Abstract

This meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) when compared to metformin and placebo in the management of body weight, glucose homeostasis and hormone levels in women polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). A systematic search of “PubMed”, “EMBASE”, “Cochrane Library”, “Web of Science” and “Google Scholar” was conducted up to October 2024 for randomized controlled trials involving adult women with PCOS treated with GLP-1RAs compared to metformin or placebo. The primary outcomes were changes in body mass index (BMI), body weight, waist circumference (WC), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) and abdominal girth (AG). Secondary outcomes included glucose homeostasis (fasting glucose, fasting insulin, OGTT results and HOMA-IR), hormone levels (DHEAS, SHBG, total and free testosterone and FAI), lipid profiles (total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and triglycerides) and safety. GLP-1RAs significantly reduced BMI, body weight, WC, WHR and AG (P < 0.0001 in all cases). For glucose homeostasis, GLP-1RAs significantly reduced fasting insulin, glucose level at 2 h after OGTT, and HOMA-IR. There was also a reduction in HDL. All the other parameters measured were unchanged. In addition, GLP-1RAs increased nausea (P = 0.02), vomiting (0.04) and dizziness (0.03). GLP-1RAs effectively reduced body weight, BMI and insulin resistance in patients with PCOS, although they were accompanied by nausea, vomiting and dizziness. Further studies are needed to explore their long-term effects on glucose homeostasis and lipid profiles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common reproductive endocrine disorder among women of reproductive age. Its clinical manifestations are highly heterogeneous, primarily characterized by infrequent or absent ovulation, elevated androgen levels and polycystic ovarian changes1,2. It is often associated with insulin resistance (IR), obesity, dyslipidemia and other metabolic disturbances3. In long-term sufferers of this condition, it can lead to type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cardiovascular disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and endometrial cancer4. These issues affect women throughout their lives, impacting approximately 5–10% of women of reproductive age5.

The exact cause of PCOS remains unclear, but it is generally reported that IR plays a crucial role in its onset and progression6. Studies have shown that patients with PCOS exhibit selective IR, primarily characterized by abnormalities in the insulin signaling pathways, often associated with altered metabolic parameters7. Further research has revealed varying degrees of IR in different tissues of PCOS patients, including adipose tissues, fibroblasts and skeletal muscle cells8,9. This suggests that, in addition to systemic IR, PCOS may involve localized IR in the ovaries. There is often a reduction in insulin receptor phosphorylation in PCOS ovarian tissues, which can lead to impaired insulin signaling and decreased glucose uptake in the granulosa cells.

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway is central to the action of insulin and Akt is a downstream molecule that regulates cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation and metabolism. Reduced phosphorylation of the PI3K/Akt pathway is a hallmark of IR in PCOS patients10,11,12. The transcription factor, FOXO1, is one of the regulators of this pathway, and it is involved in processes such as the cell cycle and apoptosis. In PCOS, FOXO1 promotes follicle atresia and granulosa cell apoptosis by activation of pro-apoptotic proteins such as p27Kip1 and Bim, thereby contributing to the cystic changes in the ovaries13,14. Additionally, compensatory hyperinsulinemia caused by IR may lead to excessive activation of IGF-1 and it can directly stimulate theca cells to produce androgens, exacerbating hyperandrogenism and inhibiting follicular development and ovulation, thus worsening the symptoms associated with PCOS15,16. Overall, localized IR and hyperinsulinemia in the ovaries are the central mechanisms in the pathogenesis of PCOS, leading to ovarian dysfunction, impaired folliculogenesis and hyperandrogenism, which manifest as clinical symptoms of the syndrome.

Currently, the treatment for PCOS primarily focuses on addressing issues related to hyperandrogenism and anovulation, with medications aimed at improving IR. Since the long-term use of estrogen-progestin-based ovulation-inducing drugs and androgen-lowering treatments carry a risk of endometrial cancer, and since weight loss and the effects on IR are often minimal, clinical approaches are now seeking therapies that can simultaneously address both reproductive hormone imbalances and disturbances in glucose metabolism17. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), such as exenatide, and GLP-1 analogs, such as liraglutide, which are primarily used for the treatment of T2DM, have been studied in PCOS. Reduced levels of GLP-1 in PCOS patients suggest that it may be involved in the pathogenesis and progression of the condition, and that it is potentially linked to obesity and IR. For PCOS patients with obesity and infertility, a combined treatment with metformin and liraglutide has been shown to effectively reduce body weight, improved glucose metabolism and relieved IR18. However, while individual studies have shown promising results, the overall efficacy and safety of GLP-1RA therapy in women with PCOS require further comprehensive evaluation.

This meta-analysis systematically assessed the impact of GLP-1RA therapy on anthropometric outcomes and key metabolic parameters in women with PCOS. Specifically, the analysis will evaluate changes in fasting glucose levels, body mass index (BMI), body weight, waist circumference (WC), insulin sensitivity as measured by the homeostatic model assessment of IR (HOMA-IR) and other relevant hormonal and metabolic markers. In addition, we also evaluated the safety of the combined treatment of metformin and GLP-1RAs. By using the data from multiple studies, in this analysis we attempted to clarify the role of IR in the pathogenesis of PCOS and assess the efficacy of GLP-1RAs in improving both the reproductive and metabolic outcomes for patients with PCOS.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This meta-analysis adhered to the PRISMA guidelines. A comprehensive literature search was conducted across multiple databases, including “PubMed”, “EMBASE”, “Cochrane Library”, “Google scholar” and “Web of Science” from their inception until October 2024. The search strategy focused on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing treatment with a combination of GLP-1RAs and metformin or placebo. Keywords and medical subject headings (MeSH) terms used in the search included: “Polycystic ovary syndrome”, “PCOS”, “GLP-1 receptor agonist”, “GLP-1RA”, “Semaglutide”, “Liraglutide”, “Exenatide” and “Metformin”. The search strategy was customized for each database. Additionally, reference lists of identified studies were manually checked for additional relevant articles. The studies were selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, and those reporting relevant anthropometric and metabolic outcomes were included in the final analysis19.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible if they met the following criteria: (1) The participants were adult women aged 18–45 years diagnosed with PCOS. (2) The intervention group received GLP-1RAs, while the control group received either metformin or placebo. (3) The study reported outcomes related to anthropometric measures (BMI, body weight, WC, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), abdominal girth (AG)) and metabolic markers (fasting glucose, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), SHBG, total testosterone, free testosterone and cholesterol levels). The exclusion criteria were: (1) Studies with incomplete data for key outcomes. (2) Non-RCT studies. (3) Trials with a follow-up period of less than 12 weeks. Adherence to inclusion and exclusion criteria was assessed by two independent reviewers through detailed screening of the study characteristics, participant descriptions, and reported outcomes in the full texts.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers extracted the data from eligible studies using a standardized extraction protocol. The data extracted included study characteristics (first author, publication year, sample size and duration of follow-up), participant demographics (age and gender), intervention type (GLP-1RAs, metformin and placebo) and outcomes related to anthropometric and metabolic parameters. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by consensus.

Outcomes assessment

The primary outcomes included reductions in BMI, body weight, WC, WHR and AG. Secondary outcomes included fasting glucose, fasting insulin, glucose level at 2 h after an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), insulin at 2 h after OGTT, HOMA-IR, DHEAS, SHBG, total testosterone, free testosterone, and lipid levels (total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and triglycerides (TG)).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the review manager (RevMan) software package version 5.0. The mean differences (MDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for continuous outcomes. A random effects model was used for analyses with high heterogeneity (I2 > 50%), while a fixed effects model was applied when the heterogeneity of the data was low (I2 < 50%). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic and Chi-square test, and a P-value of less than 0.10 was considered significant for heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses were conducted to examine the effects of GLP-1RAs compared to metformin or placebo. Subgroup comparisons were made based on the control group intervention for each of the anthropometric and metabolic parameter measured. Funnel plots were generated to assess publication bias for key outcomes.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. This evaluation considered random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting. Studies with a high risk of bias were noted, and their impact on overall findings was considered during the sensitivity analysis employed.

Results

Study screening

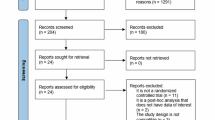

A flow diagram of the meta-analysis conducted in this study is shown in Fig. 1. 524 studies were included for initial analysis and after removing duplicated reports, 189 remained. After screening the titles and abstracts, the full text of 25 articles were collected and 13 RCTs that met the exclusion and inclusion criteria were used for subsequent meta-analysis.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the individual studies are presented in Table 1. The meta-analysis included a total of 397 and 330 individuals who received the invention of GLP-1RAs and metformin, respectively, as well as 68 individuals who received a placebo. With respect to GLP-1RAs, 23, 87 and 308 patients respectively received semaglutide, liraglutide and exenatide.

Quality assessment

Six studies were classified as having a “high risk” of performance bias and one was categorized as having a “unclear risk” of performance bias. Four, 1 and 6 studies were categorized as having “high risk”, “medium risk” and “unclear risk” of detection bias, respectively. Four studies were categorized as having an “unclear risk” of selection bias. One study was categorized as having an “unclear risk” of attrition bias Three studies were classified as having an “unclear risk” of other forms of biases. A visual representation of the eligibility of the quality of the clinical studies included is shown in Fig. 2.

Changes in anthropometrics

For anthropometric measurements, we compared the results of reduction in BMI, body weight, BMI, WC, WHR and AG. In terms of reduction in BMI, 11 studies (with 349 and 310 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included in the analysis. Due to the heterogeneity observed in the included studies (I2 = 74%, P < 0.0001), we used a random-effects model (Fig. 3A). GLP-1RA interventions was associated with a reduction in BMI when compared to either metformin or placebo (MD = −1.59; 95% CI −2.07 to −1.10; P < 0.0001; Fig. 3A).

For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group received either metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S1A, GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in BMI when compared to metformin (MD = −1.11; 95% CI −1.84 to −0.38; P = 0.003) or placebo (MD = −1.59; 95% CI −2.07 to −1.10; P < 0.0001).

In terms of reduction in body weight, 10 studies (with 339 and 301 participants from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. Due to the presence of heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 87%, P < 0.0001), a random-effects model was used (Fig. 3B). GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in body weight when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = −3.57; 95% CI −5.15 to -1.99; P < 0.0001; Fig. 3A). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on if the patients from the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S1B, GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in body weight when compared to metformin (MD = −1.81; 95% CI −2.60 to −1.01; P < 0.0001) or placebo (MD = −5.44; 95% CI −5.90 to −4.99; P < 0.0001).

In terms of reduction in WC, 8 studies (with 232 and 189 participants from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. No heterogeneity was presented in the included studies, (I2 = 0%, P = 0.47), and therefore the fixed effects model was used (Fig. 3C). GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in WC when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = −4.97; 95% CI −5.56 to −4.37; P < 0.0001; Fig. 3C). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S1C, GLP-1RAs intervention was associated with a reduction in body weight when compared to metformin (MD = −3.82; 95% CI −5.33 to −2.31; P < 0.0001) or placebo (MD = −5.17; 95% CI -5.82 to -4.53; P < 0.0001).

With respect to the reduction in WHR, 4 studies (with 225 and 210 participants from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. No heterogeneity was presented in the included studies, (I2 = 19%, P = 0.30), and so the fixed effects model was used (Fig. 3D). GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in WHR when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = −0.03; 95% CI −0.03 to −0.03; P < 0.0001; Fig. 3D). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S1D, GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in WHR when compared to metformin (MD = −0.03; 95% CI −0.04 to −0.02; P < 0.0001) or placebo (MD = −0.03; 95% CI −0.03 to −0.03; P < 0.0001).

In terms of reduction in AG, 3 studies (with 117 and 121 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. No heterogeneity was presented in the included studies, (I2 = 0%, P = 0.65), and so the fixed effects model was used (Fig. 3E). GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in AG when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = −2.05; 95% CI −2.93 to −1.16; P < 0.0001; Fig. 3E). Funnel plots of the reductions in BMI, body weight, WC, WHR and AG of the patients indicated no publication bias (Fig. S2).

Changes in glucose homeostasis

For glucose homeostasis, we compared the results for the reduction in fasting glucose and insulin levels, their levels at 2 h after OGTT and HOMA-IR. In terms of reduction in fasting glucose levels, 6 studies (with 252 and 235 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. Due to the heterogeneity presented in the included studies, (I2 = 95%, P < 0.0001), we used the random effects model (Fig. 4A). GLP-1RA intervention was not associated with a reduction in fasting glucose level when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = −0.12; 95% CI −0.28 to 0.04; P = 0.14; Fig. 4A). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S3A, GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in fasting glucose level when compared to placebo (MD = −0.29; 95% CI −0.33 to −0.25; P < 0.0001), but not metformin (MD = −0.02; 95% CI −0.07 to 0.04; P = 0.57).

In terms of reduction in glucose levels at 2 h after OGTT, 5 studies (with 205 and 213 subjects the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. Due to the heterogeneity presented in the included studies, (I2 = 86%, P < 0.0001), we used the random effects model (Fig. 4B). GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in glucose levels at 2 h after OGTT when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = −0.54; 95% CI −1.01 to 0.07; P = 0.02; Fig. 4B). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S3B, GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in glucose levels at 2 h after OGTT when compared to placebo (MD = −2.14; 95% CI −3.33 to −0.95; P = 0.0004), but not metformin (MD = −0.34; 95% CI −0.76 to 0.09; P = 0.12).

In terms of reduction in fasting insulin levels, 5 studies (with 208 and 212 subjects from the experimental and controls groups, respectively) were included for analysis. Due to the heterogeneity presented in the included studies, (I2 = 78%, P = 0.001), we used the random effects model (Fig. 4C). GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in fasting insulin levels when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = −1.40; 95% CI −2.65 to −0.15; P = 0.03; Fig. 4C). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group had received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S3C, GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in fasting insulin when compared to those given metformin (MD = −1.43; 95% CI −2.75 to −0.11; P = 0.03), but not placebo (MD = −0.64; 95% CI −6.62 to 5.34; P = 0.83).

In terms of reduction in insulin levels at 2 h after OGTT, 5 studies (with 194 and 199 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. Due to the heterogeneity presented in the included studies, (I2 = 82%, P = 0.0008), we used the random effects model (Fig. 4D). GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in insulin levels at h after OGTT when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = −27.88; 95% CI −38.58 to −17.17; P < 0.0001; Fig. 4D). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group had received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S3D, GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in insulin levels at 2 h after OGTT when compared to metformin (MD = −22.18; 95% CI −29.57 to −14.79; P < 0.00001) or placebo (MD = −51.72; 95% CI −69.84 to −33.60; P < 0.00001).

In terms of reduction in HOMA-IR, 10 studies (with 338 and 296 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. Due to the heterogeneity presented in the included studies, (I2 = 91%, P < 0.00001), we used the random effects model (Fig. 4E). GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in HOMA-IR when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = −0.58; 95% CI −0.98 to −0.19; P = 0.004; Fig. 4E). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S3E, GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in HOMA-IR when compared to metformin (MD = −0.73; 95% CI −1.07 to −0.38; P < 0.0001) but not placebo (MD = −0.40; 95% CI −0.98 to −0.19; P = 0.26). Funnel plots of reduction in the fasting glucose and insulin levels as well as the patients’ levels at 2 h after OGTT, and their HOMA-IR indicated no publication bias (Fig. S4).

Changes in hormones

In terms of the reduction in DHEAS, 6 studies (with 128 and 110 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included in the analysis. Due to the presence of heterogeneity in the included studies (I2 = 96%, P < 0.00001), the random effects model was used (Fig. 5A). GLP-1 RA intervention was not associated with changes in DHEAS levels when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = −12.84; 95% CI −31.99 to 7.03; P = 0.21; Fig. 5A). For subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S5A, GLP-1 RA intervention was associated with a reduction in DHEAS levels when compared to placebo (MD = −18.20; 95% CI −23.13 to −13.23; P < 0.0001), but not when compared to those given metformin (MD = −10.83; 95% CI −38.87 to 17.22; P = 0.45).

In terms of the reduction in SHBG, 5 studies (with 151 and 153 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included in the analysis. No heterogeneity was present in the included studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.87), and so a fixed effects model was used (Fig. 5B). GLP-1 RA intervention was not associated with changes in SHBG levels when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = 0.96; 95% CI −1.05 to 2.97; P = 0.35; Fig. 5B).

In terms of the reduction in total testosterone, 9 studies (with 264 and 223 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included in the analysis. Due to the presence of heterogeneity in the included studies (I2 = 74%, P = 0.0002), the random effects model was used (Fig. 5C). GLP-1 RA intervention was not associated with changes in total testosterone when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = −0.05; 95% CI −0.20 to 0.11; P = 0.53; Fig. 5C). For subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S5B, GLP-1 RA intervention was associated with a reduction in total testosterone levels when compared to those given placebo (MD = −0.22; 95% CI −0.27 to −0.17; P < 0.0001), but not to those given metformin (MD = 0.13; 95% CI −0.16 to 0.42; P = 0.37).

In terms of the reduction in levels of free testosterone, 3 studies (with 39 and 41 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included in the analysis. Due to the heterogeneity in the included studies (I2 = 83%, P = 0.003), the random effects model was used (Fig. 5D). GLP-1 RA intervention was not associated with changes in free testosterone when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = 0.53; 95% CI −1.39 to 2.44; P = 0.59; Fig. 5D).

In terms of the reduction in FAI, 6 studies (with 195 and176 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included in the analysis. Due to the presence of heterogeneity in the included studies (I2 = 80%, P = 0.0001), the random effects model was used (Fig. 5E). GLP-1 RA intervention was not associated with changes in FAI when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = −1.72; 95% CI −1.94 to −1.50; P = 0.54; Fig. 5E). For subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S5E, GLP-1 RA intervention was associated with a reduction in FAI when compared to those given placebo (MD = −0.48; 95% CI −1.98 to −1.50; P < 0.0001), but not to those given metformin (MD = 0.26; 95% CI −2.08 to 2.61; P = 0.83). Funnels plot of the reduction in DHEAS, SHBG, total testosterone, free testosterone and FAI levels indicated no publication bias (Fig. S6).

Changes in total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and TG

In terms of reduction in total cholesterol, 10 studies (with 335 and 237 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. No heterogeneity was presented in the included studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.56), and we used the fixed effects model (Fig. 6A). GLP-1RA intervention was not associated with the changes in total cholesterol levels when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = −0.03; 95% CI −0.07 to 0.00; P = 0.06; Fig. 6A). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S7A, GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in total cholesterol when compared to placebo (MD = −0.04; 95% CI −0.08 to 0.00; P = 0.03) but not metformin (MD = 0.01; 95% CI −0.08 to 0.10; P = 0.83).

In terms of reduction in total HDL levels, 9 studies (with 325 and 288 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. No heterogeneity was presented in the included studies (I2 = 49%, P = 0.05), and we used the fixed effects model (Fig. 6B). GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in HDL when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = −0.02; 95% CI −0.04 to −0.01; P = 0.0001; Fig. 6B). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S7B, GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in HDL when compared to placebo (MD = −0.02; 95% CI −0.03 to −0.01; P = 0.001) but not metformin (MD = −0.04; 95% CI −0.07 to −0.01; P = 0.83).

In terms of reduction in total LDL levels, 9 studies (with 325 and 288 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. No heterogeneity was presented in the included studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.98), and we used the fixed effects model (Fig. 6C). GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in LDL when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = 0.01; 95% CI −0.03 to 0.05; P = 0.59; Fig. 6C). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S7C, GLP-1RA intervention was not associated with a reduction in LDL when compared to placebo (MD = 0.01; 95% CI −0.03 to −0.06; P = 0.001) or metformin (MD = 0.00; 95% CI −0.09 to 0.10; P = 0.92).

In terms of reduction in TG levels, 9 studies (with 324 and 283 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. Due to the heterogeneity presented in the included studies (I2 = 84%, P < 0.0001), we used the random effects model (Fig. 6D). GLP-1RA intervention was not associated with reduction in TG levels when compared to those given metformin or placebo (MD = −0.04; 95% CI −0.18 to 0.09; P = 0.50; Fig. 6D). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S7D, GLP-1RA intervention was associated with a reduction in TG when compared to placebo (MD = −0.20; 95% CI −0.18 to 0.09; P = 0.001) but not metformin (MD = 0.07; 95% CI −0.05 to 0.18; P = 0.26). Funnel plots of reduction in total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and TG indicated no publication bias (Fig. S8).

Safety assessment of GLP-1RAs

In terms of nausea, 11 studies (with 429 and 378 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. Due to the heterogeneity presented in the included studies (I2 = 52%, P = 0.02), we used the random effects model (Fig. 7A). GLP-1RA intervention was associated with higher nausea events when compared to the patients given metformin or placebo (OR = 3.07; 95% CI 1.56 to 6.03; P = 0.02; Fig. 7A). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S9A, GLP-1RA intervention was associated with increased nausea events when compared to placebo (OR = 5.33; 95% CI 1.53 to 18.63; P = 0.009) or metformin (OR = 2.58; 95% CI 1.15 to 5.76; P = 0.02).

In terms of vomiting, 7 studies (with 381 and 329 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. No heterogeneity was presented in the included studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.92), and we used the fixed effects model (Fig. 7B). GLP-1RA intervention was associated with higher vomiting events when compared to the patients given metformin or placebo (OR = 2.05; 95% CI 1.04 to 4.06; P = 0.04; Fig. 7B). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S9B, GLP-1RA intervention was not associated with increased vomiting events when compared to placebo (OR = 5.99; 95% CI 0.32 to 112.41; P = 0.23) or metformin (OR = 1.85; 95% CI 0.91 to 3.76; P = 0.09).

In terms of diarrhea, 9 studies (with 369 and 319 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. No heterogeneity was presented in the included studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.39), and we used the fixed effects model (Fig. 7C). GLP-1RA intervention was not associated with higher diarrhea events when compared to the patients given metformin or placebo (OR = 2.06; 95% CI 0.58 to 6.20; P = 0.20; Fig. 7C). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S9C, GLP-1RA intervention was not associated with increased diarrhea events when compared to placebo (OR = 13.08; 95% CI 2.06 to 82.80; P = 0.006) or metformin (OR = 1.37; 95% CI 0.40 to 4.67; P = 0.6).

In terms of constipation, 7 studies (with 331 and 279 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. No heterogeneity was presented in the included studies (I2 = 47%, P = 0.09), and we used the fixed effects model (Fig. 7D). GLP-1RA intervention was not associated with higher constipation events when compared to the patients given metformin or placebo (OR = 0.82; 95% CI 0.38 to 1.75; P = 0.60; Fig. 7D). For the subgroup analysis, the studies were classified based on whether the patients from the control group received metformin or placebo. As shown in Fig. S9D, GLP-1RA intervention was not associated with increased constipation events when compared to placebo (OR = 1.50; 95% CI 0.15 to 15.14; P = 0.73) or metformin (OR = 0.75; 95% CI 0.33 to 1.70; P = 0.49).

In terms of stomachache, 4 studies (with 229 subjects from each of the groups) were included for analysis. No heterogeneity was presented in the included studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.96), and we used the fixed effects model (Fig. 7D). GLP-1RA intervention was associated with lower stomachache events when compared to the patients given metformin or placebo (OR = 0.15; 95% CI 0.03 to 0.66; P = 0.01; Fig. 7E). In terms of bloating, 4 studies (with 229 subjects from each of the groups) were included for analysis. No heterogeneity was presented in the included studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.78), and we used the fixed effects model (Fig. 7F). GLP-1RA intervention was not associated with increased bloating events when compared to those given metformin or placebo (OR = 0.83; 95% CI 0.38–1.93; P = 0.67; Fig. 7F).

In terms of dizziness, 5 studies (with 276 and 252 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. No heterogeneity was presented in the included studies (I2 = 0%, P = 1.00), and we used the fixed effects model (Fig. 7G). GLP-1RA intervention was associated with increased dizziness when compared to those given metformin or placebo (OR = 5.58; 95% CI 1.23–25.22; P = 0.03; Fig. 7G).

In terms of fatigue, 1 study (with 20 subjects from each of the groups) were included for analysis. GLP-1RA intervention was not associated with fatigue when compared to those given metformin or placebo (OR = 0.18; 95% CI 0.01–4.01; P = 0.28; Fig. 7H). In terms of headache, 4 studies (with 92 and 68 subjects from the experimental and control groups, respectively) were included for analysis. Due to the heterogeneity presented in the included studies (I2 = 66%, P = 0.05), we used the random effects model (Fig. 7I). GLP-1RA intervention was not associated with increased dizziness events when compared to those given metformin or placebo (OR = 1.20; 95% CI 0.05–26.11; P = 0.91; Fig. 7I).

In terms of insomnia, 1 study (with 14 subjects from each of the groups) were included for analysis. GLP-1RA intervention was not associated with insomnia events when compared to the patients given metformin or placebo (OR = 3.22; 95% CI 0.12–86.09; P = 0.49; Fig. 7J). Funnel plots of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, stomachache, bloating, dizziness, fatigue, headache and insomnia indicated no publication bias (Fig. S10).

Discussion

The findings from our meta-analysis suggested that GLP-1RAs were effective in improving the anthropometric parameters such as BMI, body weight, WC, WHR and AG, particularly when compared to the patients given either metformin or placebo. The consistent reductions in BMI and body weight across various studies highlight the potential of GLP-1RAs in managing PCOS-related conditions, even in populations where metformin has traditionally been the first-line therapy. These results are clinically significant, as GLP-1RAs may offer an alternative approach for patients with PCOS. Additionally, the significant reductions in WC and WHR align with the body of evidence suggesting that the visceral fat is a major contributor to the metabolic complications associated with PCOS, and GLP-1RAs can help target this specifically.

However, it is important to note the heterogeneity observed in some of the outcomes, particularly for BMI and body weight reductions. The random-effects model used in the analysis addresses this variation to some extent, but the underlying causes of the heterogeneity warrant further investigation. Differences in the study populations, treatment duration and adherence to the different GLP-1RA regimens might have contributed to the variations observed. For example, the studies included in this meta-analysis involved varying the patient profiles, some of which included patients with more advanced metabolic disease conditions, potentially influencing the degree of weight reduction observed. Future studies could help clarify which specific subgroups of patients benefited the most from GLP-1RAs, whether this would be based on the baseline BMI, metabolic health or duration of therapy.

When examining the effects on glucose homeostasis, the results were mixed. While GLP-1RAs were associated with a reduction in glucose levels at 2 h post-OGTT and a modest decrease in fasting insulin and HOMA-IR, they were not significantly more effective than metformin in lowering fasting glucose levels. This could be attributed to the different mechanisms of action of these two drugs. Metformin primarily reduces hepatic glucose production, while GLP-1RAs enhance insulin secretion in response to meals20,21,22. Therefore, in patients where the fasting glucose is a more dominant feature of their hyperglycemia, metformin may be more appropriate, while GLP-1RAs could be better suited for those with postprandial hyperglycemia. The hormonal changes observed in our analysis further contribute to the therapeutic potential of GLP-1RAs, though the impact was less consistent compared to their effects on anthropometric measurements and glucose regulation. Specifically, no significant reductions in DHEAS, SHBG and testosterone levels were observed in the overall comparison with metformin or placebo. However, GLP-1RAs did show a favorable impact on these hormones when compared to placebo alone. This suggests that while GLP-1RAs may not outperform metformin in managing hormone levels, they are still beneficial in populations not already treated with metformin23,24,25,26. The heterogeneity observed in the hormonal analysis may stem from differences in baseline hormonal levels and other concurrent therapies used by the subjects in the included studies.

In terms of lipid profile management, GLP-1RAs showed modest effects. While total cholesterol and LDL levels were reduced, there was no significant differences in HDL and triglycerides. This highlights the limited role that GLP-1RAs play in lipid management, suggesting that additional lipid-lowering therapies may be necessary for comprehensive metabolic control27,28,29. Given that dyslipidemia is a key component of metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular outcomes are of the utmost importance in managing such patients, a combination approach may yield better results than GLP-1RA monotherapy in this aspect30. Future studies evaluating the combination of GLP-1RAs with statins or other lipid-lowering agents could provide further insights into the optimal treatment strategies for such patients.

The safety outcomes of this meta-analysis highlighted significant gastrointestinal and neurological side effects associated with GLP-1RA interventions31,32. Notably, we found a significant increase in nausea events among participants receiving GLP-1RAs compared to those treated with metformin or placebo. This effect was particularly pronounced when the control group received a placebo. Additionally, vomiting occurrences were also elevated, although no significant differences were observed in subgroup analyses when comparing to those given either placebo or metformin. In contrast, GLP-1RAs did not significantly increase the rates of diarrhea, constipation and bloating, suggesting a relatively favorable gastrointestinal safety profile for these interventions. Interestingly, there was a notable decrease in stomachache events among those receiving GLP-1RAs. Conversely, dizziness was more frequently reported in the GLP-1RA group, indicating a potential safety concern in this domain. Other side effects, including fatigue, headache and insomnia, did not show significant differences when compared to the control group. Importantly, the funnel plot analysis demonstrated no evidence of publication bias, enhancing the credibility of our findings. Overall, while GLP-1RAs may offer metabolic benefits in PCOS management, the increased risk of nausea and dizziness should be carefully considered in clinical practice33.

Overall, our meta-analysis underscores the value of GLP-1RAs as a multifaceted therapeutic option, particularly in PCOS patients with obesity and IR. However, the variability in efficacy across different metabolic and hormonal outcomes suggested that individualized treatment strategies should be considered. More robust, long-term studies are needed to elucidate the long-term safety profiles of GLP-1RAs and their role in combination therapy for metabolic syndrome. In the meantime, the evidence supports GLP-1RAs as a strong alternative to metformin, especially in cases where weight loss is a primary treatment goal.

This meta-analysis study had some limitations regarding the efficacy of GLP-1RAs on the anthropometric measurements, glucose homeostasis and hormonal changes. Notably, the high levels of heterogeneity in the studies analyzed as well as other measures such as variability in study populations, interventions and methodologies, could have affected the reliability of the results obtained. While our methods focused on comparing GLP-1RAs to metformin or placebo, we acknowledge the possibility that additional background interventions may have been employed across some studies. However, the included studies generally lacked sufficient detail regarding these concurrent interventions, making it difficult to fully assess their potential impact on the outcomes. This absence of comprehensive reporting limits our ability to perform stratified or sensitivity analyses to determine how such interventions may have influenced the observed heterogeneity, particularly in metabolic and hormonal outcomes. While GLP-1RAs showed significant reductions in BMI, body weight and WC compared to either metformin or placebo, the lack of consistency in fasting glucose and hormone levels suggested that the impact of the interventions might have varied significantly across the different patient groups. Additionally, certain outcomes, such as reductions in DHEAS and total testosterone levels, were not consistently significant when compared to metformin, highlighting potential variations in responses based on the comparator group. Although the funnel plots indicated no publication bias, the variability in the findings calls for caution in interpreting the overall effectiveness of GLP-1RAs under these parameters.

Conclusions

GLP-1RAs are effective in reducing body weight, BMI, and insulin resistance in patients with PCOS, particularly those with obesity or metabolic complications. These benefits support their role as an alternative or adjunct to metformin, especially when weight loss is a primary treatment goal. While side effects such as nausea and dizziness are more common, they are generally manageable and should be weighed against the potential metabolic improvements. The observed heterogeneity across studies highlights the importance of individualized treatment strategies based on patient profiles and therapeutic goals. Clinically, these findings suggest that GLP-1RAs could be incorporated into PCOS management guidelines, particularly for patients who do not respond adequately to first-line therapies or present with postprandial hyperglycemia and central obesity. Their integration into care pathways offers a more tailored approach, potentially improving long-term outcomes. Future research should focus on identifying the most responsive patient subgroups, evaluating long-term safety, and exploring combination therapies to enhance metabolic and reproductive outcomes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (Bing Tan).

References

Witchel, S. F., Oberfield, S. E. & Peña, A. S. Polycystic ovary syndrome: Pathophysiology, presentation, and treatment with emphasis on adolescent girls. J. Endocr. Soc. 3 (8), 1545–1573 (2019).

Patel, S. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), an inflammatory, systemic, lifestyle endocrinopathy. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 182, 27–36 (2018).

Teede, H., Deeks, A. & Moran, L. Polycystic ovary syndrome: A complex condition with psychological, reproductive and metabolic manifestations that impacts on health across the lifespan. BMC Med. 8 (1), 41 (2010).

Frankowski, R. et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Non-Alcoholic fatty liver disease, and metabolic repercussions: The vicious cycle and its interplay with inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(11), 9677 (2023).

Broekmans, F. J. et al. PCOS according to the Rotterdam consensus criteria: Change in prevalence among WHO-II anovulation and association with metabolic factors. Bjog 113 (10), 1210–1217 (2006).

Li, M. et al. Trends in insulin resistance: Insights into mechanisms and therapeutic strategy. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 7 (1), 216 (2022).

Hoeger, K. Obesity and weight loss in polycystic ovary syndrome. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North. Am. 28 (1), 85–97 (2001). vi-vii.

Shahmoradi, S. et al. The effect of magnesium supplementation on insulin resistance and metabolic profiles in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 202 (3), 941–946 (2024).

Osibogun, O., Ogunmoroti, O. & Michos, E. D. Polycystic ovary syndrome and cardiometabolic risk: Opportunities for cardiovascular disease prevention. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 30 (7), 399–404 (2020).

Taniguchi, C. M., Emanuelli, B. & Kahn, C. R. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: Insights into insulin action. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7 (2), 85–96 (2006).

Santoleri, D. & Titchenell, P. M. Resolving the paradox of hepatic insulin resistance. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7 (2), 447–456 (2019).

Guo, R. et al. Melatonin alleviates insulin resistance through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in ovary granulosa cells of polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod. Biol. 22 (1), 100594 (2022).

Shen, M. et al. Involvement of FoxO1 in the effects of follicle-stimulating hormone on Inhibition of apoptosis in mouse granulosa cells. Cell. Death Dis. 5 (10), e1475 (2014).

Sun, Z. et al. GLP-1/GLP-1R Signaling regulates ovarian PCOS-associated granulosa cells proliferation and antiapoptosis by modification of forkhead box protein O1 phosphorylation sites. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 1484321 (2020).

Rosenfield, R. L. Current concepts of polycystic ovary syndrome pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 32 (5), 698–706 (2020).

Fulghesu, A. M. et al. The impact of insulin secretion on the ovarian response to exogenous gonadotropins in polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 82 (2), 644–648 (1997).

Singh, S. et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome: Etiology, current management, and future therapeutics. J. Clin. Med. 12(4), 1454 (2023).

Xing, C., Zhao, H., Zhang, J. & He, B. Effect of Metformin versus Metformin plus liraglutide on gonadal and metabolic profiles in overweight patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 945609 (2022).

Xue, H., Zeng, L., He, H., Xu, D. & Ren, K. Effectiveness of acupuncture as auxiliary combined with Western medicine for epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1203231 (2023).

Rena, G., Hardie, D. G. & Pearson, E. R. The mechanisms of action of Metformin. Diabetologia 60 (9), 1577–1585 (2017).

LaMoia, T. E. & Shulman, G. I. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of Metformin action. Endocr. Rev. 42 (1), 77–96 (2020).

Meloni, A. R., DeYoung, M. B., Lowe, C. & Parkes, D. G. GLP-1 receptor activated insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells: Mechanism and glucose dependence. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 15 (1), 15–27 (2013).

Szczesnowicz, A., Szeliga, A., Niwczyk, O., Bala, G. & Meczekalski, B. Do GLP-1 analogs have a place in the treatment of PCOS? New insights and promising therapies. J. Clin. Med. 12(18), 5915 (2023).

de Athayde De Hollanda, A. et al. The efficacy and safety of GLP-1 agonists in PCOS women living with obesity in promoting weight loss and hormonal regulation: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Diabetes Compl. 38 (10), 108834 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Elevated circulating GPHB5 levels in women with insulin resistance and polycystic ovary syndrome: A cross-sectional study and multiple intervention studies. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 1010714 (2022).

Bednarz, K. et al. The role of Glp-1 receptor agonists in insulin resistance with concomitant obesity treatment in polycystic ovary syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(8), 4334 (2022).

Petrovic, A. et al. The role of GLP1-RAs in direct modulation of lipid metabolism in hepatic tissue as determined using in vitro models of NAFLD. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 45 (6), 4544–4556 (2023).

Aroda, V. R., Blonde, L. & Pratley, R. E. A new era for oral peptides: SNAC and the development of oral semaglutide for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 23 (5), 979–994 (2022).

Knudsen, L. B. & Lau, J. The discovery and development of liraglutide and semaglutide. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 10, 155 (2019).

Thongtang, N., Sukmawan, R., Llanes, E. J. B. & Lee, Z-V. Dyslipidemia management for primary prevention of cardiovascular events: Best in-clinic practices. Prev. Med. Rep. 27, 101819 (2022).

Filippatos, T. D., Panagiotopoulou, T. V. & Elisaf, M. S. Adverse effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 11 (3–4), 202–230 (2014).

Bettge, K., Kahle, M., Abd El Aziz, M. S., Meier, J. J. & Nauck, M. A. Occurrence of nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea reported as adverse events in clinical trials studying glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists: A systematic analysis of published clinical trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 19 (3), 336–347 (2017).

Goldberg, A. et al. Anti-obesity Pharmacological agents for polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis to inform the 2023 international evidence-based guideline. Obes. Rev. 25 (5), e13704 (2024).

Elkind-Hirsch, K., Marrioneaux, O., Bhushan, M., Vernor, D. & Bhushan, R. Comparison of single and combined treatment with exenatide and Metformin on menstrual Cyclicity in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93 (7), 2670–2678 (2008).

Elkind-Hirsch, K. E., Chappell, N., Shaler, D., Storment, J. & Bellanger, D. Liraglutide 3 mg on weight, body composition, and hormonal and metabolic parameters in women with obesity and polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized placebo-controlled-phase 3 study. Fertil. Steril. 118 (2), 371–381 (2022).

Frøssing, S., Nylander, M., Kistorp, C., Skouby, S. O. & Faber, J. Effect of liraglutide on atrial natriuretic peptide, adrenomedullin, and copeptin in PCOS. Endocr. Connect. 7 (1), 115–123 (2018).

Jensterle Sever, M., Kocjan, T., Pfeifer, M., Kravos, N. A. & Janez, A. Short-term combined treatment with liraglutide and Metformin leads to significant weight loss in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome and previous poor response to Metformin. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 170 (3), 451–459 (2014).

Jensterle, M., Salamun, V., Kocjan, T., Vrtacnik Bokal, E. & Janez, A. Short term monotherapy with GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide or PDE 4 inhibitor Roflumilast is superior to Metformin in weight loss in obese PCOS women: A pilot randomized study. J. Ovarian Res. 8, 32 (2015).

Jensterle, M., Kravos, N. A., Pfeifer, M., Kocjan, T. & Janez, A. A 12-week treatment with the long-acting glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist liraglutide leads to significant weight loss in a subset of obese women with newly diagnosed polycystic ovary syndrome. Horm. (Athens). 14 (1), 81–90 (2015).

Jensterle, M. et al. Semaglutide reduces fat accumulation in the tongue: A randomized single-blind, pilot study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 178, 108935 (2021).

Jensterle, M. et al. Semaglutide delays 4-hour gastric emptying in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and obesity. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 25 (4), 975–984 (2023).

Li, R., Mai, T., Zheng, S. & Zhang, Y. Effect of Metformin and exenatide on pregnancy rate and pregnancy outcomes in overweight or obese infertility PCOS women: Long-term follow-up of an RCT. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 306 (5), 1711–1721 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Efficacy of exenatide on weight loss, metabolic parameters and pregnancy in overweight/obese polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 87 (6), 767–774 (2017).

Nylander, M., Frøssing, S., Kistorp, C., Faber, J. & Skouby, S. O. Liraglutide in polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized trial, investigating effects on thrombogenic potential. Endocr. Connect. 6 (2), 89–99 (2017).

Tao, T. et al. Exenatide, Metformin, or both for prediabetes in PCOS: A randomized, Open-label, Parallel-group controlled study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 106 (3), e1420–e1432 (2021).

Zheng, S. et al. Short term monotherapy with exenatide is superior to Metformin in weight loss, improving insulin resistance and inflammation in Chinese overweight/obese PCOS women. Obes. Med. 7, 15–20 (2017).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

The Project for Enhancing Young and Middle-aged Teacher’s Research Basis Ability in Colleges of Guangxi (Grant No.2023KY0576).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SL, MQ and BT designed the whole study; SL, YD and JH collected the data and performed the analysis; SL and ML prepared the figures and tables; SL, MQ, SRS and BT wrote the manuscript; all the authors approved the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, S., Deng, Y., Huang, J. et al. Efficacy and safety of GLP-1 receptor agonists on weight management and metabolic parameters in PCOS women: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep 15, 16512 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99622-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99622-4