Abstract

Socioeconomic variables have been studied in many different contexts. Considering several socioeconomic variables as well as using the standard series clustering technique and the Ward’s algorithm, we rank the countries in the world and evaluate the similarity and inequality between geographic areas. Various relationships between variables are also identified. Additionally, since the Gini coefficient is one of the most frequently used metrics to measure economic inequality, with a global scope, we model this coefficient utilising machine learning techniques. 16 exploratory variables are utilised, which pertain to the health (9), economic (2), social labour protection (4) and gender (1) fields. International repositories that include time series of variables referred to these domains as well as education and labour market fields are used.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Relevance of regional similarity-inequality

Both monitoring and studying the socio-economic characteristics of geographical areas are highly crucial for the construction of both regional and national policies. This analysis helps to promote partnerships between territories in order to overcome obstacles, as well as to identify actions that, having been successfully applied in specific zones, could be implemented in others.

The United Nations General Assembly established the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in 2015 (United Nations, w.dc.). This global agreement puts focus on equality. Sustainable Development Goals SDG 10 and 16 specifically refers to reducing inequality. This is carried out through the development of mechanisms that reject discrimination in all its forms and promote universal levels of well-being and inclusion. Other goals aim to make progress in the social field, reducing gaps in certain aspects. These include achieving gender equality through the empowerment of all women and girls (SDG 5), ensuring equitable quality education, (SDG 4) as well as the promotion of inclusive and sustainable industrialisation (SDG 9) (United Nations, w.dc.).

There is a consensus in the economic research that a country should not only be evaluated by its economic productivity indicators, but also by its capacity to reduce poverty and inequality (Gasparini et al. 2014). The urgency of decreasing dissimilarity (and thus increase equality) through public policies requires measuring and analytical instruments. The study of indicators on different countries and regions of the world, including the characterisation of their relationships is of tremendous interest. This is a fundamental step to define improvement strategies that contribute to the achievement of the SDG (Gasparini et al. 2014).

Inequality (and subsequently equality) manifests itself in society in various ways, so it is necessary to carry out an analysis that encompasses all its dimensions. Not only will we focus on income and consumption, but also health, education, gender and justice, among others (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2018). While all societies are unequal with respect to different variables or indexes, not all are unequal at the same magnitude. Quantifying the intensity of both similarity and inequality is a matter of interest. The above can be done by means of indexes or variables that can be compared over time, both between countries and groups of individuals.

This investigation uses mathematical analysis, statistics and machine learning to examine variables and indexes related to socioeconomic aspects.

Background

With regard to similarity analysis (Hanel et al. 2019) point out that research focuses mostly on describing differences, rather examining similarities which could be at least as interesting. This led authors to explore similarities between 22 social variables (such as moral attitudes, human values, and trust) within 6 commonly used social categories: gender, age, education, income, country of residence, and religious denomination. Pairwise comparisons were made in each category between variables. The results proved that, on average, the level of similarity between pairs of variables exceeded 90%. In the field of health, (Stern 2020) studies the difficulties of different groups in accessing health care. The authors suggest that analysis of similarities between different marginalised groups can be very useful in determining and overcoming systematic inequalities in health care.

There are pieces of research that have analysed the similarity between regions from different perspectives. The World Bank publishes biannual reports exploring macroeconomic and development trends in Africa, East Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, the Middle East and North Africa, and South Asia (World Bank 2020). This trend analysis is based on the study of similarities between the countries belonging to each region.(Economic League 2023) uses a similarity index to compare the states within The United States. It incorporates 12 socioeconomic factors, which are: total population, ethnic heterogeneity, gender proportion, median household income, labour force participation, and poverty rate. In addition to these factors, crime rate per 100,000 residents, life expectancy, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, and enrollment rate are also taken into account. Gini coefficient, and industry makeup by proportion of employed labour force are also considered. In the investigation, Philadelphia and New Orleans showed many common characteristics (Economic League, 2023). (Niskanen and Lin 2001) explored both the regional similarities of forest resources and the socio-economic structures of European Union countries in order to improve the comparability of territories for studies examining the contribution of forest resources towards regional development. The study focused on the forest-dominant (Finland and Sweden) and Mediterranean-Eastern-Atlantic (Greece, Portugal and Ireland) groups of countries. There is also research that measures communalities only between two geographical areas. Therefore, (European Comission 2022) characterises the territories to be compared via data downloaded from Eurostat. The similarity between the two territories is assessed using the cosine similarity metric (Han et al. 2012). Each area is symbolised by a vector whose components represent the value taken by each of the variables considered in the analysis. The variables used in the investigation are: population density, fertility rate, population change, proportion of women, GDP per capita in purchasing power standards (PPS), Gross Value Added (GVA) at basic prices (European Comission 2022). The experiment is carried out in the European UnionFootnote 1.

The research described in this paper considers a broader geographical scope (220 countries) and assesses not only equality, but also inequality. The investigation is carried out, using tweenty-six variables, by education, economic, labour market, and gender domains in Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa and Oceania. In particular, series clustering techniques are applied, which allows the analysis to be implemented considering the values of the features in each country and domain over several years.

With respect to inequality, the Gini coefficient, as opposed to the so-called “Lorenz curve” which graphically represents the level of inequality in a society, provides a figure for comparing inequality between different regions. (Kuznets 1955), who is considered one of the first authors to examine the concept of inequality, suggested that the relationship between income and inequality exhibited a concave form. Growth in its initial stages is accompanied by an increase in inequality, and as growth increases, less inequality is generated. (Alesina and Rodrik 1994) advocated that a high level of inequality generates negative effects on growth, which is why it is necessary to create redistributive policies. (Cingano 2014) conducted an analysis in member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which found that income inequality had a significant negative impact on growth. In particular, in those regions in which the gap between low-income households and the rest of the population was greater. The author argues that policies to reduce income inequality entail not only social outcomes, but also actions to sustain long-term growth (Rendón-Morquecho and Marroquín-Arreola 2020).

The above-mentioned research probes that in order to study inequality in more depth, it is necessary to understand the relationship between Gini coefficient and other socio-economic variables. (Sitthiyot and Holasut 2020) proposed three indicators to compose an inequality index: the Gini coefficient itself combined with the share of income in the hands of the richest 10% and the portion of income in the hands of the poorest 10% (Sitthiyot and Holasut 2020). The information that was used by the authors in the research comes from the World Bank database and the OECD income distribution database between 2005 and 2015. The outcomes showed that the analysis of income inequality could distinguish between countries that had the same Gini coefficient but which, nevertheless, showed different income gaps between the top and bottom 10 percent.

(Blesch et al. 2022) demonstrated the existence of contradictory research findings concerning the relationship between economic inequality and other factors. This might be partly due to an exclusive focus on the Gini coefficient, which might capture inequality in a limited way. The authors conceptualise the measurement of inequality as a task of analysing the reduction of the income distribution. The results suggested that multi-parametric models consistently outperform monoparametric models (i.e. models that represent monoparametric measures such as the Gini coefficient) (Blesch et al. 2022). Simulations carried out by the authors showed that the best-fitting model - the two-parameter Ortega model - distinguished between inequality located in the lowest income percentiles and that positioned in the highest income percentiles (Blesch et al. 2022). This highlighted the importance of multi-parametric models and data-driven methods for examining inequality.

With regards to the investigation of the Gini coefficient and its relationships with other variables, scientific studies exist in fields as diverse as fisheries (Pérez et al. 2005), rainfall (Benhamrouche and Martín-Vide 2012), or logistics of flower distribution (Grajales et al. 2016). It has also been utilised in both depression (Maldonado et al. 2007) and Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) analysis (Haidich and Ioannidis 2004). The Gini coefficient has also been used to quantify the epidemiological heterogeneity in some infections (Abeles and Conway 2020)Footnote 2.

With respect to socioeconomic sphere, in the education domain, some relationships have been established between Gini coefficient values and both performance and learning outcomes in various subjects (Traverso 2019), (Martínez 2012). Several analyses exist which explore the relationships between maternal mortality, the Human Development Index (HDI), the Gini coefficient, per capita income and social vulnerability (Do Socorro and Dos Santos 2017). (De Sousa Filho et al. 2022) evaluates the income segregation in some of the main Brazilian cities. The authors detected specific socioeconomic characteristics referred to residential segregation by income according to the 2010 Brazilian demographic census. The Income Dissimilarity Index (IDI) was computed at the census tract level in each city, subsequently comparing it with the Gini coefficient, as well as with other local socioeconomic variables. The residential segregation was also analysed utilising a dissimilarity index (De Sousa Filho et al. 2022). (Araújo et al. 2022) correlated the existence of protected natural areas in a country with the variables GDP, Human Development Index, Gini Index, and World Happiness Index (WHI). Information on 145 countries was used. (Rukmana and Ramadhani 2021) utilising the Gini coefficient as a metric and the occupational structure based on the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO), investigated income inequality in depth (Rukmana and Ramadhani 2021). However, in spite of all the above, the analysis of the Gini and its relationships with other variables has not been fully exploited yet in social research.

With respect to the Gini modelling, (Koç and Akın 2021) applied the random forest, support vector, and multiple linear regression models to estimate the Gini coefficient of OECD countries. The data used in the projection corresponded to the period 2015–2018. A set of 6 variables were used to construct the model: Gini coefficient, tax revenue, GDP (us dollar/capita), unemployment rate (% of the labor force), inflation (Annual growth rate %), and current health expenditure (% of GDP). According to performance metrics, the random forest model was proposed as the best model among those implemented (Koç and Akın 2021). (Zhang 2022) applied Deep Learning technology for generating a model in order to anticipate the Gini coefficient. Data obtained from Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) and OECD related to The United States was used. Nineteen attributes were selected. The time range was monthly from January 1959 to August 2020.

Motivation and goals of the research

As mentioned, this research covers a broader geographical scope, as regional similarities and inequalities are studied through variables related to four socio-economic domains. In addition, it explores the relationship between the Gini coefficient and various educational, economic, employment and gender variables. The World Bank website includes a number of socioeconomic variables for countries around the world over several years (World Bank, w.da.), (World Bank, w.db.). This information provides a large volume of data with relevant potential for social research, such as the one carried out in this paper.

In particular, through the analysis of the Gini coefficient, it is possible to take measures to correct the inequality detected and in turn move towards a more equitable society. The correlation of the Gini coefficient with other factors can guide public policies (social, health, education, etc.) aimed at improving the population’s quality of life.

Specifically, in this paper, we answer the following research questions:

-

Is it possible to detect similarities-dissimilarities between countries and regions of the world by studying time series data related to educational, economic, gender and labour market variables?. For each of the socioeconomic variables analysed, is it possible to rank the countries used in this research?

-

Is it possible to discover unknown relationships between some of the variables that characterise the above-mentioned domains?

-

Is it possible to build a model capable of predicting the Gini coefficient as a function of certain socioeconomic variables referring to various fields (health, economic, labour protection and gender)? To which of the above mentioned domains are these variables related?

The goals of this research are derived from the answers to the questions previously exposed. With respect to the novelties of this research, they are:

-

Based on the annual series of each analysed variable, a clustering of series is used in order to categorise each country according to the conglomerate in which it is located. Various indexes were utilised to estimate the best number of clusters.

-

Derived from the above, regional similarity-inequality metrics are presented. It makes possible to assess the existing regional similarity-inequality in educational, economic, labour market and gender domains.

-

Several new relationships between socioeconomic variables are identified.

-

Using one of the algorithms that has been shown to exhibit good performance metrics, the Gini coefficient is modelled based on variables from many different domains and not only from variables referring to the economic field. The model is valid for any country in the world, not being restricted to a specific country, organisation or region.

Although much less extensive in terms of the domains, variables and geographical areas examined in this research, a number of studies have explored the relationships between socio-economic indicators through statistical analysis (Tamhane 1979), (Tamhane 2009), (Macků et al. 2020), (Macků et al. 2020), (Ponizovskiy et al. 2020), (Kaur et al. 2019), (Senapati and Ojha, 2019), as well as machine learning models (Mirhassani and Hooshmand 2019), (Gault et al. 1987), (Speybroeck et al. 2013). These procedures have also been successfully applied to the analysis of systems of various types, such as biological systems (Bzdok et al. 2018), demographic, medical and educational systems (McArdle and Ritschard 2013) or political systems (Goldstone et al. 2010).

Materials and methods

Repositories and software programs

In order to carry out the research, the following dataset were utilised:

Gender Statistics Database, which can be retrieved from the World Bank (World Bank, w.da.). It is a comprehensive source for the latest sex-dis-aggregated data and gender statistics covering demography, education, health, access to economic opportunities, public life and decision-making. The data set contains 888 variables, covering 264 countries, from 1960 to 2019Footnote 3. Not all data are available. The downloaded file contains the following information:

< CountryName > < CountryCode > < IndicatorName > < IndicatorCode > < 1960 > < 1961 > ..... < 2019 >

Gini Coefficient Dataset, which can be retrieved from (World Bank, w.db.), contains the Gini coefficient for 264 countries, from 1960 until 2018Footnote 4. However, data is not available for all countries, and this issue will be dealt with in the "Modelling the Gini coefficient".

Gender Inequality Index (GII), which includes a composite indicator, showing inequality in achievement between females and males in reproductive health, empowerment and labour market domains. The dataset contains information referring to 189 countries, from 1995 until 2019Footnote 5, taking values in the range [0, 1] (United Nations, w.da.).

With the purpose of carrying out the research, several programs in R language (R, w.d.) were implemented, which carried out the following functionalities:

-

Execution of an exploratory data analysis, which is required as a prior step to the analysis on the data collection. It includes visualisation of the statistical distributions, and identification of the most common, most rare or missing values.

-

Application of clustering techniques to the data series (further explained in the "Regional socioeconomic similarities-inequalities").

-

Building of a predictive Gini coefficient model, which anticipates the value of the Gini coefficient from certain variables. The details of the procedures and algorithms implemented are explained in the aforementioned "Modelling the Gini coefficient".

-

Graphic representations (correlations and maps).

The following packages in R are utilised: library(locpol), sm, cluster, purrr, descomponer, caret, ggplot2, ggpubr, ranger, doParallel, factoextra, NbClust, ggplot2, gplots, ggspatial, maps, readxl, stats, ggcorrplot, RColorBrewer, viridis, MASS, dplyr, tidyr, skimr, tidymodels, rworldmap, FactoMineR, Rfast, matrixStats, gplots, data.table, sf, scales and tseries. All software programs followed the life cycle of any software specification: analysis, design, implementation and testing.

Geographical scope and variables to be studied

Both stand-alone countries and groupings of countries by continent are analysed. Specifically, 53, 33 and 12 countries are considered in Europe, North America, and South America respectively. 53, 50 and 19 countries are included in the Africa, Asia and Oceania regionsFootnote 6,Footnote 7.

For the purposes of this research, due to the large volume of variables in the repository, only a subset of them, considering their relevance, was selected. They were chosen by experts with experience and knowledge in each domain, then analysed, where a multiple voting system was used. The selected variables are:

Educational domain (see (World Bank, w.da.)):

-

SE. ENR. PRSC. FM. ZS, Participation school enrollment, primary and secondary (gross value), gender parity index (GPI).

-

SE. ENR. TERT. FM. ZS, Participation school enrollment, tertiary (gross value), GPI.

-

SE. PRM. ENRR. FE, Participation school enrollment, primary, female (% gross value).

-

SE. PRM. ENRR. MA, Participation school enrollment, primary, male (% gross value).

-

SE. SEC. ENRR. FE, Participation school enrollment, secondary, female (% gross value).

-

SE. SEC. ENRR. MA, Participation school enrollment, secondary, male (% gross value).

-

SE. TER. ENRR. FE, Participation school enrollment, tertiary, female (% gross value).

-

SE. TER. ENRR. MA, Participation school enrollment, tertiary, male (% gross value).

-

SE. XPD. PRIM. PC. ZS, Inputs Government expenditure per student, primary (% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita).

-

SE. XPD. SECO. PC. ZS, Inputs Government expenditure per student, secondary (% of GDP per capita).

-

SE. XPD. TOTL. GD. ZS, Inputs Government expenditure on education, total (% of GDP).

Economic domain (see (World Bank, w.da.) and (World Bank, w.db.)):

-

NY. GDP. MKTP. CD, GDP (current US$).

-

NY. GDP. MKTP. KD. ZG, GDP growth (annual %).

-

SI. POV. GINI, Poverty: Gini coefficient.

Labour market domain (see (World Bank, w.da.)):

-

SL. TLF. ADVN. FE. ZS, labour force with advanced education, female (% of female working-age population with advanced education).

-

SL. TLF. ADVN. MA. ZS, labour force with advanced education, male (% of male working-age population with advanced education).

-

SL. TLF. BASC. FE. ZS, labour force with basic education, female (% of female working-age population with basic education).

-

SL. TLF. BASC. MA. ZS, labour force with basic education, male (% of male working-age population with basic education).

-

SL. TLF. TOTL. FE. ZS, labour force, female (% of total labour force).

-

SL. UEM. TOTL. FE. NE. ZS, Unemployment, female (% of female labour force) (national estimate).

-

SL. UEM. TOTL. MA. NE. ZS, Unemployment, male (% of male labour force) (national estimate).

Gender domain (see (World Bank, w.da.)):

-

SG. TIM. UWRK. FE, Proportion of time spent on unpaid domestic and care work, female (% of 24 hour day).

-

SG. TIM. UWRK. MA, Proportion of time spent on unpaid domestic and care work, male (% of 24 hour day)

-

SG. GEN. MNST. ZS, Proportion of women in ministerial level positions (%).

-

SG. GEN. PARL. ZS, Proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments (%).

In the gender domain, the Gender Inequality Index (GII) was also used (see (United Nations, w.da.)).

Analysis of socioeconomic variables

Characterisation of time series and correlations

For each country, the stationarity of the stochastic process (Bressler 2001) producing the time series associated to each analysed variable is examined. Each time series can be decomposed as follows (Alonso w.d.), (Buteikis 2020):

Where:

-

m is ranged from 1 to N.

-

N symbolises the amount of analysed socioeconomic variables (26).

-

SEm,t corresponds to the variable that describes the m time series in t.

-

TreCm,t corresponds to the variable that shows the trend element in t, which, as is known, symbolises variations in data along time.

-

SeaCm,t corresponds to the variable that depicts the seasonal change in t. This element, as is known, is related to regular mofications found on the season. We verified the aforementioned seasonal attributeFootnote 8(Rios and Hurtado 2008) through the Augmented Dickey-Fuller check (Mushtag 2011). In particular, we took into account the following assumptions, with a significance level equal to 0.05:

-

H0: “The time series does not present seasonality.”

-

Ha: “The time series presents seasonality.”

If p − value < 0.05 the alternative hypothesis would be taken into consideration.

-

-

RanCm,t is the variable that shows the unpredictable element in t, which corresponds to fluctuations derived from unforeseeable conditions.

With the purpose of finding possible relationships between the variables analysed, the correlations between them are calculated. The normality of the distributions of each variable was checked in order to determine whether the correlation should be calculated using Spearman’s or Pearson’s methods. To this end, the Shapiro-Wilks (Llc, 2010) test was used, with a significance level equal to 0.05. The hypotheses were:

-

H0: “The sample is normally distributed”

-

Ha: “The sample is not normally distributed”

If p − value ≤ 0.05, H0 is rejected and correlation is estimated utilises the Spearman’s method. Otherwise H0 is taken and Pearson’s method is used.

Modelling the Gini coefficient

As we have mentioned, one of the most relevant variables to analyse similarities/inequalities in a country is the Gini coefficient. A modelling of the Gini coefficient as a function of other socioeconomic variables is of particular interest. In the following pages, we explain the steps followed to carry out this modelling process.

An activity that is required prior to the construction of the model is the preparation of the dataset to be used. In particular, the following tasks were carried out:

-

Elimination of the columns: < CountryName > , < CountryCode > , and < IndicatorName >

-

Transpose the data so that each column contains values for one < IndicatorCode > , and each row includes information for one year.

-

Elimination of rows without information about Gini coefficient SI. POV. GINI

-

Removal of those columns where all rows have more than 30% of missing information.

-

In those cells with missing values:

-

If the column corresponds to a categorical variable, the column’s mode is set as the cell value.

-

Otherwise, the cell is assigned the value of the column average.

-

When several variables show a correlation between them higher than 0.9, all but one are eliminated.

-

A supervised learning approach is then used to build the model. This technique allows us to build an algorithm that from various features anticipates the value of the target for cases not utilised in the learning process. As mentioned, in the present investigation, a set of historical data with different features is available and the outcome for each case is known. The input variables are the values for each indicator code. The Gini coefficient values are the outcomes.

As is well known in machine learning, the construction of a prediction model (Mouronte-López, 2021), (Mouronte-López and Subirán, 2022), (Mouronte-López and Gómez, 2023), (Mouronte-López et al. 2024) requires us to perform one or various data partitions in training and test sets. In the same way as Mouronte-López (2021), Mouronte-López and Subirán (2022), Mouronte-López and Gómez (2023), Mouronte-López et al. (2024) and other pieces of research, in this research, a cross validation procedure, with identical G partitions of the data set is applied. The model is trained G times. This mechanism results in G evaluations of the test error, making it possible to make the following estimation of the average error: (Mouronte-López, 2021), (Mouronte-López, 2022), (Mouronte-López & Gómez, 2023), (Mouronte-López et al. 2024):

vfold_cv function in R is used in order to perform a G − Fold Cross-Validation procedure. Specifically, a value of G equal to 5 is taken.

The data set for the execution of the cross validation procedure consists of 1,344 rows, which corresponds to 80% of the prepared data set. With respect to the validation set, it contains 336 rows, which represents around 20% of the aforementioned processed data set.

Next, a random forest model, which was introduced in (Breiman 2001) is implemented. It operates by building a multitude of Decision trees at training time and outputting the average prediction of the individual trees. The following steps are performed (Doan w.d.):

-

1.

A random sample with replacement is considered from the data, which means that several samples will be utilised various times in order to construct an individual tree. This technique is named bootstrapping. (Doan w.d.).

-

2.

A random sample without replacement of the features is considered. This implies that each tree handles only a subset of all the features (Doan w.d.).

-

3.

Then, the initial Classification and Regression Trees (CART) (Loh 2011) partition of information is constructed (Doan w.d.).

-

4.

Step 2 is carried out for each following split until the tree reaches the required size (Doan w.d.).

-

5.

The Steps from 1 to 4 are carried out re executed as many times as indicated by the model’s hyperparametersFootnote 9, which are explained below.

The following hyper parameters are utilised:

-

trees, which is the number of Decision trees in the forest. It should be sufficiently high (Oshiro et al. 2012), (Probst and Boulesteix 2017).

-

mtry, which symbolises the amount of randomly drawn candidate variables out of which each split is selected when growing the tree.

-

max.depth, the maximum depth that corresponds to trees.

With the purpose of achieving a rapid implementation of the random forest algorithm, the ranger package in R is used. The caret package is also applied. The doParallel package is utilised, as a means of encouraging a mechanism to execute loops in parallel.

In order to obtain the variables with the greatest influence, both node purity and the permutation metrics are used, which are defined as follows:

-

Permutation importance metric (Hjerpe 2016) Let Bt symbolise the Out Of Bag (OOB) samplesFootnote 10 for a tree t and let Lt(xi, yi) represent the prediction accuracy at the ith training. The importance for variable Xj in tree t can be defined as (Hjerpe, 2016).

$$V{I}^{(t)}({X}_{j})=\mathop{\sum}\limits_{i\in {B}^{t}}.L({T}_{t}({x}_{i},{y}_{i}))-L({T}_{t}({x}_{i,{\pi }_{j}}),{y}_{i})\left.\right)$$(3)\(({x}_{i,{\pi }_{j}})=({x}_{i,1},...,{x}_{{\pi }_{j}(i),{x}_{i,j+1},...{x}_{i,p}})\), and where πj is a random permutation of n integers. In regression settings the prediction accuracy is \(L(\hat{y},y)\) is defined as the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). The variable importance metric for variable Xj is calculated as the sum of the importance over all trees in the forest (Hjerpe 2016)

$$VI({X}_{j})=\frac{{\sum }_{t\in B}V{I}^{t}({X}_{j})}{Number\,Of\,Trees}$$(4) -

Gini Impurity can be defined as (Lee et al. 2020):

$$Gini(S)=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j=1}^{j=n}{p}_{j}(1-{p}_{j})=1-\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j=1}^{j=n}{p}_{j}^{2}$$(5)n: number of classes in node spaces S pj: frequency of class j in node space S

The variable importance ranking for the two methods was the same. After this, from the ordered set of variables from highest to lowest importance, the optimised model was calculated by eliminating variables one by one (starting with the least significant) and selecting the model with maximum RMSE.

Regional socioeconomic similarities-inequalities

With the purpose of analysing both regional similarities and regional inequalities, clustering of series approach is applied. Clustering analysis is a multivariate technique whose fundamental purpose is to group objects into conglomerates, in such a way that they have high internal homogeneity and relevant external heterogeneity (Lazar w.d.). The procedure joins objects to form conglomerates based on their distance/similarity.

This research applies clustering analysis to a set of univariate time series, corresponding to each of the variables analysed (World Bank, w.da.).

Where, as previously mentioned:

m is ranged from 1 to N, N represents the amount of analysed variables.

T symbolises the number of observations.

It should be observed that we are making a comparison between time series with the same size and sampled at the same instant in time. This allows us to compute the similarity between time series by applying an element-wise method:

where d is a distance on RT.

Once the pairwise dissimilarity matrix is obtained, the Ward’s (Ward2 method) algorithm was applied to estimate the clusters (Murtagh and Legendre, 2011). This mechanism begins with T clusters, each including a single object. At each step, all possible mergers of two clusters are tried. The algorithm merges the two clusters (C1, C2) that result in the smallest increase in the value of the distance between C1 and C2, D(C1, C2), which is defined as (Murtagh and Legendre, 2011):

where |. | symbolises the cardinality and mass of the cluster (Murtagh and Legendre, 2011).

∥. ∥ is the Euclidean distance squared using norm: if i,\({i}^{{\prime} }\,\) ∈ R∣J∣, i.e. these observations have values on attributes j ∈ 1, 2, . . . , ∣J∣, J is the attribute set,∣. ∣ symbolises, cardinality, then \({d}^{2}(i,{i}^{{\prime} })=| | i-{i}^{{\prime} }| {| }^{2}\)\(={\sum }_{j}{({i}_{j}-{i}_{j}^{{\prime} })}^{2}\)(Murtagh and Legendre 2011).

Various metrics are used for determining the best number of clusters, which are (Charrad et al. 2022):

-

Ch (Calinski and Harabasz, 1974), Dunn (Dunn 1974), Tau (Rohlf 1974), (Milligan 1980), Gamma (Baker and Hubert 1975), Ratkowsky (Ratkowsky and Lance 1978), Ptbiserial (Milligan 1980), (Milligan 1981), Silhouette (Rousseeuw 1987), Kl (Krzanowski and Lai, 1988). The best number of clusters is determined by the highest value.

-

McClain (McClain and Rao 1975), Cindex (Hubert and Levin 1976), Db (Davies and Bouldin 1979), Gplus (Milligan 1980), (Rohlf 1974), Sdindex (Halkidi et al. 2000), Sdbw (Halkidi and Vazirgiannis 2001). The optimal number of clusters is defined by the lowest value.

Before applying clustering to the data, the series must be prepared since there may be missing values for a duo (Countryi, Yearj). When this happens, in the case of a non-categorical variableFootnote 11, for each Countryi an average must be calculated considering all years (Yearj) in which values exist, and varying j from 1 to T. This average is then taken as the appropriate value for the Yearj in the duo (Countryi, Yearj). By contrast, in the case of a categorical variable, the mode is taken.

In order to analyse the similarity both by socioeconomic and geographical areas, the following definitions are established:

-

Re: geographical area.

-

NV: number of variables to be studied.

-

Njk: number of times j and k countries ∈ Re are together in any cluster.

$${N}_{jk}=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{NV}{e}_{jk}$$(9)ejk = 1, if j, k countries ∈ Re are located in the same cluster, 0 otherwise.

-

Sp: p − level similarity existing in a specific socioeconomic domain, where p takes the values 25, 50, 75, 100.

$${S}_{p}=\frac{\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i = 1}^{NV}{s}_{jk}}{NV};\,\forall \,j,\,k\,countries$$(10)

For p = 100

- sjk = 1, if NV ≤ Njk > 0.75*NV,

- sjk = 0, otherwise.

For p = 75

- sjk = 1, if 0.50*NV < Njk ≤ 0.75*NV

- sjk = 0, otherwise.

For p = 50

- sjk = 1, if 0.25*NV < Njk ≤ 0.50*NV

- sjk = 0, otherwise.

For p = 25

- sjk = 1, if 0 ≤ Njk ≤ 0.25*NV

- sjk = 0, otherwise.

S100 and S25 represent the highest and lowest levels of similarity. Sp in a specific domain, represents the level of proportion calculated on all countries and variables analysed in which two countries are located in the same cluster. For example, a value of S100 equal to 0.50 means that 50% of the countries are located in the same cluster for a ratio less than or equal to one and greater than 0.75 estimated on all variables related to the domain analysed.

In a domain, the level of regional inequality is set in a complementary way to that of similarity. The levels of similarity S100, S75, S50 and S25, are equivalent to degrees of inequality I25, I50, I75 and I100.

Results

Characterisation of socioeconomic variables and correlations

As previously mentioned, for each country, an analysis of the stationarity of the stochastic process generating the time series associated with the examined socioeconomic variables was carried out. According to the results of the Augmented Dickey-Fuller test (Mushtag 2011) (p − value < 0.05), in the Supplementary Material Document, Table S3, Table S4, Table S5 and Table S6 display those countries whose time series exhibit a stationary behaviour trend by explored domain and investigated variable.

With respect to the correlations between variables, the p − value obtained in the Shapiro–Wilks test was lower than 0.05 for all analysed variables. Hence, the Spearman’s method was applied for the calculation of correlations, which are depicted in Fig. 1.

Regional socioeconomic similarities-inequalities

For each variable studied, it was necessary to estimate the optimal number of clusters, in order to establish which countries are in each cluster.

In particular, for all socioeconomic variables, each of the mentioned indexes in "Regional socioeconomic similarities-inequalities" have been computed with the purpose of selecting the optimum number of clusters. The package NbClust in R was used for this purpose. Tables showing the number of clusters obtained for the best estimate of each index are included in the Supplementary Material Document (Table S7, S8). The number of clusters selected is the value which is provided by a larger number of indexes. Tables 1–4 show for each variable, considering all calculated indexes, the optimum number of clusters utilising the “majority principle”. The number of countries by cluster is also depicted.

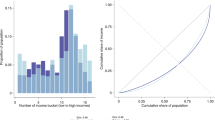

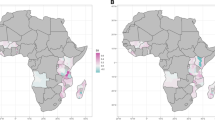

Figure 2 depicts the detected clusters for the SI. POV. GINI variable. This is clarified later in the Discussion section.

Tables 5–8 show for the analysed variables average, standard deviationFootnote 12, and median by detected clusters.

Once the number of countries in each cluster was determined, regional similarity and inequality were computed, as explained in "Regional socioeconomic similarities-inequalities". Table 9 depicts the Sp and Ip metrics in Europe, African, Asian, North American, South American and Oceania regions.

Everything explained in this section is described in more detail below, in the section entitled Discussion.

Modelling the Gini coefficient

The best hyper parameters of the model are shown in Table 10. Table 11 depicts the average RMSE according to the number of variables considered. There exists an appropriate trade-off between the number of explanatory variables in the model and the average RMSE, so the final number of variables selected are 16 yielding an average RMSE equal to 3.55701. These variables, selected by their importance, according to the metrics of purity and permutation, which are described in the Overview of used methods section are (World Bank, w.da.):

-

SP. ADO. TFRT: Adolescent fertility rate (births per 1000 women ages 15–19)

-

SI. POV. DDAY: Poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population)

-

SP. POP. 65UP. TO. ZS: Population ages 65 and above (% of total population)

-

SP. POP. 0014. TO. ZS: Population ages 0–14 (% of total population)

-

SP. DYN. CBRT. IN: Birth rate, crude (per 1000 people)

-

SH. STA. ODFC. ZS: People practising open defecation (% of population)

-

SP. DYN. TFRT. IN: Fertility rate, total (births per woman)

-

NY. GDP. PCAP. KD: GDP per capita (constant 2010 US$)

-

SH. STA. ODFC. UR. ZS: People practising open defecation, urban (% of urban population)

-

SL. SRV. EMPL. FE. ZS: Employment in services, female (% of female employment) (modelled ILO estimate)

-

SP. DYN. CDRT. IN: Death rate, crude (per 1000 people)

-

SL. TLF. CACT. MA. ZS:labour force participation rate, male (% of male population ages 15+) (modelled ILO estimate)

-

SL. AGR. EMPL. FE. ZS: Employment in agriculture, female (% of female employment) (modelled ILO estimate)

-

SP. POP. 1564. TO. ZS:Population ages 15–64 (% of total population).

-

SL. EMP. VULN. FE. ZS: Vulnerable employment, female (% of female employment) (modelled ILO estimate)

-

SH. PAR. LEVE. AL: Length of paid shared parental leave (days)

This is discussed in more detail in the Discussion section.

Discussion

Characterisation of time series and correlations

With regard to the seasonality feature, as previously mentioned, there are several countries where the stochastic process generating time series for a specific variable m, SEm,t, exhibit stationary behaviour. According to this property (Alonso, w.d.), in these countries, it would be possible to compute the time series mean with all observations, and utilise this magnitude to predict a new observation. Confidence intervals for the predictions could also be calculated assuming that SEm,t follows a specific distribution (Alonso, w.d.).

Next, we analyse the correlations shown in Fig. 1. As is well known, the correlation between two variables can be perfect, strong, moderate, low or non-existent, which is precisely described in the Supplementary Material Document (see Table S2).

The gender parity index (GPI) of the matriculation in primary and secondary education shows a positive moderate correlation with the GPI of the enrollment in tertiary education. The level of female and male school enrollment in primary education exhibits a relevant correlation with each other, similar to what happens in the tertiary level. However, according to (ONU, w.d.), there is a gap between rich and poor countries. Thus, 2% of children aged 6–11 are out of primary school in high-income countries, while this percentage rises to 19% in low-income nations (ONU, w.d.). The female matriculation at the tertiary and secondary levels are also highly correlated with each other. The above seems to indicate that the women enrolled at the secondary level usually continue their studies at the tertiary level.

With respect to the relationship between educational and economic domains, the enrollment in secondary and tertiary education presents a negative moderate correlation with the income inequality, equivalent to what happens with the government expenditure per student in secondary education. Male school matriculation in secondary education exhibits a high positive correlation with the GDP, while the correlation is moderately positive in the case of female enrollment. This is the equivalent to what occurs with respect to female and male enrollment at the tertiary level. The government expenditure per student in primary education has a moderate positive correlation with the matriculation at secondary and tertiary levels. Nevertheless, government expenditure per student in primary and secondary education shows a high correlation with each other.

Research addresses the effect of public spending and on education on income inequality (Sylwester 2002), (Keller 2010), (Gutiérrez-Garrido and Acuña-Duarte 2019). The results are inconclusive regarding the negative relationship between the two variables, especially in emerging economies such as Latin America. Education, however, appears to have been particularly effective in reducing inequality in Africa. The study (Abdullah et al. 2015) finds that education affects both ends of the income distribution: it reduces the income share of higher earners and increases the income share of lower earners. Empirical research (Solaki 2013) explains that in the long-run, real GDP per capita is impacted by modifications in primary, secondary, tertiary education and educational public expenditures. (Viracheat and Dash 2011) identified a high correlation between the gross enrollment ratio in higher education and the per capita GDP.

Regarding the relationships between education and labour market domains, the male labour force with basic education has a moderate negative correlation with the enrollment of both sexes in tertiary education, and with the male matriculation at primary level. The total female labour force also presents a positive moderate correlation with the enrollment in secondary and tertiary education for both sexes. The labour force of both genders with basic education have a moderate negative correlation with male unemployment. The female labour force with basic education exhibits a positive moderate correlation with those, of both sexes, who obtained an advanced level of education as well as a high correlation with the male labour force with a basic education. If we look at unemployment, it can be observed that unemployment of both sexes is highly correlated with each other.

The above is in accordance with some pieces of research (Craig and Xueda 2011), which explain that education appreciably increases re-employment rates of the unemployed. Specifically, large impacts have been detected in the age range from 12 until 16 years of schooling (Craig & Xueda, 2011). However, the correlations between education and the unemployment rate is unclear. Although a negative partial correlation between schooling and job loss exists, evidence of causal relations at the secondary schooling level has not been found. In contrast, this connection has been discovered in the case of higher education (Craig and Xueda 2011).

With respect to the relationships between labour force and economic domains, the male labour force with a basic level of education exhibits a moderate positive correlation with the Gini coefficient, which shows a moderate negative correlation with the entire female labour force. The results obtained in (Parada 2016) demonstrates that changes in female employment contribute to reducing poverty levels and inequality. This is in line with (Asongu et al. 2020), which finds that improving the economic status of women in sub-Saharan Africa positively affects the economic status of entire families.

The proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments has a moderate positive correlation with the enrollment in secondary education for both sexes and with the government expenditure on education. The above is in accordance with some research (EMC 2014) which suggests that a connection exists between the female socioeconomic status and political participation. It must be noted that the political representation can be a mechanism for promoting gender equality in the workplace as well as in the household. Women’s participation in parliamentary seats has increased, but only modestly (UNDP 2021).

Regional socioeconomic similarities-inequalities

In order to facilitate the understanding of this work, and in particular of everything described below, please refer to Tables 5–8 where the results of the clustering analysis are represented.

Economic domainFootnote 13

According to (United Nations, w.db.), although global economic output has tripled since 1990, the gap between countries and regions remains considerable. The effects of inequalities are not limited to purchasing power. Inequalities also have an impact on life expectancy and access to basic services, such as water, healthcare or education, and can restrict human rights because of the prevailing sense of injustice (United Nations, w.db.).

(UNU-WIDER, 2021) notes that the results of the Gini index analysis indicates that between 1950 and 2019, dollar income differences between people (absolute inequality) increased globally.

Furthermore, (García-Herrero et al. 2015) based on the Gini analysis from 1980 to 2015, makes predictions for the year 2025 and concludes that the middle classes will comprise two thirds of the world’s population by that year. Additionally, (CEPAL/IEF, 2014) explains that the fiscal policy has various effects on wealth redistribution.

As can be observed in Fig. 2 as well as in Tables 2, 6, three clusters have been detected in the study of the variable SI. POV. GINI. Each cluster has an average of 34.51, 45.98 and 55.31. According to the information shown in Table 9, S100 is equal to 0.6143, 0.0404 and 0.3938 in European, North American and South American areas. S100 presents the values 0.3008, 0.2550, 0.1329 in Asian, African and Oceania. With respect to I100, it exhibits magnitudes equal to 0.1742, 0.5076, 0, 0.3914, 0.2950, and 0.2405 in European, North American, South American, Asian, African and Oceania areas. Therefore, the greatest internal inequalities in the economic sphere are found, in order, in North America, Asia, Africa and Oceania. The highest internal similarities are detected in Europe.

The above is in line with specific research that points to significant differences between countries and areas in Africa’s northern and southern countries are better off than Western, Central and Eastern areas. The poorest areas have had negative real GDP per capita growth rates during the last decades of the 20th century (Guisan and Exposito 2001). Regarding Asia, (Jain-Chandra et al. 2016) explains that this region has been increasing its inequality since 1990 (Balakrishnan et al. 2013), (Dabla-Norris et al. 2015). (Zhuang et al. 2014) detected that 12 out of 30 countries showed an increase in inequality over the last two decades, which seems to be due to an increase in the share of higher income earners.

The highest similarity index is found in South America and Europe. In spite of some modest improvements taking place in Caribbean countries in recent years, debt is above 60% of GDP. In addition, low tax revenues, relevant debt servicing and small fiscal space have impacted on public investment (OECD, 2019). The Regional Human Development Report produced by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (UNDP, 2021), also explained that, despite the progress made in recent decades, the countries located in Latin America and the Caribbean region are more unequal than those located in other regions with similar levels of development.

In Europe, the relevant similarity is due to the regional policy pursued by the European Union, where the convergence of single national economies towards a regional economic zone is considered (Eppler et al. 2016). This is consistent with research indicating that European nations are economically stable regions, where all factors are predominantly positive (Palevičienė and Dumciuviene 2015).

Education domainFootnote 14

Regarding the educational domain, as can be observed in Tables 1, 5, the percentage of male enrollment in tertiary education (SE. TER. ENRR. MA), shows two clusters. Both have average values equal to 10.64 and 42.27, as well as medians equal to 8.36 and 40.34. Focusing on female enrollment at this educational level (SE. TER. ENRR. FE), there are two clusters with average values equal to 11.28 and 51.57. Medians present the values 7.47 and 48.87. Important differences can be observed between the two clusters for each sex. It can be seen that there is a higher percentage of female enrollment. Regarding government expenditure on education (SE. XPD. TOTL. GD. ZS), three clusters exist as depicted in Tables 1 and 5. They have average values equal to 4.12, 11.10 and 9.50. Medians are 3.97, 10.57 and 44.33.

If S100 is considered, it can be observed in Table 9, that it exhibits the values 0.3669, 0.1112 and 0.3025 in Europe, North America, and South America. It shows the values 0.2610, 0.1271 and 0.0316 in Africa, Asia and Oceania. With regards to I100 it takes values equal to 0.3112, 0.5945, 0.1937, 0.4303, 0.2952, and 0.4948 in Europe, North American, South American, Asian, African, and Oceania. Therefore, the more relevant similarities are to be found in Europe and South America, whereas, the highest discrepancies are located in North America and Oceania.

As a means to achieve its economic objectives, the European Union has considered education as an instrument (Cankaya et al. 2015). Also, in South America, during the 1990s, several regulations intended to improve the access to higher education were put in place (López 2015), (Krotsch and Suasnábar 2002). Since the 21st century, this region has experienced sustained economic growth and an improvement in the distribution of wealth in its societies. This led to a reduction in poverty and an improvement in social development. This also had an impact on government policies, in the form of new and more inclusive regulations to achieve greater development among the poor in higher education (Baisotti 2019). The World Bank, as early as 1993, pointed out that the quality of training in Oceania was generally good, (World Bank 1993).

Labour market domainFootnote 15

With respect to the labour market, as is shown in Tables 3, 7, the total male unemployment (SL. UEM. TOTL. MA. NE. ZS) presents three clusters whose average values are 13.16, 5.17, and 21.90. Medians have the values 13.04, 5.03 and 21.35. Regarding female unemployment (SL. UEM. TOTL. FE. NE. ZS), two clusters have been found. Both have the average values 19.18 and 6.36. Medians are 18.96 and 5.92. If we explore the internal similarities in each region presented in Table 9, the S100 is equal to 0.1960, 0.0760, 0.6038 in Europe, North and South America, while the values are 0.0521, 0.1035, and 0.0726 in Asia, Africa and Oceania. Regarding I100, it takes values equal to 0.2942, 0.7552, 0.0507, 0.4894, 0.5760, 0.3920 in Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa, and Oceania. In accordance with the above, the highest inequality is found in North America and Africa, in contrast, South America has the greatest similarity.

The report (Ball et al. 2013) examines the labour developments in South America in 2018. It detected that, although the regional unemployment rate has not increased since 2015, this has not been a consequence of an increase in labour demand, but has been motivated by a growth in unpaid employment, as well as by the expansion of self employed work and by the increased informality of wage employment. The report manifests that the gender gaps have reduced in participation and employment rates (Ball et al. 2013). Nevertheless, it is not happening due to the unemployment rates (Ball et al. 2013). In most Asian countries, a high irregularity in unemployment benefits exists, as well as many different types of unemployment insurance. Unemployment rates are generally low even in times of economic crisis (Furuoka et al. 2019). Additionally, the report Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020: Reversals of Fortune (World Bank 2020) provides analysis of the causes and consequences of the reversal of shared prosperity on the horizon, and identifies policy principles that countries can use to counteract it.

Gender domain

According to the information included in Table 9, S100 has the value 0 in North America, South America, Asia, Africa and Oceania. It is 0.0036 in Europe. With respect to I100 it takes values equal to 0.6418, 0.9177, 0.6438, 0.5506, 0.6141, and 0.7658 in Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa and Oceania.

As illustrated in Table 7, five clusters are detected for the proportion of time spent by women on domestic work or childcare in a whole day (SG. TIM. UWRK. FE). The clusters have average values equal to 22.91, 19.23, 15.24, 8.36 and 29.89. Median values are 22.64, 19.13, 19.13, 10.41 and 31.04. The above demonstrates that a great diversity among countries exists. In contrast, the proportion of time by men on unpaid domestic and childcare in a whole day (SG. TIM. UWRK. MA) presents two clusters whose average values are 3.94 and 9.39. Medians have the values 4.16 and 9.48. As can be seen, both the average and median values are lower in the case of men, which seems to indicate that they spend less time on domestic chores than women. There is also less diversity among males than among females.

According to the United Nations, women carry out more unpaid care and domestic work than men (UN WOMEN, w.da.). This is in accordance with the report of Oxfam (OXFAM, 2020), which states that women and girls on the whole spend 12.5 billion hours a day on this type of work.

The proportion of women in ministerial level positions (%) (SG. GEN. MNST. ZS) exhibits three clusters with average values 26.50, 13.18, and 40.16, while medians have the values 25.54, 13.23, 37.98. With respect to the proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments (%) (SG. GEN. PARL. ZS), it shows two clusters with average values equal to 11.77 and 28.91, with their medians 12.11 and 27.76. For both variables, we can observe that the representation of women is still far from 50% in all the countries analysed.

Women’s political participation is a relevant element in order achieve gender equality (UI, 2016). The “Women in Politics: 2021” map, built by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) and UN Women, shows that gender inequalities persist (UN WOMEN, w.db.).

Regarding the GII, as is depicted in Table 8, it presents three clusters with averages 0.63, 0.22 and 0.46. Medians are 0.60, 0.22 and 0.45, showing that there is great variability between countries in progress towards gender equality.

Modelling the Gini coefficient

With regards to the variables identified in "Modelling the Gini coefficient" as being of greater importance in the prediction model, the existing research points to some relevant aspects.

With reference to the adolescent fertility rate (SP. ADO. TFRT) feature, (Castro and Fajnzylber 2017) detects, among a substantial sample of individuals from different low-income countries, a statistically significant impact of income inequality on adolescent fertility. Modifications in income inequality are positively and definitely linked to modifications in adolescent fertility (Filho and Kawachi, 2015). Additionally, regarding poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day (2011 PPP) (SI. POV. DDAY) variable, (Burke et al. 2019) determined, using a regression model in which, the percentage of people below the poverty line rose as the Gini coefficient increased. It also established that the percentage of persons living under the poverty line declined as GDP per capita increased, analogous to what happened with respect to literacy rate.

In relation to the variable that describes the percentage of population ages 65 and above (SP. POP. 65UP. TO. ZS), Hertog (2013), which analysed the Gini index for 34 OECD countries, from 1974 until 2010, found that if all ages of the population were considered, a weak positive association would exist between the income Gini and both the lifespan inequality as well as lifespan Atkinson indexes. A weak negative link was identified when only the ages 65 and over were examined (Hertog, 2013). With respect to the percentage of population with ages from 0 until 14 (SP. POP. 0014. TO. ZS) variable, in reference to Latin America and the Caribbean area, (UNICEF, w.d.) indicates that the incidence of poverty for children under 14 is significantly higher than in other age groups.

In relation to The GDP per capita variable (NY. GDP. PCAP. KD), (Lakner et al. 2022), using data related to 166 countries which cover a percentage of 97.5% of the world’s population, simulates various scenarios on global poverty from 2019 to 2030. The investigation explains that if within a country inequality is maintained and the GDP per capita is increased in line with World Bank forecasts, the amount of people in extreme poverty (living on less than US$1.90/day) will remain above 600 million by 2030 (Lakner et al. 2022).

Conclusions

The conclusions obtained for each of the research questions are described below.

Is it possible to detect similarities-dissimilarities between countries and regions of the world by studying time series data related to educational, economic, gender and labour market variables? For each of the socioeconomic variables analysed, is it possible to rank the countries used in this research?

The most important similarities, depending on the region, are to be found in the educational, labour market, economic domain. The largest inequality in all regions is in the domain of gender.

The strongest analogies in economics and education fields are found among the countries of Europe, which is undoubtedly motivated by the inclusion of many of them in the European Union, which has promoted common policies. South America exhibits the largest labour market analogies, similarities in the educational and economic spheres are also remarkable. The North American region shows the highest inequalities in the education, labour market, and gender domains. South America exhibits the largest disparity in the gender domain.

Is it possible to discover unknown relationships between some of the variables that characterise the above-mentioned domains?

The analysis carried out suggests that government spending on secondary education helps to reduce the Gini coefficient. Higher enrollment in both secondary and tertiary education are also signs of greater income equality. The results indicate that larger enrollment in both secondary and tertiary education is associated with higher GDP.

It is interesting to note that male and female primary and tertiary education enrollment are positively correlated. This is similar to what happens with the labour force and unemployment for both sexes. The female matriculation at the secondary and tertiary levels are also positively associated. Basic educated labour forces of both sexes shows a negative correlation with male unemployment. This demonstrates that literacy reinforcement would have a beneficial effect on unemployment.

Government spending on education appears to correlate with the ratio of seats held by women in national parliaments. Finally, it has also been detected that an increase in the female labour force impacts on the reduction of income inequality.

Is it possible to build a model capable of predicting the Gini coefficient as a function of certain socioeconomic variables referred to various fields (health, economic, labour protection and gender)? To which of the above mentioned domains are these variables related?

The Gini coefficient can be well described by a random forest model with 16 explanatory variables. 9 referred to the health field, 2 pertaining to the economic domain, 4 related to the social protection & labour sphere and 1 related to gender issues. Included in the health field are both total and adolescent fertility rates, as well as the population of all age ranges and the birth rate. Also included are figures of those openly practising open defecation in urban areas and elsewhere, as well as the mortality rate. Referring to the economic sphere are the GDP per capita and the poverty headcount index at $1.90 per day. In the domain of social protection and labour are female employment in services and agriculture, as well as women in vulnerable occupations. The male activity rate is also considered. With regards to gender issues, the existence or not of paid parental leave is included.

From most to least relevant, the order of the 16 variables was (World Bank, w.da.). adolescent fertility rate (births per 1000 women aged between 15–19), poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population), population ages 65 and above (% of total population) and population ages between 0–14 (% of total population), birth rate, (per 1000 people), people practising open defecation (% of population), and fertility rate, total (births per woman). These variables were followed by the features GDP per capita (constant 2010 US$), people practising open defecation, urban (% of urban population), employment in services, female (% of female employment) (modelled ILO estimate), and death rate, (per 1000 people). The following positions in the ranking were taken by the variables labour force participation rate, male (% of male population ages 15+) (modelled ILO estimate), employment in agriculture, female (% of female employment) (modelled ILO estimate), population ages 15–64 (% of total population), vulnerable employment, female (% of female employment) (modelled ILO estimate) and, finally, length of paid shared parental leave (days).

We note that both the software packages utilised and the computing applications developed can be useful for the analysis and modelling of other social variables described by annual series.

This work can be continued with a more in-depth study of the gender domain, which has shown the most relevant differences between countries. The random and trend components of the data series that characterise the variables analysed could also be studied.

Data availability

All data used in this research are available in the repositories described in the Repositories and software programs section. The utilised datasets retrieved from the World Bank (Gender Statistics Database (World Bank, w.da.) and Gini Coefficient Dataset (World Bank, w.db.)) are provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), with some additional terms (see (World Bank, w.dc.)). The CC BY 4.0 license allows users of information copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format for any purpose, even commercially. In addition to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially (Creative Commons, w.d.). The used information related to the Gender Inequality Index, which was obtained from the Human Development Reports website (United Nations, w.da.) are copyrighted under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license. (see Human Development Reports, w.d.). This license allows users of the information to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially (Human Development Reports, w.d.).

Notes

It must be noted that Eurostat data is reported according to the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) classification, in which four levels exists: NUTS 0 regions is referred to countries, NUTS 1 corresponds to subnational units that symbolises major socioeconomic zones, NUTS 2 are basic areas for the execution of regional policies, while NUTS 3 is the smallest level (European Comission 2022). (European Comission 2022) originally covered NUTS 3 regions and was expanded to NUTS 2.

Varying from 0 (all populations equal) to 1 (populations having maximal differences), this Gini coefficient was utilised to demonstrate the extent and persistence of inequality of a malaria infection (Abeles and Conway 2020).

At the time in which the results of this research were obtained

At the time in which the results of this research were obtained

At the time in which the results of this research were obtained

The countries considered in each region are listed in the Supplementary Material Document, Table S1.

The main rankings provided by the World Bank are by geographic region (Africa, East Asia and pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, South Asia), by income group, and operating loan categories (World Bank, w.da.).

Parameters that are utilised to control the learning process.

The set of data not used for training and which can be utilised for testing.

A categorical variable is a variable that can take a restricted number of values.

A hyphen means that the standard deviation could not be obtained because only one country was included in the cluster.

For a description of the variables mentioned here, please refer to "Geographical scope and variables to be studied".

For a description of the variables mentioned here, please refer to "Geographical scope and variables to be studied"

For a description of the variables mentioned here, please refer to "Geographical scope and variables to be studied"

References

Abdullah A, Doucouliagos H, Manning E (2015) Does education reduce income inequality? A meta-regression analysis. J Econ Surveys 29:301–316

Abeles J, Conway DJ (2020) The Gini coefficient as a useful measure of malaria inequality among populations. Malaria J 19:1–8

Alesina A, Rodrik D (1994) Distributive politics and economic growth. Quarterly J Econ 109:465–490

Alonso AM (w.d.). Introducción al análisis de series temporales. Cálculo de tendencias y estacionalidad. Department of Statistics. Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. https://halweb.uc3m.es/esp/personal/personas/amalonso/esp/seriestemporales.pdf

Araújo R, Silva H, Salvio M (2022) Statistical correlation between socieconomic indicators and protected natural areas around the world. Revista Árvore 46:1–9

Asongu S, Nnanna J, Acha-Anyi P (2020) Inequality and gender economic inclusion: the moderating role of financial access in Sub-Saharan Africa. Econ Anal Policy 65:173–185

Baisotti P (2019) Higher education and citizenship in Latin America. In J. A. Pineda-Alfonso, N. De Alba-Fernández, & E. Navarro-Medina (Eds.), Handbook of research on education for participative citizenship and global prosperity (pp. 218–244). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-7110-0.ch010

Baker FB, Hubert LJ (1975) Measuring the power of hierarchical cluster analysis. J Am Stat Assoc 70:31–38

Balakrishnan R, Steinberg C, Syed M. (2013) International monetary fund. Working Paper. The elusive quest for inclusive growth: growth, poverty, and inequality in Asia. (Working Paper No. 2013 \152). https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/The-Elusive-Quest-for-Inclusive-Growth-Growth-Poverty-and-Inequality-in-Asia-40709

Ball L, De Roux N, Hofstetter M (2013) Unemployment in Latin America and the Caribbean. Open Econ Rev 24:397–424

Benhamrouche A, Martín-Vide J (2012) Avances metodológicos en el análisis de la concentración diaria de la precipitación en la España peninsular. Anales De Geografía De La Universidad Complutense 32:11–27

Blesch K, Hauser OP, Jachimowicz JM (2022) Measuring inequality beyond the Gini coefficient may clarify conflicting findings. Nat Hum Behav 6:1525–1536

Breiman L (2001) Random forests. Machine learning 45:5–32

Bressler SL (w.d.) I. Time series and stochastic processes. Center for complex systems and brain science. https://ccs.fau.edu/~bressler/EDU/STSA/Modules/I.pdf

Burke A, Berinhout K, Bonnie P (November 2019) Analyzing the effect of income inequality on poverty. GT Library. http://hdl.handle.net/1853/62048

Buteikis A (2020) Time series with trend and seasonality components. Vilnius University. http://web.vu.lt/mif/a.buteikis/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Lecture_02.pdf

Bzdok D, Altman Kr N, Krzywinski M (2018) Statistics versus machine learning. Nat Methods 15:233–234

Calinski T, Harabasz J (1974) A dendrite method for cluster analysis. Commun Stat-Theory Methods 3:1–27

Cankaya S, Kutlub O, Cebecic E (2015) The educational policy of European Union. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 174:886–893

Castro R, Fajnzylber E (2017) Income inequality and adolescent fertility in low-income countries. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 33:1–8

CC BY 4.0 Deed Attribution 4.0 International. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

CEPAL/IEF (2014, December) Los efectos de la política fiscal sobre la redistribución en América Latina y la Unión Europea. CEPAL/IEF. https://sia.eurosocial-ii.eu/files/docs/1412088027-Estudio_8_def_final.pdf

Charrad M, Ghazzali N, Boiteau V, Niknafs A (2022) Package ‘NbClust’. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/NbClust/NbClust.pdf

Cingano F (2014) Trends in income inequality and its impact on economic growth. (Working Papers, No. 163). https://doi.org/10.1787/5jxrjncwxv6j-en

Craig RW, Xueda S (2011) The impact of education on unemployment incidence and re-employment success: evidence from the US labour market. Labour Econ 18:453–463

Dabla-Norris E, Kochhar K, Rick, F, Suphaphiphat N, Tsounta E (2015), IMF staff discussion note. Causes and consequences of income inequality: a global perspective. International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2015/sdn1513.pdf

Davies DL, Bouldin DW (1979) A cluster separation measure. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intel 1:224–227

Doan AAQ (w.d.) Intro to random forest. https://www.coursehero.com/file/43915924/random-forestpdf/

De Sousa Filho JF, Dos Santos GF, Andrade RFS (2022) Inequality and income segregation in Brazilian cities: a nationwide analysis. SN Soc Sci 2:1–22

Do Socorro CCM, Dos Santos FFW (2017) Relationship between income inequality, socioeconomic development, vulnerability index, and maternal mortality in Brazil. BMC Public Health 21:1–8

Dunn J (1974) Well separated clusters and optimal Fuzzy partitions. J Cyber 4:95–104

Economy League (2023) Leading indicators. How similar are Philadelphia and New Orleans? Econo League. https://www.economyleague.org/resources/how-similar-are-philadelphia-and-new-orleans

Eppler A, Anders L, Tuntschew T (2016) IHS political science series. Europe’s political, social, and economic (dis-)integration: Revisiting the elephant in times of crises. (Working Papers, No. 143). https://aei.pitt.edu/86060/1/wp_143.pdf

European Comission(2022) Exploring regional similarities with EU Twinnings. European Comission. Data Europe. https://data.europa.eu/en/publications/datastories/exploring-regional-similarities-eu-twinnings

Filho A, Kawachi I (2015) Income inequality is associated with adolescent fertility in Brazil: a longitudinal multilevel analysis of 5565 municipalities. BMC Public Health, 15 (103). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1369-2

Furuoka F, Idris A, Lim B, Rostika PB (2019) Labour Market in Asia and Europe: a comparative perspective on unemployment hysteresis. AEI INSIGHTS 5:7–19

García-Herrero A, Ortiz Á, Martínez D (2015) Eagles economic watch. Flourishing middle classes in the emerging world to keep driving reductions in global inequality. BBVA Research. https://www.bbvaresearch.com/en/publicaciones/flourishing-middle-classes-in-the-emerging-world-to-keep-driving-reductions-in-global-inequality/

Gasparini L, Cicowiez M, Sosa W (2014) Pobreza y desigualdad en América Latina: conceptos, herramientas y aplicaciones. CEDLAS. Facultad de Ciencias Económicas. Universidad Nacional de la Plata. https://www.cedlas.econo.unlp.edu.ar/wp/wp-content/uploads/Pobreza_desigualdad_-America_Latina.pdf

Gault FD, Hamilton KE, Hoffman RB, McInnis BC (1987) The design approach to socio-economic modelling. Futures 19:3–25

Goldstone JA, Bates RH, Epstein DL, Gurr TR, Lustik MB, Marshall MG (2010) A global model for forecasting political instability. Am J Political Sci 54:190–208

Grajales J, Aceves-Chong C, Rincón-Rabanales M, Cruz L (2016) Jatropha curcas flowers from southern Mexico: chemical profile and morphometrics. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 87:1321–1327

Guisan MC, Exposito P (2001) Economic development of African and Asia-Pacific Areas in 1951-99. Appl Econ Int Dev 1-2:101–125

Gutiérrez-Garrido F, Acuña-Duarte A (2019) Gasto municipal en educación y su efecto en la distribución de ingresos a nivel local en Chile. Ecos de Econ 23:4–28

Haidich AB, Ioannidis J (2004) The Gini coefficient as a measure for understanding accrual inequalities in multicenter clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol 57:341–8

Halkidi M, Vazirgiannis M (2001) Clustering validity assessment: finding the optimal partitioning of a data Set. In ICDM’01 Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (pp. 187–194). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDM.2001.989492

Halkidi M, Vazirgiannis M, Batistakis Y (2000) Quality scheme assessment in the clustering process. In: Zighed DA, Komorowski J, Żytkow J (Eds) Principles of data mining and knowledge discovery. PKDD 2000. Lecture notes in computer science (pp. 266–276), 1910. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-45372-5_26

Han J, Kamber M, Pei J (2012) Data mining: concepts and techniques. A volume in The Morgan Kaufmann Series in Data Management Systems (Third Edition). Elsevier. Morgan Kaufmann

Hanel PHP, Maio GR, Manstead ASR (2019) A new way to look at the data: similarities between groups of people are large and important. J Personality Soc Psychol 116:541–562

Hertog S (2013)The association between two measures of inequality in human development: Income and life expectancy. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population Division (Technical Paper No. 2013/7). https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/technical/TP2013-7.pdf

Hjerpe A (2016) Computing random forests variable importance measures (VIM) on mixed continuous and categorical Data [Bachelor’s thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology School of Computer Science and Communication]. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:921542/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Hubert LJ, Levin JR (1976) A general statistical framework for assessing categorical clustering in free recall. Psychol Bull 83:1072–1080

Human Development Reports (w. d.). Terms of Use. https://hdr.undp.org/terms-use

Human Rights education and Monitoring Center (EMC) (2014) Women & political representation. Handbook on increasing women’s political participation in Georgia. EMC. https://rm.coe.int/1680599092

Jain-Chandra S, Kinda T, Kochhar K, Piao S, Schauer J (2016) International monetary fund. Working Paper. Sharing the growth dividend: analysis of inequality in Asia. (Working Paper No. 16 \48). https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2016/wp1648.pdf

Kaur M, Dhalaria M, Sharma P, Park J (2019) Supervised machine-learning predictive analytics for national quality of life scoring. Appl Sci 9:1–15

Keller KRI (2010) How can education policy improve income distribution? An empirical analysis of education stages and measures on income inequality. J Develop Areas 43:51–77

Koç T, Akın P (2021) Comparison of machine learning methods in prediction Gini coefficient for OECD countries. Data Sci Appl 4:16–20