Abstract

The contemporary media narratives frequently exhibit significant contradictions due to the influence of diverse interests. In this context, the framing of information assumes critical importance in shaping consumer opinions, necessitating a comprehensive examination of its management. This article investigates the portrayal of crises in the agri-food sector within the mass media when not anchored in objective and verifiable facts, thereby exerting a consequential impact on the sector’s reputation and public image. Specifically, a detailed analysis is conducted on the greenhouse horticulture sector in southeast Spain, recognized as the primary European supplier. Examination of these news items uncovers a discernible bias in the disseminated information, resulting in an information asymmetry between farmers and consumers. As a remedy for the affected sector, the current study advocates the implementation of a proactive crisis detection and management model grounded in the development and dissemination of verifiable information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When addressing crises, the media’s ability to recognize and utilize suitable news sources is crucial for delivering effective and trustworthy news coverage. Consequently, it is imperative to identify the factors influencing this ability and to discover methods for improving and optimizing these source choices. In general, the media is presumed to bear the responsibility of determining which information will be disseminated as news and which will remain undisclosed to the public.

Within this framework, the present study analyzes how crises in the agri-food sector are reflected by general media outlets in Europe and how they can affect its image and reputation. This article contends that the management of information by the media can be an influential source of crises, particularly in instances related to health standards and sustainability. To analyze the scope of information published in the media, this article compares news items with the opinions of affected sectors while also examining pertinent academic studies.

More specifically, this study centers on Spanish greenhouse horticulture production, a model barely 60 years old, exemplifying endogenous economic development from severe conditions of poverty, whose maximum expression is in the province of Almeria (Galdeano-Gómez et al., 2017). European mass media and academia only began to focus on this area when exportation commenced in the early nineties (Tout (1990)). Characteristics such as the harsh arid climate, the world’s highest concentration of plastic-covered greenhouses, and its geographical location along illegal migration routes further heightened the region’s appeal. However, the sector’s growth was marred by issues such as the widespread use of pesticides and local environmental degradation (Izquierdo et al., 2004).

A pivotal turning point occurred in 2007 when major chain supermarkets, primarily from Germany, declined to purchase from Almeria due to chemical presence in vegetables. Consequently, the sector swiftly responded, making southeast Spain the world’s largest user of Integrated Pest Management within a year, completely abandoning uncontrolled chemical use (Van der Blom et al., 2010). Despite this, the sector has been stigmatized since then. In 2011, the Hamburg government falsely attributed responsibility for E-coli cases to Spanish vegetables, resulting in substantial economic repercussions (Pérez-Mesa et al., 2019) and widespread negative media impact (Van Asselt et al., 2017). Subsequently, the horticultural sector faced unjustified campaigns by the European press. In the ensuing years, mass media and academia directed attention toward environmental issues and social inequality. Overall, this situation has influenced consumer opinions, with beliefs that greenhouse products from southeast Spain are of inferior quality and generate negative externalities (Sirieix et al., 2008; Serrano-Arcos et al., 2020).

Currently, Spain exports greenhouse vegetables to the European Union (EU) valued at €6.2 billion (ICEX, 2021), with nearly 300 million consumers in Spain, constituting 40% of the European population. The Spanish horticulture sector’s production exceeds 4.5 million tons, cultivated across 42,000 hectares of greenhouse, primarily in the province of Almeria (31,500 ha). Approximately 75% of the production is earmarked for export, with 27% to Germany, 16% to France, 15% to the United Kingdom, and 9% to the Netherlands, while only 25% remains in Spain.

The principal distribution channel involves major European retailers (e.g., Aldi, Edeka, Tesco, Carrefour, and Lidl), accounting for 70% of Spanish producers’ sales (Pérez-Mesa & Galdeano-Gómez, 2015). These retailers establish stringent production quality standards and promote social responsibility and environmentally sound practices. However, these practices, often unknown to the end consumer, may be misrepresented by the mass media, generalizing inadequate management by a minority in the sector. This, coupled with growing environmental awareness and consumer concerns about food safety, poses a potential threat to the sector’s image and reputation (Pérez-Mesa et al., 2019).

Negative news, much of it from academic sources (Días & Reigada, 2018), has significantly influenced consumer perceptions of the sector. Despite this, there exist contrasting facts, including scientific evidence supporting the health standards, sustainability, and efficiency of the sector (Castro et al., 2019).

The primary objective of the present study is to investigate whether the framing of news, influenced by the choice of information sources, can contribute to the emergence or propagation of crises in the agri-food sector. Such crises can significantly impact the sector’s viability, highlighting the influential role of the media compared to objective and accurate information provided by the sector or specialized academic studies. In this context, a potential monitoring and control scheme is proposed, which could be implemented by the affected sector. A comprehensive analysis of how media framing can lead to image crises in the horticultural sector is crucial for an effective and efficient response to mitigate its effects.

Specifically, this article aims to ascertain whether the damaged external image and reputation of the Spanish greenhouse horticulture sector result from negative news that neglects to analyze solutions and opinions presented by the sector itself or those endorsed by credible and verifiable sources.

Beyond the specific case study, this paper contributes to the literature in several ways: (i) by extending the understanding of the consequences of news framing generated by mainstream media, with a focus on their role in agri-food crisis creation and propagation; (ii) by analyzing the origins of bias in this framing and how sources are utilized; and iii) by proposing a monitoring and control scheme, managed by the affected sector, grounded in a comprehensive comprehension of the aforementioned aspects.

Conceptual framework: media framings and image agricultural crisis

Media framing theory in agriculture

This study examines the influence of media and communication on individuals’ perceptions and interpretations of information, potentially leading to image crises affecting companies or sectors. Framing Theory (FT) serves as a fundamental theoretical framework for addressing this issue, positing that the presentation or “framing” of information can shape people’s understanding and reactions (Shaw, 1979). In essence, the media can manipulate discourse to set agendas (Adams et al., 2014; Rust et al., 2021). In summary, FT asserts that how information is presented in the media influences how people perceive and understand it. Frames can also impact perceptions by manipulating tones, thereby altering public support for policies (Rust, 2015). Media frames, crafted by journalists and other actors, simplify and direct attention to specific aspects of a topic, influencing public perception and decision-making. The framing process encompasses three stages: inputs (objectives, ideologies, other media features), processes (frame construction by journalists, including sources used), and outcomes (public perceptions of the information).

In general, the literature has paid limited attention to the influence of specific newspaper characteristics on reporters’ performance. Research suggests that reporters, information subsidies, newspaper circulation size, and location impact the attributes of sources and the type of information provided. For instance, studies have highlighted the reliance of reporters for larger regional and national newspapers on news subsidies (Lehman-Wilzig & Seletzky, 2012). Conversely, larger newspapers statistically use a greater number of scientists and agricultural scientists as sources (White & Rutherford, 2012). Newspapers in larger and more diverse communities tend to provide greater coverage of controversial science topics, such as environmental contamination, and trending topics like immigration. This holds implications for specific agricultural sectors involved with controversial subject matter in their respective areas (Perez-Mesa et al., 2019). Some studies argue that there is an imbalance in the media due to a higher frequency of negative messages (Boehm et al., 2010). In response, the farming press has recently tended to use more positive tones when covering sustainable agricultural practices (Rust et al., 2021), which, unfortunately, has led to misdiagnosis at times (Gibson et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2022).

In summary, this study elucidates the actions of the media through the framing of news, shaped by several factors: i) in the initial stage, the media’s ideological orientation, scope of coverage, expected impact, etc., exert significant influence; ii) during the second stage (frame construction by journalists), the journalist’s individual perspective and their selection of sources become crucial; iii) ultimately, this framework evolves into a simplified and recurrent idea, impacting consumer perception. Moreover, recognizing these ideas is a crucial aspect in identifying unresolved issues.

Media influence on food crisis

According to Van Asselt et al., 2017, the term ‘crisis’ is defined as “an urgent, dynamic situation that is rapidly changing with unpredictable outcomes, poorly understood, and has an impact on society and politics.” Crises are considered negative changes in security, economic, political, social, and environmental affairs, especially when they occur unexpectedly and with little warning (Çesmeci et al., 2013). Generally, a crisis event involves uncertainty about what has occurred, its causes, and what might occur later (Broekema et al., 2018). Common consequences of crises include a decrease in sales and market shares and widespread negative publicity (Vassilikopoulou et al., 2009). Specifically, in the case of agri-food, economic impact analyses are limited, and measuring said impact is a complex task (Hu & Baldin, 2018).

In the food industry sector, the Codex Alimentarius defines the term ‘food crisis’ as “a situation, whether accidental or intentional, that is identified by a competent authority as constituting a serious and as yet uncontrolled foodborne risk to public health that requires urgent action”. Notably, a food safety event can be categorized as an ‘accident’ or ‘incident,’ evolving from a minor occurrence to a major crisis at any moment (Chammem et al., 2018). Incidents can result in significant health risks or a decline in consumer well-being, causing widespread consumer concern and disrupting national and international trade, as demonstrated by the severe Escherichia coli outbreak in Germany in 2011 (Van Asselt et al., 2017). In this case, the Hamburg authorities incorrectly attributed the outbreak to cucumbers from Spain, prompting an alert against the consumption of tomatoes, lettuce and cucumbers and impacting all horticulture products from the region. Despite later acknowledgment that the outbreak did not originate in Spain, the damage was done as the “official” source had already been reported in the press (Pasiliao, 2012). Consumption was severely affected, leading to a drastic fall in prices in both national and export markets (Pérez-Mesa et al., 2019).

Several studies follow a similar pattern, analyzing how the framing of news stories influences sector states. For example, the German press’s treatment of the BSE crisis, where media coverage tended to politicize food hazards affecting industrial agriculture (Feindt & Kleinschmit, 2011), or the contemporary impact on the livestock sector of the media’s treatment of red meat consumption (Sievert et al., 2022). Research by Gibson et al. (2020) reveals that consumers primarily rely on the media for agricultural information, leading to misconceptions about its environmental impact. Ideology and political trends, in conjunction with media influence, limit the introduction of solutions beneficial to both consumers and producers. This is evident in discussions about Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs), where public discourse is heavily influenced by vested interests without scientific basis (Mathur et al., 2017; Varzakas et al., 2007).

While a food safety incident is unintentional, food fraud is intentional and driven by economic interests (Chammem et al., 2018). In either case, a lack of specific information, fueled by mass media coverage, can heighten consumers’ risk perceptions, potentially leading to reduced demand for affected food products (Frewer et al., 2002; Verbeke, 2005). Consequently, food crises can trigger strong consumer reactions, significantly impact food export markets, and have important political implications (Swinnen et al., 2005). Sometimes, a crisis may involve an entire category of products, as seen in the mad-cow disease crisis (Van Heerde et al., 2007).

Within the context of food crises, it is crucial to highlight those related to food safety, which frequently occur and can affect a wide variety of food products. Food safety concern is defined as “the degree of consumers’ anxiety regarding the quality of processed foods, food additives, and pesticide residues that could jeopardize their physical health”. Potential impacts on consumer demand extend beyond the directly affected products to other categories. In recent years, consumers have become increasingly concerned about health risks associated with food consumption (Röhr et al., 2005). However, assessing risks related to food safety has become challenging for the general public. Consequently, consumers must rely on producers, retailers, regulators, and even the media to minimize potential health impacts (Lobb et al., 2007).

Simultaneously, another type of crisis exists, originating not from a specific food safety risk but from events or factors that directly influence consumers’ perceptions. These situations are commonly related to production and resulting negative externalities (e.g., environmental impact, working conditions, etc.). Agricultural crises can be categorized based on their relationship with environmental impact, social well-being, and/or economic profitability (Reganold & Wachter, 2016). Ultimately, crises can compromise the economic viability of a company or sector, adversely affecting its future sustainability. Such crises may result from temporary or structural changes (e.g., price or demand decreases, increased competition, and overproduction). It’s essential to note that environmental or social crises, if chronic, can impact the economic viability of the company or sector. Additionally, these crises may arise from mass media coverage or, on other occasions, emerge from the media due to preconceived or biased ideas, equivalent to smear campaigns (Fig. 1).

The figure illustrates that various types of crises can occur in the agri-food sector, often in combination, resulting in a loss of prestige and reduced profitability. Source: adapted from Pérez-Mesa et al. (2019).

Methodology

First, given the growing body of evidence on image crises in the Spanish horticulture sector, it is essential to identify how these crises are addressed in European media. A compilation of news has been conducted using various sources: (1) a bibliographic review of press news related to the sector (European Newsstream); and (2) information requested from press departments of sectoral associations (APROA, HortiEspaña). The Newsstream search included the terms: Almeria AND greenho*, resulting in a total of 19 documents. The database compiled by APROA and HortiEspaña had a total of 30 news references. From the joint review, a total of 34 news items were obtained, to which 2 additional items were added as a result of a more general search in Google News. The total number of news items analyzed was 36. It is at this point that FT becomes relevant as a method for understanding the motivations and simplifications applied in news reporting. This approach enables the extraction of recurrent ideas or frames used by the media, serving as indicators of unresolved problems.

Second, to better understand whether there is any bias in the construction of the information framework, we contrast whether journalistic information aligns with that obtained from academic sources. With the aim of studying the collective analysis conducted in the academic literature on this phenomenon, searches were carried out in the Web of Science and SCOPUS databases using the following keywords: [Almería* AND Susta* AND Agri* OR greenho* (Abstract, Topic)]. This search was conducted for the period 2010–2020. Also, the cross-referencing method, also known as “snowballing,” was employed by examining the references and citations of the previously selected articles. It was completed with a general review in Google Scholar to detect any gray literature. Finally, only 42 publications were included. The search followed the PRISMA scheme for a systematic literature review. The summary of the process can be seen in Fig. 2.

The figure illustrates the systematic review process, following the PRISMA scheme, summarized in four phases. Out of an initial total of 146 references selected, only 42 were deemed relevant for the research. These references were limited to journals related to the fields of Ecology, Agriculture, Science Technology, Water, Energy, Business, Economics, and Engineering.

Third, as an alternative position, the production sector maintains a different view that attests to the efforts made in recent years to counteract the criticism presented in the general media. This information was compiled from in-depth interviews with the directors of associations representing the sector (APROA, HortiEspaña) as a means of gathering counterarguments. Furthermore, an attempt was made to corroborate the data supplied with official statistics sources or specialized bibliography. It is important to note that during this phase, the process of reviewing the scientific and gray literature was revisited. Combining the news items, research articles, and face-to-face interviews provides a more comprehensive understanding of factual accuracy. We recognize that news items are simplifications or “frames” of reality, which may, therefore, contain biases. These biases can be identified by contrasting said frames with the academic and sectorial perspectives on the same subject.

Fourth, to conclude, based on the previous analysis, we are in a position to propose a proactive crisis detection and management model that could be used by the sector to counteract news framing that may lead to agri-food crises. As a summary, the methodology used can be seen in Fig. 3.

The figure shows the methodology followed. It starts with a review of the general press to obtain the most relevant topics. This information will be contrasted with scientific literature and the opinion of representatives of the greenhouse sector. By analyzing the findings from these phases, a response model can be developed for the sector to address crises stemming from biased news framing, among other factors. Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Results and discussion

The position of the European media and its relation to the academic literature

The mass media sector in Spain has undergone several crises in the last decade, significantly impacting its perceived image. The Spanish greenhouse sector consistently faces crises that pose both threats and opportunities, requiring organizations to adeptly respond. Despite concerted efforts, recurring crises stem from the ineffective management of common issues within the Spanish horticulture sector.

Table 1 outlines the crises experienced by the sector, with a notable focus on immigrant workers’ status and environmental concerns. It is crucial to note that health issues related to pesticide traces ceased to be the dominant topic after 2011, following a false accusation of deaths attributed to E. coli-contaminated Spanish vegetables (Pasiliao, 2012). Over the past decade, a single Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASS) incident occurred, involving pesticides in Spanish fruit and vegetables, specifically melons.

Analysis of news headlines and content reveals subjective approaches, including the defense of tomatoes grown in France, Spain’s top competitor in organic horticulture, and support for local crops during Brexit negotiations in the United Kingdom. Some topics exhibit eclecticism. International news is primarily disseminated in importing countries, reflecting strong loyalty to the “local” production sector. These patterns align with a well-established ethnocentric tradition, where the commitment to purchasing domestic products and boycotting foreign products is expressed economically (Ma et al., 2020).

In this context, numerous local companies strive to promote ethnocentrism, aiming to foster consumer preferences for local goods, encompassing products, services, and brands. The Spanish case serves as a paradigm, illustrating these practices and highlighting that news originates from media sources with clearly defined politically oriented editorial perspectives. Nevertheless, it is evident that this type of news generally lacks the inclusion of opposing opinions outside the mainstream.

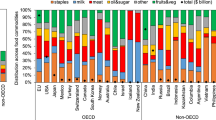

Alternatively, prevalent news frames may suggest an unresolved problem. Figure 4 affirms that issues like “denunciations of illegal working conditions,” the management of “plastics,” and other environmental concerns are noteworthy points of conflict deserving special attention. Additionally, the sources used in the news (Fig. 4, right) indicate a focus on accusations made by immigrant workers or labor associations on behalf of this group. It is crucial to note that many news items are indirectly derived from previously published stories. Unfortunately, business sector associations, academia, and experts are seldom consulted when addressing such issues, contributing to a prevailing sensationalistic approach in the media’s treatment of the sector.

Figure on the left, shows a cloud of concepts most frequently used in the news. Social aspects and waste generation are the most relevant issues. On the right, the sources referenced in the news items have been summarized. Interviews with migrant workers and the compilation of past work are the most common news sources.

In this context, FT elucidates why the media provides increased coverage to contentious science topics, such as environmental contamination, and trending subjects like immigration. Indeed, the study area itself possesses distinctive features that attract media attention: (i) extremely arid and desert landscapes, (ii) an exaggerated concentration of greenhouses (“the sea of plastic”) consuming water resources and generating waste, and (iii) a geographical location amidst illegal immigration routes from northern Africa, characterized as one of the most unequal borders globally. These elements collectively create an ideal context to amplify the content of any given news item. In essence, southeast Spain emerges as an optimal focal point for media attention, irrespective of the conveyed message, capturing considerable interest from followers of major media outlets, as indicated in Table 1.

Similarly, it is noteworthy that a relationship seems to exist between the number of scientific articles and news coverage in the general press (refer to Fig. 5). An examination of the origins of the authors of scientific articles, primarily affiliated with local universities and supportive of the greenhouse horticulture system, suggests that the surge in publications in recent years (2018–2020) may be a reactionary response aimed at justifying the prevailing production model within the sector.

The analysis of academic documents revealed a series of investigations highlighting various negative aspects associated with the sector: (i) substandard social conditions for immigrant workers (Du Bry, 2015; Chesney et al., 2019; Medland, 2016; Pumares & Jolivet, 2014); (ii) environmental degradation (Grindlay et al., 2011; Juntti & Downward, 2017); (iii) excessive use of fertilizers and pesticides leading to diminished production and consumption quality (Wainwright et al., 2014); and iv) adverse synergies arising from the intensive agriculture model (Díaz & Reigada, 2018).

In addition to the negative aspects, some findings indicate improvements made by the sector in recent years concerning economic, social, and environmental sustainability. In summary, while there are insightful articles addressing each dimension individually, there is a noticeable absence of integrative analyses addressing the overall sustainability of the sector. This gap suggests a potential avenue for future research. These references have been compiled in Table 2 to substantiate the arguments presented by sector leaders.

Position of local grower associations and its relationship with the academic literature

Table 2 displays the opinion of the sector summarized in terms of socio-economic and environmental achievements. It is worth highlighting that these positive arguments are published in local and specialized media, yet seldomly in general national and international media. This discrepancy then poses the question of whether this imbalance is the result of inaction on the part of the sector at origin to improve their marketing efforts or, instead, the information bias of the media. As far as the sector is concerned, in most cases, attempts have been made to contact the authors/editors of the negative news with the aim of providing an alternative viewpoint.

Findings and discussion

The comparison between press information and the verified opinion of the greenhouse-producing sector reveals the presence of information biases in mass media, potentially influencing the image and reputation of a business sector abroad. The analysis of this specific case highlights conflicting perspectives, with the general media denouncing the situation while representative sector organizations and scientific articles defend it.

The examination of news reports in the press (Table 1) indicates that, in some instances, they are based on academic studies analyzing crises within the Spanish horticulture sector. However, in other cases, they seem to stem from preliminary information, reflecting opportunistic scenarios. To enhance impartial reporting and confirm accuracy, it is advisable for the mass media to approach the sector of origin, seeking contrasting positions or alternative views, and potentially consulting opposing academic viewpoints. Such actions would contribute to countering the emerging trend of biased news. From the sector’s perspective, verifiable facts attest to ongoing efforts to improve and evolve, which unfortunately remain unknown to end customers due to the gradual nature of the process and its lack of newsworthiness.

Despite academic literature presenting a balanced view of arguments for and against the sustainability of the horticulture sector, the news analysis conducted herein indicates a general focus on negative aspects in the media. This aligns with previous research indicating a relationship between news framing and consequences for the involved sector (Feindt & Kleinschmit, 2011; Rust et al., 2015; Sievert et al., 2022). Biased utilization of news toward negative aspects is evident, impacting the sector (Gibson et al., 2020; Rust et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2022). The study also verifies the partial use of academic sources (White & Rutherford, 2012). Notably, the study identifies general factors beyond individual interests that explain the negative bias in news, suggesting biases may exist across sectors. In the case study, negative and biased opinions toward the greenhouse sector are evident in media from countries with competing agricultural production, such as France and the Netherlands. The German and British press, on the other hand, seem influenced by strong non-governmental environmental organizations. In the Spanish case, media opposing the sector exhibit more progressive editorial lines, with some leaning toward liberal tendencies.

From a theoretical perspective, this article adopts a holistic view of a complex process that resists isolated study. Although news and ideology, news framing, news coverage, and image repair are sometimes considered different theoretical perspectives, we argue that they form a closely connected set of concepts.

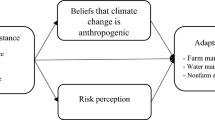

Proposition of a proactive image crisis detection and management model

Regarding additional considerations, it is evident that associations representing agricultural sectors should establish a response protocol aimed at disrupting the information asymmetry existing between farmers and consumers. Achieving this requires consumers to be aware of the efforts made by farmers, introducing a new field of study beyond the conventional concept of information asymmetry in the agricultural sector (Minarelli et al., 2016; Verbeke, 2005). To address this, it is proposed to implement an action plan based on controlling, tracking, and rectifying potential crises affecting an agricultural sector while countering biased news in the media (Fig. 6). Numerous studies have explored how organizational or sectoral crises should be managed, considering internal factors (organizational preparedness and learning processes) and external factors (stakeholder relationships) (Bundy et al., 2017). Crises can be reactive, occurring post-crisis, or proactive, with managers anticipating crises (Batorski, 2021). The proposed model seeks to integrate internal and external perspectives in a proactive approach, recognizing that crisis response strategies are more effective when coupled with sincere efforts to address underlying issues (Gillespie & Dietz, 2009). Additionally, emerging research explores the influence of social media on an organization’s crisis management efforts (Utz et al., 2013; Sellnow & Seeger, 2021).

In practice, this Proactive Crisis Detection and Management Model (PODM) must initially establish a classification of potential crises that pose risks to image and economic viability (Pérez-Mesa et al., 2019). Crises may be predictable and detectable in advance through the use of indicators. In some cases, a single factor, such as the detection of trace chemicals exceeding allowed limits, could trigger an unforeseen crisis. The use of indicators and diagnostics aids in predicting random crises, imbuing the model with a proactive nature. Aligning with Alpaslan et al. (2009): “Get the worst about yourself out on your time before the media dig it.” For negative news, tracking such information, as illustrated in Table 1, serves as a detection strategy (indicator) for other potential crises (e.g., health-related, environmental, or social) that become chronic occurrences. Recurrent frames signal unresolved problems guiding the sector toward image restoration. These indicators prompt the implementation of corrective measures in the medium or short term, such as increased chemical analysis controls and reporting illicit activities to authorities.

These actions should be communicated and disseminated promptly by the sector, balancing speed with strategic precision. Proactive communication is essential, with emergency reactive responses launched when necessary, always ensuring that information is received and assimilated by end consumers. Social media, in particular, can effectively inform the public about risks, preventing confusion and scaremongering (Regan et al., 2016). In cases where indicators reveal chronic situations, a long-term or partial redefinition of agricultural activity becomes necessary. This requires coordination among companies, authorities, and other stakeholders to define the desired future and establish a comprehensive long-term strategic plan for successful implementation. The described steps aim to contribute to a body of scientific knowledge, fostering collaboration with academic institutions (universities or research centers) to publish scientifically supported arguments validating the implemented structural improvements. These verifiable arguments should form the foundation of a stable communication strategy over time, progressively reducing the information asymmetry between the actual work carried out by growers at the origin and the perceived image by end consumers. The objective is to establish a unique production-consumer identity through multimodal communication (Coombs, 2014; Knight & Tsoukas, 2019), encompassing newspapers, television, social media, and rallies.

During the model’s implementation, information generated by the sector should be verified with other stakeholders (customers, society, research centers, etc.) to incorporate diverse perspectives (Alpaslan et al., 2009). Comparative studies must also be conducted to compile data on other production circumstances (in other countries, with different systems, etc.).

The proposed scheme aligns with lessons learned from past sectoral crises (Crichton et al., (2009); Batorski, 2021), involving: (i) analyzing cumulative information on incidents and assessing the success of interventions and modifications; (ii) efficiently disseminating information on incident causation and suitable interventions/modifications to all stakeholders; (iii) implementing a system to ensure that lessons learned endure; iv) acknowledging that this process demands substantial resources, dedicated effort, and commitment from the involved entities; and integration into the organizational or sectoral culture.

Conclusions

Traditionally, the term “crisis” in the agrifood sector has been linked to situations affecting consumer health. Over time, the concept has broadened to encompass negative situations related to environmental sustainability, social issues, and economic challenges. These crises significantly impact the perceived image of products, sectors, or even entire countries among consumers. In today’s digital age, the role of information is pivotal in shaping consumer opinions. The biased use of such information can trigger substantial crises in the agrifood sector, necessitating an exploration of effective crisis management strategies.

Citizens’ and consumers’ information consumption habits are undergoing significant transformations. The complexity of obtaining impartial information is exacerbated by the multitude of available sources. General media outlets, facing digital competition and traditional format challenges, may succumb to pressures to maintain audience levels, potentially resulting in biased information dissemination. For sectors or companies, the presence of negative news can lead to irreparable damage, particularly in the highly sensitive agrifood sector, where consumer health is a central concern. While much negative news is well-researched and tied to food crises, there is a growing body of information addressing environmentally and socially detrimental situations. It is important to note, however, that some news items may be spurious and biased, intentionally seeking to denigrate a company or sector. This approach aligns with the post-truth mechanism, aiming to manipulate consumer opinions.

In the specific case of the analysis of greenhouse horticulture in southeast Spain, the news draws on topics previously addressed in the scientific bibliography. However, a significant portion of the presented news exhibits a negative bias, often lacking the alternative perspective provided by growers’ representatives, which is verifiable through official sources and academic literature. Instead, this alternative viewpoint tends to be relegated to local and specialized media outlets, contributing to information asymmetry between producers and consumers. In response, it is imperative for producers, companies (cooperatives), and sector associations to establish an action plan, such as a Proactive Crisis Detection and Management (PCDM) model, to detect, quantify, diagnose, implement solutions, and communicate scientifically verifiable information to consumers. The ultimate aim is to empower consumers to form their own objective opinions. Within this context, social media should assume a crucial role, incorporating the opinions of producers and their representatives by default in their news. Media outlets should also juxtapose their information with alternative competitive situations, such as showcasing the state of similar production areas in France, Holland, Morocco, Turkey, Senegal, Egypt, etc. This benchmarking process, if maintained objectively, would mitigate subjectivity in the presented information.

This article exhibits notable limitations as it grapples with a complex situation requiring the inclusion of multiple perspectives, encompassing not only economic considerations but also sociological, journalistic, agronomic, and environmental viewpoints. While applied specifically to greenhouse horticulture, the analysis methodology could be extended to other agrifood production sectors to evaluate media coverage regarding their specific environmental concerns. A pertinent example could be the meat sector, which faces significant pressure in both social and academic spheres (Moran & Blair, 2021) and is confronted with an existential threat to livestock production due to evolving consumption decisions and investors seeking to mitigate potential liabilities related to greenhouse gas emissions.

Data availability

Bibliographic data analyzed and used are reflected in the article or come from open access databases for researchers. The collection of press releases made available to researchers by the agricultural sector associations (APROA-HortiEspaña) is considered confidential. Nevertheless, any clarification on further details can be requested from the corresponding author.

References

Adams A, Harf A, Ford R (2014) Agenda setting theory: a critique of maxwell McCombs & Donald Shaw’s theory in Em Griffin’s a first look at communication theory. Meta Commun 4:1–15

Alpaslan CM, Green SE, Mitroff II (2009) Corporate governance in the context of crises: towards a stakeholder theory of crisis management. J Contingencies Crisis Manag 17:38–49

Aznar-Sánchez JA, Galdeano E, Pérez-Mesa JC (2011) Intensive horticulture in almeria (Spain): a counterpoint to current european rural policy strategies. J Agrarian Change 11(2):241–261

Batorski, J (2021). Crisis Management: The Perspective of Organizational Learning. In Eurasian Business Perspectives: Proceedings of the 29th Eurasia Business and Economics Society Conference (pp. 75-86). Springer International Publishing

Bundy J, Pfarrer MD, Short CE, Coombs WT (2017) Crises and crisis management: integration, interpretation, and research development. J Manag 43(6):1661–1692

Broekema W, Van Eijk C, Torenvlied R (2018) The role of external experts in crisis situations: a research synthesis of 114 post-crisis evaluation reports in the Netherlands. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 3:20–29

Boehm J, Kayser M, Spiller A (2010) Two Sides of the Same Coin? Analysis of the Web-Based Social Media with Regard to the Image of the Agri-Food Sector in Gemany. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn 3:264–278

CAP, Consejería de Agricultura, Pesca y Desarrollo Rural (2016). trazabilidad en hortalizas. Junta de Andalucía. Available at: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/agriculturaypesca/ifapa/servifapa/registro-servifapa/0925b9f7-d92f-4017-992c-e69501768455/download [accessed 1th November 2022]

CAP, Consejería de Agricultura, Pesca y Desarrollo Rural (2020). Producción ecológica y producción integrada. Available at: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/export/drupaljda/DECO21_Balance_Estadistico_Produccion_Ecologica_2020_v1.pdf [accessed 1st April 2022]

Carreño-Ortega, A, Galdeano-Gómez, E, Pérez-Mesa, JC (2017). Policy and environmental implications of photovoltaic systems in farming in southeast Spain: can greenhouses reduce the greenhouse effect? Energies, 10(6):761

Castro AJ, López-Rodríguez MD, Giagnocavo C, Gimenez M, Céspedes L, La Calle A, Gallardo M, Pumares P, Cabello J, Rodríguez E, Uclés D, Parra S, Casas J, Rodríguez F, Fernandez-Prados JS, Alba-Patiño D, Expósito-Granados M, Murillo-López BE, Vasquez LM, Valera DL (2019) Six collective challenges for sustainability of almeria greenhouse horticulture. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16:4097

Çesmeci, N, Özkaynak, S, Ünsalan, D (2013). The effect of crises on leadership, in Koyuncugil, A.S. and Ozgulbas, N. (Eds), Technology and Financial Crisis: Economical and Analytical Views, IGI Global, Hershey, PA: 50-58

Chammem N, Issaoui M, De Almeida A, Delgado A (2018) Food crises and food safety incidents in European Union, United States, and Maghreb Area: current risk communication strategies and new approaches. J AOAC Int 10(4):923–938

Chesney T, Evans K, Gold S, Trautrims A (2019) Understanding labour exploitation in the Spanish agricultural sector using an agent based approach. J Clean Prod 214:696–704

Coombs, WT (2014). Ongoing Crisis Communication: Planning, Managing, And Responding. Ed. Sage Publications

Crichton MT, Ramsay CG, Kelly T (2009) Enhancing organizational resilience through emergency planning: learnings from cross‐sectoral lessons. J Contingencies Crisis Manag 17(1):24–37

Duque-Acevedo, M, Belmonte-Urena, L, Plaza-Ubeda, J, Camacho-Ferre, F (2020). The Management of Agricultural Waste Biomass in the Framework of Circular Economy and Bioeconomy: An Opportunity for Greenhouse Agriculture in Southeast Spain. Agronomy, 10(4)

Díaz E, Reigada A (2018) Intensive agriculture under plastic in Andalusia (Spain): a production model in question. Int J Iber Stud 31(3):183–201

Du Bry, T (2015): Agribusiness and Informality in Border Regions in Europe and North America: Avenues of Integration or Roads to Exploitation? J Borderl Stud, 30(4)

European Food Safety Authority (2017) The 2015 European Union report on pesticide residues in food. EFSA J 15(4):e04791

Egea F, Torrente R, Aguilar A (2017) An efficient agro-industrial complex in Almeria (Spain): Towards an integrated and sustainable bioeconomy model. New Biotechnol 40:103–112

European Union (2017): Operating subsidies (both direct payments and rural development except investment support). Available at: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/common-agricultural-policy/income-support/income-support-explained_en [accessed 20th April 2021]

Feindt PH, Kleinschmit D (2011) The BSE crisis in German newspapers: reframing responsibility. Sci Culture 20(2):183–208

Frewer LJ, Miles S, Marsh R (2002) The media and genetically modified foods: evidence in support of social amplification of risk. Risk Anal: Int J 22(4):701–711

Galdeano E, Aznar-Sánchez JA, Pérez-Mesa JC (2013) Sustainability dimensions related to agricultural based-development: the experience of 50 years of intensive farming in Almeria (Spain). Int J Agric Sustain 11(2):125–143

Galdeano-Gómez, E, Aznar-Sánchez, JA, Pérez-Mesa, JC (2016). ContribucioneS Económicas, Sociales Y Medioambientales De La Agricultura Intensiva De Almeria Almeria: Cajamar Caja Rural

Galdeano-Gómez E, Aznar-Sánchez JA, Pérez-Mesa JC (2017) Exploring synergies among agricultural sustainability dimensions: an empirical study on farming system in Almeria (Southeast Spain). Ecological Economics 140:99–109

Giagnocavo C, Galdeano-Gómez E, Pérez-Mesa JC (2018) Cooperative longevity and sustainable development in a family farming system. Sustainability 10(7):2198

Gibson KE, Lamm AJ, Lamm KW, Warner LA (2020) Communicating with diverse audiences about sustainable farming: does rurality matter? J Agric Educ 61(4):156–174

Gillespie N, Dietz G (2009) Trust repair after an organization-level failure. Acad Manag Rev 34:127–145

Grindlay AL, Lizárraga C, Rodríguez MI, Molero E (2011) Irrigation and territory in the southeast of Spain: evolution and future perspectives within new hydrological planning. WIT Trans Ecol Environ 150:623–637

Hu L, Baldin A (2018) The country of origin effect: a hedonic price analysis of the Chinese wine market. Br Food J 120(6):1264–1279

ICEX (2021). Export data, Spanish Institute for Foreign Trade, Madrid. Available at: www.icex.es [accessed 5th June 2022]

IFAPA (2016). El sistema de producción hortícola protegido de la provincia de Almeria. Available at: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/agriculturaypesca/ifapa/servifapa/registro-servifapa/05ca752a-b1ff-4e6a-8c77-d706f90f20bc [accessed 13th May 2021]

Izquierdo ÁV, Molina L, Bosch AP, Martos FS, Gisbert J (2004) “Caracterización del contenido en nitratos y pesticidas en las aguas subterráneas del Campo de Dalias (Almería)”. Geotemas 6:193–196

Jones JL, White DD, Thiam D (2022) Media framing of the Cape Town water crisis: perspectives on the food-energy-water nexus. Reg Environ Change 22(2):79

Juntti M, Downward SD (2017) Interrogating sustainable productivism: lessons from the ‘Almerian miracle’. Land Use Policy 66:1–9

Knight E, Tsoukas H (2019) When fiction trumps truth: what ‘post-truth’and ‘alternative facts’ mean for management studies. Organization Stud 40(2):183–197

Lehman-Wilzig S, Seletzky M (2012) Elite and popular newspaper publication of press releases: Differential success factors?. Public Relat J 6(1):1–25

Livre Blanc (2017). Les Producteurs de Légumes de France. Available at: https://www.vegenov.com/vars/fichiers/Livre%20blanc%20L%E9gumes%20de%20France%202020.pdf [accessed 28th May de 2022]

Lobb AE, Mazzocchi M, Traill WB (2007) Modelling risk perception and trust in food safety information within the theory of planned behaviour. Food Qual Preference 18(2):384–395

Ma J, Yang J, Yoo B (2020) The moderating role of personal cultural values on consumer ethnocentrism in developing countries: The case of Brazil and Russia. J Business Res 108:375–389

MAPA, Ministerio de Agricultura (2015). Análisis de carbono en el sector agroalimentario español. Available at: http://www.upahuella.com/upahuella/Documentos_Generales_HC_UPA.html [accessed 6th June 2022]

Mathur V, Javid L, Kulshrestha S, Mandal A, Reddy AA (2017) World cultivation of genetically modified crops: opportunities and risks. Sustain Agric Rev 25:45–87

Medland L (2016) Working for social sustainability: insights from a Spanish organic production enclave. J Agroecol Sustain Food Syst 40(10):1133–1156

MESS, Ministerio de Empleo y Seguridad Social (2017). Estadísticas. Available at: http://www.seg-social.es [accessed 14th mayo 2022]

Minarelli, F, Galioto, F, Raggi, M, Viaggi, D (2016). Asymmetric information along the food supply chain: a review of the literature. In 12th European International Farming Systems Association (IFSA) Symposium: 12-15

Moran, D, Blair, KJ (2021). Review: Sustainable livestock systems: anticipating demand-side challenges. Animal, In Press, 100288,

OPAM, Observatorio Permanente Andaluz de las Migraciones (2017). Estadísticas: Padrón de habitantes. Available at: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/justiciaeinterior/opam/es/node/90 [accessed 14 April de 2022]

Pasiliao, R (2012). The Curious Case of the Spanish Cucumber - A Lesson on Proportionality. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2177127 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2177127

Pérez-Mesa JC, Galdeano-Gómez E (2015) Collaborative firms managing perishable products in a complex supply network: an empirical analysis of performance. Supply Chain Manag: Int J 20(2):128–138

Pérez-Mesa JC, Serrano-Arcos MM, Sánchez-Fernández R (2019) Measuring the impact of crises in the horticulture sector: the case of Spain. Br Food J 121(5):1050–1063

Piedra-Muñoz L, Vega-López L, Galdeano-Gómez E, Zepeda-Zepeda J (2018) Drivers for efficient water use in agriculture: an empirical analysis of family farms in Almeria, Spain. Exp Agric 54(1):31–44

Pumares, P, Jolivet, D (2014). Origin matters: Working conditions of Moroccans and Romanians in the greenhouses of Almeria, in Gertel, J. and Sippel., S.R. (Eds), Seasonal Workers in Mediterranean Agriculture. The Social Costs of Eating Fresh, Routledge, New York, NY: 130-140

Regan A, Raats M, Shan LC, Wall PG, McConnon A (2016) Risk communication and social media during food safety crises: a study of stakeholders’ opinions in Ireland. J Risk Res 19(1):119–133

Reganold JP, Wachter JM (2016) Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nat Plants 2(2):1–8

Röhr A, Lüddecke K, Drusch S, Müller MJ, Alvensleben RV (2005) Food quality and safety – consumer perception and public health concern. Food Control 16(8):649–655

Rust NA (2015) Media framing of financial mechanisms for resolving human–predator conflict in Namibia. Human Dimens Wildlife 20:440–453

Rust NA, Jarvis RM, Reed MS, Cooper J (2021) Framing of sustainable agricultural practices by the farming press and its effect on adoption. Agric Hum Values 38(3):753–765

Shaw EF (1979) Agenda-setting and mass communication theory. Gazette 25:96–105

Serrano-Arcos MM, Sánchez-Fernández R, Pérez-Mesa JC (2020) Is there an image crisis in the Spanish vegetables? J Int Food Agribusiness Market 32(3):247–265

Sievert K, Lawrence M, Parker C, Russell CA, Baker P (2022) Who has a beef with reducing red and processed meat consumption? A media framing analysis. Public Health Nutrition 25(3):578–590

Sirieix L, Salançon A, Rodriguez C (2008) Consumer perception of vegetables resulting from conventional field or greenhouse agricultural methods. UMR MOISA: Marchés, Organisations, Institutions et Stratégies d’Acteurs: CIHEAM-IAMM, CIRAD, INRA, Montpellier SupAgro, IRD-Montpellier, France

Sellnow, T, Seeger, M (2021). Theorizing Crisis Communication. Ed. John Wiley & Sons, Malden, MA, USA

Swinnen JF, McCluskey J, Francken N (2005) Food safety, the media, and the information market. Agric Econ 32:175–188

Tolón A, Lastra X (2010) La agricultura intensiva del poniente almeriense Diagnóstico e instrumentos de gestión ambiental. M+A. Revista Electrónic@ de Medio Ambiente 8:18–40

Tout D (1990) “The horticulture industry of Almeria Province, Spain”. Geogr J 156(3):304–312

Utz S, Schultz F, Glocka S (2013) Crisis communication online: How medium, crisis type and emotions affected public reactions in the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Public Relat Rev 39:40–46

Valera, D, Belmonte Ureña, LJ, Molina Aiz, FD, López Martínez, A (2014). Los invernaderos de Almeria. Análisis de su tecnología y rentabilidad. Ed. Cajamar Caja Rural. Almeria

Van Asselt ED, Van der Fels-Klerx HJ, Breuer O, Helsloot I (2017) Food safety Crisis management – a comparison between Germany and the Netherlands. J Food Sci 82(2):477–483

Van der Blom J, Robledo J, Torres S, Sánchez JA (2010) Control biológico en horticultura en Almeria: un cambio radical, pero racional y rentable. Cuadernos Estud Agroalimentarios 1:45–60

Van Heerde H, Helsen K, Dekimpe MG (2007) The impact of a product-harm crisis on marketing effectiveness. Market Sci 26(2):230–245

Varzakas TH, Arvanitoyannis IS, Baltas H (2007) The politics and science behind GMO acceptance. Critic Rev Food Sci Nutr 47(4):335–361

Vassilikopoulou A, Siomkos G, Chatzipanagiotou K, Pantouvakis A (2009) Product-harm crisis management: time heals all wounds? J Retail Consum Serv 16(3):174–180

Verbeke W (2005) Agriculture and the food industry in the information age. Eur Rev Agric Econ 32(3):347–368

Wainwright, H, Jordan, C, Day, H (2014). Environmental impact of production horticulture, in Dixon, G.R. and Aldous, D.E. (Eds), Horticulture: Plants for People and Places, Springer, Dordrecht: 503-522

White JM, Rutherford T (2012) Impact of newspaper characteristics on reporters’ agricultural crisis stories: Productivity, story length, and source selection. J Appl Commun 96(3):9

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: J.C.P.M. Methodology: J.C.P.M. Sourcing for research materials: J.C.P.M., M.C.G.B., M.M.S.A. and R.S.F. Writing—original draft: J.C.P.M. Writing—review and editing: J.C.P.M., M.C.G.B., M.M.S.A. and R.S.F.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pérez-Mesa, J.C., García Barranco, M.C., Serrano Arcos, M.M. et al. Agri-food crises and news framing of media: an application to the Spanish greenhouse sector. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 901 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02426-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02426-y

This article is cited by

-

Perceived barriers and the price inflating effects of informal payments in fresh food retailing in urban Bangladesh

Discover Sustainability (2025)