Abstract

The legal system of parentage is a mature rule in traditional civil law, encompassing the acknowledgment and denial of parent-child relationships. In China, the parentage legal system outlined in the Civil Code is a guiding provision that requires supplementary operational rules. The rule of parentage presumption, as a crucial component of the parentage legal system, serves as the premise and foundation of the entire parentage system. China’s parentage presumption involves both legal and factual presumptions. To elucidate the legislative intent and objective expression of the legal provisions concerning parentage in the Civil Code, it is necessary to clarify the legal attributes, logic, and effects of parentage presumption. Based on this, deviations in legal application due to inconsistent interpretations by different judges should be identified and adjusted. There exist four challenges in the practical application of the parentage presumption rule within the Chinese judicial system. It is imperative for judges to possess a precise and consistent understanding of these challenges. Article 1073 of the Civil Code and judicial interpretations constitute a remedial mechanism for parentage presumption. However, for this article to yield the intended legal effects, detailed specifications are needed regarding the parties eligible to file denial lawsuits of legitimate children, the grounds for denial, and the statute of limitations. Additionally, the implied recognition system reflected in the legal provision should also be supplemented with unified and applicable regulations to ensure operability within China’s legal system. Only with consistent legislative interpretations and applications can the consistency of legal application in parentage relationships be safeguarded, thereby upholding the authority of the Civil Code.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Chinese Civil Code was promulgated in 2020 and contained 1260 articles. It is divided into seven books: General Provisions, Property, Contracts, Personal Rights, Marriage and Family, Inheritance, and Torts. The Civil Code is a compilation of existing civil laws rather than a completely new creation of private law legislation.

The provisions on the recognition of parentage in the Chinese Civil Code represent a new legal institution, encompassing the legal framework of parentage in Chinese civil law and a significant enhancement of Chinese kinship law. Article 1073, found in Book V of Marriage and Family of the Civil Code, consolidates two aspects related to the acknowledgment or denial of parentage by parents and the recognition of parenthood by adult children into a single provision. The acknowledgment of parentage, often known as the recognition of children born out of wedlock, involves the biological father’s acknowledgment and acceptance of the child born outside of marriage as his own. Denial of parent-child relationship is when parents reject the established parent-child relationship, challenging the legal presumption of such relationship and denying that the child is born within their marriage. Nevertheless, these concepts remain theoretical and require practical guidelines to facilitate their implementation.

Rules of parentage presumption in Chinese laws: an overview

The legal regime of parentage, encompassing both the acknowledgment and denial of parentage, is delineated in two provisions within the Civil Code’s legal system. First, Article 1073 in the Marriage and Family Book of the Civil Code states that

Where an objection to maternity or parentage is justifiably raised, the father or mother may institute an action in the people’s court for affirmation or denial of the maternity or parentage.

Where an objection to maternity or parentage is justifiably raised, a child of full age may institute an action in the people’s court for determination of the maternity or parentage.

Second, Article 39 in the Interpretation (I) of the Supreme People’s Court on the Application of the “Marriage and Family” Book of the Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China, and it states that

Where the father or mother institutes an action in the people’s court for denial of the maternity or parentage and has provided necessary evidence, if the other party has no contrary evidence and refuses a parentage test, the people’s court may determine that the acknowledgment of the party denying the maternity or parentage is tenable.

Where the father or mother or a child of full age institutes an action for determination of the maternity or parentage and has provided necessary evidence, if the other party has no contrary evidence and refuses a parentage test, the people’s court may determine that the acknowledgment of the party requesting the determination of the maternity or parentage is tenable.

As the foundation and cornerstone of the entire parentage regime, the presumption of parenthood rule plays a vital role in the legal framework. While the Civil Code and Interpretation I of the Marriage and Family Law do not explicitly outline the rule of presumption of parentage, the presumption of parentage is employed to determine parentage within the context of maintenance, custody, and inheritance systems. This custom is acknowledged and adhered to by everyone, becoming a wellspring of civil law in the form of customary practice, relieving fathers from the obligation of proving their parent-child relationship to the court after the birth of each child (Xia, 2020).

China has adopted the principles of Roman law regarding presumption, wherein the mother is presumed based on the child’s birth and the father is presumed based on the mother’s marriage. Regarding the essence of the presumption, children conceived or born during a marriage are considered legitimate children (Wang and Meng, 2020). Children born during a marriage or within 300 days of their divorce are regarded as legitimate children (Jiang, 2007). Children born through artificial means are also considered legitimate children (Cheng, 1999). According to Article 1071 of the Chinese Civil Code, children conceived or born out of marriage are illegitimate children, who are considered legitimate children and have the same rights as children born within marriage, and it is prohibited for any organization or individual to harm or discriminate against them. China’s matrimonial law community has conducted extensive research on the parentage recognition system, reaching a consensus that it encompasses both the presumption, the confirmation and denial of parentage (Yinlan Xia, 2016). This is closely linked to children’s interests, the truth about their bloodlines, and their benefits, serving as the bedrock for resolving issues related to parentage.

From a judicial practice standpoint, kinship law has recently placed significant emphasis on parentage recognition (Long and Feng, 2022). Since 2001, Chinese courts at all levels have handled 13,127 cases related to parentage, with 9,490 cases (approximately 72.3% of the total) being tried by basic courts. Since 2010, there has been a steady increase in the number of parentage-related family cases handled by courts at all levels in China. In the past five years alone, courts at all levels have dealt with 5,585 parentage-related family cases, with the majority (3,992) concentrated in the primary courts (Wolters Kluwer database, https://law.wkinfo.com.cn/).

These figures reveal significant points. Parentage disputes in China involve complex factors, and parties seldom reach private settlements, leading to the majority of cases being brought before the courts for resolution. In recent years, there has been a notable rise in the number of parentage cases, especially at the judicial trial level, indicating that parentage has become a prominent legal issue garnering increased attention. Given the intricacies of parentage cases, a robust legal foundation is essential to ensure fair and just decisions.

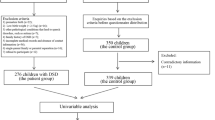

The parentage system established by Article 1073 is relatively new, and despite its potential, it faces certain challenges, which require further research. The application of this law should be updated to align with current societal needs and serve its legal objectives effectively. This essay aims to explore the enhancement of Article 1073 in the Chinese Civil Code through both theoretical and practical perspectives, examining how legal interpretation approaches can transform it from a mere principle provision to a functional and operational one. Hence, conducting an research into the parentage presumption, confirmation and denial outlined in Article 1073 of the Chinese Civil Code, gathering and analyzing relevant cases, identifying current issues, and subsequently enhancing the parentage system of the Civil Code to ensure its full efficacy becomes imperative. That is exactly what this article will explore.

Parentage presumption law

What is a parentage presumption?

Presumption is the foundation of the parent-child relationships. In legal terms, a presumption encompasses both the underlying facts and the presumed facts, which is a process where the parties establish the underlying facts to ascertain the presumed facts and thereby produce specific legal consequences (Zhong, 2015). What lies at the core of adjudication? It is just a process in which the judge establishes a presumption, with the parties presenting evidence of the underlying facts, enabling the judge to reach a factual determination and subsequently make a legal presumption. Any discrepancy in how the facts are ascertained can have a profound Butterfly Effect on the application of the law and the allocation of interests among the parties, potentially leading to an erroneous outcome. Thus, when the facts are unclear, the judge should rely on the burden of proof to investigate and ascertain the facts for proper application of the law. This process of presumption constitutes adjudication. In summary, the presumption is the link between the facts and the law.

Presumption norms possess the characteristics of credibility, compellability, and rebuttability. Credibility results from a scientific model of presumption, where the party invoking the presumption presents evidence to establish the underlying facts, and the opposing party fails to provide counter-evidence, allowing the adjudicator to directly affirm the presumed facts. Compellability involves the direct acceptance and determination of facts based on legal norms once the facts are clear and proven. The adjudicator does not rely on personal judgment but rather applies established legal rules. Rebuttability signifies that after the party invoking the presumption proves the underlying facts, they may face rebuttal from the opposing party. This can involve providing counter-evidence against the foundational facts supporting the presumption or presenting contrary evidence to refute the presumed facts, all aimed at challenging the validity of the presumed facts.

Presumptions can be classified as either legal or factual, depending on their basis. The presumption of parentage is an accurate presumption, rooted in life’s conventions and experiences, and is also a legal presumption explicitly outlined in the Marriage and Family Law and judicial interpretations. Whether factual or legal, a presumption serves as a tool for judges to ascertain facts when the truth or falsehood of certain points is uncertain. In the absence of evidence to prove the existence or non-existence of parentage, judges utilize a combination of factual and legal presumptions to determine the presence of parentage, thereby safeguarding the interests of the parties involved and society’s interests related to parentage.

Presumption, based on the principle of being refutable while allowing for exceptions of being irrebuttable, follows a logical rule grounded in probability. Irrefutable presumptions are exceedingly rare and only applicable in a minute number of cases. For instance, within the California Evidence Code of 1965 in the United States, Section 621 stipulates the presumption of legitimacy for children born to a woman living with her husband. According to this provision, as long as the husband is capable of procreation, children born to the wife while living together with the husband are presumed to be legitimate (Ladd, 1977). The irrefutable nature of this presumption of parentage primarily arises from the fact that regulations concerning parent-child relationships in various countries, such as the United States, are designed to reflect their societal policies and protective interests. Given the societal significance of parent-child relationships, these presumptions are meant to remain stable and impervious to refutation.

The legal presumption of parent-child relationships under Article 39 of the Interpretation (I) of the Marriage and Family Book of China’s Civil Code is a rebuttable presumption (Zhang, 2015). The unfavorable presumption arising from the refusal to undergo a parentage test is based on a high probability in logical terms. Beyond safeguarding the stability of parent-child relationships, the primary objective is to protect the rights of interested parties to ascertain the existence of parentage and ensure the authenticity of the bloodline. According to this provision, when one party asserts the confirmation of a parent-child relationship and the other party refuses a parentage test without presenting contrary evidence, the parent-child relationship is presumed to exist. If other evidence demonstrates that a different individual is the biological father of the child, the presumed “existence” of the parent-child relationship can be overturned to ensure the genuineness of the blood relationship.

The legal logic of the parentage presumption

Legal logic refers to the process of logical reasoning employed to derive specific legal conclusions (Chu, 2011). There may be three types of logical relationships between underlying facts and the existence of parent-child relationships: causal relationships, incompatible relationships, and subordinate relationships. It is through these three relationships that a judge can accurately determine whether the actions of the parties conform to legal presumptions. The general elements of legal logic comprise the major premise, the minor premise, and the conclusion. The process of adjudication by a judge involves the application of legal logic to reason and arrive at a conclusion. In this process, the major premise consists of legal provisions and common principles based on everyday experience, the minor premise involves the determination of facts, and the conclusion represents the judgment’s outcome (Li, 2017). For example, Article 1070 of the Civil Code states that “Parents and children are entitled to inherit each other’s property.” Therefore, if John is confirmed to be Charles’s son, he automatically gains the right to inherit from Charles. The logical process involves a minor premise that aligns with the major premise, indicating that the underlying facts are compatible with the law. Consequently, the conclusion is drawn that John can rightfully inherit from Charles. This logical reasoning demonstrates that the presumption is firmly based on factual evidence and legal provisions.

In Chinese laws, the presumption of parentage is a legal inference that should adhere to the principles of logical reasoning. The judge establishes the connection between the facts of the parent-child relationship and the probability of parentage through the legal logic of the presumption of parentage. Specifically, the major premise is based on the Civil Code and the Interpretation I of the Marriage and Family Book, the minor premise consists of the factual evidence, and the conclusion determines whether parentage exists or not.

In a parentage presumption, the focal point is whether or not parentage exists. Formulating the presumption itself may not be challenging, but determining the underlying facts is where the complexity lies. According to Interpretation I of the Marriage and Family Book, there are three conditions for the presumption of parentage:

-

One party has evidence of parentage

-

The other party has no proof to the contrary

-

The other party refuses to take a parentage test

In essence, this legal provision closely resembles the conditions of the underlying facts. However, relying solely on these three conditions as the major premise of logical inference could potentially lead to erroneous judgments. Even if one party presents evidence to prove the non-existence of parentage, and the other party does not refute it and no parentage test is conducted, it does not necessarily establish the fact that parentage does not exist. This legal presumption primarily pertains to the allocation of the burden of proof in the presumption of parentage, rather than the underlying factual aspect. The factual basis of the parentage presumption should revolve around whether both parents have engaged in factual behaviors establishing a parent-child relationship with the child.

The determination of the underlying facts for the presumption of parentage must be clear. If the underlying fact is that the woman had sexual relations with the man during the conception period, parentage can be presumed. However, if the underlying fact is that, during the conception period, despite cohabitation, the man did not have sexual relations with the woman (such as due to being away on a business trip), or the man is infertile, or the woman had sexual relations with another man during the conception period, then parentage might be presumed not to exist. Conversely, if parentage does not exist, it is because the woman did not have sexual relations with the man, or the man is infertile, or another person had sexual relations with the woman, rather than solely relying on the absence of contrary evidence or the lack of results from a parentage test.

Here is an example. There is a case involving Mr. and Mrs. Smith, who have a child named Jim. When Jim turned five, Mr. Smith noticed that Jim didn’t resemble him, but bore a striking resemblance to Mrs. Smith’s ex-boyfriend, Tom. To establish Jim’s parentage, Mr. Smith conducted a parentage test, which conclusively confirmed that Jim is not his biological son. Subsequently, Mr. Smith filed a lawsuit, seeking to prove the father-son relationship between Tom and Jim and demanding compensation from Tom for the child support expenses incurred over the past five years. During the trial, Mr. Smith requested both Tom and Jim to undergo a parentage test, but Tom refused. After due consideration, the court dismissed Mr. Smith’s lawsuit. The judges reasoned that although Mr. Smith presented evidence supporting the lack of a biological relationship between him and Jim, Tom provided no contradictory evidence and refused to participate in the parentage test. While it may appear that the three mentioned conditions are met, they do not constitute the foundational fact of a father-son relationship between Jim and Tom. The foundational fact can only be established based on reasonable belief that Mrs. Smith and Tom engaged in a sexual relationship during a relevant period Jim’s birth. Relying solely on the three mentioned conditions to infer the father-son relationship between Tom and Jim is unreasonable. It’s akin to randomly selecting a man and demanding him to be the child’s father without any biological link, and presuming him to be the father if he declines to undergo a parentage test, which is clearly illogical. Therefore, the determination of parentage must rely on a clear foundational fact. The legal provisions are merely presumptive rules based on the foundational fact, but they cannot replace the foundational fact itself in determining parentage. Even if the three presumptive conditions are met, adherence to the foundational fact is crucial, and the order of importance cannot be reversed.

Parentage presumptions and China’s fertility policy

The Three-child policy in China was announced on 31 May 2021 during a meeting of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party. In 2023, the Sichuan Provincial Health Care Commission issued the Measures on the Administration of Birth Registration Services in Sichuan Province, an administrative regulation that became effective on 15 February 2023. The primary amendments in the policy are as follows: First, marriage is no longer a requirement for fertility registration. Second, the previous birth limits have been lifted. Third, birth registration procedures have been simplified. The elimination of the marriage requirement represents the most significant change in the policy.

The birth regulations in Sichuan Province can reflect China’s attitude toward childbirth. The Chinese laws have gradually simplified the procedures for fertility, especially by removing the requirement for marriage registration to have children. However, the impact of these policies on the parent-child relationship law, specifically Article 1073 of China’s Civil Code, is evident. These policies eliminate the requirement that applicants must be married, allowing anyone to apply for birth registration for their children. Unmarried women can also have children, and they should be treated similarly to married women in terms of childbirth. So who exactly is the child’s father? This problem will become more uncertain, making the determination of parent-child relationships less aligned with blood ties.

Generally, for parent-child relationships, especially the parentage relationship between father and child, the law presumes based on the mother’s marital status. In other words, the person who gives birth is recognized as the mother, and on this basis, the mother’s legal spouse is presumed to be the child’s father. Under the new regulations, with no requirement for marriage, a situation arises where the child’s father could be anyone, as long as the mother acknowledges and the presumed father agrees. This acknowledged man can become the child’s legal father, and legal rights and obligations of a parent-child relationship are established between them. This kind of parent-child relationship may not align with reality, potentially leading to errors in determining parent-child relationships. If this man later decides not to be the child’s father, he can file a lawsuit to deny the parent-child relationship under Article 1073 of China’s Civil Code, which is not beneficial for the child’s upbringing. Clearly, China’s current legal approach leans toward prioritizing family stability as an incentive for encouraging childbirth, but the lack of authenticity in blood ties may become a significant factor in the instability of parent-child relationships.

On the other hand, as more and more non-authentic parent-child relationships emerge, there will likely be a substantial increase in lawsuits requesting confirmation or denial of parent-child relationships based on Article 1073 of China’s Civil Code. This article becomes more practical. However, it is still a principle-based regulation, only informing parties that they can file a lawsuit to deny parent-child relationships but not providing guidance on how to proceed. If the number of cases increases significantly, it is evident that relying solely on principle-based regulations is insufficient. Therefore, it is essential to improve the operational rules for Article 1073, making it crucial to have parentage presumption laws that protect the scientific and honest nature of blood ties.

Four application issues of parentage presumption

Inconsist conditions of initiation of parentage testing procedures

Lv v. Le Brothers

In December 2016, the plaintiff, Lv’s father, Le, tragically passed away in a work-related accident. As Le’s son, Lv took charge of the compensation matters with the assistance of his two uncles, who are Le’s blood brothers. However, due to Lv and Le having different family names, the Social Insurance Fund Management Centre requested Lv to provide proof of his relationship with Le or the results of a parentage test while reviewing the death benefit. In response, Lv decided to commission the Guangdong Forensic Institute to conduct a parentage test. He obtained a certificate from the Dongguan Public Security Bureau and underwent the parentage test at the Dongguan Hospital. The results of the test confirmed that Le and Lv were indeed father and son. However, Lv’s uncles contested this identification conclusion, arguing that it was unilaterally commissioned by Lv, and they raised objections about the sampling process, stating that there was only one staff member present during the identification. Consequently, they expressed their disapproval of the identification conclusion. In August 2017, Lv’s uncles sought to pursue a new parentage test, but the court denied their request.

After the trial, the court confirmed the parentage of Lv and Le based on the valid judicial appraisal procedure, credible appraisal conclusion, and supporting notarial certificate. Thus, Lv’s parentage was officially established. The defendant opposed conducting a re-parentage test for Lv and Le. However, it should be noted that both parties involved in the case, as well as the court, have the authority to initiate the parentage test procedure when necessary (“Xiang 0523 Civil Case First Instance 1353, 2017”).

The parentage presumption depends on how parentage testing begins

The judiciary and the parties involved acknowledge the significance of parentage testing as a vital method for confirming blood relations. Parentage test genetic testing has been widely employed for many years, serving as crucial evidence in legal proceedings to establish parental rights and confirm the identity of family members. Due to its high accuracy, judges heavily rely on parentage testing when determining the establishment of parentage, making it a primary factor in proving the presumption of parentage (Zhang, 2013).

An analysis of several parentage cases highlights that litigants may refuse parentage testing for various reasons. Moreover, the majority of countries and regions have restrictions on parentage testing due to human rights concerns (Lowenthal, 2012). In cases where the judge needs to ascertain the existence of parentage between the parties, but cannot rely solely on direct evidence from parentage test results, the presumption of parentage plays a crucial role in making a factual determination.

The procedure for initiating parentage testing is determined at the discretion of the adjudicator and may vary from court to court. Some courts require the consent of both parties and the expert’s personal involvement in taking the samples for parentage testing. In such cases, parentage testing conducted by one party alone is not considered as evidence. However, other courts may adopt a more flexible approach, accepting the results of a parentage test conducted by one party as evidence unless effectively refuted by the other party (“Yu 05 Civil Retrial No. 17, 2016”).

Courts have varying requirements for initiating parentage proceedings, leading to differences in the application of the presumption of parentage. Parentage testing and the presumption of parentage are two interdependent methods used by judges to establish parentage. If the procedure for initiating a parentage test is less stringent, the test’s scope and probative effect may increase, making the presumption of parentage less applicable. Conversely, if the procedure for initiating a parentage test is more stringent, the application of the presumption of parentage expands. These differing approaches can result in contrasting parentage outcomes, leading to various consequences. To ensure consistency and fairness, it is necessary to standardize the conditions for initiating parentage testing. This can be achieved by specifying the procedure for starting parentage testing in the Supreme Court’s judicial interpretation, thus creating a standardized practice across individual courts.

Various evidence requirements for the plaintiff

Mingqi Su v. Xiaoming Li

In 2001, Mingqi Su and Xiaoming Li entered into a non-marital relationship. Mingqi Su gave birth to a son in Nanjing while Xiaoming Li was not present. Subsequently, the Nanjing hospital issued a Medical Birth Certificate, identifying the child as A Su, with Mingqi Su and Xiaoming Li listed as the mother and father, respectively. In July 2011, Mingqi Su filed a lawsuit alleging that Xiaoming Li was not fulfilling his responsibilities as A Su’s biological father and sought an order for him to provide child support. During the legal proceedings, Su requested a parentage test, but Li refused to comply.

The court of first instance determined that the Medical Birth Certificate provided by Mingqi Su was unilaterally issued and not officially approved. Without a parentage test, Mingqi Su failed to present the required evidence to establish the existence of a biological relationship between Xiaoming Li and A Su. Consequently, Li could not be presumed to be A Su’s biological father, resulting in the dismissal of Mingqi Su’s claim. Following Mingqi Su’s appeal, the court of second instance discovered that Xiaoming Li had denied cohabiting or engaging in a sexual relationship with Mingqi Su, yet he could not explain why he provided his ID card for A Su’s birth certificate. At last, the court upheld Mingqi Su’s claim. Xiaoming Li made alimony payments to A Su because he couldn’t furnish evidence to counter Mingqi Su’s confirmation and couldn’t reasonably justify his refusal to cooperate with the parentage test.

The primary reason for the divergent conclusions reached by the two courts stemmed from their differing interpretations of what constitutes “Necessary Evidence.” The first court maintained that the birth certificate was not an essential piece of evidence, whereas the second court upheld its significance. The Chinese Civil Code and Interpretations do not clearly define what constitutes necessary evidence of parentage.

The necessary evidence in parentage presumption

The Interpretation of the Marriage and Family Book emphasizes that the plaintiff has presented the requisite evidence to establish the parent-child relationship, a critical prerequisite for the judge to presume parentage. The presumption of parentage can only be in favor of or against the plaintiff if the evidence provided fulfills the criteria for proving or disproving parentage. In practical terms, issues related to privacy can be challenging to substantiate. Matters such as the absence of sexual relations between the alleged father and mother, or the mother’s relations with other men, can impact the presumption of parentage. Nevertheless, these facts often remain private and hard to prove. Consequently, the type of evidence needed to support these underlying facts may vary depending on the judge’s discretion. As long as the party initiating the parentage claim can persuasively convince the judges that these circumstances might be true and that there is a possibility (or lack thereof) of parentage between the parties, the burden of proof shifts accordingly. When one party requests a parentage test, and the other party refuses, the plaintiff’s request will be supported.

In practice, the judge should take into account the following factors when assessing the necessary evidence.

-

The judge should meticulously examine the evidence presented by both parties, and the evidence put forth by the party claiming parentage should be highly compelling. In this case, the birth certificate does not directly establish the blood relationship between Xiaoming Li and A Su. Nevertheless, as it undergoes legal procedures and is scrutinized by official authorities, it holds significant probative value.

-

The trial judge should listen to both parties, analyze their statements, assess their reasonableness, and evaluate their credibility.

-

Examine the reasons behind the unwilling party’s refusal to undergo parentage testing. Considering that current parentage testing technology has a 100% accuracy rate for denying parentage and a 99.99% accuracy rate for confirming parentage (Lai, 2013), the judge must carefully evaluate the grounds for rejecting parentage testing and form an internal conviction accordingly.

-

The well-being of the child, including their health, development, and property, is at the core of every parentage presumption. As a guiding principle, the judge should consistently prioritize the child’s upbringing, family life, and overall best interests when making decisions.

Inconsistent favourable parentage presumption conditions

A Chen v.B Wang

In February 1997, A Chen and her husband C Gan gave birth to a daughter named D Gan. Shortly thereafter, C Gan was convicted of a crime, and A Chen began living with someone else, while D Gan did not reside with A Chen. In February 1999, B Wang adopted an abandoned baby girl, naming her D Wang, and registered her as his daughter in the household registration. A Chen learned in March 1999 that her daughter had been adopted by B Wang. Following the tragic death of C Gan in a traffic accident in 2012, a forensic laboratory conducted a parentage test using blood samples from C Gan and D Wang, confirming that C Gan was indeed D Wang’s biological father. Subsequently, A Chen brought a lawsuit to the court of first instance, seeking to establish her mother-daughter relationship with D Wang. Throughout the proceedings of the first and second trials, A Chen requested to conduct a parentage test with D Wang, but D Wang consistently refused. In the second trial, D Wang stated that her current family was taking good care of her, and she was not willing to live with A Chen. The court of first instance held that A Chen’s request to establish her mother-daughter relationship with D Wang lacked factual basis, leading to the dismissal of A Chen’s lawsuit. The court of second instance upheld the original judgment (“Wuhan Hanyang District Intermediate People’s Court Civil Final No. 00116, 2014”).

In this case, although the plaintiff has presented certain evidence, the opposing party’s refusal to undergo a parentage test is substantial and reasonable, thereby precluding a direct favorable presumption for the plaintiff. The plaintiff, A Chen, has shown knowledge of her daughter, D Wang, being adopted by others and displayed indifference to the matter, which establishes a valid reason for the child’s refusal to participate in the parentage test. The court’s ruling against the plaintiff’s presumption of parentage in this case is justifiable.

Refining the basis for a favourable or unfavourable presumption

According to the provisions of “Interpretation (1) of the Marriage and Family Law,” it is evident that in cases where one party provides necessary evidence to establish a parent-child relationship, and the opposing party lacks contrary evidence but refuses to undergo a parentage test, the People’s Court “may” presume the validity of the claim made by the party seeking to confirm the parent-child relationship. This does not imply an obligatory or mandatory presumption of the claim’s validity. It signifies that the decision to presume the validity of the claim made by the party seeking to confirm the parent-child relationship should also consider factors such as maintaining family harmony and stability, as well as safeguarding the legitimate rights and interests of minors. Therefore, even when the plaintiff provides necessary evidence and the opposing party lacks contrary evidence while refusing a parentage test, the judge is not automatically obligated to favor the presumption of the plaintiff’s position.

The judge’s decision to make a presumption of parent-child relationship in favor of or against the plaintiff is the result of comprehensive consideration. In any presumption of parent-child relationship, the primary consideration should be the best interests of the child, while other factors also encompass biological authenticity and family stability. While biological authenticity is undoubtedly important, the stability of identity pertains not only to family stability but also to societal stability. Pursuing biological authenticity alone, without considering existing family relationships, can undermine the established family dynamics and the parties’ current life interests, and it may also be detrimental to the child’s growth. This is especially true for individuals over the age of 8 who have limited legal capacity; they possess a certain level of expression capability. The judge must give full consideration to the child’s awareness and attitude towards the parentage test, ensuring a reasonable judgment is made.

Article 19 states that

A minor attaining the age of eight is a person with limited capacity for civil conduct, who shall be represented by his or her statutory agent in performing juridical acts or whose performance of juridical acts shall be consented to or ratified by his or her statutory agent, but may alone perform juridical acts which purely benefit the minor or are commensurate with his or her age and intelligence.

The presumption of parentage should strike a balance between honoring the authenticity of biological relationships and ensuring identity stability. However, in practice, the paramount consideration must be the child’s best interests (Xue, 2014). In the absence of parentage test results, judges tend to prioritize maintaining a stable identity, as it fosters a child’s healthy development. While this approach may lead to reasonable decisions in individual cases, it could result in conflicting outcomes within the judicial system, leading to inconsistent rulings. Therefore, when one party refuses to undergo a parentage test, it is necessary to refine the criteria upon which the judge should make a favorable or unfavorable presumption.

Different scope of the plaintiff

Ming siblings v. Xiaoming

In 2020, Liu filed for divorce from Ming, which resulted in Xiaoming, their son, being raised solely by Ming without any alimony from Liu. During the divorce proceedings, Liu admitted that Xiaoming was not Ming’s biological son. In response, Ming requested a parentage test, but Liu refused to comply. As their marriage was ending, Xiaoming continued to be raised by Liu, and Ming was not required to pay child support. Tragically, Ming later passed away in an accident. With both of Ming’s parents deceased, his two brothers, Jian and Shui, along with his two sisters, Li and Ying, became his legal heirs. However, Liu, as Xiaoming’s legal representative, refused to sign the mediation agreement and persisted in asserting that Xiaoming was not Ming’s biological child. This delay complicated the matter of accident compensation. In court, Liu admitted that Xiaoming was not Ming’s biological son, but she still declined to undergo a parentage test even though it was feasible to perform one at that time while Ming’s body was still available for testing. The court determined that Ming and Liu were not legally married, allowing the four siblings of Ming, as his heirs, to bring the lawsuit. Furthermore, according to Article 39 of the Interpretation I of the Marriage and Family Book, the presumption of parentage should favor the plaintiff, indicating that there is no established parent-child relationship between Ming and Xiaoming (“Civil Judgment of the First Instance of Xigong District People’s Court of Luoyang City, Henan Province, No.14, 2015”).

In current judicial practice, there is a practical dilemma arising from the inadequacy of legislation, where courts are faced with either strictly applying the law or expanding the scope of the plaintiff, resulting in conflicting judgments. A rigid application of the law by the court may not always yield the most reasonable judgment, while a decision that grants the plaintiff broader rights may run counter to legal provisions (Liang, 1999). In this case, the court interpreted the scope of parentage plaintiffs in an expansive manner. Although Article 2(1) of Interpretation III of the Marriage Law specifies “either party of the couple” as the subject of denial of parentage claims, this interpretation is aimed at addressing the application of the Marriage Law. Therefore, the mention of denial of legitimate children is articulated in such a way. However, it is important to note that only the law itself, and not judicial interpretation, has the authority to restrict civil rights of parties (Fang and Zhang, 2015). As a result, the provisions in this interpretation regarding denial of legitimate children’s claims should not be narrowly interpreted to refer solely to the husband or wife. In circumstances such as divorce or the death of one spouse, heirs also have the right to file denial of parentage claims.

Expansive legal interpretation or strict application by the law

The subject of parentage determination is the party who exercises the right to request the court to confirm or deny parentage. According to Article 1073 of the Civil Code,

Parents or adult children have the right to request the confirmation of parentage, and parents also have the right to request the denial of parentage.

From this, two points are evident: first, parentage determination involves the plaintiff initiating a lawsuit to seek a judicial alteration of parent-child identity, with a strict approach taken towards the filing of such suits to prevent undue interference by public authority into private civil rights; second, in China, the eligible plaintiffs for parentage determination are explicitly enumerated, and only those who qualify have the right to request the court’s confirmation or denial of the presumption of parentage.

Currently, the existing laws in our country restrict the eligibility to initiate parentage-related lawsuits to parents and adult children, with no standing granted to others. With the plaintiff scope explicitly defined by legislation, judicial practice should comprehensively employ methods such as intent, textual interpretation, and systemic considerations to accurately interpret and apply parentage norms, refraining from arbitrarily expanding the range of eligible plaintiffs. In light of this, a categorization and analysis of plaintiffs in parentage determination lawsuits is essential.

-

Plaintiff in a parentage determination action

-

Parents. Including either spouse of a married couple, either party of a divorced couple, and either party in a cohabiting relationship.

-

Adult children. The reason why minor children cannot become plaintiffs is primarily because the litigation of minors must be conducted by their legal representatives, often their parents. When minor children are already in a stable family relationship, it is generally not advisable to change their parentage for the sake of the child’s best interests, ensuring identity stability. On the other hand, it is unusual for parents to request the court to confirm the parentage of their child with someone else. Therefore, it is more appropriate for the child to independently initiate a confirmation lawsuit when they have full capacity for civil actions and litigation.

-

Child’s other guardians. In the event of the death of both parents of a minor, when it becomes necessary to confirm parentage for the purpose of inheriting the estate of either parent, it should be permissible for the guardian of the child to initiate a lawsuit to confirm parentage. This lawsuit would request the court to confirm the parent-child relationship between the deceased parent and the child, in order to safeguard the child’s inheritance rights. Allowing other guardians of the child to act as eligible plaintiffs expands the interpretation of existing legal provisions (X. Li, 2019). Following the death of both parents of a minor, the child’s guardian is often the person closest to them and most conducive to their growth. From a rights and obligations perspective, the guardian’s role is comparable to that of a “parent,” thus making them suitable plaintiffs.

-

Plaintiff in a parentage denial action

The plaintiffs who challenge parentage denial are primarily parents, including biological fathers and biological mothers. Biological fathers and mothers initiate parentage denial suits mainly concerning children born through assisted reproductive technologies, such as sperm or egg donation and surrogacy. Although these children share a genetic connection with their biological parents, they often do not reside within the family environment of their biological parents. The parent-child relationship established genetically may not align with the emotional bond, and this discrepancy might not be in the child’s best interest (Xue, 2020). Therefore, it is reasonable to allow biological fathers and mothers to act as plaintiffs in parentage denial suits.

Children, regardless of their age, are not eligible to initiate parentage denial lawsuits. This measure is primarily in place to prevent children from using such actions as a means to evade their obligations of supporting their parents. Parents fulfill their responsibilities in raising their children, and in their old age, they may require support from their children. If children could legally sever their parent-child relationship through parentage denial suits, it could jeopardize the rights and protections of elderly individuals. If there is a legitimate need for such a dissolution, it should be pursued by one of the parents in court to legally dissolve the parent-child relationship.

In conclusion, concerning the eligible plaintiffs for parentage confirmation lawsuits, a broad interpretation can be applied. However, for parentage denial lawsuits, strict adherence to the provisions of the Civil Code should be followed. The confirmation of parentage is based on the principle of Blood Relationship Authenticity and Identity Stability, seeking a more appropriate parent-child relationship for the child, aimed at protecting their growth and creating possibilities conducive to their development. This approach aligns with the principle of the Best for Children’s Interests and thus warrants the expansion of the scope of parentage confirmation lawsuits. On the other hand, parentage denial not only destabilizes the parent-child relationship but also potentially places the child in a disadvantaged situation without a caregiver or guardian. Therefore, caution is necessary, and a rigorous application of the law is essential, without arbitrary expansion.

Acknowledgment system fills legal loophole of parentage presumption

The illegitimate children

The Marriage Law of the People’s Republic of China explicitly states that children born out of wedlock should be treated equally, as clearly outlined in Article 1071.

Article 1071 Children born out of wedlock enjoy the same rights as children born in wedlock. No organization or individual may harm or discriminate against them.

The natural father or the natural mother who does not have custody of his or her child born out of wedlock shall pay the child support of the minor child or the child of full age who is incapable of living on his or her own.

There are five main categories of children born outside of marriage, all of whom are considered illegitimate children.

-

Children born to an unmarried biological mother.

-

Children born to biological parents who were unmarried at the time of conception.

-

Children adopted by same-sex couples or born using assisted reproductive technologies.

-

Children presumed to have been born in wedlock but whose paternal or maternal denial is upheld by the court, rendering them illegitimate.

-

Children born out of wedlock is acknowledged by the plaintiff as the biological father and parentage is ascertained, but the acknowledgment is denied by the other “father or mother” and upheld by the court, the child is restored from a legitimate child to a child born out of wedlock.

The parentage presumption, which could otherwise leave a child illegitimate, can be rectified through acknowledgment, allowing the child to be considered legitimate. Therefore, acknowledgment serves as a complement to the parentage presumption.

Acknowledgment of Article 1073, paragraph 1

The Chinese Civil Code does not differentiate between voluntary and compulsory acknowledgment, and the process for both is similar to the procedure for mandatory acknowledgment, which carries legal consequences. An acknowledgment is only considered valid if the court approves it, and its validity hinges on the biological relationship between the father and the child. A father with a blood relationship may request the court to formally recognize him as the child’s biological father.

Voluntary acknowledgment

The Chinese Civil Code approaches the alteration of parentage with great caution. Although there might be certain hindrances to the biological father’s acknowledgment, the effectiveness of confirming parentage can be ensured through legal procedures. For instance, challenges may arise regarding the validity of a biological father’s acknowledgment due to potential errors, deception, coercion, or even instances where the acknowledging individual is aware of the lack of biological connection yet still wishes to proceed with the acknowledgment. However, through the court’s determination of underlying facts and the presumption of a parent-child relationship, the likelihood of such errors can be significantly reduced.

China has established general rules regarding acknowledgment, but for their effective application, specific laws are required to provide clear guidance. Without such clarity, there is a risk of questionable decisions being made. The lack of precise rules and the varying factual interpretations by judges can lead to discretionary practices and inconsistent outcomes in the application of acknowledgment regulations. Therefore, it is essential to establish explicit and detailed rules for acknowledgment to ensure consistency and fairness in legal proceedings.

According to Article 1073, paragraph 1 of the Chinese Civil Code, the act of recognizing and acknowledging a biological child born outside of wedlock as a legitimate child by the birth father essentially amounts to a formal declaration. However, this provision’s lack of specificity regarding different types of acknowledgments, acknowledgment denials, compulsory acknowledgments, and quasi-certification indicates that China’s legal system for acknowledgments is not yet fully comprehensive and well-defined. There is still a need for further development and refinement in the legal framework to address these various aspects of acknowledgment adequately.

This gives rise to an issue where the civil capacity deficiency of the birth father could hinder acknowledgment due to restricted litigation capacity. As acknowledgment carries a personal character, it is generally prohibited for an authorized representative to act on behalf of the signatory. Even when the claimant is a person with limited legal capacity, they must undertake the acknowledgment personally. Whether the court supports this is determined by the judge, guided by the principle of the child’s best interests, while taking into account factors like the child’s preferences, the child’s existing family situation, the birth mother’s caregiving capability, and the birth father’s capacity to provide care. When individuals with limited legal capacity engage in litigation, their appointed representatives should handle the proceedings. If the claimant lacks legal capacity and the birth mother is unable to fulfill guardianship responsibilities, acknowledgment should be obtained with the child’s consent, and litigation initiated by the legally designated representative of the incapacitated birth father.

Compulsory acknowledgment

Although the Civil Code’s Marriage and Family Book does not explicitly mention compulsory acknowledgment, it can be inferred from the text of Article 1073 and the overall intent of the law that China recognizes the concept of compulsory acknowledgment. This concept aligns with practices observed in various countries around the world. According to this article, both the birth father and mother, as well as the child, have the right to initiate a parentage determination challenge. This approach ensures that all relevant parties are given the opportunity to seek clarity and legal recognition of parentage, promoting fairness and protection of individual rights within the family law framework.

Compulsory acknowledgment serves as a protective measure for both illegitimate children and their birth mothers in China. Currently, there are three main legal presumptions for acquiring legitimate children: children born within a parental marriage, voluntary acknowledgment, and children born after a wife remarries following the death of her ex-husband. However, children born outside of marriage often face challenges as the absence of the father may lead to inadequate support and care for the child during their upbringing and education. Compulsory acknowledgment aims to address this issue by providing a legal framework to establish the parent-child relationship and ensure the protection of the child’s interests, even in cases where voluntary acknowledgment is not feasible or available. By recognizing compulsory acknowledgment, China aims to safeguard the rights and welfare of children born outside of marriage and promote their well-being within the family structure.

In many cases, the lack of a protective, educational, and nurturing role undertaken by the father with respect to the child leads to a detriment in the interests of children born out of wedlock. To address this concern, legislation in China has implemented a compulsory acknowledgment system to safeguard the rights of such children. Under this system, both the child and the parents have the right to initiate legal proceedings in court to request the acknowledgment of parentage from the parent who has not fulfilled the nurturing, educational, and protective role, thereby compelling them to assume parental responsibilities. For children born out of wedlock or birth mothers who have not challenged the biological father with a blood relationship, they may file a lawsuit demanding acknowledgment from the biological father, provided there is a blood relationship between them. If a blood relationship is absent, the lawsuit might not find support in the court.

Quasi-positive of the illegitimate children

In the context of parentage determination, the concept of quasi-positive status is as crucial as acknowledgment. The Chinese Civil Code addresses the quasi-positive status of children born outside of marriage, although not explicitly as a provision. Instead, quasi-positive is recognized as a source of kinship law based on social order and ethical customs. In Chinese society, many de facto marriages (Interpretation I of the Supreme People’s Court on the Application of the “Marriage and Family” Book, 2020) exist, and children born within these unions are presumed to be born out of wedlock. Children born outside of marital relationships, if the parents later register their marriage officially, the child is considered born in wedlock, and there is no need for administrative or judicial authorities to confirm the child’s parentage. This recognition of quasi-positive status demonstrates that Chinese laws implicitly acknowledge its existence, even if not explicitly stated in the Marriage and Family Book. By recognizing quasi-positive status, China’s legal system acknowledges the importance of social realities and ethical customs in determining parentage, providing a more holistic approach to addressing the complex dynamics of parent-child relationships in various family arrangements.

Article 1071 of the Chinese Civil Code explicitly acknowledges that children born out of marriage have the same legal status as legitimate children, demonstrating that China does not discriminate against children born out of wedlock. This provision is a clear indication of China’s commitment to ensuring equal protection and treatment for all children, regardless of their birth circumstances. As for the quasi-positive status, while it may not be explicitly outlined in the legal provisions, its recognition through social order and ethical customs reinforces the idea that China’s legal system strives to protect the interests of children born outside of wedlock. The absence of specific operational explanations does not diminish the fact that the legal framework is designed to safeguard the rights and welfare of all children, including those born in various family arrangements. By ensuring equal legal status and protection for all children, China aligns itself with the global trend of legislation that aims to prioritize children’s interests and well-being, regardless of their birth circumstances. This approach reflects a commitment to fairness, justice, and equality in the realm of parent-child relationships, emphasizing the importance of safeguarding the rights of children born outside of marriage similar to those born within a marriage (Coles, 2020).

Denial of legitimate children lawsuit corrects the false parentage presumption

Denial of legitimate children lawsuit of Article 1073, paragraph 2

The presumption of parentage based on parental marriage can sometimes be inaccurate (Wu, 2021). In the legal system, legitimate children are recognized through presumptions rather than deemed, as the former allows for the possibility of rebuttal, unlike the latter, which is conclusive and not open to challenge based on evidence (Zhang, 2012). If parentage is established through an erroneous presumption, a denial challenge can be initiated to seek support. This clarifies that the presumption of parentage only applies to legitimate children and not to illegitimate ones. Article 1073, paragraph 2 of the law outlines the process for a valid denial lawsuit. The denial of parentage litigation is a relatively recent addition to Chinese family law. However, several other countries, such as Germany, Switzerland, France, and Japan, have already implemented similar laws on this matter.

Article 1593 of the Civil Code of Germany: Section 1592 no. 1 applies with the necessary modifications if the marriage has been dissolved by death and within 300 days after the dissolution a child is born. If it is certain that the child was conceived more than 300 days before its birth, this period of time is conclusive. If a woman who has entered into a further marriage gives birth to a child that would be both the child of the former husband under sentences 1 and 2 and the child of the new husband under section 1592 no. 1, it is to be regarded only as the child of the new husband. If the parentage is challenged and if it is finally and non-appealably established that the new husband is not the father of the child, then it is the child of the former husband.

Article 256 of the Civil Code of Swiss: The presumption of parentage may be challenged in court: 1. by the husband; 2. by the child if the spouses cease living together while the child is still a minor. The husband’s challenge is directed against the child and the mother, that of the child against the husband and the mother. The husband has no right of challenge if he consented to impregnation by a third party. The child’s right to challenge parentage is subject to the Reproductive Medicine Act of 18 December 1998.

Article 322 of the Civil Code of French: The action may be brought by the heirs of a deceased person before the expiry of the period within which the deceased person had to act. The heirs may also continue the action already commenced, unless the action has been withdrawn or lapsed.

Article 774 of the Civil Code of Japan: Under the circumstances described in Article 772, a husband may rebut the presumption of the child in wedlock. Article 722: (1)A child conceived by a wife during marriage shall be presumed to be a child of her husband. (2)A child born after 200 days from the formation of marriage or within 300 days of the day of the dissolution or rescission of marriage shall be presumed to have been conceived during marriage. (Determination of Parentage by Court).

The operational rules of denial of legitimate children lawsuit

The plaintiff

Father

There are two types of individuals recognized as fathers who may initiate a legal challenge for the denial of paternity. The first includes those who are presumed to be fathers based on the presumption of marriage. The second consists of individuals who, as a result of the child’s biological mother’s remarriage, are presumed to be the fathers of the child. When either of these two files a legal challenge for the denial of paternity, it has the potential to invalidate the previously established parent-child relationship. In this context, the term Father refers to the individual who has established a factual upbringing and educational relationship by living together with the child. If there is no actual cohabitation between the father and child and no other social connections based on a father-child relationship, they cannot act as plaintiffs in a challenge to legitimacy lawsuit. However, individuals who share a genuine educational and nurturing relationship with the child can act as plaintiffs, representing the child’s interests. In such cases, the child is the defendant, the alleged father is the plaintiff, and the biological mother is considered a third party (“Sichuan Langzhong Court of Civil Final Appeal No. 780, 2014”).

When the father who claims denial of parentage passes away, how should it be resolved? This reference may be Articles 257 and 258 of the Swiss Civil Code, which state.

A child born 300 days prior to the date of dissolution of marriage by death whose biological mother remarries during that period is presumed to be the child of the latter husband; if the parentage of the latter husband is denied, the child is presumed to be the child of the former husband. If the husband dies or loses his capacity during the legal proceedings, the proceedings may be completed by his father or mother, who may exercise his or her rights within one year of known or ought to know the husband’s death or loss of capacity.

There are two things to consider in this situation.

-

To protect the child’s best interests, the father could not deny the mother and child’s relationship unless the mother did not give birth to the child.

-

If a third party seeks to confirm parentage with the child, the father may not bring a second action to deny parentage, which is for saving litigation resources.

The primary reason is that civil law possesses ethical and public aspects. Parentage is not only a familial connection for the children but also a societal link. Once a new parentage is officially acknowledged by the court, the pre-existing parentage is automatically revoked. While placing limitations on challenges to paternal parentage denial, efforts should be made to provide opportunities for the child’s growth, thus establishing parentage relationships that are most conducive to the child’s development.

Mother

The mother is the one who gives birth to the child, and she usually has the most information about the father’s identity. She has a significant interest in the child’s relationship with the father, which makes her eligible to be the plaintiff in a claim for denial of legitimate children. The right of the mother to deny legitimacy is recognized in many countries, including the United States, Russia, and several other nations (Li and Xu, 2008). In the countries and regions mentioned above, if a child is born after the 180th day of marriage or within 300 days of the end of the marriage, it is presumed to be born in wedlock if the husband lives with the birth mother during her pregnancy. In cases where the child is born during the marriage and the mother denies parentage, the plaintiff must provide evidence to prove that the birth mother’s husband is not the biological father.

A mother can make a claim of lack of legitimacy in two ways. The first way is by denying the mother-child relationship between herself and her children, which applies to cases involving egg donors and surrogate mothers who have given birth to children through artificial means (You, 2021b). In this scenario, the mother acts as the plaintiff, and the children are the defendants. The second scenario arises when there is disagreement between the father and the mother regarding the child’s parentage. In this case, the mother acts as the plaintiff, and the father becomes the defendant. Consequently, if the father passes away, there are two ways for the father’s relatives to challenge parentage. One option is for the biological father to initiate a parentage acknowledgment lawsuit to deny parentage to the original father, while the other option is for the mother to file a denial of paternity challenge.

A mother’s denial of legitimate children is limited to the two specific situations mentioned above and should not be subject to broad interpretation. This is due to the inherent aspect of maternity, which naturally favors females and cannot be easily overridden. Generally, a mother cannot assert a denial of legitimate mother-child relationship solely based on the fact of childbirth, unless there is another biological mother who is genetically related and willing to establish a de facto parental relationship with the child, such as in the case of surrogacy. From the perspective of the child’s best interests, allowing a surrogate mother to initiate a denial of legitimacy claim maximizes the benefits for the child.

Parents

To safeguard the child’s best interests, both parents cannot simultaneously deny their parent-child relationship with the child. If both parents are denied, there is a risk that the child may be left without necessary care and upbringing within the family. Clearly, the law cannot endorse such a situation. However, if a third party confirms parentage, it reduces the likelihood of the child being left without proper care. The original parents are not allowed to initiate a denial of legitimacy claim if the children are minors. There is no such restriction for adult children with full legal capacity, meaning both parents can bring a denial of legitimacy action concerning their inheritance rights simultaneously.

Here is a question to consider, which is whether parents can initiate the denial of parentage with their adult children. In my opinion, when parents file a legal challenge for the denial of paternity, seeking to terminate the parent-child relationship with their children, adult children are not eligible to file a legal challenge for the denial of paternity yet. There are two reasons for this. First, adult children are not allowed to sue for the termination of their parent-child relationship with their parents, as clearly stipulated in the current Chinese Civil Code. Second, whether adult children can simultaneously sue to terminate their parent-child relationship with their parents or not, it does not affect the procedure when parents have already filed a legal challenge for the denial of paternity. The willingness of the children to terminate the parent-child relationship can, in fact, be a consideration for the judge’s decision, potentially leading to a judgment that is reasonable for both the plaintiffs and defendants.

Denial reasons

Article 1073 of the Chinese Civil Code does not specify the grounds for filing a lawsuit to deny parentage. According to the Chinese Civil Code’s presumption of parentage laws, children born during a marriage are presumed to be legitimate, and this direct legal provision may lead to disputes. Based on the case data from the China Judgments Online (https://wenshu.court.gov.cn), there have been approximately 13,300 cases related to parentage presumption since 2002. These cases can be categorized into five types based on different causes of action: 5212 divorce disputes, 2801 custody disputes, 1005 child maintenance disputes, 912 inheritance disputes, and 3366 parentage disputes. These five types of cases constitute the vast majority (99.9%) of parentage presumption cases.

From the cases, it is evident that there are two main reasons for denying parentage. Firstly, the father’s infertility (“Beijing Second Intermediate People’s Court Civil Mediation Letter of Second Instance, 2014”). Secondly, the mother’s sexual relations with a third person during conception, including sexual relations with a third person during the marriage (“Chongqing First Intermediate People’s Court Civil Judgment of Second Instance No. 2999, 2008”), sexual relations with a third person before marriage, and cohabitation between the wife and another person in a deteriorating conjugal relationship.

If a party wishes to deny parentage through litigation based on the above two facts, in addition to relying on the substantive provision of Article 1073 of the Civil Code, they must also comply with the general procedural rule of the Chinese Civil Procedure Law, which states: “The one who claims is the one who proves,” meaning that the party claiming denial of parentage must provide evidence. If a party claims infertility, they need to provide evidence of their inability to conceive during the period when the woman became pregnant, such as a medical diagnosis of infertility issued by a hospital. If a party claims that the child’s mother had sexual relations with a third person during conception, they must also provide factual evidence. However, proving cohabitation with another person is often a private matter, and therefore, the burden of proof for the father can be quite challenging.

In practice, judges may make determinations of parentage based on the results of parentage tests, as such tests have a high degree of scientific and objective reliability, which is an important attribute of evidence. However, it is essential to note that a child being born before or after marriage is not a valid reason for denying parentage. For instance, Swiss law upholds this rule to prevent men from evading their maintenance obligations.

Period

Currently, various countries have two main types of legislation concerning the statute of limitations for denial lawsuits of legitimate children.

-

A restrict period

Putting the child’s interests first has become a universally acknowledged principle in kinship law around the world, whereby the authenticity of a child’s bloodline and stable identity takes precedence over the stability of marital unions, as recognized by traditional civil law. For instance, in the Swiss Civil Code, Article 256-3 sets the statute of limitations for denial lawsuits at one year, while Article 1600-2 of the German Civil Code sets it at two years, since the day one becomes aware or ought to become aware that the child is not biologically their own. Both acts specify that parties cannot initiate a denial claim beyond the specified time period, even in cases of inconsistent parentage.

Is a one-year or two-year statute of limitations for matrimonial denial actions reasonable? If the period is too long, it could potentially subject the child to a negative marital and family environment, leading to emotional instability and disruptions in family relations that may adversely affect the child’s development. Therefore, it is crucial to establish parentage as soon as possible to ensure the child’s well-being. On the other hand, if the period is too short, the claimant may not have sufficient time to thoroughly investigate the truth about their biological lineage. Suits challenging parentage should be initiated promptly to seek the truth effectively, but it’s equally important to strike a balance between revealing the blood truth and respecting privacy considerations.

-

An unrestricted period

China adopts this law in accordance with the provisions of Article 196 of the General Principles of the Civil Law, which states that claims for payment of alimony, maintenance, and support are not subject to the statute of limitations.

Article 196 The provisions on the prescriptive period shall not apply to the following claims:

-

(1)

A claim for cessation of infringement, removal of obstacles, or elimination of danger.

-

(2)

The claim of a holder of a real right in an immovable or a registered real right in a movable for restitution of property.

-

(3)

A claim for payment of child support, support for elderly parents, or spousal support.

-

(4)

Any other claim to which the prescriptive period does not apply by the law.

-

(1)

This article should be interpreted in an expansive manner (You, 2021a), implying that it relates to the identity relationship arising from the right to make a claim and is not subject to provisions of the statute of limitations. For instance, similar to the right to file for divorce that allows either spouse to initiate divorce proceedings at any time, the challenge of denial of legitimacy, which is rooted in the father-son identity connection, can be likened to the provisions in the General Provisions of Civil Code and is not bound by lawsuit time limitations. Thus, it becomes evident that a biological father or mother can file a lawsuit for denial of legitimacy at any time after the child’s birth.

Balancing the authenticity of biological lineage and the stability of identity constitutes the paramount principles in parentage determinations. Addressing the legislative theory and judicial practice conundrum concerning this equilibrium, the interim provisions aim to safeguard the stability of parent-child relationships. The Chinese Civil Code, however, lacks explicit regulations regarding the statute of limitations for denial lawsuits of legitimate children, underscoring the legislative emphasis on ensuring the authenticity of biological lineage.

Conclusion and further research

This article outlines Chinese marriage and family law in the Civil Code by analyzing the legal provisions on parentage presumption that emphasize family laws. The enactment of the marriage and family laws has improved family law, but there are still some deficiencies in basic provisions, especially a lack of explicit and refined regulations.

Article 1073 of the Chinese Civil Code and judicial interpretations are important legal bases for parentage presumption. Both the denial of legitimate children and the acknowledgment system require specific operational rules to effectively implement the law. Conversely, without a scientific system of parentage presumption rules and interpretations, it would be challenging to establish a sound parentage system; the two complement each other. However, Article 1073 of the Chinese Civil Code regarding the legal system of parentage is of a principled nature and requires further development of operational rules.

The legal system of parentage is a mature rule in traditional civil law, encompassing the acknowledgment and denial of parent-child relationships. The rule of parentage presumption serves as the premise and foundation of the entire system of legal parentage. Chinese laws on parentage involve both legal presumptions and factual presumptions. To clarify the legal attributes, logic, and effects of parentage presumption, it is necessary to explore and elucidate the legislative intent and objective expression of the legal provisions on parentage in the Civil Code, and to adjust the deviations in legal application caused by inconsistent interpretations by different judges. Currently, there are four issues in the application of the rule of parentage presumption in Chinese judicial practice: inconsistency in the conditions to initiate parentage testing procedures, different interpretations of the evidence provided by the plaintiff, inconsistent conditions for making favorable or unfavorable presumptions of parentage, and varying degrees of strictness in determining the scope of the plaintiff. Judges should have an accurate and consistent grasp of these issues.

The legal system of parentage is a mature rule in traditional civil law, encompassing the acknowledgment and denial of parent-child relationships. To make the parent-child relationship system a complete and comprehensive system, it is necessary to perfect the supporting rules, including operational rules for presumption of legitimate children, acknowledgment of non-marital children, denial of legitimate children, and more. For the denial rules of parentage, specific subjects, grounds for denial, and statute of limitations for denial lawsuits of legitimate children should be further detailed. Additionally, specific rules regarding the implied Recognition system in Article 1073 should be added, including the methods, procedures, and consequences of recognition, in order to provide legal refinement and ensure that parties can utilize Article 1073 of the Chinese Civil Code to establish or deny parent-child relationships.

In conclusion, the interpretation of the legal system of parentage requires drawing on practice, customs, and legal principles, accumulating experience, and formulating specific operational norms to supplement the deficiencies in legislative rules. It is essential to ensure uniform application and adaptability to the Chinese legal system, guaranteeing the operability of parentage acknowledgment or denial lawsuits.

Data availability

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Beijing Second Intermediate People’s Court Civil Mediation Letter of Second Instance. (2014). from https://www.pkulaw.com/pfnl/a25051f3312b07f373680a2be46c8e57838c46f86e01531fbdfb.html?keyword=%E5%B0%8F%E4%B8%BD%E8%AF%89%E5%BC%A0%E6%9F%90%E6%8A%9A%E5%85%BB%E8%B4%B9%E7%BA%A0%E7%BA%B7%E6%A1%88&way=listView

Cheng M (1999) Improve the Legal System of Parent-child Relationship (Outline). Stud Law Bus 4:24–27. https://doi.org/10.16390/j.cnki.issn1672-0393.1999.04.007

Chongqing First Intermediate People’s Court Civil Judgment of Second Instance No. 2999. (2008). from https://www.pkulaw.com/pfnl/a25051f3312b07f3b203c44368db6ce4c336f6fd12d8a53cbdfb.html?keyword=%E6%9D%A8%E6%9F%90%E4%B8%8E%E5%BC%A0%E6%9F%90%E8%BF%94%E8%BF%98%E6%8A%9A%E5%85%BB%E8%B4%B9%E7%BA%A0%E7%BA%B7%E4%B8%8A%E8%AF%89%E6%A1%88&way=listView

Chu F (2011) Para-legal presumptions - the intermediate area between factual and legal presumptions. Contemp Law Rev 5:107–114