Abstract

In the Basel III era, measuring, managing, mitigating and forecasting interest rate risk has become significant. In the first study of its kind, this paper develops a principal component analysis-based forecasting of interest rates of different maturities and stress testing approach in a univariate auto-regressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) framework in the context of India. Debating the existence of multiple representations of interest rates in the Indian market, the study broke down all the short-term, as well as long-term interest rates to derive the optimal principal component of unique interest rates. These unique interest rates are further exercised to forecast the future interest rates through the ARIMA model. The rolling average method was applied to the recently created Indian volatility index (VIX) to place the stress points. The model performance was examined over this stress point of building multiple scenario analysis. The study found that ARIMA (2-1-1) forecasting model of interest rates produced a better forecast result, both in the case of in-sample and out-of-sample performances as well as in stress periods. From the forecasting results, the study found that the proportionate gain in yield is higher as the maturity increases. By examining the stress period on the basis of eight quarters (2007: Q4 of 2009: Q3) rolling average on Indian volatility Indices, the survey concluded that the Indian economy will reach a stable situation signalled by less volatile interest rates post the second quarter of 2018.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The question of how interest rates on Treasury securities are likely to alter in future preoccupies financial market participants, who seek to profit from their prospects. This is equally a concern of policymakers: to choose an appropriate monetary and fiscal policy in a course with predicted future interest rates. Moreover, academicians use interest rate forecasts to predict the related macroeconomic variables, such as the circulation of the money supply, output, prices, inflation, net foreign investment, exchange rate, the intensity of exports and imports, domestic savings and investment and other economic actions. They also build term structure models that link interest rate forecast to the dynamics of risk premium. Apart from this, to the banks, the accuracy in the interest rates prediction ensures the efficient management of asset and liabilities. Interest rate prediction is a decision making ingredient for corporations while picking between equity, debt, and fixed income derivative products or choosing between a set and floating rate. The prediction of interest rate is likewise useful for interest rate swap trades. In the case of an investor, interest rate determines the value of a portfolio. Consequently, a robust forecasting interest rate model puts the investor in an advantageous place in the debt marketplace. The term structure of interest rates assesses the association among the yields on securities differing in their term to maturity only. The term structure encapsulates the market’s anticipation of upcoming events, by giving an entire interest rate schedule over time. The term structure gives the data regarding changes in the anatomy of the yield curve as a result of alterations in the underlying variables (Brown and Dybvig, 1987). The term structure concept is intertwined with the concept of the yield curve. According to Cano et al. (2010) “the yield curve, as a picture of relationships between the yields on bonds of different maturities, provides a way of understanding the common markets’ evaluation in the future, and whether the economy will be strong or weak”. The moves in interest rates rely on the term to maturity. Pereda (2009) emphasised, “the existence of the yield curve favours the development of domestic capital markets, primary and secondary, allowing the recovery of financial instruments”.

The objective of this study is to offer a unique new simple method of interest rate forecasting and stress testing in an environment where there is an existence of multiple representations of interest rates, especially in India. On that point is more than around 40 interest rates in the Indian market, such as deposit rate, prime lending rate, certificate deposits, commercial paper, interbank participation certificates, call money rate, bank rate, Repo rate and reverse Repo rate, cash reserve ratio and statutory liquidity ratio, treasury bills, zero coupon rate of different maturities, Mumbai Interbank bid/offer rate, yield on government securities, etc. to mention a few. In this setting, our model answers the prominent questions raised in the literature involving the data which are useful for forecasting interest rates; is it sufficient to consider past interest rates to predict their future or do we as well need to consider macroeconomic variables such as rising prices and production to forecast interest rates.

From the extensive review of empirical literature, it is found that the forecast method is employed directly on different interest rates independently without taking the other representation of short-term and long-term interest rates. Yet, in reality, interest rates are not independent among them, rather depend upon one another. To the best of our knowledge, this is perhaps the first study of its kind. This paper develops a principal component analysis based forecasting of interest rates of different maturities and stress testing approach in the univariate auto-regressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) framework for the period from Apr-2018 to Sep-2018 in the context of India. This model captures the dependency among the key interest rates without violating the problem of multicollinearity. In this context, our first contribution to the literature is the methodology. Side by side, we have identified the stress period to make the multiple scenarios based on the rolling average method of Indian volatility index (VIX) including the period of the global financial crisis. In the end, we have carried on the sensitivity analysis to test the potential influencing power of the unique interest rates.

Most of our results should be of grave concern to the Indian banks, policymakers and academicians. Foremost, we found that ARIMA (2-1-1) forecasting model of interest rates produced better forecast results in case of in-sample and out-of-sample performances as well as stress periods. The study forecasted that on an average, the yield on all short and long rates are anticipated to fall from the second quarter of 2018 onwards. The study also determines that the proportionate gain in yield is higher as the maturity increases, which is as per the economic intuition. The study likewise concludes that short-term rates are major drivers of interest rates than long-term rates in the Indian economy.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows. Section “Theories and empirical literature” presents the theoretical underpinnings and the empirical literature on the interest rate forecasting and stress testing. Section “Description of variables, data and the period of study” underlines the variables description, data and the period of the study. Section “Description of methodology” presents the methodology and the basic data analysis for further modelling. Section “Empirical results and discussions” discusses the estimated results and their corresponding economic interpretations. Section “Conclusion and policy implications” concludes the study by specifying the limitations and further scope of the study.

Theories and empirical literature

It has been observed from the literature in large and from market practices that interest rates for different maturities tend to move together over time. The yields on short-term bond are more volatile than yields on long-term bonds. The long-term yield tends to be higher than short-term yields. To explain these facts, the fixed income literature provides three theories, such as the expectations theory, the segmented market theory, and the liquidity premium theory. The key assumption behind the pure expectations theory is that buyers of bonds do not prefer bonds of one maturity over another, so they will not hold any quantity of a bond if its expected return is less than that of another bond with a different maturity. Bonds that have this characteristic are said to be perfect substitutes. It is important to note here that both inflation and interest rate risks make long-term bonds different from the short-term bonds. Therefore, this theory essentially assumes away inflation and interest rate risk.

The segmented market theory assumes that markets for different maturity bonds are completely segmented. The interest rate for each bond with a different maturity is then determined by the supply of and demand for the bond with no effects from the expected returns on other bonds with different maturities. Thus, the bonds of different maturities are not substitutes at all, so the expected returns from a bond of one maturity have no effect on the demand for a bond of another maturity. This is because bonds of shorter holding periods have lower inflation and interest rate risks, segmented market theory predicts that yield on longer bonds will generally be higher. The liquidity premium theory views bonds of different maturities as substitutes, but not perfect substitutes. Investors prefer shorter rather than longer bonds because they are free of inflation and interest rate risks.

There are ample empirical studies on the analysis of the relationship between yield, term to maturity and credit rating of the bonds. The pure expectation theory is predominantly exploited to forecast the future interest rates by analysing the spot rates through bootstrapping procedures (Campbell, 1991; Campbell and Shiller, 1987; Hansen and Sargent, 1980; Watson, 1999). Fisher (1930), and Hicks (1953) have formulated expectation theory which is relevant in the current context of studying term structure of interest rate modelling and provides a good approximation of the factors that determine long-term interest rates. According to them, “long-term interest rate is determined by expectation on the future short-term interest rates”. Cox et al. (1985) have used the framework of general equilibrium for developing the process of short-term interest rates. Fama (1990) has studied the relationship between term structure interest rates, inflation and real returns. Litterman and Scheinkman (1991) have used principal component analysis (PCA) technique in order to observe the factors that affect term structure interest rate movements. Principal components (PCs) have been calculated on the basis of 10 different interest rates. However, they have concluded that 99 percent of the total variation in the interest rates is explained by three specific factors, popularly called, level, curvature and steepness. Bodie et al. (1997) have mentioned that the determination of the interest rate level is of immense importance to gauge the investment’s performance while exploring investment opportunities. McConnell and Brue (1997) have shown that interest rates may be considered as the price of money usage. Campbell and Shiller (1987) concluded that the monetary authorities have to manipulate the money supply in order to influence the interest rates and subsequently alter the level of employment, output and prices. This makes the term structure of interest rate, an administered price. McConnell and Erwin (1997) have shown in capital markets, the premium offered or required for capital and investment allocation between lenders and borrowers in the most productive and profitable manner can be termed as the interest rates.

Bin Chen and Zhaogang Song (1999) have used the non-parametric procedure for testing diffusion in the time series process. They tried to find a way to represent the underlying interest rate series in the form of a stochastic differential equation. They have used a diffusion model which is based on a martingale process, in which a spectral derivative test was applied in order to check the property of martingale. D’Arcy et al. (1999) have approached a simulation technique in order to choose the parameters that can be used for analysing the historical movements of interest rates. They used a monthly short-term and long-term interest rates from the period Jan-53 to Nov-99. However, they concluded that no unique parameter exists which can be fitted to the movements of all rates. Fauvel et al. (1999) applied various empirical models for forecasting interest rates and coping with the result of VAR, VECM, enabling an integrated treatment of both short-term and long-term rates and their relationship. According to them multivariate model provides better forecast than univariate models. Neftci (2000) stated that the movement of bond price rests on the stochastic behaviour of the future and current spot rates in the economy. Thus, there exists a functional relationship between bond prices and the future and current spot rates. Dua et al. (2008) compared various interest rate forecasting models including VAR, BVAR, ARIMA and came up with the result that BVAR performs better result than other models in the long-term analysis. Vereda et al. (2008) tried to forecast both short-term and long-term interest rates in a VAR framework for the Brazilian economy. By using monthly data from July-1999 to May-2007, they estimated four different VAR model to predict future interest rates. It was concluded that predicting short-term interest rate in a VAR framework is not as meaningful as predicting the long-term interest rates.

In a nutshell, the findings of the above studies reveal the existence of a relationship between short-term and long-term interest rates. The Nelson Siegel Model provides a better approach to modelling the yield curve. While a few studies conclude that the univariate model provides a better forecast of interest rates, others postulate the superiority of a multivariate model in forecasting. This paradox has been empirically examined in this paper.

Description of variables, data and the period of study

The present study deploys monthly time series data of different interest rates, such as, up to 14 days treasury bill (TBILL-14D), 15–91 days treasury bill (TBILL-91D), 92–182 days treasury bill (TBILL-182D), 183–364 days treasury bill (TBILL-364D), call money rates (CMR), one year government dated security (GDSY1), two years government dated security (GDSY2), three years government dated security (GDSY3), four years government dated security (GDSY4), five years government dated security (GDSY5), 10 years government dated security (GDSY10) and 15 years government dated security (GDSY15) in India, over 219 months (Jan-2000–Mar-2018). The data is sourced from the RBI Handbook of Statistics on Indian economy 2017–18. However, the sample periods and the number of variables are chosen on the basis of availability of time series data and variables. Interpolation (both linear and non-linear) method and outliers treatment were conducted on the initial stage of analysis. Table 1 explains the variables and data considered in the study.

Description of methodology

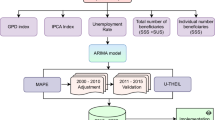

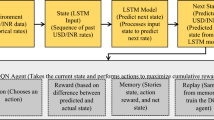

This section presents the interest rates model, which is designed to forecast the future direction, as well as the level of the interest rates for India. For this purpose, the univariate ARIMA model has been used. The mechanism consists of three steps. In the first step, it decomposes all the interest rates mentioned above using PCA and then, the optimal PC is modelled using ARIMA techniques. Finally, all the PCs are reverted back to the original interest rates level. Apart from this, the rolling average method has been applied to the Indian volatility index (VIX) to figure out the stress period and the model performance has been judged over this stress period. Similarly, other model selection criteria are implemented to support the robustness of the proposed model. In addition to this, the impact of one of the interest rates over other rates has studied under sensitivity analysis. It is very intuitive that, most of the interest rates are non-stationary. Therefore, the entire variables test for stationarity and a suitable transformation (first difference) is applied to overcome the unit root test issue. Table 2 represents the methodology used in this study.

Descriptive statistics

We have incorporated the first four moments of the included interest rates. The first moment (mean) and second moment (variance) represent the centre of location and dispersion of the series. Similarly, the third moment (skewness) and fourth moment (kurtosis) are used to test the normality nature of the interest rates series. Apart from this, the historical maximum and the minimum values of the respective interest rates along with their corresponding dates are provided.

Correlation analysis

This study, conducted the correlation analysis, among the different maturity-based interest rates, through the Spearman’s method of correlation. In order to test whether the estimated coefficient of correlation is statistically significant or not, this study has used Student’s test statistic (t-test) for the estimated coefficient of correlation.

where \(\widehat \rho\) is Spearman’s estimated coefficient of correlation, D is the difference in rank and n is the total number of observations.

Null hypothesis: ρ = 0. Alternative hypothesis: ρ ≠ 0

If the p-value of the test statistic is <0.05, then we do not have sufficient evidence to accept the null hypothesis at the 5 percent level of significance. On the other hand, if the p-value of the test statistic is more than 0.05, then we do not have sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis at the 5 percent level of significance.

Principal component analysis

PCA is a powerful statistical tool used in a variety of real-life systems. It assumes that the multitude of factors that affects a system can be precisely summarised by a few sets of interrelated artificial variables called principal components (PCs). This reduction in variability is very useful in finance, especially interest rate, modelling, since there are more than 40 representations of interest rates existing in the Indian context. It is a tedious procedure to model them individually. Thus, instead of considering all the variables, we can use one optimal PC which will be able to explain all the necessary characteristics of all the existing population interest rates. The PC has been performed using the following steps:

\({X} = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {x11} & \cdots & {x1m} \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ {xn1} & \cdots & {xnm} \end{array}} \right)\) represents the raw data having “n” number of observations and “m” number of variables. The data have to be normalised before the PCA, to bring all the variables to the same level for comparison.

C = XTX is a symmetric matrix of order (M × M) called the variance and covariance matrix.

Now we will get ‘M’ Eigenvalues and ‘M’ corresponding eigen vectors. i.e.

\(M_i \in R,\forall i = 1,2,3, \ldots m\) are the eigenvalues.

\(V_i \in R,\forall i = 1,2,3, \ldots ..m\) are the eigen vectors of order (m × 1)

\({W} = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {v11} & \cdots & {vm1} \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ {vm1} & \cdots & {vmm} \end{array}} \right)\) is the weighted matrix combined with row bind manner.

Now the PCs are obtained by multiplying C with W

The optimal PC can be judged on the basis of eigenvalue >1.

The level value (original interest rates) can be extracted from the PC values as

where scale indicates respective standard deviations and centre stands for the respective mean of the raw data.

Unit root analysis

As most of the time series variables suffer from the non-stationary problem, we have tested for unit root under three different tests, namely, augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test, Phillips–Perron (PP) test and Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt and Shin (KPSS) test. Since at least two tests are not satisfied the assumption of stationary of optimal PC, we have transformed the optimal PC value as I (1). Table 3 shows the Null and Alternative hypothesis of respective unit root tests.

Auto-regressive moving average

ARIMA process is a mixed process, which contains both auto-regressive (AR), as well as moving average (MA) factors and has got popularity due to univariate time series forecasting. The order of the ARIMA has been chosen on the basis of auto-correlation function (MA components) and partial auto-correlation function (AR components), as well as various information criteria like AIC, BIC, etc. in both cases. In general, ARIMA (p,0,q) can be expressed as

where xt is the underlying time series x at period t. α's and β’s are parameters. εt is the white noise error term at period t.

Thus, once we know the order of ARIMA and probability distribution of εt, we can easily estimate parameters of ARIMA (p- d- q) process by using ordinary least square (OLS) or maximum-likelihood estimation (MLE) so that the estimates are at least asymptotically efficient. Estimated parameters of an ARIMA (p, d, q) model can be used for forecasting underlying time series. On the basis of various information criteria, we have selected the ARIMA (2-1-1) model without drift.

Let the estimated parameters be: β1*, β2*, and θ1*.

Now, the forecast value for j period ahead will be

where xt+j−1 is the actual predicted values but for j > 2 we can use forecasted values instead of actual predicted values.

Rolling average method

Rolling average (eight quarter basis) has been used in the VIX in order to capture the stress period and later we have plotted actual values with their predicted values for measuring the performance of our model under stress period. In addition to this, model performance metrics (RMSE, MSE, MAPE, and RMSE/SD) are calculated for stress periods in order to check the stability of the model during this period.

Model performance criteria

Model performance criteria imply how well an estimated model fit the data generating process (DGP). We have used certain diagnostic tests for looking at the performance of our estimated ARIMA model, which includes normality, stability, auto-correlation, AIC, BIC, SIC, etc. Apart from these, in-sample and out-of-sample tests are an integral part of the model performance criteria, especially, when the model is built for forecasting. In the case of in-sample test, we usually compare the estimated value with actual values for the whole sample period. Nevertheless, in out-of-sample situation, this study compares estimated values with the actual values for a selected sample period and not the whole sample period. Thus, we start comparing the performance of the model on the basis of increasing sample periods up to the entire sample period. For example, we have total ‘n’ sample periods. First, we estimate the model using sample “n−h” (where h < n), and then compare the actual values with the estimated values. In the second step, we estimate the same model using the sample (n−h + 1), and then compare the actual values with the estimated values. Similarly, in the third step, we estimate the same model by using the sample (n−h + 2), then compare estimated values with actual values and so on. In this way, we can do ‘h’ step ahead forecast. If the actual values are very close to estimated values at every step, then we can say that our model performs well for forecasting and hence, can be accepted. In addition to this, at each step, root mean square error (RMSE) has been calculated and their consistency over the ‘h’ periods has been studied. However, the criterion for the satisfying model is RMSE over SD being <1. That is the root mean square error of various interest rates is less than their respective standard deviation.

Sensitivity analysis

This technique has been applied to determine the impact of one interest rate over another. It means that how does a unit change in ith interest rates affects jth interest rates and subsequently the performance metrics such as RMSE, MAE, MAPE and RMSE/SD. A unit change in ith rates will change the value of the optimal PC and changes in optimal PC values will lead to changes in interest rates. This is because optimal PC value is the linear combination of interest rates.

where PC is the optimal principal component. βi is the coefficients of ith interest rates. Ri is the ith rate of interest.

However, a unit change in ith interest rates will change the optimal PC value by βi units.

Empirical results and discussions

This part includes the result of trend analysis, descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, PCA, ARIMA (2-1-1), stress testing, model performance test and sensitivity analysis.

Trend analysis

Trend analysis helps us to recognise how the underlying interest rates move; upward, downward or remains constant over the period of time. If the tendency of an interest rate seems to be upward, then it is anticipated that the future movement might follow an upward pattern. Similarly, other things remaining constant, a downward pattern might imply, in the coming future, the underlying rates will follow a downward movement. Still, a constant movement of trend might foretell unchanged values of the underlying rates. The trend paths of all the interest rates included in our model are presented in Figs. 1 and 2. In these figures, the Y-axis measures the percentage interest rates per annum and X-axis measures months over the period of time. All the short rates are moving together over the period of time. This implies that the change in the yields of the different maturity bonds tends to move in the same direction. Initially, all the short rates are moving downwards till the first quarter of 2004 complied by their increase up to quarter four 2007 and then a decrease during the year 2008–09. Nonetheless, after the second quarter of 2010, they are following an increasing trend and during the end of 2015–17, again they are diminishing. During the period of financial crisis (2007–08), interest rates seem to be fluctuating around the trend and became more volatile. Among all the short rates, call money rate seems to be more volatile during this crisis period.

Similarly, all the long-term rates are moving together over the period of time, which implies the existence of a correlation between different long rates (Two Years GDS, Three Years GDS, Four Years GDS, Five Years GDS, Ten Years GDS and Fifteen Years GDS). Initially, all the above rates decrease up to the second quarter of 2003, then increase till the period of financial crisis (2007–08). After the crisis, they again move upward and then remain constant till mid-2013. In the end, they seem to decrease towards the end of 2017. Still, this figure also confirms one of the assumptions of the pure expectation theory of interest rates, which states that interest rates of different maturities move together and yield of short rates is less than the long rates.

To begin with, as most of the variables are considered in this study are time series in nature, the study has conducted the χ2 goodness-of-fit test in order to determine the seasonality pattern among the interest rate series. The logical rationale behind this method is because of its appropriate mathematical theory, which builds it easy to calculate and understand. The test is on whether the empirical data can be a sample of a certain distribution with sampling error as the only source of variability. This test requires a sample from a population with an unknown distribution function F(x) and a certain theoretical distribution function F0(x). Although there is no restriction on the underlying distribution, usually the hypothetical distribution is a uniform distribution. For seasonality studies, the frequency Oi, i = 1, 2,…, k is the observed value at the ith season, while the frequency Ei, i = 1, 2,…, k is the expected cell frequency at the ith season. The null hypothesis under this test is specified as that there is no seasonal effect (i.e., F0(x) is a uniform distribution). The results of the seasonality are reported in Table 4.

The outcomes from Table 4 depict the outcome of χ2 test used to detect the seasonality in interest rates series. Probability values of corresponding interest rates (in column 3), is >0.05 level of significance, therefore we do not have sufficient statistical evidence to reject the null hypothesis (underlying time series does not suffer from seasonal effect). Therefore, there is no seasonality in the interest rates series that are considered in this paper for further empirical analysis.

Summary statistics

The summary statistic includes mean, variance, skewness, kurtosis and the Jarque–Bera (JB) test statistic (used for normality testing) for all the interest rates are mentioned in Table 5. Using the 219 observations, the study compares this test statistic among the underlying interest rates. Similarly, Table 6 indicated the historical maximum and minimum values along with their corresponding months of all the short-term and long-term interest rates.

Table 5 depicts the summary statistic of different interest rates, which include mean, variance, skewness and kurtosis popularly called first four moments and their corresponding probability value (p-value) of JB test statistic. The total number of observations is 219, well enough for hypothesis testing. The mean of short rates is less in comparison to the mean of long rates. This is because long-term securities are riskier than short-term securities and hence possesses more returns. Within the same group, the mean is almost the same for the different categories of rates. For example, mean of short rates and long rates are almost equal within themselves and different between the groups. By looking at the variance column, we can see that the long rate group possesses less variance than the short rate group, which indicates that over the period of time, short rates have a higher volatility as compared to long rates. The fourth column shows the skewness value which explains that, except TBILL(91D) and TBILL(182D) all the other rates are positively skewed. It means that most of the values of (91D) and T-BILL(182D) fall on the left side of a normal curve, whereas most of the values of other rates fall on the right side of the normal curve. The fifth column tells about the flatness or peakedness of the underlying series. Those variables that possess values <3 in fifth column come under platykurtic category and it seem that, all the variables are platykurtic in nature. The sixth column indicates the p-values of the JB test statistic, used for the normality assumption. The p-values more than 0.05, indicate that, the underlying variables are normally distributed with finite mean and variance at 5 percent level of significance. In this study, except, CMR, GDSY10 and GDSY15, all other rates are normally distributed.

Table 6 presents historical maximum and minimum values of all the interest rates along with their months in our study period. The maximum value of CMR was 14.07% on Mar-2007 and the minimum value of it was 0.73 percent on Jul-2007. 12.63 percent and 2.60 percent were the historical maximum and minimum value of TBILL(14D), respectively, on Aug-2000 and May-2009. Similarly, the maximum value of TBILL(91D) was 11.14 percent on Aug-13 and the minimum value was 3.12 percent on Jun-2009 and so on. Interestingly, in most of the cases, either maximum or minimum historical value occurred in the third quarter of a year.

Correlation analysis

The study constructs a correlation matrix among different interest rates, by using the Spearman Rank correlation method. The main diagonal elements of the matrix imply a variable related to itself (\({a}_{{ij}}\forall \,{i = j}\)) and the off-diagonal elements imply interest rates ‘i’ related to interest rates ‘j’ (\({a}_{{ij}}\forall \,{i} \,\ne\, {j}\)). The lower triangular matrix represents the correlation of coefficients between i and j rates.

Spearman’s method of rank correlation is a non-parametric approach to examine the significance of the coefficient of correlation. In this study, it is hard to place the actual distribution followed by the multiple representations of interest rates for both short term and long term that are considered for further empirical analysis. Thus, a non-parametric test is selected to be conducted which will offer a better result than those of the parametric tests are available in the econometric literature. Hence, we have used Spearman’s rank correlation test.

Table 7 presents the correlation matrix of different interest rates. In most of the cases, the correlation seems to be very strong (more than 80%) and statistically significant at the 5 percent level of significance. All the rates are positively associated with each other. CMR and TBILL(14D) are positively related to each other and the degree of association between them is 92 percent and statistically significant at 5 percent. This implies that, out of 100 times, there are 95 cases where both CMR and TBILL(14D) increase or decrease at a time. Similarly, the correlation between TBILL(91D) and CMR is very strong and statistically significant, i.e. around 94 percent and so on.

Principal component analysis

This study uses 12 different interest rates, such as CMR, TBILL(14D), TBILL(91D), TBILL(182D), TBILL(364D), GDSY1, GDSY2, GDSY3, GDSY4, GDSY5, GDSY10 and GDSY15. Thus, 12 PCs are calculated and the optimal interest rates PCA is judged on the basis of standard deviation (SD) or eigenvalues and the proportion of the variance explained by the component.

Table 8 depicts the details of the PCA for interest rates. For 12 interest rates, 12 PCs are produced (PCi for i = 1,2,….,12), where all the PCs are orthogonal to each other. Out of 12 PCs, only the first two PCs (PC1 and PC2) are relevant to our study as their standard deviations are more than one. The first component explains about 87.85 percent variation in the entire interest rates series and the second component explains about 7.38 percent variation in the entire interest rates series and hence along. First and second PCs cumulatively explain about 95.24 percent variation in the entire interest rates series. Similarly first, second and third components explain about 97.39 percent of the total variation in the interest rates and so on. Nevertheless, the present study used only the first PC (PC1) for analysis because of its higher explaining power, which is more than the any other components and having eigenvalues more than one. That is about 87.85 percent (for more details please see appendix section-7).

Unit root analysis

We have used three different types of unit root test called “Augmented Dickey–Fuller test, Phillips–Perron test and Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt, and Shin test”. The null hypothesis under ADF and PP test is that the ‘underlying time series has a unit root’, while the KPSS test assumes that ‘the underlying time series has no unit root’. However, the optimum PC (PC1) is subject to the test of unit root both at its level and first difference.

Table 9 represents p-values of KPSS, ADF, PP test corresponding to the PC1 values at its level [PC1 at I(0)] and first difference [PC1 at I(1)]. The p-values corresponding to PC1 at I (0) of KPSS, ADF and PP imply that the underlying PC1 is not stationary at its level. Similarly, the p-value of these three tests corresponding to PC1 at I (1) indicates, PC1 is stationary at its first difference.

Autoregressive integrated moving average model

The present study employed the ARIMA (2-1-1) model for forecasting interest rates by using optimal PC values of interest rates. Initially, optimal PC values (PC1) are forecasted from the period of Apr-2018–Sep-2018 and then the actual interest rates are calculated from this optimum forecasted PC value. The optimum order of the ARIMA model is based on the lowest information criteria values which include AIC, BIC and SIC. The model diagnostic tests, including normality, auto-correlation, white noise, in-sample and out-of-sample performance are conducted to examine the robustness of the forecasting model.

By satisfying all the necessary assumptions of ARIMA (Please see appendix section-8), PC1 possesses ARIMA (2-1-1) without drift. The Z-statistics for each coefficient is calculated by dividing the coefficient with its standard error. The p-values associated with AR(1) and MA(1) are <0.05 and hence, statistically significant at the 5 percent level (Table 10). But the p-value corresponding to AR(2) is not statistically significant. The idea of keeping AR(2) in this model helps better out of the sample and in-sample predictions, as well as satisfied model stability conditions (thus it is better to include irrelevant variable than to omit relevant ones-Basic Econometrics by D. Gujurati, 4th edition, PP.518).

It is evident that except normality, other assumptions are satisfied. However, according to the central limit theorem, if we increase the sample size, normality issue can be solved. Apart from this, as a White Noise test is satisfied, normality is not a big issue. In addition to this, RMSE, MAE, MAPE, LL, and AIC values of this model are acceptable. The model also satisfies stability conditions (absolute value of AR coefficients should be <1 and absolute values of sum of MA coefficients should be <1). Thus, by looking at the significance level of coefficients and the output of model assumptions, the above ARIMA (2-1-1) model is acceptable for forecasting purposes.

In-sample model performance of ARIMA (2-1-1) model

The in-sample performance of the ARIMA (2-1-1) includes the values of, RMSE, MAE, MAPE, LL, and AIC. Lower the value of an above statistic, the better is the model execution. By using the estimated coefficients of the ARIMA (2-1-1) model, the predicted or fitted values of optimum PC values (PC1) are computed. Then, predicted interest rate values are derived from the predicted PC1. Actual interest rates are plotted against predicted rates derived from fitted optimum PC1 values. The comparative plot reveals that both the values (actual and predicted) are close to each other. This indicates that the above ARIMA (2-1-1) model is statistically accepted in the domain of in-sample analysis.

Table 11 depicts in the sample metric of the ARIMA (2-1-1) model. The performances of all in sample parameters are acceptable. Particularly, corresponding to all the interest rates along with PC1, the criteria of RMSE over SD being <1 is satisfied. The in-sample performance (ARIMA 2-1-1) of optimal PCs and interest rates are represented in Figs 3 and 4, respectively. The Y-axis and the X-axis show IR (% per annum) and monthly time, respectively. The blue and red lines show the actual and predicted values of interest rates, respectively. It appears that both the lines are very close to each other in case of all the rates resulting in no significant difference between the actual and predicted values. Thus, the above ARIMA (2-1-1) model produces good ins-sample performances over the entire historical series.

Stress testing of ARIMA (2-1-1) model

Initially, the stress period has been selected on the basis of eight quarters rolling average of the VIX. Now, the stress period will be that eight quarters, which possesses the highest rolling average of the VIX. Fig. 5 shows the maximum rolling average value was reached at 2009: Q3. Therefore the stress periods will be starting from eight quarters before 2009: Q3. It means that Oct-2007–Sep-2009 is the stress period in our study. This makes sense as the financial crisis hit the economy during 2007–08. The performances of ARIMA (2-1-1) model during the stress period depend on the historical actual and predicted series of the interest rates and the values of RMSE/SD being <1. So we have plotted actual values vs. predicted values of the PC1 during this period, and calculated performance metrics during these periods. During the period of stress (Oct-2007–Sep-2009), it is observed that, actual and predicted values are not only close to each other but also moving in the same direction.

Table 12 depicts in the sample metric of the ARIMA (2-1-1) model during stress periods. The performances of all in sample parameters are acceptable. Particularly, corresponding to all the interest rates along with PC1, the criteria of RMSE over SD being <1 is satisfied. Therefore, the above model is reliable even in a stress period.

Out of sample performance of ARIMA (2-1-1) model

We have used 13 periods ahead out-of-sample comparison of the proposed ARIMA (2-1-1) model. Tables 12 and 13 show the out-of-sample performance metrics of optimal PC (PC1) and interest rates, respectively.

Tables 13 and 14, show the out-of-sample performance of the proposed model. At the first stride, we have estimated the model by using sample data from Jan-2000 to Apr-2016 and tested the model performance of the different sample (called out-of-sample) May-2016–Apr-2017. Likewise, in the second measure, the model is estimated by incorporating samples from Feb-2000 to May-2016 and testing the model performance on Jun-2016–May-2017 and so on. The performance of out-of-sample parameters (RMSE, MAE, and MAPE) is very consistent over different sample horizons. Apart from this, our proposed model satisfies the out-of-sample criteria, such as the AVERAGE RMSE over SD being <1. Thus, overall, it may be concluded that ARIMA (2-1-1) model produces good forecast results in case of out-of-sample performances.

Sensitivity analysis

The idea behind sensitivity analysis is that, how does prediction value changes if one of the interest rate changes. For example, how makes the prediction of other rate changes, if CMR changes by one unit. The accompanying tables show the changes in model performance metrics (RMSE and RMSE/SD) of all the rates due to unit changes in one of the rates along with their former values.

Table 15 shows changes in the values of RMSE and RMSE/SD of all the interest rates due to unit positive shock given to CMR. Interestingly, it can be seen that a unit positive shock in CMR leads to decrease in both RMSE and RMSE/SD values of all the rates including PC1. This implies increasing predicted values of interest rates. In other words, when unit positive shock is provided to CMR, all the interest rates are likely to move positively and less than unit and vice versa.

Table 16 indicates a unit positive shock in TBILL(14D) leads to a decrease in both RMSE and RMSE/SD values of all the interest rates. This implies an increase in the predicted values of interest rates. In other words, when unit positive shock provided to TBILL(14D), all the interest rates are likely to move positively and less than unit and vice versa.

Table 17 indicates one unit positive shock in TBILL(91D) leads to a decrease in both RMSE and RMSE/SD values of all the rates. This means an addition in the predicted values of all the interest rates. In other words, when unit positive shock provided to TBILL(91D), all the interest rates are like to move positively and less than unit and vice versa.

Similarly, Table 18 indicates a unit positive shock in TBILL(182D) leads to a decrease in both RMSE and RMSE/SD values of all the rates. This implies an increase in the predicted values due to positive shock is given to TBILL(182D). In other words, when a unit positive shock provided to TBILL(182D), all the interest rates are like to move positively and less than unit and vice versa.

Table 19 indicates a unit positive shock in TBILL(364D) leads to a decrease in both RMSE and RMSE/SD values of all the rates. This means an addition to the increase in the predicted values of interest rates due to the positive shock is given to TBILL(364D). In other words, when a unit positive shock provided to TBILL(364D), all the interest rates are like to move positively and less than unit and vice versa.

Table 20 reports a unit positive shock in GDSY1 leads to a fall in both RMSE and RMSE/SD values of all the rates including PC1. This implies an increase in the predicted values of all the rates due to positive shock is given to GDSY1. In other words, when unit positive shock provided to GDSY1, all the interest rates are like to move positively and less than unit and vice versa.

Table 21 indicates a unit positive shock in GDSY2 leads to decrease in both RMSE and RMSE/SD values of all the rates including PC1. This implies an increase in the predicted values of all the rates due to positive shock is given to GDSY2. In other words, when unit positive shock provided to GDSY2, all the interest rates are like to move positively and less than unit and vice versa.

Table 22 indicates a unit positive shock in GDSY3 leads to decrease in both RMSE and RMSE/SD values of all the rates including PC1. This implies an increase in the predicted values of all the rates due to positive shock given to GDSY3. In the other words, when unit positive shock provided to GDSY3, all the interest rates are like to move positively and less than unit and vice versa.

Table 23 indicates one unit positive shock in GDSY4 leads to decrease in both RMSE and RMSE/SD values of all the rates including PC1. This implies an increase in the predicted values of all the rates due to positive shock is given to GDSY4. In other words, when unit positive shock provided to GDSY4, all the interest rates are like to move positively and less than unit and vice versa.

Table 24 indicates unit positive shock in GDSY5 leads to decrease in both RMSE and RMSE/SD values of all the rates including PC1. This implies an increase in the predicted values of all the rates due to positive shock given to GDSY5. In the other words, when unit positive shock provided to GDSY5, all the interest rates are like to move positively and less than unit and vice versa.

Table 25 indicates one unit positive shock in GDSY10 leads to decrease in both RMSE and RMSE/SD values of all the rates including PC1. This implies an increase in the predicted values of all the rates due to positive shock is given to GDSY10. In other words, when unit positive shock provided to GDSY10, all the interest rates are likely to move positively and less than unit and vice versa.

Table 26 indicates a unit positive shock in GDSY15 leads to decrease in both RMSE and RMSE/SD values of all the rates including PC1. This implies an increase in the predicted values of all the rates due to positive shock given to GDSY15. In the other words, when unit positive shock provided to GDSY15, all the interest rates are likely to move positively and less than unit and vice versa.

Forecasting interest rates

On the basis of sample period Jan-2000–Mar-2018, 12 different interest rates values, as mentioned above, are forecasted using the ARIMA (2-1-1) model in a reverted manner (forecasted from PC1 values) for the period Apr-2018–Sep-2018.

From Table 27, it can be noted that on an average CMR will increase from 5.70% in 2018: Q2 to 5.72% in 2018: Q3. TBILL(14D) will increase from 5.66% in 2018: Q2 to 5.67% in 2018: Q3 on an average. Similarly, on an average yield on TBILL(91D) will increase from 5.86% in 2018: Q2 to 5.87% in 2018: Q3. TBILL(182D) will increase from 6.11% in 2018: Q2 to 6.12% in 2018: Q3 on an average. On an average yield on TBILL(364D) will increase from 6.20% in 2018: Q2 to 6.21% in 2018: Q3 and so on. Broadly, we can see that on an average all the rates will increase by 0.1% from 2018: Q2 to 2018: Q3. It can be also watched that as maturity increases, the yield increases and vice versa, which satisfies the standard economic intuition.

Conclusion and policy implications

The broad aim of this study is to forecast interest rates of different maturity using PCA and stress testing. The study forecasts future interest rates from Apr-2018 to Sep-2018 by using ARIMA (2-1-1) method. Twelve different interest rates namely Call Money Rate (CMR), Yield on up to 14 days treasury bill (TBILL.14D), Yield on 15–91 days treasury bill (TBILL.91D), Yield on 92–182 days treasury bill (TBILL.182D), Yield on 183–364 days treasury bill (TBILL.364D), One Year Government Dated Securities (GDSY1), Two Years Government Dated Securities (GDSY2), Three Years Government Dated Securities (GDSY3), Four Years Government Dated Securities (GDSY4), Five Years Government Dated Securities (GDSY5), Ten Years Government Dated Securities (GDSY10), and 15 Years Government Dated Securities (GDSY15) are forecasted for the next eight months. Agreeing to the forecasted results, all the rates are increased by 0.1 percent from 2018: Q2 to 2018: Q3 on an average. The average CMR on 2018: Q2 will be 5.70 percent per annum, which is near to realising repo rate (6 percent) (Apr-2018, RBI report). Likewise, on Q3-2018, the average CMR is predicted as 5.72 percent per annum.

The study found that ARIMA (2-1-1) forecasting model of interest rates produced better forecast results in case of both in-sample and out-of-sample performances. The study forecasted that on an average, the yield on all short and long rates are anticipated to increase by 0.1 percent from 2018: Q2 to 2018: Q3. The survey also determines that the proportionate gain in yield becomes higher as the maturity increases, which is as per the economic intuition. The survey concludes that the Indian economy will reach a stable situation signalled by less volatile interest rates during the second and third quarter of 2018.

The issue of sensitivity analysis reveals that shock to CMR and TBILL(91D) has an equal impact on other rates. Similarly, a shock to TBILL(14D), TBILL(182D), and TBILL(364D) have equal influence on other interest rates. In accession to this, a positive unit shock to any of the interest rates leads to an increase in the other interest rates less than proportionately and vice-versa. Shock to longer-term rates has a lower impact on other rates than a shock to the short-term rates.

This study does not include all the interest rates due to the lack of data. Repo and Reverse Repo are not the part of our study because both the series is taking after a flat shape, which might create a problem in the model estimation. This study can be further widened to the advanced stochastic interest rate models like the Vasicek model, Dothan Model, and Cox–Ingersoll–Ross model.

Data availability

All datasets analysed or generated are included in the paper.

References

Arcy D, Gorvett R (1999) Parameterizing interest rate models. Casualty Actuarial Society Forum Summer: 1–50

Bodie Z, Kane A, Marcus AJ (1997) Investments. McGraw-Hill Irwin, New Delhi

Brown SJ, Dybvig PH (1987) The empirical implications of the Cox, Ingersoll, Ross theory of the term structure of interest rates. J Financ 41(3):717–730

Butter FA, Jansen PW (2004) An empirical analysis of the German long-term interest rate. Appl Financ Econ 14:731–441

Campbell JY (1991) A variance decomposition for stock returns. Econ J 101(405):157–179

Campbell JY, Shiller RJ (1987) Cointegration and tests of present value models. J Political Econ 95(5):1072–1088

McConnell CR, Brue SL (1997) Economia Laboral. McGraw-Hill

Cano C, Correa R, Ruiz L (2010) La curva de rendimientos y la toma de decisiones financieras. Revista Moneda, N° 145

Chen B, Song Z (1999) Testing whether the underlying continous time process follows a diffusion: an infinitesimal operator-based approach. J Econometrics 173(1):83–107

Cox JC, Ingersoll JE,Jr, Ross SA (1985) A theory of the term structure of interest rates Econometrica 53(2):385–407

Dua P, Raje N, Sahoo S (2008) Forecasting interest rates in India. J Appl Econ Res 2(1):1–41

Fama E (1990) Term structure forecasts of interest rates, inflation, and real returns. J Monet Econ 25:59–77

Fauvel Yvon Alain, Paquet, Zimmermann Christian (1999) A survey on interest rate forecasting. Working paper 87

Fisher (1930) Irving Fisher, the theory of interest as determined by impatience to spend income and opportunity to invest it. The Online Library of Liberty

Hansen P, Sargent TJ (1980) Formulating and estimating dynamic linear rational rational expectation model. J Econ Dyn Control 86(2):7–46

Hicks JR (1953) An Inaugural Lecture. Oxford University Press. 5(2):117–135

Litterman R, Scheinkman JA (1991) Common factors affecting bond returns. J Fixed Income 1:54–61

McConnell JJ, Erwin GR (1997) To Live or Let Die? An empirical analysis of piecemeal voluntary corporate liquidations. J Corp Financ 3(4):325–354

Neftci SN (2000) Value at risk calculations, extreme events and tail estimation. J Deriv 7(3):23–37

Pereda J (2009) Estimación de la Curva de Rendimiento Cupón Cero para el Perú. Banco Central dereserva del Perú, Revista Estudios Económicos N° 17

Pindyck RS, Rubinfeld DL (1997) Econometric models and economic forecasts. McGraw-Hill, New Delhi

Vereda et al. (2008) Estimating VAR models for the term structure of interest rates. Insur Math Econ 42:548–559

Watson M (1999) Combination forecasts of output growth in a seven-country data set. J Forecast 23:405–430

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mallick, A.K., Mishra, A.K. Interest rates forecasting and stress testing in India: a PCA-ARIMA approach. Palgrave Commun 5, 32 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0236-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0236-7