Abstract

This study explores the fabrication and characterization of porous ceramic scaffolds using the polyurethane sponge replication technique with commercial hydroxyapatite (SA-P) and Nile Tilapia bone-derived (FB-P) powders. Scaffolds sintered at 1300 °C and 1400 °C for 5 h exhibited high porosity (70–90%) with interconnected pores. SA scaffolds exhibited greater shrinkage due to differences in particle size and morphology. FTIR and XRD analyses confirmed hydroxyapatite (HAp), β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), and α-tricalcium phosphate (α-TCP) phases, with compositions influenced by sintering temperature. FB scaffolds developed a distinct blue coloration attributed to hydroxyl (OH−) and oxygen (Ov–PO4) vacancies within the HAp, while SA scaffolds appeared lighter. UV–vis and XANES analyses validated these compositional differences. In vitro cytotoxicity assays confirmed the biocompatibility of all scaffolds, with SA scaffolds exhibiting higher cell viability and proliferation than FB scaffolds, likely due to their optimized microstructure and phase composition. While FB scaffolds showed slightly lower cell proliferation, their bioactivity remained sufficient for bone tissue engineering applications. These findings suggest a promising strategy for selectively enhancing the OH− vacancy within the HAp structure and refining the HAp/β-TCP composition, thereby improving the biological performance of calcium phosphate scaffolds for biomedical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Calcium phosphate (CaP) materials, including hydroxyapatite (HAp), biphasic calcium phosphate (BCP), β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), and α-tricalcium phosphate (α-TCP), are extensively utilized in bone tissue engineering due to their biocompatibility and osteoconductive properties1,2. Moreover, CaP-based biomaterials facilitate osteoblast adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation, thereby promoting effective bone regeneration3. Among CaP materials, BCP, which consists of HAp and β-TCP, demonstrates superior osteoinductive and osteoconductive performance compared to single-phase CaP biomaterials when implanted in bone defect sites. This is attributed to the high resorbability of β-TCP and the low solubility of HAp, which together enhances bone remodeling and regeneration4,5. HAp promotes new tissue growth through osteoconduction, a process in which bone grows on the surface of materials without causing toxicity or inflammation6. Furthermore, the osteoconductive properties of HAp can be enhanced by surface charge modification, which influences cellular interactions and biological responses7,8. In contrast, β-TCP exhibits strong osteoinductive properties, promoting the differentiation of progenitor cells into osteoblastic lineages upon implantation in bone defects, thereby accelerating bone regeneration3,4. Although BCPs have attracted significant research interest due to their potential, the HAp/β-TCP ratio is crucial in controlling their degradation rate. Optimizing this ratio is essential to ensure that degradation aligns with the rate of bone tissue regeneration while maintaining biocompatibility, minimizing toxicity, and allowing safe elimination from the body without adversely affecting other organs4,9.

Scaffolds are 3D structures that provide structural support for bone augmentation, offering a surface for bone cell adhesion and promoting new bone formation9,10. An optimal scaffold features high porosity (80–90%) and an interconnected open-pore network (100–1250 µm)11, allowing bone cell infiltration, nutrient diffusion, and waste removal. This 3D pore structure also aids in the gradual degradation and clearance of scaffold materials without affecting surrounding tissues9,10. Ebrahimi et al.12 demonstrated that a scaffold composed of a 50:50 ratio of HAp/β-TCP fabricated using the polymeric sponge method exhibited promising characteristics in promoting cell proliferation, enhancing cell attachment, and stimulating alkaline phosphatase activity in MC3T3-E1 cells over 19 days. However, previous studies have indicated that several factors, including purity, crystallinity, surface area, porosity, and pore size, significantly influence the performance of scaffolds. Additionally, surface charge, charge imbalance, and vacancy formation are critical determinants of the biological properties of CaPs scaffold13,14. Among various types of vacancy formation, OH− vacancies in HAp have been shown to enhance bioactivity by increasing solubility, facilitating apatite formation, and improving osteoconductivity. Bystrov et al.15 suggested that the pale blue coloration observed in HAp powder derived from cod fish bones through chemical and thermal treatment is attributed to the presence of mixed vacancies, specifically OH− vacancies and Ov-PO4 defects, at the boundary of the UVA-UVB regions. In addition, Bas et al.16 synthesized HAp/β-TCP ceramics using powder derived from salmon bone and reported a color change from white to blue at 1200 °C and 1300 °C. However, their study did not provide specific details regarding the underlying mechanism responsible for the blue coloration in ceramics.

To date, there have been no reports on blue-colored CaP scaffolds or porous materials. Furthermore, the influence of defects or vacancies on color variations and their potential impact on the biological properties of these materials remains unexplored. This study investigates and compares the sintering behavior, phase composition, local atomic structure, and morphology—including surface area, porosity, and pore size—of scaffolds fabricated from Nile tilapia bone-derived powder and commercial hydroxyapatite powder. By analyzing these properties, it aims to provide fundamental insights into phase composition, morphology, the blue coloration due to local defect sites, and the bioactivity of fish bone-derived scaffolds. The findings underscore the potential of this sustainable raw material for biomedical applications, laying the foundation for future research and development.

Material and methods

Powder and scaffold preparations

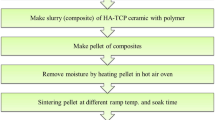

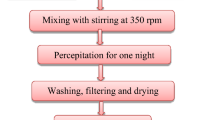

In this study, commercial hydroxyapatite powder (SA-P, Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC, 900203-50G, white powder) and HAp/β-TCP powder derived from fish bones (FB-P, white powder) were used as starting materials for scaffold fabrication. The extraction process followed the same procedures as in our previous work17. The scaffolds were produced using the polyurethane sponge replication technique. Cylindrical polyurethane sponges (45 ppi, 7.5 mm diameter × 7.5 mm height) were pretreated with 1 M NaOH solution for 24 h to enhance slurry adhesion to the sponge surface, following the method of Khallok et al.5. The treated sponges were then rinsed three times with deionized water and dried at 100 °C for 1 h. A slurry was prepared using polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, BF17W, Ajax Finechem Pty Ltd, New Zealand) as a binder to coat the polyurethane sponges during the scaffold fabrication process. Two slurries were prepared using a consistent powder-to-PVA solution ratio (9 g:15 mL), one incorporating SA-P and the other FB-P. A 5 wt% PVA solution was used for the SA-P slurry, and the mixture was stirred at 100 rpm for 30 min to achieve a homogeneous slurry. However, this approach caused particle agglomeration in the FB-P slurry. To address this, a 2.5 wt% PVA solution and a hand-mixing method were employed to ensure a uniform slurry suitable for coating. The slurries were coated onto polyurethane sponges, and the excess slurry was removed using a custom-built spin coater system. Then, the coated sponges were dried at 100 ºC for 5 min to form the first layer. This procedure was repeated for each subsequent layer until 5 layers were completed. The coated sponges were preheated at 600 °C in an electric furnace (XINKYO, SX2-4-17TP, China) at a 1 °C/min heating rate for 1 h to remove the polyurethane sponge template. Given that partial decomposition of HAp to β-TCP occurs within the 1200–1400 °C range4,17, the scaffolds in this study were sintered at 1300 and 1400 °C for 5 h at a heating rate of 5 °C/min in an air atmosphere. After sintering, all scaffolds were naturally cooled inside the furnace. The scaffolds sintered at 1300 °C (SA-13 and FB-13) and 1400 °C (SA-14 and FB-14) were comparatively studied for their sintering behavior, microstructure, phase composition, and biological properties. The results were investigated and discussed.

Powder and scaffold characterizations

The functional groups in the samples in the wavenumber range of 1750–550 cm−1 were examined using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, TENSOR27, Bruker, USA). High-quality X-ray diffraction (XRD, D8 ADVANCE, Bruker, USA) was employed to analyze the crystal structure and phase composition of the samples. XRD data were collected in the 2θ range of 10–90° with a step size of 0.02° and a scan time of 2s per step. Quantitative phase analysis was performed using the Rietveld refinement method with TOPAS software. The fitting employed the FP peak profile model, incorporating Lorentzian-type contributions for crystallite size and Gaussian-type contributions for a strain to refine the peak profiles.

Synchrotron radiation X-ray tomographic microscopy (SRXTM) was used to determine the porosity in the three-dimensional scaffolds, including total porosity, contact surface, and pore distribution. The SRXTM experiments were conducted at the XTM beamline (BL1.2W) of the Synchrotron Light Research Institute (SLRI), Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand. X-rays were generated by the 1.2 GeV Siam Photon Source, utilizing a 2.2 T multipole wiggler with a 23.5 mm. For X-ray imaging, the X-ray beam was collimated with a toroidal mirror located 890 m from the source, filtered through a beryllium window, and attenuated using 200-µm aluminum foil, resulting in a filtered beam with a mean energy of 11.5 keV. The sample position was situated 34 m from the radiation source. All X-ray projections were acquired at the isotropic voxel size of 3.61 µm with the X-ray imaging system comprising a YAG-Ce scintillator, 2X objective lens-coupled microscope (Optique Peter, France), and the PCO-edge 5.5 camera. Cylindrical scaffold samples (6 mm diameter × 6 mm height) were mounted on a rotary stage to collect the tomography data. For a complete dataset, two tomography scans, covering 0–180° with 0.2° increments, were performed on the top and bottom portions of each scaffold, and the data were combined using an image stitching strategy18. Then, the flat-field correction, normalization, and tomographic reconstruction were processed using Octopus Reconstruction software (Tescan Orsay Holding, Brno, Czech Republic). Three-dimensional porosity analysis was performed with Octopus Analysis (Tescan Orsay Holding, Brno, Czech Republic), and 3D volume representations of the scaffolds were generated using Drishti software, Version 2.6 (ANU Vizlab, Canberra, Australia).

UV–vis spectra were obtained using a UV–visible-Near Infrared Spectrometer (PerkinElmer Lambda 950, America) equipped with an integrating sphere covering the wavelength range of 200–800 nm. The measurements were performed on the SA- and FB scaffolds along with BaSO4 as a reference material. The indirect band gap energy (Eg) of the scaffolds was calculated using a modified Kubelka–Munk function, as detailed in previous research19,20:

where \(F\left({R}_{\infty }\right)\) or α represents the ratio of scattering to absorption in the material, calculated using

where \(R\) is the reflectance of the material. Here, \(h\) is the Planck’s constant, \(\upsilon\) is the photon frequency,\(B\) is a constant, and \({E}_{g}\) is the band gap energy. To determine the band gap values for the SA- and FB scaffolds, a plot of \(\left( {F\left( {R_{\infty } } \right) \cdot h\upsilon } \right)^{1/2}\) against \(h\upsilon\) was constructed.

X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) measurements were carried out at Beamline 8 of the Synchrotron Light Research Institute (SLRI), Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand, to investigate the local calcium site in the scaffolds. The measurements were conducted in transmission mode, with samples mounted on polyimide tape and installed in the holder. The spectra were recorded at room temperature within the photon energy range of the Ca K-edge (3938.5–4238.5 eV) using Ge (220) crystals generated from electron beam energy of 1.2 GeV and beam current of 120–80 mA. The monochromatic X-ray beam size on the sample position was 13 mm × 1 mm. The Ca K-edge XANES spectra were calibrated using the peak position of CaCO₃ at 4060.5 eV21, with CaCO₃ powder (Sigma-Aldrich) as the reference material. Data processing and analysis were performed using Athena software (Demeter System, Version 0.9.26)22.

Computational methodology

To investigate the electronic band structure and structure models of pristine HAp and vacancy case to compare with our experimental data, the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) code, which is based on first-principles density functional theory, was used for all calculations23. Electronic wave functions were expanded to fully relax and optimize the crystal structures using a plane wave basis set with a cut-off energy of 520 eV. Brillouin zone integration was performed using a Monkhorst-Pack24 mesh with a 3 × 3 × 6 grid in primitive cells. Using the projector augmented wave (PAW) approach25, the exchange–correlation potential was parameterized using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) parameterization26. The self-consistent iterations converged when the total energy and force difference between cycles were less than 0.001 meV/atom and 0.01 meV/Å, respectively.

The Ca1 and Ca2 K-edge XANES spectra were calculated based on defective structures containing Ov–OH−, Ov–PO₄, and OH− vacancies, which were obtained from first-principles density functional theory (DFT) optimizations27. The crystal structure of HAp is illustrated in Fig. 1. The self-consistent calculation was carried out within a sphere of radius 4.0 Å centered around the absorber Ca1 and Ca2 atoms. The full multiple scattering calculations were performed by considering all potential paths within a larger cluster, using a 7.0 Å radius as provided by the FEFF9 code28.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay and cell proliferation assay

In this study, the cytotoxicity and cell proliferation were evaluated by using (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2,5diphenyltetrazolium bromide) (MTT) assay. MC3T3-E1 subclone 14 cells (ATCC CRL-2594™) were maintained in Minimum Essential Medium-alpha with GlutaMAX supplement (MEM-α 1X + GlutaMAX™-I, Gibco, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (Gibco) and 1% Antibiotic–Antimycotic in alpha MEM (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA)) (100X, 10,000 units/mL of penicillin with 10,000 µg/mL of streptomycin, and 25 µg/mL Amphotericin B) (Anti-Anti, Gibco). Cells were incubated at 37 ºC and 5% CO2. The complete medium was replaced every two days until the MC3T3-E1 cells reached 90% confluence. The subcultivation ratio of 1:10 was used.

An in vitro cytotoxicity was conducted using direct contact based on ISO 10993-5 (Biological evaluation of medical devices, 2nd Edition) with some modifications29. Before the experiment, the scaffolds were decontaminated using autoclaving at 121 °C for 15 min and sterilized under UV light for 30 min in 96-well plates. One well would contain one scaffold. MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded on top of the scaffolds at a concentration of 1 × 104 cells per well. Twenty-four hours later, the medium in each well was replaced with the MTT reagent (MTT, Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Life Technologies Corporation, OR, USA) at the concentration of 1 mg/mL (in PBS). After 4 h, the MTT reagent was replaced with 100 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, AMRESCO, OH, USA) to dissolve the precipitated formazan crystals. The formazan solution (60 µL per well) was used to analyze the absorbance. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm (EPOCH, BioTek Instrument, VT, USA). All absorbance values were adjusted with a blank solution containing 60 µL of DMSO. The cells cultured in a blank well (without the scaffolds) served as a negative control or untreated, and the cell viability was adjusted to 100%. Cell viability was calculated using the following equation:

The cell proliferation assay was conducted in the same manner as the in vitro cytotoxicity study, except with a more extended incubation period. Cells were seeded onto the scaffolds and incubated for 3, 7, and 14 days. Cell viability was normalized against the untreated cells at 24 h incubation period.

Statistical analysis

Data in graphical format are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). In vitro studies data were performed using a Two-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey multiple comparisons test. The comparison was conducted by comparing the mean within the same incubation period. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 7.00 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com).

Results

Physical appearance and morphology of scaffolds

After sintering, the physical appearance of all scaffolds is shown in Fig. 2. The FB-13 and FB-14 scaffolds appeared blue, while the SA-13 scaffold exhibited a pale blue color. Interestingly, the SA-14 scaffold displayed a light blue color at higher sintering temperatures. Previous studies have linked color changes in HAp and β-TCP to incorporating ion substitutes, such as Mn and Cu, into Ca sites within their structures13,30,31. These substitutions can induce crystal defects, charge imbalances, and alterations in the electronic structure and optical properties of the materials. Despite the absence of Mn and Cu in the powder derived from fish bones17,32, the FB-13 and FB-14 scaffolds still displayed a blue coloration. This phenomenon is likely attributed to the formation of defects or vacancies within the HAp structures. Other characterization techniques were employed to provide an explanation, which will be discussed in "UV–vis analysis and scaffold color" section.

The SA scaffolds exhibited a higher degree of shrinkage, with a reduction of 47% in diameter and 33% in height, compared to the FB scaffolds, which shrank by 33% in diameter and 20% in height. As reported in our previous work17, FB-P powder consists of irregularly shaped particles with a larger particle size than the spherical particles of commercial hydroxyapatite (SA-P, Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC, 900203-50G). The shrinkage behavior during sintering is influenced by particle size and morphology. Smaller particles shrink more due to their higher surface area-to-volume ratio, enhancing sintering forces, accelerating diffusion, and increasing sintering stress. In contrast, larger particles exhibit lower shrinkage due to reduced surface energy and stress. Furthermore, particle morphology significantly influences densification, with irregularly shaped particles exhibiting distinct shrinkage patterns compared to spherical particles, primarily due to variations in packing density and diffusion pathways33,34. Therefore, the differences in scaffold shrinkage observed in this study can be attributed to the particle size and morphology of the powders used as starting materials for scaffold fabrication.

The microstructure and porosity of the scaffolds were analyzed using synchrotron radiation X-ray tomography at high resolution, with an isotropic voxel size of 3.61 μm. Three-dimensional volume representations of the SA-13, SA-14, FB-13, and FB-14 scaffolds in orthogonal views are presented in Fig. 3. Porosity was calculated from the voids within the analyzed volume, segmented based on the X-ray absorption contrast between the scaffold material and air. A summary of the porosity analysis is provided in Table 1 (in Supplementary Information). The porosity of the SA-13 and SA-14 ranged from 80 to 90%, whereas the FB-13 and FB-14 scaffolds exhibited slightly lower %porosity, between 70 and 80%. Further analysis indicated that over 99.9% of the pores in all scaffolds were classified as open pores. The pore distribution profiles of all scaffolds are shown in the histogram plots in Fig. 4, illustrating the distribution of separated pores based on their equivalent diameters. Notably, the majority of the contact surface area of the scaffolds was associated with pores having equivalent diameters of less than 100 μm.

In the previous section, we reported that the SA scaffolds exhibited higher shrinkage than the FB scaffolds. However, the total porosity fractions in Table 1 (in Supplementary Information) and the pore size trends show an opposite result. Although the porous structures, prepared under the same preparation condition, exhibited notable similarities across the scaffolds, the SA scaffolds had thinner struts than the FB scaffolds, as shown in Fig. 3. This observation may be attributed to a higher degree of shrinkage in each strut, influenced by the particle size and morphology, which results in a larger pore size and higher pore volume in the SA scaffolds compared to the FB scaffolds.

FTIR analysis

FTIR spectra of the two starting powders and scaffolds within the wavenumber range of 1750–550 cm−1 are shown in Fig. 5. Characteristic vibrations of H Ap were evident in both starting powders17,35. However, the presence of ν3PO43− (1126 cm−1) and ν1PO43− (948 cm−1) of β-TCP, as well as ν3PO43− (985 cm−1) of Mg-substituted beta-tricalcium phosphate (β-MgTCP) was detected in only the FB-P36,37. The HAp structure comprises two types of carbonate substitution: A-type at the hydroxyl site and B-type at the phosphate site, along with CO32− located on the surface of the SA-P and FB-P38,39. Following the sintering process, no vibration peaks associated with polyurethane were detected, confirming the complete removal of the polyurethane sponge. All scaffolds exhibited characteristic HAp vibrations without CO32−, A-type, and B-type peaks. The decrease in the OH− vibration at 629 cm−1 in the FB-13 and FB-14 scaffolds indirectly indicates a higher degree of Mg substitution for Ca than the FB-P sample40. As the sintering temperature increased, the PO43− bands in the 1200–900 cm−1 region of all scaffolds broadened compared to the powders, likely due to overlapping vibrations of PO43− in the HAp, β-TCP, and α-TCP structures. Furthermore, in this region, the PO43− bands of the FB-13 and FB-14 scaffolds were broader than those of the SA-13 and SA-14 samples, indicating differences in phase composition between the scaffolds sintered at the same temperature.

Crystal structure analysis

The XRD patterns of the powders and scaffolds collected at room temperature are presented in Fig. 6. The diffraction pattern of SA-P (Fig. 6a) showed only HAp (JCPDS No. 01–074-0565) without detectable impurities. In contrast, the pattern of FB-P (Fig. 6d) displayed both HAp and β-TCP phases, indexed to COD ID 9,002,213 and COD ID 1,517,238, respectively. The crystalline phase compositions of all samples, except SA-P, were quantitatively analyzed using Rietveld refinement. The fitting results in Fig. 6b–f demonstrated good agreement between experimental and calculated data, as indicated by the excellent goodness-of-fit (GOF) values. The refinement parameters, phase content percentages, and lattice parameters are summarized in Table 2 (in Supplementary Information). The phase composition of FB-P comprised 88% HAp and 12% β-TCP. Notably, the β-TCP and α-TCP phases in the FB scaffolds increased following sintering at 1300 °C and 1400 °C for 5 h, while the HAp phase decreased. This indicates that the HAp phase in FB-13 and FB-14 underwent greater decomposition into β-TCP and α-TCP phases. Although SA-P exhibited only the presence of HAp, partial phase transformation of HAp to β-TCP and α-TCP was observed in SA-13 and SA-14 scaffolds after sintering. The proportions of β-TCP and α-TCP phases increased with higher sintering temperatures. Furthermore, at the same sintering temperature, FB scaffolds exhibited higher amounts of β-TCP and α-TCP phases than SA scaffolds. These findings align with the FTIR results.

UV–vis analysis and scaffold color

The absorption spectra were identified, and the corresponding optical band gap was determined using UV–Vis spectroscopy and the modified Kubelka–Munk equation. This method enables a detailed understanding of the electronic and optical properties of the scaffolds. Figure 7a displays the UV–vis spectra of the FB and SA scaffolds. The SA scaffolds show no apparent absorption in the visible region (380–750 nm), consistent with previous reports on pure HAp41,42. In contrast, the FB scaffolds exhibit a prominent absorption band at approximately 300 nm and a weak band in the 550–700 nm wavelength region. This result may be attributed to defects in the HAp environment. A Tauc plot was employed to calculate the indirect band gap energy (Eg) of all scaffolds, and the Eg values for each scaffold, indicated by the dashed lines, are shown in Fig. 7b–e. The FB-13 and FB-14 scaffolds had an Eg of approximately 3 eV, while the SA scaffolds exhibited two distinct band gap values. The SA-13 scaffold revealed Eg values of 3.1 eV and 5.0 eV, whereas the SA-14 scaffold showed Eg values of 3.1 eV and 3.8 eV. These Eg values are consistent with the colors of the scaffolds.

The band structure and projected density of states (pDOS) of pure HAp are displayed in Fig. 8a. At the GGA-PBE level (5.23 eV), the computed Eg of pure HAp is 5.21 eV (an indirect band gap), which agrees with many reports43,44. O (2p) states dominate the top of the valence band, which spans energy levels from − 6 eV to 0 eV, although Ca (3d) states provide a very small contribution in this range. On the other hand, Ca (3d) states predominate in the lowest conduction band, which spans from 5 to 9 eV above the Fermi level. The modest presence of O (2s) and O (2p) states in this area suggests little hybridization between O and Ca atoms. The calculated Eg for OH− vacancy (OHv) in Fig. 8b is 1.55 eV. A defect state occurs at the mid-gap due to the O (2p) state, reducing the band gap of pure HAp by approximately 27.4%. For Ov-OH in Fig. 8c, the calculated Eg is 5.25 eV. These results show that an oxygen vacancy in the OH group does not significantly affect the energy gap of pure HAp, which remains high compared to the pure structure. The calculated Eg for Ov-PO4 in Fig. 8d is 3.94 eV. A defect state occurs at the mid-gap due to the O (2p) state hybridized with the P (3p) state, narrowing the band gap of pure HAp by approximately 24.4%. However, calculations rely on the exchange–correlation potential, which was parameterized using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) method. Consequently, the calculated values tend to be underestimated compared to experimental results. This suggests that OH− vacancy defects predominantly influence the sample color. The Eg corresponding to the blue visible light region typically ranges from 2.48 eV to 3.26 eV, corresponding to light wavelengths of approximately 380 nm to 495 nm. Moreover, the absorption of orange spectra (480–665 nm) subsequently reflects a blue color45,46. Based on our calculations, it is plausible that the blue color observed in our FB scaffolds (which exhibit a prominent absorption band at approximately 300 nm and a weak band in the 550–700 nm wavelength region), with an Eg of approximately 3 eV, might originate from OH− vacancies. Although the Eg corresponding to the blue visible light region was observed in the SA scaffolds, the low \({\left(\alpha h\upsilon \right)}^{1/2}\) intensity of the SA scaffolds resulted in a lighter blue color than that of the FB scaffolds. This may imply that the FB scaffolds contain more OH− vacancy than the SA scaffolds. Furthermore, the SA-14 scaffold shows no Eg characteristic of pure HAp, which may cause the different blue shade observed in the SA scaffolds.

XANES study

XANES is a spectroscopic technique that provides insights into the electronic structure of materials at the atomic level. The Ca K-edge XANES offers information about the local structure surrounding Ca atoms in the sample. The spectra can be compared with those of standard reference materials to identify the phases present in the sample. Figure 9a shows the normalized Ca K-edge XANES spectra of standard powders (HAp, α-TCP, and β-TCP) and scaffolds (FB-13, FB-14, SA-13, SA-14). Consistent with our Rietveld refinement analysis in "Crystal structure analysis" section, the results confirm that the samples comprise a mixture of HAp, α-TCP, and β-TCP phases.

To further investigate, linear combination analysis (LCA) was performed using the Ca K-edge XANES spectra of HAp, α-TCP, and β-TCP as references. Figure 9b compares the sample spectra with the linear combination fit (LCF), highlighting differences around 4051 and 4054 eV, which indicate the presence of crystal defects. These defects were analyzed by calculating oxygen vacancies in OH− (Ov–OH−) and PO₄ (Ov–PO4), as well as OH− vacancies, and comparing them with a perfect HAp crystal. The results show that the integral intensity of the Ca K-edge spectra decreases in the 4051–4054 eV region due to defects, except for the Ov–PO4 defect. Although the results are not highly conspicuous, they are supported by FTIR analysis, which shows the absence of the CO22⁻ group at the OH− site after sintering. This suggests that Ov–OH− and OH− vacancies may form during the sintering process. However, discrepancies between the experimental and calculated results imply that the simulated local defect sites do not fully represent the actual defect sites within the structure. XANES analysis confirms the presence of Ov–OH− and OH− vacancies in the HAp structure for all samples. Additionally, band structure calculations suggest that the sample color is influenced by OH− vacancy defects, which correspond to a band gap of 1.55 eV. This indicates that OH− vacancy formation is more prominent than Ov–OH− in FB-13 and FB-14 samples, whereas Ov–OH− formation dominates in SA-13 and SA-14 samples, likely due to their lower color intensity.

In vitro cytotoxicity and cell proliferation

The in vitro cytotoxicity of the four different types of scaffolds was assessed via an MTT assay. MC3T3-E1 cells were chosen since they are one of the most commonly used osteoblast-like cell lines for osteogenesis evaluation47. MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded onto the scaffolds and assessed for cell viability after 24 h incubation period. Cells on all scaffolds showed a relative cell viability higher than 70% (Day 1, Fig. 10). According to ISO 10993-5, all four types of scaffolds showed no sign of cytotoxicity.

Relative cell viability (%) of MC3T3-E1 cells that were seeded onto the scaffolds made of Fishbone HAp (FB-13C and FB-14C) and commercial HAp from Sigma Aldrich® (SA-13C and SA-14C). Untreated cells were seeded into blank wells without the scaffolds. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons were performed. ***p ≤ 0.001, **p ≤ 0.01, and *p ≤ 0.5.

The cell proliferation assay was conducted by seeding MC3T3-E1 cells onto the scaffolds and incubating them for longer periods of time. The cell number increased on days 3 and 7, as evidenced by an increase in the percentage of relative cell viability when compared to untreated cells on day 1. When comparing groups at the same time point, they are not significantly different. However, on day 14, cells seeded on the scaffolds showed significantly higher cell viability than those untreated (Day 14, Fig. 10). Among all scaffolds tested, the SA-13 gave the highest percent cell viability, resulting in the highest cell proliferation ability.

Discussion

SA and FB scaffolds were fabricated using the polyurethane sponge replication technique, employing commercial hydroxyapatite and fish bone-derived powders as precursors. Due to differences in particle size and morphology, SA scaffolds exhibited greater shrinkage, leading to thinner struts, larger pores, and higher porosity (80–90%) compared to FB scaffolds (70–80%). The FB-13 and FB-14 scaffolds displayed a distinct blue coloration, whereas SA-13 and SA-14 exhibited lighter blue shades, indicating a higher concentration of OH− vacancy defects in FB scaffolds. Phase analysis revealed an increased presence of β-TCP and α-TCP in FB scaffolds, attributed to the enhanced decomposition of hydroxyapatite, while SA scaffolds retained a higher proportion of the original HAp phase. XANES analysis further confirmed OH− vacancies in the HAp structure for all samples, consistent with FTIR analysis.

Cells cultured on the scaffolds exhibited significantly higher viability compared to the untreated control group, indicating that the scaffolds effectively support cell attachment and proliferation. This enhanced performance is partly attributed to the macro- and micro-porous architecture, which increases the available surface area and facilitates greater cell adhesion. Furthermore, the XANES analysis confirmed the presence of OH⁻ vacancies in both SA and FB scaffolds. These vacancies are pivotal in promoting cell–scaffold interactions by inducing localized positive charges along the c-axis of the HAp crystal lattice48,49. These positively charged domains enhance the electrostatic attraction of negatively charged biomolecules, particularly adhesion-promoting proteins, leading to increased protein adsorption on the scaffold surface7,50. The biological performance of calcium phosphate scaffolds is closely linked to such physicochemical modifications. OH⁻ vacancies not only modulate the surface charge but also improve the biointerface characteristics essential for cellular responses. The MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblast cell line, commonly employed in osteogenic studies, exhibits an overall negative surface charge due to the presence of sialic acid residues and glycoproteins within the cell membrane and glycocalyx51,52. As a result, electrostatic interactions between the negatively charged cell surface and the positively charged regions on the scaffold significantly enhance cell adhesion, spreading, and osteogenic activity.

Various factors can affect bone growth, such as osteoconduction, osteoinduction, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and vascularization. The size and connectivity of the pores in the scaffolds influence the osteogenicity of the scaffold53. Currently, the relationship between scaffold pore size and bone cell activity is not fully understood. However, there are reports on the optimum scaffold pore size to achieve significant bone growth. Han et al.54 reported that bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) showed the highest viability when they grew on 200 µm pore-size scaffolds. Klawitter et al.55 suggested that pore sizes ranging from 100 to 135µm are suitable for bone ingrowth, while larger pore sizes showed no increase in the bone ingrowth rate. In our study, most pores from all scaffolds tested had diameters of less than 100 µm, which could benefit bone cell proliferation. Comparing all groups, FB-13 had a higher number of larger pore sizes when compared to SA-13, SA-14, and FB-14 (Fig. 4). However, FB-13 gave a percentage of cell viability at the same level as FB-14 (lower than SA-13 and SA-14). While pore size can impact cell activity, other factors may be more crucial.

Scaffold composition is another factor to consider. Scaffolds made from the SA-P showed higher cell viability than scaffolds made from the FB-P. SA scaffolds contained higher HAp, lower β-TCP, and α-TCP. Among the four groups tested, SA-13 had the highest HAp content with no β-TCP and little amount of α-TCP. Reports suggested that HAp, β-TCP56, and α-TCP57 positively affected cell growth. From our study, having a higher ratio of β-TCP and α-TCP resulted in lower cell growth on day 14 (Fig. 10). Since the β-TCP and α-TCP can dissolve at a faster rate than those of HAp, these substances could alter the environment, such as pH of the medium57. Moreover, the presence of Mg-substituted β-TCP (β-MgTCP) and the higher total pore surface in FB scaffolds, as compared to SA scaffolds, can accelerate the degradation rates58,59. It is possible that the dissolution rate of β-TCP and α-TCP could be faster than the bone formation rate, leading to suboptimal bone formation60. Although data beyond day 14 were not collected, it is plausible that the rapid degradation of FB scaffolds adversely affected the local microenvironment through pH shifts and increased ionic concentrations, thereby impairing cell viability and activity. In contrast, the more stable SA scaffolds, characterized by their slower degradation rate and higher HAp content, may have provided a more favorable and sustained environment for osteoblast adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. The mechanical stability offered by the higher HAp content also supports prolonged osteogenic activity, which is advantageous for long-term bone regeneration. We acknowledge, however, that these interpretations are based on observed trends up to day 14 and theoretical considerations derived from material degradation behavior. Therefore, further long-term in vitro and in vivo studies are required to validate the extended bioactivity and regenerative potential of these scaffolds.

The findings of this study showed that the scaffolds derived from fish bone had lower cell viability and proliferation than those fabricated using commercial powder. However, their bioactivities were still considered suitable for bone tissue engineering. This result highlights the potential of fish bone waste as a promising starting material for developing scaffolds in various biomedical applications, particularly in bone tissue engineering. In future research, we intend to design the heat treatment and sintering processes for the scaffolds derived from fish bone to increase OH− vacancies in the HAp structure. We also aim to explore different HAp/β-TCP ratios without the α-TCP phase. These material combinations will allow us to design scaffolds with desirable degradation rates that align with the pace of bone tissue regeneration, thus enabling their utilization in various settings where the tissue regeneration rate changes.

Conclusion

This study examined the structural, compositional, and biological properties of scaffolds fabricated via the polyurethane sponge replication technique using commercial hydroxyapatite (SA-P) and fish bone-derived (FB-P) powders. After sintering at 1300 °C and 1400 °C for 5 h, SA scaffolds (SA-13 and SA-14) exhibited more significant shrinkage than FB scaffolds (FB-13 and FB-14), attributed to differences in particle size and morphology. All scaffolds displayed a similar porous architecture (70–90% porosity) with predominantly open pores. FTIR and XRD analyses confirmed the presence of HAp, β-TCP, and α-TCP, with phase composition varying with temperature. FB scaffolds exhibited a distinct blue coloration, while SA scaffolds showed lighter shades, indicating a higher concentration of OH− vacancy and Ov–PO4 defects, as validated by UV–vis and XANES analyses. Despite the observed coloration, in vitro cytotoxicity assays confirmed the biocompatibility of all scaffolds, demonstrating their ability to support cell viability. Among the scaffolds, SA-13 exhibited the highest cell proliferation, likely attributed to its optimized pore structure and phase composition, specifically the balance of HAp, β-TCP, and α-TCP, as well as the presence of OH− vacancies, which facilitate cell adhesion and growth. Although FB scaffolds exhibited lower cell viability and proliferation compared to SA scaffolds, their bioactivity remained within an acceptable range for bone tissue engineering applications.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ebrahimi, M., Botelho, M. G. & Dorozhkin, S. V. Biphasic calcium phosphates bioceramics (HA/TCP): Concept, physicochemical properties and the impact of standardization of study protocols in biomaterials research. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 71, 1293–1312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2016.11.039 (2017).

Hou, X. et al. Calcium phosphate-based biomaterials for bone repair. J. Funct. Biomater. 13, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb13040187 (2022).

Jeong, J., Kim, J. H., Shim, J. H., Hwang, N. S. & Heo, C. Y. Bioactive calcium phosphate materials and applications in bone regeneration. Biomater. Res. 23, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40824-018-0149-3 (2019).

Khiri, M. Z. A. et al. Crystallization behavior of low-cost biphasic hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate ceramic at high sintering temperatures derived from high potential calcium waste sources. Res. Phys. 12, 638–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2018.12.025 (2019).

Khallok, H. et al. Preparation of biphasic hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate foam using the replication technique. Ceram. Int. 46, 22581–22591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.06.019 (2020).

Sadat-Shojai, M., Khorasani, M.-T., Dinpanah-Khoshdargi, E. & Jamshidi, A. Synthesis methods for nanosized hydroxyapatite with diverse structures. Acta Biomater. 9, 7591–7621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2013.04.012 (2013).

Kobayashi, T., Nakamura, S. & Yamashita, K. Enhanced osteobonding by negative surface charges of electrically polarized hydroxyapatite. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 57, 477–484. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4636(20011215)57:4 (2001).

Bodhak, S., Bose, S. & Bandyopadhyay, A. Bone cell–material interactions on metal-ion doped polarized hydroxyapatite. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 31, 755–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2011.01.003 (2011).

Preethi Soundarya, S., Haritha Menon, A., Viji Chandran, S. & Selvamurugan, N. Bone tissue engineering: Scaffold preparation using chitosan and other biomaterials with different design and fabrication techniques. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 119, 1228–1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.08.056 (2018).

Nikolova, M. P. & Chavali, M. S. Recent advances in biomaterials for 3D scaffolds: A review. Bioactive Mater. 4, 271–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2019.10.005 (2019).

Polo-Corrales, L.L.-E., Ramirez-Vick, M. & Jaime, E. Scaffold design for bone regeneration. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 14, 15–56 (2014).

Ebrahimi, M., Pripatnanont, P., Suttapreyasri, S. & Monmaturapoj, N. In vitro biocompatibility analysis of novel nano-biphasic calcium phosphate scaffolds in different composition ratios. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 102, 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.32979 (2014).

Bee, S.-L. & Hamid, Z. A. A. Hydroxyapatite derived from food industry bio-wastes: Syntheses, properties and its potential multifunctional applications. Ceram. Int. 46, 17149–17175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.04.103 (2020).

Granito, R. N. et al. Hydroxyapatite from fish for bone tissue engineering: A promising approach. Int J Mol Cell Med 7, 80–90. https://doi.org/10.22088/ijmcm.Bums.7.2.80 (2018).

Bystrov, V. S. et al. Oxygen vacancies, the optical band gap (Eg) and photocatalysis of hydroxyapatite: Comparing modelling with measured data. Appl. Catal. B 196, 100–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.05.014 (2016).

Bas, M. et al. Mechanical and biocompatibility properties of calcium phosphate bioceramics derived from salmon fish bone wastes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 8082 (2020).

Khamkongkaeo, A. et al. Sintering behavior and mechanical properties of hydroxyapatite ceramics prepared from Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) bone and commercial powder for biomedical applications. Ceram. Int. 47, 34575–34584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.08.372 (2021).

Kyrieleis, A., Ibison, M., Titarenko, V. & Withers, P. J. Image stitching strategies for tomographic imaging of large objects at high resolution at synchrotron sources. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 607, 677–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2009.06.030 (2009).

Kalaiselvi, V., Mathammal, R., Vijayakumar, S. & Vaseeharan, B. Microwave assisted green synthesis of Hydroxyapatite nanorods using Moringa oleifera flower extract and its antimicrobial applications. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Med. 6, 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijvsm.2018.08.003 (2018).

Makuła, P., Pacia, M. & Macyk, W. How to correctly determine the band gap energy of modified semiconductor photocatalysts Based on UV–vis spectra. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 6814–6817. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b02892 (2018).

Rajendran, J., Gialanella, S. & Aswath, P. B. XANES analysis of dried and calcined bones. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 33, 3968–3979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2013.05.038 (2013).

Ravel, B. & Newville, M. Athena, artemis, hephaestus: Data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron. Radiat. 12, 537–541. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0909049505012719 (2005).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/0927-0256(96)00008-0 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.13.5188 (1976).

Perdew, J. P. & Zunger, A. Self-interaction correction to density-functional approximations for many-electron systems. Phys. Rev. B 23, 5048–5079. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.23.5048 (1981).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865 (1996).

Hedin, L. & Lundqvist, B. I. Explicit local exchange-correlation potentials. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 4, 2064. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3719/4/14/022 (1971).

Rehr, J. J. & Albers, R. C. Theoretical approaches to x-ray absorption fine structure. Rev. Mod. Phys. 72, 621–654. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.72.621 (2000).

ISO 10993–5:2009 Biological evaluation of medical devices — Part 5: Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity, https://www.iso.org/standard/36406.html.

Li, Y., Klein, C. P. A. T., Zhang, X. & de Groot, K. Relationship between the colour change of hydroxyapatite and the trace element manganese. Biomaterials 14, 969–972. https://doi.org/10.1016/0142-9612(93)90187-7 (1993).

Sadetskaya, A. V., Bobrysheva, N. P., Osmolowsky, M. G., Osmolovskaya, O. M. & Voznesenskiy, M. A. Correlative experimental and theoretical characterization of transition metal doped hydroxyapatite nanoparticles fabricated by hydrothermal method. Mater. Charact. 173, 110911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2021.110911 (2021).

Khamkongkaeo, A. et al. Antibiotic-loaded hydroxyapatite scaffolds fabricated from Nile tilapia bones for orthopaedics. Int. J. Pharm.: X 5, 100169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpx.2023.100169 (2023).

Cheng, Y., Cui, Z., Cheng, L., Gong, D. & Wang, W. Effect of particle size on densification of pure magnesium during spark plasma sintering. Adv. Powder Technol. 28, 1129–1135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2017.01.017 (2017).

Wakai, F., Akatsu, T. & Shinoda, Y. Shrinkage and disappearance of a closed pore in the sintering of particle cluster. Acta Mater. 54, 793–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2005.09.039 (2006).

Fara, A. N. K. A., Pragash, G. & Abdullah, H. Z. Effect of calcination on the properties of hydroxyapatite from tilapia fish bones. Adv. Mater. Res. 1125, 474–478. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.1125.474 (2015).

Butler, D. H. & Shahack-Gross, R. Formation of biphasic hydroxylapatite-beta magnesium tricalcium phosphate in heat treated salmonid vertebrae. Sci. Rep. 7, 3610. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-03737-2 (2017).

Weinand, W. R. et al. Dynamics of the natural genesis of β-TCP/HAp phases in postnatal fishbones towards gold standard biocomposites for bone regeneration. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 279, 121407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2022.121407 (2022).

Leventouri, T. et al. Crystal structure studies of human dental apatite as a function of age. Int. J. Biomater. 2009, 698547. https://doi.org/10.1155/2009/698547 (2009).

Pan, H. & Darvell, B. W. Effect of carbonate on hydroxyapatite solubility. Cryst. Growth Des. 10, 845–850. https://doi.org/10.1021/cg901199h (2010).

Cacciotti, I., Bianco, A., Lombardi, M. & Montanaro, L. Mg-substituted hydroxyapatite nanopowders: Synthesis, thermal stability and sintering behaviour. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 29, 2969–2978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2009.04.038 (2009).

Rulis, P., Ouyang, L. & Ching, W. Y. Electronic structure and bonding in calcium apatite crystals: Hydroxyapatite, fluorapatite, chlorapatite, and bromapatite. Phys. Rev. B 70, 155104. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.70.155104 (2004).

Matsunaga, K. & Kuwabara, A. First-principles study of vacancy formation in hydroxyapatite. Phys. Rev. B 75, 014102. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.75.014102 (2007).

Avakyan, L. A. et al. Optoelectronics and defect levels in hydroxyapatite by first-principles. J. Chem. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5025329 (2018).

Sailuam, W., Phacheerak, K., Atipong, B., Fongkaew, I. & Limpijumnong, S. Elastic and mechanical properties of hydroxyapatite under pressure: A first-principles investigation. Comput. Cond. Matter 24, e00481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cocom.2020.e00481 (2020).

Kumar, S. et al. Orange light spectra filtered through transparent colored polyvinyl chloride sheet enhanced pigment content and growth of Arthrospira cells. Biores. Technol. 319, 124179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2020.124179 (2021).

Eknapakul, T. et al. Impacts of pre-treatment methods on the morphology, crystal structure, and defects formation of hydroxyapatite extracted from Nile tilapia scales. RSC Adv. 14, 4614–4622. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3RA07556G (2024).

Izumiya, M. et al. Evaluation of MC3T3-E1 cell osteogenesis in different cell culture media. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 7752 (2021).

Roopalakshmi, S., Ravishankar, R., Belaldavar, S., Prasad, R. G. S. V. & Phani, A. R. Investigation of structural and morphological characteristic of hydroxyapatite synthesized by sol-gel process. Mater. Today: Proc. 4, 12026–12031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2017.09.126 (2017).

Tsukada, M., Wakamura, M., Yoshida, N. & Watanabe, T. Band gap and photocatalytic properties of Ti-substituted hydroxyapatite: Comparison with anatase-TiO2. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2011.01.017 (2011).

Metwally, S. & Stachewicz, U. Surface potential and charges impact on cell responses on biomaterials interfaces for medical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 104, 109883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2019.109883 (2019).

Kanyo, N. et al. Glycocalyx regulates the strength and kinetics of cancer cell adhesion revealed by biophysical models based on high resolution label-free optical data. Sci. Rep. 10, 22422. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80033-6 (2020).

Chen, L., McCrate, J. M., Lee, J. C. M. & Li, H. The role of surface charge on the uptake and biocompatibility of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles with osteoblast cells. Nanotechnology 22, 105708. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/22/10/105708 (2011).

Abbasi, N., Hamlet, S., Love, R. M. & Nguyen, N.-T. Porous scaffolds for bone regeneration. J. Sci.: Adv. Mater. Devices 5, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsamd.2020.01.007 (2020).

Han, Y. et al. Effect of pore size on cell behavior using melt electrowritten scaffolds. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2021.629270 (2021).

Klawitter, J. J., Bagwell, J. G., Weinstein, A. M. & Sauer, B. W. An evaluation of bone growth into porous high density polyethylene. J Biomed. Mater. Res. 10, 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.820100212 (1976).

Hou, X. et al. Calcium phosphate-based biomaterials for bone repair. J. Funct. Biomater. 13, 187 (2022).

Ehara, A. et al. Effects of α-TCP and TetCP on MC3T3-E1 proliferation, differentiation and mineralization. Biomaterials 24, 831–836. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0142-9612(02)00411-8 (2003).

Diez-Escudero, A., Espanol, M., Beats, S. & Ginebra, M. P. In vitro degradation of calcium phosphates: Effect of multiscale porosity, textural properties and composition. Acta Biomater. 60, 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2017.07.033 (2017).

Salma-Ancane, K., Stipniece, L., Putnins, A. & Berzina-Cimdina, L. Development of Mg-containing porous β-tricalcium phosphate scaffolds for bone repair. Ceram. Int. 41, 4996–5004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2014.12.065 (2015).

Ishikawa, K. et al. Physical and Histological comparison of hydroxyapatite, carbonate apatite, and β-tricalcium phosphate bone substitutes. Materials (Basel) 11, 1993. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11101993 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Faculty of Science, Khon Kaen University, for providing the FTIR facility. We acknowledge the Synchrotron Light Research Institute (Public Organization), Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand, for granting access to the XTM and XAS facilities. Special thanks to Dr. Wantana Klysubun for guiding the XAS experiments. We thank Suranaree University of Technology, Thailand, for providing computing resources. This research project is supported by the Second Century Fund (C2F), Chulalongkorn University, Thailand.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. A.W.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing—original draft. T.C.: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis. S.C.: Investigation, Formal analysis. C.R.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization. A.P.: Methodology, Formal analysis. D.V.: Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization. A.B.: Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization. W.S.: Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization. A.R.B.: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. B.L.: Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khamkongkaeo, A., Wongrakpanich, A., Chanamuangkon, T. et al. Effect of vacancies on blue-colored calcium phosphate scaffolds derived from Nile tilapia bone powder. Sci Rep 15, 24058 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99708-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99708-z