Abstract

Gastric cancer (GC) is primarily associated with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, which disrupts gastric mucosa homeostasis, leading to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and intestinal metaplasia (IM). We previously found that ELMO1 methylation increased with the progression of chronic gastric inflammation, and its expression was significantly elevated in GC tissues. Further analysis indicated that ELMO1 methylation may interact with Med31. This paper aims to determine the molecular mechanism of ELMO1 methylation in H. pylori-infected GC. The viability, proliferation, and migration of H. pylori-infected AGS cells were detected by cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8), wound healing, and colony information assay, respectively. The methylation status of ELMO1 was determined by methylation-specific PCR (MSP) analysis. mRNA expression levels were detected by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Western blotting and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) were used to evaluate protein levels. Co-immunoprecipitation was used to detect proteins interacting with ELMO1. Co-culture experiments were performed to explore the mechanism of ELMO1 methylation in regulating M2 polarization and IM in H. pylori-infected AGS cells. ELMO1 methylation was significantly upregulated in AGS cells upon H. pylori infection. Our data suggest that ELMO1 methylation accelerated H. pylori-induced IM in AGSs by interacting with Med31. Additionally, we found that ELMO1 methylation drives M2 polarization in H. pylori-infected GCs through interaction with Med31. Further study indicated that ELMO1 methylation enhances H. pylori-induced EMT and IM by promoting M2 polarization. This study suggests that ELMO1 methylation interacts with Med31 and activates M2 macrophage polarization s to facilitate EMT and IM in GC with H. pylori infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a gram-negative microaerophilic that can colonize and persist in the human gastric mucosa. This bacterium is closely associated with approximately 80% of gastric cancer (GC) cases1 and has been classified as a Group 1 carcinogen by the World Health Organization (WHO)2. H. pylori infection is a key risk factor for GC, promoting its development through various mechanisms, including the induction of chronic inflammation, gastric mucosal atrophy, and pathological changes such as intestinal metaplasia (IM), which may ultimately progress to GC3,4. GC is a common malignant tumor worldwide with high morbidity and mortality, posing a serious threat to human health5. The early symptoms of GC are often non-specific, leading to frequent diagnosis at advanced stages, resulting in poor treatment outcomes and prognosis. Therefore, investigating its pathogenesis and identifying effective prevention and treatment strategies for GC are of great clinical significance.

IM refers to the pathological process where gastric mucosal epithelial cells, under chronic inflammation stimulation, gradually transform into cells resembling small or large intestine epithelial cells. IM is a common precancerous lesion of GC. It has been established that widespread abnormal DNA methylation occurs in IM, contributing to GC progression6,7. DNA methylation is an epigenetic modification that significantly impacts gene stability and expression. For example, Li et al. indicated that promoter hypermethylation and downregulation of eyes absent homolog 4 (EYA4) in gastric cardia IM are essential for GC development8. Furthermore, the DNA damage signal acts as an anti-cancer barrier in IM, and its dysfunction may be related to methylation changes, thus promoting GC9. Genome-wide DNA methylation and transcriptome studies revealed that the molecular characteristics of GC precancerous lesions may be associated with changes in IM and DNA methylation7. In gastric mucosa, H.pylori infection has been shown to accelerate age-related methylation of genes such as caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX2), and the rapid demethylation of this promoter is associated with its upregulated expression in GC10. This indicates that H. pylori infection is a key driver of dynamic DNA methylation changes in the sequence from pre-neoplastic lesions to GC. Furthermore, we previously found that the methylation of engulfment and cell motility 1 (ELMO1), which increases with the progression of H. pylori-associated chronic inflammation independently of age, is also linked to its significant overexpression in GC tissues11. Further analysis indicated that ELMO1 methylation could strongly interact with Med31. Mediator complex subunit 31 (Med31) is an essential subunit of the mediator complex, a large multi-subunit assembly that acts as a critical bridge between transcription factors and RNA polymerase II, thereby regulating gene transcription12,13. It plays vital roles in fundamental biological processes including embryonic growth, cell proliferation, and differentiation14. The study by Mauldin et al. specifically demonstrated that ELMO1 is a novel regulator of Med3115, establishing a direct molecular link between these two proteins.

ELMO1 is located on human chromosome 17q25.3 and encodes a protein crucial for cell migration and cytoskeletal rearrangement. By interacting with dedicator of cytokinesis (DOCK) proteins such as DOCK10, ELMO1 regulates cell migration and invasion, affecting tumor progression16. It has been established that abnormal ELMO1 expression contributes to the development and progression of numerous cancers. For example, ELMO1 overexpression is associated with invasion and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma17. Moreover, ELMO1 methylation has attracted extensive attention as a potential biomarker for upper gastrointestinal cancers including GC. Studies have found that ELMO1 methylation can be detected in body fluids such as plasma, providing a new direction for early diagnosis and prognostic evaluation of GC18,19,20. Nevertheless, the specific mechanism of ELMO1 methylation in GC development remains to be fully elucidated.

In the current study, we aimed to investigate whether of ELMO1 methylation interacts with Med31 during the IM stage in human gastric epithelial AGS cells infected with H. pylori. Additionally, we explored the molecular basis implicating the role of ELMO1 methylation in GC development. This study helps reveal the mechanisms underlying the initiation and progression of GC and provides new avenues for its early diagnosis and treatment.

Materials and methods

Reagents

L-Methionine (MCE, HY-N0326, USA) and 5-Azacytifine (MCE, HY-10586, USA) were purchased from MedChemExpress and dissolved in double distilled water (ddH2O) at a final concentration of 10 mM and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a final concentration of 1 mM, respectively.

Cell lines and growth conditions

The human gastric adenocarcinoma AGS cell line was purchased from iCell Bioscience Inc. (iCell, iCell-h016, China). Following the supplier’s recommendations and established protocols21, cells were cultured in F12K medium (iCell, iCell-h016-001b, China) supplemented with 10% high-quality fetal bovine serum (FBS) (gibco, 10,091–148, South America) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. The human monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1 (commonly used as a macrophage model) was purchased from Wuhan Procell life science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Procell, cl-0233, China). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2, and cultured in Rosewell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Procell, CM-0233, China) containing 10% FBS, 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin22,23. Macrophages were differentiated from THP-1 cells by culturing them in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells per well and treating them with 320 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 24 h24.

Bacterial culture and infection

H. pylori, strain ATCC26695 (cag A-positive, vac A-positive) was purchased from Ningbo Mingzhou Biotechnology Co., LTD (Ningbo, China). The strain was cultured on Columbia blood agar plates at 37℃ under microaerophilic conditions (85% N2, 10% CO2, and 5% O2). AGS cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well of F12K medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptromycin, and grown to reach 80% confluency. Before infection, cells were washed with antibiotic-free F12K medium. Then, H. pylori bacteria were harvested from Columbia blood agar plates and suspended in antibiotic-free F12K medium supplemented with 10% FBS. When the bacterial suspension reached a concentration of 1 × 10⁸ CFU/mL, it was added to the AGS cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 (bacteria-to-cell ratio 50:1) for infection21,25.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability and proliferation were assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (MCE, HY-K0301, USA). Briefly, AGS cells were seeded into a 96-well culture plate at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well in 100 μL of complete F12K medium and pre-cultured overnight to allow for adhesion. Following attachment, the cells were infected with H. pylori at an MOI of 50:1 for 24. After the infection period, the original culture medium was carefully aspirated. Subsequently, 100 μL of freshly prepared CCK-8 working solution was added to each well, with blank control wells included for background correction. The plate was then incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek, Elx-800, USA). Cell viability was calculated as follows: Viability (%) = [(Experimental OD- Blank OD)/(Control OD—Blank OD] × 100%. The experiment was performed with six replicate wells per group and independently repeated three times.

Wound healing assay

Cell migration was evaluated using a standard wound healing assay. AGS cells were cultured in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well in complete F12K medium until they reached approximately 90% confluence. Then, the cells were infected with H. pylori for 24 h. A uniform scratch wound was created in the cell monolayer using a sterile 200 μL pipette tip. The dislodged cells were gently washed away by rinsing the wells three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Procell, PB180327, China). After washing, fresh complete medium was added. The plate was then returned to the 37 °C, 5% CO₂ incubator (Thermo, 3100, USA) for further cultivation. Images of the scratch wounds were captured at 0 h and 24 h post-scratching using an inverted microscope (Nikon, Ts2R, Japan). The cell migration rate was quantitatively analyzed by measuring the wound widths and was calculated using the formula: Migration Rate (%) = [(Wound Width at 0 h—Migrated Width at 24 h) / Wound Width at 0 h] × 100%. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and independently repeated three times.

Colony formation assay

AGS cells were harvested, counted, and plated into 6-well plates at a density of 500 cells per well in F12K medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptromycin and allowed to adhere for 24 h at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO₂. Then, the cells were infected with H. pylori for 24 h. After removing the culture medium containing bacteria, the cells were cultured in fresh medium for 1–2 weeks to allow for colony formation. During this period, the culture medium was refreshed every 3 days to maintain optimal growth conditions. Subsequently, the cell colonies were fixed with methanol and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 30 min. Finally, the colonies were observed and quantified using a microscope (BioTek, Elx-800, USA).

Methylation-specific PCR (MSP) analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from the cells using a Cell Genome DNA Extraction kit (Solarbio, D1700-100 T, China). The DNA was then treated with bisulfite using the EZ DNA Methylation™ Kit (ZYMO, D5001, USA). Then, the treated DNA was amplified using methylation-specific primers and unmethylation-specific primers for the ELMO1 gene. The primers for methylated ELMO1 were: 5′-ATTTTAAATATACGCGCGTATTTTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACTTCGTAAAAATCTCGACTTCG-3′ (reverse). The primers for unmethylated ELMO1 were: 5′-TTTAAATATATGTGTGTATTTTTGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACTTCATAAAAATCTCAACTTCAAA-3′ (reverse). MSP analysis was performed in a thermal cycler (ABI, 4,375,786, USA) under the following condictions: 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 7 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) analysis

Cells were lysed using ice-cold IP lysis buffer supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) to inhibit protease activity. A BCA assay was used to determine the protein concentration. The input was used as the positive control, while IgG was utilized as the negative control. The IP samples were incubated with the antibody against ELMOl or IgG, followed by immunoprecipitation with magnetic beads. The beads were washed and resuspended, and the target proteins (DOCK10 and Med31) were detected by Western blotting. Antibodies used for CO-IP analysis were: DOCK10 antibody (1:2000, Novus, NB100-60,669, USA), ELMO1 Rabbit mAb (1:750, ZEN BIO, R24201, China), MED31 Antibody (1:1000, Affinity, DF9618, China), HRP Conjugated Rabbit anti-Human IgG polyclonal Antibody (1:5000, HUABIO, HA1024, China), GAPDH Mouse Monoclonal antibody (1:20,000, proteintech, 60,004-1Ig, China), Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (1:10,000, ZEN BIO, 511,203, China), and Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (1:10,000, ZEN BIO, 511,103, China).

Enzyme-Linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay

To investigate the release of the epithelial-derived alarmin interleukin 33 (IL-33), a known driver of M2 macrophage polarization, its levels in cell culture supernatants were determined. Measurements were performed using a Human IL-33 ELISA kit (J&L Biological Company, JL19282, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance was read on a microplate reader (BioTek, ELx-800, USA), and protein concentration were calculated from the standard curve.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA from the AGS cells was extracted with TRIzol reagent (AGBIO, China) and quantified by a NanoDrop2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo, USA) by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm. High-quality RNA was then reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the NovoScript® Plus 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Novoprotein, E047, China). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR High-Sensitivity qPCR SuperMix (Novoprotein, E401, China) on an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR system (ABI, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. GAPDH was used as an internal control.

Western blotting analysis

Proteins were extracted with RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors, followed by total protein quantification using a BCA assay. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE using gels of appropriate concentrations (8%, 10%, or 12%) based on the molecular weight of the target protein and then transferred to a PVDF membrane via semi-dry electrophoresis. The membranes were blocked with a 5% skim milk solution for 2 h at room temperature. After incubation with primary antibodies, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C. After three washes with TBST, secondary antibodies were added and the membranes were washed three times with TBST. Finally, the ECL luminescent solution was applied to the membrane and signals were imaged using the E-BLOT system (E-BLOT, Touch Imager XLI, China).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software. Experimental results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The differences between groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. A significance level of p < 0.05 was applied, and experiments were carried out with three independent biological replicates.

Results

H. pylori infection alters the expression of intestinal metaplasia markers in AGS cells

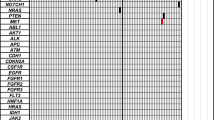

To evaluate the impact of H. pylori infection on gastric epithelial cells, AGS cells were co-cultured with H. pylori at an MOI of 50:1 for 24 h. Cell viability, migration, and proliferation were assessed, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1A-C, H. pylori infection significantly increased cell viability, migration, and proliferation of AGS cells compared to the control group. Next, we determined the expression of ELMO1, DOCK10, and Med31 in H. pylori-infected AGS cells. qRT-PCR and Western blotting analyses showed that ELMO1 and Med31 were significantly upregulated, whereas DOCK10 was downregulated (Figs. 1D, E). We further examined the influence of H. pylori on specific markers for IM. As depicted in Figs. 1F, G, H. pylori infection remarkably increased CDX2 and MUC2 expression but decreased the expression of KLF4 in AGS cells (all p < 0.01). Moreover, we found that H. pylori infection significantly accelerated ELMO1 methylation (Fig. 2).

ELMO1 is upregulated in H. pylori-infected AGS cells. (A) CCK8 assay analysis of the effect of H. pylori infection on cell viability of AGS. (B) Wound healing assay to detect the migration ability of H. pylori-infected AGS cells. (C) Cell proliferation was measured by colony formation assay. (D–E) qRT-PCR and Western blotting analysis were performed to detect the expression of ELMO1, DOCK10, and Med31. (F–G) The intestinal metaplasia-related markers (CDX2, MUC2, and KLF4) were detected by qRT-PCR and Western blotting.

H. pylori infection induces DNA methylation of the ELMO1 gene in AGS cells. Methylation-specific PCR (MSP) was performed to analyze the methylation status of ELMO1 in AGS cells with or without H. pylori infection. (A) Representative MSP gel image. The positions of the PCR products specific for the methylated (M) and unmethylated (U) alleles of ELMO1 are indicated. Lane 1: DNA molecular weight marker. Lanes 2–3: Control, uninfected AGS cells. Lanes 4–5: AGS cells infected with H. pylori. B. Densitometric quantification of the methylated ELMO1 band (M) from three independent MSP experiments.

ELMO1 methylation promotes H. pylori-induced intestinal metaplasia in GC

To determine the role of ELMO1 methylation in IM, AGS cells were first infected with H. pylori and then treated with 1 μM 5-Azacytidine for 24 h. Treatment with 5-Azacytidine significantly decreased cell viability, migration, and proliferation compared to the H. pylori infection alone group (Fig. 3A–C). Furthermore, 5-Azacytidine treatment caused a dramatic reduction in ELMO1 methylation than the untreated cells (Fig. 3D) and reduced the expression of methylation-related genes (DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B) compared to the untreated, infected cells (Fig. 3E). qRT-PCR and Western blotting analyses showed that 5-Azacytidine treatment markedly decreased CDX2 and MUC2 expression and enhanced KLF4 expression compared to untreated, infected cells (Figs. 3F, G). These results indicate that ELMO1 methylation is functionally linked to the expression of IM markers.

ELMO1 methylation promotes H. pylori-induced intestinal metaplasia in GC. (A) CCK8 assay was used to determine the cell viability of H. pylori-infected AGS cells with 5-Azacytidin treatment. (D) ELMO1 methylation was measured through MSP analysis. Representative gel images of MSP products. Lanes are as follows: 1, Marker; 2–3, Control group; 4–5, H. pylori-infected group; 6–7, H. pylori-infected + 5-Azacytidin treatment group. For each group, the left lane (M) shows the PCR product from the methylated gene, and the right lane (U) shows the product from the unmethylated gene. Quantitative analysis of ELMO1 methylation levels from three independent experiments. (E) The mRNA expression levels of DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B were evaluated by qRT-PCR analysis. (F–G) The intestinal metaplasia-related markers (CDX2, MUC2, and KLF4) were detected by qRT-PCR and Western blotting.

ELMO1 methylation accelerates H. pylori-induced intestinal metaplasia in GC by interacting with Med31

To determine how ELMO1 methylation regulates IM in AGS cells, we treated cells with L-Methionine, a key methyl donor in cellular metabolism, to create a hypermethylation environment. A CCK8 assay showed that treatment with 1.2 mM L-Methionine significantly reduced cell viability, and this concentration was selected for further experiments (Fig. 4A). We next detected the expression of ELMO1 and its potential binding partners. Given that ELMO1 typically functions through interactions with DOCK family proteins to activate Rac signaling and that our preliminary data suggested a role for the transcription mediator subunit Med31, we focused on DOCK10 and Med31. The results showed that ELMO1 and Med31 were notably upregulated, but DOCK10 was downregulated in AGS cells with L-Methionine compared to the control group (Figs. 4B, C). ELMO1 methylation was also dramatically upregulated by L-Methionine treatment (Fig. 4D). To determine the functional consequence of this methylation and to clarify the specific protein interactions, we performed Co-IP analysis. CO-IP analysis confirmed that ELMO1 interact with Med31, but not DOCK10, under these hypermethylation conditions (Fig. 4E). Collectively, these findings suggest that increased ELMO1 methylation drives its interaction with the transcriptional regulator Med31, potentially influencing gene expression programs relevant to IM.

ELMO1 methylation can interact with Med31 in AGS cells. (A) CCK8 assay was used to determine the cell viability of AGS cells with L-Methionine treatment. (B–C) ELMO1, DOCK10, and Med31 expression were determined by qRT-PCR and Western blotting. (D) ELMO1 methylation was measured through MSP analysis. (E) ELMO1 could interact with Med31 through CO-IP analysis.

ELMO1 methylation drives M2 polarization in GC through interaction with Med31

As shown in Figs. 5A, B, qRT-PCR and ELISA analysis showed that H. pylori infection significantly promoted the expression of IL-33 compared to controls. To verify if ELMO1 methylation drives M2 polarization by interacting with Med31, activated THP-1-drived macrophages were co-cultured with supernatants from H. pylori-infected AGS cells. Specifically, activated THP-1 cells (as macrophage models) were co-cultured with supernatants collected from AGS cells infected with H. pylori. First, a CCK8 assay was performed to confirm that the conditioned supernatant from infected AGS cells supported THP-1 cell viability. As shown in Fig. 5C, the viability of the THP-1 cells was significantly enhanced in the (AGS + H. pylori) + THP-1 group than in the AGS + THP-1 group, ensuring the validity of the subsequent polarization experiments. We then evaluated M2 polarization by measuring the mRNA expression of the classic M2 macrophage marker, CD206, using qRT-PCR. Our results revealed that supernatants from H. pylori-infected AGS cells significantly increased CD206 mRNA expression in THP-1 cells (Fig. 5D). Further analysis demonstrated that IL-33 expression was up-regulated in the co-culture system (Fig. 5E). Collectively, these data indicate that H. pylori infection in AGS cells, which induces ELMO1 methylation, is associated with a shift towards M2 polarization in co-cultured macrophages.

ELMO1 methylation drives M2 polarization through interacting with Med31 (A–B) The expression of IL-33 in H. pylori-infected AGS cells was determined by qRT-PCR and ELISA analysis. (C) The effect of H. pylori-infected AGS on cell viability of THP-1 was determined by CCK8 analysis. This experiment served to validate the health of the THP-1 cells under the co-culture conditions used for assessing polarization. (D) The effect of H. pylori-infected AGS on M2 polarization of THP-1 cells was directly evaluated by measuring the mRNA expression of the classic M2 marker CD206 using qRT-PCR. (E–F) The expression of IL-33 in the (AGS + H. pylori) + THP-1 co-culture system was determined by qRT-PCR and ELISA analysis.

ELMO1-Med31 axis enhances H. pylori-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and intestinal metaplasia by promoting M2 polarization in GC

To explore the mechanisms of ELMO1 methylation in IM, supernatant from H. pylori-infected AGS cells was co-cultured with THP-1 cells, and the resulting conditional medium from this co-culture was subsequently used to treat fresh AGS cells. We observed that the viability, migration, and proliferation of AGS cells were notably increased in the group treated with medium from the (AGS + H. pylori + THP-1) co-culture group compared to the group treated with medium from the (AGS + THP-1) co-culture (Figs. 6A–C). The expression of ELMO1 and Med31 was remarkably upregulated in these cells (Figs. 6D, E). Conversely, the levels of ELMO1 methylation and the expression of methylation-related genes (DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B) were decreased (Figs. 6F, G). IL-33 expression was upregulated in the (AGS + H. pylori + THP-1) + AGS group (Fig. 6H). Moreover, analysis of EMT markers showed that Vimentin, Snail, and fibronectin were upregulated, whereas E-cadherin was downregulated in the (AGS + H. pylori + THP-1) + AGS group (Fig. 7). This key experiment demonstrates that the M2-polarized macrophage conditioned medium is sufficient to induce molecular changes consistent with EMT and IM in gastric epithelial cells.

ELMO1 methylation promotes the progression of GC by activating M2 polarization through interacting with Med31 (A) CCK8 assay was used to determine the cell viability of AGS cells after co-cultured with THP-1. (B) Wound healing assay to detect the migration ability. (C) Cell proliferation was measured by colony formation assay. (D–E). ELMO1 and Med31 expression were determined by qRT-PCR and Western blotting analysis. (F) ELMO1 methylation was measured through MSP analysis. (H) IL-33 expression was determined by qRT-PCR analysis. (G) The mRNA expression levels of DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B were evaluated by qRT-PCR analysis.

Discussion

H. pylori plays a primary role in the initiation and development of GC by affecting various biological processes in gastric mucosal cells. H. pylori secretes various virulence factors, such as CagA, which can activate the AKT signaling pathway in gastric epithelial cells, enhance cell proliferation, and inhibit apoptosis, thus promoting GC development26,27. Besides, Lin et al. showed that H. pylori could accelerate the stemness of GC cells and promote tumor invasion and metastasis by activating the AKT signaling pathway28. Our findings are consistent with this, as H. pylori infection significantly increased the viability, migration, and proliferation of AGS cells. This observed increase in cell viability and proliferation, while seemingly paradoxical in the context of a pathogenic infection, aligns with the model of H. pylori-driven precancerous remodeling. The hyperproliferative phenotype is interpreted as part of the compensatory and dysplastic responses that contribute to the initiation of gastric carcinogenesis, particularly within the metaplastic transition. H. pylori infection has been implicated in IM progression29,30. We observed that H. pylori infection was associated with the molecular signature of intestinal metaplasia in AGS cells.

DNA methylation, an epigenetic modification, can regulate gene expression without alteration of the DNA sequence. Studies revealed that H. pylori infection is often accompanied by DNA methylation modification in GC progression31. We found that H. pylori infection significantly increased the ELMO1 methylation and its expression level in AGS cells. Consistent with our results, Kim et al. reported that both the methylation and expression levels of ELMO1 were substantially higher in H. pylori-positive GCs32. However, the molecular mechanism underlying how ELMO1 methylation affects H. pylori-infected GC remains unclear and needs further investigation. To explore the roles of ELMO1 methylation in H. pylori-infected GC, AGS cells were first exposed to H. pylori and then treated with 1 μM 5-Azacytidine. Our results demonstrated that ELMO1 methylation significantly accelerated cell variability, migration, and proliferation in AGS cells with H. pylori infection. Crucially, the reversal of the pro-proliferative phenotype upon treatment with the demethylating agent 5-Azacytidine provides direct evidence that ELMO1 methylation is a key driver of the enhanced cell viability and proliferation observed following H. pylori infection. ELMO1 is a kind of protein closely related to the Rac GTPase family. ELMO1, together with DOCKs, constitutes the guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) of Rac1, which can activate the Rac1 signaling pathway and then participate in the occurrence of numerous cancers33. Our study revealed that ELMO1 methylation contributed to the formation of intestinal metaplasia by interacting with Med31, but not with DOCK10. These results indicate that ELMO1 methylation is involved in H. pylori-induced intestinal metaplasia in GC by interacting with Med31.

Macrophages, highly plastic immune cells, can be polarized into different types, including M1 and M2 macrophages. M1 macrophages usually participate in anti-tumor immune responses, while M2 macrophages are involved in the growth and metastasis of tumors. Studies have found that there are more M2 macrophages in GC, which promotes tumor development through various mechanisms34,35,36. In this study, we found that ELMO1 methylation notably increased the expression of the M2 marker CD206 in AGS cells with H. pylori infection. Studies have shown that H. pylori infection can change the status of macrophages and affect the immune response, especially M2 macrophages have a key role in this process. For instance, Peng et al. showed that H. pylori infection could induce the polarization of M2 macrophage by activating ILC2 cells37. In addition, the research of Yang et al. found that H. pylori infection could promote M2 macrophage polarization by activating the IL-4-STAT6 signaling pathway in chronic atrophic gastritis38. These findings suggest that ELMO1 methylation is associated with M2 polarization in H. pylori-infected AGS cells.

EMT refers to the transformation of epithelial cells into cells with mesenchymal characteristics, which enables cancer cells to gain the ability to invade and migrate, thus promoting tumor metastasis. EMT has a major role in the occurrence and development of GC. In the early stage of GC, epithelial cells acquire the ability to migrate and invade through the EMT process, which makes it easier for them to rectangle from the primary tumor and invade the surrounding tissues and distant organs39,40. Our study showed that M2 polarization was linked to upregulated the expression levels of EMT-related proteins Vimentin, Snail, and fibronectin in H. pylori-infected AGS cells. It has been indicated that mesenchymal stem cells derived from GC can induce the polarization of M2 macrophages and promote EMT and metastasis of GC cells by secreting TGF-β41. Zhou et al. showed that polarization of M2 macrophages induced by STAT6 and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways promoted EMT of human peritoneal mesothelial cells, ultimately accelerating the progression of peritoneal fibrosis42. Additionally, M2 macrophages can promote EMT through direct interaction with cancer cells, aggravating GC occurrence and metastasis43. Therefore, the H. pylori-induced increase in gastric epithelial cell proliferation is not an isolated event but is embedded within a larger pathogenic network. It is mechanistically sustained by ELMO1 methylation, reinforced through its interaction with Med31, and further amplified by the resulting M2-polarized tumor microenvironment, which collectively foster a state conducive to metaplastic transformation and tumor progression. Taken above, our study is the first study to reveal that ELMO1 methylation can facilitate H. pylori-induced EMT and intestinal metaplasia in GC by, at least in part, activating M2 polarization of macrophages through interaction with Med31.

Our study has certain limitations. Up to now, the molecular mechanism of EMLO1 methylation in H. pylori-infected GC has only been studied in vitro, but not verified in vivo. We are designing corresponding in vivo experiments, hoping to further verify and improve our findings in the future. Despite the limitation, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have reported the role of ELMO1 methylation in H. pylori-infected GC, our study could provide the theoretical foundations for understanding gastric diseases associated with H. pylori infection.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that ELMO1 methylation was associated with a promotive effect on H. pylori-induced EMT and IM. The molecular mechanism of ELMO1 methylation in GC was closely related to the polarization of macrophages, which suggested that ELMO1 methylation facilitated H. pylori-induced EMT and IM in GC via activating M2 polarization of macrophages through interaction with Med31. These findings provide a theoretical basis for further study on the infection mechanism of H. pylori in gastric diseases.

Data availability

Relevant experimental data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ford, A. C., Yuan, Y., Forman, D., Hunt, R. & Moayyedi, P. Helicobacter pylori eradication for the prevention of gastric neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 7(7), Cd005583 (2020).

Kesharwani, A., Dighe, O. R. & Lamture, Y. Role of helicobacter pylori in gastric carcinoma: A review. Cureus 15(4), e37205 (2023).

Purkait, S. et al. Elevated expression of dna methyltransferases and enhancer of zeste homolog 2 in helicobacter pylori—Gastritis and gastric carcinoma. Digestive Dis. 40(2), 156–167 (2022).

Piscione, M., Mazzone, M., Di Marcantonio, M. C., Muraro, R. & Mincione, G. Eradication of helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: A controversial relationship. Front. Microbiol. 12, 630852 (2021).

Santos, M. L. C. et al. Helicobacter pylori infection: Beyond gastric manifestations. World J. Gastroenterol. 26(28), 4076–4093 (2020).

Takeuchi, C. et al. Precancerous nature of intestinal metaplasia with increased chance of conversion and accelerated DNA methylation. Gut 73(2), 255–267 (2024).

Liao, X. et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation and transcriptomic patterns of precancerous gastric cardia lesions. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 116(5), 681–693 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Aberrant DNA methylation and expression of EYA4 in gastric cardia intestinal metaplasia. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. Off. J. Saudi Gastroenterol. Assoc. 28(6), 456–465 (2022).

Krishnan, V. et al. DNA damage signalling as an anti-cancer barrier in gastric intestinal metaplasia. Gut 69(10), 1738–1749 (2020).

Kim, H. J. et al. Methylation of the CDX2 promoter in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric mucosa increases with age and its rapid demethylation in gastric tumors is associated with upregulated gene expression. Carcinogenesis 41(10), 1341–1352 (2020).

Li Y: Study on the expression and methylation of ELMO1 in gastric cancer. Master. 2022.

Garg, J. et al. The Med31 conserved component of the divergent mediator complex in tetrahymena thermophila participates in developmental regulation. Curr. Biol. CB 29(14), 2371-2379.e2376 (2019).

Beadle, E. P., Straub, J. A., Bunnell, B. A. & Newman, J. J. MED31 involved in regulating self-renewal and adipogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 45(5), 1545–1550 (2018).

Risley, M. D., Clowes, C., Yu, M., Mitchell, K. & Hentges, K. E. The Mediator complex protein Med31 is required for embryonic growth and cell proliferation during mammalian development. Dev. Biol. 342(2), 146–156 (2010).

Mauldin, J. P. et al. A link between the cytoplasmic engulfment protein Elmo1 and the Mediator complex subunit Med31. Curr. Biol. CB 23(2), 162–167 (2013).

Tocci, S., Ibeawuchi, S. R., Das, S. & Sayed, I. M. Role of ELMO1 in inflammation and cancer-clinical implications. Cell. Oncol. 45(4), 505–525 (2022).

Jiang, J., Liu, G., Miao, X., Hua, S. & Zhong, D. Overexpression of engulfment and cell motility 1 promotes cell invasion and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp. Ther. Med. 2(3), 505–511 (2011).

Peng, C. et al. A novel plasma-based methylation panel for upper gastrointestinal cancer early detection. Cancers 14(21), 5282 (2022).

Pei, B. et al. Identifying potential DNA methylation markers for the detection of esophageal cancer in plasma. Front. Genet. 14, 1222617 (2023).

Xue, Y. et al. The signature of cancer methylation markers in maternal plasma: Factors influencing the development and application of cancer liquid biopsy assay. Gene 906, 148261 (2024).

Martinelli, G. et al. Investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying early response to inflammation and helicobacter pylori infection in human gastric epithelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(20), 15147 (2023).

Tang, D. et al. Microenvironment-confined kinetic elucidation and implementation of a DNA nano-phage with a shielded internal computing layer. Nat. Commun. 16(1), 923 (2025).

Chen, X. et al. Identification of FCN1 as a novel macrophage infiltration-associated biomarker for diagnosis of pediatric inflammatory bowel diseases. J. Transl. Med. 21(1), 203 (2023).

Chanput, W., Mes, J. J. & Wichers, H. J. THP-1 cell line: an in vitro cell model for immune modulation approach. Int. Immunopharmacol. 23(1), 37–45 (2014).

Molina-Castro, S. E. et al. The Hippo Kinase LATS2 controls helicobacter pylori-Induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and intestinal metaplasia in gastric mucosa. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9(2), 257–276 (2020).

Deng, M. et al. Helicobacter pylori-induced NAT10 stabilizes MDM2 mRNA via RNA acetylation to facilitate gastric cancer progression. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 42(1), 9 (2023).

Wu, L., Jiang, F. & Shen, X. Helicobacter pylori caga protein regulating the biological characteristics of gastric cancer through the miR-155–5p/SMAD2/SP1 axis. Pathogens 11(8), 846 (2022).

Lin, M. et al. Increased ONECUT2 induced by Helicobacter pylori promotes gastric cancer cell stemness via an AKT-related pathway. Cell Death Dis. 15(7), 497 (2024).

Sung, J. J. Y. et al. Gastric microbes associated with gastric inflammation, atrophy and intestinal metaplasia 1 year after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gut 69(9), 1572–1580 (2020).

Liang, X. et al. Helicobacter pylori promotes gastric intestinal metaplasia through activation of IRF3-mediated kynurenine pathway. Cell Commun. Signal 21(1), 141 (2023).

Kim, H. J. et al. Promising aberrant DNA methylation marker to predict gastric cancer development in individuals with family history and long-term effects of H pylori eradication on DNA methylation. Gastric Cancer Off. J. Int. Gastric Cancer Assoc. Jpn. Gastric Cancer Assoc. 24(2), 302–313 (2021).

Kim, J. L., Kim, S. G., Natsagdorj, E., Chung, H. & Cho, S. J. Helicobacter pylori eradication can reverse rho gtpase expression in gastric carcinogenesis. Gut Liver 17(5), 741–752 (2023).

Wang, Y., Xu, X., Pan, M. & Jin, T. ELMO1 directly interacts with Gβγ subunit to transduce GPCR signaling to Rac1 activation in chemotaxis. J. Cancer 7(8), 973–983 (2016).

Hu, X. et al. Glutamine metabolic microenvironment drives M2 macrophage polarization to mediate trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive gastric cancer. Cancer Commun. 43(8), 909–937 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. M2 tumor-associated macrophages-derived exosomal MALAT1 promotes glycolysis and gastric cancer progression. Adv. Sci. 11(24), e2309298 (2024).

Deng, C. et al. Exosome circATP8A1 induces macrophage M2 polarization by regulating the miR-1-3p/STAT6 axis to promote gastric cancer progression. Mol. Cancer 23(1), 49 (2024).

Peng, R. et al. M2 macrophages participate in ILC2 activation induced by Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut microbes 16(1), 2347025 (2024).

Yang, T. et al. Berberine regulates macrophage polarization through IL-4-STAT6 signaling pathway in Helicobacter pylori-induced chronic atrophic gastritis. Life Sci. 266, 118903 (2021).

Zhu, T. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote gastric cancer metastasis by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Int. J. Mol. Med. 48(1), 127 (2021).

Li, D. et al. Heterogeneity and plasticity of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in cancer metastasis: Focusing on partial EMT and regulatory mechanisms. Cell Prolif. 56(6), e13423 (2023).

Li, W. et al. Gastric cancer-derived mesenchymal stromal cells trigger M2 macrophage polarization that promotes metastasis and EMT in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 10(12), 918 (2019).

Zhou, X. et al. Histone deacetylase 8 inhibition prevents the progression of peritoneal fibrosis by counteracting the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and blockade of M2 macrophage polarization. Front. Immunol. 14, 1137332 (2023).

Huang, L. M. & Zhang, M. J. Kinesin 26B modulates M2 polarization of macrophage by activating cancer-associated fibroblasts to aggravate gastric cancer occurrence and metastasis. World J. Gastroenterol. 30(20), 2689–2708 (2024).

Funding

This study was supported by the Shenzhen Nanshan District Health and Health System Science and Technology Major Project (No. NSZD2023060).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tianyu Lu contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and writing-original draft. Tingting Yu and Cheng He contributed to the formal analysis, software, and validation. Boyan Huang, Fang Wang, and Liang Zhang contributed to the methodology and data interpretation. Jian Song contributed to the conceptualization, writing- review and editing, and funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of Southern University of Science and Technology Hospital, approval number (SUSTech-JY202303041).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, T., Yu, T., He, C. et al. Interaction between ELMO1 DNA methylation and Med31 promotes H. pylori-induced gastric cancer EMT and intestinal metaplasia via M2 polarization. Sci Rep 16, 5201 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35314-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35314-x