Abstract

Purpose-The purpose of this study is to investigate the impact of the push motivational factors (rest & relaxation, enhancing the ego, and novelty & knowledge-seeking) and pull motivational factors (tourism facilities, environment & safety, and cultural & historical attraction) on internal tourists’ visit and revisit intentions to a domestic destination in Egypt. It also tested the mediation role of the country image in the relationship between the independent variables (push & pull motives) and the dependent variables (visit & revisit intentions). This study provides novelty for the context of travel motivation, especially in a global crisis like Corona and highlight the limited literature regarding the Arab context, especially Egypt. Data were collected using an online survey of internal tourists to test the proposed model empirically using structured questions. Structural equation model (SEM) was developed to test the research hypotheses with a sample of 349. The findings indicate that all the research hypotheses were statistically supported, except for the associations between rest-and-relaxation, tourism facilities and the internal tourists’ visit intention to a destination in Egypt.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The academics of tourism have shown considerable interest in travel motivation, and how travel motivation is considered a useful approach to comprehend tourists’ needs and motives. They even propositioned the complexity of investigating why tourists intend to travel and what they want to indulge or enjoy (Yoon and Uysal, 2005). Many disciplines have been considered to explain the travel motivation phenomena, and accordingly it has been investigated by many academics from various fields, namely anthropology, sociology, and psychology fields (Mohammad and Som, 2010; Yoon and Uysal, 2005; Gnoth, 1997; Dann, 1977). Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs have been highly utilised as the most famous and well-known theory within the travel motivation literature, displaying the basic human needs at the bottom of the pyramid to its way up to the least pressing needs (Negrusa and Yolal, 2012). Therefore, the hierarchy of Maslow can be seen as the theoretical basis and background for travel motivation studies.

Travel motivation theory has been examined and investigated till it is generally accepted, which is the push and pull motives (Dann, 1981;1977). Previously, different studies have addressed and utilised the push and pull motives in the context of tourism motivation, and hence they were seen as relevant independents or predictors to be used for comprehending why tourists intend to travel, and integrating their behaviours (Correia et al., 2013; Jarvis and Blank, 2011; Mohammad and Som, 2010). Yousefi and Marzuki (2015), Negrusa and Yolal (2012), Mohammad and Som (2010), and Yoon and Uysal (2005) identified the push factors as the forces that motivate and induce individuals to go away from their home; while the pull factors are the externalities of a specific place/destination that pull individuals to visit this destination. Furthermore, Seebaluck et al. (2015) supported that push-pull motivational factors can integrate well with the hierarchy of Maslow. Thus, such an integration between the most well-known theory (Maslow’s theory) and the generally accepted theory (push-pull motives) will help to better comprehend the travel motivation and behaviours of tourists.

The dimensions that this paper focuses on and investigates for the push motives are: rest and relaxation, enhancing the ego, and novelty and knowledge-seeking. While the pull motives are the following dimensions: tourism facilities, environment and safety, and cultural and historical attractions. These dimensions were mentioned by and taken from Yousefi and Marzuki (2015). Moreover, this study concentrates on internal tourism, meaning that it considers the travel activities of those who are resident in the country of reference and non-residents visitors to the country of reference, as part of either their domestic or international tourism trips, respectively. In the same vein, it is also because many studies were focusing on either investigating residents visiting an outbound country only or investigating international tourists visiting a country of reference only (Baniya and Paudel, 2016; Yousefi and Marzuki, 2015; Mohammad and Som, 2010; Huang, 2010; Jang and Cai, 2002). Thus, this research paper provides novelty to the travel motivation context especially in global crisis such as Corona.

Country image plays an essential role in getting the interest and attention of travellers to visit a city of reference. It is considered the sum of impressions collected by a person about a specific destination or place (Gallarza et al. 2002). Doosti et al. (2016) highlighted the fact that country image is not only a good predictor in determining traveller’s visit intention but also their re-visit intention, because it influences travellers’ decision-making process for both, namely the visit and re-visit intentions. Therefore, this paper utilises the country image role as a mediator between the first relationship of the push-pull motivational factors and visit intention, and between the second association of the push-pull motives and re-visit intention. Hence, adding contribution to the tourism context.

Although studies regarding the travel motivation context have been covered excessively, focusing on the overseas countries like: Japan, Australia, North America, Canada, West Germany, France, the UK, and many regions across Asia (Hsu et al., 2009; Rittichainuwat, 2008; Kim and Prideaux, 2005; Oh et al., 1995; Uysal and Jurowski, 1994; Yuan and McDonald, 1990), Mohammad and Som (2010) highlighted the lack of information and limited literature regarding the Arab context that is why they studied Jordon as one of the Arabic countries. As a result, this research concentrates on Egypt in specific as a very promising country when it comes to tourism. Tourism in Egypt is considered a very crucial factor from the many essential factors that takes an extremely huge role in the growth of the economic development, and accordingly if tourism recovers, Egypt will recover in return (World Tourism Organisation UNWTO, 2016). Egypt is considered one of the top safest countries, according to Gallup’s 2018 Global Law and Order Report, coming in the 10th place for being safe for not only the local residents, but also for international tourists visiting Egypt. This survey showed that Egypt is being tied up with Denmark, Slovenia, Luxembourg, Austria, China, and Netherlands by scoring 88 out of 100, indicating its low crime rate (CNN Travel, 2018). A year later, Egypt escalated up to the 8th place, outranking multiple European countries, the USA, and the UK by scoring 92 out of 100, indicating its sense of personal safety and faith in law enforcement according to Gallup’s 2019 Global Law and Order Report (GALLUP, 2019, P.12; Egyptian Streets, 2019).

Egypt is considered one of the countries that attracts many tourists to visit annually. The number of international tourists arriving to Egypt annually from the period ranges from (2007) to (2019) has escalated as reported by The World Bank (2023). Even during the pandemic (Covid-19) that disrupted the economy so hard worldwide, Egypt was regarded as one of the few emerging countries that showed resilience towards the pandemic, experiencing growth in 2020, and maintaining a positive GDP growth in 2021 (International Monetary Fund, 2021). Although such a pandemic influenced the entire world in 2020, but Egypt was able to hold onto its position as a top destination for tourists, this is due to the Egyptian government’s active response and short-period lockdown. As a result, Egypt led Africa in terms of tourists’ arrivals, reporting around 3.7 million tourists visited Egypt in 2020 (Statista, 2022a). In 2021, Egypt ranked the first to have the largest number of tourists visiting the country among the rest of the African countries, reporting 3.67 million tourists (Statista, 2022b). Ultimately, Egypt ranked the highest in the 2021 Competitiveness Index of Travel and Tourism among the African Countries, scoring 4.2 (Statista, 2022c). Thus, showing such a high score of resilience will contribute to Egypt’s development (World Economic Forum, 2022).

This paper aims to investigate the impact of push motives (rest and relaxation, enhancing the ego, and novelty and knowledge-seeking) and pull motives (tourism facilities, environment and safety, and cultural and historical attractions) on internal tourists’ visit and revisit intentions to a domestic destination in Egypt. It also tests the country image and its mediation role in the relationship between the independent variables (push-pull motives) and the dependent variables (visit and revisit intentions). This study provides novelty for the context of travel motivation, especially in a global crisis like Corona. Afterwards, the study’s objective is to assess the impact of the push and pull motivational factors on internal tourists’ visit and revisit intentions to a domestic destination in Egypt. On that basis, the following section presents the literature related to this study.

Literature review

Tourism, internal tourism, and tourists

Caldito et al. (2015) identified tourism as a global and universal economic activity, which advocates and supports the socio-economic developments and processes within the countries, territories, or provinces where they are developed. The United Nations (2010, P.1) and the World Tourism Organisation UNWTO (n.d.) considered tourism in different phenomena such as social, cultural, as well as economical. Tourism entails the transfer and movement of individuals to different places or countries that are regarded to be outside the individuals’ own usual and normal environment for one purpose or more purposes (World Tourism Organisation UNWTO, n.d.), including professional purposes, leisure purposes, or even personal ones (United Nations, 2010, P.10). On that basis, internal tourism is the comprising of both, namely the domestic and in-bound tourism (World Tourism Organisation UNWTO, n.d.). The internal tourism is considered the activities of both, resident as well as non-resident visitors, as part of either domestic tourism trips or international tourism trips within the country of reference (United Nations, 2010, P.15). Accordingly, tourists are those individuals who leave voluntarily their usual environment and go-to surroundings where they used to live and work, integrating and participating in various activities despite of the destination being close or far-away, as conformed by Camilleri (2017).

Travel motivation

Travel motivation has gained the attention and interest of many researchers in various research, studies, and fields. It has also showed its importance in different contexts of comprehending well travellers’ behaviours and intentions (Baniya and Paudel, 2016). Motivation can stimulate an action, and in that sense, it is considered the person’s psychological as well as internal forces which in sequence can spur that action (Armstrong and Kotler, 2013). Due to this action that is being stimulated, then it can satisfy a specific need (Li et al., 2015). This elucidates that for these actions to be stimulated, the person must have from the beginning some psychological or what is so called biological needs and wants. The existence of these needs and wants will start directly and immediately to motivate the person, and in return some behaviours and activities will be integrated (Negrusa and Yolal, 2012). Indeed, individual’s motivation is like a collection of driving forces that in return can conciliate performing and carrying out specific actions that can be induced by the person who is being motivated (Sandybayev et al., 2018). In line with that, Chang et al. (2014) clarified that tourists will tend to participate, engage, and integrate in a specific behaviour, however that integration or participation is due to being motivated based on some reasons, forces, or even goals. Jarvis and Blank (2011) challenged that it is not necessary that all tourists will be motivated by the same motives or forces, as that way might cause many problems if tourists to be treated the same exact way. Understanding and comprehending well individual’s motives is the most important key for designing offerings and tailoring them to suit the targeted markets (Negrusa and Yolal, 2012; Park et al., 2008).

Negrusa and Yolal (2012) defined motivation as an initiator for the everyday individual’s decision-making process. It is considered what affects people’s choices through internal and psychological influences. This agrees with Banner and Himmelfarb (1985 as cited in Jarvis and Blank, 2011), supporting that tourism is solely based on the voluntary motivation (intrinsic force), leaving behind the extrinsic motivation. Getz (2008) agreed to some extent with what addressed earlier regarding the voluntary motivation, supporting that it is well-established compared to the extrinsic motivation. Hence, this clarifies the lack of support towards the extrinsic force that requires more comprehension and understanding when it comes to the tourism motivation (Jarvis and Blank, 2011). However, other researchers argued the above and addressed a different perspective, Seebaluck et al. (2015) stated that travel motivation is a combination of both, namely intrinsic and extrinsic factors, and accordingly these factors can stimulate the desire for travelling and visiting a specific destination in mind and that tourists can satisfy concurrently many distinctive needs and wants, instead of pleasing/delighting one need only. This agrees with what has been addressed by Mohammad and Som (2010), that the forces/factors of travel motivation can be seen as a multi-dimensional concept. Nevertheless, travel motivation does not only look very interesting topic for marketers to better understand tourist’s motives/forces as stated earlier, but according to Chang et al. (2014), they addressed that it can also explore and understand the reasons behind why an individual intends to travel. Due to this perplexity on how to define or even describe travel motivation, then it is being referred to as a “Fuzzy Set” according to Kay (2003 as cited in Jarvis and Blank, 2011). To put it differently, despite that travel motivation may appear as a very interesting topic for many researchers, however it is a hard and dynamic concept in the tourism field/context (Chang et al., 2014; Mohammad and Som, 2010).

Travel motivation theories

By reviewing the previous literatures regarding the travel motivation, many well-known theories and frameworks were presented. These frameworks were widely used as a guide to many research studies of tourism motivation, explaining and identifying the behaviour of tourists (Sandybayev et al., 2018; Li et al., 2015; Negrusa and Yolal, 2012). These theories are Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs (Maslow, 1943;1954, P.2), Travel Career Pattern (Pearce, 1988, P.31), and Escape-Seeking Model (Ross and Iso-Ahola, 1991). They are followed then by the Push and Pull Motives (Dann, 1981;1977), which are considered the focus of this paper.

First, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs, which is arranged in a hierarchical-composure from tackling first the most essential human-being needs to the least pressing needs. Simply put, when a person tends to fulfil and satisfy one need, then he/she will be motivated to satisfy and delight the next upcoming need (Sandybayev et al., 2018; Pearce and Packer, 2013; Negrusa and Yolal, 2012; Maslow, 1943). According to Pearce and Packer (2013) and Mohammad and Som (2010), the hierarchy of Maslow is considered the most applied framework to contribute to studying, exploring, and identifying travel motivation. Second is the Travel Career Pattern or what is merely known by Sandybayev et al. (2018) and Li et al. (2015) as the Travel Career Ladder. Travel Career Pattern showed pivotal contribution into the travel motivation literature, identifying the existence of the multiplicity of forces. In other words, it means that tourists will not be motivated by one dominant motive only, but by multiple forces, and accordingly this shows that travel motivation can be identified in patterns of multiple forces all together (Pearce and Packer, 2013; Jarvis and Blank, 2011). Additionally, a dynamic approach can be recommended to this framework. This is because of its multiplicity of forces that can be recognised in not only tourists in the tourism context, but also in people in any social ones, confirming that this framework can be effective in any motivation context (Jarvis and Blank, 2011).

Third is the Escapism-Seeking Model. It showed a great influence on the leisure behaviour of an individual, suggesting that escaping and seeking are the two leading and master motives that affects simultaneously individuals’ motives for leisure activities (Ross and Iso-Ahola, 1991). Negrusa and Yolal (2012) also explained that seeking activities are sought in trying and discovering novel and new things or places; and mainly for fulfilling the self and acquiring psychological rewards. While for the escape, it refers to the fleeing from the daily stressful environment, difficulties, and the tedious routine of life. The last theory that this study will tackle is the Push-Pull Framework. This is not the last theory when it comes to the travel motivation theories and context, it is considered the main focus of this paper.

Push and pull motives

Push and Pull motives are considered the main constructs of this study. Sandybayev et al. (2018), Li et al. (2015), and Negrusa and Yolal (2012) identified the push motives as the forces that induce individuals to go away from home. While the pull motives are the forces that pull individuals to visit a specific destination, it is the destination’s external attractions. Push and Pull motives were addressed before in various research studies, and they were seen as relevant and effective constructs to be used as a starting point for explaining why tourists intend to travel, alongside identifying their behaviours. Many researchers showed their agreement regarding these factors due to their utilisation in several tourism motivation literatures, and accordingly this concept is considered generally accepted (Dean and Suhartanto, 2019; Correia et al., 2013; Jarvis and Blank, 2011). Apart from this, Seebaluck et al. (2015) encouraged that the Push and Pull motives can integrate well with the above addressed theory, which is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs. Likewise, Jarvis and Blank (2011) supported that the Push-Pull motives can be adjusted by its integration with the Escapism-Seeking Model. Therefore, this shows the integration between the theories with each other to better understanding the travel motivation and behaviours.

Push motives

Push factors are considered the factors or forces that can prompt, motivate, and encourage tourists to go to a specific destination. It has also been referred to as the socio-psychological needs (Seebaluck et al., 2015), intangible elements or intrinsic factors (Isa and Ramli, 2014). These factors push tourists to travel as a way of escapism from the home-surrounding environment, daily tedious routine, and the hassle of everyday life. Hence, tourists consider that these forces can spur them to travel as a way of recharging their batteries once again; and to relax (Dunne et al., 2011). Ultimately, push factors are what push tourists to escape, have social interactions, and to be novelty-seekers and adventurous (Yousefi and Marzuki, 2015; Seebaluck et al., 2015; Isa and Ramli, 2014; Mohammad and Som, 2010). Several researchers also suggested other push factors that can stimulate tourists to travel and visit a specific place in mind which are: psychological health and fitness (Sandybayev et al., 2018; Isa and Ramli, 2014), knowledge (Yousefi and Marzuki, 2015), ego-enhancement (Seebaluck et al., 2015), and self-exploratory (Negrusa and Yolal, 2012; Mohammad and Som, 2010).

Jang and Cai (2002) studied the push-pull motives of British travellers and identified that knowledge-seeking was perceived as the most important push motive. Correspondingly, novelty-seeking was perceived as the core travel motivation factor that pushed Chinese visitors to travel to Hong Kong (Huang, 2010). This also agrees with the findings of Sangpikul (2009), discovering that the most perceived push dimensions to push Asians and Europeans to Thailand were novelty-seeking and escape and relaxation. This is similar to the results of Chen et al. (2023) study and Teng et al. (2023) study. Based on the above, this research will concentrate on the following push dimensions mentioned by Yousefi and Marzuki (2015), namely rest and relaxation, enhancing the ego, and novelty and knowledge seeking. Thus, the below hypotheses are formulated:

H1: The push-dimension impacts internal tourists’ visit intention to a domestic destination in Egypt.

H1-1: Rest and relaxation impact internal tourists’ visit intention to a domestic destination in Egypt.

H1-2: Enhancing the ego impacts internal tourists’ visit intention to a domestic destination in Egypt.

H1-3: Novelty and knowledge seeking impact internal tourists’ visit intention to a domestic destination in Egypt.

Pull motives

Pull factors are considered the externalities of a destination that can attract tourists to travel and contribute to their desire of visiting this place. Simply speaking, pull factors come from the destination itself, what is external to tourists (Seebaluck et al., 2015). Pull factors are related and linked to the cognitive or situational aspects of motivation, as a way of example, destination’s landscape, hospitality, image, publicity, facilities, branding, climate, features, promotions, and marketing (Seebaluck et al., 2015; Correia et al., 2013). According to Dunne et al. (2011), the allure and fascinating attraction of the triple S or what is so called the 3’S (Sea, Sun, and Sand) are the most relevant when it comes to vacation decision-making. Some intangible and tangible elements are also included in the pull motives, for instance, biodiversity (the variety of life that has existence on earth), rivers, as well as beaches (Seebaluck et al., 2015). Yousefi and Marzuki (2015) argued that other factors like: destination’s heritage and historical sites, cultural appeal and charms, destination’s security, natural reserves, and safety and cleanliness of the place are regarded as externalities of a destination that can pull and attract tourists. Similarly, Seebaluck et al. (2015) added that flexibility, resilience of travelling, and travel costs are also externalities of a destination that can contribute to the traveller’s desire of visiting the destination in mind.

Jang and Cai (2002) studied the push-pull motives of British travellers and identified that cleanliness and safety were perceived as the most important pull motives. Conversely, another study found that touristic activities, attractions, and travel costs were the most considered pull factors by Asian travellers visiting Thailand, whereas European travellers were pulled by the cultural, historical attractions, touristic activities and attractions (Sangpikul, 2009). Based on the above, this research will concentrate on the following pull dimensions mentioned by Yousefi and Marzuki (2015), namely tourism facilities, environment and safety, and cultural and historical attractions. Therefore, the below hypotheses are formulated:

H2: The pull-dimension impacts internal tourists’ visit intention to a domestic destination in Egypt.

H2-1: Tourism facilities impact internal tourists’ visit intention to a domestic destination in Egypt.

H2-2: Environment and safety impact internal tourists’ visit intention to a domestic destination in Egypt.

H2-3: Cultural and historical attraction impact internal tourists’ visit intention to a domestic destination in Egypt.

Mediation role: Country image

Seaton and Benett (1996 as cited in Doosti et al., 2016) and Fakeye and Crompton (1991) defined country image as the mental construction of city portrayal. Doosti et al. (2016) also added that country image is being constructed based on the understanding of the characteristics of the country/city. Ultimately, it is how tourists perceive the city and the overall set of impressions and beliefs of the country/city, which is mainly developed from the collection of information from multiple sources formed over the time, as a way of example, through tourists’ exposure to the TV, magazines, any non-tourism information, and touristic sources from advertisements to posters. Destination image is considered the visitors representation of the destination in their own minds, and such representation might include the climate, people of the city, or even the surrounding natural environment (Fakeye and Crompton, 1991).

Country’s image is very essential in attracting and getting the attention of tourists to visit the city (Kim and Lee, 2015). Avraham (2004) added that it also plays an essential role in improving and enhancing how people perceive this destination and its image. This agrees with Doosti et al. (2016) that improving the country’s image is affecting visitors’ visit intention positively as well as their decision-making process for a re-visit (future visitation intention). Stepchenkova and Morrison (2008) found that when US travellers had more willingness and intention to visit Russia, they had less negative image of Russia as the host country, and vice versa. This elucidates that enhancing the positive image of a destination can influence tourists’ visitation intentions. Likewise, Doosti et al. (2016) confirmed that city image is a significant predictor of visitors’ visitation intention when studying foreign visitors to Iran. Multiple studies also showed that positive country image can lead to revisit intentions too (Beerli and Martin, 2004; Gallarza et al., 2002). For instance, Kim and Lee (2015) showed that city image influenced positively the revisit intention of South Korean tourists to international cities.

H3: Country image will mediate the relationship between travel motivation factors and visit/revisit intentions.

H3-1: Country image will mediate the relationship between travel push motivation factors and visit intention.

H3-2: Country image will mediate the relationship between travel pull motivation factors and visit intention.

H3-3: Country image will mediate the relationship between travel push motivation factors and revisit intention.

H3-4: Country image will mediate the relationship between travel pull motivation factors and revisit intention.

Visit intention and revisit intentions

Intention as a concept is considered a very broad subject and an interesting topic in consumer behaviour (Chekima et al., 2015). This triggered the interest of many marketers to study people’s intentions in different contexts (Goh et al., 2017; Chekima et al., 2015; Dunne et al., 2011; Han et al., 2010). In the tourism context, tourists’ visit intention is considered their subjective likelihood to engage in a certain behaviour (Chang et al., 2014). Additionally, visit intention is one of the steps of the travel/vacation decision-making process (Doosti et al., 2016), and accordingly it showed great significance in the recent years (Dunne et al., 2011). Martin and Woodside (2012) clarified that the travel decision making process is like a fickle and dynamic process, and it is characterised by having a series of unique and solitary, yet unstructured decisions. These decisions may be based on some unplanned or even unexpected events, including some decisions that can be inter-related that can drive an individual to the destination’s choice/selection and visitation intention. Accordingly, it is really hard to be able to predict or even explain the decision of a tourist/traveller, it is a complex phenomenon that still stimulates scholar’s curiosity and interest back in the old decades till nowadays (Dunne et al., 2011).

Chang et al. (2014) emphasised that tourists tend to participate and integrate in a specific behaviour after being motivated based on multiple and different reasons or even goals that need to be satisfied. This confirms that these behaviours are still hard for tourists to be explained. In line with that, Martin and Woodside (2012) stressed on keeping a sharp eye on the unconscious mind of tourists, because it can assist in interpreting the causal and associative processes that result in the selection, conclusions, and intentions/actions of tourists. Ultimately, intention is a good predictor of individuals’ behaviour, where it stimulates a person for a real commitment (Chekima et al., 2015). Ajzen (1991) also emphasised that intention is the best predictor when it comes to the actual commitment, since it can indicate the behaviour even if it is not deliberated or considered. On that basis, it is essential to comprehend the visit intention of tourists for the selected destination (Martin and Woodside, 2012), which will leave a room in the future to create successful touristic destination’s campaigns and businesses (Dunne et al., 2011).

As previously mentioned in the mediating role of the country image part, the relationship between city image and tourists’ visit intentions is significant, and according to Stepchenkova and Morrison (2008), they showed that enhancing the favourable image of a destination can impact tourists’ visit intention. This means that city image is a significant predictor of tourists’ visit intention (Doosti et al., 2016).

H4: There is significant positive relationship between country image and visit intention.

Repeating the visit to a specific place that an individual visited before is considered an essential phenomenon that needs to be considered in the tourism context (Wang, 2004). This is because it is more effective, in terms of the cost, to attract repeat travellers than new visitors (Chang et al., 2014). That is why many destinations might rely extensively on repeat travellers as emphasised by Um et al. (2006), clarifying that the cost to retain back the former group (e.g., repeat tourists) is less expensive compared with the new visitors. Additionally, it has been illustrated that repeat travellers tend to spend more, in terms of money, than first-time visitors (Chang et al., 2014; Lehto et al., 2004). For instance, when studying U.S. travellers to Canada, Meis, Joyal, and Trites (1995) showed that repeat travellers spend more across the whole duration of their travel-life cycle. Chang et al. (2014) also revealed that repeat tourists tend to stay longer compared to first-time ones. This is confirmed by Wang (2004) when he studied repeat visitation of Chinese travellers to Hong Kong. Intention is a good predictor of individuals’ behaviour, and accordingly it can promote for a real commitment. Likewise, traveller’s revisit intention is considered a good predictor of traveller’s future travel behaviour to a specific destination (Chang et al., 2014). Accordingly, this helps marketers and scholars to understand and predict tourist’s future commitment and behaviour (Ajzen and Driver, 1992).

As addressed earlier in the country image section, many research studies showed positive and significant relationship between city image and re-visit intentions (Beerli and Martin, 2004; Gallarza et al., 2002). Kim and Lee (2015) also agreed on this, showing that city image is significant in predicting the re-visit intention of South Korean visitors to international destinations/cities.

H5: There is significant relationship between country image and revisit intentions.

H6: Push-Pull motives have a positive influence on tourists’ revisit intentions.

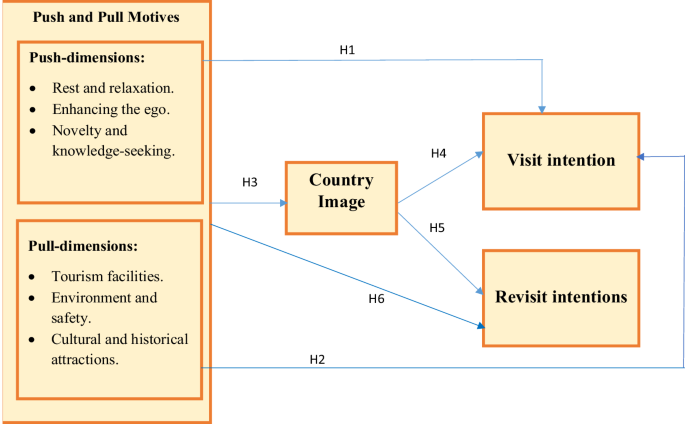

The study analytical model

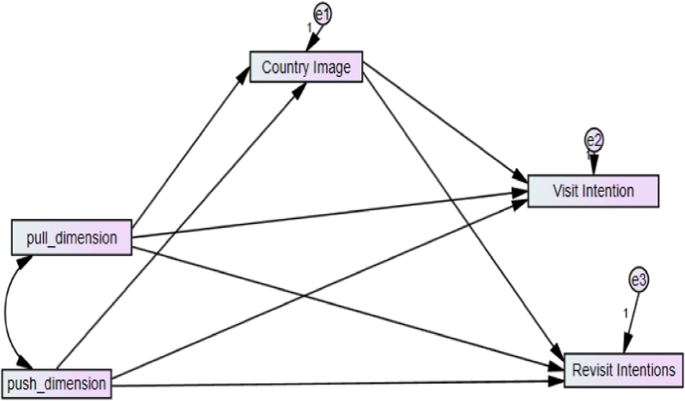

Based on the above literature reviewed, the relationships between the independent and dependent variables are presented in the below conceptual model (Fig. 1) of this research. This conceptual framework is going to discover which is the most push-dimension and the most pull-dimension, from the listed dimensions that this paper will tackle, that have a great influence on the visit intention of internal tourists to a domestic destination in Egypt (H1 and H2). It will also figure out the impact of the push-pull motives on the revisit intention of internal tourists to a domestic destination in Egypt (H6). In addition to the country image that positively mediates the relationship between push-pull dimensions and visit and re-visit intentions (H3, H4, and H5).

The figure shows the relationships between the push motivational factors (rest & relaxation, enhancing the ego, and novelty & knowledge-seeking) and pull motivational factors (tourism facilities, environment & safety, and cultural & historical attraction) on internal tourists’ visit and revisit intentions; the mediation role of the country image in the relationship between the independent variables (push & pull motives) and the dependent variables (visit & revisit intentions).

Methodology

The measurement of constructs

The items’ relevance to measuring the variable was confirmed through a pilot study involving three experts. Subsequently, the study instruments underwent pretesting consisting of 30 participants to modify and refine items clarity of words and sentences, no changes were recommended based on the results. In March 2022, a self-administered questionnaire was disseminated in Cairo -capital city of Egypt. It included multiple sections to measure the independent, dependent, and mediator variable used in this research (Push-Pull motivational factors, visit and revisit intentions, and country image). In addition to the socio-demographic data collected to provide more information on the respondents’ profile.

The survey consisted of close-ended questions, and the Egyptian internal tourists (respondents of this study) were exposed to six sections: the first section designed to obtain general information on travel characteristics. The second section identified the push and pull travel motivations, where 19 push and 18 pull motivational items were presented. Questions were developed based on a comprehensive review of travel motivation past studies, where the items got selected and adapted from Yousefi and Marzuki (2015), Hsu and Huang (2008), Sangpikul (2009), Jang and Wu (2006), and Hanqin and Lam (1999). The third section obtained data on the country image, that was measured by four items adopted from Chi and Qu (2008), following the studies of Jalilvand and Samiei (2012) and Jalilvand et al. (2013). The fourth section obtained data on the visit intentions that was measured by four items scale adopted from Usakli and Baloglu (2011). These sections were presented in a statement format and assessed on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (means strongly disagree) to 5 (means strongly agree). Respondents were also exposed to the last two sections: the fifth section obtained data on the re-visit intentions, where respondents got asked to rate their revisit intentions to different destinations in Egypt. Three items were selected from Deslandes (2003) for their reliability and adapted to fit the context of this research. The sixth and last section obtained data on the socio-demographics, where respondents required to provide some personal details regarding their profile (like gender, age, marital status, income, occupation, educational level, travel companion, accommodation, and nationality).

Sampling and data collection

This study tests the hypotheses and research framework by means of questionnaire survey with an extensive literature review. The research object of this study is Egyptian internal tourists. The questionnaire was sent to the randomly selected consumers.

Due to the fact that the tourists’ segment in Egypt exceeds 1 million according to the Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics -CAPMAS (2021); therefore, the sample size will be 384 respondents according to the Uma Sekaran table (Sekaran, 2003). In total, 385 responses were received, (70.2%) females and (29.8%) males. In total, 36 cases were deleted because of incomplete answers, which generated 349 usable responses to proceed for analysis, around (7.2%) are aged between 18 and 24 years, almost (31.2%) between 25 and 34, (36.7%) between 35 and 44, (20.9%) between 45 and 54, (3.4%) between 55 and 64, and (0.6%) above 64 years. This shows that younger generation are more involved in domestic tourism. In terms of education, around (4.9%) from Secondary/Diploma, (2.6%) earned High School degree, (33.8%) had an Undergraduate degree, and (58.7%) had a graduate degree. In terms of Job level, around (18.3%) were businessperson, (47.2%) were employees, (31%) were unemployed, and (3.5%) retired. In terms of travel companion, almost (62.5%) travel with family, around (24.9%) travel with friends, (4.6%) travel for work, around (4.9%) travel alone, and around (3.2%) travel with other companions. Regarding the marital status (7.2%) were single, (85.4%) were married, (6.6%) are widowed, and (0.9%) were divorced.

Statistical analysis and results

Table 1 indicates that the questionnaire is reliable as the Cronbach’s alpha and average inter-item correlation coefficient for all items greater than (0.7), ranging from 0.732 (ego-enhancement) to 0.811 (novelty and knowledge seeking), emphasising a good level of internal consistency (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994). AVE value for all items greater than 0.5, ranging from 0.600 (revisit intention) to 6.83 (country image). AVE values above 0.50 are considered to be adequate (Hair et al., 2006).

Descriptive statistics of variables

From Table 2, the average of all variables is between 3 and 4 which mean that respondents are tend to neutrally and agree to most of the statement that measure these variables. The variable with highest agreement is the novelty and knowledge seeking and country image while the variable with least agreement is the tourism facilities and environment and safety. As overall push dimensions have higher agreement than pull dimensions.

Correlation analysis

In this subsection the correlation analysis between the variables of the study is presented. From Table 3 below, it is clear that with confident (95%) that there is positive significant correlation between country image, visit intention, revisit intentions and each of push dimensions and pull dimensions, as the p value associated with them less than (5%). However, the correlation with push dimension is higher than the correlation with pull dimension.

ANOVA test results

The p value equals 0.000 which is significant (less than 0.05)as shown in Table 4. This means that the proposed model predicts the dependent variable better than the intercept-only model (model with no predictors).

Coefficients summary

The following table (Table 5) summarise the included and excluded variables listed with significance and coefficients. The significance of the included variables is less than (0.05) which indicates that 4 variables out of 6 have significant influence on the visit intention, this with confident (95%). The significance of the excluded variables is greater than (0.05) which indicates that 2 variables out of 6 have no influence on the visit intention, with confident (95%).

-

Novelty and knowledge have significant positive impact on visit intention, this with confident (95%). The p value is 0.000 (less than 0.05) and β coefficient equals 0.393, which accept the alternative hypothesis (H1-3). Thus, novelty and knowledge have significant positive impact on visit intention, this with confident (95%), and controlling for other variables.

-

Ego-enhancement has significant positive impact on visit intention, this with confident (95%). The p value is 0.029 (less than 0.05) and β coefficient equals 0.153, which accept the alternative hypothesis (H1-2). Thus, Ego-enhancement has significant positive impact on visit intention, this with confident (95%), and controlling for other variables.

-

Rest and relaxation have insignificant impact on visit intention, this with confident (95%). The p value is 0.107 (larger than 0.05). Thus, rest and relaxation have insignificant impact on visit intention, this with confident (95%), and controlling for other variables which reject the alternative hypothesis (H1-1).

-

Cultural and historical attraction have significant positive impact on visit intention, this with confident (95%). The p value is 0.000 (less than 0.05) and βcoefficient equals 0.248, which accept the alternative hypothesis (H2-3). Thus, Cultural and historical attraction have significant positive impact on visit intention, this with confident (95%), and controlling for other variables.

-

Environment and safety have significant positive impact on visit intention, this with confident (95%). The p value is 0.048 (less than 0.05) and β coefficient equals 0.108, which accept the alternative hypothesis (H2-2). Thus, Environment and safety have significant positive impact on visit intention, this with confident (95%), and controlling for other variables.

-

Tourism facilities has insignificant impact on visit intention, this with confident (95%). The p value is 0.139 (larger than 0.05). Thus, tourism facilities have insignificant impact on visit intention, this with confident (95%), and controlling for other variables which reject the alternative hypothesis (H2-1).

-

From the standardised coefficient, the variable with highest effect on visit intention is Novelty and knowledge seeking.

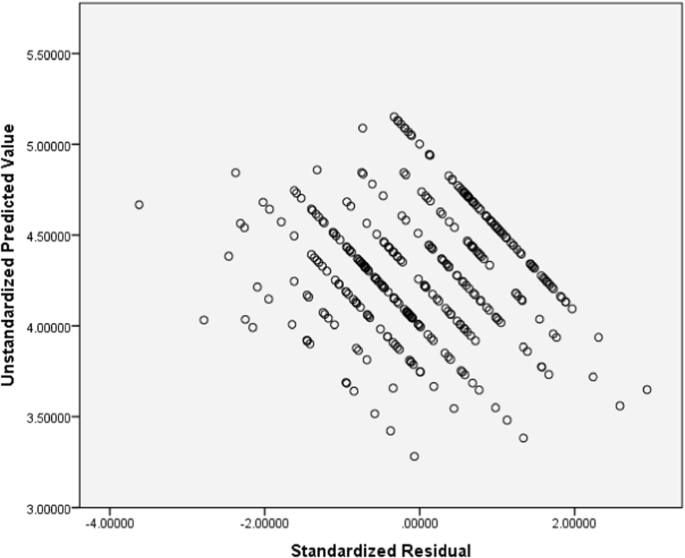

Regression model summary

-

Table 6 shows that the Adjusted R2 value of 0.989 indicates the fit of the model. The proposed model could infer 98.9% of the total variance in the visit intention.

-

From the value of Durbin Watson, there is no serial autocorrelation between residuals, as the value is near to 2. No serial auto correlation is one of the assumptions of the regression model.

Linearity assumption was checked to ensure that model results are reliable, from the graph below (Fig. 2) points are random then linearity satisfied.

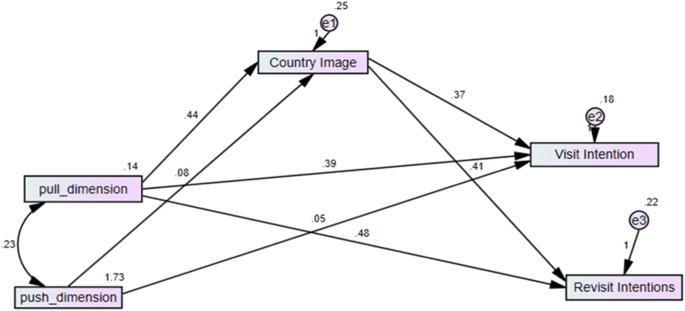

The H3, H4, H5, H6 hypotheses are answered using SEM and path analysis, then the following path model will be estimated as in Fig. 3.

-

First step

From Table 7, we can conclude that push dimension has insignificant effect on revisit intentions this with confident (95%) as p-value larger than (5%), then this path is removed, and the model will be estimated again.

-

Second and final step

The following table (Table 8) and path model (Fig. 4) present the results of the final estimated path model, and from it we can conclude that:

Pull dimension and Push dimension has direct positive impact on country image and this effect = 0.444, 0.078 respectively and this with confident (95%) as the p-value associated with them is less than (5%).

-

Country image has direct positive impact on intention to visit and this effect = 0.374, and this with confident (95%) as the p value associated with them is less than (5%).

-

Country image has direct positive impact on revisit intentions and this effect = 0.406, and this with confident (95%) as the p value associated with them is less than (5%).

-

Pull dimension has direct positive impact on intention to visit and this effect = 0.394, and it has indirect positive impact on intention to visit through country image and this indirect effect = 0.166 (0.444*0.374), then country image mediate the relationship between pull dimension and visit intention, such that it strength this relationship, and this with confident (95%) as the p value associated with them is less than (5%).

-

Pull dimension has direct positive impact on revisit intentions and this effect = 0.480, and it has indirect positive impact on intention to revisit through country image and this indirect effect = 0.180 (0.444*0.406), then country image mediate the relationship between pull dimension and revisit intentions, such that it strength this relationship, and this with confident (95%) as the p value associated with them is less than (5%).

-

Push dimension has direct positive impact on intention to visit and this effect = 0.050, and it has indirect positive impact on intention to visit through country image and this indirect effect = 0.029 (0.078*0.374), then country image mediate the relationship between push dimension and visit intention, such that it strength this relationship, and this with confident (95%) as the p value associated with them is less than (5%).

-

Push dimension has insignificant impact on revisit intentions while it has indirect positive impact on revisit intentions through country image and this indirect effect = 0.03167 (0.078*0.406), then country image mediate the relationship between push dimension and revisit intentions, such that it strength this relationship, and this with confident (95%) as the p value associated with them is less than (5%).

SEM results

Regarding model in the above table, the researcher concluded that all the goodness of fit measures of the model indicates that all indicators at acceptable limits, especially NFI (0.948), RFI (0.039), IFI (0.951), TLI (0.943), and CFI (0.949) is close to one. Also, the value of RMSEA (0.034) is less than (0.05). All these measures indicate the goodness of fit of the structural model. Although the level of significance of the Chi-square test is less than (0.05) which indicate that the model is not good fit, but this is not an accurate result as Chi-square is very sensitive for large sample size so goodness of fit of the model is determined according to the above-mentioned indicators.

Discussion

This research paper aimed to investigate the impact of the push motivational factors (rest and relaxation, enhancing the ego, and novelty and knowledge-seeking) and pull motivational factors (tourism facilities, environment and safety, and cultural and historical attraction) on internal tourists’ visit and revisit intentions to a domestic destination in Egypt. It also tested the mediation role of the country image in the relationship between the independent variables (push and pull motives) and the dependent variables (visit and revisit intentions). The hypotheses of this study were expected to be positive and significant. Indeed, positive and significant relationships were found, supporting H1-2, H1-3, H2-2, H2-3, H3-1, H3-2, H3-3, H3-4,H4, H5, and H6. However, other insignificant links were found too, especially H1-1 and H2-1.

The key findings, with the support from the past literature reviewed, showed that the relationships between enhancing the ego and visit intention (H1-2), and between novelty and knowledge-seeking and visit intention (H1-3) were positive and significant. This means that these push factors are indeed the core travel motivation factors that push and motivate internal tourists to visit a domestic destination in Egypt. The findings of this research agreed with the results of Chen et al. (2023), Dean and Suhartanto (2019), Jang and Cai (2002), Sangpikul (2009), and Huang (2010), who all supported that novelty-seeking and knowledge-seeking were perceived as the core and most important push motives for tourists. Ultimately, the findings of this study showed that the variable with the highest contribution on the visit intention is novelty and knowledge-seeking, reporting a standardised coefficient (Beta) value of (0.406). However, different results were found regarding the last push dimension, which is the rest and relaxation. The findings of this research regarding the impact of rest and relaxation on internal tourists’ visit intention to a domestic destination in Egypt (H1-1) was insignificant, and accordingly showed inconsistency with the results of Chen et al. (2023), Teng et al. (2023), and Sangpikul (2009), who argued that escape and relaxation have a positive significant impact on the visit intention as per the study of each. Therefore, H1-2 and H1-3 were met.

As predicted, significant and positive relationships were found between environment and safety and visit intention (H2-2), and between cultural and historical attraction and visit intention (H2-3), demonstrating that these pull dimensions are the core externalities of a destination that can attract internal tourists to visit a domestic destination in Egypt. The outcomes of this study agreed with the findings of Jang and Cai (2002), who confirmed that cleanliness and safety were perceived as the most important pull motives for British travellers. In addition to the consistency showed with the results of Sangpikul (2009), who supported that cultural and historical attraction were the core pull dimensions by Europeans visiting Thailand. Thus, H2-2 and H2-3 were supported.

Country image was expected to mediate positively the relationships between the visit intention and push and pull motives. The findings revealed that country image mediates positively the relationship between the push motives and visit intention (H3-1), and the association between the pull motives and visit intention (H3-2). Therefore, strengthening these associations as it mediates. Additionally, these interactions/links were also statistically significant since they were significant at (P < 0.05), as presented on the second and final step of the Regression Weights table under the analysis chapter, demonstrating these relationships with a 95% confidence level. Based on that, and as expected, a significant and positive association was found between country image and visit intention (H4). This illustrates that enhancing the country image can end up influencing positively, directly, and significantly tourist’s visit intention. Thus, the findings of this study aligned with the results of Stepchenkova and Morrison (2008), who found that the tourists with more favourable image of Russia as the host country, the more intention and willingness they get to visit Russia. Likewise, the results showed consistency with the outcomes of Doosti et al. (2016) while studying foreign visitors to Iran. Hence, H3-1, H3-2, and H4 were met.

In this research, it was revealed that a positive, direct, and significant association exists between country image and revisit intentions. Doosti et al. (2016) supported that country image does not only impact significantly tourists’ visit intention, but also it impacts their decision-making process for a re-visit intention. Such an outcome aligned with the results of Beerli and Martin (2004) and Gallarza et al. (2002), who showed the same significant relationship. Similarly, the findings of Kim and Lee (2015) confirmed that city image is significant in predicting the revisit intentions of South Korean visitors to international cities. Finally, it was found that positive but insignificant relationship occurs between pull-push motives and revisit intentions. To demonstrate, it means that the push and pull factors do not have an impact on tourists’ revisit intentions. Therefore, H5 was confirmed, but H6 was rejected.

Conclusion

In this research, it investigated the influence of the push-pull motivational factors on internal tourists’ visit and revisit intentions to a domestic destination in Egypt. This study also tested the mediation effect of country image on the relationship between the independent variables (push and pull motives) and dependent variables (visit and revisit intentions). Based on that, the findings of this research showed that novelty and knowledge-seeking, ego-enhancement, cultural and historical attraction, environment and safety were found to understand and explain the visit intention of internal tourists to a domestic destination in Egypt very well and clearly, reporting a positive, direct, and significant relationship with the visit intention. However, the findings showed that rest and relaxation and tourism facilities did not contribute to the whole model, reporting a positive but insignificant relationship with the visit intention, and therefore contradicted with the results of the previous studies in the literature reviewed.

Over and above, this research presented that the country image is significantly and positively, as hypothesised and expected, mediates the relationship between push motives and visit intentions, and between the pull motives and visit intentions. Thus, showing its significance within the context of this research. Additionally, country image showed a significant and positive influence on both intentions investigated in this study, namely visit and revisit intentions. Therefore, this demonstrates that a more favourable country image can contribute to influencing tourists’ visit and revisit intentions to a domestic destination in Egypt.

Theoretical implications

This research has extended the knowledge and understanding base with two main contributions. Starting with, the novelty it added to these literatures: push-pull motivational factors, visit intention, and revisit intentions by providing more insights regarding internal tourist’s behaviour towards a domestic destination within the Arab region (Egypt). This is because a very limited literature has been devoted to explaining the model in Egypt, considering that Egypt is one of the promising countries when it comes to tourism and rich history. Secondly, this research has also contributed to the literature-base of the country image through providing deep valuable insights on the mediation role of country image in the relationship between the independent variables (push and pull motives) and the dependents (visit and revisit intentions).

Managerial/marketing implications

The findings of this study are considered valuable for marketers, tourism city managers, tourism-planning organisations, and government, as they are for researchers and academics, providing knowledge on how motivate and entice internal tourists to visit a domestic destination in Egypt. Marketers and tourism city managers can build strategies that can utilise the most push and pull factors that this study has investigated to embed them in their marketing campaigns. This can be achieved by utilising the novelty and knowledge seeking and ego-enhancement as the main push factors that can motivate and encourage internal tourists to visit a domestic destination in Egypt. This is in addition to utilising the factors that pull tourists from the destination itself, like cultural and historical attractions and environment and safety of the destination. Marketers can also enhance the country image and advertise for a more favourable and appealing image about Egypt, since it strengthens the associations between the independents and the dependent variables as it mediates. Finally, tourism-planning organisations and government need to cooperate and work together to promote the desirable destination based on pull factors like environment and safety of the destinations and attractions whether cultural or historical.

Limitations and directions for future research

There are limitations associated with this research. First, this research examined the motivational factors of the internal tourists in specific cities in Egypt (Cairo, Luxor, Alexandria, Aswan, Sharm El-Shiekh, Hurghada, Safaga and Ain El-Sokhna) since they are the most visited locations during vacations and were chosen based on TripAdvisor, the world’s largest travel guidance platform and may not be generalised to the other cities. Thus, the generalisability of the study findings is limited to Egyptian citizens. Second, variables may not be considered as the only variables that reflect tourists’ intentions for visit or revisit, other variables can be included like trust. For future research, tourists’ evaluation in other tourism cities of Egypt may create a new insight about the relationships among motivations, city image, and visit and revisit intention. The present study was limited by the number variables used. It is recommended that future studies should include more variables. Moreover, other studies can deal with other variables related to visiting tourism cities including value, culture, and social motives.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. The data that support part of the findings of this study are available and freely accessed from Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics available at https://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/IndicatorsPage.aspx?page_id=6133&ind_id=2251 and https://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/StaticPages.aspx?page_id=5034, GALLUP available at https://www.gallup.com/analytics/267869/gallup-global-law-order-report-2019.aspx, International Monetary Fund available at https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2021/07/14/na070621-egypt-overcoming-the-covid-shock-and-maintaining-growth, Statista available at https://ezproxy.bue.edu.eg:2917/statistics/970638/egypt-tourist-arrivals/?locale=en, https://ezproxy.bue.edu.eg:2917/statistics/261740/countries-in-africa-ranked-by-international-tourist-arrivals/, https://ezproxy.bue.edu.eg:2917/statistics/1343743/ttci-scores-of-countries-in-africa/, The World Bank available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ST.INT.ARVL?end=2019&locations=EG&start=2007&view=chart, https://www.unwto.org/archive/middle-east/press-release/2016-02-24/unwto-confident-egypt-s-tourism-recovery, World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) available at https://www.unwto.org/glossary-tourism-terms, United Nations available at https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/Seriesm/SeriesM_83rev1e.pdf#page=21, and World Economic Forum available at https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Travel_Tourism_Development_2021.pdf.

References

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2):179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen I, Driver BL (1992) Application of the theory of planned behavior to leisure choice. J Leis Res 24(3):207–224

Armstrong G, Kotler P (2013) Marketing: an introduction. 11th edn. Pearson Education Limited, Harlow

Avraham E (2004) Media strategies for improving an unfavorable city image. Cities 21(6):471–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2004.08.005

Baniya R, Paudel K (2016) An analysis of push and pull travel motivations of domestic tourists in Nepal. J Manag Dev 27:16–30

Beerli A, Martin JD (2004) Factors influencing destination image. Ann Tour Res 31(3):657–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.01.010

Caldito LA, Dimanche F, Vapnyarskaya O, Khartionova T (2015) Tourism Management. In: Dimanche F, Caldito LA (eds.) Tourism in Russia: A Management Handbook. Emerald. Emerald. p 57–99. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/302139257_Tourism_Management

Camilleri MA (2017) The tourism industry: an overview. In: Travel Marketing, Tourism Economics and the Airline Product (pp. 3-27). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49849-2_1

Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics. (2021). Statistical Year Book. https://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/StaticPages.aspx?page_id=5034. Accessed 14 Jan 2021

Chang L, Backman K, Huang Y (2014) Creative tourism: a preliminary examination of creative tourists’ motivation, experience, percieved value and revisit intention. Int J Cult Tour Hosp Res 8(4):401–419

Chekima B, Wafa SA, Igua OA, Chekima S (2015) Determinant factors of consumers’ green purchase intention: the moderating role of environmental advertising. Asian Soc Sci 11(10):318–329. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v11n10p318

Chen WY, Fang YH, Chang YP, Kuo CY (2023) Exploring motivation via three-stage travel experience: how to capture the hearts of Taiwanese family-oriented cruise tourists. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(506):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01986-3

Chi C, Qu H (2008) Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: an integrated approach. Tour Manag 29(4):624–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.06.007

CNN Travel (2018) World’s safest country to visit in 2018 revealed by Gallup survey. https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/worlds-safest-country-2018-gallup/index.html. Accessed 31 Dec 2018

Correia A, Kozak M, Ferradeira J (2013) From tourist motivations to tourist satisfaction. Int J Cult Tour Hosp Res 7(4):411–424

Dann GM (1977) Anomie, ego-enhancement and tourism. Ann Tour Res 4(4):184–194

Dann GM (1981) Tourist motivation: an appraisal. Ann Tour Res 8(2):187–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(81)90082-7

Dean D, Suhartanto D (2019) The formation of visitor behavioural intention to creative tourism: the role of push-pull motivation. Asia Pac J Tour Res 24(5):393–403

Deslandes D (2003) Assessing consumer perceptions of destinations: a necessary first step in destination branding. PhD. The Florida State University College of Business, FL, USA

Doosti S, Jalilvand MR, Asadi A, Pool JK, Adl PM (2016) Analyzing the influence of electronic word of mouth on visit intention: the mediating role of tourists’ attitude and city image. Int J Tour Cities 2(2):137–148. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-12-2015-0031

Dunne G, Flanagan S, Buckley J (2011) Towards a decision making model for city break travel. Int J Cult Tour Hosp Res 5(2):158–172

Egyptian Streets (2019) Egypt is the 8th Safest Country Worldwide: Gallup 2019. https://egyptianstreets.com/2019/11/21/egypt-is-the-8th-safest-country-worldwide-gallup-2019/. Accessed 3 Mar 2023

Fakeye PC, Crompton JL (1991) Image differences between prospective, first-time, and repeat visitors to the lower Rio Grande Valley. J Travel Res 30(2):10–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759103000202

Gallarza MG, Saura IG, Garcia HC (2002) Destination image towards a conceptual framework. Ann Tour Res 29(1):56–78

GALLUP (2019) 2019 Global Law and Order Report. GALLUP. https://www.gallup.com/analytics/267869/gallup-global-law-order-report-2019.aspx. Accessed 3 Mar 2023

Getz D (2008) Event tourism: definition, evolution, and research. Tour Manag 29(3):403–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.07.017

Gnoth J (1997) Tourism motivation and expectation formation. Ann Tour Res 24(2):283–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(97)80002-3

Goh E, Ritchie B, Wang J (2017) Non-compliance in national parks: an extension of the theory of planned behaviour model with pro-environmental values. Tour Manag 59:123–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.07.004

Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatman RL, Black W (2006) Multivariate Data, Analysis with Reading. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Han H, Hsu LT, Sheu C (2010) Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour Manag 31(3):325–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.03.013

Hanqin ZQ, Lam T (1999) An analysis of Mainland Chinese visitors’ motivations to visit Hong Kong. Tour Manag 20:587–594

Hsu CH, Huang S (2008) Travel motivation: a critical review of the concept’s development. In: Woodside AG, Martin D (eds.) Tourism Management: Analysis, Behaviour and Strategy. Wallingford, UK: CAB International, p 14-27. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781845933234.0014

Hsu TK, Tsai YF, Wu HH (2009) The preference analysis for tourist choice of destination: a case study of Taiwan. Tour Manag 30(2):288–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.07.011

Huang S (2010) Measuring Tour Motiv: Do Scales Matter? TOURISMOS 5(1):153–162

International Monetary Fund (2021) Egypt: Overcoming the COVID Shock and Maintaining Growth. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2021/07/14/na070621-egypt-overcoming-the-covid-shock-and-maintaining-growth. Accessed 3 Mar 2023

Isa S, Ramli L (2014) Factors influencing tourist visitation in marine tourism: lessons learned from FRI Aquarium Penang, Malaysia. Int J Cul Tour Hosp Res 8(1):103–117

Jalilvand MR, Samiei N (2012) The effect of electronic word of mouth on brand image and purchase intention: an empirical study in the automobile industry in Iran. J Mark Intell Plan 30(4):460–476. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634501211231946

Jalilvand MR, Ebrahimi A, Samiei N (2013) Electronic word of mouth effects on tourists’ attitudes toward Islamic destinations and travel intention: an empirical study in Iran. Procedia Soc 81(1):484–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.465

Jang S, Cai LA (2002) Travel motivations and destination choice: a study of british outbound market. J Travel Tour Mark 13(3):111–133

Jang S, Wu CME (2006) Seniors’ travel motivation and the influential factors: An examination of Taiwanese seniors. Tour Manag 27(2):306–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.11.006

Jarvis N, Blank C (2011) The importance of Tourism Motivation Among Sport Event Volunteers at the 2007 World Artistic Gymnastics Championships, Stuttgart, Germany. J Sport Tour 16(2):129–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2011.568089

Kay (2003) Consumer motivation in a tourism context: continuing the work of Maslow, Rokeach, Vroom, Deci, Haley and others. Paper presented in Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference, Adelaide, South Australiapp, 600-614, 2003. http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30036658

Kim H, Lee S (2015) Impacts of city personality and image on revisit intention. Int J Tour Cities 1(1):50–69. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-08-2014-0004

Kim SS, Prideaux B (2005) Marketing implications arising from a comparative study of international pleasure tourist motivations and other travel-related characteristics of visitors to Korea. Tour Manag 26(3):347–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.022

Lehto XY, O’Leary JT, Morrison AM (2004) The effect of prior experience on vacation behavior. Ann Tour Res 31(4):801–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.02.006

Li M, Zhang H, Xiao H, Chen Y (2015) A grid-group analysis of tourism motivation. Int J Tour Res 17(1):35–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.1963

Martin D, Woodside A (2012) Structure and process modeling of seemingly unstructured leisure-travel decisions and behavior. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 24(6):855–872. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111211247209

Maslow AH (1943) A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev 50(4):370–396

Maslow AH (1954) Motivation and Personality. Harper and Row, New York

Meis S, Joyal S, Trites A (1995) The U.S. repeat and VFR visitor to canada: come again. Eh! J Tour Stud 6(1):27–37

Mohammad B, Som A (2010) An analysis of push and pull travel motivations of foriegn tourists to Jordon. Int J Bus Manag 5(12):41–50. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v5n12p41

Negrusa A, Yolal M (2012) Cultural tourism motivation - the case of romanian youth. AUOES 21(1):548–553

Nunnally J, Bernstein I (1994) Psychometric theory. McGraw Hill, New York

Oh HC, Uysal M, Weaver PA (1995) Product bundles and market segments based on travel motivations: a canonical correlation approach. Int J Hosp Manag 14(2):123–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-4319(95)00010-A

Park KS, Reisinger Y, Kang HJ (2008) Visitors’ motivation for attending the south beach wine and food festival, Miami Beach, Florida. J Travel Tour Mark 25(2):161–181

Pearce PL (1988) The Ulysses Factor: Evaluating Visitors in Tourist Settings. New York: Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-3924-6

Pearce PL, Packer J (2013) Minds on the move: New links from psychology to tourism. Ann Tour Res 40:386–411

Rittichainuwat BN (2008) Responding to disaster: Thai andScandinavian Tourists’ motivation to VisitPhuket, Thailand. J Travel Res 46(4):355–468

Ross EL, Iso-Ahola S (1991) Sightseeing Tourists’ motivation and satisfaction. Ann Tour Res 18:226–237

Sandybayev A, Houjeir R, Reczey I (2018) Exploring trends in tourism motivation. a case of tourists visiting the United Arab Emirates. Noble Int J Soc Sci Res 03(01):01–08. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.29153.20329

Sangpikul A (2009) A comparative study of travel motivations between Asian and European Tourists to Thailand. J Hosp Tour 7(1):22–43

Seebaluck N, Munhurran P, Naidoo P, Rughoonauth P (2015) An analysis of the push and pull motives for choosing Mauritius as “the” wedding destination. Procedia Soc 175:201–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.1192

Sekaran U (2003) Research methods for business: a skill-building approach, 4th edn. John Wiley & Sons, New York

Statista (2022a) Number of tourist arrivals in Egypt from 2010 to 2020 (in millions). https://ezproxy.bue.edu.eg:2917/statistics/970638/egypt-tourist-arrivals/?locale=en. Accessed 4 Mar 2023

Statista (2022b) Selected African countries with the largest number of international tourist arrivals in 2019-2021 (in millions). https://ezproxy.bue.edu.eg:2917/statistics/261740/countries-in-africa-ranked-by-international-tourist-arrivals/. Accessed 4 Mar 2023

Statista (2022c) Leading African countries in the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index (TTCI) in 2021. https://ezproxy.bue.edu.eg:2917/statistics/1343743/ttci-scores-of-countries-in-africa/. Accessed 4 Mar 2023

Stepchenkova S, Morrison AM (2008) Russia’s destination image among American pleasure travelers: revisiting Echtner and Ritchie. Tour Manag 29(3):548–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.06.003

Teng YM, Wu KS, Lee YC (2023) Do personal values and motivation affect women’s solo travel intentions in Taiwan? Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(8):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01499-5

The World Bank (2023) International Tourism, number of arrivals - Egypt. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ST.INT.ARVL?end=2019&locations=EG&start=2007&view=chart. Accessed 3 Mar 2023

Um S, Chon K, Ro Y (2006) Antecedents of Revisit Intention. Ann Tour Res 33(4):1141–1158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2006.06.003

United Nations (2010) International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics 2008. Department of Economic and Social Affairs - Statistics Division, New York. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/Seriesm/SeriesM_83rev1e.pdf#page=21. Accessed 26 Jun 2022

Usakli A, Baloglu S (2011) Brand personality of tourist destinations: an application of self-congruity theory. Tour Manag 32(1):114–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.06.006

Uysal M, Jurowski C (1994) Testing the push and pull factors. Ann Tour Res 21(4):844–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)90091-4

Wang D (2004) Tourist Behaviour and Repeat Visitation to Hong Kong. Tour Geogr 6(1):99–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680320001722355

World Economic Forum (2022) Travel & Tourism Development Index 2021: Rebuilding for a Sustainable and Resilient Future (Insight Report). https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Travel_Tourism_Development_2021.pdf. Accessed 4 Mar 2023

World Tourism Organization UNWTO (2016) UNWTO confident in Egypt’s tourism recovery. https://www.unwto.org/archive/middle-east/press-release/2016-02-24/unwto-confident-egypt-s-tourism-recovery. Accessed 18 Jan 2023

World Tourism Organization UNWTO (n.d.) Resources - Glossary: Glossary of Tourism Terms. https://www.unwto.org/glossary-tourism-terms. Accessed 26 Jun 2022

Yoon Y, Uysal M (2005) An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: a structural model. Tour Manag 26(1):45–56

Yousefi M, Marzuki A (2015) An analysis of push and pull motivational factors of international tourists to Penang, Malaysia. Int J Hosp Tour Adm 16(1):40–56

Yuan S, McDonald C (1990) Motivational determinates of international pleasure time. J Travel Res 29(1):42–44

Funding

The APC was funded through the open-access Transformative Agreement (TA) between Springer Nature, The Science, Technology, and Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) and a third party. The funders had no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, writing the manuscript, or the decision to publish. Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ayoub, D., Mohamed, D.N.H.S. The impact of push-pull motives on internal tourists’ visit and revisit intentions to Egyptian domestic destinations: the mediating role of country image. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 358 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02835-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02835-7

This article is cited by

-

The role of AI assistants in promoting sustainable Halal tourism in non-Muslim destinations

Discover Sustainability (2025)