reflect diagnostic bias due to limited access to advanced diagnostic techniques (e.g., optical coherence tomography, videodermoscopy, confocal microscopy) in many MENA countries, leading to underdiagnosis at earlier stages and delayed detection. Males showed a higher burden of the disease, as depicted by higher prevalence, DALY, and mortality. Although the peak of DALY rate was higher in females, a study indicated that young women are more prone to developing NMSC due to hormonal patterns, which may lead to earlier onset. This earlier occurrence among the fact that women live longer than men can result in higher YLD and subsequently greater DALYs, despite lower overall incidence compared to males41. Sex differences in disease onset have been observed in several conditions such as depression, melanoma42, and gastric cancer43. Similarly, epidemiological studies have reported a greater disease burden of NMSC in males compared to females44. A study on NMSC trends in Tripoli, Libya found that males were more frequently affected than females45, which is consistent with the results of this study. Perhaps because men are spending more time outdoors, have more occupational UV exposure, and have lower usage of protective measures like sunscreen. Also, men’s skin is more prone to UV damage, lacks estrogen’s protective effects, and delayed care increases their NMSC risk46,47,48.

There was a positive association between socioeconomic status, measured using SDI, and the age-standardized DALY rates. The United Arab Emirates and Turkey, with higher SDI, experienced more DALYs from NMSCs. In contrast, Yemen and Afghanistan, with lower SDI, showed the least DALYs. Several Studies has proved that increased socioeconomic status significantly raises the risk for NMSC11,49,50,51, which is consistent with our findings. It was supposed that tanning acts more and more like a social phenomenon of success and happiness, and leisure time outdoors has grown. Besides that, in areas of high SDI, the public knows more about NMSC, resulting in more case detections and notifications, while low SDI countries may report fewer cases of NMSCs, which may result in lower DALYs, potentially due to limited data availability and healthcare infrastructure.

The study has several limitations. Firstly, the GBD database has data quality issues that may affect the accuracy of the estimates. A key issue is the variability in cancer registries across regions, particularly in lower-SDI countries, where cancer reporting systems may be incomplete or underdeveloped. This can lead to underreporting of NMSC cases, resulting in an underestimation of the true burden of the disease11. Additionally, variations in healthcare access, particularly in regions with limited resources especially in countries with lower SDI, can impact the diagnosis and reporting of NMSC, further complicating the accuracy of the data. To address these limitations, it would be helpful to use more robust data collection methods, improve regional reporting systems, and focus on large-scale cohort studies in each country in the MENA region. Additionally, special attention should be given to conflict-affected regions to alleviate healthcare challenges and better address NMSC. Despite these challenges, this study provides the most up-to-date estimates of the burden of NMSCs in the MENA region.

Conclusions

The burden of NMSCs in the MENA region has shown variations across countries. Males had higher incidence and mortality, especially in older adults. Interdisciplinary actions are needed to address NMSCs in the MENA region, including sun protection education, policy modifications to reduce sun exposure during work hours, and improved screening. In addition, efforts should be made to improve data accuracy and health infrastructure in low SDI countries. Key actions should include comprehensive sun protection education, emphasizing sunscreen use, protective clothing, and limiting sun exposure, particularly for outdoor workers. Policy changes, such as adjusting work hours to minimize sun exposure, should be implemented in sectors with high outdoor labor. Early detection must be prioritized, with mobile screening units and telemedicine to improve access in underserved areas. Strengthening healthcare infrastructure and improving data accuracy in low-SDI countries will ensure better diagnosis and monitoring of NMSC trends. Regional collaboration would be necessary to share learning and resources, increase the effectiveness of these interventions, and eventually control the NMSC burden in the region.

Data availability

The data used for these analyses are all publicly available at https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

References

Samarasinghe, V. & Madan, V. Nonmelanoma skin cancer. J. Cutan. Aesthet. Surg. 5(1), 3–10 (2012).

Katalinic, A., Kunze, U. & Schäfer, T. Epidemiology of cutaneous melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany: Incidence, clinical subtypes, tumour stages and localization (epidemiology of skin cancer). Br. J. Dermatol. 149(6), 1200–1206 (2003).

Lomas, A., Leonardi-Bee, J. & Bath-Hextall, F. A systematic review of worldwide incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Br. J. Dermatol. 166(5), 1069–1080 (2012).

Samarasinghe, V., Madan, V. & Lear, J. T. Management of high-risk squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 11(5), 763–769 (2011).

Larese Filon, F., Buric, M. & Fluehler, C. UV exposure, preventive habits, risk perception, and occupation in NMSC patients: A case-control study in Trieste (NE Italy). Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 35(1), 24–30 (2019).

Eigentler, T. K. et al. Survival of patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Results of a prospective cohort study. J. Investig. Dermatol. 137(11), 2309–2315 (2017).

Stang, A. et al. Incidence and mortality for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Comparison across three continents. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 33, 6–10 (2019).

Keim, U. et al. Incidence, mortality and trends of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in Germany, the Netherlands, and Scotland. Eur. J. Cancer 183, 60–68 (2023).

Cheraghi, N., Cognetta, A. & Goldberg, D. Radiation therapy in dermatology: Non-melanoma skin cancer. J. Drugs Dermatol. JDD. 16(5), 464–469 (2017).

Lv, R. & Sun, Q. A network meta-analysis of non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) treatments: Efficacy and safety assessment. J. Cell. Biochem. 118(11), 3686–3695 (2017).

Hu, W., Fang, L., Ni, R., Zhang, H. & Pan, G. Changing trends in the disease burden of non-melanoma skin cancer globally from 1990 to 2019 and its predicted level in 25 years. BMC Cancer 22(1), 836 (2022).

Lozano, R. et al. Measuring universal health coverage based on an index of effective coverage of health services in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 396(10258), 1250–1284 (2020).

Pondicherry, A. et al. The burden of non-melanoma skin cancers in Auckland New Zealand. Austral J. Dermatol. 59(3), 210–213 (2018).

Aggarwal, P., Knabel, P. & Fleischer, A. B. Jr. United States burden of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer from 1990 to 2019. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 85(2), 388–395 (2021).

Almaani, N. et al. Incidence trends of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers in Jordan from 2000 to 2016. JCO Global Oncol. 9, e2200338 (2023).

Zhang, W. et al. Global, regional and national incidence, mortality and disability-adjusted life-years of skin cancers and trend analysis from 1990 to 2019: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Cancer Med. 10(14), 4905–4922 (2021).

Mandil, A., Chaaya, M. & Saab, D. Health status, epidemiological profile and prospects: Eastern mediterranean region. Int. J. Epidemiol. 42(2), 616–626 (2013).

Faghih, N. & Zali, M. R. Entrepreneurship Education and Research in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) (Springer, 2018).

Katoue, M. G., Cerda, A. A., García, L. Y. & Jakovljevic, M. Healthcare system development in the Middle East and North Africa region: Challenges, endeavors and prospective opportunities. Front. Public Health 10, 1045739 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2019: A comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 396(10258), 1160–1203 (2020).

Sepanlou, S. G., Aliabadi, H. R., Malekzadeh, R., Naghavi, M., Collaborators GCMiME. Neonate, Infant, and Child Mortality in North Africa and Middle East by Cause: An analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Archiv. Iran. Med. 25(12), 767 (2022).

Hajjar, R. et al. Prevalence of aging population in the Middle East and its implications on cancer incidence and care. Ann. Oncol. 24, vii11–vii24 (2013).

Al-Qarqaz, F. et al. Clinical and demographic features of basal cell carcinoma in North Jordan. J. Skin Cancer 2018(1), 2624054 (2018).

Lucas, R. M., Norval, M. & Wright, C. Y. Solar ultraviolet radiation in Africa: A systematic review and critical evaluation of the health risks and use of photoprotection. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 15(1), 10–23 (2016).

Kiani, B. et al. Spatial epidemiology of skin cancer in Iran: Separating sun-exposed and non-sun-exposed parts of the body. Archiv. Public Health. 80(1), 35 (2022).

Jarab, A. S. et al. Public knowledge, attitudes, practices, and barriers to skin cancer screening in the United Arab Emirates. PLoS ONE 20(1), e0316613 (2025).

Shukla, A., Zeidan, R. K. & Saddik, B. Pediatric and adolescent cancer disparities in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region: Incidence, mortality, and survival across socioeconomic strata. BMC Public Health 24(1), 3602 (2024).

GBD 2021 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 403(10440):2100–32 (2024).

GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 403(10440):2133–61 (2024).

Murray, C. J. Quantifying the burden of disease: The technical basis for disability-adjusted life years. Bull. World Health Organ. 72(3), 429 (1994).

Schimek, M. G. Smoothing and regression: approaches, computation, and application (John Wiley & Sons, 2013).

Diepgen, T. L. & Mahler, V. The epidemiology of skin cancer. Br. J. Dermatol. 146(s61), 1–6 (2002).

Kocarnik, J. M. et al. Cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life years for 29 cancer groups from 2010 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. JAMA Oncol. 8(3), 420–444 (2022).

Drucker, A. M. et al. Association between health maintenance practices and skin cancer risk as a possible source of detection bias. JAMA Dermatol. 155(3), 353–357 (2019).

Kus, C. et al. Knowledge and protective behaviors of teachers on skin cancer: A cross-sectional survey study from Turkey. Children 10(2), 291 (2023).

Dogan, E. S. & Caydam, O. D. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding skin cancer among health sciences students in Turkey: A cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 142(6), e2024089 (2024).

Kamyab, A., Gholami, T., Behdad, K. & Jeihooni, A. K. An application of a series of theory-based educational intervention based on the health belief model on skin cancer prevention behaviors in female high school students. Heliyon 9(6), e17209 (2023).

Robati, R. M., Toossi, P., Karimi, M., Ayatollahi, A. & Esmaeli, M. Screening for skin cancer: A pilot study in Tehran Iran. Indian J. Dermatol. 59(1), 105 (2014).

Baş, S., Çakır, Ş, Ertaş, Y., Irmak, F. & Yeşilada, A. K. Epidemiological evaluation of non-melanoma skin cancer according to body distribution. TURKDERM Turkish Archiv. Dermatol. Venereol. 54(2), 51–57. https://doi.org/10.4274/turkderm.galenos.2020.09125 (2020).

Kocaaslan, F. N. D., Alakus, A. C., Sacak, B. & Celebiler, O. Evaluation of residual tumors and recurrence rates of malignant melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer of head and neck region. Marmara Med. J. 32(3), 107–111 (2019).

Collier, V., Musicante, M., Patel, T. & Liu-Smith, F. Sex disparity in skin carcinogenesis and potential influence of sex hormones. Skin Health Dis. https://doi.org/10.1002/ski2.27 (2021).

Bellenghi, M. et al. Sex and gender disparities in melanoma. Cancers 12(7), 1819 (2020).

Lou, L. et al. Sex difference in incidence of gastric cancer: an international comparative study based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. BMJ Open 10(1), e033323 (2020).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68(1), 7–30 (2018).

Tresh, A., El Gamati, O., Elkattabi, N. & Burshan, A. A. Non melanoma skin cancer trends in Tripoli/Libya. Our Dermatol. Online. 5(4), 359 (2014).

Giacomoni, P. U., Mammone, T. & Teri, M. Gender-linked differences in human skin. J. Dermatol. Sci. 55(3), 144–149 (2009).

Lee, Y. S. et al. Occupational risk factors for skin cancer: A comprehensive review. J. Korean Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e316 (2024).

Widyarini, S., Domanski, D., Painter, N. & Reeve, V. E. Estrogen receptor signaling protects against immune suppression by UV radiation exposure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103(34), 12837–12842 (2006).

Steding-Jessen, M. et al. Socioeconomic status and non-melanoma skin cancer: A nationwide cohort study of incidence and survival in Denmark. Cancer Epidemiol. 34(6), 689–695 (2010).

Bacorn, C., Serrano, M. & Lin, L. K. Review of sociodemographic risk factors for presentation with advanced non-melanoma skin cancer. Orbit 42(5), 481–486 (2023).

Kim, Y., Feng, J., Su, K. A. & Asgari, M. M. Sex-based differences in the anatomic distribution of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Women’s Dermatol. 6(4), 286–289 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation and their collaborators for preparing these publicly available data. We also sincerely appreciate the support of the Science Skin Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. This research is a part of a thesis project under research code 43013213.

Funding

The Global Burden of Disease study was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, but they had no involvement in the preparation of this manuscript. The Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Grant No. 43013264) also supported the present report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MF, PD, SAN and SZS designed the study. SAN, PD, and MF analyzed the data and performed the statistical analyses. SAN, PD, MF, FTA, SZS, and HL drafted the initial manuscript. SAN, PD, MF, FTA, SZS, and HL critically edited and revised the initial draft of the manuscript. SZS and SAN supervised the project. All authors reviewed the drafted manuscript for critical content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran approved the present study (ethics codes: IR.SBMU.SRC.REC.1403.044 and IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1404.009).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fekri, M., Dehesh, P., Tahmasbi Arashlow, F. et al. Epidemiology and socioeconomic factors of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the Middle East and North Africa 1990 to 2021. Sci Rep 15, 17904 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99434-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99434-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Global burden of early-onset gallbladder and biliary tract cancer from 1990 to 2021

BMC Gastroenterology (2025)