Abstract

The heterogeneous market hypothesis states that there are different types of investors with different investment term-structures in the stock market. Based on the hypothesis, we analyze the trading strategies of moving averages with different term structures, and we find that the trading strategies formed by the 1-month short-term moving average with 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, 18-, and 24-month long-term moving averages can gain significant excess returns in the Chinese market. Accordingly, this paper adopts the moving average factor formed by the method of Liu’s to expand the current four-factor pricing model of the Chinese market. The results of spanning regression show that the introduction of the short-term average with a period of 1-month and the long-term moving average with a period of 3- and 12-month can significantly improve the pricing power. The GRS test developed by Gibbons et al. (1989) also shows that the augmented six-factor model with moving average factors can pass the test at the significance level of 5%, and the average absolute value of intercept terms decreases by about 50% compared with the results of the four-factor model. At the same time, under different macro-state dependence, the overall performance of the augmented six-factor model with moving averages is still better than that of the four-factor pricing model proposed by Liu et al.’s. Our main contribution is to introduce double moving average factors to capture the behaviors of investors’ different term structures and add these factors to the most competitive asset pricing model for enhancing the pricing power. It is of great significance to supplement the pricing model in the Chinese market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fama and French’s (2015) famous five-factor pricing model (FF5) is mainly based on the dividend discount model (DDM). After comparing book-to-market ratio (BM), asset-to-market ratio (AM), cash flow-to-price ratios (CP), and earning-to-price ratios (EP), Liu et al. (2019) find that the value factor based on EP can well capture the fundamentals of asset prices in the Chinese market. However, some empirical evidences show that the above famous asset pricing models cannot fully explain the various anomalies in the capital market (e.g., Fama and French, 2015; Liu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2017). According to the behavioral finance theory, investors have heterogeneous beliefs in the market, and not all investors are rational. Due to the existence of irrational factors in the market, the pricing model constructed by irrational factors can better capture the stock market anomalies than fundamental factors. For example, in the US market, the momentum factor of Carhart (1997) has strong explanatory power for abnormal excess returns. In the Chinese market, Liu et al. (2019) also propose a Pessimistic Minus Optimistic (PMO) factor based on turnover rate that can significantly improve the ability to explain anomalies. The PMO factor refers to low turnover rate stock portfolios minus high turnover rate stock portfolios. Specifically, Liu et al. (2019) argue that short selling constraint makes a high turnover rate (greater liquidity) more likely to be accompanied by strong optimism rather than strong pessimism. With the addition of the PMO factor, which has an average annual return of 12% in the Chinese market, most of abnormal excess returns have been fully explained.

The heterogeneous market hypothesis believes that there are different types of investors with various investment term structures in the stock market, such as short-, medium-, and long-term investors. The differences in investor endowments, market information, institutional constraints, and risk preferences result in different trading frequencies in the market. In addition, different types of investors have different understandings and reactions to the same market information, leading to a delay in the complete absorption of this information from the market. Therefore, interactions between different investors may lead to correlations in price changes at different time intervals. Müller et al. (1997) find that the mechanism of interaction between different types of investors in the market is a non-linear process, which leads to specific correlation patterns in short-term prices. In terms of the characterization of heterogeneous markets, Corsi (2009) constructs a simple realized volatility prediction model HAR-RV (Heterogeneous Autoregressive Model for Realized Volatility). This method mainly studies the interaction between different types of investors by measuring the volatility at various time intervals (1 day, 5 days, and 20 days). In addition, from a behavioral finance perspective, gradual information dissemination can lead to underreaction or overreaction by investors, causing their stocks trading at different times, resulting in different trading frequencies in the market. Barberis et al. (1998) believe that the price trend may be slow when investors underestimate new information in their decision-making process. Han et al. (2016) adopt the model of Wang (1993) by replacing uninformed investors with technical traders. Through this modification, they derive the average price trading signals across different frequency term structures, suggesting the presence of investors with various term structures in the market.

The proportion of individual traders in the Chinese market is relatively largeFootnote 1. Due to the limitations of professional knowledge, private information, and other factors, individual traders prefer to trade by learning from the public market news, such as price, trading volume, turnover rate et al. At the same time, given that the difference of personal endowment, information level, institutional constraint, risk preference, and other reasons, these traders have different understandings and response speeds to market information, which also leads to the heterogeneous beliefs in the Chinese market, and ultimately resulting in anomalies with different transaction frequencies. It can be seen that the construction of tradable factors with different frequencies to describe traders’ behavioral decisions is likely to become the key to asset pricing in the Chinese market.

In the stock market, technical analysis can depict the investment preferences of investors with different term structures by setting different time frequencies (Xiang and Lu, 2018; Han et al., 2013). The primary objective of technical analysis is to identify specific price patterns or indicators to forecast future price trends. Therefore, technical analysis methods can capture the interactions between different types of investor relations, which respond to price changes with predictive power. At the same time, investors’ varying degrees of heterogeneity in information reception and feedback result in different market returns for technical analysis with different term structures. Numerous studies find that a stock’s premium or return is closely associated with its historical information (Chopra et al., 1992; De Bondt and Thaler, 1985; Fama and French, 1986; Jegadeesh and Titman, 1993; Lehmann, 1990; French and Richard, 1986; Rubi et al., 2022). Historical price information may contain trend information, which makes it efficient in predicting stock returns. Technical analysis is mainly to judge or predict future trends based on past price information of individual stock. In technical analysis, moving averages are widely used in stock transactions (Han et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2021; Lin, 2018). The essence of moving average is to remove the influence of noise in the stock price time series by smoothing the market price curve, thereby reflecting the main trend of the stock price and providing traders with trend trading signals. While the logic of moving averages is simple, fund managers, stock analysts, and other professional investors use them as trading rules to discover the investors’ behavioral decisions of different term structures in the market (Xiang and Lu, 2018). Therefore, investors’ behaviors with heterogeneous beliefs can be well characterized by constructing moving averages over different periods. Han et al. (2016) point out that individual investors and fund managers use moving averages to judge market trends and guide their trading decisions. Moreover, they demonstrate that by employing moving average strategies with various term structures can achieve significant excess returns in the U.S. market.

As mentioned above, the moving average can act as a signal that mainly reflects the behavioral decisions of heterogeneous investors in different term structures by averaging stock prices over different periods. When investors react to positive market information immediately, the slope of the short-term moving average will be larger. When investors react to positive market information slowly, the long-term moving average will slowly rise. Therefore, the moving average is a tangible expression of the different investors who receive and feedback information at different times, and it can reflect their investment behavior with different investment structures. Since the current asset pricing model cannot fully explain the various anomalies especially the behavioral decisions of heterogeneous investors, and moving average can capture the behavioral decision of investors of different terms in the Chinese market (Antoniou et al., 2013; Han et al., 2016; Xiang and Lu, 2018). Inspired by the above research, this paper aims to explore the pricing power of investment behavioral decisions of heterogeneous investors with different term structures. Moving averages across different term structures are used as proxy variables for the behavioral decisions of these diverse investors. By constructing trading strategies across different frequency periods, we investigate whether the moving average factor can capture the abnormal returns caused by heterogeneous investors in the Chinese market.

Liu et al. (2019) propose a four-factor model, China’s four-factor model (CH4), which mainly covers size factor, market factor, value factor. In addition, to characterize the market sentiment, they use turnover rate to construct a sentimental factor that can well capture the non-fundamental anomalies of the Chinese market. Their result shows that CH4 has a strong ability to explain China’s abnormal returns. However, we wonder whether their four-factor model can explain the anomalies with different term structures formed by heterogeneous investors. Thus, this paper first constructs a four-factor model to analyze the investment anomalies with different term structures in the Chinese market. Meanwhile, on the basis of the four-factor model, this paper introduces a six-factor pricing model based on the formation of moving averages, which expands the research of Liu et al. (2019). The main findings of this paper are:

First, the investment term structures in the Chinese market are diversified. Investors’ behavioral decisions with different investment term structures can obtain excess returns, but short-term investment returns are significantly higher, indicating that investors with heterogeneous beliefs in the Chinese market prefer short-term positive market news rather than long-term value investment.

Second, moving averages with different term structures are factored into the pricing model to capture the trading information of heterogeneous investors. By studying the excess returns of different moving average strategies, we introduce moving average factors with different term structures. To avoid factor redundancy, we introduce two moving average factors derived from double moving trading strategies based on short-term moving average of 1-month and long-term moving averages of 3-, 12-month. These two moving average factors significantly improving the pricing power of the Chinese market anomalies. This may be attributed to the diversity of traders in the Chinese market, who have differences in receiving and processing information, leading to distinct investment cycle preferences (e.g., David and Robert, 1989; Hong and Stein, 1999).

Third, the study considers small-cap stocks, which can comprehensively reflect the asset pricing of all stocks in the market. We find small-cap stocks are more predictable when applying technician analysis. Liu et al. (2019) find that companies in the bottom 30% of market capitalization in China have a “shell effect”. These stocks increase their share prices through market capitalization management methods such as restructuring and mergers. Consequently, they take these stocks out for more accurate analysis. However, the relatively low share prices of the Chinese small-cap companies make them attractive to small and medium investors who prefer speculation. In the Chinese market, retail investors hold a larger proportion, and their decisions certainly will affect the stock prices. At the same time, with the continuous increase in trading volume and proportion, we find that small-cap stocks are playing an increasingly important role in the market. Therefore, we do not exclude this branch out of the entire market.

The main contributions of this research are: 1. We reveal that although the Chinese investors are diverse, mostly prefer short-term trading because short-term portfolios achieve the highest returns. Since the moving average can capture the behavioral decision of investors with different term structures, we use short-, medium-, and long-term moving averages to explore the trading frequency habits of the Chinese investors. 2. We explore the whole sample including the bottom 30% cap stocks that are more profitable than exclude them when using the moving average, indicating that the small-cap stocks are more predictable when applying technician analysis. 3. We introduce moving average factors with different terms that consider the investor’s trading decisions across various term structures. By using moving averages, investors’ trading decisions are reflected at various frequencies, such as short-run fluctuations and long-run trends. This allows our moving average factors to capture the trading features of different term structures, thereby effectively enhancing the pricing power. 4. We reveal the pricing powers of factor models are state-dependent, and we find that the factor model in the best state of GDP and market sentiment outperforms the worst-case state.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section “Literature review” provides a review of the relevant studies, Section “Data” introduces the sample data, Section “Factors construction” discusses factor construction, Section “Empirical analysis” focuses on empirical analysis for the effectiveness of the MA factors, and the conclusion is presented in the last section.

Literature review

As mentioned above, the heterogeneous market hypothesis believes that there are different types of investors in the stock market, and these investors have different understanding and reaction speeds to the same market information, resulting in different trading frequencies in the stock market. While the stock prices can reflect the investors’ decisions, technical analysis can capture the trading decisions of investors with different terms in the market (Han et al., 2013; Xiang and Lu, 2018). Hence, technical analysis methods can be used to capture the interaction among different types of investors, and use this relationship to predict the price trends. This may enable technical indicators of different term structures to gain excess returns in trading. Among many technical indicators, moving average analysis (MA) is efficient and favored by traders. The main reasons are as follows: First, moving averages are easy to understand and have a certain trading logic. Second, stockbrokers, financial reporters, and fund managers are favored by moving average to analyze trends of prices, so they often use their preferences and personal understanding of moving average as trading rules (Han et al., 2016). Third, the behavioral finance theory believes that the psychology of individual investors is related to the price momentum trend of market transactions, and the moving average strategy in different periods represents investor behavioral decisions with different investment term structure preferences. Last, a large number of empirical evidences show that MA achieves significant excess returns in market pricing forecasting. For example, Brock et al. (1992), Chen et al. (2021), and Fifield et al. (2008) present convincing evidences that MA has strong predictive power. Ma et al. (2021) believe that MA has predictive ability, and their research results show that trading volume moving averages have strong predictive ability in the Chinese market.

Recently, there has been increasing researches on the moving average strategy due to its effectiveness and predictable power. Some studies verify the effectiveness and predictive ability of MA. For example, Tang et al. (2021) find that compared with buy-and-hold strategies, fundamental timing strategies based on moving average (MA) timing signals can generate substantial performance gains. The annualized average return of fundamental timing strategies reaches approximately 37%, with a Sharpe ratio of nearly 1.30. Hung and Lai (2022) prove that portfolios composed of stocks with a high probability of informed trading (PIN) earn significantly higher returns under moving average strategy than a buy-and-hold strategy. Sun and Glabadanidis (2022) apply technical indicators to predict risk premium. Their in- and out-sample results suggest that technical indicators, especially moving average indicators, perform well at both monthly and weekly frequencies. Guo and Ryan (2021) discover that weighted moving averages are more effective in capturing the stock market trend compared to the time series momentum, which is computed as the past 12-month excess return. Arshanapalli et al. (2020) examine the efficacy of moving average technique in enhancing a buy-and-hold investment strategy during financial bubbles. And they find that the moving average significantly improves investment returns during three of the five financial bubbles since 1928, compared to a buy-and-hold strategy, while performing identically in the other two.

The development of behavioral finance theory provides a theoretical basis for technical traders. Hong and Stein (1999) propose a four-phase trading model, and they believe that traders’ overconfidence in their news in the first phase of trading leads to price moving away from the stock value, and short-term shocks lead to short-term momentum in the market. In the second phase, the arrival of some public information corrects the trading behaviors of most traders, making the price gradually return to value. In the third phase, when certain public information is released, overconfident traders are no longer attached to their news, and the price returns further. In phase four, investors sell their shares and the price returns to value. In addition, DHS model proposed by Daniel et al. (1998) and BSV model proposed by Barberis et al. (1998) also study investors’ behaviors and find that investors’ behaviors in the market are driven by their trading preferences. Yuksel (2015) studies the herding effect of institutions and finds that the herding effect based on price signals also exists in institutional investors. Different types of investors trade at different frequencies in the market due to information asymmetry or misunderstanding in receiving and processing personal information and public information. Ni et al. (2015) study investors’ trading behavior through the MA of closing prices, and they find that the overreaction and herd behavior in the stock market can be incorporated into the MA analysis. Ma et al. (2021) study asset pricing by constructing short- and long-term MA of trading volume, and find that noise traders’ trading volume short- and long-term MA had a significant negative predictive effect on the cross-sectional returns of the Chinese stock market.

Different excess returns obtained by different MA strategies under different term structures may due to the different reception and feedback of heterogeneous belief traders on different market information. The short-term MA obtains high excess returns, indicating that the market has sudden short-term positive news, which makes the market accumulate a mass of momentum in the short-term, while long-term excess returns indicate that the market is uncertain about the news will take time to digest. Ahmed et al. (2019) show that using a moving average crossover rule is more robust than the optimal strategy under parameter misspecification. Silva et al. (2018) prove that using a moving average strategy outperforms a buy-and-hold strategy.

The moving average can reflect investors’ behavioral decisions, and the profitability of the moving average with different term structures reflects its effectiveness in the capital market. Therefore, the traditional asset pricing model can be modified by technical indicators to compensate for what is ignored by considering only value-based fundamental factors. Although Liu et al. (2019) introduce a sentimental factor reflecting noise trading in the pricing model of the Chinese stock market, it is still worth further discussion whether this factor can fully reflect the diversification behaviors of traders under different term structures. Therefore, this paper applies tradable factors based on moving averages in different terms to study the behavioral decisions of traders with heterogeneous beliefs.

Data

Our sample data come from the Shanghai Stock Exchange and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange from January 2000 to June 2020, and data come from WIND Info, one of the largest data companies in China. It provides comprehensive transaction data and all types of financial data such as price ratios, fundamentals, shareholders, and other information.

Although the A-share market was established in 1990, there were only 13 listed companies in these two markets (Shenzhen and Shanghai). In 2001, the total number of listed companies in these two markets exceeded 1000. To ensure adequate samples, we require at least 50 stocks in each portfolio. Therefore, the selected data starts in 2000 to avoid having too few stocks in each portfolio. Furthermore, since the longest lag period for calculating the MA is 24 months, which means we have to skip 24 months, so we start with the actual data from 2002. Before the construction of the factors, we also exclude: (1) Companies that were listed for less than 6 months. (2) Those companies with less than 120 trading days in a year or less than 15 trading days in a month. We exclude new listings to avoid the volatility of new listings. It is well known that there is a strange phenomenon in China’s stock market, that is, newly listed companies always have several consecutive daily limits after listing. For example, 600369, after the resumption of trading on November 22, 2016, this stock has 42 consecutive daily limits. The price increased from 2.43 to 26.58, an increase of more than 10 times. This remarkable phenomenon occurs frequently in China. To eliminate this oddity, we exclude stocks with no trading record for six months.

Factors construction

This paper follows the four-factor pricing model proposed by Liu et al. (2019), which effectively explains sentimental anomaly returns in the Chinese market. We first form market factor (Mkt), size factor (SMB), value factor (VMG), and sentiment factor (PMO) according to their methods, but we do not exclude the bottom 30% cap stocks with the lowest market value. Among them, VMG is constructed according to the earnings-to-price ratio (EP), which is different from that of developed capital markets based on book-to-market ratio (BM). Their pricing factors are as follows:

The double moving average strategy appears earlier and is widely favored by investors with simple trading logic. The main ideas are as follows: Construct short-term and long-term MAs by smoothing the average price of the t-N period. Buy stocks when the short-term MA crosses the long-term MA up, and sell stocks when the short-term MA crosses the long-term MA down. The main purpose of the double moving average strategy is to eliminate noise trading by smoothing the price curve. David and Robert (1989), Levine and Pedersen (2016) formulate trading strategies by constructing moving averages, that is, taking short-term moving averages to cross up long-term moving averages as trading signals and obtaining significant excess returns in the market. We construct the trading strategy and pricing factor according to the double MA strategy. First, we form different lags of MA indices, in which the moving average is defined as follow:

\(MA_{jt,L}\) represents different lags of MA, L represents the lag time, and \(P_{jt}\) is the closing price of stock j at time t. According to the rules of the double MA strategy, two MAs, one short-term MA and the other long-term MA are generated. Traders will trade on the principle that the short-term MA crosses up the long-term MA, buying stocks and selling stocks otherwise. The main idea of the double MA strategy is that if the short-term MA crosses up the long-term MA, it means that a short-term momentum trend has begun. Investors buy stocks based on short-term momentum trend. This strategy is popular because of its simple logic and trading philosophy, as well as because it contains trend information indicating that prices may continue to rise or fall within a short period. When the short-term MA crosses up long-term MA, traders will subjectively identify it as a trading signal and buy stocks, resulting in a positive feedback effect and herd effect. Our breakout signals are differentiated according to different MA term structures. Specifically, the short-term breakout signals are 1-month cross 3-, 6-month, and 3-month cross 6-month. The mid-terms are 1-month cross 9-, 12-month, 3-month cross 9-, 12-month, 6-month cross 9-, 12-month, and 9-month cross 12-month. In the long period, the term structures of 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 cross the term structures of 18 and 24 to form a trading signal. The short- and long-lag MAs are formed by Eq. (1). Finally, short-lag \(MA_{jt,s{{{\mathrm{h}}}}ort}\) is divided by the long-lag \(MA_{jt,long}\) to obtain a trading signal \(\tilde S_{jt,L}\)

Based on this trading signal, we verify which MA signal has profitability with different term structures. The purpose of this study is to investigate trading strategies with different investment term structures that are effective in the market. Furthermore, it can reflect the decisions of traders with different term structures. When forming corresponding factors, it can capture the heterogeneous traders’ trading information. Therefore, it may enhance pricing power of asset pricing models. To explore the efficiency of moving average in asset pricing, we form the SCL(Short-term MA cross Long-term MA) factor by following methods: First, we divide all stocks into two groups, which are small-cap group(Small 50%) and big-cap group (Big 50%), according to the median point of outstanding shares of all stocks; Second, the trading signals (\(\tilde S_{jt,L}\)) constructed by short- and long-term MAs are divided into 30%, 40%, and 30% from high to low. Third, the small-cap and big-cap companies intersect with the trading signals of 30%, 40%, and 30% to form 6 portfolios; Fourth, according to the traditional factor construction method, the intersection of lowest 30% \(\tilde S_{jt,L}\) with small-cap and lowest 30% \(\tilde S_{jt,L}\) with big-cap should be purchased according to the value weight, and the intersection of highest 30% \(\tilde S_{jt,L}\) with small-cap value and highest 30% \(\tilde S_{jt,L}\) with big-cap should be sold according to the value weight at month of t. The total investments of SCL factors are zero-arbitrage portfolios, and the returns of portfolios are obtained at month of t + 1. Further, we use SCL (m, n) to indicate that this combination is the m-period short MA cross the n-period long MA. We use low minus high because we consider the reversal effect in the Chinese market. Tian et al. (2014) find that there is a strong reversal effect in the Chinese market due to the overconfidence of the Chinese retail traders. If the value of \(\tilde S_{jt,L}\) is too high, it means the short-lag MA far exceeds the long-lag MA. In the traders’ minds, they believe that momentum will wear off, so they sell stocks that cause a significant drop in stock prices. Therefore, the lower \(\tilde S_{jt,L}\), the greater the momentum going forward. Thus, we use low \(\tilde S_{jt,L}\) minus high \(\tilde S_{jt,L}\).

Empirical analysis

Profits of moving average factors

According to the above trading principle of double MA, we construct the MA factors. The short-lag MA is divided into six term structures of 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 18, and the long-lag MA is divided into six term structures of 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24. We cross them to form 21 MA combinations of factors, which contains short-, medium-, and long-term combinations. Based on the above methods, we construct factors with different term structures, and Table 1 shows their weighted value return results.

In Table 1, the factor returns formed by 1 lag short-term MA and the other lags of long-term MA are significantly positive. The monthly average return of the portfolio composed of SCL (1, 3) is 1.11%, and its T value is 4.12 at the highest. In addition, SCL (1, 6) and SCL (1, 9) also achieve portfolio returns over 0.8%. This indicates that the average with a term of 1-month running through different term structures can be used as trading information for noise traders in the Chinese market. It is meaningful to study pricing by constructing related transaction factors. At the same time, the average returns for other term structures are not significant at the level of 5%. This shows that except for the short-term trend signals of 1-month, other monthly trend signals do not play a strong role in the Chinese market.

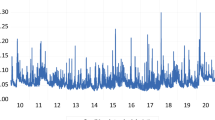

To better understand factor returns in different terms, we also plot a figure that includes the short-term of 1 to 23 and the long-term of 2 to 24. With the same construction we mentioned above, we calculate short-term MA and long-term MA, and divide short-term MAs by long-term MAs to form the SCL factors, respectively. Factor average returns and T values are presented below:

As can be seen in Fig. 1, the left figure is factor returns of the short-term of 1 to 23 and the long-term of 2 to 24. The X-axis is the short-term MA from 1 to 23, and the Y-axis is the long-term MA from 2 to 24. The Z-axis is the average return of each factor. In the right figure, the X- and Y-axis are the same as in the left figure, and the Z-axis is the T value of each factor return. From Fig. 1, we can conclude that a short-term MA of 1 has the highest factor returns. Therefore, we apply the short-term MA of 1 cross various long-term MA of quarterly, semiannual, and annual critical points.

This figure shows the factor returns of various short-term MAs cross Long-term MAs. The short-term MAs are 1 to 23, and the long-term MAs are 2 to 24. The left side is the factors’ average returns, and the right side is the t values of factors’ average returns. Samples are from Jan 2002 to Jun 2020. The average returns are presented as percentages.

The bottom 30% stocks

As mentioned above, the Chinese market is dominated by retail traders, who prefer to speculate on small-cap stocks. The reason is that these stocks are relatively cheap and tend to be popular with retail investors. In addition, small-cap stocks are usually more volatile, and speculators in the Chinese market see more opportunities for large volatility, because many of these investors are risk-seekers. Thus, to make high profits, these investors will pay more attention to small-cap stocks. Furthermore, Han et al. (2016) point out that the trend of small-cap stocks and penny stocks have seen stronger trends. However, the factors constructed by Liu et al. (2019) exclude the bottom 30% of stocks because of the “shell effect”. Due to individual investors take a large proportion in the Chinese market, we believe that the small-cap stocks are important. Besides, the trading volume of small-cap stocks in China accounts for a considerable proportion of the whole market trading volume. If we exclude it, it may cause some deviations in pricing. Thus, we apply several filters to explore whether small-cap stocks matter in MA factors.

Figure 2 shows the proportion of the 30% cap stocks with the smallest market value in the total trading volume in the Chinese stock market. It can be seen that from 2002 to 2013, the trading volume of the bottom 30% cap stocks with the smallest market value accounted for a small proportion of the entire market, and the average trading volume accounted for less than 15% of the total trading volume. Nevertheless, after 2013, the proportion increased significantly, and after 2019, it reached nearly 30%. The reason for eliminating the 30% cap stocks with the smallest market capitalization is that these companies have a “shell effect”, and their stock price fluctuations are seriously affected by mergers and reorganizations. When excluding these bottom stocks, Liu et al. (2019) focus on the fundamental and sentimental factors that may affect asset prices. However, this paper focuses on whether the MA factors can effectively complement the existing pricing model. We believe that the bottom 30% cap stocks are a great help to our research. There is evidence that trend-following strategies prefer bottom stocks because of their lower price and greater volatility, making them more popular among investors (Han et al., 2016). Chinese investors prefer to buy these stocks based on their habits, as most retail investors are risk seekers. They believe that the greater the risk, the greater the profit. To better explain this, we create some filters to determine whether this still holds true under different term structures of double MA strategies in the Chinese market.

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics for the different types of filters in the double MA strategies factors. No filter refers to unfiltered raw data, the price filter excludes the closing price below 5 CNY (The Chinese Yuan), and the size filter excludes the bottom 30% cap stocks. From Table 2, we can observe that the unfiltered portfolios have higher average returns, ranging from 0.901 to 1.173. These portfolios also have the highest T values, indicating that the average returns of these portfolios are more significant than those filtered portfolios. Moreover, unfiltered portfolio returns are less volatile than those filtered by price and size. For example, the portfolio of MA (1, 3) has a standard deviation of 4.23%, which is lower than the price filter of 5.72% and the size filter of 4.28%. Except for the skewness of price filter portfolios, the skewness and kurtosis of the other filter portfolios are relatively low. The Sharpe ratio, a key measure of portfolio performance, is described as follows: \({{{\mathrm{R}}}}_{{{\mathrm{i}}}} - {{{\mathrm{R}}}}_{{{\mathrm{f}}}}/\sigma\). In this equation, the denominator is the standard deviation of the return of portfolio i, and the numerator is the difference between the portfolio returns on portfolio i and the risk-free rate. The Sharpe ratio indicates that the larger the ratio, the better the portfolio performance. Evidently, the unfiltered portfolios have a sharper edge over the price-filtered and the size-filtered portfolios. The portfolios, which include the bottom 30% cap stocks, have higher returns under the double MA strategy. If the bottom stocks are excluded, neither the average portfolio return nor the Sharpe ratio is as high as that of the full market portfolio. Therefore, it can be found that the bottom of stock trend is stronger. We also conduct a test in the short-term of 3, 6, 9, 12, and 18 crossed the long-term of 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24, respectively, and we obtain the same result. From the results above, stocks with bottom 30% cap have stronger trends that make these stocks are predictive while using moving average. Therefore, we believe the stocks with bottom 30% cap should be reserved in this study.

Market anomalies explanatory ability of MA factor

Spanning regression

In this paper, SCL (Short-term MA cross Long-term MA) factors are added based on the four factors, and there is a strong correlation between the SCL factors with different term structures. If all of them are included in the pricing model, the problem of redundant factors will arise. In order to eliminate redundant factors, we use backward stepwise regression to eliminate the redundant factors from the regression and retain the factors with the best explanatory ability to the market anomalies.

Table 3 shows the results for spanning regression of SCL (1, 3) and SCL (1, 12). We find that even with the introduction of MA factors, the intercept term Alpha of the original factors of Liu et al. (2019) is still significant. It shows that the addition of these two new SCL factors not only fails to absorb these factors for asset prices, but also complements the original value, size, and sentiment factors. On the one hand, these two factors show that the behavioral decisions of investors have broad investment term structures, both short-, medium-, and long-term. On the other hand, the PMO factor based on trading volume does not fully reflect the noise trading behavior in the market, and the MA factor plays a role in helping us understand the formation of asset prices in the market.

Descriptive statistics

Through the spanning regression, we find that SCL (1, 3) and SCL (1, 12) are supplements to Liu et al. (2019)’s four-factor model. Therefore, we add these two trend factors into the four-factor model to form an augmented six-factor model. We use this augmented six-factor model to explore pricing power in the Chinese market. Table 4 provides descriptive statistics for six factors with a sample period from January 2002 to June 2020.

Table 4 shows that the average returns of these factors are 0.675%, 0.916%, 0.717%, 0.866%, 1.173%, and 0.920%, respectively, but the market factor(Mkt) is not significant, with a T value of only 1.29. The other factors’ T values are 2.94, 2.72, 4.15, 4.129, and 3.026, respectively, significant at the 1% level. The standard deviation of Mkt is about 7.8%, which is twice than that of VMG and PMO (3.9% and 3.1%), and the standard deviation of SMB is 4.6%. This suggests that the return of the market factor is more volatile than the returns of the other three portfolios. Since the monthly average excess returns of SMB, VMG, PMO, SCL (1, 3), and SCL (1, 12) are considerable and the T value is significant, it indicates that the size, fundamentals, sentiment, and MA indicators are crucial to the pricing of the Chinese stock markets during the sample period. Among the four factors of Liu et al. (2019), the Sharpe ratio of PMO is the highest, indicating that the sentimental factor can obtain higher returns and take lower risks in the Chinese market, while the Sharpe ratio of the market factor is the lowest due to the large fluctuation. Except for VMG, SCL (1, 3), and SCL (1, 12), the tails of the remaining factors were skewed to the left, and the six factors all show peak and thick tail in statistics. Panel B shows the Pearson correlation coefficients for six factors. VMG and PMO are negatively correlated with Mkt. Most of the correlation coefficients are less than 0.5 except for SMB and VMG (−0.57), as well as SCL (1, 3) and SCL (1, 12) (0.756), which indicates that the correlations among these factors are relatively weak.

Factor effectiveness

To examine the validity of the factors, we use Barillas and Shanken (2016) maximum square Sharpe ratio indicator. The original purpose of this ratio is to judge the quality of factors according to the intercept of the model’s LHS (Left Hand Side) time series regression. The maximum square Sharpe ratio of the intercept term is \(Sh^2\left( {\alpha _i} \right) = \alpha _i^\prime \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_i^{ - 1} {\alpha _i}\), where \(\alpha _i\) is the intercept vector of regression, and \(\sum _i^{ - 1}\) is the inverse of the residual variance-covariance matrix, that is, the smaller the ratio, the more effective the chosen pricing factor. Regardless of the measurement error, Barillas and Shanken (2016) believe that minimizing \(Sh^2\left( {\alpha _i} \right)\) is achieved by maximizing the maximum square Sharpe ratio \(Sh^2\left( {f_i} \right)\) of the selected pricing factor \(f_i\). This means that to compare the effectiveness of two separate factors of \(f_i\) and \(f_j\), we only need to compare the value of \(Sh^2\left( {f_i} \right)\) and \(Sh^2( {f_j})\). In the empirical analysis, Fama and French (2018) apply this strategy, and perform factor selection in their five-factor model.

Our pricing model is based on the four-factor model proposed by Liu et al. (2019), and we introduce the augmented six-factor model of the four-factor model plus SCL (1, 3) and SCL (1, 12). Therefore, we compare the four-factors of Liu et al. (2019) with the maximum square Sharp ratio of our six-factor model. It should be noted that Liu et al. (2019) are nested in our six factors, and the effectiveness of six factors has been shown by Spanning regression. In addition, we consider pricing the factors SCL (1, 3) and SCL (1,12) with the four factors of Liu et al. (2019), and conduct the GRS test, where the P-value is less than 0.01, indicating that the four-factors of Liu et al. (2019) cannot fully explain SCL (1,3) and SCL (1,12). The result indicates that the introduction of these two SCL factors into the pricing model will significantly improve the maximum square Sharpe ratio and the pricing power of the four-factor model proposed by Liu et al. (2019). Our SCL factors have a marginal contribution to the four-factor model.

To further investigate the validity of the factors SCL (1, 3) and SCL (1, 12), the Bootstrap test of Fama and French (2018) is applied to illustrate. The idea of the method is to investigate the maximum square Sharpe ratio of four factors and our six factors in-sample and out-of-sample through Bootstrap simulated sampling. If a significant improvement in the six-factor’s Sharpe ratio compared with the four-factor’s Sharpe ratio, it indicates the effectiveness of SCL (1, 3) and SCL (1, 12) as pricing factors. The specific steps of Bootstrap are as follows:

First, since our data includes a total of 222 periods, the factor portfolio returns are grouped every two periods, namely (1, 2), (3, 4) … (221, 222), the numbers in parentheses represent the number of periods, so a total of 111 sets of data can be obtained.

Second, a set of data is drawn from 111 sets of data, and then a random data is drawn from this set of data and put into the in-sample data set, while the other data is allocated to the out-of-sample data set. 111 in-sample and 111 out-of-sample data are extracted after 111 times of extraction.

Third, use the data from 111 samples to obtain the maximum square Sharpe ratio and the weight of each factor.

Fourth, the weight obtained from the in-sample data is applied to the out-of-sample data set to generate the combination, and the Sharpe ratio of the out-of-sample data of the combination is calculated.

Fifth, repeat the above steps 9999 times.

Sixth, calculate the average and median of the above 10,000 simulated results and compare the Sharpe ratios for different factors.

Table 5 shows the Sharpe ratios for different factors, three of which include Mkt, SMB, and VMG, and four of which include Mkt, SMB, VMG, and PMO. The six factors are SCL (1, 3) and SCL (1, 12) added to the four factors. The AVG and Median are the average and median values of the maximum square Sharpe ratio of 10,000 times bootstrap. From the results in Table 5, the true value of the maximum square Sharpe ratio of three, four, and six factors are 0.190, 0.264, and 0.323, respectively. The maximum square Sharpe ratio of six factors is about 0.06 higher than that of four factors, and about 0.13 higher than that of three factors. In addition, our results for six factors of the in-sample data also show that the average and median of the maximum square Sharpe ratio are the highest, followed by four factors and three factors. However, since three factors are nested in four factors, and four factors are nested in our six factors, this result is predictable. Therefore, only out-of-sample results can illustrate the effectiveness of factor models. In the result of out-of-sample, the average, and median of the six factors’ Sharpe ratio are still the highest, with the average values 0.095 and 0.040 higher than that of the three factors and four factors, and the T values of the differences are significant at the 5% level. This indicates that adding two SCL factors significantly improves the pricing power of the four-factor pricing model, and the SCL factors have a significant marginal contribution to the explanatory power of asset prices in China.

Explanatory power of factor models

This part further explains the effectiveness of the factor models through the test of market anomalies. Liu et al. (2019) find the abnormal returns of size, value, profitability, volatility, reversal, turnover, investment, accrual, and illiquidity in the Chinese market. To maintain continuity with Liu et al. (2019) and cover moving average abnormal returns, we select the following 18 anomalies: E/P, B/M, C/P, ROE, VOL, 1-mo Max, Reversal, 1Mo Breakthrough, MOM, Turnover 240, Turnover 20, Turnover 1/12, SCL(1, 3), SCL(1, 6), SCL(1, 9), SCL(1, 12), SCL(1, 18), and SCL(1, 24) (e.g., Wang and Xu, 2004; Eun and Huang, 2007; Chen et al., 2010; Cheung et al., 2015; Cakici et al., 2017; Hsu et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2017; Li et al., 2007; Carpenter et al., 2021; Zhang and Liu, 2006; Li and Wu, 2003; Fama and French, 2015; Carhart, 1997). The explanations of anomalies are presented in Appendix.

We follow Liu et al. (2019)’s method to form the 18 abnormal returns. Specifically, we sort each anomaly from low to high by its value, and divide each anomaly into 10 equal parts to form portfolio P1, P2…, and P10 at month of t. Each portfolio’s weighted average return is calculated at month of t + 1, respectively. Then we calculate the abnormal returns of 18 groups of P10-P1, which is called market anomalies. In order to compare the pricing power of three-factor, four-factor, and our six-factor models, this paper employs the GRS test developed by Gibbons et al. (1989) to each model respectively. The null hypothesis of GRS is \(\alpha _0 = \alpha _1 = \ldots \alpha _{{{\mathrm{n}}}} = 0\). If the null hypothesis is rejected, alphas cannot be jointly equal to zero, indicating that abnormal returns cannot be explained by the factor model. Therefore, the smaller the value of GRS statistics, the greater the probability of accepting the null hypothesis and the better the model performs. We also add the FF5 factor model to compare whether it captures the 18 anomalies in the Chinese market well. Based on the results of GRS test, such as GRS statistic, alpha, and the Sharpe ratio, we can judge whether the six-factor model can effectively improve the pricing power to explain market anomalies.

Table 6 is given based on the test of the different factor models. The GRS statistics, P-values of GRS, absolute mean values of alpha, absolute mean values of t statistic, and maximum square Sharpe ratios \(Sh^2\left( f \right)\) are presented. The results not only include the full-sample, but also two sub-samples (i.e., from January 2002 to March 2011 and from April 2011 to June 2020). The sub-samples analysis is to examine the robustness of the whole sample.

For the full samples, only the six-factor model was not significant at the test level of 5% in the GRS test, indicating that the abnormal returns can be explained by the six-factor model. The P-values for both the three- and four-factor models are less than 1%, and the GRS value of the six-factor model are about 35% and 20% lower than those of the three- and four-factor models. At the same time, the Avg.|α| of six-factor model is about 50% lower than the three- and the four-factor models. Avg.|t| of Six-factor model is only 1.017, which is far lower than the three- and four-factor models of 1.370 and 1.408. In addition, the three factors, four factors, and six factors’ \(Sh^2\left( f \right)\) show an increasing trend, and the six factors is 0.323, which has the largest value and the strongest explanatory ability. It can be seen that all indicators imply consistent results, that is, the six-factor model provides a significant improvement over the three- and four-factor models. Moreover, our study includes the bottom 30% market capitalization of listed companies. Thus, our six-factor pricing model can provide sufficient explanatory power for asset prices. The FF5 performs worst in capturing the 18 anomalies.

For the sub-samples, all indicators show that the six-factor model is superior to the three- and four-factor models, especially the GRS statistics for the two sub-samples. The six-factor model also passes the 5% significance level test. However, neither the three- nor four-factor model passes the GRS test in sub-sample 2. At this time, the p-value of the six-factor model reaches 0.126, and it cannot reject the null: \(\alpha _0 = \alpha _1 = \ldots \alpha _{{{\mathrm{n}}}} = 0\). The sub-sample result indicates six-factor model can fully explain the 18 abnormal returns in the Chinese market. Although the FF5 factor model performs best in sub-sample 1, it performs worst in full-sample and sub-sample 2. Therefore, we will not consider it in the below analysis, and we will focus on the pricing power of the three- factor, four-factor models proposed by Liu et al. (2019), and our six-factor model.

To sum up, it is necessary to include SCL (1, 3) and SCL (1, 12) that reflect the behaviors of investors with different term structures in asset pricing models in the Chinese market.

State dependence of factor models

Since the economic state and market state have a significant impact on asset prices, it is important to analyze the state dependence on asset pricing models (Lakonishok and Vishny, 1994). GDP is the main indicator to measure a country’s development and is closely related to the capital market. Moreover, the market index itself reflects the changes in bull and bear markets, and different asset prices often perform differently when GDP and market conditions are different. Based on this, this paper ranks their values from high to low according to the growth rate of GDP and Shanghai Composite Index, and divides them into optimal 15% (best 15%), general 70% (middle 70%), and pessimistic15% (worst 15%) to investigate whether there is a possible state dependence in the factor model.

Table 7 shows the performance of pricing models in different GDP and market states. It can be seen that different factor models have a certain state-dependence.

First of all, the six-factor model is significantly better than the three- and four-factor models under different GDP conditions. In the extreme case of best 15% and worst 15%, although the six-factor model performs the best among all indicators, the GRS results show that at the 5% significant level, the three- and four-factor models can also pass the test and explain asset prices well. In the general situation (Middle 70%), the six-factor not only performed best among all indicators, but also can not reject the null hypothesis at the significance level of 5%. Meanwhile, the three- and four-factor models of GRS statistics are significant, indicating that only six-factor model can fully explain the market anomaly in the state of the middle 70%. At the state of the best 15%, the six-factor model’s statistic of GRS is still the lowest among all pricing models, which indicates that our six-factor model outperforms the other two models.

Secondly, for the Shanghai Composite Index, all indicators show that the six-factor model performs best in the best 15% and general (Middle 70%) states. However, it should be noted that the GRS test shows that in the general state (Middle 70%), the P-values of six-, three-, and four-factor models are close to 0, which means that no factor models can fully explain the market anomalies in this state. In the 15% worst state, although the GRS test suggests that the three-factor model performed best, the P-value of the six-factor model also reach 0.102, indicating that even at the significance level of 1%, the six-factor model can fully explain the market anomalies. At the same time, under the conditions of Worst 15%, the Avg. |α| of six-factor model is 0.757, far less than the three factor model of 0.943.

It can be seen that although the factor models are state-dependence, on the whole, the six-factor model still performs best.

Further research on trend state dependence

In the Chinese market, the Shanghai Composite Index is an important indicator to measure whether the stock market is bearish or bullish. A large proportion of stocks in the Chinese market have a positive relationship with the market, that is, individual stocks in the A-share market maintain the same trend as the Shanghai Composite Index. Individual stocks and the Shanghai Composite Index rise and fall simultaneously. Thus, to explore the advantage of the trend factor, that is, the double MA factor in this paper, we divide SCI 300 according to the trend. As can be seen from Fig. 3 below, there is a downward trend from 2001 to 2005, 2010 to 2014, and 2015 to 2020. However, from 2005 to 2008 and the first half of 2014 to 2015, the trend increased rapidly. Overall, the recession period accounted for the larger proportion of SCI. To investigate whether trend factors are more effective in different market trends, we still choose the GRS test to explore the effectiveness of our six-factor model. In this paper, we present GRS results with the most obvious trend and long duration.

In the different trend states, each factor model outperforms the entire period. Statistically, this may be a clear trend that the accuracy of the parameters estimation is improved. Thus, the α is less significant. From an economic perspective, trends are often accompanied by macro-level, corporate-level, sentiment-level, and market-level. Therefore, the factor models have different explanatory powers for the market anomalies during different trend periods. This paper does not focus on this, but mainly focuses on whether the trend state dependent factor can better explain the market in the trend period.

According to the GRS test results of these pricing models on 18 anomalies, it can be seen from Table 8 that the explanatory power improves significantly in all different trend periods. For example, from 2002 to 2005, the GRS statistic of six-factor model is 0.531, which is about half of the three-factor model and about 69% of the four-factor model. The same results are also shown in other trend periods, indicating that our six-factor model can capture trends effectively. In addition, the marginal contribution of the six-factor model increases more significantly than that of the three- and four-factor models. From the result of \(Sh^2\left( f \right)\), our six-factor model increases from 0.747 and 0.900 of three- and four-factor models to 1.284 from 2002 to 2005, respectively. Due to short selling constraints, the of six-factor model does not increase significantly in the downside periods, which ranges from 0.351 in 2010 to 0.508 in 2014. This may be due to market factors, rather than fundamentals explaining pricing in trend states. The result strongly explains that the trend factor is more effective in a trend state, with most stocks following the same trend as the market. Therefore, when the overall market is in a clear trend, the trend state-dependent factor performs better and has stronger explanatory power toward the market.

Conclusions

Traders, including retail traders and fund managers, often use technical indicators to reflect the trend of price changes. Several studies, such as those by Tang et al. (2021), Ma et al. (2021), and Ni et al. (2015), have highlighted the efficacy of the MA strategy as a profitable approach in the Chinese market. In this study, we examine the impact of double MA on asset prices. By constructing MA strategies with various term structures, our findings are consistent with the above researchers, and we find that factors formed by short-term MA of 1 month and long-term MA of 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months can obtain significant excess returns in China. Among them, the factor excess return of 1 month cross 3 months is the highest, and the average returns decrease as the term-structures of the long-term moving average increase. Based on these findings, unlike the above researchers who focus on MA strategy profit, we are concerned about whether different term structures of MAs can be pricing factors for enhancing the pricing power in the Chinese market. We extend the most competitive four-factor pricing model of Liu et al. (2019) in the Chinese market. The stepwise regression results show that SCL (1,3) and SCL (1,12) significantly complement the size, value, and sentiment factors proposed by Liu et al. (2019). At the same time, according to Barillas and Shanken (2016) and Fama and French (2018), our six-factor model significantly improves the maximum Sharpe squared ratio compared with the four-factor model. Moreover, in the GRS test of 18 anomalies, compared to the three- and four-factor models proposed by Liu et al. (2019), only the six-factor model is not significant at the level of 5%. Avg. |α| and Avg. |t| of the six-factor model also improve significantly, that is, Avg. |α| reduce by about 50% compared with the three- and four-factor models. Although the SCL (1, 3), SCL (1, 12), and sentimental factors of Liu et al. (2019) all describe the impact of sentiment on asset prices, the sentimental factors of Liu et al. (2019) cannot fully reflect the behaviors of traders. The SCL (1,3) and SCL (1,12) factors complement the sentimental factors of Liu et al. (2019) that failed to fully capture the behaviors of traders. SCL (1,3) and SCL (1,12) factors reflect the price trend signals in different periods, as well as the behavioral characteristics of noise traders based on information in different terms and the diversity of their trading behaviors.

In addition, we divide different states according to the growth rate of GDP and the trends of the Shanghai Composite Index to investigate the performance of the factor models. Although the factor models are state dependent, the six-factor model with SCL (1, 3) and SCL (1, 12) still outperforms the three- and four-factor models.

The Chinese market is predominated by retail investors, which makes the trading behavior of noise traders play an important role in the market. What they do matters for asset prices. On the one hand, the effectiveness of MA factors with different term structures reflects the important role of price trends in noise traders’ trading. On the other hand, it reflects the diversity of decision-making among different investors. In conclusion, the MA factors serve as essential enhancements to existing asset pricing models.

Data availability

The data are not publicly available due to commercial confidentiality that can compromise the benefits of the Wind info company. Researchers can obtain data from WIND Info.

Notes

According to the Shanghai Stock Exchange Statistical Yearbook Vol.2020, the market value of natural person shareholders’ shareholding is 6,185.6 billion Yuan, while that of institutional investors is 4728.3 billion Yuan, which is 1.3 times that of professional institutions. At the same time, the number of accounts opened by natural shareholders was 385.6 million, and the number of accounts opened by professional institutions was 552,800, accounting for 99.8% of the total number of accounts opened by retail investors.

References

Ahmed BHA, Loeper G, Abergel F (2019) Challenging the robustness of optimal portfolio investment with moving average-based strategies. Quant Financ 19(1):123–135

Antoniou C, Doukas JA, Subrahmanyam A (2013) Cognitive dissonance, sentiment, and momentum. J Financ Quant Anal 48(1):245–275

Arshanapalli BG, Lutey M, William NB, Micah P (2020) The profitability of technical analysis during financial bubbles. J Portf Manag 47(1):168–175

Barberis N, Shleifer A, Vishny R (1998) A model of investor sentiment. J Financ Econ 49(3):307–343

Barillas F, Shanken J (2016) Which alpha? Rev Financ Stud 30:1316–1338

Brock W, Lakonishok J, Lebaron B (1992) Simple technical trading rules and the stochastic properties of stock returns. J Financ 47:1731–1764

Cakici N, Chan K, Topyan K (2017) Cross-sectional stock return predictability in China. Eur J Financ 23(7-9):581–605

Carpenter JN, Lu F, Whitelaw RF (2021) The real value of China’s stock market. J Financ Econ 139(3):679–696

Carhart MM (1997) On persistence in mutual fund performance. J Financ 52(1):57–82

Chen KH, Su XQ, Lin LF, Shi YC (2021) Profitability of moving-average technical analysis over the firm life cycle: evidence from Taiwan. Pac Basin Financ J 69:101633

Chen X, Kim KA, Yao T, Yu T (2010) On the predictability of Chinese stock returns. Pac Basin Financ J 18(4):403–425

Cheung C, Hoguet G, Ng S (2015) Value, size, momentum, dividend yield, and volatility in China’s A-share market. J Portf Manag 41(5):57–70

Chopra N, Josef L, Jay RR (1992) Performance measurement methodology and the question of whether stocks overreact. J Financ Econ 31:235–268

Corsi F (2009) A simple long memory model of realized volatility. J Financ Econ 7(2):174–196

Daniel K, Hirshleifer D, Subrahmanyam A (1998) Investor psychology and security market under- and over- reactions. J Financ 53(6):1839–1886

David PB, Robert HJ (1989) On technical analysis. Rev Financ Stud 2(4):527–551

De Bondt WFM, Thaler RH (1985) Does the stock market overreact? J Financ 40:793–805

Eun CS, Huang W (2007) Asset pricing in China’s domestic stock markets: is there a logic? Pac Basin Financ J 15(5):452–480

Fama EF, French KR (2015) A five-factor asset pricing model. J Financ Econ 116(1):1–22

Fama EF, French KR (1986) Permanent and temporary components of stock prices. J Polit Econ 98:246–274

Fama EF, French KR (2018) Choosing factors. J Financ Econ 128:234–252

French KR, Richard R (1986) Stock return variances: the arrival of information and the reaction of traders. J Financ Econ 17:5–26

Fifield SGM, Power DM, Knipe DGS (2008) The performance of moving average rules in emerging stock markets. Appl Financ Econ 18:1515–1532

Gibbons MR, Ross SA, Shanken J (1989) A test of the efficiency of a given portfolio. Econometrica 57:1121–1152

Guo B, Zhang W, Zhang Y, Zhang H (2017) The five-factor asset pricing model tests for the Chinese stock market. Pac Basin Financ J 43:84–106

Guo X, Ryan S (2021) Portfolio rebalancing based on time series momentum and downside risk. IMA J Manag Math 34(2):355–381

Han Y, Zhou GF, Zhu Y (2016) A trend factor: any economic gains from using information over investment horizons? J Financ Econ 122:352–375

Han YF, Yang K, Zhou GF (2013) A new anomaly: the cross-sectional profitability of technical analysis. J Financ Quant Anal 48:1433–1461

Hong H, Stein JC (1999) A unified theory of underreaction, momentum trading, and overreaction in asset markets. J Financ 54:2143–2184

Hsu J, Viswanathan V, Wang M, Wool P (2018) Anomalies in Chinese a-shares. J Portf Manag 44(7):108–123

Hung C, Lai H (2022) Information asymmetry and the profitability of technical analysis. J Bank Financ 134:106347

Jegadeesh N, Titman S (1993) Returns to buying winners and selling losers: implications for stock market efficiency. J Financ 48(1):65–91

Lakonishok J, Vishny SRW (1994) Contrarian investment, extrapolation, and risk. J Financ 49(5):1541–1578

Lehmann BN (1990) Fads, martingales, and market efficiency. Quart J Econ 105:1–28

Levine A, Pedersen LH (2016) Which trend is your friend? Financ Anal J 72(3):1–16

Li Y, Wu S(2003) An empirical analysis of the liquidity premium in China (Translated from Mandarin) Manag Rev 11:34–42

Li Z, Yao Z, Pu J (2007) What are the economics of ROE in China’s stock market (Translated from Mandarin). Chin Account Rev 3:305–314

Li ZB, Yang GY, Feng YC, Jing L (2017) Empirical test of Fama-French five-factor model in Chinese stock market (Translated from Mandarin). Financ Res 6:191–206

Lin Q (2018) Technical analysis and stock return predictability: an aligned approach. J Financ Mark 38:103–123

Liu J, Stambaugh RF, Yu Y (2019) Size and value in China. J Financ Econ 134(1):48–69

Ma Y, Yang B, Su Y (2021) Stock return predictability: evidence from moving averages of trading volume. Pac Basin Financ J 65:0927–538X. P101494

Müller U, Dacorogna M, Dave D (1997) Volatilities of different time resolutions-analyzing the dynamics of market components. J Emp Financ 4(2):213–239

Ni Y, Liao YC, Huang P (2015) MA trading rules, herding behaviors, and stock market overreaction. Int Rev Econ Financ 39:253–265

Rubi MA, Chowdhury S, Rahman AAA, Meero A, Zayed NM, Islam KA (2022) Fitting multi-layer feed forward neural network and autoregressive integrated moving average for Dhaka Stock Exchange price predicting. Emerg Sci J 6(5):1046–1061

Silva DS, Matheus J, Franco R, Danilo G, Pena MG (2018) Examination of the profitability of technical analysis based on moving average strategies in BRICS. Financ Innov 4(1):1–18

Sun M, Glabadanidis P (2022) Can technical indicators predict the Chinese equity risk premium? Int Rev Financ 22(1):114–142

Tang G, Jiang F, Qi X, Huang N (2021) It takes two to tango: fundamental timing in stock market. Int J Financ Econ 26(4):5259–5277

Tian LH, Wang Y, Tan DK (2014) Reversal effect and asset pricing in China: how do historical return influence stock performance (Translated from Mandarin). Financ Res 10:177–191

Wang F, Xu Y (2004) What determines Chinese stock returns? Financ Anal J 60(6):65–77

Wang J (1993) A model of intertemporal asset prices under asymmetric information. Rev Econ Stud 60:249–282

Xiang C, Lu J (2018) Validation of investor sentiment index based on technical analysis indicators (Translated from Mandarin). J Manag Sci 31(1):129–148

Yuksel HZ (2015) Does investment horizon matter? Disentangling the effect of institutional herding on stock prices. Financ Rev 50:637–669

Zhang Z, Liu L (2006) The turnover premium: is it a liquidity premium or a bubble? (Translated from Mandarin). Quart Econ J 3(5):871–892

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All people who have made substantial contributions to the work reported in below: Y-ZC: conceptualization, software, methodology, formal analysis, and writing-original draft; YF: methodology, writing-review & editing; X-YL: review, editing & polishing; JW: review & editing;

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Fang, Y., Li, X. et al. A factor pricing model based on double moving average strategy. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 830 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02362-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02362-x