Abstract

Energy enterprises are an important basis for ensuring national energy security and economic development, and their social responsibility is closely related to addressing environmental concerns such as over-exploitation of resources and excessive discharge of pollution. The casual effects of management compensation incentives on corporate social & environmental responsibility are explored based on the panel data of Chinese energy enterprises from 2010 to 2021 using the instrumental variable estimation method. The results indicate that management salary incentives can significantly promote the implementation of corporate social responsibility and environmental responsibility, while the proportion of management shareholding will reduce corporate social responsibility (CSR) and environmental responsibility (CER) activities. In addition, there are obvious industry differences and corporate ownership differences in the effects of management compensation incentives on CSR and CER. The negative impact of equity incentives on CSR and CER is even more pronounced in the electricity and environmental industry, and salary incentives have a greater positive effect on CSR for state-owned enterprises. The study shows that enterprises should focus on the salary incentive of managers and appropriately reduce their shareholding. The government should pay attention to the development of state-owned energy enterprises, and limit the shareholding ratio of management through policies and other incentive systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The energy industry provides an important material basis for economic and social development; however, with the rapid development of modern society and the economy, more attention has been paid to the problem of high pollution and high emissions caused by traditional energy utilization (Meng and Huang 2018; Strusnik et al. 2020; Huang et al. 2020b), especially in China (Huang et al. 2020a; Yu et al. 2023). The realization of China’s carbon peak and carbon neutralization goals requires the unremitting efforts of China’s energy industry (Jia and Lin 2021). Energy enterprises assume important social responsibility in ensuring national energy security, solving environmental problems, coping with climate change, and so on.

Global CO2 emissions have increased significantly in recent years. China has led the expansion of the global energy market, accounting for more than three-quarters of the net increase in global energy consumption (Du et al. 2021), making it the largest energy driver to dateFootnote 1. Although the global primary energy consumption decreased by 4.5% in 2020 due to the severe situation around the COVID-19 pandemic, China’s primary energy consumption still maintained the largest growth rate of 2.1%, and became the only country with an increase in oil consumption.Footnote 2 According to the Global Energy Review: CO2 emissions report of 2021 released by the International Energy Agency (IEA), per capita CO2 emission in China has reached 8.4 tonnes, higher than the average of 8.2 tonnes in developed countries. The development of China’s energy industry has attracted much attention from scholars. Previous discussions on the energy industry focus on many areas, such as overcapacity (Du et al. 2020), government subsidies (Luo et al. 2021), corporate governance (Shi 2019), resource allocation (Guo et al. 2021), corporate risk (Wei et al. 2019), and so on. The general notion holds that the production and operation activities of energy enterprises have negative externalities, especially greenhouse gas and other harmful substances produced by fossil energy consumption (Ahmed et al. 2023), significantly affecting the sustainable development of the natural environment and human society. Consequently, energy companies face greater pressure and social responsibility than other industries (Latapí Agudelo et al. 2020).

The idea of corporate social responsibility (CSR) originated from the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, emphasizing the contribution to the environment (Chen et al. 2019), consumers, and society in the production process. CSR is defined as the company’s interests and social interests beyond the legal requirements (McWilliams and Siegel 2001), which refers to the actions taken by enterprises to promote social welfare, including many employee-friendly, environment-friendly, and investor-friendly behaviors (Becchetti et al. 2018).

Currently, the international reliable CSR database is MSCI ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) Ratings, which encompasses the enterprise data of each country, covering environmental, social, stakeholder, and corporate governance aspects. In China, the social responsibility information disclosed by listed companies is gradually being improved. The authoritative evaluation system mainly includes Rankins CSR Ratings (RKS) and the Hexun CSR database. RKS mainly assesses CSR from the Macrocosm (M), content (C), technique (T), and industry (I) aspects and establishes the RKS ESG rating system concerning international standards. Similarly, Hexun’s social responsibility measurement system evaluates listed companies from five indicators: shareholder responsibility; employee responsibility; supplier, customer, and consumer rights and interests’ responsibility; environmental responsibility; and social responsibility. According to the Research Report on Corporate Social Responsibility of China (Li et al. 2019), the social responsibility of Chinese state-owned enterprises is ahead of that of private enterprises and foreign-funded enterprises, and the social responsibility score of the power industry is much higher than that of other industries.

The existing literature on CSR mainly focuses on two aspects: influencing factors and effects. On the one hand, those factors influencing CSR include multiple dimensions. Externally, the political, economic, and cultural background of the region where the enterprise is located are all factors that affect CSR activities (Tilt 2016). For example, the social anti-corruption campaign can significantly improve the performance of CSR (Kong et al. 2021). Internally, companies with more effective risk management are more willing to participate in CSR behavior (Kuo et al. 2021); ethical leadership has a positive effect on CSR (Nguyen et al. 2021); strategic planning and corporate culture are also important factors affecting CSR (Kalyar et al. 2013); green financial help may have gradual negative impacts on environmental and social responsibility (Sinha et al. 2021). Moreover, CSR activities also exert a variety of influences on the development of enterprises. Research shows that CSR significantly improves corporate performance (Javeed and Lefen 2019), reduces the cost of debt (Yeh et al. 2020), and promotes corporate innovation (Javeed et al. 2021). Participation in CSR activities can also help to a good corporate reputation (Han and Lee 2021) and enhance customer trust (Islam et al. 2021), thereby gaining a competitive advantage (Turyakira et al. 2014), which is conducive to the long-term development of enterprises. In addition, social responsibility activities is found to affect stock prices. Huang and Liu (2021) found that companies engaged in more CSR activities faced less risk of stock price crashes under the effect of COVID-19.

Given the important position of the energy industry in the economic system, improving the social responsibility of energy enterprises and maintaining a relative balance between providing energy for economic development and environmental protection is vital. In existing studies, managerial characteristics, as a key factor in enterprise development, has been proven to affect CSR significantly. Studies found that the marital status of the CEO (Cronqvist and Yu 2017; Hegde and Mishra 2019), excessive self-confidence (Zribi and Boufateh 2020), internal debt (Kim et al. 2020), board structure (Bolourian et al. 2021), and gender ratio (Wang et al. 2021) all influence CSR activities. Besides these managerial characteristics, the relationship between executive compensation and CSR/CER (Corporate Environmental Responsibility) has also received extensive study.

Zou et al. (2015) found that top executives’ cash payment positively affects corporate environmental performance, whereas equity ownership has a negative one. Similarly, the study of Shaer et al. (2023) also revealed that CEOs (Chief Executive Officers) are motivated to improve CER when they receive compensation for engagement in environmental activities. Jiang et al. (2021) examined the executives’ compensation restriction imposed by the government on CSR, and the results indicate that CSR performance decreases with increases in the pay restriction. The relationship between executive compensation and CSR may also be an inverted U-shaped relationship, and the threshold level is 18.7 percent in the level of executive compensation (Pareek and Sahu 2024). Contrary to these studies, another line of study aims to explore CSR’s impact on executive compensation. CSR has a positive effect on the financial performance (Jahmane and Gaies 2020). Good CSR performance increases management compensation by improving corporate profitability (Ho et al. 2022), the same effect was also found for environmental performance (Berrone and Gomez-Mejia 2009). However, some studies provide the opposite results. The study of Jian and Lee (2015) pointed out that CEO total compensation is negatively associated with CSR investment. In the same way, the study of Cai et al. (2011) showed that CSR negatively affects both CEOs’ total compensation and cash compensation. According to the literature above, two-way causality between CSR and management compensation may exist. This is partly confirmed by the study of Kao et al. (2018), which shows the presence of a bidirectional relationship between CSR and firm performance.

For China, designing an optimal compensation structure for management in the energy industry to act morally and engage more in social responsibility is of great importance for environmental protection and sustainable development. Therefore, this paper falls in the first category given above, exploring management compensation’s impact on CSR. Considering the potential two-way causality, the main aim of this study is to identify the causal effects of management compensation on CSR using robust methodologies.

This study mainly answers the following questions. 1) What are the causal effects of management compensation incentives on corporate social responsibility and environmental responsibility? 2) What is the difference between salary incentives and equity incentives on corporate social responsibility and environmental responsibility? 3) What is the heterogeneity of different types of sub-industries, different types of enterprise ownership, and different regions? 4) What are the implications of this study for energy enterprises to undertake CSR & CER?

The contributions of this paper are as follows: 1) Unlike most previous studies, which mainly investigate the relationship between CSR and executive pay, this article tries to identify the causal effect of management compensation incentives on CSR using the instrumental variable estimation method on enterprise level. Specifically, we constructed corresponding instrumental variables for salary and equity incentives. This study’s method can effectively solve the endogeneity bias due to omitted variables and reverse causality. 2) Considering that there may be greater externalities in the production process of energy enterprises, the issue of CSR of energy enterprises is particularly important. Therefore, the main object of this study is the CSR of the energy enterprises in China, which is the largest greenhouse gas emitter worldwide.

The rest of the article is structured as follows: the second part presents the theoretical basis and hypothesis underpinning the research, the third part contains an introduction to the data and models, the fourth part demonstrates a report and analysis of empirical regression results, and the fifth part puts the conclusion.

Hypothesis and theoretical basis

Management compensation is one of the most controversial features of corporate governance (Correa and Lel 2016). In China, the management compensation of listed companies is often a combination of monetary salary and shareholding ratio (Liu et al. 2014), and its incentive effect is affected by the pay gap (Xu et al. 2016) and future compensation structure (Tang 2016). In 2016, the implementation of the “Equity Incentive Management Measures for Listed Companies” standardized the equity incentive behavior of listed companies and endowed listed companies with a certain autonomy. Other research found significant differences in the effects of salary and equity compensation on corporate strategy (Chan and Ma 2017). Salary compensation is a fixed material reward for managers to ensure that their day-to-day needs are met (Zhou et al. 2021), while equity incentive increases the variation range of the present value of compensation and links the management interests with the shareholder interests and corporate performance (Brüggen and Zehnder 2014). Therefore, in the present analysis, we divide the management compensation incentives into two parts: salary and equity incentives. And we evaluates their different effects on CSR performance and proposes two hypotheses.

Previous research shows that the compensation of enterprise managers can promote effective internal control of enterprises (Henry et al. 2011) and affect enterprise performance (Conyon and He 2011; O’Connor and Rafferty 2010), debt cost (Kabir et al. 2013), asset valuation (O’Connor and Rafferty 2010), external risk (Campbell et al. 2007), and socially responsible investment (Jian and Lee 2015).

Because of the motivational effect, executives will work harder with higher pay, demonstrating their effort is worth the pay (Malul et al. 2021; Buck et al. 2008). In the daily operation of the company, executives know more than the shareholders due to asymmetric information. Executives are more likely to over-invest in CSR activities in line with agency theory. There are several reasons for this. First, engaging in more CSR activities can improve executives’ reputations (Hassen and Ghardadou 2020). Second, the impact of environmental risk and negative social events easily signifies the management’s failure (Zou et al. 2015). Third, the determinants of economic performance are multiple, the shareholders cannot place all the blame on managers. Therefore, CSR is a source of agency problems because management may use firm resources to engage in conspicuous CSR investments (Kao et al. 2018). Based on principal-agent theory, we proposed the following overinvestment hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Management salary incentives has a positive effect on CSR & CER.

With the continuous improvement and development of China’s securities market, equity incentives have also become an important part of management compensation in China (Liu et al. 2014). The experience of principal-agent theory shows that due to the inconsistency between corporate social responsibility and shareholders’ goal of maximizing stock value (Firth et al. 2006), granting managers appropriate equity to encourage them to pay more attention to corporate finance cannot only solve the principal-agent problem (He 2008) but also help to maintain the interests of shareholders and reach the best decision (Shu and Thomas 2017; Ullah et al. 2021). Specifically, executives’ stock ownership increases the range and likelihood of compensation. For managers, the higher the corporate performance, the higher the stock market value, and the higher their actual income.

The trade-off hypothesis indicates that the costs of CSR reduce profits (Makni et al. 2009), and participating in CSR activities cannot guarantee higher corporate performance (Marsat and Williams 2013; Shahbaz et al. 2020). CSR has few short-term measurable economic benefits (Kao et al. 2018). Holding the company’s shares is equivalent to facing relatively high risks and returns (Zhou et al. 2021), and fulfilling social responsibility is an activity with a large investment and slow return.

However, China’s stock market has a short history, higher volatility, and a “policy market” (Zhang et al. 2023). The stocks on the Chinese stock market are not worth long-term holding. As a result, rational managers invest less in social responsibility. Hence, we put forth the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Management equity incentives have a negative effect on CSR & CER.

Methodology and data

Model

This study aims to assess the influence of executive compensation incentives on CSR & CER in Chinese energy enterprises. The panel data fixed effects model is employed, considering the data used in the analysis is panel data. The specific setting of the baseline model is shown in Eq. (1).

Where the explained variable CSR(CER)it represents the CSR (or CER) score of the enterprise i in the period t. The core explanatory variable Incentiveit denotes the management salary incentive or equity incentive of enterprise i in period t. Control variable Xit includes the basic characteristics and operating conditions of enterprises. θi and μt represent the individual and time-fixed effects respectively, and εit is an error term.

Although the fixed-effect model can control for the effects of omitted variables that do not change over time, endogeneity problems still exist due to time-variant omitted variables and reverse causality. To deal with such issues, we also conduct the analysis using the instrumental-variable regression method. As the explanatory variable in this study is the executive salary incentive and equity incentive, the instrumental-variable (IV) regression model for these two variables will be discussed separately.

First, for executive salary incentive, we construct the instrumental variable by interacting the total salary payment of all enterprises in the industry and the rank of the financial performance in the first five years for each enterprise. Return on Assets (ROA) was used to measure the financial performance. The construction of this instrumental variable borrowed ideas from a similar instrumental variable developed in (Nakamura and Steinsson 2014; Ma and Meng 2022), which is a kind of “Bartik” approach transformation. The reason for this instrumental variable design is that the total salary payment of an industry is relatively exogenous for an individual enterprise. When the total executive payment of an industry increases, the salary payment of an enterprise with higher initial financial performance will increase more. This is a common assumption when using “Bartik” instrumental variable strategy. The discussion of the exogeneity of the instrumental variables is further discussed in the robustness test.

Although the initial financial performance of an enterprise may affect the current CSR, this has been fully absorbed by enterprise fixed effects as enterprise-level time-invariant factors. Meanwhile, even though the initial financial performance has a time-variant influence on CSR, the interaction term between initial firm financial performance and time-fixed effect can control this confounding. The estimation equation of first-stage regression is as follows:

Where Salaryit is the endogenous variable, executive salary incentive, IV_Sit is the instrumental variable, the interaction term between the total salary payment of the industry and the rank of the financial performance in the first five years for each enterprise, Zi * μt is the interaction term between initial firm financial performance and time-fixed effect, other variables are similar as the baseline model.

The estimation equation of second-stage regression is as follows:

\(\widehat{{Salary}}_{it}\) is the fitted value of the endogenous variable, executive salary incentive, other variables are similar as before.

Second, we used a similar method for executive equity incentive to construct the instrumental variable as a salary incentive. The instrumental variable in this case is the interaction term between the shareholding ratio of management in the industry and the rank of the ratio of controlling shareholders’ share ownership in the first five years of each enterprise. The shareholding ratio of management in an industry generally affects the equity incentive of an enterprise. Similarly, the confounding influences of initial share ownership of an enterprise on CSR have been absorbed by fixed effects and interactive fixed effects. The first stage regression model for executive equity incentive is as follows:

Where Equityit is the endogenous variable, executive equity incentive, IV_Eit is the instrumental variable of executive equity incentive, Zi * μt is the interaction term between initial share ownership of an enterprise and time fixed effect, other variables are similar as the baseline model.

The estimation equation of second-stage regression is as follows:

Where \(\widehat{{Equity}}_{it}\) is the fitted value of the endogenous variable, executive equity incentive, other variables are similar as Eq. (4).

Data sources

The research focuses on China’s energy enterprises: enterprise-level data pertaining to eight sub-sectors, including electric power, power generation equipment, electrical grid, gas, oil and natural gas, coal, energy equipment, and environmental protection, are obtained in the Wind databaseFootnote 3 and used as research samples. The CSR & CER score comes from the social responsibility reports of listed companies released by Hexun (http://www.hexun.com). The evaluation system investigates five aspects and sets 13 secondary indicators and 37 tertiary indicators to evaluate CSR & CER. All other variables are derived from the China Stock Market Accounting Research Database (CSMAR, https://www.gtarsc.com). The CSMAR database covers the main fields of China’s economy and finance, can provide relatively comprehensive and accurate information about listed companies, and has been widely recognized in academic research.

Considering the data availability and release time, we limit this study’s time range to 2010–2021. In the process of data-matching and processing, we obtained 3272 sample data after excluding ST, * ST, and PT companies, as well as excluding the pre-listing data.

Variable description

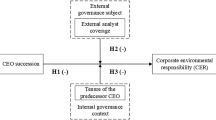

Based on the needs of the research, the variables are set as shown in Fig. 1; specific explanatory and descriptive statistical analyses of all variables are displayed in Table 1.

The explained variables are CSR & CER, and their highest scores are 100. The data come from Hexun.com, including five sub-indicators: shareholder responsibility, employee responsibility, supplier, customer and consumer rights and responsibility, environmental responsibility, and social responsibility. The highest score of sub-indicators is also 100, accounting for 30%, 15%, 15%, 20%, and 20% of the total weighted score, respectively. The core explanatory variable is management incentives, including salary and equity incentives. Managers include directors, supervisors, and senior managers. Salary incentive is estimated by the logarithm of the annual compensation of management personnel. Equity incentive is measured by the shareholding ratio of management personnel.

To control the influence of omitted variables, we include a series of enterprise-level control variables with reference to previous literature, which are total liability ratio (Espahbodi et al. 2016), rate of return on equity (Ratti et al. 2023), the year after the company goes public (Espahbodi et al. 2016), number of employees (Wang et al. 2021), CEO duality and shares held by the top ten shareholders of company (Tsang et al. 2021), value of TobinQ, proportion of the largest shareholder and the number of senior managers (Zhou et al. 2021).

In order to eliminate doubts about multicollinearity, the study conducted a correlation test for variables, and Table 2 shows the correlation coefficient matrix between variables. Most of the coefficients shown in Table 2 are less than 0.4, which indicates that there is no obvious multicollinearity problem.

Regression result and analysis

Baseline regression

Table 3 lists the regression results of management compensation incentives (core explanatory variable) and CSR score (explained variable). Models (1) and (2) are the baseline model, which is the common panel data fixed effects model. Models (3) and (4) are the IV estimation method

The results in model (1) show that the effects of management salary incentives on CSR score is positive and significant, while the effects of management equity incentives on CSR score is negative and significant in model (2).

Models (3) and (4) provide the estimation results of the instrumental variable method of the impact of salary incentive and equity incentive on CSR, respectively. From the results of the first stage estimation, the estimation coefficients of the instrumental variables of salary and equity in the two models are both very significant. At the same time, the test results of weak instrumental variables show that the instrumental variables in the two models are not weak, indicating that they are suitable instrumental variables. From the estimation results of the second stage, the salary incentive is significantly positive and the equity incentive is significantly negative, which is consistent with the results of the benchmark model. However, the difference is that the absolute value of the estimated coefficient of management incentive in the two instrumental variable models is higher than that in the benchmark model. This also suggests that the role of management incentives may be underestimated before the endogenous problem is controlled.

Model (3) reports that the regression coefficient of salary incentive is 15.213, suggesting that every 1% increase in total management salary can increase the CSR score by about 15. Based on the model (4), the regression coefficient of equity incentives is −0.774, revealing that each 1% increase in management shareholding will reduce the CSR score by 0.774. The negative effect of the change in equity incentives is less than the promotion effect of salary incentives. As for the result of control variables, the dual role of CEO and chairman has a stable negative effect on the CSR score. In other words, the concurrent employment of these two positions will reduce the performance of CSR. Furthermore, the regression coefficient of the total liability ratio is significant at the 1% level, indicating that the more debt a company has, the less it invests in CSR investment.

The economic activities of energy enterprises are more likely to harm the environment. Therefore, environmental responsibility is one of the most important aspects of energy enterprises’ social responsibility. Therefore, after verifying the effects of management compensation incentives on total social responsibility, the score “environmental responsibility” sub-index score (CER) is taken as the explained variable, and regression analysis is performed again. The results are summarised in Table 4.

Similar to the analysis of CSR, in Table 4, models (1) and (2) are common fixed-effect model estimates, and (3) and (4) are instrumental variable method estimates. As can be seen from the results in Table 4, salary incentive is significantly positive, while equity incentive is significantly negative. The estimation results of the instrumental variable method model are consistent with the common fixed effect. The results of the first-stage instrumental variable estimation and weak instrumental variable test also show that the instrumental variable is suitable in this case. However, from the absolute value of the estimation coefficient, the estimation result of salary incentive and equity incentive in the instrumental variable method model are both greater than that of the common fixed effect model. These results are very similar to the results of CSR in Table 3.

Based on the regression results in Table 4, management compensation incentives exert a significant effect on CER, but the absolute values of regression coefficients of core explanatory variables are smaller than those in Table 3. The results of model (3) imply that the regression coefficient of salary incentive is 5.645, and the regression coefficient of management shareholding is −0.245 in the model (4). The implication is that each 1% increase in the total management salary can increase the CER score by 5.645, and for each 1% increase in management shareholding, the CER score will be decreased by 0.245.

Heterogeneity

The industry heterogeneity analysis is undertaken. We divided all industries into two types. One is the electricity and environment industry, including electric power, electrical grid, and environmental protection industry. The other is the conventional energy and equipment manufacturing industry, including gas, oil and natural gas, coal, power generation equipment, energy equipment industry.

Table 5 gives estimates of industry heterogeneity. According to the estimated results of models (1) and (2), the interaction terms of salary incentive and whether it is the electricity and environment industry (EL_EN) are not significant in the two models, which indicates that the impact of salary incentive on CSR and CER is the same for the two types of industries. However, in models (3) and (4), the interaction terms of equity incentive and electricity and environment industry dummy variables (EL_EN) are both significantly negative. This means that the impact of equity incentives on CSR and CER differs between the electricity and environmental industry and the traditional energy and equipment manufacturing industry. The negative impact is even more pronounced in the electricity and environmental industry.

China’s state-owned enterprises (SOE) are socially oriented and bear more social responsibilities (Monkkonen et al. 2019) and employment burdens in the process of economic and social development (Li 2008). To determine the heterogeneous effect of management incentives on CSR in enterprises with different ownership types, the sample enterprises are divided into two parts according to the state holding status in state-owned enterprises and non-state-owned enterprises. The regression results are listed in Table 6.

It can be seen from the results in Table 1 that the interaction terms between state-owned enterprises and salary incentives are significantly positive. This shows that compensation incentives have a greater positive effect on CSR for state-owned enterprises. The main reason may be that the government is unable to distinguish the losses of state-owned enterprises from the burden of social responsibility or managers’ mismanagement due to information asymmetry. In addition, as shareholders of state-owned enterprises, the government and the state do not seek to maximize corporate performance (Chang and Wong 2009). Therefore, salary incentive does not cause the management to pay attention to the operating profits of the enterprise, managers of state-owned enterprises are more willing to increase their CSR investments to enhance their reputation.

The coefficients of interaction terms in models (3) and (4) are not significant, which shows that the equity incentives for the two types of enterprises are similar.

China, as the largest developing country, has a vast territory, complex terrain, uneven population distribution, and significant regional differences in economic level. Taking all these factors into account, the sample enterprises are also divided into two parts according to the region where the enterprises are located. As China’s eastern coastal areas are relatively developed, the level of economic and social development is relatively high. Generally speaking, China can be divided into the eastern coastal developed areas and inland areas. The results of regional heterogeneity analysis are shown in Table 7. We find that the interaction terms of management incentives and regional dummy variables are not significant in all models. This shows that there is no regional difference in the impact of salary incentive and equity incentive on CSR or CER in China. Regardless of the relatively developed coastal areas or other areas, manager incentives significantly impact CSR or CER.

Robustness test

We conducted a series of tests to further investigate the robustness of the results. The details are as follows:

In addition to the control variables in the baseline regression model, more control variables are added to the model in order to control more characteristics. These variables include the proportion of independent directors (PID), the cash ratio (CR), and the growth rate of owners’ equity (GRO). According to the regression results in Table 8, after adding control variables, the regression coefficient and significance of management compensation incentives are consistent with the previous regression results, suggesting that our regression results are robust.

Considering the differences in the size of enterprise management personnel, the core explanatory variables are changed into per unit salary incentive and per unit equity incentive, and the regression is repeated. The results are shown in Table 9. The regression coefficients of the core explanatory variables are significant and match the baseline regression.

The rating of CER in Hexun changed in 2018. Therefore, we removed the post-2018 sample and reestimated the model. The results are shown in Table 10. It can be seen that the estimated results of all models are similar to the baseline model, which indicates that changes in CER scores are unlikely to affect the estimated results.

Some companies have missing values in some years. The sample in the analysis is an unbalanced sample. If the sample loss is not random, there may be estimation bias caused by sample self-selection. Therefore, we removed some samples containing missing values and used the balanced panel data for estimation. The results are shown in Table 11, which clearly shows that the estimates agree with the baseline model. This also indicates that sample self-selection may have little effect on the estimated results.

In order to further verify the exogeneity of the instrumental variables, we simultaneously add both endogenous and instrumental variables to the reduced form model. The results are provided Table 12. It can be seen that in all models, the estimated coefficients of endogenous variables, management salary incentive and equity incentive, are significant, while the instrumental variables are not. To some extent, this shows that the instrumental variables can only affect the explained variables through endogenous variables. In other words, the instrumental variables are relatively exogenous in this model.

Conclusions

The study of energy CSR & CER under the background of global carbon neutrality is of great significance to economic and social development. Based on the data of China’s listed energy companies from 2010 to 2021, the effects of management compensation incentives, including salary incentives and equity incentives, on CSR & CER are explored. To solve the endogeneity problem, the paper employed the identification strategy of the instrumental variable estimation method.

The econometric results show that management compensation incentives can significantly affect CSR and CER. The degree of influence and the significance are heterogeneous among enterprises in different sub-industries, different ownership properties, and different regions. Firstly, the effects of management salary incentives and equity incentives on CSR and CER are not the same. Salary incentives can significantly promote the implementation of CSR and CER: however, the higher the equity incentive, the worse the performance of CSR and CER. Secondly, there is significant heterogeneity in the effects of management compensation incentives on CSR& CER. Based on the heterogeneity analysis of enterprise ownership, it is found that the salary incentives have a greater impact on CSR&CER of state-owned enterprises, although the impact on CER is not significant. There is no difference in the impact of equity incentives on state-owned and non-state-owned enterprises. Based on the heterogeneity analysis of sub-industries, it is found that there is no difference in the impact of salary incentives on CSR & CER of sub-industries. However, we found that the impact of equity incentives on CSR and CER differs between the electricity and environmental industry and the traditional energy and equipment manufacturing industry. And the negative impact is even more pronounced in the electricity and environmental industry. The analysis based on regional heterogeneity did not find regional differences in the impact of compensation incentives on CSR & CER. Finally, the robustness of the regression results is verified by a series of robustness tests.

The CSR & CER of energy enterprises is of great significance to social development. Enterprises, especially new energy enterprises, should focus on the salary incentive of management personnel and appropriately reduce their equity holdings to improve energy enterprises’ social & environmental responsibility and increase their positive externalities. Besides, weakening equity incentives can help enterprises in the electricity and environmental industries to undertake more corporate social & environmental responsibility. Moreover, the negative effect of management shareholding in state-owned enterprises cannot be ignored. The government should pay attention to the development of state-owned energy enterprises, limit the incentive system such as management shareholding ratio through policies, and replace it with mainly salary incentives.

Considering future research, this study’s research paradigm and experience can be applied to the discussion of CSR & CSR in other emerging manufacturing industries, such as biopharmaceutical, information technology, and other industries. Besides, from practical experience, the relationship between government and business has a certain impact on energy enterprises’ social and environmental responsibilities. Therefore, this perspective can also be considered in future corporate social responsibility analysis to obtain fresh empirical evidence, especially in discussions in the energy industry.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Statistical Review of World Energy 2020 | 69th Edition.

Statistical Review of World Energy 2021 | 70th Edition.

A brief introduction to the related industries in the Wind database may be given as follows: (1) The electric power industry refers to the industry that produces and distributes electric energy. (2) The power generation equipment industry denotes the industry that produces and sells power generation equipment products. Common power generation equipment includes thermal power equipment, hydropower equipment, wind power equipment, nuclear power equipment, and photovoltaic equipment. (3) The electrical power grid industry is an industry that produces and sells products related to the electrical power grid. The electrical power grid is an entity composed of substations and transmission and distribution lines with various voltages in the power system, which is called power network, referred to as a power grid. It consists of three units: substations, transmission, and distribution. The task of a power network is to transmit and distribute electric energy and regulate the frequency and voltage. (4) The fuel gas industry refers to the use of coal, oil, gas and other energy sources to produce gas, or the production of biogas from agricultural or rural wastes such as livestock and poultry manure and straw, or the purchase and distribution of liquefied petroleum gas and natural gas, and the sale of gas to users, as well as maintenance and management activities in the process of transmission, distribution, and use of coal gas, liquefied petroleum gas, and natural gas. (5) The oil and gas industry refers to those industries engaged in oil and gas exploration, production, refining, marketing, transportation or petrochemical industry. (6) The coal industry refers to those industries engaged in coal resources exploration, coalfield development, coal mine production, coal storage and transportation, processing and conversion, and environmental protection. (7) The energy equipment industry is the industry that produces and sells mining equipment, including offshore oil and gas equipment, shale gas equipment, and coal-mining machinery. (8) The environmental protection industry denotes the general name of technical product development, commercial circulation, resource utilization, information service, project contracting and other activities conducted in the national economic structure for the purpose of preventing environmental pollution, improving the ecological environment, and protecting natural resources.

References

Ahmed M, Shuai C, Ahmed M (2023) Analysis of energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions trend in China, India, the USA, and Russia. Int J Environ Sci Te 20:2683–2698

Becchetti L, Ciciretti R, Dalò A (2018) Fishing the Corporate Social Responsibility risk factors. J Financial Stab 37:25–48

Berrone P, Gomez-Mejia LR (2009) Environmental Performance and Executive Compensation: An Integrated Agency-Institutional Perspective. Acad Manag J 52:103–126

Bolourian S, Angus A, Alinaghian L (2021) The impact of corporate governance on corporate social responsibility at the board-level: A critical assessment. J Clean Prod 291:125752

Brüggen A, Zehnder JO (2014) SG&A cost stickiness and equity-based executive compensation: does empire building matter? J Manag Control 25:169–192

Buck T, Liu X, Skovoroda R (2008) Top executive pay and firm performance in China. J Int Bus Stud 39:833–850

Cai Y, Jo H, Pan C (2011) Vice or Virtue? The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Executive Compensation. J Bus Ethics 104:159–173

Campbell K, Johnston D, Sefcik SE, Soderstrom NS (2007) Executive compensation and non-financial risk: An empirical examination. J Account Public Policy 26:436–462

Chan RYK, Ma KHY (2017) Impact of executive compensation on the execution of IT-based environmental strategies under competition. Eur J Inf Syst 26:489–508

Chang EC, Wong SML (2009) Governance with multiple objectives: Evidence from top executive turnover in China. J Corp Financ 15:230–244

Chen JW, Zhang F, Liu LL, Zhu L (2019) Does environmental responsibility matter in cross-sector partnership formation? A legitimacy perspective. J Environ Manag 231:612–621

Conyon MJ, He L (2011) Executive compensation and corporate governance in China. J Corp Financ 17:1158–1175

Correa R, Lel U (2016) Say on pay laws, executive compensation, pay slice, and firm valuation around the world. J Financ Econ 122:500–520

Cronqvist H, Yu F (2017) Shaped by their daughters: Executives, female socialization, and corporate social responsibility. J Financ Econ 126:543–562

Du W, Wang F, Li M (2020) Effects of environmental regulation on capacity utilization: Evidence from energy enterprises in China. Ecol Indic 113:106217

Du KR, Cheng YY, Yao X (2021) Environmental regulation, green technology innovation, and industrial structure upgrading: The road to the green transformation of Chinese cities. Energy Econ 98:105247

Espahbodi R, Liu N, Westbrook A (2016) The effects of the 2006 SEC executive compensation disclosure rules on managerial incentives. J Contemp Account Econ 12:241–256

Firth M, Fung PMY, Rui OM (2006) Corporate performance and CEO compensation in China. J Corp Financ 12:693–714

Guo J, Wang Y, Yang W (2021) China’s anti-corruption shock and resource reallocation in the energy industry. Energy Econ 96:105182

Han S-L, Lee JW (2021) Does corporate social responsibility matter even in the B2B market?: Effect of B2B CSR on customer trust. Ind Mark Manag 93:115–123

Hassen RB, Ghardadou S (2020) The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Executive Compensation. Open Access Libr J 07:1–18

He L (2008) Do founders matter? A study of executive compensation, governance structure and firm performance. J Bus Venturing 23:257–279

Hegde SP, Mishra DR (2019) Married CEOs and corporate social responsibility. J Corp Financ 58:226–246

Henry TF, Shon JJ, Weiss RE (2011) Does executive compensation incentivize managers to create effective internal control systems? Res Account Regul 23:46–59

Ho HL, Kim N, Reza S (2022) CSR and CEO pay: Does CEO reputation matter? J Bus Res 149:1034–1049

Huang S, Liu H (2021) Impact of COVID-19 on stock price crash risk: Evidence from Chinese energy firms. Energy Econ 101:105431

Huang JB, Chen X, Yu KZ, Cai XC (2020a) Effect of technological progress on carbon emissions: New evidence from a decomposition and spatiotemporal perspective in China. J Environ Manage 274:110953

Huang JB, Lai YL, Wang YJ, Hao Y (2020b) Energy-saving research and development activities and energy intensity in China: A regional comparison perspective. Energy 213:118758

Islam T, Islam R, Pitafi AH, Xiaobei L, Rehmani M, Irfan M, Mubarak MS (2021) The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer loyalty: The mediating role of corporate reputation, customer satisfaction, and trust. Sustain Prod Consum 25:123–135

Jahmane A, Gaies B (2020) Corporate social responsibility, financial instability and corporate financial performance: Linear, non-linear and spillover effects - The case of the CAC 40 companies. Finance Res Lett 34:101483

Javeed SA, Latief R, Jiang T, San Ong T, Tang Y (2021) How environmental regulations and corporate social responsibility affect the firm innovation with the moderating role of Chief executive officer (CEO) power and ownership concentration? J Clean Prod 308:127212

Javeed SA, Lefen L (2019) An Analysis of Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Performance with Moderating Effects of CEO Power and Ownership Structure: A Case Study of the Manufacturing Sector of Pakistan. Sustainability 11:1-25

Jia ZJ, Lin BQ (2021) How to achieve the first step of the carbon-neutrality 2060 target in China: The coal substitution perspective. Energy 233:121179

Jian M, Lee K-W (2015) CEO compensation and corporate social responsibility. J Multinatl Financ Manag 29:46–65

Jiang H, Hu Y, Su K, Zhu Y (2021) Do government say-on-pay policies distort managers’ engagement in corporate social responsibility? Quasi-experimental evidence from China. J Contemp Account Econ 17:100259

Kabir R, Li H, Veld-Merkoulova VY (2013) Executive compensation and the cost of debt. J Bank Financ 37:2893–2907

Kalyar MN, Rafi N, Kalyar AN (2013) Factors affecting corporate social responsibility: An empirical study. Syst Res Behav Sci 30:495–505

Kao EH, Yeh CC, Wang LH, Fung HG (2018) The relationship between CSR and performance: Evidence in China. Pac-Basin Financ J 51:155–170

Kim T, Kim H-D, Park K (2020) CEO inside debt holdings and CSR activities. Int Rev Econ Financ 70:508–529

Kong D, Shu Y, Wang Y (2021) Corruption and corporate social responsibility: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China⋆. J Asian Econ 75:101317

Kuo Y-F, Lin Y-M, Chien H-F (2021) Corporate social responsibility, enterprise risk management, and real earnings management: Evidence from managerial confidence. Financ Res Lett 41:101805

Latapí Agudelo MA, Johannsdottir L, Davidsdottir B (2020) Drivers that motivate energy companies to be responsible. A systematic literature review of Corporate Social Responsibility in the energy sector. J Clean Prod 247:119094

Li L (2008) Employment burden, government ownership and soft budget constraints: Evidence from a Chinese enterprise survey. China Econ Rev 19:215–229

Li Y, Peng HG, Huang QH, Zhong HW, Zhang E, Ren JJ, Dong DS (2019) Research report on corporate social responsibility of China [M]. Beijing: Soclal sciences academic press (China)

Liu X, Lu J, Chizema A (2014) Top executive compensation, regional institutions and Chinese OFDI. J World Bus 49:143–155

Luo G, Liu Y, Zhang L, Xu X, Guo Y (2021) Do governmental subsidies improve the financial performance of China’s new energy power generation enterprises? Energy 227:120432

Ma G, Meng Y (2022) Capitalization of Fiscal Transfers and Its Impact on Welfare Divergence. Econ Res J 57:65–81

Makni R, Francoeur C, Bellavance F (2009) Causality Between Corporate Social Performance and Financial Performance: Evidence from Canadian Firms. J Bus Ethics 89:409–422

Malul M, Rosenboim M, Shapira D (2021) Are Very High Salaries Necessary for Achieving Economic Efficiency? J Behav Exp Econ 94:101725

Marsat S, Williams B (2013) CSR and market valuation: International evidence. Bank Mark Investors: Acad Profess Rev 123:29–42

McWilliams A, Siegel D (2001) Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad Manag Rev 26:117–127

Meng L, Huang B (2018) Shaping the Relationship Between Economic Development and Carbon Dioxide Emissions at the Local Level: Evidence from Spatial Econometric Models. Environ Resour Econ 71:127–156

Monkkonen P, Deng G, Hu W (2019) Does developers’ ownership structure shape their market behavior? Evidence from state owned enterprises in Chengdu, Sichuan, 2004–2011. Cities 84:151–158

Nakamura E, Steinsson J (2014) Fiscal stimulus in a monetary union: Evidence from US regions. Am Econ Rev 104:753–792

Nguyen NTT, Nguyen NP, Thanh Hoai T (2021) Ethical leadership, corporate social responsibility, firm reputation, and firm performance: A serial mediation model. Heliyon 7:e06809

O’Connor ML, Rafferty M (2010) Incentive effects of executive compensation and the valuation of firm assets. J Corp Financ 16:431–442

Pareek R, Sahu TN (2024) The nonlinear effect of executive compensation on corporate social responsibility performance. Rajagiri Manag J 18(1):43–55

Ratti S, Arena M, Azzone G, Dell’Agostino L (2023) Environmental claims and executive compensation plans: Is there a link? An empirical investigation of Italian listed companies. J Cleaner Prod 422:138434

Shaer HA, Albitar K, Liu J (2023) CEO power and CSR-linked compensation for corporate environmental responsibility: UK evidence. Rev Quant Financ Account 60:1025–1063

Shahbaz M, Karaman AS, Kilic M, Uyar A (2020) Board attributes, CSR engagement, and corporate performance: What is the nexus in the energy sector? Energy Policy 143:111582

Shi M (2019) Overinvestment and corporate governance in energy listed companies: Evidence from China. Financ Res Lett 30:436–445

Shu SQ, Thomas WB (2017) Managerial Equity Holdings and Income Smoothing Incentives. J Manag Account Res 31:195–218

Sinha A, Mishra S, Sharif A, Yarovaya L (2021) Does green financing help to improve environmental & social responsibility? Designing SDG framework through advanced quantile modelling. J Environ Manage 292:112751

Strusnik D, Brandl D, Schober H, Fercec J, Avsec J (2020) A simulation model of the application of the solar STAF panel heat transfer and noise reduction with and without a transparent plate: A renewable energy review. Renew Sust Energ Rev 134:110149

Tang C-H (2016) Impacts of future compensation on the incentive effects of existing executive stock options. Int Rev Econ Financ 45:273–285

Tilt CA (2016) Corporate social responsibility research: the importance of context. Int J Corp Soc Responsib 1:2

Tsang A, Wang KT, Liu S, Yu L (2021) Integrating corporate social responsibility criteria into executive compensation and firm innovation: International evidence. J Corp Financ 70:102070

Turyakira P, Venter E, Smith E (2014) The impact of corporate social responsibility factors on the competitiveness of small and medium-sized enterprises. South Afr J Econ Manag Sci 17:157–172

Ullah S, Adams K, Adams D, Attah-Boakye R (2021) Multinational corporations and human rights violations in emerging economies: Does commitment to social and environmental responsibility matter? J Environ Manage 280:111689

Wang CH, Zhang S, Ullah S, Ullah R, Ullah F (2021) Executive compensation and corporate performance of energy companies around the world. Energy Strateg Rev 38:100749

Wei L, Li G, Zhu X, Sun X, Li J (2019) Developing a hierarchical system for energy corporate risk factors based on textual risk disclosures. Energy Econ 80:452–460

Xu Y, Liu Y, Lobo GJ (2016) Troubled by unequal pay rather than low pay: The incentive effects of a top management team pay gap. China J Account Res 9:115–135

Yeh C-C, Lin F, Wang T-S, Wu C-M (2020) Does corporate social responsibility affect cost of capital in China? Asia Pac Manag Rev 25:1–12

Yu L, Gao XW, Lyu JJ, Feng Y, Zhang SL, Andlib Z (2023) Green growth and environmental sustainability in China: the role of environmental taxes. Environ Sci Pollut R 30:22702–22711

Zhang Y, Lu X, Xiao JJ (2023) Does financial education help to improve the return on stock investment? Evidence from China. Pac-Basin Financ J 78:101940

Zhou B, Li Y-M, Sun F-C, Zhou Z-G (2021) Executive compensation incentives, risk level and corporate innovation. Emerg Mark Rev 47:100798

Zou HL, Zeng SX, Lin H, Xie XM (2015) Top executives’ compensation, industrial competition, and corporate environmental performance Evidence from China. Manag Decis 53:2036–2059

Zribi W, Boufateh T (2020) Asymmetric CEO confidence and CSR: A nonlinear panel ARDL-PMG approach. J Econ Asymmetr 22:e00176

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China [Grant No. 22CJY056].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiaxin He: Conceptualization; Methodology; Investigation; Writing-original draft. Jingyi Li: Software; Data curation; Formal analysis; Writing-original draft. Xing Chen: Supervision; Validation; Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, J., Li, J. & Chen, X. Enhancing the corporate social & environmental responsibility of Chinese energy enterprises: A view from the role of management compensation incentive. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 224 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02687-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02687-1