Abstract

In the face of the pressing climate change crisis, Molecular Solar Thermal Energy Storage (MOST) Systems offer a promising avenue for efficient energy storage. This study focuses on the potential of systems based on azobenzene and gives a comprehensive framework for assessing unique azobenzene variations for MOST applications. A high-throughput screening process, underpinned by semi-empirical extended tight binding methods, has been developed to enable exploration of the vast chemical space of azobenzenes. The codebase for the established screening procedure, including methodologies and tools, is organized and shared through a GitHub repository ensuring transparency and reproducibility. We test our high throughput screening procedure on 37,729 azobenzene derivatives and highlight that it is robust enough to facilitate subsequent studies that will dive deeper into the potential of azobenzenes in MOST applications. Future endeavors will focus on expanding the dataset, correlating energies with higher-level calculations, and harnessing advanced statistical and machine learning techniques to optimize the selection and performance of azobenzenes in MOST systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change is not just a distant threat or an abstract concept, it is a pressing crisis that requires more than mere acknowledgment1. The scientific community is acutely aware of these challenges, and new technologies are actively being developed to explore various avenues of harnessing sustainable energy sources. However, these advancements are not without complications. In the context of solar energy, one such challenge is the “duck curve,” which illustrates the daily mismatch between solar energy production and electricity demand2 (Fig. 1).

The “duck curve” illustrating the mismatch between solar energy production and electricity demand. Source U.S. Energy Information Administration (2021)2.

This issue brings us to a critical aspect of sustainable energy, namely storage of energy. The issue of energy storage is not new and extends beyond solar energy to almost all energy sectors3,4. For solar energy storage, one intriguing concept has emerged to use molecular systems to store energy. This concept, known as Molecular Solar Thermal Energy Storage (MOST) is an approach where a molecule would absorb sunlight, changing to a higher-energy isomer5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Later, when needed, the molecule would revert back to its lower-energy state, releasing the stored energy as heat. The ideal MOST molecule would need to meet several criteria19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. First, it should absorb sunlight, which means its excitation wavelength must fall within the solar spectrum. Second, the photoisomer should possess higher energy than the parent state to enable effective energy storage. Third, the conversion process should be efficient, necessitating a good quantum yield. Fourth, the molecule should maintain its charged energy state for an extended period, implying the need for a sufficiently high back-reaction barrier. Additionally, the molecule should be capable of undergoing multiple charging and discharging cycles. Furthermore, the absorption spectra of the parent molecule and the photoisomer should not overlap significantly to prevent competition for photons. Lastly, the molecule should be non-toxic, avoiding elements like heavy metals31,32. Finding a molecule that satisfies all these criteria is consequently a monumentally complex task33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40.

Azobenzene, a molecule depicted in Fig. 28,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42, has been extensively explored as a potential candidate for molecular solar thermal (MOST) systems. The photoisomerization reaction of interest involves the E/Z isomerization around the central nitrogen–nitrogen double bond of the molecule. In this process, the E (trans) isomer serves as the parent state, while the Z (cis) isomer represents the higher-energy charged state. The energy storage mechanism of azobenzene involves the absorption of light by the E isomer, inducing isomerization to the Z isomer and storing the absorbed energy as chemical energy in the form of the higher-energy isomer. Upon triggering, the Z isomer can revert to the E isomer, releasing the stored energy as heat43. This reversible photoisomerization makes azobenzene a promising molecule for MOST applications.

Azobenzene stands out in MOST systems due to its robustness in the charging cycle and decent storage capacity. However, it faces several challenges, including overlapping absorption spectra between its isomers and less-than-ideal storage times. Adding functional groups as substituents to azobenzene or modifying the ring systems can help with overcoming these issues. This task is complex not only because of the vast array of substituents that can be added but also due to the inversely related properties that need optimisation. For example, adding substituents to alter the excitation wavelength can increase the molecular weight, reducing the energy density. Similarly, substituents that destabilise the energy-charged meta-stable isomer to enhance energy storage might inadvertently lower the back-reaction barrier, resulting in a shorter storage time.

The isomerization of azobenzenes occurs through a complex mechanism involving four possible pathways: rotation, inversion, concerted inversion, and concerted rotation44. Each pathway represents a different manner in which the central N=N double bond rearranges between the trans and cis configurations. The predominance of a specific pathway is highly sensitive to intramolecular effects, such as electronic interactions between substituents on the phenyl rings, steric hindrance, and solvent polarity. Additionally, supramolecular interactions including \(\pi -\pi\) stacking and hydrogen bonding can significantly influence the isomerization pathways and efficiencies45. These interactions can alter the energy landscape of the isomerization process, affecting both the kinetics and thermodynamics of the reaction. Understanding both intramolecular and supramolecular factors is crucial for optimising the photoisomerization properties of azobenzenes for MOST applications.

Given these complexities and the overwhelming number of possible substituent combinations, traditional experimental synthesis and high-level computational methods are often too resource-intensive for efficient exploration. Therefore, innovative methods are needed for candidate selection. One approach is to combine several desired features into a single metric, such as solar conversion efficiency46,47. To achieve high solar conversion efficiency, the molecule should effectively absorb sunlight, offer good energy storage capacity, and have an appropriate reaction barrier for isomerization. These criteria encompass key features desired from an ideal MOST system, effectively narrowing down the features to consider when evaluating azobenzene derivatives.

Considering the vast number of possible azobenzene variations and the limitations of computational resources, the type of calculations performed is crucial. To address this issue, we propose using extended tight-binding (xTB) methods, which provide a balance between computational efficiency and accuracy48. The xTB methods are an extension of traditional tight-binding models, incorporating extended parameters and empirical adjustments to improve predictive performance. These methods can rapidly estimate geometries, energies, and other molecular properties across diverse chemical spaces, making them suitable for high-throughput screening applications.

Specifically, the GFN-xTB (Geometry, Frequency, Non-covalent, extended Tight Binding) method has demonstrated success in providing dependable estimates of molecular geometries, vibrational frequencies, and non-covalent interactions48. While xTB methods are generally reliable for geometry optimizations and relative minimum-energy comparisons between conformers, it is important to note that transition state barrier energies are highly sensitive to the computational protocol used. The isomerization process involves electronic states with significant multi-reference character49, particularly in the transition state and excited-state regions. This multi-reference nature poses additional computational challenges, as standard single-reference methods like DFT may not adequately capture the electronic structure of these states. Presently, we have taken the approach where the results extracted from xTB calculations, particularly regarding reaction barriers, are validated by density functional theory (DFT) methods.

One of the key advantages of xTB methods is their adaptability to incorporate experimental data and first-principles calculations. By parameterizing the model using density functional theory (DFT) or other quantum chemical methods, xTB can provide a computationally efficient yet accurate description of electronic properties. Extended tight binding methods play a pivotal role in designing and understanding molecular systems capable of solar energy storage. These methods enable the modeling of complex electronic interactions within light-absorbing molecules and their interfaces with storage media and the methods allow for the design of molecular systems where absorbed solar energy is converted into stable charge-separated states, which are essential for long-term energy storage. While xTB methods offer a compromise between computational speed and predictive accuracy, assessing the accuracy of these calculations for the properties of interest is crucial. In previous research xTB has been shown to provide consistent results when compared with DFT50. In our approach, we perform initial screenings using xTB calculations to quickly evaluate a large number of azobenzene derivatives. Promising candidates identified in this preliminary screening are then subjected to more accurate and computationally intensive methods to validate the xTB results. This two-tiered approach ensures efficient use of computational resources without compromising the accuracy of the final results.

Furthermore, recent advances in molecular screening and performance prediction methods have provided powerful tools for exploring large chemical spaces efficiently51. These methods combine computational chemistry with machine learning techniques to predict the properties of new compounds, accelerating the discovery of promising candidates for MOST systems.

The entire process involves creating potential azobenzene candidates and quickly screening them based on solar conversion efficiency as an identifier for a good MOST system. This approach helps us identify promising candidates for further study, streamlining the exploration process.

The subsequent sections of this study will delve into the theoretical background, computational approach, and discussion of the screening process. “Computational approach: screening methodology” section provides the theoretical background for our investigation. “Chemical space selection” section contains the selection process of the molecular compounds. In “Numerical test results and discussion” section we present the numerical results and the final section contains the conclustions. We will provide a more detailed description of the azobenzene energy storage mechanism, considering both intramolecular and supramolecular interactions, as these factors greatly influence the performance of MOST applications. The conclusion and outlook sections will examine the results and complications encountered during the creation of this project and chart the future course of this research in the exciting field of MOST systems. The screening process is based on recent work50,52,53.

Azobenzene stands out among energy storage materials due to its intrinsic chromophore group, which undergoes visible color changes during the cis-trans isomerization process43,54,55,56,57,58,59,60. This unique feature eliminates the need for additional chromophores to monitor energy storage processes, offering a significant advantage over other solar thermal energy storage systems. The ability to directly observe color changes simplifies the investigation of energy storage and release dynamics, making azobenzene-based systems an attractive research focus. The isomerization of azobenzene molecules is triggered by light irradiation, inducing a structural transformation that results in a notable change in molecular dimensions. Specifically, the length of the molecular axis shifts from approximately 9 \(\text{\AA }\) in the trans form to 5.5 \(\text{\AA }\) in the cis form. This molecular size alteration can aggregate across multiple azobenzene molecules, producing macroscopic deformation that is both visible and functional. This property has paved the way for innovative applications, particularly in the development of light-driven flexible actuators. Various polymer structures incorporating azobenzene units have been designed and synthesized. The interaction between the azobenzene units and the polymer matrix enables efficient light-driven energy conversion, allowing the controlled release of the stored energy in the form of mechanical work. These advancements highlight the potential for leveraging azobenzene’s isomerization mechanism in multifunctional systems. The distinctive isomerization mechanism of azobenzene during heat storage and release processes provides unparalleled versatility. This versatility broadens the application scope of azobenzene-based energy storage systems, extending their potential use to numerous domains.

Computational approach: screening methodology

To systematically understand and optimize azobenzene derivatives, a robust computational approach is indispensable. In our previous studies on bicyclic dienes, we utilized a screening procedure based on xTB methods to estimate key MOST parameter for those compounds. Herein, we review that screening procedure along with the necessary modification that we have made to accommodate the screening of azobenzenes for MOST technology. By using this computational framework, we aim to navigate the vast chemical space of azobenzenes, laying the groundwork for an automated calculation process and setting the stage for the subsequent studies on this topic.

As outlined above, MOST systems consist of molecules capable of undergoing photoisomerization to a higher-energy isomer. This process allows for the storage of energy within the conformation of the molecule. When necessary, this stored energy is released as the molecule reverts to its original isomer. An optimal MOST system should operate within the visible light range (300 to 800 nm), possess a prolonged storage life, and store a substantial amount of energy. Three key parameters for a MOST system are therefore

-

Solar spectrum match: Ensuring the system can effectively harness sunlight for the photoisomerization reaction.

-

Reaction barrier: Determining the barrier that dictates the storage time of the stored energy.

-

Energy storage capacity: The actual amount of energy the system can store.

All three of these can be readily estimated using computational chemistry methods such as xTB and the high throughput screening procedure therefore estimates these and utilize them to determine the efficiency of solar energy storage. The efficiency can be quantified from these parameters using the parameter \(\eta _{\text {limit}}\), which represents the theoretical maximum percentage of photons absorbed by the molecule that is stored as energy in the system. \(\eta _{\text {limit}}\) is calculated as

where \(\Delta E_{\text {S}}\) is the predicted storage energy, \(\Delta E_{\text {cut}} = \Delta E_{\text {S}} + \Delta E_{\text {TBR}}\) where \(\Delta E_{\text {TBR}}\) is the predicted thermal back reaction barrier, \(P_{\text {sun}}(\omega )\) is the solar irradiation at frequency \(\omega\) according to the AM1.5G solar spectrum, the attenuation of sunlight \(A(\omega )\). It is given as

and the fraction of light absorbed by the reactant azobenzene \(S(\omega )\) is

where \(\epsilon _\text {R}(\omega )\) and \(\epsilon _\text {P}(\omega )\) are the molar extinction coefficients, and \(c_\text {R}\) and \(c_\text {P}\) are the molar concentrations of reactant and product, respectively. The quantum yield of photoisomerization is assumed to be 1 giving the upper theoretical limit of the solar conversion efficiency. We assume a total molar concentration of 1 M along with a conversion of 50% such that \(c_\text {R} = c_\text {P} = 0.5\) M. The absorption of each molecule is modeled by convolution of the first absorption with an oscillator strength of at least 0.01 using a Gaussian with full width half maximum of 0.25 eV. There is no universally defined optimal SCE threshold, as it depends on balancing multiple factors, including photoconversion efficiency, energy storage capacity, and thermal stability. However, previous studies show a system with a thermal stability of 120 kJ/mol would allow seasonal storage with a theoretical maxium of 10.6%46. In practical applications, SCE values above 3% are generally considered promising. Among the designed molecules, several exhibited higher SCE values than conventional azobenzene derivatives, and we highlight the most promising candidates in Table 2.

To facilitate the calculation of \(\eta _{\text {limit}}\) and thus explore and understand the ability of an azobenzene candidate to act as a MOST system, we need to perform investigations of the reactant and product equilibrium structures, their excitation energies and associated oscillator strengths, and the transition state connecting them. For this purpose, we employ a range of different tools to construct a screening code. The codebase for screening is primarily written in Python and a component of the code is the QMC package61 which is used to store molecular conformations and calculation results. Although the version employed in this project incorporates certain modifications tailored to our specific needs, the original package and its source code can be found here: https://github.com/koerstz/QMC. Additionally, the RDKit package62 played an instrumental role in managing molecular properties, handling SMILES strings, and performing various other molecular operations. Lastly, all xTB calculations are performed using the Semiempirical Extended Tight-Binding Program Package63.

The general flow of the screening process is depicted in Fig. 3. Before initiating the process outlined in the figure, a database is first created using SQLite. This database is structured to store various types of information at each stage of the calculation. It includes columns for unique molecule identifiers, SMILES strings, molecular multiplicity, charge, and batch IDs for parallel calculations. The database is populated by pulling reactant SMILES and compound names from the input file. The compound is first processed by electronic_azo_conf_search.py (illustrated by the light blue outline).

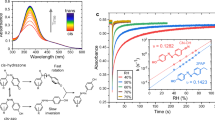

The initial step in the screening process is to identify the ground states of the reactant and the product for each azobenzene variation, along with their related energies. This yields the storage energy of each molecule. This task is performed by electronic_azo_conf_search.py, where the primary function is perform_ground_state_search. This section outlines the main concepts. The code is a revised version of earlier work50. It takes a molecule represented by a SMILES string and creates conformers for both the reactant and the product by rotating atoms around the bonds. Subsequently, GFN1-xTB48,64 is used to optimize each conformer then selecting the lowest-energy ones as ground states. The optimization aims to avoid local minima by using slightly different starting conditions for each geometry optimization. The energy difference between the reactant and the product is then calculated to obtain the storage energy. GFN1-xTB was chosen due to its computational efficiency in handling large-scale screening tasks. While GFN2-xTB offers improved accuracy, initial screenings with this method did not provide reliable results for the storage energies as seen in Fig. 4. The GFN2-xTB method gives unphysical negative storage energies and therefore we have not utilized the method. The ground state conformations are then processed by find_ts.py (shown as a light grey outline). Herein, The transition state connecting the parent and product isomers is determined by the reaction path method available in the xTB package63,65. The approach combines the capabilities of GFN1-xTB and meta-dynamics simulations to efficiently explore the reaction space, offering a computationally economical way to find the potential energy surface and find a transition state connecting the two input structures. We employed meta-dynamics simulations for reaction barrier calculations due to their efficiency in exploring complex free energy landscapes, particularly for reactions involving significant conformational flexibility, as seen in azobenzene derivatives. While transition state optimization algorithms like NEB and GSM are effective, they often require an accurate initial guess of the transition state, which can be challenging for complex molecular systems. Transition States of promising systems are further validated with vibrational frequency analysis to ensure a single imaginary frequency corresponding to the reaction coordinate. Additionally, IRC (Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate) calculations were conducted to confirm that the identified transition states indeed connect the reactants and products.

The ground state conformations are also transferred to find_max_abs.py, which runs an sTDA-xTB66 calculation to find the excitation energies and oscillator strengths, determining the maximum absorption wavelength by finding excitation energies up to 10 eV. The script then finds the highest oscillator strength and chooses the corresponding wavelength as the max absorption. Inside find_max_abs.py, the storage energy, back-reaction barrier, and the max absorption and oscillator strength for the reactant are then given to the script calc_sce.py (shown as a red outline), which calculates the solar conversion efficiency of the molecule according to Eq. (1). The final results will be added to the database as the calculations on the batch finish, with each molecule having conformers for the reactant, product, and transition state, along with the storage energy, thermal back-reaction barrier, and maximum absorption for both reactant and product, and the solar conversion efficiency. With the changed transition state search relative to the original procedure50, this xTB screening method is built to be applicable to any kind of molecule with the only change needed is the part where the product SMILES string is generated from the reactant SMILES string, which needs to be molecule-specific.

Using quantum mechanical methods inherently involves assessing reliability. While loosening constraints and thresholds could yield results more frequently, it would likely compromise quality. Generally, we consider the method effective, as it prioritizes speed and provides numerous initial results useful for selecting compounds for solar energy storage. However, we acknowledge that the approach is not entirely robust.

Chemical space selection

Azobenzene is a relatively simple molecule consisting of two phenyl rings connected by two double-bonded nitrogens. The photoisomerization of azobenzene involves a transition from a trans conformation to a less stable cis conformation. An illustration of the reaction can be seen in Fig. 2. The appeal of azobenzenes lies in their high cyclability, which means that they can be switched back and forth without degradation. However, azobenzene in its basic form does not meet the main requirements for solar range excitation, long storage life, or high storage capacity31. To overcome these limitations, substituents and other modifications have to be added to the base molecule. The ultimate aim is to create the means to establish a dataset of azobenzene variations, providing a broad molecular space for investigating potential substituents that meet the requirements.

To achieve a better solar match, substituents that redshift the excitation wavelengths are needed. Extending the conjugation in the molecules, especially through homoconjugation or push-pull systems, is a key approach. Push-pull systems are created by adding electron-donating groups (EDGs) and electron-withdrawing groups (EWGs)31. Examples include replacing a phenyl ring with benzothiophene (Homoconjugation) or adding a hydroxy group (EDG) or a halogen atom (EWG).

The reaction barrier must not be too high, or isomerization will not occur. Substituents that stabilize the otherwise unstable cis isomer can be added, such as a sulfur group on one side, which allows the cis isomer to adopt a T-shape structure in which the sulfur lone pairs interact with the phenyl ring67. London dispersion also aids in stabilizing the cis isomer68. Bulky substituents at the ortho positions of the phenyl rings can destabilize the transition state, interacting with the lone pairs of the nitrogens. Push–pull systems thus further benefit the reaction barrier.

To obtain high energy storage density, keeping the molecular weight low is crucial. Thus, it is preferable to keep the molecules relatively small. When substituents for azobenzene variations are chosen, it is vital to include types that extend conjugation, including homoconjugation and a variety of EWGs and EDGs, to create diverse push-pull systems. Exploration of larger, bulkier substituents near the double-bonded nitrogens is also of interest but generally smaller substituents are preferred to keep the molecular weight down31.

The theoretical challenges identified for the MOST systems based on azobenzene, such as the match of the solar spectrum, the extension of the energy storage time and the increase in the energy density, set the stage for the practical exploration of molecular variations. The strategic selection and placement of substituents, such as electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups, will be key to overcoming these challenges.

Initially, we explore the approach for generating a collection of azobenzene variations. First, we discuss the selection and positioning of substituents, examining the rationale behind choosing specific substituents and their placement on the base molecule. This includes considerations for forming particular structures like push-pull systems and strategically placing larger substituents to influence transition state stability. Figure 5 shows all substituents at the bottom. At the top is the basic azobenzene molecule with the 3 base variations shown in grey. Further specific details on placements and implementation can be seen in S.I.

Variations of the azobenzene molecule with annotations highlighting potential substitution sites are displayed. At the top in black is the basic azobenzene molecule, followed by three gray azobenzene base variations. The Half-Azobenzene variation is marked with a). Below the line, the substituents are grouped: R1 for ring substituents with potential substitutions marked by an asterisk (*) for sulfur (S), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), or carbon (C) atoms, R2 for steric blocking substituents, R3 for electron-withdrawing (EWG) and electron-donating (EDG) substituents, and R3’ for substituents exclusive to the basic azobenzene structure.

The strategy for substituent placement on the azobenzene core is instrumental in constructing a diverse molecular database. The variations outlined in Fig. 5 are:

-

Basic azobenzene The molecule is depicted in black, has an extensive range of substituents, specifically R3 and R3’ groups, to generate a diverse array of molecular variations.

-

Half-azobenzene with ring variation Marked with a) in gray, this structure permits the introduction of different hetrocyclic ring types, expanding the potential for structural diversity.

Substituents, organized into R groups as shown in Fig. 5, are selected for their electronic and structural properties to address the specific challenges posed by azobenzene-based MOST systems, including solar range excitation, energy storage longevity, and capacity. The detailed list of substituents is provided in the S.I and the R groups are:

-

R1: Electron-donating and withdrawing rings—Rings such as thiophene (EDR) and pyridine (EWR). They enhance conjugation and absorption, with applications in the half-azobenzene base molecule.

-

R2: Steric blocking substituents—this includes groups as tert-butyl and chloride that offer steric hindrance, which can influence the molecule’s transition state dynamics.

-

R3: General electron-withdrawing and donating substituents—Substituents in this group, including amino (EDG) and cyano (EWG) groups, are integral to creating push-pull systems for optimal absorption spectrum tuning.

-

R3’: Specific substituents for basic azobenzene—These are specially selected for the basic azobenzene structure to explore unique electronic effects and energy storage capabilities.

R3 and R3’ are located at the same substitution position in the azobenzene core

Generation of azobenzene variations

Having chosen a relevant subset of variations that are to be considered, the generation of diverse azobenzene variations is the next crucial step for the systematic investigation of the variations as MOST systems. In essence, the generation of input for the screening requires systematic generation of SMILES strings that actively removes duplicates due to symmetry. To that end, we developed a computational approach to construct and analyze SMILES strings for a multitude of azobenzene derivatives by methodically adding different substituents to the base molecule. This process was facilitated by custom-built functions designed for the automated and iterative addition of substituents, ensuring chemical validity and structural diversity.

The primary function, generate_molecules, was employed to assemble new molecules. It utilized an algorithmic approach to iteratively add substituents from a predefined list to specific sites on the azobenzene core. The function ensured that each new variation was chemically valid and unique, avoiding redundancy in the dataset.

An extension of this function, generate_and_print_molecules, provided enhanced control over the placement of substituents, allowing for the creation of targeted molecular structures, such as push-pull systems, which are vital for the energy storage capabilities of MOST systems. This function was instrumental in generating variations with precise substituent patterns.

To facilitate the generation of azobenzene variations, the MoleculeSet class was implemented, leveraging the features of Python’s set data structure to maintain a collection of distinct molecules. This approach utilized canonical SMILES representations to ensure that all molecules were unique, supporting the integrity of our molecular database.

For a detailed exposition of the computational procedures, algorithms, and code snippets utilized in the generation of azobenzene variations, the reader is referred to the S.I. Therein, we provide a comprehensive guide to the methods applied.

The variations in the azobenzene core are central to our study’s objective of designing an optimal molecular set for high-throughput screening. These modifications explore the impact of different substituent patterns on the electronic and steric properties of the azobenzene structure. To establish push–pull systems aligned with solar energy profiles, this variation incorporates a broad range of substituents, enabling diverse molecular architectures. The positioning of electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups is critical in modulating reaction barriers and energy storage potential. We have included a cyclopentadiene extension that enhances substituent versatility. By adding an additional benzene ring this modification extends the conjugation system, potentially improving the molecule’s photophysical properties. Classifying substituents based on electronic and structural characteristics is essential for addressing the challenges in azobenzene-based MOST systems: (1) Groups such as amide or cyano withdraw electron density, crucial for push–pull systems that redshift excitation wavelengths. (2) Groups like amino and hydroxy donate electron density, completing push–pull interactions. (3) Rings such as thiophene contribute electron density and extend conjugation for enhanced solar absorption. (4) Rings like pyridine allow for extended conjugation by withdrawing electron density. (5) Bulky groups such as methyl and iodine create steric barriers, influencing transition states and nitrogen lone pair interactions. Substituent placement on the azobenzene core provides a plentitude of options: (1) ortho, meta and para positions, (2) left and right positions and (3) ring substitution. Our combinatorial approach ensures systematic molecular generation while maintaining desired electronic and steric properties.

Numerical test results and discussion

The screening procedure was run on a total of 37729 azobenzene variations generated as described previously. Though all calculations successfully converged, many are removed as clear outliers due to unphysical results. Primarily due to the thermal back reaction barrier resulting in unlikely and unusual results. These are removed by filtering out results with barriers above 1000 kJ/mol and below 0 kJ/mol. This is expected as the \(\Delta E_{\text {TBR}}\) is entirely dependent on the transition state. A few systems were removed due to storage energies, as seen in Table 1. The unphysical results observed in our screening process primarily arose due to limitations in the conformational search algorithm, particularly in cases where molecules adopted unrealistic geometries that affected energy calculations. These issues were mitigated by applying additional convergence criteria and manually filtering structures with implausible bond lengths or angles.

This results in 18406 systems for testing. Of the remaining systems roughly 1/3 have a SCE of 0%, and the rest spanning up to the highest of 10.00%, seen in Fig. 6. The significant portion of systems with 0% is expected, and is due to either low absorption outside of the solar spectrum or a high \(\Delta E_{\text {TBR}}\) barrier preventing photoisomerization.

Histograms displaying the distribution of key parameters from the xTB screening of the 185 azobenzene variants in the 99th percentile of SCE. Green represents storage energy, determined through GFN1-xTB optimization. Purple indicates back reaction barriers obtained from reaction path searches. Orange shows the wavelength of the reactant maximum absorption (in nm), and blue depicts the energy density results.

Looking at the key parameters from the screen of the top 1% of the systems in Fig. 7, we see that compared to the total set (see S.I), there is a tendency for higher absorption wavelengths in the 400 nm range, as well as the higher energy densities being favored. While the Back-Reaction barrier and Storage energy tend towards values around 100 kJ/mol and 35 kJ/mol, respectively. Depicting that they are the most favourable values for a high SCE.

Optimized 3D Geometries and Hydrogen Bonds of the Azobenzene Variant with the Highest SCE. Shown from left to right are the trans (hydrogen bond distances: 1.7, 1.7, 2.4, 2.4 Å), transition-state (2.2, 2.3, 2.4, 2.7 Å), and cis (2.0, 2.1, 3.1, 3.1 Å) geometries. The atomic color scheme is Carbon (green), Oxygen (red), Nitrogen (blue), and Hydrogen (white).

We note that the best system (see Fig. 7, Table 2) , when evaluated based on it’s solar conversion efficiency limit, features a quite red-shifted absorption of 470.9 nm which will have a significant overlap with the solar spectrum. We refer large separation between the reactant and product absorption to the spectral shift between the trans and cis isomers, of approximately 100 nm, which determines the efficiency of photoconversion. A significant spectral shift greatly reduces the spectral overlap and allows selective excitation of the trans isomer without simultaneously exciting the cis form, improving the photoconversion yield. This is due to the red shifting of transitions and the significant shift of the \(n\pi *\) transition during the trans to cis isomerisation69,70. On the other hand, the storage energy and the estimated thermal back reaction barrier are relatively low. This indicates that the system is not able to store a significant amount of energy and it is also questionable whether the thermal stability of the product is sufficient to actually facilitate storage at ambient temperatures. Furthermore, we note that the differences in hydrogen bonding for the trans and cis conformers provide higher storage energies. Concerning the role of hydrogen bonding in influencing storage energy, we have in Fig. 8 included a three-dimensional molecular structure that highlights the hydrogen bonding interactions in both trans and cis conformers. Generally, we observed how these interactions contribute to stabilization and energy storage potential

We acknowledge that the molecule with the highest SCE may not be ideal in all aspects. Therefore, we have expanded our analysis to include additional molecules with high SCE rankings. By comparing their thermal stability and energy storage potential, we identify alternatives that may offer a better balance of performance criteria. Rigorous DFT calculations can further validate the performance of the optimal molecules. To this end, we have conducted additional DFT calculations for selected molecules in Table 2 to verify key properties, including storage energy and transition state stability.

In our analysis of structure–property relationships, we have conducted a detailed examination of the top 30 compounds exhibiting the highest solar conversion factors. Our findings underscore the critical role of substituents on the molecular rings in determining energy storage performance. A clear trend emerges when comparing the most effective compounds: the presence and nature of specific functional groups significantly influence their solar energy conversion efficiency. Among the various substituents observed, the hydroxyl (OH) group stands out as the most dominant, appearing frequently in the top-performing compounds. This suggests that the strong hydrogen bonding capability and electron-donating nature of the hydroxyl group contribute positively to solar energy conversion efficiency. Following the hydroxyl group, the amine (NH\(_2\)) substituent also plays a significant role. As an electron-donating group, NH\(_2\) enhances the electronic interactions within the molecule. The carbonyl (C=O) functional group ranks third in terms of prevalence among the high-performing compounds. Unlike OH and NH\(_2\), the C=O group is an electron-withdrawing moiety, which can modulate the electronic structure by influencing charge separation. Overall, our findings highlight that careful selection and strategic placement of substituents on the molecular framework can substantially enhance solar conversion efficiency. Future molecular design strategies should prioritize these key functional groups to optimize photovoltaic performance.

The objective of this test set was to challenge the limits of the screening procedure and identify whether it can handle various azobenzene types successfully. The outcome was promising: Many systems yielding promising results were found, reducing the space for which one should examine with higher level methods such as DFT. Our findings also highlight that identifying the transition state remains a critical challenge in obtaining reliable results.

Conclusion

We have established a framework designed for computational screening of unique azobenzene variations for MOST applications using xTB methods. The flexibility of the framework is evident in its capability to treat different substituent placements, substituent types, bonding mechanisms to the base molecule, and even modifications to the base molecule itself. Such versatility ensures that the procedure is primed for further expansion and diversification in subsequent research phases. The foundational elements for the screening process have been organized and made accessible via a GitHub repository (https://github.com/BerlinObel/xTB). This ensures transparency, reproducibility, and ease of access for future researchers. Furthermore, the framework is readily adaptable to other photoswitch motifs making the established methodology generalizable in the context of MOST technology and potentially also other applications.

Our study highlights the pivotal role of molecular substituents in determining the solar conversion efficiency of organic compounds. Through a detailed analysis of the top 30 high-performing molecules, we have identified hydroxyl (OH), amine (NH\(_2\)), and carbonyl (C=O) groups as key functional moieties that influence photovoltaic performance. The dominant presence of the OH group, followed by NH\(_2\) and C=O, underscores their impact on charge transfer, electronic interactions, and molecular orbital alignment. These findings emphasize the importance of strategic molecular design in optimizing solar energy conversion. By carefully selecting and positioning functional groups, researchers can enhance the efficiency of photovoltaic materials and improve their overall performance. Future efforts in material design should focus on leveraging these insights to develop next-generation solar energy materials with superior optoelectronic properties.

The computational methodologies employed, including GFN1-xTB for optimization and conformer searches, sTDA-xTB for excitation energy calculations, and a hybrid meta-dynamics and xTB approach for locating transition states, have proven effective on a test set of 37729 different azobenzene derivatives. From the test set, we identify systems with solar conversion efficiencies reaching 10.0%. However, a critical aspect that warrants further exploration is the correlation of the results obtained using the screening procedure and higher level calculations based on e.g. DFT. We will seek to address this point in future studies where we will also utilize the developed methodology to screen a large set of azobenzene derivatives as potential MOST systems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. (eds) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Bowers, R., Fasching, E. & Antonio, K. As Solar Capacity Grows, Duck Curves are Getting Deeper in California, U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Service R. F. Is it time to shoot for the. Science 309, 548–551 (2005).

Lewis, N. S. & Nocera, D. G. Powering the planet: Chemical challenges in solar energy utilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103, 15729–15735 (2006).

Kucharski, T. J., Tian, Y., Akbulatov, S. & Boulatov, R. Chemical solutions for the closed-cycle storage of solar energy. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 4449–4472 (2011).

Moth-Poulsen, K. et al. Molecular solar thermal (MOST) energy storage and release system. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 8534–8537 (2012).

Lennartson, A., Roffey, A. & Moth-Poulsen, K. Designing photoswitches for molecular solar thermal energy storage. Tetrahedron Lett. 56, 1457–1465 (2015).

Wang, Z. et al. Demonstration of an azobenzene derivative based solar thermal energy storage system. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 15042–15047 (2019).

Kucharski, T. J. et al. Templated assembly of photoswitches significantly increases the energy-storage capacity of solar thermal fuels. Nat. Chem. 6, 441–447 (2014).

Yoshida, Z.-I. New molecular energy storage systems. J. Photochem. 29, 27–40 (1985).

Dreos, A. et al. Exploring the potential of a hybrid device combining solar water heating and molecular solar thermal energy storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 728–734 (2017).

Quant, M. et al. Low molecular weight norbornadiene derivatives for molecular solar-thermal energy storage. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 13265 (2016).

Boye, I., Hansen, M. H. & Mikkelsen, K. V. The influence of nanoparticles on the polarizabilities and hyperpolarizabilities of photochromic molecules. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 23320–23327 (2018).

Luchs, T., Lorenz, P. & Hirsch, A. Efficient cyclization of the norbornadiene-quadricyclane interconversion mediated by a magnetic [Fe3O4- CoSalphen] nanoparticle catalyst. ChemPhotoChem 4, 52–58 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Macroscopic heat release in a molecular solar thermal energy storage system. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 187–193 (2019).

Bertram, M. et al. Norbornadiene photoswitches anchored to well-defined oxide surfaces: From ultrahigh vacuum into the liquid and the electrochemical environment. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 044708 (2020).

Ree, N. & Mikkelsen, K. V. Benchmark study on the optical and thermochemical properties of the norbornadiene-quadricyclane photoswitch. Chem. Phys. Lett. 779, 138665 (2021).

Brøndsted Nielsen, M., Ree, N., Mikkelsen, K. V. & Cacciarini, M. Tuning the dihydroazulene–vinylheptafulvene couple for storage of solar energy. Russ. Chem. Rev. 89, 573–586 (2020).

Durgun, E. & Grossman, J. C. Photoswitchable molecular rings for solar-thermal energy storage. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 854–860 (2013).

Alex, W. et al. Solar energy storage: Competition between delocalized charge transfer and localized excited states in the norbornadiene to quadricyclane photoisomerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 153–162 (2022).

Pandey, A. et al. Novel approaches and recent developments on potential applications of phase change materials in solar energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 82, 281–323 (2018).

Gur, I., Sawyer, K. & Prasher, R. Searching for a better thermal battery. Science 335, 1454–1455 (2012).

Liu, M., Saman, W. & Bruno, F. Review on storage materials and thermal performance enhancement techniques for high temperature phase change thermal storage systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16, 2118–2132 (2012).

Yan, T., Wang, R., Li, T., Wang, L. & Fred, I. T. A review of promising candidate reactions for chemical heat storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 43, 13–31 (2015).

Gurke, J., Quick, M., Ernsting, N. P. & Hecht, S. Acid-catalysed thermal cycloreversion of a diarylethene: A potential way for triggered release of stored light energy? Chem. Commun. 53, 2150–2153 (2017).

Brummel, O. et al. Photochemical energy storage and electrochemically triggered energy release in the norbornadiene-quadricyclane system: UV photochemistry and IR spectroelectrochemistry in a combined experiment. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 2819–2825 (2017).

Dong, L. et al. Azobenzene-based solar thermal energy storage enhanced by gold nanoparticles for rapid, optically-triggered heat release at room temperature. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 18668–18676 (2020).

Yang, W. et al. Efficient cycling utilization of solar-thermal energy for thermochromic displays with controllable heat output. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 97–106 (2019).

Calbo, J. et al. Tuning azoheteroarene photoswitch performance through heteroaryl design. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1261–1274 (2017).

Kolpak, A. M. & Grossman, J. C. Hybrid chromophore/template nanostructures: A customizable platform material for solar energy storage and conversion. J. Chem. Phys. 138, 034303 (2013).

Wang, Z. et al. Storing energy with molecular photoisomers. Joule 5, 3116–3136 (2021).

Wang, Z., Hölzel, H. & Moth-Poulsen, K. Status and challenges for molecular solar thermal energy storage system based devices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 7313–7326 (2022).

Crespi, S., Simeth, N. A. & König, B. Heteroaryl azo dyes as molecular photoswitches. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 133–146 (2019).

Eisenreich, F. et al. A photoswitchable catalyst system for remote-controlled (co) polymerization in situ. Nat. Catal. 1, 516–522 (2018).

Dorel, R. & Feringa, B. L. Photoswitchable catalysis based on the isomerisation of double bonds. Chem. Commun. 55, 6477–6486 (2019).

Neilson, B. M. & Bielawski, C. W. Illuminating photoswitchable catalysis. ACS Catal. 3, 1874–1885 (2013).

Fuchter, M. J. On the promise of photopharmacology using photoswitches: A medicinal chemist’s perspective. J. Med. Chem. 63, 11436–11447 (2020).

Corra, S. et al. Kinetic and energetic insights into the dissipative non-equilibrium operation of an autonomous light-powered supramolecular pump. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 746–751 (2022).

Han, M. et al. Light-controlled interconversion between a self-assembled triangle and a rhombicuboctahedral sphere. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 445–449 (2016).

Lee, H. et al. Light-powered dissipative assembly of diazocine coordination cages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 3099–3105 (2022).

Kolpak, A. M. & Grossman, J. C. Azobenzene-functionalized carbon nanotubes as high-energy density solar thermal fuels. Nano Lett. 11, 3156–3162 (2011).

Beharry, A. A. & Woolley, G. A. Azobenzene photoswitches for biomolecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 4422–4437 (2011).

Zhang, B., Feng, Y. & Feng, W. Azobenzene-based solar thermal fuels: A review. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 138 (2022).

Bandara, H. M. D. & Burdette, S. C. Photoisomerization in different classes of azobenzene. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 1809–1825 (2012).

Song, T. et al. Supramolecular cation interaction enhances molecular solar thermal fuel. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 1940–1949 (2022).

Börjesson, K., Lennartson, A. & Moth-Poulsen, K. Efficiency, limit of molecular solar thermal energy collecting devices. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 1, 585–590 (2013).

Kuisma, M., Lundin, A., Moth-Poulsen, K., Hyldgaard, P. & Erhart, P. Optimization of norbornadiene compounds for solar thermal storage by first-principles calculations. Chem. SusChem 9, 1786–1794 (2016).

Grimme, S., Bannwarth, C. & Shushkov, P. A robust and accurate tight-binding quantum chemical method for structures, vibrational frequencies, and noncovalent interactions of large molecular systems parametrized for all spd-block elements (Z = 1–86). J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13, 1989–2009 (2017).

Reimann, M., Teichmann, E., Hecht, S. & Kaupp, M. Solving the azobenzene entropy puzzle: Direct evidence for multi-state reactivity. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13, 10882–10888 (2022).

Elholm, L., Hillers-Bendtsen, J. E., Hölzel, A., Moth-Poulsen, H. & Mikkelsen, K. V. K. High throughput screening of norbornadiene/quadricyclane derivates for molecular solar thermal energy storage. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 28956–28964 (2022).

Wang, K. et al. 12 3811–3837 (The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2024).

Kunz, S. et al. Unraveling the electrochemistry of verdazyl species in acidic electrolytes for the application in redox flow batteries. Chem. Mater. 34, 10424–10434 (2022).

Hillers-Bendtsen, A. E. et al. Searching the chemical space of bicyclic dienes for molecular solar thermal energy storage candidates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, 543 (2023).

Zhang, Z.-Y. et al. Photochemical phase transitions enable coharvesting of photon energy and ambient heat for energetic molecular solar thermal batteries that upgrade thermal energy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 12256–12264 (2020).

Xu, A. et al. Carbon-based quantum dots with solid-state photoluminescent: Mechanism, implementation, and application. Small 16, 2004621 (2020).

Nishimura, N. et al. Thermal cis-to-trans isomerization of substituted azobenzenes II. Substituent and solvent effects. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 49, 1381–1387 (1976).

Nishioka, H., Liang, X. & Asanuma, H. Effect of the ortho modification of azobenzene on the photoregulatory efficiency of DNA hybridization and the thermal stability of its cis form. Chemistry 16, 2054–2062 (2010).

He, Y. et al. Azobispyrazole family as photoswitches combining (near-) quantitative bidirectional isomerization and widely tunable thermal half-lives from hours to years. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 16539–16546 (2021).

Slavov, C. et al. Thiophenylazobenzene: An alternative photoisomerization controlled by lone-pair interaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 380–387 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Shedding new lights Into STED microscopy: Emerging nanoprobes for imaging. Front. Chem. 9, 641330 (2021).

Koerstz, M. QMC, Original-Date: 2019-01-16T08:12:07Z (2019).

Landrum, G. et al. Jasondbiggs; Strets123; JP rdkit/rdkit: 2022 09 5 (Q3 2022) Release (2023).

Semiempirical Extended Tight-Binding Program Package, Original-Date: 2019-09-30T12:40:09Z (2023).

Bannwarth, C. et al. Extended tight-binding quantum chemistry methods. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 11, e1493 (2021).

Grimme, S. Exploration of chemical compound, conformer, and reaction space with meta- dynamics simulations based on tight-binding quantum chemical calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 2847–2862 (2019).

Grimme, S. & Bannwarth, C. Ultra-fast computation of electronic spectra for large systems by tight-binding based simplified Tamm-Dancoff approximation (sTDA-xTB). J. Chem. Phys. 145, 054103 (2016).

Heindl, A. H. & Wegner, H. A. Rational design of azothiophenes—Substitution effects on the switching properties. Chem. Eur. J. 26, 13730–13737 (2020).

Di Berardino, C., Strauss, M. A., Schatz, D. & Wegner, H. A. An incremental system to predict the effect of different London dispersion donors in all-meta-substituted azobenzenes. Chem. Eur. J. 28, e202104284 (2022).

Birnbaum, P., Linford, J. & Style, D. The absorption spectra of azobenzene and some derivatives. Trans. Faraday Soc. 49, 735–744 (1953).

Pederzoli, M., Pittner, J., Barbatti, M. & Lischka, H. Nonadiabatic molecular dynamics study of the cis-trans photoisomerization of azobenzene excited to the S1 state. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 11136–11143 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF-0136-00081B) for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S.: Investigation; Writing-Original Draft. O.B.O.: Investigation, Writing-Review and Editing. A.E.H.-B.: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing-Review and Editing. K.V.M.: Supervision, Resources; Conceptualization; Writing-Review and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schjelde, K., Obel, O.B., Hillers-Bendtsen, A.E. et al. Semi-automated screening of azobezenes for solar energy storage using extended tight binding methods. Sci Rep 15, 20750 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99925-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99925-6