Abstract

To evaluate the effect of liver steatosis on systematic cellular immunity through the changes of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets, we retrospectively reviewed subjects receiving lymphocyte subtyping during annual medical check-ups. Liver steatosis was detected by abdominal computerized tomography or ultrasound. Immunophenotyping of peripheral blood lymphocytes was analyzed by flow cytometry. Cell counts of lymphocyte subsets were calculated using a dual-platform method. The relationship between lymphocyte subsets and liver steatosis was analyzed using multivariate linear models. Using the database from January 2017 to December 2022, we included 5042 subjects, including 1441 participants with liver steatosis. After adjusting for age, gender, and metabolic dysfunctions, the presence of liver steatosis increased the absolute values of CD19+, CD16+56+, CD3+, CD4+, CD4+CD28+, CD4+CD45RA−, CD4+CD45RA+, CD4+CD45RA+62L+, CD8+, CD8+CD28+, CD8+DR+, and CD8+CD38+ cell. In males, T lymphocyte counts of all T subsets increased in liver steatosis. In females, the significant differences in subsets included increased CD4+CD28+, CD4+CD45RA−, CD8+, and CD8+DR+ cells. Significant decreases were revealed in functional and naïve T cells with aging. Metabolic factors such as hypertension and abnormal glucose metabolism increase CD4+, CD4+CD28+, and CD4+CD45RA subsets. Hyperlipidaemia appears not to affect T cell counts, whereas obesity has some effect on both CD4+ (β = 0.041, 95% CI 0.032–0.051) and CD8+ cells (β = 0.036, 95% CI 0.025–0.048). Liver steatosis potentially affects peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets, while age, gender, and metabolic dysfunctions are also associated with these immune alterations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic diseases are closely related to immune dysfunction, mainly as low-grade and persistent systematic chronic inflammation1,2. Several studies support the view that chronic inflammation is directly involved in the process of disease onset, development, and progression, such as ischemic heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and autoimmune and neurodegenerative conditions1,2,3,4. Measurement of changes in lymphocyte subsets can indicate the current immune status and homeostasis of chronically ill patients to identify high-risk patients in the era of precision medicine3. With the help of flow cytometry, lymphocytes can be divided into T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, and NK cells, and mature T cells can be divided into CD3+CD4+ cells and CD3+CD8+ cells. According to the different surface molecular markers and functions, CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes can be further classified as functional subsets (CD4+/CD8+CD28+), activation subsets (CD4+/CD8+CD38+), naive subsets (CD4+CD45RA+CD62L+) and memory subsets (CD4+CD45RA−)5.

China experienced an unexpected rapid increase in the burden of NAFLD over a short period, with a national prevalence of 29.2%6. Recently, an international consensus of experts proposed to rename this disease as “metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD)” and to include metabolic dysfunction in the diagnostic criteria, focusing on the bidirectional interaction between liver steatosis and metabolic dysfunction7. Liver steatosis has been accepted as a chronic low-grade inflammation state—both the innate and adaptive immune act as drivers of disease progression. B and T cells are related to parenchymal injury and lobular inflammation, sustaining the progression of fibrosis and carcinogenesis8,9. Most studies focused on immunopathogenesis in the liver using animal models or based on biopsy-confirmed populations. However, abdominal ultrasonography or computerized tomography (CT) is the most critical detection of liver steatosis during medical check-ups. In this study, we retrospectively analyzed peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets in a medical check-up database to provide a new dimension for evaluating liver steatosis.

Results

Population characteristics

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study population. A total of 5042 subjects were selected, including 3470 males (68.8%) and 1572 females (31.2%). The median age was 49 with an interquartile range (IQR) of 41–55 years old. Liver steatosis was detected in 1441 participants (28.6%). 604 participants had liver steatosis diagnosed by ultrasound and 1111 by computed tomography (CT), of which 275 had liver steatosis reported by both methods. The Chi-square test demonstrated that the gender was unbalanced between the two groups (p < 0.001). The liver steatosis group had significantly higher prevalences of hypertension (34.7% vs. 23.1%, p < 0.001), abnormal glucose metabolism (16.4% vs. 9.4%, p < 0.001), and hyperlipidemia (18.9% vs. 12.6%, p < 0.001). Up to 82.3% of patients with liver steatosis had obesity, compared with 46.7% in the control group (p < 0.001). The differences in blood levels of hemoglobin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), creatine, and lipid between the two groups were also listed in Table 1. Regarding peripheral blood cell counts, the absolute number of leukocytes, neutrophils, and lymphocytes was significantly higher when liver steatosis existed, while the percentage of neutrophils and lymphocytes was equivalent. As an indicator of the inflammatory status, high sensitivity C reactive protein (hsCRP) concentration was higher in the liver steatosis group (0.63 vs. 1.16, p < 0.001), and 34 of 1441 (2.4%) had a higher level of more than 10 mg/L.

Peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets in liver steatosis group

The count and percentage of B (CD19+) cells, natural killer (CD16+56+) cells and total (CD3+), helper (CD3+CD4+), cytotoxic (CD3+CD8+) T cells in peripheral blood were outlined in Table 2. The liver steatosis group had a higher number of B lymphocytes (209/μL vs. 183/μL, p < 0.001), NK cells (257/μL vs. 236/μL, p < 0.001), and T lymphocytes (1346/μL vs. 1239/μL, p < 0.001) than controls. The absolute number of other T cell subsets distinguished by CD28, CD38, CD45RA, and DR were all significantly higher when liver steatosis existed. However, the CD4+/CD8+ ratio and percentages of subsets maintained a balance between the two groups, except for the increasing rate of the DR+ group and decreasing CD38+ group of CD8+ T cells.

Multivariate analysis

Table 3 displays the results of linear regression analyses exploring the association between liver steatosis and lymphocyte counts. Before adjusting for covariates, Model 1 indicates a positive correlation between liver steatosis and cell counts of all lymphocyte subsets. Model 2 (adjusted for age and gender) and Model 3 (adjusted for age, gender, and metabolic disorders) all had similar results of linear regression analyses as the first model, supporting the effect of liver steatosis on all lymphocyte subsets tested in our study.

Gender influence on lymphocyte subsets

As the gender was unbalanced among the two groups, we further compared lymphocyte counts between gender subgroups. Among all subjects, males had higher levels of B, NK, T cells, and CD4+, CD4+CD28+, CD4+CD45RA−, CD8+, CD8+28+, CD8+DR+ subsets, while lower level naïve CD4+ and CD8+CD38+ T cells (Table S1). In the male subgroup, both B and T lymphocyte counts increased in liver steatosis participants, with significantly higher counts of all subsets. In the female subgroup, B, NK, and T cells showed significantly higher values in the liver steatosis group. The significant differences in T cells included increased CD4+, CD4+CD28+, CD4+CD45RA−, CD8+, and CD8+DR+ subsets (Table S2, Fig. 1).

Age influence on lymphocyte subsets

To further analyze the influence of age, the control group and the liver steatosis group were divided into three subgroups aged < 45 years, 45–65 years, and > 65 years. The differences in lymphocyte counts between two groups in different age subgroups are shown in Fig. 2 and Table S3. B, NK, and T cells with almost all T cell subsets had higher counts in the liver steatosis group of < 45 years and 45–65 years. However, within the most senior group (> 65 years), significant differences were not observed in NK and CD8+ T cells. CD4+ T cells, including functional (CD4+CD28+) and memory group (CD4+CD45RA−), had relatively high counts in the steatosis group, while naïve T (CD4+CD45RA+/CD4+CD45RA+62L+) showed no differences. We further analyzed the liver steatosis group separately. With the aging process, significant decreases were revealed in naïve CD4+CD45RA+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells with positive CD28 or CD38 (Fig. 3).

The influence of metabolic disorders on lymphocyte subsets

In model 3 of multivariate linear regression, metabolic factors also show potential effects on lymphocyte subsets (Table S4). Hypertension leads to increasing trend of NK cell (β = 0.024, 95% CI 0.006–0.042) and T cells (β = 0.009, 95% CI 0.000–0.018), among which CD4+ (β = 0.015, 95% CI 0.004–0.025), CD4+CD28+ functional (β = 0.018, 95% CI 0.007–0.028) and CD4+CD45RA− memory (β = 0.017, 95% CI 0.007–0.028) groups all increase. Patients with abnormal glucose metabolism have higher B levels (β = 0.021, 95% CI 0.002–0.041) and lower NK cells (β = − 0.028, 95% CI − 0.052 to − 0.005), with a similar trend in CD4+ subsets. Except for a tendency of increasing B cells (β = 0.019, 95% CI 0.002–0.036), hyperlipidemia appears not to affect T cell counts, whereas obesity has some effect on both CD4+ (β = 0.041, 95% CI 0.032–0.051) and CD8+ cells (β = 0.036, 95% CI 0.025–0.048). CD4+CD28+ (β = 0.039, 95% CI 0.029–0.048) and CD4+CD45RA− (β = 0.057, 95% CI 0.047–0.067), as well as CD8+CD28+ (β = 0.022, 95% CI 0.011–0.033), CD8+DR+ (β = 0.058, 95% CI 0.041–0.075), and CD8+CD38+ (β = 0.015, 95% CI 0.000–0.030) groups all have positive correlation with the presence of obesity. When combined with a different number of metabolic abnormalities, certain statistical differences in T cell subset counts were also observed between liver steatosis and control groups (Fig. 4). Focused on 1441 subjects of liver steatosis, the number of comorbid metabolic abnormalities also led to significant differences of CD4+, CD4+CD28+, CD4+CD45RA−, CD8+, CD8+CD28+, and CD8+CD38+ T levels in multiple comparisons (Fig. 5 and Table S5). We further divided the liver steatosis group into the lean group and the non-lean group (Fig. 6). We observed that lean subjects tended to exhibit lower levels of CD4+, CD4+CD28+, CD4+CD45RA−, and CD8+ T cells.

Risk for liver fibrosis and lymphocyte subsets

For subjects in the liver steatosis group, the Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores were calculated. The results demonstrated that the majority of subjects were at low risk for liver fibrosis (1167/1441, 81.0%), while 254 cases (17.6%) were at intermediate risk, and only 20 cases (1.4%) had a FIB-4 score exceeding 2.67, indicating a high risk. The intermediate-and high-risk groups exhibited reduced counts across various T cell subsets, except for CD4+CD45RA− and CD8+DR+ T cells (Fig. 7).

Discussion

In this retrospective cross-sectional study, we found that liver steatosis potentially impacted peripheral levels of lymphocyte subsets. The absolute number of B cells, NK cells, and all T cell subsets was significantly higher in participants with liver steatosis, influenced by age, gender, and certain metabolic disorders. In contrast, most percentages of cell subsets and CD4+/CD8+ ratios kept the balance, suggesting variations of proliferation rather than differentiation10,11.

Previous studies have explored immune cell alteration in subcutaneous fat tissue, visceral fat tissue, liver, and blood of fatty liver diseases. B lymphocytes are emerging as mediators of fatty liver disease because of their ability to secrete cytokines and antibodies and promote inflammation. NK cells can kill hepatic stellate cells, critical for developing liver fibrosis12. However, their results were mainly obtained from the liver tissue of experimental models. In practice, few patients would undergo liver biopsy, and we thus turned to peripheral blood. Consistent with observations inside the liver microenvironment, our results showed that peripheral B and NK cell counts of the fatty liver group tended to increase. Furthermore, T cells consist of multiple differentially active subsets, which are sensitive indicators and maintainers of cellular immune status. Concerning liver steatosis, both Th22 and Treg cells appear to have an overall tempering effect, whereas Th17 and Tc cells seem to induce more liver damage and fibrosis progression9. We observed elevated levels of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in peripheral blood. These consistent tissue and peripheral blood changes are suggestive of a systemic immunological abnormal state in patients with liver steatosis. Peripheral blood lymphocyte testing tends to be one of the keys to translating research on pathological immune mechanisms into clinical applications. Akira Kado et al. also found that peripheral memory T lymphocyte frequencies can noninvasively predict severe liver fibrosis and indicate the pathological progression of NAFLD13. However, the specific mechanisms of peripheral immune alterations and comprehensive models integrating clinical indicators and immune profiles need further exploration.

Age and gender are the most common factors influencing lymphocyte phenotypes. Our study also takes this entirely into account. Previous studies have found that age decreased B cell diversity and affected NK cell cytotoxicity, surface phenotype, response to cytokines, and ability to produce IFN-γ14,15,16,17. Our study observed the variation of lymphocyte subsets between controls and liver steatosis patients in younger groups (< 65 years). In particular, liver steatosis did not increase naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in patients older than 65y compared with controls. It is suggested that the effect of liver steatosis on immunity is more pronounced in the young population with relatively higher immunological activity. Only analyzing patients with liver steatosis, there are significant declines of CD28+, CD38+, and naïve T cells with aging. These findings are related to immunosenescence and consistent with previous findings among healthy adults. The decreased naïve T cells, increased memory T cells, and loss of CD28 expression on T cells were significant for the aging of the immune system. There was also an increase of CD8+HLA-DR/CD8+ and a decreasing trend of CD8+CD38+/CD8+ with aging11,18,19. However, in the pathological state of chronic inflammation, our understanding of the characteristics of immunosenescence remains limited.

Gender is another critical factor in immune function partly explained by different sexual hormones20,21. Women have significantly higher levels of naive CD4+ T cells, naive CD8+ T cells, naive B cells, and plasmablasts than males while having a significantly smaller proportion of effector CD8+ T cells21,22. Among healthy adults from the Chinese population, the gender-dependent differences showed higher absolute values of CD3+CD8+, CD8+ central memory, and CD8+ effector memory T cells in males11. In this study, liver steatosis significantly increases the counts of functional and activated subsets of CD8+ cells in males but not in females. These findings showed that the immune system altered differently in different genders. Apart from the effects of sex hormones, more thorough mechanisms responsible for these differences are unclear, and more research based on refined population categorization is needed.

Liver steatosis is increasingly recognized as associated with metabolic abnormalities, prompting the renaming of NAFLD as MAFLD with worldwide attention. The immune response is a common driver of developing fatty liver and metabolism-related diseases. According to the characteristics of subject selection in our study, people with liver steatosis meet non-alcohol classification, and metabolic abnormalities are evaluated as comorbid factors. The combined presence of liver steatosis and metabolic syndrome is common. Only 12% of patients with liver steatosis do not have any metabolic disorders. As previous studies showed, hypertension incidence was inversely associated with circulating proportions of naïve CD4+ helper T cells23. For DM, several cross-sectional studies have observed an expansion of memory and contraction of naive CD4+ cell proportions in the peripheral blood24,25,26,27. Our results also provide additional evidence that memory CD4+ T cells are increased in both hypertension and glucose metabolism disorders.

Obesity influences both functional and memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in our observations, which aligns with other studies demonstrating a peripheral-level inflammatory process in obesity9,28,29. Of 1441 patients with a background of liver steatosis, 1186 reached the definition of obesity in our study. They had higher functional and memory CD4+ T cells and a lower percentage of naïve cells than those without obesity. The consistency of these immune variations supports the immune abnormalities as an essential mechanism in MAFLD. People with NAFLD who do not have obesity are called non-obese NAFLD (also known as lean NAFLD) and are more common, especially in Asian populations30. Lean subjects are more severe for fibrosis, the progression of liver disease, chronic kidney disease, and overall mortality31,32. Our results tentatively found lower CD4+, CD4+CD28+, CD4+CD45RA−, and CD8+ T cells in lean subjects. However, how these cellular immune-related factors are involved in the pathogenesis and prognosis of lean NAFLD remains poorly studied. The intestinal microenvironment and systemic immune homeostasis are likely to be potential hotspots for further exploration of pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic targets33. We also found that a small number of patients did not have any metabolic abnormality in combination despite having liver steatosis, and they have a lower level of immune activation, corresponding to a possible different mechanism.

Our study included a relatively large number of participants from a medical check-up database. Although liver biopsy is the gold standard for liver disease diagnosis or evaluation, ultrasound or CT findings of fatty liver appear to be more representative of the full spectrum of the patient population. However, our study has some further limitations. First, due to the limited tools and information provided by the health check-up report, we could not further analyze the relationship between severity and lymphocyte changes. Second, the patients were all Chinese from a single hospital and 68.8% of the study population is male; thus, further studies are needed to estimate the utility of these associations in different populations. Third, the lack of information on outcomes after long-term follow-up prevented us from exploring the value of lymphocyte subsets in predicting the destination of liver steatosis. We used the FIB-4 score as a simple risk stratification tool and found reductions in counts of multiple subsets, including CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, in moderate-to-high-risk subjects. Chronic inflammation may prompt liver disease progression (such as liver cirrhosis or carcinogenesis) and provide a new direction for seeking noninvasive biological indicators and hazard stratification tools related to liver steatosis. Continuing to broaden the scope of research, the relationship between liver steatosis and extrahepatic malignancies and hematologic malignancies has also been gradually discovered, in which inflammation may be an important link34. The analysis of peripheral blood immune profiles, as a more accessible and informative detection, is anticipated to play a significant role in risk prediction, long-term monitoring, and prognosis management of individuals with liver steatosis.

To summarize, liver steatosis is associated with a chronic, low-intensity inflammatory process. It potentially affects lymphocyte profiles at the peripheral level, interacting with other variables like age, gender, and metabolic abnormalities. Changes in the peripheral lymphocyte subsets may be a promising tool in the comprehensive evaluation of liver steatosis and prediction of progression. We look forward to evidence-based support from more large-scale, multi-population, and prolonged follow-up studies.

Methods

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (I-23PJ018). The informed consent was waived by the institutional ethics committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital due to the retrospective nature and minimal risk posed by this research.

Data source

The data were collected from the Peking Union Medical College Hospital-Health Management database, which was established to keep records of annual medical check-ups of urban residents in Beijing. All clinical data were collected during a half-day clinic visit. Participants had their medical history reviewed by an internal physician, and blood samples were drawn after at least 8 h of fasting.

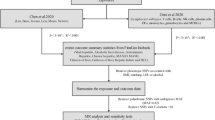

Study population

This study followed and complied with the guidelines established by Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Research in Epidemiology (STROBE). We searched the database from January 2017 to December 2022 and identified 6622 adult subjects (≥ 18 years old) with lymphocyte subtyping test results and complete clinical records. We excluded subjects with previous or current comorbidities through medical history taking, including alcoholic liver diseases, autoimmune diseases, infectious diseases, or malignant diseases. Subjects without abdominal ultrasound or CT were also excluded. The presence of liver steatosis was evaluated by either abdominal CT or ultrasound findings. The CT results were reviewed and interpreted by professional radiologists. A diffuse reduction in liver density and a liver-to-spleen CT attenuation ratio of less than or equal to 1 were considered diagnostic for hepatic steatosis. The ultrasound examinations were performed and interpreted by professional sonographers. The diagnostic features of hepatic steatosis on ultrasound included: increased fine echogenicity of the liver parenchyma (greater than that of the spleen or kidney parenchyma), attenuation of the far-field echo, and poor visualization of the intrahepatic ductal structures.

Lymphocyte immunophenotyping

Immunophenotyping of peripheral blood lymphocytes was analyzed by flow cytometry. EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood was freshly collected. All the samples were prepared and tested directly after being obtained without being cryopreserved. Each blood sample was divided into several specimen test tubes (100 μL/tube) and then incubated in the dark for 15 min at room temperature with different panels of monoclonal antibodies (T and B lymphocyte subsets: CD3-FITC, CD4-PE-Cy7, CD8-APC-Cy7, CD19-APC; functional and activation subsets of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell: CD3-APC-Cy7, CD4-PerCP-Cy5.5, CD8-PE-Cy7, CD28-PE, CD38-APC, HLA-DR-FITC) and isotype controls. To remove contaminating erythrocytes, 2 mL of 10% lysis solution was individually added to each tube. After 15 min, the samples were centrifuged (5 min at 1500 rpm) and resuspended in phosphate buffer saline (PBS). After the second wash, samples were resuspended in 300 μL of PBS and stored at 4 °C in the dark until measurement, which was done within 2 h. Every sample was measured using the FACSCanto II flow cytometer. Before measurement, the optical path was adjusted by testing with the optics calibrator Flow Check (the coefficient of variation should be less than 2%). Data acquisition and analysis were performed with the BD FACSDiva software. A count cycle contained 30,000 cells. Through proper gating and compensation, we could distinguish lymphocytes from other clusters in a forward- versus side-scatter dot plot and then, by use of fluorescence signals, analyze the expression of each lymphocyte subset. In the CD3/SSC scatter plot of the lymphocyte subset, the CD3− lymphocytes were gated. In the CD16&56/CD19 fluorescence scatter plot of the CD3− lymphocytes, the CD19+B cells and CD16&CD56+ NK cells were separately counted. For T cell analysis, CD3+ T lymphocytes were gated in the CD3/SSC scatter plot of the lymphocyte population. In the CD8/CD4 fluorescence scatter plot of the CD3+ T lymphocytes, CD4+CD8− T cells and CD4-CD8+ T cells were identified and counted separately. An example showing gating strategies was included in Supplementary file 2. Cell counts of lymphocyte subsets were calculated using a dual-platform method. The lymphocyte count obtained from blood routine tests of the same specimen was multiplied by the detection results (the proportion of each lymphocyte subset) to obtain the absolute counts of each subset.

Data collection

The collection and statistics of the above lymphocyte immunophenotyping results are based on the electronic medical records of the database. The routine reporting items for lymphocyte subsets testing include white blood cell (cells/μL), lymphocyte (%), lymphocyte (cells/μL), B lymphocyte CD19+ (%), B lymphocyte CD19+ (cells/μL), NK cell CD16+CD56+ (%), NK cell CD16+CD56+ (cells/μL), T lymphocyte CD3+ (%), T lymphocyte CD3+ (cells/μL), CD3+CD4+ T cell (%), CD3+CD4+ T cell (cells/μL), CD3+CD8+ T cell (%), CD3+CD8+ T cell (cells/μL), CD4+CD45RA− T cell (%), CD4+CD45RA− T cell (cells/μL), CD4+CD45RA+ T cell (%), CD4+CD45RA+ T cell (cells/μL), CD4+CD45RA+62L+ T cell (%), CD4+CD45RA+62L+ T cell (cells/μL), CD4+CD28+ (%), CD4+CD28+ (cells/μL), CD8+CD28+ (%), CD8+CD28+ (cells/μL), CD8+DR+ (%), CD8+DR+ (cells/μL), CD8+CD38+ (cells/μL), CD8+CD38+ (cells/μL), and CD4/CD8.

Demographic information and test results of blood routine, ALT, AST, creatine, total cholesterol (TC), triacylglycerol (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), hsCRP were also collected from the database, recording or testing during the medical check-ups. Metabolic dysfunctions were collected from history taking and measurements during health evaluation, including (1) hypertension (blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg, and/or previously diagnosed hypertension with ongoing treatment), (2) abnormal glucose metabolism (fasting plasma glucose ≥ 6.1 mmol/L and/or 2-h postprandial glucose ≥ 7.8 mmol/L, and/or previously diagnosed diabetes with ongoing treatment), (3) hyperlipidemia (fasting TG ≥ 1.7 mmol/L and/or fasting HDL-C < 1.04 mmol/L), (4) obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 or waist circumference ≥ 90 cm in male or 85 cm in female). Subjects with a BMI < 23 kg/m2 were classified into the lean group, while BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 were classified into the non-lean group. FIB-4 score was calculated using the following formula:

Low risk (FIB-4 < 1.3) suggested a low likelihood of significant liver fibrosis. Intermediate risk (1.3 ≤ FIB-4 ≤ 2.67) indicated an intermediate risk of fibrosis, and further evaluation may be needed. High risk (FIB-4 > 2.67) suggested a high likelihood of advanced liver fibrosis or cirrhosis.

Statistical analysis

The continuous variables were presented as medians with an IQR and compared using the Kruskal–Wallis or Mann–Whitney U tests when data did not conform to a normal distribution. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square testing. This study carried out subgroup analyses separately for male and female groups and different age groups. Multivariate linear regression was utilized to examine the relationship between liver steatosis and cell counts of lymphocyte subsets (after log-transformation). The data are presented as coefficients (β) and confidence intervals (CI). Confounding factors were considered to guarantee the precision of the findings. In Model 1, no covariates were accounted for. Model 2 incorporated adjustments for age and gender. Model 3 included adjustments for age, gender, hypertension, abnormal glucose metabolism, hyperlipidemia, and obesity. The probability value was obtained from two-sided tests, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 (Armonk, New York, USA) and R software (version 4.3.1; http://www.R-project.org, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Data availability

All the data related to this study are available from the corresponding author (Tengda Xu, xutd@pumch.cn; Dong Wu, wudong@pumch.cn) upon reasonable request.

References

Furman, D. et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med. 25, 1822–1832 (2019).

Greten, F. R. & Grivennikov, S. I. Inflammation and cancer: Triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity 51, 27–41 (2019).

Bäck, M., Yurdagul, A. Jr., Tabas, I., Öörni, K. & Kovanen, P. T. Inflammation and its resolution in atherosclerosis: Mediators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 16, 389–406 (2019).

Baechle, J. J. et al. Chronic inflammation and the hallmarks of aging. Mol. Metab. 74, 101755 (2023).

Jalla, S. et al. Enumeration of lymphocyte subsets using flow cytometry: Effect of storage before and after staining in a developing country setting. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 19, 95–99 (2004).

Zhou, F. et al. Unexpected rapid increase in the burden of NAFLD in China from 2008 to 2018: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology 70, 1119–1133 (2019).

Eslam, M. et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J. Hepatol. 73, 202–209 (2020).

Sutti, S. & Albano, E. Adaptive immunity: An emerging player in the progression of NAFLD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 81–92 (2020).

Van Herck, M. A. et al. The differential roles of T cells in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and obesity. Front. Immunol. 10, 82 (2019).

Kuss, I., Hathaway, B., Ferris, R. L., Gooding, W. & Whiteside, T. L. Decreased absolute counts of T lymphocyte subsets and their relation to disease in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 3755–3762 (2004).

Xia, Y. et al. Reference range of naïve T and T memory lymphocyte subsets in peripheral blood of healthy adult. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 207, 208–217 (2022).

Bhattacharjee, J. et al. Hepatic natural killer T-cell and CD8+ T-cell signatures in mice with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatol. Commun. 1, 299–310 (2017).

Kado, A. et al. Differential peripheral memory T cell subsets sensitively indicate the severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol. Res. 54, 525–539 (2024).

Gibson, K. L. et al. B-cell diversity decreases in old age and is correlated with poor health status. Aging Cell 8, 18–25 (2009).

Facchini, A. et al. Increased number of circulating Leu 11+ (CD 16) large granular lymphocytes and decreased NK activity during human ageing. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 68, 340–347 (1987).

Solana, R., Campos, C., Pera, A. & Tarazona, R. Shaping of NK cell subsets by aging. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 29, 56–61 (2014).

Almeida-Oliveira, A. et al. Age-related changes in natural killer cell receptors from childhood through old age. Hum. Immunol. 72, 319–329 (2011).

Qin, L. et al. Aging of immune system: Immune signature from peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets in 1068 healthy adults. Aging (Albany NY). 8, 848–859 (2016).

Li, M. et al. Age related human T cell subset evolution and senescence. Immun. Ageing 16, 24 (2019).

Kverneland, A. H. et al. Age and gender leucocytes variances and references values generated using the standardized ONE-study protocol. Cytometry A 89, 543–564 (2016).

Márquez, E. J. et al. Sexual-dimorphism in human immune system aging. Nat. Commun. 11, 751 (2020).

Zalocusky, K. A. et al. The 10,000 immunomes project: Building a resource for human immunology. Cell Rep. 25, 513-522.e3 (2018).

Kresovich, J. K. et al. Peripheral immune cell composition is altered in women before and after a hypertension diagnosis. Hypertension 80, 43–53 (2023).

Olson, N. C. et al. Associations of circulating lymphocyte subpopulations with type 2 diabetes: Cross-sectional results from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). PLoS ONE 10, e0139962 (2015).

Rattik, S. et al. Elevated circulating effector memory T cells but similar levels of regulatory T cells in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Diab. Vasc. Dis. Res. 16, 270–280 (2019).

Bailin, S. S. et al. T lymphocyte subsets associated with prevalent diabetes in veterans with and without human immunodeficiency virus. J. Infect. Dis. 222, 252–262 (2020).

Olson, N. C. et al. Associations of innate and adaptive immune cell subsets with incident type 2 diabetes risk: The MESA study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105, e848–e857 (2020).

Rivera-Carranza, T. et al. The link between lymphocyte subpopulations in peripheral blood and metabolic variables in patients with severe obesity. PeerJ 11, e15465 (2023).

Patel, T. P. et al. Immunomodulatory effects of colchicine on peripheral blood mononuclear cell subpopulations in human obesity: Data from a randomized controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 31, 466–478 (2023).

Ye, Q. et al. Global prevalence, incidence, and outcomes of non-obese or lean non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 739–752 (2020).

Nabi, O. et al. Lean individuals with NAFLD have more severe liver disease and poorer clinical outcomes (NASH-CO study). Hepatology 78, 272–283 (2023).

Do, A. & Lim, J. K. Lean NAFLD is associated with adverse liver events and mortality: Moving beyond BMI. Hepatology 78, 6–7 (2023).

Zhang, W. et al. New aspects characterizing non-obese NAFLD by the analysis of the intestinal flora and metabolites using a mouse model. mSystems 9, e0102723 (2024).

Pontikoglou, C. G., Filippatos, T. D., Matheakakis, A. & Papadaki, H. A. Steatotic liver disease in the context of hematological malignancies and anti-neoplastic chemotherapy. Metabolism 160, 156000 (2024).

Funding

The study was supported by the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (Grant Number 2022-PUMCH-B-032).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Xiaxiao Yan, Jing Li and Tengda Xu. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Xiaxiao Yan and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital approved the study (1-23PJ018).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, X., Li, J., Wang, Q. et al. Peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets of Chinese adults with liver steatosis. Sci Rep 15, 14970 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99510-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99510-x