Abstract

This study explored the patterns of economic abuse among working married women from rural and urban areas in Jordan, and identified their experiences with other abuses interconnected with economic abuse, including psychological, emotional, and physical abuse and harassment. A quantitative research approach using a descriptive comparative design was employed. The findings indicated that 55.5% of urban and 44.5% of rural women have encountered spousal economic abuse in two ways: (1) controlling their economic resources and managing their financial decisions and (2) exploiting their economic resources. Economic abuse was found to be intertwined with other forms of abuse; women who faced economic abuse also endured primarily emotional and psychological abuse, followed by physical abuse and harassment, as tactics to reinforce economic abuse and maintain control over them. The most common form of psychological abuse was being made to feel frustrated and neglected when requesting emotional support, while emotional abuse was typified by resentment and being told they are inadequate. Physical abuse included partners shaking, slapping, or throwing objects at them. Both rural and urban women reported being harassed at their workplace by their partners’ repeated phone calls. In general, urban women faced more economic and other forms of abuse than rural women, especially emotional and physical abuse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Women’s economic abuse has developed into a pandemic, threatening the lives of women and girls globally (Tavares and Wodon, 2018). Violence against women is both a cause and consequence of gender inequality, in which men view women as their property and create gender-based dependency (United Nations [UN], 2006). Gender inequality is associated with patriarchal social structures, from which cultural practices of inequality between genders emanate. Such cultural practices commonly result in the undermining of women’s development and economic empowerment. Therefore, to achieve equality between genders, develop the human capital of women, and encourage their contribution to the economy, this structure should be eliminated (Fried, 2003; Tavares and Wodon, 2018; UN, 2006; Usta et al., 2013).

Economic abuse is defined as an intentional pattern of control in which individuals interfere with their partner’s ability to acquire, use, and maintain economic resources (Postmus et al., 2018), and forces one person to depend financially on the other (Adams et al., 2008; Sanders and Schnabel, 2006). This includes one person’s control and influence over money and property, their partner’s education, and work (Anitha, 2019), preventing their partner from accessing work, depriving them of control over their economic resources, and restraining their freedom to decide how to spend and earn their resources, as well as discrimination in pay and job promotions, which threatens their economic stability (Adams et al., 2008). Economic abuse can form part of family or intimate partner violence (IPV), and is a type of discrimination-based violence (Stylianou, 2018). In marital relationships, economic abuse is one form of invisible partner abuse (Postmus et al., 2018).

Adams et al. (2008) categorised the economic control of women by men into three basic types: (a) behaviours preventing women from acquiring resources, (b) behaviours preventing women from using the resources they already have, and (c) behaviours exploiting

women’s resources by directly stealing their money or depleting it by creating costs and debts. Fawole (2008) demonstrated that economic abuse against women and girls includes limiting their opportunities to access funds and credit, and partner dominance over women’s access to healthcare, employment, education, and agricultural resources. They also suffer discriminatory traditional rules related to inheritance, ownership rights, and the use of collective land. Economic abuse includes withholding funds for food and clothing, excluding women from financial decisions, and damaging their property. A woman’s partner may also refuse to let her contribute financially, prevent her from beginning or ending her education, or from obtaining informal or formal employment.

While some women may live comfortably with their children, they have no control over their household funds or expenditure decisions (Fawole, 2008). Furthermore, economic abuse against a woman applies when her partner prevents her from obtaining a job and places barriers to prevent her from maintaining her job, such as constantly making phone calls and surprise visits to her place of work or controlling her access to a phone or a car (National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, 2011). Unsurprisingly, blaming a woman for being unable to manage her funds is also a part of economic abuse (Egwuasi et al., 2018).

Economic abuse results in social inequality, marginalises the role of women, restricts their economic involvement, and leads to aggravated poverty, poor academic achievement, and limited development opportunities (Fawole, 2008; Krug et al., 2002). It exposes women to physical reproach and promotes sexual exploitation in women’s pursuit of breaking the cycle of poverty by any means. To eliminate the economic pressures of caring for dependent children and to overcome inadequate financial support from husbands, women often commercialise their bodies as a means of rapid enrichment, or resort to performing menial work and marrying at early ages (Fawole, 2008, p. 172). These precarious behaviours risk the contraction of AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases, the trafficking of girls and

women, and even death. Such abuse creates a burden of accrued debt on women from their abusers and creates a lack of access to independent income. Long-term consequences of emotional and psychological abuse include health deterioration, impairment of self-confidence and capacity to work, and an increase in employment tardiness and absenteeism. The movements and travel of abused women are restricted, their productivity and income are reduced, and their capacity to engage in social life is weakened. These consequences affect their children and lead to material deprivation and social exclusion, often exposing them to domestic violence as well. Abused women are typically denied the resources to adequately support their children, pursue education, and benefit from safe housing, adequate health insurance, and healthy food (Eriksson and Ulmestig, 2017; Fawole, 2008; Krug et al., 2002; Tavares and Wodon, 2018; Women’s Aid, 2019).

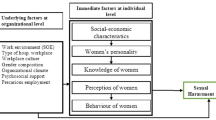

Ultimately, economic abuse may lead a woman to rely entirely on her partner to provide basic items, such as food and clothing. It could further force a woman to abandon her house or remain homeless after the relationship ends. Economic abuse may continue after the relationship has ended through the exercise of financial control over child support. It is noteworthy that economic barriers resulting from abuse may prevent women from leaving the relationship, and may force them to stay with abusive men for longer, thus exposing them to greater risk (Eriksson and Ulmestig, 2017; Fawole, 2008; Sharp, 2008; Women’s Aid, 2019). Married working women who experience economic abuse also experience other types of interconnected abuse, such as psychological, emotional, and physical abuse (Adams et al., 2008). Partners, in many instances, apply various abusive behaviours and tactics to reinforce economic abuse and maintain control over their wives. Partners generate constant dread in their wives to prevent challenges or retaliation, which exposes women to greater danger, according to the theory of marital dependency (Adams et al., 2008; Postmus et al., 2018; Sharp and Learmonth, 2017; Surviving Economic Abuse, 2020).

Understanding Jordan

Although Jordan has endorsed conventions associated with human rights and has ratified the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in 1992, organisational and societal barriers still result in gender-based discrimination in numerous socio-economic and political sectors (UN, 2008; EuroMed Rights, 2018; National Coalition led by the Arab Women Organization, 2013). Jordanian society is centred on unyielding typecast gender positions that focus on women’s reproductive responsibilities as a priority and fails to appreciate women’s functions and capabilities beyond the private domain. The prevalence of male-controlled and deep-rooted cultural stereotypes promote the outmoded responsibilities of women as mothers and wives. This discourages women from becoming independent or seeking out opportunities to be educated and further their professional careers, and thus results in women being less represented in political and economic fields, making them more exposed to abuse and exploitation (Information and Research Center-King Hussein Foundation [IRCKHF], 2019; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2018).

Despite the increase in attention to violence against women in Jordan, the number of women who become victims of domestic, physical, sexual, or psychological violence remains very high. The Jordan Population and Family Health Survey (2017–2018) confirmed that 25.9% of wives between the ages of 15–49 years have experienced physical, sexual, or emotional violence from their husbands (Department of Statistics, Jordan, 2018). The survey also showed the perpetrators of violence to be family members, with current husband coming in first at 71%, followed by ex-husband (15%), brother (13%), and father (1%) (Department of Statistics, Jordan, 2018). Moreover, the survey results showed that only one out of five married women seeks help when exposed to any form of violence from her husband (only 19% of married women between the ages of 15–49 years); in terms of violence type, 8% of married women seek help when exposed to sexual violence only, 17% seek help when exposed to physical violence only, and 30% of married women seek help when exposed to both physical and sexual violence. However, one limitation of this study is that 1.467 million women in Jordan older than 15 years, were not included in this survey; therefore, 47% of women have not had their voices heard, and their suffering is invisible with regard to domestic violence or violence outside the family (SIGI, 2019). Furthermore, Sisterhood is Global Institute Jordan SIGI (2019) showed that the total number of family murders of women and girls since the beginning of 2019 has reached 21, an increase of 200% compared to 2018.

Regarding the economic abuse of women, the 2019 report from SIGI illustrated that economic violence is practised by men against women in Jordan through many behaviours, most notably by domination, deprivation, coercion, and prevention. For example, a man might take control over family living expenditures or deprive a woman of her property and personal resources. Other examples include impoverishing women by depriving them of their inheritance, preventing them from working for a salary, tampering with their credit and loans, or using a woman’s finances against her interest. Partners will also prohibit women from free social and economic participation and control their spending. Some men refuse to contribute to living expenses or pay dues for outlays, thus generating more financial costs for women or forcing women to endure sexual exploitation to earn money. Furthermore, the report (SIGI, 2019) asserted that violence against working women is newly manifesting in the form of husbands seizing their wives’ salaries by extortion, fraud, deceit, and sometimes force. Some partners keep their wives’ ATM cards and withdraw their wives’ salaries as soon as it is transferred into their accounts. Additionally, they compel their wives to secure bank loans to buy property and cars in their partners’ names and deprive women of their inheritance and withhold support, whether for the woman or her children. The report concluded that women suffered much more than men as a result of repellent working environments, rise in unemployment rates, poor employment opportunities, unpaid jobs, and barriers to land ownership and real estate (SIGI, 2019).

Violence against women has its roots in inequality between women and men and is perpetuated by a culture of tolerance and denial (Parliamentary Assembly, 2014, p. 3). Sociological or sociocultural models can provide a macro-analysis of family violence by utilising the variables contained in social structures, such as inequality, patriarchy, cultural influences, and attitudes toward violence and family relations (Buriánek and Pikálková, 2013). The IRCKHF carried out a study in 2019 to delve into the predominance and root causes of gender prejudice and male dominance in Jordan. It determined several legal, social, and economic causes of gender inequality in Jordan. First, laws in Jordan endorse the existing male-controlled system. The electoral law centres on ‘one person, one vote’ but restricts women’s involvement in the Parliament. Gender functions are prescribed in the law primarily through the Personal Status Law, which makes the husband financially responsible; this means that women have to obtain permission from their husbands to work outside the conjugal home. Second, Jordanian educational curricula emphasise women as housewives and mothers, restricting their positions in the private sector. Third, the media produces content that doubts women’s capabilities and encourages gender stereotypes. Consequently, citizens are conditioned to believe that these prejudiced methods and beliefs are the standard, as they have become a part of daily life. Fourth, male dominance is further promoted by religious values, and the report specified that numerous religious figures frequently hold sermons based on their interpretations and personal beliefs, which are in contrast to accurate interpretations of religious texts (IRCKHF, 2019). This misinterpretation influences society by treating cultural and social standards as sacred religious teachings.

The literature on the economic abuse of women in Jordan is quite limited, with the focus on other types of violence (i.e., emotional, psychological, sexual). The Jordanian Hashemite Fund for Human Development and the Jordanian National Commission for Women announced their intention to prepare a study on economic violence against women in Jordan at the end of 2019; however, to our knowledge, the present study is one of the first studies to address patterns of economic abuse among working married women from rural and urban areas in Amman. In this context, this study explored the prevalence and patterns of economic abuse among working married women by comparing rural and urban women’s experiences and identifies other abuse associated with economic abuse (i.e. psychological, emotional, and physical abuse and harassment) experienced by both rural and urban women.

This study makes a novel contribution to the literature by exploring how Jordanian women experience economic abuse in rural and urban areas of Amman. This study will also contribute to building a comprehensive framework for the objective study of the economic abuses faced by women in Jordan.

It is important to note that this study discusses abuse instead of violence. Most of the previous literature, especially in Arab countries, uses the concept of violence interchangeably with the concept of abuse, given their similarities and consequences. However, they have independent connotations, with abuse considered as a more general term that includes ill- treatment and harsh words and actions. Abuse is malicious and includes unfair, corrupt, or unlawful practices or habits. It manifests in many forms, such as in physical or verbal abuse, causing injury, assault, violation, or rape, and involves committing unfair practices, crimes, or other types of aggression (McCluskey and Hooper, 2000; Merriam-Webster Dictionary, n.d.). Violence is the deliberate use of force for hurting, injuring, damaging, or destroying another person, group, or society (Krug et al., 2002; Merriam-Webster Dictionary, n.d.). The difference between abuse and violence is that while all forms of violence are considered

abuse, not every form of abuse is violent (Dubai Care Institution for Women and Children, 2015). Hence, this study adopted the term ‘economic abuse’ rather than ‘economic violence’, as the former is the most comprehensive of the various types of behaviours that women are exposed to economically.

This study was guided by four research questions:

-

1.

How often are women in rural and urban areas economically abused?

-

2.

How do women in rural and urban areas compare regarding the rate of economic abuse?

-

3.

Is there any relationship between economic abuse, psychological abuse, emotional abuse, physical abuse, and harassment faced by women in rural and urban areas?

-

4.

What are the similarities and differences between economic abuse and other types of abuse faced by women?

Methods

Research method

This study was conducted using a quantitative research approach, utilising a descriptive comparative research design. Descriptive research was an appropriate method to accomplish the objectives and questions of the present study, which were to accurately and systematically describe a phenomenon, and answer what, where, when and how questions. Moreover, it is useful as little is known about economic abuse in Jordan. This study utilised a combination of two data sets; urban and rural areas of the capital of Jordan, Amman. Descriptive statistics summarised and organised the characteristics of each of data set, and facilitated accurate comparisons of the two data sets, which were gathered from randomly selected respondents using a self-administered questionnaire (McCombes, 2019; Bhandari, 2021).

Participants and data collection

A random sample of 500 working married women, 20 years and older, was identified from rural and urban areas in Amman. Women in the 25–34, and 45–54 years age groups contained more women originating from rural areas (51.5%), whereas the 55 years and older age group contained more women from urban areas (52.9%). Women from the 35–44 years age group constituted 49.8% of women from urban areas. Rural (46.4%) and urban (53.6%) women had completed bachelor’s degrees, and 54% of rural women reported a monthly family income between 751–1000 JD, whereas 92% of urban women reported a 1001–1250 JD income per month. Rural women who had been married longer than 15 years constituted 59% of participants, and 75% reported that their husbands had partially completed high school, with 49.7% reported that they have 4 or more children. Length of marriage for 60.6% of urban women ranged from 121 months–15 years, and 61.7% reported that their husbands had completed a bachelor’s degree, and 42.2% reported that their husbands were employed full-time. Overall, 51.6% of the participating urban women had 2–3 children (see Table 1).

Referencing data from the Jordanian Department of Statistics (2019), the sample was selected in four stages: (1) four out of Amman’s total nine districts were randomly chosen (two from rural areas and two from urban areas); (2) five villages from each of the four districts were chosen for a total of 20 villages; (3) five blocks from each village were selected (5 × 50 = 100 blocks); (4) five families were selected from each block through systematic random sampling. Prior to conducting the interviews and distributing the questionnaire, the participants were given information concerning the objectives of the study and its benefits by the researcher or research team. Each participant was informed that their participation was voluntary and that there would be no consequences if they chose to withdraw from the study. The study was approved by the Scientific Research Committee in the Department of Sociology from the University of Jordan.

Measures

To reveal how Jordanian women are exposed to economic abuse, the Scale of Economic Abuse (SEA) developed by Adams et al. (2008) was used. It consists of 28 items divided into two categories: Economic Control (17 items) and Economic Exploitation (11 items). Two additional measures were used in this study to expose the effects of economic abuse by providing evidence of a relationship between economic abuse of women and other abuses that women experience: the Profile of Psychological Abuse of Women (PPAW), a widely used 21-item scale that measures an extensive range of psychological abuse (Sackett and Saunders, 1999), and the Community Composite Abuse Scale (CCAS), a 28-item scale that measures physical abuse (10 items), emotional abuse (14 items), and harassment (4 items; Loxton et al., 2013). Participants rated each item using a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 [never] to 4 [always]); the values of the arithmetic means will be treated as follows with regards to the quintuple gradation: 2.67 and above is high, 1.34–2.66 is medium, and 1.33 and below is low.

This scale’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.80, thereby indicating high reliability. A scale is considered reliable if the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is >0.60 (Sekaran and Bougie, 2016). The skewness coefficients for all the study’s variables were <1, which shows the study data were normally distributed (Hair et al., 2013).

Data analysis

SPSS Statistics 22.0 was used to perform the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics including frequency distribution and percentage were calculated from respondents’ demographic characteristics. Kendall’s tau-b correlation coefficient was also used to measure the strength and direction of the association between the scales. Finally, an independent-samples t-test was used to determine whether significant differences existed between the abuse and respondents’ demographic characteristics across the different areas.

Results

This study first uncovered the types of economic abuse faced by rural and urban women, and then compared the relationship between economic and interconnected abuse (psychological, emotional, and physical abuse, and harassment) for rural and urban women.

In terms of the first two research questions of the present study, results showed that 55.2% of urban women and 44.8% of rural women have been economically abused (see Tables 2 and 3). Women who experienced economic control included 44.5% of rural and 55.5% of urban women. The most common control strategies used by urban women’s partners included threats to force women to quit their jobs (59.8%), interrogating them about spending habits (57.8 %), creating scenarios that require women to ask for money (55.6%), and excluding women from participating in critical financial decisions (54.1%). Additionally, urban women were economically exploited by their partners, who spent their money (60.3%), delayed settling invoices or paying for financial obligations (54.4 %), and asked the women to acquire loans but refused to repay them (54.6 %).

In the case of rural women, their partners prevented them from participating in important financial decisions (45.9%), demanded to know how they spend their money (47.3%), made decisions about how they did so (42.2%), and concealed important financial information (44.2%). Furthermore, rural women were economically exploited by their partners, who asked them to take on loans but refused to repay them (46.7%), refused to work, and persuaded the women to provide money (44.9%).

The results of the analysis of the Kendall’s tau-b correlation coefficient for ordinal samples answered the third and fourth research questions, indicating a high, significant, and direct relationship (r = −172, p ≤ 0.05) between economic abuse and psychological, emotional, and physical abuse and harassment. Tables 3, 4, and 5 show that urban and rural women who faced economic abuse also reported suffering other forms of abuse. All were subject to psychological, emotional, and physical abuse as well as harassment. The results also indicate that urban and rural women suffered primarily from emotional and physical abuse, followed by psychological abuse and harassment.

Table 4 illustrates that 55.5% of urban and 44.5% of rural women faced psychological abuse, which included their partners expressing frustration when the women cried or asked for emotional support, being rebuked by their partners when they met other people, or being asked by their partners for everything to be done in a specific manner. Of all participants, 57.3% of urban women and 42.7% of rural women faced emotional abuse, which included dealing with partners who were resentful when the housework was not completed, who told them that they were not good enough, and prevented them from socialising with their female friends. An overall 35% of all women—56.4% of urban women and 43.6% of rural women— reported that they faced physical abuse, where their partners shook, slapped, or threw objects at them; 50.5% of urban women and 49.5% of rural women reported that they were harassed at their workplace by their partners’ repeated phone calls. In general, urban women faced more economic and other forms of abuse than did rural women, especially emotional and physical abuse.

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare rural and urban women’s education and income. In Table 6, results showed urban women earned more and had received higher education compared to their rural-area counterparts, which indicates that location affected women’s income and educational level. We also checked for the husband’s employment status across both areas. Result showed no significant differences in husbands’ employment status between rural and urban areas (t (498) = 1.913, p = 0.056), suggesting that location did not affect husbands’ employment status.

Regarding the association between the different abuse types rural and urban women face, the null hypothesis states that ‘there is no statistically significant relationship between the different abuses and area’, which will be tested at 0.05 level of significance. Therefore, an independent t-test was run with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for mean difference. It showed that on average, urban women were more exposed to economic abuse (M = 2.7640, SD = 1.1029) than rural women (M = 2.2467, SD = 1.0069). The difference 0.5173 (95% CI [0.3317, 0.7029]) was statistically significant (t(493.924) = 5.477, p < 0.05), demonstrating that the rate of economic abuse in urban areas is higher than that in rural areas.

Further, as shown in Table 7, no significant difference was found in the level of harassment between urban and rural women (t(498) = 0.399, p = 0.69), with a difference of 0.1026 (95% CI [−0.1607, 0.2427]). Women from urban areas scored higher in economic control, economic exploitation, psychological abuse, physical abuse, and emotional abuse compared to their rural counterparts.

Discussion

Women in Jordanian urban and rural areas are still subject to domination by patriarchal powers. The results of the current study demonstrated that 44.5% of rural women and 55.5% of urban women were economically abused through economic control. The context in which violence and abuse occur in intimate partnerships is frequently referred to as one of ‘coercive control’ (Postmus et al., 2018), which contributed to the prediction of economic difficulties encountered by women in intimate partnerships (Adams et al., 2008; Fawole, 2008).

In light of legal protections and the government’s intervention in favour of women, some men attempt to aggressively violate women’s rights by using indirect patriarchal power (Baburajan, 2020; Htun and Jensenius, 2020; Sultana, 2012; Johnsson-Latham, 2005). Therefore, economic control has emerged as the most common form of economic abuse against married women. Because it is undetectable by others, it may be more challenging to address or prevent, as it is related to the nature of the marital relationship and connected to the traditional characteristics of a stable marriage (Conner, 2014; Hardie and Lucas, 2010; Postmus et al., 2018). Women in Arab and Muslim countries are subjected to their husband’s economic control as they apply the rules of Islam, which stipulate ‘male guardianship’ or ‘men as sustainers’, which implies protecting and caring for women. The husband has the last word after consulting his household. This right has been incorrectly interpreted and used as an excuse for oppression and tyranny, and some men use it arbitrarily and secure free benefits through abuse. Women also fear divorce because it carries a stigma in Arab culture and may lead to social exclusion; for stability, reputational risks, and to look after children, women remain silent and endure abusive marriages (David, 2018; Mendoza et al., 2020; Savaya and Cohen, 2003).

The prevailing view among the public is that rural women are more abused than urban women due to low levels of education and stricter adherence to traditions (Ajah et al., 2014; Bueno and Lopes, 2018; UN Commission on the Status of Women, 2018). However, the current study’s results indicate that the economic abuse of urban women is slightly higher than that of rural women, which may be because women in urban areas earn more and have a higher educational level than women in rural areas. Higher education yields valuable benefits to women and encourages creative problem solving and the development of communication and leadership skills, and elevated self-confidence. Moreover, advanced education increases awareness among women with respect to their rights and how to defend them and equips women with the ability to better distinguish abuse. Education provides women with greater employment opportunities, increased wages, and greater involvement in negotiating for their improved quality their life and social status. However, this may lead men to perceive women as competitors, and ultimately expose them to a greater risk of abuse (Witcher, 2009). This result is consistent with the findings of Ivey (2019) on financial abuse in urban communities in the United States and confirmed that IPV is a serious public health problem. Ivey (2019) also indicated that there is limited research on women victims of IPV within urban communities. Moreover, female victims of IPV within urban communities tend to have more resources than their rural counterparts (Ivey, 2019). Urban community resources (social support, psychological support, and financial support) have a viable impact on a woman’s ability to deal with IPV. However, Bueno and Lopes (2018) indicated that violence rates are increasing in cities with the worst social and economic indicators. Overall, the findings of the present study diverge from those of Edwards (2015), who found that the rates of IPV are generally similar across rural, urban, and suburban locales. Bhandari et al. (2015) explained that the escalation in abuse of women living in urban areas could be because of a reduction in their competitiveness for resources such as public housing, which had made it easier for women living in rural areas to leave their abusive partners. As a result of long waiting lists for resources, this is not possible for most urban women, leading to a dependency on abusive partners and exposure to violence.

In the Jordanian context, the higher rate of economic abuse for urban women can be justified by demographic statistics on women’s status (2018–2019). The first justification lies in the larger urban population (97%). The report also indicates that women in Jordanian rural areas complain of marginalisation and discrimination because of general economic conditions, most notably, widespread poverty and lack of employment; this means that men and women in rural areas face the same conditions. These negative economic conditions may increase women’s economic burden and their susceptibility to economic and emotional abuse and harassment by their partners. Under these stressful conditions, partners may resort to exploiting women’s economic resources (Fawole, 2008; Postmus et al., 2018).

In this regard, the SIGI report indicated that in 2018, 40.8% of urban female workers had the freedom to decide how to spend their income, compared to 30% of rural female workers. In terms of place of residence, the central region of the country, which comprises urban areas, recorded the highest percentage of expenditure freedom at 45.6%, followed by the northern region at 30.3% and the southern region at 25.8% (SIGI, 2019). Additionally, the Jordanian general statistics report for 2018 (Department of Statistics, Jordan, 2018) demonstrated that 12.3% of women in rural areas decide how to use their financial income, compared to 14.9% of women in urban areas. Abramsky et al. (2019) concluded that women who financially contributed more than their partners had a greater IPV risk—consistent with the present results. The more control an urban woman has over her economic resources, the more she is subject to economic abuse by her husband through economic control (SIGI, 2019).

The results of the current study revealed that urban and rural women who faced economic abuse reported that they suffered primarily from emotional and physical abuse, followed by psychological abuse and harassment. Furthermore, urban women faced more types of abuse than rural women. Higher percentages of emotional and physical abuse than economic abuse experienced by urban women, suggests that perpetrators use emotional and physical abuse as severe tactics to achieve economic control, and to exploit women’s financial resources (Adams et al., 2008). Emotional abuse is a way of achieving coercive control in intimate relationships (Stark, 2007), and includes patterns of manipulation, control, and intimidation (Zavala and Guadalupe-Diaz, 2018). Emotional abuse is often a precursor to physical abuse in intimate relationships (Hannem et al., 2015). These results confirm the findings of Leburu-Masigo (2019), whose study revealed that urban and rural women are subjected to more than one form of IPV from their partners, such as emotional violence, physical violence with high levels of economic and emotional abuse, and very high levels of controlling behaviour.

However, the opposite has also been found. Peek-Asa et al. (2011), found that rural women live much farther away from available resources and experience higher rates of IPV and greater frequency and severity of physical abuse than their urban counterparts. Stylianou (2018) indicated that the early literature on economic abuse suggests that it remains a unique construct separate from other forms of abuse or a subset of psychological abuse experiences. However, a great deal of research has confirmed that economic abuse is intertwined with other forms of abuse that women experience, and when women had experienced psychological, physical, or sexual forms of abuse and harassment, this was a result of or reason to promote economic abuse (Adams et al., 2008; Eriksson and Ulmestig, 2017; Fawole, 2008; Moe and Bell, 2004; Sanders, 2015; Stylianou et al. 2013; Swanberg and Macke, 2006).

Notably, certain cultural and social norms that encourage and support violence exist in some societies, which perpetuate the problem of abuse of women (WHO, 2009). For example, D’Silva et al. (2018) argued that women’s financial dependency on their husbands and requirements of certain sociocultural structures cause and perpetuate household violence. In the same context, Dhungel et al. (2017) clarified that because of the male dominance within social systems that unfairly discriminate against women, IPV against women is encouraged, further connecting this to the cultural factors that limit women’s choices for leaving a violent marriage. Zembe et al. (2015) identified the relationship power inequity between men and women in intimate relationships as the factor that allows IPV, and that cultural and patriarchal social belief systems uphold this inequality. This provides a social environment that is conducive to the performance of patriarchal models of masculinity that valorise violence and reinforce this power differential, particularly regarding female independence and economic empowerment.

In Jordan, a study by the IRCKHF (2019) confirmed that economic dependence and control is further enhanced by legal, social, cultural, and religious value systems that make men responsible for finances and women dependent. Because of this structure, women are placed in a disadvantaged position as men maintain and control most of the wealth and resources. Notwithstanding Islamic law that stipulates men must be financially responsible, and that women have full responsibility for what they earn, due to social traditions many women are pressured or forced into surrendering their resources. This includes denying women the right of inheritance due to legal loopholes.

Economic abuse as part of a broader spectrum of family or domestic violence has devastating effects on the lives of women as it infringes on their fundamental human rights to physical integrity and freedom from fear (Adams et al, 2008; Postmus et al., 2018). It further jeopardises basic human capabilities as women are continuously subjected to inequality, which restricts and undermines their ability to participate as worthy, recognised citizens in economic, political, and social spheres. This affects women and has a ripple effect on their children, families, and wider society, constituting a major barrier to achieving equitable and sustainable human development (Kabeer, 2014). Our results indicate that economic abuse through control of women’s economic resources and managing their financial decisions as well as exploiting their economic resources perpetuates gender inequality and undermines their right to be treated as human beings, meaning the right to life, safety, dignity, and physical and moral integrity. Therefore, the social values and beliefs that permit exploitative behaviour must change to reduce the economic abuse of women.

One of the study’s strengths is that it was conducted with an appropriate and diverse sample of women of varied demographic backgrounds. It is one of the first studies to address the patterns of economic abuse and identifies other types of abuse within an Arabic social- cultural context. This study enriches the field of women’s studies in Jordan, and provides a detailed understanding of the problem of abuse of Jordanian women, considering the high rates of violence and abuse during 2019–2021. Nevertheless, the present study also had some limitations. First by including women from the northern and southern regions of Jordan, the study sample could have enhanced the results and presented clearer details on the women’s abuse experiences, and patterns of economic abuse. However, the researcher’s limited financial resources prevented this. Second, the inclusion of additional variables, such as kinship between spouses, religion, women’s employment status (in the private or governmental sectors, full or part time), could be valuable in terms of a more granular understanding of women’s abuse within marital relationships. While the scale used in the present study was a good fit for the study context and achieving its objectives, employing a measure to explore the consequences of economic abuse, and to determine if economic abuse is as a result of or the reason for psychological, emotional, physical, or sexual abuse, could further clarify the relationship between economic abuse and other types of women abuse.

This is an important matter that merits further research.

Conclusion

Abuse of women is undoubtedly a major contravention against human society. It is an unjust infringement of women’s basic rights as well as a serious form of gender-based discrimination. All spheres of a woman’s life and freedom of choice may be undermined, constricted, negatively influenced, and dominated by age-old cultures, traditions, and religions that support and encourage the patriarchy. This is, unfortunately, an active ingredient of economic abuse and violence against women, which presents a serious obstacle to achieving gender equality. Particularly, when economic abuse is intertwined with emotional, psychological, and physical abuse and harassment, it reinforces economic abuse. The results of the current study should be used to inform practices and policies that work to stop those who support and practise abusive behaviour, discrimination, and violence against women. It is apparent from these results that women with different lifestyles face economic abuse because, regardless of the degree of urbanisation, the abuse stems from cultural contexts that restrict women’s social status and roles, despite the steps that have been taken to empower women.

Data availability

All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

Abramsky T, Lees S, Stöckl H et al. (2019) Women’s income and risk of intimate partner violence: secondary findings from the MAISHA cluster randomised trial in North-Western Tanzania. BMC Public Health 19(1):1108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7454-1

Adams AE, Sullivan CM, Bybee D et al. (2008) Development of the scale of economic abuse. Violence Against Women 14(5):563–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801208315529

Ajah LO, Iyoke CA, Nkwo PO et al. (2014) Comparison of domestic violence against women in urban versus rural areas of southeast Nigeria. Int J Women’s Health 6:865–872. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S70706

Anitha S (2019) Understanding economic abuse through an intersectional lens: financial abuse, control, and exploitation of women’s productive and reproductive labor. Violence Against Women 25(15):1854–1877. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218824050

Baburajan PK (2020) Gendered spaces in the Arab world. J Asian Res 4(3):19–28. https://doi.org/10.22158/jar.v4n3p19

Bhandari, P (2021) An introduction to quantitative research. https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/quantitative-research/

Bhandari S, Bullock LF, Richardson JW et al. (2015) Comparison of abuse experiences of rural and urban African American women during perinatal period. J Interpers Violence 30(12):2087–2108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514552274

Bueno AM, Lopes M (2018) Rural women and violence: readings of a reality that approaches fiction. Ambient Soc 21:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4422asoc170151r1vu18l1ao

Buriánek B, Pikálková S (2013) Intimate violence: a Czech contribution on international violence against women survey. Karolinum Press, Prague

Conner DH (2014) Financial freedom: women, money, and domestic abuse. William Mary J Race Gend Soc Justice 20(2):339–397

David H (2018) Women’s divorce rights in Jordan: legal rights and cultural challenges. Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection 2969. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2969

Department of Statistics, Jordan [DOS] (2018) Jordan population and family and health survey 2017–18: key indicators. DOS and ICF: Amman, Jordan, and Rockville, MD, USA. http://www.dos.gov.jo/dos_home_a/main/linked-html/DHS2017_en.pdf

Department of Statistics, Jordan (2019) Report: Estimated population 2019 and some selected data. http://dosweb.dos.gov.jo/DataBank/Population_Estimares/PopulationEstimates.pdf

Dhungel S, Dhungel P, Dhital SR et al. (2017) Is economic dependence on the husband a risk factor for intimate partner violence against female factory workers in Nepal? BMC Women’s Health 17(1):82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0441-8

D’Silva S, Frey S, Kumar S et al. (2018) Sociocultural and structural perpetuators of domestic violence in pregnancy: a qualitative look at what South Indian women believe needs to change. Health Care Women Int 39(2):243–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2017.1375505

Dubai Care Institution for Women and Children (2015) Violence and mistreatment of children: field study on a sample of national children in the Emirates community. UAE

Edwards KM (2015) Intimate partner violence and the rural–urban–suburban divide: myth or reality? A critical review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abus 16(3):359–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014557289

Egwuasi PI, Laguador JM, Oleforo NA et al. (2018) School environment in Africa and Asia Pacific, 3rd edn. Author House, Bloomington

Eriksson M, Ulmestig R (2017) It’s not all about money: toward a more comprehensive understanding of financial abuse in the context of VAW. J Interpers Violence https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517743547

EuroMed Rights (2018) Jordan: situation report on violence against women. https://euromedrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Factsheet-VAW-Jordan-EN.pdf

Fawole OI (2008) Economic violence to women and girls: Is it receiving the necessary attention? Trauma Violence Abus 9(3):167–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838008319255

Fried ST (2003) Violence against women. Health Hum Rights J 6(2):88–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/4065431

Hair F, Black W, Anderson R (2013). Multivariate data analysis: person new international edition. Person Education Limited

Hannem S, Langan D, Stewart C (2015) “Every couple has their fights …”: stigma and subjective narratives of verbal violence. Deviant Behav 36(5):388–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2014.935688

Hardie JH, Lucas A (2010) Economic factors and relationship quality among young couples: comparing cohabitation and marriage. J Marriage Fam 72(5):1141–1154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00755.x

Htun M, Jensenius FR (2020) Fighting violence against women: laws, norms, & challenges ahead. Daedalus 149(1):144–159. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_01779

Information and Research Center-King Hussein Foundation [IRCKHF] (2019) Gender discrimination in Jordan. IRCKHF

Ivey CAS (2019) Intimate partner violence in urban communities. In: The encyclopedia of women and crime. John Wiley & Sons

Johnsson-Latham G (2005) Patriarchal violence—an attack on human security. Report from Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, Government of Sweden. https://www.government.se/49b730/contentassets/87a9c5e22af14395aff3411dbd197f58/patriarchal-violence---an-attack-on-human-security

Kabeer N (2014) Violence against women as “relational” vulnerability: engendering the sustainable human development agenda. UNDP Human Development Report Office, New York

Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA et al. (2002) World report on violence and health. World Health Organization, Geneva

Leburu-Masigo GE (2019) Urban and rural women’s experiences of intimate partner violence. South Afr J Soc Work Soc Dev 31(3). https://doi.org/10.25159/2415-5829/4175

Loxton D, Powers J, Fitzgerald D et al. (2013) The community composite abuse scale: reliability and validity of a measure of intimate partner violence in a community survey from the ALSWH. J Women’s Health Issues Care 2(4). https://doi.org/10.4172/2325-9795.1000115

McCombes, S (2019) Descriptive research. https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/descriptive-research/

McCluskey U, Hooper C-A (2000) Psychodynamic perspectives on abuse: the cost of fear. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London

Mendoza JE, Tolba M, Saleh Y (2020) Strengthening marriages in Egypt: impact of divorce on women. Behav Sci 10(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10010014

Merriam-Webster Dictionary (n.d.) Violence. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/violence. Accessed 25 Oct 2019

Moe AM, Bell MP (2004) Abject economics: the effects of battering and violence on women’s work and employability. Violence Against Women 10:29–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801203256016

National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (2011) Economic abuse, national coalition against domestic violence. http://www.ncadv.org/files/EconomicAbuse.pdf. Accessed 21 Oct 2019

National Coalition led by the Arab Women Organization (2013) Women’s Rights in Jordan. file:///C:/Users/USER/Downloads/JS1_UPR17_JOR_E_Main.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. (2018) Women’s political participation in Jordan: barriers, opportunities and gender sensitivity of select political institutions. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/mena/governance/womens-political-participation-in-jordan.pdf

Parliamentary Assembly (2014) Focusing on the perpetrators to prevent violence against women. http://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/Xref-XML2HTML-en.asp?fileid=21325&lang=en. Accessed 21 Oct 2019

Peek-Asa C, Wallis A, Harland K et al. (2011) Rural disparity in domestic violence prevalence and access to resources. J Women’s Health 20(11):1743–1749. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2011.2891

Postmus JL, Hoge GL, Breckenridge J et al. (2018) Economic abuse as an invisible form of domestic violence: a multicounty review. Trauma Violence Abus 21(2):261–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018764160

Sackett L, Saunders D (1999) Profile of psychological abuse of women. Measurement Instrument Database for the Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.13072/midss.239

Sanders CK (2015) Economic abuse in the lives of women abused by an intimate partner: a qualitative study. Violence Against Women 21(1):3–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801214564167

Sanders CK, Schnabel M (2006) Organising for economic empowerment of battered women: women’s savings accounts. J Community Pract 14(3):47–68. https://doi.org/10.1300/J125v14n03_04

Savaya R, Cohen O (2003) Perceptions of the societal image of Muslim Arab divorced men and women in Israel. J Soc Pers Relatsh 20(2):193–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075030202004

Sekaran U, Bougie R (2016). Research methods for business: a skill building approach, 7th edn. Wiley

Sharp N (2008) What’s yours is mine: the different forms of economic abuse and its impact on women and children experiencing domestic violence. Refuge. https://dev.refuge.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Whats-yours-is-mine-Full-Report.pdf

Sharp N, Learmonth S (2017) Into plain sight: how economic abuse is reflected in successful prosecutions of controlling or coercive behaviour. Surviv Econ Abuse. https://survivingeconomicabuse.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/P743-SEA-In-Plain-Sight-report_V3.pdf

Sisterhood is Global Institute-Jordan (2019). Economic violence against women (Position paper). https://secureservercdn.net/198.71.233.44/9hy.a00.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%82%D8%A9-%D9%85%D9%88%D9%82%D9%81-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D9%86%D9%81-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%82%D8%AA%D8%B5%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%8A-%D8%B6%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%B3%D8%A7%D8%A1.pdf.

Stark E (2007). Control: the entrapment of women in personal life. Oxford University Press

Stylianou AM (2018) Economic abuse within intimate partner violence: a review of the literature. Violence Vict 33(1):3–22. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-16-00112

Stylianou AM, Postmus JL, McMahon S (2013) Measuring abusive behaviours: Is economic abuse a unique form of abuse? J Interpers Violence 28(16):3186–3204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513496904

Sultana A (2012) Patriarchy and women’s subordination: a theoretical analysis. Arts Fac J 4:1–18. https://doi.org/10.3329/afj.v4i0.12929

Surviving Economic Abuse (2020) Statistics on financial and economic abuse: economic abuse limits women’s choices and ability to access safety. https://survivingeconomicabuse.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Consultation-Document-Economic-Abuse-Evidence-Form-v1-1.pdf

Swanberg JE, Macke C (2006) Intimate partner violence and the workplace: consequences and disclosure. Affilia 21(4):391–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109906292133

Tavares P, Wodon G (2018) Ending violence against women and girls: Global and regional trends in women’s legal protection against domestic violence and sexual harassment. World Bank, New York

United Nations [UN] (2006) In-depth study on all forms of violence against women: Report of the Secretary-General A/61/122/Add. UN. https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/vaw/SGstudyvaw.htm

United Nations (2008) Violence against women: Assessing the situation in Jordan. UN. https://www.un.org/womenwatch/ianwge/taskforces/vaw/VAW_Jordan_baseline_assessment_final.pdf

United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (CSW62) (2018) Individual deprivation measure: knowing who is poor, in what way and to what extent. United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (CSW62)

Usta J, Makarem N, Habib R (2013) Economic abuse in Lebanon: Experiences and perceptions. Violence Against Women 19(3):356–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801213486313

Witcher J (2009). Educate the women and you change the world: investing in the education of women is the best investment in a country’s growth and development. Commission on the Status of Women, Fiftieth Session, 4th & 5th Meetings. ―Absence of Women for Leadership Positions Undermines Democracy, Economic and Social Council, WOM/1541, 28/02/2006

Women’s Aid (2019) The domestic abuse report 2019: The economics of abuse. Women’s Aid: Bristol. https://www.womensaid.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Economics-of-Abuse-Report-2019.pdf

World Health Organization (2009) Changing cultural and social norms that support violence. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44147

Zavala E, Guadalupe-Diaz XL (2018) Assessing emotional abuse victimization and perpetration: a multi-theoretical examination. Deviant Behav 39(11):1515–1532. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2018.1491700

Zembe YZ, Townsend L, Thorson A, Silberschmidt M, Ekstrom AM (2015) Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity and the role of sexual and social risk factors in the production of violence among young women who have multiple sexual partners in a peri-urban setting in South Africa. PLoS ONE 10(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139430

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Doukhi Hunaity at the University of Jordan, Mr. Fasanya Agbaje Oluwafunmibi for the review and audit of the statistical analysis, and Mr. Develin Greeff for his encouragement and support. We also thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing. This study is supported by The Phenix Center for Economics & Informatics Studies, a non-governmental organization in Amman, Jordan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alsawalqa, R.O. Women’s abuse experiences in Jordan: A comparative study using rural and urban classifications. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8, 186 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00853-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00853-3

This article is cited by

-

Tattoos and career discrimination in a conservative culture: the case of Jordan

Current Psychology (2024)