Abstract

Understanding intercity linkage patterns is of great importance to understanding urbanization. With advancements in transportation, communication technology, and the availability of big data, the “death of distance” concept has gained significant attention. This paper analyzes the asymmetric spatial intercity linkage network in China’s economically developed YRDR based on big data derived from Spring Festival (SF) migration. The aim is to explore the determinants of these linkages considering multivariate distance factors. The findings indicate a notable pattern of asymmetry in the intercity linkage network of the YRDR between core and non-core cities. The spatial decay effect of geographic distance on intercity asymmetry linkage is observed. Despite technological advancements, geographic distance remains the most influential and decisive factor in determining intercity asymmetric linkages. While other attribute distances also play a positive role, their effects become complex when controlling for geographic distance. Understanding these attribute distances is essential in comprehending the decay effect. This study contributes to the empirical investigation of the “death of distance” debate and provides a practical analytical framework for analyzing the drivers of intercity linkage patterns. It enhances our understanding of intercity spatial linkages within the context of urbanization in China and offers valuable insights for formulating development policies in the YRDR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As open systems, cities establish intricate connections with other cities and regions through various means, such as economic, social, and cultural interactions (Berry, 1964; Taylor and Derudder, 2015). With the rapid advancement of information technology and the widespread implementation of transportation infrastructure supported by physical and virtual networks, intercity linkages are evolving from hierarchical to networked connections (Batty, 2013; Castells, 1992, 1999). Additionally, linkages based on urban functions are gradually being replaced by those driven by frequent flows of factors between cities (Brenner, 1998; Castells, 1996). These flows, encompassing different natures and levels, serve as the tangible drivers of intercity linkages, reflecting the connections between cities from various perspectives (Dai et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2015). A growing focus has recently been on population flows as a critical lens to illustrate intercity linkages (Raffnsøe, 2003; Xiao et al., 2021).

However, transportation and communication technology advancements have resulted in significant changes in human interactions (Shaw et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2023). People can now travel longer distances using automobiles, high-speed rail, and airplanes. Consequently, the frictional impact of geography on human mobility and social interaction has been argued to be diminishing. This perspective is often referred to as the “death of distance” (Wang et al., 2018), suggesting that modern information and communication technologies (ICT) have made geographic distance less restrictive for intercity social connections. However, critics of this notion (Bailey et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019) argue that it exaggerates the role of technological advancements. While technology has expanded people’s social mobility, it does not necessarily mean that individuals will take full advantage of it. Additionally, some researchers, such as Goldenberg and Levy (2009), have highlighted that geographic distance remains influential as people tend to rely on existing social relationships rather than the convenience offered by new technologies. This ongoing debate has led to numerous empirical studies utilizing emerging data sources, including location-based services, online social networks, and cell phone communication, to illuminate this topic (Andris, 2016; Han et al., 2018; Jeon, 2020).

In mobility, spatially dispersed areas are increasingly interconnected and communicated across borders (Castells, 1992; Pflieger and Rozenblat, 2010). However, while mobility contributes to the homogenization of different places (Soja, 2012), it also emphasizes the profound significance of geographical differences in everyday life and the functioning of social, political, and economic forces (Paul, 2009; Taylor and Derudder, 2015). As a result, the pursuit and construction of unique, distinct spaces remain strong (Massey, 1994), leading to a constant interplay between connected and differentiated spaces, characterized by a tug-of-war movement of equilibrium and differentiation (Hudson, 2020).

This dialectical process of connected and differentiated spaces reshapes the original geographical differences and imbalances (Soja, 2012), transforming urban spaces beyond their original spatial extent (Brenner, 1998; Taylor et al., 2010). Networks and networking in mobile contexts have the potential to reinforce, terminate, or disrupt geospatial differentiation and the spatial structures it produces (Lefebvre, 1991; Sheppard, 2002; Smith, 2008), further altering existing socio-spatial disparities (Leitner and Sheppard, 2002). Geospatial differences and socio-spatial unevenness can be partially expressed through the multidimensional concept of “distance”, which may exist in various forms.

Population flow represents the interaction between cities, essentially a process of artificial spatial reconfiguration of integrated production factors. The agglomeration and dispersion of various factors in city development are reflected in population flow patterns. Therefore, intercity linkages based on population flow also reflect the spatial connections of various economic and social factors among regional cities. Population urbanization is a phenomenon of population movement and migration, where many surplus rural laborers flock to cities or towns in developed regions during China’s modernization and transformation (Liu et al., 2015). The Chinese Spring Festival (SF) migration serves as a mirror reflection of population urbanization. Additionally, analyzing the SF migration network provides a valuable opportunity to utilize big data from a short period to uncover patterns of intercity linkages in urbanization and social change.

The higher intensity of intercity linkages serves as a driving force for regional development, constituting a prerequisite for forming dense urban areas or agglomerations within a region. These linkages also support regional integration (Guo et al., 2012). As China continues to promote regional integration, competition among cities gradually shifts towards cooperative competition, leading to closer and more complex socioeconomic linkages among cities. The Yangtze River Delta Region (YRDR), known for its integration and rapid growth, is a prime example of China’s intercity linkage network. Since identifying the “Yangtze River Delta integration” as a national development strategy in 2018, intercity cooperation and regional coordination have been strengthened.

This paper aims to explore the “near”Footnote 1 and “relevant” linkage between cities in the YRDR and provide scientific insights for achieving high-quality integrated development. The influence of various distance factors on intercity linkage asymmetry is examined, including geographic distance and attribute homogeneity distances.

The subsequent of this paper is structured as follows. In section 2, we conduct a literature review to identify the potential factors influencing intercity linkages. In section 3, we develop research hypotheses and an analytical framework and introduce the data. Section 4 presents the results, including an analysis of the asymmetry characteristics of intercity linkages and an explanation of the determinants of multivariate distances. Sections 5 and 6 comprise the discussion and conclusion.

Literature review

Spatial structural effects, such as spatial autocorrelation and space dependence, have been a subject of study by researchers since the 1970s (Tiefelsdorf, 2003). Griffith and Jones (1980) described how out-migrating flows from the same source are “enhanced or diminished in accordance with attributes displayed by neighboring origin locations”, and similarly, streams moving into the same destination are “enhanced or diminished in accordance with attributes displayed by neighboring destination locations”. Empirical and long-term studies have shown that intercity asymmetry linkages are associated with the geographical distance between cities. The closer the two cities are, the more likely they are to have symmetric linkages, following the principle of distance decay (Chen, 2015; Tobler, 2004). Tobler’s (1970) “first law of geography: everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things” has been interpreted from various perspectives (Miller, 2004; Sui, 2004). The key concepts in this law are “near” and “related”, highlighting the combination of geographic similarity (near) and attribute similarity (related) as the foundation basis for understanding spatial autocorrelation and the principles of urban interactive linkages.

The concept of “near” has traditionally been characterized by Euclidean distance in geographic space. However, with the continuous advancements in transportation technology and the development of integrated transportation systems, geographic distance is now understood as a combined concept incorporating time and monetary cost (Li et al., 2009). Time distance and cost distance have become widely employed in geography studies (Wang et al., 2015). The reduction in time and cost distances between cities has resulted in changes in the relative positioning of cities and the formation of metropolitan areas through the “co-location effect”, thereby strengthening intercity linkages (Jiao et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2021). The rapid development of railway transportation, airline networks, and road infrastructure, particularly highways, has expanded the service areas of hub cities and facilitated intercity connections (Shao et al., 2017). Conversely, cities that are not transportation hubs or located along significant routes face challenges in enhancing their accessibility and socioeconomic exchanges, leading to relatively greater intercity distances that impede intercity linkages (Wang et al., 2015).

Many scholars have expanded the concept of “related” beyond geographic spaces. Tobler (1970, 2004) introduced the principle that “equates similarity with distance” in multidimensional scales. Following this thinking, we consider “related” as another manifestation of “near” in attribute spaces. Thus, we utilize distance measures between observations in multi-attribute space to describe “related”. The distance measure also applies to socioeconomic attribute spaces, including administrative divisions, city classifications, industrial structures, and economic scales.

Administrative boundaries act as invisible barriers that impede the flow of factors and intercity linkages across regions. When cities are not located within the same provincial administrative region, institutional barriers may hinder the free movement of urban factors and amplify the potential “geographic distance” of intercity linkages. A recent study reveals that inter-regional provincial borders can result in market segmentation, effectively increasing the “distance” between cities by approximately 50% compared to their geographical distance (Zheng et al., 2022).

The spillover effect of cities is strongly influenced by city hierarchy, as higher-hierarchical cities possess greater radiation capacity and a more comprehensive range of linkage hinterlands (Sun et al., 2021). These higher-hierarchical cities assume more functions and attract others in search of goods and services, resulting in passive linkages from lower-hierarchical cities to higher-hierarchical cities. However, intercity linkages are weaker among lower-hierarchical cities due to the limited complementarity of urban development factors (Westlund, 2018).

Due to the agglomeration economy effects, larger cities attract development factors from smaller cities, thereby promoting factor flows and intercity linkages. It means that larger cities have a more vital ability to induce linkages. Additionally, larger cities have more significant spillover effects and can establish linkages with more cities (Sun et al., 2021).

The influence of industrial structure has dual aspects. On the one hand, cities with similar industrial structures can foster cooperation, exchange, and learning, thereby strengthening intercity. On the other hand, the transformation and upgrading of industrial structures have resulted in changes in labor demand for urban economic development. The initial stages of reform and opening saw a demand for cheap labor in labor-intensive industries, while new knowledge- and technology-intensive industries require highly skilled professionals. It has led to population flows between cities (Yao and Xu, 2008), further enhancing intercity linkages. Moreover, disparities in industrial structure also promote intercity linkages to some extent.

Hence, exploring factors influencing intercity asymmetric linkages can be simplified to evaluate the degree of proximity between cities in both geographic and multivariate space. The closer and smaller the distance between cities, the less pronounced the asymmetry in intercity linkages, and vice versa.

Research design

Conceptual and research hypothesis

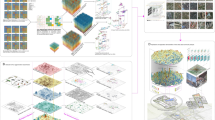

The linkage symmetry index measures the asymmetry of intercity linkages (Lin et al., 2021). A higher linkage symmetry index indicates more prominent asymmetry and pronounced unidirectional ties among cities. Conversely, a lower linkage symmetry index suggests weaker asymmetry, with cities being more mutually connected in both directions. To explore the influence of potential factors on intercity asymmetric linkages, the intercity differences of each factor were transformed into geographical and multivariate distances between cities (Fig. 1). Regression tests were conducted using MRQAP analysis. The dependent variable was the intercity asymmetric linkage index, while the independent variables were geographic distance and multivariate distances.

Multivariate distance is a composite measure that includes geographic distance, time distance, cost distance, institutional distance, hierarchical distance, economic distance, and structural distance. The combined spatial effect of multivariate distance affects intercity linkages, which are spatially expressed as degree of asymmetry. Intercity linkages arise from core and peripheral cities, i.e., big, and small cities.

Specifically, time distance represents the travel time between cities, and cost distance characterizes the travel cost between cities. The effect of provincial administrative boundaries is captured by institutional distance, which is determined by the number of straight-line connections between cities across provincial administrative regions. Similarly, hierarchical distance reflects the difference in city hierarchy, while economic distance represents the gap in economic scale between cities. Lastly, structural distance captures the disparity in industrial structure between cities. The design and expected effects of the independent variables can be observed in Table 1.

Study area and data

The “Outline of the Yangtze River Delta Regional Integrated Development Plan” encompasses Shanghai, as well as the provinces of Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui, within a geographical area of 358,000 km2 (Fig. 2). Shanghai is a municipality under the direct governance of the central government of China. Nanjing, Hangzhou, and Hefei are the provincial administrative centers for Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui provinces.

Location Based Service (LBS) pertains to acquiring users’ location information by network operators through external positioning methods. With the rapid proliferation of mobile devices (cell phones) and Wi-Fi, LBS generates a substantial amount of precise location data and plays an increasingly significant role in facilitating spatiotemporal interactions within geographic contexts. Tencent location service is one such application of LBS. Numerous mobile applications, such as mobile QQ, WeChat, Jingdong, and DDT, have integrated Tencent location services, widely utilized in people’s daily lives, leading to the emergence of Tencent location big data.

The SF migration is one of the largest short-term population migrations globally, and communication and location services are among the most fundamental needs for people during this migration process. Most migrating individuals are cell phone users. Hence, leveraging location services, the “Tencent Migration” big data offers a real-time, dynamic, comprehensive, and systematic depiction of users’ travel activity trajectories. It includes information such as time, longitude, latitude, and the frequency of use positioning, providing a comprehensive reflection of the population’s migration status. The “Tencent Migration” dataset encompasses prefecture-level and above cities in the YRDR (Lin et al., 2021). It includes the top ten cities with the highest daily population inflow and outflow and their corresponding migration volume. In total, there are 7543 migration records. To analyze the intra-day migration patterns of the population, a two-way matrix is constructed.

Methodology

Network core-periphery structure analysis

The analysis focuses on identifying the core position of city nodes in the population mobility network based on their proximity. Nodes in the core position hold a more significant role within the network (Al-Garadi et al., 2017). Core cities exhibit stronger connections between themselves and non-core (edge) cities, while non-core cities have fewer connections. The core-periphery structure analysis method assumes a K-shell value 1 for periphery nodes. All nodes and connected edges with a degree value one are removed initially. Subsequently, nodes and connected edges with degree values less than or equal to K (where K is an integer, K ≥ 2) are successively eliminated, gradually moving towards the network’s core (Das et al., 2018).

Link symmetry index

The link symmetry index is a measure used to assess the degree of symmetry or asymmetry in linkages between different entities within a network (Limtanakool et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2021). It quantifies the balance or imbalance in the connections between nodes or entities regarding their strength, direction, or other relevant attributes (Limtanakool et al., 2009). The link symmetry index provides valuable insights into the structural characteristics of a network and helps to understand the patterns of connectivity and interaction between its components.

Multivariate Regression Quadratic Assignment Procedure (MRQAP)

The quadratic assignment procedure (QAP) is a nonparametric test used to determine the significance of the association between two matrices that have complex correlations (Hubert and Schultz, 1976). QAP is not a statistical model but a standard regression model extension. It provides an unbiased test of association, considering potential correlations, and is widely utilized in social network analysis (Birke and Swann, 2010; Broekel et al., 2014; Choi et al., 2006; Gui et al., 2019). The QAP algorithm comprises two steps. Firstly, it involves conducting a standard ordinary least squares (OLS) regression between the values in the dependent variable matrix and the corresponding values in the independent variable matrix. Secondly, the algorithm randomly permutes the rows and columns of the dependent variable matrix. It repeats this process hundreds of times to re-estimate the coefficients and standard errors derived from the OLS regression. By randomizing the data through row and column permutations, the QAP algorithm addresses potential multicollinearity issues between the dependent and independent variables (Xu and Cheng, 2016). The UCINET software can be used to analyze this model.

The original QAP was initially developed for binary correlations (Mantel, 1967). Later, Krackhardt (1988) and Mizruchi (1993) introduced the Multivariate Regression Quadratic Assignment Procedure (MRQAP). Martin (1999) extended MRQAP to accommodate arbitrary outcome distributions by applying the QAP test to the coefficients of generalized linear models. MRQAP offers several advantages worth considering (Cranmer et al., 2017). The method is easily accessible, well-implemented, and straightforward, as MRQAP results can be interpreted similarly to any other regression analysis. MRQAP can also yield reliable results, particularly in cases where estimates are challenging to obtain using alternative methods, such as dense network relationships. Lastly, MRQAP does not necessitate a theoretical model to handle network dependencies.

In this study, we record the asymmetric linkage index between 41 cities in the YRDR as a 41 × 41 matrix, where each origin city and destination city form a binary relationship. The multivariate distances between the origin and destination cities are utilized as independent variables. All independent variables are represented as binary pairs and are organized in a matrix format within the MRQAP model. The following equation can represent the model,

where, Aij represents the linkage asymmetry index between city i and j; GDij denotes the physical geographical distance between cities i and j; TDij represents the time distance; CDij is the cost distance; IDij represents the institutional distance; HDij is the hierarchical distance; EDij signifies the economic distance; and SDij represents the structural distance; β0 is the constant term, βi represents the coefficients to be estimated, and εij is the error term.

Results

Asymmetry of intercity linkages

The core-peripheral structure of the network identifies Shanghai, Suzhou, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Hefei, Wuxi, Ningbo, Jiaxing, and Changzhou as the core cities in the YRDR regional network. These cities dominate in shaping the basic pattern of the YRDR population linkage network. By analyzing the asymmetry of the linkage between the nine core cities and their connected non-core cities, it is possible to classify them into five degrees of asymmetry, ranging from low to high with A, B, C, D, E (Fig. 3).

Asymmetric linkages at the A and B degrees primarily occur within short geographic distances, typically between neighboring cities. It includes inter-provincial and intra-provincial intercity linkages, as cities have both linkages. Asymmetry at the C degree is observed in short distances between neighboring cities and longer geographic distances between non-neighboring cities. However, it is essential to note that intra-provincial linkages dominate in both scenarios. Asymmetric linkages at the D and E degrees are predominantly found over long geographical distances. Intra-provincial linkages with such asymmetry are relatively rare, whereas inter-provincial linkages are present in all nine central cities.

Multivariate distance factor analysis

According to the MRQAP matrix regression analysis (Table 2), the model fitted based on seven distance variables explains 85.70% of the intercity asymmetric linkage network distribution variance. This high percentage indicates a strong level of confidence in the fitted model.

The influence of geographic distance (0.961) is the most decisive factor in the asymmetry of intercity linkages. The influence coefficient of geographic distance suggests that as the geographic distance between cities increases, the asymmetry of intercity linkages becomes more significant. This finding reflects the presence of spatial autocorrelation and spatial dependence in symmetric intercity linkages. This observation aligns with previous studies that have demonstrated the significance of spatial autocorrelation in various intercity flows, such as commodity flows, capital flows, and migration flows (Chun and Griffith, 2011; Chun et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2022). The findings presented here contribute new empirical evidence to this body of research. Additionally, Tobler’s widely recognized first law of geography is well suited to explain the spatial context of the social mobility network examined in this study.

In addition to geographic distance, the degree of influence on the asymmetry of intercity linkages, in descending order, is as follows: cost distance, economic distance, structural distance, time distance, institutional distance, and hierarchical distance.

Time and cost distance positively influence the asymmetry of intercity linkages, although the influence of time distance (0.149) is minor than cost distance (0.219). The well-developed high-speed rail and road transportation networks in the YRDR improve the accessibility of cities, reducing the time distance between them and significantly enhancing intercity linkages along the route. As a result, the influence of time distance on intercity asymmetry linkages is relatively diminished. However, it is essential to note that the contraction of time and space comes at the expense of increased economic costs. The economic cost gap between intercity links widens, and thus, cost distance plays a significant role in the asymmetry of intercity linkages.

The impact of economic distance (0.187) suggests that the greater the disparity in economic volume between cities, the more prominent the asymmetry of intercity linkages. The A-degree asymmetry is more likely to occur between cities with minimal differences in socioeconomic levels. In essence, cities establish linkages with others of similar size and development levels, fostering healthy competition and facilitating win-win cooperation.

Structural distance demonstrates a positive effect (0.151), indicating that the greater the disparity in industrial structure between cities, the higher the degree of asymmetry in intercity linkages. Conversely, when two cities have similar industrial structures, they are likelier to have similar stages of industrial development and planning concepts. This similarity allows for sharing resources and experiences among enterprises and individuals, fostering conditions and willingness for cooperation. Consequently, cities with similar industrial structures maintain closer and more frequent contact, resulting in lower asymmetry in their intercity linkages.

The impact of institutional distance (0.004) and hierarchical distance (0.003) is minimal, suggesting that administrative boundaries and disparities in city hierarchies are limited in influencing the degree of asymmetry in intercity linkages. Gaps in the degree of asymmetry of intercity linkages are slight. To some extent, this finding reflects the progress made in the integrated construction of the YRDR and the coordinated development of cities.

The thresholds for controlling geographical distances for intercity linkages are determined by the average geographical distances for the five degrees of asymmetry intercity linkages. They are classified into five categories: I, II, III, IV, and V. (Table 3). This classification aims to uncover the specific “distances” that influence the varying degrees of intercity asymmetric linkages, with geographical distances as the controlling factor.

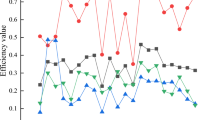

The analysis results depicted in Fig. 4 reveal significant variations in attribute distance factors that influence intercity asymmetric linkages across different geographical distances. In categories I and II, time and cost distance have the most pronounced influence, indicating their significance in linkages within short geographic distances. Time and cost distance reflect the accessibility of intercity connections, implying that convenient transportation links facilitate the A-degree asymmetric linkages between cities’ proximity. This finding aligns with the “small world effect” concept and underscores the importance of robust transportation infrastructure in metropolitan areas. While the influence of each attribute distance in category I is relatively similar, the disparity in their influence increases in category II. It suggests that as geographic distance increases, the impact of attribute distance becomes more complex, highlighting the presence of geospatial autocorrelation and dependence on the force of attribute distance.

In category III, there is a significant increase in the influence of time and economic distance, while the influence of cost and hierarchical distance decreases. The drastic inverse changes in the influence of time and cost distance indicate that both factors are susceptible to the role of intercity asymmetric linkages at medium geographic distances. It suggests that the medium distance range serves as a crucial threshold for the spatiotemporal contraction effect, where the advantage of proximity in terms of travel time and cost in intercity linkages tends to weaken. The substantial increase in the influence of economic distance (0.844) reveals a pronounced economic distance decay effect on the symmetry of intercity linkages. It suggests that intercity linkages evolve into a spillover effect, attracting large cities toward smaller ones.

In category IV, the influence of time and economic distance diminishes significantly, while other attribute distances exhibit a smoother performance. Among all attribute distances, economic distance has the most significant influence (0.295), followed by hierarchical distance (0.145). It highlights the substantial impact of disparities in city economic scale and hierarchical differences on the asymmetry of intercity linkages over long geographic distances. It further reveals that intercity linkages are influenced by the attraction and spillover effects of large cities with significant economic scale and high hierarchical status on smaller peripheral cities.

In category V, the influence of time distance and economic distance continues to decline, while conversely, the influence of hierarchical distance, institutional distance, and cost distance increases. Notably, hierarchical and institutional distance influence, at 0.491 and 0.320, respectively, reach the highest values among all distance classifications. It indicates that the E-degree asymmetry of intercity linkages results from the combined effect of administrative boundary blockage and disparities in city hierarchy.

To conclude, the influence of each attribute distance on the asymmetry of intercity linkages becomes complex as geographic distances vary, particularly after surpassing a certain threshold.

Discussion

This paper presents a theoretical analysis of the relationship between intercity linkages and multivariate distance factors, focusing on the YRDR. The YRDR is renowned for its developed economy, dense population, and well-established intercity transportation system, making it an ideal subject for studying intercity linkages (Lin et al., 2023). This article contributes to making it an ideal subject for studying intercity linkages. Firstly, we aim to empirically validate the concept of “death by distance” from multiple attribute factors. While previous studies (Bailey et al., 2020; Stephens and Poorthuis, 2015; Wang et al., 2019) have acknowledged the conditions under which the “death of distance” proposition holds, we argue that with the advent of ICT and the socioeconomic proximity between cities, distance is no longer solely a geographical measure, but also encompasses socioeconomic dimensions. By examining various dimensions of distance, we bridge this gap in the literature and provide a more comprehensive perspective on the validity of the “death of distance” in the context of intercity linkages.

Our study empirically focuses on the YRDR in China, one of the most economically dynamic and influential urban agglomerations that cannot be overlooked. By bridging the policy discourse of regional integration in China with the policy discourse of globalization in the West, our study contributes to the empirical literature on intercity linkages. It challenges the notion of the “death of distance” prevalent in Western academia. Furthermore, our empirical research validates the continued relevance of geographic distance in intercity linkages despite advancements in transportation and communication technologies. The quantitative analysis results affirm the significance of physical spatial distances in population mobility and urban interactions, countering the idea of the “death of distance” (Sarkar et al., 2019; Stephens and Poorthuis, 2015). These findings provide valuable insights into understanding intercity connections and the role of distance in shaping them.

This study significantly contributes to the existing literature by extending beyond the specific context of YRDR. This study establishes a framework that can be applied to other regional and urban settings by investigating the relationship between geographic distance, attribute distance, and intercity linkages. It paves the way for further exploration of distance-related factors and their influence on urban interactions, fostering a more profound comprehension of regional integration and urban development. In conclusion, the findings of this study offer valuable insights and serve as a foundation for future research in this field, ultimately enhancing our understanding of urban dynamics and spatial relationships.

Considering the multidimensional and comprehensive evolution of urban linkages, our empirical study surpasses the conventional notion of spatial distance. In our analysis, we incorporate spatial distance and attribute distances from factors such as time, transportation, industry, institutions, scale, and structure. This approach carries significant policy implications for regional development in the era of information technology advancement. The impacts and constraints of distance extend beyond physical spatial intervals. Our study uncovers a correlation between asymmetric connections and geographic distance, which becomes more prominent as the distance between cities increases. This finding suggests that intercity connections are influenced by geographic distance and attribute proximity, gradually weakening as geographic distance grows. By shedding light on this nuanced understanding, our study contributes empirical evidence to the existing literature on the intricate relationship between distance and intercity linkages. It underscores the importance of considering diverse attribute distances and their interplay in comprehending the asymmetry of intercity linkages.

Conclusion

Drawing inspiration from Tobler’s first law of geography and the concept of distance decay, this paper utilizes big data on migration in the YRDR to analyze the symmetrical characteristics of intercity links spatially. It examines various multivariate distance factors associated with geospatial and attribute proximity to investigate the validity of the “death of distance” hypothesis. In today’s era of rapid advancements in transportation and communication technologies, intercity linkages have become increasingly diverse, and distances are no longer limited to physical spatial distances alone. They now encompass attribute distances that include functional, economic, institutional, and structural differences. The analytical framework presented in this paper offers an alternative perspective for understanding intercity linkages and contributes to the ongoing academic debate regarding the continued relevance of distance.

We utilize the YRDR as a case study for our empirical analysis. The Chinese government’s efforts to promote regional integration and develop a more coordinated and efficient economic system and connectivity make the YRDR an ideal subject for our study. Using migrating data to analyze the correlation between intercity links and multivariate distances, we establish an intercity linkage matrix and association network.

Firstly, our empirical findings support the “death of distance” concept discussed in existing literature. However, we expand on “distance” by developing an analytical model that examines the correlation between intercity linkages and various factors, including multivariate distances. Our MRQAP regression analysis results reveal that geographic distance remains the most decisive factor in determining the asymmetry of intercity linkages. This empirical result challenges the commonly held assumption that the significance of distance is diminishing over time, aligning with previous literature that disputes the idea of the “death of distance”. It underscores the enduring importance of geographic proximity. Additionally, the effects of distance on the asymmetry of intercity linkages are complex and influenced by factors such as time, cost, economic, institutional, scale, and structural distance, particularly beyond a certain threshold of geographic proximity. Our findings suggest that despite advancements in transportation and communication technologies, cities should focus on developing effective policies, enhancing transportation infrastructure, and fostering regional connectivity to facilitate collaborative and balanced development among cities.

Secondly, our study contributes to the understanding of how to foster intercity linkages in the new technological era, focusing on policy and management perspectives. Policy design should prioritize enhancing coordination and cooperation among city governments, establishing a unified policy framework and planning mechanism. It will facilitate synergistic economic, environmental, and social development among cities, reducing the impact of geographical and attribute distance and enabling integrated growth. The government can bolster transportation and logistics network infrastructure investment regarding regional management and development. It will improve transportation accessibility and logistics efficiency between cities. Additionally, promoting industrial complementarity and cooperation among cities can generate a cluster effect within industrial and value chains. It can be achieved through science and technology innovation platforms, inter-firm cooperation, and other means that foster economic development and collaboration among cities. By doing so, the constraints imposed by geographical distance can be diminished, promoting intercity mobility and connectivity.

It is important to note that this study has several limitations, including potential group bias in Tencent’s migration data and the absence of socioeconomic attributes of mobile individuals (Bircan and Korkmaz, 2021). Therefore, exercising greater control over demographic group attributes, such as accounting for distances due to dialectal cultural differences, is necessary. Future research should aim to develop a consistent understanding of the impact of urban cultural differences, including linguistic similarities and dialect areas (Li et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2018). The complex linguistic structure of the YRDR, with its various dialect areas and patches, should be considered when examining the asymmetry of intercity connections. Furthermore, future research should investigate whether cultural distance affects these linkages, considering cultural exchange and transmission and the promotion of Mandarin in the region.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the author on reasonable request.

Notes

“Near” is a term derived from Tobler’s (1970) first law, while the term “proximity” is commonly used in the fields of urban studies and economic geography.

References

Al-Garadi MA, Varathan KD, Ravana SD (2017) Identifying influential spreaders in online social networks using interaction weighted k-core decomposition method. Physica A 468:278–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2016.11.002

Andris C (2016) Integrating social network data into Gisystems. Int J Geogr Inf Sci 30(10):2009–2031. https://doi.org/10.1080/13658816.2016.1153103

Bailey M, Farrell P, Kuchler T, et al. (2020) Social connectedness in urban areas. J Urban Ecom 118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2020.103264

Batty M (2013) The new science of cities. MIT Press, MA

Berry BJL (1964) Cities as systems within systems of cities. Pap Reg Sci Assoc 13(1):146–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01942566

Bircan T, Korkmaz EE (2021) Big data for whose sake? Governing migration through artificial intelligence. Hum Soc Sci Commun 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00910-x

Birke D, Swann GMP (2010) Network effects, network structure and consumer interaction in mobile telecommunications in Europe and Asia. J Econ Behav Organ 76(2):153–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2010.06.005

Brenner N (1998) Global cities, glocal states: Global city formation and state territorial restructuring in contemporary Europe. Rev Int Polit Econ 5(1):1–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/096922998347633

Broekel T, Balland PA, Burger M et al. (2014) Modeling knowledge networks in economic geography: a discussion of four methods. Ann Reg Sci 53(2):423–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-014-0616-2

Castells M (1992) The space of flows: a theory space in the informational society. Princeton University, Princeton

Castells M (1996) The rise of the network society. Oxford Blackwell Publishers, Cambridge

Castells M (1999) Grass-rooting the space of flows. Urban Geogr 20(4):294–302. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.20.4.294

Chen Y (2015) The distance-decay function of geographical gravity model: power law or exponential law? Chaos Soliton Fract 77:174–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2015.05.022

Choi JH, Barnett GA, Chon BS (2006) Comparing world city networks: a network analysis of internet backbone and air transport intercity linkages. Glob Netw 6(1):81–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2006.00134.x

Chun Y, Griffith DA (2011) Modeling network autocorrelation in space-time migration flow data: an eigenvector spatial filtering approach. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 101(3):523–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2011.561070

Chun Y, Kim H, Kim C (2012) Modeling interregional commodity flows with incorporating network autocorrelation in spatial interaction models: an application of the US interstate commodity flows. Comput Environ Urban 36(6):583–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2012.04.002

Cranmer SJ, Leifeld P, McClurg SD et al. (2017) Navigating the range of statistical tools for inferential network analysis. Am J Polit Sci 61(1):237–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12263

Dai T, Jin F, Wang J (2005) Spatial interaction and network structure evolvement of cities in terms of China’s railway passenger flow in the 1990s. Prog Hum Geog 24(2):80–89. https://doi.org/10.11820/dlkxjz.2005.02.009

Das K, Samanta S, Pal M (2018) Study on centrality measures in social networks: a survey. Soc Netw Anal Min 8(13):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-018-0493-2

Goldenberg J, Levy M (2009) Distance is not dead: social interaction and geographical distance in the internet era. ACM SIGCAS Comp Soc, abs/0906.3202. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.0906.3202

Griffith DA, Jones KG (1980) Explorations into the relationship between spatial structure and spatial interaction. Environ Plann A 12(2):187–201. https://doi.org/10.1068/a120187

Gui QC, Liu C, Du DB (2019) Globalization of science and international scientific collaboration: a network perspective. Geoforum 105:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.06.017

Guo J, Han Z, Geng Y (2012) The regional variation analysis of urban spatial relationship in China. Area Res Dev 31(1):40–44. https://www.en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-DYYY201201008.htm

Han S, Tsou MH, Clarke KC (2018) Revisiting the death of geography in the era of big data: the friction of distance in cyberspace and real space. Int J Digit Earth 11(5):451–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538947.2017.1330366

Hubert L, Schultz J (1976) Quadratic assignment as a general data analysis strategy. Br J Math Stat Psy 29(2):190–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1976.tb00714.x

Hudson R (2020) Place and uneven development. In The Routledge Handbook of Place. Routledge, London

Jeon JS (2020) Moving away from opportunity? Social networks and access to social services. Urban Stud 57(8):1696–1713. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019844197

Jiao J, Wang J, Jin F (2017) Impacts of high-speed rail lines on the city network in China. J Transp Geogr 60:257–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.03.010

Jin J, Meng Y, Zhang L (2018) Cross-dialect migration, self-selection, and income. Stat Res 35(8):94–103. https://doi.org/10.19343/j.cnki.11-1302/c.2018.08.009

Krackhardt D (1988) Predicting with networks: nonparametric multiple regression analysis of dyadic data. Soc Netw 10(4):359–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8733(88)90004-4

Lefebvre H (1991) The production of space. (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell

Leitner H, Sheppard E (2002) “The city is dead, long live the net”: harnessing European interurban networks for a neoliberal agenda. Antipode 34(3):495–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00252

Li J, Luo H, Wang X (2009) Application of reconstruction of gravitation model in the space reciprocity between the city zone and the suburb. World Reg Stud 18(2):76–84. CNKI:SUN:SJDJ.0.2009-02-010

Li Y, Liu H, Tang Q et al. (2015) Spatial-temporal patterns of China’s interprovincial migration during 1985- 2010. J Geogr Sci 24(6):1135–1148. CNKI:SUN:DLYJ.0.2015-06-013

Limtanakool N, Dijst M, Schwanen T (2007) A theoretical framework and methodology for characterising national urban systems on the basis of flows of people: Empirical evidence for France and Germany.Urban Stud 44(11):2123–2145. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701808832

Limtanakool N, Schwanen T, Dijst M (2009) Developments in the Dutch urban system on the basis of flows. Reg Stud 43(2):179–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701808832

Lin JP, Wu KM, Yang S et al. (2021) The asymmetric pattern of population mobility during the Spring Festival in the Yangtze River Delta based on complex network analysis: an empirical analysis of “Tencent Migration” big data. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf 10(9):582, https://www.mdpi.com/2220-9964/10/9/582

Lin JP, Yang S, Liu YH, et al. (2023) The urban population agglomeration capacity and its impact on economic efficiency in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration. Environ Dev Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03242-9

Liu T, Qi YJ, Cao GZ et al. (2015) Spatial patterns, driving forces, and urbanization effects of China’s internal migration: county-level analysis based on the 2000 and 2010 censuses. J Geogr Sci 25(2):236–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-015-1165-z

Mantel N (1967) The detection of disease clustering and a generalized regression approach. Cancer Res 27(2):209–220. http://www.stat.ucla.edu/~nchristo/statistics_c173_c273/mantel_nathan_paper.pdf

Martin JL (1999) A general permutation-based QAP analysis approach for dyadic data from multiple groups. Connections 22(2):50–60

Massey DB (1994) Space, place, and gender. University of Minnesota Press, UK

Miller HJ (2004) Tobler’s first law and spatial analysis. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 94(2):284–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2004.09402005.x

Mizruchi MS (1993) Cohesion, equivalence, and similarity of behavior: a theoretical and empirical assessment. Soc Netw 15(3):275–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8733(93)90009-A

Paul S (2009) Spaces of global capitalism: towards a theory of uneven geographical development. Geogr Res-Aust 47(3):343–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2008.00198_1.x

Pflieger G, Rozenblat C (2010) Urban networks and network theory: the city as the connector of multiple networks. Urban Stud 47(13):2723–2735. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098010377368

Raffnsøe S (2003) The rise of the network society: an outline of the dissertation coexistence without common sense MPP Working Paper, Issue. https://research.cbs.dk/en/publications/the-rise-of-the-network-society-an-outline-of-the-dissertation-ic

Sarkar D, Andris C, Chapman CA et al. (2019) Metrics for characterizing network structure and node importance in Spatial Social Networks. Int J Geogr Inf Sci 33(5):1017–1039. https://doi.org/10.1080/13658816.2019.1567736

Shao S, Tian Z, Yang L (2017) High-speed rail and urban service industry agglomeration: evidence from China’s Yangtze River Delta Region. J Transp Geogr 64:174–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.08.019

Shaw SL, Tsou MH, Ye XY (2016) Editorial: Human dynamics in the mobile and big data era. Int J Geogr Inf Sci 30(9):1687–1693. https://doi.org/10.1080/13658816.2016.1164317

Sheppard E (2002) The spaces and times of globalization: place, scale, networks, and positionality. Econ Geogr 78(3):307–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2002.tb00189.x

Smith N (2008) Uneven development: nature, capital, and the production of space (Third edition ed). University of Georgia Press, Athens

Soja EW (2012) Regional urbanization and the end of the metropolis era. Wiley-Blackwell, Oakland, CA

Stephens M, Poorthuis A (2015) Follow thy neighbor: connecting the social and the spatial networks on Twitter. Comput Environ Urban 53:87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2014.07.002

Sui DZ (2004) Tobler’s first law of geography: a big idea for a small world? Ann Assoc Am Geogr 94(2):269–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2004.09402003.x

Sun B, Lin J, Yin C (2021) How does commute duration affect subjective well-being? A case study of Chinese cities. Transportation 48(2):885–908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-020-10082-3

Sun B, Zhang T, Wang Y, et al. (2021). Are mega-cities wrecking urban hierarchies? A cross-national study on the evolution of city-size distribution. Cities 108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102999

Taylor PJ, Derudder B (2015) World city network: a global urban analysis. Routledge, London

Taylor PJ, Hoyler M, Verbruggen R (2010) External urban relational process: introducing central flow theory to complement central place theory. Urban Stud 47(13):2803–2818. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098010377367

Tiefelsdorf M (2003) Misspecifications in interaction model distance decay relations: a spatial structure effect. J Geogr Syst 5(1):25–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s101090300102

Tobler W (1970) A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region. Econ Geogr 46:234–240. https://doi.org/10.2307/143141

Tobler W (2004) On the first law of geography: a reply. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 94(2):304–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2004.09402009.x

Wang F, Wei XJ, Liu J et al. (2019) Impact of high-speed rail on population mobility and urbanization: a case study on Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration, China. Transp Res Part a-Policy Pract 127:99–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2019.06.018

Wang J, Jiao JJ, Du C et al. (2015) Competition of spatial service hinterlands between high-speed rail and air transport in China: present and future trends. J Geogr Sci 25(9):1137–1152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-015-1224-5

Wang Z, Ye X, Lee J et al. (2018) A spatial econometric modeling of online social interactions using microblogs. Comput Environ Urban 70:53–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2018.02.001

Westlund H (2018) Urban-rural relations in the post-urban world. In H Tigran & W Hans (Eds.), In the post-urban world: emergent transformation of cities and regions in the innovative global economy (pp 70–81). Routledge, London

Wu KM, Chen YJ, Zhang HO et al. (2023) ICTs capability and strategic emerging technologies: evidence from Pearl River Delta. Appl Geogr 157:103019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2023.103019

Wu KM, Ye Y, Wang XY et al. (2023) New infrastructure-lead development and green-technologies: evidence from the Pearl River Delta, China. Sustain Cities Soc 99:104864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2023.104864

Wu KM, Wang Y, Zhang HO et al. (2022) The pattern, evolution, and mechanism of venture capital flows in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, China. J Geogr Sci 32(10):2085–2104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-022-2038-x

Xiao, Z, Bi, M, Zhong, Y, et al. (2021). Study on the evolution of the Source-Flow-Sink pattern of China’s Chunyun population migration network: evidence from Tencent big data. Urban Sci, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci5030066

Xu H, Cheng L (2016) The QAP weighted network analysis method and its application in international services trade. Physica A 448:91–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2015.12.094

Yao H, Xu X (2008) Progress of research on migration in Western countries. World Reg Stud 17(1):154–166. CNKI:SUN:SJDJ.0.2008-01-022

Zhao M, Wu K, Liu X et al. (2015) A novel method for approximating intercity networks: an empirical comparison for validating the city networks in two Chinese city-regions. J Geogr Sci 25(3):337–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-015-1172-0

Zheng YL, Lu M, Li JW (2022) Internal circulation in China: analyzing market segmentation and integration using big data for truck traffic flow. Econ Model 115:105975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2022.105975

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42101182, 42130712), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2023A1515012399, 2020A1515110768), Technology plan of Guangzhou (No. 202201010319), Guangzhou Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (No. 2023GZYB62).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: JL and KW; methodology: JL; writing—original draft preparation: JL; writing—review and editing: JL and KW; funding acquisition: KW.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The population movement data during the Chinese Spring Festival period used in this study were obtained from the Tencent Migration website, and the dataset was released to the public and did not contain personally identifiable information of the participants. The statistics used in this study were obtained from the Urban Statistical Yearbook issued by the Chinese government. The data used in the study follow the ethical principles of research established by the Chinese government.

Informed consent

The population mobility data used in the study process contains only locational data on the movement of population locations, no identifying information is collected, and there are no scientific or technical ethical issues.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, J., Wu, K. Intercity asymmetrical linkages influenced by Spring Festival migration and its multivariate distance determinants: a case study of the Yangtze River Delta Region in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 946 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02456-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02456-6