Abstract

Discourse gives social and physical realities meaning. Individuals, cultures, and states all use discourse to understand who they are, how they live, and how the world works. A similar discourse gained traction in the post-9/11 world. The discourse disseminated through the American media constructed a form of binarism in the guise of the Us vs. Them. This discourse was extended to account for representations of friend or foe. Discourses as mentioned earlier, give meaning to the reality around us. As part of international relations and politics, these discourses are the optimum site for establishing and enacting power and status. To analyze such a negotiation of positions and power in discourse, this research analyzes the American media’s coverage of the former head of the Pakistani state, i.e., (General) President Pervez Musharraf. The corpus comprising 509 articles has been used as the research data. Using the notions of semantic preference and prosody, the study reveals that Musharraf’s identity is fostered more on political lines rather than military, signifying the downplaying of his dictatorship. On the other side, his efforts in the War on Terror are looked upon as dubious and the media coverage is mixed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Discourse gives social and physical realities meaning. Individuals, cultures, and states all use discourse to understand who they are, how they live, and how the world works. A discourse is a coherent collection of ideas, concepts, and categories about a certain item that frames it in a particular way and, as a result, limits the range of possible responses to it. The role of discourse especially in the domain of media is considered pivotal in shaping public opinion both implicitly and explicitly. The power of media has an impact on which social construct is being built (Jørgensen and Phillips, 2002). This paper examines in particular, discursive manipulation surrounding the image of Pakistani president General Musharraf by the American media. The discourse disseminated through the American media constructed a form of binarism to account for representations of friend or foe, representing countries through their choice of either supporting or opposing the US in its war against terror. This research views this discursive manipulation as part of the underlying ideology of American foreign policy. This underlying ideology also demanded cooperation with Pakistan in the post-9/11 world in order to manifest strategic goals. In other words, and this is crucial, the Pak–US social ties served as both the center of power for the parties involved and the place where meaning was created based on certain agendas.

Many journalists from across the US media agencies were deployed in Pakistan and Afghanistan in 2001 as foreign correspondents to capture the essence of war. This set into motion the global effect, where no news remained local but became international thereby transcending traditional borders just within a few hours (Frizis, 2013). Media discourse was also used as a tool for mobilizing the national ideology underlying the US foreign policy post-9/11 (Kellner, 2004). For this particular reason, the US media not only covered the war in Afghanistan but conferred a huge status upon Pakistan. However, the image of Pakistan was not based on a simple dichotomy of us vs. them. As this research uncovers, the country’s media portrayal reveals the blurring of in-group and outgroup boundaries. This case was unique to Pakistan and its representation in the US media. Pakistan was placed beyond the binary categorization of friend vs. foe and was framed in such a way as to align with US foreign policy goals.

As this paper will expound in the coming sections, Pakistan’s representative during the time—General Pervaiz Musharraf—was also portrayed differently from other military dictators.Footnote 1 With respect to the foreign countries’ coverage in media, a major focus is on foreign political leaders as compared to other aspects. This has been observed despite the fact that multiple variables like geographical distance, political and economic interests, and values tend to affect this trend (Balmas and Sheafer, 2013). As politics remains one of the major aspects with regard to media’s status conferral, in order to analyze the anomalous position of Pakistan in us vs. them dynamics, the present paper scrutinizes the image of the country in the political sphere. Since politics is a complex and broad term, keeping in view the feasibility of the project, this research narrows its focus down to political actors. This approach is supported by literature that regards the personalization of politics as a phenomenon where leaders take the centre stage in the political arena (McAllister, 2007). This trend was also observed in the post-9/11 media coverage, where Pakistani (General) President Pervez Musharraf was the major political actor in the political arena, both domestically and internationally. However, most existing studies are geared towards social actors in terms of group identity and not much research is conducted from the perspective of an individual actor. The present paper fills this gap by examining the unique position of General Pervaiz Musharraf and Pakistan in the American media by situating them against the ‘friend or foe’ and ‘us vs. them’ polarity.

Synergy of Corpus Linguistics and critical discourse analysis

In order to generate an exhaustive analysis, this research builds on a synergy of corpus linguistics and critical discourse analysis. In recent years, the synergy of Corpus Linguistics and various types of Discourse Analysis has been an intriguing research area for linguists, though the efforts for such an amalgamated approach can be traced back to the 1990s (Baker et al., 2008; see also Krishnamurthy, 1996; Stubbs, 1994). Many studies utilize the techniques of Corpus Linguistics in tandem with those of Discourse Analysis to unveil the discourse patterns which are generally not explicit (Haider, 2019). This considerably eases the way for mixed method research which can seamlessly switch between statistical and close text analysis (Partington, 2014, see also White, 2017; Samaie and Mahmir, 2017). This synergy is often termed corpus-assisted discourse analysis (Haider, 2017) or corpus-assisted discourse studies (CADS) (Partington et al., 2013). It is at times differentiated from corpus linguistic critical discourse analysis (CLCDA). As the former is more dynamic, it entails that CLCDA falls under the domain of CADS (Haider, 2017; see also Partington et al., 2013). It is much more dynamic than traditional CDA. The benefits of using this integrated approach include (i) the ability to uncover the salient, as well as less prominent discourses underlying any data (Partington et al., 2013) and (ii) the ability to provide a wide range of analytical tools and methods for scrutinizing data (Jaworska, 2016). This generates a much more exhaustive analysis.

The need for such interfacing has surfaced due to much criticism levelled against researchers in the field of critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics, where the former are denounced for using small a number of texts, lack of transparency in presenting research methodology (Rogers et al., 2005) and taking an explicit position on the issues under study (Breeze, 2011). CDA is also accused of cherry-picking (Widdowson, 1996, 1998).

On the other hand, two charges are levelled against Corpus Linguists by critical discourse analysts (Partington, 2014). The primary criticism is related to the issues of context, which Corpus Linguists ignore completely. Context can be defined as mere co-text as well as “social, political, historical and cultural context of the data” (Baker et al., 2008, p. 293) under consideration. Baker et al. (2008) and Brown and Yule (1982) provide a rebut to this by illustrating how the expansion of concordance lines aids in understanding the context in terms of co-text. Still, the larger context, which CDA considers, is not taken into account by traditional Corpus Linguists. The second criticism is based upon the evaluation of absences in the data where a charge is levelled against Corpus linguistics researchers that they cannot embark on the absences of certain elements in the data.

As pointed out earlier, the present paper is based upon both the quantitative aspect of Corpus Linguistics and the critical qualitative aspect of CDA. In order to analyze the media coverage of Musharraf via the synergy of CL and CDA, Sinclair’s notion of a ‘lexical item’ is used. Sinclair divides this further into five basic units. The first and foremost element is the ‘core’; it refers to the term being searched in the corpus. It is also termed a node. The next unit i.e., ‘collocation’, covers different aspects and methods of identification. The idea of collocation originally proposed by Firth was modified by Halliday in 1961 to account for the notion of proximity and probability, i.e. the distance between two items. The notion of probability referred to the use of statistical tools for the purpose of validating the collocates. Sinclair (1998) took collocation studies on another path by setting the collocational boundaries or restraining the context (setting threshold level on window span). It is also understood in terms of operationalizing the concept of collocation (Bartsch and Evert, 2014). So, the notion of collocation used in the current research is the co-occurrence of words within a restricted context in a corpus (window span L5:R5). Various techniques are used to identify collocations such as statistical tests to check the strength of collocations (Herbst, 1996), frequency-based collocation (setting the minimum frequency), and restriction on the contextual level (setting the threshold level at the window span like L3:R3, L5:R5, etc.) (Bartsch and Evert, 2014). The third element in Sinclair’s extended lexical unit is colligation.

The next element is semantic preference, which is defined in terms of semantic fields, to which a core’s collocate belongs (Oster and Lawick, 2008). It has been an intriguing research area for linguists to investigate and elaborate on how different lexemes in any given language are interrelated to each other vis-a-vis paradigmatic and syntagmatic domains.Footnote 2 The last element of the lexical unit model is semantic prosody, which Sinclair (1998) defines as the integral aspect of a lexical unit, i.e., the notion discloses the pragmatic aspect of the lexemes. When a node/core is analyzed with respect to its collocates or neighboring lexemes, the node in a particular setting gets an evaluative meaning which may be either positive or negative (Zethsen, 2006).

When it comes to critical discourse analysis, it does not cater to linguistic units solely, rather it looks for the embedded complex social reality that is the real agent for the production of any discourse. Though most often misunderstood as the study of only negative aspects of social reality due to the lexeme ‘critical’, CDA is not just restricted to the negative strands, yet it involves the critical investigation of any social phenomenon through multi-disciplinary approaches (Wodak and Meyer, 2009).

As CDA is enriched with many schools of thought and a number of theorists, we have focussed our qualitative analysis by combining various methods employed by multiple theorists. Reisigl and Wodak (2001) present their model comprising five strategies, namely nomination, predication, argumentation, perspectivization, and mitigation. The first one refers to how groups are mentioned, the second lays stress on what qualities and actions are attributed to them, and as the rest of these are not utilized, we have not discussed them. Apart from these strategies, we have also taken aid from van Leeuwen’s (2008) categorization of social actors’ representation. He offers three basic transformation strands comprising of ‘deletion, rearrangement and substitution’ (Davari and Moini, 2016) and later offers a taxonomy for each strand. Similarly, in the wake of the War on Terror, the notion of an ideological square is significant to analyze the dichotomy of friends vs. enemies, so Van Dijk’s ideological square of ‘Us vs. Them’ is also utilized. Van Dijk views discourse analysis as a domain where ideologies are embedded implying that discourse analysis is primarily about uncovering ideologies. His emphasis is on examining the ‘Us vs. Them’ dichotomy in discourse, which he labels as the ideological square (van Dijk, 2006). It implies that ingroup members are presented positively whereas the outgroup members are presented negatively. Such kind of approach takes into account the power relations of the participants along with studying the wider social, political, and historical backgrounds (van Dijk, 1998). Van Dijk’s approach majorly takes into account how the media reproduces images of certain groups.

Limitations

Since the paper focuses on a particular actor and a particular decade, it has been restricted to the noun–noun combination of lexemes to suit the feasibility of the project, as well as to keep the study in line with the above-mentioned objectives.

Material and methodology

The parameters set in the research reflect its aim to unveil the dynamics of media discourse and power. For this purpose, the research sample comprises the most pertinent media source during the decade selected for the research. Time magazine was first published in the United States in 1923 (Shedden, 2015) and by 2010 it had an average circulation of 3,313,715 (Rosenstiel and Mitchell, 2011). As it has a large circulation not only in the US but abroad, this research utilizes a corpus on Pakistan in which articles published in Time magazine from post-September 11, 2001, to December 2010 are included. Apart from its large circulation and international reach, Time magazine is the preferred choice instead of any other newspaper as it is weekly, so it offers a more sophisticated, thorough, well thought, and critical perspective than daily newspapers which might follow the media frenzy approach to publish news.

In total, we selected 509 articles from Time magazine. All the magazines from post 9/11 to 2010 were annually searched to look for articles containing any reference to Pakistan*. This stage was carried out at the University library of Karl Franzens University of Graz, Austria due to the availability of the Time archives.

To study the representation of Musharraf from Time Pakistan Corpus, two software, GraphCollFootnote 3 and WordsmithFootnote 4 have been used. Subsequently, to search for particular instances, the core Musharraf* has been searched in the corpus (*implies that all variants of the term are included such as possessive case, Musharrraf’s). However, since the core generated numerous collocates, only noun collocates have been manually assigned semantic categories considering the feasibility of the project. The Noun–Noun collocates are used as the focus of this study is on the nomination and predication strategies.

The results generated have then been presented under the “Results and discussion” section. This section has been further divided into three parts which include identifying: (i) a diachronic pattern of the core; (ii) the most significant and strong collocates; and (iii) the top eight most frequent semantic categories (noun–noun combinations). For the diachronic pattern, the absolute frequency of the core is calculated whereas, for significance and strength, two statistical tests, the t and MI2, have been used with p-value < 0.05. t-test (value above 2 is significant) is used to find the significance of the relationship between Musharraf* and its collocates (window span R5–L5, statistical value = 4, and frequency = 10). Similarly, the MI2 has been used to measure the strength of the collocates (window span R5–L5, statistical value = 10 and frequency = 10). With both tests, the frequency of collocates is set at 10, to find the patterns, but the statistical value varies for M12 as the purpose is to find strong collocates (a statistical value of 9 is considered as a strong association).

For the last section, the collocates have been assigned semantic categories manually and their absolute frequency has been counted. As pointed out earlier, the noun–noun combination has been restricted for the feasibility of the project as well as to keep the study in line with the above-mentioned objectives.

From a methodological perspective, various studies have examined actors or groups of actors using linguistic analyses. Van Leeuwen’s strategies on the representation of social actors (2008) and Reisigl and Wodak’s work on antisemitism (2001) are seminal works in the domain of actors’ representation. Several other studies follow in their footsteps (see Amer, 2017; Davari and Moini, 2016; Koller, 2009). However, most of these studies are geared toward social actors in terms of group identity, and not much research has been conducted from the perspective of an individual actor. The reason for not selecting any one theorist and their strategies lies in the fact that the present research encompasses a multitude of issues such as Pakistani politics, military institutes, actor’s representation as well as foreign policy aspects. Therefore, the researchers deemed it necessary to use the integrated approach by utilizing the three CDA strands mentioned above. Leeuwen and Reisgel and Wodak’s strategies are basically geared towards marginalization and linguistic strategies of legitimization, whereas Dijk’s theory has more of a political orientation. Therefore, the present research keeping in view its vast interdisciplinary aspects utilizes the integrated approach while analyzing through the lens of CDA.

So, this research has referred to van Leeuwen’s (2008), and Reisigl and Wodak’s (2001) established strategies (nomination and predication) to construct a framework to study the collocates of Musharraf* (see Table 1).

More than 30 semantic categories associated with noun-collocates of Musharraf* have been manually generated and then the frequency of each category has been counted on the basis of percentage values. The categories generated have been based on close reading and rereading of relevant texts which fall within the purview of the previously outlined standard of friends, foes, and—in the particular case of Pakistan—the breakdown of this structure. Due to the considerations of feasibility and significance of categories, only the top 8 categories have been selected for comparison (percentage value of < 2) (Tables 2 and 3).

For qualitative analysis, the extracts are analyzed in a broader political context to understand the reasons for marking the identity of the actor understudy.

Results and discussion

The analysis of Pervez Musharraf is broadly divided into three sections. These are the identification of the time pattern in the occurrences of Musharraf*, its most significant and strongest collocates, and lastly, the semantic categorization of all the collocates of Musharraf*.

Time pattern of Musharraf*

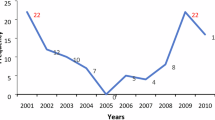

To scrutinize the instances of Musharraf* per year in the data, the absolute frequency of the core is calculated and converted onto a line graph.

Figure 1 displays the highest peak in the year 2007, and a sharp decrease after it. The minimum frequency is observed in 2010. In the years 2001 and 2002, Musharraf is mentioned more in the wake of the war on terror and also due to rising tensions between Pakistan and India. The highest peak in the year 2007 has been attributed to turbulent domestic conditions within Pakistan. The year was marked by turbulence on the judicial, political, and security fronts. On the international level, the Pak–US relationship also became tense over the issues of terrorism and democratic governance in Pakistan, hence the increased coverage led to peaking in the occurrence of the term. The subsequent sharp decrease can be explained again based on the ground realities of Pakistan’s domestic politics; Musharraf resigned in 2008 fearing impeachment. As he no longer remained the representative of Pakistan as the US ally and had no authority, his importance ebbed and so did his media coverage.

Top collocates of Musharraf*

In this section, two different results have been obtained by using the t-test and M12 test. The reason for selecting the first test is to find and determine the probability of significant associations between Musharraf* and its collocates. Whereas the second test is used to find the strength of the relations between the term and its collocates.

The t-test at the set threshold level yields 37 collocates where the majority of which are grammatical words. The content words appear in third, fourth, 17th, 19th, 20th, 22nd, 23rd, 25th, 26th, and 30th rank. The top content word is the first name of Musharraf whereas the president, Pakistani, Pakistan, Pakistan’s, general, and military all appear to be the identity markers. Musharraf’s representation in the media is skewed towards his political identity as president instead of his military identity; both general and military rank are at the bottom. President appears at fourth and the general appears at 23rd rank. This demarcation in ranks signifies that Musharraf’s identity is based more on the political aspect rather than the military aspect. Likewise, Musharraf* and the U.S. significantly collocate together, thereby, suggesting a relationship between the two. The only person who appears to have the probability of occurring in the vicinity of Musharraf* is the former President of the US, implying a more frequent interaction between the two. The last content word is the power which signifies Musharraf’s authority. It also points towards the negotiation of power between the US and Pakistani authorities as and when it aligns with the broader ambitions of the US foreign policy.

In order to further study the strength of collocates with Musharraf, MI2 is applied with a set threshold level; it generated 16 strong collocates, where again the first name of Musharraf appears to be strongest, implying that he is frequently referred to with his full name to retain the level of formality in the news. It is, then, followed by the president in 2nd rank and the general in fourth place. The ranking of the two lexemes further strengthens the argument that Musharraf’s identity is more strongly connected with politics as opposed to the military. As pointed out above, this is reflective of the foreign policy ambitions which are justified by establishing Musharraf’s identity as a democratic leader, instead of a military dictator. It is thus easier to garner public support for a democratic American ally instead of a non-democratically. The MI2 ranking at the set threshold level does not include the lexeme US but it does include Bush at the 12th position, signifying a strong association between him and Musharraf. All the content-based collocates that appear in the MI2 list except U.S. and 1999 are the same as the ones in the t-test list.

The visualization of both lists is generated in the form of a collocation network graph. The length of the lines joining the core with the collocates is significant; the shorter the line, the more significant and stronger the probability of association (see Figs. 2 and 3). Though more words appear in the t-test list, the content words in both lists (except two collocates) are the same, thereby signifying the reliability of the results.

All the content words which appear in both lists are further qualitatively explained in the next section.

Semantic categories

In this section, the top eight semantic categories collocating with the node are discussed.

Figure 4 explicates that the major category appears to be Politics with 21.3% occurrence, followed by Proper Nouns (19.4%), and Country and Nationality with 9.9% occurrence. These three categories carry more than 50% weightage with respect to overall semantic categories associated with N-collocates of Musharraf*. It is evident from the above graph that the semantic category of Politics (PL) carries more weightage than the Military and Intelligence category (ML), where the former has a 14.4 more percentage value than the latter. This result shows consistency with the result obtained via GraphColl where President General Pervez Musharraf’s identity is tied significantly and more strongly with politics rather than the military. Similarly, though the category of Reputation (RP) has the least percentage value in the top eight categories, yet by further expanding the concordance lines, this category reveals interesting insights. So, among all these categories, the following key findings have been observed on the basis of nomination and predication strategies.

Musharraf’s political identity vs. Military One

Working along the lines of binaries, the present research indicates that when it comes to establishing the identity markers for the understudy actor, the strict dichotomy of political vs. military identity is not established. In line with the US foreign policy, the majority of the time the political identity of the actor is more pronounced and there is downplaying of the military identity.

For example, in the category of Politics collocates like President, regime, and rule all signify Musharraf’s political identity. Frequently, he is addressed with the title of President rather than General (see the previous section). This toning down of his military title seems to be deliberate to hide the fact that the US was backing a non-democratic regime that goes against the core American values. Similarly, Musharraf is presented as doomed in various political issues, where he is facing the brunt of political opposition. At the same time, words such as government are also used to hide the non-democratic aspect of the (General) President (see Fig. 5).

On the other hand, in the category of Military and Intelligence words such as General, army, soldiers, Chief, and ISI are included. The most frequent word appears to be the military title of Musharraf signifying his military stature. In the case of generals, the negative authority is associated with Musharraf who is said to be exercising his power wantonly. The instances of this include the clearing off of the names of some generals in the nuclear proliferation charge, and in the dismissal of some other officials. It implies that he is in favor of some and against other officials (see Fig. 6). When contrasted with the previous representation of Musharraf as president, this type of representation manifests some stark changes in the media discourse. Musharraf’s exercise of power is linked with negative frames such as general and military, all of which portray him as an undemocratic leader. This type of discourse manipulation comes into play when his actions need to be criticized. However—as in the previous case—when it is time to gather support for Musharraf as a reliable ally, his role as a democratic president is highlighted. This exhibits how power is fluidly attached to, and detached from Musharraf as an independent actor depending on his alignment with US foreign policy ambitions.

Support vs. criticism against Musharraf: mixed aspects

As far as support is considered for the said actor, again the findings reveal a mixed perspective where he is backed by the US officials on one hand, and at the same time, his actions and policies were also subject to severe criticism.

In the category of Proper Names of Multiple Actors, the major international actor tied with Musharraf is President George Bush. The former President Bush is said to be acting like a boss, an ally, and a critic to Musharraf (see Fig. 7).

Such projection of the US President is indicative of the positive image of the US which is portrayed as having a strong commitment to the war against terror, whereas Musharraf is at times presented as a partner who is following the US orders. But this projection of a partner appears to change after 2007 and the media raises questions about Musharraf’s policies when stating for example,

…the Bush Administration has consistently praised Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf for his cooperation in rooting out and apprehending members of bin Laden’s network (Baker, 2007).

The stakes were high: President Bush had just called for Musharraf to hold new elections (Zagorin and Calabresi, 2008).

Similarly, in the category of Country and Nationality (CN), the most frequently appearing country (including the names of cities) is the US. This is again suggestive of the idea that when foreign countries are presented in the US media, foreign policy is always linked to that country. Interestingly, instead of using the phrase Bush’s government/administration, Washington is personified, and the actual names of US officials allying with the actor under study are not mentioned (see Fig. 8). The US is represented as a collective, thus lending it collective power, whereas Pakistan is reduced to Musharraf.

In theory, the government of Pakistan’s President Pervez Musharraf is committed to routing al-Qaeda elements from redoubts within Pakistan.

Washington pressured the Pakistani government of General Pervez Musharraf to crack down on LeT, Jaish, and others, which by then were on the State Department’s list of proscribed terrorist organizations”.

Although outwardly supportive of Musharraf’s government, U.S. military officials have quietly been questioning just how intensely it is battling the Taliban and al-Qaeda fighters who cross routinely between Pakistan and Afghanistan (Powell, 2006).

All these instances highlight how Musharraf’s identity as a President is non-controversial and at the same time depicts the U.S. administration’s dubious trust in him. The last two are particularly interesting cases where the journalists are presenting the U.S. administration to be the one that is pressurizing Musharraf to act against certain organizations and simultaneously expressing the dubious nature of the alliance between the U.S. and Musharraf. These instances also exhibit the constant negotiation of power between Musharraf (as a democratic leader in control of his country’s affairs), and the American authorities (dictating Musharraf to act in line with the US foreign policy ambitions). Here it is also pertinent to mention that in the corpus the lexeme dictatorship is used only twice as a collocate of the node, which again highlights the toning down of the non-democratic aspect of Musharraf’s government.

Musharraf as playing a double game

The media understudy also presents Musharraf to be playing a double against the War on Terror where at times conducting military operations against the declared terrorist organizations as well as supporting them through various channels.

In this respect, the Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI) is presented as an organization that needs to be tamed by Musharraf. Expanding the concordance lines reveals that the said organization is presented in a highly negative light. It is portrayed as rogue and uncouth due to its association with the Taliban; yet a positive image for Musharraf’s image is built by highlighting his commitment to the war on terror.

Some Pakistani investigators and newspapers in the U.S. have speculated that rogue elements linked to the ISI wanted to demonstrate to Musharraf and the world that they were not so easily tamed (Gibbs et al., 2002).

The first move Musharraf made to tame the ISI was dumping its chief, Ahmed (Mcgirk et al., 2002).

Under the category of War and Terror (WT), the War signifies (i) Musharraf’s involvement in the war on terror, (ii) Musharraf’s association with the war against India and Afghanistan, (iii) him being a target, and (iv) his commitment to reshaping Pakistan. Footnote 5

With his unflinching decision to join America’s war on terrorism, Musharraf initiated one of the most dramatic U-turns in Pakistan’s history (Mcgeary et al., 2001).

Musharraf’s battle to reshape Pakistan is a lonely one. No political party backs him (Mcgeary et al., 2001).

The above examples indicate Musharraf’s decision on being a US ally against the political environment of Pakistan, and for this, he is presented as a person who single-handedly made a commitment to War on Terror. Such a projection is suggestive of his strong determination against curbing terrorism. He is also presented to have faced domestic consequences where various assassination attempts were targeted toward him. The expansion of the word assassination brings to the forefront, the assassination attempts on Musharraf as a retaliation of organizations against Musharraf’s policy to side with the US (see Fig. 9).

Whereas, when it comes to questioning the policies of Musharraf in the War on Terror, subtle comments are made, and too again the actors articulating such concerns remain devoid of proper names.

Musharraf has to balance Washington’s demands against the fact that many Pakistanis are sympathetic to the Taliban and al-Qaeda and particularly to the militants in Kashmir.

Although outwardly supportive of Musharraf’s government, U.S. military officials have quietly been questioning just how intensely it is battling the Taliban and al-Qaeda fighters who cross routinely between Pakistan and Afghanistan (Powell, 2006).

In the second example, U.S. officials remain anonymous so as to downplay the identity of such actors on one hand as well as to keep the criticism against Musharraf against War on Terror to be low key.

Friend vs. foe

Keeping in view the binary aspect of friend vs. foe, the findings suggest that the stark demarcation does not exist on these lines. Various semantic categories indicate that Musharraf is at times presented as an ally whereas on other occasions he is presented to be siding with the US enemies. So, the Bush Doctrine of Us vs. Them again seems to be not applicable to the representation of the said actor.

For example, in the category of Reputation (RP), the most frequent collocate is ally showing a positive association between Musharraf and the US government. He is presented as a person who is backed by the US. It is also interesting to note that the lexeme dictator appears only four times as the collocate of Musharraf, in order to highlight his non-democratic regime.

Some Pakistanis who have excused Musharraf’s authoritarianism in the past now portray him as a jackbooted dictator (Baker, 2007).

The State Department’s South Asia bureau, according to a participant in the meetings, argued that a fistful of other issues—Kashmir, nuclear proliferation, Musharraf’s dictatorship—were just as pressing as terrorism.

The above examples again illustrate that unspecified actors (their collective identity rather than actual names) are used as a mouthpiece to articulate the dictatorial aspect of Musharraf’s regime. The rest of the words in this category are inherently positive such as hero, pal, leader, ruler, etc. This category again backs the proposition that the media under study has intentionally tried to downplay the non-democratic aspect of Musharraf’s government as highlighting this strand would have raised questions and opposition for the US government as a backer of a non-democratic government. Thus, in this way, the criticism of the US foreign policy is avoided.

However, his representation as a military man is brought to the forefront when the US needs to show its displeasure with the arbitrary actions taken by Musharraf. In the category of Power and Authority (PA), all those collocates of Musharraf* which show a relation to one another in terms of power and authority are included, irrespective of their use and abuse. The power collocate is mainly associated with Musharraf* depicting him as the agent who has gained power (in both a positive and negative sense) and exercises it. Power is used in the sense of taking control of the government in a military coup, as well as in the sense of having authority to exercise his plans (see Fig. 10). Thus, power remains something fluid and moldable.

Similarly, the collocates such as ban, restrictions, pardon, dismissal, contravention, blow, retreats, coup, threat*, influence, arrest* meddling, and tactics, all point towards the misuse of authority by Musharraf against a rape victim, the judiciary, and critics. He is criticized for being lenient on militants and a Pakistani scientist involved in a nuclear proliferation case.

All in all, across all such instances, the power and authority attributed to the president/general remain fluid and negotiable. Similarly, while usually portrayed as an ally or friend, Musharraf and Pakistani institutions such as the ISI (and hence Pakistan itself) are often pushed into a gray category of being rogue and dangerous. While not labeled explicitly as an enemy, Musharraf, and Pakistan’s representation is allowed to traverse back and forth across the friend or foe continuum. This highlights the alternate representation of the country, which does not fit easily into binary categories.

Concluding remarks

Discourse is a social practice that interacts dialectically with other social elements. It not only reflects societal structures but also helps to shape and reshape them. Discursive practices are influenced by complex societal dynamics. In the case examined in the present study, the US media was mobilized to discursively promote the agendas underlying the US foreign policy. Foreign countries were conferred status and deemed newsworthy in the US media as long as helped manifest strategic ambitions tied to the US foreign policy.

Pakistan, its institutions, and individual actors acting on behalf of the state were all similarly discursively manipulated during the war on terror. Pakistan acted as a US ally in the aftermath of 9/11, and the presence of US correspondents in Pakistan gave it a huge amount of coverage. Despite the fact that President Pervez Musharraf came to power via a military coup, the US government-backed him as he was considered crucial for the US foreign policy pertaining to the war on terror. This paper has analyzed the coverage of Pakistan, in particular General Musharraf, to explore how Pakistan was situated on the friend or foe/ally or enemy spectrum in Time magazine.

The first part of the analysis diachronically presents how time plays a crucial role in the frequency with which he is represented. Two peaks are observed in 2002 and 2007. Here Musharraf was propelled to the forefront of the media discourse since he was the key player in the war on terror. Similarly, internal issues in the country and the change in the US foreign policy towards Pakistan also resulted in increased coverage for the president. The trends in 2009 and 2010 revealed that Musharraf was only covered as long as he was in power as the representative of Pakistan.

Similarly, the second section of the analysis reveals (statistically) that his identity was fostered in terms of a politician, and the military title was downplayed, thereby downplaying the fact that the US government was backing a non-democratic regime. Similarly, this section also highlights a strong correlation between President Pervez Musharraf and President George Bush, signifying increased focus on the bi-personal relations between the two actors and countries at large.

The third strand of analysis pertaining to the semantic categorization of collocates involves qualitative analysis. This again fosters a similar idea that the identity of the actor under study is represented as belonging to the political arena rather than the military one. He is backed, dictated to, and yet criticized by the US government on many occasions. The low frequency of words like dictator signifies the downplaying of the negative association with the issues of democracy, which later became apparent in the news coverage in 2007. His actions comprise both positive and negative strands, where on the one hand he is performing his role in the war on terror, and on the other hand misusing his authority. Thus, Musharraf is presented not on the ‘us vs. them’ demarcation, but he is a unique case presented as a dubiouse ally.

This reason for this position perhaps lies in the US foreign policy which backed him till 2007 and later changed its direction against him, thereby implying that the media under scrutiny might have a political leaning towards the US foreign policy. The American media discourse constructed an alternate identity in the case of Musharraf (from 2001 to 2010) in Time magazine. The construction of an alternate identity here results from the interaction of different factors like the war on terror, and dictatorship vs. democracy in Pakistan, that were at play during the time period taken dialectically produced the construction of an alternate identity that is dubious in nature and deconstruct the binarism popular at the same time period.

Discursive practices help to create and maintain uneven power relations between social groups, such as between socioeconomic classes, between men and women, and between ethnic minorities and the majority and we can extend it to the relations between different states. These outcomes are seen as ideological outcomes, here foreign policy is taken as an ideological resource already mentioned above, which has created representation and framing of Pervaiz Musharraf in Time magazine. This idiosyncratic position of (General) President Pervez Musharraf in the US media implies that Pakistan as a country is presented on similar lines. Such positioning is thought-provoking as much research on the ideology of the ‘us vs. them’ concludes that the US media has covered countries and actors strictly on this fine demarcation. Thus, the present research paves way for future researchers to find such unique positioning of foreign actors in the US media when it comes to the war on terror.

The Pak–US social ties served as both the center of power and the place where meaning was created. This research observes that power and meaning are deeply interwoven, far more so than has typically been acknowledged in the study of international politics (Jørgensen and Phillips, 2002). The Power of media has an impact on which social construct is being built (Jørgensen and Phillips, 2002). The association between power and concentrating on subject positions provides a valuable method of examining identity since it takes into account all the major issues pertaining to identity (matters) in international relations. Critical discourse analysis is “critical” in the sense that it seeks to illuminate the function of discursive action in the upkeep of the social order, including those social relations characterized by unequal power relations. As this research exhibits, the inequality existing in the power between Pak–US relations has actually contributed to the framing of Pakistan as the alternate identity (dubiouse ally). This research paper will have achieved its goals if it has created a place for critically analyzing the discourses that we unconsciously engage in over the course of our daily lives, or if it has inspired a closer consideration beyond the binarism in the set discourse of Us ally vs. enemy in post-9/11international politics.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings were obtained from Time Magazine. However, data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Notes

This was in contrast to the usual, draconian representations of military dictators in other countries, e.g. Gen. Gaddafi, etc. See f.i. Macías, A. F. O. (2019). The fall of Gaddafi through CNN and Fox news: the spectacular enemy vision according to Edelman Murray. Ánfora 26(46).

The repertoire of research on locating the relationship of words and their meanings points out that the roots of the semantic field are dubious where some linguists believe that it lies in the ideology of Humboldt and others associate it with the philosophy of structuralism laid down by Ferdinand Saussure.

Version 2

Version 5

The term battle is used metaphorically.

References

Amer M (2017) Critical discourse analysis of war reporting in the international press: the case of the Gaza war of 2008–2009. Palgrave Commun 3:13

Baker A (2007) The truth about Talibanization. Time, 4 February

Baker P, Gabrielatos C, KhosraviNik M et al. (2008) A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press. Discourse Soc 19(3):273–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926508088962. SAGE Publications Ltd

Balmas M, Sheafer T (2013) Leaders first, countries after: mediated political personalization in the international arena. J Commun 63(3):454–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12027

Brown G, Yule G (1982) Discourse analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bartsch S, Evert S (2014) Towards a firthian notion of collocation. Network strategies, access structures and automatic extraction of lexicographical information. 2nd Work report of the academic network internet lexicography. OPAL–Online publizierte Arbeiten zur Linguistik, Institut fur Deutsche ¨ Sprache, Mannheim

Breeze R (2011) Critical discourse analysis and its critics. Pragmatics 21(4):493–525

Davari S, Moini M (2016) The representation of social actors in top notch textbook series: a critical discourse analysis perspective. Int J Foreign Language Teach Res 4(13):69–82

Frizis L (2013) The impact of media on foreign policy. https://www.e-ir.info/2013/05/10/the-impact-of-media-on-foreign-policy/. Accessed 12 Aug 2022

Gibbs N et al (2002) Death in the shadowy war. Time, 4 March

Haider AS (2019) Using corpus linguistic techniques in (critical) discourse studies reduces but does not remove bias: evidence from an Arabic corpus about refugees. Poznan Stud Contemp Linguist 55(1):89–133

Haider AS (2017) Using corpus linguistic techniques in critical discourse studies: some comments on the combination. Department of Linguistics, University of Canterbury

Herbst T (1996) What are collocations: sandy beaches or false teeth? Engl Stud 77(4):379–393

Jaworska S (2016) A comparative corpus-assisted discourse study of the representations of hosts in promotional tourism discourse. Corpora 11(1):83–111. https://doi.org/10.3366/cor.2016.0086

Jørgensen M, Phillips L (2002) Discourse analysis as theory and method. SAGE Publications Ltd, London, England, UK

Kellner D (2004) 9/11, Spectacles of terror, and media manipulation. Crit Discourse Stud 1(1):41–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405900410001674515

Koller V (2009) Analysing collective identity in discourse: social actors and contexts. Semen 27. http://journals.openedition.org/semen/8877

Krishnamurthy R (1996) Ethnic, racial and tribal: the language of racism? In: Caldas Coulthard CR, Coulthard M (Eds.) Texts and practices: readings in critical discourse analysis. Routledge, London, England, pp. 129–149

van Leeuwen T (2008) Discourse and practice. Oxford University Press, New York

McAllister I (2007) The personalization of politics. In: Dalton RJ, Klingemann H-D (eds) The Oxford handbook of political behavior. Oxford University Press

Mcgeary J et al (2001) The world’s toughest job. Time, 22 October

Mcgirk T, Baloch H, Calabresi M (2002) How Pakistan tamed its spies. Time, 28 April

Oster ULawick HV (2008) Semantic preference and semantic prosody: a corpus-based analysis of translation-relevant aspects of the meaning of phraseological units. Transl Mean part 8:333–344

Partington A (2014) Mind the gaps: the role of corpus linguistics in researching absences. Int J Corpus Linguist 19(1):118–146

Partington A, Charlotte T, Alison D (2013) Patterns and meanings in discourse. theory and practice in corpus-assisted discourse studies (CADS). John Benjamins, UK

Powell B (2006) A terrorist’s network. Time, 28 August

Reisigl M, Wodak R (2001) Discourse and discrimination: rhetorics of racism and antisemitism. Routledge, London

Rogers R, Malancharuvil-Berkes E, Mosley M, Hui D, Joseph G (2005) Critical discourse analysis in education: a review of the literature. Rev Educ Res 75(3):365–416

Rosenstiel T, Mitchell A (2011) The State of the News Media: an annual report on American journalism. Pew Research Center. http://assets.pewresearch.org/wpcontent/uploads/sites/13/2017/05/24141615/State-of-the-News-Media-Report2011-FINAL.pdf

Samaie M, Mahmir B (2017) US news media portrayal of Islam and Muslims: a corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis. Educ Philos Theory 49(14):1351–1366

Shedden D (2015) Today in Media History: the first issue of Time magazine was published 92 years ago. Time Magazine

Sinclair JM (1998) The Lexical Item. John Benjamins Publishing Company

Stubbs M (1994) Grammar, text and ideology. Appl Linguist 15(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/15.2.201

Van Dijk TA (1998) Ideology. SAGE, London

Van Dijk TA (2006) Politics, ideology and discourse. In: Brown K (ed) Encyclopaedia of language and linguistics, Taylor & Francis vol 9. pp. 728–740

Widdowson HG (1998) The theory and practice of critical discourse analysis. Appl Linguist 19(1):136–151

Widdowson HG (1996) Linguistics: an introduction. Oxford University Press, New York

White SL (2017) Applying corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis to an unrestricted corpus: a case study in Indonesian and Malay Newspapers. All Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6478

Wodak R, Meyer M (2009) Critical discourse analysis: history, agenda, theory and methodology. In: Wodak Ruth, Meyer Michael eds Methods for critical discourse analysis. Sage Publications, London

Zagorin A, Calabresi M (2008) Washington memo. Time, 17 March

Zethsen KK(2006) Semantic prosody: creating awareness about a versatile tool Tidsskr Sprogforsk 4(1):275–294. https://doi.org/10.7146/tfs.v4i1.324

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

No human participation was performed in this study. Therefore, informed consent does not apply to it.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Javed, T., Sun, J. & Khurshid, A. No more binaries: a case of Pakistan as an anomalistic discourse in American print media (2001–2010). Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 65 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01557-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01557-6