Abstract

This study investigates the influence of back pressure on the mass ejection coefficient (u) of low-pressure methane-air ejectors through a combined approach of one-dimensional mathematical modeling and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations. By establishing a quadratic relationship between u and back pressure (hc), we reveal three distinct operational regimes: a slow growth phase, a rapid escalation phase, and a critical degradation phase. CFD results validate the theoretical model with a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.9941 in the quadratic region. A key finding is the identification of a linear correlation between the critical back pressure (hc,crit) and nozzle pressure (hn), expressed as hc,crit = − 0.0629 hn + 0.8966 Pa. This work provides actionable guidelines for optimizing ejector geometry and operating conditions in residential gas appliances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the growth of the global population, the global energy demand has also intensified, but the use of energy is also accompanied by various problems, such as greenhouse gas emissions and global warming. Therefore, energy savings and emission reductions are imperative, and reducing unnecessary external machinery and designing more energy-efficient equipment are good choices1. As a fluid device that is simple to manufacture and easy to use, the ejector can be used to replace compressors and pumps to a certain extent. If there is no problem in the design and use of the ejector, the equipment can achieve energy-saving effects.

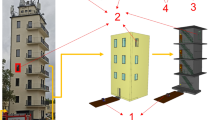

The ejector is a device that utilizes the turbulent diffusion of a jet to mix two fluids with different pressures, causing energy exchange between them. Because it is mainly through the high-pressure fluid to induce the low-pressure fluid, the two are mixed to achieve the required pressure state, without the need for other devices to provide any power, so it can effectively save energy. It primarily consists of a nozzle, converging tube, mixing tube, and diffuser tube (Fig. 1). The main advantages that make ejectors frequently used in industry include a structure with no moving parts2, the absence of lubricants or bearings3, reliability and low installation cost4.

Owing to their simple structure, low cost, and easy maintenance, ejectors are now widely used in various fields, such as aircraft engines5, refrigeration system mixing equipment6,7, heat pumps8, desalination equipment9 and gas‒air mixing systems for gas equipment.

Therefore, many scholars have optimized ejectors. J.H. Keenan and his team first studied ejectors. In an article in 1942, an equal area mixing model in which the working nozzle was located in an equal section area was studied. The results revealed that the ejection coefficient of equal-area mixing was greater than that of equal-pressure mixing; only when the area of equal section and the nozzle throat was less than a certain value was equal-area mixing closer to equal-pressure mixing. A comparison of the experimental results with the theoretical calculations revealed that the nozzle had an optimal position when the ejection coefficient was the largest. As the area ratio increased, the ejection coefficient also increased, but it decreased with increasing expansion ratio. A paper published in 195010 researched the isobaric mixing of ejectors and established a one-dimensional model. The hypothesis of equal pressure mixing of the working fluid and the ejected fluid was put forward earlier; that is, the working fluid and the ejected fluid were mixed at a certain pressure and were completely mixed at the outlet. These results were verified through experiments.

Szabolcs Varga et al.11 used CFD software to find optimal area ratios and nozzle positions for the best ejection coefficient, noting no effect from the length of the mixing area. Natthawut Ruangtrakoon et al.12 tested 8 different nozzle structures, showing significant influence on ejector performance. Randheer L. Yadav et al.13 found the ejection coefficient increases with the ratio of nozzle-throat distance to throat diameter, peaking at a maximum value. Eames et al.14 studied steam ejectors in jet refrigeration, finding that ejector back pressure exceeding a critical value greatly affected performance, which could be improved by reducing diffuser throat area, increasing ejection pressure, or moving the nozzle closer to the throat.

In summary, although the various physical parameters of the ejector have many effects on the ejection performance, few studies have investigated how to improve the mass ejection coefficient of the ejector in a low-pressure environment like in civil gas appliances. Therefore, studying how to effectively improve the mass ejection coefficient of ejectors in low-pressure environments and back pressures is highly important.

In civil gas appliances, ejectors, such as instant water heaters and gas stoves, are widely used. In these civil gas appliances, natural gas is usually used as the working fluid, and air is used as the ejected fluid. The natural gas is ejected from the nozzle, and the air is ejected and mixed in the ejector. After exiting the diffuser tube, the natural gas reaches the combustion chamber for combustion. Fang Yuanyuan et al.15 establish fluid dynamics model for the burner and make use of FULENT to simulate atmospheric gas burner and to provide the flow pressure and density fields. It provides technical parameters for the design of the burner and benefits to improve it and decreases the members of the experiment. Hu Peng16 texted four groups of experiments are conducted under different heat input and primary air inlet area to analyze the impact of heat input and primary air inlet area on the relationship between primary air ratio and the suction pressure. Liang Xiaomin17 analyzed the relationship between the injection capacity of a burner and the negative pressure in combustion zone. The influence of the negative pressure in combustion zone on the primary air coefficient of the burner is quantitatively investigated. The primary air injected by an atmospheric burner is sensitive to the negative pressure in combustion zone, and the negative pressure should increase the primary air coefficient.

From the above introduction, it can be seen that the research on gas-air ejectors based on low-pressure environments is basically superficial, and the influence of back pressure on ejectors has not been studied in principle. Therefore, in this work, a one-dimensional mathematical model was used to study the effect of back pressure on the performance of the ejector when there was back pressure in the low-pressure ejector, and CFD was used to simulate and verify it. In this way, the influence of back pressure on the low-pressure injector is obtained, which provides an effective idea for improving the working efficiency of the low-pressure injector.

Mathematical modeling

The calculation of the mathematical model for the ejector is usually based on the law of conservation of mass, the law of conservation of momentum and the law of conservation of energy.

Therefore, the ejector model can be roughly interpreted as methane with a mass flow rate of \({m}_{g}\) and a pressure of \({p}_{n}\) entering the nozzle. During the process of passing through the nozzle, it drops from pressure \({p}_{n}\) to pressure \({p}_{no}\), and its velocity increases to \({v}_{g.no}\). High-speed methane has high kinetic energy. Owing to the momentum exchange of the airflow, the frontier mass flow rate is \({m}_{a}\), and the air with pressure \({p}_{a.sc}\) is sucked into the ejector at a velocity of \({v}_{sc}\).

When the airflow enters the mixing tube, the velocity distribution is very uneven. Through energy and momentum exchange between the air and methane, the momentum and energy of the methane are reduced and converted to air. Finally, the velocity field at the exit of the mixing tube is basically uniform. At this time, the velocity of the mixed flow composed of methane and air is \({v}_{m}\), and the static pressure is \({P}_{m}\).

In the diffuser tube, the dynamic pressure of the mixed flow is converted to static pressure, its velocity decreases from \({v}_{m}\) to \({v}_{d}\), and the static pressure increases from \({P}_{m}\) to \({P}_{d}\). \({P}_{d}\) can be considered the static pressure required by the ejector to reach the outlet. At this time, the velocity field of the mixed flow should be uniform; otherwise, the efficiency of the ejector will be reduced.

The following assumptions were considered for the rejecter mathematical model formulation:

-

a)

Steady-state flow;

-

b)

Variations in the gravitational potential energy between ejector inlets and outlet sections are neglected;

-

c)

The average values of pressure and velocity are considered in the ejector;

-

d)

Both the working and ejected fluids are incompressible flows;

-

e)

The mixing between both the working and ejected flows is complete inside the mixing section.

Since the compressibility of the air flow is neglected, the following equations can be obtained:

where \(u\) is the mass ejection coefficient, \(u={m}_{a}/{m}_{g}\), and where \(s\) is the relative density of gas, \(s={\rho }_{g}/{\rho }_{s}\).

Since the mixing process of methane and air in the mixing tube is very complicated and the mixing type also results in energy loss from impact and friction, it is better to use the law of conservation of momentum in the calculation in the mixing tube. When calculating, the inlet section of the shrink tube and the outlet section of the mixing tube are taken as the calculated section, and the momentum equation is established as Eq. (7).

According to the energy conservation law, we can obtain the following equation:

For the nozzle, the energy conservation law can be written as Eq. (18).

For the shrink chamber, the energy conservation law can be written as Eq. (18).

For the mixing section, the energy conservation law can be written as Eq. (18).

For the diffuser section, the energy conservation law can be written as Eq. (18).

where \(n\) is the expansion factor of the diffuser tube, \(n={F}_{d}/{F}_{m}\).

In this model, for the position behind the diffuser tube, there will be a burner. To ensure that the mixed flow can reach the combustor at a certain speed, after the diffuser tube, its momentum and energy need to overcome the flow resistance loss, the accelerated energy loss of the mixed flow due to combustion and heating, and the dynamic pressure loss at the outlet of the fire hole.

The flow resistance loss can be written as Eq. (18).

where \({L}_{1}\) is the flow resistance loss, \({\xi }_{c}\) is the friction resistance coefficient of the fire hole, and \({v}_{c}\) is the velocity of the mixed flow at the fire hole.

The accelerated energy loss of the mixed flow due to combustion and heating can be written as Eq. (18).

where \({L}_{2}\) is the accelerated energy loss of the mixed flow due to combustion and heating and where \(T\) is the temperature of the mixed flow at the fire hole.

The dynamic pressure loss can be written as Eq. (14).

where \({L}_{3}\) is the dynamic pressure loss at the fire hole.

Therefore, the required static pressure in the position behind the diffuser tube can be written as Eq. (18).

where \({h}_{c}\) is the static pressure of the combustion chamber, \({K}_{1}={\xi }_{h}+2T/288-1\).

For \({P}_{n}\gg {L}_{sc}; {F}_{m}\gg {F}_{n}\), \({P}_{n}+{L}_{sc}\approx {P}_{n}\), and \(F-1\approx F\) can be obtained. By substituting the other equations into Eq. (7), Eq. (16) can be obtained.

where \(K=2\psi +{\xi }_{m}+{\xi }_{d}-\left({n}^{2}-1\right)/{n}^{2}\), \({K}_{2}=\left(2{{\mu }_{sc}}^{2}-1\right)/{{\mu }_{sc}}^{2}\), \({F}_{1}={F}_{n}/{F}_{c}\), and \({F}_{c}\) is the area of the fire hole.

To show the relationship between the efficiency of the ejector and the properties of each physical structure, Eq. (16) can be sorted into Eq. (18).

Compared with the characteristic equation of the traditional low-pressure ejector, Eq. (17) mainly adds the back-pressure term \({h}_{c}\). In many civil gas appliances, the back pressure is affected by the combustion temperature, the size of the combustion chamber and the fan. Especially in civil gas appliances with fans, the back pressure is approximately − 20 Pa to − 100 Pa, which cannot be ignored. Therefore, Eq. (17) can better describe the influence of various parameters in the low-pressure ejector on the mass ejection coefficient.

From Eq. (18), it can be concluded that the ejector’s mass ejection coefficient \(u\) is related to many factors; some parameters are positive, and some are negative. Among these factors, in addition to the physical properties and structure of the ejector itself, the back pressure has an important effect on the ejection efficiency. Because it is easy to control, in many engineering examples, a pump is usually installed in the area behind the combustion chamber to control the back pressure of the combustion chamber, thereby further improving the ejection efficiency of the low-pressure negative-pressure ejector.

Reorganizing Eq. (18) yields Eq. (18). From Eq. (18), we can obtain the relationship between the ejector back pressure \({h}_{c}\) and the mass ejection coefficient \(u\).

In the following chapters, the author mainly uses CFD software to simulate and calculate a common ejector and investigate whether the influence trend of the back pressure on the ejection efficiency is the same as the trend obtained by the mathematical model.

CFD for flow simulations

The geometric structure of the ejector used in the model is shown in Fig. 2. The ejector model is set to be axisymmetric, uses a structured grid, and refines the grid at the nozzle to improve calculation accuracy. The solution method is coupled implicitly, and the realizable \(k-\upvarepsilon\) model is selected. Reference6 compared the results of using the 3D model and the 2D axisymmetric model and reported that the results were very similar. However, considering the computational grid, time and other issues, the ejector model can be 2D axisymmetric.

To calculate more accurately, the boundary needs to be set. For the ejector, the nozzle can be set as the pressure inlet, the ejected air inlet is set as the pressure inlet, and the ejector outlet is set as the pressure outlet. To simplify the calculation and analysis, we make some assumptions here:

-

a)

The working gas and ejected gas are incompressible ideal gases;

-

b)

The working gas and ejected gas are relatively even at the ejection entrance;

-

c)

The working process of the ejector is adiabatic;

-

d)

There is no chemical reaction between the working gas and the ejected gas during the mixing process;

-

e)

The flow in the ejector is a steady-state process;

-

f)

The influence of gravity is not considered.

For the ejector, the gas inlet can be set as the pressure inlet, the air inlet as the pressure inlet, and the ejector outlet as the pressure outlet.

The simulation conditions are shown in Table 1.

ANSY ICEM CFD was used to mesh the computational domain, and the two-dimensional planar block model was used to create a structural mesh, and at the same time, the mesh near the nozzle was encrypted. Moreover, the mesh in the horizontal direction is also appropriately encrypted to avoid the numerical calculation error caused by the excessive aspect ratio of the mesh near the interface. Three different mesh densities were used to verify the grid quality, and the number of grids was 15,378, 18,176, and 24,174, respectively, and the calculation results showed that when the number of grids was 18,176, the calculation accuracy was better and the calculation speed was faster. Finally, the total number of meshes obtained is 18,176, and the minimum orthogonal mass of the meshes is 0.51.

The physical model use Species Transport model and does not involve chemical reactions, with methane/air selected for the components.

In the physical property setting of the mixture, the incompressible ideal gas model is used for density, the mixing-law model is used for the specific heat capacity of constant pressure, the ideal-gas-mixing-law is used for the calculation of thermal conductivity and viscosity, and the kinetic-theory is used for the calculation of mass diffusivity and thermal diffusivity.

The combustion process is solved by a pressure-based steady-state solver, the coupling of pressure and velocity is resolved by the separation algorithm Simple, and the difference between the pressure term is PRESTO! The format, the differential format of momentum, energy, composition, etc., all adopts the second-order windward difference.

Results

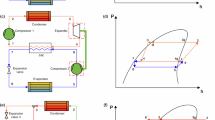

In a previous study, a mathematical model of a low-pressure extraordinary-pressure ejector was derived. After simulation, various conditions inside the ejector were obtained in an extraordinarily high-pressure environment. Figure 3 shows the internal velocity distribution diagram of the ejector. Figure 4 shows its internal static pressure.

Figures 3 and 4 show the mixing process of the two gases inside the ejector. The working gas enters the ejector at a certain speed and draws the ejected gas by its own energy. In the mixing tube, the working gas and ejected gas exchange energy and momentum, the mixing tends to be uniform, the speed tends to be stable, and the two are evenly mixed and flow out from the diffuser tube.

Figure 5 shows the change in the mass ejection coefficient \(u\) when the combustion chamber pressure \({h}_{c}\) increases under different nozzle pressures \({h}_{n}\). It can be seen from the figure that as \({h}_{c}\) decreases, \(u\) basically increases slowly and then increases rapidly; then, it quickly reaches the most unfavorable point and finally returns to a slow increase.

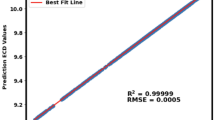

According to Eq. (18), we can conclude that under certain conditions, the back pressure \({h}_{c}\) of the ejector and the mass ejection coefficient \(u\) have a quadratic relationship. After CFD simulation, Fig. 6 shows the relationship between the back pressure \({h}_{c}\) of the ejector and the mass ejection coefficient \(u\) under a certain nozzle pressure.

Figure 6a,b show the relationship between \({h}_{c}\) and \(u\) when \({h}_{n}\) is within a certain range. In Fig. 6a, when \({h}_{c}\) is between − 1000 Pa and 600 Pa, the curve in the figure does not have a clear trend.

However, in Fig. 6b, when the value of \({h}_{c}\) is reduced from − 36 Pa to 600 Pa, the relationship between \({h}_{c}\) and \(u\) basically shows a quadratic relationship, and the trend line is \({h}_{c}=1.30236{u}^{2}-66.795+817.63({R}^{2}=0.9941).\) Therefore, the relationship between \({h}_{c}\) and \(u\) within a certain range is indeed a quadratic relationship, as calculated via Eq. (18). Moreover, when it exceeds this range, the mass ejection coefficient \(u\) of the ejector decreases sharply, resulting in a significant decrease in the efficiency of the ejector.

Figures 6 and 7 indicate that the relationship between \({h}_{c}\) and \(u\) still shows a quadratic trend within a certain range when \({h}_{n}\) is different. The figure shows that there is a difference between the CFD simulation results and the simulation results of the 1D mathematical model. This is because in the 1D mathematical model, we considered only the mixing situation along the airflow direction and did not consider the uniformity of the airflow at each position on the section. Figures 3 and 4 also reveal that the pressure and velocity in each section are not evenly distributed, which results in a difference between the two, but both trends decrease overall. This also shows that the advantage of the 1D mathematical model is that it quickly determines the influence of the back pressure \({h}_{c}\) on \(u\) from the influencing factors related to the mass ejection coefficient \(u\). The CFD simulation can more quantitatively calculate the specific change trend between the back pressures \({h}_{c}\) and \(u\).

After exceeding this range, there is always a \({h}_{c}\) value that is the most unfavorable for the mass ejection coefficient \(u\), and this most unfavorable point \({h}_{c}\) has a trend related to the \({h}_{n}\) value, as shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8 illustrates the relationship between the most unfavorable point of the mass ejection coefficient (u) and the back pressure (hc.crit) under different nozzle pressures (hn): hc.crit = − 0.0629hn + 0.8966(R2 = 1). The most unfavorable point refers to the condition where the mass ejection coefficient (u) experiences a rapid change due to the back pressure (hc), significantly affecting the ejector’s performance.

-

Existence of a Critical Point: The figure shows that for different nozzle pressures (hn), there exists a critical back pressure (hc.crit) at which the mass ejection coefficient (u) rapidly decreases. This critical point indicates a significant change in the ejector’s performance.

-

Impact on Ejector Performance: The rapid change in u at the critical hc value implies a loss of efficiency in the ejector. This is particularly important in low-pressure environments with negative back pressure, where the ejector’s performance can be severely impacted.

-

Adaptability of the Ejector: The existence of this critical point highlights the need for the ejector to adapt to different operating conditions. In designs where the ejector operates under varying back pressures, it is crucial to avoid the critical hc.crit values that lead to rapid changes in u.

-

Design Considerations: When designing ejectors for low-pressure applications, especially those with negative back pressure, it is essential to account for the critical hc.crit values. This can be achieved by optimizing the ejector’s geometry and operating conditions to avoid the critical points where u rapidly decreases.

-

Operational Guidelines: For existing ejectors, understanding the relationship between hc and u can help in setting operational parameters to avoid the critical points. This can improve the overall efficiency and reliability of the ejector in residential gas appliances.

Figure 8 demonstrates that under different nozzle pressures (hn), there exists a critical back pressure (hc.crit) at which the mass ejection coefficient (u) rapidly changes, significantly affecting the ejector’s performance. This finding underscores the importance of designing and operating ejectors to avoid these critical points, especially in low-pressure environments with negative back pressure. By doing so, the ejector’s adaptability and efficiency can be significantly enhanced.

Figure 9 shows the comparison of the CFD simulation results when the comparison is at the most unfavorable point and the quadratic relationship interval.

Figure 9 shows that when the working gas is ejected from the nozzle in a quadratic relationship, its flow velocity does not change much from the suction section to the mixing pipe, but it is the lowest. However, when it is at the most unfavorable point, the flow velocity of the working gas decreases sharply after it enters the mixing tube, resulting in a substantial reduction in the mass ejection coefficient.

Conclusion

In a previous study, we used the one-dimensional mathematical model method to derive the relationship between the mass ejection coefficient u of the ejector and the back pressure \({h}_{c}\). Within a certain range, the back pressure \({h}_{c}\) has a quadratic relationship with the mass ejection coefficient \(u\).

Then, we simulated the ejector via CFD software, and the simulation results were basically consistent with the results obtained via the one-dimensional mathematical model. However, after exceeding a certain range, the mass ejection coefficient \(u\) of the ejector decreases sharply with decreasing combustion chamber pressure \({h}_{c}\) and gradually recovers after reaching the most unfavorable point. The combustion chamber pressure corresponding to this most unfavorable point has a linear relationship with the nozzle pressure \({h}_{n}\). The influence of other parameters inside the ejector on the mass ejection coefficient \(u\) still needs further discussion.

Under different nozzle pressures (hn), there exists a critical back pressure (hc) at which the mass ejection coefficient (u) rapidly changes, which hc.crit = − 0.0629hn + 0.8966(R2 = 1), significantly affecting the ejector’s performance. This finding underscores the importance of designing and operating ejectors to avoid these critical points, especially in low-pressure environments with negative back pressure. By doing so, the ejector’s adaptability and efficiency can be significantly enhanced.

In short, this research can help us better understand the influence of back pressure on the mass ejection coefficient and provide some reference for how to effectively improve the mass ejection coefficient in the design process of low-pressure ejectors.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \(m\) :

-

Mass flow rate

- \(V\) :

-

Volume flow rate

- \(\rho\) :

-

Density

- \(u\) :

-

Mass ejection coefficient

- \(s\) :

-

Relative density of gas

- \(v\) :

-

Velocity

- \(F\) :

-

Cross-sectional area

- \(\psi\) :

-

Uneven coefficient of velocity field

- \(P\) :

-

Static/mean pressure

- \(R\) :

-

Nozzle-to-mixing-section area ratio

- \(L\) :

-

Pressure loss

- \(D\) :

-

Degree of diffusion in diffuser tube

- \(T\) :

-

Temperature

- \(\xi\) :

-

Friction resistance coefficient

- \(\mu\) :

-

Nozzle flow coefficient

- a:

-

Referred to the air

- g:

-

Referred to the gas

- mix:

-

Referred to the mixed flow

- no:

-

Referred to the nozzle outlet

- m:

-

Referred to the mixing section

- sc:

-

Referred to the shrink chamber

- d:

-

Referred to the diffuser

- n:

-

Referred to the nozzle

- b:

-

Referred to the burner

- c :

-

Referred to the combustion chamber

- crit :

-

Referred to the critical

References

de Oliveira Marum, V. J. et al. Performance analysis of a water ejector using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations and mathematical modeling. Energy 220, 119779 (2021).

Park, B. H., Lim, J. H. & Yoon, W. Fluid dynamics in starting and terminating transients of zero-secondary flow ejector. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 29(1), 327–339 (2008).

Little, A. B., Garimella, S. & DiPrete, J. P. Combined effects of fluid selection and flow condensation on ejector operation in an ejector-based chiller. Int. J. Refrigerat. 69, 1–16 (2016).

Shestopalov, K. O., Huang, B. J., Petrenko, V. O. & Volovyk, O. S. Investigation of an experimental ejector refrigeration machine operating with refrigerant R245fa at design and off-design working conditions. Part 1. Theoretical analysis. Int. J. Refrigerat. 55, 201–211 (2015).

Kracíka, J. & Dvořák, V. Experimental and numerical investigation of an air to air supersonic ejector for propulsion of a small supersonic wind tunnel. EPJ Web. Conf. 92, 1–5 (2015).

Pianthong, K., Seehanam, W., Behnia, M., Sriveerakul, T. & Aphornratana, S. Investigation and improvement of ejector refrigeration system using computational fluid dynamics technique. Energy Convers. Manag. 48(9), 2556–2564 (2007).

Ruangtrakoon, N., Aphornratana, S. & Sriveerakul, T. Experimental studies of a steam jet refrigeration cycle: Effect of the primary nozzle geometries to system performance. Exp. Thermal Fluid Sci. 35(4), 676–683 (2011).

Riffat, S. B., Gan, G. & Smith, S. Computational fluid dynamics applied to ejector heat pumps. Appl. Therm. Eng. 16(4), 291–297 (1996).

Wang, C., Wang, L., Wang, X. & Zhao, H. Design and numerical investigation of an adaptive nozzle exit position ejector in Mult effect distillation desalination system. Energy 140, 673–681 (2017).

Keenan, J. H., Neumann, E. P. & Lustwerk, F. An investigation of ejector design by analysis and experiment. Appl. Mech. 17(3), 299–309 (1950).

Varga, S., Oliveira, A. C. & Diaconu, B. Numerical assessment of steam ejector efficiencies using CFD. Int. J. Refrig 32(6), 1203–1211 (2009).

Ruangtrakoon, N., Thongtip, T., Aphornratana, S. & Sriveerakul, T. CFD simulation on the effect of primary nozzle geometries for a steam ejector in refrigeration cycle. Int. J. Thermal Sci. 63, 133–145 (2013).

Yadav, R. L. & Patwardhan, A. W. Design aspects of ejectors: Effects of suction chamber geometry. Chem. Eng. Sci. 63(15), 3886–3897 (2008).

Eames, I. W., Wu, S., Worall, M. & Aphornratana, S. An experimental investigation of steam ejectors for applications in jet-pump refrigerators powered by low-grade heat. Proc. Institut. Mech. Eng. Part A: J. Power Energy 213(5), 351–361 (1999).

Fang, Y. Y., Guo, Q. & Fu, Z. C. Numerical simulation of the injector in the low pressure atmospheric gas burner. J. Beijing Instit. Civil Eng. Architect. 22, 55–58 (2006).

Peng, H. U., Zhongcheng, F. U. Relationship between primary air factor and negative pressure in combustion chamber. Gas and Heat, 22(2):104–106.

Liang, X., Xie, D., Wen, M. & Ye, G. Influence of negative pressure in combustion zone on self-proportioning characteristics of atmospheric burners. Gas Heat 31(12), B08-B10 (2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C. and P.D. wrote the main manuscript text and H.L. prepared the equations. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, C., Liu, H. & Duan, P. Research on the ejection performance of an ejector with low pressure and back pressure. Sci Rep 15, 15970 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99722-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99722-1