Abstract

Childhood and adolescent obesity has become one of the most serious public health problems worldwide, and obesity may have potential effects on kidney health. The urinary albumin creatinine ratio (UACR) is a sensitive indicator for assessing renal impairment. Relevant studies on pediatric and adolescent populations are more limited and controversial. This study aimed to clarify the relationship between UACR and overweight/obesity in children and adolescents in the United States, thereby providing new insights and recommendations for the clinical management and prevention of kidney disease. This study utilized data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2011 to 2016. Variables were derived from demographic, examination, and laboratory data. Overweight/obesity status was assessed using BMI criteria, and random urine samples were used to measure UACR. The association between UACR and overweight/obesity was assessed using descriptive statistics, multivariate logistic regression analysis, subgroup analysis, and curve-fitting analysis. In this study of 4116 participants aged 8–19, multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed a significant negative association between UACR and overweight/obesity (OR = 0.32; 95% CI 0.26–0.38; P < 0.001). The interaction P-values were all greater than 0.05 in the interaction of subgroups, indicating that the findings were very stable and consistent between subgroups. In addition, smoothed curve fitting and threshold effect analyses revealed a nonlinear relationship between UACR and overweight/obesity, with an inflection point for log(UACR) determined to be 1.435 mg/g. The findings suggest a significant nonlinear negative correlation between UACR and overweight/obesity in the pediatric and adolescent populations. Until a precise mechanism of association is found, maintaining a standard range of BMI in all age groups may reduce the incidence of albuminuria in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Childhood and adolescent obesity has become one of the most serious public health problems facing the world in the 21st century1. Statistics for 2023 indicate that 1 in 5 children and adolescents in the world are addressing overweight issues2. The World Obesity Federation predicts that by 2030, 254 million children and adolescents will be diagnosed with obesity3. As the fifth leading risk factor for mortality, obesity is not only a significant contributor to metabolic syndrome, hypertension, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease but also potentially damaging to kidney health. Overweight and obesity adversely affect the intellectual, behavioural, psychological, and sexual development of children and adolescents and place a significant burden on the health care system4,5. Therefore, research on risk indicators associated with overweight in children and adolescents is critical and will assist clinicians in monitoring, preventing, and regulating the development of obesity.

The urinary albumin creatinine ratio (UACR) is an accurate assessment of urinary protein excretion rate, and the test requires only a single, randomly collected morning urine, which is not affected by hydration and has the advantage of being a simple and volume-neutral procedure compared to 24-hour urine protein collection6. In the early stages of kidney injury, urinary albumin reflects the impairment of glomerular filtration and may also affect tubular function through various mechanisms7. Studies have shown that urinary albumin is taken up by renal tubular epithelial cells after entering the renal tubules and accumulates, activating local inflammatory responses and oxidative stress. The accumulation of high urinary albumin levels in renal tubular epithelial cells can trigger cellular injury, membrane disruption, and protein degradation by promoting the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)8. In addition, urinary albumin can activate the intrinsic immune response of renal tubules, primarily through the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome, which further promotes the release of inflammatory factors (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, etc.) and exacerbates the process of renal tubular cell injury and fibrosis9. It was also found that urinary albumin promoted the development of renal interstitial fibrosis by promoting the release of fibrogenic factors such as transforming growth factor-β10. Thus, urinary albumin is not only a marker of glomerular injury but also indicates that tubular function has been compromised, suggesting that the overall function of the kidney is being challenged. Through this mechanism, elevated UACR can be used as an important indicator to monitor early renal injury, reflecting impaired glomerular filtration and revealing that tubular functional damage may have occurred. In addition, abnormalities in UACR are associated with the development of cardiovascular disease11, hypertension12, obesity13 and other diseases14,15. Some studies have confirmed a significant positive correlation between obesity and albuminuria in adults. This may be because obesity activates the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin system to over-perfuse the glomeruli or promotes the release of adipokines and produces chronic inflammation, which ultimately destroys the glomerular filtration barrier and leads to the development of albuminuria16. However, the number of studies on children and adolescents is still minimal and inconsistent; large samples are needed.

BMI is widely used in the assessment of childhood obesity because of its simplicity, broad applicability, clear association with health risks, and availability for long-term dynamic monitoring17. However, there is relatively limited research on the correlation between UACR and overweight/obesity as determined by body mass index (BMI) in groups of children and adolescents aged 8–19 years, and even fewer studies for U.S. populations. Therefore, we used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2011 to 2016 to conduct a large-sample cross-sectional study to validate further and examine the association between UACR and overweight/obesity in children and adolescents.

Materials and methods

Survey description and study participants

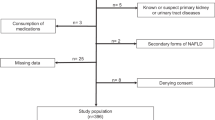

This study used cross-sectional data from NHANES from 2011 to 2016. We chose the NHANES (2011 to 2016) dataset based primarily on its representativeness and data quality. This period provides data on health, nutrition, and laboratory tests for a broadly covered and well-sampled population of children and adolescents, with high accuracy and reliability, especially in measuring key health indicators such as UACR and BMI. NHANES data from this period are widely used in academia and can provide a solid analytic foundation for potential relationships between obesity and kidney function. Second, this period completely avoids the impact of the novel coronavirus epidemic in 2019 and is free from central missing data and statistical bias, enabling more accurate study results. NHANES assesses individuals’ health and nutritional status in the United States using a complex stratified multistage probability sampling methodology. The National Center approved the survey protocol for the Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Twenty-nine thousand nine hundred-two individuals participated in the NHANES study between 2011 and 2016. Of these, 6,645 were children and adolescents aged 8–19 years. After screening, 344 individuals did not have BMI data, 451 lacked UACR data, and 1,995 lacked covariate data, resulting in 4,116 eligible testers being included in the study. The screening process for inclusion in the study is shown in Fig. 1.

Definition of overweight and obesity

Professional health technicians at a mobile screening centre measured participants’ height and weight18,19. We assessed whether individuals were overweight/obese using BMI, calculated as weight (kg) divided by the square of height (m). Based on gender-specific CDC growth charts published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2000. BMI of individuals aged 6–19 years was categorized into four groups and identified overweight and obese populations: underweight (BMI < 5th percentile), normal weight (5th percentile ≤ BMI < 85th percentile), overweight (85th percentile ≤ BMI < 95th percentile), and obese (BMI ≥ 95th percentile).

Determination of UACR

The urine samples provided by the participants were randomized, the subjects were not required to undergo specific preparations at the time of collection, and the time of collection was not influenced by the amount of water consumed or postprandial status. This approach facilitates large-scale data collection and is not dependent on the amount of urine excreted by the subject at a given time, making it highly clinically useful. The collected urine samples are immediately transferred to cryogenic (−30 °C) storage conditions to ensure stability during transportation and accuracy of analysis. After cryopreservation, the urine sample is sent to a laboratory at the University of Minnesota for further analysis. Urine albumin and urine creatinine concentrations in the urine samples were determined by solid-phase fluorescence immunoassay and Roche/Hitachi Modular P chemistry analyzer, respectively20,21. Measurements of urinary albumin (in µg/mL) and urinary creatinine (in mg/dL) concentrations were ultimately converted to urinary albumin creatinine ratios (UACR), which are reported in mg/g. The UACR serves as a sensitive indicator for assessing renal impairment and is a valuable reflection of renal tubular function and the health of the renal barrier. All urine samples were subjected to strict quality control during data collection and laboratory analysis to ensure data consistency and comparability. Laboratory equipment and methods are by international standards, and certified technicians analyze all samples.

Covariate

By summarizing previous studies and incorporating clinical implications, we concluded that mixed effects are important in multivariate analyses. We included the following covariates that may have influenced the study results to ensure the results’ stability and scientific validity. Participant demographics included sex (male or female), age, race (Mexican American, other Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or other race), height, poverty-to-income ratio (PIR), and physical activity (Active, Moderate, Low). Of these, we categorized physical activity according to WHO recommendations, with those aged 8 to 12 years and those aged 12 years and older assessed using 60-minute days of moderate or vigorous activity per week and MET scores, respectively. Low activity level (Low) was defined as no more than 2 days of 60-minute moderate/vigorous activity or a total MET of less than 1500; Moderate activity level (Moderate) was defined as 60 min or more of moderate/vigorous activity on 3–4 days or a total MET of 1500–2999; and High activity level (Active) was defined as 60 min of moderate/vigorous activity on at least 5 days or a total MET of 3000 or more. Laboratory data included serum cotinine, white blood cell count (WBC), eosinophils (EOS), neutrophil percentage (NEUT%), hemoglobin (Hb), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and total cholesterol (TC). Dietary data included energy intake, protein intake, and total sugar intake. Hypertension (yes/no) was determined from systolic/diastolic blood pressure (SBP/DBP) in the screening data. The American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical Practice Guidelines state that in children 8–12 years of age, a systolic/diastolic blood pressure percentile scale based on age, height, and gender is used to define1 SBP and/or DBP ≥ 95th percentile; and2 SBP ≥ 130 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥ 80 mm Hg. Adolescents 13 to 19 years of age are characterized as having SBP ≥ 130 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥ 80 mm Hg. or DBP ≥ 80 mmHg.

These covariates were included to control for potential confounders. Expressly, inflammatory and immune markers (e.g., WBC, EOS, NEUT%) may reflect an obesity-induced chronic low-grade inflammatory state, which may affect UACR levels through glomerular injury; lipids and metabolism-related markers (HDL-C, TC, and Hb) may affect tubular function through oxidative stress, lipotoxicity, or insulin resistance; whereas changes in blood pressure and cotinine levels may influence urinary protein excretion via vascular dysfunction and glomerular hyperperfusion further affect urinary protein excretion; and diet and exercise patterns may combine to affect UACR levels through changes in energy metabolism, lipid metabolism, and insulin sensitivity.

Statistical methods

Descriptive analyses were performed on the baseline information of all participants in this study. The statistical analyses involved were performed using R software (version 4.1.3) and Empower Stats (version 2.0), and the test of significance was two-sided with a significance level of P < 0.05. Participants with missing data on covariates were excluded from this study to make the analysis more accurate. Different representation and testing methods were used depending on the nature and type of data. Mean, standard deviation (SD), or median interquartile range (IQR) were used to represent the collected continuous variables, and a t-test was applied for analysis. Categorical variables were represented by percentages (%) and analyzed using a chi-square test. Subsequently, the data were analyzed using multivariate logistic regression to explore the correlation between UACR and overweight and obesity. Model 1 was not adjusted for any covariates; Model 2 took into account key demographic factors, including gender, age, and ethnicity; and Model 3 was a fully adjusted model with PIR, serum cotinine, WBC, EOS%, NEUT%, Hb, HDL-C, TC, physical activity, hypertension, energy intake, protein intake, and total glucose intake added in. Subgroup analyses based on age, sex, race, cotinine exposure, hypertension, and physical activity were also performed to explore whether there were potential differences in the association between UACR and overweight and obesity in specific populations. Finally, we used restricted cubic spline curve (RCS) fitting to assess possible associations between UACR and overweight and obesity more accurately.RCS is a flexible method for dealing with nonlinear relationships in regression models by placing several “nodes” within the range of values of the independent variable and stitching a series of cubic polynomial segments into a single variable. By setting several “nodes” within the range of values of the independent variable, a series of cubic polynomial segments are stitched together to form a smooth, continuous curve, thus more accurately reflecting the complex relationship between the independent variable and the outcome variable.

Results

Clinical baseline characteristics of the subjects

Table 1 demonstrates the baseline characteristics of the study population stratified by whether they were overweight/obese. Of the 4,116 individuals who met the inclusion criteria and participated in the survey, 1,604 were categorized as overweight/obese, a prevalence of 38.96%. In terms of racial distribution, 27.16% of participants were Non-Hispanic White, followed by Non-Hispanic Black (24.95%), Mexican American (21.91%), and other racial groups (14.80%). Mexican Americans were less represented in the Non-Overweight/Obese group (18.67%) than in the Overweight/Obese group (27.00%). The median age of the participants was 13 years. Figure 2 visualizes the sex and age distribution of the study population, which was roughly symmetrical, with no significant difference in the prevalence of overweight/obesity between the two (P > 0.05). The non-overweight/obese population had a significantly lower median UACR (10 vs. 7; P < 0.001) and a significantly lower prevalence of hypertension compared with the overweight/obese group.

The subjects were categorized into four groups based on the quartiles of the UACR, and this was used as a dependent variable to observe the associations with other variables. The results are shown in Table 2. Group 1 UACR contained values from 0.22 to 5.23, group 2 contained values from 5.23 to 8.18, group 3 contained values from 8.18 to 15.8, and group 4 contained values from 15.8 to 2793.3. Interestingly, we found significant differences in gender and age between the groups, while the differences in hypertension and total sugar intake were not significant, unlike the results in Table 1. The prevalence of overweight/obesity in children decreased significantly as the UACR of the subjects increased (Q1:50.68%; Q2:44.60%; Q3:35.60%; Q4:25.05%; p < 0.001).

Relationship between UACR and overweight/obesity

Table 3 shows the results of univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses, which demonstrate the corroboration of the association between overweight/obesity and UACR (converted to natural logarithm) by comparing the effect estimates under different models. In model 1, which was not adjusted for any covariates, there was a significant negative association between UACR and the prevalence of overweight/obesity (OR = 0.37; 95% CI 0.31–0.44; P < 0.001). Model 2 considered the major demographic factors of age, gender, and race in the analysis, and the results suggested that this significant negative correlation remained (OR = 0.32; 95% CI 0.26–0.38; P < 0.001). Model 3 adjusted for all confounders that could affect the results, and each unit increase in UACR after conversion to natural logarithms was associated with a 68% reduction in overweight/obesity prevalence (OR = 0.32; 95% CI 0.26–0.38; P < 0.001). We transformed the continuous variable UACR into quartiles and subsequently performed sensitivity analyses, using the first group of quartiles as the reference control. The results showed that in Model 1, the prevalence of overweight/obesity was 67% lower among participants in the highest UACR quartile group compared with the reference group (OR = 0.33; 95% CI 0.27–0.39; P < 0.001), with a statistically significant difference between the two groups. This significant difference persisted in Model 2 and Model 3, with an even more significant reduction in the incidence of overweight/obesity in participants in the fourth group of Model 3 compared with the first group (OR = 0.27; 95% CI 0.21–0.33; P < 0.001). There was also trend variability in the negative correlation between UACR and overweight/obesity among the four groups in the three models (P for trend < 0.001).

Subgroup analysis

To further validate the correlation between UACR and overweight/obesity, we performed six subgroup analyses using logistic regression models. The results, as shown in Fig. 3, showed that UACR was negatively associated with overweight/obesity in the total population (OR = 0.31; 95% CI 0.25–0.38; P < 0.001), and this negative correlation was evident across age groups, gender, race, passive smoking status, and physical activity level (P < 0.01). However, we found that this association was missing in the hypertensive population. The P values for the interactions in all subgroups were more significant than 0.05, indicating that the findings were stable and consistent, demonstrating the robustness of the association between UACR and overweight/obesity.

Nonlinear relationship between UACR and overweight/obesity

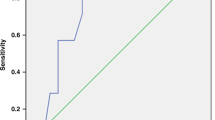

To explore the dose-response relationship between UACR and overweight/obesity, we performed curve fitting using the RCS model, adjusting for all covariates. As shown in Fig. 4, there was an overall negative correlation between UACR and overweight/obesity. However, this relationship showed an L-shaped curve on the graph, which was in a nonlinear pattern, with the curve trend tending to be linear at first and then smoothing out after a particular node (P-nonlinear = < 0.001). The results of the segmented logistic regression model (Table 4) showed that when the logarithmized UACR was less than 1.435 mg/g, OR = 0.21 (0.15, 0.29), P < 0.001, indicating that the effect of UACR on overweight/obesity was a significant negative correlation, and when the logarithmized UACR was more incredible than 1.435, OR = 0.72 (0.43, 1.21 ), P = 0.216, suggesting that the effect of UACR on overweight/obesity was not significant. Therefore, we regarded 1.435 as the cut-off value in the nonlinear relationship.

Discussion

The present study is the first to explore the association between UACR and overweight/obesity (assessed based on BMI as a criterion) in a US national cohort of children and adolescents aged 8 to 19. This study found a significant nonlinear negative association between UACR and overweight/obesity and, for the first time, proposed a critical inflection point for UACR (log(UACR) = 1.435 mg/g), where the negative association with the prevalence of overweight/obesity was significant when UACR was below the inflection point. In contrast, the relationship became insignificant or even non-associated when UACR levels were high. This finding suggests that UACR may reflect the dynamic process between obesity and kidney damage, providing new clues for identifying obesity-related early kidney damage. In addition, to address potential confounders, we systematically included multifaceted covariates that may affect the independent variables to adjust for them entirely. We validated the independence and applicability of UACR as an early marker of kidney damage in a population of overweight/obese children. Although a causal relationship could not be confirmed, the nonlinear characteristics and their inflection points revealed in this study provide an important reference for future mechanism exploration and precise prevention and control of obesity-related renal pathology, as well as a potential biological basis for dynamic monitoring of renal health in children and adolescents. Although the findings suggest that the group with higher UACR showed a lower prevalence of overweight/obesity, the specific range of BMI beneficial to the kidneys still needs to be further explored. We believe that high BMI increases health risks and ultimately remains potentially damaging to the kidneys. Moreover, maintaining a BMI within the normal range for all age groups may help reduce the incidence of albuminuria.

Current studies have demonstrated that obesity can be a major contributor to kidney disease by inducing oxidative stress, lipotoxicity, and renal tubular cell injury22. Obesity can lead to associated glomerular diseases with pathologic features, including glomerulomegaly, mild cytosis, variable widening of the tethered area, glomerular basement membrane thickening, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis23. A growing body of evidence24,25,26 suggests that the underlying mechanisms for developing this type of disease focus on the pro-inflammatory state of obesity, increased levels of oxidative stress, and an over-activated renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Relevant studies27,28,29 in adults have confirmed a positive association between obesity and albuminuria, which is consistent with current knowledge. However, this relationship remains controversial in pediatric and adolescent populations. Researchers have explored the association between BMI and albuminuria in pediatric populations to some extent, with results suggesting either no association or a positive correlation30,31,32. In recent years, however, scientists have questioned this conclusion. An Australian cross-sectional study33 of 975 children found that albuminuria was less common in overweight and obese children. Valentina Gracchi et al.34 found a negative correlation between albuminuria and body mass index in 12-year-old children in the Netherlands. A cross-sectional study35 showed a negative correlation between body roundness index and albuminuria in children and adolescents in the United States. However, the mechanism behind this subtle relationship is not well understood. Our study found an L-shaped nonlinear negative correlation between UACR and overweight/obesity. This is similar to the overall trend obtained from Valentina Gracchi et al. However, our study further reveals this trend’s turning point, clarifying the negative correlation’s intense association interval and providing direction for clinical disease tracking and diagnostic prediction. Overall, however, both studies emphasize the complex relationship between UACR and obesity.

The following nine studies(Table 5) examined the association between proteinuria and obesity in children and adolescents, with participants on five continents ranging in age from 5 to 19 years. Three studies (Nos. 1–3) suggested a positive or equivocal association. 5–9, although they all concluded a positive association, none of them analyzed proteinuria and obesity simultaneously as a significant study, and the correlation was only obtained through a simple data correlation analysis. 4 assessed obesity using the Body Circularity Index (BCI), which was demonstrated to have a negative correlation with proteinuria. We conducted a re-study based on the above inconsistencies in correlations, taking obesity and proteinuria as research objects, exploring their specific correlation patterns in-depth, and evaluating obesity by BMI to promote the generalizability of the results to the clinic. All these studies have contributed to the advancement of the field and laid the foundation for further exploration in the future.

Our study reaffirmed the existence of a negative correlation between overweight/obesity and albuminuria in the pediatric and adolescent population through a US cohort and also unexpectedly found that higher HDL-C accompanied individuals with high UACR quartiles and that TC did not differ between subgroups (Table 2). We then hypothesized that in this population, obesity did not have a direct impact on the state of health of the body, which could be a specific manifestation of being in an early compensatory phase influenced by age or hormonal changes during puberty. Ciardullo S et al.40 found that metabolic syndrome was associated with renal damage in a cross-sectional study, whereas obesity alone was not associated with any renal outcome. Another study41 clarified that an elevated triglyceride-glucose index was independently associated with albuminuria. The shift from obesity to metabolic disease is a quantitative to qualitative change; therefore, the renal health risk in overweight/obese children and adolescents should not be taken lightly, and it is important to monitor their indices regarding blood pressure, lipids, and glucose over a long period, which not only allows for timely intervention in the development of renal disease but may also lead to new clinical findings from it. Of course, long-term, large-sample, global studies will also be needed to focus on the thresholds of various body measurements that cause UACR abnormalities in children and adolescents so that early intervention and timely treatment can be provided to this population to reduce the incidence of kidney disease.

Insulin resistance plays an important role in obesity-related chronic kidney disease. Visceral fat has vigorous endocrine activity and can secret various cytokines, such as pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α and IL-6) and fatty acids, which can directly interfere with insulin’s signalling pathway, thereby exacerbating insulin resistance. Excessive accumulation of fatty acids also causes liver disease such as fatty liver, which further aggravates insulin resistance24. The progression of kidney disease is often accompanied by metabolic disorders, of which insulin resistance is one of the key markers. Obesity promotes insulin resistance through multiple pathways, which in turn affects renal function and can lead to the development of diabetic nephropathy, exacerbating tubulointerstitial fibrosis and altering renal perfusion42. Common treatments include weight loss and pharmacologic therapy (e.g., metformin, GLP-1 receptor agonists, SGLT-2 inhibitors, etc.). A randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled trial43 of Canagliflozin in nondiabetic obese albuminuric patients demonstrated that the drug was well tolerated, with a significant transient decrease in glomerular filtration rate but not a significant decrease in UACR. Therefore, future studies need to continue exploring the deeper relationship between insulin resistance and renal injury and seeking new therapeutic targets for more effective clinical interventions. It has been found that urinary netrin-1, alpha-GST, pi-GST, and calreticulin may be better indicators for detecting early tubular injury, independent of the severity of obesity44. This would be a positive contribution to kidney health monitoring in obese children.

In the present study, nutritional status and physical activity level, as key lifestyle factors, may profoundly impact the relationship between UACR and overweight/obesity. Dietary structure directly affects the body’s metabolic state and may regulate glomerular and tubular function through multiple pathways. High energy intake, especially high-fat and high-sugar diets, has been widely demonstrated to be closely associated with obesity and its associated metabolic disorders, and these metabolic abnormalities may accelerate glomerular injury through the induction of insulin resistance, chronic low-grade inflammation, oxidative stress, which may, in turn, affect UACR levels45,46. In addition, the role of protein intake is more complex. Previous studies47 have shown that a high-protein diet may increase the glomerular filtration load, leading to glomerular hyperfiltration and promoting proteinuria. Moderate protein intake plays an important role in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis and muscle mass in the body, which may provide some protection against renal function. Therefore, in the child and adolescent population, dietary quality not only influences the development of obesity but may also regulate UACR through multiple metabolic pathways, suggesting that future studies should further explore the long-term effects of specific nutrient intake patterns on UACR and renal function.

On the other hand, physical activity plays a central role in weight management, metabolic regulation, and maintenance of kidney health. Regular moderate to high-intensity exercise has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity, reduce systemic levels of inflammation, and optimize hemodynamic status, potentially reducing urinary albumin excretion by reducing the stress of glomerular hyperperfusion and hyperfiltration48. In addition, physical inactivity not only increases the risk of obesity but may also exacerbate metabolic abnormalities such as insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, which may further deteriorate renal function. In the present study, although the L-shaped nonlinear relationship between UACR and overweight/obesity remained significant after adjusting for the level of physical activity, attention must be paid to the potential moderating effect of physical activity in this association. Future studies should further clarify the effects of different types, frequencies, and intensities of exercise patterns on UACR to explore optimal exercise intervention programs to establish lifestyle improvement-based renal protection strategies in children and adolescent populations.

The present study found that gender and age may play an important role in UACR levels and their relationship with overweight/obesity. Sex differences may arise from differences in physiologic characteristics, hormone levels, and fat distribution patterns. Estrogen has been shown to have anti-inflammatory and renoprotective effects, which may partially explain the lower UACR levels in women49. In contrast, men may be more susceptible to obesity-associated inflammation and oxidative stress due to the higher accumulation of visceral fat, which may lead to changes in UACR. In addition, hormonal fluctuations during puberty may further modulate glomerular filtration and urinary protein excretion patterns49. Age factors, on the other hand, may influence UACR levels through changes in renal development and metabolic status. Higher glomerular filtration rate in childhood, short-term insulin resistance due to rapid pubertal growth, and changes in renal hemodynamics may influence the dynamics of UACR. The age subgroup analyses in the present study showed differences in the absolute levels of UACR between different age groups. However, the L-shaped nonlinear relationship between UACR and overweight/obesity remained consistent across all age groups, suggesting that despite the influence of age on the absolute value of UACR, its moderating effect on the association between the two is relatively limited. However, previous studies have shown that obesity in adulthood may lead to an elevated UACR, and the negative association observed in the present study population suggests that UACR is modulated by other physiological factors during the pubertal stage, such as hormone levels and glomerular adaptive changes. Therefore, future studies should further refine the age- and sex-stratified analyses by combining longitudinal data in order to explore the long-term effects of hormone levels, insulin resistance, and renal hemodynamic changes on UACR during puberty, and to explore the underlying mechanisms by combining biomarkers in order to optimize the strategies for obesity management and renal health monitoring in children and adolescents.

In the present study, we also found that HDL-C levels differed significantly between UACR quartiles, and individuals with higher UACR tended to have higher HDL-C levels, suggesting that HDL-C may play an important role in renal function and lipid metabolism. As an antiatherogenic lipoprotein, HDL-C has important physiological functions in lipid metabolism and cardiovascular protection but may also affect the glomerular barrier through anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and endothelial functions50. Previous studies in adults have generally reported a negative correlation between HDL-C levels and UACR, i.e., lower HDL-C levels may be associated with an increased incidence of microalbuminuria, suggesting that HDL-C may play a protective role in the kidneys by reducing glomerular inflammation, inhibiting lipid deposition and improving hemodynamics. However, the relationship between HDL-C and UACR is relatively complex in pediatric and adolescent populations, and some studies have found a weak correlation between the two or even a positive correlation observed in some studies. The data from the present study support this view. They may reflect a metabolic state specific to adolescent individuals or suggest differences in the physiologic function of HDL-C at different ages. One possible explanation is that the lipid metabolic profile of children and adolescents differs from that of adults and that changes in hormone levels during puberty may affect the distribution and function of HDL isoforms. In addition, elevated HDL-C may represent a compensatory response of the body to inflammation or metabolic abnormalities, and HDL-C levels may change dynamically during the progression of metabolic disorders. It has been shown that specific individuals with metabolic syndrome may have a reduced proportion of functional HDL despite high HDL-C levels, leaving them with impaired anti-inflammatory and antioxidant function, affecting kidney health. Thus, elevated HDL-C levels in the pediatric and adolescent population may not necessarily imply a healthier lipid metabolic state but may reflect metabolic stress. It is noteworthy that the L-shaped nonlinear relationship between UACR and overweight/obesity remained significant after adjusting for HDL-C levels in this study, suggesting that although HDL-C may play a role in the regulation of renal function, it is not the dominant factor in determining the relationship between UACR and obesity. Nevertheless, this finding still emphasizes the importance of HDL-C as a potential biomarker of renal function. Future studies should further explore the specific roles of different HDL isoforms and their functions in children and adolescent populations to clarify their mechanisms in renal protection or injury. In addition, future longitudinal studies should also focus on the dynamic pattern of changes in HDL-C and UACR to resolve its role in obesity-related renal damage and optimize renal health management strategies in children and adolescents.

The L-shaped nonlinear negative correlation between UACR and overweight/obesity may be related to several factors. First, renal tubular function in children and adolescent populations may show more excellent adaptation during growth and development, and the tubular reabsorption of urinary proteins may be more active than that in adults, especially during the pubertal stage. Modulating the insulin signaling pathway and the growth hormone axis may further augment this compensatory mechanism, reducing the level of UACR. Second, it has been found that obese individuals may have relatively high blood volume and glomerular filtration rate in the early stages, which may reduce urinary albumin excretion in the short term, resulting in a decrease in UACR51. However, as obesity progresses, prolonged metabolic stress may lead to glomerular injury and increased proteinuria. Hence, the relationship between UACR and overweight/obesity plateaus or even has no significant correlation when UACR is above a specific threshold (log(UACR) > 1.435 mg/g), which may reflect a tipping point for metabolic homeostasis.

Compared with previous studies, an important finding of the present study is that individuals with higher UACR tended to be accompanied by higher HDL-C levels. In contrast, TC levels did not change significantly among different UACR quartiles. This may reflect an adaptive adjustment of lipid metabolism in individuals with obese children and adolescents, i.e., lipid metabolism has not yet entered a stage of severe imbalance despite an elevated body mass index, and HDL-C may maintain anti-inflammatory and antioxidant functions to a certain extent, which in turn affects the pattern of changes in UACR. This phenomenon is similar to the characteristics of specific individuals with pre-metabolic syndrome, i.e., despite being overweight, HDL-C levels did not show a significant decrease because they had not yet developed into a state of severe metabolic imbalance, suggesting that the UACR may be associated with compensatory adaptations to obesity at an early stage rather than simply reflecting renal damage.

The negative correlation between UACR and overweight/obesity remained stable across age and sex subgroups, but puberty may be a key regulatory stage in this relationship. Previous studies have shown that hormonal changes during puberty affect renal hemodynamics and filtration function and may also further modulate UACR levels by affecting insulin sensitivity and fat distribution patterns. No significant gender differences were found in the present study. However, considering the role of estrogen in renal protection, future studies should further explore the specific mechanisms of puberty in UACR changes by combining metabolic indicators such as sex hormone levels and insulin resistance index. In addition, the results of this study suggest that changes in UACR may be one of the early signals of obesity-induced renal injury rather than simply reflecting renal function impairment, so future studies should focus on the dynamic changes in UACR and evaluate its value in predicting the risk of obesity-related renal disease in combination with longitudinal data.

The above findings have important clinical implications for the management of renal health in obese children and adolescents. Unlike the positive correlation pattern commonly reported in adult studies, based on the results of the present study, we hypothesize that there may be compensatory mechanisms for obesity in the early stage of renal impairment, such as enhanced tubular reabsorption, changes in hormone levels during puberty and hemodynamic adaptations, which cause the UACR to decrease inversely within a specific range. However, as the UACR approaches the inflection point, compensatory capacity may become progressively imbalanced, suggesting that elevated BMI may increase the risk of renal damage above a certain threshold. Therefore, in clinical practice, relying on UACR alone to screen for obesity-related renal damage may have limitations and needs to be combined with longitudinal monitoring to focus on trend changes in UACR with age to identify potential renal function risks. In addition, this study found that individuals with higher UACR were accompanied by higher HDL-C levels, suggesting that adaptive adjustments in lipid metabolism may have some protective effects on renal function in the early stages of obesity. However, further studies are needed to determine whether this state is sustainable. Therefore, BMI management strategies should go beyond weight control alone to incorporate a combined assessment of UACR, insulin resistance index, lipids, and inflammatory markers to optimize individualized intervention protocols for obese children and adolescents. We will further explore the role of UACR in metabolic regulation during puberty and evaluate its clinical value in predicting the risk of obesity-associated nephropathy in conjunction with longitudinal data in the future in order to refine screening strategies and develop precise early interventions to reduce the incidence of obesity-associated renal disease.

This study utilized data from NHANES from 2011 to 2016 with a large and nationally representative sample size, which makes the findings broadly applicable and credible and can more accurately reflect the L-shaped negative correlation between overweight/obesity and UACR in the US population of children and adolescents aged 8 to 19 years, and discover the critical value of the correlation between UACR and overweight/obesity, which is of important clinical implications. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of overweight/obesity in a US pediatric population defined by BMI compared with the few previous related studies, which is informative for monitoring and preventing kidney disease. Of course, there are limitations to this study. As a cross-sectional study, this study could not establish a causal relationship between UACR and overweight/obesity. Although the findings suggest a significant association, it is impossible to determine whether UACR directly influences the development of overweight/obesity or vice versa. Therefore, future prospective cohort studies or randomized controlled trials will further clarify this relationship. Although the study considered multiple covariates, it was limited to the information in the database and failed to control factors such as diet and lifestyle adequately. These factors may have an impact on the relationship between overweight/obesity and UACR, so future studies should pay more attention to these potential confounders in order to fully assess their impact. The UACR data in this study were derived from random urine samples without 24-hour urine collection. Although random urine samples are more straightforward to collect and generalize, this method may not fully reflect an individual’s urinary albumin excretion level. Therefore, the reliability of the data could be improved in the future by using multiple urine sample measurements or more rigorous urine collection methods.

Conclusion

Data from this study revealed an L-shaped correlation between UACR and overweight/obesity in the US child and adolescent populations. A nonlinear association was found by building a smoothed fitting curve, and further threshold effect analysis observed log(UACR) 1.435 mg/g as the inflexion point. These findings close the important link between overweight/obesity and kidney disease, but the in-depth relationship and mechanisms between the two further clinical and basic research. Maintaining a moderate BMI in children and adolescents may help to reduce the incidence of albuminuria.

Data availability

These survey data are free and publicly available, and can be downloaded directly from the NHANES website (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm) by users and researchers worldwide.

Abbreviations

- UACR:

-

Urinary albumin creatinine ratio

- PIR:

-

Poverty-to-income ratio

- WBC:

-

Serum cotinine, white blood cell count

- EOS:

-

Eosinophil

- NEUT%:

-

Neutrophil percentage

- Hb:

-

Haemoglobin

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

References

Afshin, A. et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N. Engl. J. Med. 377(1), 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1614362 (2017).

Nikparast, A. et al. Dietary and lifestyle indices for hyperinsulinemia and odds of Mafld in overweight and obese children and adolescents. Sci. Rep. 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88969-3 (2025).

Ntimana, C. B., Seakamela, K. P., Mashaba, R. G. & Maimela, E. Determinants of central obesity in children and adolescents and associated complications in South Africa: A systematic review. Front. Public. Health 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1324855 (2024).

Yang, Y. X. et al. Hypertension-Related status and influencing factors among Chinese children and adolescents aged 6∼17 years: data from China nutrition and health surveillance (2015–2017). Nutrients 16(16). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162685 (2024).

Moriya, R. M., de Oliveira, C. E. C., Reiche, E. M. V., Passini, J. L. L. & Nunes, S. O. V. Association of adverse childhood experiences and overweight or obesity in adolescents: A systematic review and network analysis. Obes. Rev. 25(11). https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13809 (2024).

Viswanathan, G. & Upadhyay, A. Assessment of proteinuria. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 18(4), 243–248. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2011.03.002 (2011).

Jensen, M. B., Viken, I., Hogh, F. & Jacobsen, K. K. Quantification of urinary albumin and-Creatinine: A comparison study of two analytical methods and their impact on albumin to creatinine ratio. Clin. Biochem. 108, 5–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2022.06.014 (2022).

Nakajima, H. et al. Activation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling pathway in renal proximal tubular cells by albumin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 15(2), 276–285. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.Asn.0000109672.83594.02 (2004).

Anders, H. J. & Muruve, D. A. The inflammasomes in kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 22(6), 1007–1018. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2010080798 (2011).

Sinico, R. A., Mezzina, N., Trezzi, B., Ghiggeri, G. M. & Radice, A. Immunology of membranous nephropathy: from animal models to humans. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 183(2), 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/cei.12729 (2016).

Li, H., Ren, Y. J., Duan, Y. G., Li, P. & Bian, Y. F. Association of the longitudinal trajectory of urinary albumin/creatinine ratio in diabetic patients with adverse cardiac event risk: A retrospective cohort study. Front. Endocrinol. 15 https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1355149 (2024).

Hosaka, M. et al. Effect of amlodipine, efonidipine, and Trichlormethiazide on home blood pressure and Upper-Normal microalbuminuria assessed by casual spot urine test in essential hypertensive patients. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 40(5), 468–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641963.2017.1403617 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. The association between a body shape index and elevated urinary Albumin-Creatinine ratio in Chinese community adults. Front. Endocrinol. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.955241 (2022).

Zhu, W., Dong, X. J., Pan, Q. R., Hu, Y. J. & Wang, G. The Association between Albuminuria and Thyroid Antibodies in Newly Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis and Euthyroidism. Bmc Endocr. Disorders. 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-020-00650-0 (2020).

Huang, R. L. & Chen, X. W. Increased spot urine Albumin-to-Creatinine ratio and stroke incidence: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 28(10). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.06.018 (2019).

Straznicky, N. E. et al. Exercise augments weight loss induced improvement in renal function in obese metabolic syndrome individuals. J. Hypertens. 29(3), 553–564. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283418875 (2011).

Bray, G. A. Beyond Bmi. Nutrients 15(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102254 (2023).

Betz, H. H. et al. Physical activity, Bmi, and blood pressure in Us youth: Nhanes 2003–2006. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 30(3), 418–425. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.2017-0127 (2018).

Sun, J. Q., Han, J., Jiang, X. F., Ying, Y. L. & Li, S. H. Association between breastfeeding duration and Bmi, 2009–2018: A Population-Based study. Front. Nutr. 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1463089 (2024).

Zhu, H. Y. et al. Urinary Albumin-to-Creatinine ratio as an independent predictor of Long-Term mortality in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease patients: A propensity Score-Matched study Uacr and Long-Term mortality in Ascvd. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpc.2024.100920 (2025).

Dai, H., Liu, L. & Xu, W. W. Association of Albumin-to-Creatinine ratio with diabetic retinopathy among Us adults (Nhanes 2009–2016). Endocrinol. Diabetes Metabolism. 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/edm2.70029 (2025).

Garofalo, C. et al. A systematic review and Meta-Analysis suggests obesity predicts onset of chronic kidney disease in the general population. Kidney Int. 91(5), 1224–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2016.12.013 (2017).

Friedman, A. N. et al. Obstacles and opportunities in managing coexisting obesity and Ckd: report of a scientific workshop cosponsored by the National kidney foundation and the obesity society. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 80(6), 783–793. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.06.007 (2022).

Li, Q. et al. Radish red attenuates chronic kidney disease in obese mice through repressing oxidative stress and ferroptosis via Nrf2 signaling improvement. Int. Immunopharmacol. 143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113385 (2024).

Stasi, A. et al. Obesity-Related chronic kidney disease: principal mechanisms and new approaches in nutritional management. Front. Nutr. 9 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.925619 (2022).

García-Carro, C. et al. A nephrologist perspective on obesity: from kidney injury to clinical management. Front. Med. 8 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.655871 (2021).

Atkins, R. C. et al. Prevalence of albuminuria in Australia: the ausdiab kidney study. Kidney Int. 66, S22–S4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.09206.x (2004).

Rosenstock, J. L., Pommier, M., Stoffels, G., Patel, S. & Michelis, M. F. Prevalence of proteinuria and albuminuria in an obese population and associated risk factors. Front. Med. 5 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2018.00122 (2018).

Kramer, H. et al. Obesity and albuminuria among adults with type 2 diabetes the look ahead (Action for health in diabetes) study. Diabetes Care. 32(5), 851–853. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc08-2059 (2009).

Lurbe, E. et al. Prevalence and factors related to urinary albumin excretion in obese youths. J. Hypertens. 31(11), 2230–2236. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e328364bcbf (2013).

Burgert, T. S. et al. Microalbuminuria in pediatric obesity: prevalence and relation to other cardiovascular risk factors. Int. J. Obes. 30(2), 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0803136 (2006).

Csernus, K., Lanyi, E., Erhardt, E. & Molnar, D. Effect of childhood obesity and obesity-Related cardiovascular risk factors on glomerular and tubular protein excretion. Eur. J. Pediatrics 164(1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-004-1546-2 (2005).

Larkins, N., Teixeira-Pinto, A. & Craig, J. The Population-Based prevalence of albuminuria in children. Pediatr. Nephrol. 32(12), 2303–2309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-017-3764-7 (2017).

Gracchi, V., van den Belt, S. M., Corpeleijn, E., Heerspink, H. J. L. & Verkade, H. J. Albuminuria and markers for cardiovascular risk in 12-Year-Olds from the general Dutch population: A Cross-Sectional study. Eur. J. Pediatrics. 182(11), 4921–4929. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-05152-4 (2023).

Qin, X. K., Wei, J. H., Chen, J., Lei, F. Y. & Qin, Y. H. Non-Linear relationship between body roundness index and albuminuria among children and adolescents aged 8–19 years: A cross-sectional study. Plos One 19(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299509 (2024).

Salman, D. et al. Evaluation of renal function in obese children and adolescents using serum Cystatin C levels, estimated glomerular filtration rate formulae and proteinuria: which is most useful?? J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 11(1), 46–54. https://doi.org/10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2018.2018.0046 (2019).

Nguyen, S., McCulloch, C., Brakeman, P., Portale, A. & Hsu, C. Y. Being overweight modifies the association between cardiovascular risk factors and microalbuminuria in adolescents. Pediatrics 121(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-3594 (2008).

Wu, D. Q. et al. Age- and Gender-Specific reference values for urine albumin/creatinine ratio in children of Southwest China. Clin. Chim. Acta 431, 239–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2014.02.015 (2014).

Hirschler, V., Molinari, C., Maccallini, G. & Aranda, C. Is albuminuria associated with obesity in school children?? Pediatr. Diabetes. 11(5), 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00599.x (2010).

Ciardullo, S., Ballabeni, C., Trevisan, R. & Perseghin, G. Metabolic syndrome, and not obesity, is associated with chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 52(8), 666–672. https://doi.org/10.1159/000518111 (2021).

Wang, Z. X. et al. The relationship between Triglyceride-Glucose index and albuminuria in united States adults. Front. Endocrinol. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1215055 (2023).

Liu, Y. F., Zhao, D., Chai, S. B. & Zhang, X. M. Association of visceral adipose tissue with albuminuria and interaction between visceral adiposity and diabetes on albuminuria. Acta Diabetol. 61(7), 909–916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-024-02271-8 (2024).

Bays, H. E., Weinstein, R., Law, G. & Canovatchel, W. Canagliflozin: effects in overweight and obese subjects without diabetes mellitus. Obesity 22(4), 1042–1049. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20663 (2014).

Medynska, A., Chrzanowska, J., Zubkiewicz-Kucharska, A. & Zwolinska, D. New markers of early kidney damage in children and adolescents with simple obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25(19). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms251910769 (2024).

la Fleur, S. E., Luijendijk, M. C. M., van der Zwaal, E. M., Brans, M. A. D. & Adan, R. A. H. The snacking rat as model of human obesity: Effects of a Free-Choice High-Fat High-Sugar diet on meal patterns. Int. J. Obes. 38(5), 643–649. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.159 (2014).

Chiavaroli, L. et al. Original important food sources of Fructose-Containing sugars and adiposity: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis of controlled feeding trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 117(4), 741–765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2023.01.023 (2023).

Friedman, A. N. et al. Comparative effects of low-carbohydrate high-protein versus low-fat diets on the kidney. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 7(7), 1103–1111. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.11741111 (2012).

Pinheiro-Mulder, A., Aguila, M. B., Bregman, R. & Mandarim-de-Lacerda, C. A. Exercise counters Diet-Induced obesity, proteinuria, and structural kidney alterations in rat. Pathol. Res. Pract. 206(3), 168–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2009.11.004 (2010).

Ayesh, H., Nasser, S. A., Ferdinand, K. C. & Leon, B. G. C. Sex-Specific factors influencing obesity in women: bridging the gap between science and clinical practice. Circul. Res. 136(6), 594–605. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.124.325535 (2025).

Kontush, A. & Chapman, M. J. Functionally defective high-density lipoprotein: A new therapeutic target at the crossroads of dyslipidemia, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Pharmacol. Rev. 58(3), 342–374. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.58.3.1 (2006).

Ali, M. M., Parveen, S., Williams, V., Dons, R. & Uwaifo, G. I. Cardiometabolic comorbidities and complications of obesity and chronic kidney disease (Ckd). J. Clin. Translational Endocrinol. 36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcte.2024.100341 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all of the participants and staff involved in NHANES for their valuable contributions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Z.J. designed the study and drafted the manuscript. Z.S.M. and C.X.R. performed the data retrieval and downloading. C.Z.J., L.F., and W.Y.Y. completed the statistical analysis and image processing. H.C.C. and Y.B. reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, Z., Chen, X., Zhai, S. et al. A cross-sectional study investigating the L-shaped relationship between urinary albumin creatinine ratio and overweight/obesity in children and adolescents. Sci Rep 15, 14588 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99594-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99594-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

S-shaped association between hs-CRP/HDL-C index and overweight/obesity in children and adolescents: a population-based study

European Journal of Medical Research (2025)