Abstract

Acetabular anterior column and posterior hemi-transverse fractures pose a significant challenge for orthopaedic surgeons. Traditional treatment methods are associated with high rates of post-operative complications and lengthy surgical procedures. To enhance treatment efficacy, this study developed a novel internal fixation device called the Combined Reduction Anatomical Plate (CORAP) and conducted a finite element analysis to compare its biomechanical properties to those of traditional internal fixation methods. A standard finite element model of an anterior column and posterior hemi-transverse fracture of the femur was established using finite element software. Subsequently, four different internal fixation devices were applied: CORAP, double-column locking plates (DLP), supra-pectineal quadrilateral anatomical plate (SQAP), and iliositus + anterior column plate (LACP). After determining the boundary conditions and material properties, the model was simulated in three different body positions (standing, sitting, and lying on the affected side) and subjected to vertical downward forces of 200 N, 400 N, and 600 N. Subsequently, the stress distribution and peak values among the four fixation methods were analyzed, and the maximum pelvic displacement and fracture fragment displacement were evaluated. In this study, the CORAP maximum stress on the steel plate and screws was 159.540 N, 160.540 N, 157.050 N, 177.330 N, 64.756 N, and 30.003 N, which was less than that of the SQAP and LACP and greater than that of the DLP. The maximum tangential micromotion of the CORAP was only 0.016 mm, and the maximum displacement of the pelvis was 0.855 mm. The results showed that the new type of plate developed and designed in this study exhibited a relatively uniform stress distribution and high stiffness, providing sufficient strength. However, the four groups showed no obvious difference in tangential fretting. Compared with the other three fixation methods, the newly designed sectional anatomical reduction plate and screws showed a uniform stress distribution, greater rigidity, sufficient strengthand mechanical stability. The CORAP can therefore provide sufficient biomechanical stability and help fracture healing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acetabular fractures, intricate fractures occurring within the joint, are primarily the result of high-impact trauma. Recently, their frequency has risen due to a higher occurrence of traffic and industrial accidents1. To maximize the restoration of hip joint function, improve prognosis, and reduce the occurrence of complications, the preferred method for treating displaced acetabular fractures is now open reduction and internal fixation2,3. According to the Judet-Letournel4 classification system, quadrilateral plate fractures are not classified separately, except for simple anterior and posterior wall fractures; still, 80% of the other fracture types may involve the quadrilateral plate5,6,7. This is particularly true in elderly patients, who often have osteoporosis and comminuted fractures5,8.

Anterior column-posterior hemi-transverse fractures (ACPHTFs) are a common type of acetabular fracture, often accompanied by femoral head protrusion and quadrilateral plate displacement9,10,11. Presently, it is considered that only anatomical reduction, which restores the smoothness and flatness of the hip joint, preserves the blood supply to the femoral head and intra-articular fractures, provides stable internal fixation, and can achieve good clinical outcomes12. However, due to the deep location of the quadrilateral plate, limited surgical space, difficulty in intra-operative exposure, and issues with traditional pelvic plates, such as difficulty in shaping during surgery, poor fit with pelvic anatomical structures, single fixation points, inadequate reduction, fixation of quadrilateral plate fractures, and screws easily entering the hip joint, leading to femoral head necrosis and traumatic arthritis6,13,14, these traditional methods no longer meet the requirements for precise reduction and strong fixation of this type of fracture.

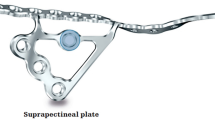

Therefore, In previous studies, our research team designed a specially shaped reconstruction plate (the Combined Reduction Anatomical Plate, CORAP) based on the anatomical characteristics of the acetabulum, which has been granted a Chinese national patent (Patent No.: CN202222137846.2). This fixation system includes two components: a locking plate and a reduction plate. The locking plate is a curved strip designed to fit above the greater sciatic notch, while the reduction plate is contoured to align with the anatomical structures above the acetabulum and the quadrilateral plate. This system is primarily used for treating acetabular fractures that involve the quadrilateral plate, such as posterior column fractures, T-type fractures, ACPHT, and both-column fractures. Considering the extremely irregular shape of the pelvis and the difficulty in shaping plates during surgery, we previously conducted an anatomical study on the CORAP fixation trajectory using computer-aided anatomical measurements. This study led to the design of anatomical plates and reduced the difficulty of shaping traditional plates during surgery15. However, comparative studies on the biomechanical properties of the newly designed CORAP and traditional plates have not been conducted, particularly regarding the biomechanical mechanisms during bone healing.

Therefore, this study aimed to use the finite element method to compare the biomechanical properties and stability differences of four internal fixation methods for treating anterior column-posterior hemi-transverse fractures: combined reduction anatomical plate (CORAP), anterior column-posterior column plate (DLP), supra-pectineal quadrilateral plate (SQAP), and ilio-ischial-anterior column plate (LACP). This research offers a theoretical foundation for the expanded clinical use of the CORAP.

Materials and methods

Establishment of the three-dimensional finite element model for anterior Column-Posterior Hemi-transverse fractures

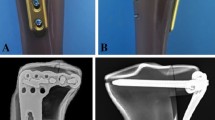

A healthy 23-year-old male volunteer provided informed consent. Pelvic radiography excluded fractures, deformities, tumors, and other pathologies. This research received approval from our hospital’s Medical Ethics Committee (ethics no. KLLY-2022-017). The DICOM data from the volunteers were imported into Mimics software (version 21.0, Materialise Company, Leuven, Belgium). The hemi-pelvic model was reconstructed and exported in STL format, then, in the Geomagic Studio software, the extracted model is subjected to model repair, including surface smoothing treatment and filling of model holes. Subsequently, the STL file is transformed into a solid file by means of this software, and thereafter the solid file is imported into the SolidWorks software to construct a standard finite element model(Fig. 1a).

The ACPHTF model was established according to the Judet and Letournel classification of acetabular fractures16,17. ACPHTFs primarily have two fracture lines: one extends from the anterior superior iliac spine to the inferior edge of the obturator foramen. The other extends from the midpoint of the first fracture line to the uppermost end of the sciatic notch (Fig. 1b)18.

Modelling of four internal fixation models for anterior column-posterior hemi-transverse fractures

In this study, four internal fixation models (CORAP, DLP, SQP, and LCAP) were accurately constructed using SolidWorks 2017 software (SolidWorks Corporation, Dassault, France) based on the actual dimensions and shapes of the fixation devices. During the construction process, special attention was paid to the design characteristics of each fixation device, such as shape, size, and intended biomechanical application, to ensure model realism and functionality. After construction, these models were precisely assembled onto the ACPHTF model for subsequent finite element analysis (Fig. 2).

Definition of boundary Conditions, material properties, and loads

The analysis was conducted using the ANSYS Workbench 2022 R1 (Ansys, Canonsburg, PA) software to generate standardized finite element models.

Boundary conditions

In the model, the contact between the bone surface and the internal fixation devices or between the internal fixation devices themselves was set as bonded contact. The contact between fracture fragments and cartilage was set as frictional contact with a friction coefficient of 0.2 to simulate physiological conditions19.

Material properties

To construct the model, we assumed that all cortical bones, cancellous bones, plates, and screws were homogeneous and isotropic. To make the finite element model closer to physiological conditions, acetabular cartilage was included, and the ligaments were defined based on their anatomical locations. The standard finite element model defined the iliofemoral, ischiofemoral, pubofemoral, inferior iliofemoral, and superior iliofemoral ligaments. The material properties of the cortical bone, cancellous bone, articular cartilage, and ligaments were determined based on previous literature20,21,22,23,24. The material properties are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Loading and constraints

In this study, four different internal fixation methods were used to simulate and analyze the three-dimensional model of ACPHTF. This study included two types of constraints. The first type was a fixed constraint, which fixed the pubic symphysis and sacroiliac joint, restricting all degrees of freedom in three directions (x, y, z) (Fig. 3a). The second type was a partial constraint. A local coordinate system was first established, and the constraint position was at the femoral head. When standing, the degrees of freedom in the x and y directions of the femoral head were constrained; when sitting, the degrees of freedom in the z and y directions of the femoral head were constrained; when lying on the side, the degrees of freedom in the x and z directions of the femoral head were constrained (as shown in Fig. 3a). To simulate the situation where patients with acetabular fractures need to bear partial weight and full weight early, a force of 200 N, 400 N, and 600 N was applied to the front end of the femoral head in the z, x, and y directions, respectively, for each assembly model. The applied force was transmitted through the femoral head to the middle of the hip joint to achieve simulation of standing, sitting, and lying on the side positions. This load application method aimed to simulate different load conditions under real biomechanical conditions to more accurately evaluate the biomechanical performance of different internal fixation methods (Fig. 3b).

Results

Stress distribution and peak stress

First, the strengths of the four internal fixation methods were evaluated. The stress contour maps show that the stress concentration mainly occurred near the fracture lines. Regarding the stress distribution on the plates, in both the standing and affected side-lying positions, as the loading force increased, the anterior column plate of the LACP consistently bore the greatest stress. In the sitting position, with a loading force of 200 N, the ilio-ischial plate of the LACP bore the greatest stress. However, as the loading force increased to 400 N and 600 N, the SQAP exhibited the greatest stress.

Compared to the other three plates, the DLP exhibited a lower Von Mises stress under loading forces of 200 N, 400 N, and 600 N. Additionally, under different loading forces and positions, the maximum stress of the CORAP was less than that of the SQAP and LACP but slightly greater than that of the DLP. This indicates that the CORAP system has a more uniform stress distribution, reducing the possibility of stress concentration and internal fixation failure and providing sufficient strength and better mechanical stability (Figs. 4and Table 3).

Stress contour maps of the four plate groups in standing. A-C represent loading forces of 200 N, 400 N, and 600 N, respectively. A, D, G, and J represent the DLP, LACP, SQAP, and CORAP groups, respectively. In A-C, the left side represents the anterior column plate, and the right side represents the posterior column plate. In D-F, the left side represents the anterior column plate, and the right side represents the ilioischial plate. In J-L, the left side represents the reduction plate, and the right side represents the obtained plate. The red areas indicate high stress, while the blue areas indicate low stress.

Then, we evaluated the stress of the screws.,From the stress contour maps, it can be observed that for almost all internal fixation methods, the maximum stress on the screws occurs in the middle-upper part of the screw and at the screw-plate junction. Therefore, these areas must be reinforced to prevent fatigue fractures. In the standing position, as the loading force increased, the stress on the locking screws (LS) of the CORAP was slightly higher than that in the other three groups. Similarly, in the sitting position with loading forces of 200 N and 400 N, the stress on the LS was slightly higher for the CORAP than for the other three plates. When the loading force increased to 600 N, the reduction screws in the CORAP bore the greatest stress. In the affected side-lying position, there were no significant differences in the maximum stress on the screws among the four plates under different loading forces (Figs. 5; Table 4).

Stress contour maps of the corresponding screws in the four plate groups in standin. A-C represent loading forces of 200 N, 400 N, and 600 N, respectively. A, D, G, and J represent the DLP, LACP, SQAP, and CORAP groups, respectively.In A-C, the left side represents the anterior column screws, and the right side represents the posterior column screws. In D-F, the left side represents the anterior column screws, and the right side represents the ilioischial screws. In J-L, the left side represents the reduction screws, and the right side represents the locking screws.The red areas indicate high stress, while the blue areas indicate low stress.

Micromotion and maximum displacement

Next, the micromotion displacement at the fracture site and maximum displacement of the pelvis were evaluated for the four internal fixation methods. Micromotion, also known as intermittent motion at the fracture end, is defined as a slight movement between the ends of fracture segments. It not only promotes callus formation and accelerates fracture healing but is also an important mechanical parameter in fracture healing25,26. Based on the micromotion displacement contour maps, the LACP exhibited the smallest micromotion (0.001 mm), followed by the combined reduction anatomical plate CORAP at 0.003 mm, with the SQAP showing the largest micromovement at 0.027 mm. The micromotion displacement of the four internal fixation methods showed no significant differences, indicating that the CORAP can offer adequate biomechanical stability. The maximum displacement of the pelvis under the four different internal fixation methods was compared to evaluate the stability of each fixation. It is well-known that maximum displacement of the pelvis is one of the key indicators reflecting the stability of internal fixation27. The maximum displacement of the pelvis includes deformation and rigid-body displacement. The displacement contour maps showed that the maximum displacement of the pelvis with the CORAP (0.855 mm at 600 N in the sitting position) was slightly greater than with the other three fixation methods. The double-column plate group showed relatively smaller displacement in ACPHTF treatment, indicating better stability (as shown in Figs. 6 and 7; Tables 5 and 6).

Maximum displacement cloud of the pelvis in four groups of internal fixation modalities in standing position and different loading forces; A-C are loading forces of 200 N, 400 N and 600 N, respectively, and A, D, G, J denote the DLP, LACP, SQAP, and CORAP groups, respectively. Darker red color indicates larger displacement and lighter blue color indicates smaller displacement.

Cloud view of micromotion displacement of four groups of internal fixation modalities in standing position and different loading forces; A-C are loading forces of 200 N, 400 N and 600 N, respectively, and A, D, G, and J denote the DLP, LACP, SQAP, and CORAP groups, respectively. Darker red color indicates larger displacement and lighter blue color indicates smaller displacement.

Discussion

ACPHTFs are complex acetabular fractures resulting from high-energy trauma, comprising approximately 7% of all acetabular fractures. With an increasingly aging population, its incidence is gradually increasing and is often accompanied by femoral head protrusion and quadrilateral surface displacement, making treatment difficult18,28. Open reduction and stable internal fixation have established themselves as the gold standard for treatment2,3.

Currently, the ideal treatment for the most complex acetabular fractures is the placement of a reconstruction plate from the inner surface of the ilium to the upper surface of the superior pubic ramus. However, single plates often fail to yield satisfactory results. Therefore, surgeons combine posterior column screws, quadrilateral screws, and other plates to reduce the risk of fixation failure29,30,31,32. Although these methods often yield relatively satisfactory clinical outcomes, the complex and deep anatomical structure of the acetabulum poses surgical risks, such as nerve and vascular damage and screw penetration into the hip joint33. Additionally, these fixation techniques may require more surgical trauma, longer operative times, and greater blood loss. Therefore, based on the anatomical characteristics of the acetabulum, this study reports the design of a specially shaped reconstruction plate (CORAP). However, we have not yet compared the new steel with the traditional method of internal fixation. Therefore, this study used finite element analysis34 to compare the biomechanical characteristics and stability differences between the CORAP and traditional fixation methods, thereby providing a theoretical basis for further clinical applications.

First, the stress distributions of the new plate and its screws were compared with those of traditional plates and their corresponding screws to evaluate the stiffness of the plate structure based on stress and deformation. Stress distribution indicates the ability of the plate or screws to resist elastic deformation under force. Stress concentration may lead to deformation or even fracture of plates or screws35. From the stress contour maps, it can be observed that under different loading forces, the stresses on the plates and screws were mainly concentrated near the fracture line in all four groups. This indicates that the screws and plates connecting the fracture line bear more force than other positions, which is consistent with the results of previous studies32,36. Regarding the stiffness of the plates and screws, under the same load and position, the stress on the CORAP and its screws was greater than that on the SQAP and LACP, but less than that on the DLP. This suggests that the new plate provides sufficient strength and good mechanical stability with a more uniform stress distribution, thereby avoiding internal fixation failure. The maximum stress on the screws mainly occurred in the middle and upper parts of the screws at the screw-plate junction. Therefore, it is necessary to enhance the strength of these parts to prevent fatigue fractures. However, as the loading force increased, there was no significant difference in the maximum stress on the screws among the four groups. Although the new plate and screws bear greater stress, the maximum stress is far below the yield strength of the titanium alloy material, which can withstand a maximum stress of 795 MPa37. Finally, the plates and screws in the double-column plate group bore less stress because the fixation included two plates, which could effectively distribute the stress, consistently with previous studies38,39.

Next, we assessed four internal fixation methods for tangential micromotion at the fracture site and maximum pelvic displacement. Micromotion not only promotes callus formation and accelerates fracture healing but is also an important mechanical parameter in the fracture healing process25,26. Therefore, we evaluated the micromotion of the four internal fixation methods. From the tangential micromotion contour maps, there is no significant difference in tangential micromotion among the four internal fixation methods, indicating that CORAP provides sufficient biomechanical stability. The maximum displacement of the pelvis under the four internal fixation methods was compared to evaluate their stability. As is well-known, displacement also reflects the stability of internal fixation27. The maximum displacement of the pelvis includes both deformation and rigid-body displacement. The displacement contour maps showed that the maximum pelvic displacement was slightly larger with the CORAP than that with the other three internal fixation methods. The smallest maximum displacement was observed in the double-column plate group when treating ACPHTFs, demonstrating the best stability. However, the insertion of double-column plates requires a combined anterior-posterior approach, which has disadvantages such as greater exposure, increased risk of soft tissue damage, neurovascular injury, and longer operative time21,40. Although the maximum displacement with the CORAP is larger, previous studies have shown that under stress, there will be some relative displacement between the fracture fragments. This relative displacement in the range of 0.2–1.0 mm can stimulate callus formation and promote fracture healing, whereas displacements greater than 2 mm are detrimental to fracture healing. In this study, the maximum displacement of fractures with all four internal fixation devices under different loads was less than 1 mm, indicating that they are biomechanically conducive to fracture healing27,41,42,43. Therefore, compared to the other three internal fixation methods, CORAP provides sufficient stability and can be considered the preferred choice for the treatment of ACPHTFs.

This study is the first to conduct a finite element analysis of the lateral decubitus position, which is relevant because patients may rest in the lateral decubitus position on the affected side post-operatively. The analysis focused on stress distribution, stress peaks, and other factors when patients rest in this position post-operatively. From the stress contour maps, it can be observed that as the load increases, the new plate and its screws provide sufficient strength and biomechanical stability, preventing internal fixation failure. Micromotion and maximum displacement of the pelvis indicate that in the lateral decubitus position, the CORAP provides adequate stability. Therefore, using CORAP to treat ACPHTFs ensures that regardless of the post-operative position the patient adopts, there will be no internal fixation failure or femoral head dislocation. The CORAP is considered a safe and effective treatment option.

In summary, this study demonstrated that the double-column plate group endured the least stress and provided the highest stability when treating ACPHTFs, which is consistent with previous research on acetabular fracture treatment10,38,44. However, double-column plate fixation has drawbacks, such as significant surgical trauma, a higher risk of neurovascular injury, and prolonged operative time21,40. Single-column plate fixation for acetabular fractures shows greater stress concentration and poorer biomechanical stability21,38,45. To address these limitations, we designed a novel combination of anatomical reduction plates. This fixation system benefits from the stress distribution and stability provided by the two plates and allows effective reduction and fixation of the acetabular quadrilateral, posterior column, and posterior wall fractures through a simple posterior Kocher-Langenbeck approach. This approach overcomes the difficulties associated with traditional combined anterior and posterior approaches for treating complex acetabular fractures. Furthermore, the CORAP was designed based on the acetabular morphology of Chinese patients, making it more anatomically compatible than traditional plates. This novel plate is pre-contoured to match the acetabular surface, avoiding intra-operative pre-bending and shaping, thereby significantly reducing operative time and trauma15.

In this study, the establishment of the finite element models and their parameters followed those of previous studies46,47 that employed similar loading and boundary conditions. Therefore, we consider this study reasonable and reliable. However, our study had some limitations. First, our study was based on computer simulations rather than real-world experiments. The finite element models used in this study were simplified and did not account for the influence of surrounding soft tissues on the fixation methods; therefore, they may not accurately reflect physiological conditions. Nevertheless, previous studies have shown that biomechanical studies based on computer simulations can still provide effective theoretical support for pelvic fracture fixation38,39. Furthermore, there is data indicating that patients need to bear a greater load during postoperative activities. In this study, tests were conducted under the condition of a maximum load of 600 Newtons, which could only reflect the partial load-bearing capacity of patients during postoperative activities.Therefore, further biomechanical studies using artificial or cadaveric pelvises are needed to validate these findings. Finally, this study compared only four types of internal fixation methods for ACPHTF; other fixation methods for acetabular fractures should be compared in future research.

Conclusion

In conclusion, compared to the traditional three internal fixation methods, the CORAP and its accompanying screws exhibit more uniform stress distribution and greater stiffness, providing sufficient strength andmechanical stability. Additionally, negligible variations were observed in interfragmentary motion among the four internal fixation methods, indicating that the CORAP can offer adequate biomechanical stability and is more favorable for fracture healing. Therefore, the CORAP fixation method presented in this study is a safe and effective option for treating ACPHTFs.

Data availability

The datas used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mauffrey, C. et al. The epidemiology and injury patterns of acetabular fractures: are the USA and China comparable? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 472 (11), 3332–3337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-014-3462-8 (2014).

Judet, R., Judet, J. & Letournel, E. Fractures of the acetabulum: classification and surgical approaches for open reduction. Preliminary report. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 46, 1615–1646 (1964).

Zhuang, Y. et al. A short buttress plate fixation of posterior column through single ilioinguinal approach for complex acetabular fractures. Int. Orthop. 41 (1), 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-016-3225-0 (2017).

Letournel, E. Acetabulum fractures: classification and management. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 151, 81–106 (1980).

White, G. et al. Quadrilateral plate fractures of the acetabulum: an update. Injury 44 (2), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2012.10.010 (2013).

Peter, R. E. Open reduction and internal fixation of osteoporotic acetabular fractures through the ilio-inguinal approach: use of buttress plates to control medial displacement of the quadrilateral surface. Injury 46 (Suppl 1), S2–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-1383(15)70003-3 (2015).

Tosounidis, T. H. et al. The use of buttress plates in the management of acetabular fractures with quadrilateral plate involvement: is it still a valid option? Int. Orthop. 39 (11), 2219–2226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-015-2883-7 (2015).

Ferguson, T. A. et al. Fractures of the acetabulum in patients aged 60 years and older: an epidemiological and radiological study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 92 (2), 250–257. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.92b2.22488 (2010).

Märdian, S. et al. Fixation of acetabular fractures via the ilioinguinal versus pararectus approach: a direct comparison. Bone Joint J. (9), 97–b. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.97b9.35403 (2015).

Butterwick, D. et al. Acetabular fractures in the elderly: evaluation and management. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 97 (9), 758–768. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.N.01037 (2015).

Kwak, D. K. et al. Is an anatomical suprapectineal quadrilateral surface plate superior to previous fixation methods for anterior Column-Posterior Hemitransverse acetabular fractures typical in the elderly? A Biomechanical study. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 15 (2), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.4055/cios22055 (2023).

Cai Xianhua, L. & Ximing, W. Analysis of ilioinguinal approach exposure and open reduction strategies for fractures involving the acetabular square region. Chin. J. Orthop. Surg. 23 (16), 1443–1447 (2015).

Kistler, B. J. et al. Are quadrilateral surface buttress plates comparable to traditional forms of transverse acetabular fracture fixation? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 472 (11), 3353–3361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-014-3800-x (2014).

Cui Haomin, Z. & Dongsheng, L. Titanium mesh combined with reconstruction plate for the treatment of complex acetabular fractures involving the quadrilateral area. Chin. J. Clin. Basic. Res. Orthop. 7 (06), 326–332 (2015).

Chongshuai, B. et al. Combined anatomical reduction plate for quadrilateral acetabular fractures via a posterior approach: an anatomical-morphological study. BMC Musculoskel Disord. 25 (1), 417. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-024-07522-x (2024).

Letournel, E. Acetabulum fractures: classification and management. J. Orthop. Trauma. 33 (Suppl 2), S1–s2. https://doi.org/10.1097/bot.0000000000001424 (2019).

Beaulé, P. E., Dorey, F. J. & Matta, J. M. Letournel classification for acetabular fractures. Assessment of interobserver and intraobserver reliability. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 85 (9), 1704–1709 (2003).

Tanoğlu, O. et al. Biomechanical comparison of three different fixation techniques for anterior column posterior Hemitransverse acetabular fractures using anterior intrapelvic approach. Injury 49 (8), 1513–1519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2018.06.020 (2018).

Wu, H. et al. A novel anatomically pre-contoured side-specific titanium plate versus the reconstruction plate for quadrilateral plate fractures of the acetabulum: a propensity-matched cohort study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 15 (1), 172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-020-01659-w (2020).

Shao Qipeng, C. et al. Finite element analysis of three fixation methods for anterior column combined with posterior half horizontal hip fracture. Chin. J. Orthop. Surg. 29 (22), 2067–2071 (2021).

Deng, J. et al. Finite Element Analysis of a Novel Anatomical Locking Guide Plate for Anterior Column and Posterior Hemi-Transverse Acetabular Fractures. #N/A ;41(6):895–903. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40846-021-00655-7 (2021).

Wen Pengfei, L. et al. Establishment of a finite element model for the Lumbar-Pelvic-Hip joint and Biomechanical analysis. Chin. J. Tissue Eng. Res. 27 (36), 5741–5746 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Does the optimal position of the acetabular fragment should be within the radiological normal range for all developmental dysplasia of the hip? A patient-specific finite element analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 11 (1), 109. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-016-0445-3 (2016).

Grecu, D. et al. Numerical simulations of the 3D virtual model of the human hip joint, using finite element method. Rom J. Morphol. Embryol. 51 (1), 151–155 (2010).

Sellei, R. M. et al. Effects of near cortical slotted holes in locking plate constructs. J. Orthop. Trauma. 25 (Suppl 1), S35–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182070f2d (2011).

Steiner, M. et al. Disadvantages of interfragmentary shear on fracture healing–mechanical insights through numerical simulation. J. Orth Res. 32 (7), 865–872. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.22617 (2014).

Liu, X. et al. Comparison between novel anatomical locking guide plate and conventional locking plate for acetabular fractures: A finite element analysis. Life (Basel). 13 (11). https://doi.org/10.3390/life13112108 (2023).

May, C. et al. Comparison of fixation techniques for acetabular fractures involving the anterior column with disruption of the quadrilateral plate: A Biomechanical study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 100 (12), 1047–1054. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.17.00295 (2018).

Sawaguchi, T. et al. Stability of acetabular fractures after internal fixation. A cadaveric study. Acta Orthop. Scand. 55 (6), 601–605. https://doi.org/10.3109/17453678408992404 (1984).

Wu, Y. D. et al. Biomechanical analysis of the acetabular buttress-plate: are complex acetabular fractures in the quadrilateral area stable after treatment with anterior construct plate-1/3 tube buttress plate fixation? Clin. (Sao Paulo). 68 (7), 1028–1033. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2013(07)22 (2013).

Andersen, R. C. et al. Modified stoppa approach for acetabular fractures with anterior and posterior column displacement: quantification of radiographic reduction and analysis of interobserver variability. J. Orthop. Trauma. 24 (5), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181b2b4ca (2010).

Lei, J. et al. Biomechanical analysis of the fixation systems for anterior column and posterior hemi-transverse acetabular fractures. Acta Orthop. Traumatol. Turc. 51 (3), 248–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aott.2017.02.003 (2017).

Wu, H. et al. Single ilioinguinal approach to treat complex acetabular fractures with quadrilateral plate involvement: outcomes using a novel dynamic anterior plate-Screw system. Orthop. Surg. 12 (2), 488–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/os.12648 (2020).

Li, D. et al. Finite element analysis of channel screw and conventional plate technique in tile B2 pelvic fracture. J. Pers. Med. 13 (3). https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13030506 (2023).

Zhang, D. et al. Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of PM-Ti43Al9V0.3Y alloy. Mater. (Basel). 13 (1). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13010198 (2020).

Brolin, K. & Halldin, P. Development of a finite element model of the upper cervical spine and a parameter study of ligament characteristics. Spine 29 (4), 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000090820.99182.2d (2004).

Pei Xuan, H. et al. Finite element analysis of five internal fixation methods for the treatment of type II pelvic Crescent-shaped fracture dislocation. Chin. J. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 37 (10), 1205–1213 (2023).

Li, M. et al. A novel anatomical locking guide plate for treating acetabular transverse posterior wall fracture: A finite element analysis study. Orthop. Surg. 14 (10), 2648–2656. https://doi.org/10.1111/os.13414 (2022).

Deng, J. et al. Finite element analysis of a novel anatomical locking guide plate for anterior column and posterior Hemi-Transverse acetabular fractures %J. J. Med. Biol. Eng. (prepublish):1–9 (2021).

Giordano, V. et al. Operative treatment of transverse acetabular fractures: is it really necessary to fix both columns? Int. J. Med. Sci. 6 (4), 192–199. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.6.192 (2009).

Steiner, M. et al. Numerical simulation of callus healing for optimization of fracture fixation stiffness. PLoS One. 9 (7), e101370. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101370 (2014).

Shi Jinyou, X. et al. Research on the Micro-motion mechanism and Biomechanical stages of fracture healing. Chin. J. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 35 (09), 1205–1211 (2021).

Epari, D. R. et al. Biphasic plating improves the mechanical performance of locked plating for distal femur fractures. J. Biomech. 115, 110192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2020.110192 (2021).

Tosounidis, T. H. & Giannoudis, P. V. What is new in acetabular fracture fixation? Injury 46 (11), 2089–2092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2015.10.012 (2015).

Cahueque, M. et al. Early reduction of acetabular fractures decreases the risk of post-traumatic hip osteoarthritis? J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma. 8 (4), 320–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcot.2017.01.001 (2017).

Anderson, A. E. et al. Subject-specific finite element model of the pelvis: development, validation and sensitivity studies. #N/A 127 (3), 364–373. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1894148 (2005).

Dalstra, M. & Huiskes, R. Load transfer across the pelvic bone. J. Biomech. 28 (6), 715–. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9290(94)00125-n (1995).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments: The authors are grateful to the research participants and all the hospital staff who took an interest and helped with the study.

Funding

The work was supported by the Project of the Provincial and Ministerial Collaborative Innovation Center (No.39 [2020] of the Science and Technology Agency).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bao CS: Participated in study design, Data measurement, data analysis, and main contributor to writing the paper. Chen L and Ao J : data analysis, and paper revision. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of our hospital (Ethics Number: KLLY-2022-017).All subjects provided informed consent to take part in the study. All procedures were conducted according to the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chongshuai, B., Jun, A. & Lin, C. A new combined reduction anatomical plate for the treatment of acetabular anterior column and posterior hemi-transverse fractures: a finite element analysis study. Sci Rep 16, 5306 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35856-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35856-0