Abstract

Immune evasion is a major barrier to effective glioma treatment, yet the molecular drivers contributing to this process remain insufficiently understood. Engrailed-1 (EN1), a developmental transcription factor, has recently emerged as a potential oncogenic regulator, but its role in glioma immune modulation is unclear. This study aimed to comprehensively investigate the function of EN1 in glioma, with a particular focus on its involvement in immune evasion, by integrating bulk and single-cell transcriptomic analyses together with ceRNA regulatory network construction and experimental validation. EN1 expression, diagnostic value, and prognostic significance were assessed using TCGA, GTEx, and CGGA datasets. Immune infiltration and microenvironmental features were evaluated through CIBERSORT, ESTIMATE, and WGCNA. Single-cell RNA-seq data (GSE182109) were used to characterize the cell-type distribution and developmental trajectory of EN1. A NEAT1/miR-9-5p/miR-128-3p/EN1 ceRNA axis was constructed using multi-database predictions. Functional assays including Western blot, CCK-8, and Transwell experiments were performed to validate EN1’s effects in glioblastoma cells. EN1 was markedly overexpressed in glioma and associated with poorer survival. Elevated EN1 expression correlated with increased infiltration of immunosuppressive cells, reduced tumor purity, and higher immune checkpoint expression. Single-cell analysis revealed progressive EN1 upregulation along malignant cell pseudotime. Drug sensitivity prediction suggested that the EN1-high group may have reduced sensitivity to temozolomide and additional chemotherapeutic agents. The identified NEAT1/miR-9-5p/miR-128-3p/EN1 ceRNA loop suggested a regulatory mechanism contributing to EN1 activation. EN1 knockdown significantly suppressed glioblastoma cell proliferation and invasion in vitro. EN1 is associated with glioma aggressiveness, immune microenvironmental features, and predicted chemotherapeutic response, and a putative NEAT1/miR-9-5p/miR-128-3p/EN1 axis may contribute to EN1 dysregulation. These findings identify EN1 as a promising biomarker and potential therapeutic target for improving glioma treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gliomas constitute the most prevalent and aggressive primary brain tumors, representing approximately 30% of all central nervous system (CNS) malignancies and up to 80% of all malignant brain tumors1,2. Glioblastoma represents one of the most aggressive and fatal brain tumors, with patients typically surviving only 15–18 months, and fewer than 3% maintaining progression-free survival (PFS) beyond five years3,4,5. Although recent progress in imaging modalities, neurosurgical techniques, radiotherapy, and the development of novel chemotherapeutic agents has led to noticeable improvements in the management of gliomas6, malignant forms such as GBM remain highly invasive, and an effective curative treatment is still lacking7. The limited therapeutic success is largely due to the intricate and strongly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) characteristic of glioblastoma, which includes glioma cells, glioma stem-like cells (GSCs), diverse immune cell populations, neural components, brain vasculature, and extracellular matrix (ECM) elements8,9. Consequently, there is an urgent need to identify novel molecular biomarkers and therapeutic targets to enhance diagnostic accuracy, prognostic assessments, and treatment efficacy in glioma patients.

Engrailed-1 (EN1) is a homeobox-containing transcription factor traditionally recognized for its pivotal role in embryonic neural development, including the patterning of the midbrain and the regulation of dopaminergic neuron differentiation10,11. Beyond its developmental functions, emerging evidence has implicated EN1 in the pathogenesis of various cancers. Studies have demonstrated that EN1 is aberrantly expressed in several tumor types, where it contributes to tumor progression, metastasis, and resistance to apoptosis12,13. For instance, EN1 overexpression has been associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, suggesting its potential as an oncogenic driver14,15. However, the specific roles and underlying mechanisms of EN1 in glioma, particularly in relation to the tumor immune microenvironment and chemoresistance, remain largely unexplored.

This study aims to comprehensively explore the role of EN1 in glioma progression and immune evasion. We integrate transcriptomic analyses from bulk RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq, and ceRNA network predictions to investigate EN1’s expression patterns, its relationship with immune cell infiltration, and its potential regulatory mechanisms. Additionally, we perform in vitro validation of EN1’s functional roles in glioblastoma cells, focusing on its effects on proliferation and invasion. Ultimately, this work aims to identify EN1 as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for improving glioma treatment outcomes.

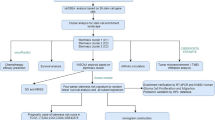

Materials and methods

Data source

Transcriptomic and clinical data for 33 cancer types, including 698 glioma samples (GBM + LGG), were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). An independent validation cohort consisting of 693 glioma samples (CGGA_693) was downloaded from the Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA) database (http://www.cgga.org.cn/). Normal brain controls (1,153 samples) were retrieved from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project (https://gtexportal.org). Single-cell RNA-seq data from 44 glioma specimens (GSE182109) were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). All datasets were publicly available, fully de-identified, and therefore exempt from institutional ethical approval.

EN1 expression analysis

We obtained RNA-seq data for 33 tumor types and their corresponding normal tissues from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the Genotype Tissue Expression (GTEx) databases. Additionally, glioma RNA-seq data were downloaded from the Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA). The differences in EN1 expression between unpaired normal and tumor tissues, as well as paired normal and tumor samples were evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All expression data were log2-transformed [log2(value+1)].

Diagnostic value analysis

To determine the diagnostic performance of EN1, we performed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, calculating the area under the ROC curve (AUC). Tumor data from TCGA and normal tissue data from GTEx were used. An AUC > 0.9 indicated excellent performance, AUC > 0.8 was considered good, and AUC > 0.7 suggested useful discrimination.

Survival prognosis analysis

Overall survival (OS) was evaluated using Kaplan–Meier analysis, and subgroup analyses were conducted across different clinical categories of glioma. Patients were stratified into high- and low-EN1 expression groups based on the median EN1 level. Survival curves and hazard ratios were generated using standard survival analysis procedures implemented in R, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

Construction and validation of the nomogram

Variables identified as significant in univariate Cox regression were further analyzed using multivariate Cox models. A prognostic nomogram was constructed to predict 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS, followed by calibration and ROC analyses to assess model performance. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to evaluate clinical utility. All procedures were performed using established survival modeling frameworks in R.

Immune microenvironment assessment

Immune cell infiltration was quantified using the CIBERSORT algorithm, while stromal, immune, and ESTIMATE scores were calculated to assess tumor purity. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was performed to identify EN1-associated immune modules using an appropriate soft-thresholding power selected according to scale-free topology criteria. Functional enrichment analyses, including GO, KEGG, GSEA, and GSVA, were conducted on genes within key modules using standard enrichment analysis pipelines.

scRNA-seq data processing and analysis

Single-cell RNA-seq data (GSE182109) were processed using Seurat. Quality control was performed by excluding cells with the following thresholds: gene count per cell > 200 and < 6,000; mitochondrial gene percentage < 15%; and UMI count > 1,000. Highly variable genes were identified, and principal component analysis (PCA) and uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) were used for dimensionality reduction and clustering. Cell types were annotated using SingleR. Marker genes were identified using differential expression analysis, and pseudotime trajectories were reconstructed using the Monocle3 package.

Construction of the loop CeRNA network

We employed miRBD (https://mirdb.org/) and starBase (https://rnasysu.com/encori/) to predict miRNAs targeting EN1. The parameters were set to Clade = mammal, Genome = human, Assembly = hg19, and a minimum of 1 program support. Results from both databases were intersected. Potential lncRNAs targeting has-miR-9-5p and has-miR-128-3p were predicted via miRNet (https://www.mirnet.ca/) and starBase; intersections were then taken. The R package “ggalluvial” was used to visualize the ceRNA network. Lastly, JASPAR (jaspar.elixir.no) was employed to predict NEAT1 promoter sites potentially bound by EN1.

Cell culture and transfection

Normal human astrocyte cell line (HA1800) and glioblastoma (GBM) cell lines (U251, U118, and U87) were obtained from the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology (Shanghai, China). All cells were cultured in standard DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were transfected with EN1 shRNA or scrambled control shRNA using Lipofectamine 3000 following the manufacturer’s guidelines. All experiments were performed using three independent biological replicates.

Western blotting

Protein extraction, SDS-PAGE separation, and PVDF membrane transfer were performed using standard procedures. After incubation with primary and secondary antibodies, protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence.

CCK-8 assay

Cell proliferation was evaluated using the CCK-8 assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell viability was calculated as the ratio of the OD value at the indicated time/the OD value at 0 h of the input cells.

Transwell assay

Invasion assays were conducted using Matrigel-coated chambers. Cells transfected with shEN1 or control shRNA were seeded in serum-free medium in the upper chamber, and medium containing 10% FBS was placed in the lower chamber as a chemoattractant. After 24 h, invaded cells were fixed, stained, and counted.

Statistical analysis

All computational analyses were performed in R (version 4.4.0) using the following packages: survival 3.3-1.3, survminer 0.4.9, rms 6.3-0.3, ggplot2 3.4.4, WGCNA 1.73, clusterProfiler 4.4.4, GSVA 1.52.3, estimate 1.0.13, and Seurat 4.4.0. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant unless otherwise specified. Multiple-testing correction (FDR) was applied for high-throughput analyses including enrichment, GSVA, differential expression, and immune profiling. Biological experiments were analyzed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests or ANOVA where appropriate.

Results

Expression of EN1 in Pan-Cancer

Comparisons of EN1 expression between tumors (TCGA) and normal tissues (GTEx) revealed significantly elevated EN1 levels in adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC), bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA), cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma (CESC), cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL), colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBC), esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), glioblastoma (GBM), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC), kidney chromophobe (KICH), kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP), lower grade glioma (LGG), liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (OV), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD), rectum adenocarcinoma (READ), stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), testicular germ cell tumors (TGCT), thymoma (THYM), and uterine carcinosarcoma (UCS). Conversely, EN1 was downregulated in breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA), acute myeloid leukemia (LAML), prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD), and skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM) (Fig. 1A). In paired normal–tumor comparisons within TCGA, EN1 was significantly higher in BLCA, COAD, HNSC, KICH, KIRC, KIRP, LIHC, lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), LUSC, STAD, and thyroid carcinoma (THCA) (Fig. 1B). These findings suggest that EN1 may play a role in broad oncogenic processes.

EN1 Expression in Pan-Cancer. (A) EN1 expression was significantly upregulated in multiple tumor types (e.g., ACC, BLCA, CESC, COAD, GBM, HNSC, LGG, LIHC, LUSC, PAAD) and downregulated in BRCA, LAML, PRAD, and SKCM. (B) Paired tumor-normal comparisons within TCGA showed higher EN1 expression in BLCA, COAD, HNSC, KICH, KIRC, KIRP, LIHC, LUAD, LUSC, STAD, and THCA.

Diagnostic value of EN1 in Pan-Cancer

ROC curve analyses indicated that EN1 had strong diagnostic capabilities (AUC > 0.7) in 13 cancer types: BLCA, CHOL, ESCA, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), glioma, HNSC, KIRC, LUSC, oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), sarcoma (SARC), SKCM, THCA, and THYM (Fig. 2).

Prognostic analysis of EN1 in cancers

High EN1 expression was significantly associated with poor OS in ACC, BLCA, glioma, KIRC, and KIRP (Fig. 3). Across multiple clinical subgroups—stratified by age, grade, IDH status, and 1p/19q codeletion—elevated EN1 expression consistently predicted unfavorable outcomes in glioma (Fig. 4). These results underscore the prognostic relevance of EN1 in glioma progression.

Construction and validation of nomogram

We identified potential prognostic variables using univariate and multivariate Cox analyses in TCGA glioma cohorts. Age, WHO grade, 1p/19q codeletion, and EN1 were confirmed as independent prognostic factors for glioma (Fig. 5A). Using these factors, we developed a nomogram to predict 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS in glioma (Fig. 5B). Internal validation within the TCGA cohort showed strong concordance between predicted and observed survival (Fig. 5C), with ROC AUCs of 0.864, 0.907, and 0.869 for 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS, respectively (Fig. 5D). Decision curve analysis (DCA) demonstrated that the nomogram provided higher net benefits than the “treat-all” or “treat-none” strategies across a wide range of threshold probabilities (Fig. 5E-G).

Nomogram Construction and Internal Validation. (A) Age, WHO grade, 1p/19q codeletion, and EN1 were identified as independent prognostic factors for glioma. (B) A nomogram was constructed to predict 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS. (C, D) Internal validation in TCGA showed good calibration and high AUCs (0.864, 0.907, and 0.869). (E-G) DCA confirmed higher net benefits of the nomogram.

External validation was conducted using CGGA data (Fig. 6A). Similar calibration curve results indicated robust predictive performance (Fig. 6B). The ROC analysis produced AUCs of 0.794, 0.840, and 0.836 for 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS, respectively (Fig. 6C). DCA further confirmed the nomogram’s clinical utility in an independent cohort (Fig. 6D-F).

External Validation of the Nomogram. (A) External validation using the CGGA cohort confirmed the robustness of the nomogram. (B) Calibration curves showed excellent agreement between predicted and observed survival in the CGGA cohort. (C) ROC analysis yielded AUCs of 0.794, 0.840, and 0.836. (D-F) DCA demonstrated strong clinical utility in the CGGA cohort.

Immune microenvironment analysis

Immune cell composition varied significantly between high- and low-EN1 groups, such as M2 macrophages (27.35%) in high EN1 group, compared with the low-EN1 group (20.37%) (Fig. 7A). High EN1 expression was linked to elevated levels of immunosuppressive cells, such as macrophages and Tregs (Fig. 7B). Patients with high EN1 expression also had higher stromal, ESTIMATE, and immune scores but lower tumor purity (Fig. 7C–F). Kaplan-Meier curves showed that low EN1 expression paired with higher levels of M2 macrophages or resting NK cells (Fig. 7G, H) was associated with poor survival. Likewise, high EN1 expression combined with elevated infiltration of M0 macrophages, M2 macrophages, or neutrophils (Fig. 7I–K) correlated with significantly worse outcomes. Correlation analysis revealed a strong positive association between EN1 and immune checkpoints (PDCD1/PD-1, CD274/PD-L1, CTLA4, LAG3, HAVCR2/TIM-3, and LGALS9/Galectin-9) (Fig. 7L, M).

Immune Microenvironment Analysis of EN1. (A, B) High EN1 expression was associated with increased immunosuppressive cells, such as M2 macrophages, Tregs. (C-F) High EN1 expression correlated with higher stromal, ESTIMATE, and immune scores, but lower tumor purity. (G, H) Low EN1 expression combined with higher levels of M2 macrophages or resting NK cells was linked to poor survival. (I-K) High EN1 expression paired with elevated infiltration of M0 macrophages, M2 macrophages, or neutrophils was associated with worse outcomes. (L, M) EN1 showed strong positive correlations with immune checkpoints.

WGCNA analysis and functional enrichment

We performed WGCNA on the CIBERSORT results to identify gene modules related to immune cell infiltration. When the soft threshold was set to 9, the network achieved near scale-free topology (Fig. 8A). After clustering, distinct gene modules were generated (Fig. 8B), each showing unique correlations with various immune cells (Fig. 8C). EN1 showed the strongest positive correlation with the MEblue module (R = 0.724, P < 0.001) (Fig. 8D). Functional enrichment of the MEblue module indicated enrichment in pathways related to oxidative stress, the actin cytoskeleton, and MAPK signaling16 (Fig. 8E). GSEA further revealed significant pathways such as Collagen Formation and TP53-related cell cycle regulation (Fig. 8F), while GSVA showed enrichment of Wnt/β-catenin, TGF-β, and IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling in the high-EN1 group (Fig. 8G). These data indicate that EN1 may regulate key oncogenic and immunomodulatory pathways.

WGCNA Analysis and Functional Enrichment. (A) WGCNA identified immune-related gene modules with a soft threshold of 9. (B, C) Gene modules were clustered and correlated with immune cell infiltration. (D) EN1 showed the strongest correlation with the MEblue module (R = 0.724, P < 0.001). (E) Functional enrichment of the MEblue module revealed pathways related to oxidative stress, actin cytoskeleton, and MAPK signaling. (F) GSEA indicated significant enrichment in Collagen Formation and TP53-related cell cycle regulation pathways. (G) GSVA showed enrichment of Wnt/β-catenin, TGF-β, and IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling pathways in the high-EN1 group.

Single-Cell analysis and drug sensitivity

We analyzed nine GBM samples from GSE182109. PCA followed by UMAP partitioned these cells into 21 clusters (Fig. 9A). Annotation via “SingleR” identified astrocytes, macrophages, monocytes, NK cells, T cells, and tissue stem cells (Fig. 9B). EN1 was predominantly expressed in astrocytes (Fig. 9C, D). Pseudotime analysis revealed an upward trend in EN1 expression from early to late cell states (Fig. 9E, F), suggesting its role in advanced tumor progression. Moreover, drug sensitivity tests showed that the high-EN1 group showed higher predicted IC50 values, indicating potentially reduced sensitivity (i.e., lower sensitivity) for temozolomide, carmustine, vincristine, and cisplatin compared to the low-EN1 group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 9G–J).

Single-Cell Analysis and Drug Sensitivity. (A, B) UMAP and cell type annotation identified 21 clusters, including astrocytes, macrophages, monocytes, NK cells, T cells, and tissue stem cells. (C, D) EN1 was predominantly expressed in astrocytes. (E, F) Pseudotime analysis showed increasing EN1 expression in advanced cell states. (G-J) High-EN1 group exhibited lower sensitivity to temozolomide, carmustine, vincristine, and cisplatin (higher IC50 values).

Construction of the loop CeRNA network

Using starBase and miRBD, we identified 20 candidate miRNAs targeting EN1 (Fig. 10A, B). Survival analysis indicated that high expression of has-miR-9-5p and has-miR-128-3p correlated with better prognosis, whereas has-miR-216a-3p, has-miR-369-3p, has-miR-381-3p, and has-miR-944 were associated with poorer outcomes (Fig. 10C–H). Notably, has-miR-9-5p and has-miR-128-3p showed negative correlations with EN1 (Fig. 10I–N).

Identification of miRNAs Targeting EN1. (A, B) Twenty candidate miRNAs targeting EN1 were identified. (C-H) High miR-9-5p and miR-128-3p expression correlated with better prognosis, while miR-216a-3p, miR-369-3p, miR-381-3p, and miR-944 were linked to poorer outcomes. (I-N) miR-9-5p and miR-128-3p showed negative correlations with EN1.

Subsequent miRNet and starBase analyses identified four lncRNAs (XIST, SNHG7, NEAT1, and LINC00921) that could bind has-miR-9-5p (Fig. 11A, B), and ten lncRNAs (NEAT1, MAGI2-AS3, SNHG16, etc.) that could bind has-miR-128-3p (Fig. 11C, D). Among these, NEAT1 was common to both miR-9-5p and miR-128-3p. Elevated NEAT1 expression was associated with poor glioma prognosis (Fig. 11E), and correlation analysis showed negative correlations between NEAT1 and both miR-9-5p and miR-128-3p (Fig. 11F, G). EN1 binding motifs were predicted in the promoter region of NEAT1 according to JASPAR (Fig. 11H). Integrating these findings, we constructed a NEAT1/miR-9-5p/miR-128-3p/EN1 loop ceRNA network (Fig. 11I).

Construction of the Loop ceRNA Network. (A-D) NEAT1, shared by miR-9-5p and miR-128-3p, was identified among binding lncRNAs. (E) NEAT1 expression was associated with poor prognosis. (F, G) NEAT1 negatively correlated with miR-9-5p and miR-128-3p. (H) JASPAR predicted EN1 binding motifs in the NEAT1 promoter region. (I) The NEAT1/miR-9-5p/miR-128-3p/EN1 ceRNA network was constructed.

EN1 expression and functional validation in glioblastoma cells

Based on the bioinformatic evidence suggesting an oncogenic role of EN1 in glioma, we next performed in-vitro experiments to validate its biological functions. Western bloting analysis indicated markedly higher EN1 expression in glioblastoma cell lines (U87 and U118) compared to normal astrocyte (HA1800) (P < 0.05) (Fig. 12A). After EN1 knockdown via shRNA (shEN1), both U87 and U118 cells exhibited significantly reduced proliferation at 24 h, with more pronounced effects at 72 and 120 h, as shown by CCK-8 assays (Fig. 12B, C). Transwell invasion assay further demonstrated that EN1 knockdown substantially inhibited the invasive capacity of these glioblastoma cells (P < 0.05) (Fig. 12D). These in vitro findings support a pro-tumorigenic role of EN1 in glioblastoma cells and are consistent with the bioinformatic associations observed in patient cohorts.

EN1 Expression and Functional Validation in Glioblastoma Cells. (A) EN1 expression was significantly higher in glioblastoma cell lines (U87, U118) than in normal astrocytes (P < 0.05). (B, C) EN1 knockdown reduced proliferation of U87 and U118 cells (P < 0.05). (D) EN1 knockdown significantly impaired the invasive ability of glioblastoma cells (P < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we systematically evaluated the expression patterns and clinical relevance of Engrailed-1 (EN1) across multiple malignancies, with a particular focus on glioma. Our analyses across TCGA, GTEx, and CGGA databases demonstrated that elevated EN1 expression correlates with poor prognosis in a subset of solid tumors, including ACC, BLCA, glioma, KIRC, and KIRP. Notably, in glioma cohorts, EN1 showed strong diagnostic and prognostic potential, suggesting that EN1 may serve as a biomarker and a potential contributor to glioma progression.

Several studies have highlighted the significance of homeobox-containing transcription factors in tumorigenesis, typically through their ability to modulate cell fate, proliferation, and differentiation programs17,18,19,20. Our findings underscore this notion, as high EN1 expression was strongly associated with worse OS in glioma. By integrating EN1 into a prognostic nomogram with age, WHO grade, and 1p/19q codeletion status, we achieved robust predictive performance. This multidimensional approach aligns with the contemporary trend of employing multi-parameter models rather than relying on single-gene markers, thereby improving the accuracy of patient stratification. Given that clinical management of glioma varies significantly based on tumor grade and molecular profiles, the addition of EN1 into existing prognostic frameworks could refine therapeutic decision-making.

Our immune infiltration analyses revealed a pronounced correlation between elevated EN1 levels and increased infiltration of immunosuppressive cells, notably M2 macrophages. M2-polarized macrophages are known to secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β) and support tumor immune evasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis21,22,23. We also observed that high EN1 expression was associated with lower tumor purity and higher ESTIMATE and immune scores, suggesting a more complex stromal-tumor interface in glioma. These findings align with recent investigations demonstrating that transcription factors can modulate tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) polarization24,25. Specifically, these observations raise the possibility that EN1-related transcriptional programs may be linked to macrophage recruitment or polarization, thus fostering an immunosuppressive microenvironment conducive to tumor progression. However, direct experimental validation is required.

Furthermore, our correlation analyses showed a robust positive association between EN1 and various immune checkpoint molecules (e.g., PD-1/PDCD1, PD-L1/CD274, CTLA4), echoing literature indicating that high levels of immune checkpoints often coexist with immunosuppressive microenvironment26,27,28.

Future mechanistic studies, such as chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and reporter gene assays, could clarify whether EN1 directly controls the transcription of immunomodulatory genes or interacts with other transcription factors regulating checkpoint pathways.

By leveraging single-cell RNA-seq data, we identified that EN1 is predominantly localized to astrocyte glioma cells and exhibits progressive upregulation over pseudotime. This suggests that EN1 may play a critical role in maintaining a more advanced or stem-like phenotype in glioma cells, consistent with reports linking transcription factors to glioma stem cell compartments29,30. Intriguingly, our drug sensitivity analyses showed that EN1-high glioma cells were more resistant to chemotherapeutic agents, including temozolomide—considered a cornerstone in glioma therapy. Potential mechanisms underlying EN1-associated resistance could include (i) regulation of DNA damage repair pathways, as has been noted in other homeoproteins31,32; (ii) direct upregulation of multidrug efflux transporters (e.g., ABC family transporters)33,34; or (iii) enhanced pro-survival signaling (e.g., PI3K/AKT, MAPK) that reduces apoptosis in response to chemotherapeutic stress12,13.

One of the notable aspects of our study is the establishment of a ceRNA-based regulatory loop involving EN1, NEAT1, and miR-9-5p/miR-128-3p. ceRNA networks have emerged as a crucial layer of post-transcriptional regulation in cancer, where lncRNAs act as molecular sponges for tumor-suppressive miRNAs, thereby preventing them from binding to their mRNA targets35,36. NEAT1, in particular, has been described as an oncogenic lncRNA in multiple tumor types, capable of modulating cell proliferation, migration, and even therapy resistance37,38,39.

We observed that NEAT1 could bind both miR-9-5p and miR-128-3p, while these miRNAs showed a strong negative correlation with EN1 expression. This arrangement is consistent with a putative ceRNA model in which NEAT1 may act as a molecular sponge for miR-9-5p and miR-128-3p, potentially attenuating their inhibitory effects on EN1 expression. Moreover, predictive binding site analysis (via JASPAR) indicated that EN1 may, in turn, bind to the NEAT1 promoter region, implying a possible positive feedback loop. Such reciprocal “activation” loops can significantly amplify oncogenic signals and contribute to tumor aggressiveness.

Our functional assays confirmed that EN1 knockdown significantly attenuates glioblastoma cell proliferation and invasion, reinforcing the oncogenic role of this transcription factor. Given EN1’s links to immunosuppressive signals and chemoresistance, a multifaceted therapeutic strategy could be envisioned. On one hand, combining EN1 inhibitors (or knockdown approaches) with immune checkpoint blockade might help overcome the limitations of monotherapy in glioma patients, as both intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms of tumor immune evasion could be diminished.

On the other hand, modulating the NEAT1/miR-9-5p/miR-128-3p/EN1 axis—perhaps through antisense oligonucleotides targeting NEAT1 or miRNA mimics—may further sensitize tumor cells to conventional therapies.

Despite our comprehensive bioinformatic analyses of EN1 across multiple datasets and the functional validation in glioblastoma cell lines, this study still lacks in-depth mechanistic investigations. While our results strongly suggest that EN1 exerts oncogenic effects and modulates the tumor microenvironment, the precise molecular pathways and direct interactions remain unclear. Future work involving detailed mechanistic experiments (e.g., chromatin immunoprecipitation, co-immunoprecipitation, or proteomics) will be essential to elucidate how EN1 regulates downstream signaling networks and contributes to tumor progression.

Conclusion

In summary, our study demonstrates that EN1 is consistently associated with glioma progression, immune microenvironment–related features, and predicted therapeutic response across multiple datasets. Integrative analyses suggest a putative NEAT1/miR-9-5p/miR-128-3p/EN1 ceRNA regulatory axis that may contribute to EN1 dysregulation in glioma. Together, these findings highlight EN1 as a potential biomarker and candidate target, warranting further mechanistic and translational investigations.

Data availability

The bulk RNA-seq and corresponding clinical data analyzed in this study were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), including the TCGA-GBM and TCGA-LGG cohorts. Normal brain tissue expression data were retrieved from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project (https://gtexportal.org). An independent validation cohort was obtained from the Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA, http://www.cgga.org.cn/), specifically the CGGA_693 dataset. Single-cell RNA sequencing data were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession number GSE182109. All datasets used in this study are publicly available and fully de-identified.

References

Ostrom, Q. T. et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the united States in 2016–2020. Neuro Oncol. 25, iv1–iv99. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noad149 (2023).

Louis, D. N. et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 23, 1231–1251. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noab106 (2021).

Grochans, S. et al. Epidemiology of glioblastoma Multiforme-Literature review. Cancers (Basel). 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14102412 (2022).

Kotecha, R., Odia, Y., Khosla, A. A. & Ahluwalia, M. S. Key clinical principles in the management of glioblastoma. JCO Oncol. Pract. 19, 180–189. https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.22.00476 (2023).

Ntafoulis, I., Koolen, S. L. W., Leenstra, S. & Lamfers, M. L. M. Drug Repurposing, a Fast-Track approach to develop effective treatments for glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel). 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14153705 (2022).

Thenuwara, G., Curtin, J. & Tian, F. Advances in diagnostic tools and therapeutic approaches for gliomas: A comprehensive review. Sens. (Basel). 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/s23249842 (2023).

Miller, K. D. et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 72, 409–436. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21731 (2022).

Sharma, P., Aaroe, A., Liang, J. & Puduvalli, V. K. Tumor microenvironment in glioblastoma: current and emerging concepts. Neurooncol Adv. 5, vdad009. https://doi.org/10.1093/noajnl/vdad009 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. The immunosuppressive microenvironment and immunotherapy in human glioblastoma. Front. Immunol. 13, 1003651. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1003651 (2022).

Sgado, P. et al. Slow progressive degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons in postnatal engrailed mutant mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 103, 15242–15247. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0602116103 (2006).

Simon, H. H., Saueressig, H., Wurst, W. & Goulding, M. D. O’Leary, D. D. Fate of midbrain dopaminergic neurons controlled by the engrailed genes. J. Neurosci. 21, 3126–3134. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-03126.2001 (2001).

Xu, J. et al. Engrailed-1 promotes pancreatic cancer metastasis. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 11, e2308537. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202308537 (2024).

Cui, Y. et al. EN1 promotes lung metastasis of salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma by regulating the PI3K-AKT pathway and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Cell. Int. 24, 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-024-03230-7 (2024).

Peluffo, G. et al. EN1 is a transcriptional dependency in Triple-Negative breast cancer associated with brain metastasis. Cancer Res. 79, 4173–4183. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3264 (2019).

Zhao, N. et al. [En1 promotes cell proliferation and migration via Hedgehog signaling pathway in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 46, 99–107. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112152-20231026-00257 (2024).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Zagozewski, J. L., Zhang, Q., Pinto, V. I., Wigle, J. T. & Eisenstat, D. D. The role of homeobox genes in retinal development and disease. Dev. Biol. 393, 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.07.004 (2014).

Xu, F. et al. HOXD13 suppresses prostate cancer metastasis and BMP4-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition by inhibiting SMAD1. Int. J. Cancer. 148, 3060–3070. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.33494 (2021).

Gao, A. C., Lou, W. & Isaacs, J. T. Down-regulation of homeobox gene GBX2 expression inhibits human prostate cancer clonogenic ability and tumorigenicity. Cancer Res. 58, 1391–1394 (1998).

Lin, L. et al. The homeobox transcription factor MSX2 partially mediates the effects of bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) on somatic cell reprogramming. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 14905–14915. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA118.003913 (2018).

Mantovani, A., Sozzani, S., Locati, M., Allavena, P. & Sica, A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 23, 549–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02302-5 (2002).

Yang, Y. et al. M2 Macrophage-Derived exosomes promote angiogenesis and growth of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by targeting E2F2. Mol. Ther. 29, 1226–1238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.11.024 (2021).

Chen, Y., Zhang, S., Wang, Q. & Zhang, X. Tumor-recruited M2 macrophages promote gastric and breast cancer metastasis via M2 macrophage-secreted CHI3L1 protein. J. Hematol. Oncol. 10, 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-017-0408-0 (2017).

Tan, S. et al. Transcription factor Zhx2 is a checkpoint that programs macrophage polarization and antitumor response. Cell. Death Differ. 30, 2104–2119. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-023-01202-4 (2023).

Jiang, H. et al. Zeb1-induced metabolic reprogramming of Glycolysis is essential for macrophage polarization in breast cancer. Cell. Death Dis. 13, 206. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-04632-z (2022).

Brunner-Weinzierl, M. C. & Rudd, C. E. CTLA-4 and PD-1 control of T-Cell motility and migration: implications for tumor immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 9, 2737. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02737 (2018).

Sun, C., Mezzadra, R. & Schumacher, T. N. Regulation and function of the PD-L1 checkpoint. Immunity 48, 434–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.014 (2018).

Rowshanravan, B., Halliday, N. & Sansom, D. M. CTLA-4: a moving target in immunotherapy. Blood 131, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-06-741033 (2018).

Chen, X. et al. Oct4A palmitoylation modulates tumorigenicity and stemness in human glioblastoma cells. Neuro Oncol. 25, 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noac157 (2023).

Sun, Y. M. et al. Enhancer-driven transcription of MCM8 by E2F4 promotes ATR pathway activation and glioma stem cell characteristics. Hereditas 160, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41065-023-00292-x (2023).

Bowen, C., Zheng, T. & Gelmann, E. P. NKX3.1 suppresses TMPRSS2-ERG gene rearrangement and mediates repair of androgen Receptor-Induced DNA damage. Cancer Res. 75, 2686–2698. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3387 (2015).

Soret, C. et al. Distinct mechanisms for opposite functions of homeoproteins Cdx2 and HoxB7 in double-strand break DNA repair in colon cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 374, 208–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.026 (2016).

Liu, X. A. B. C. & Family Transporters Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1141, 13–100, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7647-4_2 (2019).

Vadlapatla, R. K., Vadlapudi, A. D., Pal, D. & Mitra, A. K. Mechanisms of drug resistance in cancer chemotherapy: coordinated role and regulation of efflux transporters and metabolizing enzymes. Curr. Pharm. Des. 19, 7126–7140. https://doi.org/10.2174/13816128113199990493 (2013).

Xu, J., Xu, J., Liu, X. & Jiang, J. The role of lncRNA-mediated CeRNA regulatory networks in pancreatic cancer. Cell. Death Discov. 8, 287. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-022-01061-x (2022).

Tay, Y., Rinn, J. & Pandolfi, P. P. The multilayered complexity of CeRNA crosstalk and competition. Nature 505, 344–352. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12986 (2014).

Zhang, Y., Luo, M., Cui, X., O’Connell, D. & Yang, Y. Long noncoding RNA NEAT1 promotes ferroptosis by modulating the miR-362-3p/MIOX axis as a CeRNA. Cell. Death Differ. 29, 1850–1863. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-022-00970-9 (2022).

Wen, S. et al. Long non-coding RNA NEAT1 promotes bone metastasis of prostate cancer through N6-methyladenosine. Mol. Cancer. 19, 171. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-020-01293-4 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. N6-methyladenosine reader hnRNPA2B1 recognizes and stabilizes NEAT1 to confer chemoresistance in gastric cancer. Cancer Commun. (Lond). 44, 469–490. https://doi.org/10.1002/cac2.12534 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the members of our study.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from High-Level Talent Scientific Research Start-Up Project of the Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical University [grant number GCC2021006].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZL and WL: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing. ZJ: Methodology, Writing- Original draft. YW and JY: Formal analysis. LZ and XL: Visualization. TW: Data Curation. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jia, Z., Wang, Y., Yao, J. et al. Engrailed 1 promotes immune evasion and chemoresistance in glioma through single cell and CeRNA network analyses. Sci Rep 16, 4913 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35553-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35553-y