Abstract

This study offers a novel perspective on interpreter visibility by exploring speaker references to interpreters, which differs from previous research that primarily focused on interpreter visibility through their own discourse contributions. Employing a multimodal conversation analysis approach, the study examined the verbal and nonverbal resources utilized by speakers and interpreters in 98 selected excerpts taken from press conference interpreting sessions at the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT). The analysis revealed six distinct topics that denoted the ways in which interpreters were rendered noticeable to the audience through the speaker’s references. These references were context dependent, leading to subsequent speaker–interpreter interactions where interpreters became highly visible. In addition to verbal cues, nonverbal semiotics played a crucial role in demonstrating how interpreters working in rigidly structured press conferences could function as active co-participants of discourse, and how the speaker and interpreter could collaborate to facilitate the interpreter’s visibility and promote a relaxed communicative environment. These findings shed new light on the interpreter’s role, underscoring that it is a dynamic phenomenon requiring analysis in relation to the specific communicative context. This study demonstrated the efficacy of utilizing multimodal conversation analysis as a methodology to explore interactions between speakers and interpreters and to gain a deeper understanding of the complex and nuanced aspects of conference interpreting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The topic of interpreter’s visibility has been a persistent area of study in interpreting research, attracting significant academic attention and generating a wealth of empirical data. The concept, first put forward by Angelelli (2004), has revealed a tension between the professional standards for interpreter conduct described in metadiscourse and the actual practices of interpreters in real-world settings. The ideal role of an interpreter is often considered to be “invisible,” meaning they should remain unnoticed and blend their speaking position with that of the source speaker (as described in AIIC 1999, Section 3.3). However, “visibility” suggests that the interpreter could step out of obscurity and become noticeable to the audience through their own contributions or the contributions of other speakers.

Over the past decade, numerous studies utilizing real-world data have confirmed the interpreter’s visibility during instances when they were perceived and acknowledged by the communicative participants as effective co-constructors of communication. The majority of these studies centered on the visibility that interpreters themselves initiate, highlighting their active contributions to the discourse in medical (Cirillo, 2012; Zhang and Xu, 2021), legal (Arumí and Vargas-Urpi, 2018, 2019; Pease et al., 2018), educational (Arumí and Vargas-Urpi, 2017; Davitti, 2013), and press conference (Li et al., 2022) settings. On the other hand, only a few studies (Bartłomiejczyk, 2017; Diriker, 2004; Duflou, 2012, 2016) have delved into the instances where speakers initiate references to interpreters and/or their output, thereby rendering the interpreters visible. In addition, most of these studies focused on simultaneous interpreting in the context of the European Parliament, with little attention given to consecutive interpreting adopted by high-profile political institutions in the Chinese context.

Hence, the aim of this study is to re-examine the interpreter’s visibility from an under-researched viewpoint of the speaker’s references to interpreters and their output, based on consecutive interpreting in press conferences hosted by the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT), a Chinese interpreting context that has received limited attention (Li et al., 2022). To achieve this research objective, a multimodal conversation analysis methodology was adopted to analyze the data, encompassing both the verbal and non-verbal dimensions of interpreting. This study will focus on addressing the following questions:

-

(1)

To what extent and in what circumstances do the interpreters at AIT become visible?

-

(2)

How can speaker–interpreter interactions contribute to the interpreter’s visibility and communicative environment?

Research on the visibility of interpreters

Before the introduction of Angelelli’s (2004) concept of interpreter visibility, prior research had already implied and demonstrated its existence. Anderson (1976/2002) was the first to raise doubts about prescribed roles for interpreters and suggested that interpreters may not be invisible. In response to the growing communication problems faced by public-sector institutions in the 1980s and 1990s, a series of pioneering studies examined the actual performance of community interpreters. Wadensjö’s (1998) analysis of interpreter-mediated immigration and medical interviews made a significant contribution to interpreting research by establishing a new paradigm that focuses on descriptive analysis of discourse in interaction (DI). Previous studies within the DI paradigm utilized authentic discourse data and applied various analytical tools to explore different aspects of speaker–interpreter interaction, such as turn-taking (Roy, 2000), meaning negotiation (Davidson, 2000), and footing (Metzger, 1999) in diverse institutional contexts. This area of study is significant as it deconstructs the invisible role of interpreters and substantiates their dynamic participation in the communication process.

Angelelli (2004) provided the first proper definition and exemplification of the term “visibility.” According to her, interpreters become visible when they establish their own speaking position separate from that of the source speaker. Visibility is typically observed when interpreters manage turn-taking, control the flow of information, explain terms or concepts, filter information, and align with or potentially replace one of the communicative parties (Angelelli, 2004, p. 11). This concept has subsequently sparked debates among scholars in the field of interpreting. Ozolins (2016) expressed concerns regarding the examples used by Angelelli (2004) to illustrate interpreter visibility. He argued that some behaviors exhibited by interpreters, such as professional politeness, were necessary for the continuation of interpretation. However, other behaviors, such as filtering information or aligning with the original speaker, could be seen as departing from impartiality. In contrast, Downie (2017) advocated for a more focused analysis on “what interpreters do instead of whether their conduct complies with any perceived professional norms” (p. 268).

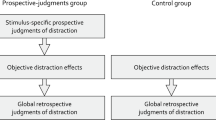

The topic of interpreter visibility continues to be a subject of ongoing scholarly interest and research. Researchers persist in investigating the presence of interpreters in various interpreted contexts and settings in order to gather more data that showcases their active role performance. These studies aim to enhance our understanding by providing additional evidence of how interpreters actively contribute to the communication process. Approaching the topic from two distinct perspectives, these studies examine who initiates the interpreter’s visibility. The primary perspective focuses on the interpreter’s own initiative in attaining visibility through their active contributions to the communicative discourse. The second perspective expands to include the speaker’s references to interpreters and/or their output, as well as the interpreter’s potential responses. However, it is often overlooked that interpreters gain visibility when they are referenced by the speaker. In fact, the moment the speaker mentions the interpreter, they can no longer remain in the shadows but become visible to the on-site audience. In the subsequent sections, we will review recent studies that have examined interpreter visibility from these two aforementioned perspectives.

Interpreter’s visibility initiated by interpreter-generated contributions

The visibility of interpreters is typically triggered by their independent contributions, indicating that interpreters are the ones who initially establish a separate speaker position from the source speaker at some point during the interpreting process. The contributions generated by interpreters that signify their visibility have been examined using various conceptual labels that essentially convey the same meaning. Most studies (Arumí and Vargas-Urpi, 2018; Baraldi, 2012; Cheung, 2017, 2018; Cirillo, 2012; Li et al., 2022) categorize such output as “non-renditions,” a term first introduced by Wadensjö (1998) to describe utterances by interpreters that lack a corresponding counterpart in the preceding source language and are “visibly designed to do coordinating work” (p. 109). In dialog-based community settings, non-renditions used for coordination, such as requesting clarification or turn-taking, are widely accepted as the norm. The focus of research, therefore, tends to be on relatively contentious non-renditions, such as those produced to give advice to institutional participants, answer on their behalf, or filter information not provided in the source utterances. According to researchers, the main issue with these non-renditions is that they can obstruct direct communication between institutional participants, such as between a doctor and patient (Baraldi, 2012; Cirillo, 2012) or a defendant and judge (Arumí and Vargas-Urpi, 2018, 2019; Cheung, 2012, 2014).

The concept of “text ownership” is another widely used term to describe the contributions generated by interpreters. This idea was first introduced by Angelelli (2004), who described how medical interpreters can assume various roles, such as a patient’s spokesperson or co-diagnostician, that extend beyond mere translation. According to Angelelli (2004), text ownership encompasses both “partial text ownership,” which refers to a blend of original messages and messages generated by the interpreter, and “total text ownership,” which refers to messages generated solely by the interpreter (p. 78). The level of visibility exhibited by an interpreter can vary depending on their level of involvement in establishing text ownership, creating a continuum of visibility ranging from low to high (Ibid). Recent studies have focused on visibility through text ownership in the context of medical interpreting (e.g., Zhang and Xu, 2021). While these studies acknowledge the significance of interpreters’ visibility in facilitating medical consultations, they also caution against excessive visibility, as it may disrupt direct communication between the doctor and patient.

Interpreting researchers have also delved into the concept of intercultural mediation, shedding light on interpreters’ visible role as co-constructors of discourse. Drawing on Wadensjö’s (1998) argument that “interpreters cannot avoid functioning as intercultural mediators through their translation activity” (p. 75), studies conducted in educational settings (Arumí and Vargas-Urpi, 2017; Davitti, 2013) have established a connection between interpreting and intercultural mediation. These studies have specifically focused on how interpreters handle “rich points” that indicate translation difficulties (Arumí and Vargas-Urpi, 2017) or “evaluative assessments” provided by teachers to immigrant parents concerning their children (Davitti, 2013). They have discovered that interpreters may become visible, acting as intercultural mediators, in order to address potential misunderstandings and foster agreement between interlocutors from different cultures. However, the researchers also caution that interpreter visibility can sometimes hinder immigrant parents from expressing their different perspectives (Davitti, 2013).

Interpreter’s visibility initiated by speaker’s references to interpreters

The visibility of interpreters initiated by the speaker’s references to them and/or their interpretation is under-researched compared to the abundant evidence of interpreters’ visibility initiated by their own contributions. This focus is primarily limited to conference interpreting (Bartłomiejczyk, 2017; Diriker, 2004; Duflou, 2012, 2016). This may be attributed to several reasons. Firstly, scholars may have begun with the examination of the interpreter’s independent actions in order to deconstruct the ideal of interpreters being “invisible.” Secondly, the speakers at international conferences, who are usually bilingual or multilingual elites such as politicians, diplomats, and academics, have a higher social standing and linguistic competence, which allows them to comment on interpreters and their interpretation. Finally, conference settings with rigid structures provide limited opportunities for interpreters to voice their opinions, and any exceptions are typically prompted by the speaker or other communicative participants.

In conference settings that utilize simultaneous interpreting, speakers may make references to interpreters along a positive-negative spectrum, ranging from commendation to critique, thus bringing interpreters out of obscurity and into the spotlight. Diriker (2004) was the first to empirically examine the visibility of interpreters through references made by source speakers in conference settings. Despite conference interpreting being considered as the “most prominent manifestation of interpreting” (Pöchhacker, 2016, p. 16), this does not imply that interpreters function as passive and invisible conduits, relegated to an “ivory tower.” Rather, as Diriker (2004) found, interpreters can assert themselves as autonomous actors when speakers unjustly accuse them of mistranslations.

Following Diriker’s (2004) groundbreaking research, several studies utilizing ethnographic methodology were conducted to explore the work of conference interpreters at the European Parliament (Duflou, 2012, 2016). Despite the highly formalized nature of conference interpreting, the speakers at these events would sometimes reference the interpreters, either in a positive or negative manner. This could result in the interpreters being acknowledged, appreciated, criticized, or even blamed. The interpreters would often respond by shifting into a third-person reference, as seen in Duflou’s (2012, p. 156) observation of “The chairman kindly thanks the interpreters.” Besides, if faced with unjustified criticisms from the speaker, the interpreters might defend themselves or distance themselves from the speaker by providing non-renditions, such as “The speaker’s microphone isn’t on, unfortunately the interpreters don’t hear anything” or “says the speaker…” (p. 157). These actions make the interpreters’ presence and role more prominent, moving them from the background to the forefront of the discourse.

The research by Bartłomiejczyk (2017) on the visibility of interpreters during plenary sessions of the European Parliament (EP) is a noteworthy contribution to the field. This ethnographic study provides a comprehensive analysis of 230 identified references to EP interpreters made by the speakers. Despite not addressing the interpreters’ handling of references to them in the source text, the study presents a detailed picture of six recurring topics that highlight the ways in which the speakers made the interpreters visible. These topics are ranked by frequency, with appreciation of interpreters being the most frequently observed, followed by expressions of doubt regarding interpretations, reminders of the practical constraints of interpretation, criticisms of mistranslations, announcements of difficulties in source texts, and apologies to interpreters.

Research on the speaker’s references to interpreters, considered “a new vantage point” in examining interpreter visibility (Bartłomiejczyk, 2017, p. 182), is limited. This study aims to expand knowledge in this area by focusing on consecutive interpreting in Asia, which offers a unique context compared to previous research primarily focused on simultaneous interpreting in the European Parliament. Interpreting is shaped by specific contextual factors (Downie, 2021), and therefore the examination of interpreting in different contexts can provide both common and distinct findings regarding interpreter visibility.

Methods

Material: AIT press conference interpreting

The source material for this study consisted of eight sessions of press conferences held by the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT) between 2006 and 2012, collectively referred to as the AIT Interpreting Corpus. This corpus was compiled with the aim of expanding the conference interpreting data available from Asia, as previous studies utilizing naturalistic data have predominantly utilized the Premier Press Conference Interpreting corpus from mainland China (Bendazzoli, 2018). The American Institute in Taiwan serves as the representative of the United States government in implementing its policies and pursuing its interests in Taiwan, in accordance with the “One-China” Principle and the Taiwan Relations Act (Wang and Guo, 2021). To effectively communicate the American viewpoint to Taiwan, the AIT occasionally hosts press conferences, with the American Director delivering a prepared address and answering questions from journalists in attendance.

The corpus for this study involved speeches from three AIT Directors, Stephen Young, William Stanton, and Christopher Marut, which were consecutively interpreted from English to Chinese by three professional female Taiwanese interpreters. This mode of interpreting was chosen to enable the subsequent media coverage in Taiwan. The recording of press conferences by the AIT was discontinued after 2012 for undisclosed reasons. As a result, the AIT Interpreting Corpus comprises all publicly accessible video recordings on the AIT’s official websiteFootnote 1. The corpus encompasses a total of 34,943 English words and 35,691 tokenized Chinese words, with a duration of approximately 9 h and 24 min.

It is noteworthy that the contextual factors present in AIT press conferences, such as the speakers, the communicative goal, and the chosen mode of interpretation, create an ideal environment for exploring the level of interpreter visibility. The American Directors, who are seasoned diplomats sent by the US government to work for the AIT, conduct press conferences with the same “communicative goal” as diplomatic talks, which is “to find common ground and develop joint solutions rather than have a confrontational discussion” (Kadrić et al., 2022, p. 94). The interpreting used during these conferences generally falls under the category of diplomatic and political interpreting, which focuses on “the avoidance and de-escalation of conflicts and the cultivation and expansion of friendly relations” (ibid., p. 178).

However, despite sharing certain similarities with diplomatic communication, the context of AIT press conferences presents a less formal and more relaxed atmosphere. As stated by Kadrić et al. (2022), “the formality of the communication context influences the degree to which interpreters are involved in the interaction” (p. 143). This phenomenon has been observed in the AIT press conferences, where the Directors representing the US government have occasionally interacted with Taiwanese interpreters, thereby increasing their visibility. The utilization of consecutive interpreting in the AIT press conferences also plays a part in amplifying the visibility of the interpreters. The physical proximity of the interpreters, positioned alongside the Director, enhances their physical visibility as well as increases the potential for mention by the Director, thereby rendering them more perceptible and acknowledged as communicative participants by the attending audience.

A CA-based, multimodal analytical framework

This study aims to examine the visibility of interpreters by conducting a multimodal conversation analysis that focuses on the speakers’ references to the interpreters and their interpretations. The methodological framework utilized is based on Conversation Analysis (CA), which originated in the 1970s as a means to analyze verbal meaning-making and to gain insight into the inner mechanisms of social interactions (Sacks et al., 1974). Over time, the scope of CA has expanded to encompass the analysis of nonverbal resources in human communication (Goodwin, 1981; Linell, 1998; Schegloff, 2007). The integration of nonverbal semiotics, such as gaze, gesture, and posture, into CA is deemed imperative given that “nothing that occurs in interaction can be ruled out, a priori, as random, insignificant or irrelevant” (Atkinson and Heritage, 1984, p. 4). Thus, to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of social interaction, it is essential to analyze both verbal and nonverbal resources as an integrated system.

The present study employs a multimodal conversation analysis to examine the interpreter’s visibility for two reasons. First, a CA method is suitable for analyzing the data, as the AIT Director’s references to the interpreters may prompt their responses, leading to a series of “turns-at-talk” (Davitti and Pasquandrea, 2014, p. 376) between the two participants. CA focuses on exactly these sequences of actions to determine how social meaning is negotiated and implemented by all interactants. To demonstrate the visibility of interpreters through the speaker’s references to them, a close examination of the interactions between the two parties is necessary. This analysis reveals not only how the speaker can make interpreters visible, but also how interpreters can contribute as visible and active co-constructors of meaning. Second, as CA acknowledges the role of both verbal and non-verbal communication in constructing meaning, it is important to include a multimodality layer in the analysis. The multimodal findings are expected to complement the verbal cues in relation to the speaker’s references to interpreters and their subsequent responses. Therefore, to provide a comprehensive analysis of the interpreter’s visibility, this study incorporates both verbal and non-verbal elements within a multimodal framework based on conversation analysis, as outlined below:

Step 1: Delimiting the data within the corpus

This study focuses on the speaker’s references to interpreters and their output during the press conference. The introductory remarks by the moderator regarding the interpreting service are excluded from the analysis. Given the limited size of the corpus, a manual search was performed using the original video recordings to identify the references made by the speaker (AIT Director) to the interpreters. This manual approach was chosen to ensure the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the data.

Step 2: Delimiting units of analysis

The identified references were meticulously divided into 98 units of analysis through a careful reading process. Each unit of analysis encompasses the speaker’s reference to the interpreter and the interpreter’s potential response, constituting a sequence of actions centered around a specific topic. The duration of each unit of analysis may vary depending on the interpreter’s response to the speaker’s reference and the subsequent exchange of turns. The unit of analysis is considered concluded when the roles of the interpreter and speaker merge again to the extent that the audience cannot distinguish the interpreter as an independent speaker. To facilitate easy location of the units of analysis, they have been tagged with their corresponding time frames within the video recordings.

Step 3: Annotating and transcribing multimodal data

The eight video recordings of the eight press conferences of the AIT were imported into the ELAN annotation tool (Wittenburg et al., 2006) for the purpose of annotating multimodal semiotics. ELAN stands out for its effective data presentation, allowing the annotation of textual, auditory, and visual data from different speakers on different tiers, as shown in Fig. 1. Considering that the video cameras mainly captured the upper body of the AIT Director (refer to Fig. 1), the annotated multimodal resources will primarily focus on the speaker’s non-verbal cues, including gaze, facial expressions, hand gestures, head movement, and body orientation. However, when the interpreter occasionally appears in the footage, their non-verbal information, as mentioned earlier, will also be documented. These multimodal resources can complement the verbal output and provide a clearer illustration of how the speaker made the interpreter visible to the audience, as well as how the interpreter themselves achieved visibility. The annotated units of analysis were exported to MS Word files and transcribed into a readable format based on the conventions established by Jefferson (1983) and Mondada (2007) (refer to the Appendix for transcription conventions), ensuring that multimodal semiotics were synchronized with their corresponding utterances.

Step 4: Identifying topics

The extracts, which include both verbal and non-verbal information transcribed from the video recordings, were analyzed from a micro-analytical perspective. The aim was to identify distinct topics related to the interactions between the speaker and interpreter. Each extract was assigned a single overarching topic to represent the situations in which the interpreters became visible due to the speaker’s references. The identified topics were presented quantitatively to demonstrate the degree to which interpreters became visible at AIT. Furthermore, a multimodal approach was employed to analyze the identified topics, using representative examples within each category.

Results

Quantitative results

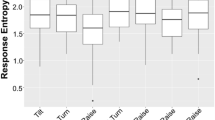

During the eight press conferences, which lasted a total of 9 h and 24 min, speakers referenced or commented on the interpreters or their output 98 times, averaging roughly one mention every 5.8 min. This frequency is notably higher than the observation of “one mention every other day” recorded in the 483 working days of European Parliament debates (Bartłomiejczyk, 2017, p. 181). The frequent reference to interpreters by American Directors in the context of the AIT aligns with the communicative goal of establishing informal and friendly relations between the US and Taiwan. Figure 2 provides a clear illustration of the relative prominence of the various topics identified in the dataset.

The frequency analysis of speaker-initiated references to interpreters in the eight sessions of press conferences revealed that speaker-initiated repairs were the most frequent type of reference, occurring 31 times, followed by speaker’s confirmations of the completeness of the source text information being interpreted (25 times) and humorous interactions with the interpreter (21 times). In contrast, references expressing care towards the interpreters, reminders to journalists about the difficulty of interpreting, and appreciation of interpreters were relatively less frequent, occurring a similar number of times at 8, 7, and 6 instances respectively (see Fig. 2). In accordance with the analytical framework of multimodal conversation analysis, these topics are analyzed using representative examples presented in both verbal and non-verbal layers, aiming to provide a comprehensive and multifaceted illustration of the interpreter’s visibility.

Qualitative analysis

Appreciation

Appreciation in the form of explicit gratitude is expressed by the speaker toward the interpreter’s performance, most commonly at the end of each press conference session. Unlike international conferences that utilize simultaneous interpretating (Bartłomiejczyk, 2017; Diriker, 2004; Duflou, 2012), the seating arrangement of consecutive interpreting, where the interpreter and speaker sit at the same table, allows the speaker to thank the interpreter by name. This is often accompanied by gaze exchange and body language, which brings the interpreter into the limelight, as shown in Fig. 3.

Example 1.

As demonstrated in Example (1), the interpreter responded by laughing and nodding when the Director turned around to appreciate her (Fig. 3.1). Such non-verbal cues can be interpreted as a modest response to open praise in Chinese culture, thereby making the interpreter visible to the present audience. What further enhances the interpreter’s visibility is her subsequent response in turn 2. During this interaction, she maintained eye contact with the speaker, nodded again (Fig. 3.2), and stated, “So, I will skip this.” This non-rendition, along with the interpreter taking full ownership of the text, signifies a shift in footing. The concept of footing, introduced by Goffman (1981) in his participation framework, explains how communicative participants align with each other and adapt their participation in conversation. By not translating the content and changing her footing from a “reporter” to a “responder” in the reception format (Wadensjö, 1998), the interpreter became an active participant in the interaction. Her nonverbal expressions, including shaking her head and laughing (Fig. 3.3), further contributed to her recognition by the bilingual journalists, who were also amused by the ongoing interaction between the speaker and interpreter.

Also notable is turn 3, where the Director reiterated his praise of the interpreter, this time in Chinese. This display of language proficiency by the experienced US diplomat emphasizes his capability to switch to a different language for specific communication purposes. Moreover, he physically expressed his appreciation by patting the interpreter on the shoulder, prompting her to once again direct her gaze towards him (Fig. 3.4). These non-verbal interactions hold significance as they offer triangulated evidence of the interpreter’s visibility and the relaxed atmosphere that characterizes interpreting at AIT.

Reminder

Before the Q&A session begins, the Director often reminds journalists to ask questions one at a time and to pause periodically to allow interpreters to catch up. These reminders are based on the potential difficulties posed by consecutive interpreting, as longer speech fragments can overburden the interpreter’s working memory. Unlike the common theme of reminding speakers to slow down their speech, which is frequently observed in European Parliament debates in relation to the constraints of simultaneous interpreting (Bartłomiejczyk, 2017; Duflou, 2012), this was rarely observed in our data. As noted by Kadrić et al. (2022), many diplomats have prior interpreting experience, and therefore often “try to speak in a way that is conducive to interpreting” (p. 152). This is evident at the AIT press conference, where the Directors organize their own speech into short fragments and prompt journalists to follow suit. In delivering this reminder, the Directors may employ humor, acknowledging the potential nervousness induced in interpreters by the presence of multiple cameras (Example (2)).

Example 2.

In addition to the verbal cues, the Director’s nonverbal expressions contribute to the visibility of the interpreter. When addressing reminders to journalists, as demonstrated in turn 1 and shown in Fig. 4, the Director would turn to the interpreter with a smile, acknowledging her presence. This interaction transforms the interpreter from being “the ghost of the speaker” (Kopczyński, 1994) to a visible participant in the discourse, recognized by the audience. In response, the interpreter laughed and delivered a non-rendition, emphasizing the need for cooperation from all journalists (turn 2). This non-rendition, marked by the claim of text ownership, leads to a shift in footing and a change in pronominal reference (Goffman, 1981), where the interpreter switches from the speaker’s “I” to her own “I.” This departure from the norm of interpreting in the first person makes her highly visible (Harris, 1990). However, the visibility demonstrated by the interpreter is contextually appropriate, given the journalists’ response of laughter. Another notable aspect is the Director’s code-switching to Chinese in turn 3, using the interpreter as an icebreaker to create a lighter atmosphere. These interactions between the speaker and interpreter mutually shape the social context, collectively fostering a relaxed and comfortable communicative environment for AIT interpreting.

Confirmation

In our dataset, the term “confirmation” refers to the statements made by speakers to verify that the interpreter has comprehended the source information and accurately translated it into the target language. The Director, who possessed a high degree of Chinese proficiency, was able to assess the interpreter’s performance. When any omitted information was detected, the Director had the ability to reinforce or reiterate it during or immediately following the interpretation, thereby bringing the interpreter visible to the audience.

Example 3.

In Example (3), the Director noticed that the interpreter had omitted the phrase “other targets of opportunity” from the source text. As shown in Fig. 5, before confirming the completeness of the interpretation, the Director turned his head to look at the interpreter while she was delivering her interpretation (Fig. 5.1). The arrangement of consecutive interpreting, with the speaker and interpreter seated side-by-side, allows for eye contact and head movements that direct attention to the interpreter. After the interpretation was completed, the Director drew attention to the omission, prompting the interpreter to promptly acknowledge her mistake (turn 4). In response, the interpreter interjected with “ah” and the Chinese phrase “當然” (“of course”), which served as a floor-holder referencing a previous topic (Liu, 2009). This overlapped with the Director’s additional confirmation of “You got that already?” (turn 5), before the interpreter managed to provide the missing information. The video footage reveals that the Director continuously looked down at the script as he double-checked the completeness of each interpreted segment (Fig. 5.2 and 5.3). This underscores the expectation for accurate and comprehensive interpretation, as well as the role that a bilingual speaker can play in monitoring interpreters in political and diplomatic contexts. These interactions between the speaker and interpreter, observable to the attending journalists, contribute not only to the visibility of the interpreter but also to a more precise and complete rendering of the American voice for the Taiwanese audience.

Repair

Speaker-initiated repairs serve to correct errors or mistakes in the interpretation rather than to confirm the interpreter’s understanding and complete rendering of the source information. As the AIT Directors possess advanced proficiency in the target language and work consecutively with the interpreters, they are well-equipped to detect discrepancies between the original and interpreted versions.

It is important to note that the speaker-initiated repairs identified in our dataset are distinct from the more severe criticisms or blames often encountered in the context of political interpreting, where the speaker may suspect misinterpretation (Bartłomiejczyk, 2017). The presence of speaker-initiated repairs in our data suggests that the interpreter has made a mistake, whether it be factual or a slip of the tongue. These errors frequently arise in the presence of “problem triggers,” such as numbers, proper names, terminologies, culturally-specific items, and acronyms, which can pose challenges for interpreters due to the increased cognitive demands they require (Gile, 2009, p. 188). In response to the speaker-initiated repair, the interpreter may choose to apologize before immediately correcting the mistake. Occasionally, the Director may offer comfort to the interpreter through gestures or physical acts, such as patting the interpreter’s shoulder or signaling that the mistake is inconsequential. These verbal and non-verbal aspects of the speaker–interpreter interactions are crucial in demonstrating the visibility of the interpreter.

Example 4.

Example (4) illustrates how the interpreter was made visible through speaker-initiated repair. In this instance, the Director highlighted the dangers of a lack of effective dialogs between political parties and provided examples of countries that had suffered political crises as a result. Figure 6 shows the close monitoring of the interpreting process by the Director, as indicated by his head movement and shift in gaze towards the interpreter after a 2.12-second pause in her output (Fig. 6.1). The importance of the speaker’s non-verbal behavior should not be underestimated, as it has the ability to direct the audience’s attention towards the interpreter, who was seated beside the speaker.

Upon hearing the interpreter mistakenly say “Ireland” instead of “Iran,” the Director promptly interjected to correct her (turn 3). It is worth noting that the Director initiated the repair twice in Chinese while maintaining his focus on the script (Fig. 6.2 and 6.3). The interpreter, seated beside him, quickly recognized the error and responded emphatically, “IRAN” (turn 4). To provide further clarification, the interpreter chose to become visible by offering apologies twice and delivering a non-rendition that explicitly states, “it is not Ireland, it is IRAN” (turn 4 and 5). These contributions signify the interpreter’s ownership of the text and indicate a shift in footing, demonstrating her transition from a “reporter” to a “responder” in the reception format (Wadensjö, 1998). The speaker’s repair prompted the interpreter to detach herself from the source speaker’s speaking position and assume the role of “an independent persona” (Shlesinger, 1991, p. 152) in the discourse. However, the visibility of the interpreter in such circumstances is considered necessary to ensure the provision of accurate interpretations. In the realm of diplomacy and politics, precision is paramount as word choices are made with great care, and any inaccuracies in interpretation can have significant consequences (Kadrić et al., 2022). Thus, it can be argued that at AIT, the speaker and interpreter engaged in a collaborative effort to ensure precise interpretation and effective communication through their interactions.

Humor

Humor is another significant aspect that is often incorporated into references to interpreters in the source text. US Directors may occasionally employ humorous remarks or jokes to break the ice and reduce interpersonal distance with journalists on-site. This inclusion of the interpreters in the interactions serves to highlight their presence, as illustrated in Example (5).

Example 5.

In Example (5), the AIT Director, who was about to leave his position, drew the attention of journalists who were photographing him while he spoke. He asked the journalists to take a good-looking picture of him and, in doing so, he turned to the interpreter and employed code-switching by uttering a Chinese phrase which meant “Don’t translate this” (turn 1). This was accompanied by his laughter and a gesture of negation in the form of a headshake, as can be seen in Fig. 7 (Fig. 7.1). The verbal and non-verbal output of the speaker worked in tandem to direct the audience’s attention to the interpreter. Instead of remaining in the shadows, the interpreter responded with an interaction-oriented non-rendition: “Remember to use Photoshop to make him look younger” (turn 2). This was also a claim of total text ownership by the interpreter, resulting in her becoming highly visible through a footing shift in the participation framework, as evidenced by her transformation from a mere “reporter” to an active “responder” (Wadensjö, 1998). The video revealed that the Director then laughed and made several waving-down hand gestures to signal the interpreter to stop saying something that might have made him feel embarrassed (Fig. 7.2, 7.3, and 7.4). The entire exchange between the speaker and interpreter was observed by the journalists, who, in the end, also laughed. In this manner, all the participants at AIT seemed to contribute to the interpreter’s visibility as well as fostering a positive and relaxed communicative atmosphere.

Care

Given the length of each press conference, which exceeds an hour, it is not uncommon for the Director to take a moment to remind the interpreter to drink some water as a sign of care and consideration. In Example (6), the Director commended the interpreter’s proficiency in conveying his evasive response to a journalist’s inquiry regarding the details of an agreement reached between a Taiwanese politician and the AIT. He expressed his approval with the remark “very good,” a thumbs-up gesture, and a pat on the interpreter’s shoulder, as shown in Fig. 8 (Fig. 8.1 and 8.2). These non-verbal semiotics complemented the speaker’s verbal cues and served to direct the journalists’ attention to the interpreter. Upon witnessing the Director’s interaction with the interpreter, the journalists present on-site began to laugh. The Director then code-switched to a Chinese phrase meaning “Drink some water” and accompanied it with a body movement of passing water to the interpreter (Fig. 8.3). While the video recording may have limitations in capturing the interpreter’s nonverbal cues in response to the speaker’s actions, the Director’s body language still provides insights into the interpreter’s visibility. The available multimodal resources on the speaker’s part suggest that interpreters working in high-level press conferences are not necessarily relegated to the background, as one might assume. Instead, they can be utilized by the speaker as an icebreaker for specific communication purposes.

Example 6.

Discussion

Insights regarding the interpreter’s visibility with respect to their role

The utilization of authentic data for investigating interpreter visibility promotes a realistic understanding of their role. Contrary to an idealized portrayal that emphasizes invisibility and impartiality in professional metadiscourse, research has demonstrated that interpreters are active participants and contributors to discourse in both community and conference settings. In community interpreting, where interaction plays a crucial role, interpreters are often assigned metaphoric labels that accurately reflect their actual role performances, such as “mediator” (Wadensjö, 1998), “gatekeeper” (Davidson, 2001), “spokesperson” (Angelelli, 2004), “cultural broker” (Crezee and Ng, 2016), and more. In contrast, conference interpreters are traditionally expected to remain unnoticed due to the formal communication protocols and rigid speech registers. However, ample empirical evidence has refuted this notion, demonstrating their active involvement in discourse (Bartłomiejczyk, 2017; Diriker, 2004; Duflou, 2012; Li et al., 2022).

The present study on interpreter visibility in the context of American Institute in Taiwan (AIT) press conferences contributes to the existing body of knowledge on the interpreter’s role and emphasizes the significance of contextual understanding. Interpreters, as demonstrated by their visibility, conform to established general role descriptions that position them as active co-constructors of meaning. However, when examined within the specific context, interpreters at AIT tend to adopt roles such as “ice-breaker” and “rectifier,” which have received limited attention in the literature. The formation of these distinct roles relies on the collaborative efforts of both the speaker and the interpreter within the given context. When responding to the speaker’s expressions of gratitude and humorous remarks, the interpreter plays a crucial role in breaking the ice and fostering a comfortable and relaxed communicative environment. Furthermore, when prompted by the speaker to address errors or omissions, the interpreter takes on the role of a rectifier, providing a more accurate interpretation for the intended recipients. This highlights the importance of dynamically analyzing and understanding the interpreter’s role in relation to the specific communicative context. Downie (2021) suggests that identifying shared and unique features across different interpreting contexts can facilitate theoretical cross-pollination. Therefore, a contextualized analysis of interpreter visibility holds the potential to offer both conventional and innovative insights into their role.

Efficacy of using multimodal conversation analysis to investigate speaker–interpreter interactions in press conference

The discourse in interaction (DI) paradigm holds significant importance in the field of interpreting studies (Wadensjö, 1998), prompting methodological explorations of interpreter-mediated interaction (Davitti, 2019). Multimodal conversation analysis (CA) has gained popularity as a methodological framework within the DI paradigm due to its potential to provide extensive and comprehensive insights into interpreting practice. Scholars have increasingly focused on exploring the interactional dynamics of interpreting using a multimodal CA framework. This is evident in the works of Davitti (2013), Davitti and Pasquandrea (2017), Mason (2012), and others. However, most of the research conducted in this area has been limited to community interpreting, and the application of multimodal conversation analysis to conference interpreting remains unexplored. This can be attributed to the inherent differences between these two types of interpreting. Community interpreting, which involves multiple languages, parties, and interactions, lends itself well to multimodal analysis, as noted by Pasquandrea (2011). On the other hand, the rigid format of press conferences has traditionally limited any form of interaction between the interpreter and the speaker. However, all interpreting discourse warrants a comprehensive examination through a multimodal lens. Therefore, considering that the myth of conference interpreters being invisible has already been debunked, it is crucial to incorporate a multimodal perspective in the analysis to gain a nuanced understanding of the complexity of interpreter-mediated communication.

This study, utilizing the dataset from the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT) interpreting, has demonstrated the efficacy of employing multimodal conversation analysis to scrutinize the interactional dynamics during press conferences. The ability of US Directors to address the interpreter seated next to them presents an opportunity to examine the sequential positioning of non-verbal resources in the speaker–interpreter interaction. Such a multimodal approach serves to provide rich descriptive layers, contributing to an in-depth understanding of interpreter visibility. Specifically, it allows for the exploration of how interpreters are monitored by bilingual speakers and brought into visibility through the speaker’s head movements and gaze shifts during interpretation, which can replace explicit verbal cues. Additionally, the speaker’s utilization of hand gestures (e.g., thumbs-up), facial expressions (e.g., laughing), and body language (e.g., patting the interpreter’s shoulder), either in conjunction with their verbal references to interpreters or following the interpreters’ responses, enhances the understanding of interpreter visibility beyond the verbal aspects. Similarly, the interpreter’s non-verbal cues, such as their gaze exchanges with the speaker and nodding, can triangulate the results of their uttered non-renditions to confirm that interpreters at political press conferences are not passive conveyors of information but rather active participants in the discourse.

Conclusion

This study has provided a comprehensive examination of the issue of interpreter’s visibility through a multimodal conversation analysis approach in the context of AIT press conference interpreting. The examination of speaker’s references to interpreters offers a novel perspective on this long-standing topic and presents empirical evidence that challenges the conventional expectation of political and diplomatic interpreters to remain unobtrusive and adhere to the speaking position of the source speaker (Kadrić et al., 2022). The results of this investigation demonstrate that AIT Directors may periodically draw attention to the interpreters through various means, and that the interpreters are able to respond as active participants in discourse. The sequential positioning of both verbal and nonverbal semiotics in speaker–interpreter interactions contributes to the visibility of interpreters, the accuracy of interpretations, and the creation of a relaxed communication atmosphere.

Notwithstanding the theoretical and methodological implications, this study also has several limitations that need to be acknowledged. Firstly, the scope of the provided examples is limited. Secondly, the findings related to the speaker’s references to the interpreters were primarily obtained from a single source, Stephen Young, who participated in six recorded press conferences. Given the limited public data available and the possibility of idiosyncratic behavior, it is challenging to generalize these findings to the broader context of AIT press conference interpreting. Besides, it is acknowledged that a more comprehensive understanding of the interpreter’s visibility in the AIT context would necessitate future research that incorporates both interpreted data and perception data from both interpreters and interpreting users on this topic.

Data availability

The excerpts analyzed in this article have all been included. However, the complete set of transcriptions documenting speaker–interpreter interactions is currently unavailable as it is being edited and utilized for an ongoing research project.

Notes

The press conference interpreting of the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT) is freely available in both transcript and original video formats on the official AIT website. The photos presented in the examples of this article are screenshots taken from the video recordings of the following press conferences:

-

(a)

Press conference for Director Stephen Young in Taipei on 3 May 2007, https://web-archive-2017.ait.org.tw/en/officialtext-ot0707.html (accessed 10 July 2023);

-

(b)

Press conference for Director Stephen Young in Taipei on 8 May 2008, https://web-archive-2017.ait.org.tw/en/officialtext-ot0806.html (accessed 10 July 2023)

-

(c)

Press conference for Director Stephen Young in Taipei on 26 June 2009, https://web-archive-2017.ait.org.tw/en/officialtext-ot0913.html (accessed 10 July 2023).

-

(a)

References

AIIC (1999) Practical guide for professional conference interpreters. https://aiic.org/document/547/AIICWebzine_Apr2004_2_Practical_guide_for_professional_conference_interpreters_EN.pdf. Accessed 12 December 2022

Anderson RB (1976/2002) Perspectives on the Role of Interpreter. In: Pöchhacker F, Shlesinger M (eds) The interpreting studies reader. Routledge, London, p 209–217

Angelelli CV (2004) Medical interpreting and cross-cultural communication. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Arumí M, Vargas-Urpi M (2017) Strategies in public service interpreting: a roleplay study of Chinese–Spanish/Catalan interactions. Interpreting 19(1):118–141. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.19.1.06aru

Arumí M, Vargas-Urpi M (2018) Annotation of interpreters’ conversation management problems and strategies in a corpus of criminal proceedings in Spain: the case of non-renditions. Translation Interpreting Stud 13(3):421–441. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.00023.aru

Arumí M, Vargas-Urpi M (2019) When non-renditions are not the exception: a corpus-based study of court interpreting. Babel 65(4):478–500. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.00103.var

Atkinson JM, Heritage J (1984) Structures of social action: studies in conversation analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Baraldi C (2012) Interpreting as dialogic mediation: the relevance of expansions. In: Baraldi C, Gavioli L (eds) Coordinating participation in dialogue interpreting. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, p 297–326

Bartłomiejczyk M (2017) The interpreter’s visibility in the European Parliament. Interpreting 19(2):159–185. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.19.2.01bar

Bendazzoli C (2018) Corpus-based interpreting studies: past, present and future developments of a (wired) cottage industry. In: Russo M, Bendazzoli C, Defrancq B (eds) Making way in corpus-based interpreting studies. Springer, Singapore, p 1–19

Cheung AK (2012) The use of reported speech by court interpreters in Hong Kong. Interpreting 14(1):73–91. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.14.1.04che

Cheung AK (2014) The use of reported speech and the perceived neutrality of court interpreters. Interpreting 16(2):191–208. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.16.2.03che

Cheung AK (2017) Non-renditions in court interpreting. Babel 63(2):174–199. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.63.2.02che

Cheung AK (2018) Non-renditions and the court interpreter’s perceived impartiality: a role-play study. Interpreting 20(2):232–258. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.00011.che

Cirillo L (2012) Managing affective communication in triadic exchanges: interpreters’ zero-renditions and non-renditions in doctor-patient talk. In: Kellett CJ (ed) Interpreting across genres: multiple research perspectives. EUT Edizioni Università di Trieste, Trieste, p 102–124

Crezee IH, Ng EN (2016) Introduction to healthcare for Chinese-speaking interpreters and translators. John Benjamins, Amsterdam

Davidson B (2000) The interpreter as institutional gatekeeper: the social linguistic role of interpreters in Spanish-English medical discourse. J Sociolinguistics 4(3):379–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9481.00121

Davidson B (2001) Questions in cross-linguistic medical encounters: the role of the hospital interpreter. Anthropol Qly 74(4):170–178. https://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2001.0035

Davitti E (2013) Dialogue interpreting as intercultural mediation: interpreters’ use of upgrading moves in parent–teacher meetings. Interpreting 15(2):168–199. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.15.2.02dav

Davitti E (2019) Methodological explorations of interpreter-mediated interaction: novel insights from multimodal analysis. Qual Res 19(1):7–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794118761492

Davitti E, Pasquandrea S (2014) Enhancing research-led interpreter education: an exploratory study in Applied Conversation Analysis. Interpreter Translator Trainer 8(3):374–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2014.972650

Davitti E, Pasquandrea S (2017) Embodied participation: what multimodal analysis can tell us about interpreter-mediated encounters in pedagogical settings. J Pragmatics 107:105–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2016.04.008

Diriker E (2004) De-/Re-contextualising simultaneous interpreting: interpreters in the Ivory Tower? John Benjamins, Amsterdam

Downie J (2017) Finding and critiquing the invisible interpreter–a response to Uldis Ozolins. Interpreting 19(2):260–270. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.19.2.05dow

Downie J (2021) Interpreting is interpreting: why we need to leave behind interpreting settings to discover Comparative Interpreting Studies. Translation Interpreting Stud 16(3):325–346. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.20006.dow

Duflou V (2012) The “first person norm” in conference interpreting (CI)–some reflections on findings from the field. In: Jimenez Ivars MA, Blasco Mayor MJ (eds) Interpreting Brian Harris: recent developments in translatology. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main, p 145–160

Duflou V (2016) Be(com)ing a conference interpreter: an ethnography of EU interpreters as a professional community. John Benjamins, Amsterdam

Gile D (2009) Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training, 2nd edn. John Benjamins, Amsterdam

Goffman E (1981) Forms of talk. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia

Goodwin C (1981) Conversational organization. Interactions between speakers and hearers. Academic Press, New York

Harris B (1990) Norms in interpretation. Target 2(1):115–119. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.2.1.08har

Jefferson G (1983) An exercise in the transcription and analysis of laughter. Tilburg University Department of Language and Literature, Tilburg

Kadrić M, Rennert S, Schäffner C (2022) Diplomatic and political interpreting explained. Routledge, New York

Kopczyński A (1994) Quality in conference interpreting: Some pragmatic problems. In: Lambert S, Moser-Mercer M (eds) Bridging the gap: empirical research in simultaneous interpretation. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, p 87–99

Li R, Cheung AK, Liu K (2022) A corpus-based investigation of extra-textual, connective, and emphasizing additions in English-Chinese conference interpreting. Front Psychol 13:847735. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.847735

Linell P (1998) Approaching dialogue. talk, interaction and contexts in dialogical perspectives. John Benjamins, Amsterdam and Philadelphia

Liu B (2009) Chinese discourse markers in oral speech of Mainland Mandarin speakers. In: Xiao Y (ed) Proceedings of the 21st North American conference on Chinese linguistics (NACCL-21), vol 2. Bryant University, Rhode Island, p 358–374

Mason I (2012) Gaze, positioning and identity in interpreter-mediated dialogues. In: Baraldi C, Gavioli L (eds) Coordinating participation in dialogue interpreting. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, p 177–200

Metzger M (1999) Sign language interpreting: deconstructing the myth of neutrality. Gallaudet University Press, Washington, DC

Mondada L (2007) Multimodal resources for turn-taking: pointing and the emergence of possible next speakers. Discourse Stud 9(2):195–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445607075346

Ozolins U (2016) The myth of the myth of invisibility? Interpreting 18(2):273–284. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.18.2.06ozo

Pasquandrea S (2011) Managing multiple actions through multimodality: doctors’ involvement in interpreter-mediated interactions. Lang Soc 40:455–481

Pease A, Pease Cheung J, Cheung AK (2018) Formal ontology for discourse analysis of a corpus of court interpreting. Babel 64(4):594–618. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.00054.pea

Pöchhacker F (2016) Introducing interpreting studies, 2nd edn. Routledge, London and New York

Roy CB (2000) Interpreting as a discourse process. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Sacks H, Schegloff EA, Jefferson G (1974) A simplest systematics for the organization of turn taking in conversation. Language 50(4):696–735. https://doi.org/10.2307/412243

Schegloff E (2007) Sequence organization in interaction: a primer in conversation analysis, vol 1. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Shlesinger M (1991) Interpreter latitude vs. due process: simultaneous and consecutive interpretation in multilingual trials. In: Tirkkonen-Condit S (ed) Empirical research in translation and intercultural studies. p 147–155

Wadensjö C (1998) Interpreting as Interaction. Longman, New York

Wang M, Guo Y (2021) “美国在台协会”涉台活动的历史考察(1979—2019) [A Historical Survey of Taiwan-related Activities of the “American Institute in Taiwan” (1979–2019)]. Taiwan Res 3:32–41

Wittenburg P, Brugman H, Russel A, Klassmann A, Sloetjes H (2006) ELAN: a professional framework of multimodality research. In: Proceedings of LREC 2006, fifth international conference on language resources and evaluation. European Language Resources Association, Paris

Zhang W, Xu C (2021) Visibility of Chinese ad hoc medical interpreters through text ownership: a case study. Linguistica Antverpiensia New Ser Themes Translation Stud 20:136–158. https://doi.org/10.52034/lanstts.v20i.604

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Faculty Reserve Grant of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (P0043559).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: RL. Supervision: AKFC. Validation: KL. Writing—original draft: RL. Writing—revising and editing: KL. Data transcription and analysis: RL and AKFC.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. The AIT (American Institute in Taiwan) interpreting data, similar to the interpreting data of European Parliament debates, Chinese Premier Press Conference, and similar events, belongs to the public domain. The data, including transcripts and original video formats, can be freely accessed from official websites for various purposes, including academic research. Informed consent is thus not applicable in the context of our specific study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, R., Liu, K. & Cheung, A.K.F. Interpreter visibility in press conferences: a multimodal conversation analysis of speaker–interpreter interactions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 454 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01974-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01974-7