Abstract

As technology has been developing by leaps and bounds, concerns regarding adolescent online behavioral patterns have garnered significant attention. Nevertheless, current research exhibits limitations in both perspective and depth. Consequently, this study introduces a moderated mediation model to investigate whether the mediating effect of self-efficacy and the moderating effect of emotional regulation strategies are valid in the relationship between family communication patterns and adolescent online prosocial behavior. A questionnaire survey encompassing 1183 adolescents across 12 schools in three cities of mainland China was conducted. The findings reveal that conversation orientation contributes to the augmentation of adolescents’ self-efficacy and online prosocial behavior, whereas conformity orientation follows a reversed trend. Furthermore, self-efficacy serves as a mediator in the relationship between conversation orientation and conformity orientation, influencing adolescent online prosocial behavior in both positive and negative manners. Additionally, this study underscores the significance of emotion regulation strategies; cognitive reappraisal not only reinforces the positive effects of conversation orientation, but also mitigates the adverse effects of conformity orientation, while expressive suppression demonstrates the inverse effect. This research yields a comprehensive and insightful understanding of adolescent online prosocial behavior, furnishing a valuable theoretical foundation for future research and practice in family education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The evolution of the internet has ushered in profound changes in the society people live in. As Negroponte (2015) succinctly put it, “Human learning, working, and entertainment methods, in short, human existence, have all become digitized.” The advent of the internet has introduced novel behavioral and communicative paradigms (Gosling and Mason, 2015). According to the 52nd China Internet Development Status Report, as of June 2023, 13.9% internet users in China are aged 10–19, which accounted for approximately 150 million (China Internet Network Information Center, 2023). It is evident that adolescents are highly active in online social behaviors, like online information dissemination and collective behaviors. Current research has primarily focused on negative online behaviors among adolescents, such as cyberbullying, online sexual harassment, and cyber violence (Festl and Quandt, 2016; Taylor et al., 2019; Soriano-Ayala et al., 2022). However, research on positive online behavioral of adolescents also emerged, where they engage in knowledge sharing, mutual assistance (Zulkifli et al., 2020), and emotional support (Saling et al., 2019).

In contrast to offline prosocial behaviors, online prosocial behaviors disseminate faster, utilize a more diverse array of communication channels, and cater to a broader audience. Online prosocial behaviors foster a conducive online environment: countering the adverse effects of cyberattacks and rumor dissemination, while promoting the well-being of others, thus it facilitates a positive social development (Fan et al., 2020). Some research indicates that adolescent online prosocial behavior is not expected to receive spiritual or material rewards from external sources. However, this does not rule out the intrinsic rewards such as the sense of pleasure, satisfaction, and the achievement of self-worth that individuals may experience from doing good deeds (Zheng, 2013). These behaviors not only foster positive psychological traits in adolescents (Zheng et al., 2018) but also bolster their subjective well-being and sense of purpose (Post, 2005). Thus, adolescent online prosocial behaviors benefit individuals, communities, and the society at large, contributing to social harmony and development (Lemmens et al., 2009). Consequently, this study aims to delve into the multifaceted factors influencing adolescent online prosocial behaviors and elucidate the underlying mechanisms, thereby fostering a comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon.

In the antecedent variables affecting adolescent online prosocial behavior, family environmental factors cannot be overlooked. Family functions as a significant reference group for individuals during the decision-making process (North and Kotz, 2001), and “nowhere is its influence on individual behaviors more profound than in the area of communicative behaviors” (Koerner and Fitzpatrick, 2002b). Family dynamics imbue individuals with shared worldviews, values, and belief systems (Fitzpatrick and Ritchie, 1994; Reiss, 1981), which ultimately shape their perceptions, psychological states, and behaviors (Schrodt et al., 2008). Research indicates that parent-child communication significantly influences prosocial behavior. Deficient family communication patterns correlate with heightened problem behaviors among adolescents (Wang et al., 2004). Conversely, high-quality parent-child interactions not only fortify familial bonds but also instill a sense of life purpose, foster interpersonal relationships, and enhance social adaptability, thereby elevating individual prosocial levels (Jafary et al., 2011). Hence, family communication patterns serve as a promising avenue for investigating adolescent online prosocial behaviors.

Previous studies have highlighted environmental and individual factors as the primary influences of prosocial behavior. Family, as one of the primary socialization environments during adolescent development, particularly exerts significant influence on adolescent self-efficacy through the transmission of values and social norms by parents (Ajayi and Olamijuwon, 2019). Social cognitive theory underscores the critical role of self-efficacy in individuals’ self-assessment of their capabilities (Caprara and Steca, 2005). Therefore, in exploring the relationship between family communication patterns and adolescent online behavior, introducing self-efficacy can deepen our understanding of the mechanisms through which individual factors operate in this process. However, very few research examined the impact of both family communication patterns and self-efficacy on adolescent online prosocial behavior. Thus, this study seeks to explore the relationship between various family communication patterns and self-efficacy, along with their interactive effects, to elucidate how the family environment shapes adolescents’ perceptions of their abilities and consequently influences their online prosocial behavior.

Simultaneously, emotion, regarded as a core driving force in individual development (Campos et al., 1989), plays a pivotal role in influencing the adaptation to society and psychological well-being. Effective emotion regulation is imperative for maintaining individuals’ social functioning and fostering interpersonal relationships (Gross and John, 2003). Emotion regulation strategies, an internal factor of individuals, have garnered attention in the study of family environmental factors and prosocial behavior (Song et al., 2013). Denham (1998) pointed out that the interaction between caregivers and children is a fundamental factor influencing children’s emotional regulation, which is the root cause of individual differences in emotional regulation among young children. Parenting styles, such as communication patterns, significantly impact children’s emotion regulation development (LaFreniere, 2000). Additionally, research has also found correlations between emotion regulation and prosocial behavior (Kwon and López-Pérez, 2021), as well as self-efficacy (Liu et al., 2011). Hence, this study aims to explore the role of emotion regulation strategies in the relationship between family communication patterns and adolescent online prosocial behavior.

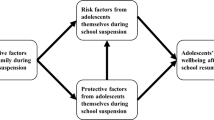

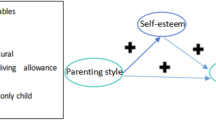

In conclusion, to comprehensively investigate the mechanisms underlying the influence of family environmental factors and individual factors on adolescent online prosocial behavior, this study endeavors to construct a moderated mediation model. It examines the influence paths of family communication patterns, self-efficacy, and emotion regulation strategies on adolescent online prosocial behavior, as well as the interactions among these factors. Compared to previous studies, the innovation of this paper mainly manifests in three aspects: First, it explicitly discusses the impact mechanism of different types of family communication patterns on self-efficacy and adolescent online prosocial behavior; Second, it investigates the influence of self-efficacy on adolescent online prosocial behavior from a holistic perspective; Third, it introduces emotion regulation strategies for examination and verifies their mechanism of action in adolescent online prosocial behavior.

Literature review and research hypothesis

Definition of online prosocial behavior

Online Prosocial Behavior (OB) is a burgeoning phenomenon associated with the evolution of the Internet, particularly the widespread adoption of mobile devices such as smartphones and computers. Despite its increasing prevalence, the concept remains intricate with multiple interpretations. Scholars often delineate online prosocial behavior by drawing upon the unique characteristics of the Internet. For instance, Zeng et al., (2022) propose that, compared to offline environments, cyberspace affords users additional time and space to care for others. Similarly, Zheng et al., (2018) contend that the anonymity provided by the Internet can alleviate users’ social pressure, fostering a greater willingness to assist others. However, these perspectives emphasize the medium carrying online prosocial behavior and relatively overlook exploring the relevant elements and behavioral characteristics of online prosocial behavior itself.

To gain a profound understanding of OB, it is imperative to scrutinize the definition of prosocial behavior and subsequently delineate how OB diverges from it. In the 1980s, Eisenberg and Miller (1987) defined prosocial behavior as a voluntary action intended to benefit others, based on the outcome of the behavior. More recently, Pfattheicher et al. (2022) approach prosocial behavior from a motivational standpoint, characterizing it as actions intended to benefit others rather than oneself. In summary, this study defines OB as voluntary conduct in the online realm aimed at benefiting others, encompassing activities like offering comfort, sharing willingly, providing guidance, and so forth. In contrast to traditional prosocial behavior, OB not only retains the fundamental connotations of prosocial behavior but also extends its boundaries, presenting a more convenient alternative to offline prosocial behavior. Noteworthy instances during the COVID-19 pandemic spotlighted how adolescents globally shared experiences and offered emotional support through online platforms (Pavarini et al., 2020). Such positive initiatives by peers can contribute to positive emotions like adolescents’ social tolerance and self-confidence (Repper and Carter, 2011), suggesting that OB holds the potential to assist adolescents in navigating challenges encountered in their personal growth. However, the current body of research on adolescent online prosocial behavior remains limited, with most studies concentrating on online prosocial behavior in adult samples (Hong et al., 2023). Consequently, this paper deems it imperative to specifically explore the driving factors and behavioral mechanisms underlying adolescent online prosocial behavior.

Self-efficacy and adolescent online prosocial behavior

Prosocial behaviors are influenced by individuals’ assessment of their own abilities, such as self-efficacy (Zhan et al., 2023). “Self-efficacy,” (SE) originating from Bandura’s social cognitive theory, is a multidisciplinary phenomenon lacking a consistent definition (Drnovšek et al., 2010). For example, Bandura (1977) defines SE as “an individual’s belief in one’s capability to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments.” Bieschke (2006) suggests that SE is the ability to assess one’s capability in implementing specific behaviors to achieve expected outcomes. Thus, all psychological processes and behavioral functions are determined by individual mastery of conscious alterations (Maddux, 2013).

Social cognitive theory posits that individual behavior is influenced by both personal cognition and environmental factors, with the family being a significant environmental factor affecting individual behavior, and self-efficacy being a crucial cognitive force (Bandura, 2004). Personal cognition may impact preferences for knowledge acquisition, information processing, and decision-making. When individuals process information, they become aware of their ability to engage in action (self-efficacy) and the likelihood of engaging in action (intentions) (Barbosa et al., 2007). According to these views, individuals can control their thoughts, feelings, and actions, with this control heavily influenced by their SE. SE provides insight into the sources of efficacy judgments that subsequently influence behavior and goal attainment (Boyd and Vozikis, 1994). This close relationship between SE and behavior has been supported by abundant empirical evidence across various fields, such as start-up readiness (Adeniyi, 2023), and environmental conservation behavior (Merling et al., 2018).

From an agentic perspective, SE serves as a motivational factor for individuals’ prosocial behaviors (Li et al., 2022). Individuals with high SE are more self-aware, comparing their existing knowledge and experiences with the current situation, and believing they have sufficient capability to address issues positively, thus being more inclined towards engaging in prosocial behaviors (Gong et al., 2021). Deng et al. (2018) conducted a survey among 768 first to third-grade middle school students in Shandong and Chongqing provinces, indicating that SE was the most predictive factor influencing prosocial behavior. Patrick et al. (2018) found that SE could predict certain types of prosocial behaviors, such as public behaviors, which may provide confidence for adolescents to engage in prosocial behaviors. In the realm of digital media technologies, researchers have discovered that bolstering self-efficacy facilitates individuals’ engagement in online prosocial behavior (Leng et al., 2020).

Building upon these insights, this paper posits that SE significantly forecasts adolescent OB; specifically, adolescents exhibiting elevated levels of SE are more inclined to actively participate in OB. Consequently, this paper advances the following research hypothesis:

H1 The higher the level of self-efficacy is, the higher level of online prosocial behavior adolescents will exhibit.

Family communication patterns, self-efficacy, and adolescent online prosocial behavior

Since its inception in the 1970s by American scholars McLeod and Chaffe (1972, as cited in Ritchie and Fitzpatrick, 1990), the Family Communication Patterns Theory (FCP) has been extensively utilized by researchers to delve into the dynamics of family communication, with ongoing refinements and evolution to its foundational theory. In the 1990s, Fitzpatrick and Ritchie (1994) classified FCP into two dimensions: Conversation Orientation (CV) and Conformity Orientation (CF). Within families emphasizing CV, there exists a heightened level of interaction and discussion on diverse subjects, fostering an environment where children can openly articulate their thoughts. Members engage in communication without constraints, and parents exercise minimal influence over their children’s conduct and perspectives. Conversely, in families leaning towards CF, internal communication is limited, and children are expected to adhere strictly to parental expectations to avert discord within the family. Emphasis is placed on uniformity among family members, particularly regarding values and beliefs (Fitzpatrick and Ritchie, 1994). FCP posits that the predisposition of family communication patterns has the potential to shape the cognition and behavior of adolescents.

Current research findings suggest a negative correlation between CF and adolescent SE (Fu et al., 2022). Scholars elucidate the adverse impact of CF on SE, attributing it to its influence on adolescent psychological well-being. Studies reveal that adolescents in families with high CF are more prone to depression, hindering the development of positive beliefs and manifesting symptoms like heightened loneliness, self-deprecation, and diminished self-esteem (Zhou et al., 2022). Notably, not all family communication patterns impede adolescent SE. CV, for instance, is positively associated with adolescent SE (Matteson, 2020). Dorrance Hall et al. (2016) examination of FCP and their impact on students’ SE, stress, and loneliness in the United States and Belgium reveals that CV positively influences SE among American students. In Belgium, significant correlations between CV and student SE were identified through the quality of social suggestions. Further research underscores that, in contrast to CF, CV provides higher social support, quality advice, and self-efficacy for family members (Bevan et al., 2019). These enhancements contribute to improved academic and social performance among adolescents. For example, CV positively affects the athletic performance of student-athletes by boosting SE (Erdner and Wright, 2017). Adolescents raised in CV families demonstrate greater financial knowledge and enhanced financial self-efficacy (Hanson and Olson, 2018).

Building upon these theoretical foundations and empirical findings, this paper posits that family communication patterns influence adolescent self-efficacy. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a The more emphasis are placed on conversational orientation in families, the higher levels of self-efficacy adolescents will exhibit.

H2b The more emphasis are placed on conformity orientation in families, the lower levels of self-efficacy adolescents will exhibit.

In the process of adolescent growth, the family shoulders significant responsibilities in nurturing and guiding individuals. Previous research indicates that families favoring CV contribute to adolescents developing positive personality traits and projecting a more amicable demeanor in social interactions. For instance, a study conducted in the United States revealed that children raised in CV families displayed more prosocial behaviors compared to those from CF families (Wilson et al., 2014). Some scholars believe that FCP can affect adolescents’ prosocial behaviors because when a family tends toward high-quality communication, it can effectively enhance the affinity and resilience levels of family members (Afifi et al., 2020). Further analysis by researchers suggests that CV not only impacts face-to-face interactions among parents and children but also significantly enhances children’s interpersonal skills and the socialization process in technology-mediated online communication (Wang et al., 2018). Conversely, an increase in CF diminishes the quality of communication within the family, fostering disagreement and intensifying the marginalization of adolescents (EHall et al., 2022). This is detrimental to the development of adolescents’ personal competencies, particularly in problem-solving, social cognition, and prosocial behavior. Building on prior research, this paper posits that adolescents raised in families favoring CV are more likely to exhibit pronounced personal characteristics, such as friendliness and solidarity, potentially leading to higher levels of online prosocial behavior. Conversely, adolescents from families emphasizing CF may demonstrate lower levels of online prosocial behavior. Consequently, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3a The more emphasis are placed on conversational orientation in families, the higher levels of online social behavior adolescents will exhibit.

H3b The more emphasis are placed on conformity orientation in families, the lower levels of online social behavior adolescents will exhibit.

In addition to direct influences, FCP can also indirectly affect adolescents’ OB through their SE. Social cognitive theory suggests that individual cognition, environment, and behavior are interconnected, mutually influencing one another (de la Fuente et al., 2023). On one hand, the family serves as a crucial environment for adolescent development, constituting a significant microsystem that influences their growth. As a fundamental aspect of the family system, interpersonal communication among family members serves as a primary socialization medium, imparting basic interpersonal skills and norms to adolescents by fostering a shared sense of reality (Koerner and Fitzpatrick, 2002; Ritchie and Fitzpatrick, 1990), thereby significantly influencing individual self-efficacy. On the other hand, individual behavioral choices are shaped by individual cognition, and changes in cognition lead to different behavioral decisions. Furthermore, attentional focus theory suggests that the situational context can alter individuals’ moods, consequently affecting their behavioral outcomes (Chen and Yang, 2020). Therefore, self-efficacy, resulting from individuals’ assessment and evaluation of their capabilities, is likely a proximal factor in determining individuals’ choices of online prosocial behaviors, while other environmental factors (such as FCP) may act as distal factors, influencing adolescents’ online prosocial behaviors through the mediating role of proximal factors. Specifically, adolescents nurtured in families favoring CV are likely to exhibit elevated SE levels, fostering a greater willingness to engage in OB. Conversely, adolescents from families with a preference for CF may experience lower levels of SE, potentially resulting in diminished participation in OB. Previous studies have also found that children raised in high CF families often manifest lower SE, leading to challenges in social integration. In contrast, those from CV families demonstrate heightened SE, and equip them with more flexible social coping skills, making it easier for them to live more actively and inspiring them to display increased prosocial behaviors both online and offline (Dorrance Hall et al. (2020); Segrin et al., 2022). Building on this premise, the paper proposes the following research hypotheses:

H4a Self-efficacy plays a positive mediating role between conversation orientation and adolescents’ online prosocial behavior.

H4b Self-efficacy plays a negative mediating role between conformity orientation and adolescents’ online prosocial behavior.

The moderating effect of emotion regulation strategies

Emotion regulation involves the process of individuals influencing which emotions they experience, when they experience them, and how they express these emotions (Gross, 1998). Within this process, individuals initially assess the generation, alteration, or response state of their emotions and subsequently employ diverse emotion regulation strategies to achieve specific objectives. Emotion regulation (ER) strategies primarily fall into two categories: Cognitive Reappraisal (CR) and Expressive Suppression (ES) (Gross and John, 2003). CR is a cognitive change strategy, involving individuals altering their interpretation of events or situations. This may entail viewing negative events from a more positive cognitive perspective or rationalizing the evaluation of events to regulate their emotions. For example, if a netizen doesn’t promptly respond to an urgent request for assistance, an individual might interpret this delay as the netizen being busy, thereby reducing feelings of disappointment or sadness. On the other hand, ES involves an individual suppressing or concealing emotional expression that is occurring or imminent. For instance, if someone feels anger toward another person, those employing the ES may avoid interacting with that person to conceal their true feelings.

Prior studies have demonstrated that emotions play a moderating role in the correlation between individual cognition and behavior (Cristofaro, 2020). Consequently, we posit that diverse emotion regulation strategies may yield distinct effects on the association between family communication patterns and adolescents’ online prosocial behavior. ES can reduce adolescents’ desire to share and express, leading to lower levels of social support, which negatively affects the socialization of adolescents, while CR can reduce negative emotions and enhance the psychological recognition and behavioral presentation of positive emotions, thereby having a positive effect on individuals’ interpersonal communication (Hein et al., 2016; Laghi et al., 2018). These research findings suggest, to some extent, that CR is more likely than ES to contribute to the manifestation of prosocial behavior in adolescents.

This paper endeavors to investigate the moderating role of ER strategies in the correlation between FCP and adolescents’ OB. Specifically, when adolescents from CV families face emotionally challenging events, employing the CR strategy enables them to perceive the causes and outcomes of stressful events with more positive emotions (Robazza et al., 2023), thereby stimulating their online prosocial behavior. Similarly, the CR strategy may buffer the negative impact of conformity orientation on adolescents’ online prosocial behavior. In other words, CR empower adolescents to make positive cognitive evaluations of stressful events, thereby reducing the occurrence of antisocial behavior. Furthermore, adolescents raised in high CF environments, where their emotional expressions and opinions are undervalued by parents, may further diminish their OB when employing the ES. Similarly, adolescents from CV families using the ES during stressful events might compromise their ability to express themselves actively and empathize (Li et al., 2020), resulting in passive behaviors like silence or avoidance.

In summary, this paper posits that emotion regulation strategies play a moderating role in the relationship between family communication patterns and adolescents’ online prosocial behavior. Building upon this premise, the paper proposes the following research hypotheses:

H5a Cognitive reappraisal enhances the positive effect of conversation orientation on adolescents’ online prosocial behavior.

H5b Cognitive reappraisal weakens the negative effect of conformity orientation on adolescents’ online prosocial behavior.

H5c Expressive suppression weakens the positive effect of conversation orientation on adolescents’ online prosocial behavior.

H5d Expressive suppression enhances the negative effect of conformity orientation on adolescents’ online prosocial behavior.

This paper also focuses on the moderating role of ER strategies in the relationship between FCP and adolescents’ SE. Adolescents raised in families where there is stronger parental control and emotional neglect may find the use of ES detrimental to establishing open and free communication relationships. This leads to an increased tendency towards depression and aggression in them, which in turn lowers their SE (Hong et al., 2018). In other words, they do not believe in their ability to handle negative emotions well when faced with stress (Di Giunta et al., 2022). Conversely, the positive association between CR and adolescents’ SE (Zyberaj, 2022) enhances individuals’ positive emotions and augments their adaptability to diverse environments. This can strengthen the cognitive levels of adolescents from families with a preference for CV, enabling them to interact more amicably with the others and the whole society, and thus reduce the occurrence of conflict events (Curran and Allen, 2016). Building upon this premise, the paper posits the following hypothesis:

H6a Cognitive Reappraisal enhances the positive effect of Conversation Orientation on adolescents’ self-efficacy.

H6b Cognitive Reappraisal weakens the negative impact of Conformity Orientation on adolescents’ self-efficacy.

H6c Expressive Suppression weakens the positive effect of Conversation Orientation on adolescents’ self-efficacy.

H6d Expressive Suppression enhances the negative effect of Conformity Orientation on adolescents’ self-efficacy.

Research design

Data sources

The present study employed a questionnaire survey method to collect relevant data and to test the proposed research hypotheses. The sample of adolescent groups was selected through stratified cluster sampling. First, all provinces in China were classified into high, medium, and low levels based on the gross domestic product (GDP) rankings for the year 2022. From each level, one province was randomly selected from the eastern, central, and western regions, with Jiangsu Province, Henan Province, and Shaanxi Province chosen as samples. Then, the capital cities of these provinces, namely Nanjing, Zhengzhou, and Xi’an, were chosen as the study subjects. Secondly, from each city, one school was randomly selected from four categories: ordinary junior high school, key junior high school, ordinary senior high school, and key senior high school. Two classes were then randomly chosen from each school, ensuring a roughly equal number of junior high and high school students. In total, students from 24 classes across 12 schools were sampled. The questionnaires were distributed face-to-face by researchers during self-study classes, collected on the spot, with a total of 1300 questionnaires distributed, and 1183 valid questionnaires were recovered, resulting in a 91% response rate. Among the valid samples, there were 566 females, accounting for 47.8%, and 617 males, accounting for 52.2%, with a relatively balanced male-to-female ratio. Respondents ranged from 12 to 20 years old, with an average age of approximately 15 years old. 40.7% (n = 482) of the respondents’ parents did not received education beyond high school, 44.2% (n = 523) had one parent with education beyond high school, and 15% (n = 178) had both parents with education beyond high school.

Variable measurement

Independent variable: family communication patterns

In this study, we referred to the Family Communication Patterns Instrument developed by Fitzpatrick and Ritchie (1994) and selected 17 items for measurement. This instrument includes two dimensions: Conversation Orientation (comprising 9 items, such as “My parents often say that every family member should have a say in decision-making.”), (M = 2.729, SD = 0.957); and Conformity Orientation (comprising 8 items, such as “My parents sometimes get angry when I disagree with them.”), (M = 3.370, SD = 0.996). Respondents answered using a Likert five-point scale (ranging from “strongly disagree” = 1 to “strongly agree” = 5). The scores for each item within the two dimensions were summed and averaged; higher scores indicate that the corresponding family characteristic is more pronounced.

Mediating variable: self-efficacy

In this study, the measurement of self-efficacy was based on the scale from the research by Kleppang et al. (2023), which contains 5 items such as “I am confident that I can handle unexpected situations” and “When faced with difficulties, I can stay calm because I know I can rely on my own abilities to solve them.” Respondents answered using a Likert four-point scale (ranging from “strongly disagree” = 1 to “strongly agree” = 4). We calculated the average of the sum of scores for these 5 items, with higher scores indicating a higher level of self-efficacy among adolescents (M = 2.510, SD = 0.718).

Moderating variable: emotional regulation strategies

In this study, the Emotional Regulation Strategies Scale developed by Gross and John (2003) was employed. The scale consists of 10 items and includes two dimensions: Cognitive Reappraisal (which includes 6 items, such as “When facing stressful situations, I am capable of thinking about it in a calm way.”), (M = 2.459, SD = 0.800); and Expressive Suppression (which includes 4 items, such as “I control my emotions by not expressing them.”), (M = 3.430, SD = 0.957). Respondents answered using a Likert five-point scale (ranging from “strongly disagree” = 1 to “strongly agree” = 5). Scores for each item within the two dimensions were added and averaged, with higher scores indicating a greater tendency of an individual to use a certain emotional regulation strategy.

Dependent variable: adolescents’ online prosocial behavior

The scale for measuring adolescents’ online prosocial behavior in this study is based on the research by Guo et al. (2018). We selected 13 items (e.g., “I share useful information such as my successful learning experiences and study insights with others online.”). Respondents answered using a Likert five-point scale (from “never” = 1 to “always” = 5). We added and averaged the scores of the 13 items for each respondent, with higher scores indicating a stronger level of online prosocial behavior among adolescents (M = 2.381, SD = 0.864).

Data analysis techniques

This study utilized Smart PLS 4 software to execute partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and to assess all hypotheses. PLS-SEM is a non-parametric technique that leverages the explained variance of latent dimensions not directly observable. This method exhibits greater modeling flexibility, is suitable for small sample sizes, does not necessitate multivariate normal distribution for the research sample data, and can integrate two types of indicators—formative and reflective—without encountering model convergence issues. Therefore, Smart PLS-SEM is apt for predicting linear correlations and analyzing intricate structural models (Irma Becerra-Fernandez, 2001), particularly in directly obtaining R² to maximize the explanation of variance in the dependent variable, thus aligning closely with the data, enhancing analytical accuracy, and yielding results with robust explanatory and predictive capabilities (Avkiran and Ringle, 2018). In terms of software utilization, both SPSS 24.0 and Smart PLS 4 software were employed for all statistical analyses. Firstly, descriptive statistical analysis of the research sample was conducted using SPSS 24.0 software, with an examination of common method bias. Secondly, Smart PLS 4 software was utilized to assess the reliability and validity of the research sample, and to scrutinize the main effects, mediation effects, and moderation effects of this study.

Research results

Measurement model

To evaluate the measurement model, we assessed indicator reliability, internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2020) (refer to Tables 1 and 2). The values of Cronbach’s α, rho_A, and composite reliability for all variables in this study surpassed 0.70, indicating robust construct reliability (Hair et al., 2017). Regarding indicator loadings, all reported values in this study exceeded 0.7 for outer loadings. The average variance extracted (AVE) values for all constructs were above 0.50, providing support for convergent validity (Hair et al., 2022). Since the square root of the AVE for each construct in the model exceeded the correlations with other constructs (Fornell and Larcker, 1981), and all Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) values were below 0.85, this study exhibited strong discriminant validity (Kline, 2011). Furthermore, this study conducted Harman’s single-factor test, which, under unrotated exploratory factor analysis, revealed 6 factors with cumulative explained variance of 36.277%, where the first factor’s explained variance did not surpass the 50% threshold. Consequently, this study did not demonstrate significant common method bias.

Structural model

First, we investigated collinearity within the structural model. All internal VIF values were below 5, indicating the model is unaffected by multicollinearity (Hair et al., 2019). Second, we assessed the weights of the path coefficients. As illustrated in Table 3, all beta coefficients are statistically significant with high corresponding t-statistics. OB is significantly influenced by SE (β = 0.367, t = 13.172, p < 0.001), CV (β = 0.235, t = 10.004, p < 0.001), and CF (β = −0.190, t = 7.574, p < 0.001). SE is significantly influenced by CV (β = 0.403, t = 17.793, p < 0.001) and CF (β = −0.366, t = 16.982, p < 0.001). Therefore, hypotheses H1, H2a, H2b, H3a, and H3b are supported. Finally, we evaluated the effectiveness of the structural model using the coefficient of determination (R²), predictive relevance (Q²), and GoF. The R² values for OB and SE were 0.604 and 0.573, respectively, both exceeding 0.26, indicating strong explanatory power. The Q² values for OB and SE were 0.377 and 0.386, respectively, both greater than 0, suggesting good predictive relevance. Moreover, the overall goodness-of-fit index (GoF) of the PLS-SEM was calculated to be 0.561, surpassing the standard value of 0.36, indicating good model fit validity.

Mediation effects

We utilized the Bootstrapping technique to evaluate whether SE mediated the relationship between FCP and OB. When testing the mediating effects, it is crucial to initially ascertain the significance of each path coefficient and subsequently examine the variance accounted for (VAF) to determine whether the analysis indicates complete or partial mediation. The VAF index measurement is employed to determine the magnitude of the indirect effect relative to the total effect. (VAF < 0.2 indicates no mediation; 0.2 < VAF < 0.8 denotes partial mediation; VAF > 0.8 signifies complete mediation). As depicted in Table 3, CV significantly indirectly influence adolescents’ OB through SE (β = 0.148, p < 0.001, VAF = 0.386), indicating partial mediation. Similarly, CF significantly indirectly impact adolescents’ OB through SE (β = −0.134, p < 0.001, VAF = 0.350), also indicating partial mediation. Therefore, research hypotheses H4a and H4b are supported.

Moderation effects

First, CR significantly moderates the relationship between CV and SE (β = 0.172, t = 7.701, p < 0.001), as well as OB (β = 0.115, t = 5.563, p < 0.001). This suggests that the stronger adolescents’ ability in CR, the greater the positive effect of CV on their SE and OB. Second, ES significantly moderates the relationship between CV and SE (β = −0.225, t = 10.093, p < 0.001), as well as OB (β = −0.134, t = 6.577, p < 0.001). This implies that the stronger adolescents’ ability in ES, the smaller the positive effect of CV on their SE and OB. Third, CR significantly moderates the relationship between CF and SE (β = 0.102, t = 4.677, p < 0.001). This indicates that the stronger adolescents’ ability in CR, the smaller the negative effect of CF on their SE. Fourth, ES significantly moderates the relationship between CF and SE (β = −0.135, t = 6.175, p < 0.001), as well as OB (β = −0.066, t = 3.081, p < 0.001). This implies that the stronger adolescents’ ability in ES, the greater the negative effect of CF on their SE and OB. Additionally, CR does not moderate the relationship between CF and adolescents’ OB (β = 0.009, t = 10.354, p > 0.05). Therefore, hypotheses H5a, H5c, H5d, H6a, H6b, H6c, and H6d are all supported, while H5b is not supported.

Conclusion and discussion

Main conclusions of the study

Amidst the wave of digital socialization, online prosocial behavior among adolescents is gradually emerging as a pivotal element shaping their social interactions and self-development. This study explores the relationships among family communication patterns, self-efficacy, and emotional regulation strategies, while elucidating, through the analysis of 1183 valid questionnaires, how these factors interconnect to influence adolescents’ prosocial behavior in the digital social environment.

This study revealed a significant correlation between FCP and adolescents’ OB. These findings align relatively well with prior research (Carlo et al., 2017), emphasizing the pivotal role of the family environment in shaping adolescent social behavior and offering additional empirical support for family education and youth development. Specifically, FCP was subdivided into CV and CF, and the examination of prosocial behavior was extended online. The results indicate that adolescents from families emphasizing CV exhibit a higher frequency of OB compared to those from families with a CF. This implies that the proactive communication atmosphere in CV families offers adolescents more opportunities to express their opinions and feelings, thus cultivating a more open, confident social style, and a willingness to engage in prosocial behavior online. Conversely, in families leaning toward CF, where parents prioritize norms and subordination, adolescent social behavior may be constrained, resulting in lower levels of OB. Future research could delve deeper into guiding FCP to promote the healthy development of adolescents in the digital social environment.

The study has further identified that SE plays a mediating role in the connection between FCP and adolescents’ OB. In other words, whether the family emphasizes CV or CF, SE acts as a conduit, transferring the impact of the family environment to adolescents’ OB. Specifically, within CV families, where parents foster open communication and demonstrate comfort and assistance to their children, this supportive atmosphere contributes to the development of positive self-beliefs in children, thereby influencing their positive behavior. This aligns with previous research findings (Hesse et al., 2017), indicating that heightened SE translates into more proactive online prosocial behavior, such as sharing learning experiences and providing support to others. On the contrary, in CF families, where parents emphasize discipline and obedience, adolescents encounter the challenge of diminished SE. Influenced by stringent regulations, these children may question their social interaction abilities and independence (Horstman et al., 2018), thereby impacting their online social initiative. This suggests that a decrease in SE might make them more cautious or hesitant to engage in prosocial behavior. These findings offer insights for intervening in adolescents’ OB to better promote its development.

This study incorporates two ER strategies, CR and ES, expanding beyond prior research which predominantly focused on the influence of single-dimensional emotions on prosocial behavior (Davis et al., 2018). As a matter of fact, distinct emotional regulation strategies exhibit varying degrees of impact on individual attention and behavioral responses. First, the study reveals that in families that emphasize CV, CR exerts a positive moderating effect on adolescents’ SE and OB. This finding highlight that: with increased use of CR, adolescents from CV families can exhibit stronger SE. The mechanism of CR lies in empowering adolescents to reassess and reflect on their environment, thereby reinforcing their confidence in crisis management and boosting their SE levels. Guided by this ER strategy, a more flexible emotion adjustment ability of adolescents can also facilitate active integration into online social behaviors. Eventually, it will significantly increase their frequency of online prosocial practices. However, in the context of conformity orientation, the positive moderating effect of CR is relatively limited. While it alleviates the negative impact of CF on adolescent SE to some extent, its moderating effect on prosocial behavior is not significant. This may be attributed to CR. Functioning as an active self-perception framework, it emphasizes individual capabilities and autonomy (McRae et al., 2012). Moreover, it also enhances adolescents’ confidence in their abilities and mitigates the negative impact of CF on SE. Nevertheless, regarding prosocial behavior, individuals are influenced not only by CR but also by a combination of social motives (Hodge et al., 2022), like age, personality (Silvers et al., 2012), and other factors. Some studies suggest that when CR is combined with other effective interventions, its positive impact may not be significantly pronounced (Clark, 2022). This suggests that any ER strategy may not be universally beneficial or harmful, and subsequent research needs to consider the impact of cultural, environmental, and individual differences to enhance the universality of the findings.

Second, the study investigated the influence of ES on adolescent SE and OB within various family communication patterns. The results revealed that in families emphasizing CF, ES exacerbated the decline in adolescent SE and further restrained their engagement in online prosocial behavior. Specifically, ES reinforced negative emotions in adolescents from CF families, resulting in a diminished sense of self-worth (Tibubos et al., 2018), which subsequently lowers their self-efficacy levels. The utilization of this strategy also hindered adolescents’ inclination to express themselves, impeding their participation in OB. Moreover, ES diminished the positive effects of CV on adolescent SE and OB. Under the influence of ES, adolescents became inhibited and less confident, undermining their SE and instilling doubt in their abilities, particularly in terms of independence and problem-solving. This tendency increased the likelihood of avoiding problems or adopting extreme behaviors (McLafferty et al., 2020), negatively impacting their OB. In summary, these research findings underscore the distinct roles of different emotional regulation strategies within the family environment and highlight the divergent impact of CR and ES on adolescent SE and OB. This comprehensive understanding contributes practical insights, especially for the development of family education and youth support strategies.

Research contributions

Theoretical contribution

This study contributes to three theoretical implications. First, while the impact of specific SE on prosocial behavior within particular tasks or situations has been established, our findings elucidate the multifaceted role of SE in a complex environment. By scrutinizing its influence on OB, we gain a nuanced understanding of adolescents’ performance across diverse social contexts, transcending specific tasks or situations. This holistic perspective integrates social cognitive theory into adolescent education, enhancing comprehension of self-efficacy’s overarching significance in the realm of adolescent internet socialization, thereby providing a more accurate explanation of their conduct in the online social sphere. Second, from an emotion management standpoint, the study explores individual differences in emotion processing by investigating the impact of two emotional regulation strategies, CR and ES, on adolescent OB. This theoretical extension deepens our insights into the role of emotions in family and online social interactions, offering more precise and actionable guidance for adolescents’ emotional education. Third, within the context of the internet era, the study investigates the direct effects of various FCP on adolescents’ OB. This broadens the research scope of family education and provides practical insights for steering adolescents toward positive OB.

Practical contribution

The practical significance of this study includes several aspects. First, in the adventure of the digital age, parents are the helmsmen guiding adolescents. The research results remind parents of the profound impact family communication patterns have on their children’s development and call for their active participation and guidance in children’s online behaviors. Parents should provide emotional support to make their children feel loved and respected, which is crucial for establishing a healthy, harmonious family environment and fostering socially skilled adolescents. Second, designers of online platforms can refer to this study to improve their applications. By understanding the impacts of different family communication patterns, self-efficacy, and emotional regulation strategies on adolescents, they can fine-tune platform design to encourage positive prosocial behaviors while developing effective mechanisms to maintain the safety and healthy development of the online community. Third, school education can also incorporate prosocial behavior and emotional education into the curriculum based on the study’s findings, including empathy, cooperation, conflict resolution, and emotion management, allowing students to learn these skills through extracurricular activities and role-playing. Additionally, schools can work closely with parents to create a warm and loving atmosphere for students’ growth, with both parties committed to cultivating positive and healthy digital citizens.

Research limitations and prospects

This study has three main limitations. First, this study is the predominantly localized nature of the research sample, which overlooks adolescents from regions characterized by lower levels of economic development and education. Consequently, the generalizability of the findings may be compromised. Future research endeavors could broaden the scope of the sample by encompassing a wider range of geographical regions, cultural contexts, and educational backgrounds. Second, although the research used self-reported data, self-reporting may be subject to subjectivity and bias from social desirability. Future studies could integrate objective data collection methods to enhance the credibility of the results. Third, this study mainly focused on online prosocial behaviors in the short term and did not consider long-term effects. Future research could examine how online prosocial behaviors evolve over time and whether the impact of factors such as family communication patterns diminishes with time.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ongoing research and analysis, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adeniyi AO (2023) The mediating effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness. Hum Soc Sci Commun 10(1):123–135. 0.1057/s41599-023-02296-4

Afifi TD, Basinger ED, Kam JA (2020) The extended theoretical model of communal coping: understanding the properties and functionality of communal coping. J Commun 70(3):424–446. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa006

Ajayi AI, Olamijuwon EO (2019) What predicts self-efficacy? understanding the role of sociodemographic, behavioural and parental factors on condom use self-efficacy among university students in Nigeria. PLoS One 14(8):e0221804. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221804

Avkiran NK, Ringle CM (2018) Partial least squares structural equation modeling recent advances in banking and Finance. Cham: Springer. Springer International Publishing

Bandura A (1977) Social Learning Theory. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Bandura A (2004) Health Promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav 31(2):143–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104263660

Barbosa SD, Gerhardt MW, Kickul JR (2007) The role of cognitive style and risk preference on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions. J Leadersh Organ Stud 13(4):86–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/10717919070130041001

Bevan JL, Urbanovich T, Vahid M (2019) Family communication Patterns, received social support, and perceived quality of care in the family caregiving context. West J Commun 85(1):83–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570314.2019.1686534

Bieschke KJ (2006) Research self-efficacy beliefs and research outcome expectations: Implications for developing scientifically minded psychologists. J Career Assess 14(1):77–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072705281366

Boyd NG, Vozikis GS (1994) The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrep Theory Pract 18(4):63–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879401800404

Campos JJ, Campos RG, Barrett KC (1989) Emergent themes in the study of emotional development and emotion regulation. Dev Psychol 25(3):394–402. https://doi.org/10.1037//0012-1649.25.3.394

Caprara GV, Steca P (2005) Self–efficacy beliefs as determinants of prosocial behavior conducive to life satisfaction across ages. J Soc Clin Psychol 24(2):191–217. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.24.2.191.62271

Carlo G, White RM, Streit C, Knight GP, Zeiders KH (2017) Longitudinal relations among parenting styles, prosocial behaviors, and academic outcomes in U.S. Mexican adolescents. Child Dev 89(2):577–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12761

Chen Y, Yang X (2020) The impact of family socioeconomic status on mathematics achievement: a chained mediation model of parent-child communication and academic self-efficacy. Appl Psychol 26(01):66–74

China Internet Network Information Center (2023) The 52nd Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development Status. Retrieved from https://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2023/0828/c88-10829.html

Clark DA (2022) Cognitive reappraisal. Cogn Behav Pract 29(3):564–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2022.02.018

Cristofaro M (2020) I feel and think, therefore I am”: an affect-cognitive theory of management decisions. Eur Manag J 38(2):344–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2019.09.003

Curran T, Allen J (2016) Family communication patterns, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms: the mediating role of direct personalization of conflict. Commun Rep 30(2):80–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2016.1225224

Davis AN, Carlo G, Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Armenta B, Kim SY, Streit C (2018) The roles of familism and emotion reappraisal in the relations between acculturative stress and prosocial behaviors in Latino/a college students. J Lat./o Psychol 6(3):175–189. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000092

de la Fuente J, Kauffman DF, Boruchovitch E (2023) Editorial: past, present and future contributions from the social cognitive theory (Albert Bandura). Front Psychol 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1258249

Deng LY, Li BL, Wu YX, Xu R, Jin PP (2018) The effect of family environment for helping behavior in middle school students: mediation of self-efficacy and empathy. J Norm Univ 5:83–91

Denham SA (1998) Emotional development in young children. Guilford Press, New York

Di Giunta L, Lunetti C, Gliozzo G, Rothenberg WA, Lansford JE, Eisenberg N et al. (2022) Negative parenting, adolescents’ emotion regulation, self-efficacy in emotion regulation, and psychological adjustment. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(4):2251. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042251

Dorrance Hall E, McNallie J, Custers K, Timmermans E, Wilson SR, Van den Bulck J (2016) A cross-cultural examination of the mediating role of family support and parental advice quality on the relationship between family communication patterns and first-year college student adjustment in the United States and Belgium. Commun Res 44(5):638–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650216657755

Dorrance Hall E, Shebib SJ, Scharp KM (2020) The mediating role of helicopter parenting in the relationship between family communication patterns and resilience in first-semester college students. J Fam Commun 21(1):34–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2020.1859510

Drnovšek M, Wincet J, Cardon MS (2010) Entrepreneurial self‐efficacy and business start‐ up: developing a multi‐dimensional definition. Int J Entrep Behav Res 16(4):329–348. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551011054516

EHall ED, Earle K, Silverstone J, Immel M, Carlisle M, Campbell N (2022) Changes in family communication during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of family communication patterns and relational distance. Commun Res Rep 39(1):56–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2021.2025045

Eisenberg N, Miller PA (1987) The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychol Bull 101(1):91–119. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.101.1.91

Erdner SM, Wright CN (2017) The relationship between family communication patterns and the self-efficacy of student-athletes. Commun Sport 6(3):368–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479517711450

Fan N, Ye B, Ni L et al. (2020) The influence of family functioning on college students’ online altruistic behavior: a moderated mediation model. Chin J Clin Psychol 28(1):185–187

Festl R, Quandt T (2016) The role of online communication in long-term cyberbullying involvement among girls and boys. J Youth Adolesc 45(9):1931–1945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0552-9

Fitzpatrick MA, Ritchie LD (1994) Communication schemata within the family. Hum Commun Res 20(3):275–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1994.tb00324.x

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

Fu W, Pan Q, Zhang W, Zhang L (2022) Understanding the relationship between parental psychological control and prosocial behavior in children in China: The role of self-efficacy and gender. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(18):11821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811821

Gosling SD, Mason W (2015) Internet research in psychology. Annu Rev Psychol 66:877–902

Gong Y, Mao FQ, Xia YW, Zhang T, Wang G, Wang X (2021) Mediating role of psychological security between college students’ self-efficacy and prosocial tendency. Chin J Health Psychol 29:146–151

Gross JJ (1998) The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Rev Gen Psychol 2(3):271–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271

Gross JJ, John OP (2003) Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 85(2):348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Guo Q, Sun P, Li L (2018) Shyness and online prosocial behavior: a study on multiple mediation mechanisms. Comput Hum Behav 86:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.032

Hair J, Risher J, Sarstedt M, Ringle C (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hair Jr JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM et al (2022) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed. SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2017) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed. SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Hair JF, Howard MC, Nitzl C (2020) Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J Bus Res 109:101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

Hanson TA, Olson PM (2018) Financial literacy and family communication patterns. J Behav Exp Financ 19:64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2018.05.001

Hesse C, Rauscher EA, Goodman RB, Couvrette MA (2017) Reconceptualizing the role of conformity behaviors in family communication patterns theory. J Fam Commun 17(4):319–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2017.1347568

Hein S, Röder M, Fingerle M (2016) The role of emotion regulation in situational empathy‐related responding and prosocial behaviour in the presence of negative affect. Int J Psychol 53(6):477–485. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12405

Hodge RT, Guyer AE, Carlo G, Hastings PD (2022) Cognitive reappraisal and need to belong predict prosociality in mexican‐origin adolescents. Soc Dev 32(2):633–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12651

Hong F, Tarullo AR, Mercurio AE, Liu S, Cai Q, Malley-Morrison K (2018) Childhood maltreatment and perceived stress in young adults: the role of emotion regulation strategies, self-efficacy, and resilience. Child Abus Negl 86:136–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.09.014

Hong M, Liang D, Lu T (2023) Fill the world with love”: songs with Prosocial lyrics enhance online charitable donations among Chinese adults. Behav Sci 13(9):739. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13090739

Horstman HK, Schrodt P, Warner B, Koerner A, Maliski R, Hays A, Colaner CW (2018) Expanding the conceptual and empirical boundaries of family communication patterns: the development and validation of an expanded conformity orientation scale. Commun Monogr 85(2):157–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2018.1428354

Irma Becerra-Fernandez RS (2001) Organizational knowledge management: A contingency perspective. J Manag Inf Syst 18(1):23–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2001.11045676

Jafary F, Farahbakhsh K, Shafiabadi A, Delavar A (2011) Quality of life and menopause: developing a theoretical model based on meaning in life, self-efficacy beliefs, and body image. Aging Ment Health 15(5):630–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2010.548056

Kleppang AL, Steigen AM, Finbråten HS (2023) Explaining variance in self-efficacy among adolescents: the association between Mastery Experiences, social support, and self-efficacy. BMC Public Health 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16603-w

Kline RB (2011) Convergence of structural equation modeling and multilevel modeling. In: Williams M, Vogt WP (eds) The SAGE Handbook of Innovation in Social Research Methods. SAGE, Los Angeles

Koerner AF, Fitzpatrick MA (2002b) Understanding family communication patterns and family functioning: the roles of conversation orientation and conformity orientation. Commun Yearb 26:36–68

Koerner AF, Fitzpatrick MA (2002) Toward a theory of family communication. Commun Theory 12(1):70–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2002.tb00260.x

Kwon K, López-Pérez B (2021) Cheering my friends up: the unique role of interpersonal emotion regulation strategies in social competence. J Soc Pers Relat 39(4):1154–1174. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211054202

LaFreniere PJ (2000) Emotional development: A biosocial perspective. Wadsworth, Belmont, Calif

Laghi F, Lonigro A, Pallini S, Baiocco R (2018) Emotion regulation and empathy: which relation with social conduct? J Genet Psychol 179(2):62–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2018.1424705

Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM, Peter J (2009) Development and validation of a game addiction scale for adolescents. Media Psycho. 12(1):77–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260802669458

Leng J, Guo Q, Ma B, Zhang S, Sun P (2020) Bridging personality and online prosocial behavior: the roles of empathy, moral identity, and social self-efficacy. Front Psychol 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.575053

Li L, Liu H, Wang G, Chen Y, Huang L (2022) The relationship between ego depletion and prosocial behavior of college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of Social Self-efficacy and personal belief in a just world. Front Psychol 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.801006

Li P, Zhu C, Leng Y, Luo W (2020) Distraction and expressive suppression strategies in down-regulation of high- and low-intensity positive emotions. Int J Psychophysiol 158:56–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2020.09.010

Liu Q, Zhou L, Mei S (2011) The mechanism of self-efficacy on adolescent emotion regulation. Chin J Spec Educ 12:82–86

Maddux JE (ed) (2013) Self-efficacy, adaptation, and adjustment: theory, research, and application. Springer Science and Business Media

Matteson SD (2020) Family communication patterns and children’s self-efficacy (Order No. 28022339). ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/family-communication-patterns-childrens-self/docview/2441549155/se-2

McLafferty M, Bunting BP, Armour C, Lapsley C, Ennis E, Murray E, O’NeillSM (2020) The mediating role of emotion regulation strategies on psychopathology and suicidal behaviour following negative childhood experiences. Child Youth Serv Rev 116:105212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105212

McRae K, Jacobs SE, Ray RD, John OP, Gross JJ (2012) Individual differences in reappraisal ability: links to reappraisal frequency, well-being, and Cognitive Control. J Res Pers 46(1):2–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2011.10.003

Merling LF, Siev J, Lit K (2018) Measuring self-efficacy to approach contamination: Development and validation of the facing-contamination self-efficacy scale. Curr Psychol 40(3):1125–1132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0029-y

Negroponte N (2015) Being digital. Vintage Books, New York

North E, Kotz T (2001) Parents and television advertisements as consumer socialization agents for adolescents: an exploratory study. J Consum Mark 20(1):55–66

Patrick RB, Bodine AJ, Gibbs JC, Basinger KS (2018) What accounts for Prosocial Behavior? roles of moral identity, moral judgment, and self-efficacy beliefs. J Genet Psychol 179(5):231–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2018.1491472

Pavarini G, Lyreskog D, Manku K, Musesengwa R, Singh I (2020) Debate: promoting capabilities for Young People’s Agency in the Covid‐19 outbreak. Child Adolesc Ment Health 25(3):187–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12409

Pfattheicher S, Nielsen YA, Thielmann I (2022) Prosocial behavior and altruism: a review of concepts and definitions. Curr Opin Psychol 44:124–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.021

Post SG (2005) Altruism, happiness, and health: It’s good to be good. Int J Behav Med 12(2):66–77. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm1202_4

Reiss D (1981) The family’s construction of reality. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Repper J, Carter T (2011) A review of the literature on peer support in Mental Health Services. J Ment Health 20(4):392–411. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2011.583947

Ritchie LD, Fitzpatrick MA (1990) Family communication patterns: measuring intrapersonal perceptions of interpersonal relationships. Commun Res 17(4):523–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365090017004007

Robazza C, Morano M, Bortoli L, Ruiz, MC (2023) Athletes’ basic psychological needs and emotions: The role of cognitive reappraisal. Front Psychol, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1205102

Saling LL, Cohen DB, Cooper D (2019) Not close enough for comfort: Facebook users eschew high intimacy negative disclosures. Pers Individ Diff 142:103–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.01.028

Schrodt P, Witt PL, Messersmith AS (2008) A meta-analytical review of family communication patterns and their associations with information processing, behavioral, and psychosocial outcomes. Commun Monogr 75(3):248–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750802256318

Segrin C, Jiao J, Wang J (2022) Indirect effects of overparenting and family communication patterns on mental health of emerging adults in China and the United States. J Adult Dev 29(3):205–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-022-09397-5

Silvers JA, McRae K, Gabrieli JDE, Gross JJ, Remy KA, Ochsner KN (2012) Age-related differences in emotional reactivity, regulation, and rejection sensitivity in adolescence. Emotion 12(6):1235–1247. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028297

Song X, Zhang Y, Lai X (2013) Emotional regulation strategies of college students and parental rearing styles. Chin J Health Psychol 21(01):126–129

Soriano-Ayala E, Cala VC, Orpinas P (2022) Prevalence and predictors of perpetration of Cyberviolence against a dating partner: a cross-cultural study with Moroccan and Spanish youth. J Interpers Violence 38(3-4):4366–4389. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221115111

Taylor BG, Liu W, Mumford EA (2019) Profiles of youth in-person and online sexual harassment victimization. J Interpers Violence 36(13-14):6769–6796. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518820673

Tibubos AN, Grammes J, Beutel ME, Michal M, Schmutzer G, Brähler E (2018) Emotion regulation strategies moderate the relationship of fatigue with depersonalization and derealization symptoms. J Affect Disord 227:571–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.079

Wang N, Roaché DJ, Pusateri KB (2018) Associations between parents’ and young adults’ face-to-face and technologically mediated communication competence: the role of family communication patterns. Commun Res 46(8):1171–1196. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650217750972

Wang Z, Lei L, Liu H (2004) The influence of parent-child communication on the social adaptation of adolescents: a comparison between regular schools and vocational schools. Psychol Sci 05:1056–1059

Wilson SR, Chernichky SM, Wilkum K, Owlett JS (2014) Do family communication patterns buffer children from difficulties associated with a parent’s military deployment? Examining deployed and at-home parents’ perspectives. J Fam Commun 14(1):32–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2013.857325

Zeng P, Nie J, Geng J, Wang H, Chu X, Qi L, Lei L (2022) Self‐compassion and subjective well‐being: a moderated mediation model of online prosocial behavior and gratitude. Psychol Sch 60(6):2041–2057. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22849

Zhan Y, Jiang X, Liu C (2023) The influence of college students’ self-responsibility on prosocial behavior willingness in moral dilemmas: the chained mediation effects of self-efficacy and anticipated pride. Psychol Res Behav 21(06):839–845

Zheng XL (2013) Theoretical and empirical research on online altruistic behavior. China Social Sciences Press, Beijing

Zheng X, Xie F, Ding L (2018) Mediating role of self-concordance on the relationship between internet altruistic behaviour and subjective well-being. J Pac Rim Psychol 12:e1. https://doi.org/10.1017/prp.2017.14

Zhou H, Zhu W, Xiao W, Huang Y, Ju K, Zheng H, Yan C (2022) Feeling unloved is the most robust sign of adolescent depression linking to family communication patterns. J Res Adolesc 33(2):418–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12813

Zulkifli NN, Abd Halim ND, Yahaya N, Van Der Meijden H (2020) Patterns of critical thinking processing in online reciprocal peer tutoring through Facebook discussion. IEEE Access 8:24269–24283. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2020.2968960

Zyberaj J (2022) Investigating the relationship between emotion regulation strategies and self‐efficacy beliefs among adolescents: Implications for academic achievement. Psychol Sch 59(8):1556–1569. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22701

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Weizhen Zhan, and Zhenwu You: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software; Weizhen Zhan, and Zhenwu You: Data curation, Writing-Original draft preparation; Zhenwu You: Visualization; Weizhen Zhan: Investigation; Weizhen Zhan, and Zhenwu You: Software, Validation; Weizhen Zhan, and Zhenwu You: Reviewing; Weizhen Zhan, and Zhenwu You: Writing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study followed local ethical guidelines for research involving human participants and complied with the Helsinki Declaration. Ethical approval was obtained from the School of Journalism and Information Communication at Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Importantly, the research did not entail medical procedures or human experimentation. Furthermore, prior to data collection, the researchers informed respondents that all gathered information would be strictly confidential and anonymized for research purposes only, and that their participation was based on informed consent.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Respondents’ participation was completely consensual, anonymous, and voluntary.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhan, W., You, Z. Family communication patterns, self-efficacy, and adolescent online prosocial behavior: a moderated mediation model. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 658 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03202-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03202-2

This article is cited by

-

Pro-Environmental Volunteering in Chinese University Youth: Peer Selection, Influence, and the Roles of Social Media and Social Self-Efficacy

Journal of Youth and Adolescence (2026)

-

Unheard voices: Identifying aspects for an inclusive digital education through the lens of low-income contexts schools

Education and Information Technologies (2025)