Abstract

Parents’ expectations affect children’s key competencies acquired from STEM education, and influence their future career development. This study aimed to determine the influence of parents’ expectations on children’s key competencies gained through STEM education, with a particular focus on gender difference. A total of 736 parents (44% fathers and 56% mothers) of children aged 3–12 (50.4% boys and 49.6% girls) participated in a two-section survey and rated the degree of importance of each key competency. Subsequently, exploratory factor analysis was used to identify the potential structure of the STEM-related competencies, and ANOVA was used to gain further insights into the gender difference tendency. Results targeted 10 most emphasized competencies which were clustered into four categories, namely the Innovation factor (Inquiring competency, Creativity competency), the Social factor (Cooperative competency, Expressing competency), the Making factor (Hands-on competency, Problem-solving competency, Anti-frustration competency), and the Learning factor (Thinking competency, Knowledge acquisition competency, Concentration competency). Results also indicated that the parents had significantly different expectations for boys and girls regarding the expressing, thinking, knowledge acquisition, concentration, and hands-on competencies. Fathers’ and mothers’ expectations only differed for children’s anti-frustration competency. These findings provide deeper insights into STEM-related competencies from parents’ viewpoints, and contribute a greater understanding of gender difference in STEM education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the development of economic globalization and the intensification of international competition, STEM education has been vigorously developed in various countries due to its potential value in cultivating students’ creative and innovative abilities (Rozek et al., 2017). It emphasizes the integration of science, mathematics, engineering and technical education, breaking down the boundaries between disciplines, and focusing on cultivating students’ innovative thinking and ability to solve real-world problems (Meng et al., 2013).

Young students’ parents generally play a vital role in STEM education (Hill & Craft, 2003; Park & Holloway, 2016). Parents’ beliefs are crucial factors in setting up students’ positive attitudes toward science (Chen & Lin, 2019; Crano & Prislin, 2006). In various studies, parents who are actively involved in children’s extracurricular STEM activities (e.g., visiting museums, playing math games, assisting homework, introducing particular STEM careers) would significantly increase their children’s STEM learning motivation and performance (Archer et al., 2019; Wang, 2012). The younger children are, the more important is the effect of their parents’ participation and guidance (LeFevre et al., 2009; Froiland et al., 2012). Most of the time, parents’ positive expectations could have an even greater effect on children than their behaviors (An et al., 2019). Especially in eastern countries, where parents are considered to be more authoritarian, their expectations affect children’s learning performance to a higher degree (Liu et al., 2015).

Although a growing number of parents are realizing the importance of STEM education (Simunovic et al., 2018), there is no consensus among parents regarding what STEM education can do to improve children’s competencies. Parents generally want their children to be excellent (Zhan et al., 2021); however, it is not clear what they mean by “excellent,” and what competencies they expect their children to have.

Moreover, gender-bias among parents’ expectations has been reported in previous research (Eccles, 2014). Some parents are more inclined to expect boys to have a higher level of STEM-related competency, while girls are expected to have a higher level of language and reading competency (Jacobs, Eccles (1992)). It would be interesting to investigate whether a gender difference exists among parents regarding their children’s key competencies acquired from STEM education. To the best of our knowledge, there is limited research examining this issue.

Therefore, the present study addressed the following two research questions: (1) What kinds of key competencies do most parents expect their children to acquire from STEM education? (2) Does any gender difference tendency exist among parents?

Literature review

Parents expectations for their children

Parents play a vital role in children’s growth, so their expectations always affect children’s academic achievement (Boonk et al., 2018) and scientific activity participation (Boon, 2012). This is especially important for younger children, and presents a long-lasting effect (Froiland et al., 2012). Parents’ expectations are sometimes even more effective than the other types of actual engagements (e.g., homework tutoring, school activities involvement, etc.) (An et al., 2019; Castro et al., 2015). Expectations can be classified into outcome expectations and efficacy expectations (Bandura, 1977), where the latter have stronger predictive power than the former (Gubbins & Otero, 2020).

Previous studies have reported cross-cultural differences in parents’ expectations (Jhang & Lee, 2018). Leung and Shek (2015) found that Anglo-American parents emphasized external authority (i.e., following directions, being obedient, doing work according to external standards, and being truthful), rather than autonomous behaviors (i.e., making independent decisions, solving problems on one’s own, exercising self-control). In contrast, Mexico-American parents tend to emphasize development of autonomy over conformity. Moreover, Asian parents generally pay more attention to children’s academic achievement, social personality and adaptability, morals and ethics (Phillipson & Phillipson, 2017), while another study claimed that parents in western countries emphasize constructing children’s independence, self-reliance, self-esteem and self-confidence (Leung & Shek, 2015).

However, because of the cultural specificity of belief systems and the lack of tools to measure parents’ beliefs and expectations, there is very limited research examining parents’ expectations regarding their children’s key competencies (Leung & Shek, 2011), and even less research that discusses the issue of gender difference in parents’ expectations.

STEM-related key competencies

Students’ Key Competencies are also known as “21st Century Skills” or “Core Competencies,” which are usually critical skills and abilities that enable people to adapt to the information age and the knowledge society in the 21st century, to solve complex problems, and to adapt to unpredictable situations (Hu et al., 2019). Many countries have formulated their own educational goals within the "Key Competencies" framework. For example, the “21st century framework” proposed by the Partnership for 21st Century Learning (2009) is one of the most influential competency frameworks. It is composed of three core dimensions: (1) Learning and Innovation Skills, (2) Information, Media and Technology Skills, and (3) Life and Career Skills, which emphasize “creativity and innovation,” “critical thinking and problem solving,” “communication,” and “cooperation.” Based on this, a “4 C” skill framework was proposed by the National Education Association, highlighting the skills of Critical Thinking, Communication, Collaboration, and Creativity (Erdoğan, 2019).

Countries from Asia pay great attention to the construction of students’ key competencies. For example, the Japanese government (2014) proposed a framework of “21st century abilities” constituted by three levels: basic abilities, thinking abilities, and practical abilities, emphasizing students’ problem solving, creativity, logic, and meta-cognition. The South Korean government (2015) constructed a key competencies framework which emphasizes self-management, knowledge and information processing, creative thinking, aesthetic perception, sense of community, and communication ability aimed at cultivating innovative and interdisciplinary talents. The Chinese government (2016) defined students’ key competencies focusing on a person’s well-rounded development. It mainly focuses on the cultural basis, independent development, and social participation, emphasizing the students’ comprehensive performance of humanities, scientific spirit, learning, healthy living, responsibility and innovation.

It is believed that STEM education provides an effective way to cultivate students’ key competencies (Le et al., 2015; Zhan et al., 2022b). Students’ STEM-related key competencies are defined as the key competencies that a child obtains from STEM education. It covers relevant abilities, such as critical thinking (Hu et al., 2019; Kim, 2019), problem solving (Kyeong & Lee, 2018; Lee & Choi, 2017), scientific imagination (Techakosit & Nilsook, 2018), ICT skills (Tsukazaki et al., (2019)), communication ability (Kang & Moon, 2019; Zhan et al., 2022a), creativity (Kang et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2022; Zhan et al., 2022c), and information literacy (Gravel et al., 2018).

Some other studies noticed the gaps between STEM education and the required workplace skills, and examined whether frameworks for 21st century skills and engineering education cover all of the important STEM competencies. Jang (2016) claimed that the 21st century framework does not comprehensively cover all the important STEM competencies, notably problem-solving skills, systematic thinking skills, technology and engineering skills, as well as time, resource and knowledge management skills. However, this conclusion was made from the perspective of enterprise, rather than from parents’ perspectives, and it is mainly adopted in higher education rather than in the K-12 stage.

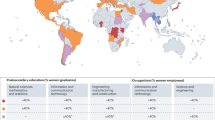

Gender difference in STEM education

Gender difference in STEM education exists in students’ enrollment in STEM education and occupation (Mann et al., (2015)). For example, in the United States, it was found that females comprised the majority of medical and health science degrees and occupations (U.S. Department of Education, 2014), but they were underrepresented in most mathematics fields (Van Tuijl & Walma, 2016). In OECD countries, females occupied <30% of positions in the engineering domain, and <20% in computer science (Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development (2013)). According to the U.S. Department of Education and National Center for Education Statistics, there were only 29%, 19%, 23%, and 34% of females who obtained doctoral degrees in mathematics and statistics, computer and information sciences, engineering, and physical and technological sciences, respectively (Snyder et al., 2016). The Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) also claimed that among engineering and technology undergraduates, less than 10% were females (Equality Challenge Unit, 2014).

With respect to STEM performance, males generally perform better in STEM-related disciplines, while females perform better in life science and have better verbal ability (Buser et al., 2014; Friedman–Sokuler & Justman, 2016; Wang, Degol (2017)). Males and females differ significantly in their spatial skills, which is a strong predictor of STEM success (Sorby et al., 2018; Yoon & Mann, 2017). On the contrary, in some empirical studies, the gender difference in STEM learning performance is not significant (Hyde, 2005), and sometimes girls achieve higher math scores than boys (Voyer & Voyer, 2014). However, even those females who perform excellently in mathematics and have more career choices still prefer to pursue non-STEM careers (Wang et al., 2013).

With respect to attitude towards STEM, females were reported to have a lack of confidence (Ellis et al., 2016) and interest (Wang & Degol, 2013) in STEM disciplines (Wang, Degol (2017)). More than twice as many males than females claimed their willingness to become engineers (Weber, 2012). Some researchers pointed out that the gender difference actually came from perceptions rather than abilities (Wang, Degol (2017)).

Parents generally have different expectations for boys and girls (Sainz & Muller, 2018), which tend to be consistent with gender stereotypes. Most parents have higher expectations for girls (Khachikian, 2019), and invest more in girls (Hao & Yeung, 2015) because they think girls need to work harder to get a better job (Dockery & Buchler, 2015). However, most parents believe boys are more suitable for STEM subjects. With respect to family impact, the parents are role models for their children (Fulcher, 2011). Parental gender stereotypes actually reflect societal norms of personal characteristics, and they might aggravate the gender difference in STEM (Ng Lane et al., 2018), and thus have a negative impact on gender equality, while also affecting educational equality (Van Tuijl & Walma, 2016).

Method

Participants

In this study, we distributed questionnaires randomly to parents with children aged from 3 to 12 years old who were currently taking STEM courses either at school or in STEM education centers in China. A total of 736 parents provided feedback to us, 324 (44%) of whom were fathers, and 412 (56%) mothers. As reported in the received questionnaires, 371 (50.4%) of the participants had sons and 365 (49.6%) had daughters. The parents were aged from 25 to 46 years old. Their occupations included teachers, soldiers, civil servants, bank staff, doctors, manufacturing managers, consultants, advertising experts, and engineers.

Measurement instruments

The Parents’ Expectation Survey (PES)

To collect the parents’ views on the STEM-related key competencies that they expected their children to develop, a Parents’ Expectation Survey (PES) was designed and distributed to the participants, comprising two sections. In the first section of the questionnaire, the parents’ demographic information (i.e., the parent’s gender, age, and job title, and their child’s gender, age, and years of joining STEM education) was collected.

The second section was designed by STEM educational experts according to a series of key competence frameworks and evaluations (i.e., Erdoğan, 2019; Force, 2013; Huo et al., 2020; Le et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2022; Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development (2005); Partnership for 21st Century Learning, 2009). It listed the 10 most frequently mentioned STEM-related competencies which have been used for years in the STEM education center for collecting parents’ expectations of the STEM educational service (Table 1). The participants were required to rate how important they regarded the listed STEM-related key competencies on a 7-point Likert scale, from 1 = “Least Important” to 7 = “Most Important."

Three experts from the fields of STEM education were invited to evaluate the face validity of the questionnaire (Holden, 2010) and to ensure that every item was clearly stated and the entire questionnaire captured the expected structure. Afterwards, internal testing of the questionnaire was conducted, and the Cronbach’s alpha index was 0.872, indicating good internal reliability.

The interview outline

In order to know more about the parents’ expectations, an interview outline was developed. Instructions were given to the parents, as follows, “We have collected a series of STEM competencies that represent parents’ expectations for their children. Now we would like to find out which ones you most emphasize to clarify the competency structure.” The interviewees were expected to answer the following questions: First, can you tell us your definition of these selected competencies? Second, why do you expect your child to obtain these competencies in STEM education? Can you tell us more about your expectations? Third, will you expect different competencies if your child is a girl/boy? There was a total of 46 parents who participated in the interviews, and their answers were recorded for further discussion on parents’ expectations.

Research procedure

We distributed the questionnaire in a STEM education center located in south China through a snowball sampling method. In this way, eligible participants, that is, parents who had children aged from 3 to 12 years old currently taking STEM courses, were invited to complete the questionnaire. They then helped to invite more eligible participants to complete the survey. After the survey, we randomly selected 46 parents who left contact information in the questionnaire to participate in a one-to-one interview, in order to know more about the reasons why they expected their children to acquire certain competencies from STEM education. Instructions were provided in order to make sure all the participants were knowledgeable enough in the topic and clearly understood the relevant terminologies. Participants provided their informed consent, stating that they knew they were participating in an evaluation study, and that the data they provided were anonymous and would be used for scientific research purposes only. Every participant received a gift as a token of our gratitude after they completed the questionnaire to an acceptable standard. We ensured that all procedures of our study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the American Psychological Association.

Data analysis

All quantitative data in this study were analyzed using SPSS 26 to conduct descriptive statistics, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), and ANOVA. EFA was utilized to extract major themes in a data-driven method and to explore the potential constructs among the critical competencies. Then, the gender difference tendency of parents’ expectations was analyzed on both the children’s side and the parents’ side: two one-way ANOVAs were conducted on the dataset to compare the value of expectations between boys and girls, and between fathers and mothers. Qualitative data were used to triangulate the quantitative data and to delve into the potential reasons behind parents’ expectations and gender difference tendencies. The researchers took turns coding the interview transcripts in a back-to-back manner. A consistency validation test was conducted which achieved a Kappa value of 0.894, indicating high consistency between coders. Then the researchers negotiated on the coding results and reached agreement on the connotation of the themes and the reasons causing the gender differences.

Result

The expected STEM competencies rated by parents

Descriptive analysis

The means and standard deviations (SD) of the key competencies rated by parents are listed in Table 1 in sequence of descending means by Likert scores. As can be seen, the mean scores of all competencies on the 7-point Likert scale ranged from 5.96 to 6.26. The Inquiring competency ranks the top in terms of mean scores, while Creativity ranks the top in terms of consensus. With regard to the highest mean score, parents generally had greater expectations regarding the cultivation of Inquiring ability than Problem-solving ability, because they think the ability to discover problems is more important than the ability to solve problems, and STEM education provides the context for children to explore with curiosity and high motivation. With regard to the lowest standard deviation, parents greatly emphasized the cultivation of Creativity in STEM education, because most parents realize the importance of training their children to be excellent innovative talents in this fast-changing era.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Before carrying out the EFA, KMO statistics were conducted to determine the suitability of the factor analysis. All the variables in the overall KMO value must be >0.50. In this study, the overall KMO value was 0.846, indicating that the correlation patterns were acceptable for reliable factor analysis (Andy, 2000).

Besides, normal distribution can be determined by the skewness and kurtosis values of each questionnaire item. Kline (1998) suggested that skewness absolute values of <3 and kurtosis values >10 should be regarded as normal states. Furthermore, Noar (2003) suggested that skewness absolute values should not be >1 and the kurtosis absolute values should not be >2. In this study, the Skewness value for each item ranged from −0.627 to −0.783, and the Kurtosis value for each item ranged from 0.341 to 1.582, which were within acceptable ranges, indicating a normal distribution. The questionnaire items were thus suitable for further factor analysis.

Subsequently, EFA was used to explore the potential construct of the factors. The principal component analysis was adopted for factor extraction, and Quartimax with Kaiser Normalization was adopted for factor rotation. The factor loading of each item weighed from 0.686 to 0.891.

As shown in Table 2, the EFA results revealed that the parents’ responses on the questionnaire were clustered into four orthogonal factors, “Innovative factor,” “Social factor,” “Making factor” and “Learning factor.” These factors accounted for 80.564% of the variance. The eigen-values of the four factors were both larger than one. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the four factors were 0.840, 0.841, 0.785, and 0.878, and the overall alpha was 0.878. Therefore, a STEM-related key competency framework with four factors was deemed to be sufficiently reliable for representing parents’ expectations regarding their children’s competencies.

The “Innovative factor” includes two key competencies: the “inquiring competency” and the “creativity competency.” The former pays attention to the children’s curiosity, problem discovery and exploration, while the latter emphasizes the innovative ideas and works generated by children. This dimension is related to the competence of “learning and innovation skills” in the partnership for 21st century skills and the competence of “practice and innovation” in the development of core literacy of Chinese students, paying attention to students’ innovative consciousness in daily life, problem solving and adapting to challenges.

The “Social factor” includes two competencies: “cooperative competency” and “expressing competency.” The former focuses on children’s ability to communicate and cooperate with others, while the latter focuses on whether children can express their thoughts and feelings effectively. There are similar descriptions in the OECD’s key competences framework, the EU’s key competences for lifelong learning, New Zealand’s nature of the key competences, Japan’s 21st century capabilities, Singapore’s framework for 21st century competences and student outcomes, Advancing 21st Century Competencies in South Korea, and the development of core literacy of Chinese students and core literacy in Taiwan. This is a dimension that has been frequently included in most international key competency frameworks.

The “Making factor” includes three competencies. Among them, the “Hands-on competency” refers to skillfully making works by using engineering technology, the “Anti-frustration competency” emphasizes keeping optimism and grit in the face of failures and setbacks, and the “Problem-solving competency” refers to children actively seeking feasible solutions to actual problems. Therefore, the making factor represents children’s operation skills, mentality and comprehensive problem-solving ability in practice. Its connotation is close to the indicator “Learning to do” in UNESCO’s five pillars of lifelong learning, “Practical ability” in 21st century capability of Japan, “practice and innovation” in the development of core literacy of Chinese students, and “labor skill” in the Concentric circle model of Chinese students’ core literacy, which also emphasize the making competencies for future talents.

The “Learning factor” includes three competencies: The “Thinking competency” refers to children thinking and reflecting in a flexible and reasonable way, the “Knowledge acquisition competency” refers to children learning and acquiring knowledge effectively, and the “Concentration competency” emphasizes children keeping concentrated on the learning tasks. The first-level learning factor represents children’s ability to acquire knowledge, focus on tasks, and reflect on themselves in the learning process. “Learning to know” in the five pillars of lifelong learning proposed by UNESCO, “learning approaches and cognition” in the global learning domains framework, “learning to learn” in the EU key competencies for lifelong learning, “learning and innovation skills” in the Partnership for 21st century skills, “Thinking and learning to learn” in the Finnish well-rounded competences, and “learning to learn” in the development of core literacy of Chinese students all emphasize similar scopes.

Gender difference in parents’ expectations

Considering the research purpose of analyzing gender difference in this study, we aimed to balance both the parents’ and their children’s gender in our sample, although the actual situation is that more male students are enrolled in STEM education centers and STEM-related programs, and many more mothers take charge of their children’s STEM education. Thus, it required greater efforts to reach female students’ parents, especially fathers. Table 3 presents the means and standard deviations of fathers’ and mothers’ expectations for their children.

As can be seen in Table 3, from fathers’ perspectives, boys were expected to have the highest hands-on competency and the lowest concentration, while girls were expected to have the highest expressing competency and the lowest hands-on competency. From mothers’ perspectives, boys were expected to have the highest creativity and the lowest cooperative competency, while girls were expected to have the highest inquiring competency and the lowest hands-on competency.

Since this study focused on both the parents’ gender and the children’s gender, a 2*2 factorial design was implemented. Two One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) were used to test each hypothesis, followed by a MANOVA to test the interaction hypotheses between parents’ gender and children’s gender on mean expectation scores.

Parents’ expectations for boys versus girls

ANOVA results indicated that the parents had significantly different expectations for boys and girls in terms of expressing competency (girls > boys, F(1,735) = 8.513, p = 0.004, Cohen’s d = 0.219), hands-on competency (boys > girls, F(1,735) = 29.388, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.401), thinking competency (girls > boys, F(1,735) = 8.563, p = 0.004, Cohen’s d = 0.217), learning competency (girls > boys, F(1,735) = 14.400, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.282), and concentration competency (girls > boys, F(1,735) = 35.88, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.438). No significant difference was found in the parents’ expectations for boys and girls regarding inquiring competency, creativity, cooperative competency, anti-frustration competency, or problem-solving competency.

Some participants shared their points of view on the reasons why most parents expected girls to have better thinking ability and learning ability than boys. The major reasons mentioned were: “Girls develop earlier than boys, so they are more mature in mental and emotional status of learning and expressing at the primary school level” and “Girls have higher motivation and are more diligent in academic study, so they generally perform better than boys at school.”

Besides, most parents held the stereotypes that girls have a natural advantage of expressing competency and concentration competency, and are better at memorizing things and taking examinations, while boys are better at hands-on competency and making things. For “expressing ability,” one parent said, “Effective communication with others is crucial for one to be an influential decision maker and leader in a team. STEM programs have many group activities that give children opportunities to share ideas and interact with others. Girls have a natural advantage in expression, that’s why I expect my daughter to develop excellent communication skills in the STEM program.”

For “concentration,” one parent stated, “Children nowadays live in an information-explosive society where it is difficult to stay focused amid all kinds of electronic devices. The STEM curriculum encourages children to learn by doing and playing. They need to learn independently and follow a relatively long-term project, which I think is beneficial for attention development.” Another said, “My son is easily distracted by trivial things; I used to suspect he had ADHD. However, when he is learning STEM projects or making things, he is surprisingly focused and concentrated. That’s why I expect him to improve concentration in STEM education. If I had a daughter, since girls are biologically more advanced in this area, I might expect more regarding her concentration level.”

For “hands-on competency,” parents claimed that “Boys likes making things, just like they enjoy destroying things. STEM education actually provides them with the space to create” and “Hands-on skills enable children to visualize their imagination, creativity and problem-solving abilities, which cultivates their interest in learning. STEM courses focus on practice and experimentation, including programming and robotics skills. I think boys have a natural interest and talent for mechanical manufacturing and scientific principles, so I hope my son can further develop this competence in STEM courses. Hopefully, he will be able to demonstrate his technical strength and creative ability in the workplace in the future.”

Fathers’ versus mothers’ expectations

ANOVA results indicated that mothers had greater expectations regarding their children’s anti-frustration competency acquired from STEM education, F(1,735) = 5.698, p = 0.017, Cohen’s d = 0.169. Besides, the MANOVA results indicated that the interaction effect only existed in expressing competency (p = 0.025, η2 = 0.007, observed power = 0.609). Mothers had equal expectations for boys’ and girls’ expressing ability, while fathers had significantly greater expectations for girls.

Most fathers believed that expressing ability is very important, and girls have greater potential to achieve it from STEM education. For example, one father said, “I want my daughter to further her expression skills in STEM programs, which will help her present her ideas and opinions confidently in various fields. Girls are often nuanced and articulate, while boys are generally more composed and responsible for technical tasks. Take myself as an example; I am good at tinkering with things, I mended all the furniture at home, but I feel it is difficult to express my feelings. My daughter seems to be born to express herself. I hope she can stand out due to this in the future” and “Girls themselves are better at understanding the emotions and needs of others, and the teamwork and complex solving tasks in STEM programs sometimes lead to conflicts among peers, in which girls might need to give play to their strengths by actively communicating and mediating; in this way, I expect that my kids can develop the expressing and communication skills to a higher level.”

Besides, interestingly, most mothers expressed more concern about the anti-frustration ability and resilience. Compared to fathers’ optimism and sometimes even a free-range mentality, mothers were generally more worried about every aspect of their children. Many of them treat STEM projects as a good opportunity for children to face failure and adversity, which is crucial for children’s future development. For example, one mother said “In today’s competitive society, it’s critical to persevere, adapt and learn from failure. I think STEM education provides a great opportunity for children to face adversity. STEM programs challenge children to solve complex problems. They need to try, fail, and try again, which helps them develop resilience and resistance to setbacks” and "Nowadays, children live a happy life. Most of the time, they rely too much on adults, and their resilience needs to be improved. The tasks in STEM courses are closer to real situations than to textbook knowledge, and are more flexible and complex in problem solving, which helps children develop a positive mindset to adapt social challenges.”

Discussion

The key competencies most expected by parents

Referring to the first research question: “What kinds of key competencies do most parents expect their children to acquire from STEM education?”, 10 competencies were highlighted in the following sequence of importance: (1) Inquiring competency, (2) Creativity competency, (3) Problem-solving competency, (4) Knowledge-Acquisition competency, (5) Expressing competency, (6) Thinking competency, (7) Anti-frustration competency, (8) Hands-on competency, (9) Concentration competency, and (10) Cooperative competency. Many parents emphasized the cultivation of Creativity in STEM education because they realize the importance of innovative thinking in this fast-changing era. Some parents pointed out that the ability of discovering problems is more important than solving problems, and STEM education provides the context for children to explore with curiosity and high motivation.

These competencies have been categorized into four clusters (i.e., Innovative factor, Social factor, Making factor, and Learning factor). Parents placed most emphasis on the Innovative factor, followed by the Making factor, the Learning factor, and the Social factor. Compared to the Learning and Innovation Skills in the “21st Century Learning Framework” in the United States, we found that parents’ expectations covered the 4C skills (Critical Thinking and Problems Solving Skills, Communication skills, Collaboration skills, Creativity and innovation skills), and also have a close relationship with the key competency framework proposed by the OECD, UNESCO, the European Commission and China’s Core Competency system.

However, there is a certain difference existing between parents’ expectations and the big picture of the core competency framework. To further analyze the differences and connections between key competencies at the parent and state levels, we selected 16 typical competency frameworks offered by international organizations such as UNESCO, the OECD, and the European Union, along with economies including the United States, Finland, Singapore, and China, and compared them with our findings (Appendix I).

On the one hand, we found that parents’ expectations regarding STEM were more egocentric, more focused and more concrete. For example, the “Social and civic competences” (OECD, 21st century skills), the “communication skills” from the Korean Core Competency system, and “social participation” from the Chinese Core Competency system all emphasized the civic role as a social participator, while the Social Ability proposed by parents only emphasized expression and cooperation, indicating that parents expected their children to practice working with peers in the STEM projects, as well as to promote their expressing skills when introducing their works during presentations, rather than the broader scope of social responsibility.

On the other hand, the state-level competency framework generally focuses on children’s life-long development (e.g., social participation, cultural cognition, information literacy, etc.), while parents’ expectations mainly focused on children’s learning and thinking competence, and regarded STEM education as a kind of short-term training, rather than considering the broad scope of society. Thus, parents seldom expect patriotic citizenship, social responsibility or culture competency from STEM education, which are frequently mentioned in the core competencies proposed by UNESCO, the European Union, the Chinese Core Competency system, and so on.

Besides, there were some interesting discoveries in the parents’ expectations framework. One unique aspect of parents’ expectations is the Making factor, which emphasizes students’ hands-on competency, specifically related to engineering manufacturing. This is meaningful, because STEM education is generally known as “learning by doing,” which sparks children’s involvement in hands-on activities. During the making and tinkering process, the children will meet different kinds of problems and difficulties, which is also valued by parents to a great degree. As can be seen in the Making factor, the anti-frustration ability is a competency that seldom appeared separately in the other competency frameworks, but was highly-emphasized by the parents in this study.

Moreover, the parents’ expectations framework also reflects the consideration of students’ age. For example, children’s concentration is given great importance, which is unique considering the other key competency frameworks. For children aged 3–12 years old, concentration is crucial for their development; thus, parents expect they can be more concentrated during hands-on tasks in STEM education. Also, children aged between 3 and 11 years old are at the Pre-operational stage and the Concrete operational stage (Piaget, 1962), and have limited abstract thinking ability. Parents might need more help to cultivate their thinking ability in a scientific way under natural rules.

Additionally, parents’ expectations are closely related to the cultural background. Parents from western countries would place more stress on the value of establishing independence, self-esteem and self-confidence, stressing independence and individualism, while parents from eastern countries would be more authoritative and play a more important role in their children’s learning and growth (Liu et al., 2015). They generally attach importance to helping children achieve the goal of socialization, developing good personality, adaptability, character, morality and ethics, inheriting national culture, and making contributions to society (Chao, 1995). Some researchers even claimed that the parenting style in eastern families is mostly focused on guiding the children to pursue academic success (Phillipson & Phillipson, 2017). The data of the current study came from an Asian country, and we found that parent participants placed most emphasis on children’s lifelong competencies rather than only on learning achievement, which was inconsistent with the previous studies, indicating that with the development of society and globalization, parents from eastern countries now have a more international view of child-rearing. However, most of them still believed that STEM is mostly related to science and technology, and not related to the cultivation of children’s cultural inheritance, social responsibility, moral quality and the other potential competencies.

A gender difference tendency exists in parents’ expectations

Referring to the research question “Is there any gender difference tendency existing in parents’ expectations?”, comparing boys with girls, fathers expected girls to have the highest expressing competency, which is consistent with a previous study (Eccles et al., 1990), and is supported by studies which found that females have more advantages in terms of verbal ability (Buser et al., 2014; Wang, Degol (2017)). This finding indicates that fathers tend to want to train girls to have higher expressing competency. Family communication has a greater impact on girls than on boys (An et al., 2019). With respect to the hands-on competency, boys and girls seem to receive opposite expectations. Parents had significantly higher expectations for girls than for boys in most competencies, except for the hands-on competency. Boys generally performed better in hands-on activities, and thus there were greater expectations on them regarding the making competency.

Most parents had greater expectations on girls than on boys regarding the expressing competency, thinking competency, learning competency and concentration competency. One major possible reason is that girls generally develop earlier than boys (Johansson et al., 2007), and most girls perform better than boys in school settings (Li et al., 2019; Zhan et al., 2015). Most parents hold the stereotypes that girls have a natural advantage in terms of expressing competency and concentration competency, and are better at memorizing things and taking examinations, while boys are better at hands-on competency and making things. The possible reason for the gender difference might be related to internal factors (i.e., biological factors) such as students’ interest and ability tendencies (Sorby et al., 2018), as well as external factors (environmental factors) such as family and social culture (Wang & Degol, 2013).

Comparing fathers’ expectation with mothers’, fathers generally expected more for children’s external capabilities (i.e., boys are expected to have the highest hands-on competency, and girls are expected to have the highest expressing competency), while mothers generally expect more regarding children’s internal capabilities (i.e., boys are expected to have the highest creativity competency, while girls are expected to have the highest inquiring competency). Reflecting on the findings, fathers generally have more purposeful and utilitarian expectations, while mothers considered children’s anti-frustration competency when facing challenges.

This may be related to the gender stereotype in China, where men are usually expected to be masculine, resilient, and career-focused, while women are considered to be gentle, submissive, and emotionally delicate (Liu & Tong, 2014). For example, girls are perceived to have advanced language skills, so fathers may place higher expectations on daughters in STEM education, hoping they can use their strengths to get better opportunities for development. This perception actually reflects a utilitarian expectation that fathers are more concerned with their children’s career success. In contrast, mothers take care of most of the issues related to raising children, so they cared and worried more about the children’s emotional status. Considering the competitive pressures of the labor market, out of empathy, mothers may pay more attention to anti-frustration ability, hoping their children will develop a good mindset from solving complex problems and dealing with failure, which are built into STEM programs.

Implications

This study contributes to the literature by providing deeper insights into children’s STEM-related key competencies from parents’ perspectives, which could be a necessary addition to the existing key competence framework that was mainly established from the perspective of experts. As the first-order guardians of children, parents play an important role in children’s STEM learning and affect children’s perceptions of their own STEM self-efficacy (Fouad & Santana, 2017; Rice et al., 2013). The Pygmalion effect indicated that the expectations for children will affect the children’s behavior (Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968; Schunk et al., 2014), especially their academic performance, cognition and social development (Fantuzzo et al., 2004; Howard et al., 2019). With the parents’ support and encouragement, children generally do better in STEM learning (Sahin et al., 2018). Some critical factors identified in this study were neglected in most of the existing frameworks (e.g., Hands-on ability, Anti-frustration ability), while they were greatly emphasized by parents; this might need further attention in STEM education.

Moreover, the parents’ expected competencies proposed in this study could also help to set up an evaluation model for STEM education output, which the schools and organizations could use to assess the competencies that parents care most about. Parents’ gender stereotypes might further reduce female participations in STEM fields. Therefore, it might be necessary to guide parents according to their expectations and help them to evenly understand the core competencies that children should acquire.

As for the limitations of this study, we only recruited one of each child’s parents (i.e., either mother or father). In the future, it would be ideal to examine both parents of a child in a survey or even in an interview to obtain further insights. It might also be interesting to compare the parents’ expectations with teachers’ or children’s own expectations, so as to investigate the distribution of the parents’ expectations and society’s expectations. Moreover, future research could also be considered to compare parents’ expectations in different countries.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

An GQ, Wang JY, Yang Y (2019) Chinese parents’ effect on children’s math and science achievements in schools with different SES. J Comp Fam Stud 50(2):139–161. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.50.2.003

Andy F (2000) Discovering statistics using spss for windows: advanced techniques for the beginner. Sage Publications, https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=ec2b03dd-7989-4d4b-9f47-a7d9e686f190

Archer L, Dawson E, DeWitt J, Seakins A, Wong B (2019) “Science capital”: A conceptual, methodological, and empirical argument for extending bourdieusian notions of capital beyond the arts. J Res Sci Teach 56(3):371. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21478

Bandura A (1977) Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psycholl Rev 84(2):191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.84.2.191

Boon HJ (2012) Regional Queensland parents’ views of science education: some unexpected perceptions. Aust Educ Res 39(1):17–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-011-0045-5

Boonk L, Gijselaers HJM, Ritzen H, Brand-Gruwel S (2018) A review of the relationship between parental involvement indicators and academic achievement. Educ Res Rev 24:10–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.02.001

Buser T, Niederle M, Oosterbeek H (2014) Gender, competitiveness, and career choices. Q J Econ 129(3):1409–1447. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju009

Castro M, Exposito-Casas E, Lopez-Martin E, Lizasoain L, Navarro-Asencio E, Gaviria JL (2015) Parental involvement on student academic achievement: a meta-analysis. Educ Res Rev 14:33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.01.002

Chao RK (1995) Chinese and European American cultural models of the self- reflected in mothers ’ childrearing beliefs. J Soc Psychol Anthropol 23(3):328–354. http://h-s.doi.org.scnu.vpn358.com/10.1525/eth.1995.23.3.02a00030

Chen CS, Lin JW (2019) A practical action research study of the impact of maker-centered STEM-PjBL on a rural middle school in Taiwan. Int J Sci Math Educ 17(1):85–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-019-09961-8

Crano WD, Prislin R (2006) Attitudes and persuasion. Ann Rev Psychol 57(1):345–374. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190034

Dockery AM, Buchler S (2015) The influence of gender on pathways into the labor market: evidence from Australia. In Gender, education and employment an international comparison of school-to-work transitions. Edward Elgar Publishing, p 81–99. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784715038.00013

Eccles JS (2014) Gendered socialization of STEM interests in the family. Int J Gend Sci Technol 7:116–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1990.tb01929.x

Eccles JS, Jacobs JE, Harold RD (1990) Gender role stereotypes, expectancy effects, and parents’ socialization of gender differences. J Soc Issues 46(2):183–201. https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=4094052335d8f11a70b48de380120c6f&site=xueshu_se&hitarticle=1

Ellis J, Fosdick BK, Rasmussen C (2016) Women 1.5 times more likely to leave stem pipeline after calculus compared to men: lack of mathematical confidence a potential culprit. Plos One 11(7):e0157447. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157447

Equality Challenge Unit. (2014). Equality in higher education: Statistical report 2014. Equality Challenge Unit London. http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/343157

Erdoğan V (2019) Integrating 4C skills of 21st century into 4 language skills in EFL classes. Int J Educ Res 7(11):120, https://www.ijern.com/journal/2019/November-2019/09.pdf

Fantuzzo J, McWayne C, Perry MA, Childs S (2004) Multiple dimensions of family involvement and their relations to behavioral and learning competencies for urban, low-income children. School Psychol Rev 33:467–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2004.12086262

Force LMT (2013) Toward universal learning: What every child should learn (Report No. 3 of the learning metrics task force). UNESCO Institute for Statistics. https://www.mendeley.com/catalogue/d0550cb8-88e1-3bf0-9353-d4a68d96bb23/

Fouad NA, Santana MC (2017) SCCT and underrepresented populations in STEM fields: moving the needle. J Career Assess 25:24–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072716658324

Friedman-Sokuler N, Justman M (2016) Gender streaming and prior achievement in high school science and mathematics. Econ Educ Rev 53:230–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.04.004

Froiland JM, Peterson A, Davison ML (2012) The long-term effects of early parent involvement and parent expectation in the USA. Sch Psychol Int 34(1):33–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034312454361

Fulcher M (2011) Individual differences in children’s occupational aspirations as a function of parental traditionality. Sex Roles 64(1-2):117–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9854-7

Gravel BE, Tucker-Raymond E, Kohberger K, Browne K (2018) Navigating worlds of information: STEM literacy practices of experienced makers. Int J Technol Des Educ 28(4):921–938. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-017-9422-3

Gubbins V, Otero G (2020) Determinants of parental involvement in primary school: evidence from Chile. Educ Rev 72(2):137–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1487386

Hao LX, Yeung WJJ (2015) Parental spending on school-age children: structural stratification and parental expectation. Demography 52(3):835–860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0386-1

Hill NE, Craft SA (2003) Parent-school involvement and school performance: mediated pathways among socioeconomically comparable African American and Euro-American families. J Educ Psychol 95(1):74–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.74

Holden RR (2010) Face validity. The corsini encyclopedia of psychology, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0341

Howard NR, Howard KE, Busse R, Hunt C (2019) Let’s talk: an examination of parental involvement as a predictor of STEM achievement in math for high school girls. Urban Educ. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085919877933

Hu HW, Chiu CH, Chiou GF (2019) Effects of question stem on pupils’ online questioning, science learning, and critical thinking. J Educ Res 112(4):564–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2019.1608896

Huo L, Zhan Z, Mai Z, Yao X, Zheng Y (2020) A case study on C-STEAM education: investigating the effects of students’ STEAM literacy and cultural inheritance literacy. ICTE 2020. CCIS, Vol. 1302. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-4594-2_1

Hyde JS (2005) The gender similarities hypothesis. Am Psychol 60(6):581–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.581

Jacobs JE, Eccles JS (1992) The impact of mothers’ gender-role stereotypic beliefs on mothers’ and children’s ability perceptions. J Pers Soc Psychol 63(6):932–944. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.6.932

Jang H (2016) Identifying 21st century STEM competencies using workplace data. J Sci Educ Technol 25(2):284–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-015-9593-1

Jhang FH, Lee YT (2018) The role of parental involvement in academic achievement trajectories of elementary school children with Southeast Asian and Taiwanese mothers. Int J Educ Res 89:68–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2017.09.003

Johansson A, Brunnberg E, Eriksson C (2007) Adolescent girls’ and boys’ perceptions of mental health. J Youth Stud 10(2):183–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260601055409

Kang Y, Moon S (2019) Effects of invention education using bio-inspired technology on STEAM literacy of elementary students. J Educ 39(2):169–187. https://doi.org/10.25020/je.2019.39.2.169

Khachikian O (2019) Protective ethnicity: how Armenian immigrants’ extracurricular youth organizations redistribute cultural capital to the second-generation in Los Angeles. J Ethnic Migr Stud 45(13):2366–2386. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1497954

Kim S (2019) Research trends and issues of home economics based STEAM education in Korea: a systematic literature review. J Learn Center Curric Instr 19(22):611–630. https://doi.org/10.22251/jlcci.2019.19.22.611

Kline RB (1998) Principles and practise of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press, NY, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233896145_Principles_and_Practice_of_Structural_Equation_Modeling

Kyeong KM, Lee YL (2018) A study on the STEAM literacy and problem solving of elementary gifted students in the perspective of embodied cognition: focusing on the concept of angle in the Goldberg device. J Learn Center Curric Instr 18(19):403–432. https://doi.org/10.22251/jlcci.2018.18.19.40

Le Q, Le H, Vu C, Nguyen N, Nguyen A, Vu N (2015) Integrated science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) education through active experience of designing technical toys in Vietnamese schools. Br J Educ Soc Behav Sci 11(2):1–12. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJESBS/2015/19429

Lee G, Choi J (2017) The effects of STEAM-based mathematics class in the mathematical problem-solving ability and self-efficacy. J Elem Math Educ Korea 21(4):663–686. https://www.koreascience.or.kr/article/JAKO201710648288123.pdf

LeFevre JA, Skwarchuk S, Smith-Chant BL, Fast L, Kamawar D, Bisanz J (2009) Home numeracy experiences and children’s math performance in the early school years. Can J Behav Sci 41(2):55–66. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014532

Leung JTY, Shek DTL (2011) Poverty and adolescent developmental outcomes: a critical review. Int J Adolesc Med Health 23(2):109–114. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh.2011.019

Leung JTY, Shek DTL (2015) Parental beliefs and parental sacrifice of Chinese parents experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong: implications for social work. Br J Soc Work 45(4):1119–1136. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct190

Li M, Hao Y, Wang J (2019) Gender differences in students’ academic achievement: a meta-analysis of large scale assessment data. Educ Sci Res 11:34–42. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2019.06.13

Lin Z, Lin Z, Zhan Z, Wang X (2022) Evaluating student’s creative thinking in STEAM education model construction and validation. In 2022 3rd International Conference on Education Development and Studies (ICEDS’22), ACM, New York, p 96–103. https://doi.org/10.1145/3528137.3528143

Liu A, Tong X (2014) The present situation of gender attitudes and the factors influencing them: based on the third survey of women’s social status in China. Soc Sci China 02:116-129+206-207. CNKI:SUN:ZSHK.0.2014-02-009

Liu JW, McMahon M, Watson M (2015) Parental influence on mainland Chinese children’s career aspirations: child and parental perspectives. Int J Educ Vocat Guid 15(2):131–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-015-9291-9

Mann A, Legewie J, DiPrete TA (2015) The role of school performance in narrowing gender gaps in the formation of STEM aspirations: a cross-national study. Front Psychol 6:171. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00171

Meng C, Idris N, Leong KE, Daud M (2013) Secondary school assessment practices in science, technology and mathematics (STEM) related subjects. J Math Educ 6(2):58–69. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2431552

Ministry of Education (2015) Finalized and released the 2015 revised curriculum outline and syllabus. https://www.moe.go.kr/boardCnts/viewRenew.do?boardID=294&lev=0&statusYN=C&s=moe&m=020402&opType=N&boardSeq=60753

National Institute for Educational Policy Research. (2014) Basic Research on Curriculum Development Summary of Report 7: Principles of Curriculum Standards for the Comprehensive Development of Qualities and Abilities. Retrieved from https://www.nier.go.jp/05_kenkyu_seika/pdf_seika/h25/2_1_summary.pdf

Ng Lane J, Ankenman B, Iravani S (2018) Insight into gender differences in higher education: evidence from peer reviews in an introductory stem course. Serv Sci 10(4):442–456. https://doi.org/10.1287/serv.2018.0224

Noar SM (2003) The role of structural equation modeling in scale development. Struct Equ Modeling 10(4):622–647. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1004_8

Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development (2005) The definition and selection of key competencies: executive summary. OECD. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/47/61/35070367.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development. (2013). Education at a glance 2013: OECD indicators: OECD. http://www.oecd.org/education/eag2013%20(eng)-FINAL%2020%20June%202013.pdf

Park S, Holloway SD (2016) The effects of school-based parental involvement on academic achievement at the child and elementary school level: a longitudinal study. J Educ Res 110(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2015.1016600

Partnership for 21st Century Learning (2009) Framework for 21st century Learning. http://www.p21.org/our-work/p21-framework

Phillipson S, Phillipson SN (2017) Generalizability in the mediation effects of parental expectations on children’s cognitive ability and self-concept. J Child Family Stud 26(12):3388–3400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0836-z

Piaget J (1962) The stages of the intellectual development of the child. Bull Menn Clin 26:120–128. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291137580_The_stages_of_the_intellectual_development_of_the_child_in_Educational_Psychology_in_Context

Rice L, Barth JM, Guadagno RE, Smith GP, McCallum DM (2013) The role of social support in students’ perceived abilities and attitudes toward math and science. J Youth Adolesc 42(7):1028–1040. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9801-8

Rosenthal R, Jacobson L (1968) Pygmalion in the classroom: Teacher expectation and pupils’ intellectual development. Holt Rinehart Winston. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092211

Rozek CS, Svoboda RC, Harackiewicz JM, Hulleman CS, Hyde JS (2017) Utility-value intervention with parents increases students’ stem preparation and career pursuit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114(5):909–914. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1607386114

Sahin A, Ekmekci A, Waxman HC (2018) Collective effects of individual, behavioral, and contextual factors on high school students’ future STEM career plans. Int J Sci Math Educ 16(1):69–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-017-9847-x

Sainz M, Muller J (2018) Gender and family influences on Spanish students’ aspirations and values in stem fields. Int J Sci Educ 40(2):188–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2017.1405464

Schunk DH, Meece JR, Pintrich PR (2014) Motivation in education: theory, research, and applications (4th ed.). Higher Educ. https://doi.org/10.1037/004505

Simunovic M, Reic Ercegovac I, Burusic J (2018) How important is it to my parents? transmission of stem academic values: the role of parents’ values and practices and children’s perceptions of parental influences. Int J Sci Educ 40(9):977–995. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2018.1460696

Snyder TD, De Brey C, Dillow SA (2016) Digest of education statistics 2014, NCES 2016-006. Natl Center Educ Stat. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED565675

Sorby S, Veurink N, Streiner S (2018) Does spatial skills instruction improve STEM outcomes? The answer is ‘yes’. Learn Individ Differ 67:209–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindiff.2018.09.001

Techakosit S, Nilsook P (2018) The development of STEM literacy using the learning process of scientific Imagineering through AR. Int J Emerg Technol Learn 13(1):230–238. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v13i01.7664

The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China (2016) Release of the Core Competencies and Values for Chinese Students’ Development. http://www.scio.gov.cn/zhzc/8/4/Document/1491185/1491185.htm

Tsukazaki K, Shintoku T, Fukuzoe T (2019) Teaching ICT skills to children and the empowerment of female college students in STEM in Japan. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater Sci Eng. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/551/1/012036

Van Tuijl C, Walma VDMJH (2016) Study choice and career development in stem fields: an overview and integration of the research. Int J Technol Des Educ 26(2):159–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-015-9308-1

Voyer D, Voyer SD (2014) Gender differences in scholastic achievement: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 140:1174–1204. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036620

Wang MT (2012) Educational and career interests in math: a longitudinal examination of the links between classroom environment, motivational beliefs, and interests. Dev Psychol 48(6):1643–1657. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027247

Wang MT, Degol J (2013) Motivational pathways to stem career choices: using expectancy–value perspective to understand individual and gender differences in stem fields. Dev Rev 33(4):304–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2013.08.001

Wang MT, Degol JL (2017) Gender gap in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (stem): current knowledge, implications for practice, policy, and future directions. Educ Psychol Rev 29(1):119–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9355-x

Wang MT, Eccles JS, Kenny S (2013) Not lack of ability but more choice: individual and gender differences in STEM career choice. Psychol Sci 24:770–775. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612458937

Weber K (2012) Gender differences in interest, perceived personal capacity, and participation in stem-related activities. J Technol Educ 24(1):18–33. https://doi.org/10.21061/jte.v24i1.a.2

Yoon SY, Mann EL (2017) Exploring the spatial ability of undergraduate students: association with gender, STEM majors, and gifted program membership. Gifted Child Q 61(4):313–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986217722614

Zhan Z, Fong PSW, Mei H, Liang T (2015) Effects of gender grouping on students’ group performance, individual achievements and attitudes in computer-supported collaborative learning. Comput Hum Behav 48(c):587–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.038

Zhan Z, Shen W, Xu Z, Niu S, You G (2022b) A bibliometric analysis of the global landscape on STEM education (2004-2021): towards global distribution, subject integration, and research trends. Asia Pacific J Innov Entrep 16(2):171–203. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-08-2022-0090

Zhan Z, He W, Yi X, Ma S (2022a) Effect of unplugged programming teaching aids on children’s computational thinking and classroom interaction: with respect to Piaget’s four stages theory. J Educ Comput Res https://doi.org/10.1177/07356331211057143

Zhan Z, Li Y, Yuan X, Chen Q (2021) To be or not to be: Parents’ willingness to send their children back to school after the COVID-19 outbreak. Asia-Pac Educ Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00610-9

Zhan Z, Yao X, Li T (2022c) Effects of association interventions on students’ creative thinking, aptitude, empathy, and design scheme in a STEAM course: considering remote and close association. Int J Technol Des Educ https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-022-09801-x

Acknowledgements

We want to take this opportunity to thank all the participants in the study.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (#18BGL053).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZZ proposed the research idea and conceptualized the study, collected data, and wrote the original draft. YL collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the original draft. HM proposed the research model, wrote the original draft, and collected and analyzed the data. SL reviewed and edited the manuscript, analyzed the data, and conducted project administration. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the University. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhan, Z., Li, Y., Mei, H. et al. Key competencies acquired from STEM education: gender-differentiated parental expectations. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 464 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01946-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01946-x

This article is cited by

-

Playful learning opportunities: US children’s mathematics and literacy home learning environments

Educational Studies in Mathematics (2025)