Abstract

In today’s modern world, students must be equipped with twenty-first century skills, particularly those related to solving real-life problems, to ensure competitiveness in the current global economy. The present study employed project-based learning (PBL) as an instructional tool for teaching math at the primary level. A convergent mixed-methods approach was adopted to determine whether the PBL approach has improved students’ twenty-first century skills, including collaborative, problem-solving, and critical thinking skills. Thirty-five students of the experimental group were treated with PBL, while 35 students of the control were treated with the traditional teaching method. ANCOVA test for “critical thinking skills” showed a significant difference between the experimental and control group (F = 104.833, p = 0.000 < 0.05). For collaborative skills, results also showed a significant difference between the two groups (F = 32.335, p = 0.000 < 0.05). For problem-solving skills, the mean value of experimental (25.54) and control group (16.94) showed a high difference after the intervention. The t-value (8.284) and the p value (p = 0.000) also showed a highly significant difference. Observations of the classroom also revealed the favorable effects of employing PBL. PBL activities boosted the level of collaboration and problem-solving skills among students. Students could advance their collaboration abilities, including promoting one another’s viewpoints, speaking out when necessary, listening to one another, and participating in thoughtful discussions. During the PBL project, students’ active participation and effective collaboration were observed, significantly contributing to its success.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Learners of the twenty-first century need to equip with the core knowledge and necessary skills to perform in various situations to succeed. There are many different educational philosophies, each of which contains essential elements for human development (Parrado-Martínez and Sánchez-Andjar 2020). In 2017, Alif Ailaan published a report entitled “Powering Pakistan for the 21st -Century,” highlighting the dismal state of math and science education nationwide. Report data showed that, on average, fourth graders earned 433 out of 1000 points in math on the National Education Assessment System exam. The survey concluded that students performed exceptionally poorly in mathematics and geometry (Ailaan 2017). Most students in public schools are not actively involved in their education because of the teacher-centered nature of the classroom. In teachers’ eyes, students’ knowledge, passions, and individuality are irrelevant (Rehman et al. 2021).

The National Education Policy of 2009 states that teachers should adapt their teaching methods according to the need of the students and situation. The National Curriculum for 2006 also emphasizes a significant shift in the teacher’s role, from information transmitter to classroom environment maker, to assist students in gaining a sound knowledge of mathematical topics. Several factors affect how effectively the math curriculum is put into practice. These factors include the school setting, student demographics, and instructional resources (Mazana et al. 2018). Teachers must adopt cutting-edge practices to ensure their students are well-equipped for the twenty-first century. Using ICT, these novel methods may assist teachers in honing these abilities and adapting instruction to meet the moment’s needs (Muthukrishnan et al. 2022).

PBL and twenty-first century skills

In the twenty-first century, cognitive abilities are an unquestionably reliable measure of a student’s success (Saduakassova et al. 2023). Students of this generation need to be aware of how the world is changing and prepare themselves with the skills necessary for a more challenging way of life (Wongdaeng and Hajihama 2018). Students need to be able to engage in critical thinking to survive in this competitive era. It will enable them to take the initiative and devise meaningful solutions to emerging problems (Suwastini et al. 2021). Students need to have strong communication skills and the ability to work effectively with others to succeed in today’s world when networking is essential to one’s career (Akcanca 2020). Students must have an imaginative and creative mindset to keep up with the rapid advances. The terms “communication”, “cooperation”, “creativity”, “problem-solving skill”, and “innovation skills” are often referred to as “the 4Cs” that PBL supports; in the present study, the author only focused on the three skills, collaborative, critical thinking and problem-solving that has more influence in math learning (Almazroui 2023, pp. 125–136).

Educational professionals have recognized the importance of the 4Cs to student success. They have proposed that PBL as an instructional design can improve students’ mastery of the 4Cs (Kurniahtunnisa and Wowor 2023). According to Moghaddas and Khoshsaligheh (2019), PBL is a teaching strategy that falls under the constructivist approach and centers on having students participate in a series of research-oriented activities that require their collaborative actions to achieve the goal. By participating in these activities and interacting with others, students’ critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and creative abilities can be enhanced (Papanastasiou et al. 2019).

There are several problems with Pakistan’s educational system, including a lack of funds, inefficient program execution, and poor management and instruction (Shah Bukhari et al. 2022). As a result, most of our educational institutions continue employing more conventional instruction modes. Math is the most powerful tool for acquiring knowledge that exists in the world (Sithole et al. 2017). Math is the discipline in the scientific world that focuses on developing individuals’ perceptual and cognitive abilities. History shows that every ancient civilization placed a high value on mastering arithmetic. History also shows that every ancient civilization greatly valued becoming proficient in arithmetic (Alsaad et al. 2023). Students who are not good at math struggle academically due to their lack of enthusiasm for studying the subject since they either do not find it interesting or challenging. Children lose interest in understanding complex concepts such as algebra, arithmetic, or geometry at a young age when teachers force them to learn without focusing on the twenty-first century skills (Abramovich et al. 2019). The present study investigates the impact of PBL on students’ twenty-first century skills, including problem-solving, critical thinking, and collaborative skills.

Reasons for implementing project-based learning in math

One of the main reasons for implementing PBL in math is to address the low math scores of Pakistani students, as reported by TIMSS 2019 and Alif Ailaan reports (2017). Finland has improved its ranking in PISA by implementing PBL in its education system, which has helped to promote student-centered learning, collaboration, and problem-solving skills and to develop a deep understanding of the subjects studied, resulting in improved academic performance. PBL can help students to develop a deeper understanding of mathematical concepts and skills through hands-on, real-world problem-solving activities. For technology-deprived classrooms, PBL effectively engages students in active learning experiences, such as group projects and case studies. Technology integration is impossible in many public schools due to a lack of access to basic infrastructure such as electricity and internet connectivity. Implementing PBL in math can promote student motivation, collaboration, and creativity, essential for developing twenty-first century skills and preparing students for future careers. PBL can shift the focus from teacher-centered instruction to student-centered learning, allowing students to take ownership of their learning and develop critical thinking skills.

Research question

Q1. Is there any statistically significant difference in the students’ collaborative skills between the experimental and the control group?

Q2. Is there any statistically significant difference in the students’ problem-solving skills between the experimental and the control group?

Q3. Is there any statistically significant difference in the students’ critical thinking skills between the experimental and the control group?

Q4. How do students collaborate with group members during classroom project learning?

Literature review

PBL and collaborative skills

Collaborative learning (CL) is a fundamental component of the twenty-first century skills. It involves students collaborating to exchange ideas, solve an issue, or achieve a common objective (O’Grady-Jones and Grant 2023). In math education, CL’s popularity skyrocketed in the 1980s, but it has continued to develop since then (Simon 2020). The educational strategy known as collaborative learning tries to improve students’ education by having them work on projects together in groups (Vogel et al. 2016). This method encourages students to construct their meaning from various sources of knowledge rather than relying solely on memorizing facts and figures. To complete a wide range of class projects and assignments, students work together in small groups to better grasp complex ideas and concepts (Roldán Roa et al. 2020). Primary factors determining the efficacy of collaborative work are students’ level of involvement in the learning process and teachers’ readiness to evaluate project outputs (Kaendler et al. 2015).

In PBL, students are encouraged to work in groups of two or more pairs or classes to discover common ground, develop ideas, define concepts, or generate an end product (Rizkiyah et al. 2020). Students attentively follow the teacher’s instructions and diligently interpret and apply their understanding of the course material, demonstrating their grasp through study and application (Qureshi et al. 2021). The usage of CL has brought about a profound shift away from the old classroom atmosphere centered on the teacher delivering lectures. The ways of taking notes, listening to a lecture, and simply observing may only partially disappear in a classroom setting, emphasizing collaboration. However, they coexist with other strategies for promoting active learning and student conversation regarding the course content (Kollar et al. 2014). Teachers who employ interactive teaching methods perceive themselves not merely as transmitters of expert knowledge to students but, more significantly, as mentors or coaches facilitating a mature learning process. They see their role as expert designers of the cognitive experiences their students engagement. This shift in perspective allows them to engage students better in the learning process (Lim et al. 2023).

Recent research has shown that both meaning and behavior influence the process of learning. During collaborative learning activities, the students are encouraged to overcome challenging obstacles. Immersive learning activities often begin with topics in which students must supply particular facts and perspectives (Almazroui 2023). Contrarily, traditional classrooms typically initiate by providing information and concepts before transitioning into a practical application (Markula and Aksela 2022). In this setting, teachers expect students to quickly evolve from their roles as preliminary researchers, dealing with questions and answers or problems and solutions, to becoming competent experts. It requires them to employ higher-order thinking and problem-solving strategies (Brown et al. 1989). Despite the term “collaborative learning” being widely applied across various fields and disciplines, it still needs universal approval. Though many may still need to grasp the concept fully, certain commonalities tend to emerge (Qureshi et al. 2021). In the twenty-first century, there was a rise in working together. Because the focus has shifted from individual actions to group efforts and from the individual to society, it is more vital than ever for people to think about and collaborate on significant issues (Laal et al. 2012).

PBL and problem-solving skills

Project-based learning is an approach to education in which students demonstrate mastery of a topic by developing and presenting their solutions to real-world problems (Chiang and Lee 2016). In the planning stage, students must evaluate the needs for product development, identify issues with current products, and modify these products based on the principle of creative problem-solving. PBL can benefit students’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, and creativity in problem-solving capacities (Andanawarih et al. 2019). However, unlike conventional teaching methods, project-based education can be challenging to put into practice. Tee (2018) stated that students must communicate effectively to ensure the success of project-based learning projects. The students struggled through the project planning phase to apply the concept of creative problem-solving, which is essential when building a product (Artama et al. 2023). Therefore, educators are encouraged to craft a guide for innovative problem-solving by harnessing student-generated product concepts. However, the current student knowledge and abilities level can challenge the effective implementation of project-based learning (DeCoito and Briona 2023). Students are to fault for this since they need more practice solving problems or participating in project-based learning. The students’ incapacity to apply strategies for overcoming creative obstacles while learning contributes to the low quality of their work (Kiong et al. 2022). Therefore, it is essential to emphasize the use of creative problem-solving strategies in PBL to provide students with the means to finish the projects associated with each chapter with relative ease and better prepare them for higher education (Devanda and Elizar 2023).

PBL and critical thinking skills

In addition to content knowledge, PBL fosters skills like critical thinking, creativity, lifetime learning, communication, teamwork, flexibility, and self-evaluation (Artama et al. 2023). Creating science and mathematics curricula aims to train students to think more critically. Analytical and critical thinking is examining data, making inferences, articulating ideas, and assessing claims. However, the student’s critical thinking skills are still formative (Mutakinati et al. 2018). For this reason, schools must implement programs that help students develop their abilities in areas like creativity and critical thinking, which are in high demand in the modern workplace. Project-based learning is an effective method of teaching and learning in the contemporary era. This approach in the education sector offers equal treatment of real-world issues. At the outset of each lecture, students examine problems from the real world, which are then recast as problems for them to solve in pairs or small groups (Pan et al. 2023).

Critical thinking is an essential life skill. Future success requires students to have strong communication and critical thinking skills. Critical thinking is analyzing and evaluating one’s thinking to make constructive changes. Nadeak and Naibaho (2020) identified six levels of critical thinking: unreflective thinker, challenged thinker, novice, practicing thinker, advanced practitioner, and master. When we talk about “critical thinking”, we are talking about the ability to analyze information, evaluate its relevance, and comprehend problems. Analyzing, evaluating, reasoning, and reflecting are part of the process (Rati et al. 2017).

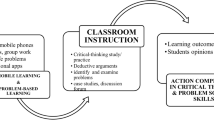

The Paul–Elder Framework for critical thinking defines critical thinking as a self-reflective and disciplined process involving constant self-monitoring and correction. This framework encourages an analytical approach to personal thought processes to enhance them. The unreflective thinker, the challenged thinker, the novice thinker, the experienced thinker, the expert thinker, and the master thinker are the six stages of critical thinking (Paul and Elder 2008). According to Paul and Elder (2008), there are eight parts to a thinking process: an objective, a set of questions, a body of data, a set of interpretations and interferences, a set of ideas, a set of assumptions, some potential outcomes, and a point of view (Fig. 1). The intellectual standards outline the criteria for good critical thinking (Mutakinati et al. 2018).

The author made this figure based on the framework provided by Paul and Elder (2008).

Math education incorporates many skills, including self-awareness, the ability to plan and organize learning, and the capacity to think critically. The assessment of students determines the accuracy, credibility, and relevance (or applicability) of the provided materials. Critical thinking and mathematics are deeply intertwined; one must integrate both to understand the discipline truly. Every child must learn and practice arithmetic and logic. Therefore, any program that teaches critical thinking should incorporate strategies that cater to diverse student populations (Holmes and Hwang 2016).

Previous studies on PBL

PBL has gained recognition worldwide as an alternative approach to traditional teacher-centered education, emphasizing hands-on, collaborative, and inquiry-based learning activities (Yang et al. 2021). Previous studies have shown that PBL can effectively promote student learning, engagement, and achievement across various subjects, including math and science. For example, a study by Paryanto et al. (2023) found that PBL improved student achievement and attitudes toward learning in engineering education.

However, some studies have also criticized the effectiveness of PBL in specific contexts, highlighting the challenges of implementing PBL and potential limitations. For instance, a study by Loyens et al. (2023) found that PBL had a limited impact on students’ cognitive and metacognitive skills in medical education. The authors suggested that the lack of clear guidelines and support for PBL implementation and the complex and dynamic nature of medical education may have contributed to these results (Saqr and López-Pernas 2023). Furthermore, some researchers have argued that the effectiveness of PBL may depend on various factors, such as the level of student readiness, teacher training and support, curriculum alignment, and assessment methods. For example, a study by Jincheng and Chayanuvat (2020) found that PBL is more effective when integrated into a comprehensive curriculum reform program than used as a stand-alone intervention. Additionally, the authors emphasized the importance of aligning PBL with clear learning objectives, providing appropriate scaffolding and support, and using valid and reliable assessments to measure student learning (Szalay et al. 2023). While PBL has shown promise as a practical approach to teaching and learning, its implementation and effectiveness may depend on various factors, and caution should be exercised in its application (Jincheng and Chayanuvat 2020).

Constructivist theory

The social constructivist approach is consistent with project-based learning since it stresses students’ involvement in the learning process through group work and instructor guidance (Huang et al. 2022). Therefore, educators should foster classroom environments where students can take charge of their learning. Students in project-based learning classes are encouraged to participate actively in their education and develop critical transferable skills while working on real-world projects (Le et al. 2023). Interpersonal learning occurs when individuals participate in groups, share information, and work together to overcome obstacles (Dolmans 2019). Students develop essential life skills in groups where they take full responsibility for their education (Harden 2018). Students’ ability to think creatively and fill the gap between their knowledge and talents is aided by acquiring these new life skills. It highlights the significance of PBL, which brings transformative experiences, facilitates long-term knowledge retention, and nurtures students’ commitment to an inclusive and participatory society (Mielikäinen 2022).

In addition, the multiple intelligence theory developed by Howard Gardner fits well with the approach taken in project-based education (Owens and Hite 2022). Gardner highlighted that all humans possess eight types of intelligence, each manifested in a unique set of skills and abilities, and he discriminated between these types in the context of students. Due to these differences, teaching and learning styles vary. By incorporating a wide range of activities, project-based courses may effectively accommodate students with a wide range of learning preferences (Radkowitsch et al. 2022).

The experiential learning theory (ELT) developed by Kolb (1984) served as the theoretical foundation for PBL (Sevgül and Yavuzcan 2022). The ELT works well with the principles of PBL, and it proposes that young children have an innate interest in the scientific method and want to know how the things they meet in their everyday lives function. Sevgül and Yavuzcan (2022) argued that children are naturally curious and continually engaged in meaningful interactions with the world around them. They learn to think critically and solve difficulties by interacting with one another. Consultation with adults, peers, and educators promotes collaborative learning. Like experience, growth is a continuous process, with each step having its distinct logic and psychology that prime the learner for the next level (Rajabzadeh et al. 2022). The principles of PBL exemplify Kolb’s ELT due to their emphasis on fostering a learning environment that resonates with students and a real-world audience. Students must provide classroom activities that enable them to benefit from real-world applications and cultivate meaningful relationships with their peers. Students gain a sense of belonging to something greater than themselves when they work together toward a common objective (Sevgül and Yavuzcan 2022). The study focused on understanding how learning occurs in PBL, and Kolb’s ELT provided a framework for doing so based on meaningful and authentic experiences. Students can only engage in meaningful learning if they can build on their existing knowledge and participate in projects with personal and global significance (Erstad and Voogt 2018).

Methodology

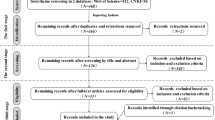

In the present study, the researcher adopted a convergent mixed-methods approach to determine if the problem-based learning (PBL) method has enhanced students’ twenty-first century skills, including collaboration, problem-solving, and critical thinking. A quasi-experimental design was used for the quantitative part, and a non-equivalent control group pre-test-post-test design was employed. This design remains prevalent in educational research (Cohen et al. 2017). For the qualitative part, students were observed during intervention using the collaborative framework to understand the students’ involvement during their project work. Students in 5th grade were selected as the object of the study, one section (35 students) was selected as an experimental, and others (35 students) were selected as a control group. The experimental group was treated with PBL intervention, while the control group was treated with the traditional teaching method. Random sampling was not possible due to fix schedule of the school. It was a 6-week project, and the detail of the PBL project is provided in Table 1. In the control group, teachers implemented the same content traditionally. Before and after the intervention, collaborative, critical thinking, and problem-solving were measured in both groups of students.

Instruments

The researcher adopted a collaborative scale Tibi (2015) developed to answer the research questions. This scale was used to evaluate the students in the control and experimental groups to see how well they could work together (see Table 2). The questionnaire consisted of 37 five-point Likert-style statements. To assess problem-solving skills math test was designed, which contains twenty items. To measure the students’ creative and critical skills, the researcher adopted Gelerstein et al. (2016), Yoon (2017), Sumarni and Kadarwati (2020) open-ended questionnaire. The study collected data using a critical thinking skills test comprising ten problems. These problems measured sub-skills, including interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, and self-regulation. Table 1 presents the instruments used for this critical thinking test.

Ventista (2018) also used this questionnaire in his study. The scale’s reliability was determined to be 0.76 using the Cronbach alpha test. In conclusion, higher-order cognitive skills emerged from metacognitive processes (Coskun 2018). This finding agreed with prior work published by Sumarni and Kadarwati (2020) on developing test items to gauge students’ creative abilities. The critical thinking instrument used in this research exhibited high validity and reliability, making it possible to assess students’ critical and creative thinking skills in the context of math.

The math test was designed to check how well students can solve problems. This test uses content from three chapters of a 5th-grade math teacher’s guide to see their improvement. The test consisted of 20 questions and aimed to gauge fifth-grade students’ problem-solving abilities in angle measurement and geometry. The test consists of ten questions related to each category. The first ten questions measured students’ problem-solving skills related to angle measurement, while the second set measured their geometry-related skills. Test questions are crafted carefully to assess the students’ understanding of these concepts and their ability to apply them to real-world scenarios. The test was administered to the students, and the results were analyzed to determine their proficiency in problem-solving skills related to these topics (see Table 2).

The study utilized the “ITEMAN” tool to perform item analysis on these data (Ramadhan et al. 2019, pp. 743–751). The results showed that the difficulty index might range from 0.33 to 0.85, and the discrimination index may range from 0.31 to 0.82. According to the findings of Susanto and Retnawati (2016), We considered an item to be of generally high quality if its difficulty index ranged from 0.31 to 0.89 and had a discrimination value of at least 0.22.

The classroom observations tool served as a source for gathering qualitative data. Before the observational activities, participants received information about the researcher’s intentions. The study utilized a collaborative framework tool to monitor students’ behavior and engagement in the experimental classroom. Before initiating data collection, the instrument underwent a validation process.

Stages of the experiment

-

(1)

Before the intervention, homogeneity of the 5th-grade math students was established. Both groups were randomly allocated as the 5-B experimental and 5-A as the control group. Before the intervention, we examined all the experimental and control variables, including collaborative, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills.

-

(2)

Before the intervention, twenty-first century skills were measured as a pre-test from both groups.

-

(3)

In the experimental group, PBL was used as an instructional tool for delivering math content. Different lesson plans and modules are prepared concerning the “Measurements of angels, geometry, and decimal concept”. A control group was treated with a traditional method with the same content (see Table 3).

-

(4)

Lesson schedule (6 weeks, 5 h weekly, for 30 class hours), lesson plans, and modules were designed before intervention. Lessons planning followed Math Core standards.

-

(5)

Before the intervention, AV aids were prepared for classroom activities. Students worked in the classroom in groups of six girls (five groups) in each session.

-

(6)

For assessment, teachers used worksheets and projects at the end of the session and followed the operational stages mentioned by “Buck Institute” Kaptan and Korkmaz (2000).

-

(7)

After the intervention, both groups implemented the “math attitude, creativity, and problem-solving test” as a post-test.

-

(8)

During the project work, experimental group students were observed to assess their engagement and collaboration with peers and groups.

PBL project implementation

A hands-on project

During this procedure, the students worked on creating a new product. They discuss and present an actual model.

For the present study, students constructed a project after 4 weeks of lessons and presented it at the end of the experiment. All group members participated and presented their work to the class (see Fig. 2).

Driving questions

During this procedure, students strive to provide a solution to an open-ended question. For the present study, the instructor prepares different open-ended questions for students to answer. The best part was that every member was participating. Every classroom consists of average, below-average, and high achievers. PBL encouraged every category student to get participated in project-making.

Q1. Identifying Right, Obtuse, and Acute Angles?

Q2. Name the marked angle.

(a) Name the vertex of the angle.

(b) Name the arms of the angle

Q3. Classify the following angles into acute, obtuse, right, and reflex angles:

(i) 35°(ii) 185°(iii) 90°(iv) 92°(v) 260°

Q4. Observe the given figure with a protractor and give the measure of each of the angles.

New information

As a result of participating in this process, students acquire new mathematical information. This task also helped students to review previously learned knowledge. For the present study, the teacher introduces the new concept with examples, like percentages, discounts, and real value.

Student-driven elements

The teacher performs indirectly as a facilitator while the students direct their learning. Throughout the lesson, the teacher acted as a facilitator, and it was the first time for students to learn math with different teaching strategies; so, at every step researcher and the trainer acted as a facilitator and provided a zone of proximal development (ZPD), throughout their learning process.

Realistic goals and outcomes

Students work on a realistic project, and it has some objectives. It is appropriate both for the age of the students and aligned with course standards. PBL is appropriate for primary-grade students; PBL helps them strengthen their foundation and make concepts more precise and practical.

Application to the real world

The mathematical concepts involved things that learners might encounter outside the classroom. All the essential elements are followed rigorously (see Table 4).

Results

The effect of PBL improving students’ collaborative skills

The study uses one-way ANCOVA for the pre-and post-test on the experimental and control groups to check the effectiveness of PBL in improving the 5th-grade students’ collaborative skills. Before proceeding to a one-way analysis of covariance, a homogeneity of variance test analysis is performed to ensure the data aligns with the fundamental premise of ANCOVA (see Table 5).

Levene’s test result, shown in Table 5, demonstrates no difference between the experimental and control groups before the intervention (F = 0.806, p = 0.0373 > 0.05). The data analysis aligns with the primary hypothesis of ANCOVA. That means that the two groups’ variations are identical to one another. Therefore, the two samples originate from populations with the same variance.

Table 6 represents a result of one-way ANCOVA for the students about collaborative skills. Results show a significant difference between the experimental and control groups (F = 253.564, p = 0.000 < 0.05). This indicates that PBL activities impact the fifth-grade students’ collaborative skills during project learning. Students in the intervention group developed collaborative skills during the math project compared to the control group students.

The effect of PBL improving students’ critical thinking skills

One-way, ANCOVA compares the pre-and post-test results of the “critical thinking skills” of the treatment and control groups for the fifth-grade math students. In determining whether the data are consistent with the fundamental premise of ANCOVA, a homogeneity of variance test analysis is performed before a one-way analysis of covariance (see Table 7).

Table 7 represents a result of Levene’s test, which revealed no significant difference between the two groups (F = 3.711, p = 0.58 > 0.05). The fundamental premise of ANCOVA applies once the data analysis is complete.

Table 8 represents the result of one-way ANCOVA for the students’ “critical thinking skills”. Results showed a significant difference between the treatment and control groups (F = 23.281, p = 0.000 < 0.05). The intervention group’s critical thinking skills improved compared to control group students. PBL helps the students to develop twenty-first century skills and involve them in critical thinking during their project learning.

The effect of PBL improving students’ problem-solving skills

Problem-solving skills

An accomplishment exam was developed to evaluate students’ problem-solving skills in math. This test required students to respond to 10 questions (20 marks) chosen and crafted according to the math curriculum’s standards-based learning objectives (SLO). Before and after the experiment, the test was given to students of both groups to know the difference.

Table 9 represents the mean scores of the experimental and control group students’ problem-solving test results. The mean value of the experimental group before the intervention was 12.46, and after the intervention was (25.54). While the pre-mean value of the control group was (11.80) and after was (16.94). The data reveals an increase in the mean value for both groups. However, the experimental group, which received instruction through the PBL method, exhibited a more substantial increase than the group taught math using the traditional method. The p value also shows that before the intervention, the p value was (p = 0.421), which is greater than 0.05, which means there was no significant difference between the experimental and control group. While after the intervention, the p value (p = 0.00) shows that there is a significant difference.

To check the difference in the mean scores between the control and experimental group before and after the experiment, an independent sample t-test was applied.

Table 10 represents the result of the independent sample t-test; the mean value of the experimental group (12.46) and the control group (11.80) shows a minor difference in both groups before the intervention. The t-value (0.809) and the p value (p = 4.22) also show no significant difference. The results of this table show that group of experimental group and control group performed the same on achievement and problem-solving skills before the intervention; there was no significant difference between experimental and control group students. The p value (p = 4.22) is more significant than 0.005. That specified no significant difference between the experimental and control groups before the treatment.

Table 11 represents the result of the independent sample t-test; the mean value of the experimental group (25.54) and the control group (16.94) show a high difference in both groups after intervention. The t-value (8.284) and the p value (p = 0.000) also show a highly significant difference. This table shows that the experimental group performed better on problem-solving skills than the control group, which was not treated with PBL. PBL as an instructional tool was suggested as one of the best teachings for teaching math at the primary level. Cohen’s d value of 1.82 specified a big difference between the group treated with the PBL instruction method and those treated through traditional teaching methodology.

Paired sample t-test was applied to check the difference between the pre-and post-scores of the experimental and control group.

Table 12 shows the results of paired sample t-test. Paired sample t-test is applied to the pre-post-test of the experimental and control group to know the difference before and after the intervention. The mean value of the scores showed that there were highly significantly different. As the p value is smaller than 0.05 (p = 0.005), the probability value is highly significant, and there is a difference in the mean scores of the experimental group. PBL helps the students develop more problem-solving skills than the control group. On the other hand, the mean value of the control group’s scores showed a minor difference, and the p value is more significant than 0.05, which means that the traditional method did not significantly affect the students’ problem-solving skills.

Qualitative analysis

All experimental group members were observed using a collaborative scale framework during project work. Students were observed under the project’s four themes: individual accountability, social skills, and group processing. This method is widely used in social sciences (Pleşan 2021). The instructor divided the students into seven groups (five girls in each group) with varying abilities and potential. The students were able to acquire various skills in these diverse groups to enhance them as well as intragroup interpersonal interactions. Classroom observations were conducted several times a week over 6 weeks. The study utilizes two inductive and deductive reasoning cycles during the coding process (Ridder 2014). Four themes were generated from the observational data: student group work, a student, shared duties, the interdependence of the student’s work and their decision-making

Students’ group work

During the PBL, students collaborated in groups from the project planning stage to creating the product and project presentation. Students collaborated in groups to discuss statistical applications in their classrooms throughout the project preparation stage. Then, they discuss further the project’s title, description, and objectives, the project’s implementation steps, the project schedule, and each group member’s responsibilities. Additionally, observations revealed that students leveraged social media platforms, such as WhatsApp group chats, for discussions outside school hours.

Students shared responsibilities

Each group assigned its members a task and set a deadline, ensuring students appropriately shared duties. Therefore, the students were expected to finish the related activities before the due date. When it was their chance to speak on what they had discovered about angles, how they are measured, and how these angles differ from one another, the students were sharing responsibility. This circumstance demonstrated that each group member must collaborate to develop their awareness of many aspects and apply them to their project. Additionally, each student took part in constructing the presentation of their work on hard copy paper and outlining the presentation materials for their project presentation in front of the entire class. The project tasks involved cutting paper, measuring angels, and sketching various shapes with various angles and were shared among the pupils to produce the final items.

Students shared responsibilities

The students made decisions regarding the theme of the project, the activities they would undertake, the project’s timeline, individual roles within the group, the final product, and the materials and tools required for the project. They also determined the most effective method to present their project results to others. When making substantial judgments about the project’s topic, process, and output, students always hold an initial conversation to address individual ideas collectively. To influence the choice, the students bargained their thoughts. The observation revealed that the student gained confidence in her ability to voice her opinions during the group assignment. When students encountered divergent viewpoints among group members regarding the process of making important decisions, they conducted voting and arrived at a consensus opinion.

Additionally, the researcher discovered that one student needed help developing the project’s product, particularly the finished item. The student expressed concern about the final product’s adornment, which she feared would be overdone and lower its esthetic worth. These data demonstrate that the student and her team were making crucial design decisions that impacted the result.

Students’ interdependent work

From the observations, it is clear that the task required each group member to create a unique set of presentation materials on angles, which were to be assembled into a cohesive presentation on stiff chart paper. Therefore, if any group member does not complete their tasks in time, it may cause a delay in the final presentation chart’s completion. This circumstance demonstrated the interdependence of the student’s contributions to the PBL. The researcher observed and documented students’ collaborative efforts in a project-based learning environment, and the following are excerpts from these observations. In addition, each group member was assigned to prepare and bring the tools and supplies required to complete the project. The manufacturing process is improved if one team member gets the necessary tools or materials. That demonstrated how student effort is interdependent and dramatically impacts the project. This requirement enables students to comprehend and be conscious of the significance of their part in completing the project. Students were able to apply the concept of an angel to everyday problems through the completion of their mathematics project. In this project, students worked in small groups to gather and describe the data using their knowledge and observations. Subsequently, they transformed the angles into visual representations. The student’s final projects, displayed in the counseling room, the students’ club room, and the school wall magazine, served as references for significant school statistics.

The findings above conclude that applying PBL in mathematics enhances students’ teamwork skills. When students share responsibility equitably, make crucial decisions, and produce an interdependent project product, they attain level 5 according to the criteria for twenty-first century students’ collaboration skills.

Conclusion

The present study’s findings contribute to the growing body of literature on PBL and its potential for promoting students’ twenty-first century skills, particularly in Math education. The results showed that students who received PBL instruction developed collaborative, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills, as measured by various assessment tools, including questionnaires, tests, and classroom observations. These skills are essential for preparing students for the complex challenges of the twenty-first century, such as global competition, technological advancements, and social and environmental issues. It aligns with previous research highlighting the benefits of PBL for promoting critical and creative thinking (Darling-Hammond et al. 2020). However, students in Pakistani government schools need to become more accustomed to engaging in critical thinking while solving arithmetic problems, as reported by the TIMSS study. That is a big challenge for teachers seeking to improve math and Science Education (Ahmad et al. 2022).

The study sheds light on implementing PBL activities in classrooms and how they can enhance students’ critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaborative abilities. This finding can help teachers reevaluate how students gain from participating in PBL activities and restructure their instructional approaches to achieve student-centered learning. The study’s results are consistent with previous research, suggesting that PBL can help students build collaborative skills through group projects (Chistyakov et al. 2023). Collaboration abilities are crucial for success in today’s interconnected working environment and global culture. PBL is one educational activity that can help students build these skills, as it demands that students collaborate in small groups to solve problems and produce products. PBL is an ideal method for teaching mathematics at the primary level. It helps students recognize the relationships between different mathematical concepts and develop a conceptual understanding of the subject. It can help students identify partial order in the collection of mathematical notions, an essential aspect of mathematical concept development.

However, it is essential to note that the effectiveness of PBL may depend on various factors, such as teacher training and support, curriculum alignment, assessment methods, and student readiness. For instance, Loyens et al. (2023) research revealed that PBL minimally influences students’ cognitive and metacognitive abilities within medical education. The researchers posited that the absence of well-defined guidelines and assistance for PBL implementation might have yielded these findings in conjunction with medical education’s intricate and ever-changing landscape. Furthermore, implementing PBL may require significant time, resources, and training for teachers and students, posing challenges in specific educational contexts. Therefore, further research is needed to explore the effectiveness and feasibility of PBL across different subjects, grade levels, and cultural contexts and identify the optimal conditions for its implementation.

In conclusion, this study provides empirical evidence of the potential benefits of PBL for promoting twenty-first century skills in math education, including collaboration, critical thinking, and problem-solving. The findings underscore the importance of student-centered, inquiry-based, and authentic learning experiences that can prepare students for the complex challenges of the twenty-first century. The study’s results inform the development of practical pedagogical approaches that promote student learning and engagement and contribute to the ongoing dialog on educational reform and innovation.

This study has a unique contribution to the context of the Pakistani educational landscape. While the literature is abundant with studies on the benefits of project-based learning (PBL), this study specifically addresses the implementation and effectiveness of PBL in teaching mathematics to 5th-grade students in Pakistan. By providing detailed insights into the local context, including the cultural, social, and educational factors that may influence the adoption and outcomes of PBL, we have enriched the understanding of PBL’s applicability and potential benefits in diverse settings. Furthermore, the interpretation of our results highlights the development of twenty-first century skills, collaborative abilities, problem-solving aptitude, and creative thinking skills among the participating students, demonstrating the value of PBL as an instructional tool within the Pakistani context. This original contribution advances the global understanding of PBL’s effectiveness. It offers practical implications for educators and policymakers in Pakistan seeking innovative ways to improve learning outcomes and foster essential skills in their students. Moreover, in Pakistani public schools where technology integration is not feasible, PBL can be an effective alternative for math teaching by utilizing low-tech resources such as manipulatives, posters, and group activities. Teachers can create engaging and collaborative problem-solving experiences for students, fostering critical thinking skills even in technology-deprived classrooms.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author. These data are part of a large project, and only a portion is available for the following reasons: (1) Some participants in the study requested complete anonymity, which restricts the availability of specific datasets to protect their privacy and confidentiality. We have taken all necessary steps to ensure no personal or identifiable information is included in the available data. (2) Additionally, some of the data are reserved for future publication. It ensures the integrity of ongoing analyses and prevents potential overlap in research findings. We understand the importance of data availability in promoting transparency, reproducibility, and open science, and we commit to making as much of the data available as possible within these constraints. Data are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YJY0FI and accessed with the author’s permission.

References

Abramovich S, Grinshpan AZ, Milligan DL (2019) Teaching mathematics through concept motivation and action learning. Educ Res Int 2019:1–13

Ahmad S, Rodrigues S, Muzaffar Bhutta S (2022) Pakistan’s first ever participation in international large-scale assessment (TIMSS): critique and implications. J Educ Educ Dev 9(2):191–210

Ailaan A (2017) Pakistan district education ranking 2017, vol 66. Alif Ailaan, Islamabad

Akcanca N (2020) 21st century skills: the predictive role of attitudes regarding STEM education and problem-based learning. Int J Progress Educ 16(5):443–458

Almazroui KM (2023) Project-based learning for 21st-century skills: an overview and case study of moral education in the UAE. Soc Stud 114(3):125–136

Alsaad AA, Mansor ZBD, Ghazali HB (2023) The effect of TQM practices on job satisfaction in higher education institutes. A systematic literature review from the last two decades. J Optim Ind Eng 16(1):75–87

Andanawarih M, Diana S, Amprasto A (2019) The implementation of authentic assessment through project-based learning to improve student’s problem solving ability and concept mastery of environmental pollution topic. J Phys Conf Ser 1157:022116

Artama KKJ, Budasi IG, Ratminingsih NM (2023) Promoting the 21st century skills using project-based learning. Lang Cir J Lang Lit 17(2):325–332

Brown JS, Collins A, Duguid P (1989) Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educ Res 18(1):32–42

Chiang CL, Lee H (2016) The effect of project-based learning on learning motivation and problem-solving ability of vocational high school students. Int J Inf Educ Technol 6(9):709–712

Chistyakov AA, Zhdanov SP, Avdeeva EL, Dyadichenko EA, Kunitsyna ML, Yagudina RI (2023) Exploring the characteristics and effectiveness of project-based learning for science and STEAM education. Eurasia J Math Sci Technol Educ 19(5):em2256

Cohen L, Manion L, Morrison K (2017) Research methods in education, 8th edn. Routledge

Coskun Y (2018) A study on metacognitive thinking skills of university students. J Educ Train Stud 6(3):38–46

Darling-Hammond L, Flook L, Cook-Harvey C, Barron B, Osher D (2020) Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Appl Dev Sci 24(2):97–140

DeCoito I, Briona LK (2023) Fostering an entrepreneurial mindset through project-based learning and digital technologies in STEM teacher education. In: Kaya-Capocci S, Peters-Burton E, (eds.), Enhancing entrepreneurial mindsets through STEM education. Springer International Publishing, Cham, p 195–222

Devanda B, Elizar E (2023) The effectiveness of the STEM project based learning approach in physics learning to improve scientific work skills of high school students. Int J Hum Educ Soc Sci 2(4):1219–1226

Dolmans DHJM (2019) How theory and design-based research can mature PBL practice and research. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 24(5):879–891

Erstad O, Voogt J (2018) The twenty-first century curriculum: issues and challenges. In: Voogt J, Knezek G, Christensen R, Lai KW (eds) Springer international handbooks of education. Springer, Cham. p 19–36

Gelerstein D, Río RD, Nussbaum M, Chiuminatto P, López X (2016) Designing and implementing a test for measuring critical thinking in primary school. Think Skills Creat 20:40–49

Harden RM (2018) Ten key features of the future medical school—not an impossible dream. Med Teach 40(10):1010–1015

Holmes V-L, Hwang Y (2016) Exploring the effects of project-based learning in secondary mathematics education. J Educ Res 109(5):449–463

Huang W, London JS, Perry LA (2022) Project-based learning promotes students’ perceived relevance in an engineering statistics course: a comparison of learning in synchronous and online learning environments. J Stat Data Sci Educ 00(0):1–9

Jincheng J, Chayanuvat A (2020) The effects of project-based learning on Chinese vocabulary learning achievement of secondary three Thai students. Walailak J Learn Innov 6(2):133–164

Kaendler C, Wiedmann M, Rummel N, Spada H (2015) Teacher competencies for the implementation of collaborative learning in the classroom: a framework and research review. Educ Psychol Rev 27(3):505–536

Kaptan F, Korkmaz H (2000) Fen öğretiminde tümel (portfolio) değerlendirme. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 19(19):212–219

Kiong TT, Rusly NSM, Abd Hamid RI, Swaran SCK, Hanapi Z (2022) Inventive problem-solving in project-based learning on design and technology: a needs analysis for module development. Asian J Univ Educ 18(1):271–278

Kolb B (1984) Functions of the frontal cortex of the rat: a comparative review. Brain Res Rev 8(1):65–98

Kollar I, Ufer S, Reichersdorfer E, Vogel F, Fischer F, Reiss K (2014) Effects of collaboration scripts and heuristic worked examples on the acquisition of mathematical argumentation skills of teacher students with different levels of prior achievement. Learn Instr 32:22–36

Kurniahtunnisa K, Wowor EC (2023) Development of STEM-project based learning devices to train 4C skills of students. Bioeduca J Biol Educ 5(1):66–78

Laal M, Laal M, Kermanshahi ZK (2012) 21st century learning; learning in collaboration. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 47:1696–1701

Le HC, Nguyen VH, Nguyen TL (2023) Integrated STEM approaches and associated outcomes of K-12 student learning: a systematic review. Educ Sci 13(3):297

Lim SW, Jawawi R, Jaidin JH, Roslan R (2023) Learning history through project-based learning. J Educ Learn (EduLearn) 17(1):67–75

Loyens SM, Van Meerten JE, Schaap L, Wijnia L (2023) Situating higher-order, critical, and critical-analytic thinking in problem-and project-based learning environments: a systematic review. Educ Psychol Rev 35(2):39

Markula A, Aksela M (2022) The key characteristics of project-based learning: how teachers implement projects in K-12 science education. Discip Interdiscip Sci Educ Res 4(1):1–17

Mazana MY, Montero CS, Casmir RO (2018) Investigating students’ attitude towards learning mathematics. Int Electron J Math Educ 14(1):207–231

Mielikäinen M (2022) Towards blended learning: stakeholders’ perspectives on a project-based integrated curriculum in ICT engineering education. Ind High Educ 36(1):74–85

Moghaddas M, Khoshsaligheh M (2019) Implementing project-based learning in a Persian translation class: a mixed-methods study. Interpret Transl Train 13(2):190–209

Mutakinati L, Anwari I, Kumano Y (2018) Analysis of Students’ critical thinking skill of middle school through STEM education project-based learning. J Pendidik IPA Indones 7(1):54–65

Muthukrishnan P, Choo KA, Kam NKBMZ, Omar II SMKP, Sipitang S, Singh MP (2022) Preservice teachers’ motivation and adoption of 21st-century skills. Comput Assist Lang Learn 23(4):205–218

Nadeak B, Naibaho L (2020) The effectiveness of problem-based learning on students’ critical thinking. J Din Pendidik 13(1):1–7

O’Grady-Jones M, Grant MM (2023) Ready coder one: collaborative game design-based learning on gifted fourth graders’ 21st century skills. Gift Child Today 46(2):84–107

Owens AD, Hite RL (2022) Enhancing student communication competencies in STEM using virtual global collaboration project based learning. Res Sci Technol Educ 40(1):76–102

Pan AJ, Lai CF, Kuo HC (2023) Investigating the impact of a possibility-thinking integrated project-based learning history course on high school students’ creativity, learning motivation, and history knowledge. Think Skills Creat 47:101214

Papanastasiou G, Drigas A, Skianis C, Lytras M, Papanastasiou E (2019) Virtual and augmented reality effects on K-12, higher and tertiary education students’ twenty-first century skills. Virtual Real 23:425–436

Parrado-Martínez P, Sánchez-Andújar S (2020) Development of competences in postgraduate studies of finance: A project-based learning (PBL) case study. Int Rev Econ Educ 35:100192

Paryanto P, Munadi S, Purnomo W, Nugraha RN, Altandi SA, Pamungkas A, Cahyani PA (2023) Implementation of project-based learning model to improve employability skills and student achievement. In: AIP conference proceedings, vol. 2671, No. 1. AIP Publishing. Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Paul R, Elder L (2008) Critical thinking: strategies for improving student learning. Part II. J Dev Educ 32(2):34–35

Pleşan NC (2021) The method of observing the student’s behavior in the educational environment. MATEC Web Conf 342:11009

Qureshi MA, Khaskheli A, Qureshi JA, Raza SA, Yousufi SQ (2021) Factors affecting students’ learning performance through collaborative learning and engagement. Interact Learn Environ 1–21

Radkowitsch A, Sailer M, Fischer MR, Schmidmaier R, Fischer F (2022) Diagnosing collaboratively: a theoretical model and a simulation-based learning environment. In: Fischer F, Opitz A (eds); Learning to diagnose with simulations: teacher education and medical education. Springer Nature, p 123–141

Rajabzadeh AR, Mehrtash M, Srinivasan S (2022) Multidisciplinary problem-based learning (MPBL) approach in undergraduate programs. In: New realities, mobile systems and applications: proceedings of the 14th IMCL conference. Springer International Publishing, Cham, p 454–463

Ramadhan S, Mardapi D, Prasetyo ZK, Utomo HB (2019) The development of an instrument to measure the higher order thinking skill in physics. Eur J Educ Res 8(3):743–751

Rati NW, Kusmaryatni N, Rediani N (2017) Model pembelajaran berbasis proyek, kreativitas dan hasil belajar mahasiswa. J Pendidik Indones 6(1):60–71

Rehman N, Zhang W, Mahmood A, Alam F (2021) Teaching physics with interactive computer simulation at secondary level. Cad Educ Tecnol Soc 14(1):127–141

Ridder HG (2014) Book Review: Qualitative data analysis. A methods sourcebook, vol. 28. Sage publications, London, England, p 485–487

Rizkiyah Z, Hariyadi S, Novenda I (2020) The influence of project based learning models on science technology, engineering and mathematics approach to collaborative skills and learning results of student. ScienceEdu 3(1):1–6

Roldán Roa E, Roldán Roa É, Chounta IA (2020) Learning music and math, together as one: towards a collaborative approach for practicing math skills with music. In: Collaboration technologies and social computing: 26th international conference, CollabTech 2020, Tartu, Estonia, September 8–11, 2020, proceedings 26. Springer International Publishing, p 143–156

Saduakassova A, Shynarbek N, Sagyndyk N (2023) Students’ perception towards project-based learning in enhancing 21st century skills in mathematics classes. Scientific Collection «InterConf» 150:159–170

Saqr M, López-Pernas S (2023) The temporal dynamics of online problem-based learning: why and when sequence matters. Int J Comput Support Collab Learn 18(1):11–37

Sevgül Ö, Yavuzcan HG (2022) Learning and evaluation in the design studio. Gazi Univ J Sci Part B Art Humanit Des Plan 10(1):43–53

Shah Bukhari SKU, Said H, Gul R, Ibna Seraj PM (2022) Barriers to sustainability at Pakistan public universities and the way forward. Int J Sustain High Educ 23(4):865–886

Simon MA (2020) Reconstructing mathematics pedagogy from a constructivist perspective. J Res Math Educ 26(2):114–145

Sithole A, Chiyaka ET, McCarthy P, Mupinga DM, Bucklein BK, Kibirige J (2017) Student attraction, persistence and retention in STEM programs: successes and continuing challenges. High Educ Stud 7(1):46–59

Sumarni W, Kadarwati S (2020) Ethno-stem project-based learning: its impact to critical and creative thinking skills. J Pendidik IPA Indones 9(1):11–21

Susanto E, Retnawati H (2016) PBL characterizes mathematics learning tools to develop HOTS for high school students. J Ris Pend Math 3(2):189–197

Suwastini NKA, Puspawati NWN, Adnyani NLPS, Dantes GR, Rusnalasari ZD (2021) Problem-based learning and 21st-century skills: are they compatible?. EduLite J English Educ Lit Cult 6(2):326–340

Szalay L, Tóth Z, Borbás R, Füzesi I (2023) Scaffolding of experimental design skills. Chem Educ Res Pract 24(2):599–623

Tee WJ (2018). Project-based learning for building work and life skills in line with TGC and purpose learning. In: Tang SF, Lim CL (eds); Preparing the next generation of teachers for 21st century education. IGI Global, p 109–125. https://www.igi-global.com/book/preparing-next-generation-teachers-21st/182585#table-of-contents

Tibi MH (2015) Technologies in education. In: Encyclopedia of education and human development, vol 10. Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Publishing LLC, p 201–238

Ventista OM (2018) Multi-trait multi-method matrices for the validation of creativity and critical thinking assessments for secondary school students in England and Greece. Int J Assess Tool Educ 5(1):15–32

Vogel F, Kollar I, Ufer S, Reichersdorfer E, Reiss K, Fischer F (2016) Developing argumentation skills in mathematics through computer-supported collaborative learning: the role of transactivity. Instr Sci 44:477–500

Wongdaeng M, Hajihama S (2018) Perceptions of project-based learning on promoting 21st century skills and learning motivation in a Thai EFL setting. J Stud English Lang 13(2):158–190

Yang D, Skelcher S, Gao F (2021) An investigation of teacher experiences in learning the project-based learning approach. J Educ Learn (EduLearn) 15(4):490–504

Yoon CH (2017) A validation study of the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking with a sample of Korean elementary school students. Think Skills Creat 26:38–50

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NR: made significant contributions to the conception and design of the study, writing, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. WZ: provided valuable insights into the theoretical framework conceptualization, resources, supervision, validation, and proofreading. AM: writing, review, and editing. MZF: actively participated in the manuscript revising for scientific accuracy and ensuring clarity in the “Methodology” section. SB: review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study received ethics approval “SNNU-ETH-2023-Ed1045” from the Institutional Ethical Board (IEB) of Shaanxi Normal University. The research team adhered to the ethical guidelines and principles set forth by Shaanxi Normal University throughout the study to ensure the responsible and respectful treatment of all participants involved.

Informed consent

In this study, all participants provided their informed consent in written form. Additionally, the ethics committee reviewed and approved the need for consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rehman, N., Zhang, W., Mahmood, A. et al. Fostering twenty-first century skills among primary school students through math project-based learning. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 424 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01914-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01914-5

This article is cited by

-

Effect of strategic memory advanced reasoning training (SMART) therapy for enhancing final-year high school students career choices

BMC Psychology (2025)

-

From doubt to adoption: impact of a STEAM-based intervention on teachers’ perceptions and use of digital learning objects

Journal of Computers in Education (2025)