Abstract

Heat shock poses a major threat to strawberry production, impairing both yield and fruit quality. This study investigated the potential of salicylic acid (SA) spraying (1 mM) to mitigate heat-induced damage (42 °C) in ‘Camarosa’ and ‘Paros’ cultivars. Results showed heat shock was the primary factor driving a severe decline in fruit yield by 61%. Although SA failed to mitigate yield loss, it induced divergent, cultivar-specific strategies in biomass partitioning and defense metabolism. ‘Camarosa’ deployed an inducible, high-cost acclimation strategy, upregulating PAL activity by 56.3% and reconfiguring biomass towards roots, whereas ‘Paros’ exhibited constitutive tolerance but greater fruit weight sensitivity (34.3% vs. 15.6% reduction). PCA quantified a fundamental physiological trade-off, with PC1 (45.5% of variance) clearly separating a yield and quality cluster from a cluster defined by phenylpropanoid metabolism. This was statistically underpinned by significant negative correlations between PAL activity and both fruit yield (r = −0.63) and vitamin C (r = −0.83), confirming the metabolic cost of phenylpropanoid defense activation. It is concluded that 1 mM SA does not rescue yield but serves as a genotype-specific physiological modulator, indicating that management strategies should prioritize cultivars that balance defense expenditure with reproductive sink strength.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

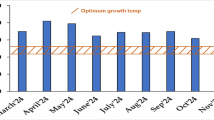

The strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) is a high-value horticultural crop of the Rosaceae family, with considerable global socioeconomic importance due to its appealing taste, distinct aroma, and high nutritional and medicinal value. The fruit is rich in vitamins, minerals, and bioactive compounds such as antioxidants, which contribute to its health benefits1,2. Optimal temperatures for strawberry cultivation are critically defined; reproductive development is most successful between 10 and 26 °C, while vegetative growth accelerates at 25–30°C3,4,5,6,7. However, when temperatures exceed this optimal range (above 30°C), the plant becomes highly vulnerable to heat stress. This vulnerability manifests as oxidative damage from reactive oxygen species (ROS) overproduction, reduced photosynthetic efficiency, and altered membrane permeability, ultimately leading to lower fruit set, smaller fruit size, diminished yield, and reduced profitability1,3,4,5,7,8,9,10,11. Nonetheless, Kesici et al.12 and Ledesma and Kawabata5 noted that there are differences among strawberry cultivars regarding their tolerance to heat stress.

Heat shock, defined as a sudden increase of 10–15 °C above the ambient temperature, is an acute stress event that many plants encounter at least once in their life cycle. It can decrease crop yields by up to 40% by inducing pollen and ovule sterility, triggering flower and fruit abscission, and reducing fruit set5,13,14. To cope with heat stress, plants deploy a range of strategies, including morphological adjustments, physiological and biochemical alterations, and the synthesis of protective compounds14,15. A critical component of this response is the rapid induction of the phenylpropanoid pathway, which is initiated by the key enzyme phenylalanine ammonia-lyase13. This pathway channels carbon towards the synthesis of a wide array of phenolic compounds, lignins, and flavonoids that play crucial roles in enhancing cell wall integrity and acting as antioxidants16. However, this defense activation is metabolically expensive, frequently resulting in a physiological trade-off where resources are diverted from growth and reproductive processes toward survival mechanisms17. This trade-off is a central, yet complex, aspect of plant stress biology.

Several reports indicate that plant growth regulators like salicylic acid (SA) can mitigate the negative effects of heat stress18,19,20. SA (hydroxybenzoic acid), a phenolic phytohormone, acts as an antioxidant and a central signaling molecule in plant defense, regulating processes including growth, development, and thermotolerance21,22,23. Its application has been linked to improved heat tolerance and fruit quality in species such as cucumber24, mango25, ‘Kyoho’ grapevines26, tomato27. Furthermore, SA treatment has been shown to enhance strawberry tolerance to drought28, salinity29,30,31, and low temperatures32. However, the efficacy of SA whether as a mitigator or a modulator is highly context-dependent, varying with concentration, application method, species, and most critically, genotype33. This variability necessitates cultivar-specific investigations, particularly regarding its role in the physiological trade-offs induced by acute heat shock.

In the southern Kerman Province (Jiroft), Iran, ‘Camarosa’ and ‘Paros’ are the dominant commercial strawberry cultivars grown in greenhouses during autumn and winter. A major production challenge in this region arises from recurrent power outages that deactivate greenhouse cooling systems, intermittently exposing plants to heat shock, particularly at the beginning and end of the production cycle. This adversely affects growth and yield, threatening local profitability. While SA has demonstrated protective effects in strawberries against other stresses, its role in modulating the physiological responses and trade-offs induced by acute heat shock remains unclear. Therefore, this study aimed to conduct a comprehensive, multifactorial assessment of how SA modifies the growth, fruit quality, yield, and defense metabolism of ‘Camarosa’ and ‘Paros’ strawberries under heat shock, with a specific focus on elucidating cultivar-specific strategies.

Materials and methods

Plant resources and cultivation conditions

Uniform, healthy, and disease-free plants of the ‘Paros’ and ‘Camarosa’ strawberry cultivars, with a crown diameter of 10–12 mm and 4–5 leaves, were obtained from a commercial greenhouse. Plants were cultivated individually in four-liter pots filled with sand and placed in the research greenhouse at the University of Jiroft. They were maintained under controlled conditions with a temperature regime of 25/20 °C (Day/Night) and a relative humidity of 70 ± 5%. Standard intercultural operations were performed uniformly for all plants; this included the removal of initial inflorescences to promote vegetative growth until the stage of six fully developed leaves, alongside routine pest management as needed. Throughout the experimental period, plants were irrigated five times daily via a drip irrigation system using a modified Hoagland nutrient solution34.

Salicylic acid and heat shock treatments

SA treatments (control and 1 mM) were administered four weeks after the establishment of the plants. The level of SA was selected based on earlier research29,31,35,36. SA (ortho-hydroxybenzoic acid, Sigma Aldrich, USA) was initially dissolved in a few drops of 96% ethanol before being brought to the final 1 mM concentration with distilled water. The foliar application of SA solution was conducted twice with a 7-day interval, utilizing a handheld sprayer on both leaf surfaces until run-off, ensuring complete coverage of all leaves, while the control group of plants was treated with a solution that had an equivalent final concentration of ethanol in distilled water28,32,34.

One week following the second SA treatment, strawberry plants underwent a single continuous 8-h acute heat shock at 42 °C within a controlled environment chamber. The temperature was incrementally increased (5 °C each hour) until it reached 42 °C. Environmental conditions were regulated and observed during the 8-h stress duration with a digital thermostat (SHIVA AMVAJ, Model: TRB-125D) and humidity meter (SHIVA AMVAJ, Model: HMB-1RH), with data logged every 15 min to maintain consistency34. The heat shock temperature was selected based on earlier research by Ledesma37, Ledesma and Kawabata5, Ergin et al.4, and Aghdam et al.9 who established 42 °C as a reliable temperature to induce acute heat shock in strawberry. Following the heat shock treatment, strawberry plants were placed under controlled conditions (25/20 °C Day/Night) similar to those of the control group.

Assessment of growth parameters

Sampling was performed to evaluate growth characteristics four weeks after the application of the heat shock treatment. Plants were carefully extracted from the planting medium, and measurements of root length and plant height (from the soil surface to the top of the canopy) were obtained using a ruler. Additionally, the fresh and dry weights of both shoots and roots were determined, and the ratios of shoot to root biomass were calculated for both fresh and dry weights.

Assessment of yield component and yield

Fully matured fruits were collected gradually, and once moved to the laboratory, their morphological and biochemical traits were assessed. The quantity of mature fruits per plant was systematically documented over time. Fruit weight was measured utilizing a digital scale with a precision of 0.0001 g, while the length and diameter of each fruit were assessed using a digital caliper with an accuracy of 0.01 cm. Subsequently, the number of fruits per plant was recorded, and the total fruit weight per plant was computed to determine the overall yield.

Assessment of fruits quality

Titratable acidity (TA)

Titratable acidity (TA) was determined by titrating a diluted fruit juice sample (1:1 with distilled water) with 0.1 N sodium hydroxide (NaOH) to an endpoint of pH 8.2. The TA was calculated based on the volume of NaOH consumed and is expressed as a percentage of citric acid using the formula38:

where V is the volume (mL) of NaOH consumed, and 0.064 is the milliequivalent weight of citric acid.

Total soluble solid (TSS)

The content of total soluble solids (TSS) in the fruit juice was determined using a digital refractometer (Wikink, Model DR102).

Flavor index

The flavor index, where a higher value signifies the fruit’s sweetness, was derived from the subsequent equation:

Vitamin C

The vitamin C (ascorbic acid) content of the fruit juice was quantified using an iodometric titration method, as described by Seyedi and Afsharipour39. In this reaction, 1 mL of a 0.01 N iodine solution is stoichiometrically equivalent to 0.88 mg of ascorbic acid. Briefly, a 10 mL aliquot of juice was diluted with 20 mL of distilled water, and 2.5 mL of starch solution was added as an indicator. The solution was titrated with a standardized 0.01 N iodine solution until a persistent gray-blue endpoint was reached. The vitamin C concentration was calculated using the following formula and expressed as mg per 100 mL of juice:

where Vt is the volume of iodine titrant consumed (mL); Vj is the volume of the fruit juice sample (mL); and 0.88 is the mass of ascorbic acid (mg) neutralized by 1 mL of 0.01 N iodine solution.

Assessment of physiological and biochemical parameters

Total chlorophyll

The method described by Lichtenthaler and Buschmann40 was utilized to evaluate total chlorophyll. Fully matured leaves (0.02 g) were ground in liquid nitrogen and mixed with ethanol to homogenize. After centrifugation, absorbance readings were taken at 648.6, and 664.1 nm using a spectrophotometer (Dynamica, HALO XB-10, UK), and quantification was carried out employing a known equation:

Enzyme activity

Two weeks after the heat shock treatment, newly developed, fully expanded leaves were sampled, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored for enzyme analysis. Enzyme extraction followed a modified protocol from Zhang and Kirkham41, in which 200 mg of leaf tissue was homogenized in liquid nitrogen and combined with a cold potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0) containing 1 mM EDTA and 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone. The resulting homogenate was centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected for subsequent enzyme activity assays.

Polyphenol oxidase (PPO)

The action of the polyphenol oxidase (PPO) enzyme was evaluated by determining absorbance at 420 nm, applying an extinction coefficient of 2.47 mM−1 cm−1 for purpurogallin, in accordance with Kar and Mishra42 method with minor modifications. The mixture for the reaction contained 3 mL of 25 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) along with 10 mM pyrogallol. Absorbance was measured for three minutes following the addition of a suitable quantity of enzyme extract, with the activity indicated in units producing one mM of purpurogallin per minute.

Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL)

The activity of the phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) enzyme is defined by converting phenylalanine to trans-cinnamic acid. Mixing 1000 µL of 50 mM extraction buffer at a pH of 8.8 containing 15 mM of β-mercaptoethanol with 500 µL of 10 mM L-phenylalanine, 400 µL of double-distilled water, and 100 µL of enzyme extract. The mixture was then left to incubate at 37 °C for 1 h. Afterwards, the reaction is stopped by adding 500 µL of 6 M HCl. Finally, the resulting solution is mixed with 15 mL of ethyl acetate and then evaporated to eliminate the extracting solvent. The remaining solid was dissolved in 3 mL of 0.05 M NaOH, and the quantity of cinnamic acid was determined using the absorbance at 290 nm. One PAL activity unit is equivalent to producing one µmol of cinnamic acid per minute43.

Statistical analysis

The research employed a factorial experimental design (2 × 2 × 2) with four repetitions, carried out in a completely randomized design (CRD). The experimental factors included: (1) cultivars, (2) SA concentrations, and (3) heat shock conditions. Data collection was followed by statistical examination using analysis of variance (ANOVA) performed with JMP 17 software, created by SAS Institute, Cary, NC. When the F test showed significant differences, the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test was used to compare treatment means at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05. Moreover, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated and illustrated with correlation plots created to assess the strength and direction of linear relationships among the measured parameters. Additionally, principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted to identify essential variables that influence the observed variability.

Results

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) results

A three-way analysis of variance revealed significant Cultivar × SA × Heat Shock (C × S × H) interactions for root length and PPO activity, alongside significant two-way interactions: Cultivar × Heat Shock (C × H) for plant height, shoot-to-root ratio, fruit weight, fruit diameter, vitamin C, TSS, flavor index, and PAL activity; Cultivar × SA (C × S) for biomass partitioning, vitamin C content, and PAL activity; and SA × Heat Shock (S × H) for plant height, fruit diameter, titratable acidity, and flavor index (Table S1). These interactions confirmed that genotypic background and SA application critically modulated the plant’s response to thermal stress. Collectively, the analysis established heat stress as the primary single factor, significantly influencing most morphological, yield, and biochemical traits of strawberry cultivars (p ≤ 0.01).

Growth and biomass partitioning

The morphological response of two strawberry cultivars (‘Camarosa’ and ‘Paros’) to heat shock and SA spraying revealed a complex interplay between these factors. Exposure to 42 °C induced a significant increase in plant height in both cultivars; however, a significant C × H interaction (p ≤ 0.01) revealed that ‘Camarosa’ was more susceptible to this elongation, exhibiting a 35% increase compared to an 18% increase in ‘Paros’ (Table 1). Results showed that the role of SA was context-dependent on plant height, while its application under controlled temperatures (25/20 °C Day/Night) had a minimal effect; a significant S × H interaction (p ≤ 0.05) was observed under stress conditions. In the absence of SA, heat shock increased plant height by 18.8% (Table 2). Notably, plants pre-treated with SA and subjected to heat shock showed a further 9.9% increase in height compared to stressed plants without SA, indicating that SA potentiated the heat-induced elongation response.

Furthermore, a significant three-way C × S × H interaction (p ≤ 0.05) indicated genotype-specific strategies for root architecture in response to heat shock. In ‘Paros’, heat shock led to an insignificant (9.4%) decrease in root length at the control level of SA, while in ‘Camarosa’, it led to a 22.73% rise (Fig. 1a). The use of SA under heat shock conditions increased root length by 18.5% and 16.5% in ‘Paros’ and ‘Camarosa’, respectively. Additionally, at the control level of SA, root length in ‘Camarosa’ under heat shock conditions was 52.8% greater than that of the ‘Paros’ cultivar.

The interaction effect of heat shock, salicylic acid (SA) treatments on root length (a) and PPO; Polyphenol oxidase (b) were evaluated across two strawberry cultivars, ‘Paros’ and ‘Camarosa’. Treatments showing no significant differences are marked with the same letters according to the LSD test (p ≤ 0.05), and values are represented as mean ± standard error.

A significant cultivar-specific response to stress was observed for biomass partitioning. Heat shock induced a pronounced shift toward root allocation in ‘Camarosa’, evidenced by a 29% and 19.5% decrease in the fresh and dry shoot-to-root ratios, respectively (Table 1). Conversely, ‘Paros’ exhibited stability, with no significant change in the fresh weight ratio and only a marginal increase in the dry weight ratio, suggesting a constitutive stress tolerance. On the other hand, SA application induced a significant C × S interaction, revealing divergent biomass partitioning strategies in strawberry cultivars. The 1 mM SA treatment prompted ‘Camarosa’ to favor shoot investment, significantly increasing its shoot-to-root dry and fresh weight ratios by 38% and 12%, respectively (Table 3). In stark contrast, ‘Paros’ exhibited a shift toward root investment, with its shoot-to-root fresh weight ratio decreasing significantly by 27.6%. This clear antagonistic response underscores a fundamental, genotype-specific effect of SA spraying on resource allocation.

Yield and fruit dimensions

Reproductive output was consistently and severely impaired by heat shock, regardless of cultivar or SA application. Findings indicated that, heat shock led to a 50.5% reduction in fruit number (Fig. 2a) and a 61% reduction in fruit yield (Fig. 2b) compared to control conditions. The absence of significant interactions for these traits underscores a fundamental, pervasive vulnerability in the strawberry reproductive system to high-temperature stress.

Effect of heat shock on the number of fruits (a), fruit yield (b), fruit length (c) and total chlorophyll (d) of the strawberry plant. Treatments showing no significant differences are marked with the same letters according to the LSD test (p ≤ 0.05), and values are represented as mean ± standard error.

A significant C × H interaction (p ≤ 0.01) for fruit weight revealed differential genetic sensitivity to the stress. While fruit weights were statistically equivalent between ‘Camarosa’ (14.75 g) and ‘Paros’ (13.40 g) under control conditions (Table 1), heat shock caused a significantly more severe reduction in ‘Paros’ (34.3% decrease) than in ‘Camarosa’ (15.6% decrease). As illustrated in Fig. 3a, ‘Camarosa’ had a significantly greater fruit length (38.94 mm) compared to ‘Paros’ (30.06 mm). Nevertheless, heat shock led to a significant decrease (25%) in this key fruit dimension (Fig. 2c).

Significant C × H interactions were found for fruit diameter, although both cultivars had similar fruit diameters under control conditions (Table 1), ‘Paros’ exhibited a more severe reduction (34.5%) under stress. A significant S × H interaction also indicated that SA application reduced fruit diameter (11.05%) under control temperature (Table 2).

Fruit biochemical quality

Fruit biochemistry was significantly altered by heat shock. It alone significantly reduced TA by 27%, in the absence of SA (Table 2). This was the key factor behind a sharp increase in the flavor index (TSS/TA), which was significantly more pronounced in ‘Camarosa’ (86.8% increase) than in ‘Paros’ (22.5% increase) (Table 1). SA also influenced these parameters, reducing TA under control conditions and, via a significant S × H interaction, increasing the flavor index in the absence of stress (Table 2). Moreover, as shown in Table 1, TSS increased significantly due to the heat shock, particularly in ‘Camarosa’ (56%). In stark contrast, vitamin C content was severely reduced by heat, with ‘Camarosa’ again being more affected (50% decrease vs. 32% in ‘Paros’). The effect of SA on vitamin C was cultivar-dependent, causing a significant decrease (17.5%) in ‘Camarosa’ but a slight, non-significant increase (5.2%) in ‘Paros’ (Table 3).

Physiological and defense-related metabolism

A significant main effect of heat stress (p ≤ 0.01) severely reduced the total chlorophyll content (Fig. 2d), with ‘Camarosa’ maintaining a higher baseline level than ‘Paros’ (Fig. 3b). SA application demonstrated no significant capacity to alleviate this heat-induced chlorophyll loss under the experimental conditions (Table S1).

The enzymatic stress responses revealed fundamental differences between the cultivars. PAL activity was significantly upregulated by heat stress in both cultivars (Table 1), but the induction was stronger in ‘Camarosa’ (56.3% increase) than in ‘Paros’ (28.8%). Furthermore, a key modulatory effect of SA was observed in the phenylpropanoid pathway. SA application triggered a significant 11.85% increase in PAL activity only in ‘Paros’, bringing it to a level equivalent to ‘Camarosa’ (Table 3). A more complex, cultivar-specific pattern was observed for PPO. In ‘Paros’, heat shock alone provoked a strong 33.5% increase in PPO activity, which was completely suppressed by SA pretreatment (Fig. 1b). In stark contrast, in ‘Camarosa’, PPO activity remained stable and unresponsive to both heat stress and SA.

Correlation analysis

Correlation analysis using the combined data from all treatment groups elucidated the key physiological interrelationships governing the response to our treatments, revealing a fundamental trade-off between reproductive investment and stress acclimation. A strong, positive cluster integrated morphological, fruit yield, and quality traits, whereas a distinct cluster was defined by the key enzyme of the phenylpropanoid pathway, PAL. As illustrated in Fig. 4, fruit weight was strongly correlated with fruit dimensions (Length: r = 0.98; Diameter: r = 0.96), and fruit number was the primary driver of total fruit yield per plant (r = 0.97). Notably, vitamin C content was positively linked to this cluster, showing significant correlations with fruit weight (r = 0.55), fruit diameter (r = 0.59), and total chlorophyll (r = 0.56), suggesting that vigorous photosynthetic capacity and fruit development are coupled with high nutritional quality. On the other hand, a distinct stress physiology cluster emerged, centered on the defense enzyme PAL. The activity of PAL was strongly positively correlated with the flavor index (r = 0.76) and exhibited significant negative correlations with fruit yield (r = −0.63) and vitamin C (r = −0.83). This robust inverse relationship statistically confirms a physiological cost, whereby the upregulation of this defense pathway occurs at the direct expense of biomass partitioning and nutrient accumulation in fruits. This trade-off was further underscored by the relationship of plant height, which increased under stress. Plant height was positively correlated with PAL (r = 0.75) and negatively correlated with vitamin C (r = −0.77), reinforcing that heat-induced vegetative growth is part of a stress response syndrome associated with diminished fruit quality.

Correlation coefficients was conducted to examine the relationships between treatments (heat shock and salicylic acid, and cultivar), in relation to various morphological, physiological, and biochemical parameters of strawberry. Shades of red indicate positive correlations, while shades of blue represent negative correlations. The parameters analyzed included plant height (PH), root length (RL), fresh weight ratios of shoot to root (Sh/root fw), dry weight ratios of shoot to root (Sh/root dw), number of fruits (NF), fruit length (FD), fruit diameter (FD), fruit weight (FWe), fruit yield (PY), vitamin C concentration (Vit C), total soluble solids (TSS), titratable acidity (TA), flavor index (TSS/TA), total chlorophyll content (T CHL), polyphenol oxidase activity (PPO) and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activity (PAL).

Principal component analysis (PCA)

PCA was conducted on the combined dataset to visualize the interrelationships among 16 reproductive and physiological traits and the overarching effects of cultivar, SA, and heat shock. The first two principal components (PCs) captured 60.8% of the total variance, with PC1 alone explaining 45.5% (Fig. 5). PC1 was defined as a yield and fruit quality axis, being strongly and positively associated with fruit weight, dimensions, fruit yield, vitamin C, and total chlorophyll, and negatively with stress-related traits (PAL, TSS/TA). PC2 (15.3% of variance) revealed a trade-off between vegetative growth and fruit size (positive loadings for root length, plant height, fruit weight, and dimensions) and oxidative stress (negative loading for PPO), framing it as a vegetative growth vs. oxidative stress axis.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) biplot of reproductive and physio-biochemical traits in strawberry cultivars under heat shock and salicylic acid treatments. The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) explain 60.8% of the total variance (PC1: 45.5%; PC2: 15.3%). Blue points represent treatment group means, distinguished by cultivar (‘Camarosa’ vs. ‘Paros’), salicylic acid application (0 mM vs. 1 mM), and thermal stress (Control vs. Heat Shock). Variable vectors (red arrows) indicate the direction and strength of trait contributions to the principal components. The green dots represent individual experimental replicates. The parameters analyzed included plant height (PH), root length (RL), fresh weight ratios of shoot to root (Sh/root fw), dry weight ratios of shoot to root (Sh/root dw), number of fruits (NF), fruit length (FL), fruit diameter (FD), fruit weight (FWe), fruit yield (PY), vitamin C concentration (Vit C), total soluble solids (TSS), titratable acidity (TA), flavor index (TSS/TA), total chlorophyll content (T CHL), polyphenol oxidase activity (PPO) and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activity (PAL).

The projection of treatments and cultivars onto the biplot revealed distinct patterns (Fig. 5). A stark contrast separated the two cultivars: ‘Camarosa’ was associated with high yield, large fruit size, high vitamin C, and strong vegetative growth, while ‘Paros’ exhibited an opposing phenotypic profile linked to higher stress markers. Heat shock was the most influential factor, drastically shifting the phenotypic profile from a high positive score on PC1 (Control: + 2.35) to a strong negative score (Heat Shock: −2.35), confirming it as the primary driver of the severe decline in yield and fruit quality. Furthermore, SA application induced a significant shift along PC1, clearly separating SA-treated from non-treated groups and underscoring its role as a modulator of the plant’s physiological state under the experimental conditions.

Discussion

This study elucidates the complex interplay between genotype and phytohormonal signaling in modulating strawberry responses to acute heat stress. While heat shock was the dominant factor reducing performance overall, our results clearly demonstrate that the two cultivars examined, ‘Camarosa’ and ‘Paros’, exhibited distinct vulnerabilities. The data compellingly shows that ‘Paros’ is more sensitive to heat shock than ‘Camarosa’ in terms of reproductive output.

The most compelling finding is the fundamental trade-off between reproductive investment and phenylpropanoid defense system, crystallized by the PCA and correlation analysis. The stark opposition on PC1 between a yield and fruit quality cluster and a stress physiology cluster (centered on PAL activity) provides a multivariate framework for our results. This aligns with the classic ecological concept of the growth-differentiation balance hypothesis, which posits that plants cannot simultaneously maximize production and resource-intensive differentiation processes (here, phenylpropanoid compound synthesis)44,45,46. The strong negative correlation between PAL and vitamin C (r = −0.83) statistically validates this metabolic cost. PAL is the gateway enzyme into the phenylpropanoid pathway, which produces a wide array of phenolic compounds, lignin, and flavonoids crucial for stress tolerance13,47. The upregulation of PAL under heat shock, as observed here and in other species like tomato48,49 and olive50, demands carbon skeletons and energy (ATP/NADH) that are likely diverted from the biosynthesis of primary metabolites like vitamin C (ascorbic acid) and the development of fruit sinks. This resource reallocation explains the drastic collapse in yield and quality under heat stress, as the plant prioritizes survival via the phenylpropanoid pathway over reproduction. Furthermore, the severe depletion of vitamin C (quantified as the total ascorbate pool) underscores the immense oxidative pressure of heat stress, as the ascorbate–glutathione cycle is a major consumer of ascorbate under reactive oxygen species (ROS) burden51.

The two cultivars, ‘Camarosa’ and ‘Paros’, embody distinct physiological strategies. ‘Camarosa’ exhibits a phenotype consistent with an active, resource-intensive heat-avoidance/acclimation strategy. The significant hyper-increasing of its height is a classic shade-avoidance response often mediated by thermosensitive phytochromes and auxin signaling52. The pronounced shift in biomass partitioning towards the root system is a well-documented adaptive response to improve water foraging capacity under abiotic stress53. This morphological plasticity is underpinned by a robust biochemical response, evidenced by the strong upregulation of PAL47. This activation of the phenylpropanoid pathway likely contributes to the observed relative resilience of ‘Camarosa’s fruit weight. However, this comes at a substantial metabolic cost, as revealed by the strong negative correlation between PAL activity and yield/vitamin C, confirming a resource-based trade-off between growth and this specific defense pathway17. In contrast, ‘Paros’ displays a phenotype of limited morphological plasticity, maintaining stable biomass partitioning under stress. This suggests a reliance on pre-formed, constitutive defense mechanisms rather than induced phenylpropanoid responses, which aligns with studies in other crops where stress-resilient genotypes often show less dramatic physiological shifts and maintain greater homeostasis54. However, this strategy proves inadequate for protecting reproductive development. The significantly greater reduction in individual fruit weight and dimensions in ‘Paros’ indicates a higher sensitivity of its fruit sink strength to heat shock. The distinct and strong induction of PPO in ‘Paros’ under heat is particularly telling. PPO activation is often associated with post-stress oxidative damage and the loss of cellular compartmentalization, potentially indicating a failure to fully contain the oxidative burst55.

Heat shock acted as a physiological reset, leading to a widespread decline in reproductive performance. The dramatic inversion along PC1 visually confirms its dominance. It seems that the mechanisms behind this reduction are multifaceted. The severe reduction in total chlorophyll, a common response to heat stress3,56,57, directly limits photosynthetic capacity, reducing the carbon supply for both growth and defense. The increase in TSS, despite this, likely reflects a concentration effect due to water loss58, rather than enhanced sugar import. More critically, heat stress is recognized to directly induce pollen sterility and disrupt fertilization in strawberries59, offering a direct mechanistic rationale for the consistent and substantial decline in both fruit number and yield, factors for which no treatment interactions were able to alleviate the impact of heat shock.

On the other hand, the role of SA was complex and context-dependent, reflecting its known function as a signaling hormone that primes defense responses rather than a direct protectant60. Our finding that SA potentiated heat-induced elongation in both cultivars is novel and suggests an interaction between SA and the hormonal pathways governing cell expansion, possibly through cross-talk with gibberellins or auxins. The diametrically opposite effect of SA on biomass partitioning in the two cultivars is a striking example of genotype-hormone interaction. It is plausible that SA signaling interacts with the fundamental transcriptional regulators of each cultivar’s resource allocation strategy, pushing ‘Camarosa’ further toward its innate shoot-acquisitive tendency and ‘Paros’ toward its root-conservative tendency.

Crucially, SA was able to prime PAL activity in ‘Paros’, a phenomenon where prior exposure to a biotic or chemical agent boosts the plant’s defense ability for a quicker and/or more robust reaction response to subsequent stress61. Its success in suppressing heat-induced PPO in ‘Paros’ is a clear example of effective priming, where pre-treatment alerts the plant’s defense system for a more controlled response62. However, SA’s failure to alleviate chlorophyll loss and its tendency to reduce certain quality traits (e.g., vitamin C in ‘Camarosa’) under control conditions highlights the potential cost of priming the defense system61. The metabolic resources required to maintain the primed state may divert energy from the biosynthesis of compounds like ascorbate, a phenomenon noted in other plant-hormone studies63. The strong negative correlations between the SA and heat-upregulated PAL enzyme and both yield and vitamin C provide the physiological basis for the observed trade-off, confirming that the defense metabolism amplified by SA comes at a direct metabolic cost to reproduction and fruit quality.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this integrative analysis demonstrates that the sensitivity of a crop cultivar to abiotic stress cannot be gauged by a single parameter but must be evaluated across a hierarchy of responses, from metabolic defense to reproductive resilience. ‘Paros’ is identified as the more heat-sensitive cultivar due to its greater reproductive failure, a consequence of its limited capacity for protective morphological plasticity and an ineffective defense response. ‘Camarosa’, despite a higher metabolic cost evidenced by strong trade-offs, employs a more effective, inducible acclimation strategy that confers relative protection to its fruit development. SA functions not as a rescue agent but as a physiological modulator that accentuates cultivar-specific strategies in biomass partitioning and defense enzyme induction, revealing underlying genetic differences in heat stress response. Future breeding for heat resilience in strawberry should therefore select for genotypes with a robust, inducible phenylpropanoid defense system coupled with maintained sink strength in reproductive organs.

Data availability

The data provided in this study can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author. The information is not available to the public.

References

Balasooriya, B., Dassanayake, K. & Ajlouni, S. High temperature effects on strawberry fruit quality and antioxidant contents. In: IV International Conference on Postharvest and Quality Management of Horticultural Products of Interest for Tropical Regions 1278. 225–234.

Arief, M. A. A. et al. Chlorophyll fluorescence imaging for early detection of drought and heat stress in strawberry plants. Plants 12, 1387 (2023).

Kadir, S., Sidhu, G. & Al-Khatib, K. Strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch.) growth and productivity as affected by temperature. HortScience 41, 1423 (2006).

Ergin, S. et al. Effects of high temperature stress on enzymatic and nonenzymaticantioxidants and proteins in strawberry plants. Turk. J. Agric. For. 40, 908–917 (2016).

Ledesma, N. A. & Kawabata, S. Responses of two strawberry cultivars to severe high temperature stress at different flower development stages. Sci. Hortic. 211, 319–327 (2016).

Dash, P. K., Chase, C. A., Agehara, S. & Zotarelli, L. Heat stress mitigation effects of kaolin and s-abscisic acid during the establishment of strawberry plug transplants. Sci. Hortic. 267, 109276 (2020).

Ullah, I. et al. High-temperature stress in strawberry: Understanding physiological, biochemical and molecular responses. Planta 260, 118 (2024).

Muneer, S., Park, Y. G., Kim, S. & Jeong, B. R. Foliar or subirrigation silicon supply mitigates high temperature stress in strawberry by maintaining photosynthetic and stress-responsive proteins. J. Plant Growth Regul. 36, 836–845 (2017).

Aghdam, O. A., Hajilou, J., Bolandnazar, S. & Dehghan, G. Effect Of 24-Epi brassinolide on some BiochemicalCharacteristics of parus and gaviota strawberry cultivars under heat stress conditions. Yuzuncu Yıl Univ J Agric Sci 30, 429–437 (2020).

Manafi, H., Baninasab, B., Gholami, M., Talebi, M. & Khanizadeh, S. Exogenous melatonin alleviates heat-induced oxidative damage in strawberry (Fragaria× ananassa Duch. Cv. Ventana) Plant. J Plant Growth Regul 41, 52–64 (2022).

Shirdel, M., Eshghi, S., Shahsavandi, F. & Fallahi, E. Arbuscular mycorrhiza inoculation mitigates the adverse effects of heat stress on yield and physiological responses in strawberry plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 221, 109629 (2025).

Kesici, M. et al. Heat-stress tolerance of some strawberry (Fragaria× ananassa) cultivars. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 41, 244–249 (2013).

Wahid, A., Gelani, S., Ashraf, M. & Foolad, M. R. Heat tolerance in plants: an overview. Environ. Exp. Bot. 61, 199–223 (2007).

Angon, P. B. et al. Plant development and heat stress: Role of exogenous nutrients and phytohormones in thermotolerance. Discover Plants 1, 17 (2024).

Seymour, Z. J., Mercedes, J. F. & Fang, J.-Y. Effect of heat acclimation on thermotolerance of in vitro strawberry plantlets. Folia Hortic 36, 135–147 (2024).

Naikoo M. I. et al. Role and regulation of plants phenolics in abiotic stress tolerance: An overview. Plant signaling molecules, 157–168 (2019).

Huot, B., Yao, J., Montgomery, B. L. & He, S. Y. Growth–defense tradeoffs in plants: A balancing act to optimize fitness. Mol. Plant 7, 1267–1287 (2014).

Shi, Q., Bao, Z., Zhu, Z., Ying, Q. & Qian, Q. Effects of different treatments of salicylic acid on heat tolerance, chlorophyll fluorescence, and antioxidant enzyme activity in seedlings of Cucumis sativa L. Plant Growth Regul. 48, 127–135 (2006).

Wang, L.-J. et al. Salicylic acid alleviates decreases in photosynthesis under heat stress and accelerates recovery in grapevine leaves. BMC Plant Biol. 10, 34 (2010).

Wassie, M. et al. Exogenous salicylic acid ameliorates heat stress-induced damages and improves growth and photosynthetic efficiency in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 191, 110206 (2020).

Nazar, R., Iqbal, N. & Khan, N. A. Salicylic acid: A multifaceted hormone (Springer, Berlin, 2017).

Luo, Y., Liu, M., Cao, J., Cao, F. & Zhang, L. The role of salicylic acid in plant flower development. Forestry Res 2, 14 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. Uncovering the mechanisms of salicylic acid-mediated abiotic stress tolerance in horticultural crops. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1226041 (2023).

Basirat, M. & Mousavi, S. M. Effect of foliar application of silicon and salicylic acid on regulation of yield and nutritional responses of greenhouse cucumber under high temperature. J. Plant Growth Regul. 41, 1978–1988 (2022).

Samad, A. G. A. & Shaaban, A. Fulvic and salicylic acids improve morpho-physio-biochemical attributes, yield and fruit quality of two mango cultivars exposed to dual salinity and heat stress conditions. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 24, 6305–6324 (2024).

Sun, Y. et al. Root-applied brassinosteroid and salicylic acid enhance thermotolerance and fruit quality in heat-stressed ‘Kyoho’grapevines. Front. Plant Sci. 16, 1563270 (2025).

Saleem, W., Khan, M. A. & Akram, M. T. Exogenous application of salicylic acid improves physiochemical and quality traits of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) under elevated temperature stress. Pak. J. Bot 57, 441–449 (2025).

Ghaderi, N., Normohammadi, S. & Javadi, T. Morpho-physiological responses of strawberry (Fragaria× ananassa) to exogenous salicylic acid application under drought stress. (2015).

Karlidag, H., Yildirim, E. & Turan, M. Salicylic acid ameliorates the adverse effect of salt stress on strawberry. Sci Agricola 66, 180–187 (2009).

Roshdy, A.E.-D., Alebidi, A., Almutairi, K., Al-Obeed, R. & Elsabagh, A. The effect of salicylic acid on the performances of salt stressed strawberry plants, enzymes activity, and salt tolerance index. Agronomy 11, 775 (2021).

Lamnai, K. et al. Impact of exogenous application of salicylic acid on growth, water status and antioxidant enzyme activity of strawberry plants (Fragaria vesca L.) under salt stress conditions. Gesunde Pflanzen 73, 465–478 (2021).

Karlidag, H., Yildirim, E. & Turan, M. Exogenous applications of salicylic acid affect quality and yield of strawberry grown under antifrost heated greenhouse conditions. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 172, 270–276 (2009).

Miura, K. & Tada, Y. Regulation of water, salinity, and cold stress responses by salicylic acid. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 4 (2014).

Khajeh Sorkhoeih, M., Hamidi Moghaddam, A. & Seyedi, A. Different biochemical and morphological responses of the strawberry cultivars to salicylic acid and heat shock. BMC Plant Biol. 25, 1208 (2025).

Jamali, B., Eshghi, S. & Kholdebarin, B. Antioxidant responses of ‘Selva’strawberry as affected by salicylic acid under salt stress. J Berry Res 6, 291–301 (2016).

Faghih, S., Ghobadi, C. & Zarei, A. Response of strawberry plant cv.‘Camarosa’to salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate application under salt stress condition. J Plant Growth Regul 36, 651–659 (2017).

Ledesma, N., Kawabata, S. & Sugiyama, N. Effect of high temperature on protein expression in strawberry plants. Biol. Plant. 48, 73–79 (2004).

Noshirvani, N., Alimari, I. & Mantashloo, H. Impact of carboxymethyl cellulose coating embedded with oregano and rosemary essential oils to improve the post-harvest quality of fresh strawberries. J Food Meas Charact 17, 5440–5454 (2023).

Seyedi, A. & Afsharipour, S. Evaluation of some morphological, biochemical and antioxidant properties of some mandarin cultivars. Res Pomol 4, 29–42 (2019).

Lichtenthaler, H. K. & Buschmann, C. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Measurement and characterization by UV-VIS spectroscopy. Curr Protocols Food Anal Chem 1, 31–38 (2001).

Zhang, J. & Kirkham, M. Antioxidant responses to drought in sunflower and sorghum seedlings. New Phytol. 132, 361–373 (1996).

Kar, M. & Mishra, D. Catalase, peroxidase, and polyphenoloxidase activities during rice leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 57, 315–319 (1976).

Wang, J. W., Zheng, L. P., Wu, J. Y. & Tan, R. X. Involvement of nitric oxide in oxidative burst, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activation and Taxol production induced by low-energy ultrasound in Taxus yunnanensis cell suspension cultures. Nitric Oxide 15, 351–358 (2006).

Herms, D. A. & Mattson, W. J. The dilemma of plants: To grow or defend. Q. Rev. Biol. 67, 283–335 (1992).

Hattas, D., Scogings, P. F. & Julkunen-Tiitto, R. Does the growth differentiation balance hypothesis explain allocation to secondary metabolites in Combretum apiculatum, an African savanna woody species?. J. Chem. Ecol. 43, 153–163 (2017).

Ferrenberg, S., Vázquez-González, C., Lee, S. R. & Kristupaitis, M. Divergent growth-differentiation balance strategies and resource competition shape mortality patterns in ponderosa pine. Ecosphere 14, e4349 (2023).

Dixon, R. A. & Paiva, N. L. Stress-induced phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant Cell 7, 1085 (1995).

Rivero, R. M., Ruiz, J. M. & Romero, L. Can grafting in tomato plants strengthen resistance to thermal stress?. J. Sci. Food Agric. 83, 1315–1319 (2003).

Fernández-Crespo, E. et al. Exploiting tomato genotypes to understand heat stress tolerance. Plants 11, 3170 (2022).

Ajani, A., Soleimani, A., Zeinanloo, A. A., Seifi, E. & Taheri, M. Differential display of heat stress tolerance of olive cultivars’ zard’and’direh’based on physiological and biochemical indexes as well as PPO and PAL genes expression pattern. (2021).

Foyer, C. H. & Noctor, G. Ascorbate and glutathione: the heart of the redox hub. Plant Physiol. 155, 2–18 (2011).

Stavang, J. A. et al. Hormonal regulation of temperature-induced growth in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 60, 589–601 (2009).

Poorter, H. et al. Biomass allocation to leaves, stems and roots: Meta-analyses of interspecific variation and environmental control. New Phytol. 193, 30–50 (2012).

Szymańska, R., Ślesak, I., Orzechowska, A. & Kruk, J. Physiological and biochemical responses to high light and temperature stress in plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 139, 165–177 (2017).

Mayer, A. M. Polyphenol oxidases in plants and fungi: Going places?. A review. Phytochemistry 67, 2318–2331 (2006).

Allakhverdiev, S. I. et al. Heat stress: An overview of molecular responses in photosynthesis. Photosynth. Res. 98, 541–550 (2008).

Zahra, N. et al. Plant photosynthesis under heat stress: Effects and management. Environ. Exp. Bot. 206, 105178 (2023).

El-Mogy, M. M., Garchery, C. & Stevens, R. Irrigation with salt water affects growth, yield, fruit quality, storability and marker-gene expression in cherry tomato. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Sect B Soil Plant Sci 68, 727–737 (2018).

Ledesma, N. A., Nakata, M. & Sugiyama, N. Effect of high temperature stress on the reproductive growth of strawberry cvs‘Nyoho’and ‘Toyonoka’. Sci Hortic 116, 186–193 (2008).

Vlot, A. C., Dempsey, D. M. A. & Klessig, D. F. Salicylic acid, a multifaceted hormone to combat disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 47, 177–206 (2009).

Conrath, U. Priming of induced plant defense responses. Adv. Bot. Res. 51, 361–395 (2009).

Khan, M. I. R., Fatma, M., Per, T. S., Anjum, N. A. & Khan, N. A. Salicylic acid-induced abiotic stress tolerance and underlying mechanisms in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 462 (2015).

Walters, D. & Heil, M. Costs and trade-offs associated with induced resistance. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 71, 3–17 (2007).

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to express gratitude to the University of Jiroft for providing the facilities to carry out this research.

Funding

This research did not receive funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M KS was responsible for project implementation and data collection. A HM managed the project, supervised the activities, and wrote the original draft, as well as the Writing – review & editing. A S and A HM performed data analysis and conceptualization. All authors contributed to reviewing and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khajeh Sorkhoeih, M., Hamidi Moghaddam, A. & Seyedi, A. Salicylic acid induces cultivar specific compromises in yield, fruit quality and defense metabolism of heat stressed strawberry. Sci Rep 16, 4874 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35412-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35412-w