Abstract

In-silico and in-vivo methods were used to study Ficus exasperata leaves’ n-hexane ethyl acetate fraction (NHEAF) phytochemicals that may protect against NaNO2-induced hypoxic stress. The impact of NHEAF on enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants, total ATPase, malondialdehyde, and the relative expression of human inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), nuclear respiratory factor-2, and nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-kB) were investigated, along with the docking of NHEAF phytochemicals to HIF-1 and NF-κB. Thirty female Wistar rats were divided into groups A, B, C, D, E and F (n = 5). Groups A and B were pretreated with olive oil (vehicle). While group C, D, E, and F were pretreated with standard drug (C = Vitamin E 100 mg/ kg bwt and Omega-3 essential fatty acid (72 mg Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) + 48 mg Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)/ kg bwt), 30 mg/ kg bwt NHEAF (D) and 60 mg/ kg bwt NHEAF (E and F respectively) for 14 days followed by oral administration of NaNO2 (80 mg/kg bwt) to groups B, C, D, and E. One of the eight NHEAF phytochemicals with the highest percentage total quantity is Cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl- (3β). Unlike group B, groups D and E pretreated with NHEAF were protected from the impairment of antioxidant defence and elevation of HIF-1 and NF-κB caused by NaNO2 intoxication. Cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl- (3β), has the highest binding affinity for HIF-1 (ΔG = -8.6 kcal/mol) and NF-κB (ΔG = -7.6 kcal/mol) proteins among the NHEAF phytochemicals. Cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3β) may contribute to NHEAF’s protection against s NaNO2-induced hypoxic stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past decades, there has been a growing concern regarding the shift in dynamics of the food system and the accelerated global transition towards nutritionally transformative preserved and packaged foods1. This prevailing trend has heightened consumption of low-level chemicals and additives beyond safety level, with sodium nitrite standing out as a noteworthy substance1,2,3. Sodium nitrite (NaNO2) is widely used in the food industry as color fixative and preservative of fish and meat products where it acts as a flavour-enhancer, bacteriostatic and rancidity retardation1,4,5. Sodium nitrite is crucial as a curing agent for preserving the quality of food items, as it plays a key role in stabilizing the heme iron present in the pigments of meat3,5,6,7,8. Additionally, it functions as an antifreeze agent, preventing corrosion in pipes and tanks, thus accounting for its presence in trace amounts in drinking water1,6,7,8. Thus, sodium nitrite is ranked among the most utilized additives in the production of different kind of food items, like canned vegetables, burgers, sardines, cheese, and sausages2,5,6.

Sodium nitrite chemically or enzymatically transformation leads to formation of nitric oxide, it then reacts with hemoglobin to produce methaemoglobin2,5,6,7,8. Nitrite in food can react with amines in the stomach to produce carcinogenic nitrosamine leading to excessive free radical generation, which cause an imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants1,3,5. Growing evidence support the notion that gradual buildup of nitric oxide (NO) generated from nitrite, whether intra or extracellularly, can result in cytotoxicity, which in turn can lead to structural and functional damage in multiple organs5,6,8. Excessive exposure to sodium nitrite has also been documented to cause mismatch between oxygen supply and its demand at the cellular level which is also associated with an increase in the production of reactive species (RS)5,7,8,9. Sodium nitrite toxicity has been reported to induce impairment of the cellular enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems which decrease the antioxidant power, compromising the ability of the cell to defend against oxidative damage3,5,6. The impeded oxidative stress cause dysregulation of inflammatory responses, tissue injury and hampers anti-tumor cytotoxic effector cell types7,8.

Researchers have increasingly focused on exploring natural remedies to address oxidative stress, inflammation and cytotoxicity, considering that pharmaceutical interventions can occasionally lead to side effects1,3,5,8,10,11. Ficus exasperata (Moraceae) is a very widespread plant species throughout inter-tropical Africa and highly rich in chemical constituents with antioxidant potentials12,13. Ficus exasperata has been utilized in treating a wide range of diseases, with various parts of the plant such as leaves, stem, bark roots, flowers, and seeds being exploited in different forms12,13. Various phytochemical constituents have been reported in Ficus exasperata leaf to be responsible for the usage of the leaf in traditional medicine. These phytochemicals include alkaloids, saponins, tannins, flavonoids, cardiac glycoside, steroid, reducing agent, and phenols12,13,14,15. Previous scientific evidence reveals that bioactive component in Ficus exasperata leaves make the leaves to exhibit radical scavenging activity, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, management of impotence and infertility12,13,14,15,16.

Reactive species produced from sodium nitrite exposure react with hemoglobin, minimizing its oxygen-carrying capacity by generating methemoglobin5,8. The accumulation of methemoglobin disrupts oxygen transport leading to methemoglobinemia concurrently inducing systemic tissue hypoxia7,9. Systemic tissue hypoxia triggers a series of gene expression changes, affecting angiogenesis, cellular metabolism coupled with over-expression of human inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) and nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB)7,9,17. Thus, it is crucial to explore natural interventions that can effectively attenuate, mitigate or prevent the damaging effects of sodium nitrite intoxication1,5,8. Previous researchers have reported that extraction or fractionation of any medicinal plant part with a hexane: ethyl acetate mixture (85:15 [v/v]) yields an extract or fraction rich in various terpenes (terpenoids) with significant medicinal properties16,18. Herein, this study hypothesised that one of the Ficus exasperata leaves n-hexane ethyl acetate fraction (NHEAF) phytochemicals could be responsible for protecting against sodium nitrite-induced hypoxic stress by modulating and binding to human inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) and nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) relative expression levels. NHEAF effects on primary antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx)), secondary antioxidant enzymes (glutathione reductase (GR), and gamma-glutamyl cysteine ligase (γ-GCL)), total ATPase, malondialdehyde (MDA), non-enzymic antioxidant (vitamin E, vitamin C, reduced glutathione (GSH), total thiol (TSH)), relative expressions of HIF-1, nuclear respiratory factor-2 (Nrf-2) and NF-κB in conjunction with NHEAF phytochemicals docking against HIF-1 and NF-κB were the specific objectives of this study.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

All chemicals used were of analytical grade and were obtained from Sigma- Aldrich Chemical and Merck companies (Missouri, USA). The standard drug used (100 mg Vitamin E and Omega-3 essential fatty acid (72 mg Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) + 48 mg Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)) Omega-3) was a product of Nature’s field (Bactolac pharmaceutical INC, Hauppauge, NY 11788, USA).

Preparation of Ficus exasperata N-hexane ethyl acetate fraction (NHEAF)

After being granted permission and clearance by the University, fresh leaves of Ficus exasperata were collected from the Botanical Garden of the Department of Pure and Applied Botany, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria, by a Forester (Mr. E.A. Fatunbi). The leaves were identified and authenticated with herbarium number FUNAABH0039 by Botanist/Plant Taxonomist (Prof. D.A. Agboola and Dr. A. S. Oyelakin) of the Department of Pure and Applied Botany, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria. Voucher specimens of the plant with its herbarium number are deposited in the University’s public herbarium.

The leaves were washed, air-dried to constant weight, and milled using a mechanical grinder. To 100 g of milled sample, 500 ml of 85:15 (v/v) n-hexane: ethyl acetate was used for the extraction with the aid of a Soxhlet extractor for 24 h. Then, the filtrate was concentrated using a Rotary evaporator at 60 ℃ to get the crude extract16. The crude extract was fractionated into fractions on a silica gel-packed column. A non-polar solvent (N-hexane) was used to elute the first fraction of the extract. Then, semi-polar (85% n-hexane + 15% ethyl acetate) solvent was added drop wisely to elute the second fraction (FR2), which was further concentrated and used for the study.

NHEAF phytochemical compounds identification using gas chromatography‑mass spectrometry (GC‑MS) analysis

The GC-MS analysis of NHEAF was carried out by following the method described by Alhassan et al.11. Identification of components was assigned by matching their mass spectra with WILEY Registry of Mass Spectral Data 7th edition (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) and National Institute of Standards and Technology 05 MS (NIST) GC-MS libraries data.

Experimental animal and ethical approvals

Prior to the commencement of the experiment with ethical no. FUNAAB-BCH- DI A022: The Departmental Animal Ethical Committee (FUNAAB-BCH) has given its clearance. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the authorised protocols and standards guidelines for animal research, as outlined in the Animal Research: Reporting in Live Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines, under the strict supervision of the Departmental Animal Ethical Committee (FUNAAB-BCH), in line with the FUNAAB-BCH recommended guidelines and regulations.

Fifty female Wistar rats weighing between the ranges of 65–100 g were purchased from the Department of Physiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta (FUNAAB), Nigeria. The animals were acclimatized for four weeks before proper experiment. The animals were housed in plastic cages with good ventilation and were supplied with standard animal feed pellet and clean water ad libitum in the animal care unit of the Department of Biochemistry, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta (FUNAAB), Nigeria.

Sodium nitrite-induced intoxication pilot study

The toxicity studies using single dose of sodium nitrite as a toxicant against female rats are scanty. Following the report of Imaizumi et al.2 and that of El-Nabarawy et al.6, a pilot study was carried out to ascertain the dose of nitrite that would induce toxicity and not cause mortality in female rats (dose that will provide toxicity without lethality). This study was divided into three stages, with each stage determining the next step to take (whether to terminate or proceed to the next stage). Three rats were used for each stage, and they received 60, 75 and 80 mg/kg bwt (body weight) each per stage. All animals were observed continuously for four hours, then twenty-four and forty-eight hours for any changes and the number of survivors was noted. At the end of the third stage (final stage), when no sign of death was observed, it was concluded that 80 mg. kg− 1 body weight of sodium nitrite single dose will be used.

Experimental design

After four weeks of acclimatization, thirty (30) female Wistar rats were divided into six groups (A, B, C, D, E, and F) of 5 rats per group. Group A (control) and B (NaNO2 (negative control)) were pretreated with the vehicle (olive oil) used to dissolve the standard drug and NHEAF. While group C, D, E, and F were pretreated with standard drug (C = Vitamin E 100 mg/kg bwt and Omega-3 essential fatty acid (72 mg Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) + 48 mg Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)/kg bwt), 30 mg/kg bwt NHEAF (D) and 60 mg/kg bwt NHEAF (E and F respectively) for 14 days. On the14th day after an hour of the last respective pretreatment, groups B, C, D, and E were orally administered 80 mg/kg bwt NaNO2 while group A and F were administered distilled water. On the 15th day, blood was collected from these animals periorbitally (orbital venous plexus bleeding) under light anaesthesia (ketamine and xylazine at 60 and 6 mg/kg bwt. respectively) into clean plain tubes. Occurrence of rapid sedation (after 3 min of anaesthesia injection, each rat was unconscious), good analgesia, and suitable anaesthetic depth showing mild/moderate nociceptive stimulation in the rats. At the time of dissection, all the rats showed a deep anaesthetic sign with no response to skin incision. All the animals were dissected to excise the liver and the kidney for biochemical analyses. The remaining tissues (liver and kidney) were harvested for immunohistochemical analysis and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution.

Biochemical analysis and immuno‑histochemistry

The activity of super oxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), catalase (CAT), gamma-glutamyl cysteine ligase (γ- GCL), glutathione reductase (GR), and Total ATPase were assayed according to the method of Marklund and Marklund19, Bauché et al.20, Hadwan and Abed21, De Donatis et al.22, Bauché et al.20, and Tsakiris and Deliconstantino’s23 respectively. The concentration of reduced glutathione (GSH), total thiols, malondialdehyde (MDA), vitamins C and E were estimated according to method described by Bauché et al.20, Sedlak and Lindsay24, Jafari et al.26, Jagota and Dani26 and Jafari et al.25 respectively. Immune-histochemical studies on the liver and kidney samples for relative expressions of HIF-1, Nrf-2 and NF-κB were carried out at the Institute for Advanced Medical Research and Training (IMRAT), Nigeria as described by the standard protocol of immune-histochemistry of any protein relative expression6,10.

Molecular docking

For further validation of the hypothesizes that one of the Ficus exasperata leaves n-hexane ethyl acetate fraction (NHEAF) phytochemicals could aid protection against sodium nitrite induced-hypoxic stress by modulating relative expressions of human inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), and nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), all the identified phytochemical compounds from NHEAF using GCMS analysis were subjected to molecular docking analysis with HIF-1 and NF-κB protein targets. The three-dimensional (3D) structures for the target proteins, HIF-1α (Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1α, PDB ID: 3KCY) and NF-κB (Nuclear Factor kappa B, PDB ID: 1A3Q), were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB, www.rcsb.org). Protein preparation was performed using UCSF Chimera 1.1227. This involved removing co-crystallized ligands and water molecules, adding polar hydrogen atoms, and performing energy minimization on the protein structures. All the identified phytochemical compounds structures (ligands) from NHEAF were obtained in 3D Structure Data File (SDF) format from the PubChem database.

Molecular docking simulations were conducted using AutoDock Vina, accessed via the PyRx virtual screening tool28, to predict the binding affinities of the ligands to the prepared HIF-1α and NF-κB targets. The search space (grid box) for docking was defined for each target. For HIF-1α (PDB: 3KCY), the grid box was centered at coordinates (x = −21.675, y = 26.943, z = 8.189) with dimensions of 56.1 Å x 65.6 Å x 54.6 Å (size_x, size_y, size_z). For NF-κB (PDB: 1A3Q), the grid box was centered at (x = 9.057, y = 61.487, z = 19.615) with dimensions of 56.2 Å x 88.0 Å x 48.4 Å (size_x, size_y, size_z). An exhaustiveness parameter of 8 was used for all docking runs. Resulting protein-ligand interactions were subsequently visualized and analyzed using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer 2020.”

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) was utilised to analyse all generated data, interpreted as mean ± S.E.M (standard error of the mean). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to assess the homogeneity level among the groups, with means being separated through the Duncan multiple range test (DMRT) at p < 0.05. The quantitative evaluation and automated scoring of immunohistochemistry images were conducted using the open-source digital image analysis software Image J, as Varghese et al.29 described.

Results

GC-MS analysis identified phytochemicals compounds in NHEAF

The total ion chromatogram (TIC) of NHEAF revealed the GC-MS profile of the compounds identified as presented in Fig. 1. The peaks in the chromatogram were integrated and compared with the database of spectrum of known components stored in the NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) library. Table 1 shows the names of phytochemical compounds in the NHEAF gotten from twenty-eight peaks. The identified named compounds are Phenol, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-; 3-Tridecene, (Z)-; Tridecane, 3-methyl- (Tridecane, 2-methyl-); 1-Iodo-2-methylnonane; Naphthalene, 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-2,6-dimet; 3-Tetradecene, (E)-; Decane, 1-iodo-; Cetene; Pentadecane, 2-methyl-; Heptadecane, 2-methyl-; 1-Pentadecene; Cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3.beta; n-Tetracosanol-1; Tetracontane, 3,5,24-trimethyl-; Tetracosane, 1-bromo-; Fumaric acid, 8-chlorooctyl tridecyl ester; Bis(tridecyl) phthalate; n-Tetracosanol-1; Heneicosane; Tetratetracontane; Sulfurous acid, octadecyl 2-propyl ester; 2-methyltetracosane and Triacontane, 11,20-didecyl-. Additionally, the GC-MS analysis revealed eight compounds with high percentage total quantities which are 3-Tridecene, (Z)- (5.02%); Naphthalene, 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-2,6-dimet (5.18%); 3-Tetradecene, (E)- (15.39%); Cetene (14.54%); 1-Pentadecene (10.36%); Cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3.beta (5.42%); n-Tetracosanol-1 (7.25%); and Sulfurous acid, octadecyl 2-propyl ester (5.34%).

Effects of NHEAF on primary antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT and GPx)

Decrease in all tissue (serum, liver and kidney) SOD specific activity ensued single dose oral administration of NaNO2 (group B) was prevented with pretreatment with standard drug (group C) and different doses of NHEAF (group D and E). No significant (p < 0.05) different was observed among groups A, C, E, and F in serum SOD specific activity. While kidney and liver SOD specific activity revealed no significant (p < 0.05) different between group A and C (see Fig. 2).

All rats pretreated with standard drug (group C) and different doses of NHEAF (group D and E) were able to protect again decrease in serum, liver and kidney CAT specific activity (see Fig. 3) induced by single dose oral administration of NaNO2 (group B) when compared with group A (control). There were no significant (p < 0.05) different among groups A, C, D, E, and F in serum and liver CAT specific activity while kidney group F showed significant different when compared with groups A, C, D, and E. but not as low in CAT activity when compared with group B.

Specific activity of GPx in serum, liver and kidney revealed no significant different (p < 0.05) among all pretreatment groups (C, D, E and F) when compared with group A with the exception of kidney group C. Oral administration of single dose of NaNO2 caused a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in serum, liver and kidney GPx specific activity in the rats when juxtaposed with group A as shown in Fig. 4.

Effects of NHEAF on secondary antioxidant enzymes (GR, and γ-GCL), and total ATPase

Pretreatment with standard (group C) and different doses of NHEAF (group D and E) were able to prevent significant (p < 0.05) decrease in serum, liver and kidney GR specific activity ensuing oral administration of single dose of NaNO2 when juxtaposed with group A as shown in Fig. 5. Specific activity of GR in serum, liver and kidney revealed no significant different (p < 0.05) among all pretreatment groups (C, D, E and F) when compared with group A. The pretreatment effects of NHEAF on liver GR specific activity was in dose dependent manner (Fig. 5).

Specific activity of γ-GCL in serum, liver and kidney revealed no significant different (p < 0.05) among all pretreatment groups (C, D, E and F) when compared with group A with the exception of serum group C and liver group C and F. Oral administration of single dose of NaNO2 caused a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in serum, liver and kidney γ-GCL specific activity in the rats when juxtaposed with group A as shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 7 depicts how pretreatment with standard (group C) and different doses of NHEAF (group D and E) were able to prevent significant (p < 0.05) NaNO2 single dose induced increase in serum, with concomitant decrease in liver and kidney total ATPase specific activity when compared with group A. There were no significant different (p < 0.05) among all pretreatment groups (C, D, E and F) when compared with group A with the exception of serum group D. The pretreatment effects of NHEAF on serum total ATPase specific activity was in dose dependent manner.

Effects of NHEAF on malondialdehyde (MDA) and non-enzymic antioxidant (GSH, total thiols, vitamins C and E) levels

Figure 8 is showing how pretreatment with standard (group C) and different doses of NHEAF (group D and E) were able to prevent significant (p < 0.05) NaNO2 single dose induced increase in serum, liver and kidney MDA levels when compared with group A. The pretreatment effects of NHEAF on serum and kidney MDA levels were in dose dependent manner.

Figure 9 depicts how pretreatment with standard (group C) and different doses of NHEAF (group D and E) were able to prevent significant (p < 0.05) NaNO2 single dose induced decrease in serum, liver and kidney GSH levels when compared with group A. There were no significant different (p < 0.05) among all pretreatment groups (C, D, E and F) with the exception of liver group D when compared with group A. The pretreatment effects of NHEAF on liver GSH levels was in dose dependent manner.

Decrease in serum, liver and kidney TSH levels ensued single dose oral administration of NaNO2 (group B) was prevented with pretreatment with standard drug (group C) and different doses of NHEAF (group D and E). The pretreatment effects of NHEAF on serum, liver and kidney total thiol levels were in dose dependent manner. No significant (p < 0.05) different was observed between groups A, E and F in serum total thiol concentrations. While kidney and liver TSH levels revealed no significant (p < 0.05) different between group A and F (see Fig. 10).

All rats pretreated with standard drug (group C) and different doses of NHEAF (group D and E) were able to protect again decrease in serum, liver and kidney (see Figs. 11 and 12) induced by single dose oral administration of NaNO2 (group B) when compared with group A (control). There were no significant (p < 0.05) different among groups A, C, D, E, and F in serum, liver and kidney vitamin E and C levels with the exception of group F serum vitamin E when compared with groups A.

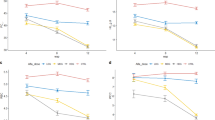

Effects of NHEAF on relative expressions of HIF-1, Nrf-2 and NF-κB

Figure 13 is showing how pretreatment with standard (group C) and different doses of NHEAF (group D and E) were able to prevent significant (p < 0.05) NaNO2 single dose induced increase in liver and kidney HIF-1 relative expression levels when compared with group A (control). All the pretreatment effects show significant difference when compared respectively with group A and B (negative control).

Decrease in relative expression of liver and kidney Nrf-2 ensued single dose oral administration of NaNO2 (group B) was prevented with pretreatment with standard drug (group C) and different doses of NHEAF (group D and E). The pretreatment effects showed almost no significant (p < 0.05) difference when compared with group A (control) as shown in Fig. 14. There was a significant (p < 0.05) increase in the expression of NF-κB in group B (NaNO2 intoxicated group without prevention) when compared respectively to group A, C, D, E, and F. All pretreated groups (C, D, and E) were able to prevent up-regulation of NF-κB relative expression as depicted in Fig. 15.

Effects of NHEAF on liver and kidney HIF-1 relative expression. Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 5). Bars with different letters are significantly different at p < 0.05. Where A = control (olive oil), B = NaNO2, C = NaNO2 (Vitamin E 100 mg/kg bwt and Omega-3 essential fatty acid (72 mg Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) + 48 mg Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)/kg bwt)), D = NaNO2 + 30 mg/kg bwt NHEAF, E = NaNO2 + 60 mg/kg bwt NHEAF and F = 60 mg/kg bwt NHEAF.

Effects of NHEAF on Liver and Kidney Nrf-2 relative expression. Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 5). Bars with different letters are significantly different at p < 0.05. Where A = control (olive oil), B = NaNO2, C = NaNO2 (Vitamin E 100 mg/kg bwt and Omega-3 essential fatty acid (72 mg Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) + 48 mg Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)/kg bwt)), D = NaNO2 + 30 mg/kg bwt NHEAF, E = NaNO2 + 60 mg/kg bwt NHEAF and F = 60 mg/kg bwt NHEAF.

Effects of NHEAF on Liver and Kidney NF-κB relative expression. Bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 5). Bars with different letters are significantly different at p < 0.05. Where A = control (olive oil), B = NaNO2, C = NaNO2 (Vitamin E 100 mg/kg bwt and Omega-3 essential fatty acid (72 mg Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) + 48 mg Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)/kg bwt)), D = NaNO2 + 30 mg/kg bwt NHEAF, E = NaNO2 + 60 mg/kg bwt NHEAF and F = 60 mg/kg bwt NHEAF.

Binding affinities of best-docked NHEAF phytochemical compounds revealed by GC-MS analysis against the active site of HIF-1 and NF-κB proteins

The in silico molecular docking revealed that nineteen (19) phytochemical compounds from NHEAF demonstrated a significant binding affinity for the target proteins (hypoxia-inducible factor HIF-1α (PDB: 3KCY) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB; PDB: 1A3Q)), as revealed by the change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG) shown in Table 2. Additionally, seven out of eight phytochemical compounds with high percentage total quantities were able to exhibit significant binding affinities for the target proteins. The ΔG values in Kcal/mol for HIF-1α and NF-κB respectively for these phytochemicals are − 4.4 and − 4.1 by 3-Tridecene, (Z)- (5.02%); −4.7 and − 4.5 by 3-Tetradecene, (E)- (15.39%); −4.5 and − 3.2 by Cetene (14.54%); −4.7 and − 3.9 by 1-Pentadecene (10.36%); by −8.6 and − 7.6 Cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3.beta (5.42%); −5.2 and − 4.1 by n-Tetracosanol-1 (7.25%); and − 4.8 and − 3.9 by Sulfurous acid, octadecyl 2-propyl ester (5.34%).

The ΔG values for HIF-1α ranged from − 4.4 to −8.6 kcal/mol, with cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3β) exhibiting the strongest binding affinity (−8.6 kcal/mol), significantly surpassing the reference (standard) ligand 8-hydroxyquinoline (−5.7 kcal/mol). The phenolic compound phenol, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl) also showed superior affinity (−6.3 kcal/mol) compared to the reference ligand. Though there is no named reference (standard) ligand used in the case of binding affinity against the active site of NF-κB, but ΔG values of NHEAF phytochemicals ranged from − 3.0 to −7.6 kcal/mol. Cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3β) showed highest inhibitory potential (ΔG = −7.6 kcal/mol) followed by phenol, 3,5-bis (1,1-dimethylethyl) with a ΔG of −5.8 kcal/mol among NHEAF nineteen phytochemicals that demonstrated significant binding affinities against NF-κB.

The predicted binding modes and interactions of the ligands with HIF-1α and NF-κB are presented in Fig. 16. Cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3β) (Fig. 16A) exhibited van der Waals interactions (GLN147, SER184, PHE207, THR196, LEU186, ASN294, LEU188, ARG238, ASP201, GLN203), Pi-Sigma interactions (ILE281, HIS199, HIS279, TYR102), and Pi-Alkyl interactions (TRP296) with the amino acid in the active site of HIF-1α. The ligand 3,5-bis (1,1-dimethylethyl)-phenol (Fig. 16B) formed van der Waals interaction (PHE100, THR196, ILE281, GLN147, ARG238, ASP201, LEU186, PHE207, ASN294, HIS279), Pi-Alkyl interactions (LEU188), and Pi-Pi T-shaped interactions (HIS199). Within the NF-κB active site, cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3β) (Fig. 16C) formed conventional hydrogen bonds (LYS153), extensive van der Waals interactions (LEU117, ARG156, ILE119, GLU92, ASP94, SER195, LEU209, PRO211, ARG193, ALA104, ARG103, GLN157), and Pi-Alkyl interactions (ARG160, PHE197, PRO208) with its amino acids. The 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-phenol ligand (Fig. 16D) primarily interacted via van der Waals forces (ARG103, ARG156, ARG160, ARG193, GLN157, ALA104, LYS153, LEU117, ASP94, GLU92, ILE119), supplemented by Pi-Sigma (ILE119) and alkyl interactions.

STD (8-hydroxyquinoline) is the standard drug for HIF-1.

Discussion

Interpretation of twenty-eight peaks in the chromatogram of Ficus exasperata leaf N-hexane ethyl acetate fraction (NHEAF) using database spectrum of known components stored in the NIST, revealed twenty-two of medicinal importance identified named compounds which are Phenol, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-; 3-Tridecene, (Z)-; Tridecane, 3-methyl- (Tridecane, 2-methyl-); 1-Iodo-2-methylnonane; Naphthalene, 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-2,6-dimet; 3-Tetradecene, (E)-; Decane, 1-iodo-; Cetene; Pentadecane, 2-methyl-; Heptadecane, 2-methyl-; 1-Pentadecene; Cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3.beta; n-Tetracosanol-1; Tetracontane, 3,5,24-trimethyl-; Tetracosane, 1-bromo-; Fumaric acid, 8-chlorooctyl tridecyl ester; n-Tetracosanol-1; Heneicosane; Tetratetracontane; Sulfurous acid, octadecyl 2-propyl ester; 2-methyltetracosane and Triacontane, 11,20-didecyl-. Out of these beneficial phytochemicals, eight are with high percentage total quantities which are 3-Tridecene, (Z)- (5.02%); Naphthalene, 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-2,6-dimet (5.18%); 3-Tetradecene, (E)- (15.39%); Cetene (14.54%); 1-Pentadecene (10.36%); Cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3.beta (5.42%); n-Tetracosanol-1 (7.25%); and Sulfurous acid, octadecyl 2-propyl ester (5.34%). This GC-MS results implies that NHEAF is rich in phytochemicals of beneficial roles. This implication agreed with the work of Akinloye and Ugbaja12 that reported fifty-one phytochemicals from Ficus exasperata leaves out of which six (Tetracontane, Tetracosane, Sulfurous acid - butyl hexadecyl ester, Sulfurous acid - butyl tetradecyl ester, Heptadecane, and Triacontane) are similar to this study GC-MS results.

Consumption of food additive is not actually invasive on human health but prolonged consumption of additives like sodium nitrite without taking protecting supplements is linked to increased multiple organ damage, cancer risks, hypoxia, altered consciousness, dysrhythmias, and sometime death1,2,4. Biotransformation of sodium nitrite ingested in the body system produces reactive species (RS) and radicals that inhibit the endogenous antioxidants defense activity and react with secondary amines producing carcinogenic organic compounds like nitrosamine, nitrosamide and N-nitroso compounds (NNC)4,5,6,30. The antioxidant system, both enzymatic and non-enzymatic, continuously scavenge and maintain RS at a steady state protecting biomolecules and maintaining cellular homeostasis5,13,20. Nrf-2 is essential for the activation of a number of intracellular antioxidant enzymes which in turn induces endogenous antioxidant systems8,30,31. SOD aid the dismutation of superoxide anions into molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, while CAT and GPx further degrade hydrogen peroxide and lipid hydroperoxides into water, and their corresponding alcohols11,20,21. Thus, impaired activities of antioxidant enzymes lead to accumulation of free radicals and cellular Damage5,13,20. This study found that a single oral dose of sodium nitrite (80 mg/kg body weight) results in a reduction of relative expression of Nrf-2 in the liver and kidneys, accompanied by a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in the activities of primary antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, and GPx) in serum, liver, and kidneys. These discoveries further corroborated prior research findings on sodium nitrite toxicity, indicating that a single oral dose of sodium nitrite (60 mg/kg body weight) could impair the activities of SOD, CAT, and GPx in the animal model1,5.

Oxidative stress, generated by an imbalance between the action of prooxidant molecules and cell antioxidant systems, is one of the most relevant factors responsible for the impairment of normal cellular functions22,30. The depletion noted in the antioxidant system may come from heightened activity to either inhibit or neutralise the reactive metabolites produced by sodium nitrite. In contrast to the toxicant group, pre-treatment of the experimental rats with NHEAF at varying doses (30 and 60 mg/kg body weight) effectively prevented the disruption in antioxidant defence (Nrf-2 expression and primary antioxidant enzyme activities) induced by sodium nitrite intoxication. These data imply that NHEAF administration can augment the body’s antioxidant defence system against excessive reactive species formation. These discoveries agree with the work of Ansari et al.5 that pretreatment with carnosine (a natural dipeptide) and N-acetylcysteine (derivative of cysteine) significantly prevents decrease antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT and GPx) activities, thereby strengthening cellular defense against oxidative damage induced by a single oral dose of sodium nitrite (60 mg/kg body weight) toxicity. Also, Adewale et al.1 documented that curcumin isolated from the turmeric plant was able to protect against a single oral dose of sodium nitrite (60 mg/kg body weight)-induced decrease antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT and GPx) activities.

Physiological concentrations of nitrite play vital role in the normal functioning of the body system, but increased exposure causes adverse health effects1,4,8,30. Excessive intracellular nitrite can induce oxidative/nitrosamine stress, by impairing the cellular antioxidant defense systems, decreasing the antioxidant power, and compromising the ability of the cell to defend against oxidative damage1,3,5,8,30. Ansari et al.4 reported that the rate at which sodium nitrite toxicity deplete the concentration of kidney GSH and total thiols were directly proportional to the concentration of single dose sodium nitrite used. It has been documented that the lowering of GSH levels ensued sodium nitrite toxicity can be attributed to decreased GR activity and RS-mediated direct oxidation of sulfhydryl groups of GSH4,5. Total thiols are important components of the antioxidant defense system and their depletion will weaken the first line of cellular protection against oxidants5,13,22. GSH which its homeostasis depends of activities of secondary antioxidant enzymes (GR, and γ-GCL) maintains thiol redox potential in cells, detoxifies xenobiotics, and works as an efficient oxygen radical scavenger1,13,20,22. GR catalyzes the reduction of glutathione disulfide (GSSG) to the sulfhydryl form GSH, while γ-GCL is the rate limiting enzyme in de novo production of GSH. Hence perturbations of the secondary antioxidant enzyme will also distort the antioxidant defense system of any cell in resisting oxidative stress13,20,22. NHEAF enhancement of antioxidant defense system against sodium nitrite-induced oxidative stress by preventing significant (p < 0.05) decrease in GSH and total thiols levels and activities of GR, and γ-GCL further supported the findings in this study. These findings agree with the findings of Ansari et al.5 that pretreatment with carnosine (a natural dipeptide) and N-acetylcysteine (derivative of cysteine) significantly prevents decrease in total thiols, GSH and GR ensued single oral dose of sodium nitrite (60 mg/kg body weight) toxicity.

Previous researchers have documented that sodium nitrite toxicity inactivated membrane-bound enzymes and induced exhaustion of the antioxidants capacity ultimately increasing the porosity of the membrane ensued from lipid peroxidation1,4,8,30. MDA one of lipid peroxidation products is used as a biomarker for radical-induced damage of biological membranes13,25. The transport of organic and inorganic solutes across the luminal membrane of kidney cells is an important function and largely depends upon ATPase activity. Hence, a decline in the activity of this enzyme would lead to derangement in the primary function of nephrons which would impair overall balance of solutes and ions in the body system3,4. Ansari et al.4 also discovered increase in MDA with concomitant decrease in total ATPase levels ensued sodium nitrite toxicity in a dose dependent manner. Ansari et al.4 then suggested that the lowered ATPase activity due to sodium nitrite toxicity reflected damaged of kidney cells basolateral membranes. The protective effects of NHEAF (group D and E) against single oral dose sodium nitrite-induced increase in MDA levels and serum ATPase, with concomitant decrease in liver and kidney total ATPase specific activity when compared with the control (group A) further justifies NHEAF enhancement of antioxidant defense system against sodium nitrite-induced oxidative/nitrosative stress. This justification supports previous researchers reports that pretreatment with carnosine and N-acetylcysteine5, curcumin isolated from the turmeric plant1 was able to protect against single dose of sodium nitrite-induced depletion of GSH with concomitant increase in MDA levels.

Depletion of GSH alongside vitamin E and C levels signified increased consumption of nonenzymic antioxidants to curb excess RS and protect other cellular constituents from oxidative damage13,25. Vitamin C, an important aqueous-phase antioxidant acts as a key regulator of gene transcription and peroxide processing13. In addition, Vitamin E which is a major membrane-bound antioxidant serve in scavenging the intracellular reactive oxygen and nitrogen species thereby reducing lipid peroxidation and membrane damage13,25. Both vitamin C and E are essential micronutrient required for normal metabolic functioning of the body13. The observed declination in the vitamin C and E levels could have been as a result of exhaustion of the vitamins levels in reducing the production of nitrosamine from sodium nitrite toxicity. This observation justifies the statement of Jafari et al.25 that depletion of vitamin E is not only ensued from increased tissue demand for vitamin E to neutralize free radicals in the body system but associated with induction of increase nitric oxide species and decrease of antioxidant enzyme. Also, the report of Akinloye et al.13 that decrease in vitamins C and E levels due to excess alcohol administration that corresponded with a decrease in tissue GSH levels ensued from high levels of GSH utilisation in conjunction with the low rate of its regeneration and synthesis. Nevertheless, pre-treatment with NHEAF at different doses (30 and 60 mg/kg body weight) was able to prevent sodium nitrite-induced depletion of both vitamin C and E. These results additionally confirm that NHEAF pretreatment can enhance antioxidant defense system against sodium nitrite-induced RS generations.

Inflammation plays a key role in the physiological response to hypoxic stress17. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) a prime controller for cellular oxygen homeostasis which is essential for maintaining oxygen homeostasis in hypoxic situations, is a heterodimeric transcription factor that is made up of two helix-loop-helix proteins, HIF-α and HIF-β7,9,17,32. HIF-1 acts as transcription factors mediating the hypoxic response in cells and tissues and direct upregulation glycolytic enzymes7,17. Additionally, cells to tissue hypoxia condition (upregulation of HIF-1) are concurrently accompanied with inflammation (increase in expression of NF- κB) responses and increase in extent of lipid peroxidation (increase in MDA levels) of cell membranes1,5,7,17. NF-κB is a transcription factor that suppresses expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby preventing proper regulations of inflammatory cascade and NF-κB activation increased the levels of RS generation that confers damages to the body system31. In this study it was observed that pretreatment with different doses of NHEAF were able to prevent up-regulation of HIF-1 and NF-κB relative expressions induced by sodium nitrite intoxication. These implies that NHEAF beneficial phytochemicals revealed by GC-MS analysis might have synergistically modulated the excessive expressions of these proteins (HIF-1 and NF-κB) induced by sodium nitrite intoxication. These observations corroborated with the study of Al-Rasheed et al.7 that quercetin (a flavonoid) is responsible for tissue protection against sodium nitrite induced-hypoxia (subcutaneously single dose of 75 mg/kg body weight) through its down -regulation of immuno-inflammatory mediators.

This study in silico aspect discovered that cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3β) and phenol, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl) are the best-docked NHEAF phytochemicals with great potentials in modulating expressions of HIF-1 and NF-κB proteins. It has been documented that cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3β) is a sterol (terpenoids) belonging to a class called isoprenoids, while phenol, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl) is a phenolic compound12,16,33,34. The detailed binding mode analyses in this study revealed that for HIF-1, cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3β) was stabilized via extensive van der Waals, Pi-Sigma, and Pi-Alkyl interactions with key residues, whereas the phenolic ligand was mainly involved in van der Waals, Pi-Alkyl, and Pi-Pi T-shaped interactions. Moreso, within the NF-κB active site, similar binding interactions were observed; the cholesta-derivative formed conventional hydrogen bonds with LYS153 and additional hydrophobic contacts, while the phenolic compound primarily engaged through van der Waals forces, supplemented by Pi-Sigma and alkyl interactions. The discoveries from the molecular dockings are consistent with previous research that genistein (a flavonoid) possessing a rigid cyclic framework and hydrophobic substituents tend to exhibit enhanced inhibiting interaction with hypoxia-inducible targets32. Also, with previous reports that squalene (a terpenoid) and total phenolic compounds present in Ficus exasperata leaf are one of the remarkable bioactive substances that is responsible for wide spectrum beneficial role of different kind of the plant leaf extract12,16.

One could propose that the prevention mechanism of oxidative or nitrosative stress is not only by synergistic actions of NHEAF phytochemicals in protecting against sodium nitrite induced systemic tissue hypoxia and inflammation (downregulation or modulation of HIF-1 and NF-κB excessive expressions); but might be by the abundance action of cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3β) since this particular phytochemical revealed best-docked great potentials in modulating expressions of HIF-1 and NF-κB proteins. One could further suggest that these NHEAF phytochemicals might have facilitated oxygen reaching the cellular level, thereby improving system function through aerobic metabolism and preventing cellular oxidative stress that ensues in hypoxic conditions. Also, these proposed mechanisms might be related to NHEAF phytochemicals preventing the consumption of total thiols and GSH precursors, as well as other vital nutrients, and to the maintenance of both primary and secondary antioxidant enzymes in regulating cellular redox homeostasis.

Limitations of the study

This research did not isolate the particular terpenoid (cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol) from Ficus exasperata leaves to protect against sodium nitrite-induced hypoxia, oxidative stress and membrane peroxidation. However, this research uses Ficus exasperata leaves terpenoid enriched fraction (Ficus exasperata leaf N-hexane ethyl acetate fraction (NHEAF)) to protect against sodium nitrite induced hypoxia, oxidative stress and membrane peroxidation furthering validating previous reports that present of terpenoid (squalene) in Ficus exasperata leaf is one of the remarkable bioactive substances responsible for broad spectrum beneficial role of different kind of Ficus exasperata leaf extract. Highlighting natural remedies of Ficus exasperata leaves to address oxidative stress, inflammation and cytotoxicity by serving as a phytotherapy for the control, prevention, and management of diseases and disorders.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that oral pretreatment of Ficus exasperata leaf N-hexane ethyl acetate fraction (NHEAF) which is rich in cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3β) (a terpenoid) was able to protect against sodium nitrite induced hypoxia, oxidative stress and membrane peroxidation. Thus, Ficus exasperata enrich cholesta-8,24-dien-3-ol, 4-methyl-, (3β) fraction could serve as an effective natural prophylactix or remedy for sodium nitrite-induced toxicity.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- CAT:

-

Catalase

- GC–MS:

-

Gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy

- γ-GCL:

-

Gamma-glutamyl cysteine ligase

- GPx:

-

Glutathione peroxidase

- GR:

-

Glutathione reductase

- GSH:

-

Reduced glutathione

- HIF-1:

-

Human inducible factor-1

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- NF-κB:

-

Nuclear factor kappa-B

- NHEAF:

-

Ficus exasperata leaves n-hexane ethyl acetate fraction

- Nrf-2:

-

Nuclear respiratory factor − 2

- RS:

-

Reactive species

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- TIC:

-

Total Ion Chromatogram

References

Adewale, O. O., Bakare, M. I. & Adetunji, J. B. Mechanism underlying nephroprotective property of Curcumin against sodium nitrite-induced nephrotoxicity in male Wistar rat. J. Food Biochem. 45 (3), e13341. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfbc.13341 (2021).

Imaizumi, K., Tyuma, I., Imai, K., Kosaka, H. & Ueda, Y. In vivo studies on methemoglobin formation by sodium nitrite. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 45, 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01274129 (1980).

Khan, M. W. et al. Protective effect of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) on sodium nitrite induced nephrotoxicity and oxidative damage in rat kidney. J. Funct. Foods. 5 (2), 956–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2013.02.009 (2013).

Ansari, F. A., Ali, S. N., Khan, A. A. & Mahmood, R. Acute oral dose of sodium nitrite causes redox imbalance and DNA damage in rat kidney. J. Cell. Biochem. 119 (4), 3744–3754. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.26611 (2018).

Ansari, F. A., Khan, A. A. & Mahmood, R. Ameliorative effect of carnosine and N-acetylcysteine against sodium nitrite induced nephrotoxicity in rats. J. Cell. Biochem. 120 (5), 7032–7044. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.27971 (2019).

El-Nabarawy, N. A., Gouda, A. S., Khattab, M. A. & Rashed, L. A. Effects of nitrite graded doses on hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity, histopathological alterations, and activation of apoptosis in adult rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 14019–14032. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-07901-6 (2020).

Al-Rasheed, N. M., Fadda, L. M., Attia, H. A., Ali, H. M. & Al‐Rasheed, N. M. Quercetin inhibits sodium nitrite‐induced inflammation and apoptosis in different rats organs by suppressing Bax, HIF1‐α, TGF‐β, Smad‐2, and AKT pathways. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 31 (5), e21883. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbt.21883 (2017).

Soliman, M. M., Aldhahrani, A. & Metwally, M. M. Hepatoprotective effect of thymus vulgaris extract on sodium nitrite-induced changes in oxidative stress, antioxidant and inflammatory marker expression. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 5747. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85264-9 (2021).

Lin, Y. et al. Effect of nitrite exposure on oxygen-carrying capacity and gene expression of NF-κB/HIF-1α pathway in gill of Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis). Aquacult. Int. 26, 899–911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10499-018-0256-0 (2018).

Elgawish, R. A. R., Rahman, H. G. A. & Abdelrazek, H. M. Green tea extract attenuates CCl4-induced hepatic injury in male hamsters via inhibition of lipid peroxidation and p53-mediated apoptosis. Toxicol. Rep. 2, 1149–1156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2015.08.001 (2015).

Alhassan, H. H. et al. GC-MS-based profiling and ameliorative potential of Carissa opaca Stapf ex Haines fruit against cardiac and testicular toxicity: An In vivo study. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19324 (2023).

Akinloye, D. I. & Ugbaja, R. N. Potential nutritional benefits of ficus exasperata Vahl leaf extract. Nutrire 47 (1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41110-022-00157-9 (2022).

Akinloye, D. I., Ugbaja, R. N. & Idowu, O. M. O. Modulatory effects of ficus exasperata (Vahl) aqueous leaf extract against alcohol-induced testicular testosterone and total thiol pool perturbations in Wistar rats. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 32 (3), 357–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00580-023-03444-7 (2023).

Bamisaye, F. A. et al. Ameliorative potential of ethanol leaf extract of ficus exasperata in acetaminophen-induced toxicity in albino rats. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 32 (1), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00580-022-03419-0 (2023).

Oso, B. J. & Olaoye, I. F. Assessment of antioxidant potential, phenolic and flavonoid contents of different solvent extracts from dried leaves of ficus exasperata vahl. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 93(2), 373–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40011-022-01431-6 (2023).

Akinloye, D. I. et al. Ficus exasperata N-hexane-ethyl acetate extract inhibits Lipoxygenase and protects against CCl4–Induced TNF-α upregulation in female Wistar rats. Pharmacol. Research-Natural Prod. 6, 100148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prenap.2025.100148 (2025).

Pham, K., Parikh, K. & Heinrich, E. C. Hypoxia and inflammation: insights from high-altitude physiology. Front. Physiol. 12, 676782. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.676782 (2021).

Truong, D. H. et al. Effects of solvent—solvent fractionation on the total terpenoid content and in vitro anti-inflammatory activity of Serevenia buxifolia bark extract. Food Sci. Nutr. 9 (3), 1720–1735. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.2149 (2021).

Marklund, S. & Marklund, G. Involvement of the superoxide anion radical in the autoxidation of pyrogallol and a convenient assay for superoxide dismutase. Eur. J. Biochem. 47 (3), 469–474 (1974).

Bauché, F., Fouchard, M. H. & Jégou, B. Antioxidant system in rat testicular cells. FEBS Lett. 349 (3), 392–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-5793(94)00709-8 (1994).

Hadwan, M. H. & Abed, H. N. Data supporting the spectrophotometric method for the estimation of catalase activity. Data Brief 6, 194–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2015.12.012 (2016).

De Donatis, G. M., Moschini, R., Cappiello, M., Del Corso, A. & Mura, U. Cysteinyl-glycine in the control of glutathione homeostasis in bovine lenses. Mol. Vis. 16, 1025 (2010). http://www.molvis.org/molvis/v16/a113

Tsakiris, S. & Deliconstantinos, G. Influence of phosphatidylserine on ((Na+ + K+)-stimulated ATPase and acetylcholinesterase activities of dog brain synaptosomal plasma membranes. Biochem. J. 220 (1), 301–307. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj2200301 (1984).

Sedlak, J. & Lindsay, R. H. Estimation of total, protein-bound, and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with ellman’s reagent. Anal. Biochem. 25, 192–205 (1968).

Jafari, R. A., Kiani, R., Shahriyari, A., Asadi, F. & Hamidi-Nejat, H. Effect of dietary vitamin E on Eimeria tenella-induced oxidative stress in broiler chickens. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 11 (38), 9265–9269. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB11.3207 (2012).

Jagota, S. K. & Dani, H. M. A new colorimetric technique for the Estimation of vitamin C using Folin phenol reagent. Anal. Biochem. 127 (1), 178–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(82)90162-2 (1982).

Wang, J., Wang, W., Kollman, P. A. & Case, D. A. Automatic atom type and bond type perception in molecular mechanical calculations. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 25 (2), 247–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmgm.2005.12.005 (2006).

Kumar, K. A. et al. Multifunctional inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 by MM/PBSA, essential dynamics, and molecular dynamic investigations. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 107, 107969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmgm.2021.107969 (2021).

Varghese, F., Bukhari, A. B., Malhotra, R. & De, A. IHC profiler: an open source plugin for the quantitative evaluation and automated scoring of immunohistochemistry images of human tissue samples. PloS One. 9 (5), e96801. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096801 (2014).

Soliman, M. M., Aldhahrani, A., Alghamdi, Y. S. & Said, A. M. Impact of thymus vulgaris extract on sodium nitrite-induced alteration of renal redox and oxidative stress: Biochemical, molecular, and immunohistochemical study. J. Food Biochem. 46 (3), e13630. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfbc.13630 (2022).

Soliman, M. M., Aldhahrani, A., Elshazly, S. A., Shukry, M. & Abouzed, T. K. Borate ameliorates sodium nitrite-induced oxidative stress through regulation of oxidant/antioxidant status: involvement of the Nrf2/HO-1 and NF-κB pathways. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-021-02613-5 (2022).

Mukund, V. et al. Molecular Docking studies of angiogenesis target protein HIF-1α and genistein in breast cancer. Gene 701, 169–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2019.03.062 (2019).

Bouvier-Navé, P., Husselstein, T., Desprez, T. & Benveniste, P. Identification of cDNAs encoding sterol methyl‐transferases involved in the second methylation step of plant sterol biosynthesis. Eur. J. Biochem. 246 (2), 518–529. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00518.x (1997).

Micera, M. et al. Squalene: more than a step toward sterols. Antioxidants 9 (8), 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9080688 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate the Department of Biochemistry, College of Biosciences, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Ogun State, for providing a conducive animal facility (animal house) for rearing and carrying out the experiments on the rats, as well as a standard-equipped laboratory and sufficient bench space for conducting the experimental assays and the research as a whole.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not for profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The research work was designed by DIA under the major supervision of OAA. Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript were carried out by DIA, CAM, EUA, TAJ, TAA, ATK, ISA, EOO, and OAA, before submission of the manuscript for publication. All authors have read and approved the manuscript in the present form and granted corresponding author the permission to submit the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Prior to the experiment with ethical no. FUNAAB - BCH- DI A022, the Departmental Animal Ethical Committee (FUNAAB- BCH) gave its clearance. All the experiments were conducted following the authorized protocols and standards guidelines for animal research as per the Animal Research: Reporting in Live Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akinloye, D.I., Moses, C.A., Alum, E.U. et al. Chelesta-8,24-dien-3-ol in Ficus exasperata leaves enhances the prevention of sodium nitrite-induced hypoxia by binding to HIF-1 and NF-κB. Sci Rep 16, 4822 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35307-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35307-w