Abstract

Rhinoviruses (RVs) are among the most prevalent human respiratory pathogens, yet their molecular characterization remains fragmented across analytical tools and inconsistent between studies. Current genotype assignment typically relies on sequence alignment, pairwise distance calculation, and prototype comparison. This fragmentation hinders reproducibility and scalability. Here, we present rhinotypeR, an open-source R package that provides a scriptable and transparent workflow for RV genotyping based on the VP4/2 genomic region. The package integrates multiple analytical steps; alignment, distance calculation, genotype assignment, and visualization within the Bioconductor ecosystem and applies standardized species-specific thresholds (10.5% for HRV-A/C and 9.5% for HRV-B). Using a validation dataset encompassing over 90% of known RV types, rhinotypeR reproduced pairwise genetic distances obtained with ape and MEGA X with Mantel correlation (r = 1.000, p = 0.001) and negligible numerical deviation (< 10⁻10). Approximately 80% of sequences showed complete agreement with previous genotype assignments by multiple analysts, and most remaining discrepancies occurred near the classification thresholds. Ct value distributions were broadly similar across matched, mismatched, and unassigned sequences, indicating that discrepancies were unlikely to be driven by viral load. By consolidating fragmented analytical steps into a reproducible and automated framework, rhinotypeR improves consistency in rhinovirus genotyping and supports scalable, transparent molecular surveillance. The package is freely available through Bioconductor for research and routine public health applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Genomic studies have improved our understanding of viral infections, providing invaluable insights into their transmission pathways and evolutionary dynamics1,2,3. With the surge in sequence data availability, the capacity to dissect the complex mechanisms underlying virus spread and mutational profiles has become increasingly important4,5. Characterizing viral mutation is particularly relevant in the context of preparing for future pandemics, highlighting the need for user-friendly reproducible analytical tools that support timely interpretation of viral sequence data6,7,8,9, ultimately contributing to global health security.

Rhinoviruses (RVs) stand out as one of the most prevalent human respiratory pathogens10,11,12, yet their impact on human health is often underestimated13,14. Globally, RVs are detected in up to 60% of samples from individuals presenting with acute respiratory illness15,16,17,18. Once considered causes of only mild, self-limiting common colds, RVs are now recognized contributors to severe respiratory disease in both children and adults. Across multiple cohorts, RV-A and RV-C are more frequently associated with severe lower respiratory tract illness and asthma exacerbations than RV-B, which is detected less often in severe cases19,20,21,22. At the cellular level, RV-A and a subset of RV-B attach to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1)23, while RV-C relies on cadherin-related family member 3 (CDHR3)24, a receptor disparity that complicates laboratory diagnosis.

The rhinovirus genome is roughly 7.2 kb and consists of a single open reading frame that encodes for 11 proteins: seven nonstructural proteins (2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3Cpro and 3Dpol) and four structural proteins (VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4)23. RVs are classified into three species (RV-A, -B, and -C)25,26, which are further classified into an expanding tally of genotypes, currently totalling 16925. These genotypes exhibit unique antigenic properties27and undergo independent evolutionary paths24, making monitoring RV transmission and evolution particularly challenging.

The current classification of RV into genotypes relies on the analysis of the VP1 or VP4/2 genomic regions, which have demonstrated congruence in reflecting RV genetic diversity26,28. The VP1 region encodes the major neutralization epitopes and therefore provides the most antigenically informative classification. However, the VP4/2 is more commonly employed due to its shorter length and less variability, hence ease of amplification26. Sequences are typically aligned with prototype strains, and classification is based on pairwise distances to these prototypes, with species-specific thresholds of approximately 10.5% for HRV-A and HRV-C, and 9.5% for HRV-B28. These thresholds build on earlier work establishing genetic distance-based type demarcation26, and have been reiterated in subsequent reviews of rhinovirus taxonomy25. However, since the steps involved span multiple analytical tools and manual decision points, implementations vary substantially between studies and are often difficult to reproduce.

Despite the abundance and burden of rhinoviruses, there is no standardised, scriptable workflow for VP4/2-based genotyping that integrates sequence alignment, distance calculation, prototype-based assignment, and basic quality checks. We therefore introduce “rhinotypeR”29, an open-source R package that provides a reproducible and transparent pipeline for genotype assignment using curated prototype references and predefined, literature-based thresholds. We describe the package, benchmark it against commonly used software, and illustrate end-to-end genotype assignment on a publicly available VP4/2 dataset.

Methods

The rhinotypeR package

Overview

The rhinotypeR package provides an integrated R-based solution for rhinovirus genotyping using VP4/2 sequences. The package integrates multiple analytical stages: data preparation, sequence alignment, distance calculation, and visualization (Fig. 1) within the Bioconductor ecosystem. This modular design allows users to perform complete analyses from sequence alignment through genotype assignment and visualization within a single computational environment. rhinotypeR does not introduce a novel classification algorithm; rather, it formalises established VP4/2 distance-based genotyping rules into a standardised, reproducible workflow.

Workflow of the rhinotypeR package. The package supports two alignment workflows: Option A exports prototypes via getPrototypeSeqs() for external alignment before import, while Option B aligns sequences directly in R using alignToRefs(). Functions are organized into 1) Data preparation (green) for sequence handling and alignment; 2) Distance calculations (blue) computing genetic distances and SNP counts; and 3) Visualization (pink), including SNP displays, amino acid substitutions, genotype frequencies, distance heatmaps, and phylogenetic trees.

This tool builds upon established Bioconductor30 and CRAN31 packages. Sequence handling relies on Biostrings32, while alignment functionality uses msa33 with support for ClustalW, ClustalOMEGA, and MUSCLE algorithms. Genetic distance calculations are performed through MSA2dist34, which extends ape35 by implementing the IUPAC distance model. This model accounts for ambiguous nucleotide codes (e.g., N, R, Y), making it particularly suited for sequences with base-calling uncertainty, a common feature of Sanger-sequenced viral genomes.

Workflow

Users can follow one of two workflows depending on their alignment preferences. Both workflows converge after alignment for downstream functions:

Option A (External alignment): Users export prototype sequences with getPrototypeSeqs(), combine them with query sequences, align using external software (e.g., MAFFT, MUSCLE), manually curate the alignment, and import the result using Biostrings::readDNAStringSet().

Option B (In-R alignment): Users align query sequences directly with packaged prototypes using alignToRefs(), which internally calls the msa package33 to perform multiple sequence alignment. AlignToRefs() extends this functionality by automatically appending the prototype sequences to the user’s input and optionally trimming the resulting alignment to the non-gap span of a selected prototype, ensuring that all sequences are harmonised in length with the reference region. Option A is recommended when users already maintain established alignment pipelines, whereas Option B is suited to fully reproducible, end-to-end analyses conducted entirely within R.

Core functions

The package provides functions for different analytical purposes. These functions, their input and expected outputs are described in Table 1.

Distance calculation: pairwiseDistances() computes genetic distances between all sequence pairs using user-specified evolutionary models (such as IUPAC, raw, JC6936 and K8037) and returns a symmetric distance matrix. overallMeanDistance() summarizes alignment diversity as a single mean distance value; and countSNPs() converts distances to integer SNP counts.

Genotype assignment: assignTypes() compares each query sequence to prototype strains and returns a data frame containing a query ID, assigned type (or “unassigned”), distance to nearest prototype, and the corresponding prototype accession number. Importantly, distance and reference information are reported even for unassigned sequences, facilitating investigation of potential novel types or divergent strains.

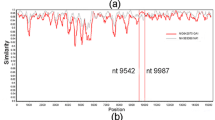

Visualization: SNPeek() displays nucleotide polymorphisms as colored vertical segments (A = green, T = red, C = blue, G = yellow) relative to a reference sequence and supports zooming and highlighting specific sequences. plotAA() provides an analogous visualization for amino acid substitutions, grouping residues by biochemical properties (polar uncharged, nonpolar, positive and negatively charged). plotFrequency() creates bar plots of genotype frequencies, plotDistances() generates distance heatmaps, and plotTree() constructs simple dendrograms from distance matrices.

Reference data and example datasets

The package includes 169 rhinovirus prototype VP4/2 sequences representing distinct types (GenBank accessions listed in Supplementary Table 1). These prototypes are based on the classification scheme of McIntyre and colleagues28 and serve as reference strains for genotype assignment. Prototypes are accessible via getPrototypeSeqs() for external workflows or automatically incorporated by alignToRefs() for in-R workflows.

An example dataset of 253 VP4/2 sequences from a Kenyan school cohort study38 is also included within the package to demonstrate package functionality. This dataset represents typical partial-genome data used in rhinovirus epidemiological studies. Both the prototypes and example data are accessible within R:

User interface and data preparation

rhinotypeR is distributed through Bioconductor and is designed for script-based analysis within the R environment. Installation follows the standard Bioconductor convention and requires no additional dependencies beyond the R/Bioconductor ecosystem. The package accepts high-quality consensus VP4/2 sequences provided as a FASTA file and imported into R as a DNAStringSet object. Genotype assignment results are returned as structured tabular output in the R console and can be readily exported as text-based files (e.g., comma-separated values) for downstream analysis or reporting. Two alternative alignment workflows are supported.

In Option A (external alignment), users export prototype references with getPrototypeSeqs(), combine them with their query sequences, and perform multiple sequence alignment (MSA) using an external program such as MAFFT or MUSCLE. The resulting alignment can then be imported into R and curated to ensure it covers only the VP4/2 region. We recommend trimming any positions outside this region and inspecting the alignment to correct poorly aligned segments, as suboptimal alignments can distort pairwise distance estimates.

Alternatively, Option B (in-R alignment) provides a scriptable workflow in which users import their consensus sequences directly into R, merge them with the packaged prototypes, and perform alignment internally using the msa package. The alignToRefs() function automates this process and can optionally trim the final alignment to the non-gap span of a chosen prototype reference, ensuring that all sequences are harmonized to the correct genomic region.

Given the short amplicon length of VP4/2, Sanger sequencing remains sufficient for most genotyping applications and typically produces high-quality reads suitable for distance-based classification. Regardless of the workflow chosen, maintaining high data quality is essential for accurate results. Users should verify sequence quality during consensus generation, ensure that sequences span the correct genomic region (ideally ≥ 350 bp, typically ~ 420 bp), and minimize gaps or ambiguous bases. Attention to alignment quality and sequence integrity is critical, as these factors directly influence downstream distance calculations and genotype assignments.

Application and comparison to existing tools

We compared genetic distances calculated by rhinotypeR to those produced by MEGA X39 and ape35 using identical alignment inputs and evolutionary models to assess concordance with established phylogenetic workflows. The sequences were aligned together with prototype references using MAFFT and curated to ensure consistent VP4/2 boundaries across all sequences. These were then imported to R and distances were computed using the IUPAC model, and genotypes were assigned according to predefined thresholds of 0.105 for RV-A and RV-C, and 0.095 for RV-B28.

All validation sequences are publicly available through GenBank (accession ranges listed in Data Availability section). These datasets represent prior independent work and were not generated specifically for this validation. Our analysis assesses the consistency and reproducibility of rhinotypeR assignments relative to established classifications, rather than establishing new genotype designations.

In parallel, we explored available rhinovirus/enterovirus genotyping resources to identify comparable tools. Most existing options were web-based and designed for interactive use rather than batch analyses, and some were no longer accessible at the time of this study. We therefore focused our comparison on reproducible distance-based and phylogenetic approaches implemented within R, but also noted the availability and performance of alternative tools. To assess concordance between distance matrices generated by different tools, we used a Mantel test (Pearson correlation, 999 permutations) to evaluate the correlation between pairwise genetic distances. In addition, we quantified numerical agreement by computing the absolute element-wise differences between corresponding entries: |D₁(i,j) − D₂(i,j)|, where D₁ and D₂ represent distance matrices from different tools, and summarized their distribution. This analysis was used to assess numerical equivalence within floating-point precision.

To evaluate the performance of rhinotypeR, we used a compiled VP4/2 sequence dataset40 from multiple studies that investigated the molecular epidemiology of rhinoviruses across different social contexts of varying geographical sizes38,41,42,43. This dataset encompasses over 90% of all recognized rhinovirus genotypes, providing a comprehensive benchmark for validation. The sequences had been previously genotyped by multiple users using different analytical tools and workflows, reflecting the diversity of current laboratory practices. The original studies collectively included 2,373 VP4/2 sequences classified into 157 known and 4 previously unassigned genotypes. To ensure consistency and data quality, we excluded sequences shorter than 350 bases, retaining 2304 sequences representing 159 distinct types for analysis.

Results

Package implementation and reproducibility

The rhinotypeR package, available through Bioconductor (release 3.21), provides an integrated R-based framework for rhinovirus genotyping using the VP4/2 genomic region. It comprises functions organized into three analytical modules: (i) data preparation, (ii) distance calculation and genotype assignment, and (iii) visualization. The package includes two curated VP4/2 reference datasets: prototype sequences representing recognized rhinovirus types28and sequences from a Kenyan school cohort38, both of which can be directly accessed within R.

Installation and use require only standard R/Bioconductor dependencies, with no external software needed for the in-R workflow. The primary function, assignTypes(), computes pairwise distances between query sequences and prototype references, assigning each to the closest genotype if it falls within the specified threshold. Sequences exceeding the threshold are labelled unassigned, indicating potential novelty, divergence, or data quality issues that may warrant further investigation through complementary approaches such as BLAST analysis or recombination detection tools.

Figure 2 illustrates the analytical workflow and outputs generated by rhinotypeR using an example dataset. Panel A shows a curated multiple sequence alignment, the standard input for analysis. Panel B displays the genotype assignment output generated by assignTypes(), where each query sequence is matched to the closest reference strain along with its genetic distance. Sequences exceeding the set thresholds are labelled unassigned but are still reported together with their closest prototype and exact genetic distance. This allows users to inspect borderline cases and, where justified, to apply a relaxed threshold (e.g., up to 11%) to accommodate natural viral diversity or emerging variants while maintaining transparency in classification decisions. Panel C visualizes genotype frequencies via plotFrequency(), allowing users to assess population structure or relative type abundance within a dataset, a key step in epidemiological surveillance.

Key rhinotypeR functions and their outputs applied to a typical rhinovirus dataset. (A) Input alignment of query and prototype sequences. (B) Genotype assignment using assignTypes() showing assigned types, genetic distances, and reference accessions. (C) Frequency distribution of identified genotypes generated with plotFrequency(). (D) Pairwise genetic distance matrix computed with pairwiseDistances(). (E) Heatmap of pairwise distances produced by plotDistances(), illustrating clusters of closely related sequences. (F) Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) visualization using SNPeek() relative to a reference, identifying variable sites across sequences. (G) Phylogenetic tree constructed from the distance matrix using plotTree(), providing an overview of sequence relationships and structure.

Panel D shows the pairwise genetic distance matrix produced by pairwiseDistances(), which quantifies sequence divergence across all comparisons. This matrix can be visualized as a heatmap (Panel E), providing an intuitive overview of relatedness patterns between genotypes or sample clusters, or a simple phylogenetic tree using plotTree() as shown in Panel G. Panel F illustrates SNPeek(), which highlights single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across aligned sequences relative to a reference, enabling users to identify mutation hotspots or sequence conservation regions. Together, these components provide an end-to-end framework for genotyping and exploring genetic relationships in rhinoviruses.

Concordance with established distance calculation tools

To validate the correct integration of distance calculation routines within rhinotypeR, we compared pairwise genetic distance matrices generated by rhinotypeR, ape, and MEGA X using identical VP4/2 alignments and the uncorrected p-distance model. While rhinotypeR’s pairwiseDistances() function relies internally on MSA2dist::dnastring2dist(), correct integration requires proper sequence preprocessing, handling of ambiguous nucleotides, and distance matrix extraction, steps where implementation differences can introduce discrepancies. Visual inspection of distance heatmaps revealed identical clustering patterns across all three implementations (Fig. 3), indicating numerical equivalence.

Comparison of pairwise genetic distance matrices computed by rhinotypeR, ape, and MEGA X. Distance matrices were calculated using identical VP4/2 alignments and the uncorrected p-distance model across all three implementations. Heatmaps display pairwise distances for all sequence pairs, with hierarchical clustering applied to rows and columns. The diagonal (blue) represents zero and near-zero distance (sequences compared to themselves or highly similar sequences), while off-diagonal elements extend to > 0.6 (red, highly divergent sequences).

Quantitative assessment using Mantel tests confirmed a near-perfect correlation between all pairwise tool comparisons. The correlation between rhinotypeR and ape was r = 1.000 (p = 0.001, 999 permutations), as was the correlation between rhinotypeR and MEGA X (r = 1.000, p = 0.001), and between ape and MEGA X (r = 1.000, p = 0.001). To quantify numerical agreement, we computed the absolute element-wise differences between corresponding matrix entries. Mean absolute differences on the order of 10⁻11 to 10⁻12 (Table 2), reflecting floating-point rounding. This suggests that there is no difference in the distance calculations between rhinotypeR and ape and MEGA X.

Computation times were measured on a standard workstation (MacOS 15.7.1, 16 GB RAM, single-core processing). rhinotypeR calculated the complete pairwise distance matrix for 253 rhinovirus sequences in 1.41 s (elapsed time: 1.41 s), while ape completed the same calculation in 0.016 s. The longer runtime for rhinotypeR reflects additional preprocessing steps and progress monitoring implemented, which provide user feedback and input validation during analysis. MEGA X, on the other hand, took slightly longer, with an elapsed time of 9.48 s.

Beyond standalone packages, several web-based genotyping resources were reviewed for comparison. The RIVM Enterovirus Typing Tool (https://mpf.rivm.nl) and Genome Detective Enterovirus Typing Tool (https://www.genomedetective.com) require manual uploads of single sequences, making them impractical for large datasets. Similarly, the former RV-Typer platform, although now discontinued, operated under a similar one-sequence-per-run design. The Rhinovirus Database (RVdb)44 remains available but focuses exclusively on the VP1 genomic region and also accepts single queries. The web-based platforms require manual submission and result retrieval for each sequence. This architecture is suitable for occasional queries but impractical for batch processing of datasets containing hundreds of sequences, as is common in surveillance studies.In contrast, rhinotypeR enables scriptable batch processing of thousands of sequences within R, producing standardized tabular output suitable for downstream statistical analysis and visualization without requiring iterative web submissions.

Genotype assignment validation and agreement analysis

To assess classification accuracy and reproducibility, genotype assignments generated by rhinotypeR were compared against previous designations from the reference dataset (Fig. 4). Overall, 79.5% (n = 1832) of sequences showed complete concordance with prior assignments, 6.2% (n = 142) differed, and 14.3% (n = 330) were unassigned due to exceeding species-specific distance thresholds (Fig. 4A). Agreement was consistent across species, with comparable proportions of matched and unassigned sequences observed among HRV-A, HRV-B, and HRV-C (Fig. 4B).

Concordance between rhinotypeR genotype assignments and previous classifications. (A) Overall agreement between rhinotypeR and prior genotype calls, showing the number and proportion of matching, mismatching, and unassigned sequences. (B) Agreement stratified by rhinovirus species (A, B, and C), expressed as the proportion of sequences in each match category. (C) Distribution of pairwise genetic distances to the nearest prototype strain for each agreement category. (D) Cycle threshold (Ct) values across classification categories, showing substantial overlap and suggesting classification outcomes are not primarily driven by sample quality or viral load.

Genetic distances to the nearest prototype were lowest for matched sequences and highest among unassigned cases (Fig. 4C). This pattern is consistent with the expected distribution around the classification thresholds (10.5% for HRV-A/C and 9.5% for HRV-B), confirming that most mismatches and unassigned sequences lie close to the decision boundary.

To explore whether classification outcomes were influenced by sample quality or viral load, we examined cycle threshold (Ct) values across the three categories (Fig. 4D). Ct values showed substantial overlap among matched, mismatched, and unassigned sequences, with median values around 27–30 for all groups. Pairwise Wilcoxon rank sum tests revealed statistically significant differences between matched sequences and both mismatched (p = 0.048) and unassigned sequences (p = 0.048), but no significant difference between mismatched and unassigned sequences (p = 0.709). However, given the modest p-values near the conventional threshold and the extensive overlap in Ct distributions observed in Fig. 4D, we found no evidence for a strong or consistent biological relationship between viral load and classification outcome in this dataset. The overall similarity in Ct distributions suggests that classification discordance is not primarily driven by sample quality or viral titer.

Discussion

This study introduces rhinotypeR, an open-source R package that provides a reproducible and scriptable framework for rhinovirus genotyping based on the VP4/2 genomic region. By integrating multiple analytical steps, from sequence alignment and distance calculation to genotype assignment and visualization, into a single Bioconductor-compatible workflow, rhinotypeR bridges a long-standing gap between manual genotyping pipelines and automated, reproducible bioinformatics workflows for batch processing.

Our benchmarking analyses demonstrate that rhinotypeR achieves numerical equivalence with established software tools for pairwise distance computation, including ape and MEGA X, across identical datasets and evolutionary models. The Mantel correlation and negligible absolute numerical deviations are attributable to floating-point rounding rather than methodological discrepancies. This confirms that the package’s distance calculations are technically robust and consistent with existing phylogenetic approaches. These results provide confidence that rhinotypeR can serve as a reliable substitute for traditional graphical interfaces, offering the advantages of automation and reproducibility within R.

In terms of runtime performance, rhinotypeR performed efficiently on typical datasets, completing the full pairwise distance computation for 253 sequences in approximately 1.4s on a single-core system. While slightly slower than ape due to progress tracking and internal data validation steps, the package remains highly suitable for large-scale analyses, especially considering that R’s base environment operates in single-threaded mode by default. Importantly, rhinotypeR avoids the need for manual sequence uploads and repeated user interaction, a key limitation observed in web-based alternatives such as the RIVM Enterovirus Typing Tool, Genome Detective, and the now-discontinued RV-Typer. These platforms accept one sequence per submission and are therefore prohibitively time-consuming and error-prone for high-throughput surveillance or large epidemiological datasets.

Validation using a dataset encompassing over 90% of known rhinovirus types further confirmed the reliability of rhinotypeR’s genotype assignment algorithm. Approximately 80% of sequences matched prior classifications, with most remaining discrepancies occurring near the intertype distance thresholds. This is expected given that the strict thresholds (10.5% for HRV-A/C and 9.5% for HRV-B) were defined empirically based on minima in pairwise distance distributions and may shift slightly with the ongoing discovery of novel or divergent strains, or use of different evolutionary models in distance calculations. Importantly, rhinotypeR implements these classification rules within a reproducible and transparent framework, ensuring that analyses are performed consistently across users and datasets. By minimizing subjective or manual steps that can differ between studies, the package reduces the likelihood of future classification ambiguities and facilitates harmonized interpretation. Even unassigned sequences are reported alongside their nearest prototype and genetic distance, allowing users to apply relaxed thresholds or flag potential novel genotypes for further investigation.

The comparison of Ct values across classification outcomes revealed only marginal differences, with extensive overlap between matched and mismatched or unassigned sequences. Although statistical testing yielded borderline p-values, the biological significance of these differences appears minimal. This suggests that classification outcomes are more strongly influenced by sequence divergence than by viral load.

rhinotypeR’s integration with R facilitates seamless connection to downstream statistical analysis, visualization, and reporting pipelines commonly used in epidemiological research. The package’s modular design allows users to leverage existing alignment expertise (external tools like MAFFT) or adopt the in-R workflow for reproducibility. The visualization functions provide rapid assessment of mutation patterns and amino acid substitutions without requiring export to external software, streamlining exploratory analysis during outbreak investigations or longitudinal studies.

Several limitations warrant consideration. First, rhinotypeR is currently restricted to VP4/2-based genotyping. While VP4/2 offers practical advantages in amplification success and is widely used in surveillance, VP1 remains the gold standard for antigenic characterization. Future versions could incorporate VP1-based classification and cross-region concordance checks to provide more comprehensive genotyping. Second, the package does not include recombination detection or phylogenetic inference beyond simple distance-based trees. Users studying recombinant strains or requiring detailed evolutionary analysis should complement rhinotypeR with specialized tools such as RDP4 or IQ-TREE. Finally, as rhinovirus diversity continues to expand through ongoing surveillance, periodic updates to the prototype reference set, and cut-off thresholds will be necessary to maintain classification accuracy for emerging types.

The development of rhinotypeR provides a practical step toward more standardized and reproducible rhinovirus molecular surveillance. By integrating sequence alignment, distance calculation, and genotype assignment within a transparent, scriptable framework, it reduces variability between analyses and enhances comparability across studies and laboratories. This harmonized approach supports more consistent monitoring of circulating types, early recognition of divergent or emerging lineages, and improved linkage between genomic and epidemiological data. Additionally, integration with national and international databases like the World Health Organization (WHO) could be facilitated in settings where suitable application programming interfaces (APIs) are available. As an extensible platform, rhinotypeR also provides a foundation for future developments, such as antigenic profiling through amino acid visualization, positioning it as a valuable tool for routine and research-based viral surveillance.

Conclusion

rhinotypeR offers a reproducible, transparent, and user-friendly framework for rhinovirus genotyping based on the VP4/2 region. The package reproduces the results of established tools with near-perfect accuracy while providing additional advantages in automation, documentation, and downstream compatibility within the R/Bioconductor ecosystem. By consolidating previously fragmented analytical steps into a single pipeline, rhinotypeR improves accessibility and reproducibility of rhinovirus molecular epidemiology studies. Future developments will focus on expanding the reference datasets, incorporating VP1-based classification, integrating parallel computing support to handle larger-scale sequencing projects, and user feedback and suggestions as needed. Collectively, rhinotypeR contributes to more standardized and reproducible molecular surveillance workflows.

Data availability

GenBank accession numbers of prototype strains are available in Supplementary Table 1. Additional data used for validation can be found on GitHub: KX831136—KX831389, OL853844—OL854069, MT177659–MT177911, MH459421-MH460237, MZ129390—MZ130096, KY006195—KY006465 and MW622248—MW623046.

References

Otieno, J. R. Characterizing the genomic diversity, evolution and phylogeography of respiratory syncytial virus genotype ON1 in Kenya. (The Open University ; KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme, 2019).

Butković, A. & Elena, S. F. Genome-wide association studies of viral infections—A short guide to a successful experimental and statistical analysis. Front. Syst. Biol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsysb.2022.1005758 (2022).

Wohl, S., Schaffner, S. F. & Sabeti, P. C. Genomic analysis of viral outbreaks. Annu. Rev. Virol. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-035747 (2016).

Corsi, A., de Souza, F. F., Pagani, R. N. & Kovaleski, J. L. Big data analytics as a tool for fighting pandemics: A systematic review of literature. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 12, 9163–9180 (2021).

Lamb, K. D. et al. Mutational signature dynamics indicate SARS-CoV-2’s evolutionary capacity is driven by host antiviral molecules. PLOS Comput. Biol. 20, e1011795 (2024).

Shafaati, M. et al. The next pandemic catastrophe: Can we avert the inevitable?. New Microbes New Infect. 52, 101110 (2023).

Grad, Y. H. & Lipsitch, M. Epidemiologic data and pathogen genome sequences: A powerful synergy for public health. Genome Biol. 15, 538 (2014).

Awe, O. I., EnNajih, N., Nyamari, M. N. & Mukanga, L. B. Comparative study between molecular and genetic evolutionary analysis tools using African SARS-CoV-2 variants. Inform. Med. Unlocked 36, 101143 (2023).

Awe, O. I., Obura, H. O., Ssemuyiga, C., Evans, M. & Mwanga, M. J. Enhanced deep convolutional neural network for SARS-CoV-2 variants classification. Front. Artif. Intell. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2025.1512003 (2025).

Adema, I. W. et al. Surveillance of respiratory viruses among children attending a primary school in rural coastal Kenya. Wellcome Open Res. 5, 63 (2020).

Nyiro, J. U. et al. Surveillance of respiratory viruses in the outpatient setting in rural coastal Kenya: Baseline epidemiological observations. Wellcome Open Res. 3, 89 (2018).

Jafarinejad, H. et al. Worldwide prevalence of viral infection in AECOPD patients: A meta-analysis. Microb Pathog 113, 190–196 (2017).

Jacobs, S. E. et al. Human rhinovirus infections of the lower respiratory tract in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 15, 474–486 (2013).

Morelli, T., Freeman, A., Staples, K. J. & Wilkinson, T. M. A. Hidden in plain sight: the impact of human rhinovirus infection in adults. Respir. Res. 26, 120 (2025).

Annamalay, A. A. et al. Rhinovirus species and clinical features in children hospitalised with pneumonia from Mozambique. Trop. Med. Int. Health 21, 1171–1180 (2016).

Baillie, V. L. et al. Epidemiology of the rhinovirus (RV) in African and Southeast Asian Children: A case-control pneumonia etiology study. Viruses 13, 1249 (2021).

Zlateva, K. T. et al. Molecular epidemiology and clinical impact of rhinovirus infections in adults during three epidemic seasons in 11 European countries (2007–2010). Thorax 75, 882–890 (2020).

Lu, J. et al. Epidemiology of rhinovirus under the COVID‐19 pandemic in Guangzhou, China, 2020. Immun. Inflamm. Dis.10, (2022).

Jackson, D. J. & Gern, J. E. Rhinovirus infections and their roles in asthma: Etiology and exacerbations. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 10, 673–681 (2022).

Yang, Z., Mitländer, H., Vuorinen, T. & Finotto, S. Mechanism of rhinovirus immunity and asthma. Front. Immunol. 12, 731846 (2021).

Dimopoulos, G. et al. Viral epidemiology of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 25, 12–18 (2012).

Tapparel, C. et al. Rhinovirus genome variation during chronic upper and lower respiratory tract infections. PLoS ONE 6, e21163 (2011).

Jacobs, S. E., Lamson, D. M., Kirsten, S. & Walsh, T. J. Human rhinoviruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 26, 135–162 (2013).

Lewis-Rogers, N., Seger, J. & Adler, F. R. Human rhinovirus diversity and evolution: how strange the change from major to minor. J. Virol. 91, 10 (2017).

Simmonds, P. et al. Recommendations for the nomenclature of enteroviruses and rhinoviruses. Arch. Virol. 165, 793–797 (2020).

Simmonds, P. et al. Proposals for the classification of human rhinovirus species C in genotypically assigned types. J. Gen. Virol. 91, 2419 (2010).

Cooney, M. K., Fox, J. P. & Kenny, G. E. Antigenic groupings of 90 rhinovirus serotypes. Infect. Immun. 37, 642–647 (1982).

McIntyre, C. L., Knowles, N. J. & Simmonds, P. Proposals for the classification of human rhinovirus species A, B and C into genotypically assigned types. J. Gen. Virol. 94, 1791–1806 (2013).

Luka, M. M., Nanjala, R., Gatua, W., Rashed, W. M. & Awe, O. I. rhinotypeR: Rhinovirus genotyping. Bioconductor (2024).

Gentleman, R. C. et al. Bioconductor: Open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 5, R80 (2004).

Hornik, K. The comprehensive R archive network. WIREs Comput Stat. 4, 394–398 (2012).

Pagès, H., Aboyoun, P. & DebRoy, S. Biostrings: Efficient manipulation of biological strings. Bioconductor (2024).

Bodenhofer, U., Bonatesta, E., Horejš-Kainrath, C. & Hochreiter, S. msa: an R package for multiple sequence alignment. Bioinformatics 31, 3997–3999 (2015).

Ullrich, K. K. MSA2dist. Bioconductor (2025).

Paradis, E. et al. ape: Analyses of phylogenetics and evolution. (2024).

Jukes, T. H. & Cantor, C. R. CHAPTER 24 - Evolution of protein molecules. In Mammalian Protein Metabolism (ed. Munro, H. N.) 21–132 (Academic Press, 1969). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4832-3211-9.50009-7.

Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16, 111–120 (1980).

Luka, M. M. et al. Molecular epidemiology of human rhinovirus from 1-year surveillance within a school setting in rural Coastal Kenya. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 7, 385 (2020).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549 (2018).

Luka, M. M. et al. Rhinovirus dynamics across different social structures. Npj Viruses 1, 1–11 (2023).

Kamau, E. et al. An intensive, active surveillance reveals continuous invasion and high diversity of rhinovirus in households. J. Infect. Dis. 219, 1049–1057 (2019).

Morobe, J. M. et al. Human rhinovirus spatial-temporal epidemiology in rural coastal Kenya, 2015–2016, observed through outpatient surveillance [version 2; peer review: 2 approved]. Wellcome Open Res. 3, 128 (2018).

Morobe, J. M. et al. Spatio-temporal distribution of rhinovirus types in Kenya: a retrospective analysis, 2014. Sci. Rep. 14, 22298 (2024).

Zhao, P. et al. RVdb: A comprehensive resource and analysis platform for rhinovirus research. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D770–D776 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Data Science Strategy (ODSS) for their immense support before and during the April 2024 Omics codeathon organized by the African Society for Bioinformatics and Computational Biology (ASBCB).

Funding

No financial support was received for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MML conceived the original idea. MML, WMR, WG, and RN developed the pipeline for rhinotypeR. MML, WG, WMR, RN performed the bioinformatic analysis of the case study data, and drafted the manuscript. MML, WMR and OIA contributed to the writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript. OIA’s role was in the administration and supervision of the bioinformatics analysis in the project. OIA also provided the resources to facilitate and complete the study and provided guidance. OIA edited and reviewed the manuscript and provided critical feedback that helped shape the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luka, M.M., Nanjala, R., Rashed, W.M. et al. rhinotypeR enables reproducible rhinovirus genotype assignment from VP4/2 sequences. Sci Rep 16, 6149 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37050-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37050-8