Abstract

The transition of a country or a whole society to sustainability is a long-term goal that involves a society’s willingness to carry out such a change and the governance structure to support it. Understanding the role of the governance structure in enabling or constraining the change dynamics of societal values can more effectively foster desired transitions. This paper aims to reveal the co-evolutionary dynamics in the transition processes of the societal value of water resources and the network configurations of water governance in Australia and China in different socioecological contexts. Newspapers were used to track societal value and structural change in water governance. One mainstream newspaper was selected from each country, spanning a timeframe of 175 years in Australia and 72 years in China. The key finding is that the transition in societal value in both countries followed a similar sigmoid function. The value transition process in both countries benefited from a centralized governance structure, particularly in the take-off stage of the transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The fundamental societal value transition to sustainability has become necessary to address the challenges in the Anthropocene (Gleick, 2018; Loorbach et al., 2017). Such a transition is a long-term, multidimensional, and fundamental transformative process involving a society’s willingness to carry out such a transition and the governance system’s structural arrangement to support it. Understanding the mechanism of societal value transition can assist in anticipating and adapting to desirable shifts and exploring possibilities to advance and accelerate them (Loorbach et al., 2017; De Haan and Rotmans, 2018; Geels and Schot, 2007; Farla et al., 2012; Geels, 2011).

A society’s willingness to carry out this type of transition and a country’s governance reform are two interactive processes. As an indicator of a person’s or society’s beliefs about human–environment interactions (Turner et al., 2014), value has potential implications for the willingness to engage in decision-making, support for management, and compliance with regulations (Mora et al., 2009; Nielsen and Mathiesen, 2003). According to Johannessen et al. (2019), social learning plays a crucial role in supporting the transformation of water governance. They studied three types of social-learning loops and found that single and double loops involve indirect triggers of transition, while a triple loop leads to a shift in norms and values, as well as changes in governance. Thus, understanding societal value is vital for developing effective natural resource management governance (Bennett and Dearden, 2014; Domènech and Saurí, 2010; Hartley, 2006; Heberlein, 2012; Itaoka et al., 2005; Larson et al., 2009; Rivera et al., 2017; Turner et al., 2014; Webb et al., 2004). Meanwhile, water governance can influence public perceptions of the need for water sustainability transitions and public support for transformational water management (White et al., 2019). In addition, water governance is an inherently complex process involving the dynamics of the hydrological cycle and the shifting roles of multiple actors and sectors in the governance system that influence water resources at various scales (Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016; Fischer and Newig, 2016; Wittmayer et al., 2017; Geels, 2010; Stein et al., 2011; Vignola et al., 2013; Sayles and Baggio, 2017; Turner et al., 2014; Voss et al., 2006; Underdal, 2010). The role of the governance system in steering society toward desirable outcomes has been emphasized by some scholars (Young et al., 2015). Furthermore, it has been recognized that the logic of the structural configuration of governance plays a crucial role in determining the effectiveness of governance systems (Pahl-Wostl, 2019).

However, societal value and governance have often been examined separately in common pool resource management (Pahl-Wostl et al., 2010; Schiffer et al., 2010). As societal value is gaining increasing attention due to its influence on water resource management decisions and outcomes (Caldas et al., 2015), it has been examined in place-based models (Wei et al., 2017; Xiong et al., 2016), but there is a lack of understanding across multiple sites and socioecological contexts, which may mask the general mechanism.

There is a large body of literature on water governance. Finding analytical tools and approaches to translate the complex water governance arrangement into measurable data that can facilitate the communication of governance status to wide stakeholders remains challenging, and few studies have explored the links between societal values and governance arrangement. Therefore, this study aims to reveal the co-evolutionary dynamics in the transition processes of the societal value of water resources and the structural change in water governance by taking a comparative perspective based on Australia and China, which share similar water stresses but distinct governance systems and cultural backgrounds. Here, we show the evolutionary dynamics of the societal value transition and the water governance landscape and how multiple actors and their structural arrangement within the governance network affect the societal value transition to sustainability. The results of this research will contribute to a nuanced understanding of the multilevel and multi-factor water governance system and what, how, and when the water governance configuration can support the transition of societal value to sustainability.

Data collection and methods

Data sources and processing

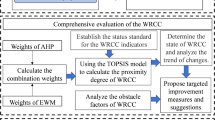

News media have been increasingly recognized and used as a valid proxy to track the societal value of water resources (Roznowski, 2003; Hale, 2010; Hurlimann and Dolnicar, 2012; Wei et al., 2015, 2017; Xiong et al., 2016). Meanwhile, news media have advantages in reflecting the everyday reality of governance regimes in terms of the multitude of involved actors from both formal and informal groups and the interactions among them (Carlsson and Berkes, 2005). This study chose newspapers as the data source, specifically one newspaper from each country (due to the limit on availability): the Sydney Morning Herald in Australia and the People’s Daily in China. Each newspaper chosen is the oldest continuously published newspaper with diverse coverage and a wide readership in both countries. As the transition in both societal value and institutional arrangement is a slow process, taking decades or even centuries to achieve (Stein et al., 2018, 2011), this study chose a longitudinal timeframe starting from the earliest date of digital availability: the 1843–2017 period for The Sydney Morning Herald and the 1946–2017 period for the People’s Daily. An overview of the data retrieval and analysis process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

To enable data analysis, a sampling method based on Wei et al. (2017) and Xiong et al., (2016) was used. The method involved sampling 4 weeks every year, including two constructed weeks and two consecutive weeks. A constructed week accounts for the cyclic nature of news content on randomly selected days from Monday to Sunday to artificially construct a week; a consecutive week is a sample of seven continuous days. Therefore, the sample includes one constructed week and one consecutive week each half year. In both cases, the “water week” was included in the samples, with the week starting from the 3rd Sunday of October in Australia and the 22 March in China. Several news databases were accessed that together provide a full record of digitized news content. For The Sydney Morning Herald, three databases were available: Trove (1843–1954), the Sydney Morning Herald (1955–1986), and Factiva (1987–2017). The People’s Daily Graphic Database includes all articles during the entire study period (1946–2017). The keyword “water” was used to retrieve articles.

The content analysis approach was applied to translate the unstructured information from a newspaper into a structured format. A coding table was designed to track the societal value of water resources based on Wei et al. (2015) and Xiong et al. (2016), including three main pieces of information: the publication date, article theme, and article tone (see Table 1). The article’s tone reflects an article’s position on societal values, which may be supportive of environmental protection, be supportive of economic growth, or unbiased. This would include both positive and negative perspectives on the problems being discussed. For example, the tone was considered economic development oriented if articles focused on topics that aim to meet the needs of economic development, such as the construction of water storage and irrigation delivery infrastructure for consumptive use. Articles that criticize the overuse of water resources for consumptive purposes and advocate sustainable water resource management would not be considered ‘economic development’ but, rather, ‘environmental sustainability.’

Similarly, articles addressing ecosystem degradation or water over-allocation were labeled “environmental sustainability oriented.” These two tones were coded to represent two distinct dimensions of water-related values. The governance information was derived from the “actors involved” variable for the multiple actors and their interactions. The actors we chose included organizations and individuals involved in the reported events on water resources. Influential individuals were identified as actors if they performed a prominent function and held a stable position over time, such as the prime minister or president of the country. For a tie to exist between two actors, they both need to be mentioned in the same articles concerning the same issues. Therefore, the actors and their interactions could, to the largest extent, reflect the everyday reality of social interaction among actors within water resource management. In addition, we included data on the actors’ attributes, i.e., the type of organization, ranging from an authority, a municipal government, a state government, a federal government, private companies, NGOs, and research institutes to influential individuals. It is noted that under different government and management systems, the classification of organizational attributes also differed slightly between these two countries.

A manual coding method was adopted, with two coders manually reading and coding all articles independently. Intercoder reliability was tested using the KALPHA macro (Hayes and Krippendorff, 2007) for each variable across 50 randomly selected articles. in the resulting reliability was 89.6%, which is well above the recommended level of 80% (Poindexter and Mccombs, 1999).

The initial search generated 40,687 articles in the Australian case, and 3463 were selected as relevant for analysis after the manual reviewing process; 148,136 articles were found in the Chinese case, which resulted in 1597 articles for analysis. More specifically, of the final 3463 articles for the Australian case, news accounted for 3174 articles, letters accounted for 283 articles, editorials accounted for 3 articles, and opinion pieces accounted for 3 articles. Of the 1597 articles in the Chinese case, there were 1368 general news articles, 80 letters, 94 editorials, and 55 opinion pieces.

Measuring the transition in societal value

Transitions are fundamental shifts in a policy, a belief, a technology, an institution, or a management strategy from one condition to a new condition (Gleick, 2018). A transition is a nonlinear process involving various patterns and pathways (De Haan and Rotmans, 2018; Geels and Schot, 2007), different stages (Grin et al., 2010; Rotmans, 2005), multiple actors (Farla et al., 2012; Geels, 2011), and high levels of co-evolution, complexity, and uncertainty (Geels, 2010; Rotmans and Loorbach, 2009; Wittmayer et al., 2017). As conceptually identified by Rotmans (2005), a successful transition goes through four different transition stages (see Supplementary Fig. 3): a predevelopment stage of dynamic equilibrium where the status quo does not visibly change; a take-off stage where the process of change gets underway because the state of the system begins to shift; an acceleration stage where visible structural changes take place relatively rapidly through an accumulation of changes; and a stabilization stage where the speed of social change decreases and a new dynamic equilibrium is reached. Transitions can fail in any of these stages. A backlash or a lock-in situation can develop, and the system may even collapse when the uncertainties and risks of chaos are too high.

Patterns in the societal value transition were identified by undertaking a regression analysis of the data derived from the coding process. Specifically, we regressed the percentage of articles favoring economic development and environmental sustainability over time to find the two best-fitting transition curves. To do so, several regression models, including exponential, log-linear, and sigmoid function models, were tried until the highest R2 was achieved. To identify the stages of transition, the first and second derivatives of the fitted curves were determined. The first derivative was used to describe the trend of change; the second derivative was used to describe the rate of change in societal value. When deciding the transition point, the maximum increasing acceleration rate from the 2nd derivative was used to determine the start of the take-off period, and the maximum acceleration rate from the 1st derivative was used to determine the start of the acceleration period.

Measuring actors and their interactions in water governance using social network analysis

Social network analysis (SNA) was adopted as an analytical tool to study multiple actors and their interactions. The SNA technique can characterize the network structure and position of a single actor in a network (Wasserman and Faust, 1994; Knoke and Yang, 2019; Borgatti et al., 2009; Chaffin et al., 2016). It enables the identification of central and bridging organizations whose activities connect actors that otherwise would not have been connected (Berkes, 2009; Rathwell and Peterson, 2012; Fliervoet et al., 2016). We measured changes in the actors and their interactions with the network metrics described in Supplementary Table 3.

At the whole network level, density was used as a measure of general group cohesion, i.e., the number of realized ties in the network (Wasserman and Faust, 1994). Centrality was used to complement density by describing the extent to which cohesion is organized around particular focal actors (Scott, 2011). They together describe how well a network is connected (Fliervoet et al., 2016). At the node level, degree was used to identify those actors who are extensively involved in relationships with other actors (the number of direct links to others), whereas betweenness was used to identify uniquely positioned nodes that provide bridging services to other nodes within a network (Stein et al., 2011). Together, they can locate influential actors (Freeman, 1978). UCINET (Borgatti et al., 2002) was employed to calculate the structural network properties at different levels of the network and to then visually ‘map’ the interactions between actors in both countries involved in water resource management over time.

Results

Evolution of societal value in Australia and China

In both cases, the societal value of environmental sustainability increased from the marginal level at the beginning to the dominant voice by the end of the study period. Regression analysis showed that the evolution of societal value closely followed a sigmoid function—the Boltzmann equation (see Fig. 2a, b), also known as an S curve, with an adjusted R2 of 0.8. The fitted sigmoid curves for the societal value of environmental sustainability (En) over time (t) are illustrated by Eq. (1) for the Australian case and Eq. (2) for the Chinese case:

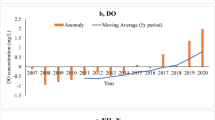

More specifically, “1995” in Eq. (1) and “2005” in Eq. (2) indicate that the year signifies the transition in societal value from economic development dominated to environmental sustainability dominated, and “20” in Eq. (1) and “12” are the slope factor indicating the steepness of the number of years over which societal value goes from 0 to 1. Transition stages were identified for both cases. In the Australian case, the predevelopment stage of the societal value of environmental sustainability was recognized as being from 1843 to 1968, when the change in societal value was only marginal. The take-off stage was considered to be the 1968–1995 period when the change rate of the speed of the change in societal value increased. The acceleration stage was identified as being from 1995 to 2017. This is the period when societal value was still growing and follows the time when the rate of change in societal value was maximized; during that period, the rate of change was slowing. The stabilization stage had not yet appeared because the societal value was changing quickly. Similarly, in the Chinese case, the predevelopment stage of the societal value of environmental sustainability was identified as being from 1946 to 1990, the take-off stage was identified as being from 1990 to 2005, and the acceleration stage was identified as being from 2005 to 2017. The themes under both environmental sustainability-oriented value and economic development-oriented value were decomposed into different themes to reflect the change in society’s major focus across the study period (see Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2).

Evolution in water governance in Australia and China

The overall social network map of the water governance network in Australia (Fig. 3a) and the temporal trajectory of water governance from the start of the predevelopment stage to the acceleration stage (Fig. 3b–d) illustrate the pattern of existing relationships among actors identified from news articles. The most central actor in Australia shifted from the state departments for infrastructure development in the predevelopment period to local water management authorities in the take-off stage to the state and federal governments during the acceleration stage. The governance network in China was predominantly hierarchical, with the Ministry of Water Resources as the most central actor (Fig. 4a–d). The predevelopment stage began with the Yellow River Water Conservancy Committee acting as the bridging actor. The take-off period was characterized by the dominance of ministerial departments. The network expanded to include more interest groups connected closer during the acceleration stage. See the detailed node-level metrics (including category, region, frequency, betweenness, degree, and closeness) in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. The establishment times of leading actors, as measured by the frequency and betweenness value, are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

a Overview of Water Governance in Australia between 1843 and 2017. b Water Governance Network in Australia in the Predevelopment Stage, 1843–1968. c Water Governance Network in Australia in the Take-Off Stage, 1968–1994. d Water Governance Network in Australia in the Acceleration Stage, 1994–2017. Notes: The nodes are grouped and colored by actor type. Each color represents actors from different groups, and the size of a node is proportional to the node’s betweenness value. NSW swsb NSW Sydney Water and Sewerage Board, Nsw stagov NSW state government, Nsw dept pubwork NSW Department of Public Works, Fed gov federal government, Nsw wcic NSW Water Conservation and Irrigation Commission, Csiro Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, Nsw syd cc NSW Sydney City Council, Nsw epa NSW Environment Protection Authority, Vic stagov Victoria state government, Nsw dept enviro NSW Department of Environment, MDBA Murray–Darling Basin Authority.

a Overview of the Water Governance Network in China between 1946 and 2017. b Water Governance Network in China during the Predevelopment Stage, 1946–1990. c Water Governance Network in China during the Take-Off Stage, 1990–2005. d Water Governance Network in China during the Acceleration Stage, 2005–2017. Notes: The nodes are grouped and colored by organizational type. Each color represents actors from a different group, and the size of a node is proportional to the node’s betweenness value. MWR Ministry of Water Resources, YRC Yellow River Committee, MEP Ministry of Environmental Protection, SFCDRA State Flood Control and Drought Relief Authority, SDP YRB Shandong Province Yellow River Bureau, BJWA Beijing Water Authority.

Co-evolutionary interaction between governance and the societal value of water resources in Australia and China

The co-evolution of the societal value transition with the governance arrangement, in terms of its structural characteristics (group-level metrics including the number of ties, the number of nodes, density, and centrality) and the main bridging actors, are shown in Figs. 5 and 6. In both cases, the take-off stage is associated with a highly centralized governance network (reaching the peak centrality value) with fewer actors involved.

The nodes are colored by actor type; the size of a node is proportional to the node’s betweenness value. NSW swsb NSW Sydney Water and Sewerage Board, Nsw stagov NSW state government, Nsw Dept PW NSW Department of Public Works, Fed gov federal government, Nsw wcic NSW Water Conservation and Irrigation Commission, Nsw dept EN NSW Department of Environment; MDBA Murray–Darling Basin Authority.

The nodes are colored by actor type; the size of a node is proportional to the node’s betweenness value. MWR Ministry of Water Resources, YRC Yellow River Committee, MEP Ministry of Environmental Protection, SFCDRA State Flood Control and Drought Relief Authority, SDP YRB Shandong Province Yellow River Bureau, MR Ministry of Railways, MT Ministry of Transport, Uni Lanzhou University of Lanzhou, BWA Beijing Water Authority.

More specifically, in the Australian case, societal value at the start of the predevelopment stage (1843–1968) was dominated by economic development, being primarily concerned with urban and agricultural water use to satisfy essential settlement needs, as reflected in the themes ‘water for urban use,’ ‘natural hazards,’ ‘water for agriculture,’ and ‘water storage and river management’ in Supplementary Fig. 1a. Therefore, local water management agencies such as the New South Wales (NSW) Department of public works, NSW Sydney Water and Sewerage Board, and NSW state government were the most central actors within the management regime (see Fig. 5) for infrastructure development as well as the legislative process to enable agricultural expansion and national economic growth. This period witnessed massive growth in storage capacity and both state-owned dam and mega project development across the country, as reflected in the steady increase in the theme ‘water storage and river management’ (see Supplementary Fig. 1a).

The take-off period (1968–1994) saw dramatic changes in community attitudes toward the environment, prompted by the emergence of environmental incidents such as industrial pollution in waterways and soil erosion. The rising awareness can also be seen in the contribution from the themes ‘water for the environment,’ ‘water quality and health,’ and ‘water policy reform and integrated management’ (see Supplementary Fig. 1b). These events resulted in the prominence of state-level and federal-level agencies, including the NSW state government, the NSW Department of Environment, and the federal government, to initiate plans to fight pollution. The main governance measures covered the entire spectrum, including infrastructure, policy reforms, and economic measures (Connell and Grafton, 2011). Restrictions on water licenses and water extraction were implemented by the Murray–Darling Basin Commission in 1993, followed by the Water Reform Package initiated by the Council of Australian Governments in 1994.

The acceleration stage (1995–2017) saw an increasing recognition of the water needs of the environment. The societal value of water resources shifted to a new dominant culture based on respect and care for nature. The central roles within the governance network shifted from local agencies to state and federal agencies to enable key reforms: the Water Act 2007, which for the first time recognized the environment as a legitimate user of water in its own right (Mckay, 2005). The Act also created an independent Murray–Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) and called for a transfer of constitutional power from states to the commonwealth government to enable basin-wide reforms (Connell and Grafton, 2011). It began to set sustainable diversion limits on water that can be taken from the Murray–Darling Basin. It also introduced an environmental water plan to optimize environmental outcomes. This period was profound in Australian water management history. The reform of management policy and practice resulted from a shift in societal value, concurrent ecological changes, and a change in governance regime.

In the Chinese case, with a smaller number of actors, the network was denser (network density 0.005) and had a lower degree of centrality (see Fig. 6). The predevelopment stage (1946–1990) started with exploiting water resources to support food security, economic development, and industrialization (see Supplementary Fig. 2a). Dominated by the value of economic development, policy, and management were established to support water sector development, i.e., the theme of ‘water engineering and construction’ was reported for river regulations. The Yellow River Committee and the Ministry of Water Resources were the top two agencies that managed water during this period (Fig. 6). Driven by strong socioeconomic objectives, environmental objectives were typically compromised during this period.

Societal value in the take-off stage (1990–2005) was still driven by a desire for economic development, with the central government emphasizing that water resource development was the priority, putting it in an important strategic position. Increased investment in infrastructure development was proposed to fight low efficiency and cater to the need for irrigation. The take-off of economic development was accompanied by the impact of natural hazards and environmental deterioration caused by anthropogenic activities. Notably, in 1998, the third-largest basin-wide flood in the twentieth century occurred in the Yangtze River, and as a result, the river broke the main levee (Qian, 1998). The State Flood Control and Drought Relief Bureau was the leading actor during this period fighting this hazard (see Fig. 6). The significant flood directly resulted in decisions to harness major rivers to increase flood control capability and resource reallocation to mobilize the whole society’s resources. The construction of mega-projects commenced, such as the Three Gorges Dam Project and the South-to-North Water Diversion Project, later in 2003. At the same time, the deterioration of the environment resulting from overexploitation for urban and industrial development had become more evident. For example, the Yellow River dried up in 1997, and these events in which rivers dried up were more serious in the inland rivers in Northwest China, resulting in severe ecological disasters.

Therefore, China’s view of the human–water relationship was undergoing a significant transformation (Fig. 6). The governance structure at this time was highly centralized and hierarchical. Although the Ministry of Water Resources was the most central actor in the management regime, the governance network at this time was often criticized because it was as though “nine dragons manage the water,” which is a common metaphor that points to the multiple government ministries and municipal authorities involved in water management. Figure 4c also shows that the management of water issues was conducted between numerous ministries, including the Ministry of Environment Protection, the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry of Forest, and state flood control and drought relief. In the acceleration stage (2005–2017), government restructuring was implemented in 2008 to resolve the “nine dragons manage the water” problem by putting the Ministry of Water Resources as the “dragon head” and involving a diverse range of stakeholder groups to enable water resource management across broader demographic, resource and environmental systems (Haggart et al., 2021). Following the completion of a series of large-scale infrastructure projects in the mainstreams of China’s major rivers, major water issues remain unsolved. Water pollution has been extended in terms of its magnitude and spatial scale. One symptomatic event of the deterioration of water quality and the ecological system was the blue algae that broke out in Tai Lake in 2007, which severely impacted the drinking water supply of millions of people in Jiangsu Province but, more importantly, resulted in the awakening of environmental protection. A strict water resource management strategy was developed as the definitive solution to address China’s water issues. The critical aspect in which the strategy unfolds was the transformation from prioritizing development to water saving and protection and from supply management to demand management.

Discussion

The transition of a country or a whole society to sustainability is a long-term process that involves the society’s willingness to carry out such a transition and the governance system’s structural arrangement to support it. In both cases, a more centralized governance network during the take-off stage was found to be associated with the sustainability transition process. When comparing the transition path of the two cases, it was found that the take-off stage in China was much shorter than that in Australia. On the one hand, the take-off stage in China was a highly intense period. The current problems related to water resources, such as floods, shortages, water and soil erosion, ecological harm, and pollution, were made worse due to rapid economic growth. Therefore, at the time when China was still on the path to pursuing economic goals by increasing investments in infrastructure construction, environmental issues were too severe to ignore.

In Australia, no additional storage was built after the 1980s, and no new water licenses were granted for the Murray–Darling Basin after 1986. The Murray–Darling Basin Commission also implemented a permanent cap on water extraction expansion in 1997. The water reform package introduced by the Council of Australian Governments in 1994 marked Australia’s successful shift to a market-based approach to water policy and management mechanisms. Water titles were separated from land to establish a water market that enabled water trading. China benefited from these new concepts at an early transition stage, the water rights theory was introduced, and a national water rights framework was developed. Therefore, the transition in China was multipipeline, where both economic development and the shift to sustainability ran in parallel.

The second aspect that contributed to the fast transition in societal value in China was the centralized water governance structure, characterized by a governance network almost entirely monopolized by ministry-level governments and in which the whole network was highly centralized and densified around the most central actor: the Ministry of Water Resources. This situation seems contrary to what has long been emphasized: the dominant paradigm of centralized and hierarchical water governance must be better suited for a societal transition to sustainability (Chaffin et al., 2016). The approaches developed in natural resource governance have all emphasized that the management structure matters in a shift from state-centered government to less formalized governance (Mostert et al., 2007; Huitema and Meijerink, 2014; Rhodes, 1997; Termeer, 2009; Fliervoet et al., 2016). Typical hierarchical modes managed primarily through formal institutions have failed to manage common pool resources sustainably (Costanza et al., 1998; Gutiérrez et al., 2011; Ostrom, 2007). Instead, a decentralized model that allows the participation of wider stakeholder groups with a broader distribution of decision-making power (Armitage et al., 2010) is better suited to a sustainability transition (White et al., 2019). Lack of diversity within the network is often thought to inadvertently maintain the status quo within governance networks, decreasing the innovation potential that comes with increased knowledge sharing and experimentation and decreasing the adaptive capacity within the governance network (Stein et al., 2011). Furthermore, the high centrality of individuals was seen as leading to increasingly centralized decision-making, which negatively affects learning, as it reduces the access of individual actors to multiple sources of information (Bodin et al., 2006). However, our results illustrated that this dense, highly centralized network is advantageous in a transition when effective coordination of actors and resources is needed (Stein et al., 2011). This is also seen in the Australian network, where centrality reaches its maximal level in the take-off stage, with the federal government and state governments coming to occupy the central position of the network over the years. The federal government then called for the states included in the Murray–Darling Basin to transfer their constitutional powers over water management to the commonwealth so that comprehensive basin-wide reforms could be introduced. From the governance mode perspective, the findings align with the hypothesis of Pahl-Wostl et al., (2010) that hybrid governance systems that allow interplay between different governance systems are critical to ensure effective management for desirable outcomes. Additionally, these findings align with Gleick (2018): the system can benefit from combining bottom-up and top-down strategies to overcome institutional inertia and enable a transition to be successful.

Conclusion

This study took China and Australia as two case studies with different socioecological contexts to reveal how the transition in societal value and governance networks interactively co-evolved and if any common patterns were shared. The scope of analysis includes the oldest published newspaper from each country as a proxy to measure the societal value of water resource management and the governance actors, both formal and informal groups, involved in everyday water events.

In conclusion, our study revealed that the transition in societal value in Australia and China have gone through similar patterns, following the sigmoid function, i.e., an S curve. Both countries experienced the transition from economic development-oriented societal value to environmental sustainability-oriented societal value. In both cases, the transition curves do not show a clear inflection point to indicate the stabilization stage. According to transition theory, a transition may stabilize, experience a backlash, or even lead to system breakdown, and more data and a more extended study period in future studies are needed to confirm the future trend. The structural position of multiple actors and the characteristics of the whole governance network is critical in enabling a transition. While a less centralized governance network with the diversified involvement of multiple water actors is essential for developing sustainable management, the transition process can also benefit from a centralized network with a high centrality of federal- and ministry-level government bodies. Water is a focal resource for the development and sustainability of society. This study contributes by providing an empirical understanding of the dynamic mechanism of the governance system and societal value transition.

Meanwhile, it can also serve as a reference for policy-makers and water practitioners to understand how and in what contexts governance network configurations can effectively anticipate or adapt to desired transitions. As the limitations of this study, it should be noted that only one newspaper was chosen for each country due to the availability of continuously published and digitally accessible newspapers. A sampling method was also adopted to sample four weeks out of each year, as a large amount of data exceeded the capacity to perform manual coding. Therefore, the weeks that were sampled may not fully represent the societal values in each country, and some minor water governance events might have been missed. Future studies can further expand the scope of analysis to include more newspapers ranging from national and regional to community newspapers.

Data availability

The original dataset containing information on Australian and China water news events is attached as supplementary files. Additionally, the dataset “Replication data for a transition of societal value and governance on water resources in Australia over 1843–2017” is available in the Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WX7CHH, and the dataset “ Replication Data for a transition of societal value and governance on water resources in China over 1946–2017” is available in the Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KJM7B0.

References

Armitage D, Berkes F, Doubleday N (2010) Adaptive co-management: collaboration, learning, and multi-level governance. UBC Press

Avelino F, Wittmayer JM (2016) Shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: a multi-actor perspective. J Environ Policy Plan 18(5):628–649

Bennett NJ, Dearden P (2014) Why local people do not support conservation: community perceptions of marine protected area livelihood impacts, governance and management in Thailand. Mar policy 44:107–116

Berkes F (2009) Evolution of co-management: role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. J Environ Manag 90(5):1692–1702

Bodin Ö, Crona B, Ernstson H (2006) Social networks in natural resource management: what is there to learn from a structural perspective? Ecol Soc 11(2):r2

Borgatti SP, Everett MG, Freeman LC (2002) Ucinet for Windows: Software for social network analysis, vol 6. Analytic Technologies, Harvard, MA, pp. 12–15

Borgatti SP, Mehra A, Brass DJ et al. (2009) Network analysis in the social sciences. Science 323(5916):892–895

Caldas MM, Sanderson MR, Mather M et al. (2015) Opinion: endogenizing culture in sustainability science research and policy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112(27):8157–8159

Carlsson L, Berkes F (2005) Co-management: concepts and methodological implications. J Environ Manag 75(1):65–76

Chaffin B, Garmestani AS, Gosnell H et al. (2016) Institutional networks and adaptive water governance in the Klamath River Basin, USA. Environ Sci Policy 57:112–121

Connell D, Grafton RQ (2011) Water reform in the Murray-Darling Basin. Water Resour Res 47(12)

Costanza R, Andrade F, Antunes P et al. (1998) Principles for sustainable governance of the oceans. Science 281(5374):198–199

De Haan FJ, Rotmans J (2018) A proposed theoretical framework for actors in transformative change. Technol Forecast Soc Change 128:275–286

Domènech L, Saurí D (2010) Socio-technical transitions in water scarcity contexts: public acceptance of greywater reuse technologies in the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona. Resour Conserv Recycl 55(1):53–62

Farla J, Markard J, Raven R et al. (2012) Sustainability transitions in the making: a closer look at actors, strategies and resources. Technol Forecast Soc Change 79(6):991–998

Fischer LB, Newig J (2016) Importance of actors and agency in sustainability transitions: a systematic exploration of the literature. Sustainability 8(5):476

Fliervoet J, Geerling G, Mostert E et al. (2016) Analyzing collaborative governance through social network analysis: a case study of river management along the Waal River in The Netherlands. Environ Manag 57:355–367

Freeman LC (1978) Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc Netw 1:215–239

Geels FW (2010) Ontologies, socio-technical transitions (to sustainability), and the multi-level perspective. Res Policy 39(4):495–510

Geels FW (2011) The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms. Environ Innov Soc Transit 1(1):24–40

Geels FW, Schot J (2007) Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res Policy 36(3):399–417

Gleick PH (2018) Transitions to freshwater sustainability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115(36):8863–8871

Grin J, Rotmans J, Schot J (2010) Transitions to sustainable development: new directions in the study of long term transformative change. Routledge

Gutiérrez NL, Hilborn R, Defeo O (2011) Leadership, social capital and incentives promote successful fisheries. Nature 470(7334):386–389

Haggart B, Tusikov N, Scholte JA (2021) Power and authority in internet governance: return of the state? Routledge

Hale BW (2010) Using newspaper coverage analysis to evaluate public perception of management in river–floodplain systems. Environ Manag 45(5):1155–1163

Hartley TW (2006) Public perception and participation in water reuse. Desalination 187(1-3):115–126

Hayes AF, Krippendorff K (2007) Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Commun Methods Meas 1(1):77–89

Heberlein TA (2012) Navigating environmental attitudes. Oxford University Press

Huitema D, Meijerink S (2014) The politics of river basin organisations: institutional design choices, coalitions, and consequences. The Politics of River Basin Organisations, Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 1–37

Hurlimann A, Dolnicar S (2012) Newspaper coverage of water issues in Australia. Water Res 46(19):6497–6507

Itaoka K, Saito A, Akai M (2005) Public acceptance of CO2 capture and storage technology: a survey of public opinion to explore influential factors. In: Rubin ES, Keith DW, Gilboy CF, Wilson M, Morris T, Gale J, et al., editors. Greenhouse gas control technologies, vol 7. Elsevier, pp. 1011–1019

Johannessen Å, Gerger Swartling Å, Wamsler C et al. (2019) Transforming urban water governance through social (triple-loop) learning. Environ Policy Gov 29(2):144–154

Knoke D, Yang S (2019) Social network analysis, SAGE Publications, Incorporated

Larson KL, White DD, Gober P et al. (2009) Divergent perspectives on water resource sustainability in a public–policy–science context. Environ Sci Policy 12(7):1012–1023

Loorbach D, Frantzeskaki N, Avelino F (2017) Sustainability transitions research: transforming science and practice for societal change. Annu Rev Environ Resour 42:599–626

Mckay J (2005) Water institutional reforms in Australia. Water Policy 7(1):35–52

Mora C, Myers RA, Coll M et al. (2009) Management effectiveness of the world’s marine fisheries. PLoS Biol 7(6):e1000131

Mostert E, Pahl-Wostl C, Rees Y et al. (2007) Social learning in European river-basin management: barriers and fostering mechanisms from 10 river basins. Ecol Soc 12(1):19

Nielsen JR, Mathiesen C (2003) Important factors influencing rule compliance in fisheries lessons from Denmark. Mar Policy 27(5):409–416

Ostrom E (2007) A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104(39):15181–15187

Pahl-Wostl C (2019) The role of governance modes and meta-governance in the transformation towards sustainable water governance. Environ Sci Policy 91:6–16

Pahl-Wostl C, Holtz G, Kastens B et al. (2010) Analyzing complex water governance regimes: the management and transition framework. Environ Sci Policy 13(7):571–581

Poindexter PM, Mccombs ME (1999) Research in mass communication: a practical guide. Macmillan

Qian Z (1998) Viewpoints on the flood of the Yangtze River in 1998. Sci Technol Rev 12:9–11

Rathwell KJ, Peterson GD (2012) Connecting social networks with ecosystem services for watershed governance: a social-ecological network perspective highlights the critical role of bridging organizations. Ecol Soc 17(2):24

Rhodes RA (1997) Understanding governance: Policy networks, governance, reflexivity and accountability. Open University

Rivera A, Unibazo J, Leon P et al. (2017) Stakeholder perceptions of enhancement opportunities in the Chilean small and medium scale mussel aquaculture industry. Aquaculture 479:423–431

Rotmans J (2005) Societal innovation: between dream and reality lies complexity. DRIFT Research Working Paper

Rotmans J, Loorbach D (2009) Complexity and transition management. J Ind Ecol 13(2):184–196

Roznowski JL (2003) A content analysis of mass media stories surrounding the consumer privacy issue 1990–2001. J Interact Mark 17(2):52–69

Sayles JS, Baggio JA (2017) Who collaborates and why: assessment and diagnostic of governance network integration for salmon restoration in Puget Sound, USA. J Environ Manag 186:64–78

Schiffer E, Hartwich F, Monge M (2010) Who has influence in multistakeholder governance systems. Using the net-map method to analyze social networking in watershed management in Ghana. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Scott J (2011) Social network analysis: developments, advances, and prospects. Soc Netw Anal Min 1:21–26

Stein C, Ernstson H, Barron J (2011) A social network approach to analyzing water governance: the case of the Mkindo catchment, Tanzania. Phys Chem Earth Pt A/B/C 36(14-15):1085–1092

Stein C, Pahl-Wostl C, Barron J (2018) Towards a relational understanding of the water–energy–food nexus: an analysis of embeddedness and governance in the Upper Blue Nile region of Ethiopia. Environ Sci Policy 90:173–182

Termeer CJ (2009) Barriers to new modes of horizontal governance: a sense-making perspective. Public Manag Rev 11(3):299–316

Turner RA, Fitzsimmons C, Forster J et al. (2014) Measuring good governance for complex ecosystems: perceptions of coral reef-dependent communities in the Caribbean. Global Environ Change 29:105–117

Underdal A (2010) Complexity and challenges of long-term environmental governance. Global Environ Change 20(3):386–393

Vignola R, Mcdaniels TL, Scholz RW (2013) Governance structures for ecosystem-based adaptation: using policy-network analysis to identify key organizations for bridging information across scales and policy areas. Environ Sci Policy 31:71–84

Voss JP, Bauknecht D, Kemp R (2006) Reflexive governance for sustainable development. Edward Elgar Publishing, UK

Wasserman S, Faust K (1994) Social network analysis: Methods and applications. Cambridge University Press

Webb EL, Maliao RJ, Siar SV (2004) Using local user perceptions to evaluate outcomes of protected area management in the Sagay Marine Reserve, Philippines. Environ Conserv 31(2):138–148

Wei J, Wei Y, Western A (2017) Evolution of the societal value of water resources for economic development versus environmental sustainability in Australia from 1843 to 2011. Global Environ Change 42:82–92

Wei J, Wei Y, Western A et al. (2015) Evolution of newspaper coverage of water issues in Australia during 1843–2011. Ambio 44:319–331

White DD, Rauh EK, Sullivan A et al. (2019) Public attitudes toward urban water sustainability transitions: a multi-city survey in the western United States. Sustain Sci 14:1469–1483

Wittmayer JM, Avelino F, Van Steenbergen F et al. (2017) Actor roles in transition: Insights from sociological perspectives. Environ Innov Soc Transit 24:45–56

Xiong Y, Wei Y, Zhang Z et al. (2016) Evolution of China’s water issues as framed in Chinese mainstream newspaper. Ambio 45:241–253

Young OR, Guttman D, Qi Y et al. (2015) Institutionalized governance processes: Comparing environmental problem solving in China and the United States. Global Environ Change 31:163–173

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant No. 92047301).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JW, YW, and FT designed the study. JW collected Australian newspaper data, and YX collected Chinese newspaper data. JW, HH, and FT wrote the code and conducted the analysis. JW, YW, and FT wrote the manuscript with contributions from YX and HH.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The authors confirm that all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines. No human research participants were involved in this study.

Informed consent

The authors declare that this article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, J., Wei, Y., Tian, F. et al. Transition in the societal value and governance of water resources in Australia and China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 359 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01857-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01857-x