Abstract

Patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) often struggle with CPAP therapy adherence. The intranasal corticosteroids (INS) alone have not significantly improved CPAP adherence but the combination drugs that faster relieved symptoms were not well studied. This study aimed to assess the combined effectiveness of INS (fluticasone propionate) and intranasal antihistamines (azelastine hydrochloride) in enhancing CPAP adherence and mitigating CPAP-induced rhinitis symptoms in OSA patients. A double-blind, randomized controlled trial with stratified random sampling was conducted at Thammasat University Hospital from March 2022 to March 2023. Participants included OSA patients undergoing CPAP treatment. The patients completed questionnaires and interviews at the baseline, the second week, and one month after starting CPAP therapy, with CPAP usage electronic data collected. Among 116 enrolled patients, most had severe OSA (78.9%), with a majority being male (56.9%). The intervention group did not significantly differ from the placebo group in terms of CPAP usage, nasal symptoms, quality of life, or side effects. Subgroup analysis showed improved CPAP adherence in the treatment group when using pressure below 15 cm H2O (7.8% increase in CPAP usage days, P = 0.04). This study marks the first evaluation of combination drugs for enhancing CPAP therapy adherence in OSA patients. Although these drugs did not significantly enhance overall CPAP adherence, there was a trend toward increasing CPAP adherence in patients using lower pressure levels. Thus, combining fluticasone and azelastine may benefit certain OSA patients. Further research is essential to comprehend and validate these benefits fully.

Clinicaltrials.in.th number TCTR20220308003 (08/03/2022).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a medical condition that has become increasingly common in modern society due to lifestyle factors, affecting 6–17% of the global population1. OSA is caused by impaired upper airway anatomy, relaxation of the upper airway muscles during sleep, resulting in blockage of the airway2. Risk factors associated with the development of OSA include advanced age3, male gender4, obesity5, a large neck circumference6, and a family history of OSA7. Treatment of OSA is crucial as it is linked to neurocognitive function, cardiovascular disease, daytime sleepiness, and depression8,9,10,11,12.

The first line treatment for OSA is continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy13,14, which involves the use of a positive airway pressure device for more than 4 h per night with over 70% adherence15. Studies have shown that the more hours per night the CPAP device is used, the greater the benefits for patients with OSA. The study in male patients with OSA with an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) greater than or equal to 10 per hour found that those who used CPAP had better insulin levels when fasting, were less insulin-resistant, and had better Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) scores than the control group16. Furthermore, it was found that CPAP therapy for at least 4 h per night can reduce sleepiness and increase wakefulness, as well as reduce blood pressure in patients with moderate to severe OSA13,17. Surprisingly, the rate of CPAP device use in patients with OSA is still low, ranging from about 25–50%18,19. Factors contributing to good CPAP adherence depend on age, gender, daytime sleepiness before starting treatment, responsive to CPAP treatment, and OSA symptoms15. However, there are many factors that can be modified to improve patient adherence to CPAP therapy, such as patient education and tele-monitoring, treatment of early nasal inflammation, and ensuring a good initial experience with the device for the first 2–4 weeks15,20,21.

The use of CPAP therapy may induce rhinitis either in animal model or human, also known as positive airway pressure induced rhinitis (PIR)22,23, which can negatively affect the patient’s adherence to therapy and overall quality of life. Therefore, studies have explored the use of intranasal corticosteroids to reduce inflammation in the nasal cavity and increase adherence to CPAP therapy, but the results are still inconclusive24,25,26,27.

Recent research has shown that the combination of intranasal steroids with antihistamines nasal sprays, such as azelastine hydrochloride and fluticasone propionate, provides rapid relief from symptoms within minutes in patients with allergic rhinitis28. This contrasts with the traditional use of intranasal steroids alone, which may take 1–2 weeks to achieve full effectiveness. While this combination therapy has demonstrated its efficacy in relieving symptoms, its potential to enhance adherence to CPAP therapy in patients with OSA remains unexplored. It is plausible that this combination may be more effective in reducing inflammation in the nasal mucosa, thus facilitating more consistent CPAP therapy usage, especially among CPAP-naïve patients with OSA who may experience CPAP-induced rhinitis. The researchers aim to study the efficacy of using azelastine hydrochloride and fluticasone propionate in increasing the rate of CPAP use in patients with OSA.

Methods

Study design and participants

A prospective, randomized, double-blinded placebo-controlled study was conducted at the outpatient department, respiratory diseases, Thammasat University Hospital, Thailand between March 2022 - March 2023. Written informed consent was obtained before trial participation.

Inclusion criteria was patients aged between 18 and 75 years with newly diagnosis of OSA.

Exclusion criteria were (1) newly diagnosed patients with OSA who have previously used intranasal corticosteroids within the past 3 months. (2) elderly patients with neurological disorders associated with impaired cognitive function, such as dementia, stroke, or psychiatric disorders. (3) patients with allergies to azelastine hydrochloride and fluticasone propionate. (4) patients with allergic rhinitis that require treatment with intranasal corticosteroids or intranasal corticosteroids with antihistamine following Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines29. (5) patients with other abnormal sleep disorders, such as narcolepsy, insomnia, parasomnia, or central sleep apnea.

The first trial registration was on 27/12/2021 and ethic approval was obtained from The Human Research Ethics Committee of Thammasat University (Medicine), Thailand (IRB No. MTU-EC-IM-6-330/64) on 19/01/2022, in full compliance with Declaration of Helsinki, The Belmont Report, CIOMS Guidelines and the International Conference on Harmonisation-Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP). All methods were performed in accordance with these guidelines and regulations. All participants provided written informed consent.

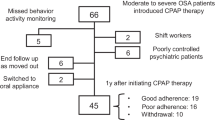

Randomization

Randomization and blinding were carried out by an independent nurse or assistant who was unrelated to the study. Each eligible participant was randomized to 1 of 2 groups by vary from block of 4–8 randomization and stratified random sampling from ESS, age and gender by using computer generated random numbers. The study flowchart is shown in supplementary data e-figure 1. Azelastine hydrochloride and fluticasone propionate nasal spray and placebo were provided by Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chulalongkorn university and were identical by their appearance and taste.

Study intervention

Prior to randomization, patients newly diagnosed with OSA who met the study criteria were contacted and invited to participate in the research project. They were then scheduled to meet with a physician at the outpatient department. After screening and invitation, eligible patients were blinded and randomly divided into two groups. One group received azelastine hydrochloride and fluticasone propionate nasal spray, while the other group received a placebo twice daily for four weeks (as shown in supplementary data e-figure 1). Throughout the entire duration of the follow-up period, patients were consistently administered a regimen of azelastine hydrochloride and fluticasone propionate therapy. To ensure strict compliance with the medication schedule, we provided all participants, across both the placebo and treatment groups, with a concise tabular guide on paper, serving as a daily reminder for medication usage. At baseline, all patients completed questionnaires including the ESS, Total Nasal Symptom Score, Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire, and Visual Analog Scale. Baseline characteristics, physical examination results, patient data, standard patient education, and a ResMed Airsense 10 Elite APAC TRI C CPAP device were collected and provided to patients during their first visit.

The optimal PAP therapy values for every patient were determined through an in-lab polysomnogram with a split-night protocol. This ensured that the pressure titration met the criteria of sleep for at least 15 min, which included supine-REM sleep and AHI of less than 5 events per hour.

Afterwards, at 2 and 4 weeks, patients will be requested to complete questionnaires, including the ESS, Total Nasal Symptom Score, Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire, and Visual Analog Scale, via online form or telephone interview, depending on the patient’s convenience. At week 4, patients will return the CPAP device to collect data on its usage, such as AHI value after treatment, the percentage number of days the CPAP device was used, the percentage of days the CPAP device was used for more than or equal to 4 h per day, the number of hours per day the device was used (average hour/day used), and leakage value (95th percentile leakage). Subject compliance was evaluated by inquiring about the medication or the return of the medication during the follow-up visit at week 4.

Endpoints and assessments

The primary endpoint was the percentage of days the CPAP device was used for more than or equal to 4 h per day. The secondary endpoints were AHI value after treatment, the number of days the CPAP device was used, the number of hours per day the device was used (average hour/day used), and leakage value (95th percentile leakage), ESS, Total Nasal Symptom Score, Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire, and Visual Analog Scale. Adverse events and side effects such as dry throat, nasal congestion, and runny nose were recorded.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated based on the efficacy of intranasal corticosteroids in patients with OSA to increase the use of CPAP devices, 22.6% of patients in the control group did not use the device, and 19% stopped using the device27. To achieve a sufficient statistical power (80%), alpha error 5%, including the estimated withdrawal rate of 10%, 116 patients were required to detect the percentage of days the CPAP device was used for at least 4 h per day difference between the two treatment groups. Categorical data was presented as frequency and percentage (%). Continuous data was presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR), where appropriate. Comparison between the active drugs and placebo, Pearson’s Chi-squared test or Fisher exact test was applied for categorical variables. Student t-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied for continuous variables, where appropriate. Base on intention-to-treat analysis, multi-level mixed effects regression analysis was applied for explore the efficacy of active intervention, confounding variables and effect modification. A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using program STATA version 17.0.

Results

A total of 116 patients diagnosed with OSA were enrolled in the study following randomization. Sixteen patients were lost to follow-up or had incomplete questionnaires, resulting in a full analysis of 116 patients, assuming zero usage for those who discontinued the intervention or had incomplete data. For the secondary endpoint analysis, questionnaire assessments were conducted with 100 patients, and CPAP data usage was available for 107 patients. The majority of participants were aged under 60, with 83.6% being 60 years old or younger. Most patients had severe OSA, with 80.2% falling into this category. Notably, there was no significant difference in optimal pressure between the intervention and placebo groups, as detailed in Table 1 and e-Table 1 in supplementary data.

Primary outcomes

The percentage, median (IQR), of days the device was used for at least 4 h was not significantly different between the intervention group (56.5%, 17 [IQR 84]) and the placebo group (46%, 17 [IQR 80) (P = 0.74) (as shown in supplementary data e-Table 2.1, e-Figure 5).

The percentage of patients who used the device for 70% or more between the active and placebo groups also did not reach statistical significance, with a risk ratio of 1.25 (95% CI 0.74–2.10) and P = 0.40 (as shown in Table 2).

Secondary outcomes

Results from all questionnaires exhibited no significant differences between the two groups at all time points, including total nasal symptom scores and Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life, both in the first two weeks and after four weeks, as well as visual analog scales. Furthermore, most side effects showed no significant differences, including dry throat, runny nose, and nasal congestion, although a trend towards increased nasal congestion in the intervention group was observed (P = 0.055). Notably, there was a significant increase in reports of bitter taste in the intervention group compared to the placebo group (P = 0.001), and one adverse event involving incorrect nasal spray administration resulting in epistaxis in one patient. Additionally, there was no statistically significant difference in detailed CPAP device usage between the two groups, including leakage (L/min), percentage of day usage, and average daily usage (Hr), as presented in Tables 3 and 4 and supplementary e-Figs. 2, 3 and 4 and e-Table 5.

Subgroup analysis

Patients with OSA using a pressure level below 15 cm H2O showed significantly improved adherence to CPAP therapy compared to the placebo group, with a difference of 7.83 (95% CI = 0.37–15.29) and a P-value of 0.04 (as shown in supplementary data e-Figure 56).

Discussion

Our study is the first randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled study conducted in three stratified study groups based on ESS, age, and gender which affect the adherence. We aimed to investigate the potential benefits of azelastine hydrochloride and fluticasone propionate nasal spray in improving adherence to CPAP therapy in patients with OSA. However, we found no statistically significant difference in adherence between the intervention and placebo groups, and no significant differences in the measured outcomes. We acknowledge the limitations of our study, including a high rate of incomplete questionnaires. Our findings align with a previous systematic review and meta-analysis24 that also showed no significant improvement in CPAP adherence with intranasal corticosteroids in patients with OSA. However, the available studies had limitations such as small sample sizes, heterogeneous populations, and variations in interventions and outcome measures. In a previous study25, patients who received fluticasone propionate had significantly higher CPAP adherence and improved sleep quality compared to the control group. However, their study did not stratify the population based on certain factors, and they used self-reported adherence as the primary outcome measure, while we used objective measures. These differences in study design and outcome measures could explain the different results observed between the two studies. Adherence to CPAP therapy is a complex behavior influenced by various factors. While 4 weeks may be sufficient to observe changes in some aspects of adherence. Different measurement methods and patient-centered outcomes should also be considered to assess adherence rates.

In subgroup analysis, revealed the trend of patients with OSA who utilized pressure levels below 15 cm H2O demonstrated significantly improved adherence to CPAP therapy compared to the placebo group. These findings align with previous studies that have highlighted the importance of comfort and tolerance in predicting adherence to CPAP therapy. Lower pressure levels have consistently been associated with increased comfort and better tolerability for patients30,31. So that the patients in these group may gain benefit from the combination drug. Conversely, the benefits observed in the lower pressure group, the higher-pressure levels may present challenges that cannot be adequately addressed by the medications alone. Alternative treatment approaches, such as bilevel positive airway pressure, have been shown to be well-tolerated and effective in patients with OSA who use pressure more than 15 cm H2O32,33.

The secondary outcomes found no significant differences between the intervention and placebo groups in scores related to nasal symptoms, quality of life, and visual analog scales. Detailed usage of the CPAP device, including leakage, percentage day usage, and average daily usage, also showed no significant differences between the groups. Although the intervention group exhibited slightly improved CPAP usage and scores for nasal symptoms and quality of life compared to the placebo group, these differences did not reach statistical significance. These results may be attributed to the fact that we recruited patients with OSA without significant nasal symptoms, potentially masking the effects of the combination drug and resulting in an underpowered study. Therefore, the addition of corticosteroid with antihistamine nasal spray alone to CPAP therapy does not seem to have a significant impact on adherence or device usage.

Regarding side effects, most were not significantly different between the intervention and placebo groups, except for a significant increase in reports of bitter taste in the intervention group. The study also reported one adverse event related to incorrect nasal spray administration causing epistaxis in one patient.

In an attempt to control for other factors that could affect CPAP adherence, a study was conducted that controlled the device type, mask type, and humidity initiation. The study aimed to observe the effects of the intervention on CPAP adherence due to PIR within a retention period of one month. This timeframe was considered to be sufficient to evaluate the impact of the intervention on CPAP adherence.

These findings highlight the significance of individualizing pressure settings in CPAP therapy for patients with OSA, considering factors such as patient comfort, tolerance, and the potential need for alternative treatment modalities. In cases where high pressure levels are required, alternative strategies such as Bi-level positive airway pressure (BPAP) or other interventions may be necessary to optimize therapy and improve adherence.

Conclusion

Our study revealed promising findings suggesting potential benefits of azelastine hydrochloride and fluticasone propionate nasal spray for patients with OSA who use lower pressure levels in their CPAP therapy. These findings indicate a potential positive effect of the nasal spray in this particular subgroup. However, it is important to note that the lack of statistical significance and the high rate of incomplete questionnaires and loss to follow-up limit the certainty of these findings. Further research focusing on a specific subgroup of patients is necessary to validate and explore this potential effect. Additionally, investigating the optimal duration of treatment and identifying specific patient populations that may benefit from the nasal spray as an adjunct to CPAP therapy are important areas for future investigation.

Study limitations

While our study offers valuable insights into interventions targeting CPAP adherence in patients with OSA, certain limitations should be considered. A notable rate of incomplete questionnaires introduced the potential for response bias, impacting the precision of our results. Efforts to mitigate this limitation through clear instructions and reminders were made, but concerns persist about the extent of its influence. Our study population mainly comprised severe OSA patients, potentially influencing results, as they typically exhibit better CPAP adherence due to more symptoms. Additionally, our recruitment strategy, focusing on patients with OSA without significant nasal symptoms, may have resulted in an underpowered study, potentially obscuring the true impact of the combination drug on CPAP adherence. Despite these challenges, our study represents a substantial contribution to the field, emphasizing the need for ongoing efforts to refine study designs and address complexities inherent in this research domain.

Data availability

Data is available on your reasonable request by emailing to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- OSA:

-

Obstructive sleep apnea

- CPAP:

-

Continues positive airway pressure

- INS:

-

Intra-nasal corticosteroid

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- AHI:

-

Apnea-hypopnea index

- cm:

-

Centimeter

- mmHg:

-

Millimeters of mercury

- ESS:

-

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- PIR:

-

positive airway pressure induced rhinitis

- ARIA:

-

Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma

- ICH-GCP:

-

The International Conference on Harmonisation-Good Clinical Practice

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- BPAP:

-

Bi-level positive airway pressure

- Hr:

-

Hour

References

Senaratna, C. V. et al. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 34, 70–81 (2017).

Eckert, D. J., White, D. P., Jordan, A. S., Malhotra, A. & Wellman, A. Defining phenotypic causes of obstructive sleep apnea. Identification of novel therapeutic targets. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 188 (8), 996–1004 (2013).

Young, T. Rationale, design and findings from the Wisconsin sleep cohort study: Toward Understanding the total societal burden of sleep disordered breathing. Sleep Med. Clin. 4 (1), 37–46 (2009).

Tufik, S., Santos-Silva, R., Taddei, J. A. & Bittencourt, L. R. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in the Sao Paulo epidemiologic sleep study. Sleep Med. 11 (5), 441–446 (2010).

Mortimore, I. L., Marshall, I., Wraith, P. K., Sellar, R. J. & Douglas, N. J. Neck and total body fat deposition in Nonobese and obese patients with sleep apnea compared with that in control subjects. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 157 (1), 280–283 (1998).

Davies, R. J., Ali, N. J. & Stradling, J. R. Neck circumference and other clinical features in the diagnosis of the obstructive sleep Apnoea syndrome. Thorax 47 (2), 101–105 (1992).

Mukherjee, S., Saxena, R. & Palmer, L. J. The genetics of obstructive sleep Apnoea. Respirol. (Carlton Vic). 23 (1), 18–27 (2018).

Nieto, F. J. et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep. Heart Health Study Jama. 283 (14), 1829–1836 (2000).

Peppard, P. E., Young, T., Palta, M. & Skatrud, J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 342 (19), 1378–1384 (2000).

Gottlieb, D. J. et al. Prospective study of obstructive sleep apnea and incident coronary heart disease and heart failure: The sleep heart health study. Circulation 122 (4), 352–360 (2010).

Redline, S. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea and incident stroke: The sleep heart health study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 182 (2), 269–277 (2010).

Young, T. et al. Sleep disordered breathing and mortality: Eighteen-year follow-up of the Wisconsin sleep cohort. Sleep 31 (8), 1071–1078 (2008).

Patil, S. P. et al. Treatment of adult obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure: An American academy of sleep medicine clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. JCSM Off. Publ. Am. Acad. Sleep. Med. 15 (2), 335–343 (2019).

Akashiba, T. et al. Sleep apnea syndrome (SAS) clinical practice guidelines 2020. Respir. Invest. 60 (1), 3–32 (2022).

Sawyer, A. M. et al. A systematic review of CPAP adherence across age groups: Clinical and empiric insights for developing CPAP adherence interventions. Sleep Med. Rev. 15 (6), 343–356 (2011).

Lindberg, E., Berne, C., Elmasry, A., Hedner, J. & Janson, C. CPAP treatment of a population-based sample–What are the benefits and the treatment compliance? Sleep Med. 7 (7), 553–560 (2006).

Cao, M. T., Sternbach, J. M. & Guilleminault, C. Continuous positive airway pressure therapy in obstuctive sleep apnea: Benefits and alternatives. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 11 (4), 259–272 (2017).

Wang, Y., Gao, W., Sun, M. & Chen, B. Adherence to CPAP in patients with obstructive sleep apnea in a Chinese population. Respir. Care. 57 (2), 238–243 (2012).

RotenbergBW, Murariu, D. & Pang, K. P. Trends in CPAP adherence over Twenty years of data collection: A flattened curve. J. Otolaryngol. - head Neck Surg. = Le J. d’oto-rhino-laryngologie Et De Chirurgie Cervicofac. 45 (1), 43 (2016).

Popescu, G., Latham, M., Allgar, V. & Elliott, M. W. Continuous positive airway pressure for sleep Apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome: usefulness of a 2 week trial to identify factors associated with long term use. Thorax 56 (9), 727–733 (2001).

Ghadiri, M. & Grunstein, R. R. Clinical side effects of continuous positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep Apnoea. Respirol. (Carlton Vic). 25 (6), 593–602 (2020).

Almendros, I. et al. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) induces early nasal inflammation. Sleep 31 (1), 127–131 (2008).

Brimioulle, M. & Chaidas, K. Nasal function and CPAP use in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: A systematic review. Sleep. Breath. = Schlaf Atmung. 26 (3), 1321–1332 (2022).

Charakorn, N., Hirunwiwatkul, P., Chirakalwasan, N., Chaitusaney, B. & Prakassajjatham, M. The effects of topical nasal steroids on continuous positive airway pressure compliance in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. Breath. = Schlaf Atmung. 21 (1), 3–8 (2017).

Segsarnviriya, C., Chumthong, R. & Mahakit, P. Effects of intranasal steroids on continuous positive airway pressure compliance among patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. Breath. = Schlaf Atmung. 25 (3), 1293–1299 (2021).

Ryan, S., Doherty, L. S., Nolan, G. M. & McNicholas, W. T. Effects of heated humidification and topical steroids on compliance, nasal symptoms, and quality of life in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome using nasal continuous positive airway pressure. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. JCSM Off. Publ. Am. Acad. Sleep. Med. 5 (5), 422–427 (2009).

Strobel, W. et al. Topical nasal steroid treatment does not improve CPAP compliance in unselected patients with OSAS. Respir. Med. 105 (2), 310–315 (2011).

Carr, W. et al. A novel intranasal therapy of azelastine with fluticasone for the treatment of allergic rhinitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 129 (5), 1282–9e10 (2012).

Bousquet, J. et al. Next-generation allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) guidelines for allergic rhinitis based on grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE) and real-world evidence. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 145 (1), 70–80e3 (2020).

Weaver, T. E. & Grunstein, R. R. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: The challenge to effective treatment. Proc. Am. Thoracic Soc. 5(2), 173–178 (2008).

Catcheside, P. G. Predictors of continuous positive airway pressure adherence. F1000 Med. Rep. 2, (2010).

Clinical Guidelines for the Manual Titration of Positive. Airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 04 (02), 157–171 (2008).

Ishak, A., Ramsay, M., Hart, N. & Steier, J. BPAP is an effective second-line therapy for obese patients with OSA failing regular CPAP: A prospective observational cohort study. Respirol. (Carlton Vic). 25 (4), 443–448 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chulalongkorn University, for providing the drug and placebo in this study. This work was supported by Sleep center of Thammasat (SCENT) and Medical Diagnostics Unit (MDU), Thammasat University Hospital, Thailand.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledged the research fund provided by Thammasat University Hospital (Contact number. 3-2565.2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was conducted in collaboration with the Sleep Center of Thammasat University Hospital and the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chulalongkorn University. We declare no conflicts of interest for RW, CT, JK, TS, KY and WC. Their involvement in this research was solely focused on advancing scientific understanding and improving patient outcomes in the field of obstructive sleep apnea and CPAP adherence. We affirm our commitment to transparency and scientific integrity in reporting the findings of this study. All authors reviewed the data and contributed to its interpretation, edited the manuscript, and approved the final submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was obtained from The Human Research Ethics Committee of Thammasat University (Medicine), Thailand (IRB No. MTU-EC-IM-6-330/64). The study was conducted in full compliance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, The Belmont Report, CIOMS Guidelines, and the International Conference on Harmonisation-Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP). All research methods and procedures adhered strictly to these established ethical guidelines and regulations. Prior to participation, written informed consent was obtained from all study participants, ensuring transparency and ethical conduct throughout the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wongchan, R., Tepwimonpetkun, C., Kitsongsermthon, J. et al. The efficiency of azelastine hydrochloride and fluticasone propionate nasal spray to improve PAP adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sci Rep 15, 14601 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99548-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99548-x