Abstract

Applying different regression estimators on balanced panel data, this article examines the impact of human capital and income inequality on climate change in Asian countries during the period 2007–2020. Results by the GMM estimator confirm that increases in income inequality and investments in human capital exacerbate environmental degradation in Asian countries. However, among the three variables that represent human capital, only HC3 (Gross enrollment ratio for tertiary school) plays a role in reducing the impact of income inequality on emissions of carbon dioxide. In addition, the study also provides evidence on the impact of other factors on CO2 emissions such as renewable energy, economic growth, population, output in the agricultural and services sectors, trade openness, government expenditure and total investment in the economy. Besides, some important policy implications have been suggested to aim at securing sustained economic growth in Asia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the last few decades, Asia has emerged as a continent with spectacular economic growth and is a key driver of global economic growth. The economic growth of Asian countries is always at a high level of 5% to 5.5% per year (World Bank 2019). However, according to Jain-Chandra et al. (2019), since the early 1990s, the region has witnessed an increase in income inequality – an issue of interest to many economists and policymakers because of its effects on sustainable growth.

One of the consequences of income disparity is its effect on carbon dioxide emissions (Baloch et al. 2020). In order to ascertain the connection between environmental damage and inequality in income, many empirical research have been carried out in different countries. Despite the application of a variety of concepts and theories, no conclusive results could be drawn. Environmental degradation is reportedly worsened by income disparity (Baek and Gweisah 2013; Hao et al. 2016). The correlation between these factors, however, may be negative or represent a trade-off, according to certain other studies (Ali and Audi 2016; Coondoo and Dinda 2008; Ravallion et al. 2000). Galor and Moav (2004) asserted that there is no connection between inequality in income and sustainable economic development.

Many research findings on income inequality suggest a connection between it and human capital. Expanding investments in human capital is believed to make it easier for employees to find jobs, thereby reducing income inequality (Lee and Lee 2018; Shahpari and Davoudi 2014; Suhendra et al. 2020). Also significant in lowering CO2 emissions is human capital (Khan 2020; Mahmood et al. 2019; Yao et al. 2021). In order for countries, especially those in Asia, to enact appropriate policies in current situations, a deeper understanding of the linkage between human capital, inequalities in income, and emission of carbon dioxide is necessary.

According to data from the Global Carbon Project (2020), China ranked first in the list of countries that emit the most CO2 to the environment. Environmental quality issues have their roots in social issues, which are mostly caused by power and income inequality. Globally, attaining sustainable development and environmental protection has been hampered by income disparity and environmental degradation. Although the influence of income disparity on emissions of CO2 has been estimated in the available literature, short-term and long-term impacts are less considered, particularly from a continental perspective.

The linkage between human capital, income inequality, and emissions of CO2, on the other hand, has been demonstrated in earlier research. However, most of them analyzed the separate effects of each factor on CO2 emissions (Baek and Gweisah 2013; Baloch et al. 2020; Khan 2020; Wu and Xie 2020; Yao et al. 2021). The number of articles on the simultaneous impact of these two factors on environmental degradation is quite small. Typically, Eyuboglu and Uzar (2021) explained the impact mechanism of education and income distribution on the environment in Turkey using the VECM model. However, this paper only provided empirical evidence on a specific country, so it is essential to broaden the research’s scope to enrich the theory and experiment on this topic. In order to do this, our paper applied the GMM method to analyze the impact of income inequality on emissions of CO2 while considering the importance of human capital. Data was collected from 46 Asian countries from 2007 to 2020. The following are the study’s three major contributions: First, results indicate that increasing income inequality and investment in human capital have exacerbated environmental degradation in Asia. Second, the study shows that economic growth, renewable energy, population, output in the agricultural and service sectors, trade openness, government spending, and total investment have an impact on CO2 emissions. Finally, the study proposes some policy implications to limit the release of carbon dioxide and ensure sustainable economic development for the studied area.

In addition to the introduction, the study includes the following sections: Reviews of the literature are presented in the Literature review. Methodology describes an overview of both the research methods and the data. The main outcomes of the study are explained in Results and discussion. The conclusion and some related policy suggestions are presented in Conclusion.

Literature review

Theoretical framework

The concepts of income inequality have been proposed by many previous studies. Kuznets (1955) defined income inequality as a situation where only a small portion of the population has a relatively high income in a country or territory, while most people live below the average income level. According to Fletcher and Guttmann (2013), income inequality arises when there are differences in wealth and income distribution across people, groups in society, or between nations, or when there is unequal allocation to those who have equal development prospects.

The Lorenz curve structure depicted in Fig. 1 is the source of the Gini index, by far the most widely used indicator of income inequality (Atkinson 1975; Champernowne and Cowell 1998; Campano and Salvatore 2006; De Maio 2007). The cumulative percentage of the population’s total income earned is shown on the Lorenz curve. If the ''poorest'' 20% of the population made up 20% of the total income, the ''poorest'' 40% of the population made up 40% of the total income, it would follow the line of equality. As inequality goes up, the Lorenz curve departs from the line of equality. Area A divided by area A + B in Fig. 1 is the definition of the Gini coefficient. The value of the Gini coefficient ranges from 0 to 1 (or from 0% to 100%). In a society where all wealth is distributed evenly and the coefficient is 0, the Lorenz curve would follow the line of equality. The Gini coefficient will be larger the further the Lorenz curve deviates from the line of equality.

According to Boyce (1994), who made the following arguments regarding the mechanism of how income inequality impacts CO2 emissions, inequality of wealth and power is mostly to blame for environmental degradation. First, in power-based social decision-making, the rich frequently have greater rights, which enables them to benefit from actions that cause environmental disruption. Secondly, as inequality rises, the rich’s preference for the environment will grow. Thirdly, in terms of the expenses placed on the poor, inequality has a tendency to raise the value of the advantages for the rich. Research by Ravallion et al. (2000) used marginal propensity emissions (MPE) to explain the impact of income inequality on CO2 emissions. We can suppose that the poor often have greater MPEs than the rich since low-emission goods require more technology and are more expensive, which may prevent the poorest from being able to afford them. Reduced inequality thus has a tendency to hasten environmental degradation. According to a third point of view, economic behavior has a role in how inequality impacts the environment. Veblen (2009) showed that individuals enjoy using consumption to demonstrate their material financial and social standing to others. Longer workdays and ostentatious consumerism both raise energy consumption and harm the environment.

The concept of human capital has existed since Smith (1776), but this concept was still strange when economists at that time only focused on two inputs in production: capital and machinery. By the 60 s of the 20th century, Mincer (1958), Becker (1964), and Schultz (1961) were considered to have started the interest in the concept of human capital. These studies argued that the factors that form human capital are the skills and knowledge that workers acquire. More recently, Arthur and Sheffrin (2003) defined human capital as the degree of skill and knowledge that goes into the ability of labor to create economic value. It is described by Rodriguez and Loomis (2007) as the skills, abilities, knowledge, and and personality traits of a person that enables the development of individual, social, and economic well-being. According to Becker and Murphy (2009), means of production like machines and factories share similarities with the skills and information that people get via investments in their education, on-the-job training, and other sorts of experience.

Human capital is a key factor of economic development (Romer 1986; Lucas 1988; Jones and Manuelli 1990). It is claimed that a nation with a highly educated population can utilize its voice to pressure the government to improve the environment (Brasington and Hite 2005). In addition, it is possible to anticipate that human resource development will support technical innovation, which can lead to more effective energy usage and a reduction in CO2 emissions from energy use (Li et al. 2022). In a similar vein, it is claimed that households with greater levels of education are more prepared to spend more on cleaner modern cooking fuels compared to conventional cooking fuels (Wassie et al. 2021). In addition, it has been acknowledged that human capital development influences people’s understanding of environmental welfare, inspiring them to convert to clean energy in order to lower CO2 emissions (Alvarado et al. 2021). While improving human resources is great for reducing CO2 emissions, it can also increase releases by promoting economic growth (Haini 2021).

Empirical evidence

Economists have given much thought to the connection between inequality in income and emissions of carbon dioxide. They are positively correlated, according to several research. In their study of the linkage between CO2 emissions and GDP, Padilla and Serrano (2006) demonstrated how differences in income between nations caused differences in the distribution of emissions from 1971 to 1999. While emissions inequality between nations categorized by income has increased, this inequality has marginally diminished. The correlation between growth, inequality, and the environment in the US from 1967 to 2008 was examined by Baek and Gweisah (2013). The results of using the ARDL approach revealed that in both long and short terms, more equitable income distribution in the US improves the quality of the environment. Additionally, while energy use has a negative influence on the environment, economic growth has a favorable benefit. Zhang and Lin (2012) also examined this relationship in the period 1995–2010 in China. Using several methods such as FE, FGLS, PCSE, findings stated that rising CO2 emissions are caused by rising income levels, and the influence of income growth on CO2 emissions differs between regions in China. In particular, CO2 emissions in the East area are more affected by income disparity than in the West area. Research by Baloch et al. (2020) also came to a similar finding. This paper analyzed the correlation between CO2 emissions, poverty, and income inequality in 40 African economies by the GMM method. Using CO2 emissions as the dependent, the findings demonstrated that rising income disparity causes a rise in emissions of carbon dioxide. Additionally, studied countries are experiencing a rise in environmental degradation as a result of a higher poverty. Using Driscoll Kraay regression, Yang et al. (2022) investigated the connections between CO2 emissions, inequality in income and institutional quality in 42 developing nations in 33 years since 1984. Findings confirmed that carbon dioxide emissions are positively correlated to income inequality.

In addition, some studies found that income inequality is negatively correlated with emissions of CO2. Kusumawardani and Dewi (2020) used the ARDL model to analyze the impact of GDP per capita, income inequality, dependence ratio and urbanization rate on emissions of carbon dioxide in Indonesia from 1975 to 2017. The results indicated that inequality in income has an impact on reducing CO2 emissions and this linkage is dependent on per capita GDP levels. This study has the same conclusion as Akram and Hamid (2015). Wu and Xie (2020) applied FMOLS and DOLS models to examine the correlation between income inequality and per capita CO2 emissions in 78 countries from 1990 to 2017. The results showed that increased income inequality encourages lower emissions in high-income non-OECD and OECD countries, whereas the effect is short-lived in low-income non-OECD nations. Additionally, the ARDL model results showed that while CO2 emissions are not significantly impacted by inequality in income in the short term, they are influenced favorably by per capita GDP. Similarly, research by Wan et al. (2022) on a dataset of 217 countries found that high income inequality increases R&D spending, which leads to a reduction in CO2 emissions.

Research by Uddin et al. (2020) gave different results in the two research periods in the G7 countries from 1870 to 2014. The study used a non-parametric model, and the independent variables included income inequality, per capita GDP, financial development, agricultural share of GDP, population density and the dependent variable of CO2 emissions. Findings suggested that inequality in income increased CO2 emissions from 1870 to 1880, but from 1950 to 2000, the impact was negative.

The contribution of human capital to the reduction in CO2 emissions is also examined in many studies. Mahmood et al. (2019) studied on economic growth, renewable energy, human capital and CO2 emissions in the period 1980–2014 in Pakistan. Applying the 3SLS method, findings demonstrated how income and renewable energy combine to cause emissions of carbon dioxide. Additionally, the level of emissions were increased by trade openness but decreased by human capital. Khan (2020) argued that the degree of human capital affects how much development in the economy reduces CO2 emissions. More education will first encourage the use of non-renewable resources and raise pollution emissions as human capital rises from the low level. Enrolling in private tutoring, however, lowers CO2 emissions when a specific school threshold is reached by raising environmental awareness and promoting the adoption of eco-friendly technology. The result implied that increased education is necessary to reduce environmental pollution and ensure the sustainable economic development. Nathaniel et al. (2021) explored the links between environmental degradation, globalization, natural resources, and urbanization in Caribbean and Latin American economies in 1990–2017 period. Using AMG, CCEMG and DK methods, the authors proved that human capital plays a regulatory role in promoting the sustainability of urbanization in LACC countries. Also studying the linkage between human capital and carbon dioxide emissions, Yao et al. (2021) applied the STIRPAT model on the Chinese dataset for the period 1997–2016. CO2 emissions were found to be negatively correlated with human capital in long-term due to the effects of young employees and those with advanced human capital. In particular, the results confirmed that an increase in the average number of students attending school in a year reduces CO2 emissions by 12%. This negative association can manifest through technology effects and limited energy efficiency improvements in the manufacturing sector. The effect of human capital on carbon dioxide emissions in ASEAN economies was also emphasised by Haini (2021). Through fixed-effects model, findings showed that human capital increases emissions of CO2. Mixed findings, however, supported the idea that human capital lowers carbon dioxide emissions for the manufacturing sector and other industries. Because it impacts indirectly growth, the formation of human capital can cause a rise in CO2 emissions. However, human capital can improve an economy’s potential for absorption, improving the efficiency of modern technology to reduce potential emissions. Applying the Pooled Mean Group model, Isiksal et al. (2022) claimed that CO2 emissions are negatively affected by human capital in both long term and short term.

In addition to its effect on the environment, human capital is believed to impact income inequality. Increases in human and physical capital, according to Shahpari and Davoudi (2014), can lower the Gini coefficient and enhance the equality of income distribution. In agreement with this point of view, Lee and Lee (2018) claimed that increasing access to education is a crucial component of lowering income disparity and, consequently, inequality in educational outcomes. Income inequality can be decreased by public policies that increase social benefits and stable prices, while educational inequality can be decreased through public spending on education. The idea that human capital and income inequality have a negative connection was also substantiated by Suhendra et al. (2020).

By different approaches, previous studies have demonstrated the correlation between human capital, income inequality and emissions of carbon dioxide. However, most of them analyzed the separate effects of each factor on CO2 emissions. There are very few papers that study the simultaneous impact of these two factors on environmental degradation. Recently, research by Eyuboglu and Uzar (2021) explained the impact mechanism of education and income distribution on the environment. Applying the VECM model to find the link between higher education and CO2 emissions in Turkey, this article proved that increasing the quality of education has a positive effect on the improvement of income distribution, thereby indirectly improving environmental quality. However, the paper has only been conducted within Turkey, so it is essential to broaden the research scope to enrich the theory and experiment on this issue. Therefore, our study attempts to narrow this gap by focusing on analyzing the impact of income inequality on CO2 emissions on the basis of considering the role of human capital, and adding almost complete Asian countries data. Furthermore, the study also considers other factors affecting CO2 emissions in the 2007–2020 period, using the GMM method on the balanced panel dataset to solve the endogenous issues and ensure the effectiveness of the estimates.

Methodology

Dataset and variables

Examining the connections between CO2 emissions, human capital, and income inequality in Asian countries is the goal of this study. The variables of the research model include:

Dependent variable: CO2 emissions (CO2)

According to the studies of Baloch et al. (2020), Chen et al. (2020), Pao and Tsai (2010), Yao et al. (2021), CO2 emission is used to measure climate change. It is measured by the number of tons of CO2 that each country in Asia emits.

Independent variables

-

Income inequality (GINI)

The degree of income inequality between resident classes is frequently expressed using the Gini coefficient. It can also be used to illustrate the degree of inequality between the rich and the poor. The prerequisite that no person has a negative net income must be satisfied in this instance before using the Gini index. It can accept any values in the range of 0% and 100%, or 0 and 1. As opposed to absolute income inequality when the Gini index is 1, which is represented by one individual having all the income while everyone else has none, absolute income equality is indicated by a coefficient of zero, which means that everyone has the same level of income. Thus, the closer the Gini coefficient approaches 1, the greater the income inequality of a country and vice versa. This variable is used based on Boyce (1994), Chen et al. (2020), Uzar and Eyuboglu (2019).

-

Human capital (HC1, HC2, HC3)

The three key categories of the standard for evaluating human capital are output, income, and cost. Examples of the first approach include school enrollment ratios, academic results, adult literacy, and the median amount of years spent in school. The second approach is linked to the personal advantages that follow from investments in education and training, whereas the third approach depends on the estimation of the knowledge acquisition cost (Kwon 2009). In this research, we evaluate human capital by output-based approach because of the availability of data. The variables that represent formal education specifically include Gross enrollment ratios for primary school (HC1), secondary school (HC2), and tertiary school (HC3). They are also the measurement used in the studies of Khan (2020), Yao et al. (2021). Using three different variables to measure human capital helps the study to better explain the role of each level of education on environmental quality.

Control variables

These variables are incorporated in the research model to better clarify factors affecting climate change in Asian countries, including: per capita GDP (LnGDP), Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), Population (POP), Renewable Energy (ENG), Services sector output (S), Agricultural sector output (AG), Manufacturing sector output (MN), Trade Openness (TO), Total Investment (INV) and Government Expenditure (GEX).

The specific measurement and data collection methods of these variables are presented in Table 1 below. All variables are expressed as percentages except CO2 emissions, per capita GDP, and population which are converted into natural logarithms form to reduce skewness between variables and increase normalization of the dataset.

For Asian countries from 2007 to 2020, balanced panel data were used in the study. 46 countries with 644 observations were chosen after removing those with insufficient data for the research paper (see Appendix A for details). The World Bank (WB), Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), Our World In Data (OWID), and International Monetary Fund (IMF) are the sources of the data. The descriptive statistics for all variables in the model are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2 shows that the empirical model has an average CO2 emission value of −0.7364 (in natural logarithm), with a range of −6.3023 to 4.6698. HC3, which spans from 2% to 116%, is the lowest (37.3134%) of the variables that indicate human capital. Due to the participation of over- and under-aged pupils due to early or late enrollments, grade repetition, and other factors, HC1, HC2, and HC3 can exceed 100%. The Gini coefficient has a mean value of 0.3912 and a range of 0.1516 to 0.5199. Per capita GDP (in natural logarithm) spans from 6.2320 to 30.2943, with a mean value of 24.0145. The range of the FDI index is 0.3715 to 2.8013. Net capital inflow to GDP serves as the FDI variable’s data in this study. A negative value denotes a decrease in new inflows from previous inflows.

Model

Following the previous studies summarized in the previous section, the panel data regression model to investigate the effect of income inequality and human capital on CO2 emission is represented by Eq. (1) below:

in which i = 1, 2,.., N; t = 1, 2, …, T; N denotes the total number of studied countries, T represents the total number of years, eit is the error term.

The data collection gathered for the investigation is processed in this study using Stata 17.0 software and balanced panel data estimate techniques. For the static panel data model, the three most commonly used methods are Pooled ordinary least squares (Pooled – OLS), Fixed effect model (FEM), and Random effect model (REM). The Hausman test and F test are used to select the most suitable model. After that, the Feasible Generalized Least Squares (FGLS) and two-step system Generalized method of moments (GMM) estimators are applied to handle the endogeneity and heteroscedasticity. According to Arellano and Bond (1991) and Ganda (2019), the GMM estimator is appropriate when N > T. In this paper, we have N = 46 while T = 14, so the GMM estimator is suitable. Additionally, Sarafidis et al. (2009) showed that the system GMM, based solely on partial instruments composed of the regressors, can be a reliable replacement for the traditional GMM under heterogeneous error cross-section dependence. The GMM model is as follow:

Finally, this analysis suggests that in addition to their direct effects on CO2 emissions, income disparities and human capital may interact. To test the moderation impact of human capital and income inequality on emissions of CO2, interaction terms (Gini*HC1, Gini*HC2, Gini*HC3) are added in Eq. (3) as follows:

If there is a statistically significant association between the interaction variable and the dependent variable, the moderating impact would be discovered (Memon et al., 2019). Therefore, we anticipate that the moderating role of human capital will be confirmed in the study if the coefficient is statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Preliminary tests

The results of panel unit root tests using ADF (augmented Dickey–Fuller), LLC (Levine-Lin-Chu) and PP (Phillips–Perron) in Table 3 show that all series are stationary at the first-order differenced at 1% significant level.

In the next step, we applied the cross-sectional depencence test which suggested by Pesaran (2004). Results are shown in Table 4.

The CD test results show that the null hypothesis has been rejected at the one percent level. The significant economic and financial ties between several of these countries can be used to explain the findings, which show that countries are cross-sectionally dependent. Additionally, this result suggests that cross-sectional dependence should be considered when using panel unit root tests. As a result, we proceed to assess the variables’ characteristics of stationarity using Pesaran (2003)’s cross-sectional dependence-aware second-generation CADF unit root test. The outcomes are shown in Table 5.

Research results

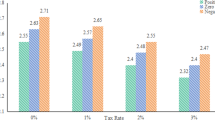

Table 6 presents the regression results for model (1). The estimation outcomes for the Pooled OLS, FEM, REM, and FGLS, respectively, are shown in columns 1, 2, 3, and 4 of the table. The Hausman test’s findings indicate that FEM is the most appropriate model. The test results do, however, suggest that the FEM has heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation. We proceed with the FEM regression using the xtgls command with the panels (heteroskedastic) and corr (ar1) arguments to correct them. Based on the model (2)’s results in column 5, there are eleven variables which have significant impact on CO2 emissions including GINI, GDP, HC1, HC3, ENG, LnPOP, S, AG, GEX, TO and INV. Three variables – HC2, MN, and FDI – are not statistically significant. Additionally, with a significance level of 1%, the correlation between the current and previous CO2 emissions is relatively high (0.959), suggesting that past CO2 emissions significantly influenced contemporary climate change in Asian nations. Since the value of AR2 test is higher than 5% and the p-value of Hansen test is 1.000, the hypothesis H0 – that the model has no autocorrelation – is accepted.

Regarding the effect of income inequality on emissions of CO2 when considering the role of human capital, the results in column (6) of Table 6 show that GiniHC3’s coefficient is positive at a significant level of 1%. That means the gross enrollment ratio for tertiary school has reduced the effect of income inequality on the amount of CO2 released into the environment. Table 7 summarizes the impact of factors on CO2 emissions found in this study.

Discussion

Income inequality (GINI)

At a significant level of 1%, the coefficient of income inequality is positive, demonstrating that income inequality contributes to environmental damage. Because of the increase in income inequality, the gap between the rich and the poor is widening. According to the World Economic Forum 2019, low-income individuals will tend to be more extreme - they tend to ask their countries to separate from international organizations and relations to promote development. Besides, they are not motivated to contribute to the costs of reducing climate change. For countries that are in the development stage and are often affected by climate change, the transition to green energy is even more difficult when the costs need to be prioritized for social security rather than change. The effects of climate change and its uneven repercussions can be reduced by reducing emissions, but mitigation measures cannot disregard their own effects on inequality. When they affect energy or food prices, mitigation policies can also slow energy access and affect the poorest, who spend more of their incomes on these goods (Taconet et al., 2020). Moreover, income inequality also leads to migration, creating an environmental pollution burden for host countries. This result conforms to Boyce (1994); Uddin et al. (2020); Uzar and Eyuboglu (2019).

Human capital

The coefficients of HC1 and HC3 are positive at significance levels of 5% and 1%, respectively. This can be explained that human capital is a key factor in the economic growth of each country. According to the EKC hypothesis, rising economic activity brought on by more human capital may result in increased carbon emissions. Similar conclusions have been drawn in earlier research, which contends that because of rising energy demand and consumption, environmental degradation is strongly tied to economic activity (Haini 2021; Inglesi-Lotz 2016). The increase in the Gross enrollment ratio for primary school shows that the population is also increasing, causing consequences for the environment. Meanwhile, an increase in tertiary rate causes students to move from rural areas to urban areas will have environmental consequences through problems such as traffic and overpopulation. This result does not mean that countries should reduce investment in human capital, but on the contrary, the more a country has to increase investment in human capital. Maji et al. (2019) has shown that in the long run, carbon emissions may be negatively impacted by human capital. More people are aware of climate change as their education level rises, which means that they have initiatives and are willing to support policies to reduce environmental degradation. This helps stimulate exploration and creation of new types of energy, thereby reducing environmental degradation.

When considering the role of human capital, findings show that the gross enrollment ratio for tertiary education has reduced the effect of income inequality on CO2 emissions. This proves that once the education level of employee increases, especially when they have a degree, they will have more job opportunities, making it easier for them to earn more money, and income inequality will be reduced. As income increases and income distribution becomes more equitable, consumers tend to be more interested in environmentally friendly goods, thereby improving environmental quality. Conversely, rising inequality will negatively impact the diffusion of innovations, harming the development of environmental technology (Vona and Patriarca 2011). These outcomes agree with the conclusion of Eyuboglu and Uzar (2021).

In addition, some control variables included in the model also show an impact on CO2 emissions.

Per capita GDP (GDP)

At a 1% significance level, findings imply that GDP positively affects climate change. According to the EKC theory, environmental deterioration rises with economic growth. Asia is a continent with many developing countries along with populous countries such as China and India, so there is a positive linkage between GDP and CO2 emissions. This result conforms to Lee et al. (2016); Al-Mulali et al. (2015). However, also according to the EKC theory, when economic growth reaches its threshold, the environmental degradation will be reduced, then the economy will change to a service economy. At this time, people tend to spend more on waste treatment, because each individual wants to improve the environmental quality by consuming more renewable energy and the quality of the environment starts to improve with economic growth.

Renewable energy (ENG)

The coefficient of renewable energy has a negative value at the 1% level of significance, showing that renewable energy helps to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. This could be a result of the fact that sources of renewable energy are thought to be environmentally friendly and emit little or no air pollution. Additionally, they serve as a driving force for lowering greenhouse gas emissions. To preserve a clean and safe environment, several nations have also begun to invest in renewable energy sources. This finding is compatible with Raza et al. (2020).

Population (LnPOP)

The results show that when the total population grows by 1%, the CO2 emissions will grows by 1.824%. This is explained that when the population increases, it will lead to a burden on the population or the transport industry. The more people and vehicles, but the majority of vehicles now use gas and gasoline, the more it will increase environmental pollution. This result was also found in Baloch et al. (2020), Grunewald et al. (2017). Population growth is not only through the birth rate but also through the labor force coming to the cities to work. Although businesses need labor to expand production and growth, exceeded labor will lead to increased production activities and increased CO2 emissions.

Services sector output (S)

The coefficient of S is negative at the 1% significance level, indicating that the service sector can reduce CO2 emissions. The service industry does not go through the production process, products and services are directly on the market, besides there are also environmental services to help the environment improve even better. This has also been demonstrated in Akram and Hamid (2015).

Agricultural sector output (AG)

The coefficient of AG has a negative value at a significant level of 5%, indicating that agriculture sector decreases CO2 emissions, which is consistent with Akram and Hamid (2015). This can be attributed to efforts by countries to promote rural landowners to pursue environmentally friendly practices such as lowering the number of fertilizers and pesticides used on crops, changing the livestock and fertilizer management practices, and planting trees or grasses.

Trade openness (TO)

Findings also express a negative correlation between trade openness and emissions of carbon dioxide, which are conform to Al-Mulali et al. (2015) and Shahbaz et al. (2013). The scale effect claims that trade liberalization boosts the country’s export volume which leads to economic growth. This improves a country’s income level, causing it to import eco-friendly technology to raise its output level. Moreover, trade openness is a source of competition among local producers, which incentivizes them to use advanced technology to reduce their per-unit cost and thus emit less CO2 during production.

Total investment (INV)

The estimated results show that when total investment increases by 1%, CO2 emissions will decrease by 0.432%. This result is inconsistent with the Al-Mulali et al. (2015). This could be explained that investors are trying to focus their capital on slowing down environmental destruction through green projects or renewable energy systems.

Conclusion

This article analyzed the effect of income inequality and human capital on CO2 emissions in Asian countries in the period 2007–2020. Applying different regression methods, the study confirmed a positive impact of income inequality and human capital on climate change in Asia. In addition, other factors that also affect CO2 emissions positively, including per capita GDP and population, while renewable energy, services and agriculture sectors output, trade openness, the total investment and government expenditure will help mitigate climate change in Asia.

The research suggests some policy recommendations to limit CO2 emissions in Asian countries while ensuring economic growth. Countries should develop fiscal policies that are both inclusive and successful in redistributing income. Government expenditure and tax policies must strike a balance between population benefits and growth objectives. An effective redistribution of income will be made possible by increasing public spending on social security programs and other public services. In addition, countries need to strengthen the development of a full and transparent labor market through policies to create jobs, especially policies to protect workers’ rights, policies to encourage labor enterprises that are labor-intensive and create decent jobs (formal sector jobs).

The findings also demonstrate that climate change is a concern for Asian countries. Therefore, policymakers need to focus on investing in human capital - considered an important factor in each country. By enabling everyone to take part in economic progress and profit from it, more investments in human capital will contribute to addressing social instability and reducing inequality.

Countries also need to have appropriate economic development guidelines and policies for both economic growth and the application of a green economy. In addition, the agricultural sector should continue to develop and enforce policies toward green agriculture, limiting the use of chemicals and increasing organic products. The government also needs to consider policy issues in population management, managing the number of employees of enterprises to avoid redundancy or excessive concentration in urban areas. Reducing the birth rate is not a panacea for climate change, but it does cut future carbon emissions in an effective, simple, and meaningful way in the long run. In addition, a highlight in the current climate change mitigation effort is increasing the use of renewable energy sources including solar, water, and wind energy. Countries should gradually change the way of electricity production from coal and oil sources to using "clean" materials that can reduce CO2 emissions and make the best use of energy sources from the sun, wind, and water to produce electricity.

In addition to these important research findings, this paper has some limitations. One of them is that there are only three composite human capital development indicators that examine the link between human capital and emissions of CO2. Investigating how various aspects of human capital, for example, adult education or skilled labor, affect CO2 emissions will be an interesting topic. In addition, the scope of the study is quite narrow when considering only 46 Asian countries. Future studies can expand the scope of research globally or compare developing and developed countries to enrich the theory of the correlation between inequality in income, climate change, and human capital.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DG03CB.

References

Akram N, Hamid A (2015) Climate change: A threat to the economic growth of Pakistan. Prog Develop Stud 15(1):73–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464993414546976

Ali A, Audi M (2016) The impact of income inequality, environmental degradation and globalization on life expectancy in Pakistan: an empirical analysis

Al-Mulali U, Saboori B, Ozturk I (2015) Investigating the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis in Vietnam. Energy Policy 76:123–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.11.019

Alvarado R, Deng Q, Tillaguango B, Méndez P, Bravo D, Chamba J, Ahmad M (2021) Do economic development and human capital decrease non-renewable energy consumption? Evidence for OECD countries. Energy 215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.119147

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58(2):277–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297968

Arthur S, Sheffrin SM (2003) Economics: Principles in action. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey

Atkinson AB (1975) Economics of Inequality. Clarendon Press

Baek J, Gweisah G (2013) Does income inequality harm the environment?: Empirical evidence from the United States. Energy Policy 62:1434–1437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.07.097

Bakhsh K, Latif A, Ali R et al. (2020) Relationship between adaptation to climate change and provincial government expenditure in Pakistan. Environ Sci Poll Res 28:8384–8391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-11182-4

Baloch MA, Khan SUD, Ulucak ZŞ et al. (2020) Analyzing the relationship between poverty, income inequality, and CO2 emission in Sub-Saharan African countries. Sci Total Environ 740:139867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139867

Becker GS (1964) Human capital

Becker GS, Murphy KM (2009) Social economics: Market behavior in a social environment. Harvard University Press

Boyce JK (1994) Inequality as a cause of environmental degradation. Ecol Econ 11(3):169–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/0921-8009(94)90198-8

Brasington DM, Hite D (2005) Demand for environmental quality: a spatial hedonic analysis. Regional Sci Urban Econ 35(1):57–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2003.09.001

Campano F, Salvatore D (2006) Income Distribution: Includes CD. Oxford University Press

Champernowne DG, Cowell FA (1998) Economic inequality and income distribution. Cambridge University Press

Chen J, Xian Q, Zhou J et al. (2020) Impact of income inequality on CO2 emissions in G20 countries. J Environ Manag 271:110987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110987

Coondoo D, Dinda S (2008) Carbon dioxide emission and income: A temporal analysis of cross-country distributional patterns. Ecol Econ 65(2):375–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.07.001

De Maio FG (2007) Income inequality measures. J Epidemiol Community Health 61(10):849–852. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2006.052969

Demena BA, Afesorgbor SK (2020) The effect of FDI on environmental emissions: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Energy Policy 138:111192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111192

Eyuboglu K, Uzar U (2021) A new perspective to environmental degradation: the linkages between higher education and CO2 emissions. Environ Sci Poll Res 28:482–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09414-8

Fletcher M, Guttmann B (2013) Income inequality in Australia. Econ Round-Up 2:35–54

Galor O, Moav O (2004) From physical to human capital accumulation: Inequality and the process of development. Rev Econ Stud 71(4):1001–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/0034-6527.00312

Ganda F (2019) The environmental impacts of financial development in OECD countries: a panel GMM approach. Environ Sci Poll Res 26(7):6758–6772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04143-z

Global Carbon Project (2020) Global Carbon Atlas, available at: https://globalcarbonatlas.org/emissions/carbon-emissions/ (last access: 12 August 2022)

Grunewald N, Klasen S, Martínez-Zarzoso I et al. (2017) The trade-off between income inequality and carbon dioxide emissions. Ecol Econ 142:249–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.06.034

Haini H (2021) Examining the impact of ICT, human capital and carbon emissions: Evidence from the ASEAN economies. Int Econ 166:116–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2021.03.003

Hao Y, Chen H, Zhang Q (2016) Will income inequality affect environmental quality? Analysis based on China’s provincial panel data. Ecol Indicators 67:533–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.03.025

Inglesi-Lotz R (2016) The impact of renewable energy consumption to economic growth: A panel data application. Energy Econ 53:58–63

Isiksal AZ, Assi AF, Zhakanov A, Rakhmetullina SZ, Joof F (2022) Natural resources, human capital, and CO2 emissions: Missing evidence from the Central Asian States. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29(51):77333–77343

Jain-Chandra S, Kinda T, Kochhar K et al. (2019) Sharing the growth dividend: Analysis of inequality in Asia. International Monetary Fund

Jones LE, Manuelli R (1990) A convex model of equilibrium growth: Theory and policy implications. J Political Econ 98(5):1008–1038. https://doi.org/10.1086/261717

Khan M (2020) CO2 emissions and sustainable economic development: New evidence on the role of human capital. Sustainable Develop 28:1279–1288. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2083

Kusumawardani D, Dewi AK (2020) The effect of income inequality on carbon dioxide emissions: a case study of Indonesia. Heliyon 6(8):e04772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04772

Kuznets S (1955) Economic growth and income inequality. Am Econ Rev 45(1):1–28

Kwon DB (2009) Human capital and its measurement. In The 3rd OECD world forum on “statistics, knowledge and policy” charting progress, building visions, improving life (pp. 27-30)

Lee JW, Lee H (2018) Human capital and income inequality. J Asia Pacific Econ 23:554–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2018.1515002

Lee M, Villaruel ML, Gaspar RE (2016) Effects of temperature shocks on economic growth and welfare in Asia. Resources Environ Econ 2:158–171. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2894767

Li S, Yu Y, Jahanger A, Usman M, Ning Y (2022) The impact of green investment, technological innovation, and globalization on CO2 emissions: evidence from MINT countries. Front Environ Sci 156. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.868704

Lorenz MO (1905) Methods of measuring the concentration of wealth. Publ Am Stat Assoc 9(70):209–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/15225437.1905.10503443

Lucas Jr RE (1988) On the mechanics of economic development. J Monetary Econ 22(1):3–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7

Mahmood N, Wang Z, Hassan ST (2019) Renewable energy, economic growth, human capital, and CO2 emission: an empirical analysis. Environ Sci Poll Res 26:20619–20630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-05387-5

Maji IK, Sulaiman C, Abdul-Rahim AS (2019) Renewable energy consumption and economic growth nexus: A fresh evidence from West Africa. Energy Rep 5:384–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2019.03.005

Memon MA, Cheah JH, Ramayah T, Ting H, Chuah F, Cham TH (2019) Moderation analysis: issues and guidelines. J Appl Struct Equ Model 3(1):1–11

Mincer J (1958) Investment in human capital and personal income distribution. J Political Econ 66(4):281–302

Nathaniel SP, Nwulu N, Bekun F (2021) Natural resource, globalization, urbanization, human capital, and environmental degradation in Latin American and Caribbean countries. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28:6207–6221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-10850-9

Padilla E, Serrano A (2006) Inequality in CO2 emissions across countries and its relationship with income inequality: a distributive approach. Energy policy 34(14):1762–1772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2004.12.014

Pao HT, Tsai CM (2010) CO2 emissions, energy consumption and economic growth in BRIC countries. Energy policy 38(12):7850–7860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.08.045

Pesaran MH (2003) Estimation and inference in large heterogenous panels with cross section dependence. Available at SSRN 385123

Pesaran MH (2004) General diagnostic tests for cross section dependence in panels. Available at SSRN 572504

Ravallion M, Heil M, Jalan J (2000) Carbon emissions and income inequality. Oxford Econ Papers 52(4):651–669. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/52.4.651

Raza SA, Shah N, Khan KA (2020) Residential energy environmental Kuznets curve in emerging economies: the role of economic growth, renewable energy consumption, and financial development. Environ Sci Pollut Res 27:5620–5629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-06356-8

Rodriguez JP, Loomis SR (2007) A new view of institutions, human capital, and market standardisation. Educ, Knowledge & Econ 1(1):93–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496890601128357

Romer PM (1986) Increasing returns and long-run growth. J Political Econ 94(5):1002–1037

Sarafidis V, Yamagata T, Robertson D (2009) A test of cross section dependence for a linear dynamic panel model with regressors. J Econometrics 148(2):149–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2008.10.006

Schultz TW (1961) Investment in human capital: reply. Am Econ Rev 51(5):1035–1039

Shahbaz M, Tiwari AK, Nasir M (2013) The effects of financial development, economic growth, coal consumption and trade openness on CO2 emissions in South Africa. Energy Policy 61:1452–1459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.07.006

Shahpari G, Davoudi P (2014) Studying effects of human capital on income inequality in Iran. Procedia-Social Behav Sci 109:1386–1389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.641

Smith A (1776) in Campbell, Skinner, and Todd (Eds), An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Clarendon Press, Oxford, printed 1976

Suhendra I, Istikomah N, Ginanjar RAF et al. (2020) Human Capital, Income Inequality and Economic Variables: A Panel Data Estimation from a Region in Indonesia. J Asian Finance, Econ, Business 7(10):571–579. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no10.571

Taconet N, Méjean A, Guivarch C (2020) Influence of climate change impacts and mitigation costs on inequality between countries. Clim Change 160:15–34

Uddin MM, Mishra V, Smyth R (2020) Income inequality and CO2 emissions in the G7, 1870–2014: Evidence from non-parametric modelling. Energy Econ 88:104780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104780

Uzar U, Eyuboglu K (2019) The nexus between income inequality and CO2 emissions in Turkey. J Clean Prod 227:149–157

Veblen T (2009) The Theory of the Leisure Class. Oxford University Press

Vona F, Patriarca F (2011) Income inequality and the development of environmental technologies. Ecol Econ 70(11):2201–2213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.06.027

Wan G, Wang C, Wang J, Zhang X (2022) The income inequality-CO2 emissions nexus: Transmission mechanisms. Ecological Economics 195

Wassie YT, Rannestad MM, Adaramola MS (2021) Determinants of household energy choices in rural sub-Saharan Africa: An example from southern Ethiopia. Energy 221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.119785

World Bank (2019) The World Bank Annual Report 2019: Ending Poverty, Investing in Opportunity

Wu R, Xie Z (2020) Identifying the impacts of income inequality on CO2 emissions: empirical evidences from OECD countries and non-OECD countries. J Cleaner Produc 277:123858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123858

Yang B, Ali M, Hashmi S H, Jahanger A (2022) Do income inequality and institutional quality affect CO2 emissions in developing economies? Environ Sci Pollut Res 29(28):42720–42741

Yao Y, Zhang L, Salim R et al. (2021) The effect of human capital on CO2 emissions: Macro evidence from China. Energy J 42. https://doi.org/10.5547/01956574.42.6.yyao

Yin Y, Xiong X, Hussain J (2021) The role of physical and human capital in FDI-pollution-growth nexus in countries with different income groups: a simultaneity modeling analysis. Environ Impact Assess Rev 91:106664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106664

Zhang C, Lin Y (2012) Panel estimation for urbanization, energy consumption and CO2 emissions: A regional analysis in China. Energy Policy 49:488–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.06.048

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge being supported by the University of Finance - Marketing, Viet Nam.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Oanh, T.T.K’s tasks on the article development: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Data curation, Writing-Reviewing and Editing. Ha, N.T.H’s tasks on the article development: Investigation, Software, Writing-Original draft preparation, Resources. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oanh, T.T.K., Ha, N.T.H. Impact of income inequality on climate change in Asia: the role of human capital. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 461 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01963-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01963-w

This article is cited by

-

Income inequality in the face of climate change: an empirical investigation on unequal nations, vulnerable regions and India

SN Business & Economics (2024)