Abstract

The well-being of older adults is significantly influenced by their adult children, especially in countries with less developed welfare systems. We aim to examine the relationship between children’s intergenerational support, children’s socioeconomic status and the well-being of older adults, as well as compare the differences among various elderly groups. The data in our research are from the 2014 China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey. The survey covered 29 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities in China with 9146 valid samples. We adopted descriptive statistical analysis and structural equation modeling to analyze the data, and the bootstrap method to test the mediating effects. Our results indicate that the children’s education level and intergenerational support do not significantly affect the well-being of all groups of older adults in China. However, the financial conditions of adult children have a significant and direct impact on the well-being of all groups of older adults. From one child to multiple children, the impact of children’s financial condition on the well-being of older adults is 0.360, 0.452, 0.412 in three urban groups and 0.496, 0.468, 0.443 in three rural groups, specifically. The influence of adult children’s financial conditions on the well-being of all groups of older adults in China is significant, surpassing that of children’s education level and intergenerational support. Moreover, the impact of children’s socioeconomic status on the well-being of older adults is primarily through direct effects, with minimal intervention from intergenerational support. For older adults in China, "whether my children are living well" is more important than "what they could give me".

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the global population ages rapidly, the well-being of older adults has consistently remained one of the primary concerns of the international community (Cheng and Chan, 2006). Children have a significant impact on the well-being of their parents in old age (Zimmer et al., 2007; James et al., 2009; Paul and Tamara, 2006), and this influence is particularly evident in countries where intergenerational co-residence is prevalent or where welfare systems are not well-developed (Torssander, 2013).

Existing research on the relationship between the well-being of older adults and their adult children primarily focuses on two aspects: intergenerational support and the socioeconomic status of adult children. Specifically, the literature on intergenerational support from adult children mainly encompasses three dimensions: financial support, care support, and spiritual support (Peng et al., 2015; Xu, 2017). Numerous studies have shown that financial support from adult children is widely believed to effectively enhance the health and life satisfaction of older adults (Sun, 2004; Silverstein and Cong et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2011). Additionally, household assistance and spiritual support have also been found to promote the well-being of older adults (Chen and Silverstein, 2000; Cong and Silverstein, 2012; Peng et al., 2015). However, a minority of scholars have pointed out that excessive financial support, daily care, and overconcern from adult children may accelerate the decline of older adults’ self-care abilities and even undermine their self-esteem. This can lead to feelings of helplessness, failure, and guilt, ultimately negatively impacting their overall well-being. (Abolfathi et al., 2014).

There has been relatively little research on the impact of adult children’s socioeconomic status on the well-being of older adults. Among the existing studies, attention has primarily focused on the effects of adult children’s educational attainment on the health of their aging parents in different regions, such as Taiwan (Zimmer et al., 2002; Zimmer et al., 2007; Lee, 2017), Sweden (Torssander, 2013), Mexico (Yahirun et al., 2016; Yahirun et al., 2017), and the United State (Friedman and Mare, 2014). Studies on the relationship between adult children’s income levels and the well-being of older adults are even scarcer. Torssander (2014) and Brooke et al. (2017) have both confirmed that adult children’s income level is an important factor influencing the health and well-being of older adults. Torssander (2013) has pointed out that the impact of adult children’s socioeconomic status on the health of older adults is more pronounced in countries where co-residence with adult children is more prevalent, and where the welfare system is less developed. Researchers generally believe that the socioeconomic status of children has a positive impact on the well-being of older adults. The explanation for this conclusion is largely based on the logic that adult children with higher socioeconomic status are more likely to provide various forms of support to their parents, thereby improving the well-being of older adults (Bernheim et al., 1985; Zhilei Shi, 2015; Yahirun et al., 2017). Nevertheless, whether this is indeed the case remains to be verified.

Existing literature has conducted systematic studies on the effects of adult children’s intergenerational support and socioeconomic status on the well-being of older adults. However, there is still a lack of comparative research on the impact of these two factors on the well-being of older adults. The potential relationship between the impact of adult children’s socioeconomic status on the well-being of older adults and the intergenerational support provided by adult children remains unclear. The logical relationship between how adult children influence the well-being of their elderly parents is still unknown. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a systematic study by simultaneously including adult children’s intergenerational support and socioeconomic status in the model of the influence of the well-being of older adults.

Our study focuses on how adult children influence the well-being of their elderly parents in China. The necessity and practical significance of this study are reflected in two aspects. On the one hand, China still retains its uniqueness in cultural background, family relationships, and elderly care models. Chinese culture is rooted in Confucianism, and the Chinese family is more like a "community" (Zimmer et al., 2002), where family members concentrate various aspects such as economy, culture, ability, information, etc. in the center of the family and provide support for all family members. In China, older adults have a higher degree of dependence on family members, particularly their children. On the other hand, China’s welfare system and older adults’ care system are still not sufficiently developed (Yuan et al., 2022). The pension insurance system in China faces challenges such as low coverage (Oksanen, 2010), imbalanced development of social security systems between urban and rural areas, and inefficient management of pension funds (Zhang, 2011; Guo et al., 2012). In terms of the healthcare system, there are issues with inadequate government healthcare investment, insufficient medical insurance funds, rising medical costs, low levels of basic medical care for older adults, and slow development of rural healthcare (Xiao and Chen, 2008). The main problems of the elderly care service system are the inadequate development of the elderly care service system, the insufficient number of caregivers, low service quality, and poor living environment in elderly care facilities. Home-based elderly care is the primary mode of elderly care in China, and both economically and spiritually, older adults in China are more dependent on their children.

Moreover, special attention should be paid to the fact that China’s unique dual urban-rural structure leads to significant differences in the situation of older adults’ families between urban and rural areas (Jie, 2017; Zhang, 2012). Firstly, in China, urban areas have significantly better economic development, social pension services, and coverage than rural areas (Zhang, 2012), which theoretically leads to less dependence of urban older adults on their adult children than rural ones (Lei, 2013; Shang, Wu (2011)). However, at the same time, a large number of middle-aged labor forces in rural areas have migrated to cities (Shang, Wu (2011); Liang and Wu, 2014), leaving many rural older adults in an empty-nest living situation. This change has altered the previously close intergenerational relationships between rural older adults and their children and may also have an impact on the well-being of rural older adults (Silverstein et al., 2006). Secondly, China’s family planning policy is more strictly implemented in urban areas, while in many rural areas, the "one and a half child" policy has long been implemented, allowing families to have a second child if the first is a girl. Differences in fertility have determined the differences in family structure and intergenerational relationships, and also result in different paths of how the number of children in a family affects the well-being of older adults. Ignoring differences in the number of children can easily lead to incomplete conclusions and biased information (Buber and Engelhardt, 2008; Angeles, 2010; Shiyong and Jia, 2016).

In summary, a comprehensive understanding of how adult children influence the well-being of older adults in China requires a systematic analysis of multiple dimensions. Our study established a multi-level and multi-dimensional comparison that examines various factors, including the number of adult children, urban and rural areas, and the influence of both the socioeconomic status and intergenerational support of adult children. Through our research, we aim to enrich the theoretical knowledge regarding the impact of adult children on the psychological well-being of elderly individuals and supplement existing research with data from China. Furthermore, our study findings will provide guidance for the development of relevant public policies for elderly individuals in China.

Research hypotheses and models

As previously mentioned, scholars have confirmed that the educational level and income level of children significantly impact the well-being of older adults (Friedman and Mare, 2014; Yahirun et al., 2017; Lee, 2017). While the educational level and financial conditions of adult children are closely intertwined, there have been few comprehensive analyses that incorporate both factors into a single model. Additionally, their pathways of influence on the well-being of older adults often differ. Therefore, we distinguish between these two factors for verification, and thus we offer the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The education level of adult children has a significant positive influence on the well-being of older adults.

Hypothesis 2: The financial conditions of adult children have a significant positive influence on the well-being of older adults.

Based on the analysis of the previous section, although previous research has not reached a consistent conclusion on the influence of intergenerational support from adult children on the well-being of older adults, in the case of Chinese older adults, there is a stronger dependence on their children. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Financial support from adult children has a significant positive influence on the well-being of older adults.

Hypothesis 4: Care support from adult children has a significant positive influence on the well-being of older adults.

Hypothesis 5: Spiritual support from adult children has a significant positive influence on the well-being of older adults.

The theoretical argument suggests that an enhancement in the adult children’s socioeconomic status would promote greater intergenerational support, particularly in terms of financial support. This implies that the socioeconomic status of adult children may have a positive effect on the well-being of older adults through increased intergenerational support. Based on this analysis, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 6: The impact of adult children’s education level on the well-being of older adults is mediated by intergenerational support provided by their adult children.

Hypothesis 7: The impact of adult children’s financial conditions on the well-being of older adults is mediated by intergenerational support provided by their adult children.

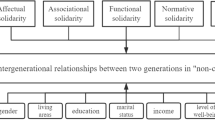

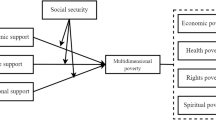

Based on hypotheses 1–7, we constructed a conceptual model depicting the relationships between adult children’s socioeconomic status, intergenerational support, and the well-being of older adults. Please refer to Fig. 1 for details.

Methods

Study population

The data used in this article is derived from the 2014 China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey (CLASS). CLASS is a comprehensive and ongoing social survey project undertaken by Renmin University of China, focusing on individuals aged 60 and above in China. The project’s objective is to gather information on the social and economic backgrounds of older adults in China, as well as the status of their adult children, to understand the various challenges faced by older adults during the aging process. It also aims to provide a data foundation for research and solutions to China’s aging problem. The CLASS 2014 survey serves as the baseline survey for the project and adopts a multi-stage, probability sampling method with multiple layers. The survey covers 29 provinces across China (including four autonomous regions and four municipalities directly under the central government), encompassing 134 counties and districts, 462 villages, and a total of 11,511 respondents. This study mainly involves the content of the CLASS survey on the education, income, health status, as well as the education and financial conditions of the living children of the older adult. A sample of 11,201 older adults who had given birth to children was initially selected. After excluding missing values in other variables, a total of 9146 samples were retained including 1479 older adults with one child, 2586 with two children, and 5081 with three or more children. There were three reasons for removing samples with missing values. Firstly, the missing data were mainly concentrated on the issue of financial support from adult children. The true reasons for older adults refusing to answer this question were complex and cannot be scientifically inferred using statistical methods. Therefore, any alternative method for missing values could potentially result in distorted findings. Secondly, considering that this survey was conducted on a large scale, even after eliminating samples with missing values, the remaining sample size still exceeded 9000, ensuring a sufficiently robust dataset. Thirdly, we compared the demographic characteristics, including gender, age structure, education level, and marital status, of the sample before and after the exclusion of missing values, and found no significant differences. Therefore, we considered the approach of deleting missing values to be appropriate and able to ensure the representativeness of the sample.

Measurement

The well-being of the older adults

In early research in psychology and sociology, the concept of well-being was broad and typically assessed using three indicators: life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect (Hansson et al., 2008). Subsequent studies have employed slightly different indicators to measure well-being. For example, Nguyen et al. (2016) measured well-being in older adults using three indicators: life satisfaction, happiness, and self-esteem. Fuller-Iglesias and Antonucci (2016) employed four dimensions, including life satisfaction, self-rated health, depression, and chronic illness, to measure well-being among older adults. Health holds particular significance for older adults compared to other aspects. Older adults’ self-assessment of their physical condition and health status reflects not only their current health but also their future health status, resistance to disease, and level of concern for their health (Read et al., 2016; Yip et al., 2007). Therefore, in this study, self-rated life satisfaction and self-rated health were used as measures of well-being in older adults. Subjective questions in the survey were strictly prohibited from being answered on behalf of others. The item of life satisfaction is "Overall, how satisfied are you with your current life?" The scoring ranges from 1 to 5, with five options: "Very dissatisfied," "Somewhat dissatisfied," "Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied," "Somewhat satisfied," and "Very satisfied." The question of self-rated health is: "How would you rate your current health?" with responses also on a 5-point scale ranging from "Very unhealthy" to "Very healthy." Higher scores indicate higher levels of life satisfaction and better health status.

Intergenerational support

The measurement of intergenerational support from adult children comprises three variables: financial support, care support, and spiritual support. The item assessing financial support is as follows: "In the past 12 months, has this child given you (or your spouse if living with you) money, food, or gifts worth a total of how much?" Respondents indicate the value on a scale ranging from 1 to 9, with "1 = none; 2 = 1–199 Chinese Yuan (CHY); 3 = 200–499 CHY; 4 = 500–999 CHY; 5 = 1000–1999 CHY; 6 = 2000–3999 CHY; 7 = 4000–6999 CHY; 8 = 7000–11999 CHY; 9 = 12000 CHY or more". The question of care support is: "How often in the past 12 months has this child helped you with household chores?" Responses are rated on a scale ranging from 1 to 5, with "1 = almost never; 2 = a few times a year; 3 = at least once a month; 4 = at least once a week; 5 = almost every day". The item of spiritual support is: "Do you feel this child is not concerned enough for you?" with values ranging from 1 to 4, representing "1 = frequently; 2 = sometimes; 3 = rarely; 4 = never.

Socioeconomic status of adult children

The socioeconomic status of adult children comprises two variables: their education level and financial conditions. Education level is scored on a scale of 1 to 5, ranging from illiterate (1), primary school (2), junior high school (3), high school or vocational school (4), to college or higher (5). The scoring for financial conditions ranges from 1 to 5, with 1 being "very difficult," 2 being " relatively difficult," 3 being "barely sufficient," 4 being " relatively affluent," and 5 being "very affluent."

Control variable

To control for potential confounding factors, common demographic variables was included as control variables in our study (Williams et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2021). These variables include older adults’ gender (0 = male; 1 = female), age, marital status (0 = married; 1 = not married), and education level (1 = illiterate; 2 = private school/literacy class; 3 = elementary school; 4 = junior high school; 5 = senior high school/technical secondary school; 6 = college or above). Moreover, when examining the well-being of older adults, employment status may also be one of the influencing factors (Zhou et al., 2021). Therefore, we also included older adults’ employment status (0 = not currently engaged in paid work, 1 = currently engaged in paid work) as a control variable in the model.

Statistical analysis

This study utilized descriptive statistical analysis and structural equation modeling (SEM) to analyze the data. Additionally, the bootstrap method was used to test the mediating effects. Moreover, SEM analysis has advantages in handling the issues of measurement variable aggregation and group comparison (Kuklys, 2005). Grace (2006) comprehensively analyzed SEM in comparison to other multivariate statistical methods, indicating that SEM can better address the limitations of discriminant analysis, principal component analysis, regression tree, factor analysis, and multiple regression methods, and provide improved explanations of relationships between variables. SEM analysis, which combines factor analysis and path analysis, offers several advantages in dealing with multivariate covariance matrices. First, it allows for the inclusion of measurement errors in independent variables. Second, it can simultaneously handle multiple dependent variables. Third, it can model both measurement relationships and structural relationships between factors in a single model.

To explore the detailed situation of the influence of adult children’s socioeconomic status and intergenerational support on the well-being of older adults with different numbers of children, our study initially categorized the sample of older adults into three distinct groups: individuals with one child, those with two children, and those with multiple (three and more) children. Then, we compared urban and rural older adult groups with different numbers of children using separate models. Therefore, the analysis unit of this study is six groups of older adults with different numbers of children in urban and rural areas. We categorized the number of children into 1, 2, and 3+ for group analysis, primarily based on two reasons. Firstly, it follows conventional ideas and related legal provisions in China. For example, the " Household Registration Regulations of the People’s Republic of China" stipulates that "three or more (including three) belong to multiple children". Therefore, we believe that the 3+ children model can be classified as a multiple children model. Secondly, to avoid excessively complicated model results, if we conduct more detailed groupings, there will be more than eight models to compare, and the model results will appear to be too complicated.

To measure the socioeconomic status and intergenerational support of elderly individuals with two children and those with three or more children, we utilized the advantages of SEM by merging the different birth orders of the same number of children into one measurement model. For example, in the measurement model for the educational level of older adults with two children, we combined the education level of the first-born child and the second-born child. It is worth noting that the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results for all latent variables related to socioeconomic status and intergenerational support for older adults with more than two children show that regardless of the number of children, all children have similar levels of socioeconomic status and intergenerational support.

We assessed the goodness of fit of all six models by examining their fit indices. The goodness-of-fit index (GFI), adjust goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and comparative fit index (CFI) values for all models exceeded 0.9, and the mean root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) was less than 0.08. Additionally, the X2/DF values were less than 5 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Therefore, all fit indices met the ideal criteria.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The well-being of Chinese older adults with different numbers of children in urban and rural areas as well as the status of their children are shown in Table 1. The results showed that Chinese older adults had a high level of life satisfaction, with a mean value of 4.09 for the overall sample. The life satisfaction of older adults with multiple children was slightly higher than that of other older adult groups. The mean value of self-rated health for older adults was 3.21. For urban older adults, the more children they have, the lower their self-rated health. The mean value of self-rated health for urban older adults with one child, two children, and multiple children were 3.54, 3.46, and 3.22, respectively. For rural older adults, those with multiple children had the lowest self-rated health mean value, which was 3.10. The self-rated health scores for rural older adults with one child and two children were 3.23 and 3.25, respectively. Overall, urban older adults reported higher levels of life satisfaction and self-rated health than their rural counterparts.

The education level of adult children in Chinese urban and rural area gradually decreased with an increase in the number of children. For groups with one child to multiple children, the mean educational levels of urban children groups were 4.52, 4.03, and 3.45, while the mean educational levels of rural children groups were 3.43, 3.21, and 2.70, respectively. The educational level of urban adult children was significantly higher than that of rural adult children. Similarly, in terms of the overall financial conditions of children, urban areas hold an advantage over rural areas, although the disparity between urban and rural areas is relatively smaller than that observed in educational levels. In rural areas, the financial conditions of adult children gradually improve with the increase in the number of children, with mean values of 2.89, 2.99, and 3.12 for one, two, and multiple children, respectively. In contrast, in urban areas, the economic conditions of multiple children groups are slightly lower than those of groups with one or two children. In contrast, the opposite is true for urban areas, as the financial conditions of adult children in households with multiple children are slightly lower than those with one child or two children.

The financial support provided by adult children in urban and rural China gradually decreased with the increase in the number of children. The mean values of financial support provided by urban adult children, from one child to multiple children, were 4.81, 4.42, and 3.88 respectively. The mean values of rural adult children’s financial support, from one child to multiple children, were 4.53, 4.02, and 3.48 respectively. Overall, urban adult children provided slightly higher financial support compared to rural adult children. There is no significant difference in care support from adult children between urban and rural areas, both of which show a trend of gradually decreasing with an increase in the number of children. For groups with one child to multiple children, the mean of urban groups’ care support were 2.79, 2.51, and 2.44, respectively, while the mean of rural groups’ care support were 3.00, 2.42, and 2.31, respectively. The mean of spiritual support was relatively high and significantly higher than that of care support. However, there was a significant urban-rural difference among only-children groups. Specifically, the level of spiritual support provided by urban one-child group was the lowest among all urban groups, with a mean of 3.66, while in rural groups, the one-child group was the highest, with a mean of 3.85.

The mean age of the older adult sample was 69.76 years, and there was no significant difference in age between urban and rural samples. The average age of older adults increased with the number of adult children. The sample’s gender was close to the median of 0.5 in the total sample, urban-rural samples, and the samples in different number of children groups, indicating a roughly equal representation of males and females in the sample. Marital status of the sample was mostly in the married state. The educational level among older adults was generally low. In urban groups, the educational level gradually decreased with an increasing number of children, while in rural groups, the education level of older adults with multiple children was lower than that of those with one child or two children. About 20% of older adults were employed and receiving income, with a significantly higher proportion of rural older adults than urban older adults.

Comparison of model paths between urban and rural areas with different number of children

We conducted CFA on all measurement models. The composite reliability (CR) of all measurement models exceeded the standard of 0.6, and the average variance extracted (AVE) of all models exceeded the standard of 0.4 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). The factor loadings of observed variables ranged from 0.5 to 0.95, and the squared multiple correlations (SMC) ranged from 0.25 to 0.9 (Lam, 2012). The results indicate that all measurement models demonstrated good reliability and validity based on these standards. See Table 2 for details.

We used the group comparison method of SEM to compare the significant differences among the models of older adults with different numbers of adult children in urban and rural areas. The group comparison results indicate that there are significant differences (P < 0.05) in the path coefficients of the models for different groups. The fitting results of the models of older adults with different numbers of adult children in urban and rural areas are shown in Table 3, and the standardized paths are shown in Fig. 2.

The model results for the groups of older adults with one child are shown as follows: for the urban group, only the financial condition and spiritual support from adult children had a significant influence on their well-being, with total effect values of 0.360 and 0.126, respectively, while the intergenerational support and educational level of adult children did not have a significant influence. Additionally, there were no significant indirect effects of adult children’s education level and financial condition on well-being in this group, indicating the absence of mediating effects in these pathways. Therefore, for the group of urban older adults with only one child, hypotheses 2 and 5 were accepted, while hypotheses 1, 3, 4, 6, and 7 were rejected. For the rural group, the variables that have a significant impact on the well-being of older adults were children’s financial condition, care support, and spiritual support, with total effect values of 0.496, 0.192, and 0.215, respectively. The indirect effects of adult children’s education level on the well-being of older adults were not significant, indicating that there is no mediating effect in this path. The indirect effect of adult children’s financial condition on the well-being of older adults was significant, indicating that there was a mediating effect, with a mediation effect value of 0.084. Therefore, the group of rural older adults with only one child accepted hypotheses 2, 4, 5, and 7, and rejected hypotheses 1, 3, and 6.

The results of the model for the groups of older adults with two children are shown as follows: for the urban group, the variables that have a significant impact on the well-being of older adults were children’s financial condition, care support, and spiritual support, with total effect values of 0.452, 0.106, and 0.096, respectively. The indirect effects of children’s education level and financial condition on the well-being of urban older adults through this path are not significant, indicating that there is no mediating effect. Therefore, the group of urban older adults with two children accepted hypotheses 2, 4, and 5, and rejected hypotheses 1, 3, 6, and 7. In the rural group, the variables that have a significant impact on the well-being of older adults were children’s education level, financial condition, and financial support, with total effect values of 0.134, 0.468, and −0.174, respectively. The indirect effects of adult children’s education level and financial condition on the well-being of rural older adults through this path are not significant, indicating that there is no mediating effect. Therefore, for the group of rural older adults with two children, hypotheses 1 and 2 were accepted, while hypotheses 3–7 were rejected.

The model results for groups of older adults with multiple children are as follows: for the urban group, the variables that have a significant impact on their well-being included children’s education level, financial condition, care support, and spiritual support, with the effect values of 0.098, 0.412, 0.062, and 0.160 respectively. In addition, there were significant indirect effects of adult children’s education level and financial condition on the well-being of urban older adults, indicating the presence of mediating effects in these pathways. Therefore, for the group of urban older adults with multiple children, hypotheses 1–2 and 4–7 were accepted, while hypothesis 3 was rejected. For the rural group, the variables that significantly influenced the well-being of older adults were consistent with the urban group, including adult children’s education level, financial condition, care support, and spiritual support, with total effect values of 0.110, 0.443, 0.087, and 0.158, respectively. The indirect effect of children’s education level on the well-being of rural older adults was not significant, indicating that there was no mediating effect in the path. Moreover, there was a significant indirect effect of adult children’s financial condition on the well-being of older adults, indicating the presence of mediating effects in this path. Therefore, the group of rural older adults with multiple children accepted hypotheses 1,2, 4–5, and 7, and rejected hypotheses 3, and 6.

The results of hypothesis testing are presented in Table 4.

Discussion

Our study explored the mechanisms through which adult children influence the well-being of older adults in China, and compared group differences among urban and rural older adults with different numbers of children. Some of our findings are consistent with previous research, such as the better well-being of urban older adults compared to rural older adults in China (Wen et al., 2014; Tao et al., 2015). Furthermore, our study revealed that a higher number of children is associated with higher life satisfaction among older parents, which also supported the viewpoint of some scholars that Chinese older adults are ‘more children, more happiness’ (Zheng and Chen, 2020). Additionally, our study found that, regardless of whether the older adults lived in urban or rural areas, a higher number of children was associated with less financial and care support from children. This finding supports the conclusions of a few scholars in previous literature (Abolfathi et al., 2014).

In addition to the aforementioned findings, our study also revealed some interesting conclusions. Firstly, we found significant differences in the effects of children’s education level and financial condition on the well-being of their elderly parents. The influence of children’s financial condition on the well-being of Chinese older adults was significant and widespread showing strong consistency both among groups of urban and rural areas with across different numbers of children. This effect was particularly pronounced among rural older adult groups, with all effect sizes exceeding 0.4. In contrast, the education level of adult children does not impact all groups of older adults’ well-being, and the extent of its influence is relatively weak. This finding differs greatly from some previous studies conducted in Western countries (Friedman and Mare, 2014; Yahirun et al., 2016; Yahirun et al., 2017), which emphasized the importance of children’s education level in shaping the well-being of older adults. The underlying reasons for our study’s conclusion may be related to the current economic development status and the economic situation of its residents in China. Compared to other countries, disposable income of Chinese residents is still relatively low. Therefore, Chinese older adults may prioritize their children’s financial status over their educational level. Improved living conditions of their children could provide them with greater peace of mind, potentially leading to an increase in their overall well-being.

Secondly, we found a stark contrast between the impact of adult children’s financial conditions and intergenerational support on the well-being of older adults. In terms of effect sizes, the influence of adult children’s financial conditions on the well-being of older adults far exceeded that of intergenerational support. In terms of the scope of influence, children’s financial condition had a significant impact on the well-being of all older adults, whereas the three aspects of intergenerational support from children do not have effects on all of groups older adults’ well-being in China, especially financial support from children does not have a positive impact on the well-being of any group of older adults. These findings differ from our initial expectations but are similar to the findings of previous studies by some scholars (Abolfathi et al., 2014). Compared to children’s financial support and care support, children’s spiritual support was found to be the most influential aspect of the three items of intergenerational support for the well-being of older adults. This suggests that Chinese older adults place a higher value on emotional comfort from their children rather than monetary support, and may not necessarily desire or expect their children to provide them with more financial assistance. The underlying reason could be that Chinese older adults often wish their children to live well, particularly in economic terms, and do not want to become a financial burden to their children.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that our study found that the impact of children’s financial conditions on the well-being of older adults is primarily through direct effects. The mediating effect was only significant in the group of rural older adults with one child and the groups of older adults with multiple children, and the effect was minimal. In both groups of older adults with two children and the group of urban older adults with one child, this influence was not mediated by intergenerational support. This conclusion suggests that the existing literature on the intrinsic factors explaining the impact of adult children’s socioeconomic status on older adults’ well-being may not be applicable in China. That is, for Chinese older adults, it is not necessarily that the higher socioeconomic status of adult children leads to higher levels of support from them, which in turn enhances the well-being of older adults (Bernheim et al., 1985; Shi, 2015). Instead, the improvement in adult children’s socioeconomic status itself may directly and significantly enhance the well-being of older adults, possibly due to the sense of security and superiority that the higher socioeconomic status of adult children can provide to their parents (Lee, 2017).

By conducting a comprehensive multidimensional comparison, the main finding of our study is that for Chinese older adults, “whether my children are living well” is more important than “what my children can provide for me”. China’s welfare system is not yet fully developed, and the elderly care system has yet to cover all urban and rural areas of the country (Yuan et al., 2022). In late life, Chinese older adults objectively still heavily rely on support from their adult children for their well-being. However, the psychological needs of Chinese older adults reflect more concern for their children rather than demands from them. While China’s economy is experiencing rapid development, the younger generation is also facing significant pressures in terms of education, employment, and competition, particularly in the context of high housing prices, which exacerbate the challenges of living costs and financial burdens. We recommend China pay special attention to alleviating economic pressure on young urban and rural residents, improving the education environment, and raising their living standards while achieving rapid overall economic growth. This approach can not only promote the healthy development of China’s society and economy but also contribute to the improvement of the well-being and quality of life of older adults in China, which is of utmost significance for addressing the current challenges of the aging population in China.

Furthermore, there are some limitations to this study. Firstly, the data used in this study are from the 2014 CLASS. Since 2014, there have been changes in Chinese society, including shifts in population demographics among different age groups of older adults. Therefore, future research should consider updated data to further investigate this topic. Secondly, this study is based on CLASS data, where the scoring of children’s financial conditions is based on subjective evaluations by older adults. While objective data on children’s income can be challenging to obtain, future research could benefit from combining subjective and objective data on children’s financial conditions to further investigate the relationship between children’s socioeconomic status and older adults’ health, as well as health inequality issues.

Conclusion

Our study found that intergenerational support from adult children does not universally impact the well-being of all older adults in China, whereas the influence of children’s financial conditions, which is an indicator of socioeconomic status, on the well-being of older parents is strong and widespread. Meanwhile, our research results indicate that the impact of adult children’s socioeconomic status on the well-being of older adults is primarily through direct effects, with little intervention or influence from intergenerational support. In comparison to children’s financial conditions, the influence of children’s education level on the well-being of older adults is not consistent and relatively weaker. In conclusion, for the well-being of older adults in China, the financial status of their adult children plays a more pivotal role than the intergenerational support received from their children. This conclusion extends existing intergenerational relationship theories, revealing the connection between the financial conditions of adult children and the well-being of older parents, as well as the relatively secondary role of intergenerational support by adult children on the well-being of their parents. From a certain perspective, ensuring a good life for adult children can be considered the greatest filial piety towards parents. In terms of policy, the government could consider adjusting social welfare policies based on this conclusion to prioritize improving the financial conditions of adult children, which can indirectly enhance the well-being of older adults. At the family level, the implications of these findings can provide guidance for both older adults and adult children. Parents can place greater importance on their children’s career development, and children should strive to improve their own financial conditions, indirectly benefiting the well-being of their older parents. In summary, the conclusions of this study have significant implications for theory, policy, and practice. They contribute to a deeper understanding of intergenerational relationships in the Chinese context, as well as the influence of adult children on the well-being of older parents. Furthermore, these findings provide valuable insights for informing relevant policy development.

Data availability

We are unable to provide the dataset directly as it requires a separate application for usage rights. The data that support the findings of this study are available on the website of the China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey (CLASS) at http://class.ruc.edu.cn/. To access and use this survey data for research purposes, please contact the China Survey Data Center of Renmin University of China (email: class@nsrcruc.org). The dataset generated and/or analyzed during the current research period can be provided by the corresponding author at the author’s reasonable request.

References

Abolfathi MY, Ibrahim R, Hamid TA (2014) The impact of giving support to others on older adults’ perceived health status. Psychogeriatrics 14(1):31–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12036

Angeles L (2010) Children and life satisfaction. J Happiness Stud 11(4):523–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-009-9168-z

Bernheim BD, Shleifer A, Summers LH (1985) The strategic bequest motive. J Polit Econ 93(6):1045–1076. https://doi.org/10.1086/261351

Brooke HL, Ringbäck WG, Talbäck M, Feychting M, Ljung R (2017) Adult children’s socioeconomic resources and mothers’ survival after a breast cancer diagnosis: a Swedish population-based cohort study. Bmj Open 7(3):e014968, https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/7/3/e014968

Buber I, Engelhardt H (2008) Children’s impact on the mental health of their older mothers and fathers: findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. Eur J Ageing 5(1):31–45. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10433-008-0074-8

Cheng ST, Chan A (2006) Filial piety and psychological well-being in well older Chinese. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 61(5):262–269. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.5.P262

Chen X, Silverstein M (2000) Intergenerational social support and the psychological well-being of older parents in China. Res Aging 22(1):43–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027500221003

Cong Z, Silverstein M (2012) Caring for grandchildren and intergenerational support in rural China: a gendered extended family perspective. Ageing Soc 32(3):425–450. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X11000420

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Market Res 18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

Friedman EM, Mare RD (2014) The schooling of offspring and the survival of parents. Demography 51(4):1271–1293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0303-z

Fuller-Iglesias HR, Antonucci TC (2016) Familism, social network characteristics, and well-being among older adults in Mexico. J Cross-Cultural Gerontol 31(1):1–17. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10823-015-9278-5

Grace JB (2006) Structural equation modeling and natural systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK

Guo J, Lian R, Shi Z(2012) Discussion on the reform and perfection of China’s old age insurance system. J Social Sci Shanxi Colleges Univ 8:29–33

Hansson A, Forsell Y, Hochwälder J, Hilleras P J (2008) Impact of changes in life circumstances on subjective well-being in an adult population over a 3-year period. Public Health 122(12):1392–1398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2008.05.020

James MR, Jersey L, Erika K, Yoko S, Taro F (2009) Work, health, and family at older ages in Japan. Res Aging 31(2):180–206. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0164027508328309

Jie E (2017) Pensions and multidimensional elderly poverty and inequality: a comparative perspective on urban and rural non-compulsory pension insurance. Chin J Popul Sci 05:62–73+127

Kuklys W (2005) Amartya sen’s capability approach: theoretical insights and empirical applications. Studies in Choice & Welfare. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-28083-9

Lam LW (2012) Impact of competitiveness on salespeople’s commitment and performance. J Business Res 65(9):1328–1334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.026

Lee C (2017) Adult children’s education and physiological dysregulation among older parents. J Gerontol: Series B 73(6):1143–1154. https://academic.oup.com/psychsocgerontology/article/73/6/1143/3746257

Lei L (2013) Sons, daughters, and intergenerational support in China. Chin Sociol Rev 45(3):26–52. https://doi.org/10.2753/CSA2162-0555450302

Liang Y, Wu W (2014) Exploratory analysis of health-related quality of life among the empty-nest elderly in rural China: an empirical study in three economically developed cities in eastern China. Health Quality Life Outcomes 12(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-12-59

Lin J, Chang T, Huang C (2011) Intergenerational relations and life satisfaction among older women in Taiwan. Int J Soc Welf 20:S47–S58. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2011.00813.x

Nguyen AW, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Mouzon DM (2016) Social support from family and friends and subjective well-being of older African Americans. J Happiness Studies 17:959–979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9626-8

Oksanen H (2010) The chinese pension system-first results on assessing the reform options (No. 412). Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), European Commission

Paul RA, Tamara DA (2006) Feeling caught between parents: adult children’s relations with parents and subjective well-being. J Marriage Fam 68(1):222–235. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00243.x

Peng H, Mao X, Lai D (2015) East or west, home is the best: effect of intergenerational and social support on the subjective well-being of older adults: a comparison between migrants and local residents in Shenzhen, China. Ageing Int 40(4):376–392. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12126-015-9234-2

Read S, Grundy E, Foverskov E (2016) Socio-economic position and subjective health and well-being among older people in Europe: a systematic narrative review. Aging Mental Health 20(5):529–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1023766

Shang X, Wu X (2011) The care regime in China: Elder and child care. J Comp Soc Welf 27(2):123–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/17486831.2011.567017

Shiyong HU, Jia LI (2016) The influence of the number of children on the intergenerational economic support of the rural elderly: parent-child separation family as the research object. Population & Economics

Shi Z (2015) Does the number of children matter to the happiness of their parents? Soc Res 5:27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40711-016-0031-4

Silverstein M, Cong Z, Li S (2006) Intergenerational transfers and living arrangements of older people in rural China: consequences for psychological well-being. J Gerontol Series B, Psychol Sci Soc Sci 61(5):256–266. https://academic.oup.com/psychsocgerontology/article/61/5/S256/604070

Sun R (2004) Worry about medical care, family support, and depression of the elders in urban China. Res Aging 26(5):559–585. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0164027504266467

Tao T, Chen Y, Zhu J, Liu P (2015) Effect of air pollution and rural-urban difference on mental health of the elderly in China. Iran J Public Health 44(8):1084–1094. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.d01-231.x

Torssander J (2013) From child to parent? The significance of children’s education for their parents’ l ongevity. Demography 50(2):637–659. https://read.dukeupress.edu/demography/article/50/2/637/169677/From-Child-to-Parent-The-Significance-of-Children

Torssander J (2014) Adult children’s socioeconomic positions and their parents’ mortality: a comparison of education, occupational class, and income. Soc Sci Med 122:148–156. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277953614006960?via%3Dihub

Wen Y, Zong Z, Shu X, Zhou J, Sun X, Ru X (2014) Health status, health needs and provision of health services among the middle - aged and elderly people. Popul Res 38(5):15

Williams L, Zhang R, Packard KC (2017) Factors affecting the physical and mental health of older adults in China: the importance of marital status, child proximity, and gender. SSM-Popul Health 3:20–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.11.005

Xiao Y, Chen L (2008) Problems and countermeasures of the medical insurance system for the aged in rural areas in China. Chin J Gerontol 18:1871–1872

Xu Q (2017) More than upbringing: parents’ support and effect on filial duty. Society 37(2):25. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-8004.2017.02.009

Yahirun JJ, Sheehan CM, Hayward MD (2016) Adult children’s education and parents’ functional limitations in Mexico. Res Aging 38(3):322–345. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0164027515620240

Yahirun JJ, Sheehan CM, Hayward MD (2017) Adult children’s education and changes to parents’ physical health in Mexico. Soc Sci Med 81:93–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.034

Yuan B, Li J, Liang W (2022) The interaction of delayed retirement initiative and the multilevel social health insurance system on physical health of older people in China. Int J Health Plan Manag 37(1):452–464. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3352

Yip W, Subramanian SV, Mitchell AD, Lee DT, Wang J, Kawachi I (2007) Does social capital enhance health and well-being? Evidence from rural China. Soc Sci Med 64(1):35–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.027

Zhang Y (2011) A study of government responsibility for the social security of the aged people in the context of population aging in China. Henan University, Kaifeng

Zhang Y (2012) The Analysis on Economic Development and Urban-Rural Income Gap of China. IEEE IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/MINES.2012.217

Zheng Z, Chen H (2020) Age sequences of the elderly’ social network and its efficacies on well-being: an urban-rural comparison in China. BMC Geriatrics 20(1):372. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01773-8

Zhou R, Chen H, Zhu L, Chen Y, Chen B, Li Y, Chen Z, Zhu H, Wang H (2021) Mental health status of the elderly Chinese population during COVID-19: an online cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry 12:645938. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.645938

Zimmer Z, Hermalin AI, Lin H (2002) Whose education counts? The added impact of adult-child education on physical functioning of older Taiwanese. J Gerontol Series B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 57(1):23–32. https://academic.oup.com/psychsocgerontology/article/57/1/S23/576211

Zimmer Z, Martin LG, Chuang Y, Ofstedal MB (2007) Education of adult children and mortality of their elderly parents in Taiwan. Demography 44(2):289–305. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2007.0020

Acknowledgements

The data that support the findings of this study are available on the website of the China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey (CLASS) at http://class.ruc.edu.cn/. To access and use this survey data for research purposes, please contact the China Survey Data Center of Renmin University of China (email: class@nsrcruc.org).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (21BRK020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: ZZ and HC; Data curation: ZZ; Formal analysis, ZZ and NS; Methodology: ZZ, HC and LY; Validation: ZZ and HC; Investigation: ZZ, HC and WL; Software: ZZ, NS and LY; Resources: ZZ; Writing—original draft preparation: ZZ; Writing—review and editing: HC, NS, LY, YL and YC; Visualization: ZZ, NS, WL and LY; Supervision: HC; Project administration: HC; Funding acquisition: ZZ.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The data used in this manuscript were from a large national social survey (CLASS), and the survey was approved by the ethic committee of the School of Statistics of Renmin University of China, but the ethics number has not been publicly released. All participants provided written informed consent. All methods employed in the study were performed in accordance with the relevant international guidelines and regulations.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. No identifying information was collected during the survey, and there are no ethical issues with science and technology.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Z., Sun, N., Yang, L. et al. The socioeconomic status of adult children, intergenerational support, and the well-being of Chinese older adults. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 481 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01970-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01970-x

This article is cited by

-

The impact of digital literacy in enhancing individuals’ health in China

BMC Public Health (2025)