Abstract

Detecting depression on social media has received significant attention. Developing a depression detection model helps screen depressed individuals who may need proper treatment. While prior work mainly focused on developing depression detection models with social media posts, including text and image, little attention has been paid to how videos on social media can be used to detect depression. To this end, we propose a depression detection model that utilizes both audio and video features extracted from the vlogs (video logs) on YouTube. We first collected vlogs from YouTube and annotated them into depression and non-depression. We then analyze the statistical differences between depression and non-depression vlogs. Based on the lessons learned, we build a depression detection model that learns both audio and visual features, achieving high accuracy. We believe our model helps detect depressed individuals on social media at an early stage so that individuals who may need appropriate treatment can get help.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression is considered one of the most severe health threats and has become an important problem in society (Üstün et al. 2004). Because depression is one of the main factors in suicide ideation (Ghosh et al. 2021), a number of scholars attempted to address depression as one of the key topics in our society. The WHO (World Health Organization) reported that more than 264 million people being diagnosed with clinical depression in 2020Footnote 1.

One of the most problems in addressing depression is that capturing an early stage group of depression is complicated and comprehensive (Kim et al. 2020). To address it, a number of researchers focused on social media channels with data-driven approaches, which can be used as a clue for identifying depressed individuals (Devineni et al. 2018; Gui et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2013). Compared to data collected in controlled laboratory settings, social media data can be useful in capturing and observing general depression patterns in the wild (Huang et al. 2020). For example, Wang and colleagues (Wang et al. 2013) developed a depression detection model based on user tags and texts on Sina Weibo, a popular social network service in China.

However, although prior scholars have provided valuable insights into understanding social media posts (e.g., text Lee et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2013 and image Gui et al. 2019; Reece and Danforth, 2017) in analyzing depression, little attention has been paid to investigating how depression can be detected in a video, which both includes audio and visual information about an individual. Instead of looking at a static image captured at the moment, a video can provide comprehensive information about individuals detecting or analyzing depression (He et al. 2022). Moreover, videos have demonstrated a greater ability to evoke emotions compared to other forms of media content, such as images or texts (Lee et al. 2023).

In line with this, the purpose of this study introduces a depression detection model that utilizes both audio and visual features extracted from YouTube videos. To this end, we first collected depression-related and non-depression-related video logs (vlogs) uploaded to YouTube. Note that many users give testimonies of their depression symptoms in depression-related vlogs. Hence we can easily find depressed individuals on Youtube by searching depression-related vlogs. We then analyze audio and visual features extracted from the vlogs to investigate the differences between depression and non-depression vlogs. Using both audio and visual features, we build a machine learning model which efficiently detects depression (over 75% accuracy). Our in-depth analysis reveals that the features related to the intensity of voice and smile are significant predictors in detecting depression. We believe the proposed model helps detect depressed individuals on social media toward allows people who may need appropriate treatment.

Related work

Depression detection using social media data

By using data collected from social media, diverse patterns of depression can be captured in a real-world situation (Huang et al. 2020). Hence, many scholars have developed a depression detection model using social media data, including comments, tags, and posts (Deshpande and Rao, 2017; Gui et al. 2019; Tsugawa et al. 2015). For example, (Gui et al. 2019) utilized a multimodal approach that uses both text and image on Twitter posts for depression detection. (Deshpande and Rao, 2017) built a machine learning model to detect depression using emotional features extracted from posts on Twitter. (Tsugawa et al. 2015) applied a topic modeling method to identify depressed individuals. While these studies have focused on detecting depression using text and image in social media data, little attention has been paid to a depression detection model using video data on social media.

Depression detection using video

With the recent advancements in computer vision and signal processing techniques, there have been significant efforts in developing depression detection models using non-verbal (behavioral) signals (Muzammel et al. 2020; Rodrigues Makiuchi et al. 2019; Yang et al. 2016, 2017). For example, (Muzammel et al. 2020) developed a CNN-based model to detect depression using acoustic characteristics of vowels and consonants extracted from videos. They found that fusing vowels and consonant features efficiently recognize depression. (Yang et al. 2016) utilized both acoustic and visual features to build a decision tree-based depression detection model. (Oureshi et al. 2021) developed a gender-aware depression severity estimation model and revealed that incorporating gender information significantly enhances the performance of depression severity estimation. (Rodrigues Makiuchi et al. 2019) used a BERT to extract features from input text and built a CNN-based deep learning model that fuses acoustic, visual, and text modalities to detect depressed individuals. These studies have developed depression detection methods using video data. However, the used datasets in prior work were developed in a laboratory setting. Hence the previous models may not capture the usual behavior of depressed individuals in the wild (Huang et al. 2020). On the contrary, we collected video data from a large-scale video-oriented social media, Youtube, and proposed and evaluated a machine learning model to detect depression using audio and visual features.

Methodology

Data collection

We first searched YouTube videos that were uploaded from 1st January 2010 to 31st January 2021 using Youtube Data APIFootnote 2. We used the following search keywords for finding depression and non-depression vlogs across Youtube. The keywords are selected under the guidance of mental health specialists.

-

Depression Vlog: ‘depression daily vlog’, ‘depression journey’, ‘depression vlog’, ‘depression episode vlog’, ‘depression video diary’, ‘my depression diary’, ‘my depression story’, etc.

-

Non-depression Vlog: ‘daily vlog’, ‘grwm (get ready with me) vlog’, ‘haul vlog’, ‘how to vlog’, ‘day of vlog ’, ‘talking vlog’, etc.

We then utilized youtube-dlFootnote 3, a popular open-source library, to download the queried videos. As a result, we could obtain 12,000 videos. Note that we only considered videos recorded in English.

Data annotation

We recruited five annotators who carefully watched each video for correct annotation to label collected videos into depression and non-depression vlogs. For the depression vlogs, the annotators first identified whether the given video has a ‘vlog’ format (Correia et al. 2018) where one person speaks directly to the camera. An example of the ‘vlog’ is illustrated in Figure 1. Then, the annotators labeled the given video as a depression vlog if the speaker shares their current state of depression symptoms at the moment of recording, such as talking about their symptoms, current moods, pills they are taking, etc. We provide strict and detailed guidelines to ensure all annotators identify the same criteria. To assess the inter-coder reliability, we recruited an additional annotator to code 100 vlogs (i.e., 20 vlogs for each annotator) and computed the Cohen’s kappa score with the other five annotators. The resulting mean kappa score with the other five annotators was 0.8, indicating a significant level of agreement. Note that we filtered out the vlogs of people who suffered from depression but have already overcome it.

For the non-depression vlogs, the annotators only checked whether the given video has a ‘vlog’ format since the non-depression vlogs have diverse topics. As a result, our final annotated vlog dataset consists of 568 depression vlogs and 463 non-depression vlogs. Note that no single video appears both in depression and non-depression vlogs. We illustrate our data collection and annotation process in Figure 2. Note that we followed all the anonymization processes guided by the Institutional Review Board (IRB)Footnote 4.

Feature extraction

Audio features

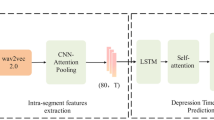

To extract audio features from a given vlog, we employ OpenSmileFootnote 5, an open-source toolkit for audio processing, with the extended Geneva Minimalistic Acoustic Parameter Set (eGeMAPS) (Eyben et al. 2015). Based on the prior works which studied acoustic characteristics of depressed people, (Al Hanai et al. 2018; Ellgring and Scherer, 1996; Fuller et al. 1992; Jia et al. 2019; Solomon et al. 2015; Tamarit et al. 2008; Vicsi et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2019), we first extract eight low-level acoustic descriptors (LLDs), including Loudness, Fundamental Frequency (F0), Spectral Flux, etc., for each frame in a vlog. Note that we consider only a single frame per second (i.e., FPS=1). We then aggregate frame-level audio features into video-level features by calculating the mean of each audio feature in a vlog.

Visual features

We utilize FERFootnote 6, an open-source python library that provides a pre-trained face expression recognition model to extract emotional information from the vloggers. The FER takes an image (frame) as an input and predicts the emotion of the detected face (i.e., angry, disgust, fear, happy, neutral, sad, and surprise). Similar to the audio feature extraction process, the seven emotion scores are first extracted for each frame in the vlog and then aggregated into the video-level by calculating the mean of each video feature in a vlog.

Finally, after the feature extraction process, eight audio features and seven visual features are obtained from a vlog. Note that we only consider frames where a single face is detected.

Depression detection model

We propose a depression detection model based on the eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), one of the popular boosting algorithms (Chen and Guestrin, 2016). XGBoost is an improved variant of GBDT (Gradient Boosting Decision Tree) that utilizes parallel processing and regularization (Chen and Guestrin, 2016). The XGBoost algorithm further improves tree pruning as it makes splits up to the max_depth and then starts pruning the tree backwards and removes splits beyond which there is no positive gain that further improves tree pruning.

We also considered other machine learning classifiers such as Random Forest (Ho, 1995) and Logistic Regression (Peng et al. 2002), but we selected XGBoost as it outperforms others in our preliminary experiment.

Given a vlog dataset \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}={\{({{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}}}_{i},{y}_{i})\}}_{i = 1}^{n}({{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{m},{y}_{i}\in \{1...c\})\) with n vlogs, m extracted features (i.e., audio/visual features), and c classes (i.e., positive when the given video is depression vlog, negative otherwise), the classification task can be generalized as follows:

where \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) is the predicted class for the i-th vlog, fk is the k-th independent tree, K is the number of trees, and fk(xi) is the prediction score given by the k-th independent tree on the features extracted from the i-th vlog.

Then, the objective function of our model, \({{{\mathcal{L}}}}(\phi )\), can be calculated as follows:

where l is the squared error loss function between the predicted class \(\hat{{y}_{i}}\) and the target class yi, and ∑kΩ(fk) is the regularization term that penalizes the complexity of the model. Note that \({{\Omega }}(f)=\gamma T+\frac{1}{2}\lambda | | w| {| }^{2}\), where λ and γ controls the penalty for the number of leaves T and magnitude of the leaf weights w, respectively.

Analysis

This section analyzes the extracted audio and visual features to investigate whether there are differences between depression and non-depression vlogs. To quantify the statistical differences between two groups (i.e., depression vs. non-depression), we conduct the T-test.

Audio features

Loudness and fundamental frequency (F0)

In prior work, it has been reported that loudness and F0 of the depression group are lower than those of the non-depression group (Wang et al. 2019). Also, the F0 is known to be affected by a person’s mood, perturbations, anxiety, and personality traits associated with their depressive status (Ellgring and Scherer, 1996). As shown in Table 1, the depression vlogs show lower loudness than the non-depression vlogs (p < 0.001), and the F0 of the depression vlogs is lower than non-depression vlogs (p < 0.001), which are in line with prior work. Our data-driven analysis confirms the audio characteristics of depressed individuals discussed in previous work.

Harmonics-to-Noise Ratio (HNR)

The HNR quantifies the amount of additive noise in the voice signal. The prior work has shown that the HNR has a negative relation with depression (Jia et al. 2019). As shown in Table 1, the mean HNR of depression vlogs is lower than that of the non-depression vlogs (p < 0.001).

Jitter & Shimmer

The Jitter, a physiological-related feature, has a positive relationship with anxiety (Fuller et al. 1992; Vicsi et al. 2012). Also, the high Jitter value can be obtained from the patients who suffer from severe depression with high suicide risk (Ozdas et al. 2004). As shown in Table 1, the mean Jitter of the depression vlogs is higher than that of the non-depression vlogs (p < 0.001). Some scholars found that Shimmer is lower in depressed individuals than non-depressed individuals (Nunes et al. 2010). However, in our experiment, we find no significant difference in Shimmer between the two groups (p = 0.613).

Second Formant (F2)

The formant frequencies (e.g., F1, F2, and F3) that are associated with muscle tension in the vocal track affect depression state (Al Hanai et al. 2018). In particular, the F2 is one of the major discriminators of depression (Stasak et al. 2019). As shown in Table 1, the depression vlogs have the lower mean value of F2 than that of the non-depression vlogs (p < 0.001). Note that the result can be linked to prior work that found a noticeable reduction of F2 value in the depression group (Flint et al. 1993).

Hammarberg Index

The Hammarberg Index is the intensity difference between the peak intensity in a lower frequency band (i.e., 0–2 kHz) versus a higher frequency band (i.e., 2–5 kHz). The Hammarberg Index is also used for emotion recognition and analysis task (Tamarit et al. 2008). As shown in Table 1, the mean value of the Hammarberg Index of the depression vlogs is higher than that of the non-depression vlogs (p < 0.001), implying that there is a more significant difference in the maximum intensity between lower frequency band and higher frequency band in depression vlogs.

Spectral Flux

The Spectral Flux measures spectral change between two successive frames, calculated by comparing the power spectrum for one frame against the previous frame, i.e., the frame-to-frame spectral shape variance. As shown in Table 1, the Spectral Flux of the depression vlogs is lower than that of the non-depression vlogs (p < 0.001). This may be because the depressed speech is highly steady than the voice of a healthy individual (Solomon et al. 2015).

Visual Features

The prior emotional reactivity experiment has revealed that depressed people tend to feel less happiness (Rottenberg et al. 2005) and more sadness (Rottenberg, 2005) than non-depressed people. As shown in Table 2, the mean happiness of the depression vlogs is lower than that of the non-depression vlogs (p < 0.001), whereas the mean sadness and fear of the depression vlogs are higher than those of the non-depression vlogs (p < 0.001). Note that there are no significant differences in neutral (p = 0.434), surprise (p = 0.183), and disgust (p = 0.256), between the depression and non-depression vlogs.

Experiments

Experimental settings

As shown in Table 3, we implement a stratified 8:2 split for the train and test sets. We next learn the proposed model with the train set and validate it with the test set. Note that all the features are normalized before training, and the train and test sets do not share YouTube channels.

For the model optimization, hyper-parameters are tuned using a grid search based on the 10-fold cross-validation. There are two general parameters considered, which are type type of model to run at each iteration (booster) and the number of cores in the system (nthread). We also consider three booster parameters to control over-fitting, which are the minimum sum of weights of all observations required in a child node (min_child_weight), the maximum depth of a tree (max_depth), and the minimum loss reduction required to make a further split on a leaf node (gamma). And the loss function to be minimized (objective) is considered as a learning task parameter. Finally, booster as ‘gbtree’ which means tree-based models, nthread as 1, min_child_weight as 0.2, max_depth as 5, gamma as 0.9, and objective as ‘binary:logistic’, which means logistic regression for binary classification, returns predicted probability, were applied to the model.

For performance comparisons, we also consider other well-known classifiers as the baseline: Logistic Regression and Random Forest, which have been widely used in depression detection in the prior work (Dibeklioğlu et al. 2015; Ding et al. 2019; Samareh et al. 2018; Tasnim and Stroulia, 2019). We evaluate each model using the 10-fold cross-validation for each set, and we take the average Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and weighted F1 score as evaluation metrics.

Model performance

Overall performance

Overall, the proposed model shows accuracy, recall, precision, and F1 as 75.85%, 78.18%, 76.79%, and 77.48%, respectively. We also considered other classifiers such as Random Forest (Ho, 1995) (67.41% of accuracy, 70.00% of recall, 69.46% of precision, and 69.83% of F1) and Logistic Regression (Peng et al. 2002) (68.41% of accuracy, 67.04% of recall, 68.24% of precision, and 69.70% of F1), but we only report the proposed XGBoost-based model as it performs better than others.

Modality-based analysis

To examine the effectiveness of each modality (i.e., audio and visual) for detecting depression, we perform a modality-based analysis. Table 4 summarizes the model performance in three different settings (i.e., Visual Only, Audio Only, and Audio+Visual) in which the models trained with each modality.

The model trained with audio features performs better (62.32% of accuracy, 65.08% of recall, 70.69% of precision, and 67.77% of F1) than the model trained with visual features (58.94% of accuracy, 63.03% of recall, 64.66% of precision, and 63.83% of F1). This implies that the audio features are more helpful than the visual features in depression detection, which is in line with the prior work (Mundt et al. 2007; Pampouchidou et al. 2016). Moreover, the model performance significantly improves when we use both visual and audio (i.e., Audio+Visual) features. Thus, we believe that considering both modalities can effectively enhance the robustness of the model than depending on just one modality.

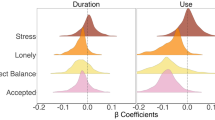

Gender-based analysis

We next investigate how different gender shows different performance in detecting depression. To this end, we train and test two other models using vlogs data with only male and female speakers, respectively. Table 5 shows the performance comparison across different gender. As shown in Table 5, the model for female depressive speakers shows higher performance than the one for male speakers, which implies that female depressive speakers tend to be more distinctive than male depressive speakers in terms of their speech and facial expressions in vlogs. By identifying the unique features and cues associated with depression in a specific gender, we can develop more targeted approaches to detecting depression in this population, and ultimately improve the accuracy and effectiveness of depression screening and diagnosis.

Important features on depression detection

We further investigate which features play essential roles in depression detection with the importance of the feature. As shown in Figure 3, which is calculated by the average gain across all splits of the feature, the score of feature importance is mostly under 0.10. The variation value of loudness peaks per second (i.e., Var. of loudness (Peaks/s)) is turned out to be the most important feature. This implies that the variance of loudness peaks of speakers is a predictor in detecting depression. Among the visual features, the facial expression of happiness plays a vital role in depression detection. Overall, the intensity of voice and happiness revealed in a face are the key indicators in detecting depression.

Concluding discussion

In this paper, we proposed a depression detection model that utilizes audio and visual features of individuals. We collected vlogs from YouTube and annotated them according to ‘vlog’ format. And we used OpenSmile and FER api to extract audio and visual features from the vlogs. We next statistically analyzed the audio and visual features of the vlogs to investigate the differences between depression and non-depression groups. Based on the lessons learned, we trained and evaluated the proposed model, achieving over 77% F1-score. We believe the proposed model helps detect depressed individuals on social media so that it can help people who may need timely treatment.

As academic contributions, we highlighted vlogs, as one of the preliminary resources for detecting the early stage of depression. Presenting the status of mental health in early stages can allow clinicians and experts to aid potential mental illness patients effectively. Thus, the proposed approaches including vlog and deep learning techniques can play a notable role in addressing this issue. In addition, our work contributes to the development of early warning systems for detecting depression using multimodal data sources, such as audio and visual features extracted from vlogs. This can lead to further research in the field of mental health, particularly in exploring the potential of social media platforms as a resource for detecting early signs of depression. Lastly, we presented notable data-driven evidence of vlog as one of the valuable and comfortable resources for both academic and practical researchers. This study also examines that integrating social media and multimodal approaches is one of the prominent research issues.

However, there are several limitations in this study that need to be acknowledged. Firstly, the depression dataset used in this research consists of individuals who have self-identified as depressed and actively share their experiences on social media. As a result, our sample may not fully capture individuals who are in the early stages of depression or those who have not sought professional help. It is important to recognize that the objective of this paper is not to develop a diagnostic tool for early-stage depression, but rather to assist in the development of early warning systems that identify indicators of depression in individuals who are already sharing their experiences on social media. Despite this limitation, we believe that our depression dataset can still provide valuable insights in identifying individuals who may benefit from additional support or intervention, even if they have not received a formal diagnosis of depression from a healthcare professional.

Furthermore, while our depression-detection model achieved an accuracy of 71% and an F1 score of 73% in our evaluation, it is crucial to interpret these results cautiously within the context of early-stage depression detection. The trade-off between false positives and false negatives holds significant implications for the practical application of our model. False positives may lead to unnecessary interventions or distress for individuals incorrectly identified as depressed, while false negatives may result in missed opportunities for early intervention and support.

Lastly, the inability to calculate intercoder reliability due to non-overlapping videos is a noteworthy limitation of this study. Although we provided detailed guidelines to ensure consistent annotation, the absence of a quantitative measure of intercoder reliability makes it challenging to objectively assess the consistency and agreement among annotators.

These limitations highlight the need for caution when interpreting the findings. Further research should aim to address these limitations by (i) including individuals at different stages of depression for early-stage detection, (ii) incorporating diverse data sources and features to reduce both false positives and false negatives, and (iii) labeling overlapping videos to calculate intercoder reliability. Additionally, we will also try to find significant patterns from human behaviors as applying a deep learning model that can help to detect depression in a real-world situation.

Data availability

The data are not available for public access because of privacy concerns but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Al Hanai, T., Ghassemi, M. M. & Glass, J. R. Detecting depression with audio/text sequence modeling of interviews. In Interspeech, 1716–1720 (2018)

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 785–794 (2016)

Correia, J., Raj, B. & Trancoso, I. Querying depression vlogs. In 2018 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT), 987–993 (IEEE, 2018)

Deshpande, M. & Rao, V. Depression detection using emotion artificial intelligence. In 2017 international conference on intelligent sustainable systems (iciss), 858–862 (IEEE, 2017)

Devineni, P., Papalexakis, E. E., Michalska, K. & Faloutsos, M. Mimis: minimally intrusive mining of smartphone user behaviors. In 2018 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM), 568–569 (IEEE, 2018)

Dibeklioğlu, H., Hammal, Z., Yang, Y. & Cohn, J. F. Multimodal detection of depression in clinical interviews. In Proceedings of the 2015 ACM on international conference on multimodal interaction, 307–310 (2015)

Ding X et al. (2019) Classifying major depression patients and healthy controls using eeg, eye tracking and galvanic skin response data. Journal of affective Disorders 251:156–161

Ellgring H, Scherer KR (1996) Vocal indicators of mood change in depression. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 20:83–110

Eyben F et al. (2015) The geneva minimalistic acoustic parameter set (gemaps) for voice research and affective computing. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 7:190–202

Flint AJ, Black SE, Campbell-Taylor I, Gailey GF, Levinton C (1993) Abnormal speech articulation, psychomotor retardation, and subcortical dysfunction in major depression. Journal of Psychiatric Research 27:309–319

Fuller BF, Horii Y, Conner DA (1992) Validity and reliability of nonverbal voice measures as indicators of stressor-provoked anxiety. Research in nursing & health 15:379–389

Ghosh S, Ekbal A, Bhattacharyya P (2022) A multitask framework to detect depression, sentiment and multi-label emotion from suicide notes. Cogn Comput 14:110–129

Gui, T. et al. Cooperative multimodal approach to depression detection in twitter. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 33, 110–117 (2019)

He L et al. (2022) Deep learning for depression recognition with audiovisual cues: A review. Information Fusion 80:56–86

Ho, T. K. Random decision forests. In Proceedings of 3rd international conference on document analysis and recognition, vol. 1, 278–282 (IEEE, 1995)

Huang, Z. et al. Domain adaptation for enhancing speech-based depression detection in natural environmental conditions using dilated cnns. Interspeech 4561–4565 (2020)

Jia, Y., Liang, Y. & Zhu, T. An analysis of voice quality of chinese patients with depression. In 2019 22nd Conference of the Oriental COCOSDA International Committee for the Co-ordination and Standardisation of Speech Databases and Assessment Techniques (O-COCOSDA), 1-6 (IEEE, 2019)

Kim J, Lee J, Park E, Han J (2020) A deep learning model for detecting mental illness from user content on social media. Scientific Reports 10:1–6

Lee, D., Park, S., Kang, J., Choi, D. & Han, J. Cross-lingual suicidal-oriented word embedding toward suicide prevention. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: Findings, 2208–2217 (2020)

Lee, J., Hameleers, M. & Shin, S. Y. The emotional effects of multimodal disinformation: How multimodality, issue relevance, and anxiety affect misperceptions about the flu vaccine. New Media & Society14614448231153959 (2023)

Min, K. Detecting depression on video logs using a machine learning approach. Sungkyunkwan University (2022)

Mundt JC, Snyder PJ, Cannizzaro MS, Chappie K, Geralts DS (2007) Voice acoustic measures of depression severity and treatment response collected via interactive voice response (ivr) technology. Journal of neurolinguistics 20:50–64

Muzammel M, Salam H, Hoffmann Y, Chetouani M, Othmani A (2020) Audvowelconsnet: A phoneme-level based deep cnn architecture for clinical depression diagnosis. Machine Learning with Applications 2:100005

Nunes, A., Coimbra, R. L. & Teixeira, A. Voice quality of european portuguese emotional speech. In International Conference on Computational Processing of the Portuguese Language, 142-151 (Springer, 2010)

Oureshi, S. A., Dias, G., Saha, S. & Hasanuzzaman, M. Gender-aware estimation of depression severity level in a multimodal setting. In 2021 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 1-8 (IEEE, 2021)

Ozdas A, Shiavi RG, Silverman SE, Silverman MK, Wilkes DM (2004) Investigation of vocal jitter and glottal flow spectrum as possible cues for depression and near-term suicidal risk. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 51:1530–1540

Pampouchidou, A. et al. Depression assessment by fusing high and low level features from audio, video, and text. In Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge, 27–34 (2016)

Peng C-YJ, Lee KL, Ingersoll GM (2002) An introduction to logistic regression analysis and reporting. The journal of educational research 96:3–14

Reece AG, Danforth CM (2017) Instagram photos reveal predictive markers of depression. EPJ Data Science 6:1–12

Rodrigues Makiuchi, M., Warnita, T., Uto, K. & Shinoda, K. Multimodal fusion of bert-cnn and gated cnn representations for depression detection. In Proceedings of the 9th International on Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge and Workshop (AVEC), 55-63 (2019)

Rottenberg J (2005) Mood and emotion in major depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science 14:167–170

Rottenberg J, Gross JJ, Gotlib IH (2005) Emotion context insensitivity in major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 114:627

Samareh, A., Jin, Y., Wang, Z., Chang, X. & Huang, S. Predicting depression severity by multi-modal feature engineering and fusion. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 32 (2018)

Solomon C, Valstar MF, Morriss RK, Crowe J (2015) Objective methods for reliable detection of concealed depression. Frontiers in ICT 2:5

Stasak B, Epps J, Goecke R (2019) An investigation of linguistic stress and articulatory vowel characteristics for automatic depression classification. Computer Speech & Language 53:140–155

Tamarit, L., Goudbeek, M. & Scherer, K. Spectral slope measurements in emotionally expressive speech. Proceedings of Speech Analysis and Processing for Knowledge Discovery 169–183 (2008)

Tasnim, M. & Stroulia, E. Detecting depression from voice. In Canadian Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 472–478 (Springer, 2019)

Tsugawa, S. et al. Recognizing depression from twitter activity. In Proceedings of the 33rd annual ACM conference on human factors in computing systems, 3187–3196 (2015)

Üstün TB, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Chatterji S, Mathers C, Murray CJ (2004) Global burden of depressive disorders in the year 2000. The British Journal of Psychiatry 184:386–392

Vicsi, K., Sztahó, D. & Kiss, G. Examination of the sensitivity of acoustic-phonetic parameters of speech to depression. In 2012 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), 511-515 (IEEE, 2012)

Wang J et al. (2019) Acoustic differences between healthy and depressed people: a cross-situation study. BMC Psychiatry 19:1–12

Wang, X. et al. A depression detection model based on sentiment analysis in micro-blog social network. In Pacific-Asia Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 201–213 (Springer, 2013)

Yang, L. et al. Decision tree based depression classification from audio video and language information. In Proceedings of the 6th international workshop on audio/visual emotion challenge (AVEC), 89–96 (2016)

Yang, L. et al. Multimodal measurement of depression using deep learning models. In Proceedings of the 7th Annual Workshop on Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge (AVEC), 53–59 (2017)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2022S1A5A8054322), and supported by the Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT) (No.RS-2023-00254129, Graduate School of Metaverse Convergence (Sungkyunkwan University)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JY, KM and JH conceived the idea. JY, KM, MK and DL performed model experiments and analyses. JY and KM wrote the manuscript draft. EP and JH revised the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee and Institutional Review Board (SKKU IRB No. 2021-09-004).

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This work is an extended version of our preliminary work.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Min, K., Yoon, J., Kang, M. et al. Detecting depression on video logs using audiovisual features. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 788 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02313-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02313-6